March

It was cold for two weeks. The frogs stopped their shenanigans and bedded down in the depths of the pond while we humans that could afford to turned up our central heating. Before it turned cold it was warm – really warm. I took Tos up to the Downs on Valentine’s Day and wore a T-shirt. I found my first slow worm of the year and my first buffish mining bee, Andrena nigroaenea, feeding from snowdrops in the front garden. I saw bumblebee queens out of hibernation, the odd bursting of buds. And then it was winter again: frost on the shed roof, ice on the pond, hard, dry, ground. We can put a jumper on; what do the bees do?

While the frogs slept through the cold spell, my focus switched to hedgehogs. Suddenly the food in the feeding station was being taken, and so I topped it up properly and found it empty again the next morning, along with my first hedgehog poo of the year. It makes sense that it came to my garden as temperatures dipped, as it knew there would be kitten biscuits to make up for the sudden departure of earthworms. I put my camera out and watched footage of a chunky male hog licking his lips as he left the feeding station, and another of him coming into the garden via the back gate. It’s always reassuring to see when species have survived hibernation, especially when the weather is so changeable – they can’t be hibernating properly.

Temperatures eased a little for a while and the frogs started stirring again. Nothing like the vigorous parties of mid-February, but the odd blob of spawn would appear here and there, as subdued efforts to party were rekindled. But then there were reports of more ice and snow to come, of an ‘Arctic blast’. It wasn’t known where exactly, or for how long, but it would come. I pushed all the frogspawn beneath the surface of the water and topped up the pond to create an insulating later of water above the spawn, to give it the best possible chance of surviving. I watered plants that were already suffering from drought and which I didn’t then want to succumb to the cold. I waited. On the morning it got cold I walked to the gym, and arrived with a bright-red face and no feeling in my hands. But then it got mild again, and then cold again, and mild again, and then freezing. But there was no snow. I watched the telly, bemused at all the reports of snow, and wondered if it would come here. I texted family, ‘Have you got snow?’ And they said, ‘Yes!’ and sent pics of it falling and landing in great pillowy heaps. Then one weather report made everything clear: it showed a map of the UK that was all icy blue except for a thin ribbon of yellow on the south coast. Ahh, that explains it. The Arctic blast had just missed us.

Instead of snow we have rain. Two days of glorious, life-affirming rain. I take Tos out in it, wash my face in it, open the window so I can listen to it. I rejoice at full water butts and then half-empty them again so I can water the hedge by the wall and the bit of lawn beneath the shed roof. In the front I water the pots and the rain shadow of next door’s hedge, where very little grows. I stand at the kitchen window and watch raindrops land in great splashes in the pond, filling it to its absolute limit. Through binoculars I watch frogs. Lots and lots of frogs.

I count 30 frogs in the pond, just two weeks after around 50 of them had made their enormous spawn cushions. Thirty frogs leaping about, chasing each other, laying spawn. ‘They’re back,’ I say to Emma, and immediately ban Tosca from leaping around the garden. ‘They’re back and they’re spawning and my god, what are all these frogs going to look like in summer?’

I resume my little vigil at the bench, in the dark. It’s raining and the water is running down my back. I move to the edge of the pond to make myself slightly more comfortable, and shine my torch on amorous couples, of males jumping on females, of males biting the back legs of others who were already coupled up. On a newt. A newt? A newt!

She’s sitting at the edge, like she has always been there. A gravid female (full of eggs), she’s ignoring the frogspawn and eating a worm. A newt! In four years and two months the garden has its first newt. For a moment everything is perfect.

It’s often the way. In the wild, new ponds are formed and the frogs typically find them before other amphibians, taking advantage of fewer predators than in established ponds. They spawn and spawn and spawn, and it looks like they’re never going to stop, that there’s going to be too much, that there’s far too much for that one pond to support. But, gradually, it all gets eaten, by beetle and bug larvae, by dragonfly and damselfly nymphs, by birds and, eventually, by newts. When the frogs started spawning in such unfettered abundance, I knew it couldn’t last. ‘There are no newts,’ I would say to anyone who would listen. ‘It’s a new pond and there are no newts and they’re just taking full advantage.’

