IF HISTORIANS WERE TO SEEK a redeeming feature in the latter phases of the invasions of Canada, it might be found in the backhanded effect they had on Washington’s operations after he ended the siege of Boston in March 1776. Despite their string of defeats, the American forces in Canada continued to be the magnet that drew British reinforcements down the valley of the Saint Lawrence—reinforcements that otherwise would have gone earlier to General Sir William Howe at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and later would be used at New York. For it was to Nova Scotia that Howe had—through the courtesy of his brother, Admiral Viscount Richard (“Black Dick”) Howe—shipped his army after he evacuated Boston on Saint Patrick’s Day 1776.

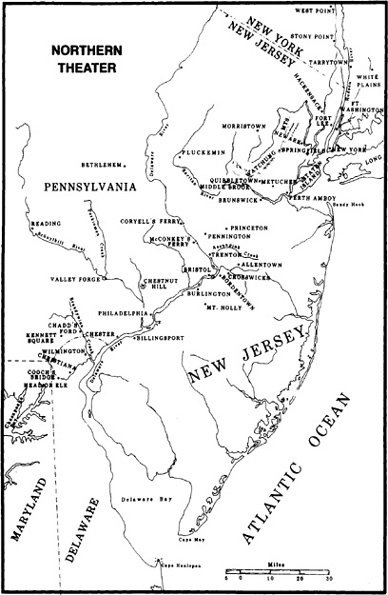

Washington had not hesitated in moving his army from Boston to New York. His recognition of the latter’s strategic significance was clearly expressed in a letter to Brigadier General Alexander, temporarily in command of American forces in the New York area: “For should they [the British] get that Town . . . they can stop the Intercourse between the northern and southern Colonies, upon which depends the Safety of America.” Washington was also keenly aware of two other great advantages that would be Howe’s if he were to take and hold New York City. The British would have a direct link to Canada if they were able to command the Hudson River. More important, they would have the seaport base they needed to launch offensives against the middle colonies to the south or against New England to the north.

In early June 1776 Howe was finally ready to take New York, and a month later he had assembled an army of 25,000 on Staten Island after his brother the admiral had employed 130 warships and transports to move the army from Nova Scotia. Washington could muster a force of 18,000, most of which he had positioned on or near Brooklyn Heights on Long Island.

Howe started crossing from Staten Island to Long Island on 22 August. On the twenty-seventh the Battle of Long Island resulted in such a drubbing for Washington that his army was almost captured and his cause almost lost. Washington and his commanders had performed like ungifted amateurs while Howe had displayed real professionalism, executing a classic turning movement around the American left flank that rolled up their line and annihilated a large part of it.

Washington, however, was not going to give up Manhattan without another fight. He occupied Harlem Heights, and upriver had Fort Washington constructed on the east bank of the Hudson, as well as Fort Lee across from it on the west bank. But his army, now less than 15,000, was being bled white by desertions and expiring enlistments.

In mid-September Howe began a series of chess moves to capture the enemy’s queen, Washington’s army, while checkmating his king, New York City. Howe’s first major move was a strategic envelopment which forced Washington to abandon Harlem Heights and at the same time isolated Fort Washington. At White Plains on 28 October Howe again used his favorite gambit to envelop Washington’s flank, defeating his army but not routing it. Washington withdrew northward to North Castle. Again Howe did not move to exploit success, and again he missed his chance to destroy Washington’s army. Instead, Howe turned southward and on 16 November captured isolated Fort Washington, along with 3,000 prisoners with all their weapons and supplies, a jolting loss to the Americans. Four days later Fort Lee fell to Howe’s forces; this time, however, the garrison escaped, though it had to abandon all the matériel in the fort.

Washington’s so-called retreat across the Jerseys became a retrograde into a series of accumulating crises. By the time Washington’s army had reached the point where the Delaware formed a long nose of Pennsylvania protruding into New Jersey, it could count less than 5,000 half-clad, half-shod effectives to oppose Howe’s 10,000 well-fed, well-equipped British and Hessians, who were poised to take Philadelphia, the colonial capital and largest city. The inhabitants, seeing the danger, had in large numbers shut up shop and fled to the countryside. In New Jersey the Howe brothers, general and admiral, had assumed the role of peacemakers and had issued a proclamation offering pardon to all who would come forward and reaffirm under oath their allegiance to King George. The New Jersey folks jumped at the chance, and in such numbers that Washington was disgusted enough to write: “Instead of turning out to defend the country and offering aid to our Army, they are making their submissions as fast as they can.”

It was these defections and the other accumulating woes that prompted Tom Paine to write that famed pamphlet The Crisis, which began, “These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it Now, deserves the love and thanks of every man and woman.” Paine knew at first hand what he was saying; he had joined up and carried a musket in the retreat to the Delaware. His published pamphlet caught on at once with stouter-hearted Americans, and it was read aloud in towns and villages as well as to groups of soldiers around the camp fires. Its effect was to stiffen the determination of those who would listen.

BY 7 DECEMBER WASHINGTON HAD SUCCEEDED in getting his ever-diminishing army across the Delaware and redeploying it on a dangerously extended front behind the river, extending roughly from Coryell’s Ferry on the north to the ferry near Bordentown, New Jersey, in the center, and from there to the vicinity of Bristol, Pennsylvania. In all there were nine ferries to be guarded by a tiny army of only 4,300 men, but its commander had wisely ordered the seizure or destruction of all the boats to be found along a seventy-five-mile stretch of the Delaware.

Howe’s field commander, General Lord Cornwallis, had pushed his advance guard to the outskirts of Trenton in time for its leaders to see the last of the Americans crossing to the Pennsylvania shore. Nevertheless, Cornwallis’s operations now ground to a halt. On 13 December, a day the English historian Trevelyan said that Americans “might well have marked . . . with a white stone in their calendar,” Howe decided that “the Approach of Winter putting a stop to any further Progress, the Troops will immediately march into Quarters and hold themselves in readiness to assemble on the shortest Notice.” Initially Howe envisaged establishing a line of deployment halfway down New Jersey between Newark and Brunswick. Cornwallis was bolder and recommended manning forward posts at Pennington, Trenton, and Bordentown with a base of operations at Brunswick. Howe concurred and the British occupied those posts. Such a bold and far-flung deployment could be reckless, in view of the danger of exposing the forward posts to isolation and subsequent attack as well as to the cutting of their lines of communication to Brunswick. Yet Howe and Cornwallis obviously felt nothing but contempt for an enemy who, they believed, was not only incapable of mounting a winter offensive but who would, in all probability, not be able to survive the winter as a force to be reckoned with. Come spring, the British commanders could reassemble their forces and lean forward to pluck the apple of Philadelphia from the colonial tree.

Not the least of the anxieties that hung over George Washington at this juncture was the knowledge that by 31 December, only three weeks in the future, expiring enlistments would reduce his army to a mere 1,400 men. Adding to that knowledge was a host of logistical headaches that would have driven a lesser leader to write a letter of resignation: unpaid soldiers without the essential tents, adequate food, clothing, and blankets, let alone the requirements for winter operations.

There is sufficient evidence that Washington had begun to think boldly as early as 14 December, when he confided in three letters that if he received the reinforcements he anticipated,1 he could hope to undertake effective and audacious attacks on one or more of the British forward posts. His anticipations were rewarded; by Christmas, reinforcements brought his army’s strength close to 6,000. He must, he knew, employ that strength before the dreaded date of 31 December.

Additional evidence shows that by 23 December Washington’s concepts had crystallized. Excerpts from his letter to Colonel Joseph Reed on that date make it clear; Washington wrote “to inform you that Christmas day at night, one hour before day, is the time fixed upon for our attempt on Trenton . . . necessity, dire necessity, will, nay must, justify my attack. .. . [in postscript] For if we are successful, which Heaven grant, and the circumstances favour, we may push on.” The last phrase indicated an intention to pursue the offensive in New Jersey, beyond the Delaware.

Finally, on Christmas Eve, a plan discussed at a command conference attended by Generals Greene, Stirling, Roche de Fermoy, St. Clair, and Sullivan gained Washington’s approval. Also present were several colonels, most notably John Glover, who commanded the “amphibious regiment” from Marblehead, Massachusetts, the hardy soldier-sailors who had rescued Washington’s army after the disaster on Long Island.

