THE BRITISH GENERALS IN BESIEGED BOSTON were fed up to the teeth with their situation. Here they were with 6,000 of King George’s troops, the finest in Europe, surrounded by hordes of peasants armed with old muskets and fowling pieces. The three major generals—William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne—had arrived on 25 May 1775 to receive a rude introduction to the facts: scarcely five weeks before, the rebellious farmers of Massachusetts had chased 1,800 of General Gage’s best troops all the way from Concord to Charlestown Neck, across from Boston, where they had collapsed like exhausted sheep while their officers counted their 273 casualties. The next day the colonists sealed off the city. The siege of Boston had begun.

Now, in early June, the three generals had urged on General Gage, in his dual role of governor and military commander, an operation plan designed to snatch the initiative from the rebels and break up the siege. The key to the plan’s success was to be the seizure and fortification of Dorchester Heights. The heights, thus secured, would not only ensure British domination of the port and city but would provide a base from which garrison forces could attack and roll up the besieging American force from the south. By 13 June, however, the American Committee of Safety, which was overseeing affairs in Cambridge, had already received a complete report on the proposed operation, due in great part to Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne’s mouth, which was at times as big as his military ambitions.

The committee’s deliberations on 14-15 June were actually a council of war that focused on countermoves to defeat the British sally on Dorchester Heights. The committee resolved that “Bunker Hill in Charlestown be securely kept and defended, and also some one hill or hills on Dorchester neck be likewise secured.” Since it was deemed impossible to do both, occupying Bunker Hill would serve as an immediate counter-threat to the British seizure of Dorchester Heights. So the high ground on the Charlestown peninsula would be the immediate objective for the colonists.

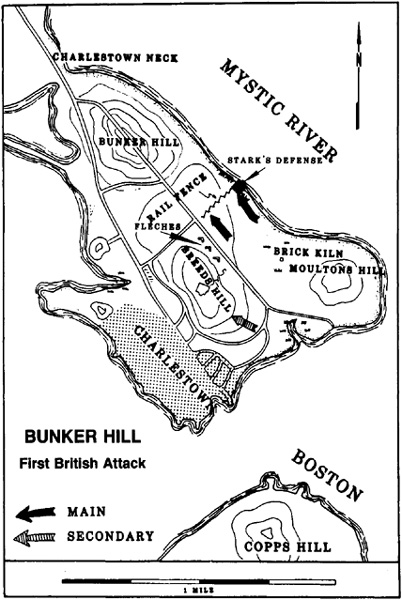

The map shows the peninsula, somewhat less than a mile and a half long and hardly three-quarters of a mile wide at its midsection, suspended like a bulging hornet’s nest from Charlestown Neck, and bounded by two rivers: the Charles on the west and the Mystic on the east. The chief features of the peninsula, other than Charlestown itself, were its three hills and the neck. On the east lay Moulton’s Hill, actually a knoll only 35 feet high. In the south center was 62-foot-high Breed’s Hill. On the north was flat-topped Bunker Hill, no feet in height. Charlestown Neck was an isthmus, narrowing to only about ten yards at some points, and so low that at high tide it was sometimes inundated.

After taking his direction from the committee, the colonists’ commander in chief, General Artemas Ward of Massachusetts, ordered the occupation of Bunker Hill to begin on the night of 16-17 June. It was to be achieved by a detachment of about a thousand men from the Massachusetts regiments of Colonels Prescott, Frye, and Bridge, along with a two-hundred-man Connecticut company commanded by Captain Thomas Knowlton. The detachment also included an “artillery train” of two four-pounders and forty-nine men, commanded by Captain Samuel Gridley. In overall command was Colonel William Prescott, a most fortunate choice to direct such an operation.

Prescott paraded his men on Cambridge Common at 6:00 P.M. on 16 June. Christopher Ward, in The War of the Revolution, has passed on the graphic description of an eyewitness to the formation on the common:

To a man, they wore small clothes, coming down and fastening just below the knee, and long stockings with cowhide shoes ornamented by large buckles, while not a pair of boots graced the company. The coats and waist-coats were loose and of huge dimensions, with colors as various as the barks of oak, sumach and other trees of our hills and swamps, could make them and their shirts were all made of flax, and like every other part of the dress, were homespun. On their heads was worn a large round top and broad brimmed hat. Their arms were as various as their costume; here an old soldier carried a heavy Queen’s arm, which had done service at the Conquest of Canada twenty years previous, while by his side walked a stripling boy with a Spanish fusee not half its weight or calibre, which his grandfather may have taken at the Havana, while not a few had old French pieces, that dated back to the reduction of Louisburg. Instead of the cartridge box, a large powder horn was slung under the arm, and occasionally a bayonet might be seen bristling in the ranks. Some of the swords of the officers had been made by our Province blacksmiths, perhaps from some farming utensil; they looked serviceable, but heavy and uncouth.

After their preparation, including prayers by the president of Harvard College, the Reverend Samuel Langdon, the detachment formed column and marched off about 9:00 P.M. heading eastward on the road which connected with the road running southeastward to Bunker Hill. The men and their company officers not only marched in the dark, they were equally in the dark about their destination and mission. Prescott led the way, keeping the same silence he expected of his men. At Charlestown Neck Prescott was joined by Brigadier General Israel Putnam of Connecticut, who brought wagons loaded with fascines (bundles of wood bound together) and empty hogsheads to be filled with earth and used to form the walls of a fort, and entrenching tools. After detaching Captain John Nutting’s company from Prescott’s regiment and sending it to Charlestown as a covering force, Prescott led the column over Bunker Hill and halted on its southeast slope.

Prescott then called the senior officers together for an informal command conference. No record was kept of what was said, but we can assume that there were lengthy and heated arguments about where to start entrenching—on Bunker Hill or on Breed’s Hill. We do know that the discussion between Prescott, Putnam, and others, including Colonel Richard Gridley, the army’s chief engineer, may have lasted for as long as two hours. Prescott had already pointed out that his orders were to fortify Bunker Hill, but there were arguments for taking over Breed’s Hill first. Being nearer to Boston, it commanded any approach from a landing on the south end of the peninsula, and it could therefore constitute a first line of defense as a buffer to Bunker. Finally, an impatient Gridley told the group that time was wasting. The decision was then reached to fortify Breed’s first, with Bunker as backup as time permitted. It was a sort of committee compromise, and as such was to lead to unexpected consequences.

Prescott led the column to Breed’s Hill, where Gridley traced out the lines of a square redoubt of about 132 feet on a side, and the men began digging about midnight. These “embattled farmers” may not have been soldiers, but they were diggers, accustomed to putting their backs into it with pick and spade. And dig they must, for only four hours remained until first light, when the whole works would be revealed to the sentries on the British warships below them in Boston Harbor. Prescott kept relays working feverishly, and it may be assumed that Putnam was there urging men to dig for their lives, no doubt recalling his words to Artemas Ward at the council of war the day before: “Americans are not at all afraid for their heads, though very much afraid for their legs; if you cover them they will fight forever.” Putnam stayed until about 3:00 A.M., when he decided to ride back to Ward’s headquarters in Cambridge where his own battle would begin.