It makes sense that the newts would wait for a good population of frogs to establish before laying eggs of their own. And so, after three years of absolutely enormous amounts of frogspawn and tadpoles, the frogs have met their match.

I had an inkling newts had arrived, in December. There were bubbles coming to the surface of the pond, along with flashes of movement that were too quick for me to get my eye in. So they could have been here for months. And for the first newt I meet to be a gravid female suggests there are males here, too. You wouldn’t turn up to a pond full of eggs with no one around to fertilise them.

Tos wakes up for a wee at 4.30 a.m., and we let her out as she refused to go at 10.00 last night. ‘I’ll take her,’ I say, which is only so I can gawp at frogs and newts while she finds the perfect place to pee. I open the back door and I needn’t step out, there’s enough to keep me entertained on the doorstep: two toads. Oh rain, how I love you and all that comes with you. Two toads on the patio, making their way to the pond, 30 frogs in the water and a newt full of eggs. It’s going to be a busy few days.

The man who flew a drone at lesser black-backed gull nests last year is at it again. The peace is destroyed up to four times a day by scared, angry gulls launching into the air and crying out their piercing alarm calls. It sounds like they’re saying, ‘NO! NO! GET OFF! NO!’ Over and over and over. They’ve only just returned from their overwintering sites in West Africa. They’ve been here five minutes and already they’re being harassed. The herring gulls haven’t started collecting sticks from my garden yet but they have established their territories and both species have returned to the same nesting sites as last year. Which means they’re in trouble. The same people in the Facebook group are up in arms. ‘I’ll dig out the number of the PCSO I spoke to last year,’ says one. ‘I’ve got more footage!’ says another.

I decide this year not to take a back seat, not to read without comment. I post on the page: ‘Hello, would anyone like to meet up to discuss if we can work together to help the gulls?’ Three people say yes and two can make it for a drink in the local pub. I meet Lorna and Lin. Lin tells me to ‘look out for a tired old goth,’ while Lorna I recognise as she often stops to chat when I’m in the front garden. They bring photocopies of emails and I take my notebook. We assign tasks, swap information, give the man a nickname: Drone Bastard. I confess that I don’t actually live on their road and feel like an interloper. They don’t seem to mind. ‘Can we call ourselves Gulls Allowed?’ I ask, and they laugh. I will try to fight this man with humour and love; I will try not to be upset by him. I will try to get the police to turn up. They have one job – for the love of all the things, please, just turn up.

I haven’t seen my little gravid newt since that first night, but I have been putting the camera out and the hedgehogs have set it off while the frogs have been croaking so I’ve been able to gawp at chubby hedgehogs while listening to frogs. It’s a nice life if you can get it. In one of the clips, above the snuffling of the hedgehog and the low croaks of the frogs, I could just make out the squeaking of toads. Or one toad? Naturally, I aim to find out.

I’ve seen three toads in the garden so far this year. They’re small, warty things, standing still for ages. Males only. They seem less eager to get into the pond, less frantic and desperate than the horny frogs. Watching leaping frogs through binoculars from the bathroom window was extremely amusing. Toads, by comparison, seem almost prudish. Perhaps they’re young, perhaps they’re shy. I really hope the females turn up this year and show them what’s what.

Twiggy’s mum, Rachel, said she would keep an eye out for toads for me. She seemed open to the idea of me inspecting the twitten at night with a torch. Bits of rain are forecast now for the next few days, so more shy, prudish toads will be on the move. I will be on my bench in the dark, waiting for them.

Mid-March and it finally feels like spring. The sun is shining, there’s a gentle warmth out of the wind. There are hairy-footed flower bees fighting over lungwort, the first Eristalis tenax drone fly basking in the sunshine. A bald wet alien climbs up a daffodil stem and later reveals itself to be a newly hatched narcissus bulb fly. There’s a chiffchaff on the shed roof, the first tadpoles in the pond.

