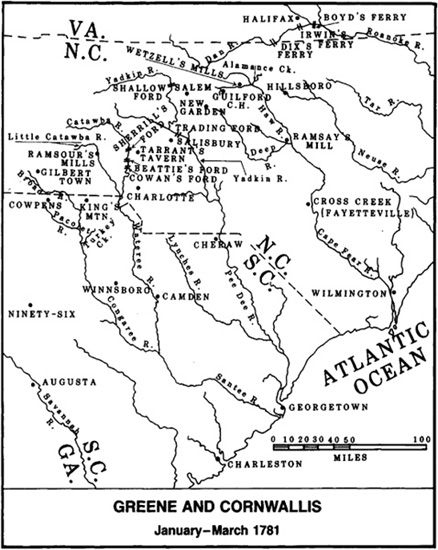

HAVING WON HIS BATTLE, DANIEL MORGAN found himself, ironically, in considerable peril. Cornwallis’s army was still between him and Greene. After Pickens rejoined him the day after Cowpens, on 18 January, Morgan and his whole command marched together until they reached Gilbert Town. There Pickens was detached with the major share of the militia and Washington’s cavalry to march the prisoners captured at Cowpens to Island Ford on the upper Catawba, where they could be turned over to other escorts and moved to Virginia. Morgan then continued his march via Ramsour’s Mills to the main Catawba, which he crossed at Sherrill’s Ford on 23 January, and encamped on the north side—safely, for the time being.

Meanwhile, Cornwallis remained at Turkey Creek, readying his force to move out. He was now irrevocably committed to moving north because all his troops and material for campaigning were concentrated with him, and by his order the far-away fortifications of Charleston had been razed.

With 3,000 excellent troops at hand, Cornwallis did not leave Turkey Creek until 19 January, and then in the wrong direction. Underestimating Morgan’s marching capability as well as his anxiety to be reunited with Greene, the earl marched to the northwest toward the Little Broad River, intending to cut off Morgan. En route Cornwallis learned from Tarleton’s search of the area that he was in error, and he changed his direction toward Ramsour’s Mills, where he arrived early on 25 January, only to learn that Morgan had passed there two days before.

Cornwallis now had to reevaluate his estimate of Morgan’s capabilities and make a painful decision. In less than five marching days Morgan had covered over a hundred miles and had placed two rivers between the two armies. The British commander’s decision—no doubt arrived at only with difficulty—was to strip down his army and convert it into a mobile force able to march fast enough to catch the Americans. To do so he took two days to destroy all his superfluous impedimenta. Into the fires went the tents and all the provisions that could not be carried in knapsacks. Then the wagons and their loads were burned, saving out only the essential ones for hauling ammunitions, salt, and hospital stores, and four others for the transport of the sick and wounded. Cornwallis set the example for his officers by watching most of his personal belongings go up in smoke, and his officers followed his example (the latter must have been a tremendous lightening of encumbrance, considering the typical British officer’s “campaign comforts”). But Cornwallis didn’t stop there; what followed was—as any old soldier could attest—no less than a tragic end to a harrowing scene. All the rum casks were smashed, “and the precious liquor was poured out on the ground.”

After two days of holocaust, Cornwallis set out to catch up with Morgan. A rapid march from Ramsour’s Mills eastward toward Beattie’s Ford ended in pure frustration, however, because the Catawba was impassable due to heavy rains. Cornwallis halted four miles short of the ford and was held up there for two days, through 30 January.

NATHANAEL GREENE, IN HIS CAMP AT CHERAW, didn’t get word of the victory at Cowpens until 23 January, but with it came the realization of Morgan’s danger if he were caught by Cornwallis’s main force. Greene was not without resources; with typical foresight, when he had made his decision to divide his army, he sent “Lieutenant Colonel Carrington, his quartermaster, to explore and map the Dan River, and Edward Stevens, Major General of Virginia militia, and General Kosciuszko to the Yadkin and the Catawba for the same purpose. They were also to collect or build flatboats to be carried on wheels or in wagons from one river to another” (Ward, The War of the Revolution). Consequently Greene was able, after 23 January, to give orders to set things in motion. He dispatched Carrington back to the Dan River to assemble enough boats on the south side to transport his whole force. He then directed General Huger to march his wing of the army to Salisbury, North Carolina, where he could anticipate joining Morgan’s force. Huger started his 125-mile march on 28 January, the same day that Greene, escorted only by a guide, one aide, and a sergeant’s guard of dragoons, left Cheraw to ride to Morgan’s camp east of the Catawba. That he made it through Tory country in only two days, across a rough stretch of some 120 miles, makes it seem that luck played an important part in getting him safely to Morgan’s camp on 30 January.

As soon as Greene and Morgan began comparing notes, it became apparent that the latter was more concerned with the safety of the army than its raison d’être. Morgan thought that only a fast, strategic withdrawal westward into the mountains could save the army. Greene, with his strategic objectives uppermost in mind, took an opposite—and prevailing—view. When Morgan told him of Cornwallis’s baggage burning and his obvious intent of driving north at all costs, Greene is said to have exclaimed, “Then, he is ours!”

It was then that Greene added another bold concept to his strategy: If Cornwallis were to carry out his “mad scheme of pushing through the country,” Greene would do no less than accommodate him. In so doing, the American commander would retreat to the north, where Cornwallis would be sure to take the bait and follow. Then Greene would entice his opponent farther and farther north, stretching the British supply lines to the breaking point while the Americans were drawing closer to supplies in Virginia. And during the retreat Greene would keep his forces just out of reach of his enemy’s advance elements, keeping alive in Cornwallis the hope that he would bring the Americans to battle. Finally, when Greene had gathered enough strength and the right opportunity was presented, he would turn and strike his enemy. Morgan apparently was shocked at the dangers inherent in such a bold plan, and declared he could not be held responsible if it met with disaster. Greene, never shying away from responsibility, replied that Morgan should have no such worries, “for I shall take the measure upon myself.”

Accordingly Greene sent a letter to Huger informing him of his plan and urging him to make haste in his march to join Morgan’s main body at Salisbury. He also dispatched orders for Light-Horse Harry Lee’s legion to break off operations with Marion, then somewhere along the lower Pee Dee River, and rejoin Greene at once. By then the floodwaters of the Catawba had begun to recede, so Greene was able to direct Morgan to continue his main body’s march to Salisbury. With those matters taken care of, Greene, accompanied by Morgan, met William Washington and General William Davidson near Beattie’s Ford to plan the defense of the fords of the Catawba in the area. Afterward Morgan and Washington rode off to rejoin their commands, and Davidson was left to deploy his militia to defend the fords.

Cornwallis meanwhile had kept a close eye on the Catawba’s waters while formulating his crossing plan. Believing that Morgan’s main force was still near Beattie’s Ford, the earl planned to entrap him by executing two crossings of the river. The first was to be a feint at Beattie’s Ford by a division under Lieutenant Colonel Webster, who would keep Morgan occupied, starting with an artillery preparation. Cornwallis would take the main body across at Cowan’s Ford, about five miles downstream from Beattie’s, then swing north to encircle Morgan.

