4

ENDINGS

THE ONLY WAY THAT LADY DEDLOCK CAN ESCAPE FROM THE lord of the underworld who controls her secret is to renounce secrecy altogether. To do so is to cast off her identity as grand lady, the frozen mask of boredom that has imprisoned her in a state of deadlock and kept her from living or loving. Paradoxically, the first real act of love that she performs is a repetition of her greatest crime, the rejection of a daughter. When she turns Rosa away from Chesney Wold, however, it is not out of indifference or shame, but to save the girl and allow her to have a future of happiness with the man she loves. Renouncing secrecy also means leaving Sir Leicester, but in stripping herself of his jewels and relinquishing her watch, and in exchanging clothes with “the mother of the dead child,” Lady Dedlock is embracing the painful but more authentic identity that she has tried so long to escape. Changing clothes with Jenny also means becoming homeless; it means accepting her place as, in Guster's words, “a common-looking person, all wet and muddy” (911).

One measure of the extent to which Lady Dedlock has renounced her former identity and embraced “common” humanity is her interaction with the Snagsbys' serving girl. Because she does not know how to find the burial ground on her own, she must ask for directions, as she did once before of Jo. Guster tells her how to find the graveyard and agrees to take the letter that she leaves for Esther. “And so I took it from her,” Guster says, “and she said she had nothing to give me, and I said I was poor myself and consequently wanted nothing. And so she said God bless you! And went” (912). In her earlier visit to the graveyard, Lady Dedlock had paid her guide, but never thanked him—vanishing without speaking and leaving behind only the useless gold sovereign that Jo is never able to spend and that brings him more trouble than good. Here, with Guster, she abandons the cash nexus system and enters instead into the economy of the gift, the economy of the poor, who have nothing and want nothing. The blessing that she leaves for Guster repeats and corrects in a finer tone her earlier arrogant and thankless treatment of Jo.

Renouncing the regime of secrecy also means that Lady Dedlock must die—of cold, wet, and fatigue, but also, as she tells Esther in her final letter, “of terror and my conscience” (910). She is terrified, no longer of Tulkinghorn, of whose murder she learns from Mrs. Rouncewell, but of the social disgrace and shame that await her if she attempts to continue a life as Lady Dedlock. She is conscience-stricken over the effects that she fears scandal will have on Sir Leicester, but also, and more profoundly, at the knowledge of what she has done to Esther. Nevertheless, in death, or rather in dying, she has become more alive than at any other time when we observe her, and her final words, “Farewell. Forgive,” may be the most authentic she has ever produced.

For Esther, the end of chapter 59 is not an ending; it is a beginning, the beginning of a new life. But what are we to make of the life that she reports living? And how successful has her homely Orpheus been in bringing her back from the underworld? How successful was her “psychoanalysis”? To answer these questions, we must look closely at the six chapters that Esther narrates in the novel's final double monthly number, and we must attend more carefully than ever to the voice of Esther Woodcourt.

In posing these questions and trying to answer them, I am returning to the point in chapter 1 where I began and to two questions that I left dangling in my initial discussion of Esther's discovery of her mother's body: what does this scene leave out? and what does it do for Esther in her role as narrator?

What the scene leaves out—what Esther leaves out—is any description of her reaction, then or now, to the discovery of her mother's body. When we turn to the beginning of chapter 60, we read,

I proceed to other passages of my narrative. From the goodness of all about me, I derived such consolation as I can never think of unmoved. I have already said so much of myself, and so much still remains, that I will not dwell upon my sorrow. I had an illness, but it was not a long one; and I would avoid even this mention of it, if I could quite keep down the recollection of their sympathy.

I proceed to other passages of my narrative. (916)

I suspect that any even moderately curious reader will want to know more than Esther tells us here, both about her illness and the process of her recovery, and about the effect on her current and ongoing sense of who she is of all the new information and experience she has accumulated. Yet she describes no dreams, as she did after her previous illness, and she never again refers directly to her mother in any of the six remaining chapters that she narrates, other than to mention in passing that on one occasion when she sat with Jarndyce (but before he reveals his plan for her to marry Woodcourt) she wore “my mourning dress” (920).

By this point, readers familiar with Esther's habit of narrative indirection may be expecting that whenever she witnesses (and reexperiences) a traumatic “primal” scene such as the one at the end of chapter 59, she will displace her reaction onto a nearby figure in her narrative. Yet no convenient surrogate appears in chapters 59 or 60 to act out or give voice to her hidden feelings. Ada has her own life by now and no longer seems available for the role of doll, and Hortense has been safely spirited away by the “homely Jupiter,” Inspector Bucket.

