About 7 miles east of Adowa, and rather less than 4 miles from the Ethiopian advance camp in the valley of Mariam Shavitu, a series of towering mountains are divided by narrow valleys: from the north, Mt Eshasho, Rebbi Arienni and Mt Raio, with to the south-west of them the Spur of Belah, the Hill of Belah, Mt Belah, and to the south Mount Kaulos and Mt Semaiata. Across a couple of miles of lower but still very rolling and difficult ground to the west of them is another line of heights: Mt Nasraui, Mt Gusoso, and Mt Enda Kidane. These look down to both the north and west into the hooked valley of Mariam Shavitu, and southwest towards Adowa town (see map, page 16). Baratieri decided to advance westwards to these twin chains of mountains and challenge the Ethiopians to battle; if he threatened the important town of Adowa, Menelik would have to respond. While the Italian position would not be as strong as at Sauria, the mountains should still offer the Italians protection from flanking movements.

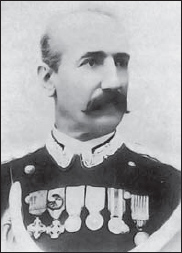

Giuseppe Arimondi, photographed when he was a lieutenant-colonel. Promoted major-general in February 1894, he would be killed at the battle of Adowa two years later while commanding the 1st Infantry Bde and the Italian centre column. (Piero Crociani Collection)

Major-General Giuseppe Ellena, who commanded the reserve 3rd Infantry Bde, was the most recent arrival of the five Italian generals at Adowa. He would assist Gen Baratieri in conducting the subsequent retreat northwards by the survivors of his and Arimondi’s brigades. (Courtesy SME/US)

However, for Baratieri to bring his force to the designated objectives was fraught with difficulties. His men would have to march by night in three separate columns, and get into position before dawn in order to achieve surprise. Baratieri’s maps were sketchy and inaccurate, and his local scouts were not as familiar with the terrain as they claimed, while some were actually spies for Menelik. One observer commented that the camp at Sauria was wide open; Ethiopian civilians came and went at will, selling goods and services to the soldiers. However, while Menelik certainly had a thorough knowledge of the Italians’ numbers, his informants did not have time to report the last-minute Italian advance.

The Italian force got on the march at 9pm on the evening of 29 February. Generals Albertone, Arimondi, and Dabormida led three separate columns – respectively, the Native Brigade, 1st and 2nd Infantry Brigades – while Gen Ellena’s 3rd Infantry Brigade followed Arimondi’s as rearguard and reserve. Their first objective was Rebbi Arienni, part of the eastern chain of mountains situated just over 7 miles short of Adowa; Baratieri intended to fight in this first line of heights, and, if things went well, to advance to the western hills within sight of the town.

While the weather was fair, the night march was difficult. The terrain in this region is extremely rough, with steep, at times sheer mountains and hills rising up everywhere, separated by narrow valleys and streams. At that time roads were nonexistent, and the soldiers had to take narrow, winding footpaths. While the terrain is rugged, the valleys are fertile, and the Italians passed numerous farms on the way; the country was full of eyes.

The Italian columns inevitably ‘concertina’d’, like any file of men moving across rough terrain, especially by night, and the brigades soon found themselves getting mixed up. Dabormida’s rear battalion went too far to the left, and ended up behind Arimondi’s. This mistake was soon corrected, but several times Baratieri had to order one column or another to close up as units got separated in the dark. Even worse, Arimondi had to stop for more than an hour as Gen Albertone’s troops filed past him; Albertone was supposed to have been on a different path on the left (south).

After getting back on his proper path, Albertone forged ahead; but he ended up in the wrong position, well ahead and to the left of the rest of the force, and this ruined Baratieri’s plan of battle. Baratieri had wanted Albertone to occupy a flat-topped hill south of the left flank of Mt Belah, which would constitute the army’s forward position. Baratieri thought this hill was called Kidane Meret, but actually it does not have a name. There is a mountain called Enda Kidane 4 miles further on, with a smaller feature north of it – which is the height that any local would point to if asked for the location of the ‘Hill of Kidane Meret’. Albertone probably thought that the hill he first reached soon after 3am on 1 March was Baratieri’s ‘Kidane Meret’; but after waiting for about an hour, and not seeing Arimondi coming into line on his right as he expected, he started to mistrust his own instincts. (Arimondi, of course, had been badly delayed by the obstruction of the track by Albertone’s own brigade.) Albertone’s guides insisted that they had not yet reached Kidane Meret; so he followed their lead and advanced. When he halted, he was isolated well to the south-west of the rest of the army, at the Hill of Enda Kidane Meret – the ‘real’ Kidane Meret. In the western chain of mountains, this overlooks the Mariam Shavitu valley containing Adowa; perhaps Albertone convinced himself that Baratieri wanted him to threaten the town.

Major-General Matteo Albertone was made second-in-command over Italian forces in Africa on 1 October 1889. Despite his many victories and long experience in the region, his misinterpretation of his movement order while in command of the Native Bde and the left column at Adowa was a major cause of the Italian defeat; it completely distorted the battle line on which Baratieri had intended to fight. Albertone was captured by the Ethiopians, and not released until 6 May 1897. (Courtesy SME/US)

Meanwhile, the other two columns were slowly getting into their designated positions in the eastern chain of mountains. Dabormida’s brigade arrived at Rebbi Arienni by 5.15am on 1 March. Fifteen minutes later, Arimondi began to occupy the eastern slope of this same height, and to extend his line all the way down to Mount Raio, thus forming the Italian centre. Ellena’s reserve column was massed close behind Dabormida in the Hollow of Gundapta.

If Albertone’s brigade had been where they should have been, the Italians would have been in a strong position, covering the gaps in the first row of mountains from Mt Eshasho down to the ground south of Mts Belah and Raio. The brigades would have been divided, but safe from flanking manoeuvres, since the mountains – though high, steep, and difficult to climb – were not so bulky as to impede reserves moving around their reverse slopes to reinforce various parts of the line. The nature of the terrain meant that the Ethiopians could not encircle Baratieri’s force, nor go around it unexpectedly and cut the Italian lines of communication. They would have had to charge directly against the Italian units, across ground favouring the defender.