Morgan, however, had marched away from his camp on the evening of 31 January, headed toward Salisbury and Trading Ford, while Cornwallis’s forces had begun moving only by early morning of 1 February. At Cowan’s Ford the British ran into real difficulties. The ford was 500 yards wide, and the water three to four feet deep and still running fast. Halfway across the river, the ford split into two parts. The wagon ford ran straight ahead through deeper water, while the so-called horse ford split off at a forty-five-degree angle to the south and ran through shallower water. Led by Dick Beal, their Tory guide, the British troops plunged ahead in waist-deep water. About a hundred yards into the river they were taken under fire by the small party at the wagon ford. About halfway across, Beal lost his nerve and disappeared, without telling the officer leading the advance that he should break off to the right and take the horse ford to its landing below. As a result, the column pushed on, straight ahead through the deeper wagon ford, where it suffered considerable losses. Even the three generals’ horses became casualties: Cornwallis’s horse was wounded but didn’t collapse until it reached the far bank; Generals Leslie and O’Hara were thrown when their horses were swept down by the current.

Discipline and plain raw courage carried the British through, and the leading ranks stormed the bank, loaded their muskets, and drove off the defenders. General Davidson heard the firing and led a detachment from the horse ford up to reinforce the wagon ford. When he got there he took a bullet from a Tory rifleman and fell dead from his horse. With that his men broke and fled before the British volleys.

Cornwallis was across at Cowan’s Ford, and later that day Webster crossed unopposed at Beattie’s. The British commander rapidly reorganized to resume the chase after Morgan, who was already well on his way to the Yadkin River. Tarleton meanwhile was screening the British front and simultaneously reconnoitering for rebels in the direction of advance. About ten miles from the river he found and attacked, in his usual hell-for-leather style, a group of Davidson’s militia at Tarrant’s Tavern. Two or three hundred rebels were dispersed for good, Tarleton reporting that he had routed 500 and killed 50, with a loss of only 7 of his own men. His concluding statement summarized the real results of Tarrant’s Tavern: “This exertion of the cavalry succeeding the gallant action of the guards in the morning, diffused such a terror among the inhabitants, that the King’s troops passed through the most hostile part of North Carolina without a shot from the militia.”

Tarleton’s cavalry also came close to capturing Greene, who had gone alone to a prearranged place to meet the militia withdrawing from the fords. At midnight a messenger came with the news of Davidson’s death, the dispersal of the militia, and the crossing of Cornwallis’s force. Greene then rode on to Salisbury. In Christopher Ward’s description, “At Steele’s Tavern in that village he dismounted stiff and sore to be greeted by a friend. ‘What? Alone, Greene?’ ‘Yes,’ he answered, ‘alone, tired, hungry and penniless.’ Mrs. Steele heard him. After getting him a breakfast she brought two little bags of hard money and gave them to him. ‘You need them more than I do,’ she said. The contents of those two little bags constituted the entire military chest of the Grand Army of the Southern department of the United States of America.”

In the next nine days, beginning on 2 February, Greene and Morgan carried out the series of marches that have become famous as the Retreat to the Dan. The Dan River was the final objective of Greene’s strategic moves. He was keenly aware that only after he had gotten his army across that river could he rest his troops, replenish stores, and, most important, gather in reinforcements from Virginia. Both of the opposing armies were now across the Catawba, but there remained three major rivers to cross: the Yadkin, the Haw, and the Dan. And if the rains of midwinter should set in and render fords impassable, only boats could ensure timely river crossings. We have seen that Greene’s foresight, plus the efforts of Carrington and Kosciuszko, had made the boats available, but they had to be at the right place at the right time. Greene could leave the execution of that part of his plan to those two capable officers, but the Dan River crossings posed another problem, for Cornwallis would probably close on his trail at crossing time. The upper river had usable fords; the lower river could be crossed only by boats at three ferry sites: in order from upper to lower, Dix’s Ferry, Irwin’s Ferry, and Boyd’s Ferry. Greene’s plan was to deceive his enemy into thinking that the American main body was headed for the fords of the upper Dan, when in reality it would make a last-minute switch of direction to cross at a ferry site on the lower Dan.

WHILE HE WAS STILL AT STEELE’S TAVERN, Greene sent a message to Huger to change his direction of march to the northeast and meet up with Morgan at Guilford Courthouse. He then rode to join Morgan’s column.

Cornwallis, following Tarleton’s action at Tarrant’s Tavern, had reunited the two divisions of his army at a point on the road to Salisbury. There he formed a mobile advance force to move ahead and catch Greene and Morgan before they could cross the Yadkin. The force, under General O’Hara, was made up of the cavalry and O’Hara’s mounted infantry. It set out at once, while Cornwallis remained with his main body to supervise a second baggage burning. This time he reduced the number of wagons, gaining more teams to pull the others through the soft red clay.

O’Hara, pushing on, was well aware that the rain-swollen Yadkin was above fording depth. Here, if ever, was the time and place to catch Morgan. When his advance party came in sight of the Yadkin’s west bank, it came upon some wagons guarded by militia. The vanguard quickly dispersed the militia, only to discover that the American army and all its boats were on the other side of the river. Greene’s careful planning and Kosciuszko’s execution had made possible the first major boat crossing on 2 and 3 February.

Marching through rain and over miserable roads, Cornwallis made it into Salisbury by mid-afternoon of 3 February. The Americans had all the available boats, and the Yadkin River was too high even for fording by horses. Cornwallis sent forward a few artillery pieces, with which O’Hara attempted to bombard Greene’s camp across the river. Because the American position was protected by a high ridge, no damage was done “except to knock the roof off a cabin in which he [Greene] was busy with correspondence.”

While at Salisbury, Cornwallis received reports that there were insufficient boats on the lower Dan to enable Greene to use the ferries. This false—or misconstrued—information was to prove costly indeed in Cornwallis’s future moves, since it added to the earl’s deception that Greene would have to use the fords of the upper Dan. Cornwallis saw that he could operate on interior lines by interposing his army between what he thought were the still-divided forces of Greene and Huger and defeat them in detail. His plan was to head northwest from Salisbury, cross the Yadkin at Shallow Ford, which was still passable in spite of the rain, get to Salem, and from there strike out at the separated American forces. Accordingly he sent Tarleton up the Yadkin, which he crossed at Shallow Ford on 6 February. Cornwallis followed, leaving Salisbury on the seventh and reaching Salem on the ninth.

WHAT WERE GREENE’S FORCES DOING AFTER Morgan had crossed the Yadkin on 3 February? On the evening of the following day Greene and Morgan marched north out of their camp at Trading Ford. Their initial direction must have added to Cornwallis’s misconceived idea of the objective of the march. On the way, the Americans halted at Abbott’s Creek, not far from Salem, long enough to confirm reports of Cornwallis’s whereabouts. They then switched direction to the east to make an incredible march to Guilford Courthouse, covering forty-seven miles in forty-eight hours despite unceasing rain, terrible roads, and hungry men who marched on short rations for two days. Reaching Guilford on 6 February, they encamped and waited for Huger to join them. The next day Huger’s scarecrow force arrived “in a most dismal condition for the want of clothing, especially shoes” but without the loss of a man!

While at Guilford Courthouse, Greene seems to have wavered momentarily in his purpose. His forces were concentrated, Lee’s legion had arrived with Huger, and he hoped his still-scanty force of 2,000 would be joined by local militia as well as reinforcements from Virginia. Moreover, he could hope to build up provisions and receive ammunition along with the hoped-for Virginia troops. Greene studied the terrain and considered it suitable for a good position to confront Cornwallis. He laid his considerations before a council of war, which decided against such a stand. The American commander then wasted no time in reorganizing his units for continuing the march to the lower Dan. He sent Pickens back to recruit militia, arouse the countryside, and raise havoc in general with British supply lines and foraging parties.