I sit in the front garden and marvel at my new meadow. It’s nearly looking good: daffodils provide colour and height, above the snowdrops my sister Ellie gave me for my birthday, and the first of the bright pink lungwort flowers. There are large clumps of grass I can’t yet identify, which looked out of place a few weeks ago but now seem less so as everything has grown around them. There are clumps of other things emerging, too – somewhere some of the 50 snake’s head fritillary bulbs I planted in autumn, along with what looks like alliums I must have missed when digging up the herbaceous plants. (They might look out of place in a native-ish wildflower meadow but I can always cut them for the vase.) There’s purple toadflax, which seeds itself in and provides leaves for the caterpillars of the toadflax brocade moth, along with nectar for dozens of bees, butterflies and moths. There are primroses, which haven’t quite done anything yet, and primulas, which must be somewhere. There are the first lush clumps of mountain cornflower, the first new leaves of evening primrose. There are strappy leaves of greater knapweed, splayed-out rosettes of shepherd’s purse. I’m pleased to find the wall bellflower, Campanula portenschlagiana, is finally growing in the wall – after four years of trying I had almost given up hope. The sweet rocket is putting on growth and should flower for the first time this year. Above it is a large gap in my side of next door’s hedge, where I’ve planted winter honeysuckle and ivy, in the hope that something might thrive there. Eventually, I would like them to outgrow the forsythia and Japanese spindle. Just a little bit. Just enough so they still provide support for the ivy to grow up.

When I moved the meadow from the back to the front, I planted things into the rain shadow of the hedge to see if anything would survive. I’ve been emptying the previous night’s hot-water bottle on to it daily for the last few weeks and my efforts are paying off – the ox-eye daisies are putting on growth, along with the red clover and some sowthistle that had self-seeded. That area will always be drier than the rest of the garden and I’m hoping I can work out which species will not fare so badly there. There’s plenty of room for other things to seed in if they want to, otherwise it can just become an additional habitat for mining bees, many of whom nest in dry, sparse soil.

We often forget, as gardeners, that every single thing in the garden has the potential to be a habitat, like the leaves that were blown into the pond, which provided a microhabitat for tiny new tadpoles that sit in them and eat algae from them. The rain shadow in the front garden, where plant growth is limited because the hedge stops rain falling beneath it, could therefore be celebrated as a habitat in its own right. Rather than trying to encourage things to grow, rather than emptying endless spent hot-water bottles on to it, perhaps I should leave it bare and see which invertebrates use the expanse of soil, which plants seed in that can cope with the dryness. There’s another mini habitat here, too, a little pile of stones and earth beneath the gas meter that mining bees might nest in or a frog might take shelter beneath. Along the far side, beneath the hedge, is a tiny wall where the render has started to come off, revealing a mass of bricks with no pointing. Perhaps hairy-footed flower bees nest here, and there will be other insects and spiders taking advantage of the sunny crannies, too. Literally everything is a habitat.

The pots along the front path are coming along well. The tiny strawberry tree that will never be a tree, the mint and oregano that will soon be ready to harvest. The agapanthus, the lavender. Everything is so full of promise.

In the back I steal an hour to do some gardening. There’s not much to do so I sweep the patio and pull up the remains of last year’s sweet peas, and put the table and chairs back out. I cut back fern leaves, beneath which new fists of growth are punching through the soil. I pull out crocosmia seedlings and sweep bay leaves off emerging primrose flowers. I transplant clumps of grass that have seeded into the border to some bald patches of lawn, and use a fork to scratch the remaining bald patches to sow seed into. Rain is due tomorrow so I’m hoping the combination of moist soil, mild temperatures and a dog that hates being wet might just encourage germination.

The pond has turned bright green with algae but I can’t do anything about it now there are tiny tadpoles. Besides, what do tadpoles eat? I hope nature will sort itself out and not let me down. I tickle the soil with my cultivator and wonder, still, who everyone is that is popping up to say hello. Little red buds, little green leaves. I scrape hedgehog poo off the feeding station and clean the bowl before refilling it with biscuits. Then the gulls start crying and I look up to see the drone flying low above the rooftops, scaring them off their nests.