The main terrain objective was the town of Trenton. The real objective was the destruction or capture of a Hessian force consisting of three regiments in the town, with cavalry and artillery detachments, 1,400 strong, all under the command of the Hessian Colonel Johann Gottlieb Rail.

Washington’s plan called for three separate, coordinated river crossings which, when effected, would result in the two of the three provisional divisions (organized as such solely for the operation) of the army converging on Trenton to seal off the town and capture or destroy its garrison. Looking from south to north, the division on the south—1,900 men and two artillery companies commanded by temporarily appointed Brigadier General John Cadwalader—was to cross the river near Bristol and mount a diversionary attack against the Hessian Colonel von Donop’s garrison at Bordentown. As Donop held the overall command of the Hessian and British forces of about 3,000 men posted at Trenton and Bordentown, it was essential that his attention be diverted from the main attack on Trenton.

The center division under Brigadier General James Ewing—700 Pennsylvania and New Jersey militia—had the mission of crossing at Trenton Ferry to seize the bridge over Assunpink Creek at the south end of Trenton, then taking up position along the south bank of the creek to seal off any enemy attempt at escape in that direction.

The north, and main, attack force was to be commanded by Washington in person. It was to be divided into two columns, commanded by Nathanael Greene and John Sullivan. The force totaled 2,400 men selected from seven brigades of the army, and it would cross the river at McKonkey’s Ferry, nine miles north of Trenton. This main body was heavy in artillery, with eighteen pieces in six batteries under the overall command of Colonel Henry Knox.

Washington’s concept of the offensive further envisaged that after taking Trenton, the three divisions of the army would concentrate near Trenton and, reunited under Washington’s command, resume the offensive against the British at Princeton and—here one can imagine Washington’s eyes turned heavenward—even Brunswick! Such a breathtakingly bold continuation of the offensive would, of course, have to depend upon a successful strike against Trenton.

BY 2:00 P.M. ON CHRISTMAS DAY THE UNITS of Washington’s main division began to form up in their assembly areas in the little valley west of McKonkey’s Ferry. It was a clear, wintry afternoon, with the thermometer hovering around thirty degrees, and a brisk northeast wind was making officers and men clap their hands and stamp their feet to keep them warm. Companies were kept at attention only for the few minutes it took the officers to make sure that each man was carrying his required load of three days’ cooked rations, forty rounds of ammunition, bayonet, and blanket.

By 3:00 P.M. brigades had formed into column and were marching toward their assigned crossing sites, where Colonel Glover and his Marblehead men were readying their Durham boats to take on their loads. Enough of these sturdy craft had been assembled from the Delaware’s shores to transport the columns in shifts. The boats varied in length from forty to sixty feet, with a beam of eight feet, and could carry a crew of four and a load of 30,000 pounds while drawing less than two feet of water. They had strong keels, were pointed at each end, and had removable steering sweeps so that the boats could load, unload, and move either forward or backward. They were also equipped with a mast and sail, as well as footboards along the gunwales where two crewmen on each side could walk while propelling the boat with their push poles. While the Durham boats may have looked awkward to Colonel Glover’s seamen, they were ideal for the task at hand because they could carry full loads of men and even the horses and cannon of the artillery.

By 4:30 P.M. the sun had begun to set, and in minutes it was dark enough for the embarkation to begin. The Pennsylvanians in Stirling’s brigade were making odds that the feel of snow in the air was a sure harbinger of a snowstorm before the night was over. The embarkation began with the advance guard of Stephen’s brigade loading onto the first boats. Behind them artillerymen moved forward the four guns and their horse teams, which were intended to march with the head of both Greene’s and Sullivan’s columns. In all there would be nine artillery pieces with each column. Colonel Henry Knox’s bullhorn bellow could be heard above the wind and the rattling of rolling gun carriages, assuring everyone within a quarter mile of the crossing site that the artillery would have first priority in entering the boats.

The artillery’s high priority was not secured merely through Knox’s powerful voice; it was the result of careful planning based on Knox’s recommendation and Washington’s approval. Jac Weller’s perceptive study of the artillery’s role in the campaign points out that the fact that the

entire crossing of the Delaware was subordinated to the passage of the field artillery to about 2,100 [sic] infantry is an almost unheard of proportion. The usual ratio was two or three pieces per thousand foot-soldiers. . . . [This unusual proportion at Trenton was based on two factors; first,] the artillery was considered to be the wet-weather weapon. .. . It was difficult to load a musket in really wet weather and get it to fire. The gunners, on the other hand, could plug up the vents and muzzles of their pieces and keep the inside of the weapon entirely dry. . . . The second factor [was that]. . . Continental gunners had a high morale throughout their entire organization. . . . Washington and his generals knew this and planned accordingly. (“Guns of Destiny: Field Artillery in the Trenton-Princeton Campaign”)

With the artillery in place in the boats, Greene’s column loaded and shoved off in sections. Stephen’s brigade led. The second section was composed of Mercer’s brigade. Next came Stirling’s brigade, which was to constitute the reserve in Greene’s column. Although the almanac called for a full moon, it was fully obscured by a heavy cloud layer, leaving the whole crossing to be carried out in complete darkness.2

A historical weather study by David M. Ludlum assures one that “there was no lack of ice of some kind: solid shore ice, floating cakes in midstream, and a glaze tending to form on the most exposed surfaces of boats and objects along the river” (“The Weather of Independence: Trenton and Princeton”). Nor was floating ice the end of the troubles besetting the crewmen and the soldiers in the boats. To make things worse, the storm soon turned from snow to sleet and hail driven by a bitterly cold wind. The storm brought equal misery to all ranks from general to private. Captain Thomas Rodney recalled in this diary that “it was as severe a night as ever I saw .. . [a] storm of wind, hail, rain, and snow.” These miserable conditions were to last intermittently throughout the night and the following day. As a probable consolation to Washington and his commanders, it justified the commander in chief’s foresight in relying on the artillery to provide wet-weather fire support.

Washington’s plan called for his entire command to cross by midnight, thus allowing for a five-hour night march to reach Trenton and deploy into battle formation before first light. But the storm and river conditions had ripped that timetable to soggy pieces. It was after 3:00 A.M. when the last soldiers were landed on the New Jersey shore, and another hour before Greene’s and Sullivan’s columns were formed in marching order and started on the road toward Trenton. Only then was Washington finally able to leave the riverside and join Greene. The diary of an officer on Washington’s staff gives us this glimpse of his commander overseeing the last of the troop landings: “He stands on the bank of the stream, wrapped in his cloak, superintending the landing of his troops. He is calm and collected, but very determined. The storm is [again] changing to sleet and cuts like a knife.”

Washington’s calmness and determination were obviously on the face that he showed to his officers and soldiers. What was not revealed to them will never be known, but certainly part of his secret self was bearing the strain of knowing that he must attack Trenton in broad daylight, with the probable loss of the surprise he had so counted on in his plan for a night attack. Add to that stress the awareness that he had received no word from either Ewing or Cadwalader, both of whom should have crossed the river before Washington’s force, and one begins to appreciate Washington’s moral courage in maintaining such composure.

On the nine-mile march to Trenton the mental stress being borne by the commander in chief was matched by the physical misery of the men, who continued to be battered by the shifting blasts of snow, sleet, and freezing rain. Their only meager compensation was that the northeast wind was bringing the storm’s effects against their backs instead of their faces. The rutted road made treacherous footing for the men without shoes. Most of that wretched lot had bound their feet with rags, and it was these unfortunates who were leaving the bloody tracks in the snow that have been mentioned so often in schoolbooks.

Washington halted the column at the hamlet of Birmingham, where the road forked into two roads to Trenton. He let the troops fall out just long enough for a breakfast of hard rations. When the officers gave the word to fall in again, sergeants were kept busy rousing men from the roadside where they had fallen asleep over their cold meal.