With the work well under way, Prescott ordered Captain Hugh Maxwell of his regiment to take a force and join Captain Nutting in Charlestown. From there they would patrol the shores of the peninsula to protect them against any British landing parties. Not content with that, Prescott later, before dawn, twice personally reconnoitered the shoreline. Under other circumstances it could have been called a romantic June night—quiet and warm under a starlit sky. Prescott and his executive, Major Brooks, could make out the forms of the British ships whose identities and anchorages they had memorized: to their far left lay the sloop Falcon with her fourteen guns, then the frigate Lively with twenty guns, off to their right lay the Glasgow with twenty guns, and in the distance was the ship of the line, the sixty-four-gun Somerset. As Prescott and Brooks moved along the silent shore they could hear across the calm harbor the routine cries of the British sentries on the ships. Assured that all was well, Prescott rounded up Maxwell and his men and returned to the redoubt. By then it was almost first light.

William Prescott was forty-nine years old, a fine New England rock of a man, still in his prime, over six feet tall and as strong of mind as he was of body. His jaw was firm and well rounded, giving his face a look of determination, and yet kindliness. He was direct of speech, though always courteous, as befitted his station of gentleman farmer. Always self-possessed, he had a natural air of command and a way of exacting respect without being domineering. His courage and coolness under fire had been first noticed by his superiors when the British had wrested Louisbourg from the French in 1745. There he had been offered a regular commission in the British army, a rare opportunity indeed for a provincial lieutenant. He had declined that offer, and at the end of King George’s War had retired to his farm in Pepperell, Massachusetts. Prescott preferred that life, having been born to it in a family of wealth and prestige. He had improved upon a limited education through his love of reading. In 1775 he raised a regiment, was made its colonel, and arrived at Concord too late to fight. As we picture him now on the wall of the redoubt, with the first light of dawn breaking over the Mystic River, he looks an elegant figure in his light blue uniform, his balding head covered with a wig and crowned by a three-cornered cocked hat.

A few minutes after dawn the guns of HMS Lively opened fire on the redoubt. After a few ranging rounds, however, the frigate’s artillery fell strangely silent. Prescott took advantage of the silence to take stock of his situation. He decided to start work on a breastwork to protect the vulnerable left flank of the redoubt. He got a work detail going on a straight breastwork about 100 yards long, extending from the southeast corner of the redoubt down toward the marsh at the foot of the hill.

MEANWHILE, BRITISH GENERAL GAGE HAD CALLED a council of war that same morning of 17 June. Howe, Clinton, and Burgoyne were there, along with other senior officers. Clinton first proposed an immediate attack on the Charlestown peninsula: Howe to make a frontal holding attack from the east, while Clinton with 500 men would land on the peninsula just south of the neck and behind Prescott’s redoubt to cut off the American force. The other generals opposed Clinton’s plan as unsound, for it risked placing a British force between the Americans on the peninsula and those on the mainland. Howe then proposed an alternate method of attack: cut off the Breed’s Hill redoubt by pinning down its defenders with a frontal attack, while an enveloping force would march up the east shore of the Mystic and attack the redoubt’s left rear. Gage approved Howe’s plan and ordered it put into effect that day. It was decided to wait for high tide. “High Water at two o’clock in the afternoon,” Howe recorded in a letter to his brother.

Howe, as senior officer, was to lead the expeditionary force, with Brigadier General Sir Robert Pigot second in command. The force of about 1,500 infantry and twelve guns would be moved in barges, due to shove off from Boston at high noon. To be held in reserve at the Battery in the city were 700 infantry of the 47th and 63rd regiments, as well as the major elements of the 1st and 2nd battalions of marines.

The concept of such an attack was not unsound. If it had been carried out at the earliest possible moment, British landing forces would have had ample room to maneuver and possibly capture both hills. The execution, however, was fatally flawed by a six-hour delay, which gave the Americans valuable time to extend their fortifications and make additional deployments. In the actual event there was neither adequate maneuvering room nor concentration of force at the right time and place.

WHEN THE Lively guns opened fire, the noise awakened Connecticut General Israel Putnam, who pulled on his clothes and galloped off toward Breed’s Hill. This kind of riding was to characterize Putnam’s performance; to those who saw him on this day of battle, he seemed to be everywhere at once. Israel Putnam was not just a brigadier general in Connecticut’s militia; he was literally a legend in his time. Old Put—he was fifty-seven in 1775—was a household name due to the legends that had grown about him. There was his killing of a great wolf in her den, and also a true story of his being about to be burned at the stake by Indians when a French officer rescued him just in time to save his hide. Then there were tales of his adventures in the Havana campaign in 1762 when he was shipwrecked on the Cuban coast; and so on. In New England myth and legend he had become a real-life Revolution-era equivalent of Baron Munchausen.

Putnam was only five feet six in height, but he was built like a great brown bear. Yet his open, jovial face and halo of unruly gray hair made him resemble not a warrior but a generous, openhearted, dyed-in-the-wool American hero. He was immensely popular. Of generalship, the planning and execution of strategy, however, he was totally ignorant. He did possess the qualities of courage, energy, and aggressiveness, but those also represented his limit. Several historians have suggested that he would have made a splendid regimental commander—and so he should have remained.1

It was fully daylight when Putnam rode up to the redoubt and conferred with William Prescott. There he learned that Prescott’s men were laboring and would be doing so for hours, without resupply of food, water, and ammunition. Each man had only the powder and shot he had carried with him. Prescott was not the kind of leader to ask for relief, but Putnam could see that Breed’s Hill must have resupply and reinforcements if it were to be defended. By about 5:30 he was on his way back to Cambridge.

IN CAMBRIDGE A DEMANDING PUTNAM FOUND Artemas Ward chiefly concerned over the danger to his center at Cambridge and the threat of the same attack to cut off American forces at Charlestown Neck. Ward has been criticized for not taking immediate action to throw his reserves and meager stores into position where Putnam was demanding. But despite Putnam’s pleas, the commander in chief, who was also suffering from an attack of bladder stone, was adamant about not acting until the situation became clearer to him. As John Elting saw it: “Unlike Putnam, he [Ward] was not going to immediately mount his horse and ride off in all directions.” A disgusted Putnam left for Bunker Hill.

SHORTLY BEFORE 9:00 A.M. PRESCOTT HAD EXCHANGED his uniform, hat, and wig for his wide-brimmed farmer’s hat and linen banyan, the light coat meant for summer wear. He had just started to climb the six-foot redoubt wall for a look around when the British ships opened up with a concerted roar. This was no mere frigate’s broadside; the thundering chorus was joined by the twenty-four-pounder battery on Copp’s Hill on the northeast extremity of the Boston peninsula. Prescott looked around at his farmer-militiamen and saw white faces. Fears that could grow into panic must be squelched—now. So he mounted the parapet and calmly walked along its top until the men picked up their tools and went back to work.

An hour later Prescott’s senior officers were demanding some kind of relief. The men were exhausted after ten hours of constant digging, and the bombardment continued. A cannonball had smashed the last water cask; there was no food for the hungry men; and now came the news that the British troops in Boston were assembling around the waterfront, certainly to cross the harbor and attack their redoubt. Wasn’t it time that fresh troops relieved them?

Their iron-souled commander refused: “The men who raised these works were the ones best able to defend them; their honor required it.” Prescott did relent to the extent of dispatching Major Brooks to Cambridge to ask for supplies. Brooks asked Captain Samuel Gridley of the artillery for a horse and was refused. A disgusted Prescott sent Brooks on his way to trudge the four long miles to Cambridge on foot.

