CHAPTER 18: BARGAINS GALORE IN BANGALORE

YOUR PASSPORT IS YOUR TICKET TO LOWER PRICES

In the United States, prices for health care are astronomical. That’s a big reason why many Americans seek medical treatments abroad, where the same services are far cheaper. The precise number of medical tourists is not known, but Patients Beyond Borders puts the number at 1.4 million.1 AARP’s estimate is lower—1 million, with dental work “accounting for about a third of all health-related trips, followed by surgeries such as coronary-bypass and bariatric operations, at 29 percent. About 13 percent of American medical travelers seek cosmetic surgery, and 7 percent get orthopedic procedures such as hip and knee replacements.”2

The amounts medical tourists save by getting treatments abroad vary depending on the procedure and the destination. Many countries, including Costa Rica, India, Malaysia, Mexico, Thailand, and Turkey, offer Americans the chance to cut their medical bills by half or more. A hysterectomy is likely to cost $32,000 in the United States but can be had for only $4,000 in Thailand. A kidney transplant goes for $150,000 here at home but costs only $25,000 in the Philippines. An American couple can expect to spend about $20,000 for a round of in vitro fertilization here but can get the same service in Israel for only $3,500.3 The more a medical service costs at home, the more Americans can save by going abroad. For big-ticket items, the savings can be large even after deducting the cost of travel.

Of course, quality and safety matter as well. But that’s where many foreign health care providers excel. They offer services that are as good as or better than those Americans can get at home. “[M]any hospitals—particularly the larger institutions in Asia and Southeast Asia—boast lower morbidity rates than in the U.S., particularly when it comes to complex cardiac and orthopedic surgeries, for which success rates higher than 98.5 percent are the norm.”4 These aren’t fly-by-night operators. “[S]everal major medical schools in the United States have developed joint initiatives with overseas providers, such as the Harvard Medical School Dubai Center, the Johns Hopkins Singapore International Medical Center, and the Duke-National University of Singapore.”5 Accrediting organizations like the Joint Commission International (JCI) and the International Society for Quality in Health Care set standards for many foreign hospitals too. JCI, a branch of “[t]he oldest and largest standards-setting and accrediting body in health care in the United States,” even maintains a website where patients can learn whether foreign providers have earned its seal of approval.6

Competition motivates all producers to raise their game and get control of their prices. Remember how Americans once thought that domestic cars were the best? Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler nurtured this myth and made it seem unpatriotic to buy a foreign car. But foreign cars were better values, so buyers flocked to them. And, as experience with foreign cars grew, more and more people saw through Detroit’s propaganda and the stigma against buying foreign cars disappeared. Now, imports from around the world are available everywhere, and competition has made all cars better, safer, and cheaper.

The truth about American health care is remarkably similar. Quality is often poor, variable, or unknown. Prices are absurd. Many foreign providers offer services that are better or just as good and that cost much less. Wanting to preserve their local monopolies, domestic providers discourage us from going abroad by stoking our fears. But the truth will emerge eventually. And as Americans learn the truth, we’ll find the idea of traveling for health care more appealing, and we’ll be more willing to embrace it unless we get better service and lower prices at home.

FIRST-RATE CARDIAC SURGERY FOR THE MASSES

Coronary artery bypass surgery, also known as CABG (pronounced “cabbage”), is used to treat blocked coronary arteries. It is what people are referring to when they say they had a single, double, triple, or quadruple bypass. CABG surgery is a big deal, and hospitals price it accordingly. The world-famous Cleveland Clinic reportedly charges more than $100,000.7

CABG surgery is dramatically cheaper—a mere $1,600—at the Narayana Hrudayalaya (NH) hospital in the Indian city of Bengaluru, formerly known as Bangalore.8 NH is the brainchild of Dr. Devi Shetty, a heart surgeon turned businessman who wants to make health care more affordable for his countrymen.9 At $1,600, someone who would otherwise have gone to the Cleveland Clinic for CABG surgery would save enough money by going to NH to pay for a multiyear vacation—even after deducting the cost of travel.