In order to find the displaced voice that fills the gap between chapters 59 and 60, we must look elsewhere in the novel, back to a scene near the very beginning of Esther's narrative in chapter 3. There Esther writes of an occasion when she had been reading aloud to Miss Barbary from the Bible and was suddenly interrupted by a loud cry.

I was stopped by my godmother's rising, putting her hand to her head, and crying out, in an awful voice, from quite another part of the book:

“Watch ye therefore! lest coming suddenly he find you sleeping. And what I say unto you, I say unto all, Watch!”

In an instant, while she stood before me repeating these words, she fell down on the floor. I had no need to cry out; her voice had sounded through the house, and been heard in the street.

She was laid upon her bed. For more than a week she lay there, little altered outwardly; with her old handsome resolute frown that I so well knew, carved upon her face. Many and many a time, in the day and in the night, with my head upon the pillow by her that my whispers might be plainer to her, I kissed her, thanked her, prayed for her, asked her for her blessing and forgiveness, entreated her to give me the least sign that she knew or heard me. No, no, no. Her face was immovable. To the very last, and even afterwards, her frown remained unsoftened. (32–33)

The reader who encounters this passage for the first time or who persists in reading it only as the description of an event from Esther's childhood will be discomforted, I suspect, both by the outpouring of grief it contains and by Esther's apparent attachment to the source of her early emotional abuse. The reader who comes back to this passage after having completed the novel and who keeps in mind Esther's position as retrospective narrator will find it easier to recognize in the excess of emotion here a transference, in the moment of writing, of Esther's feelings about her mother's death in chapter 59 onto the figure of the godmother. More than just the description of an event from Esther's past, the passage is itself an event in the present time of narrating. Or, to put it slightly differently, the act of enunciation—voice as registered in the sju et—erupts into and inflects the utterance—the énoncé.

et—erupts into and inflects the utterance—the énoncé.

What authorizes and confirms this reading for me is the phrase that Esther uses to describe her godmother's sudden cry. She calls it “an awful voice, from quite another part of the book.”1 The “book” here is both the godmother's Bible and the book we are reading. Just as there are two books, so there are two different awful cries. One comes from the godmother, the other from the narrator. The second awful cry, with its despairing “No, no, no,” belongs to Esther, and it comes from somewhere between the end of chapter 59 and the start of chapter 60. It is Esther's anguished response to her mother's death, both at the time of the event and now in the time of writing and reexperiencing it. Once again, the shift from past- into present-tense narration is a clue to the repetitive dimension of this scene as well as to its persistence “now” in the mind of Esther Woodcourt. The cry “No, no, no” has no fixed temporality. The phrase “Many and many a time, in the day and in the night” signals the recursive pattern of trauma. The immovable face, the unsoftened frown, belong both to the godmother and to Lady Dedlock, and they remain “to the very last, and even afterwards” (my emphasis). Esther Woodcourt is still haunted by the death of her mother. Seven years afterwards, she is still in mourning, or rather, she is still afflicted with what Freud calls melancholy.

Has Esther's “psychoanalysis” with Bucket been successful? Has the homely Orpheus successfully brought her back from the underworld? I think not. Or if he has done so in part, he has not entirely succeeded in liberating her from the ghosts of her past. Esther marries Allan Woodcourt, the man she loves, and she becomes a mother. These are undeniable signs of greater emotional strength, as is her ability to confront and reprimand Skimpole “in the gentlest words I could use” for his “disregard of several moral obligations” (933). The marriage to Woodcourt has troubled many readers, who find it sentimental and a concession, on Dickens's part, to the demands of his audience and the conventions of the marriage plot. I too find it troubling, but for other reasons.

The marriage to Woodcourt, as other critics have pointed out, is an arranged affair. Jarndyce, having abandoned his own tepid and slightly incestuous love for Esther, arrogates to himself the role of author, turns his heroine over to a worthy, if slightly wooden, surrogate of whom he approves, and sets them up in a doll's house that is the exact replica, down to its very name, of his own Bleak House. Is Esther happy with this arrangement? Yes, of course, but there is still something more than just a little artificial about the happy ending thus effected. There is too much contrivance here. The ending feels imposed rather than achieved, and this, I believe, is the reason many readers have been less than fully satisfied by it.2 It feels more like the simulacrum of a happy ending, almost a parody, rather than the real thing, just as the second Bleak House is a simulacrum of the first rather than a genuine new home. But whom should we hold responsible for whatever is unsatisfactory in this ending? The conventional answer has been “Dickens” or “Victorian morality” or something similar. But why not lay the blame on Jarndyce and his sentimental, self-indulgent philanthropy? After all, the book never whole-heartedly endorses his generosity, which, as his indulgence of Skimpole shows, contains a large dose of self-deception. Perhaps Skimpole is right when, in his posthumous autobiography, he writes that “Jarndyce, in common with most other men I have known, is the Incarnation of Selfishness” (935).

