On the morning of Tuesday 21 March, Peulevé said goodbye to Poirier and took his usual route down the back stairs, discreetly leaving the Champanatier by a side door and walking the short distance to Bloc-Gazo's offices. Whilst in town he was alerted to a problem concerning the supply drop planned for the next day: the dropping area, situated near a disused aerodrome, had suddenly been occupied by a German anti-aircraft battery posted there on training duties. It was imperative that London was told to cancel the operation as soon as possible and Roland Malraux, only having joined the organization a few days before, accompanied Delsanti and Peulevé to visit Bertheau at his hideout on the Route du Tulle. Travelling in Peulevé's Chevrolet across Brive in the brisk, bright afternoon, they parked on the road outside Lamory's house and made their way up the stairs to the larger of the two rooms on the first floor, taking turns to keep a lookout from the front window while the others began preparing Peulevé's telegram for London and deciphering several other messages received by Bertheau over the past few days.

Around half-past three Arnouil left his house on nearby rue Edouard Branly, walking the few hundred yards to join the group as arranged. Turning right onto the Route du Tulle, he was about to cross the road when two black Citroëns sped past him and suddenly halted 100 yards further up, directly outside Lamory's address. Arnouil quickly began retracing his steps as he saw one uniformed officer and three others in civilian clothes get out and run to the front of the house, bursting in through the unlocked door. Tearing through the lounge and up the short staircase to the first floor, they were shocked to come face to face with Peulevé and his team in the front room, standing around a wireless set screwed down on a table. Peulevé immediately tried to burn his silk codes in the stove but was dismayed to find that they would not catch light, while Bertheau, in mid-transmission, had the presence of mind to tap out ‘nous sommes pris!’ (we are taken) before raising his hands. Delsanti made a frantic attempt to jump out of the window, but their situation was hopeless. Having been taken completely by surprise, there was now no chance of escape.

None of them was armed (though the wardrobe in the room concealed a number of guns), and the SD officer quickly ushered them down the stairs and into the back garden, leaving one of his men to guard them whilst the rest of the house was searched. As they waited one of the Lamorys’ neighbours, a milicien named Adrien Dufour, began shouting abuse over the fence behind them and it soon became clear that he had been responsible for tipping the Germans off. Believing Peulevé to be the head of a group of Jewish black marketeers, he had been only too aware of the frequency with which people had recently been visiting the house. In fact, many in the neighbourhood had avoided walking past number 171 since Bertheau's arrival at the beginning of March, having been suspicious of the numerous strangers who would park their cars outside at night (some had already guessed its connections with the Resistance and even begun to refer to it as ‘La Maison des Anglais’).1 As Poirier had feared, a simple lack of precaution had finally led to their discovery.

Having expected to find nothing more than a few small-time criminals dealing in contraband liquor, Walter Schmald was completely confounded by the sight of these résistants caught in the act, though he was even more surprised to see Peulevé among them, recalling how they had become acquainted in Brive some weeks before. Schmald's glee was evident and Peulevé even congratulated him on making such an important haul, but he was furious with himself for being the one responsible for this catastrophe, having been temporarily distracted from the window during the few crucial seconds when the two cars drove up.

Once the search was completed Schmald was keen to get his prisoners as quickly as possible to Tulle and the four of them were marched to the gate with their hands on their heads. Split into pairs, Peulevé and Roland Malraux were hustled into the dickey-seat of one of the Citroëns; thankful that they had not been handcuffed, Peulevé was at least able to dispose of some of the incriminating papers he was carrying by stuffing them behind the seat, though he knew that other messages and codes would have been found during the search of Bertheau's room.

They were immediately driven to the Waffen-SS barracks in Tulle, where a brief interrogation included questions relating to one of the directors of Bloc-Gazo, a Jew named Roger Lang. Peulevé said that he knew nothing of him, attempting to try and pass himself off as an escaped British POW trying to make his way to Spain with the help of the Resistance. He knew this story wasn't likely to hold up since he had had no opportunity to get his story straight with the other three, but thought that it might buy them some time.

They spent the night in Tulle, being driven the next morning to the Gestapo HQ in Limoges. Using a translator, Peulevé was first questioned by SS Obersturmführer Joachim Kleist, who began with the wireless messages found at the house. It soon became impossible to maintain his initial alibi and he was eventually forced to admit that he had been sent to work in France with the Resistance. He also declared that his mission was to arrange landing grounds for paratroops and gliders after D-Day, which appeared to satisfy his interrogator. The Gestapo officer then presented him with material showing the extent of the Germans’ understanding of SOE and its networks, including pictures of Prosper (Francis Suttill, with whom he had trained at Wanborough Manor and Meoble Lodge) and members of his circuit based in and around Paris, maps of the areas in which they operated and details on several STS training schools in England. Peulevé was unflustered by this, knowing that it would not have been difficult to obtain information on SOE schools from other captured sources, though he could not be sure about the other evidence.

