Character and composition

Most of the colonial army that faced this exotic but highly effective force was made up of Eritrean or Sudanese troops – ascari. While some of the Italian officers and soldiers of the Corpo Speciale d’Africa had been in the colony for months or even years, most of the formed Italian units were new arrivals with only a vague idea of where they were or what they faced. The garrison troops were supplemented by hired Eritrean irregulars, who were little different from the warriors who fought under Menelik.

The Italian Army was raised by conscription, for three years’ service with the colours followed by a reserve obligation. Service was generally regarded as a rite of manhood and ‘school of the nation’; however, even on home service the efficiency and internal cohesion of most regiments were hampered by Italy’s chronic localism. The government’s obsession with unifying the Italian population led to an unwieldy system of posting units away from their recruitment areas, and mixing sub-units from different regions (and thus speaking different dialects). The mutual incomprehension between officers speaking Tuscan Italian and the bulk of their illiterate rankers widened an already yawning social gulf.

Late 19th-century European observers generally had a low opinion of the Italian Army. Italian generals and their troops had performed badly against the Austrians in 1866 (when Italy had tried to snatch a profit from the brief Austro-Prussian War), and their victories against the poorly-armed and disorganized Mahdists were considered insufficient proof of their ability. It must be remembered, however, that at Adowa the Italians and ascari fought stubbornly against a vastly superior force of Ethiopians for most of the day. Ethiopian eyewitnesses, even in the midst of exulting over their victory, made note that the Italian side fought bravely; and all sources agree that the ascari were as good as – or better than – the Italian regulars.

While the more experienced Italian colonial troops and ascari acquitted themselves well, the most recent arrivals from Italy were less reliable. The units were raised from individual conscripts who volunteered for African service, formed into new battalions numbered in sequence, which were organized into purely tactical regiments and brigades. Sources for the renumbering are confusing, but it appears that only the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Bns of Fanteria d’Africa had served in Africa prior to December 1895, and that the higher-numbered battalions were sent to the front almost straight from the harbour. Unfamiliar with the country and climate, they naturally suffered from the hot days, cold nights, strange food and unforgiving terrain. This ignorance was shared by both officers and men, who had been thrown together with little time to get to know each other. This inevitably led to confusion both in camp and in the field, and one witness states that when asked what unit they were in, many newcomers replied with the number of their old unit back home. Some officers only found out which troops they were to command at the last moment, and simply wrote their branch, battalion and regiment in ink on their sun helmets.

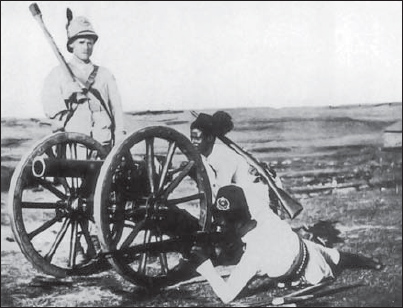

Italian NCOS and officers posing at Mekele in 1895, uniformed in differing shades of khaki and in white; three in the foreground wear the dark blue cap illustrated in Plate H1. They come from a variety of branches – crossed cannons are just visible on the cap of the artillery NCO reclining on the right. (Courtesy SME/US)

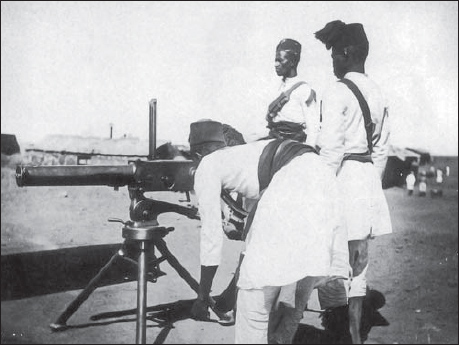

An African NCO overseeing practice with a Gardner machine gun in Eritrea. Automatic weapons, so effective in the British campaigns in the Sudan, were not used to any great extent by the Italians. Due to imprecise terminology, the documentary record is unclear as to how many there were in the colony, or if any were used at Adowa. If they were, they played no significant part in the battle. (Courtesy SME/US)

While the original, genuine volunteers for colonial service were presumably eager, those shipped out in 1895–96 had been gathered with a degree of compulsion, and it is also highly questionable how much useful training they had received before Adowa. The rapidly dwindling morale of these newcomers was one factor in Gen Baratieri’s decision to advance on 29 February 1896. Fresh from Italy, with racist assumptions about how easy it would be to defeat the Ethiopians, the new arrivals started grumbling while the army waited at Sauria, and morale and discipline withered. The ascari were apparently unimpressed by what they saw of the Italian rank and file.