NH’s low price may lead you to think that it delivers terrible care. In health care, Americans often use price as a signal for quality—and, when something seems too cheap, we are wary. But, NH’s “mortality rates are comparable with or better than those in Britain and the U.S.”10 According to a Harvard Business School case study, NH

was staffed by approximately 90 cardiac surgeons and cardiologists, many with extensive training and experience in top-class international institutions and several of whom had performed more than 10,000 heart surgeries individually in their careers. . . . With their vast experience, the surgeons at NH were able to achieve international standards in their procedures: NH boasted of a 1.27% mortality rate and 1% infection rate in coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) procedures, comparable with rates of 1.2% and 1%, respectively, in the United States.”11

The case study was comparing NH’s mortality and infection rates to those achieved by the best cardiac surgery centers in the United States—but many American hospitals experience far more deaths and complications than NH. “Hospitals in California that perform CABG surgery have an average mortality rate of nearly 3 percent (2.91).”12 No wonder Srinath Reddy, president of the Geneva-based World Heart Federation, observed that NH is proof positive that “[i]t’s possible to deliver very high quality cardiac care at a relatively low cost.”13

SIZE MATTERS

NH’s costs are low and its quality is high partly because of its size. At 1,000 beds, NH “is the largest heart surgery hospital in the world.” Every year, its surgeons perform more cardiac procedures than the Cleveland Clinic and the Mayo Clinic combined.14

American hospital administrators often claim they have to charge insured patients high prices because they have to cover the cost of the charity care delivered to the poor and the uninsured. But about 40 percent of the surgeries performed at NH are delivered for free or at reduced prices to patients who cannot afford the full rate.15 That’s about 20 times the volume of charity care the average American hospital delivers, and NH still keeps prices far lower than U.S. hospitals. NH, which charges paying customers the lowest prices one can imagine, has never turned away a patient for lack of funds. A 2016 news report actually described NH as “cash-rich” and explained that it and other Indian hospital groups are expanding into Africa, where they expect to undercut private hospitals there too.16 If we’re lucky, these entrepreneurial providers will one day colonize the American health care market.

In keeping with our view that retailers hold the key to reducing health care costs, Shetty calls his strategy the “Walmart-izing” of health care.17 The high volume of procedures reduces the per-unit cost of surgeries, lab tests, scans, and everything else that is necessary to deliver high-quality health care services.

While other hospitals may run two blood tests on a machine each day, we run 500 tests a day—so our unit cost for each test is lower. And this works with all our processes. Also, because of our volumes, we are able to negotiate better deals with our suppliers. Instead of buying expensive machines [like other hospitals do], we pay the supplier a monthly rent for parking their machines here—and then we pay them for reagents that we buy to run the machines . . . and they are willing to do this because our demand for the reagents is high enough to make up the profits for them.18

NH further increases its size and bargaining power by combining orders with a hospital in Kolkata (formerly known as Calcutta). It also embraces new technologies that cut costs, such as digital scans that require neither film nor developing. Finally, NH runs “comprehensive hospital management software for its operations, which help[s] maintain minimum inventory and allow[s] quicker processing of tests.”19

NH also minimizes its administrative overhead. No overpaid executives are running around NH. Labor costs overall are a much lower share of operating expenses than in U.S. hospitals. “Compared to hospitals in the West which spend up to 60% of their revenues on staff salaries [including surgeons’ fees], the comparable percentage for salaries at NH is only 22%.”20 And NH’s doctors receive fixed salaries and put in long hours. At NH, cardiac surgeons are workers, not rock stars.