After this session Peulevé was taken to Limoges jail, where he rejoined his companions. They used the limited time they had together to work out a rudimentary cover story, largely based on the premise that Peulevé was the W/T operator, with the other three acting as nothing more than agents de liaisons. The next afternoon all four men were taken to the Gare Bénédictins and put on a train for Paris; during their journey one of their guards made light of Peulevé's situation, saying that he would be most likely exchanged for a captured German agent in England. However, given the circumstances of his arrest he knew that the Gestapo were likely to try and get as much information out of him as possible.

On arrival at Austerlitz station Peulevé was immediately taken to Avenue Foch, a grand, tree-lined Haussman boulevard leading from the Arc de Triomphe toward the Bois de Boulogne. Numbers 82 to 86 had become the main headquarters of the German counter-intelligence services and Peulevé was escorted through the gates of the luxurious balconied villa at 84, used by the SD for interrogating foreign agents. Having been separated from the others, he was led up the elegant marble staircase and into a room on the second floor where two men were waiting, the taller, white-haired one being Dr Josef Goetz, originally a languages teacher who now acted as a specialist within an SD sub-section dedicated to wireless counter-espionage. Goetz wasted no time in asking about the codes and messages found at the Lamory house and soon began pressing him for information on where other radio sets could be found. Having claimed to be the only wireless operator in the group, Peulevé maintained that all his equipment had been captured at the house (as he knew that two silks and two wireless sets would have been found in the first-floor room, this would seem at least plausible). Goetz seemed to be taken in by this story, although a closer examination of Peulevé's clothing would have changed his mind, as he was still carrying another silk sewn into his trousers.

Once the interrogation had ended Peulevé was removed to one of the dozen cells on the top floor of the house which had originally been used as servants’ quarters; inside he found a box of clothes, which to his surprise appeared to have been issued to another SOE agent. An hour later he was called for again and as he walked past the guardroom he caught a glimpse of a man next door working on a drawing, instantly recognizing him as John Starr (Bob), another F Section agent whom he had known in London. Unfortunately he didn't get a chance to talk or signal to him, instead being taken into an office occupied by a forty-year-old SD auxiliary named Ernst Vogt, who worked as a translator for the Commandant, SS Sturm-bannführer Hans Kieffer. As a result of his success with previous interrogations of F Section's agents, Kieffer had allowed Vogt to conduct interviews without him being present.

Introducing himself as Ernest, his manner was relaxed, offering Peulevé cigarettes and other items clearly captured from parachute drops, suggesting tacitly that RAF supplies were falling regularly to German reception committees rather than French ones. Vogt also told him that if he cooperated and told the truth, a military tribunal and probable execution could be avoided. To emphasize that SOE was now completely compromised, he produced photographs of various agents known to Peulevé from the PROSPER network, the same ones that he had seen from the Gestapo in Limoges. Despite Peulevé pleading ignorance about these individuals Vogt doggedly continued with his approach, referring to specific details concerning the STS schools and their staffs, as well as dropping the names of several F Section officers. As with the Limoges interrogation, Peulevé was asked when he had last seen Prosper, though he continued to deny any knowledge of him.

The subject of Francis Suttill and the collapse of his circuit has become one of the most contentious aspects of SOE's history. Born in 1910 at Mons-en-Baroeul near Lille to a French mother and English father, Suttill became a successful London barrister in his twenties before joining the East Surrey Regiment at the outbreak of war. F Section quickly identified his sharp intellect and impressive leadership abilities during selection at Wanborough, and he dropped into France in October 1942 with the objective of building a new Paris circuit to replace the ill-fated AUTOGIRO, which had collapsed earlier that year. Under the code name of Prosper (possibly taken from the name of a fifth-century saint) he quickly began gathering support in the areas around Paris, assisted by female agent Andrée Borrel (Denise) and W/T operator, Gilbert Norman (Archambaud). It did not take long before Suttill was ready to begin receiving supply drops and by spring of 1943 the reach of his PROSPER circuit spread across twelve departments, being assisted by an increasing number of smaller sub-networks including JUGGLER, BUTLER, PRIVET and PUBLICAN. Henri Déricourt's FARRIER also received additional F Section agents by Lysander and Hudson to manage this rapid expansion, and Déricourt had personal contact with Suttill as well, using his wireless operators to coordinate air operations with London.

In April the SD made a significant breakthrough when they arrested Germaine and Madeleine Tambour, two sisters whose names had appeared in André Girard's CARTE dossiers, stolen from André Marsac's briefcase in November 1942. In addition to working for Girard, the Tambours had also acted as a letter box for members of PROSPER, which obviously presented a serious security threat for Suttill. He made two desperate and unsuccessful attempts to try and free them before being recalled to London in May, during which time he declared his suspicions about the loyalties of both Déricourt and Bodington. Déricourt had no part to play in Suttill's return to France on the night of 20/21 May, but the arrests of several PROSPER agents a month later led the SD to the addresses of its key members, and on the eve of Saint Prosper's feast day, 24 June, Suttill, Andrée Borrel and Gilbert Norman were all arrested and taken to Avenue Foch.

