Chapter 3

Don’t Believe Everything You Think

In This Chapter

Distinguishing Taoist myth from reality

Distinguishing Taoist myth from reality

Exploring the unexpected in Chinese religion

Exploring the unexpected in Chinese religion

Rethinking the relationship between religion and belief

Rethinking the relationship between religion and belief

Sometimes, the biggest barrier to getting something right is what you already know about it, or what you think you know about it because you’ve heard it repeated in many places, so many different times, and on good authority. And that’s especially true for Taoism. Because most people would be pretty hard-pressed to find Taoist neighbors, Taoist co-workers, or Taoist classmates to correct the record, textbooks, websites, and plain old word-of-mouth have all been pretty much free to define Taoism as they pleased, and no one was around to tell them they got it wrong. And I’m sure you know that once something goes viral, whether on the Internet or in ordinary chatter, it can be pretty hard to stuff the genie back in the bottle. How many times have you heard the baloney about the Great Wall of China being visible from space, or even the moon? Ironically, that one was going around decades before humans ever made it into space.

But it’s not just preconceived notions about Taoism that can get in the way; it can also be preconceived notions about religion itself. For obvious reasons, people are likely to be most familiar with their own traditions, and they often assume that what’s important in or true of their own traditions are important in and true of others. When this happens, it’s usually a lot more subtle than just mixing up the doctrine, like Christians mistakenly thinking Jews accept the divinity of Christ. And it’s those subtleties that often cause the biggest problems.

In this chapter, I address some of today’s stubborn misconceptions about Taoism, as well as certain misconceptions about religion that have a habit of getting in the way of understanding Taoism. Here, you see how we can debunk the single most popular and enduring Western myth about Taoism, become familiar with some unexpected characteristics of Chinese religion in general, and get to try on for size a totally different way of thinking about religion.

Debunking the Main Myth about Taoism

So, what is this dominant myth about Taoism that has been feeding us all these misconceptions and mistaken impressions? It’s one that deals with the origins of the tradition and the relationship between so-called “philosophical Taoism” and so-called “religious Taoism” (see Chapter 2), and it actually goes back at least a century. Most people who have believed and passed along the myth have almost always done so with sincere intentions and a genuine interest in the subject, unaware that this particular interpretation of Taoism employed a kind of loosey-goosey understanding of history and, unfortunately, passed along the religious biases of the people who first created the myth.

It’s really quite astonishing how badly this myth has mucked up the story of Taoism. In this section, I fill you in on all the important parts of this myth, explain the odd combination of circumstances that produced it, and show you how profoundly this has affected almost everything that Western sources — at least those not written by egghead scholars — regularly say about Taoism.

A pure teaching corrupted by superstition and religious opportunists

The main myths about Taoism are that there is a “real” Taoism, that it’s easy to point to what that real Taoism is, and that all other types of Taoism can be understood in relation to that real Taoism. So, what is this real Taoism? It can be broken down as follows:

Lao Tzu founded Taoism in the 6th century b.c.e. when he wrote the Tao Te Ching.

Lao Tzu founded Taoism in the 6th century b.c.e. when he wrote the Tao Te Ching.

Lao Tzu had several disciples or followers, most notably Chuang Tzu, who continued and spread his teachings. The Tao Te Ching and the Chuang Tzu are the two most important books of Taoism.

Lao Tzu had several disciples or followers, most notably Chuang Tzu, who continued and spread his teachings. The Tao Te Ching and the Chuang Tzu are the two most important books of Taoism.

The Taoism of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu celebrates and encourages a mystical state of naturalness, which anyone can pursue without gods, rituals, scriptures, or any of the other trappings of organized religion.

The Taoism of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu celebrates and encourages a mystical state of naturalness, which anyone can pursue without gods, rituals, scriptures, or any of the other trappings of organized religion.

This religion of mysticism and naturalness is one of China’s three religions, next to Confucianism and Buddhism. It’s especially at odds with Confucianism.

This religion of mysticism and naturalness is one of China’s three religions, next to Confucianism and Buddhism. It’s especially at odds with Confucianism.