The Italian battalions had 450–500 rifles each (see order of battle). The native battalions had been much larger, consisting of five companies of 250 men; after the middle of 1895 this changed to four companies of 300 men each, but the battalions’ field strength at Adowa was usually below 1,000 rifles. Companies were divided into ‘centurias’ of 100 men, and these into ‘buluks’ of 25 men. An Italian major commanded each battalion, and an Italian captain each company, assisted by two Italian lieutenants and an Italian NCO; after the 1895 reform a third Italian lieutenant was added. Natives were not eligible for these positions, but could rise to the rank of jus-bashi (subaltern), of which there were two per company. Originally the company had included Italian sergeants, but these men resented taking orders from their native superiors and their employment was soon discontinued.

Logistics

The equipment provided for Italian units was often substandard. For example, the heavy boots were unsuited for the terrain, caused no end of pain for the average soldier, and also wore out quickly. General Baratieri had repeatedly requested proper alpine boots, but never received them. Near the end of the battle of Adowa, Italian soldiers were seen taking boots off their dead comrades to replace their own worn-out ones. The uniforms were too hot for the climate, and got torn to shreds by thorn-bushes. Tools such as picks and shovels were of inferior quality and soon wore out in use on the rocky soil, and even many bayonets and rifles had become unusable by the time they were needed at Adowa.

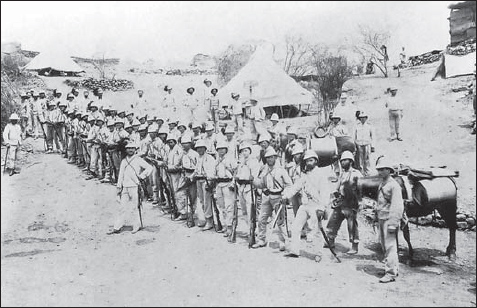

Bersaglieri ready to go out on manoeuvres from Saati in 1888. The rarity of photos of Italian infantry in the 1896 campaign is due to the fact that most of the correspondents in Eritrea, foreseeing that the expedition would end badly, chose to remain in Massawa; the only photographer to accompany the advance, Pippo Ledru, lost his equipment at Adowa. Note the two mules with water kegs; water was a constant problem for the Italians, as the local water often made them sick, and the highlands can be very dry. (Courtesy SME/US)

There were also gaps in the Italians’ logistics. The food supply was unreliable, and the men often had to subsist on half rations; much of the fatigue that the soldiers showed in the later hours of the battle of Adowa may be attributed to this. The fact that the available rations were expected to give out on 2 or 3 March was one of the reasons that Baratieri gave for advancing against Menelik on 29 February. There was also a shortage of pack animals, so those that the Italians did have became overworked. Knowledge of the region was patchy even among those officers who had been in Africa for months. One complained: ‘Having no maps or sketches, we based our calculations solely on the information obtained from an ill-organized [intelligence] service of natives, of whom we knew little or nothing, and who in the opinion of most people were merely Abyssinian spies, munificently paid by us.’ Ethiopians of both sexes were a common sight in the camps and forts, welcomed for the food and female company they offered the troops, and while the smarter men on the Italian side must have realized that many were spying for Menelik, nothing was done to keep them away.

One of the dozens of brass Type 75B mountain guns captured by the Ethiopians at Adowa, later recaptured during the Italian invasion of 1935–36; several are now on display at the Museo Storico della Fanteria in Rome. In rough terrain these weapons could be disassembled easily into loads for mules, or even for teams of men. (Author’s photograph)

The army was supplied with heliographs, but for some reason these were never used at Adowa (it has been suggested that the brigade commanders ‘forgot’ to take them forward, perhaps to allow themselves relative freedom from micro-management by Gen Baratieri). Many of the messengers sent between the separated brigades during the battle were either very slow or never made it at all. The battlefield had many farmsteads scattered about, and it is possible that some of these couriers were waylaid by local farmers – as were large numbers of the unfortunate stragglers during the final retreat.

Like all European armies, the Italians had a generally well-trained and well-equipped medical corps, but during the Adowa campaign insufficient funding led to a shortage of supplies of all kinds, and it appears that – like the commissariat – the medical corps suffered from this. Its troubles were exacerbated by the huge number of wounded and the general chaos after Adowa. In forts and rear bases, however, the Italian soldier could expect as good treatment as late 19th-century medicine could provide.