Next Greene organized a light, mobile force designed to act both as rear guard and decoy force for Cornwallis’s advance elements. The force totaled 700 men and was composed of William Washington’s cavalry, with Lee’s legion cavalry attached as well as John Eager Howard’s infantry, which included his 280 Continentals, the 120 infantrymen of Lee’s legion, and 60 Virginia riflemen. Specifically, the mission of the light force was to keep between Greene’s main body and the British, delaying the enemy wherever possible while keeping him deceived in regard to the army’s true objective: the ferries on the lower Dan.

Command of the force was offered to Morgan, but he declined, because, as he told Greene in writing on 5 February, “I can scarcely sit upon my horse.” The curse of hemorrhoids had been added to his rheumatism and sciatica, making him unfit to campaign further. A reluctant Greene accepted the loss of Morgan: “Camp at Guilford C.H. Feb. 10th, 1781. Gen. Morgan, of the Virginia line, has leave of absence until he recovers his health, so as to be able to take the field again.” It was to be Morgan’s last campaign with regular forces.

The command then went to Colonel Otho Williams of Maryland, a happy selection indeed; he was an officer with a record of distinguished service and destined to add brilliant accomplishments to his record in the near future. While Williams was organizing his light force, Greene, according to Lee’s Memoirs, was listening to Lieutenant Colonel Carrington’s suggestions for crossing the lower Dan “at Irwin’s Ferry, 17 [should read 70] miles from Guilford Courthouse, and 20 miles below Dix’s. Boyd’s Ferry was four miles below Irwin’s; and the boats might be easily brought down from Dix’s to assist in transporting the army at these and lower ferries. The plan of Lt. Col. Carrington was adopted, and that officer charged with the requisite preparations.”

Williams left Guilford Courthouse on 10 February, turning west toward Salem to take a road which would put him between Cornwallis and Greene’s main body. On the same day, Greene left, taking the main body on the most direct route to Carrington’s ferry sites.

Cornwallis had at first thought to threaten Greene by feinting eastward, but when he learned of the march of Williams’s force coming swiftly across his front, the earl took the bait and headed for the fords of the upper Dan, thus, as he thought, keeping Greene from his objective.

The subsequent pursuit of Greene by Cornwallis has been referred to as the “race to the Dan.” The conditions under which the two armies marched, however, were anything but conducive to a race. It was still midwinter, and when it wasn’t raining in northern North Carolina, it was snowing. The oft-mentioned red-clay roads would freeze at night and soften into sticky mud in the “warmth” of the day. To top it off, the Americans had to exist on short rations, and the clothing of most soldiers was in tatters. The British soldiers were not a great deal better off, for their uniforms were wearing out and usually wet through. There were no tents on either side: the Americans didn’t have time to erect or strike them, and the British soldiers’ tents had been the first things thrown on the fires of Cornwallis’s baggage burnings.

Soon after heading out in pursuit of Williams, Cornwallis found that they were marching on parallel roads. His own column had become strung out over a distance of four miles, so he halted long enough to close it up, then drove his troops on, pushing them to the limit. They made up to thirty miles a day, a nearly unbelievable march rate under the conditions. Williams, if he were to keep ahead of his enemy’s van, had to move even faster. His other and constant anxiety was maintaining a continuous surveillance of the roads to his right and rear to ensure that the British did not get between him and Greene. This meant patrolling and picketing on a twenty-four-hour basis, with half of his troops screening his own force at night to avoid being surprised. Hence his men got only six hours rest out of forty-eight, and started each day’s march at 3:00 A.M. A hasty halt for breakfast provided the only meal of the day. The British may have marched on better rations, but they too were driven constantly in their dogged pursuit.

A picture of the opposing forces at this time would show three parallel columns heading generally northward. They were echeloned, with Greene’s main body on the left and leading. Williams was in the center, and to his right and rear were the pursuing British. On 13 February the picture began to change between the forces of Williams and Cornwallis. Before dawn Tarleton reported to Cornwallis that the enemy’s main body was actually moving toward the lower Dan. The earl decided to create a deception of his own by directing his vanguard to continue following the same route parallel to Williams while he and the main body made a forced march over a causeway that would bring him onto Williams’s rear. He came very close to catching up to the American rear, and might have caught the light troops at breakfast had it not been for a farmer who warned the Americans that the British were coming on fast and were only four miles away. Williams sent Harry Lee back to check on the farmer’s information, and the result was a sharp little action with Tarleton’s cavalry, which lost eighteen men in the fight. Just before Lee and his cavalry detachment engaged the enemy, some of Tarleton’s dragoons cut down Lee’s bugler, a fourteen-year-old, and killed him as he lay defenseless on the ground. After the engagement Lee was going to hang in reprisal the captured leader of the dragoon detachment, Captain Miller, who argued that he had tried to save the bugler’s life but had not succeeded. Miller’s life was spared, not only due to his defense but also because of the approach of Cornwallis’s advance guard. Lee had no choice but to gallop away and rejoin the rear guard.

While the cavalry clash was going on, Williams decided that he had gone as far as he could in leading Cornwallis toward Dix’s Ferry. Now, in order to save his own command while continuing to cover Greene’s rear, it was time for him to change to a road that would take him more directly to Irwin’s Ferry, where he could get across the Dan behind Greene’s main body. Since Lee had caught up with him, Williams told him of his plan to change to the new route and ordered him to continue screening the light force’s rear. Williams then moved to Irwin’s Ferry.

Cornwallis was not fooled for long, however, and for a second time his advance party came close to catching Lee’s men at a delayed breakfast. The American troopers had gone up a side road to a farmhouse and were just getting into their meal when shots were heard from the direction of an outpost. At once Lee got his infantry on the way, then went back to support his outpost in checking the enemy’s advance party. The Americans escaped by the skin of their teeth, Lee’s cavalry being hotly pursued by the British dragoons and saved only by having better horses.

By now Cornwallis was convinced that a final, all-out effort would enable him to catch the Americans before they could cross the Dan. All through the day of the thirteenth and into the night the weary British were pushed on by their commander. Several times the British vanguard was within a musket shot of the American rear guard, and it seemed likely that the light troops would have to make a stand. Each time Lee’s troops got away. Just before dusk Lee’s men caught up with Williams. It soon became evident that Cornwallis was not to be halted by darkness, however, so Williams had to keep going, his men stumbling along in the dark over the rough road.

Williams now sent part of Lee’s cavalry ahead to try and connect with Greene’s rear. It was not long before they saw, ahead of them, a distant line of campfires. They were as dismayed as they had been surprised. Greene hadn’t gotten away after all, and here they all were, with the British closing in on them. “All their struggles, all their hardships had been for naught. Now there was only one thing to do; they must face their pursuer and fight.” However, when Williams came up and led them forward, they found that the campfires were indeed Greene’s, but he had moved on two days before. The fires had been kept burning by the locals, who knew that the light troops were coming.

Williams, however, could allow no halt. He had gotten a message from Greene which told him that the main body’s baggage and stores had been sent on to “cross as fast as they got to the river.” Finally word came to Williams from the rear guard that the British had halted, so he could halt too—but only for a couple of hours. By midnight the light troops were pounding on again, their feet breaking the half-frozen ruts and sinking into the soggy red clay beneath. Even though their pursuers were having the same troubles, at times they seemed to be gaining on Williams’s weary troops. Both sides pushed on, and during the whole morning of 14 February neither force made a rest halt of more than an hour.