CARDIAC SURGEONS IN SHORT SUPPLY? TRAIN YOUR OWN

In America, organized medicine artificially limits the supply of specialists, thereby keeping wages high and driving up prices. In India, Shetty is shattering the cartel. NH runs 19 postgraduate programs, offering diplomas in subjects like cardiac thoracic surgery, cardiology, and medical laboratory technology. These programs produce intermediate-level specialists who are ready to operate on patients in much less time. “‘India’s current situation for training in cardiac care is equivalent to saying you need a degree in automotive engineering to repair cars,’ said Shetty. ‘Obviously if that were the case, we would not have any moving vehicles since we don’t have that many engineers!’”21

Cardiac surgery is rocket science, and the doctors who perform it must be well trained. Even so, NH has proven that the time and cost of producing competent cardiac surgeons can be drastically reduced. And it’s not finished cutting costs yet. Doctors at NH hope one day to be able to perform heart surgery for a mere $800.22

IF YOU BUILD IT, THEY WILL COME

Since founding NH, Shetty has created a network of 23 hospitals that operate in 14 cities under the name of Narayana Health. He has also created a “health city” in Bengaluru that includes, in addition to NH, a 1,400-bed multi-specialty hospital that handles cases involving neurosurgery, neurology, pediatrics, nephrology, urology, gynecology, and gastroenterology. The campus also houses world-class centers for cancer treatment and bone marrow transplantation.

By comparison to new hospitals in the United States, Shetty builds his on tiny budgets. He observed, “Near Stanford [University in Palo Alto, California], they are building a 200–300 bed hospital. They are likely to spend over 600 million dollars. . . . Our target is to build and equip a hospital for six million dollars and [to] build it in six months.”23

Not surprisingly, Bengaluru is now an international destination of choice for people who want outstanding health care at an affordable price. NH has performed tens of thousands of surgeries on patients from 25 foreign countries.24 Other large health care providers compete with NH for business and lure thousands more to India for care. The Fortis Escorts Heart Institute and Research Centre in New Delhi is one of them. It charges $6,000 for open-heart surgery. Unlike U.S. hospitals, which never have sales, Fortis celebrated “Heart Month” by giving patients 10 percent off its regular prices for angioplasty and CABG.25 And, like NH, Fortis and other competing hospitals have data systems that permit real-time monitoring of service delivery, including deviations from the expected cost of care and variations in clinical practice. Squeezing out inefficient variations helps ensure that all patients receive high-quality care at low cost. As a result, these inexpensive private hospitals “provide world-class service: doctors with training comparable to that of U.S. physicians (many with medical training in the United States), the latest technology and equipment, and infection and mortality rates that compare to those of U.S. hospitals.”26

The contrast with American hospitals could hardly be sharper. Here, quality improvement is a nightmare. Many administrators have little idea how well or poorly their hospitals are doing. They don’t even collect data. U.S. hospitals also refuse to adopt new technologies that benefit patients unless paid extra for doing so. In India, quality improvement is data driven and routine. The reason? Like other consumer-oriented businesses in the United States and elsewhere, private hospitals in India make money by avoiding mistakes:

Because Indian hospitals compete on both quality and price, hospital managers have instituted quality assurance and improvement as integral to the business models. In a low-price setting, these hospitals must maintain high-quality services to minimize adverse events, which generally raise the costs of care. Acceptance of financial risk by hospitals within capitated models for care delivery in India has added another driver for quality and efficiency. This concept was aptly summarized by N. Krishna Reddy of Care Hospital, who stated that in this business model, “we can’t afford to have complications.”27

As this example reflects, in a well-functioning market, hospitals have to compete for business—and they have to eat the costs of errors instead of passing them on to insurers. In that market, quality assurance programs that protect patients from complications and medical errors are quickly and seamlessly adopted, because they are good for the provider’s bottom line.

NH and its competitors don’t try to serve just the poor of India. To attract foreign patients, private hospitals in India “offer more luxurious services for higher prices. . . . Patients can pay more to enjoy more elegant rooms, but the technologies used for procedures are the same for all patients.”28 To ensure that accommodations are up to snuff and that services are packaged the way visitors want, management teams include staff members trained in the hotel industry. Hospitals in other Asian countries are using the same business model. According to a 2015 report by Deloitte,

Medical care in countries such as India, Thailand and Singapore can cost as little as 10 percent of the cost of comparable care in the United States. The price is remarkably lower for a variety of services, and often includes airfare and a stay in a resort hotel. Thanks, in part, to these low-cost care alternatives which almost resemble a mini-vacation, interest in medical tourism is strong and positive.29

How strong is the interest in medical tourism? The global market generates an estimated $50 billion to $65 billion in revenue and is growing at an estimated annual rate of 20 percent.30 As noted above, Americans are traveling to obtain many types of treatments, including CABG, cosmetic surgery, dental work, cataract removal, joint replacements, bone marrow transplants, bariatric surgery, fertility treatments, and commercial surrogates.31 Most Americans head to nearby countries like Canada and Mexico. Hungary, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and many Latin American countries are also popular destinations.