Ascari gunners practising with a Type 75B mountain gun, as used at Adowa and in most other battles of the campaign; the Native Artillery were distinguished by yellow sashes. The airburst shrapnel round of the mountain gun could be devastating, but the crews were vulnerable to skilled Ethiopian riflemen working their way forwards under cover, and at Adowa most were overrun and killed during the final rushes. The Italians enlisted Sudanese for the artillery, since they were unwilling to spread this dangerous technical skill among the population of their colony – though as it turned out, Menelik’s own gun crews proved themselves fairly capable despite their lack of formal training. (Piero Crociani Collection)

Tactics

General Arimondi had developed a tactic of having reserves echeloned in rear of the main line of battle, who could come out to stop Ethiopian enveloping attacks or to counterattack weakened enemy groups. Arimondi urged his men to fight in extended line in order to reduce casualties from enemy firearms. This looser formation worked well against the Mahdist Dervishes, but the Ethiopians had better weapons and were better marksmen. In any case, newly arrived officers without battlefield experience tended to use parade-ground tactics in the field. The Italians at Adowa fought shoulder to shoulder in close formation, providing good targets for skilled Ethiopian riflemen. (In justice, it must be said that inadequately trained soldiers who might have trouble recognizing their officers probably should not have been deployed in loose formation anyway.)

Rifles

The Italians used a variety of rifles during their colonial adventures in East Africa. At the beginning of the colonial period they carried the 10.4mm M1870 Vetterli, a single-shot modification (on grounds of economy) of the Swiss M1869 bolt-action repeater. By the time of the Adowa campaign they had introduced the M1870/87 Vetterli-Vitali, an Italian modification with a box magazine holding four rounds.

Sources differ over whether any of the Italian troops at Adowa used the Army’s latest weapon, the 6.5mm M1891 Carcano with a six-round box magazine, although it had arrived in Eritrea. A shortage of its new smokeless-powder ammunition (and the unwillingness of the cash-strapped Italian government to order more) meant that M1891s were actually collected from some of the reinforcements destined for Africa, and replaced with older types for which there was more ammunition in stock. Some Italian troops seem to have been issued not even with Vetterlis, but with old ‘rolling-block’ Remingtons left over from a previous generation. These were of both Italian and Egyptian licence-built models differing in small details, some dating back to the army of the Papal States and the years before unification. The Remington was an extremely sturdy and simple weapon, but some had been poorly stored and proved unreliable. Another problem was that troops trained on bolt-action magazine rifles found the action unfamiliar and cumbersome, and this slowed down their rate of fire on a battlefield where sustained rapid fire became vital.2