The force now split into the two designated columns. Greene’s men took the left-hand fork, the Pennington Road, which led into Trenton at its north end. The column was made up of the brigades of Stephen, Mercer, Stirling, Roche de Fermoy, the Philadelphia troop of light horse, and the nine artillery pieces in the batteries of Captains Forrest, Hamilton, and Bauman. Washington rode with Greene in the northern column.

The other column, under Major General Sullivan, took the right-hand fork, following the River Road to come into Trenton from the south, in order to cut that end of the town off from the river. Sullivan’s force was composed of the brigades of St. Clair, Glover, and Sargent.

The two roads were nearly equal in length, between four and five miles long. Washington, looking across the snow-covered fields, watched the van of Sullivan’s column trudging off in the distance. From now on, the chances for a coordinated attack would have to depend on unfolding events as the two columns closed in on the Hessian outposts around the town. His commanders knew the Hessians’ locations, but how well manned were the enemy positions? And how alert?

COLONEL JOHANN GOTTLIEB RALL COMMANDED the three infantry regiments that made up the Trenton garrison: his own regiment plus those of Knyphausen and von Lossberg. There was also a detachment of jägers—infantry armed with short, heavy rifles—a company of artillery with six three-pounder brass fieldpieces, and twenty British dragoons, in all about 1,400 men. Rail had been given the honor of commanding the forward detachment of von Donop’s sector, which stretched from Trenton to Burlington.

Johann Rail was a stiff professional with an undisguised contempt for the American rebels. He had received the surrender of the garrison of Fort Washington hardly six weeks before this Christmas Day, watching the Americans marching without arms between the two Hessian lines of the Regiments Rail and Lossberg. He spoke no English and had no intention of learning the language. He was a hard drinker and a hard charger in battle, and that was as far as his talents went. He had no interest in fortifying his garrison—”if the Americans come we’ll give them the bayonet”—and seldom bothered to visit outposts. Instead, he inspected companies in ranks, and his chief joy was to listen to the band play as it marched around the house of Abraham Hunt, where Rail had set up headquarters. The cannon were paraded with the band, as Lieutenant Andreas Wiederhold recorded, “instead of being out at the head of the streets where they could be of use.” It would seem that the attitude and personality of Johann Rail were among the good breaks that came Washington’s way at Trenton.

In keeping with Rail’s personal style of celebrating Christmas, his troops (with the exception of his own regiment, which had “the duty” for Christmas Day) were allowed to relax—to drink and sing hearty German songs while gathered around the Tannenbaum they had cut and trimmed for the occasion. Only one incident had almost marred the celebration. While playing cards with a Tory merchant, Rail had heard firing about 7:00 P.M. on the north side of town. He marched several companies of Regiment Rail to the roads at the head of the town, where he was informed that some thirty or so rebels had shot up an outguard, wounding six of the Regiment Lossberg.3 The rebels had vanished, and Rail’s patrols, having gone two miles, returned without seeing a rebel. At this time Major von Dechow urged Rail to send out another series of patrols as far as the ferry landings, but Rail felt no need of such precautions and ordered the troops to stand down. All returned to their quarters while Rail went on to Abraham Hunt’s, where he joined the party playing cards and guzzling Christmas cheer. By 10:00 P.M. Rail had dismissed his adjutant, Lieutenant Jacob Piel, with no further orders for the night. This standing down seems to have created a détente which gave the Hessian commander and his men all the more reason to relax and enjoy themselves.

One other incident—seemingly trivial—also failed to alert Rail to impending danger. A Tory farmer from Bucks County knocked at the Hunt house door, telling the servant he had an urgent message for Colonel Rail. The servant told the farmer that the colonel was busy and would see no visitors. The Tory wrote out a note and asked that it be given to Rail at once. The man, his duty done, disappeared into the night. The scribbled message told Rail that the whole American army had crossed the river and was marching on Trenton. Rail didn’t bother to read it; he slipped it in his pocket and picked up his cards to go on with his game.

Lieutenant Andreas Wiederhold was no admirer of Colonel Rail’s, so it was small wonder that he didn’t share his commander’s complacency. He had strengthened his oupost at the Richard Howell house on the Pennington Road north of Trenton, bringing up nine more men on Christmas night. At about 7:45 A.M. of the twenty-sixth Wiederhold decided to stretch his legs and take a look outside. What he saw pulled him up short. Two hundred yards away, about sixty men were coming at the house on the double. Already his sentinels were running toward the house—to their command post—shouting: “Der Feind! Heraus! Heraus!” (The enemy! Turn out! Turn out!).

What Wiederhold was seeing was a part of Stephen’s brigade, the advance guard for Greene’s division, which had orders to advance with all speed into the town, overrunning any outguards in the way. At the same time the regiments of Mercer’s brigade were swinging around to the south in order to support Stephen’s attack by outflanking any resistance they met.

The American tactics were working as planned. Wiederhold’s guard got off a volley before it had to fall back across the fields to its left rear, toward King Street. Realizing that he was in danger of being cut off by Mercer’s men, Wiederhold led a rush rearward to fall back on Captain von Alterbockum’s company, which was forming up to block the Pennington Road. Hardly had Wiederhold’s panting men lined up on the captain’s left flank, however, when Alterbockum realized that a delaying action was out of the question and ordered a withdrawal, the Americans hard on his heels, firing as they came. When Alterbockum’s company reached the north end of the town, he had it fall back down King Street, while Wiederhold’s men, joined by Captain Bruback and a guard detachment of the Regiment Rail, split away to retire down Queen Street, taking advantage of the cover between houses as they withdrew.

In the south, Sullivan had sensibly held up his advance guard long enough to ensure that Greene’s division had time enough to drive in the enemy’s outposts in the north. Then Sullivan’s advance guard struck out against the Hessian outguard occupying the Hermitage, the home of Philemon Dickinson on the River Road. Like Lieutenant Wiederhold, Lieutenant von Grothausen saw that he must take action at once. He took a sergeant and twelve of his detachment of fifty jägers and started off on the double toward the firing on the Pennington Road. Grothausen had gone hardly three hundred yards when he looked over his left shoulder to see a column of Americans heading toward the Hermitage. It was too late to get back to the rest of his jägers at the house, so Grothausen doubled back toward the river at the south end of town, joined en route by a corporal and the rest of the jäger detachment, which had left everything but their muskets and cross belts at the Hermitage. Grothausen tried to make a stand near the old barracks, but after one futile volley the jägers had to run for their lives or face capture. Some succeeded in fording Assunpink Creek south of King Street, while the bulk of the fleeing light infantry escaped across the Queen Street Bridge, which the Americans had not yet reached.

Lieutenant Jacob Piel, Rail’s adjutant, was the first officer in the town to hear the firing on the Pennington Road. He ran from his quarters, next door to Rail’s headquarters, turned out the guard there, and started them up King Street to reinforce the outposts. That done, he beat on the front door of Rail’s house until the colonel stuck his night-capped and no doubt hung-over head out of an upper window.

“What is the matter?” Rail called down.

“Haven’t you heard the firing?” Piel shouted back.

“I will be out in a minute,” and Rail was as good as his word. When he stepped out of the house, American musketry and artillery had already begun rattling down King Street. Rail mounted his horse and ordered his own regiment to form up near the lower end of King Street. When Lieutenant Colonel Scheffer asked, by messenger, when to deploy the Regiment Lossberg, Rail ordered it to parade in the graveyard behind the English Church and prepare to advance up Queen Street. He then directed the Regiment Knyphausen to stand by as a reserve on Second Street, east of King Street.

THE INITIAL PHASE OF WASHINGTON’S ENCIRCLING attack on Trenton had been carried out without a hitch, no mean accomplishment for a coordinated eighteenth-century operation. The outposts had been driven in, and there were Americans in position on three sides of the town.

While the Hessian regiments were being rousted out, the next phase of Washington’s battle plan got under way. Two brigades of Greene’s division took off to their left, bypassing the upper end of town to deploy between the Princeton Road with their left flank extended toward Assunpink Creek, thus cutting off any Hessian attempt to break out of Trenton to the northeast. At the same time his third brigade was turning to the south, extending its right flank to link up with the left brigade of Sullivan’s division to complete the encirclement of the town.