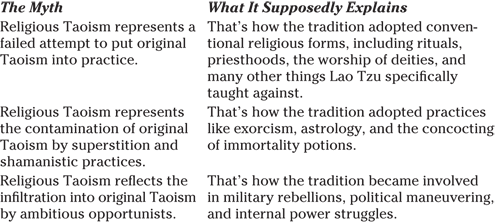

An almost secondary byproduct of this thinking is an acknowledgment that there is some kind of institutional religion in China that calls itself Taoism, but that it isn’t as important or as interesting as the pure Taoist philosophy of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu. Often, this myth incorporates an even more explicit dismissal of “institutional,” “organized,” or “church” Taoism, which it sees as a pale imitation of the “original” Taoism. You may hear any or all of the following statements about this kind of Taoism, though they basically spin variations on the same theme:

All these myths share the assumption that religious Taoism is a later, imperfect, version of some original Taoism, whether a misinterpretation, a corruption, or a usurpation of Lao Tzu’s pure, timeless, and wise philosophy. However cool you may find alchemy, shamans communicating with spirits, and rituals to guarantee safe passage of the dead, these are all additions to and distortions of the real deal.

Now don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu were not immensely important; the classical texts really did alter China’s philosophical world in breathtaking ways. But I am saying that focusing on them exclusively would be like talking about Christianity without any mention of church history or the Vatican, of Augustine or Thomas Aquinas, of the medieval Christian mystics, of the Inquisition or the Crusades, of the Protestant Reformation, or of Mother Teresa and Martin Luther King, Jr. In short, there’s a whole lot of other important Taoist stuff, too.

This myth is so pervasive that it’s common for reputable world religion textbooks to omit religious Taoism altogether, which then perpetuates the misconception for yet another generation. That’s why if you Google Lao Tzu, you’ll find literally millions of results; but try Googling the Way of the Celestial Masters, which is the oldest established sect of religious Taoism, and you’ll be lucky to find a hundredth as many results. Google the Tao Te Ching, and you’re back up in the millions, but Google the Kan-ying P’ian or some other important text in the Taoist Canon, and you’re back down in the thousands.

A Victorian spin on Taoism and Chinese religion

So, where did this myth of a pure Taoist philosophy and a corrupt Taoist religion come from? Back in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Americans and Europeans didn’t have too many ways to learn about China. Few resources were available for learning Chinese language or culture, overseas travel was difficult and prohibitively expensive, and China itself was so torn apart by rebellions and the collapse of its final dynasty that few Westerners (other than diplomats) had much incentive to travel there in order to learn about it. But there was, however, one group of people who felt driven to live among the Chinese and learn about their civilization: Christian missionaries. Most people today have no idea how thoroughly missionaries dominated and defined the first generations of Western scholarship about China. Most of what we first learned about Taoism, we learned from them.

Some people may imagine missionaries as arrogant colonialists who barge into foreign countries for the sole purpose of “converting the heathens.” But more often than not, missionaries historically recognized the importance of learning the cultures of the countries they visited, respecting their native traditions, and establishing personal relationships with those whom they recognized as local religious and community leaders. One scholar-missionary who followed this pattern was James Legge, a Scottish member of the Congregationalist church. Legge contributed numerous translations of Chinese texts to what was then a groundbreaking achievement, a 50-volume series titled the Sacred Books of the East, which took more than 30 years to complete. As it turns out, through his many translations and other books he wrote about China, Legge probably did more to define the Western picture of Taoism than did any other single person.

Legge recognized Confucian intellectuals who worked in public service as important religious and cultural leaders, and he relied on them for much of his information. Unfortunately, these Confucian scholars, who wanted both to preserve traditional Chinese culture and accommodate challenges from the West, were invested in the idea that cream-of-the-crop Chinese religion was philosophically sophisticated and didn’t include any silly “superstitions.” They told Legge that Taoism as practiced was basically a hoax perpetrated on the illiterate and “unenlightened” masses and that it had degraded the original Taoism of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu.

But why did Legge buy this without a fight? Because this explanation made perfect sense to a Protestant missionary who was conservative, somber, and Victorian. Legge had already thought that Catholicism was a vulgar degradation of Protestant Christianity, and he had no trouble seeing Taoism, with its priests and over-the-top rituals, as just another funky degradation of an originally good idea. As far as Legge was concerned, just as people should identify “real” Christianity with Protestant theology and simply dismiss Catholic excesses, so, too, people should identify “real” Taoism with the early Taoist philosophy and simply dismiss Taoist “superstitions.”

