TWO

Biblical Interpretation

Moses received Torah from Sinai and transmitted it to Joshua, and Joshua [transmitted it] to the Elders, and the Elders [transmitted it] to the Prophets, and the Prophets transmitted it to the Men of the Great Assembly. (m. Avot 1:1)

In this famous text, Moses’ biblical ascent of Mount Sinai in Exodus 19 forms the first link in an unbroken chain of transmission: the divine wisdom imparted to Moses is transmitted to Joshua; who passes it on to the Elders (see Joshua 24:31); who in turn pass it on to the Prophets; who pass it on to the Men of the Great Assembly. This latter group is understood to be a collective of wise men who lived during the Second Temple period and preserved traditions in order to transmit them to the final link in the chain: the Rabbis.

What rabbinic literature claims to represent, then, is an authentic tradition that dates back to God’s Revelation on Mount Sinai. For the Rabbis, that moment of Revelation revealed not one but two Torahs: the Written Torah and the Oral Torah. The Written Torah (Hebrew torah sh-bikhtav) consists of the Hebrew Bible: a bound text composed and edited by God, an inerrant and intentional author. The Oral Torah (Hebrew torah sh-be‘al peh), on the other hand, is a process: it is a series of continuously revealed texts that interpret, expand, augment, and update the Written Torah. To use modern technological terms: all of Torah was revealed at Mount Sinai, but the Written Torah was downloaded and exists in hard copy, while the Oral Torah was backed up to The Cloud (literally and figuratively), to be downloaded via the rabbinic process of debate whenever certain files are needed.

Torah encompasses all aspects of life—from civil and criminal law, to ritual and ethical practices; from how to pray, to how to go to the bathroom. To quote another famous rabbinic dictum from the same tractate:

Ben Bag Bag said: Turn it and turn it [again], for everything is in it. (m. Avot 5:22)

If you search and cannot find what you are looking for, you can always download it from The Cloud with Oral Torah.

One common enterprise in which Oral Torah engages is the explication of Written Torah. Reading through the Hebrew Bible, one encounters many instances that complicate and challenge the claim that the Written Torah was composed by a divine author. One passage contradicts another. A word is misspelled. Sometimes words or phrases seem to be either omitted or added in the wrong place. The organization can appear haphazard. And sometimes, the meaning of a given text is simply opaque. In order to address these matters, the Rabbis developed midrash (from a Hebrew root meaning “to investigate”), a hermeneutical practice based on certain assumptions and governed by certain rules (see Bakhos 2006; 2009). For example, if a word is misspelled in the Hebrew Bible, that is because God meant to misspell it, and not because a human author did not use spell check. And if God used a specific word in Leviticus and then that same word appears again in Deuteronomy, God meant to do so in order to authorize a Rabbi to derive via midrash a principle from that wording.

In this chapter, we explore what texts about beverages can teach us about the presumptions and principles that govern rabbinic biblical interpretation. Though I am unable to cover every aspect of midrash herein, the fascinating passages that follow—including tales of human combustion and Freudian slips—provide a survey of the main contours of rabbinic exegesis. And, as we shall soon learn, this enterprise will put a smile on your face.

“WORDS OF TORAH ARE SYMBOLIZED BY WATER”: DRINKING DIVINE WISDOM

Without water, there is no life. Summarizing the science behind the human biological need for water, Andrew Smith notes:

In its purest form, water has no calories, proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, or minerals, yet it is the most important nutrient for humans. It is the universal solvent, and many substances, such as minerals (calcium, sodium), gases (oxygen, carbon dioxide), and nutrients (B vitamins and vitamin C), are easily dissolved in it; water is an essential part of the human metabolic process. Water performs a variety of functions in the body. It helps carry nutrients to cells, removes waste, and is vital to maintaining the body’s temperature. Without regular infusions of water—which for humans should not exceed three days—life ends. (Smith 2013, 1)

Though the Rabbis do not speak in the same scientific terms, they display awareness of the necessity for access to drinking water. This vital need appears in a variety of contexts. For example, in regard to civil law, the Rabbis note that, while pits dug in various locations may belong to the general public or to private individuals, “Streams and flowing springs, behold, they belong to everyone” (t. Bava Qamma 6:15). If water is life, then every life needs access to water.

The vital need for water marks this liquid as a prime candidate for symbolic interpretation. Water is often compared to something else that the Rabbis deem essential for existence: Torah. Water ensures physical survival in This World (Hebrew ‘olam ha-zeh), the present, lived reality; and Torah ensures spiritual survival both in This World and in The World to Come (Hebrew ‘olam ha-ba’), a future time when the righteous receive their reward and the wicked get what they deserve. For example:

Why is man compared to “fish of the sea” [Habakkuk 1:14]? To teach you that just as fish of the sea die as soon as they are lifted onto dry land, so too men die as soon as they separate themselves from words of Torah and from the commandments. (b. Avodah Zarah 3b)

A man without Torah is like a fish without water. For this reason, the Rabbis often draw on water metaphors (as do early Christian monastics; see Bar-Asher Siegal 2013, 101–3).

To offer another example, this time from dry land: Exodus 15:22–26 recounts an incident where the Israelites, having fled slavery in Egypt, “went three days in the desert, and they did not find water” (Exodus 15:22). Three days without water is life-threatening. One commentary on this biblical text asserts:

“and they did not find water” [Exodus 15:22]: “Words of Torah are symbolized by water.” (Mekhilta d’Rabbi Ishmael Beshalah Vayassa 1; on this passage, see Boyarin 1994, 58–70)

Wandering in the desert, the Israelites are dying of thirst. This explains what follows in the biblical account, wherein the severely parched Israelites rebel against Moses. Though disapproved of, their actions are understandable, given their mortal need both for water and for spiritual “water.”

In particular, the Rabbis focus on the ability of water to be imbibed and to become embodied knowledge. They imagine water as embodied Wisdom that the body absorbs and incorporates in the simultaneous act of physical and spiritual digestion. To find an excellent example of this assertion, we return to the desert. Post-Exodus, why did God not lead the Israelites straight from Egypt into the Land of Israel? Why did they need to wander for forty years in the desert? It turns out there was a good reason for God making the Israelites roam around the desert:

The Holy One Blessed be He says: If I should bring the Israelites into the Land right now, each person would immediately take possession of a field or a vineyard, and they would neglect Torah. Rather, I will take them into the wilderness for forty years, that they might eat manna and drink well-water, so that Torah will be absorbed into their bodies. (Mekhilta d’Rabbi Ishmael Beshalah Vayehi 1; on this text, see Rosenblum 2010, 61–63)

Taking the direct route would have resulted in the Israelites settling too quickly into the Land of Israel. Instead, God had them take the (very!) scenic route. Along the way, they ate manna and drank well-water, both of which symbolize knowledge. After forty years of these constant acts of eating and drinking, the individual Israelite bodies and the corporate body of Israel had both literally and figuratively absorbed Torah. They were now ready to enter God’s promised land.