Then, sometime before noon of the fourteenth, another of Greene’s couriers met Williams with a message dated 5:12 P.M. of the day before: “All our troops are over and the stage is clear . . . I am ready to receive you and give you a hearty welcome.” Williams passed the word down the columns, and the roll of American cheers was so loud that General O’Hara’s advance party could hear them and must have realized that the race might be won by the Americans.

There were still fourteen long miles to go before reaching the river. The news of Greene’s dispatch had so lifted the American spirits that Williams’s troops, like a runner getting his second wind, were giving it their all in this final stretch.

As for O’Hara, for all the adverse sounds of rebel cheers, he was more determined than ever to catch up to and trap his enemy with his back to the river. Equally determined to cross before O’Hara could intervene, Williams sent Lee back in mid-afternoon again to cover the rear and delay the British. Meanwhile, the light infantry pressed forward, having gained on O’Hara’s van: the British had marched forty miles in twenty-four hours, but the Americans had covered those same miles in sixteen hours.

At last, just before the end of daylight, Williams’s leading troops reached the ferry site and loaded up on the boats to be ferried across. The boat transports kept moving the infantry until the last of them reached the other side after dark. By 8:00 P.M. on 14 February Lee’s horsemen arrived and began crossing on the boats that had finished transporting the infantry. Carrington was directing the crossing in person, and it was he who had Lee’s horses “unsaddled and driven into the water to swim across, while their weary riders clutching their saddles and bridles, crowded into the boats.” Lee then recorded that “in the last boat the quartermaster-general attended by Lt. Colonel Lee and the rear troops, reached the friendly shore.” Less than an hour later, O’Hara arrived at the river to find his enemies all safe on the far side. Page Smith summed up O’Hara’s sense of bitter letdown: “All the weary miles, the burned baggage and wagons, the destroyed tents, the short rations had gone for nothing” (A New Age Now Begins). Cornwallis learned of the failure a little later, and with it the not-surprising news that the river was too high to ford and all the boats were gone with the Americans.

Obviously the boats were the key to Greene’s getting his army to safety. The fact that they were where they were needed, when they were needed, is ample testimony to Greene’s genius and the skill and energy of Carrington and Kosciuszko.

Greene had now been driven out of the Carolinas, and no longer was there an organized Patriot force located south of Virginia capable of fighting a British army. Yet, by retreating north of the Dan, the American general had not only saved his army but was still capable of preventing Cornwallis from marching into Virginia and linking up with British forces there to subdue the rest of the South.

CORNWALLIS AND THE BRITISH NOW FACED a critical operational problem. To get into Virginia he had to cross the Dan and the Roanoke, and there were no boats to make the crossings. If he tried to use the fords on the upper stretches of river, Greene would know of his moves in time to move his army to hold any crossing site. And even if he should outmaneuver Greene, an unlikely outcome in view of the painful experiences of the past weeks, the American could fall back and be reinforced by the troops that Baron von Steuben was raising in Virginia, and would be the stronger in numbers. So there was no way for the British at this time to drive to the north.

The earl’s other problems were formidable as well. In pursuing Greene he had left his main base over 230 miles behind, and there was no way to replace all the stores and matériel destroyed back at Ramsour’s Mills. His army had swept the nearby countryside clean of provisions and forage, and Pickens had reportedly raised some 700 militia with which he could attack British foraging parties or supply trains. Obviously Cornwallis could not stay where he was, either.

He took the only way out left to him. He would make a safe march back to Hillsboro, where the Tory population would surely rally to him now that Greene had been driven out of North Carolina. His mind made up, Cornwallis marched to Hillsboro, set up the royal standard, and issued a proclamation: “Whereas it has pleased the Divine Providence to prosper the operations of His Majesty’s arms, in driving the rebel army out of this province, and whereas it is His Majesty’s most gracious wish to rescue his faithful and loyal subjects from the cruel tyranny under which they have groaned for many years [all were invited to repair] with their arms and ten days provisions to the royal standard.”

Some forty miles away, on the north side of the Dan, there were causes for rejoicing and “enjoying wholesome and abundant supplies of food in the rich and friendly county of Halifax.” There Greene rested his men while gathering stores and intelligence of both friendly and enemy forces. In Greene’s way of thinking, the crossing of the Dan had ended one campaign; now it was time to start another. In spite of his urgent need for reinforcement, he would not hold up operations waiting for them. The high waters of the Dan were subsiding, and Cornwallis might seize the initiative to try new maneuvers against him. Moreover, Steuben’s Continental recruits might be weeks away from joining him. Uppermost in his consideration was the nagging realization that the climax of all his retrograde operations had not yet been reached—his turning back to strike the enemy he had enticed so far from his base, and who now would be weakened enough to be vulnerable to Greene’s masterstroke. In Greene’s mind that time had come. He must now reenter North Carolina and move against Cornwallis with the forces he had at hand.

In short order Greene transformed decisions into actions. On 18 February he sent Lee with his legion and two companies of Maryland Continentals to reinforce Pickens in harassing British communications and foraging parties, as well as keeping down Tory uprisings. Greene’s next move was to send ahead Colonel Otho Williams with the same light infantry force that he led so brilliantly during the retreat. Williams crossed the Dan on 20 February, two days after Lee. About the same time, escorted by a detachment of Washington’s dragoons, Greene rode to meet with Pickens and Lee near the road running from Hillsboro to the Haw River. There he told them of his plans to cross the Dan with the rest of his army and move in the general direction of Guilford Courthouse. Greene then returned to the main army.

Sometime later, Pickens and Lee set out to act on a piece of hot intelligence that told them that Tarleton had been sent to escort a force of several hundred Tory militia to Hillsboro to join Cornwallis. The Tories, a force of Royal Militia that had been raised between the Haw and Deep rivers, were presently en route to join Tarleton.

On their way to locate the enemy, Lee’s troopers picked up two Tory countrymen, who were duped into thinking that Lee’s men were Tarleton’s, an understandable mistake since the cavalrymen of both legions wore green jackets and similar black helmets. They sent one of the Tories ahead to Colonel John Pyle, who commanded the 300-man Tory force, asking him if he would form his men in a line facing the road so that “Colonel Tarleton” and his troops could pass on to their bivouac area for the night. Completely taken in, Pyle not only formed his line on the right side of the road but also took post on the right of the line where he could greet the British cavalry leader when he passed.

In the meantime the Maryland light infantry and some of Pickens’s militia were following Lee’s dragoons, the infantry concealed by the woods through which the road ran. Lee rode down the road at the head of his men, in his own words, passing along the line at the head of the column “with a smiling countenance, dropping, occasionally, expressions complimentary to the good looks and commendable conduct of his loyal friends.” Lee went on to say that his only intention was to reveal himself and his men to Colonel Pyle and suggest that he surrender and disband his men, and send them home in order to avoid harm coming to them. According to American accounts, Lee was about to deliver his surrender demand—having first grasped Pyle’s hand in his role as Tarleton—when firing broke out at the rear of Lee’s column. Evidently some of the Tories at the opposite end of the line had spotted the American infantry in the woods and fired on them.

Lee’s troopers fell upon the surprised enemy with slashing sabres. The Tories were caught like rounded-up rabbits, and the rest of the action, known as Pyle’s Defeat, or Haw River, was nothing less than a massacre. Of the 300 or more Tory militia, 90 were killed on the spot and 150 who could not get away were left “slashed and bleeding.” Lee’s loss was one horse wounded. If Pyle’s Defeat was not a massacre, it would be hard indeed to accept the American assertion to the contrary, since the casualties with their wounds spoke for themselves.