What is most notably missing in the happy ending is any agency on Esther's part. She becomes a character in someone else's plot, not a plot of her own making. To the extent that she has significant agency in the final sections of the novel, it is her agency as narrator. Whatever her passive role in the marriage plot arranged for her, she remains the active producer not only of six final chapters but also of her retrospective narrative, written, we must remember, entirely after her marriage to Allan and addressed, not to him or to anyone she knows, but to the “unknown friend.”

To answer the question of whether Esther's “psychoanalysis” has been successful, then, we must look not so much at the story she reports, the fabula, as at her narrative discourse and at the voice that she uses as narrator in order to tell that story. Again we are back to Esther Woodcourt. In the reading that I give to it, Esther's narrative is a marvelous ghost story. It is a narrative full of contradictory impulses, containing passages of brilliant, powerful, hallucinatory prose, equal to the best that any Victorian novelist (even Dickens!) could produce, but also replete with coy evasions, sentimental self-indulgence, and a studied, almost masochistic desire to hide her beauty, sexuality, and creativity from the view of others and from herself. To the extent that generations of readers have found her “unlikable” as a narrator, she has succeeded in this effort at concealment. My task in reading her otherwise has been to bring out the darker, more powerful and conflicted side of Esther's character and to locate the sources both of her strengths and of her neuroses, the two being closely connected. Esther's struggle to give voice to her inner conflicts and to report on her descent into dark, terrifying regions of her psyche is heroic and deserves more respect than critics have generally been willing to accord it. Esther is fully the equal in this regard of Jane Eyre, Lucy Snowe, or Catherine Earnshaw, and Bleak House deserves recognition as one of the great achievements in the tradition of the female gothic.

Critics have generally not been willing to listen to Esther's voice or else have listened to only one of her voices, the domestic, preferring, even when they do not acknowledge it openly, the other, more properly “Dickensian” narrator, the one who sets the fog machine going, the Megalosaurus waddling, the giant soot flakes falling, and who seems more directly engaged with social issues, condemning the inefficiency of Chancery and the neglect of the poor. Critics who take a more “political” approach to the novel tend to align Esther with dominant ideological structures and to see her marriage to Woodcourt as the conventional sign of narrative and ideological closure. Even those critics who find a satirical edge in Esther's accounts of the Jellyby, Pardiggle, and Turveydrop establishments and who see in her marriage to Allan an effort on Dickens's part to locate the happy couple outside the British class system (see, for example, Vanden Bossche) have difficulty following Esther into the depths of her nightmares or drawing connections between the novel's political and “psychological” plots. Still other critics, many of them attentive to feminist issues, see Esther as bravely struggling with Victorian gender ideologies and succeeding, more or less well, in establishing a precarious daughterly independence within patriarchal society (see, for example, Schor and Sternlieb) or else as achieving “healthy self love” through the exercise of her “will to live, to love and be loved, to want and then to have.”3 Yet these critics too tend to focus on the plot, on Esther's place in society, at the expense of her role as narrator, her place within language.

All of these views have merit, but none goes far enough, I believe, in accounting either for the depth of psychic pain that Esther confronts or for the residue of this pain in her retrospective narrative, as manifested in its weird temporality and dislocated voices. “My” Esther (and I believe Dever's as well) is more of a ghostwalker and a ghostwriter than other critics have allowed. She is also, as I hope to show in my final chapter, more closely connected than critics have generally suspected to the book's largest social, political, and historical concerns.

I have argued that in chapters 57 and 59 Esther undergoes a form of “psychoanalysis” with Bucket as her analyst and that he functions as the Orpheus who leads her back toward the land of the living where she can recover her identity as the beautiful queen Esther. I have also suggested that Bucket's therapeutic intervention is at best only a partial success. Like Eurydice, Esther sinks back into the underworld, not through any fault of Bucket (he does not “look back”), but because she is unable to get beyond the horrifying recognition, after looking into her mother's dead face, that she too is dead. The “failure” of her analysis with Bucket is most immediately evident in the flat affect and dead narrative voice of the opening of chapter 60: “I proceed to other passages of my narrative.” Having come all the way back “up” to the burial ground, Esther can go no farther. She remains in mourning, for herself as well as for her mother, and she continues to lead her life and write her story under a cloud of melancholy, no matter how “happy” she forces herself to be.