Thus far, we have learned that: (a) water and Torah are essential for survival; (b) there is “a widespread rabbinic tendency to describe Torah and its transmission through metaphors of nourishing sustaining liquids” (Belser 2015, 36), especially water; and (c) water and Torah are absorbed into the body, ontologically changing the drinker and imparting physical and spiritual vitamins and nutriment. While these assumptions are important, they still do not fully explain why I would begin a chapter on rabbinic biblical interpretation with a discussion of water. For this, we must turn to another text:

Another interpretation: “May my discourse come down as rain” [Deuteronomy 32:2]. Just as rains falls on trees and imparts its distinctive flavor into each and every one of them—the grapevine with its flavor, the olive tree with its flavor, the fig tree with its flavor—so too words of Torah are all one, but they comprise Written Torah and Oral Torah, [the latter of which includes] midrash, laws, and narratives. (Sifre Deuteronomy 306; my translation is influenced by Fraade 2012, 41–42; and 1991, 96–97)

In Deuteronomy 32, Moses delivers his final speech to the Israelites, including his hope that:

May my discourse come down as rain, my speech distill as the dew, like storm-showers on the grass, and rain-showers on the herb. (Deuteronomy 32:2)

As rain penetrates the ground and nourishes vegetation, Moses fervently desires that his words will penetrate the Israelites and nourish the seed he planted, so that it grows into a mighty (family) tree. In short, Moses hopes that his words are embodied and embodying water.

As the opening line of our text indicates (“Another interpretation”), this speech proved irresistible to the Rabbis, who offered numerous interpretations of this verse (e.g., Sifre Deuteronomy 306; b. Ta‘anit 7a). In our present text, the words of Moses are “understood to contain already the diverse forms of rabbinic Oral Torah, which despite their distinctive ‘tastes’ ‘are all one,’ that is, derive from a single divine source and revelatory event” (Fraade 2012, 42). Rain falls on the ground and imparts various flavors to various plants. The grape does not taste like the olive; and neither taste like the fig. But rain—whether a heavy downpour, a gentle mist, or the morning dew—all comes from a single source.

Torah is like rain. It comes from a single, divine source. God’s “rain” is divided into two types: Written Torah and Oral Torah (or, in the language used in this text, Scripture and Mishnah; Hebrew miqra’ and mishnah, respectively). Oral Torah is further subdivided into three distinct flavors: midrash, halakhot (“laws”), and haggadot (“narratives”). Like grapes, olives, and figs (clearly, the three-part example is not accidental), midrash, laws, and narratives are all different flavors nourished from a single source. The Torah-as-water metaphor therefore supports the entire rabbinic system: God gave Moses Torah—both Written and Oral. Like rain, Moses’ Torah nourished many types of plants/texts. But the key ingredient of all of these is God’s rain.

Water, the beverage that supports all animal and vegetal life, becomes the defining metaphor for rabbinic authority to interpret Scripture. For this reasons, students can say to their Rabbi:

We are all your students, and from your water we drink! (y. Sotah 3:4, 18d; y. Hagigah 1:1, 75d; b. Hagigah 3a; cf. b. Bava Metzi’a 84b)

Once (unilaterally) granted this authority, the Rabbis begin to develop a set of interpretative practices and presumptions. It is to some of these hermeneutical principles that we now turn.

“EVE MIXED WINE FOR ADAM”: WINE AND DIVINE EDITORSHIP OF THE HEBREW BIBLE

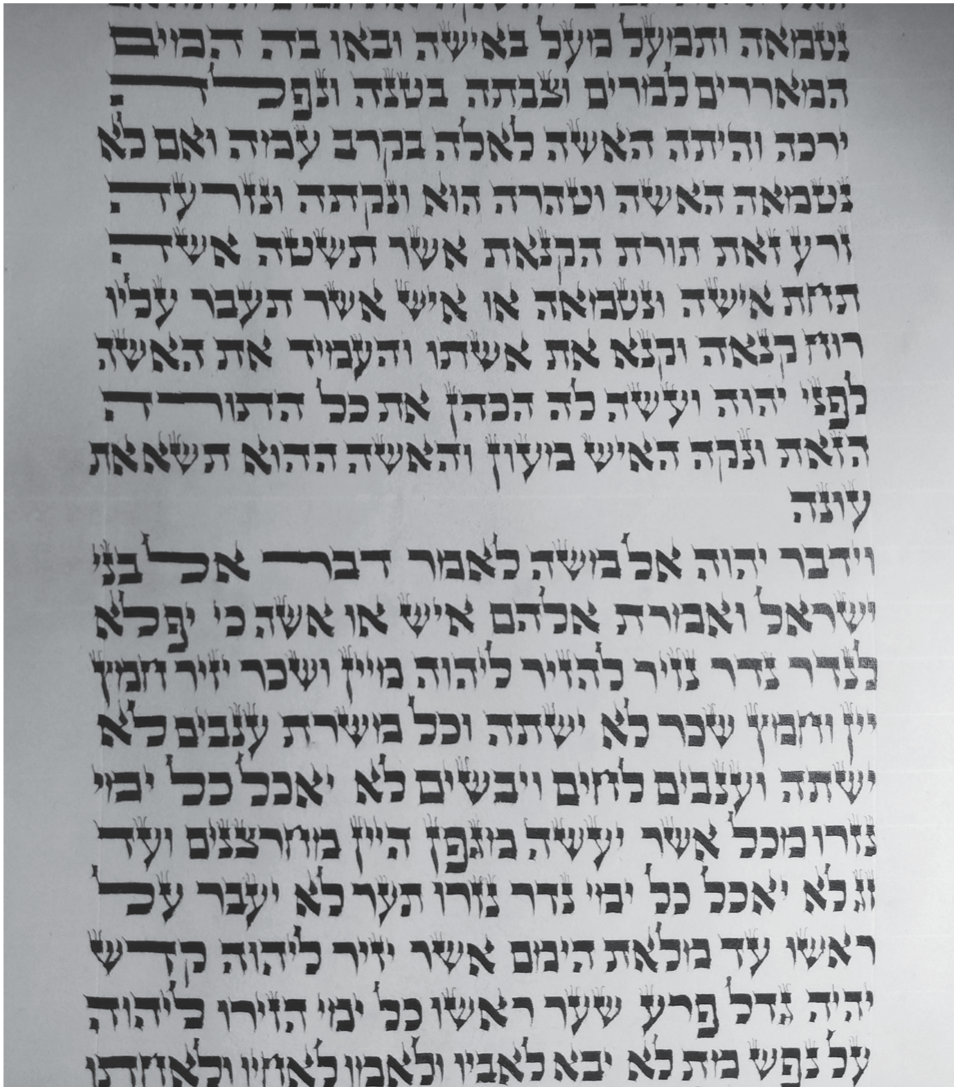

According to the Rabbis, God composed, edited, and dictated to Moses the entire Torah—including the various dots and crowns adorning the normative rabbinic Torah scroll (see the famous conversation on this topic between Moses and God on b. Menahot 29b; and fig. 1). Modern scholars attribute these marks to later rabbinic scribal communities, but the Rabbis understand this entire project to be concurrent with Revelation: the text was delivered as is.

Figure 1. Modern Torah scroll. The end of Numbers 5 and the beginning of Numbers 6. Photo: Dov Berger.

If that is the case, how then does one explain instances in which words seem to be misspelled? Or repeated? Or contradictory? On several occasions throughout this book, we discuss instances in which the Rabbis attempt to find meaning in various biblical texts. But here we grapple with an important issue: if God intended every letter to be written in the exact sequence in which it appears in the Torah scroll, that means that there is a reason why one text follows another. Each letter, word, verse, paragraph, chapter, and book is organized with a divine intentionality, which must be uncovered. And the process for that recovery is via midrash (see Sommer 2012, 64–69).