PUTNAM’S RIDE OVER BUNKER HILL MUST HAVE convinced him that entrenchment should begin at once on that position also. He rode to Breed’s Hill to get the men and tools from Prescott. This, with all of Prescott’s other troubles, was a little too much, and he was not bashful in protesting to Putnam that the men who left with the tools would not come back. “They shall every man return,” Putnam assured him. Prescott had to give in, and Captain Bancroft, who was a witness to the scene, tells us that “an order was never obeyed with more readiness.”

Not one who left ever came back. Looking about him, Prescott must have been reflecting, with understandable concern, that out of his original detachment he could now count on less than 500 men to man the redoubt and the breastwork!

AFTER GETTING THE WORK STARTED ON BUNKER HILL, Putnam rode again to Cambridge to renew his pleas for supplies and reinforcements for Prescott. During a violent session Putnam gained an ally in Richard Devens, who brought the Committee of Safety in for a vote. The vote was overwhelmingly in favor of Putnam, and a grudging General Ward yielded to the extent—mere temporizing in Putnam’s view—of ordering Colonel Stark at Medford to detach 200 of his New Hampshire regiment and have them march at once for Breed’s Hill.

Stark dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Wyman with the troops to reinforce Prescott. He also put the remainder of his oversized regiment on alert, and gave similar instructions to the other New Hampshire regiment under his nominal command, that of Colonel James Reed, camped near Charlestown Neck.

Being a frontier province, New Hampshire was always short of supplies. Now ammunition was Stark’s chief concern. He sent a detachment to Cambridge, which rounded up a little powder, and for lead brought back strippings from the organ of the Cambridge Episcopal Church.

These New Hampshiremen were mostly frontiersmen who had known all about Indian fighting and hunting from boyhood. According to Robert Hatch, “Most of Stark’s recruits were crack shots . . . they could bring down a squirrel from a high branch or stop a partridge in flight” (“New Hampshire at Bunker Hill”). The statement should be taken with a bit of salt, because the musket was still the universal New England firearm; the rifle was unknown there.

What of New Hampshire’s leader? As his men saw John Stark, he was forty-six, lean, tough as frontier leather, and direct of speech. This hatchet-faced Scotch-Irish Presbyterian had been raised on the frontier as a trapper whose attendant skills included Indian fighting. Captured and held captive by Indians at the age of twenty-four, he earned the respect of senior warriors when he had to run a gauntlet of clubs, armed only with a pole. Stark walked through, dealing out blows himself, all the while singing out, “I’ll kiss all your women” (if he said or meant more than kissing, we have to rely on the story). Later, when ordered to hoe corn, the lot of squaws and captives, Stark threw his hoe in the river, declaring, “It is the business of squaws to hoe corn and not that of warriors.” The chiefs ransomed him as soon as they could. In the French and Indian War Stark rose from second lieutenant to captain in the famed Roger’s Rangers. His exploits in forest forays and half dozen battles earned him a reputation to match that of Old Put. In 1759 he returned to his province to found Starksville, later renamed Dunbarton. In 1775 he raised the regiment that he now commanded, with his headquarters in Medford.

Now Stark and his men were ready for action. He set his men to pounding the lead into crude bullets because no bullet molds were on hand. Then, at about 1:30 P.M. he led his regiment out of Medford, on Ward’s order, on his way to pick up Reed’s regiment near the Neck.

DURING THE NOON HOUR PRESCOTT MUST have had mixed feelings about his situation. The day of 17 June was clear and hot, with the temperature climbing toward the mid-eighties and only a light breeze, not enough to clear the dust-clouded air in the redoubt. But the redoubt was being finished off with banquettes, the firing steps essential to firing over the redoubt walls, and the breastwork would soon be completed, too.

Prescott’s satisfaction was overshadowed by the condition of his men. Young Peter Brown, a company clerk in Prescott’s regiment, has left us an insight: “We began to be almost beat out, being fatigued by our Labour, having no Sleep the night before, very little to eat, no drink but rum, but what we hazarded our lives to get, we grew faint, Thirsty, hungry and weary.”

Prescott’s worries were not confined to shortages of food and water. Three hours before, the British cannonade had resumed with a sort of harassing fire. At first the incoming shells had not cowed the men working outside the walls, but their initial casualty created a crisis. Young Asa Pollard of Billerica had his head blown off by a cannonball, to the horror of his comrades. When Prescott answered their pleas of what to do, with a curt “bury him,” they clustered around the body to hear prayers from a self-appointed chaplain. After two attempts to get them back to work, Prescott threw up his hands and let them finish their rites.

Then there was the matter of the artillery: there were no solid firing platforms and no embrasures made in the walls—and no tools to make them. Prescott finally ordered Captain Gridley—Colonel Gridley’s son and a captain by virtue of that relationship alone—to move his two guns out near the breastwork where, in Peter Brown’s words, Gridley “swang his hat three times to the enemy.” Thereafter Gridley displaced his battery to Bunker Hill.

Shortly after noon Prescott’s previous worries were dwarfed by the impact of a renewed bombardment that made the morning’s seem like mere artillery practice. It soon reached the highest intensity of the day. Falcon and Lively blasted the ground around Moulton’s Point and east of Charlestown, the mighty Somerset’s sixty-four-gun broadsides were joined by two floating batteries and the twenty-four-pounders on Copp’s Hill, while Glasgow, Symmetry, and two gunboats kept fire sweeping across the Neck. The ships’ broadsides could bring to bear forty guns at a time. The colonials were fearful: was all this artillery preparation a signal that the British were about to launch an amphibious landing?

The answer soon came. Before the weary eyes of the militiamen—and thousands of citizens who crowded the rooftops of Boston and the hillsides above the Charles and the Mystic—a double column of landing barges, fourteen in each, appeared rounding the north end of Boston, headed for Moulton’s Point. In its martial splendor and military might, the spectacle seemed to embody the threat that the Old World was posing to the hopes of the colonies. The midday sun sparkling on the waters of the harbor was reflected back from the glittering steel of hundreds of bayonets and musket barrels, made even brighter by the scarlet ranks massed in the boats.

Prescott may have been as impressed as the others, but there can be no doubt that his no-nonsense eye was estimating the size of the force in the boats: perhaps somewhere between one and two thousand infantry, with several fieldpieces in the leading boats. And he knew how the brave martial display could quickly disintegrate into the reality of combat, producing results like the headless corpse of Asa Pollard, buried down there in the ditch of the redoubt.

SIR WILLIAM HOWE’S LEADING ELEMENTS began landing around Moulton’s Point about 1:00 P.M. While his troops were marching to deploy in the classic British order of three lines, Howe took time to study the terrain and the enemy. His professional sensibilities were jarred at his first look. The colonials’ position had been greatly improved since early morning. The single redoubt had been extended eastward, thus cutting down Howe’s room for maneuver, although there was still enough space for an envelopment on the east side toward the Mystic. And the breastwork was not the only change: he could see a mass of men milling around on Bunker Hill, probably some sort of reserve force. As Howe watched, a long column began coming down the forward slope of Bunker Hill, heading toward the Breed’s Hill redoubt.