The resulting gap between Stephen and Mercer was quickly filled by Stirling’s brigade and its artillery, which was moving straight ahead around its objective, the juncture of King and Queen streets at the upper end of town. Henry Knox came into his own, leading forward his artillery into firing positions at the head of the two streets. Captain Forrest’s battery of two six-pounder guns and two howitzers had been marching near the head of Greene’s column and thus was practically on the edge of its designated firing position at the head of Queen Street. Captain Alexander Hamilton’s battery of two six-pounder guns had unlimbered about 200 yards north of town, and in no time its battery commander was urging his cannoneers forward with drag ropes to come into position and open fire down King Street. After Henry Knox had called off the range, the ruddy-faced Hamilton could be heard shouting his fire commands, and the first ranging rounds boomed out.

Not far away, Washington, trailed by his staff and an escort of Philadelphia Light Horse, took up his position on the higher ground where he could observe the movements of his troops and the enemy. Visibility, however, was not yet good enough for the commander in chief to see the far end of town and the bridge over the Assunpink. Hence he could see nothing of Sullivan’s actions and would still be anxiously trying to determine whether Ewing had crossed the river and taken the bridge. Closer in, though, he could see Mercer’s men beginning to break into houses on King Street or slip between them to find places to get a shot at the Hessians.

When Hamilton’s and Forrest’s guns opened fire, the Hessian commander directed his regiment, supported by companies of the Regiment Lossberg, to advance up King Street and clear it. Led by Lieutenant Colonel Brethauer, the Hessian ranks marched behind the colors of Regiment Rail, snatched from the colonel’s quarters just in time to join the formation. No sooner had the Hessians stepped off, however, when the round-shot from Hamilton’s battery tore through their ranks. At the same time Mercer’s men, firing from the cover of houses and fences, took their toll on the enemy’s left. The Hessians halted and got off two volleys. As Brethauer gave the command to fire, his horse was shot and sent him tumbling. The combined fires of American artillery and musketry were too much. The battalions of Regiment Rail broke, and the flood of fleeing men tore through the supporting Lossbergs’ ranks, breaking up their formation.

The two Hessian three-pounder guns coming to the support of their infantry on King Street were just as roughly handled. When Rail had ordered his regiment forward he had called out to Lieutenant Engelhardt, who was standing by his two guns in front of the house where the guard reserve had been quartered: “My God, Lieutenant. . . . Push your cannon ahead!”

Since the guns were already hitched to their horse teams, Engelhardt took off up the street at the head of his little battery. They had hardly gone fifty yards when the shot from Hamilton’s guns smashed into them. Engelhardt made a gallant effort to get into firing position and return the fire. He did get off six rounds from each gun, but at a devastating cost. In a matter of minutes he had lost half of his men, and five horses were down with fatal wounds. The artillerymen left standing dropped their rammer staffs and cartridge bags and ran for cover behind the houses.

Henry Knox, at the head of King Street on Princeton Road, saw the Hessian guns being knocked out of action. He ran over to Colonel George Weedon, whose Virginia regiment of Stirling’s brigade had deployed along the road ready to attack into the town.

“Can some of your men take those guns?” Knox asked. Without replying, Weedon ordered Captain William Washington forward. Washington took off on a run, followed by Lieutenant James Monroe, Sergeant Joseph White, and a half-dozen men. Keeping close to the houses and running for all they were worth, they swarmed over the guns and tried to turn them on the Hessians down the street. In that brief flurry of action both officers were wounded—Washington in both hands and Monroe in the shoulder. The capture of the cannon was followed at once by Weedon’s men charging down King Street.

Over at the head of Queen Street, Forrest’s battery was sweeping the street with deadly effect. One of his two howitzers went out of action with a broken axle, but the other three cannon did their share in breaking up Hessian attempts to advance, as well as silencing two more Hessian guns after they had fired only four times.

While those Hessian guns were being silenced, Stirling’s men were attacking southward down both Queen and King streets. Meanwhile, what was happening to Sullivan’s column in its attack from the River Road into the south end of the town?

After the advance elements of St. Clair’s brigade had driven the Hessian jägers from the Hermitage and the old barracks, most of the jägers had fled across Assunpink Creek. Following Captain John Flahaven’s New Jersey Continentals came Colonel John Stark, of Bunker Hill fame, with his regiment of New Hampshiremen. Stark, being Stark, didn’t wait for the niceties of orders and deployments. He led a thundering charge from the right—formerly the head—of St. Clair’s brigade straight ahead toward the Regiment Knyphausen, which was now deployed facing south, and Major Dechow’s battalion of the Lossbergs. In Major Wilkingon’s account, “the dauntless Stark dealt death wherever he found resistance, and broke down all opposition before him.”

Not to be outdone, Sullivan personally led a column of Sargent’s and Glover’s men past the old barracks, then double-quicked up Front Street toward Queen Street, intending to cut off any Hessian attempt at escape over the Assunpink bridge. In this he was not completely successful, since most of the jägers and a good many fugitives from Regiment Rail had already gotten away via the bridge, preceded by a detachment of twenty British dragoons who had not waited to hear more than the opening shots of the battle before decamping.

IN FOLLOWING THE AMERICAN FORCES IN THEIR movements and actions, as well as the Hessian attempts to defend and counterattack, one should not lose sight of two major factors that determined the character of the battle from start to finish: the continuing storm, and the transformation from a coordinated American attack to a “soldier’s battle.” Ludlum’s “The Weather of Independence” concludes that the storms most prevalent at this time of winter were “bringing first snow, then ice pellets [sleet], and finally rain, often with alternate periods of each, or a mixture of all three.” From other records it can be ascertained that those “alternate periods of each” made conditions miserable for both sides throughout the battle. From the Americans’ viewpoint, even though the Continentals and militia had taken the precaution to cover their flintlock muskets with rags and to keep them under blankets or coats on the march, there was no way of protecting the firing pans, flints, and touchholes once the musket had to be exposed for firing. Consequently, no sooner did an infantryman go into action than this weapon was rendered useless except for the bayonet. The Hessians did have dry flintlocks when they charged out of the buildings in which they were quartered, but after firing a round or two they fell victim to the same weather that plagued their enemies. Christopher Ward has summed it all up: “The flints would not strike a spark; the priming charges would not flash; the touchholes were clogged with wet powder. . . . Those that got into the houses dried their gunlocks and could fire toward the end of the battle” (The War of the Revolution).

It was artillery, which could keep its necessaries dry enough to continue functioning, that ruled the battle of the main streets. What went on around the houses, in the alleys and side streets, and behind fences and walls was another matter. Once Greene’s and Sullivan’s battalions were committed to action inside the town, the situation resembled the pouring of water into a cauldron of molten lead. The resultant eruptions became battles of single men or small groups, moving and firing when they could at whatever enemy they encountered. Over it all, the sleet beat down through the pall of smoke that continued to hang over the town. It was an affair, then, of bayonet and sword. Adding to the confusion of weather and smoke was the noise of battle: the booming of the cannon, the shouts of men charging with the bayonet, and the commands of officers who had to shout their loudest to be heard. It was this last factor, the regaining of control by the leaders, that eventually brought order out of chaos.

On the Hessian side, Rail’s officers had managed a rally toward the south end of the town, along the River Road at Front Street. They pleaded with their commander to renew the attack. Rail was in a daze, seemingly unable to make a decision. Major von Hanstein made a final plea to the brigade commander: “If you will not let us press forward up this street [Queen Street], then we must retreat to the bridge; otherwise the whole affair will end disastrously.” Rail then agreed to a renewed counterattack. The two regiments, Rail and Lossberg, were brought into line facing northward toward King and Queen streets, the lines were dressed, and the colors brought to the front of the color companies.

“Forward march!” Rail commanded, “and attack them with the bayonet.” The two regiments, Rail on the left, Lossberg on the right, marched forward under the direct command of Lieutenant Colonel Scheffer. As they moved out, the band joined them, striking up a martial air. Then, with colors drooping in the freezing rain and band playing, Scheffer guided the formation into Queen Street.