An excellent example of this interpretative process relates to rabbinic exposition of the relationship between Numbers 5 and 6. Numbers 5 spells out the biblical ritual by which a jealous husband accuses his wife of adultery (the sotah, Hebrew for “suspected adulteress”; discussed in detail in chapter 4), despite his lack of evidence that any transgression occurred. Immediately following this narrative, Numbers 6 examines the nazir, a layperson who voluntarily vows to abstain from certain practices, one of which is drinking any intoxicant, especially wine. (The most famous nazir in the Hebrew Bible is Samson, whose story can be found in Judges 13–16.) Why do these two texts appear side by side? Keeping in mind the rabbinic principle that God is an intentional and infallible editor, there must be something that can be learned from this organization. So what is that lesson? Over the course of several pages, Numbers Rabbah 10:1–4 answers this question. While I cannot cover the entirety of this text (which, in typical rabbinic style, includes several asides and additional, semi-related conversation), I focus here on four instances in which Numbers 5 and 6 are connected via one beverage: wine.

Throughout the various attempts to connect these two passages, a theme emerges: wine leads to transgressions; transgressions are particularly sexual in nature; the nazir abstains from wine; and therefore, these texts should be read together as suggesting that too much wine leads to sexual sin. To offer a concise and concrete example of this logic:

Another interpretation: Just as the nazir is separated from wine, so too I separate the sotah from the rest of women on account of wickedness. (Numbers Rabbah 10:1)

The first two words of this text—“Another interpretation” (literally, “another word/matter”; Hebrew davar aḥer)—is a common rabbinic phrase in midrashic literature that signals an important technique: the Rabbis report various interpretations, some of which might even contradict one another. As is discussed in chapter 1, the Rabbis are interested in spirited, multifaceted dialogue rather than humdrum, monolithic monologue. Therefore, they regularly offer a variety of viewpoints on a single topic, one after another, rarely with any commentary indicating a preference for any particular opinion. Often, a new interpretation is prefaced simply with the terse introduction: “Another interpretation.”

In this interpretation, Numbers 5 and 6 combine to teach a singular lesson. Just as the nazir takes a vow to separate from wine, so too does God (= “I”) separate the sotah from the rest of women. Just as wine intoxicates the sober mind, so too the (suspected) adulteress leads faithful wives astray. Separation from wickedness is the overarching lesson. And wine, it would seem, is the beverage drunk while sliding down the slippery slope towards sin. For this reason, God placed Numbers 5 and 6 beside one another.

This lesson gets reiterated several times throughout Numbers Rabbah 10:2–4. For example, after connecting wine to adultery, the following conclusion is reached:

Thus we learn that wine leads to whoring. And therefore, The Holy One Blessed be He wrote in the Torah the section about the nazir after the section about the sotah, so that a man should not act like an adulterer and adulteress act, who drink wine and disgrace themselves; but rather, the one who is afraid of sin should separate himself from wine. Therefore, it is said: “When either a man or a woman clearly [utter a vow, the vow of the nazir, to set themself apart for the Lord . . . ]” [Numbers 6:2]. (Numbers Rabbah 10:2)

Too much wine can lead to sexual impropriety (on the gendering of “whoring,” see chapter 4). To caution Jews, God (referred to by the common rabbinic title of “The Holy One Blessed be He”) placed the biblical section (Hebrew parshah) concerning the sotah prior to that of the nazir. This act of divine editorship serves as a moral lesson, instructing those who fear sin to “separate” (Hebrew yazir, from the same root as nazir) themselves from wine. After all, “wine leads to whoring.”

Lest this point was unclear, the very next section of Numbers Rabbah concludes similarly:

Thus we learn that wherever there is wine, there is ‘ervah. And therefore, The Holy One Blessed be He wrote the section about the nazir after the section about the sotah, because wine leads to ‘ervah. And therefore, a man should separate himself from [wine], so that it should not lead him into error. And therefore, it is said: “When either a man or a woman clearly [utter a vow, the vow of the nazir, to set themself apart for the Lord . . . ]” etc. [Numbers 6:2]. (Numbers Rabbah 10:3)

Rabbinic texts can get repetitive: a good point is often worth making twice. While this passage repeats the previous pericope almost word for word, the concern here is that wine leads to ‘ervah: that is, to nakedness (particularly “genital nakedness”; see Neis 2013, 93) and, relatedly, to sexual transgression. The naked body imagined is almost always female; and the sexual transgressions are often biblically forbidden sexual relations, such as incest or prohibited sexual partners (e.g., Leviticus 18:18 prohibits having intercourse with a woman and then “uncovering the nakedness” [Hebrew ‘ervatah] of her sister). Divine editorship therefore instructs that wine leads to nudity and sexual transgression.

If a good point is worth making twice, then it is worth making three times. In the next section of Numbers Rabbah, we encounter the same basic argument, albeit woven into a much richer interpretive fabric:

“And I have not the understanding of a man [Hebrew ’adam]” [Proverbs 30:2]. This [refers] to the first man [Hebrew ’adam], because through the wine that he drank, the world was cursed on his account. For Rabbi Avin said: Eve mixed wine for Adam [Hebrew ’adam] and he drank; as it is said: “And when the woman saw [Hebrew va-tere’] that the tree was good for eating” [Genesis 3:6], and it is written: “Do not look [Hebrew ’al tere’] at wine when it glows red, etc.” [Proverbs 23:31]. “And I have not learned wisdom . . .” [Proverbs 30:3]—from the wisdom of the Torah, because in every place that wine is written in the Torah, it makes a mark. “. . . or have knowledge of the Holy One” [Proverbs 30:3]: If one wants to sanctify himself so that he does not stumble into sin by whoring, he should separate himself from wine, but I disgraced myself by whoring. “. . . or have knowledge of the Holy One” [Proverbs 30:3]: therefore, it is said: [The Holy One Blessed be He wrote] the section about the nazir after [the section about the] sotah. (Numbers Rabbah 10:4)

We begin with a citation from the book of Proverbs, which is read in two ways. First, this passage (and the other citations of Proverbs below) highlights the limits of human knowledge. Second, the word for “man” (Hebrew ’adam, which can also mean more broadly “humanity”) is read as referring to the primordial man, Adam (Hebrew ’adam). At the very beginning of history, wine led to the entire world being cursed. And how do we know this? After all, there is no mention of wine in the biblical account of Garden of Eden! According to Rabbi Avin, however, not only was there wine there, but Eve mixed Adam’s wine! (On mixing wine, see chapter 9.)

What proof does Rabbi Avin have for this assertion? Rabbi Avin links two biblical verses based on a shared word. Once linked, the context or content of one verse is understood to shed light on the other verse. The analogy (Hebrew gezerah shavah; see Lieberman 1994, 58–68; Yadin 2004, 82–83) is one of the basic rabbinic hermeneutic principles (in general, see Strack and Stemberger 1996, 15–30). Remember that the biblical author is presumed to be divine, and therefore chose each word for specific reasons (note the plural here, as much can be learned from each word). So when God says in Genesis 3:6 that, “the woman saw [Hebrew va-tere’] that the tree was good for eating,” the verb for Eve’s gaze was intentional (on the rabbinic gaze, see Neis 2013). One can then skip ahead to Proverbs 23:21 and see that the same verb for sight is used: “Do not look [Hebrew ’al tere’] at wine when it glows red, etc.” (translations of Proverbs throughout this chapter are informed by Fox 2009). In Proverbs 23:21, wine is the subject of the gaze; and therefore, via the rabbinic hermeneutic principle of analogy, Eve in Genesis 3:6 “saw” wine. Now that we know that Eve gazes upon wine, all of the concerns associated with wine can be read into our text—especially those associated with an unquenchable appetite for sex. Therefore, when Eve mixes wine for Adam, it can be read in the sense of Eve using sexuality to seduce Adam, thereby leading him down a dissolute path. Hence, “through the wine that he drank, the world was cursed on his account.”