Moral issues aside, the results of Haw River were unmistakable. The Tory populace throughout the region was thoroughly subdued by the news of the action, and few Tories rallied to the royal standard in North Carolina.

GREENE KEPT HIS WORD WITH LEE AND PICKENS, crossing the Dan to join them on 23 February after his main body had been reinforced by 600 Virginia militia under General Edward Stevens. Greene’s immediate operations were directed toward backing up Pickens with the support of Williams’s light troops while the main army was building up its strength. The buildup was going to take time, but eventually reinforcements would be forthcoming in the form of Steuben’s recruited Continentals and more Virginia and North Carolina militia. In the interim Greene directed his next marches toward Hillsboro.

Cornwallis, at the same time, was arriving at a decision to leave that place—not because of Greene’s latest move but because of the area’s decreasing means of supporting the British forces encamped there. Provisions were running critically short, and Cornwallis’s commissaries were hard put to force more out of a disgruntled people. These were the same people who, after Pyle’s Defeat, had suddenly ceased to provide recruits. Thus it was to Cornwallis’s advantage to move to greener pastures. Consequently, on 27 February he moved to an encampment south of Alamance Creek. This placed him near a junction of roads that permitted moving east to Hillsboro, west to Guilford Courthouse, or downriver to Cross Creek and Wilmington.

On the day that Cornwallis departed from Hillsboro, Otho Williams crossed the Haw River and took up a position on the north side of Alamance Creek, several miles from Cornwallis’s camp on the south side. Williams now led a formidable force, his light troops having been reinforced by Pickens’s command, which included Lee’s legion, Washington’s cavalry, and about 300 Virginia riflemen under Colonel William Preston. Williams’s force closed in its position on the night of 27–28 February, and the next morning Greene moved the main army to a position about fifteen miles above the British camp.

The American commander had no intention, however, of remaining there. He planned to keep his forces in motion and thus keep Cornwallis off balance while the Americans controlled the countryside and continued to gather in reinforcements. At the same time Williams would also be on the move for the same general purpose, and in addition would act as a screening force for Greene’s main army. On the British side Tarleton began to carry out his screening mission in much the same way.

All this shuttling back and forth served the Americans’ purpose in at least one way—they had begun to annoy Cornwallis. He decided on a surprise move of his own, and marched at 3:00 A.M. on 6 March in the hope of surprising Williams. In so doing he anticipated drawing Greene to the support of Williams, and thereby into a general engagement. In the earl’s view, the American commander could not afford to stand off and see his invaluable covering force destroyed.

As usual, the American intelligence was more timely and accurate than British intelligence. A scouting party of Williams’s on another mission on the night of 5–6 March learned that Cornwallis’s army was on the move. When Williams got the report, Tarleton’s cavalry and Cornwallis’s van of light infantry under Lieutenant Colonel Webster were already within two miles of Colonel William Campbell’s (the same red-headed Scot of Kings Mountain) Virginia militia, which was outposting Williams’s left. Williams dispatched Lee’s and Washington’s cavalry to support Campbell while he hurried the rest of his force toward Wetzell’s Mills, a ford across Reedy Fork. Williams got across the ford first, and the swift arrival of the British van brought on the engagement known as Wetzell’s Mills, in which some twenty casualties were taken on each side. Greene was not pulled into the action, but he did move from his last position near Reedy Fork and camped at the ironworks on Troublesome Creek.

After that affair both armies remained inactive for the next eight days. During the period Greene’s most anxious hopes were beginning to be fulfilled. Steuben’s Continentals arrived at long last, 400 of them, under Colonel Richard Campbell. About the same time the long-awaited Virginia militia joined Greene: almost 1,700 men organized into two brigades under Brigadier Generals Edward Stevens and Robert Lawson. Then came two brigades of North Carolina militia, totaling 1,060 men, commanded, respectively, by Brigadier General John Butler and Colonel Pinketham Eaton. While overseeing the reorganization of his army, Greene decided to disband Williams’s force and return its units to their parent regiments, with the exception of Captain Kirkwood’s famed Delaware company of Continentals and Colonel Charles Lynch’s Virginia riflemen, who were attached to Washington’s cavalry to form a legion similar to Lee’s.

Greene now had 4,400 effectives that he could count on to do battle with Cornwallis. The latter’s intelligence, to Greene’s undoubted advantage, had succeeded in magnifying the American numbers to 9,000 or 10,000. If Cornwallis believed the figures, and there is no evidence that he did not, he was undismayed. His 1,900 regulars were all of them seasoned veterans, who doubtless would prove to be worth more than twice their number in battle with American militia.

Greene had drawn his opponent northward, stretching Cornwallis’s supply lines to the breaking point. If he did not strike before the enemy was reinforced, his strength would dwindle away once the militia had served out their six-week commitment. Moreover, both he and his enemy had stripped the area of food and forage, and neither force could sustain itself in the region for more than a few days. Greene knew that his enemy, just recently moved to New Garden a few miles away, would not refuse the challenge to fight a pitched battle once the Americans had taken up a fixed position.

No doubt Greene had in mind just the locale that would favor his battle. He had studied the terrain when he had first stopped at Guilford Courthouse, when his council of war had talked him out of fighting. Now there was no need for a council. Greene moved on 14 March to take up a defensive position at Guilford Courthouse.

IT HAS BEEN COMMONLY ACCEPTED THAT Greene deployed his army for battle using the same tactics that had worked so brilliantly for Morgan at Cowpens. The point, I think, has been very much overstated. It is true that Morgan advised Greene, in a letter dated 20 February, in regard to deploying his forces when confronting Cornwallis in battle, but there is no evidence to show that Greene unthinkingly adopted Morgan’s every suggestion, even though his three-line-deep deployment might appear on the surface to be a carbon copy of Morgan’s. The terrain on which Greene made his dispositions was markedly different in character from Cowpens. Morgan had been successful in South Carolina because he fitted his firepower to the terrain in such a manner that he could observe and control his troops throughout the action. The terrain of Cowpens, with its excellent all-around fields of fire, allowed Morgan to do just that.

The terrain at Guilford Courthouse denied Greene any such freedom of action. Its most striking feature was the dense forest that dominated the area, with the exception of the few clearings that offered fields of fire, usually limited to the immediate front. If the Americans were to adopt Morgan’s three-line deployment, the terrain dictated that there could be no mutual support between the lines. Nor could the commander or his senior leaders even see the first two lines, because the troops would be out of sight in the woods.

For all that, Greene proceeded to deploy as indicated on the map. The road from Guilford Courthouse to New Garden bisected the positions of the two forward lines. The front line was composed of the two North Carolina militia brigades of 500 men each: Butler’s on the right of the road, Eaton’s on the left. The right flank of the line was covered by Washington’s legion, with his cavalry on the extreme right. His infantry, composed of Kirkwood’s light infantry company and Lynch’s Virginia riflemen, was formed in a line that was angled inward in order to provide enfilading fires against the attacker. On the left flank Lee’s legion was deployed in the same manner as Washington’s. The cavalry covered the end of the flank, with the legion infantry and Campbell’s riflemen formed in line facing obliquely to enfilade the main line from their position. Captain Anthony Singleton, with two of Greene’s four six-pounder guns, was in the center, with his guns positioned on the road and laid to fire across the clearings to their front.