There the brave show came to a quick and bloody end. In a matter of minutes the Americans, firing from the houses and alleys, found ready targets in the packed ranks of Hessians, who were further exposed to the blazing guns of Forrest’s battery firing down Queen Street. The demoralized Germans floundered about in spite of their officers’ attempts to restore ordered formations. Then more Americans, needing no urging from their officers, came pushing in through the alleys from King Street, striking the enemy mass on its left flank.

Rail’s adjutant, the loyal and ever-present Lieutenant Piel, tried to convince his commander that there was still a chance to withdraw through the escape route over the Assunpink bridge. Rail agreed, and ordered Piel to reconnoiter and make sure the route was open. Piel made it as far as the corner of Queen and Second streets, from where he found that the Americans were in control of the bridge. He turned back to Rail, to find the colonel shouting to his milling soldiers, “Alles was meine Grenadiere sind, vorwärts!” (All who are my grenadiers, forward!).

It was too late. Captain Joseph Moulder’s battery of three four-pounders, attached to Sullivan’s division, began to blast into Queen Street from a hastily occupied position near Second Street. The Americans were closing in from Rail’s left and rear, and there was no longer a chance to withdraw southward. Rail gave the order to move eastward to reassemble in the apple orchard at the southeast corner of town. No sooner had he given the order than he was struck by two bullets in his side. He fell from his horse and was helped by two soldiers to the Methodist Church on Queen Street.

When the three remaining field officers finally got the remnants of the two regiments through the side streets to the orchard, they held a hasty council. It was agreed to make a breakout attempt from the orchard toward the Brunswick Road. But when they tried to execute their plan, they found the way blocked by Stephen’s and Fermoy’s brigades of Greene’s division, supported by Forrest’s and Bauman’s batteries. The Hessian field officers thereupon surrendered to General Stirling.

In the meantime, Sullivan’s division was dealing out the same kind of bashing to the Regiment Knyphausen and its attached battalion of Lossbergs. The brigades of St. Clair and Sargent surrounded a fleeing mob of fugitives from the three Hessian regiments that were trying to reach the Assunpink bridge and captured the lot. The Regiment Knyphausen tried to counterattack but was driven back. Major Dechow, commanding the last of the Lossbergs, was severely wounded and had to surrender. The beaten Germans tried to retreat to the bridge but found it held in strength by the Americans; then they turned away to try to cross the creek by a ford, but they found none that was passable. They then turned to follow the creek eastward; some did get across, only to find themselves looking into the muskets of St. Clair’s men on the far side. In the end, the Regiment Knyphausen, complete with screaming camp followers, colors, and field music, was surrendered to General St. Clair. It was nearly nine o’clock. The Battle of Trenton was over.

IN SPITE OF THE ESCAPE OF SOME 400 or 500 of the enemy during the battle, Washington’s bag of men and matériel was truly impressive: over 900 men and officers, all their muskets and accoutrements, their six pieces of artillery complete, ammunition and supply wagons, fifteen sets of colors, and all the instruments of the band that had played so bravely up to the end. The American losses: one officer and one private!

Yet even these totals, much as they meant to the quartermasters, were insignificant compared to the moral effects on the British and American causes. Howe was so shocked by the news—imagine these costly European professionals not only beaten but captured by a ragtag army that had been struggling to stay alive—that he sent posthaste for Cornwallis, who was about to board ship for England. The earl must return at once to resume command in New Jersey. In the same breath, Howe ordered reinforcements forward toward the stricken area. It would seem that this General Washington, who had been earlier dubbed “the Fox” by Cornwallis, did have a fearsome bite!

The news of Trenton was greeted with elation throughout the colonies. Washington emerged from the depths of crisis to the stature of hero. The man who had taken such a series of drubbings, from Long Island to Forts Lee and Washington, was restored to popular favor, all his defeats set aside. On 27 December Congress, still safely ensconced in Baltimore, resolved to give Washington dictatorial powers for the next six months: to raise all kinds of troops, to appoint all officers up to brigadier general, to take “whatever he may want for the use of the army.”

THE VICTORIOUS GENERAL HIMSELF WAS FEELING anything but heroic there in Trenton in mid-morning of his day of triumph. It was obvious that neither Ewing nor Cadwalader had crossed the river, let alone accomplished their missions. Washington learned later that Ewing had flatly turned back from a river crossing, judging the conditions impossible for such a venture. Cadwalader had at least tried by crossing more than 600 men at Dunk’s Ferry, but he withdrew them when he thought it impossible to get his artillery across the river. Thus Washington was left with his worn-out men and his bag of prisoners and matériel to fend for himself.

At a conference of senior officers, Washington soon realized that the original plan to drive on to Princeton and New Brunswick was out of the question. Without Ewing’s and Cadwalader’s aggregate force of 2,600, and with only his exhausted 2,400, Washington was not only unable to pursue the offensive, but his present position would soon be untenable in view of approaching British reinforcements and the problem of trying to fight them with his back to the river. It was clear that the only course of action left was to recross the river and reorganize his forces around their cantonments on the Pennsylvania side. Washington summed it up in a letter to General Heath on 27 December: “I thought it most prudent to return the same evening [26 December], with my prisoners and the artillery we had taken.”

Shortly after noon the dreary march began back to the boats at McKonkey’s Ferry. The winter storm continued to beat upon the cold and weary men with the same snow and sleet that they had endured in the early morning hours. The river crossing was even harder than the first time; it was so cold that three men froze to death in the boats. It was dark before the last boats had landed their men in Pennsylvania, and most of the units didn’t make it back to their camps until the next morning, falling asleep as soon as they reached their huts. They had marched, most of them, as far as fifty miles and had fought a brutal action. The morning reports of 27 December showed over a thousand men unfit for duty—over 40 percent ineffectives. And those worn-out men would have been anything but comfortable had they known what their commander in chief was planning for their immediate future.

For the next two days, after recrossing the Delaware on 26 December, it was business as usual for Washington: “business as usual” meaning that every bit of good news—e.g., the reception of the news of his Trenton coup—would be evened by a jolt of bad. He knew all too well that the effectives in his army numbered only about 1,500, and that the enlistments of most of his Continentals would expire on 31 December.

Washington met those challenges with typical Washingtonian courage. He offered a bounty of $10 to every man who would extend for six weeks, thereby pledging the public credit, with no authority other than his own word, since his military treasury was completely defunct. A hurried letter begged Robert Morris, the financier of the revolution in Philadelphia: “If it be possible to give us assistance do it; borrow money when it can be done. ... No time, my dear sir, is to be lost.” Morris raised $50,000 in paper money, which he sent, and on the morning of 1 January 1777 canvas bags from Morris arrived containing all the hard money he could scrape up: “410 Spanish milled dollars ... 2 English crowns, 72 French crowns, 1,072 English shillings.”

Making separate and largely successful pleas to the Continentals, Washington, Knox, and Mifflin succeeded in getting all but the most feeble and sick to stay on. Things began to look up enough for Washington to start his army back across the river, and by 30 December he had reassembled it in Trenton, where he awaited the expected reinforcements. General Mifflin had miraculously raised nearly 1,600 men in and around Philadelphia, and these troops were now moving on Trenton via Bordentown. In addition, Cadwalader’s militia were marching from Allentown and Crosswicks. When these reinforcements were concentrated at Trenton, Washington would have 5,000 men he could count on for the resumption of his offensive in New Jersey. The commander in chief had never abandoned his concept of taking Princeton as the big step toward the capture of the British base at Brunswick.

The background picture, however, was not all rosy. Of the 5,000 troops that Washington was concentrating in Trenton, a great part of the militia was made up of untrained farmers and villagers who had no knowledge of combat. They must have been in good physical shape and even well clothed for winter, but that was the only bright aspect. On the other hand, the Continentals, while battle-hardened and dependable, had been labeled a “flock of animated scarecrows.” Against this brittle instrument of Washington’s, Cornwallis was already moving southward a force of 8,000 professionals—well fed, completely equipped, disciplined, and combat ready.

