The Mahdists fought the Italians for the first time at Agordat on 27 June 1890. About 1,000 warriors raided the Beni Amer, a tribe under Italian protection, and then went on to the wells at Agordat, on the road between the Sudan and northern Eritrea. An Italian force of two ascari companies surprised and routed them; Italian losses were only three killed and eight wounded, while the Mahdists lost about 250 dead. In 1892 the Mahdists raided again, and on 26 June a force of 120 ascari and about 200 allied Baria warriors beat them at Serobeti. Again, Italian losses were minimal – three killed and ten wounded – while the raiders lost about 100 dead and wounded out of a total of some 1,000 men. Twice the ascari had shown solid discipline while facing a larger force, and had emerged victorious. The inferior weaponry and fire discipline of the Mahdists played a large part in these defeats.

Major-General Oreste Baratieri took over as military commander of Italian forces in Africa on 1 November 1891, and also became civil governor of the colony on 22 February 1892. Baratieri had fought under Garibaldi during the wars of Italian unification, and was one of the most respected Italian generals of his time. He instituted a series of civil and military reforms to make the colony more efficient and its garrison effective. The latter was established by royal decree on 11 December 1892. The Italian troops included a battalion of Cacciatori (light infantry), a section of artillery artificers, a medical section, and a section of engineers. The main force was to be four native infantry battalions, two squadrons of native cavalry, and two mountain batteries. There were also mixed Italian/native contingents that included one company each of gunners, engineers and commissariat. This made a grand total of 6,561 men, of whom 2,115 were Italians. Facing the Mahdists, and with tension increasing with the Ethiopians, this garrison was soon strengthened by the addition of seven battalions, three of which were Italian volunteers (forming new 1st, 2nd and 3rd Inf Bns) and four of local ascari, plus another native battery. A Native Mobile Militia of 1,500 was also recruited, the best of them being encouraged to join the regular units. Like all the other colonial powers, the Italians also made widespread use of native irregulars recruited and led by local chiefs.

The first big test came at the second battle of Agordat on 21 December 1893. A force of about 12,000 Mahdists, including some 600 elite Baqqara cavalry, headed south out of the Sudan towards Agordat and the Italian colony. Facing them were 42 Italian officers and 23 Italian other ranks, 2,106 ascari, and eight mountain guns. The Italian force anchored itself on either side of the fort at Agordat, and from this strong position they repelled a mass attack, though not without significant losses – four Italians and 104 ascari killed, three Italians and 121 ascari wounded. The Mahdists lost about 2,000 killed and wounded, and 180 captured.

Ras Mangasha Yohannes, the nephew and designated heir to the Emperor Yohannes IV. Although superseded by Menelik, he remained an influential leader in the Tigré region. Photographed c. 1894, he wears a richly decorated lembd over a silk shirt-tunic, and rides a horse with elaborate silver-decorated tack. Again, he carries both a traditional conical shield and a modern bolt-action rifle – compare with Plate A1. (Courtesy SME/US)

When the Mahdists launched raids across the border in the spring of 1894, the Italians decided to take the offensive and capture Kassala, an important Mahdist town. General Baratieri led 56 Italian officers and 41 Italian other ranks, along with 2,526 ascari and two mountain guns. At Kassala on 17 July they clashed with about 2,000 Mahdist infantry and 600 Baqqara cavalry. The Italians formed two squares, which inflicted heavy losses on the mass attacks by the Mahdists, before an Italian counterattack ended the battle. The Italians suffered an officer and 27 men killed, and two native NCOs and 39 men wounded; Mahdist casualties numbered 1,400 dead and wounded – a majority of their force. The Italians also captured 52 flags, some 600 rifles, 50 pistols, two cannons, 59 horses, and 175 cattle. This crushing defeat stopped Mahdist incursions for more than a year, and earned Baratieri acclaim at home. (In 1896 the Mahdi’s followers would make several more incursions into Eritrean territory, but without success. Fighting the Italians seriously weakened the Mahdiyya, and contributed to its defeat at the hands of Kitchener’s Anglo-Egyptian army at Omdurman in 1898.)

Proxy war in Tigré, 1890–94

While the Italians enjoyed success against the Mahdists, more trouble was brewing with the Ethiopians. The Italians continued to push inland and consolidate their control, causing friction with the inhabitants. On 3 August 1889, Italy had occupied Asmara, the capital of Hamacen province. This had been ruled by Ras Mangasha, Yohannes’ nephew who had lost the imperial succession to Menelik. Menelik and the Italians agreed to divide the Tigré region between them, and they invaded on both fronts in January 1890. The Italians proclaimed the colony of Eritrea on 1 January, providing it with a civil government in addition to the military force. In March, Menelik received the submission of Ras Mangasha and of Ras Alula, Ethiopia’s most capable military leader, and the other Tigréan chiefs soon fell into line.