The second line, about 300 yards behind the first, comprised the two Virginia militia brigades of 600 men each: Stevens’s on the right of the road, Lawson’s on the left. The second line was deployed entirely in the woods, with connecting files posted in the rear to facilitate contact with the third line.

Greene’s main line of resistance was his third line, 550 yards to the right rear of the second line. In order to take advantage of the high ground west of the courthouse, this line had to be displaced westward, with only about half of it directly in the rear of Stevens’s brigade. Two brigades of Continentals made up the line. On the right was Huger’s brigade of Virginia Continentals, 778 men: Colonel Green’s 4th Virginia on the brigade’s right, and Hawes’s 5th Virginia on its left. The other brigade was the Maryland Continentals, 630 men under Otho Williams: Gunby’s 1st Maryland on the brigade’s right, and Ford’s 5th Maryland on the left. Captain Samuel Finley’s two six-pounders, the other half of Greene’s artillery, were positioned in the center, in the interval between the two brigades. Greene remained with the Continentals throughout the battle.

Along with the terrain and the disposition of the troops, several other factors are noteworthy. Greene had put his entire army in the three lines. There was no provision for an army reserve of any kind, whereas the terrain of Cowpens had permitted Morgan to hold all of his cavalry in reserve. The question of Greene’s lack of a reserve has been well addressed by Boatner: “It would appear that he should have been able, however, to set himself up a general reserve, either from the flanking units of his first line, or by eliminating the second line and using these flanking units as a delaying force between the first and last lines” (Encyclopedia of the American Revolution).

The quality of Greene’s troops was decidedly uneven. At opposite ends of the spectrum were the battle-hardened veterans such as Kirkwood’s Delaware company and Gunby’s 1st Maryland Continentals; on the other end was the North Carolina militia, which could not be depended upon at all to stand up to British bayonets. Two units, the 5th Maryland and some of the Virginia Continentals, were getting their first taste of combat.

Greene was well aware that his front line, much like Morgan’s second-line militia at Cowpens, would vacate the premises shortly after the shooting started. That is why he walked the line of his North Carolina militia, exhorting them as best he could and reminding them of his basic instruction: Get off at least “two rounds, my boys, and then you may fall back.” In that exhortation lay another case of the difference in the terrain of Morgan’s and Greene’s battles. Morgan’s militia could file off around the left of the Continental line behind them and reform to reconstitute a reserve. Greene’s militia had no place to go except the woods around and behind them, so when they “fell back” they would vanish off the earth, as far as their further participation in the battle was concerned. Consequently, the only recourse left to Greene was to order, ahead of time, the Virginians in the second line to open their ranks and let the Carolinians pass through. He also made sure that Washington’s and Lee’s flanking units knew that they should fall back and take up positions on the flanks of the second line.

His instructions given and his inspections made, Greene rode back to his command post behind the third line. The morning was clear and cold under a cloudless sky. It only remained now to sit tight and await Cornwallis’s advance.

TWELVE MILES TO THE SOUTHWEST, Cornwallis, in his camp at New Garden, had begun his preparations to advance on 14 March. Late in the day he sent his sick and wounded, in the wagons that remained to him, back to Bell’s Mills on Deep River under a small escort of infantry and cavalry. Then, in the hope of catching Greene off guard, the earl had his troops fall in and start the twelve-mile march to Guilford at 5:00 A.M., without taking time for breakfast. The main body was preceded by an advance guard under Tarleton of about 450 men: his legion cavalry and infantry (272), 84 jägers, and some 100 light infantry of the guards.

About 7:15 A.M., seven miles down the road, Tarleton’s dragoons were fired on by a detachment of Lee’s legion. Greene had sent Lee, with the infantry and horse of his legion reinforced by Campbell’s riflemen, as a covering force, and it was Lieutenant Heard’s squad of the legion cavalry that had fired on the British. When Heard galloped back to inform Lee of the British approach, Lee pulled back, looking for an advantageous place to delay his enemy, and Tarleton pressed forward.

Lee found the spot he was looking for, “a long lane with high curved fences on either side of the road.” He waited until Tarleton’s dragoons poured into it, then ordered a charge that resulted in the whole of the enemy’s advance being dismounted, and many of the horses downed. Some of the British dragoons were killed and the rest made prisoner; not a single American soldier or horse was injured. Tarleton thereupon retired, and Lee’s horsemen pursued until they ran into the infantry of the enemy’s advance guard near New Garden Meetinghouse. The British infantry deployed and fired on the American cavalry, driving them back, Lee being momentarily unhorsed during the confusion. Lee’s infantry came up, and a smart little skirmish ensued in which Tarleton lost about thirty killed or wounded. Lee claimed much lighter losses. Tarleton took a musket ball in his right hand, causing him to lose his middle and index fingers.

Lee then withdrew his force and fell back toward the American defensive position. There were more exchanges of fire, which by then could be heard by Greene’s troops three miles away. Finally, when the skirmishing grew to a firefight, Lee could see that he had checked the British advance long enough. He withdrew again and warned Greene of the approach of the enemy’s main force. Lee’s men closed into their positions in the first defensive line not long before noon.

WHEN CORNWALLIS RODE UP THE NEW GARDEN ROAD and came Up the low rise on the south side of Little Horsepen Creek, he was able to observe the ground in front of the American position. Before him the road sloped downward to the creek, a small stream beyond which the terrain began to rise. There were open fields on each side, but at the top of the rise the road entered a dense wood, and in front of it, behind rail fences, the North Carolina militia waited. In order to get at them, Cornwallis’s troops would have to advance for some 500 to 600 yards uphill across a quarter-mile-wide expanse of muddy fields, exposed all the while to enemy fire.

The leading troops of the British main body emerged from the north end of the defile above Little Horsepen Creek and began deploying from column into line. Cornwallis had divided his attack force into two “wings” (provisional brigades). The right wing, under Major General Leslie, had on its right the Hessian Regiment von Bose, and on the left the 71st (Eraser’s) Highlanders. The left wing, under Lieutenant Colonel Webster, had on its right, lining up with the 71st Highlanders, the 23rd Regiment of Royal Fusiliers, and on its left the 33rd Regiment. Unlike Greene, the British commander had retained a strong reserve. The 1st Guards Battalion was behind General Leslie’s wing. Behind Webster’s wing were the jägers, the 2nd Guards Battalion, and the grenadier and light infantry companies. Also in reserve was Tarleton’s cavalry, held back in column, to the rear on the New Garden Road. The reserve was commanded by General O’Hara. The Royal Artillery detachment, three three-pounders under Lieutenant MacLeod, would first occupy positions in the center along the road.

LOOKING SOUTHWARD ACROSS THE STUBBLE FIELDS, the North Carolina militiamen were no doubt impressed by the display, as intended, of the British forming into line of battle. Companies came up from the defile in compact columns, turned at right angles to the road, and wheeled smartly into long scarlet lines. Polished musket barrels glittered in the noonday sun, while the roll of the drums and the keening of the fifes were carried to the Americans in the clear March air.