Howe saw the potential danger of getting his present force, now forming on Moulton’s Hill, caught between the two hills while making an envelopment of Breed’s. He realized that he would need more troops (his reserve waiting at the battery), and he gave orders to return the barges to bring up the reserve. At the same time he began pushing forward two covering forces from his present position. Four light infantry companies were deployed in the low ground in front of his main body, while General Robert Pigot was ordered to move to the left (west) with the battalion companies of the 38th and 43rd regiments (sixteen companies) to an area below the southern extremity of Breed’s Hill. Howe’s last order then was to let the men fall out in place and break out their rations for the noon meal.

PRESCOTT HAD WATCHED THE BRITISH INFANTRY companies land and form into massed lines, and by 1:30 P.M. he saw clearly the threat to his left (north) flank. Between the end of his breastwork and the Mystic there was a wide gap, only partially protected by the marsh on that side. Already, British light infantry companies were moving down the forward slope of Moulton’s Hill to come into skirmish lines. Prescott at once ordered Captain Knowlton to take his Connecticut company, along with Captain Calender’s two fieldpieces, and oppose them.

Prescott had good reason to trust Knowlton. Like Stark, Knowlton had been an Indian fighter, having gone off to fight the redskins and the French as a boy of fifteen. He had been a lieutenant at seventeen with a reputation for courage and leadership. He was now thirty-five and, like Stark, tough and lean. He was making his decision as he marched, having observed the British deployments while standing alongside Prescott. Knowlton’s eye settled on a rail fence running parallel to Prescott’s breastwork and about 300 yards to its rear, extending to the bank of the Mystic. He ordered his men to stack arms and begin tearing out the rails of nearby fences, which he then used to fill the gaps in his chosen fence, whose rails rested on posts set in a stone base. The men then stuffed loose hay between the rails to give it the appearance of a solid breastwork. It proved good enough to fool General Howe, who later described it as a breastwork “which effectively secured those behind it from Musketry.” Knowlton did not yet know it, but he had prepared a defensive position whose tactical importance would equal that of Prescott’s redoubt. Yet while Knowlton was checking out his fields of fire across the meadows to his front, Captain Callender, following Gridley’s precedent, quietly decamped with his guns for Bunker Hill.

Since he had left Prescott around 11:00 A.M., Israel Putnam was learning the hard way the frustration that came to a Connecticut general who sought to hurry forward Massachusetts troops and officers not legally under his command. He had raged back and forth between the Neck and Bunker Hill, even riding across the Neck under fire as an example, but the chaotic mass of intermingled regiments was too much for him, especially when he couldn’t get their officers to lead them. The occasional ships’ cannon shot, really a slow interdiction fire, was all it took to cow the green militia.

Putnam’s temper didn’t improve when he bumped into Captain Callender and his two guns heading across Bunker Hill. When the general asked why he was retreating, he got an evasive answer from Callender, a mumbled reply about being low on ammunition. An irate Putnam checked the side boxes on the gun carriages to find them nearly full. When Putnam ordered him to make a 180-degree turn toward Breed’s Hill, Callender refused. But Putnam’s pistol muzzle at his head quickly convinced Callender that indeed Breed’s was a logical destination.

Putnam, however, was rewarded when he looked down the forward slope of Bunker Hill to see in the distance a most pleasant sight: Connecticut men under a resourceful leader building that rail-fence breastwork smack in the path of any British force attempting to flank Prescott’s position. He also encountered Stark’s Lieutenant Colonel Wyman and directed him toward Knowlton’s position.

IN CAMBRIDGE NEWS OF THE BRITISH LANDING had moved Ward to order forward all the forces he could muster. The area north of the Neck became a madhouse of activity as nine Massachusetts regiments were ordered forward, thereby increasing the mass of confused companies who were blocking the road onto the Neck. Stark led his regiment through the congestion like the bow of a ship breasting the waves. He had sent forward Major Andrew McClary to open a path, and this six-foot-six frontiersman took pleasure in the task. “If Massachusetts didn’t need to use the road just then, would they please move over and let New Hampshire through?” The Massachusetts troops stepped aside.

Captain Henry Dearborn, marching alongside Stark, nervously “suggested the propriety of quickening the march of the regiment, so it might sooner be relieved of the galling crossfire.” In Dearborn’s words, “He fixed his eyes upon me, and observed with great composure: ‘Dearborn, one fresh man in action is worth ten fatigued ones’ and continued to advance in the same cool and collected manner.” When Stark passed Putnam on the forward crest of Bunker, he was met with an order—a request?—from the latter to detach enough men to finish entrenching the hill. Stark ignored him. Surveying Knowlton’s position and finding it much undermanned, he paused only long enough to make some brief remarks to his men, then led them on to the rail fence.

After taking command of the fence line and assigning his officers the tasks required to bolster the position, Stark went down to survey the end of the fence line at the bank of the Mystic. Looking down the steep eight-foot bank, he saw a beach made narrow by the same high tide that had carried the British boats to Moulton’s Point. Recognizing at once that the beach could still support a column of British infantry moving to envelop the left flank of the rail-fence position, he immediately detailed enough men to haul stones from the riverbank and nearby fences to build a waist-high breastwork in prolongation of the rail fence.

Stark’s final act in organizing the position was based on his experience with Roger’s Rangers and the battles of the French and Indian War. He knew that the disciplined British infantry could take the shock of a defender’s first volley and close with the bayonet before the defenders could reload—a matter of fifteen to thirty seconds. Stark therefore formed the whole of his command into three ranks, with strict orders that each rank would fire only on order, then step back to reload, thus leaving the enemy no respite between volleys. Stark was well aware that his volley system would eventually degenerate into firing by individuals, but he hoped he could count on pouring enough volleys into the British to smash their leading ranks to pieces before that occurred. To make his point clear he paced out fifty yards to the front, drove a stake into the ground, and gave orders that no man was to fire until the British front rank reached the stake. Stark was ready.

PRESCOTT, VIEWING THE BRITISH DEPLOYMENTS, now picked up a redcoated column moving from the landing beach to take up position nearer Charlestown. Ever since he had detached Knowlton to cover his left, he had grown equally concerned about his right. He sent Lieutenant Colonel John Robinson with 150 men to strengthen the defense in Charlestown, in order to secure the redoubt on its right (west) side. Robinson’s departure left Prescott with about 150 men in the fort and 300 to 500 at the breastwork.

Other developments demanded Prescott’s attention. Some time after Robinson had gone, Prescott noticed the smoke of arching trajectories left by shells from the British ships and the Copp’s Hill battery. Such “tracers” were made by red-hot shot and carcasses, a type of shell filled with combustibles and pierced with holes. In minutes fires were breaking out in Charlestown houses, and soon the whole town was ablaze. Still, Prescott’s men in the doomed town would be able to scamper away and take cover in barns or behind stone walls, from which they could continue to delay any British flanking attack.

To his left Prescott could see that the three small flèches—V-shaped, hastily made breastworks pointing toward the enemy like arrows, hence their French name—were being occupied by colonial reinforcements. Later he was to learn that the flèches had been ordered constructed by Colonel Gridley and were manned by Massachusetts men from the regiments of Colonels Doolittle, Brewer, and Nixon.