In Vogt's retelling of the story, he mentioned that Suttill had refused for a long time to divulge any details of relating to its networks, but had finally broken his silence when he was shown copies of PROSPER mail passed to the SD by Déricourt:

When the Gestapo produced a photostat copy of a report that this agent [Suttill] sent to London giving all details of his circuit, this agent had then said to the Gestapo ‘Well since you know everything I am prepared to answer any questions.’ The Gestapo told him that in exchange for any information this agent could give as to the location of arms dumps or his sub-organizations, the Gestapo would guarantee the lives of everybody who was working for him providing they agreed to deliver the arms they had in their keeping to the Gestapo without resistance… They [Vogt] told me that in many cases the presence of Prosper with them in visiting these arms dumps helped to convince the people that it was all over and that it would be better not to resist. They then told me that Prosper had concluded a pact with them, that his life and all subsequent agents arrested would be guaranteed providing these agents were willing to deliver the arms they had in their keeping. They said that this was an agreement with the chief Headquarters in Berlin. They told me that Prosper was in a camp in Germany.2

There is no definitive account of exactly what occurred in those last days of June, but it seems that Kieffer may have obtained the cooperation of Gilbert Norman, and that Norman could have also been brought in during Suttill's interrogation to persuade him to talk.3 Whether or not anything was actually forced out of Suttill before his transfer to Germany will probably never be known, but either way the end result for PROSPER was unquestionably disastrous, with the number of arrests following the SD's investigations estimated at between four and fifteen hundred. The promises given by Himmler to spare the lives of PROSPER's agents subsequently proved to be worthless, and Suttill, Norman and Borrel would all later be executed in concentration camps.

In the light of this information, Peulevé decided that his best option was to admit to knowledge of Prosper but to fabricate another cover story. After Vogt had solemnly typed the fictitious details he gave regarding his date of birth, address and so on, he rang a bell. Soon afterwards Kieffer appeared, accompanied by Starr. Peulevé was at a loss as to what to make of his compatriot:

When I was confronted with Starr he immediately greeted me by saying ‘Hallo, old chap, how are you?’ This rather surprised me and all I could say to him was – ‘What is this racket?’ He replied – ‘It's not a racket, they have got me out of Fresnes [prison] to do drawings for them, but that is all.’ The look on the Gestapo man's face showed me that he obviously knew or would know that the details I had given them concerning myself were false.4

Put back in his cell on the fifth floor, Peulevé returned an hour later to the same room where Vogt was waiting for him. As he had predicted, Vogt said that he had wasted his afternoon on collecting his details, as they were all false. He then showed Peulevé his personal details on a sheet of paper, which to his astonishment were all correct. Vogt made it clear that an agent was working for them in Orchard Court, who passed the real identities of all F Section's people to the SD. Peulevé did not believe that this was possible, since even someone in Orchard Court would be unlikely to know every agent's personal details, though it was conceivable that the information came from Starr or another interrogated member of the Resistance. However, he did not see how he could continue to deny this information and admitted to it being accurate.

Vogt then started to ask about his circuit. A list of the locations of parachuting grounds had been captured from Lamory's house, which he proceeded to mark out on a map, telling Peulevé they would begin to search these areas for arms dumps, but Peulevé replied that there were no caches since all the arms were dropped directly into the hands of the maquis. Vogt wasn't satisfied and still believed that there must be arms somewhere in the circuit's territory; searching for something to offer him, Peulevé had the idea of giving an address of Arnouil's at Terrasson, west of Brive (Arnouil's cover was already blown and could not be compromised any further by this admission). He claimed that this was the location of the only arms dump he had, and was to be used in the event of a special job requested by London. This story was partly true, as a local farmer in Terrasson had been put in charge of a cache of AUTHOR's arms. However, some time later the farmer had mistakenly contacted another agent believing him to be a member of Peulevé's network – unknown to Peulevé, the neighbouring STATIONER circuit led by Maurice Southgate (Hector) had installed a maquis in the area, now commanded by one of his lieutenants, Jacques Dufour. Unconvinced that Peulevé and Poirier were SOE agents, Southgate had allowed Dufour's maquis to steal these arms for themselves, leaving nothing for the Germans to find. Peulevé knew that if this location was checked he could plead ignorance about the theft, and if interrogated the farmer would most likely back up his story.

Vogt's questions then switched to the whereabouts of maquis camps, but Peulevé maintained that he only met Resistance leaders at pre-determined times and places, and that his last meeting was supposed to have been at the railway station at Brive on the day of his arrest. As Vogt was getting frustrated he dredged up a couple of addresses of hotels and bars to placate him, claiming (falsely) that he had used them as meeting places in the past; this stalled him temporarily, but there was no shortage of other leads to follow up.