I grab my phone and stand on the bench so I can get a better view, take a better video. The drone moves purposefully – starting at one end of the row of houses and working its way to the other end, stopping periodically at what I can only assume are gull nests. I watch it dip down and then rise again, move on to the next nest, dip down and then rise again. I can see that, despite wanting to stop gulls nesting only on his roof, Drone Bastard is also disturbing the gulls on the roofs of nearby houses. Gulls that Lin and Lorna have told me nest there every year and have names. Gulls that are part of the fabric of this neighbourhood. Gulls that belong here. I make a few videos and then text the Gulls Allowed group, who tell me he’s had the drone out five times today. Is there no law that will stop him?

Another visit to Dad and Ceals and I’m thinking of curlews. I have Tosca with me this time. She gets me up at 5.30 a.m. and we head out into the dawn, crossing the road to the path that will lead us on to the marshes.

It takes ages to get off Dad’s estate. Tosca is beside herself with excitement – she hasn’t been here before and every bit of grass, every lamp post, every boring-looking piece of pavement is a new world of things to sniff.

‘But curlews!’ I say. ‘Come on, you’ll have all the sniffies of the most wondrous things you never dreamed existed, in just a few minutes!’

‘But this bit of manky puddle,’ she says. ‘This old leaf.’

I let her off the lead so she can sniff to her heart’s desire while I make my way to the path – she can catch me up when she’s ready. She’s soon at my heels again. ‘Sorted?’ She huffs. We cross the empty road to the path. Tosca stops to sniff the broom, the bracken, the soil, and then catches me up in great, leaping gambols. She is a sausage.

The dawn gives way to a beautiful spring morning. There’s a big yellow ball rising into a cloudless blue sky and only a whisper of wind. The dawn chorus has shifted a gear and I can hear great tits and chaffinches, blackbirds and wrens. It’s been a long time coming, this spring. There’s no hint of the marshes yet; the path is surrounded on either side by heathland. There are posters warning of adders but it’s too early in the day to worry about them biting an excited dog’s nose, and besides, despite her excitement, she knows to stick to the path. I think of all the things she might be smelling now. What do weasels and stoats smell like? What do adders smell like? Can she smell hares or hedgehogs or badgers? She can’t contain herself. She’s running around in circles, from one smell to the next, pausing only to catch up with me. Her face tells me everything I need to know: that this path is the most exciting path EVER, that these bushes and bracken are FULL OF ALL THE SMELLS. But then it ends. Just as suddenly as crossing the road from Dad’s estate on to the heathy path, we leave the bracken and broom and my boots sink into mud – the outskirts of the marshes. We briefly join a clay, puddly bridle path that leads to a metal kissing gate that opens on to the estuary, and as I click open the latch I hear a bubbling overhead. A curlew!

It’s the only curlew I hear this morning, a brief call as it comes to land or takes off. We’re entering their breeding season and I wonder if they breed here as well as overwinter, or if they move on to somewhere else.

Instead I tune in to oystercatchers and skylarks, to ducks and geese that I can’t identify – perhaps the wigeon from November. There are no cows on the marshes today. We walk along the old railway line, which is only slightly drier than the boggy grass around us. On one side is short grass and puddles, which is usually where the cattle graze, and the other side has long grass – perhaps a crop of rye – and reedbeds in the distance. We stick to the short grass and the path, so as not to disturb any wild things, me throwing treats for Tos, who runs up and down the banks in excited scurries, splashing in puddles and stopping for yet more sniffies. The sky echoes with oystercatchers.

The wind picks up and the oystercatchers land and quieten, and I tune in to a different sound, an eerie sound I’ve heard only once before in a sound recording of marshland, which I thought was feedback from the recordist’s equipment. It sounds like a synthesiser, like aliens have landed. It’s brief so I can’t follow it to locate its makers. But I’m enchanted again, as I was in autumn with the curlews. What other secrets do these marshes hold?

We head onwards, the dog and me, over the estuary bridge on to Walberswick Nature Reserve. The marsh recedes to heathland again, and with it return the posters warning of adders. The sun is higher in the sky now, and there are grassy patches where there might be nesting – or resting – birds. I put Tosca on the lead and we stick to the main concrete path that takes us to Walberswick village, which, we both decide, is only slightly less interesting than bowling among the bracken. She makes me stop for every last sniff; I make her stop for birdsong.