When the first body of British infantry came within range, Captain Singleton opened up with his two six-pounders. Within minutes Lieutenant MacLeod’s Royal Artillery guns were answering the American fire. The cannonade lasted for less than half an hour, with negligible effect on either side. About 1:30 P.M. the British attack came on, straight ahead across the quarter mile of open fields. When the first British ranks were within about 150 yards, the thousand muskets and rifles of the Americans opened fire. It was not a crashing volley like the Continentals would have delivered; instead it was a rolling fire, at too great a range for maximum effect. Nevertheless, gaps were opened in the red-coated line, which continued to come on steadily. When the British line came within its own musket range, it snapped to a halt and fired its first volley. At Colonel Webster’s command, his lines advanced with muskets lowered at charge bayonet. About 40 yards from the rail fence the advance came to an abrupt halt. British Sergeant Lamb, of the 23rd Regiment (Royal Welsh Fusiliers), recounted in his journal that “their whole force had their arms presented and resting on a rail fence . . . they were taking aim with nice precision. . . . At this awful period a general pause took place; both parties surveyed each other for a moment with the most awful suspense. Colonel Webster then rode forward in front of the 23rd Regiment and said, with more than his usual commanding voice . . . ‘Come on, my brave Fusiliers.’ These words operated like an inspiring voice. Dreadful was the havoc on both sides. At last the Americans gave way.”

With the exception of the flank units of Lee and Washington, the American line broke across its whole length. The militia, having delivered its fires per Greene’s instructions, turned and fled, disappearing into the woods. According to Lee, “Every effort was made by the Generals Butler and Eaton . . . with many officers of every grade to stop this unaccountable panic for not a man of the corps had been killed or even wounded.” (It appears that Lee was unaware of Greene’s permission for the Carolinians to leave the field.) At this point there appears to have been a great deal of difference between Lee’s observations and Sergeant Lamb’s picture of dreadful havoc in front of and behind the rail fence. Lee goes on to say that he “joined in the attempt to rally the fugitives, threatening to fall upon them with his cavalry. All was vain, so thoroughly confounded were these unhappy men, that throwing away arms, knapsacks, and even canteens, they rushed like a torrent headlong through the woods” (Memoirs).

The action in the first American line was not over when the militia had taken off into the woods. Although Webster’s and Leslie’s line had reached the fences on the north end of the clearings, both the British and Hessian regiments were suffering severe casualties from enfilading fire on both flanks. On the British left the deadly fire was coming from Kirkwood’s Delaware company and Lynch’s riflemen; on the right the same deadly fire was being thrown at them by Campbell’s riflemen and Lee’s legion infantry. Before the British could advance upon the line of Virginians waiting 300 yards back in the woods, these twin threats would have to be dealt with.

The problem was handled on the British left when Webster directed the 33rd Regiment to divert its attack obliquely against Kirkwood and Lynch, while jägers and light infantry available on the left were brought up to augment the 33rd. At the same time General Leslie, in similar fashion, swung the Regiment von Bose and the 71st to face Campbell’s and Lee’s units. These maneuvers on both flanks of the British line left a wide gap in the center, which O’Hara plugged by bringing up the 2nd Guard Battalion and the grenadiers. The line was also extended in Leslie’s wing by advancing the 1st Guard Battalion to the extreme right.

When the British attack was resumed, the first heavy fighting took place on the flanks. Washington, on the American right, kept Kirkwood’s and Lynch’s infantry forward as long as he could, but soon they were thrown back by the weight of the British 33rd, reinforced by the light infantry and jägers. Seeing that his infantry’s position was becoming untenable, Washington covered their withdrawal with his cavalry until Kirkwood and Lynch could take up new positions on the right of the second line.

On the American left, things took a different turn. Although Lee’s infantry had been augmented by Captain Forbes’s company of North Carolina militia, which had stayed to fight on, Campbell’s riflemen were assailed by the British 1st Guard Battalion. This action, along with a coordinated attack by the Regiment von Bose, prevented Lee from falling back to the second line, as Washington had done on the other flank. As Lee was driven back, he found his infantry being pushed farther and farther toward the left, separating them completely from the American main body. Lee’s force thus had to fight its own separate battle, engaged continuously with the guards and von Bose. This private affair was to be continued throughout the battle, with the result that both Cornwallis and Greene were deprived of troops that were sorely needed in the main actions.

The British now advanced through the woods to attack the American line, only to find that the real battle had just begun. No longer could the redcoats advance in firm lines and deliver controlled volleys against their enemy. That enemy was now shielded by trees and undergrowth that broke up the battle into a series of small-unit actions. Stedman, who was at the battle, reported that the Americans were “posted in the woods and covering themselves with trees, [from which] they kept up for a considerable time a galling fire, which did great execution.” All across the second line the Virginians, fighting to hold their positions, were beginning to feel the whole force of Cornwallis’s attack. The heavier weight of Webster’s and O’Hara’s troops was thrown against Stevens’s brigade on the American right: the 33rd, the grenadiers, the guards’ 2nd Battalion, the jägers, the light infantry were all directing their main effort against Stevens. The pressure was too much, and the brigade was forced back on its right. Like the opening of a huge door, the left of the brigade held like the hinges while its right was swung back, until it finally broke. The rest of the Virginia line fought on stubbornly, fighting off three bayonet attacks and holding up for a time the advance of the 23rd, the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and the 71st.

While the British 23rd and 71st Highlanders were being held up by the left of the American line, Colonel Webster took stock of the situation. With the driving off of the American right, the way was open to him to continue the advance and attack Greene’s third line. He led forward the 33rd Regiment, the light infantry, and the jägers. Emerging from the woods, they came up against the best of Greene’s troops, the Continentals of the 1st Maryland and the 5th Virginia, supported by Captain Finley’s two six-pounders. Waiting along the forward slope of the high ground south of the Reedy Fork Road, the Continentals had been listening to the growing sounds of battle in the woods ahead: the banging of muskets and the crack of rifles swelled to a continuous roll. As the firing below them seemed to diminish, they began to see little groups of Virginians trotting out of the woods headed toward the rear. Then the groups grew to a steady stream, and the Continentals could be sure that the second line had broken. Over on the right, two columns were coming back, one in Continental uniforms, the other, larger column in brown hunting shirts and gray homespun. They were Kirkwood’s Delaware Continentals and Lynch’s Virginia riflemen, filing back to fall in on the right of Colonel Green’s 4th Virginia.

In a few minutes groups of redcoats appeared on the near edge of the woods and began to form into line. Then the British line came on, led by Webster: on the right the 33rd was headed directly toward the 1st Maryland; on the left the light infantry and jägers were coming on toward Hawes’s 5th Virginia. The Continentals stood, rock-firm, awaiting the command to fire. Their officers held back until the British line was within thirty paces, then the command came: “Fire!” The volley crashed into the red-coated formations, which disintegrated under the blow. Falling back in disorder, the British infantry left a swathe of dead and wounded. But the Continentals were not through. Colonel John Gunby of the 1st Maryland called for a bayonet attack. The Maryland and Virginia regulars slashed through the knots of their disorganized enemy and drove the fugitives down into a ravine and up its other side. With that the British fled into the woods. Webster was carried back with them, his knee shattered by a musket ball.

Now victory seemed held in balance for either side. On the British far right the guards and Hessians were out of the main battle, held up by Lee’s men on a wooded height far to the south. In the center, the left of the American second line was still entangled with the British 23rd and 71st regiments. And the center of the third line had just repulsed and shattered Webster’s too-bold attack.

Accordingly, at this critical moment, historical “what ifs” begin to pop up: What if Greene had thrown his cavalry against the disorganized British? What if Greene had attacked the British center with the whole of his Continental line? Yet Greene could not have known that a critical moment had arrived, for the simple reason that he could not see the battlefield that involved his first and second lines, nor Lee’s separate, faraway battle. Also, Greene had no reserve to commit, and in any event he would not have thrown his third line into the fray, because he had entered into this battle—indeed into the whole campaign after Cowpens—with the firm resolve not to risk the hard core of his army in any way that might hazard its destruction. The loss of his veterans, he was certain, would surely leave the South in British hands.