A number of wireless telegrams related to people who had given money to the Resistance, which Peulevé could do little to disguise and would probably result in the arrests of the donors. More worryingly, another message showed communication between Paul Lachaud and Bloc-Gazo, which aroused suspicions as to why a mill-owner would want to order so many spare parts from such a company (in fact this message was coded and referred to details of arms being held at the mill, not spare parts). Peulevé denied that Lachaud had any part in the circuit, though it was obvious that Paul and his wife Georgette were now in great danger.5

In one of the most recent messages London had mentioned the capture of a woman presumed to be a letter box, through which Peulevé could send on a report. Peulevé said that he had not used it, which was the truth, never having sent any mail since his arrival in September. As Vogt moved on to another telegram, both of them could hear the sound of footsteps running down the corridor towards them. A moment later the figure of Kieffer suddenly burst through the door. Staring at Peulevé, he asked, ‘Who is Nestor?’

After witnessing the events at Lamory's house, Arnouil had circulated news of the arrests as quickly as possible, mindful that Poirier would be in great danger when he returned from the Savoie. He drove to the Verlhacs at Quatre-Routes, from where Jean Verlhac sent word on to Hiller and then to his wireless operator Cyril Watney, who was able to transmit a message to London from a farmhouse near Saint-Céré in the Lot. On the evening of 23 March, Poirier was sitting in his mother's house at Saint-Gervais-les-Bains when she asked him to come and listen to the BBC messages personnels. Though muttering that he was ‘off-duty’ he nevertheless caught Watney's message: Message important pour Nestor: Jean très malade, ne retournez pas. Unfortunately the SD at 84 Avenue Foch were also keen BBC listeners, and it did not take them long to connect Jean with Peulevé.

Peulevé first denied any knowledge of what Kieffer was referring to, but was then given the BBC message in full, which also mentioned that Nestor (Poirier) should go to see Maxime (Hiller) or Eustache (Watney), another two names which the SD did not know of. Peulevé was now on the back foot and had to think quickly. He stated that Nestor had been parachuted to one of his grounds, but had then moved on and had no role within his circuit, though he had visited Bloc-Gazo. Maxime and Eustache he explained as being agents sent by London to help the Vény groups, though he did not give Kieffer addresses (in the case of Watney this would have been impossible anyway, as he had been careful enough to keep his location secret from almost everyone). None of the three would be arrested as the result of Peulevé's capture.

Still convinced that he knew more than he was giving away, the SD kept Peulevé for several more days at 84 Avenue Foch, during which time he was subjected to torture to divulge more information about the names in the BBC message and details about his circuit. In training, SOE's agents were told that they should try and hold out for forty-eight hours before talking, to allow sufficient time for safe houses to be cleared and arms dumps to be relocated, but Peulevé had no intention of giving up any remaining secrets. Poirier later commented briefly on his ordeal, mentioning that ‘he was half-drowned on several occasions’,6 referring to a well-known and feared form of torture known as the baignoire, which was particularly favoured by the SD and Gestapo. The process involved submerging the victim in a cold bath to the point of drowning, at which point they would be pulled out and revived, sometimes with schnapps. The questioning would then resume; if the interrogators did not get what they wanted, the process would continue. Unsurprisingly it was not uncommon for victims to end up being held under too long and ‘accidentally’ drowned using this method. Another SOE agent, Forest Yeo-Thomas, who will appear later, gave his own recollections of undergoing this torture:

I was helpless. I panicked and tried to kick, but the vice-like grip was such that I could hardly move. My eyes were open, I could see shapes distorted by the water, wavering above me, my lungs were bursting, my mouth opened and I swallowed water. Now I was drowning. I put every ounce of my energy into a vain effort to kick myself out of the bath, but I was completely helpless and, swallowing water, I felt that I must burst. I was dying, this was the end, I was losing consciousness, but as I was doing so, I felt the strength going out of me and my limbs going limp. This must be the end…7

Peulevé's own reference to the matter was typically modest, only mentioning that ‘I am certain the miseries they put me through were nothing compared with those that other people had suffered’,8 and gave a vague reference to undergoing ‘a few days of the traditional physical and mental softening-up process’.9 However, apart from repeatedly subjecting him to the baignoire, the SD also resorted to other medieval practices, placing matchsticks under his fingernails and also imprisoning him in a coffin-like box, perforated with ventilation holes; left in it for several hours at a time, he had to tense his limbs repeatedly in order to try and deal with the cramp it induced. Despite these brutal efforts to get him to talk he remained silent – the only information that Peulevé did give away was connected with the information that he, Delsanti and Malraux were already carrying, plus what Bertheau had left behind in his room.

Although these methods proved fruitless, German investigations back in Brive had fared little better. On the evening of 21 March, a résistant named Georges Michel had cycled to Arnouil's house on rue Edouard Branly, just a short distance from Lamory's address on the Route du Tulle. Unaware that Arnouil had already fled, Michel was taken by surprise when entering the house, finding Schmald and several of his men inside – having found Arnouil's name mentioned in Bertheau's telegrams, the SD had been waiting to catch anyone coming to warn him of Peulevé's capture. Schmald planned to take Michel to the SD headquarters at Tulle for interrogation, but first wanted to return to the scene of Peulevé's arrest where he and a section from the Légion Nord-Africaine (an SD auxiliary force made up of North African soldiers based at Tulle) continued searching and plundering the house. Whilst being held outside Michel was unexpectedly recognized by a milicien who had known him before the war, who approached Schmald to release him. Repeatedly vouching for his good character, Michel was eventually placed in the hands of the local chief of the milice who freed him shortly afterwards.