Every tree has a chiffchaff in it, every third tree has a yellowhammer, and as we walk past one particularly chunky broom, I jump to my first booming Cetti’s warbler since last summer. Oh, my heart. It’s still only 8.00 a.m. and my whole body rings with the sound of a thousand wild things. Why must mornings like this be so rare?

We walk into the village, say hello to the swings I used to play on as a child, marvel at beautiful houses I couldn’t begin to dream of living in. We loop around the church and head back on ourselves, back to the bridge and the ridge, the puddles and the oystercatchers. I marvel at the footprint patterns of wading birds in the sand. I listen out for the eerie sounds again but the wind fails to bring them to me.

Back at Dad’s I message Stephen, who made the sound recording where I mistook living beings for electrical feedback noise. I find his clip with the noises and identify the eerie sounds at 1 minute 42 seconds. I confess my ignorance and ask him, ‘Do actual birds make this noise?’ I feel stupid but there’s no point in pretending to know things you don’t know, and I’m a city girl after all. Besides, he’s used to my questions. It was Stephen I chatted to about curlews back in November, Stephen who suggested what time to head out to hear them, Stephen who explained how they live. If anyone is to join me for my marshy awakening it must be him. ‘I’m ever so sorry to bother you again,’ I say.

He tells me they are lapwings. Lapwings, the birds with the black-green and white markings and the crest, birds I have seen and known (or thought I have known) for years. I’ve spotted them flying overhead, watched them land to feed in fields. During a particularly cold spell recently, there was one that ended up in Brighton city centre, which was rescued by someone from the bird rescue group I follow on Facebook (it had a terrible neck injury and died, sadly). I know lapwings. I thought I knew lapwings.

I remember being told that they are called peewits because of the strange sounds they make, and of not really paying attention because peewit isn’t such a remarkable sound when said phonetically by a human. Stephen sends me another recording, this time only of lapwings, and I am transported into another world, a world of the most wondrous sounds, of wildness, of loss.

The lapwing has declined by 55 per cent since 1967, due largely to the intensification of agriculture. It’s no real surprise that I’ve never heard one – I grew up in the suburbs just outside Birmingham and have seen them only a handful of times. ‘You will have seen them out of breeding season,’ says Stephen. ‘That sound is only what they make on nesting territories in the spring.’

Like the curlew, the lapwing is a ground-nesting bird, and subject to the ravages of farmland machinery and the absence of ‘fallow’ land that used to be commonplace. I read that they nest from mid-March to June, and realise I have caught them at the very beginning of this year’s breeding season. I read that the collective noun for lapwings is a ‘deceit’, which seems mean, although they did convince me they were electrical feedback noises rather than actual birds. I read that they nest on short grassland and grazed farmland, and that wet pasture is an important source of food for them. No wonder they like Walberswick.

The next morning I wake again to my furry alarm. ‘Shall we go and see the lapwings?’ I ask. ‘Woof,’ she replies.

The wind is stronger today and I tune in to fewer songbirds as we trudge along the path to the marshes. We walk together on the lead, just in case there’s a stray lapwing on the short grass, along the old railway line and over the bridge to Walberswick. There are fewer chiffchaffs and yellowhammers, there’s no Cetti’s warbler. We do meet a redshank, though, as we walk back along the estuary. It has been spooked by something that is neither me nor the dog, and it cries out, loudly, taking refuge on a boat. A predator, perhaps. A stoat?

There are no distant alien sounds today, or none that is carried on the wind. But, as we head back, I loop round to another bit of path beyond a mound, from which yesterday’s noises came. I have no binoculars with me but I can just make out a deceit of black-and-white birds near a stretch of water in the distance. ‘Lapwings!’ I tell Tosca. She is busy tracking the scent of something.