A perfect fit for spiritual seekers

Even though many scholars know that the myth of a pure philosophical Taoism is not accurate, and they’ve been able to trace its origins to the missionary scholars of the 19th century, you may be wondering why the myth still persists. Yes, the Taoism specialists don’t mind us having our fun with Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu, but they do keep barking reminders that we should hurry up and get on with the rest of the story. So, why is it so hard to fix this? Why do people still hold on to the fascination with Taoist philosophy and pay lip service to Taoist religious practice?

In large part, it’s for exactly the same reason that James Legge bought the myth in the first place. Not the anti-Catholic part, but the part about how much sense it made for him and how compelling he found the philosophy itself. No matter how you slice it, ever since the first translations of the Tao Te Ching made it into English and other Western languages, enthusiastic audiences have found Taoism intriguing, stimulating, and captivating. People just love this stuff, and with good reason! The legendary story of Lao Tzu’s birth and composition of the Tao Te Ching, the mysterious principle of the Tao, the paradoxical wisdom that “the sage does nothing, and yet nothing is left undone” — these have all touched the Western spiritual imagination in some profound way. And even if you don’t really know much of anything about Chinese culture, what spiritual seeker can resist the image of the Taoist sage, a Chinese version of Henry David Thoreau, who warns against social obligations, technology, and the rat race, and encourages us to seek our own spiritual paradise through simplicity and naturalism?

That may explain the continuing fascination with Taoist philosophy, but what about the last 2,000 years of Taoist religion? Why do so many people still treat that as Taoism’s less interesting younger brother? The reasons for this can best be summarized as follows:

Accessibility: Taoist religion can be incredibly difficult to understand, with all those secretive practices, shadowy deities, and hundreds of texts that have never been translated. Taoists can also be very protective of their rituals and teachings, so they’re in no hurry to make it any easier.

Accessibility: Taoist religion can be incredibly difficult to understand, with all those secretive practices, shadowy deities, and hundreds of texts that have never been translated. Taoists can also be very protective of their rituals and teachings, so they’re in no hurry to make it any easier.

Context: Although people have easily found timeless and universal messages in the classical texts, the Taoist religion has from the beginning been utterly Chinese through and through. A lot of Westerners just don’t relate as easily to practices that are tied so closely to Chinese geography, historical figures, and local community interests.

Context: Although people have easily found timeless and universal messages in the classical texts, the Taoist religion has from the beginning been utterly Chinese through and through. A lot of Westerners just don’t relate as easily to practices that are tied so closely to Chinese geography, historical figures, and local community interests.

The “cool” factor: Once you learn about the actual practice of Taoism, you may be disappointed to learn that it includes a lot of things — like ordination certificates, rigid rules of morality, and public confessions of sins — that make it seem less exotic. A real-life Taoist monk can sometimes seem less magical than an imaginary, idealized Taoist sage.

The “cool” factor: Once you learn about the actual practice of Taoism, you may be disappointed to learn that it includes a lot of things — like ordination certificates, rigid rules of morality, and public confessions of sins — that make it seem less exotic. A real-life Taoist monk can sometimes seem less magical than an imaginary, idealized Taoist sage.

The ivory tower: As much as I hate to admit it, experts in Chinese religion haven’t always done a good job of explaining why Taoist religion is important or why we should find it interesting. Most of the time, they make the conversation so technical that only people with the same level of training can follow what they’re talking about.

The ivory tower: As much as I hate to admit it, experts in Chinese religion haven’t always done a good job of explaining why Taoist religion is important or why we should find it interesting. Most of the time, they make the conversation so technical that only people with the same level of training can follow what they’re talking about.

Getting Oriented to Chinese Religion

Although specific dominant myths about Taoism haunt the Internet, it’s an offbeat-enough subject that you may never have actually encountered those myths and aren’t approaching Taoism with any of those assumptions. It’s actually a lot harder with assumptions about religion in general, however. Because almost everyone is familiar with at least something about religion — even the most hard-core atheists must bump into religious people every now and then — you may have certain expectations about what the major world religions are all about, what kinds of questions they all deal with, and what particular features they all share. But Chinese religion has a habit of throwing a monkey wrench into many of those expectations.

In this section, I orient you to some important, but probably unexpected, features of Chinese religion, which should make Taoism a whole lot less mysterious. I explain how an exercise with a peculiar logic problem can tell you boatloads about Chinese religion, what it means when people say that Chinese religion is “syncretic,” what particular place Chinese religion gives to gods and various spirits, and how certain religious practices like divination function in day-to-day Chinese religious life.