With Arnouil at large, Schmald decided to use Bloc-Gazo as a means of identifying more of his Resistance contacts and devised a strangely elaborate plot. Visiting a public notary in Brive, he transferred the shares of Arnouil and another employee, Max Fouhety, to Armand Lamory and SD informer Maurice Herbin, making them the company's senior directors. A friend of Lamory's before the war, Herbin had suddenly reappeared in Brive during February 1944, visiting Bloc-Gazo and even spending several days at Lamory's house, though there is no evidence that he was responsible for the arrest of Peulevé's group or that Lamory was also working for the Germans.10 Schmald appeared to believe that Herbin's position would enable him to gain intelligence on those using the premises for resistance purposes. However, although he was officially recognized by the rest of the Bloc-Gazo's board on 8 April, the SD's game was obvious and none of AUTHOR's contacts were caught as a result of this action.

After realizing Peulevé had been captured, Poirier made the decision to return to the Corrèze the following day, accompanied by his father who had just arrived at the house. Careful to get off the train at Quatres-Routes station rather than risk being picked up by the Gestapo at Brive, Jacques went to visit Jean Verlhac to find out what had happened. Making contact with Hiller at Verlhac's house, it was clear that Poirier was now the target of a manhunt – although the SD had not initially known who Nestor was, they eventually realized that he must be ‘Jacques Perrier’, whose false carte d'identité had been found on Peulevé (Poirier had given it to him in order to exchange it for a new one via Arnouil), and dozens of posters displaying his face were now being pasted throughout Brive and the surrounding areas.

Arnouil and Poirier tried to carry on arranging supply drops for the maquis but their journeys across the Corrèze put them at great risk and they were lucky to avoid arrest when they were stopped at a German roadblock carrying messages for transmission to London. At a meeting at the Verlhacs, Hiller relayed Buck-master's new instructions to Poirier appointing him the organizer of a new circuit named DIGGER, which was to carry on AUTHOR's work. However, this development was immediately overshadowed by the arrival of Georgette Lachaud, who arrived to tell them that Raymond Maréchal had just been killed.

Before his capture, Peulevé had arranged for Maréchal's strike force to attack a sugar factory, the plan being to steal 40 tonnes of stock destined for Germany. With Soleil's help, Maréchal took three trucks and an old ambulance through the back roads of the Dordogne and Corrèze in the early hours of 24 March, laying up near the factory around eight o'clock. At midday the raid was successfully carried out and the convoy immediately began making its way back, but soon the ambulance was lagging behind, labouring under the weight of 500 kilos of sugar and five passengers. Maréchal proposed to split away from the group and head for the bastide of Villefranche-du-Périgord, where he would drop his cargo at a friend's house before meeting up with Soleil the following day. Travelling over the Dordogne river towards Daglan, he could not resist calling in at the Moulin du Cuzoul to tell the Lachauds about their adventure, and his party ended up spending the night there. Waking late, they breakfasted before leaving for Villefranche at two o'clock that afternoon.

At the river crossing close to Maréchal's destination, a German column of thirty-five trucks had stopped en route to Bergerac, returning to base after an unsuccessful attempt to destroy a maquis training ground in the neighbouring Lot-et-Garonne department. Just as the soldiers were climbing back into their vehicles, Maréchal's ambulance turned a corner and ran into them, halting just a few metres from the nearest truck. Two of the group burst out of the back door towards the cover of a wood at the side of the road, shooting down three Germans as they made their escape under a hail of fire. Unfortunately those remaining were less fortunate: Maréchal was instantly cut down, being wounded in the chest and leg, and quickly taken prisoner along with his two remaining companions, driver André Fertin and another résistant from Alsace.

About an hour later the column stopped again outside the walls of the old English bastide of Beaumont, when two of the three SS men shot earlier died of their wounds. Throwing the three prisoners to the ground outside the Château de Luzier, a number of their enraged comrades began frantically kicking Fertin and Maréchal, even though both were unconscious from the beatings they had already received in the truck. A few moments later their battered bodies were riddled with bullets and left by the side of the road.

The Alsatian was taken for questioning at Bergerac and Périgueux, and several days later the SS carried out a raid on the Moulin du Cuzoul, on 31 March. Fortunately the Lachauds were absent and had moved any arms from the premises after Peulevé's arrest. However, the Germans were intent on exacting revenge in any way they could and burned their farm to the ground after savagely slaughtering their livestock.

Poirier decided that a split with Arnouil was necessary for the sake of DIGGER's security and moved into the Château de Siorac, the safe house owned by Soleil's friend Robert Brouillet. Known as ‘Charles the Bolshevik’, Brouillet was an uncompromising character but not without a sense of prudence, able to rely on his extensive network of local contacts to warn him of incoming German forces long before they reached the village. Continuing to stay in contact with London through Watney, Poirier arranged for two additional SOE agents to be dropped to a landing ground near Domme, and on 9 April Buckmaster sent him a highly capable weapons instructor, Peter Lake (Basil, soon to be re-christened with the more Gallic Jean-Pierre), accompanied by a studious-looking W/T operator, Ralph Beauclerk (Casimir).