The Italian Army at Adowa, 1 March 1896

| Native Brigade (General Albertone) | |

| 1st Native Battalion (Maj Turitto) | 950 rifles |

| 6th Native Bn (Maj Cossu) | 850 rifles |

| 7th Native Bn (Maj Valli) | 950 rifles |

| 8th Native Bn (Maj Gamerra) | 950 rifles |

| Irregulars: | |

| Oluke-Kusai & Hamacen | |

| bands (Lts Sapelli & De Luca) | 376 rifles |

| Artillery: | |

| 1st Native Battery (Capt Henri) | 4 guns |

| 2nd Section/2nd Mtn Bty (Lt Vibi) | 2 guns |

| 3rd Mtn Bty (Capt Bianchini) | 4 guns |

| 4th Mtn Bty (Capt Masotto) | 4 guns |

| Totals: | 4,076 rifles, 14 guns |

| 1st Infantry Brigade (General Arimondi) | |

| 1st Bersaglieri Regiment (Col Stevani): | |

| 1st Bn (Maj De Stefano) | 423 rifles |

| 2nd Bn (LtCol Compiano) | 350 rifles |

| 2nd Infantry Regiment (Col Brusati): | |

| 2nd Inf Bn (Maj Viancini) | 450 rifles |

| 4th Inf Bn (Maj De Amicis) | 500 rifles |

| 9th Inf Bn (Maj Baudoin) | 550 rifles |

| Attached: | |

| 1st Co/5th Native Bn (Capt Pavesi) | 220 rifles |

| Artillery: | |

| 8th Mtn Bty (Capt Loffredo) | 6 guns |

| 11th Mtn Bty (Capt Franzini) | 6 guns |

| Totals: | 2,493 rifles, 12 guns |

| 2nd Infantry Brigade (General Dabormida) | |

| 3rd Infantry Regiment (Col Ragni): | |

| 5th Inf Bn (Maj Giordano) | 430 rifles |

| 6th Inf Bn (Maj Prato) | 430 rifles |

| 10th Inf Bn (Maj De Fonseca) | 450 rifles |

| 6th Infantry Regiment (Col Airaghi): | |

| 3rd Inf Bn (Maj Branchi) | 430 rifles |

| 13th Inf Bn (Maj Rayneri) | 450 rifles |

| 14th Inf Bn (Maj Solaro) | 450 rifles |

| Attached: | |

| Native Mobile Militia Bn (Maj De Vito) | 950 rifles |

| Native Kitet Co of Asmara (Capt Sermasi) | 210 rifles |

| Artillery: | |

| 2nd Artillery Brigade (Col Zola): | |

| 5th Mtn Bty (Capt Mottino) | 6 guns |

| 6th Mtn Bty (Capt Regazzi) | 6 guns |

| 7th Mtn Bty (Capt Gisla) | 6 guns |

| Totals: | 3,800 rifles, 18 guns |

| 3rd Infantry Brigade (General Ellena) | |

| 4th Infantry Regiment (Col Romero): | |

| 7th Inf Bn (Maj Montecchi) | 450 rifles |

| 8th Inf Bn (LtCol Violante) | 450 rifles |

| 11th Inf Bn (Maj Manfredi) | 480 rifles |

| 5th Infantry Regiment (Col Nava): | |

| Alpini Bn (LtCol Menini) | 550 rifles |

| 15th Inf Bn (Maj Ferraro) | 500 rifles |

| 16th Inf Bn (Maj Vandiol) | 500 rifles |

| Attached: | |

| 3rd Native Bn (LtCol Galliano) | 1,150 rifles |

| ‘Quick-Firing Gun Brigade’ (Col De Rosa):* | |

| 1st QF Bty (Capt Aragno) | 6 guns |

| 2nd QF Bty (Capt Mangia) | 6 guns |

| Engineer half-company | 70 rifles |

| Totals: | 4,150 rifles, 12 ‘quick-firers’ |

| Grand totals: | 14,519 rifles, 44 guns, 12 ‘quick-firers’ |

| * Note: It is unclear from the sources whether ‘quick-firers’ refers to mountain guns or some kind of automatic weapons. | |

Artillery

At Adowa the Italians had 56 Type 75B light mountain guns organized into ten batteries. These 75mm brass-barrelled breech-loaders fired either high explosive or shrapnel shells fused for air burst or impact, and also had a canister round. They had an effective range of 4,200 yards, and were well-suited for campaigning in the Horn of Africa; they could be disassembled easily, with the barrel, wheels, trail, and ammunition packed onto four mules. Their drawback was that they were a carriage-recoil piece (rather than having recoiling barrels), so they had to be laid again after each shot. At Adowa they proved effective in the early stages of the battle, but were later silenced by Ethiopian ‘pom-poms’, which had greater accurate range. While a number of Italian ‘home guard’ (reservist) crews were shipped out with the 1896 reinforcements, most crews were ascari from the Sudan. A battery officially consisted of four Italian officers, 11 Italian NCOs or gunners, and 163 ascari serving five or six guns, but in the field a ‘battery’ could be as small as three guns.

It is unclear whether the Italians had automatic weapons at Adowa, although photos show Gardner machine guns in Eritrea. There are numerous references to two batteries of ‘quick-firers’ in Ellena’s reserve, but at that date this Italian term could refer to either conventional pieces or automatic weapons. While the reference to 56 guns may thus refer to 44 mountain guns and 12 automatic weapons, the latter, if present, were in any case not brought into use until the Italians had already been routed.

2 With a bolt-action magazine rifle, the firer lifts, pulls back, then pushes forwards and down the handle of a sliding cylindrical bolt at the breech; this mechanically ejects the empty cartidge case, feeds a new round into the chamber, and re-cocks the action. The Remington ‘rolling block’ system requires him to cock a big external hammer, then grip a small protruding thumb-pad to rotate a breechblock backwards; this jerks back a section of the chamber lip, half-ejecting the old cartridge, which he then pulls out with his fingers and replaces with a new round, before closing the re-cocked action once more.