By 3:00 P.M. the panorama of the coming battle was unfolding under Prescott’s eyes. To his left rear, the rail fence—he couldn’t see the beach below the river bank—and the flèches were lined with the ranks of waiting American troops. In front of the flèches and Stark’s fence, the sweep of the meadows was broken only by the rectangles of fenced-in fields and an occasional shade tree. To Prescott’s immediate left, newly arrived reinforcements were being posted along the breastwork while the “older” men were taking their ease on the grass behind it; it was the only rest they were to get after their morning’s labor. Others were sorting out their ammunition for a final inspection. The militiamen nearest Prescott had emptied their pouches and pockets of bullets, which they were counting into their broad-brimmed hats, estimating how long their powder charges would last.

From Prescott’s vantage point the whole of the American positions, excepting, of course, Stark’s beach, could be discerned. From left to right there was first the rail fence, then—between the fence and the redoubt—the flèches, next the redoubt crowning Breed’s Hill, and finally the scattered elements between the redoubt and the shores of the Charles River on the right.

Now the British movements to his left front caught Prescott’s eye. The light infantry north of Moulton’s Hill was reforming into a single, long, scarlet column and was marching off toward the Mystic. Other columns were marching from Moulton’s Hill toward the Brick Kiln and deploying into line on the slopes being cleared by the light infantry. Directly in front of Prescott, battalion columns had moved up from the landing beach and were fanning out into precise three-deep lines. This force was obviously forming for an attack on the redoubt, probably to begin in concert with the lines massing north of the Brick Kiln.

In the background the leaping flames in Charlestown were giving off clouds of dark smoke that were drifting slowly eastward before a light summer breeze. Over it all the rolling roar of the British guns continued to drown out all other sounds. Now they were joined by the British battery of six-pounders that had gone into firing position on the edge of the marsh near the Brick Kiln. Its fire was apparently being directed against the rail fence and flèches, with no discernible effect.

In the redoubt and along the breastwork the men were silent, engrossed like their commander in the spectacle that was closing in on them. And like Stark’s men, Prescott’s were ready.

HOWE’S RESERVE LANDED NEAR PIGOT’S FORCE south of Breed’s Hill and immediately marched up to reinforce the waiting forces. While awaiting his reserves Howe had formulated his plan of attack. In contrast to the unimaginative and simple frontal assault that has so often been pictured, Howe’s plan was to attack in two wings. Pigot, on the left, would pin down Prescott’s men in the redoubt while distracting them from Howe’s main attack, and Howe would personally lead the other wing to envelop and encircle the American left. In his scheme of maneuver Howe was to attack the rail fence with the grenadier companies2 in the first line, followed by the battalion companies of the 5th and 52nd regiments in the second line. But the key to his attack lay with the eleven light infantry companies he was drawing off to his right to form an assault column, which would move rapidly along the beach to envelop the Americans at the rail fence and then, in conjunction with his frontally attacking force, move to outflank the Americans on Breed’s Hill. Howe’s attack was to be preceded by an artillery preparation from the ships, directed at the redoubt and breastwork, and supplemented by his field artillery pieces, which were pushed forward to fire on the American positions.

Howe’s overall plan shows the tactical skill that he would employ time after time to defeat Washington on the battlefield. However, he was not yet aware that the Americans in the redoubt and the rail fence—Howe and his officers could not see Stark’s men on the beach—were backed up by a few key American officers with combat experience who knew how to make every bullet count, even though those bullets were fired by the greenest of militia.

JOHN STARK HAD WATCHED THE BRITISH BATTERY open up, and the few round shot that had come his way had whistled overhead. After a few rounds the battery ceased firing, leaving Stark to wonder at the sudden lull.3 Without waiting to puzzle over such things, however, he strode on down to the beach to take post behind his three-ranked line. Now the Americans, muskets primed and hammers at half-cock, could only wait for the redcoats to appear.

Some few minutes before the enemy came in sight, Stark and his New Hampshiremen heard the rattle of marching drums. There was an eerie pause as the men heard the sound but did not see a single soldier. Suddenly there they were, a close-ordered column of fours coming around a curve of beach. There were officers in the lead and alongside the column, and Stark could see the rhythmic swing of their sword arms, moving in time with marching beat. Now he could make out the short leather caps of the soldiers, and he realized that they were light infantry.

Stark had already given his order to “fire at the top of their gaiters or the waistcoat,” and it was being obeyed, for he could see the barrels of the front-rank muskets lowered as his men took aim. The British officers under the Americans’ aiming eyes were shouting commands, and the files of the column fanned out to deploy into line. All movements were being made at the double in disciplined silence. Commands rang out again, and the forward company came on, muskets leveled at charge bayonet. To Americans, who were seeing them for the first time over their leveled musket barrels, the steel hedge of bayonets was a fearsome sight.

When the scarlet jackets surged past his stake in the sand—curiously, Stark noted the stake being knocked over by a charging infantryman—he shouted his command. “Fire!” The volley crashed out like the firing of one great musket, every trigger pulled in the same instant.

Stark’s eyes strained to see through the drifting haze of white smoke. In seconds he could make out the sight: whole ranks of light infantry had been leveled as though a giant hand had swept them down to the sand. Here and there wounded men were trying to rise between heaps of bodies. Yet British discipline held fast, and a second company came thrusting its way through the remnants of the first, officers shouting the men on, eager to exploit the precious seconds it would take those farmers to reload.

These professionals were about to get the shock of their lives. When the new company was still bounding over the dead and wounded, Stark gave his second rank the command to fire. Their scythe of fire cut down the second company with the same slaughter that had wiped out the first. The cries of the wounded rose again after the stunned silence that followed the first volley.

Both British charges had been designed to depend on the bayonet, and a third was deploying to repeat the attempt at bayonet point. Stark, peering through the clearing smoke, watched the scattered survivors, often as few as one man in ten, falling back, to be passed over by the surging rush of a third company coming on with the same dash as its predecessors. And with Stark’s third volley the result was a repeat of the same slaughter. This time, however, the British officers made no attempt to rally platoons or companies; nowhere were there enough men standing to form one line. The repeated sheets of fire were more than even British infantry could stand.

Now Stark’s men were firing at will, the better shots picking off rank and file whenever their aim found them. Restraining a few hotheads who wanted to pursue their rapidly withdrawing enemy to get in another shot, Stark and his officers herded them back into ranks, and he went forward to count the dead. The redcoat light infantry had carried off their wounded, leaving only the dead. There were ninety-six in all, lying “like sheep in a fold.”

ABOVE THE BEACH, IN THE FIELDS THAT STRETCHED for a quarter mile beyond the rail fence, the other British attack was developing. The defenders’ flimsy breastwork was manned by the men of Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, perhaps 1,500 in all. They had listened to the crashing volleys down on the beach; now it was their turn to take on a British attack.

This attack was not a charging rush like that of the light infantry. The long red lines were struggling forward in the afternoon heat, carrying the weight of a musket, sixty rounds of cartridges, three days’ rations, and rolled blanket—fifty pounds of marching order. Then too, their tight wool uniforms were anything but comfortable under the hot sun.

To the waiting militia their enemy seemed to be taking his own good time in advancing, as if to build on the Americans’ suspense. Actually, the British were having a time of it, being forced to clamber over or knock down fences and then wade through knee-deep grass, keeping their ranks dressed all the while. Veterans like Knowlton could see now that the leading three-rank line consisted entirely of grenadiers, their tall black bearskins fronted by regimental badges flashing in the sun. When the leading grenadiers realigned ranks, Captain Dearborn recalled that they did it “with the precision and firmness of troops on parade, and opened a brisk but regular fire by platoons.”