COMPETITION WILL CAUSE QUALITY TO IMPROVE

We have said repeatedly and shown in other chapters that the quality of American health care is often poor. Depending on which estimate one believes, medical errors rank somewhere in the top 10 causes of death in the United States.

When assessing the quality of foreign doctors and hospitals, this fact must be kept in mind. They don’t have to be perfect to be as good as domestic providers. This is important because patients can experience dangers when traveling abroad. For example, they may be exposed to illnesses that are not problems in the United States. Patients who travel to India may be at greater risk of contracting hepatitis B, for example, and should perhaps receive inoculations for it as a matter of course.32

In addition, Americans who are treated abroad may also require follow-up or corrective medical procedures after returning home. Things can go wrong in foreign hospitals, just as they can at home. It is exceedingly difficult to sue foreign providers for medical malpractice.

These problems must be put in context, however. Suing American health care providers for malpractice is no piece of cake either. Although doctors, tort reform advocates, and many politicians proclaim otherwise, the civil liability system in the United States is stingy. Patients lose the vast majority of malpractice trials—75 to 80 percent, according to many studies. The system also routinely sends patients with meritorious complaints home empty handed. The biggest problem with the American medical malpractice system is that it systematically under-compensates patients, with the most severely injured patients faring the worst.33

Insurance subrogation is an enormous and growing problem too. When private insurers, Medicare, or Medicaid pay for American patients’ medical bills, the payers are entitled to recoup their costs from the patients’ tort recoveries. For example, suppose that a patient is injured during surgery and requires follow-on medical treatments that cost $100,000, all of which are paid for by the patient’s health care insurer. Then, the patient sues the hospital and collects $150,000 in compensation. The insurer can recoup the $100,000 it paid out from the $150,000 that the patient received, leaving the patient with little in the way of compensation. This is one reason why Americans who are injured by medical malpractice rarely sue. There is often little or nothing to be gained.

When it comes to quality, there are two additional important things to note. First, medical tourists tend to frequent the best institutions that foreign countries offer. Economist David Reisman explains:

A top-tier clinic in a Third World country will often have better-quality capital and manpower than a second-tier hospital in the USA or the UK. Medical travellers [sic] typically go to the high-standard hospitals. They are seen by an English-speaking specialist and not a houseman. They benefit from a high ratio of doctors and nurses to beds. They are treated with state-of-the-art equipment by local staff just returned from a refresher course. Outside it may be heat and dust. Inside it may be the best that money can buy.34

Because top-tier foreign providers have incentives to treat high-profit travelers well, it is easy to understand why surveys consistently find that most people who travel for care are satisfied with the treatments they receive.

Second, tourism encourages all providers—domestic and foreign—to do better. Throughout the world, malpractice lawsuits are hard to win, so they exert little pressure on providers to improve. The signals sent by market forces must therefore be exceptionally strong. But when patients are caught up in local monopolies, as many Americans are, market-generated signals are weak because the patients lack alternatives to their local providers. Anything that helps them go elsewhere will subject local providers to pressure to do better. The end result of medical tourism may therefore be that American patients will receive treatments at home that are better and cheaper.