Circles, triangles, and thinking concretely

You can gain some unexpected insight into some of the basic characteristics of Chinese religion by trying an unlikely exercise. Do you have an idea that things like math, logic, and geometry are pretty universal? If so (or even if not), take a stab at the following logic problem:

If all circles are large, and if all triangles are circles, then are all triangles large?

What did you answer? Did you say yes or no? Or were you afraid to take a crack at it because you figured I was trying to trick you?

My guess is that you did something like this: Okay, let’s assume the first part, that circles are large. Now let’s look at triangles, which are now somehow circles. Don’t ask me how a triangle could be a circle — these kinds of problems always have silly stuff like that. In any case, those triangles, which are now circles, have to be large, because we already know that circles are large, right? So, yes, if all circles are large, and if all triangles are circles, then all triangles must indeed be large.

And if you did it more or less like that, you’re right in line with the more than 80 percent of Americans who answered a similar question that way in a study done several years ago. But incredibly, when the researchers posed the question in Chinese to a sampling of educated people from Taiwan, the vast majority either answered no or complained that there were just too many things about the question that didn’t make sense. How could a triangle be a circle? If it becomes a circle, is it not a triangle anymore? And so on. As a result, most of them just ignored such a “counter-factual” statement (the part about triangles being circles) and then trusted their own experience and judgment, which told them that no, not all triangles are large.

Why did this happen, and what’s the point here? Most Americans in the test — and probably you, too — tended to approach the problem abstractly, to do it as a kind of mathematical puzzle. If all A is B, and all B is C, then all A is C, a type of sequence that experts in logic call a syllogism. But most of the Chinese — and maybe you, too — didn’t do it that way, not because they lacked any ability to think abstractly, but because they naturally approached the problem concretely, thinking of it in terms of real-life situations and experiences. And in real life, no matter how you draw them, triangles aren’t circles, and not all triangles are large.

What are some ways a concrete orientation can influence how religion develops? For starters, here are just a few:

What matters is the “here and now.” Chinese religion generally addresses the concerns of this world and of this lifetime. Even when it does get into stuff like heady metaphysics or speculation about what happens after death, the emphasis is almost always on what that means for us here and now, for the responsibilities you have and for the choices you can make in your own life.

What matters is the “here and now.” Chinese religion generally addresses the concerns of this world and of this lifetime. Even when it does get into stuff like heady metaphysics or speculation about what happens after death, the emphasis is almost always on what that means for us here and now, for the responsibilities you have and for the choices you can make in your own life.

The universe you see is the universe you get. Chinese religion treats the universe as a self-sufficient organism, where all the parts relate to one another in complicated ways. Whenever it introduces any spirits or deities, these are always treated as vital parts of that universe. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all think of an omnipotent god who stands somehow separate from existence and creates the universe out of nothing. You won’t find that in Chinese religion.

The universe you see is the universe you get. Chinese religion treats the universe as a self-sufficient organism, where all the parts relate to one another in complicated ways. Whenever it introduces any spirits or deities, these are always treated as vital parts of that universe. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all think of an omnipotent god who stands somehow separate from existence and creates the universe out of nothing. You won’t find that in Chinese religion.

It has to matter. Chinese religion always has a practical component, even if it isn’t always obvious to someone watching it from the outside. You probably can’t expect the Chinese to participate in religious activities unless they expect them to have some practical effects for themselves, for their families or communities, or even for the whole universe.

It has to matter. Chinese religion always has a practical component, even if it isn’t always obvious to someone watching it from the outside. You probably can’t expect the Chinese to participate in religious activities unless they expect them to have some practical effects for themselves, for their families or communities, or even for the whole universe.

Religious syncretism: One from Column A, two from Column B

One of the most interesting aspects of Chinese religion is the way the Chinese make use of what more than one individual tradition has to offer. In the West, even though interfaith families are becoming more and more common, most people identify themselves (if they identify at all) exclusively with one religious affiliation. By and large, you’ll find people who say they’re Jewish or Christian or Muslim or Buddhist, for example. And even if they’re inclined to “borrow” from other traditions — some Jews celebrate Christmas, some Christians practice Buddhist meditation, and some Buddhists read Muslim texts — most still maintain one primary religious identification and are fully aware when they’re crossing into someone else’s religious territory. And of course, many people who think of the religions as completely separate may find it irreverent or just feel uncomfortable when others try to mix and match.