Read in light of this analogy, the lesson about wine and sexual transgression should have been obvious to the reader. But it clearly was not. Therefore, the Torah had to keep repeating this lesson. And how do we know this? According to Proverbs 30:3: “And I have not learned wisdom.” No matter how many times this lesson was told, it was never learned. The wisdom of the Torah kept reminding its readers by making sure that in every instance in which wine appears in the Torah, it left an indelible mark—like a scarlet A—to demonstrate the evils that befall one who drinks too much wine.

The second half of Proverbs 30:3, “or have knowledge of the Holy One,” further reminds its readers that they have continually failed to grasp this lesson. They should have known to separate themselves from wine in order not to stumble into sin (the Hebrew verb here, yikashel, can mean either stumble or lead to sin, so I have tried to convey both meanings simultaneously). But they did not learn their lesson. Instead, they disgraced themselves by whoring. They needed yet another reminder. To impart this lesson one more time, the divine editor placed Numbers 6 immediately following Numbers 5.

CONTRADICTING TEXTS: INSULTS, WINE, AND SPONTANEOUS HUMAN COMBUSTION

If God composed the Torah in an intentional manner, then when texts contradict one another, there must be a way to resolve that tension. And/or such contradictions must offer a riddle that, once solved, will unlock deeper meanings and additional lessons. Otherwise, the entire house of cards would collapse and nothing would mean anything.

A fascinating example of this general principle in action is encountered in a text that begins with the development of the biblical canon—that is, the normative and authoritative edition of the Hebrew Bible—and ends with two instances of spontaneous human combustion.

And also the Book of Proverbs [the sages] wanted to suppress, for its statements contradict one another. And why did they not suppress it? They said: Did we not study the book of Ecclesiastes and find resolutions [to its contradictory statements]? Here too, let us study.

And which of its statements contradict one another? It is written: “Do not answer a fool according to his folly” [Proverbs 26:4]; but [in the next verse] it is written: “Answer a fool according to his folly” [Proverbs 26:5].

There is no difficulty. This concerns words of Torah, and that concerns general matters.

It is like when a certain man came before Rabbi and said to him: Your wife is my wife, and your children are my children. [Rabbi] said to him: Would you like to drink a cup of wine? He drank and burst [i.e., explodes, or spontaneously combusts].

[Similarly,] a certain man came before Rabbi Hiyya and said to him: Your mother is my wife, and you are my son. [Rabbi Hiyya] said to him: Would you like to drink a cup of wine? He drank and burst. (b. Shabbat 30b)

As the opening indicates, this text appears in the middle of a larger rabbinic passage (Aramaic sugya’) that debates whether to suppress—that is, to declare noncanonical—certain biblical books. The reason for potentially suppressing such works is that they feature contradictory statements. However, the Rabbis were able to resolve these contradictions to their own satisfaction; and hence, both Ecclesiastes and Proverbs become canonical.

The question of whether to canonize these books points to an interesting concern (on this process in general, see Satlow 2014). The Torah is understood to be divinely authored and edited. The rest of the Hebrew Bible (the sections known as the Prophets and the Writings) gains its authority by means of being declared canonical by the Rabbis. Once a book acquires this status, it can be used to interpret other texts and to offer support as a proof text. For example, Genesis is canonical because God declared it so; Proverbs is canonical because the Rabbis declared it so. But notice that earlier in this chapter, Genesis 3:6 and Proverbs 23:31 were analogically connected via the same Hebrew verb for sight. As canonical books, they can be interpreted together. And, in that case, God was presumed to know that Proverbs would be canonized using that precise verb in that precise context, which is why that same verb appears in Genesis and allows for the rabbinic interpretation via analogy.

But the first step to canonization in the case of Proverbs was to show that its contradictions were not really contradictions. Rather, they were riddles to be solved and whose solutions offered new knowledge. Such is the case with Proverbs 26:4–5, which reads in full:

Do not answer a fool according to his folly, lest you become just like him.

Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own eyes.

Should I answer the fool or not? The answer, as we are learning to expect, is: it depends. Our first clue to this answer is the common rabbinic phrase “There is no difficulty” (Aramaic la’ qashya’), which indicates that two texts/opinions do not contradict each other. Sometimes this is because they refer to different situations; in other cases, this is because one text follows the ruling of one authority, and the other follows the ruling of another authority. Either way, it signals that an apparent contradiction can be resolved.

In the present case, the resolution offered is that: “This concerns words of Torah, and that concerns general matters.” This wording is potentially confusing. But rather than resolve that confusion in my translation, I wanted to convey the complexities the text presents. A more lucid translation would have been: “This [latter verse, that is Proverbs 26:5] concerns words of Torah, and that [former verse, that is Proverbs 26:4] concerns general matters.” Therefore, if the fool is pontificating on words of Torah, you should answer him, “lest he be wise in his own eyes.” But if the fool is pontificating on general, not-anywhere-near-as-important-as-Torah matters, then you should not answer him, “lest you become just like him.” The verses do not contradict because they each refer to a different situation. In fact, not only do they not contradict, but they complement one another in order to provide complete guidelines for dealing with a fool.

Next, two examples of dealing with a non-Torah-talking fool are provided (b. Shabbat 30b also goes on to offer examples of interacting with a Torah-talking fool, but I omit discussion of those examples because no wine is involved). In each case, a non-Torah-talking fool walks up to a Rabbi and insults his lineage: in the first case, he claims to have had an affair with Rabbi’s wife, so that his wife committed adultery and his children are not his own; in the second case, he claims to have had an affair with Rabbi Hiyya’s mother and that he is actually Rabbi Hiyya’s father. By claiming to have had an affair with the wife/mother of a Rabbi, the non-Torah-talking fool alleges, not only that he has committed adultery, but that he has fathered the wife/mother’s children. Any child that results from such an encounter is considered a mamzer (Hebrew plural mamzerim). Note that this is not a child born out of wedlock (sometimes pejoratively called a “bastard”), but the product of an adulterous or incestuous sexual encounter. “A full Jew in every other way, a mamzer (male or female) was forbidden from marrying another Jew who was not a mamzer” (Satlow 2006, 183). Therefore, Rabbi’s children and Rabbi Hiyya himself would be forever stigmatized in regard to rabbinic marriage.