The pressure exerted by access to foreign providers will be great because, as mentioned already, the ones used by American medical tourists tend to be first rate. For example, the Apollo hospital chain in India has an almost perfect success rate for cardiac surgeries. Only the best American providers, like the Cleveland Clinic, do as well. Apollo’s success rates for kidney transplants and bone marrow transplants compare with the Cleveland Clinic’s as well. When it comes to ventilator-associated pneumonias, a side effect of surgery to be avoided, Singaporean hospitals outperform their counterparts in the United States. “The medical tourist having treatment at the top” foreign institutions, Reisman says, “has good reason to expect at least the same chance of full recovery that he would have had at home.”35

WHICH COUNTRIES CAN UNDERPRICE THE UNITED STATES? ALL OF THEM

A skeptic might think that other countries can sell medical services more cheaply than American providers because they are poorer. Many things are cheaper in India than they are in the United States. Workers’ wages are lower. Land costs less, as do buildings and other inputs. But the sad truth is that prices in the United States are so out of whack that even hospitals in wealthy European countries can undercut us.

Consider the case of Michael Shopenn, who needed a new hip. The average price in the United States rose from $35,000 in 2001 to $65,000 in 2011. In 2007, Shopenn received a quote of nearly $100,000. So, instead, he went to Belgium and had his hip replaced for $13,660, including the cost of round-trip airfare.36 Had he preferred fine wine and foie gras to chocolate, he might have gotten the same deal in Paris, France, and used a small part of the savings to treat himself to a meal at one of that city’s storied restaurants.

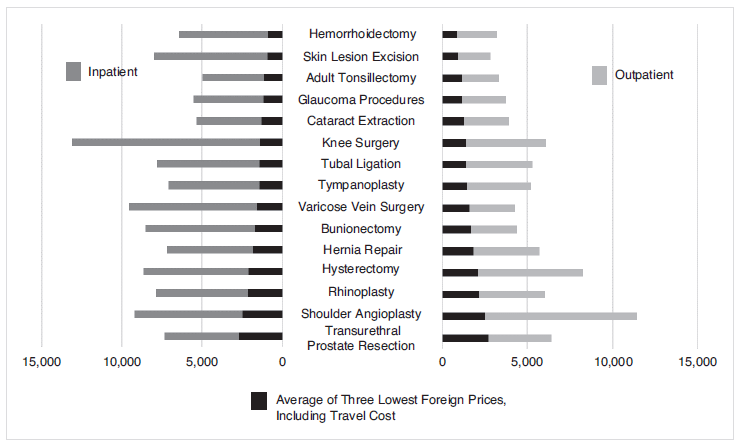

Figure 18-1 visualizes some of the data from the Deloitte report we referenced above. It shows that, using 2008 prices, Americans could save money on a wide range of procedures by going abroad, despite incurring the travel costs. Because prices for medical services in the United States’ third-party payer system are only going up, gains from traveling will likely increase in the future. As they do, more and more Americans will seek health care abroad and the services provided by health care providers will increasingly be outsourced.

In fact, outsourcing is happening already. Some American hospitals use radiologists located abroad to read X-ray films and scans. The images go out over the internet and are read by “nighthawks,” a term that describes “American-trained diagnostic radiologists located in India and Australia who provide immediate diagnostic interpretation of CT images obtained in emergency rooms after hours.”37 PlanetHospital, a medical tourism intermediary that monitors hospital certifications, has offered to set up similar arrangements with Indian physicians reading MRIs for $400 to $500.38

Figure 18-1. Average U.S. Inpatient/Outpatient Prices vs. Average Foreign Prices (2008)

Source: Deloitte Center for Health Solutions, “Medical Tourism: Consumers in Search of Value,” 2008.

GO WEST, OR JUST THREATEN TO

Americans don’t have to travel abroad for bargains. They can get them by traveling domestically too. This is so because prices for medical services can vary enormously over fairly short distances. Manhattan is so expensive that health care plans operating there could save money by chartering private jets and sending patients to Buffalo to receive treatment.