With his new assistants in place, Poirier was eager to disappear for a few days and left for Paris, travelling with André Malraux who had meetings with the Conseil National de la Résistance. Having been prompted into taking an active role in the Resistance after the arrests of brothers Roland and Claude, Malraux went to offer his services and returned as the ‘R5’ district commander for the Forces Francaises Interieurs, a military body intended to integrate and direct resistance under de Gaulle's General Koenig (ever the self-publicist, Malraux also chose to adopt the nom de guerre of ‘Colonel Berger’ after Vincent Berger, a character from his novel Les Noyers de l'Altenbourg). Between April and D-Day, DIGGER and Malraux would work together to try and meet the ever-increasing demand for arms and manage the influx of young men eager to join the maquis.

Having failed to elicit any new information under torture, the SD transferred Peulevé on 3 April from Avenue Foch to Fresnes prison, on the southern outskirts of Paris. Built at the end of the nineteenth century, Fresnes was commonly used to incarcerate other SOE agents, Allied airmen, French resistance fighters and political dissidents, as well as ordinary criminals; from 1942 it also held women. Comprising three four-storey cell blocks with connecting structures at right angles, prisoners were exercised in the rows of small courtyards that lay in between. Although most of its cells were much like any other prison, Fresnes also had a number of dungeons downstairs which were used as a punishment or to break prisoners psychologically, and it was into one of these ‘cellules de force’ that Peulevé was first introduced. There are no first-hand details of what he experienced, though another account describes what conditions were like: ‘The floor was spongy and covered with fungus. The walls were clammy with moisture. Where the bed would have been there were only two iron clamps jutting out from the wall. There was no table. There was a w.c. pan but no tap.’11 As if this wasn't unpleasant enough, the cell was also completely dark. Aside from the news shouted out by the other prisoners, Peulevé's only human contact for the next two months was with the guard who brought his meagre soup ration.

On 8 June, he was at last dragged out and moved to one of the cells upstairs, which measured about 10 feet long and about half as wide, and was furnished with a folding iron bed, a small shelf, a toilet with a push-button tap above it and a small, high window of frosted glass. The rations were better, but still only consisted of a mug of dirty water which passed for morning coffee, and midday soup, accompanied by a small amount of bread and a piece of cheese or sausage. There was also occasional exercise in one of the small yards between the blocks, though prisoners were segregated during their time outside and all communication for those in solitary confinement was prohibited. Through his long ordeal Peulevé had done what he could to keep his mind occupied, ‘either dreaming of wonderful steak dinners, or, recapitulating with the aid of a piece of plaster chipped out of the wall, the theories of Pythagoras and other Greek mathematicians on the cell floor’,12 but his thoughts inevitably turned to Violette and what role F Section might have assigned her.

Although Peulevé had warned London not to send Liewer in March, another attempt had been made to infiltrate him and Szabó by parachute in early April, to assess the state of SALESMAN after the arrests of Claude Malraux and his colleagues. As Liewer was at risk of being recognized in Rouen he remained in Paris, sending Violette (operating under the name ‘Corinne Leroy’ and code-named Louise) to try and establish contact with the remaining members of the circuit in order to see what scope there was for rebuilding it. She spent three weeks visiting the addresses she had been given, but it didn't take long to ascertain that the situation was now hopeless. Although a fair number had avoided capture and could offer Louise information on what had happened, it was clear that the Germans had shattered SALESMAN, with nearly a hundred of its members now either dead or in custody. Making her way to Paris, she reported to Liewer on the results of her reconnaissance before they were both safely picked up near Issoudun on 30 April.

Violette had proved herself in the field and was promoted to the rank of Ensign on her return to London, though it was only a matter of days before she was requested to accompany Liewer once more, this time to restart a new SALESMAN circuit in the Haute-Vienne, adjacent to Poirier's newly established DIGGER. Having lost none of her desire to avenge her husband's death she agreed to go, even though it meant leaving her young daughter again. They left on the night of 7/8 June, parachuting to a landing ground near Sussac, south-east of Limoges, where they were received by the local FTP. Finding a lack of organization on the ground, Liewer sent Violette to ask for Poirier's assistance in the Corrèze, taking a headstrong maquis leader, Jacques Dufour (who had previously worked for Southgate's STATIONER) with her as a guide.