Patients who experience “failure” in their analysis or who reach an impasse with their first analyst sometimes undertake a second course of treatment. Seven years into her marriage and after giving birth to two daughters, Esther Woodcourt returns to “psychoanalysis.” Her second analysis is conducted under even more unorthodox conditions than the first, not in the closed carriage with Bucket at her side (recalling the physician's consulting room or the mesmerist's closet, two nineteenth-century analogs to the psychoanalyst's office). Instead, Esther undertakes analysis on her own, or if not entirely alone, then in the presence of an “unknown friend” to whom her narrative, we learn at the very end, is addressed. Her “second analysis” repeats some of the same ground as her first, but is more detailed and goes back much farther into the past, beginning in childhood and coming up to the very present. Esther's “second analysis” is her written life, the text that we read and reread together with her.

Who is this “unknown friend”? By definition, it is not Ada or Caddy or Jarndyce or Allan, since all of these are people known to her. Among the various possibilities, one is ourselves—that is, the reader of Bleak House, who if properly sympathetic and attuned to Esther (Esther Woodcourt, I mean), may provide her with the understanding and compassion she needs and deserves. Another possibility, one that I have already mentioned, is Esther's mother. If we look closely at the way in which she refers to the “unknown friend,” is there not a hint that in writing the story of her life Esther may be reaching out toward the mother who still remains “unknown” to her, but whom she remembers fondly and by whom she hopes to be remembered in turn? “The few words that I have to add to what I have written, are soon penned; then I, and the unknown friend to whom I write, will part for ever. Not without much dear remembrance on my side. Not without some, I hope, on his or hers” (985). If, in her “first analysis” with Bucket, some of the “failure” of her treatment lay in the fact that she could not “part” with her mother, but tried to keep her alive within herself (Abraham and Torok would call this “incorporation” as opposed to “introjection” 4), then perhaps in writing and now in concluding the story of her life, Esther is better able to separate from her mother and thus emerge from the condition of melancholy. Does not the careful inclusion of the gendered pronouns “his or hers” at the end of this sentence suggest the possibility that Esther imagines not just a reader of either sex but a specific female reader whom she remembers and whose “dear remembrance” she particularly desires?

One other possible candidate for the “unknown friend” is Esther herself. Her narrative may be addressed to an “unknown” part of herself that she realizes must be left behind if she is to move forward in her life. She recalls that self fondly at the same time that she bids it farewell. Read in this way, her written account would be oriented toward the future and toward the possibility of a stronger, more secure identity lying somewhere ahead of her. Of course, the “unknown friend” could be any combination or indeed all of these.

Although she bids farewell to her unknown friend at the beginning of this chapter, Esther is not done writing. There is still her final chapter to complete, the one entitled “The Close of Esther's Narrative.” (Whose voice speaks these chapter titles anyway?) The chapter conforms, on the whole, to the conventions of narrative closure predominant in contemporaneous works of fiction and autobiography with which Esther can be presumed to be familiar. She never mentions what books she reads, but we know that, as a student at Greenleaf school, she prepared herself to become a governess and “was not only instructed in everything that was taught at Greenleaf, but was very soon engaged in helping to instruct others” (39). It seems safe to assume, then, that she has read a few novels and knows how they are supposed to end: that is, with a summary of what has happened to most of the major figures who appear in earlier parts of the narrative.

“The Close of Esther's Narrative” provides such conventional summaries. We learn that Ada, now a widow, has given birth to a son named Richard and that she and Jarndyce are reconciled. We learn that Charley has married a neighboring miller. Esther even reports that when she looks up from her desk early in the summer morning (one of the very few times when she mentions her scene of writing), she can see the mill beginning to go round. (Is this mill a figure for the deadening routine of married life in which Charley and Esther and many Victorian women are caught?) We learn that Caddy works very hard to keep the Turveydrop dancing school going, her husband now being lame and unable to work and Mr. Turveydrop continuing to “exhibit his Deportment about town” (987). Esther “almost” forgets to mention one troubling detail in the apparently happy picture she tries to paint. Caddy and Prince's “poor little girl”—named Esther, we recall—is “deaf and dumb,” but Esther tries to put a good face even on this misfortune. Caddy is an excellent mother, she tells us, “who learns, in her scanty intervals of leisure, innumerable deaf and dumb arts, to soften the affliction of her child” (987). Caddy's marriage, it seems, is also a mill, though its demands on female labor are more visible.