We plan to return, with Dad’s binoculars, the following morning but we don’t make it. Tosca treats me to a lie-in until 7.00 a.m. and we stay in bed for cuddles while the wind and rain howl around us. I am more prepared for wet weather than I was the last time I visited, but it’s still not enough to persuade me to head out. And Tosca hates being wet. So we stay in bed and play ‘Cheeky Monkey’, which involves me grabbing her paws and asking ‘Are you a cheeky monkey?’ while she lies on her back and growls. Sometimes that’s all you need, along with nice a cup of tea. But the curlews and the lapwings, and the other new marsh friends I have yet to meet! I’ll be back for them, perhaps, without the dog.

From Dad’s I head to Emma’s mum Anne’s, where Emma has been for the last couple of days. We spend the weekend celebrating Anne’s 70th birthday and then return home after nearly a week away, tired but happy to have seen everyone. I open the back door and squat down in front of the pond.

‘What are you doing?’ says Emma.

‘I’m looking for toadspawn. I can’t believe there isn’t any,’ I reply, wondering where they are breeding because there was a couple in amplexus last week and it would be odd, although not that unusual, that they would get together in my pond and then swan off somewhere else to actually lay their eggs.

‘It’s here, you plonker,’ she says, ‘it’s bloody everywhere!’ and suddenly I see it, tramlines upon tramlines of the stuff, ribboned through the curled pondweed and wrapped around submerged stems of marsh marigold and even a thin, underwater branch of one of the bits of wood I placed at the edge, which doubles up as a dragonfly perch. Just as it should be. ‘Toadspawn!’ I gasp. ‘So it is!’

At night I let Tos out for a wee and crouch down by the toadspawn. There are several males, but at least one couple in amplexus, along with a mating ball that I think involves a frog. I laugh, and then see my little newt (or one of my little newts?) pawing through the pondweed into my torchlight. ‘Hello toads, hello frog, hello newt,’ I say. After a few days in the countryside among Cetti’s warblers and lapwings, I was worried I would have fallen out of love with my little city garden. But how can I? I sit on the bench as toads squeak among their eggs, as a hedgehog crunches kitten biscuits, as this little patch of Earth wakes into spring. ‘Hello, hello, hello!’

In a stable climate, temperature and rainfall records are rarely broken; the highs and lows fall within established, constant parameters. But in a destabilising climate records are broken all the time, and so it is that after the driest February since 1934, we are closing in on the wettest March in 40 years. I’m grateful for the full water butts and pond but am itching to get outside and do some gardening. I watch the outside from inside: my rambling rose ‘Frances E. Lester’ has come into leaf, as have my spindle and guelder rose. Daffodils are still going strong although they’re being battered by wind and rain. There are primroses, lungwort and cowslips in flower. Every night I fill the hedgehog dish with kitten biscuits and every morning I watch videos of hedgehogs coming and going from the garden, entering the feeding station or pushing each other out of the way. What I’d give for a calm, sunny spring day.

The winter robin has gone and the spring and summer robin has taken his place. I don’t know this, really, I’m just guessing. They could all be the same robin for all I know. This new or not-so-new robin has brought a mate. I watch them from the kitchen; they hide in next door’s wisteria and take it in turns to visit the hanging bird feeders, which 2022’s summer robin didn’t do. Perhaps this is the winter robin who has defeated his rival and decided to stay? There’s no way of really knowing.

There are two robins and I like them. One morning, Tos gets me up at 5.30 a.m. and I stand in the kitchen, looking out. The robins are inspecting the robin box and its vicinity. I watch them fly to and from it, fly to the ivy growing around and beneath it, hop among the guelder rose branches that grow next to it. The female sits in the box and splays her wings as if to say, ‘Let’s choose this one!’ I text Emma and tell her the robins have been and she tells me she has seen them ‘opposite the bench, yes?’ She has seen the robins together in the garden and not thought to tell me, and I would be annoyed if I wasn’t so delighted. We might have baby robins!

Later, I bump into Helen, who lives in the house behind mine and has had robins nesting – unsuccessfully – in her garden several times.

‘Have you seen much of them this year?’

‘They’re around, but I don’t think they’re nesting yet.’