Washington’s combat intelligence, reliable as usual, had made him aware of Cornwallis’s movements across New Jersey, and his chief concern became the security of his forces concentrating at Trenton. It was evident that Cornwallis had as his main objective the American army in Trenton. On New Year’s Day 1777 the earl was preparing to advance with a force of nearly 7,000, with twenty-eight pieces of artillery, under his personal command. As a rear guard he left the 4th Brigade under Lieutenant Colonel Mawhood at Princeton; it was a force of about 1,200, composed of three infantry regiments: the 17th, 40th, and 55th. The main baggage train was to return to Brunswick.

To counter this formidable array, Washington on New Year’s Day dispatched a covering force under the French General Roche de Fermoy made up of Fermoy’s own brigade, Colonel Hand’s Pennsylvania riflemen, Colonel Hausegger’s German Regiment, Colonel Scott’s Virginia Continentals, and the two-gun battery of Captain Forrest. Fermoy’s mission was to execute a delaying action as the British moved southward toward Trenton, beginning with an initial position at Five-Mile Run, a little over a mile south of Maidenhead (now Lawrenceville). He was to delay on successive positions, causing the British to deploy as often as possible and thereby disclosing the strength of Cornwallis’s main body.

This covering force, and the American army in general, got an unexpected break in the weather beginning on New Year’s Eve. Southerly winds brought on a temporary thaw that melted the snow and softened the ground. When Cornwallis’s men began their march on 2 January, the hard-frozen roads were turned into quagmires. The British artillery, despite the cracking of the drivers’ whips over the horses and the pushing and shoving of the gun crews, became bogged down time after time. Realizing the difficulties, Cornwallis had his force move in three columns. He also detached General Leslie’s 2nd Brigade of about 1,500 men at Maidenhead, while he pushed ahead with the remaining 5,500 men.

At about 10:00 A.M. the British advance guard elements encountered the American outposts north of Five-Mile Run. At this point General de Fermoy saw fit to return to Trenton “in a questionable manner”—whether he was drunk or just befuddled is not certain. With his departure the covering force got a good break in the form of Colonel Edward Hand of the Pennsylvania riflemen. This Irish-born, thirty-two-year-old former British soldier, who had resigned an ensign’s commission in 1772 to try his hand at medicine, was the stuff of which natural leaders are made. Under his masterly control the Pennsylvania rifles took their deadly toll of British infantrymen long before the British Brown Bess could open fire. Hand also saw to it that the muskets of his other units came into play as the British deployed.

Fighting from all kinds of cover, the Americans forced the British to deploy again and again before scampering away through woods or across fields. After having to fall back from Five-Mile Run, Hand took up his next position along Shabbakonk Creek, where the initial skirmishing turned into an all-out brawl. The fire of Hand’s men caused so many casualties that the British mistook the skirmish line for the American main battle position. After they had destroyed the bridge across the creek, the Americans continued to lay down such a fire that the British artillery blasted the tree lines for half an hour while two Hessian battalions waited in deployed order to assault the creek’s defenders. When the British finally advanced, Hand’s force had melted away unseen to take up a new position behind a ravine known as Stockton’s Hollow, about a half mile north of Trenton. There the Americans, with the continuing support of Forrest’s guns, forced the British to deploy units once more, under cover of a new artillery cannonade. When the enemy’s fire and impending attack became too much of a threat to his position, Hand reluctantly withdrew into Trenton. By now it was 4:00 P.M., and he had carried out superbly the mission of the covering force, but he was not finished by any means. Firing from behind and within the same houses from which they had battled Rail’s Hessians just a week before, Hand’s men continued to hold back the British advance guard of 1,500 men. Finally the covering force units were safely withdrawn across Assunpink Creek, where American batteries on the south side took the British under fire and stopped them in their tracks. Washington was indeed indebted to Edward Hand for buying the time he so badly needed to organize his incoming reinforcements and deploy them in their defensive positions behind Assunpink Creek. The commander in chief’s debt was repaid, at least in part, when Congress acted on his recommendation and made Hand a brigadier general some two months later.

While Hand was holding up the British advance, Washington and his generals had made good use of the hard-bought time to occupy a defensive line on the ridge just south of the Assunpink. Entrenchments were well under way after the brigades took up their positions: Mercer’s on the left, Cadwalader’s in the center, and St. Clair’s on the right. Behind this front line was another line forming a reserve.

Hand’s men had done their work so well that it was not until sunset (close on 5:00 P.M.) that the renewed British advance struck at the Assunpink Creek bridge while Hessian units tried to cross at a ford. The overall British attack could be described as halfhearted at best. It became almost an affair of artillery, from the American standpoint, as the batteries laid down such a heavy fire that the enemy was easily repulsed. Musketry followed, as well as the British artillery return fire. The affair, sometimes called the Second Battle of Trenton, hardly seems worthy of such a title, though there were casualties on both sides.

DARKNESS HAD SET IN BY THE TIME Cornwallis arrived in Trenton with his main body. Since the advance guard had already collided with the American main battle position, Cornwallis took counsel with his staff in regard to a night attack. His quartermaster general, Sir William Erskine, called for an immediate strike, concluding with, “If Washington is the general I take him to be, his army will not be found there in the morning.” General Grant disagreed—the rebels were securely dug in, there were no boats for an assault, and the British troops were exhausted after their long, difficult march. An early-morning attack could turn the rebel right flank with their backs to the Delaware. Other officers offered many of the same points. Cornwallis himself was dubious about trying to find and turn the American right flank in the dark, while the alternate course of action, a frontal attack against an entrenched enemy, seemed equally risky. In the end Cornwallis decided that he already had Washington in a trap that could easily be sprung in tomorrow’s daylight, and so closed the council of war with: “We’ve got the old fox safe now. We’ll go over and bag him in the morning.”

Withdrawing to the north side of Trenton, the British set up camp for the night. Their sentinels and patrols took note of the numerous and unusually bright camp fires along the rebel lines on the ridge beyond the Assunpink, and anyone who came within a hundred yards or so of rebel outposts could hear the clinking of entrenching tools as the rebels continued to dig in.

As darkness wore on, the men who were awake in both British and American lines began to feel the wind swinging in from the northwest, bringing the temperatures down to the freezing point. Before midnight the mercury began a steady decline, until by daylight (sunrise was at 7:23 A.M. on 3 January) the cold could be measured in the low twenties.

Peering through the morning mists that were beginning to dissipate after first light, British sentries and patrols could see the American lines. Not a rebel was to be seen. When the senior commanders were alerted and had gathered around Cornwallis, their field glasses confirmed the reports of the patrols. Cornwallis’s fox had made his getaway, stealthily slipping out of that cul-de-sac. Just how, in the name of all that was unholy, had he managed it? And where had he gone?

In the early evening of 2 January Washington had summoned his own council of war and had decided to have the army slip away that night. They would pass around Cornwallis’s left flank, bypass the British force at Maidenhead, strike the British rear guard at Princeton, and—if all went well—push on to capture the enemy’s baggage, stores, and treasure at Brunswick.

While the details of the plan were being worked out, Washington was taking note of a second fortunate break in the weather. The southerly winds and warm rains that had hindered Cornwallis’s advance were being succeeded by northwesterly winds and falling temperatures that would assure the freezing of the ground’s surface. His army and its cannon could march with confidence on its objectives.

A sketch map showing the disposition of British forces in Princeton, as well as the road network in and around the town, had been passed to Colonel Cadwalader by an American spy. Now it served to strengthen Washington’s plans, especially through the potential use of a route along the back (eastern) and more vulnerable side of the town.

Advice as to routes out of the Assunpink positions was essential to the American success. Local farmers were summoned, and guides were selected from them. All ranks were alerted to the necessity to form ranks and march quietly. The wheels of the cannon carriages were wrapped in rags and ropes, which would further serve to give traction for moving the guns over frozen roads. The baggage train of 150 wagons, accompanied by three heavy guns which couldn’t keep up with tactical marches, were marched quietly away, bound for Burlington. By midnight the last preparations had been completed.

Once the plans had been approved, they were put into execution. A party of 400 men was detailed to carry out the simulation of an army warmed by its camp fires and putting out work details on its entrenchments. Some of the party gathered fence rails to keep the campfires burning brightly, while others banged away with pick and spade to simulate continued digging in. Some also made noises like clumsy patrols near the bridge and along the creek. Their work would cease just before daylight, when they too would slip away and follow the army’s march.