We read that Esther and Allan have added a miniature Growlery onto their house “expressly for my guardian,” and as she mentions him, Esther even reports shedding a tear at the thought of Jarndyce, whom she continues to regard with “deepest love and veneration” and who acts as a father toward Ada's son and as “my husband's best and dearest friend” and “our children's darling” (988). Her praise of Jarndyce continues. Despite regarding him as “a superior being,” Esther says she feels so familiar and easy with him that “I almost wonder at myself.” (Who are “I” and “myself” in this sentence?) In many respects, nothing seems to have changed between the two of them. “I have never lost my old names, nor has he lost his; nor do I ever, when he is with us, sit in any other place than in my old chair at his side. Dame Trot, Dame Durden, Little Woman!—all just the same as ever; and I answer, Yes, dear guardian!—just the same” (988).

What is going on here, the modern reader wonders? Can this really be Dickens writing? If so, it is Dickens at his sentimental worst. How can he produce such treacly prose, especially after having written some of the magnificent passages that appear elsewhere in this book? He must be in a hurry to finish. Victorian readers required a happy ending, and so he gave them just what they wanted. But at what cost to the integrity of his novel! His sweet young heroines are always so insipid. What a disappointment! Where are waspish Miss Wade or Rosa Dartle or Estella when we need them?

Such reactions are understandable but, I think, misplaced. Critics seldom quote these final passages of Esther's at length, because they find them embarrassing. But wait—the prose gets even worse. I skip a few paragraphs to spare you the pain of reading them, but remember, this is Esther concluding her life story, concluding her “psychoanalysis,” and finally getting around to telling us, in the present tense and not in retrospect, about herself and not about other people. This is the narrator's voice; this is Esther Woodcourt! “The people even praise Me as the doctor's wife. The people even like Me as I go about, and make so much of me that I am quite abashed. I owe it all to him, my love, my pride! They like me for his sake, as I do everything I do in life for his sake” (988–89). And then there is the closing dialogue between Allan and Esther, the final part of which I am obliged to quote in full:

“My dear Dame Durden,” said Allan, drawing my arm through his, “do you ever look in the glass?”

“You know I do; you see me do it.”

“And don't you know that you are prettier than you ever were?”

I did not know that; I am not certain that I know it now. But I know that my dearest little pets are very pretty, and that my darling is very beautiful, and that my husband is very handsome, and that my guardian has the brightest and most benevolent face that ever was seen; and that they can very well do without much beauty in me—even supposing—. (989)

Like many others before me, I find this ending very disturbing. The Esther whose powerful prose I most admire and whose animated voice I have been tracking though the course of her narrative is almost entirely absent here, hidden behind a coy, self-effacing gender stereotype. The angry, desiring, giddy, critical, eloquent Esther has disappeared, and we are left with Good Esther, a feeble substitute.

What has happened, I feel confident in saying, is that Esther has once again slipped back into her “old” identity, her identity as little old woman, Dame Durden, and so on. She hides behind a mask of modesty, deflects attention onto other people, and speaks in a false voice. If the prose seems strained and excessive in its praise of Jarndyce or, in passages I did not quote, of the “diviner quality” that she sees in Ada's face, now “purified” of its earlier sadness, it is because Esther is trying so hard to force a happy ending on the story she has told, an ending that the facts of the story do not always sustain. Her determined effort to impose happiness cannot prevent discordant details, such as Caddy's labor or her deaf and dumb child, from slipping through the narrative filter.

If Esther's first “psychoanalysis” with Bucket proved only partly successful in restoring her to life, her “second analysis” undertaken on her own has not produced significantly better results, at least judging from the quality of voice in these closing sections. Esther/Eurydice has once again slipped back into the underworld, not fully alive, still searching in Ada's face or in Jarndyce's or in Allan's for the look that will bring her back to life, but finding instead only “my old looks.”

The only trace that remains of that other, more passionate Esther—the Esther whom I love—is the space opened up by the last word she writes and by the incomplete syntax of her final sentence. How do we understand the act of “supposing”? Dictionaries tell us that to suppose means to lay down as an assumption or hypothesis, to assume something tentatively as true for the sake of argument. More generally, it means to think speculatively, to imagine, to conjecture. To suppose (sub + ponere) means literally to place below or underneath; it is thus a form of mental (or perhaps vocal) displacement. We have seen Esther engaged in “supposing” on previous occasions. “If these pages contain a great deal about me, I can only suppose it must be because I have really something to do with them, and can't be kept out” (137). And again: “I suppose there is nothing Pride can so little bear with, as Pride itself, and that she was punished for her imperious manner” (299). In passages like these, to “suppose” means that Esther has begun to think more boldly and more critically. In the broadest sense, “supposing” means to consider alternate possibilities by placing something underneath what is already there.5 A supposition is thus an underthought, a subtext. What Esther “supposes” literally in the conversation with Allan is that she may in fact be beautiful, that she may be queen Esther. The Esther who remains open to “supposing” retains at least the possibility of recovering the voice I find missing from her final chapters.6 This Esther is not fully contained by her “old looks” or by her “Dame Durden” identity or by “The Close of Esther's Narrative.”