It was the “fire by platoons” that got the grenadiers into trouble. As they opened fire they were met with a heavy return fire that tumbled dozens of dead and wounded into the grass. The American firing began, in spite of their officers’ cautioning, by a few eager souls like Lieutenant Dana of Knowlton’s company, who fired, as he said, “with a view to draw the enemy’s fire.” (One wonders what John Stark was to say about this lame excuse, a palpable effort to cover up nervousness.) The grenadiers returned fire, though it may be doubted that it was as regular as Dearborn recalled it. In any case, most of the bullets of the British volleys whistled over American heads.

When the militia was brought to order by veteran officers such as Knowlton, fire was held as the British advanced again. To the New England farmers and village youths the scarlet wall of towering grenadiers was an incredible sight. What would it take to stop these massed ranks marching forward again with such precision?

The answer came when the grenadiers reached another fence only yards from the muskets leveled over the fence rails. Following a brief hesitation, the British began knocking down rails in their haste to get over the obstacle. Israel Putnam, waiting with sword in hand—once again where he figured he was needed most—saw that it was the right moment and bellowed “Fire!” This time a controlled volley crashed out, and the length of the rail fence was a solid sheet of yellow flame. Grenadiers were not knocked over singly; instead, great gaps were torn in their ranks, leaving the shaken survivors to fall back from the terrible fire.

The slaughter continued. To the incredulous Americans, the black-cocked hats and single white cross belts of battalion companies repeatedly appeared one after the other through the haze of powder smoke. It was the second, supporting line of the attack. The jumbled mass presented targets that the greenest militiaman couldn’t miss. The supporting battalions had come forward too fast, and were now intermingled with the shattered remnants of grenadier companies. Flushed with success, Connecticut farm boys and New Hampshire hunters were calling out eagerly to each other as they selected targets at will.

The disordered mass fell back of its own accord, despite the commands and pleas of the British officers. Heaps and rows of wounded and dying were left behind. In the colonial lines, officers were restoring order and getting men back into place. The veterans among the Americans knew that this local victory might mean only the beginning of prolonged combat, so an exhilarated Putnam remounted and rode back to Bunker Hill to hasten up reinforcements.

IT WAS ALMOST 3:30 P.M. WHEN PRESCOTT saw the next attack coming, this time against Breed’s Hill. When the long red lines came into view on the south slopes, he recognized the cocked hats of battalion companies. To his right front a mixed force was appearing. Some units wore the round caps of light infantry, other companies were in the bearskins of the grenadiers, and still others were clearly battalion companies. In the redoubt and behind the breastwork, Prescott’s men were feeling the same stomach-clenching fear that the men at the rail fence had felt. The rattle of the drums and the high-pitched shrill of the fifes were coming nearer. In the intervals between battalions could be seen the twin colors, king’s and regimental, carried high by ensigns. To the men crouching on the firing steps or braced against the breastwork it seemed unbelievable that this splendid sight could actually be coming against them. But it was.

On shouted command the scarlet ranks snapped to a halt and came to order arms. From the British right, platoon volleys cracked out, obscuring the ranks with their white smoke. Again the fire was too high, most of it passing overhead. Prescott couldn’t believe his eyes: what were the British up to, firing at distances of seventy to eighty yards? He had no time to think about it; nervous militiamen were beginning to fire back. Lieutenant Colonel Robinson mounted the parapet and ran along its top, kicking up any musket barrels he found being aimed.

New commands rang out, and the British ranks advanced up the hill. Prescott waited until they had closed within forty yards before he gave the order to fire. In the British front ranks the scene Stark’s unbelieving eyes had witnessed earlier was repeated: shattered ranks and falling casualties. This time, however, British officers remained in control and conducted a reasonably orderly withdrawal.

Prescott ordered a cease-fire. Enough precious ammunition had been fired away, and the enemy was getting out of musket range. Had this attack been a feint, a secondary effort? It was too early to know, but one thing was certain: this attack—so easily beaten back—would not be the last.

HOWE HAD LED THE ATTACKING LINES FORWARD against the rail fence. There he had personally witnessed the slaughter from the muskets of the militia, who had not only held their ground but had delivered such a deadly, sustained fire that his best troops could not stand against it. As he walked back, sword in hand, an aide was giving him the report of the disastrous failure of the attack of the light companies on the beach. His attempt at envelopment had failed as disastrously as the frontal attack he had led forward. Consequently his whole main attack had collapsed.

Still, plenty of time remained to reorganize and renew the offensive. Within a quarter of an hour, Howe had given his order and a new attack was under way. This time the light infantry companies, withdrawn from the beach and redeployed, would make a secondary effort against the rail fence while Howe and Pigot would make a new main attack against the redoubt, attacking simultaneously from the east and south.

STARK WALKED HIS LINE, CHECKING AMMUNITION and voicing words of encouragement where he thought it needed. The men, “blooded” now, were almost eager for a renewed attack. In less than half an hour the British obliged them. This time, as the deployed lines moved forward, they seemed to be having less trouble with the fences. Soon Stark realized why the enemy could come ahead so rapidly; the leather caps of the faster-moving, less-encumbered light infantry came into sight—perhaps the companies that had been at the rear of the column on the beach. Farther off and to his right, Stark could see columns of grenadiers and line companies moving obliquely across his front, apparently advancing on the flèches. For the moment he could ignore them; he would have his hands full with the attack coming at his fence. But he had full confidence in his men, and they had all been encouraged by the arrival of Captain Trevett’s two artillery pieces, now in position at the right end of the fence.

The lines of light infantry had crossed the fence 150 yards away and were coming on at a steady pace. New Hampshire and Connecticut men waited in silence, front-rank muskets resting on fence rails, second and third ranks standing with muskets at “poise firelock.” Then, to Stark’s surprise, the British suddenly halted and opened fire. It was too good to believe: a fixed target within easy musket range of no more than sixty yards. He shouted the command to fire.

For an incredible quarter hour the British infantry stood fast, firing and reloading in an attempt to exchange fire with the Americans. This was no even exchange, though. Volley after volley flamed over the rail fence, taking a more fearsome toll than that inflicted upon the first attack. When Stark could see through the smoke, the sight was shocking, even to him. Here and there a brave file still stood, firing with mechanical precision, but the huge gaps between those few files astounded Stark. Where companies had stood in solid ranks, as few as eight or nine men were left standing in some, in others, four or five.

It was more than any infantry could bear. Where Trevett’s guns had blasted holes in British ranks, the job had been finished by hundreds of muskets. Now those red-coated infantrymen who could were hastily falling back out of range, and Stark saw what appeared to be a high-ranking British officer walking, sword in hand, among the retreating men. The second attack, as anyone could see, had been smashed, not only in front of Stark’s position but also in front of the flèches, where windrows of British dead and wounded attested to the fact.

PRESCOTT HAD BEEN ABLE TO SNATCH a few minutes to observe the disastrous repulse of the attacks against the rail fence and the flèches before a renewed attack against his hill was mounted. To his front the British battalions marching up the slopes appeared to be the same as before. On Prescott’s right, however, it was a different story: the formations coming from that quarter seemed to have been heavily reinforced.