At 1:00 A.M. on 3 January the eastward march began, with no one under the grade of brigadier general knowing where the army was headed or what it was supposed to do when it got there. Light infantry, backed up by the Red Feather Company of Philadelphia, made up the van, followed by Mercer’s brigade. Then came the artillery, followed by St. Clair’s brigade, which was accompanied by Washington and his staff. After St. Clair came the rest of the army, and its rear was closed by Captain Henry with three companies of Philadelphia militia.

By 2:00 A.M. the army was clearing the front of the British lines, and its van was crossing the little tributary that flowed into the Assunpink. The chosen “road” was really a woodsman’s path hacked through thick woods, and the countless stumps made the going miserable for the infantry, who stumbled over them in the darkness, as well as for the cursing artillerymen whose guns and limbers got hung up on them.

The strung-out column passed the log huts of the hamlet called Sandtown, taking the road to Quaker Bridge. Somewhere along that way, panic broke out among Captain Henry’s militia: they were being surrounded by Hessians! The companies broke and fled toward Bordentown—to the southeast. The rest of the army trudged along, oblivious to the racket in the rear. They were long since clear of the British at Trenton, marching in the pitch blackness under only a few dim stars. By the time the first light appeared in the east, the advance guard was already crossing Stony Brook, about two miles west of Princeton. One of Washington’s aides recalled that “the morning was bright, serene, and extremely cold [around 23°F], with a hoar frost which spangled every object.” The roads and fields were bare, with no snow, only the hoarfrost glittering under the early winter sun.

At Stony Brook the column divided according to plan. Brigadier General Hugh Mercer took the fork to the left in order to carry out the first part of his mission: to tear down the bridge at Stony Brook near Worth’s Mill, thus delaying any interference should any of Cornwallis’s units in Trenton come up in pursuit of the Americans. When General Sullivan’s command—the army’s main body—crossed Stony Brook, it took the right fork, to march up the Back Road and enter Princeton from its least-defended side on the east.

Something was also stirring at dawn on the British side. Cornwallis had left a rear guard of three infantry regiments—the 17th, 40th, and 55th—at Princeton under Lieutenant Colonel Mawhood. That gentleman, following his orders, marched out at dawn on 3 January intending to join General Leslie at Maidenhead, via the Post (Princeton-Trenton) Road, leaving the 40th Regiment to guard the baggage and stores left in Princeton. It was a quietly confident Mawhood who mounted his brown pony in Princeton and whistled for his two spaniels, who trotted along after his horse. His column was preceded by a troop of the 16th Light Dragoons, followed by the 17th Regiment and part of the 55th. Shortly before 8:00 A.M. a couple of Mawhood’s troopers, having crossed the Stony Brook Bridge, were topping the small hill that the Post Road crossed just west of the bridge at Worth’s Mill when they caught sight of the glitter of the sun on steel and moving figures coming from the southwest, up the road that paralleled Stony Brook. After a second look, a trooper took off to inform Mawhood that rebel troops were approaching. When Mawhood had seen things for himself, he was faced with immediate decisions. His primary responsibility was for the safety of the 40th and all those supplies and the wagon train back in Princeton. A rider was dispatched to alert the commander of the 40th to the possible approach of a rebel force. Mawhood’s next decision was a tough one to make. Should he carry on, carrying out his mission to the letter—that is, moving to join General Leslie at Maidenhead? Should he send a detachment southward to block the rebels approaching Stony Brook Bridge? Or should he countermarch his command and attack the threat with his whole force?

Mawhood’s personal reconnaissance had convinced him that it was part of the rebel army making for Princeton. By blocking the rebel force—perhaps a strong force; he could not yet be sure—he would protect Princeton and Brunswick as well as develop what was still a hazy situation. Accordingly, he turned the head of his column to reverse its march, recross the bridge, and retrace its route toward Princeton. His next action has been open to controversy. Historians have generally accepted that Mawhood then directed his column—preceded by some dragoons—back across Stony Brook Bridge and toward the orchard of William Clark, which lay about 1,000 yards to the east on a southerly slope of a large hill mass, the summit of which came to be known as Mercer Heights. T. J. Wertenbaker (“The Battle of Princeton”), however, has contended logically that Mawhood’s appreciation of the terrain decided him to seize the high ground of Mercer Heights itself, the most critical terrain feature of the area. Consequently, Mawhood pushed ahead a part of the 55th, which had been bringing up the rear of his column, to occupy Mercer Heights until he could join it there with his main body.

As his scouts and van approached Stony Brook Bridge, Mercer became aware of the movements of Mawhood’s main body only when it was recrossing the bridge. Evidently he then decided to head off Mawhood’s eastbound column. The sensible action was to turn his column to the right and seize the heights to his right, some sixty feet above the little valley of Stony Brook. He so ordered the new direction of his column, and as its head was ascending the hill, a sergeant saw a horseman looking toward them. They were discovered.

When Mercer reached the top of the hill, he could observe Sullivan’s division marching northward along the Back Road to Princeton and Mawhood’s column of British coming up from the west. Seeing this, and at the same time deducing the intent of the British commander, Mercer turned his column northeastward to screen Sullivan’s flank from an attack by Mawhood, which meant that his van would be passing through William Clark’s orchard.

Mawhood was marching back along the Post Road. When he came to a leftward jog in the road, he found it more practicable to leave the road and head eastward across the fields for Mercer Heights. While on this new leg of his march, Mawhood saw Mercer’s men approaching the orchard and hastened Captain Truwin’s cavalry troop forward to take up position to hit the rebel column in flank. Truwin’s dragoons dismounted and—as yet unseen by the marching Americans—deployed along the north side of the orchard, taking cover along a ditch and a fence that ran along that side.

Truwin’s men began the battle when they opened fire on the Americans. Although surprised, Mercer kept his head and turned his advance units to the left to return the fire with a volley. The British cavalrymen withdrew as the Americans advanced, yielding the fence line to the Americans. At first the Americans had the best of it, driving back the enemy and inflicting casualties, but things took a new turn when Mawhood came up with his 17th Regiment, which he quickly deployed into line, with his two fieldpieces going into action on the right of his line. Both forces were now fully deployed and exchanging volleys—at ranges, it is said, of as close as forty yards. The Americans got off three volleys before their fire slackened. This was one of those times when disciplined British musketry—all training and weapons designed to deliver maximum firepower at short range—came into its own. In addition, the two British cannons, firing canister at forty yards, took their toll of American casualties.

When Mawhood saw his enemy begin to waver, he seized his opportunity and ordered a bayonet charge. The British line came on at charge bayonet, and the infantrymen were carried away by battle fury, screaming to get at their enemy in close combat. Mercer’s men broke and fled. Many became vulnerable when they had to scale another fence on the orchard’s south side. Mercer was among them, his horse having taken a bullet in the foreleg. He was struck down by a musket butt, knocked to this knees, and though he tried to defend himself with his sword, was bayoneted seven times and left for dead. For a time Mawhood’s men were out of control. They pulled a lieutenant from his refuge under a farm cart where, in spite of his broken leg, he was repeatedly bayoneted. Lieutenant Yeates, already wounded, suffered thirteen bayonet wounds. Captain Fleming was shot dead while trying to rally his Virginians. Colonel Haslet of the Delaware Continentals was killed while trying to form a new line below the Clark farmyard.4 The British also captured the two guns of Captain Neil’s battery after the captain had died defending them. The guns were then turned on the American fugitives.

Mawhood finally got his men reassembled and formed into line again, this time south of the orchard, with most of his line behind a fence. He now had four guns, including the two captured pieces, which he positioned to the right rear of his line. Here he waited, ready to take on a renewed attack.