I have said that the other, more powerful Esther is largely absent from the novel's final pages. But if she is absent, where can she have gone? The logic of my argument (and of Dever's as well) suggests that we should look for her elsewhere, not so much in the doll's house that Jarndyce has prepared for her and Allan as perhaps at Chesney Wold, near her mother's tomb. “Down in Lincolnshire,” the novel's penultimate chapter, is a more fitting location for her than “The Close of Esther's Narrative.” Proximity to the mother has always been the source of Esther's greatest strength.

Has Esther been able to migrate across the boundary that separates hers from the other narrative? Do we find her “Down in Lincolnshire”? I suppose we do, and I suggest that we go looking for her there.

The final, double monthly number of Bleak House contains four illustrations. As with the regular, single numbers, these illustrations were bound at the front of the monthly installment, after the advertisements and before the letterpress began. Two of the four illustrations were destined to take their place as part of the front matter of the novel when it was published in volume form: the frontispiece, a dark plate containing an image of Chesney Wold; and the vignette title page, showing Jo the crossing sweeper. The other two illustrations correspond to passages in the verbal text of the final number. “Magnanimous conduct of Mr. Guppy” depicts the comical scene of Guppy's second proposal of marriage to Esther in chapter 64. Stylistically it is in the familiar, more linear and caricatural manner of Phiz's earlier work.

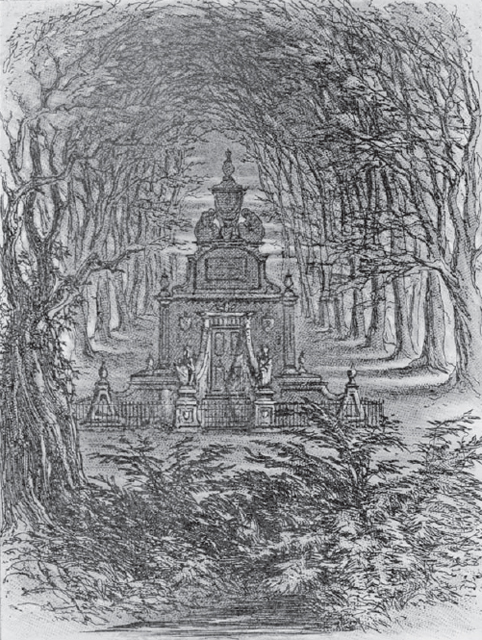

The novel's final illustration, or at least the one that accompanies the passage closest to the end of the novel's verbal text, is “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold” (fig. 9). This illustration, one of the novel's dark plates, corresponds to a passage near the beginning of chapter 66, “Down in Lincolnshire.” The passage in question describes Lady Dedlock's final resting place in the Dedlock family mausoleum and, in particular, the regular visits faithfully paid by Sir Leicester to the site of his wife's grave.

Up from among the fern in the hollow, and winding by the bridle-road among the trees, comes sometimes to this lonely spot the sound of horses' hoofs. Then may be seen Sir Leicester—invalided, bent, and almost blind, but of a worthy presence yet—riding with a stalwart man beside him, constant to his bridle-rein. When they come to a certain spot before the mausoleum door, Sir Leicester's accustomed horse stops of his own accord, and Sir Leicester, pulling off his hat, is still for a few moments before they ride away. (981)

Told by the unnamed, present-tense narrator, this brief paragraph moves in three sentences from a slightly spooky evocation of approaching sound to a description of the two visitors, Sir Leicester and the stalwart George, to their halt at a particular spot before the mausoleum, and finally to their departure.

The accompanying illustration depicts the scene just described. An elaborate, baroque mausoleum, surmounted by kneeling figures and a large urn, occupies the center of the image. The tomb is located in a long alley-way of trees that form a sinister canopy or arch over the architectural structure. The view is from the front, directly opposite the mausoleum door. An iron fence surrounds the structure. Carved statues guard the entrance, and four stone pillars mark the boundaries of the plot. In the foreground the underbrush is low enough so as not to obscure access to the view. The overall atmosphere, enhanced by the dark shadows of the trees and the dark lineation of the plate, is decidedly gloomy. The viewpoint is presumably that of Sir Leicester and George from their horses. Although both men pause before the gravesite, it is Sir Leicester for whom this place has special meaning. He is the image's unseen internal focalizer. The focalization can be understood equally as external, as located in a heteroperceptive viewpoint. “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold” is thus an example of what Bal calls free indirect perception.