Apart from religious “professionals” (like priests), Chinese seldom identify with only one religion. Many textbooks say that there are three religions in China — Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism — and that most Chinese practice all three, or some combination of the three. But this is still not quite on the money. Here’s a better way to understand this: The Chinese have had some distinct, recognizable ways of being religious, and those very often involve using or participating in whatever available resources best serve their religious needs. If they visit a Taoist temple, they don’t suddenly think of themselves as “being Taoists” or “practicing Taoism.” Likewise, they don’t think of themselves as “being Confucian” when they learn a traditional Confucian art like calligraphy, or “being Buddhist” when they read Buddhist morality texts to their children. They’re simply being Chinese, and they don’t “belong” to Confucianism, Taoism, or Buddhism. If anything, Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism belong to them!

What does Chinese religious syncretism look like? As you can probably imagine, there isn’t any single blueprint, but there are some patterns you’ll find more than others. Here are a couple common syncretic practices:

Temple worship: People may visit both Taoist and Buddhist temples to make offerings to their respective deities without feeling that they’re “changing sides.” They may even schedule these trips on the same day, which is especially easy to do when the temples are in close proximity to each other. Some local temples are not affiliated with either Taoism or Buddhism but house deities from both.

Temple worship: People may visit both Taoist and Buddhist temples to make offerings to their respective deities without feeling that they’re “changing sides.” They may even schedule these trips on the same day, which is especially easy to do when the temples are in close proximity to each other. Some local temples are not affiliated with either Taoism or Buddhism but house deities from both.

Holidays and public celebrations: Much as they do with temple worship, Chinese generally don’t give a second thought to celebrating holidays that originated with different traditions. Public holidays that are not exactly religious but might have some small religious component or overtones — Chinese New Year is the most obvious example — may have events where Buddhist and Taoist priests both preside.

Holidays and public celebrations: Much as they do with temple worship, Chinese generally don’t give a second thought to celebrating holidays that originated with different traditions. Public holidays that are not exactly religious but might have some small religious component or overtones — Chinese New Year is the most obvious example — may have events where Buddhist and Taoist priests both preside.

Deities, spirits, and the concern for concrete effects

Chinese religion has always included many deities, spirits, ghosts, and other beings whose presence isn’t obvious to the naked eye. If you want to know every deity the Chinese have ever honored, you’d probably need a scorecard or the kind of computer program that keeps track of complicated family trees. But for the most part, you can keep track of them by sorting them into the following categories:

A high god: The Chinese name T’ien translates literally as “Heaven” or “the Heavens.” This deity is more impersonal than anthropomorphic, which is to say that it doesn’t really possess human features. Heaven is associated with things like fate, cosmic order, and the protection of a righteous ruling regime.

A high god: The Chinese name T’ien translates literally as “Heaven” or “the Heavens.” This deity is more impersonal than anthropomorphic, which is to say that it doesn’t really possess human features. Heaven is associated with things like fate, cosmic order, and the protection of a righteous ruling regime.

Sectarian gods and goddesses: These are deities that originated from particular religious traditions, like the Buddha named Mi-lo (that’s the round, smiling guy you may see on the counter in Chinese restaurants), a compassionate female Buddhist goddess named Kuan-yin, or Hsi Wang Mu, the Taoist Queen Mother of the West.

Sectarian gods and goddesses: These are deities that originated from particular religious traditions, like the Buddha named Mi-lo (that’s the round, smiling guy you may see on the counter in Chinese restaurants), a compassionate female Buddhist goddess named Kuan-yin, or Hsi Wang Mu, the Taoist Queen Mother of the West.

Functional and local deities: These deities fulfill particular purposes (like healing, agriculture, or protecting travelers) or occupy and protect particular regions. Rural villages would often have their own earth gods, and individual families to this day may still have images of kitchen gods in their homes.

Functional and local deities: These deities fulfill particular purposes (like healing, agriculture, or protecting travelers) or occupy and protect particular regions. Rural villages would often have their own earth gods, and individual families to this day may still have images of kitchen gods in their homes.

Deified historical or legendary figures: Most deities are thought to have once been people, who for one reason or another earned “promotions” to god status over time. The best known of these is Ma Tzu, an ordinary fisherman’s daughter from the 10th century, who is now honored as the goddess of the sea.