Prescott had been at his toughest in cautioning officers and men to hold their fire, and as these attacks came up the hill, his words had been effective. The men were confidently silent, and not a musket had yet been aimed. He waited “till the enemy advanced within thirty yards, when we gave them such a hot fire that they were obliged to retire nearly one hundred and fifty yards before they could rally.” That hot fire had covered the green grass of the hillsides with scores of red coats. There were a few American casualties, among them Sergeant Benjamin Prescott, who took a British bullet in the shoulder. He managed to hide his wound from his father, who was passing down the line below the banquette praising his men for their stout defense.

When his officers reported their ammunition count to Prescott, however, it was anything but encouraging. Many men would be able to fire only three or four more shots. Prescott ordered the cannon cartridges from the guns abandoned by the artillery to be slit open and the powder distributed, at best a token resupply. And there had been no resupply of anything from Cambridge: no food, water, or ammunition.

While the second British attack was being fought off, Putnam rode back to Bunker Hill, where he had stationed units of Massachusetts militia for the purposes of continuing the entrenching or to be prepared to move forward to reinforce the troops on Breed’s Hill or the rail fence. When he reached the top of the hill, Putnam’s plans and hopes were both dashed in one glance. Instead of troops busily digging or standing by in formations ready to march, he saw a disordered mass of milling men moving around the top of the hill or down the reverse slope in groups apparently out of control. He learned later that most of the mob was made up of stragglers or fugitives from units that had moved on forward. The arrival of these men had so disorganized the troops already on the hill that their officers, through incompetence or inexperience, had given up any attempts at rallying and reorganizing their units. What Putnam was seeing has been described by Captain John Chester, who had marched his Connecticut company past Bunker Hill: “There was not a company in any kind of order. They [stragglers, fugitives, skulkers] were scattered, some behind rocks and hay-cocks, and thirty men, perhaps, behind an apple tree . . . frequently twenty men round a wounded man retreating, when not more than three or four could touch him with advantage. Others were retreating, seemingly without any excuse.”

Putnam rode through the chaotic scene down to Charlestown Neck, where he found the roads choked with the same kind of uncontrolled and intermingled companies that Stark had marched through on his way forward. Putnam again tried to show the shirkers, by example, how ineffective the British ships’ fire really was. After riding back and forth across the Neck, he called on men to follow him—all without success.

Frustrated, Putnam raged back to Bunker Hill, where he again tried to rally officers and men so that they could be marched on toward Breed’s Hill. After finding fat Colonel Gerrish lying on the ground with no idea of how to assemble his regiment, Putnam cut loose with tongue and sword: “He entreated them, threatened them, and some of the most cowardly he knocked down with his sword, but all in vain”—all except Gerrish’s adjutant, Christian Febiger, who rallied a group of the more resolute and led them forward. Some more of this kind Putnam directed to the flèches where he thought help was most needed. But those were only a fraction of the mass which continued to skulk on Bunker Hill.

HOWE HAD TO WATCH THE FAILURE OF HIS second attack. The American fire in all parts of the field had been sustained with the same ferocity as before, and the casualty toll had continued to climb alarmingly.

Clinton had arrived during the second British attack and had taken it on himself to rally two regiments that had fallen back toward the beach south of the redoubt. More welcome to Howe, however, were the newly arrived 63rd Regiment and the flank companies of the 2nd Marine Battalion, a reinforcement of 400 men.

Over the protest of some of his senior officers, Howe now doggedly prepared for an all-out assault of the redoubt, with only a token attack against the rail fence. This time Howe, Pigot, and Clinton would lead forward everything else in a bayonet attack on the redoubt. And this time Howe’s field artillery would be relied on to move into a forward position where it could deliver enfilading fire on the breastwork’s defenders, thus eliminating the threat from that quarter. The infantry men were ordered to lay aside all their impedimenta—knapsacks, blanket rolls, everything but muskets, bayonets, and ammunition. The Americans were to be driven from their position, whatever the cost.

Sometime after 4:00 P.M., as Prescott watched the British regroup for a third attack, he saw deployments to his front and both flanks, to the northeast and southwest. It was evident that Breed’s Hill was going to be attacked this time by a giant pincers which would close in from front and flanks.

From behind his rail fence, John Stark watched more light infantry moving forward in an approach march. This time, however, their companies did not mass for a frontal assault, but deployed into a thin skirmish line at a discreet 200 yards. If it did materialize, this attack could be a holding attack meant to keep Stark’s men tied down to their position. As before, however, Stark was seeing more than light infantry to his front. Again, moving obliquely in the distance, were lines of battalion companies headed toward the flèches and the left flank of Prescott’s breastwork. And there was a new threat in the same direction. A British six-pounder battery had been manhandled into a new firing position, where it broke its hour-and-a-half silence by opening fire against Prescott’s breastwork. As the battery opened up, the light infantry advanced another fifty yards and began an ineffective skirmishing fire against the rail fence. Stark knew how to play the game: he directed officers to select a few good marksmen to pick off what British they could at long range.

PRESCOTT AND HIS OFFICERS WERE MAKING SURE that every man was on the firing step and spaced to man all three walls of the redoubt. Then it was time for Prescott to keep his eye on the advancing enemy. They came forward at charge bayonet, and Prescott knew that there would be no halting to fire—this was to be a bayonet assault. He let the front ranks come within a sweat-wringing twenty yards before he gave the command to fire.

As before, the shattered front ranks staggered back. Again Prescott’s men mounted the firing step and fired another volley which brought the British ranks to a halt. But in a matter of seconds everything was changing. The six-pounder battery began firing sheaves of grapeshot, which swept through the rear of the breastwork with devastating effect. The enfilading blasts of grapeshot blew men into flying chunks of flesh, and the screams of the wounded could be heard above the guns. It was more than the Americans could endure; some fled to the rear, others took shelter in the redoubt.

Prescott saw his control slipping away like floodwater rushing through a burst dam. His men were firing their last desperate rounds, and as their ammunition ran out, their fire died away—as someone recalled—”like a candle sputtering out.” Now the British second line had reached the ditch and was fighting its way up the outer wall. While the grenadiers were fighting to scale the walls, Prescott got a frantic message that the British had taken the breastwork. The only recourse now was to order a retreat through the opening in the rear of the redoubt.

Prescott’s last look at the wall revealed British officers, swords in hand, clambering over the parapet. A Marine major stood on the south wall, waving his sword at his men behind him. A last shot from Peter Salem, a black soldier, knocked the major backward from the wall.4 Now British soldiers were dropping into the redoubt from three sides. Prescott and his exhausted men were fighting like devils, with musket butts, rocks, even their hands. Thirty of them died under British bayonets, among them the gallant Major General Joseph Warren of the Continental Congress, who had come to fight as a volunteer. Another of the dead was the already wounded Benjamin Prescott, cut in two by a cannon ball.

The last minutes in the redoubt were like hell itself. The blinding, choking dust that rose from the melee made it difficult to tell friend from foe, and the Americans could scarcely make their way through the rear opening. No shots were fired by the British coming over the wall; the mingled mass of fighting men was too dense for that. Prescott was one of the last through the opening, parrying British bayonet thrusts with his sword. Later, he found that his coat had been pierced in half a dozen places by bayonets.