FIG. 9. “The Mausoleum at Chesney World.”

Two details in the verbal text stand out for me: the mausoleum door and Sir Leicester's poor eyesight. The first raises issues of access to and from the crypt; the second may explain why Sir Leicester, assuming him to be the unseen internal focalizer of the illustration, does not notice the strange figure, from all appearances female, standing inside the fence and just in front of the door.7 Who is this figure?

Not all editions of Bleak House show this figure clearly. In some, including both original serial parts and bound volumes of the first edition, the ink is so dark that the figure fades into the shadows. This loss of precision may in some cases be simply the result of bad inking. In others, it may be due to the fact that Dickens's publishers, Bradbury and Evans, had taken to reproducing Phiz's images using lithography, a technique in which designs were copied onto stone with a greasy material and printed impressions taken from them. In an undated letter to Dickens, Browne complained particularly of the ruinous effect that lithography had on his plates for Bleak House. “I am told,” he writes, “that from 15 to 25,000 [copies] are monthly printed from lithographic transfers—some of these impressions, when the etching is light and sketchy, will pass muster with the uninitiated—but, the more elaborate the etching—the more villainous the transfer.”8 Browne is correct to complain and would be fully justified, in the case of a dark plate such as “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold,” in saying that “wretched printing” has ruined a subtle effect that might otherwise be visible. Whatever the reason for the considerable variation between different impressions of the mausoleum image, I confess that I take a certain pleasure at the thought that some early editions of Bleak House contain the strange figure standing by the mausoleum door and some do not. The figure is a ghost, and, as ghosts are wont to do, it comes and goes. Some people see the ghost, and others, like Sir Leicester, do not. Sometimes the ghost appears distinctly, and sometimes it fades into the shadows—or rather, into the ink.

From as early as chapter 2, where the view from Lady Dedlock's windows is described as “alternately a lead-coloured view, and a view in India ink” (21), ink is an important motif in the novel. (Did this passage encourage Phiz to produce so many dark plates?) Recalling her first sight of Caddy Jellyby, Esther introduces her as “a jaded, and unhealthy-looking, though by no means plain girl, at the writing table, who sat biting the feather of her pen, and staring at us. I suppose nobody was ever in such a state of ink” (53). When Guppy first appears in the narrative, Esther describes him as “a young man who had inked himself by accident” (42). Krook's rag and bottle warehouse contains “quantities of dirty bottles: blacking bottles, medicine bottles, ginger-beer and soda-water bottles, pickle bottles, wine bottles, ink bottles…. There were a great many ink bottles” (67–68).

The business of the law could not exist without vast supplies of paper, ink, and other writing materials.9 Mr. Snagsby, Law Stationer in Cooks Court, makes his living from this trade. The narrator tells us that Snagsby “has dealt in all sorts of blank forms of legal process.” Here follows a marvelous catalog of articles for sale in Snagsby's shop that is too long to quote in its entirety, but that includes “office-quills, pens, ink, India-rubber, pounce, pins, pencils, sealing-wax, and wafers;…red tape, and green ferret;…string boxes, rulers, inkstands—glass and leaden, penknives, scissors, bodkins, and other small office-cutlery” (154). The passage continues with an explanation of how it happens that Snagsby's shop bears the name “PEFFER and SNAGSBY,” since Peffer is now dead, and it concludes with a fanciful account of the return of Snagsby's former business partner's ghost—one of the many ghosts in this book and one closely connected to the business of paper and ink.

Ink is everywhere in Bleak House. Tulkinghorn toys with inkstand tops as he tries to solve the mystery of Lady Dedlock's reaction to seeing Nemo's handwriting. Nemo of course is a copyist, and when we are first introduced to the room in which he died, the narrator describes it as “a wilderness marked with a rain of ink” (164). The novel is full of letters and legal documents, all written by hand and all in ink. Caddy's deaf and dumb baby is born with “curious little dark veins in its face, and curious little dark marks under its eyes, like faint remembrances of poor Caddy's inky days” (768). Even Jo, though excluded from legal process and from all forms of writing, bears traces of ink in his speech. For him the inquest is an “Inkwhich” (260), and he frequently declares, “I don't know nothink!” (264). To be stained with ink in this book is dangerous. Esther too, we recall, is a writer, and though she scarcely ever mentions her writing implements, she too must occasionally carry the signs of her inky involvement. At the beginning of the chapter in which she reports being taken ill, she tries to teach her maid Charley to write. In Charley's hand, however, “every pen appeared to become perversely animated, and to go wrong and crooked, and to stop, and splash and sidle into corners, like a saddle donkey” (486). Is it too much to suggest that ink may be a figure for the disease that passes from the graveyard where the law-writer's corpse is buried to Jo and then to Charley, whom Esther nurses, and finally to Esther herself ?