Deified historical or legendary figures: Most deities are thought to have once been people, who for one reason or another earned “promotions” to god status over time. The best known of these is Ma Tzu, an ordinary fisherman’s daughter from the 10th century, who is now honored as the goddess of the sea.

Spirits of ancestors: Your parents and grandparents continue to deserve your respect, even after they die. The Chinese holiday called Ch’ing Ming is a time when people visit their family cemeteries, lighting firecrackers, burning incense, and making other offerings to their ancestors. Spirits of the dead who have no descendants or have been forgotten by their descendants turn into unhappy, restless ghosts.

Spirits of ancestors: Your parents and grandparents continue to deserve your respect, even after they die. The Chinese holiday called Ch’ing Ming is a time when people visit their family cemeteries, lighting firecrackers, burning incense, and making other offerings to their ancestors. Spirits of the dead who have no descendants or have been forgotten by their descendants turn into unhappy, restless ghosts.

So, which of these deities are the most important in Chinese practice? You may be imagining that the most powerful ones or the ones commanding the most territory get the most attention, but actually the exact opposite is true. Think of it this way: The most powerful person in the country is (depending on which country) the president, the prime minister, or maybe the chief justice of the highest court. So, naturally, whenever you need something from the government — like getting your dog released from the pound or acquiring a building permit — you get on the phone and call the president, right? Well, no. Instead, you call the local official — the animal control officer or the director of planning and zoning, whoever has the direct authority to take care of your particular problem. The Chinese think of their deities much the same way, as though they were organized like a government bureaucracy. People pay less attention to the higher and more remote figures and more attention to the ones that influence their immediate concerns. The Chinese worship deities based not on their overall importance, but on their ling, their “spiritual efficacy,” the quality the deities possess to bring concrete effects into people’s lives.

Because the Chinese measure deities by their efficacy, they may have some religious habits that strike non-Chinese as strange, until you remember that they tend to employ religious resources that have a practical, concrete value. For example, if they think that a deity isn’t “doing its job,” whoever is in the position of authority to make such decisions can simply replace that deity with a different spirit who’s more up to the task. The relationship between humans and deities is mutual; each side has its obligations to fulfill, and even deities are held accountable if they don’t fulfill theirs.

Divination and the practical side of religion

If you understood that all sorts of gods, spirits, and other non-obvious beings inhabit our world, and if you had the idea that those beings can influence our lives, you’d probably want to devote some time and attention to figuring out exactly what their intentions are and what they want from us. Christians and Jews usually find those answers through the Bible, through prayer, or perhaps through conversations with clergy or other religious counselors. One important way the Chinese have traditionally sought to answer those questions is through various forms of divination.

In its most basic sense, divination refers to predicting the future or figuring out things we can’t normally see, through some kind of specialized practice. Reading tea leaves, telling someone’s fortune, palm reading, and even the Magic 8-Ball are simple forms of divination. You can even think of interpreting nice weather as a sign that God wants you to go the beach as a kind of divination. Here are several important types of Chinese divination, many of which the Chinese (and others) still practice today.

Oracle bones: In ancient times, experts would write or carve questions on animal bones, heat them, and then interpret the cracks on the bones as answers to the questions. Archaeologists discovered these bones early in the 20th century and learned a lot about ancient China through them.

Oracle bones: In ancient times, experts would write or carve questions on animal bones, heat them, and then interpret the cracks on the bones as answers to the questions. Archaeologists discovered these bones early in the 20th century and learned a lot about ancient China through them.

Feng-shui: This term literally translates as “wind and water,” and it refers to ways of reading the physical environment in order to decide the best location to place a dwelling, like a house, school, or cemetery. Chinese also employ feng-shui to determine changes they should make to an existing dwelling, like where to place furniture or hang a mirror.

Feng-shui: This term literally translates as “wind and water,” and it refers to ways of reading the physical environment in order to decide the best location to place a dwelling, like a house, school, or cemetery. Chinese also employ feng-shui to determine changes they should make to an existing dwelling, like where to place furniture or hang a mirror.

The Book of Change (I Ching): The Book of Change is a manual that contains a divination system, based on different combinations of yin and yang. Both Taoism and Confucianism regard it as a classic, and many people find a lot of philosophical and cosmological significance in the commentaries on it.