Travelling by car on the morning of 10 June, they picked up a young maquisard known to Dufour on their way, Jean Bariaud, before unexpectedly running into an SS roadblock about halfway between Limoges and Brive, outside the village of Salon-la-Tour – unknown to them, the Limousin was now swarming with troops from the SS 2nd Panzer Division Das Reich, searching for one of their officers who had been kidnapped the previous evening. Having left their base in Montauban two days before, the SS division's sprawling columns had been constantly nuisanced by SOE-backed sabotage and hit-and-run attacks as they lumbered north to meet the Normandy invasion, but the abduction of one of its battalion commanders, SS Sturmbannführer Helmut Kämpfe, by a local FTP maquis near Moissannes, a tiny hamlet just east of Limoges, had provoked an especially furious response. Within a few hours the SS had begun casting a net across the Haute-Vienne and Corrèze to catch the perpetrators, in the middle of which lay Salon-la-Tour, about 30 miles south of where Kämpfe's abandoned car had been discovered. (Kämpfe was to eventually meet his death at the hands of the maquis, but the events surrounding his final hours were never properly established.)

Leaving their Citroën behind, the unarmed Bariaud managed to make his escape across the fields while Violette and Dufour began returning fire. Pursued by soldiers and several armoured vehicles, they slowly retreated across a cornfield towards a nearby wood, but by the time they reached it Violette was completely exhausted and told Dufour that he must carry on alone. Although Dufour was able to hide with the help of a local farmer, Violette was eventually captured; transferred immediately to Limoges prison and interrogated by the Gestapo, she showed contempt for their questions and refused to give any details of her mission. Liewer planned an ambush to free her on 16 June, but she was driven off in a prison van to Fresnes before they could act, and now Peulevé and Violette were sitting only yards away from each other in adjoining cell blocks.

Expecting that it was just a matter of time before he was executed, Peulevé was somewhat surprised when on 14 July he was led out of his cell and locked into a cubicle inside a prison van, being driven back to Avenue Foch again for further questioning. As a result of the telegram that had mentioned a letter box in Lyon, the Gestapo had arrested the woman to whom he was supposed to have given his report, though she continued to deny any involvement. Peulevé was only with Vogt for a few minutes, after which he was allowed to visit Starr again, being shown into his room upstairs. Starr was unforthcoming when he asked for news on the Allies’ progress, preferring to talk about his artistic endeavours instead – Peulevé could see the results of some of it, as a few portraits of SD officers at Avenue Foch hung on the walls of his room. It was also clear that he was free to roam around the building, having given his word not to escape.

Starr had been at Avenue Foch for a year. Captured near Dijon as the head of ACROBAT circuit, he was brought to the SD headquarters during the collapse of PROSPER. Whilst under interrogation Starr had written the name of his network on a map, which had been enough to attract Kieffer's attention – Starr had been a poster artist before the war, and his skills were considered valuable enough to keep him on at Avenue Foch to copy maps and other documents. Life here was considerably more comfortable than a cell in Fresnes, but Kieffer was getting more than pictures from the arrangement and it was obvious that the presence of a compliant British officer might encourage other captured agents to consider talking.

In November 1943, Starr made an escape attempt with fellow prisoners Noor Inayat Khan (Madeleine), a descendant of Indian royalty who for several months had taken great risks to maintain F Section's only remaining W/T link amidst the wreckage of PROSPER, and Colonel Léon Faye, one of the heads of the French intelligence group ALLIANCE. Using a screwdriver pilfered whilst mending a vacuum cleaner, they loosened the bars of their cells and planned to break out together on the night of the 25th; Starr and Faye met as arranged but Khan had been unable to free herself, and consequently both men had to spend several hours removing the bars of her skylight before successfully pulling her up onto the roof. This delay proved fatal as a few minutes later the howl of sirens warning of an imminent air raid alerted the guards and Kieffer to their disappearance. Starr and his co-escapers managed to find their way into a neighbouring building, but by this time the surrounding area had been cordoned off and all were recaptured, Faye being wounded as he made a desperate bid to get away. Enraged by this act, Kieffer demanded that each give their word not to make any further escape attempts. Khan and Faye refused and were consequently sent to concentration camps in Germany.13 Starr, however, agreed and Kieffer decided to keep him.

According to Alfred Newton (Artus), another F Section agent held at Avenue Foch the same month, Starr made no attempt to dissuade agents from cooperating with the SD: ‘Star [sic] told me in English “Don't lead them up the garden it's quite useless, they know everything: this is the success of Orchard Court, you should see the lorries full of containers unloaded here in the back yard every day.“’ ‘14 However, Starr's apparently casual attitude had not been enough to sway Newton, who like Peulevé decided to keep his mouth shut, regardless of what the Germans might already know.

Peulevé was confounded by Starr's pledge to Kieffer and told him that he still should try to escape. He was even more amazed by his admission that on three occasions he had gone out to dinner with Gestapo officers and his statement that he preferred ‘living in Avenue Foch to breaking stones in Germany’.15 His assessment was that Starr was trying to outwit the Germans, but perhaps didn't realize the effect that his presence might have on other agents who might have seen him as a ‘living example of the way in which they [the SD] would keep their word’16 if they agreed to cooperate. Moreover, it could lead them to deduce that SOE was more of an open book to the enemy than it really was.

Transported across Paris back to Fresnes, Peulevé was led into the entrance hall with several other prisoners. Left unguarded next to a large crowd of visitors, he began thinking about a possible escape – as they had become so mixed up with those waiting to leave, he might be able to slip out unnoticed in their midst. When the group finally started to move along he followed, making it to the main gate where they began to form a queue – each visitor had been given a laisser-passer, which a guard was collecting as they filed out.