Once into the open behind the redoubt, the escaping Americans, fleeing toward Bunker Hill, were spared by a stroke of fortune. The British soldiers who dashed around the redoubt to seal off the rear faced each other across a sort of gauntlet; they couldn’t fire for fear of hitting each other. That impasse lasted just long enough for the Americans to flee down the reverse slope of Breed’s Hill. But now fortune deserted them; the British closed ranks and opened fire, causing more casualties among the fugitives than the Americans had suffered in the redoubt. There was nothing that Prescott could do now. Things were too far gone, and he had to make his way alone to Bunker Hill.

STARK PLAYED OUT THE GAME TO THE END. When it was clear that Breed’s Hill and the flèches had fallen, he could see how untenable the rail-fence line had become. If he continued to hold his position, it would soon be outflanked at its right end by a continuation of the present British advance. Reluctantly he gave the order to withdraw, but from then on he made it a dogged fight, dropping back from fence to fence, all the while directing fire to delay the British and to cover—where he could—the Americans falling back from the flèches. Later, even General Burgoyne had to report that Stark’s “retreat was no flight; it was even covered with bravery and military skill.” But this was happening as his men were firing their last rounds of ammunition.

Stark has been criticized for failing to make a counterattack against the exposed British right flank. The censure is unjustified. Stark’s regiments, even companies, had become so intermixed that the control needed to reorganize and maneuver under fire would have been impossible to exercise. To maneuver Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts troops from a defensive posture into counterattacking formations would have been an impossible task. Moreover, there were very few bayonets, no reserves to support a counterattack, and Captain Dearborn tells us that “by this time our ammunition was exhausted. A few men only had a charge left.”

In withdrawing, Stark took with him Captain Trevett’s single remaining fieldpiece, the only gun saved out of the whole battle. There is little doubt that Stark’s fighting retreat saved a large part of the American army on the peninsula.

AS SO OFTEN HAPPENS TO A DEFEATED FORCE trying to escape pursuit, the Americans took their greatest losses between Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill, especially on the slopes of the latter. Putnam had to abandon any hope of rallying fugitives to fight from his half-finished entrenchments. The panicked men continued to pass by him as he sat on his horse like a tiny island in a surging flood. His entreaties and curses were equally unheard. The only fighting units—elements of the regiments of Little and Gardner and some unidentified companies—had already gone forward and were fighting, like Stark and his men, to cover the retreat. When those last men passed Putnam, even he had given up, and so he rode back to find a new position to stop the British. It is said that Prescott and Putnam came face to face near the Neck. Prescott’s first words were to question Putnam, asking why he had not gotten reinforcements to Breed’s Hill. “I could not drive the dogs,” Putnam replied. Prescott snapped back, “If you could not drive them up, you might had led them up.”

While the American rear guards covered the rush of men across the Charlestown Neck, the British halted on the reverse slope of Bunker Hill. General Howe had halted the pursuit, convinced that he lacked enough fresh troops to follow up his costly victory.

In any event, Prescott went on to confront Artemas Ward in Cambridge, where, as the story goes, he demanded permission “to re-take the Heights that night or perish in the attempt, if the Commander-in-Chief would give him three regiments with bayonets and sufficient ammunition.” It is hardly surprising that Ward refused.

Putnam made his way to Winter Hill, northwest of Charlestown Neck, where he did succeed in rallying enough units to work them all night, “and by morning had built an entrenchment... a hundred feet square.” But the Battle of Bunker Hill ended when the British halted on that hill sometime between five and six o’clock in the afternoon.

IT WAS A COSTLY BATTLE. THE TOTAL NUMBER of Americans on the Charlestown peninsula has been estimated at 3,000, but it appears that only half that number were ever actually engaged in combat. American casualties were 140 killed, 271 wounded, and 30 captured, for a total of 441. Thus, if one considers the American force to have numbered 3,000, their combat loss was nearly 15 percent. Conversely, if one considers only the 1,500 Americans actually engaged with the enemy, their combat loss amounted to 30 percent.

By comparison, in cold military terms the losses of the British were grim indeed. Out of Howe’s force of 2,500, the casualties totaled 1,150, or about 45 percent. Officer casualties were particularly high, and the losses within many grenadier and light infantry companies ran as high as a staggering 80 percent. That troops could take such losses and return to the attack says all that is needed about British courage and discipline.

The capability of colonial militiamen to have made such an astounding defense against British regulars has been pointed out again and again in histories—probably deservedly so—but such stout resistance would not have been possible without the leadership shown by (in order of their apparent contribution to the outcome of events) Prescott, Stark, Putnam, and Knowlton. All four had learned the military trade in the hard school of the French and Indian War, and their experience paid off handsomely in their handling of their men at Bunker Hill.

Yet that leadership, as we have seen, could extend no further than any one leader’s battle: Prescott’s at the redoubt, Stark’s at the beach and rail fence, and Putnam’s in his presence everywhere. The phenomenon of three battles in one was due to an inescapable fact—the lack of a higher command structure. Stating such a fact, however, does not mean laying blame on anyone involved in the battle. That no chain of command existed between Ward and Putnam or between Putnam and others was merely a fact of life at the time, a fact that disappeared with the appointment of Washington as commander in chief and the establishment of a Continental army.

When we look back across two centuries and more than two hundred July Fourths, we tend to think of Bunker Hill as the accepted symbol of patriotic fortitude and triumph of our forefathers over their oppressors. It was not so to the people in the colonies, especially in New England. The prevailing public feeling at the time was that the battle was not only a defeat but a military misadventure that should never have been undertaken. Even from a purely military viewpoint it was unnecessary and unjustified. And so Prescott, Stark, Putnam, and company were not exactly hailed as heroes in June 1775.

Soon, however, things began to be seen in a kindlier light, and then came the realization that, “by God, those British regulars were not invincible, and if we had been better organized we’d have licked ‘em fair and square!” This complete turnabout in popular opinion led to the idea that patriotism was all that was required to make militia into freedom fighters who could win the war. The facts have been recognized by two British military historians. Sir John Fortescue, in his History of the British Army, said that “it [Bunker Hill] not only elated the Americans .. . but encouraged them to blind and fatal trust in undisciplined troops, which went near to bring ruin to their cause.” Later, J. F. C. Fuller had this to say in Decisive Battles of the U.S.A.: “It convinced the rebels that a regular military establishment was unnecessary, and so added enormously to Washington’s difficulties.”

Those difficulties will appear and reappear in some of the battle scenes that follow, and it is worthy of note that they were by no means confined to George Washington’s command.

1. Much argument has taken place on the question of Putnam’s responsibilities as a commander on the field in the coming battle. There is nothing to be gained by jumping into such a controversy. The “army” around Boston had as yet neither a command structure nor a staff system, and if Ward had designated Putnam as his field commander, there is no record of it. Because of the army’s loose organization, or lack of it, a Connecticut brigadier general would seem to have had no real authority over, say, Massachusetts or New Hampshire units. But we know enough about Putnam to be sure that he would assume on-the-spot command whenever he thought it necessary.

2. This is an example of the common practice of detaching “flanking companies” to form elite forces with special missions.

3. The battery had been supplied with twelve-pound balls instead of six-pound, so the battery did indeed cease firing after their few six-pound shot had been expended.

4. This was Major Pitcairn, who had led the British Detachment against the Minutemen on Lexington Common.