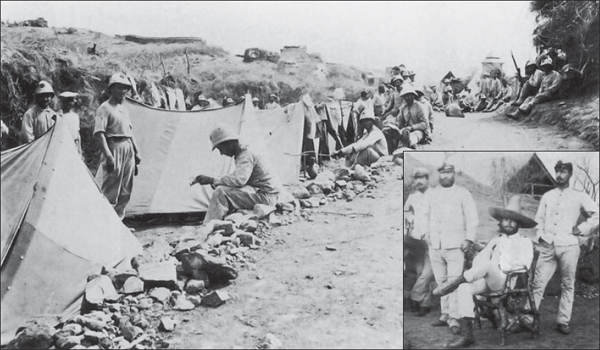

The 1st Company, 3rd Bersaglieri Regt encamped at Saati in 1888. Conditions in such camps were often primitive, contributing to the generally poor state of health of the Italian Corpo Speciale d’Africa. Note that most of the men have removed the distinctive Bersaglieri cockerel plumes from their cork sun helmets. (Inset) Officers of the 3rd Bersaglieri at Saati; the seated officer wears a straw naval or ‘Beilul’ hat, and the others the small M1887 white service cap, all with white uniforms – see Plate H2. (Courtesy SME/US)

Menelik treated Ras Mangasha with care, since he could use him: the emperor offered Mangasha the crown of Tigré if he could reconquer the parts of that region lost to the Italians. Mangasha duly returned to Tigré and plotted a rebellion; while pretending to be friendly towards the Italians, he called for a general mobilization under the pretence of fighting the Mahdists. On 15 December 1894 he was forced to show his hand when Batha Agos, chief of Okule-Kasai province in northern Tigré, rebelled against the Italians. General Baratieri sent Maj Toselli with 1,500 men and two guns from Asmara to Saganeiti, capital of Okule-Kasai. On 18 December, Toselli discovered that the chief and his force of 1,600 warriors were besieging the small Italian fort of Halai, garrisoned by a company of 220 men. Batha Agos’ men had almost taken the fort when Toselli hit them from the rear; the chief was killed, and his army disintegrated. The Italians lost 11 killed and 22 wounded.

General Baratieri now took personal command of a march against Ras Mangasha. On 28 December he camped near Adowa, an important religious and economic centre with a population of about 15,000. This town is at a junction of four roads, leading west to Axum and Gonder, north to Asmara and Massawa, east to Adigrat, and south to Mekele, the capital of Tigré and former seat of the Emperor Yohannes. There, Baratieri received the submission of several chiefs as well as clergy, but Mangasha still threatened his lines of communication and supply. Baratieri withdrew from Adowa, and after much manoeuvring on both sides the armies clashed on 13 January 1895 at Coatit. The Italian force numbered 3,883 men – three ascari battalions of about 1,100 each, 66 Italian officers and 105 Italian rankers, 400 local irregulars, 28 ascari lancers, and four mountain guns. Ras Mangasha had 12,000 men with firearms and 7,000 with swords and spears, but an estimated one-third to a half of their firearms were antiquated muzzle-loaders.

The battle of Coatit

The terrain was typical of the region – rough and broken, with sheer mountains and steep gorges dividing the field. At dawn on 13 January 1895 the Italians advanced, and bombarded the Ethiopian camp with artillery. The Ethiopians were surprised, but soon got in order, and attacked. The ascari stood off aggressive charges by superior numbers, and then pushed forward, alternating steady volleys with bayonet charges. Ras Mangasha put pressure on the irregulars holding the Italian left, and at one stage this forced the entire line to give up all the ground they had gained; but in the event the new Italian position proved stronger, and successive Ethiopian attacks withered under orderly fire. After a few hours the Ethiopians broke off; the following day saw some half-hearted attacks before Mangasha withdrew that night. The Italians pursued for 25 miles before coming upon the Tigréan camp late on 15 January. Again they bombarded it and the Ethiopians slipped away under cover of darkness, leaving behind much equipment.

This victory cost the Italians three officers and 92 men killed, and two officers and 227 men wounded, while the Ethiopians lost an estimated 1,500 killed and about twice that number wounded. The victory at Coatit buoyed Italian confidence, and led to dangerous miscalculations about their own and their enemy’s abilities. At that time colonial adventures seemed attractive to many politicians, as a national distraction from economic recession, a financial crisis, and widespread civil unrest. (In 1894 the government of Francesco Crispi had had to send no fewer than 40,000 troops to pacify Sicily, and there was also trouble in central Italy and as far north as the Po valley.)

This proxy war between Menelik’s catspaw Ras Mangasha and the Italians did nothing to lessen their mutual hostility. The Italians tried to make allies among Menelik’s nobility, hoping to take advantage of the incessant political infighting for which Ethiopia (like Italy) was notorious. They were in regular contact with nearly all the key players, but to no avail; some of the aristocrats shared these messages with Menelik, and together they plotted how best to trick the Italians. The Italians failed to realize that Menelik’s reorganized system of government benefitted all of the aristocracy, instead of just one tribe over the rest. Menelik never demanded the annual tribute to which he was entitled from the northern princes, precisely because he wanted them loyal in case of an Italian advance. His centralized taxation system anyway brought him in greater riches than any emperor in recent memory, making him a good man to follow.

Matters were quickly coming to a head when, in March 1895, Baratieri fortified Adigrat and Mekele, two important towns on the roads between the coast and the interior. Baratieri even pushed as far as Adowa once more. He wanted to go further, but the nearly bankrupt government in Rome refused him the funding for such an extended line. Baratieri complained that he could not do his job without more money. He sensed that Menelik was preparing for war, and on three occasions in 1895 he sent in his resignation. Rome refused to accept it, and finally caved in and increased his funding – although not by enough.