The Book of Change (I Ching): The Book of Change is a manual that contains a divination system, based on different combinations of yin and yang. Both Taoism and Confucianism regard it as a classic, and many people find a lot of philosophical and cosmological significance in the commentaries on it.

Spirit writing: This refers to several different methods of suspending racks or trays so that a stick or wand, which is presumably occupied by a specific spirit, can trace Chinese characters in sand or on a flat surface. This is also sometimes called “automatic writing.”

Spirit writing: This refers to several different methods of suspending racks or trays so that a stick or wand, which is presumably occupied by a specific spirit, can trace Chinese characters in sand or on a flat surface. This is also sometimes called “automatic writing.”

Oracle blocks: This is a very common practice at temples and shrines, where someone asks a yes-or-no question (presumably of the appropriate deity) and tosses a pair of blocks that are round on one side and flat on the other. Landing one round block and one flat block up usually means yes, while the other combinations normally mean no (though there are other interpretations as well).

Oracle blocks: This is a very common practice at temples and shrines, where someone asks a yes-or-no question (presumably of the appropriate deity) and tosses a pair of blocks that are round on one side and flat on the other. Landing one round block and one flat block up usually means yes, while the other combinations normally mean no (though there are other interpretations as well).

Most of these methods require some level of expertise, either to perform the divination or interpret the information, and that helps explain why there are professional diviners and hereditary priests in China. Critics tend to regard all forms of divination as unscientific or pseudo-science, in part because they don’t really withstand scientific testing, but also because the “experts” guard their territory closely and don’t normally explain how it works. In spite of this, many Chinese take these practices quite seriously. For instance, recent surveys indicate that a surprisingly large number of Chinese would consider using feng-shui before making certain important decisions. Some people have speculated that feng-shui persists among the Chinese because their basic worldview allows for the possibility that different things sometimes connect to one another in ways that are not immediately apparent. But it may be simpler than that. Many people get their first chance to employ feng-shui at some kind of crucial moment of transition in their lives, like when a newly married couple has to figure out where to build their first home or a grieving son has to decide where to bury his father. And often during those crucial moments, it can feel safer and more comforting to choose the traditional option. There’s an old adage that people all over the world are inclined to “get religion” during three momentous events: births, marriages, and deaths — or, to put it more playfully, when you’re hatched, matched, and dispatched.

Believe It or Not, It’s Not about Belief

One last aspect of Chinese religion that can be so difficult for Western audiences to grasp is that belief in religious doctrine does not hold a particularly important place. This might strike you as pretty curious. After all, when you want to know about other people’s religion, isn’t one of the first questions you ask, “What do they believe?”

One reason that so many people are in the habit of thinking of religion that way is that Western traditions, particularly modern Christianity, emphasize things like getting the doctrine right or making clear that you believe in God’s existence. This implies that the act of believing in some way determines your fate, or that it actually matters to God what you believe.

But the Chinese don’t really think of their practices in terms of belief. If you ask a Chinese why he or she burns incense at an ancestor’s grave, that person is not likely to say, “Because I believe that my ancestor’s spirit is still alive, that it likes the smell of incense, and that I’m going to have bad luck if I don’t do it.” You’re more likely to hear an answer like “To show respect,” “To fulfill my family duties,” or “To repay the kindness my grandfather showed me when I was younger.” In other words, there’s no special virtue in believing; there’s only virtue in doing the right thing with sincere feelings. What’s more, the spirit truly doesn’t care if you believe it exists; it cares that you don’t forget it and continue to tend its grave respectfully.

Try thinking of it this way: You’re taking a college course in which your teacher requires that you attend class regularly, keep up on the assigned readings, and take four tests in order to pass. But she never requires that you believe she exists! How would you feel if I held up your exams as evidence that you “believed in” your professor? Most likely, you never even gave that matter a second thought, and that would be kind of a funny conclusion. So, try to remember that even when Chinese are discussing religious doctrine, it’s not for the purpose of dictating what someone should believe; it’s for the purpose of making clear how you should understand the world and what that means for how you should act in it.

The biggest problem with all this —

The biggest problem with all this —  The pervasive idea that real Taoism is the original teaching of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu is simply not true. No other stubborn fallacy has done more to obstruct Western attempts to understand Taoism and Chinese religion.

The pervasive idea that real Taoism is the original teaching of Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu is simply not true. No other stubborn fallacy has done more to obstruct Western attempts to understand Taoism and Chinese religion.