Meanwhile, Sullivan’s division, after taking the road to Princeton, had advanced up the Back Road until his column’s head was abreast of those companies of the British 55th that had just reached Mercer Heights. Having no way of knowing what strength the British had on the heights—Sullivan could see some redcoats in front of the trees on the summit but couldn’t tell how many units were hidden by the trees—he halted to keep them under observation. For a while there was an impasse. Faced with this large force of Americans marching on Princeton, the British commander of the 55th could not leave the heights to go to Mawhood’s aid. Nor could Sullivan continue his march with an enemy of unknown strength on his flank, one who also was in possession of the critical terrain, Mercer Heights. So neither British nor American commander could break away to join the fight that had begun in William Clark’s orchard.

WHILE SULLIVAN WAS MARCHING UP the Back Road, the gap in the American column created by the splitting off of Mercer’s men had widened to about a thousand yards. At the south end of that gap was the head of Cadwalader’s column of militia. Following Cadwalader was Hand’s regiment of riflemen, with Hitchcock’s brigade of New England Continentals bringing up the rear. With these American dispositions in column (at the time Mercer’s men were being chased by the bayonets of Mawhood’s 17th Regiment) one can appreciate the problem facing the next American leader, Cadwalader, as he led his men over the crest of the low hill south of William Clark’s farm. He had swung leftward and marched—in that good old phrase—”to the sound of the guns,” only to find, coming up the hill straight at him, a mob of Mercer’s panicked men in full flight from the fury of British bayonets. Beyond the mob of fugitives Cadwalader could see Mawhood’s reformed line, and in its front about fifty light infantry deployed as skirmishers. Cadwalader wasted no time in sending Captain George Henry with 100 men to turn the left flank of the British skirmishers. At the same time Captain Moulder’s battery of two guns went into position on the top of the hill to his left. The combined fire of Henry’s men and Moulder’s guns soon drove the British light infantry back to the cover of Mawhood’s main line.

Then Cadwalader made a fatal mistake. Instead of deploying his column of militia into line behind the crest where they would be screened from sight of the enemy, he led them over the hill into view of the British. Riding in front of his column, he ordered his detachments to peel off alternately right and left to come into line of battle. Such an exercise in minor tactics would have been difficult enough for even seasoned Continentals in that situation. For half-trained militia the result was a fiasco of milling men being shoved about by their sergeants and officers until some semblance of a line was formed while it advanced on the enemy. When that ragged line came within fifty yards of Mawhood’s waiting regulars, the storm of musket balls and canister it met head-on was too much. The disordered militia companies broke and turned tail. A hundred yards or so to the rear Cadwalader managed to rally several companies, but after they had gotten off a couple of volleys, they too disintegrated as a fighting force. In no time Cadwalader’s command had followed the example of Mercer’s men. The whole mob was making a run for the safety of the woods about a hundred and fifty yards to the southwest.

At this critical point Mawhood was doubtless tempted to order his entire command to charge his broken enemy and turn the resultant flood onto any American units behind it, to sweep them all away in what would become a smashing victory. One thing changed Mawhood’s mind. A young American captain, Joseph Moulder, commanding his two four-pounders, stood his ground on the hill and kept up a continuous rolling fire of canister into the British, which discouraged any idea of a frontal attack. For a time Moulder was all on his own, banging away without support, until 150 Pennsylvania infantry came up and took cover behind stacks and buildings around the Thomas Clark farmyard, off to Moulder’s left. Some of them failed to stay, but enough remained to keep up a fire that convinced the British that Moulder’s guns were now supported by several infantry units.

George Washington had been marching behind Sullivan’s division when he heard the firing to his left. As the rattle of musketry and the booming of cannon grew in volume, the commander in chief realized that something more than a skirmish was going on. In Richard M. Ketchum’s description, “a tall man on a white horse could be seen galloping toward the scene of battle with half a dozen aides and orderlies strung out behind him, and behind them came the veteran Virginia Continentals and Hand’s riflemen at a dead run” (The Winter Soldiers). While Hand’s riflemen were forming into line, Washington rode straightaway to aid Greene and Cadwalader in rallying the fugitives of Mercer’s and Cadwalader’s commands. As soon as order was restored in that area, Washington could turn his attention to Daniel Hitchcock’s brigade of Continentals, which was coming up on the double.

Washington directed Hitchcock to form a line to the right of Cadwalader’s men, who were getting back into line. The gallant Hitchcock (only ten days were left to him before he was to die of tuberculosis) lined his veterans up in parade order: Massachusetts under Henshaw on the left, the three Rhode Island regiments in the center, and Nixon’s New Hampshiremen on the right. Washington saw to it then that Hand’s riflemen fell in on the right of Hitchcock’s brigade, and soon an American line of battle stretched from the front of Moulder’s battery all across the hillside to the north, where Hand’s regiment could outflank the left of the British line. Washington gave the signal for the advance, posting himself in the right front of Cadwalader’s line, and from there he led the concerted attack of the whole American line.

As the big man on the white horse came within easy musket range of the British line, there was a climactic instant when everything hung in the balance. The British infantrymen looking over the barrels of their muskets were astounded to see the rebel commander right in their field of fire.

When he was thirty yards from the enemy, Washington gave the command to fire. For seconds the smoke from Americans and British volleys hid Washington from sight. Colonel John Fitzgerald of his staff covered his eyes so that he would not see his commander blasted from the saddle. Yet when the smoke began to clear, there was Washington standing in his stirrups, calmly waving his men forward.

For moments the Pennsylvania militia hesitated. Then Hitchcock’s firm line, marching forward in perfect order, paused to fire their first volley, and advanced again. On the far right, Hand’s riflemen were swinging around in a scythelike curve to threaten Mawhood’s left flank. Over the roar of musketry Moulder’s guns continued to thunder their volleys of grape and round shot, cutting wide swaths in the British ranks. The alternate fire and advance of Hitchcock’s brigade brought it within charging distance, and finally the militia, following Washington, joined in the surge of the closing-in assault.

The British continued to fire by volley. Mawhood even tried shifting part of his line leftward to counter the threat of Hitchcock’s and Hand’s envelopment. The united assault of the whole American line, however, was too much for the British. They fell back, by platoons at first, still trying to cover their artillery, until the inspired Americans swept the British soldiers out of their formations and overran the artillery, capturing all four guns. Pockets of British infantry were fighting to escape the inevitable encircling of Hitchcock’s and Hand’s men. Finally, when all was hopeless, British soldiers had their turn in breaking and running. Mawhood, rallying a group of his toughest and most disciplined men, made a final, gallant effort. He led this small body in a desperate bayonet assault that broke through the encirclement to the rear, where most of the group escaped across Stony Brook Bridge. Others scattered in all directions, some toward Maidenhead, some toward Princeton; some others were pursued for miles up Stony Brook and toward Pennington. A few dragoons tried to make a stand on the hill west of Worth’s Mill, but they too were swept away by the ruthless American pursuit.

The pièce de résistance in the whole affair was the American commander in chief shouting, “It’s a fine fox chase, boys!” while leading the pursuit. (One pauses to wonder whether Washington was unconsciously voicing thought to the several references Cornwallis had made to bagging a fox.) Followed by the Philadelphia Light Horse, he gloried in the chase until finally his blood cooled, the general again took over, and he turned his escort back in the direction of Princeton.

As for the standoff between General Sullivan and the British 55th Regiment at Mercer Heights, part of Mawhood’s orders to the commander of the 55th had included going to the support of the 40th in Princeton should the situation so dictate. So the 55th marched on, and when it came to a stream crossing on the Back Road, a place known as Frog Hollow, there was the 40th deployed in line on the north side of the hollow! The commander of the 55th immediately took up position, extending the line of the 40th to its left. There the regiment and a half stood, prepared for battle.

Sullivan followed on the heels of the 55th and, once that unit had crossed Frog Hollow to deploy alongside the 40th, sent two regiments to attack the British left. Hardly had the Americans gotten within good musket range—sixty yards from the British line—when, for reasons still not clear,5 the redcoats panicked and streamed away in flight into Princeton. With both enemy regiments in pell-mell flight, Sullivan was once more at their heels. Some of the mob escaped by fleeing toward Brunswick; the rest, seeing they were about to be overtaken, took refuge in Nassau Hall. They had plenty of room, the building being the largest in the colonies at the time. They knocked the glass out of windows and prepared for a last-ditch defense.