Imagine how you might react in this case. A fool waltzes up to you, insults your mother or partner, and then claims that you or your children are mamzerim. I pity the fool who does so. With that mental image in mind, contrast how Rabbi and Rabbi Hiyya react: they offer the fool a glass of wine. Of all the responses you might have expected, I would wager that that was not even in the top 100. But remember Proverbs 26:4: “Do not answer a fool according to his folly, lest you become just like him.” And remember that this is understood to refer to the non-Torah-talking fool, which is the exact type of fool standing before us. Any verbal response would have been to answer a fool according to his folly, so instead they offer him a glass of wine. He accepts the drink and takes a sip. He then explodes. What goes without saying is that these two instances of spontaneous human combustion are divine retribution. In not responding to their respective non-Torah-talking fools, Rabbi and Rabbi Hiyya leave it to God to deal with the fool. Rabbi and Rabbi Hiyya act in accordance with normative rabbinic law (Hebrew halakhah). The non-Torah-talking fools do not. Their combined actions lead to the explosive conclusion in which biblical contradictions are resolved and justice is served.

“IT GOES DOWN SMOOTHLY”: WINE AND TEMPTATION

Although the Hebrew Bible cannot contradict itself, a single verse can still teach multiple lessons. Of course, that does not stop Rabbis from debating which is the “correct” interpretation of a given verse—even while, at the same time, there is an often tacit acknowledgment that there can be multiple, nonexclusionary, “correct” interpretations (and, hence, potentially divergent rulings based upon these multiple interpretations). Scholars often summarize this trend towards legal pluralism by citing the famous rabbinic phrase: “These and these are the words of the living God” (y. Yevamot 1:6, 3b; b. Eruvin 13b; b. Gittin 6b; and, on legal pluralism, see Hidary 2010).

We encounter an interesting example of this phenomenon in a text that opens by quoting a verse already familiar to us:

“[Do not look at wine when it glows red,] when it gives its gleam in the cup, when it goes down smoothly” [Proverbs 23:31].

Rabbi Ami and Rabbi Assi [debated the interpretation of this verse].

One said: Whoever sets his eye in his cup, all ‘arayot appear to him like a plain.

And one said: Whoever sets his eye in his cup, the entire world appears to him like a plain. (b. Yoma 74b–75a)

I translate Proverbs 23:31 initially based on its biblical context, so as to throw into relief the rabbinic interpretative activity that follows. Though the biblical context of the “folly of drunkenness” (Fox 2009, 740) pervades the rabbinic exposition of this verse, the two Rabbis cited derive additional information from its wording.

After quoting Proverbs 23:31, we learn that two Rabbis debated the meaning of this biblical drinking proverb. Accomplished scholars and friends, Rabbi Ami and Rabbi Assi were referred to by honorifics such as “the distinguished priests of the Land of Israel” (b. Gittin 59b) and “the judges of the Land of Israel” (b. Sanhedrin 17b). Yet, while we learn that these two august amiable authorities debated the meaning of this verse (along with several other scriptural passages; see b. Yoma 74b–75a), we are not told explicitly who gave which interpretation. Rather, the text simply notes, “one said” one interpretation, and “one said” the other.

According to the first interpretation, Proverbs 23:31 teaches that, “Whoever sets his eye in his cup, all ‘arayot appear to him like a plain.” How is this meaning derived? In Proverbs 23:31, the phrase, “when it gives its gleam in the cup” could also be translated as: “when he sets his eye in his cup” (see Fox 2009, 741). Reading the text the latter way explains the opening clause of the Rabbi’s interpretation (“Whoever sets his eye in his cup . . .”). Next, the author relies on the common midrashic practice of the pun. First, in the phrase “like a plain,” the words “plain” (Hebrew mishor) and “smoothly” (Hebrew meysharim) are punned; and second, the word for “smoothly” (Hebrew meysharim) commonly refers to “rectitude” or “upright path” in Proverbs (see Fox 2009, 741). The first pun introduces the notion of the drunk man seeing certain things as a smooth plain. The second pun turns this level plain into a slippery slope, sliding from the upright path down into the depths of depravity. This is where ‘arayot comes into focus. ‘Arayot, the plural of ‘ervah, refers to forbidden sexual relations, especially adultery (see Satlow 1995, 140). Therefore, the intoxicated man who focuses on the wine in his cup, rather than on walking on the upright path of moral rectitude, encounters no obstacle as he stumbles down a path descending to sexual transgression.

The second interpretation draws on many of the same readings. In fact, the first interpretation could be included in the second, since the intoxicated man now sees the entire world as a smooth plain, upon which he can stumble unobstructed towards whatever illicit desire he fancies. Rashi, a medieval commentator and reputed winemaker, understands this second interpretation to refer to the fact that “other people’s money appears permitted to him” (Rashi on b. Yoma 75a)—meaning that the drunk man has no moral compunction against theft. There is, however, no reason to narrow this second interpretation just to the realm of theft or sexual transgression; rather, it seems more general than broad: the intoxicated man who focuses on the wine in his cup, rather than on walking on the upright path of moral rectitude, encounters no obstacle in his path as he stumbles down a spiral of sordid transgression.

In the end, these two readings represent a difference of degree more than of kind. Though there are many instances in which a greater interpretive variance is found, the same general principle holds: multiple correct opinions can be offered, and there is not necessarily a need to resolve them into a single, correct opinion. Furthermore, these two readings show another midrashic trend, wherein debate about interpretation leads to a larger commentary on the slippery slope from tippling to temptation to transgression.

CUP OR POCKET? DIRTY MISSPELLINGS AND CLEAN LANGUAGE

We have learned that the Rabbis believe that: (a) the Hebrew Bible is divinely authored and edited, so every word, phrase, and paragraph is intentional, meaningful, and informative; and (b) multiple precise interpretations can be derived from any word, phrase, or paragraph. A fascinating intersection of these two concepts relates to instances where the Rabbis acknowledge a grammatical or spelling error in the written text of the Torah, and then develop a tradition to account for it.

Once the biblical text is understood to be a divine text, a problem arises: how does one deal with instances in which a word is misspelled or grammatical rules are violated? If a text is written by a person of flesh and blood (a common rabbinic term for a human), then the answer is simple: human error. But when the author is God, it is not so simple. In order to deal with such instances, a practice developed known as qere and ketiv, which is well summarized by the two Aramaic words that form its title, qere (“that which is read”) and ketiv (“that which is written”). This practice therefore results in the biblical text written (ketiv) on a Torah scroll remaining in its present form, while a separate tradition records how a given word is read (qere) when a given Torah portion is read aloud.

This approach has two interrelated advantages. First, it preserves the text “as is,” while still correcting apparent errors. Second, the written and read texts are placed side by side, allowing for interpretation based on both the “correct” and “incorrect” text. Taken together, they reinforce the basic presumption of divine authorship and editorship. God intentionally misspells words, makes grammar mistakes, and so on. In doing so, God creates both the qere and ketiv. Therefore, additional interpretations are divinely authorized based on both the “mistake” and the “correction.” Every “mistake” is really an opportunity.

A great example of qere and ketiv involves a variant of the interpretative tradition of Proverbs 23:31, discussed throughout this chapter. We learn:

“[Do not look at wine when it glows red,] when it gives its gleam ba-kis, [when it goes down smoothly]” [Proverbs 23:31].