I tell her about the splaying behaviour and the box and the ivy. ‘That’s exciting,’ she says. She tells me she had a conversation with another neighbour about hedgehogs recently, and that my efforts to rewild South Portslade are working. ‘Excellent!’ I say, deliberately not spoiling the moment by asking if the hog was seen out in the day. We both agree to keep an eye out on the robins, and keep each other posted. I LOVE having these chats with my neighbours.

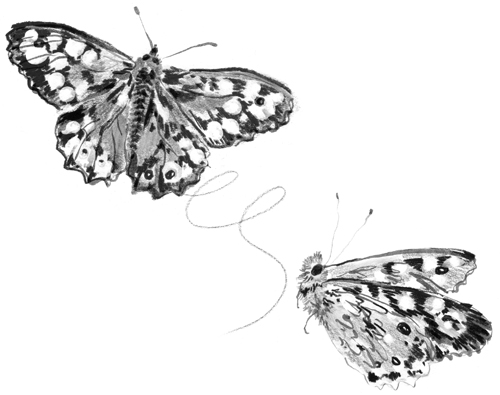

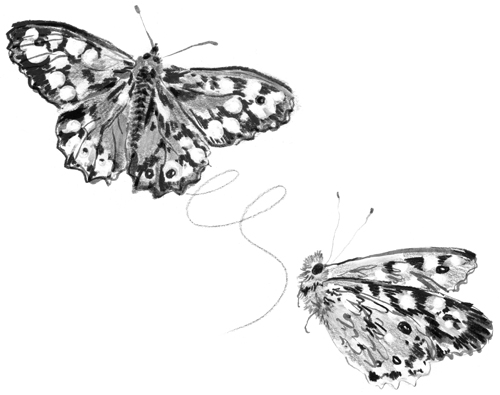

Speckled wood butterfly, Pararge aegeria

The speckled wood butterfly (Pararge aegeria) is a butterfly of woodland glades, of dappled shade and hedgerows but also gardens, including very urban ones. It was one of the first butterflies to arrive in my garden, although I’m not sure if it’s breeding here. It’s brown with a series of spots, which are cream-white if you live in the north of Britain but cream-orange if you live in the south. It rarely visits flowers as it prefers to drink aphid honeydew from high up in the tree tops but it’s a strong flier and males are territorial – look for spiralling fights as they chase rivals off their patch.

If a female happens upon a male’s patch she will fall to the ground and, after a brief courtship, will mate with him. She lays her eggs in long grass – specifically cock’s-foot (Dactylis glomerata), common couch (Elytrigia repens), false brome (Brachypodium sylvaticum) and Yorkshire-fog (Holcus lanatus). These will naturally seed into your ‘lawn’ if you let them. As in my garden, it’s usually the first butterfly to arrive to new meadows but others may follow suit, including meadow brown (Maniola jurtina), gatekeeper (Pyronia tithonus) and ringlet (Aphantopus hyperantus), which all breed in long grass.

The speckled wood butterfly is unique among British butterflies as it can overwinter as both a caterpillar and a chrysalis (pupa). This means you’ll find adults at different times in spring, with some emerging as early as March and others not on the wing until June. They have two or three generations per year, depending on the weather, and adults of later generations are generally darker than those from earlier in the year.

To garden for them is easy: they need long grass, areas of shade, and somewhere for their caterpillars or pupae to shelter in winter. The fresh green chrysalises are usually attached to the underside of a grass stem or piece of dead leaf. I often worry that cutting meadows to the ground in autumn is bad for speckled woods, as the caterpillars may still be using the grasses or the pupae may be attached to a stem that is cut – I’ve found them only when cutting long grass. One of the reasons I’ve moved my meadow into the front garden is that there will be less incentive to cut it right back at the end of summer, that I can leave it long and scraggly for winter. I’ll cut it back at some point, but I’ll leave a few inches above ground as a ‘buffer’ and let the clippings rest on the surface for a few days so anything eating the cut blades can simply drop back into the thatch. You could do this too: let grass grow long but let some of it stay long (or at least tufty) all year round. It won’t be long before a cream-spotted brown butterfly lands in a sunny spot and claims it as his territory. Fingers crossed a female will fly past and drop down to join him.