To get discounts, patients need only be able to deprive providers of market power by threatening to take their business elsewhere. The benefits of this strategy are not hypothetical. U.S. hospitals attempting to serve the Canadian market have offered large discounts to Canadian patients. Canadians can wait for free health care at home, or they can be treated immediately by paying cash for medical services in the United States. Because Canadians can go wherever they want to receive care, U.S. hospitals have to offer them bargain rates. That’s where North American Surgery (NAS) comes in. NAS negotiates discounts with surgery centers, hospitals, and clinics across the United States. A Canadian wanting a hip replacement who went through NAS would pay $16,000 to $19,000—more than a hospital in India would charge, but less than half the going U.S. rate.39

Just as Canadians can get good prices by traveling the short distance to the United States, Americans can obtain discounts by traveling to neighboring states. A cash-paying U.S. resident who is willing to travel to another city can “have procedures for up to 75% less than they would pay if they were treated closer to home.”40 Partly, the discount is for paying cash, which eliminates the cost of billing an insurer. But it also reflects hospitals’ desire for business that would not otherwise come their way.

Hospitals also offer big discounts to U.S. businesses that are willing to send their insured employees to other states for care. Consider Carter Express, a logistic, freight, and transport firm based in Anderson, Indiana.41 It saved 23 percent on an employee’s surgery for prostate cancer by participating in BridgeHealth International’s domestic medical travel program. BridgeHealth negotiated a lower price with a hospital in Denver and made the patient’s travel arrangements. “Go west, young man” wasn’t good advice just in 1871. In 2018, it can be the ticket to lower-cost health care.

BridgeHealth has a growing number of competitors. One innovative entrant is MediBid, which enables patients to shop online for lower-priced medical care, whether local or in another state.42 According to MediBid’s CEO, out-of-state hip replacements cost $14,450 to $19,000, prices comparable to European rates.

Because most Americans would rather travel domestically than internationally, domestic medical tourism has significant growth potential. The savings generally run 20 percent to 45 percent of the typical cost of a procedure, even after travel expenses and intermediaries’ fees are paid.43

Actual travel isn’t even required. Patients can get discounts just by threatening to go elsewhere. Hannaford Bros., a Northeastern supermarket chain, learned this when it offered its 27,000 workers the option of getting hip and knee replacements in Singapore. The company would waive all deductibles and copayments and cover transportation costs for the patient and a spouse or significant other.44 The offer got no takers. No employees made the trip. But that didn’t matter. Simply creating the possibility of travel was enough. In short order, “several hospitals in Boston [called] to say they would match the price of the Singapore hospitals.”45 No worker had gone anywhere; merely having access to competitors brought down the price. And the story gets better. While Hannaford was negotiating for lower prices in Boston, a hospital in Maine—Hannaford’s home state—also offered to match the Singapore rate.46

Many companies are following Hannaford’s lead.47 Walmart, the nation’s largest employer, offered insured employees no-cost heart and spine surgeries at leading hospitals across the country, including the Cleveland Clinic, the Mayo Clinic, and Geisinger Medical Center.48 Employees can go elsewhere, but those who do must be willing to incur significant out-of-pocket costs. Lowe’s, the home improvement store, entered into a similar arrangement with the Cleveland Clinic, which agreed to match the price charged by hospitals in India for cardiac surgery.49

SHARE PAINS, GAINS, AND INFORMATION

The strategy of identifying low-cost providers and requiring insureds who use more expensive ones to cover the additional cost is called “reference pricing.” A program instituted by CalPERS, the health plan that covers 1.3 million current and former California public employees, showed that reference pricing can reduce costs significantly and in unexpected ways.50 CalPERS identified 41 hospitals that charged $30,000 or less for joint replacements while meeting objective quality standards. It then told its members that they could obtain surgeries at these hospitals at no cost (other than their usual deductibles) or go to other hospitals and pay any overages themselves. The results were fantastic. Before the program started, the average cost of joint replacements for CalPERS members had risen from $28,636 to $34,742 in just two years. Then, in 2011, it suddenly dropped 26.3 percent, to $25,611. By requiring members to bear the additional charges expensive hospitals imposed, CalPERS did the impossible: it brought prices down. Not only that, hospitals outside CalPERS’ chosen 41 dropped their prices by a staggering 34.3 percent. Wanting to attract business, they did the obvious thing: compete on price.