“Ba-kis” is written (Aramaic ketiv), [which teaches that] through the cup (Hebrew ha-kos) he sets his eye in the “pocket” (Hebrew ba-kis). Torah spoke in a euphemism in order to teach that [the intoxicated man] will engage in ‘ervah. (Numbers Rabbah 10:2; cf. Leviticus Rabbah 12:1)

The ketiv of Proverbs 23:31 is ba-kis, meaning “in the pocket.” However, based on context, clearly the “correct” version should be ba-kos, meaning “in the cup.” These two words differ only in their third letter. In the Hebrew alphabet script, the third letter of the word ba-kis is a yud  , which if drawn just a little longer vertically becomes a vav

, which if drawn just a little longer vertically becomes a vav  , the third letter of the word ba-kos. In English, you could compare this to the difference between a lowercase i and a lowercase j. This is a common scribal error and the “fix” is obvious. For this reason, ba-kos becomes the qere and is reflected in standard printings of the Masoretic text.

, the third letter of the word ba-kos. In English, you could compare this to the difference between a lowercase i and a lowercase j. This is a common scribal error and the “fix” is obvious. For this reason, ba-kos becomes the qere and is reflected in standard printings of the Masoretic text.

Although modern scholars may refer to this as “a common scribal error” (as I just did), for the Rabbis, the qere and ketiv tradition allows for additional, divinely authorized interpretation. God actively chose to misspell this word, so it must offer deeper insight. The intoxicated man “sets his eye in the pocket”—and “pocket” is a euphemism for female genitalia. Note that the phrase used here for “euphemism” literally means “clean language” (Hebrew lashon naqiy). “Torah [i.e., God] spoke” in clean language in order to teach a dirty lesson: once again, we learn that wine leads to ‘ervah, that is, to nakedness (particularly “genital nakedness”; see Neis 2013, 93) and, relatedly, to sexual transgression.

Elsewhere, the Rabbis spell out traditions of employing euphemism for the reading of certain texts that are perceived as obscene (see b. Megillah 25b), suggesting that this is not an isolated case. Furthermore, the notion that this particular qere and ketiv tradition offers a clean euphemism for a dirty word is supported by the discussion in the previous section, above. Remember that, in regard to b. Yoma 74b–75a, two puns led to the level plain becoming catawampus; as a result, the moral high ground tilted downward into a slippery slope toward depravity. And what was at the bottom of this slope? ‘Arayot, the plural of ‘ervah. The connection between ‘arayot and ‘ervah resulted from the following statement: “Whoever sets his eye in his cup, all ‘arayot appear to him like a plain.” Now, read that same line, substituting the qere for the ketiv: “Whoever sets his eye in his ‘pocket,’ all ‘arayot appear to him like a plain.” Therefore, this euphemism might lurk tacitly in the background. Additionally, “in his pocket” might explain Rashi’s reading of the second interpretation that, “other people’s money appears permitted to him” (Rashi on b. Yoma 75a). The pocket is a common place to deposit money, so the ketiv of ba-kis might have primed Rashi to think about money. Sometimes a pocket is a just a pocket.

The tradition of qere and ketiv provides yet another interpretive practice in which the Rabbis square the circle of the biblical text. In doing so, they show how the Hebrew Bible is perfectly imperfect.

“BLESSINGS OF THE BREASTS”: BREASTFEEDING AS DIVINE MIRACLE

Genesis 49:25 speaks of the blessings bestowed by Shaddai, a common name for God. These blessings include “blessings of the breasts” (Hebrew birkat shadai’im). This clever pun in biblical Hebrew between God (Hebrew shaddai) and breasts (Hebrew shadai’im) points to an association that appears elsewhere in rabbinic texts: namely, the fact that the elixir of life for all infants (breast milk) and the source of all life have the same origin, God. And given this association, the miraculous appearance of breast milk is occasionally used by the Rabbis to address potential issues or ambiguities in the biblical text. Therefore, these conversations can serve as case studies of many of the hermeneutical principles discussed throughout this chapter.

The first example relates to the biblical Matriarch Sarah. As the wife of the Patriarch Abraham, Sarah led an adventurous and complicated life, including twice being passed off as Abraham’s sister instead of his spouse (see Genesis 20 and 26). One adventure eluded her, however: namely, motherhood. But then, ten years short of her hundredth birthday, God decided to fulfill a divine promise made to Abraham (see Genesis 17:15–22, in which God promises that Sarah will have a son named Isaac). The Rabbis realize that the idea of a ninety-year-old first-time mother strains credulity, which informs the following midrash:

“And [Sarah] said: Who would have said to Abraham that Sarah would nurse children?!” [Genesis 21:7].

How many “children” did Sarah nurse? Rabbi Levi said: On the day that Abraham weaned Isaac, his son, he made a grand feast [see Genesis 21:8]. All the people of the world gossiped amongst themselves, saying: Have you seen that old man and old woman who brought a foundling from the market and say, “He is our son!” And not only that, but they make a grand party in order to bolster their claim!

What did Abraham our Patriarch do? He went and invited all of the great men of the generation, and Sarah our Matriarch invited their wives. And every wife brought her child with her, but did not bring her wet nurse. And a miracle occurred with regard to Sarah our Matriarch, and her breasts opened up like two fountains and she nursed all of them. (b. Bava Metzi’a 87a; for parallels and discussion, see Haskell 2012, 17–27; Rosenblum 2016, 176–77)

The generative question that this midrash seeks to answer is: why does Sarah talk of nursing “children” (Hebrew banim)—in the plural—when she, in fact, has only borne Isaac, that is a single child?! Grammatically, the answer is actually fairly straightforward: in biblical Hebrew, plurals often simply indicate species (Sarna 1989, 146). The Rabbis, however, believe that the Hebrew Bible was composed by God and that every word—even if seemingly enigmatic, unclear, or misspelled—is intentionally written as such, and therefore encodes potentially profound meaning. A plural noun where a singular noun is expected marks this text for interpretation (see Yadin 2004, 48–79), and to explain it, the Rabbis turn to the verse that immediately follows, which records Abraham organizing a grand feast (Hebrew mishteh gadol, literally, “big drinking party”) to celebrate Isaac’s weaning (Genesis 21:8). They report what they believe to have occurred on that day. As the festivities began, everyone was incredulous that old Abraham and old Sarah could actually be Isaac’s biological parents, and people presumed that Abraham and Sarah had found an abandoned baby in the market and are passing it off as their own child. In order to prove the doubters wrong, Abraham and Sarah invite them all to the weaning party.

At the weaning party, two miracles occur. The first miracle is that although all the mothers rely on wet nurses, they forget to bring them to the mishteh gadol. I consider this a miracle because, had the mothers either breastfed their own children or thought to bring along their wet nurses to do so, the second miracle could not have occurred. The second miracle is that just when Sarah is preparing to wean baby Isaac—that is, to stop producing breast milk—her body suddenly gushes it, enabling her to feed everyone’s offspring. This embodies Sarah’s motherhood. After all, if she can nurse everyone’s babies, could she not conceive, give birth to, and feed her own son? For the Rabbis, then, the plural “children” in Genesis 21:7 contains this entire story. “Child” would not tell the whole story, which is why God wrote “children.”

Another instance in which the Rabbis use the miraculous appearance of breast milk in order to address a potential issue or ambiguity in the biblical text is in regard to a male character in the Hebrew Bible, Mordecai, the cousin of Esther, hero of the book of Esther and the story of Purim (on beverages in the celebration of this holiday, see chapter 6). In Esther 2:7, we learn that Mordecai raised Esther after she was orphaned. This will be an important detail, but it is not this verse that generates the midrash of Mordecai breastfeeding. Rather, it is because, in Esther 2:5, Mordecai is referred to using the past tense of the “to be” verb (Hebrew hayah): “A Jewish man was (Hebrew hayah) in the capital city Shushan, whose name was Mordecai . . .” In its context, this grammatical detail does not seem important. A Jewish man was a resident of Shushan, that is, Susa, the capital of the Persian Empire. So what? We turn to Genesis Rabbah 30:8 to find out:

Rabbis said: Whoever it is said in regard to him “he was” (Hebrew hayah) fed and sustained.