I have indulged myself with this digression on the subject of ink in order to prepare the way for a consideration of the inky figure in “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold.” I believe the figure is a ghost, something that no previous critic or commentator on the novel to my knowledge seems to have noticed. But whose ghost would it be? Certainly the family ghost, the ghost of the first Lady Dedlock in the story told by Mrs. Rouncewell in chapter 7, but also the ghost of the most recent Lady Dedlock, risen here to greet Sir Leicester though he cannot see her.

The ghost is also Esther, I believe, not in her incarnation as “Good Esther,” the disappointing heroine of the marriage plot, but the darker, ghostwalking and ghostwriting Esther whose advocate I have tried throughout this essay to be. Moreover—and here I'm just supposing—I think that Esther is the unseen internal focalizer of this scene. She is the one who sees the ghost, or rather, since she is the ghost, she here watches her own ghostly emanation from her ghostly retrospective viewpoint.10 Sir Leicester does not see the ghost, and there is no indication in the verbal text that the other narrator has noted it either. Perhaps the unseen external focalizer shares her vision in free indirect perception, but there is no way we can be sure of this. In any event, if these speculations have merit, there is reason to believe that Esther—or a part of her—has fled from her constricted identity as the doctor's wife, has migrated across the boundary separating her from the other narrative, and has joined her mother “down in Lincolnshire.” “Down” and “up” indicate crucial spatial locations in the novel, intrapsychic as well as on the map of England. Esther seems capable of being in more than one place at the same time.

Bleak House has many endings. It is also a novel that refuses to end. A multiplot novel, it contains endings to many of its minor subplots. Richard dies, Charley marries, Tulkinghorn is murdered, Jarndyce and Jarndyce gets consumed in costs, George visits his brother and goes to live in the Keeper's lodge at Chesney Wold. Even the Bagnets and Mrs. Rouncewell and Sir Leicester's debilitated cousin make brief final appearances. The book's major plots have their endings too. One is at the end of monthly number 18, when Esther discovers her mother's body. Another is at the end of the final monthly number, “The Close of Esther's Narrative,” where Esther retreats to her role as Dame Durden, but leaves open the possibility of “supposing—.” Yet another is the book's final illustration, “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold,” which shows us that the family ghost continues to walk. Another ending, the last that I will consider, is the novel's penultimate chapter, “Down in Lincolnshire,” which is the final chapter told by the unnamed present-tense narrator.

The principal figures in this chapter are architectural, first the mausoleum (with its illustration) and finally Chesney Wold itself (pictured in the frontispiece). A synecdoche for the nation as a whole (the Bleak House of the novel's title), Chesney Wold is a haunted house. Its resident ghost, however, turns out most delightfully to be Volumnia, Sir Leicester's antiquated cousin, who occupies the otherwise empty house and “holds even the dragon Boredom at bay” (983). Whereas the mausoleum remains a place of gloom, Chesney Wold, by contrast, is occasionally transformed into a place of ghostly gaiety. In a lengthy paragraph that describes Volumnia's delight in the occasional country dances held in a neighboring assembly room, the narrator describes how Volumnia, “a tuckered sylph…in fairy form,” skips about with “girlish vivacity” as she did long ago in her youth.

Then does she twirl and twine, a pastoral nymph of good family, through the mazes of the dance. Then do the swains appear with tea, with lemonade, with sandwiches, with homage. [Notice the playful zeugma here!] Then is she kind and cruel, stately and unassuming, various, beautifully wilful. Then is there a singular kind of parallel between her and the little glass chandeliers of another age, embellishing that assembly-room; which, with their meagre stems, their spare little drops, their disappointing knobs where no drops are, their bare little stalks from which knobs and drops have both departed, and their little feeble prismatic twinkling, all seem Volumnias. (984)

It is a comic danse macabre, at once ludicrous and grotesque—a grim emblem of mortality, but also a reminder that ghosts are sometimes funny. The final image of the chandelier, with its multiple reflections of Volumnia in prismatic stems and “drops” (recalling the Ghost's Walk refrain, “drip, drip, drip,” as well as Esther's parting “thaw-drop” kiss at Windsor), is a fitting image for the novel as a whole, in which every female figure seems somehow the ghostly refraction of Esther and her mother.