Reference pricing saves money because, in the noncompetitive environment in which health care services are delivered, different providers often charge vastly different amounts for the same services. Prices for minor procedures like vasectomies can vary by hundreds of dollars or even a few thousand within the same geographical area, depending on whether the surgery is performed at a doctor’s office, a specialized clinic, or a general-purpose hospital. When it comes to major operations like joint replacements, CABG surgeries, and stent implantations, the differences are even larger.

In theory, patients could put overpriced providers out of business by refusing to use them. In reality, patients who are covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance don’t care all that much about costs, because they aren’t responsible for their bills. They’re only on the hook for copayments and deductibles. Because the dollars they might save by using inexpensive providers would help only other people, consumers have no real reason to shop.

Reference pricing alters this dynamic. By requiring patients who use overpriced providers to pay extra, it discourages profligacy. It also tells providers who want to hold onto their patients and attract new ones that they will have to compete.

Reference pricing is an incomplete strategy, however, because it is all pain and no gain. It discourages insureds from using providers whose charges exceed the reference price, but it does not reward them for using providers who charge less than the reference price. Even if the reference price seems like a good deal, some doctors or hospitals might be willing to undercut it. It would be to an employer’s advantage to learn that these providers exist, but reference pricing arrangements give workers no incentive to find them because workers gain nothing by using them. All of the money saved goes to the employer.

It may help to put the point this way. The reference pricing approach assumes that, below the reference price, employers know more about prices than workers do and can bargain over prices more effectively. Perhaps that’s true sometimes or even often. But is it true always? There’s no reason to think so. Workers may often learn things that their employers don’t know because they meet with providers directly. Employers should therefore treat workers like their eyes and ears and take advantage of the information they gather.

Because workers can deal directly with providers over instances of care, they may have opportunities to bargain for better prices too. Employers could easily take advantage of this possibility by encouraging workers to be good shoppers. They need only give employees a portion of any discounts they obtain on reference prices. For example, if a worker negotiated a deal on a minor operation that reduced the employer’s cost by $500, the worker might receive a check for $250. The employer would still be better off, and it would also learn that a provider exists who is willing to deliver a service for less than the reference price.

This isn’t just pie in the sky. A company called SmartShopper contracts with employers to provide information and financial incentives to employees, encouraging them to receive care at high-quality facilities that charge less. The New York Times reports that SmartShopper gives workers a list of providers in their network and rates them on the basis of quality. It then provides cash incentives to use lower-cost providers: “The incentive size depends on the care being performed and the difference in cost compared with other options. A blood test may garner a $25 reward for a worker picking a lower cost provider. Meanwhile, someone getting bariatric surgery, which can cost upward of $20,000, could get a $500 check.”51

Sharing the upside with workers will also help foster a virtuous dynamic by enabling an employer to turn its workforce into an army of motivated shoppers. In times when wages are stagnant and the cost of complicated procedures is high, it’s easy to imagine workers calling providers in their areas and asking them to beat a reference price. Workers may not even have to make phone calls. Wanting to gain their business, local providers who know that employees share in discounts may advertise their willingness to beat reference prices or publicize their fees. This would reveal information that an employer could use to advantage in the next round of negotiations with the reference provider.

Employers could also help workers shop more effectively by taking two additional steps. First, they could require providers that want to be picked as the reference price benchmark to submit all-inclusive prices, like those posted by the Surgery Center of Oklahoma. Second, they could post the submitted information on websites for use by their workers and others. This would make it easier for employees to ask other providers to price the same bundle, and the information they gather could be posted on the company website as well.

The amazing thing is not that competition works in health care. It reduces prices and improves quality everywhere it is tried. The amazing thing is that the health care sector has stifled competition for decades and, by doing so, has pocketed trillions of dollars while providing shoddy care. This can and should change. By threatening to take their business elsewhere—which may be to providers in other countries, states, or cities—and by acting on incentives to use providers who offer better services for less, American patients can force providers to compete. When they do, health care will quickly become cheaper and better.