WHILE WEBSTER WAS MOVING THROUGH THE WOODS and delivering his disastrous attack against Greene’s third line, the resistance of the Virginians in the second line was weakening. When General Leslie became aware of the fact, he disengaged the 23rd and 71st regiments and sent them to take part in the attack against the American third line. During the lull that followed, Cornwallis was restoring his forward line to launch his main attack against Greene’s Continentals. As part of this reorganization of force, General O’Hara, who had been wounded, turned over command of the 2nd Guard Battalion and the grenadiers to Lieutenant Colonel James Stuart. That officer didn’t wait for the other three units—the 23rd, 71st, and grenadiers—to come up into line. He led the 2nd Guards, “glowing with impatience to signalize themselves,” toward that part of the American line to their front, Ford’s 5th Maryland Continentals and Captain Singleton’s two six-pounders.

The 5th Maryland was not made of the stuff that had enabled Continentals to stand and exchange volleys with British regulars. Mostly recruits in a newly reorganized unit that was facing battle for the first time, the raw Marylanders gaped at the hedge of British steel coming up the hill directly at them. They got off a ragged volley, and to a man turned and ran. The guards dashed ahead and seized Singleton’s two guns. Then, as Stuart continued to drive on through the penetration his guards had made, his battalion was struck on both flanks by two charging counterattacks, both made on the initiative of local commanders. The close-in combat that followed was out of Greene’s control; he was already considering saving his invaluable Continentals, having observed that it would soon be “most advisable to order a retreat,” and had ordered Colonel Green to pull back his 4th Virginia to cover a general disengagement.

William Washington, observing from the American left on the hill, saw the 5th Maryland collapse and the subsequent British breakthrough. Seizing the chance to restore the situation, he led his entire cavalry force in a pell-mell charge that smashed into the right rear of Stuart’s guards, sabering right and left as they broke through the British formation. Among Washington’s troopers was the famed Sergeant Peter Francisco, a six-foot-eight giant who wielded an awesome five-foot sword said to have been given him by General Washington. It was said, too, that he had the reputation of being the strongest man in Virginia. According to his comrades, Francisco cut down eleven British soldiers “with his brawny arms and terrible broadsword.” Not only did Francisco ride through the guards, he wheeled around and went back through them, sabering as he went.

In the meantime Colonel Gunby, having returned the 1st Maryland to its original position, was informed by his second in command, Lieutenant Colonel John Eager Howard, that the guards had broken through the 5th Maryland and were pushing on through the breached American line. At once Gunby wheeled the 1st Maryland and charged into the guards; when the Americans continued to drive into the British, the encounter turned into a melee. During the hand-to-hand fighting that followed, Stuart himself was killed, cut down by a sword blow from Captain Smith of the Marylanders when he and the British leader engaged in personal combat. In Franklin and Mary Wickwire’s account of the close combat:

Even the Guards’ experience and discipline could not forever stand proof against such an onslaught. They had plainly begun to get the worst of it and had begun to fall back when Cornwallis . . . resorted to a desperate measure . . . Lieutenant MacLeod had brought two 3-pounders along the road to a small eminence just beside it on the south side . . . Cornwallis ordered MacLeod to load his guns with grapeshot and direct his fire into the middle of the human melange. O’Hara who lay bleeding nearby in the road, supposedly ‘demonstrated and begged’ his commander to spare the Guards, but Cornwallis repeated the order. . . . The carnage upon friend and foe alike was frightening, but it did serve the purpose. When the smoke cleared away, the surviving Guards had regained the safety of their own guns [lines?] and those of Washington’s and Howard’s men [Howard having relieved Gunby when the latter was pinned down by his wounded horse] who could still move had abandoned their pursuit and retired to their own lines. (Cornwallis: The American Adventure)

With both sides retiring, there was a new lull in the action during which Cornwallis again restored his front line, this time in preparation for a final assault by the 23rd and 71st regiments. Webster had reorganized his former attacking force, and returned to renew the attack against the American right.

Greene was now faced with a restored British line which was about to launch an all-out attack. At 3:30 P.M. he decided on a general retreat. The only fighting units left intact to confront the enemy were the 1st Maryland, Hawes’s 5th Virginia, and Washington’s cavalry; the 4th Virginia had already been pulled back to aid in covering the retreat. Howard retired the 1st Maryland in good order, while Washington and Green’s 4th Virginia got in position to cover the withdrawal. On the left, Hawes’s 5th Virginia repulsed Webster’s new attack with enough volleys to end the battle.

The retreat was “conducted with order and regularity,” even though Greene’s four guns all had to be abandoned because most of the artillery horses had been killed. For a short time Cornwallis pushed a pursuit, using the 23rd, the 71st, and a part of Tarleton’s cavalry, but those worn-out men were too fatigued to be effective and the earl had to call it off.

Greene’s retreating force moved out in a driving rain and crossed Reedy Fork, about three miles west of Guilford Courthouse, where he halted long enough to close up his column and collect stragglers. He then pushed on, making an all-night march to his former camp at the Ironworks on Troublesome Creek.

As for Lee’s semi-independent battle, he and Campbell had fought the Hessians and the 1st Guards through the woods and over hills, trying to hold their enemy while maneuvering to get back to Greene’s third line. When Lieutenant Colonel Norton, commanding the 1st Guards, disengaged to take his battalion and link up with the 71st, Lee and Campbell seized the opportunity to force the Hessians back. Lee then left Campbell to hold the enemy while he took his infantry back to rejoin his legion cavalry near the courthouse. A charge by Tarleton’s cavalry finally released the pressure on the Hessians, and with that Campbell got his men clear and away.

GUILFORD COURTHOUSE PROVED TO BE ONE OF the bloodiest battles of the war, and most of the blood that was shed was British. Greene’s casualty count was 78 killed and 183 wounded out of a force of 4,444. Out of a force of 1,900, Cornwallis lost 532 officers and men, 93 of whom were killed and 50 dead of wounds before they could be evacuated. The guards took the heaviest casualties: 11 of 19 officers and 206 of 462 men.

Shortly after Greene had broken off the battle, a continuing rain set in. It was an unusually black night, and it was still cold there in late winter. The search for the British wounded had to go on all night over a large area, much of it wooded. The last time Cornwallis’s soldiers had eaten was at supper on the evening of 14 March. They then had been forced to march twelve miles the next day, fight one of the fiercest battles of the war, and sink down on wet ground that night, hungry and without tents. After forty-eight hours they were finally rewarded with a repast of four ounces of flour and four ounces of lean beef.

Cornwallis had won the battle, but he had lost his campaign. Greene had withdrawn intact, and as events were to show conclusively, his fighting force would be capable of moving and fighting almost anywhere in the Carolinas. Cornwallis could not. As Page Smith observed: “For Cornwallis, the possession of the Guilford Courthouse battlefield had no meaning if Greene’s army survived to fight another day.” After the battle had been fought, it was impossible for the British general to resume his pursuit of Greene. In Smith’s words, “His shattered army could not sustain another battle. Instead of following Greene he issued a proclamation, claiming a glorious victory for British arms and urging all loyalists to come to his support. Then he turned toward Wilmington, North Carolina, the country of the Scottish Highlanders, where he hoped to rest and equip his battered army” (A New Age Now Begins).