Noah fed and sustained [the inhabitants of the ark] all twelve months, as it is said: “And you, take for yourself from all food [that is eaten and store it away, and it will be food for you and for them]” [Genesis 6:21].

Joseph fed and sustained, [as it is said]: “Joseph sustained [his father, and his brothers, and all his father’s household . . . ]” [Genesis. 47:7]

Moses fed and sustained [the Israelites while they wandered] all forty years in the desert.

Job fed and sustained, [as it is said]: “Or have I eaten my morsel myself alone, [and the orphan ate none of it]” [Job 31:17]—did not the orphan eat from it?!

But indeed did Mordecai feed and sustain? Rabbi Yudan said: One time, he made the rounds of all the wet nurses, but could not find a wet nurse for Esther, so he nursed her himself. Rabbi Berekiah and Rabbi Abbahu in the name of Rabbi Eliezer [said]: Milk came to him and he nursed her.

When Rabbi Abbahu expounded upon this, his audience laughed. He said to them: But is there not a mishnah [see m. Makhshirin 6:7]: “Rabbi Shimon ben Eliezer says: The milk of a male is pure.”

According to rabbinic tradition, if a man “was” (Hebrew hayah) in the Hebrew Bible, then he “fed and sustained” others. To support this claim, several examples are provided (references to the appropriate “was” verse for each character were provided earlier in Genesis Rabbah 30:8). Noah and Joseph have explicit verses. However, notice what is omitted: the important part of the verse, that is, the section that directly indicates that they fed and sustained other people. This is a common feature of rabbinic literature, wherein the citation of a biblical proof text includes only a partial quotation of the verse and often not the relevant part of the verse. This is why I include the rest of the biblical verse in square brackets above. The Rabbis expect their audience to have memorized the Hebrew Bible and therefore presume that hearing the first half of a verse will jog their audiences’ memory, allowing them to fill in the textual gap. This same presumed knowledge allows them to not quote a verse in regard to Moses. After all, anyone who has read Exodus knows that Moses spent significant time in the desert making sure that the Israelites were fed. The verse from Job is a little more complicated, but it is read to prove their general point: Job, like Noah, Joseph, and Moses, fed other people and hence all are referred to using “was” in the Hebrew Bible.

We are left now with Mordecai. We know that he is a “was” man, but how do we know that he “fed and sustained”? A rabbinic legend is told in which Mordecai went in search of a wet nurse for the infant Esther. Unable to locate one, Mordecai nurses her himself. (The grammar of this passage makes a subtle point, as “he nursed her himself” is literally, “he was [Hebrew hayah] her nurse.”) Though Mordecai’s lactation is reported in a matter-of-fact manner, there needs to be further discussion for obvious reasons. After all, it is not every day that a man lactates and nurses an infant. Hence, a rabbinic tradition adds that Mordecai’s milk suddenly came in and he nursed her. However, that comment might serve to clarify that this was not a “one-time” event, as Rabbi Yudan’s comments seem to indicate (“One time, he . . .”); rather, Mordecai continuously “fed and sustained” Esther, and he never hired a wet nurse. Therefore, another clarification is required. Rabbi Abbahu reports that people used to laugh when he taught this tradition, but he would remind them that there is indeed a mishnah that unambiguously states that male breast milk is pure (see Bregman 2017; Rosenblum 2016, 154–55). In fact, in the Mishnah tractate that reports this information, we only learn about female breast milk after we learn about the significantly less common male breast milk (see m. Makhshirin 6:7–8). Since it is plausible, Rabbi Abbahu argues, the story is not laughable.

Taken together, these two texts illustrate how the Rabbis use accounts of miraculous breastfeeding as a means of biblical interpretation (cf. Rosenblum 2016, 175–78). Needless to say, however, rabbinic literature also uses other stories and creative interpretations to address ambiguities in the biblical text—see, for example, the famous story about Abraham smashing the idols in his father’s idol shop in Genesis Rabbah 38:13.

TORAH BRIGHTENS THE FACE

Midrash is the process through which the complex details of God’s commandments are analyzed and comprehended, assuring compliance with halakhah. But that does not mean that it has to be drudgery. In fact, for the Rabbis, this interpretive activity is more hobby than homework. While interpreting Torah is serious business, it is also serious fun.

Lest the reader depart from this chapter thinking that this labor of love is more labor than love, let us examine a text in which this issue comes to the forefront:

Rabbi Yudah bey Rabbi Ilai drank the four cups of Passover night, and bandaged his head until the Festival [of Shavuot].

A certain matron saw him with his face lit up. She said to him: Old man, old man. You are one of three things: either you are a wine drinker; or you are a lender on interest; or you are a pig breeder.

He said to her: May that woman’s breath expire! I am none of these three things! Rather, my learning is within me; for it is written: “The wisdom of a person brightens his face” [Ecclesiastes 8:1]. (y. Pesahim 10:1, 37c)

Our sugya’ opens with an instance of excessive drinking. We learn that Rabbi Yudah bey Rabbi Ilai drank the four cups of wine required for the celebration of Passover (on this practice, see chapter 6). Perhaps unaccustomed to drinking this much wine, he ends up with a headache (which is why he bandaged his head), a symptom likely caused by dehydration. But this is not just any headache (on headaches in rabbinic literature, see Preuss 2004, 304–5); this post-Passover headache persists for fifty days—that is, the length of time between Passover and Shavuot. Quite a hangover!

The detail of Rabbi Yudah bey Rabbi Ilai drinking wine partly cues the tale that follows. The other association that generates this story is the reference to Shavuot (“Weeks” in Hebrew; also known as Pentecost [“Fiftieth Day” in Greek]), a biblical festival later associated with the divine revelation of the Torah at Mount Sinai (e.g., b. Shabbat 86b; b. Pesahim 68b). Therefore, the Festival of Shavuot necessarily gestures towards the importance of Torah and Torah knowledge.

The tale that follows proved quite popular in rabbinic literature, with versions appearing twice more in the Jerusalem Talmud (y. Shabbat 8:1, 11a; y. Sheqalim 3:2, 47c) and once in the Babylonian Talmud (b. Nedarim 49b), as well as in other rabbinic collections. In our present version, a certain matron (Aramaic matronah), that is to say, a high-status non-Jewish woman, encounters Rabbi Yudah bey Rabbi Ilai with his face aglow. She greets him by referring to him as “old man” (Aramaic saba’), a term that can also mean “Tanna.” Not coincidentally, Rabbi Yudah bey Rabbi Ilai is indeed a card-carrying member of the earliest group of rabbis, the Tannaim.

Upon gazing at this old man/Tanna, the matron concludes that his face can only be lit up for one of three reasons, and none of them are good. First, because he is a wine drinker. By this, the matron implies that he is a drunkard, a condition of unrestrained alcohol addiction of which the Rabbis disapprove (see chapter 9). Second, because he lends at interest. Acts of usury are strongly condemned in both biblical (e.g., Exodus 22:25; Leviticus 25:36) and rabbinic literature. For example, elsewhere we learn that:

[Usurers] declare the Torah a fraud and Moses a fool, and they say: “If Moses would have known how profitable we would be, he never would have written [the prohibitions against usury]!” (t. Bava Metzi’a 6:17)

Or, third, because he is a pig breeder. Not on only is eating pork biblically forbidden (Leviticus 11:7; Deuteronomy 14:8), but the Rabbis extend this taboo even to pig-breeding:

[Jews] may not raise pigs anywhere. (m. Bava Qamma 7:7)

Whether outside the Land of Israel or in it, pigs can neither be eaten nor raised by Jews (on the context of this passage, see Berkowitz 2018, 132–38; and on how this affects modern law in the state of Israel, see Barak-Erez 2007). Regardless of which scenario applies—whether drunk on wine or excited by the high profit margins and fast cash made by engaging in biblically and rabbinically forbidden business—the matron believes that his lit-up face is a sign of his bad life choices.

While Rabbi Yudah bey Rabbi Ilai does not disagree that his face positively glows, for him it is a sign of his good life choices. After conjuring an end to the matron’s breathing (an allusion to Ezekiel 37:9, according to Bokser 1994, 591n40), he denies being any “of these three things.” Why, then, is his face aglow? Because “my learning is within me”—meaning that his frequent study of Torah has led to a deep knowledge of rabbinic traditions (on this translation, see Sokoloff 2002, 550). The biblical proof text reinforces this assertion. How do we know that, besides wine drinking, usury, and pig-breeding, Torah learning can light up one’s face? Because it is written in Ecclesiastes 8:1: “The wisdom of a person brightens his face.” For Rabbi Yudah bey Rabbi Ilai, it is Torah—and not wine—that brightens his face.

In the continuation of this sugya’, which I do not quote in full because of its lack of reference to beverages, Rabbi Yohanan’s students remark on the bright face of Rabbi Abbahu. They believe his visible joy is because he “has found a treasure.” Rabbi Yohanan replies, “Perhaps he has heard a new biblical interpretation?” and then inquires of Rabbi Abbahu, “What new biblical interpretation have you heard?” Rabbi Abbahu answers that he has heard “An old supplementary teaching” (Aramaic tosefta’ ‘atiqta’). It is not a “new” lesson that he has learned, but an “old” one, which is indeed a “treasure.” For this reason Rabbi Abbahu’s face lights up and the sugya’ concludes: “And [Rabbi Yohanan] applied the scriptural verse to [Rabbi Abbahu]: ‘The wisdom of a person brightens his face’ [Ecclesiastes 8:1].”

Learning Torah is a joy. In the process of this joyous practice, Torah knowledge becomes embodied in those who learn it. The light of Torah then shines through them, illuminating their faces.

CONCLUSION

Viewed through the drinking glass, the main presumptions and principles that govern rabbinic biblical interpretation become visible. If—as the Rabbis presume—God is the author and editor of the Torah, then seeming contradictions, misspellings, ambiguities, and even the organizational logic of the texts themselves are really intentional opportunities to learn more. Torah is perfectly imperfect.

There is much more to midrash than can be discussed in this chapter, but these beverage-related texts have certainly imparted enough wisdom to brighten our faces, though likely not enough Torah water to quench our thirst.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Bakhos, Carol, ed. 2006. Current Trends in the Study of Midrash. New York: Brill.

———. 2009. “Recent Trends in the Study of Midrash and Rabbinic Narrative.” Currents in Biblical Research 7/2: 272–93.

Bar-Asher Siegal, Michal. 2013. Early Christian Monastic Literature and the Babylonian Talmud. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Barak-Erez, Daphne. 2007. Outlawed Pigs: Law, Religion, and Culture in Israel. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Belser, Julia Watts. 2015. Power, Ethics, and Ecology in Jewish Late Antiquity: Rabbinic Responses to Drought and Disaster. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Berkowitz, Beth A. 2018. Animals and Animality in the Babylonian Talmud. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bokser, Baruch M., trans. 1994. Yerushalmi Pesahim: The Talmud of the Land of Israel: A Preliminary Translation and Explanation. Completed and edited by Lawrence H. Schiffman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boyarin, Daniel. 1994 [1990]. Intertextuality and the Reading of Midrash. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bregman, Marc. 2017. “Mordecai Breastfed Esther: Male Lactation in Midrash, Medicine, and Myth.” In The Faces of Torah: Studies in the Texts and Contexts of Ancient Judaism in Honor of Steven Fraade, ed. Michal Bar-Asher Siegal, Tzvi Novick, and Christine Hayes, 257–74. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Brumberg-Kraus, Jonathan. 2018. Gastronomic Judaism as Culinary Midrash. New York: Lexington Books.

Fox, Michael V. 2009. Proverbs 10–31: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Fraade, Steven D. 1991. From Tradition to Commentary: Torah and Its Interpretation in the Midrash Sifre to Deuteronomy. Albany: State University of New York Press.

———. 2012. “Concepts of Scripture in Rabbinic Judaism: Oral Torah and Written Torah.” In Jewish Concepts of Scripture: A Comparative Introduction, ed. Benjamin D. Sommer, 31–46. New York: New York University Press.

Haskell, Ellen Davina. 2012. Suckling at My Mother’s Breasts: The Image of a Nursing God in Jewish Mysticism. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Hidary, Richard. 2010. Dispute for the Sake of Heaven: Legal Pluralism in the Talmud. Providence, RI: Brown Judaic Studies.

Kanarek, Jane L. 2014. Biblical Narrative and the Formation of Rabbinic Law. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kugel, James L. 1990. In Potiphar’s House: The Interpretive Life of Biblical Texts. New York: Harper Collins.

Lieberman, Saul. 1994 [1950]. Hellenism in Jewish Palestine. 2nd ed. Reprint. New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America.

Neis, Rachel. 2013. The Sense of Sight in Rabbinic Culture: Jewish Ways of Seeing in Late Antiquity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Preuss, Julius. 2004 [1978]. Biblical and Talmudic Medicine. Translated and edited by Fred Rosner. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Rosenblum, Jordan D. 2010. Food and Identity in Early Rabbinic Judaism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2016. “ ‘Blessings of the Breasts’: Breastfeeding in Rabbinic Literature.” Hebrew Union College Annual 87: 147–79.

Sarna, Nahum M. 1989. The JPS Torah Commentary: Genesis. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

Satlow, Michael L. 1995. Tasting the Dish: Rabbinic Rhetorics of Sexuality. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature.

———. 2006. Creating Judaism: History, Tradition, Practice. New York: Columbia University Press.

———. 2014. How the Bible Became Holy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Smith, Andrew F. 2013. Drinking History: Fifteen Turning Points in the Making of American Beverages. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sokoloff, Michael. 2002 [1990]. A Dictionary of Jewish Palestinian Aramaic of the Byzantine Period. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sommer, Benjamin D. 2012. “Concepts of Scriptural Language in Midrash.” In Jewish Concepts of Scripture: A Comparative Introduction, 64–79. New York: New York University Press.

Strack, H. L., and Günter Stemberger. 1996. Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash. Translated and edited by Markus Bockmuehl. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Yadin, Azzan. 2004. Scripture as Logos: Rabbi Ishmael and the Origins of Midrash. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.