As Peulevé moved closer to the gate he saw that he would have to improvise and after handing over a scrap of paper he immediately made a run for it. By the time the guards realized what was happening he was halfway down the road, though several months as a prisoner had taken its toll on his fitness and his pursuers steadily began catching him up. In an effort to lose them he decided to try and scale a garden wall, but as he hauled himself up one of the guards took aim and hit him in the thigh. Although managing to clamber over, he found that his efforts had been in vain as the garden he had entered offered no obvious exit, and within a few moments the sentries had caught up with him. Put back in his cell he waited to receive some medical attention for his wound, but by the evening it became obvious that nobody was coming. As the bullet had lodged in his leg he knew something would have to be done and finally forced himself to remove it with the aid of a spoon, before passing out. Fortunately the wound did not become infected, though his physical condition would now make any escape impossible.

Despite this setback, Peulevé could at least still try to get word to people on the outside. Giving messages to prisoners who were being released, he wrote to the Verlhacs, his friend André Girard in Cannes and Madame Faget in Bordeaux, signing all of the letters ‘Henri Chevalier’. This last one was received and SOE in London were notified through a wireless transmission from Roger Landes, who had returned to Bordeaux as head of a new circuit, ACTOR, in March. Peulevé also used the Fagets’ address on a Red Cross form, in order that he could receive toilet articles and underclothes.

In the months following his arrest Peulevé's parents had continued to receive the usual reassuring letters from the War Office, stating that he was safe and in good health. However, at the end of July a telegram arrived to report that he was missing, followed by a request for Leonard and Eva to visit London to obtain further news of their son. Annette went with them and recalled what happened:

The young major very guardedly told us that they now knew Henri had been in a fight with the Germans, and could only have been killed. I tried to convince the officer that my brother must be alive, that he knew France and was no doubt sheltering with some villager or other. But neither my parents nor the major would accept this. His possessions and clothing were sent home. Mother was too upset to pack them away, so I went and did it, even more convinced that he would need them again.17

The evidence of Peulevé's death probably came from a W/T message sent by Poirier on 7 August: ‘From Nestor/Peters: Sorry to inform you that learnt from unconfirmed source that Jean executed by Germans.’18 The ‘unconfirmed source’ may well have been someone in Fresnes who assumed that Peulevé had been killed whilst escaping, or from contacts Poirier made in Paris during his trip with Malraux in April; that F Section presumed the worst is unsurprising in the absence of any other information.

On the morning of 8 August, Peulevé's cell door was opened earlier than usual. The warder told him that he was leaving that day, and after waiting months for a trial he now half-expected to go directly before a firing squad. A reluctance to depart prompted a few blows from the Sergeant, and Peulevé soon found himself joining a line of prisoners on the narrow walkway outside, many of whom he recognized from London. Whispering between themselves, it seemed that most harboured similar thoughts about their fate, predicting that the Allies’ advance towards Paris would probably hasten their execution. Handcuffed in pairs, Peulevé was partnered with another young W/T operator for the MINISTER circuit, Denis Barrett, and moved outside with the others towards a bus near the main gate, where a smaller group of French women prisoners was also waiting to leave. As they queued up, Peulevé was shocked to see the face of Violette amongst them, bedraggled but still apparently in good spirits, though they only had time to acknowledge each other briefly before she and the other chained women were boarded onto a separate vehicle.

Both buses made their way to Gare de l'Est, where they were joined by other prisoners from the transit camp at Compiègne, Avenue Foch and the Gestapo HQ at Rue de Saussaies. Once assembled, Peulevé and thirty-six other men were put on a carriage and divided into two compartments with grilles over the windows, guarded by a number of feldgendarmerie (German military police) and an SD officer from Avenue Foch named Haensel who would supervise their journey. Each compartment was only intended to accommodate eight passengers and the overcrowding made it extremely uncomfortable in the August heat.

Command of the group was quickly assumed by Squadron Leader Forest Yeo-Thomas (Shelley), with Maurice Southgate (Hector, STATIONER's head captured in May) and Henri Frager (Louba, Carte's chief of staff in 1942) acting as his assistants, and a young French agent, Stéphane Hessel (Greco), as his German interpreter. A stocky, terrier-like figure in his early forties, Yeo-Thomas was the deputy head of the Gaullist RF Section and a veteran of two important missions, helping to support the work of Jean Moulin and socialist Pierre Brossolette in unifying resistance across the occupied zone. He had returned to France for a third time in February 1944 to attempt to free Brossolette, who had been captured whilst trying to return to England earlier that month, but ‘Operation Asymptote’ proved to be disastrous: Brossolette decided to take his own life before divulging anything to the Germans, throwing himself from the fifth floor of 84 Avenue Foch, and Yeo-Thomas was betrayed and arrested at Passy metro station on 21 March, the same day as Peulevé. Although not the oldest member of the party Yeo-Thomas had a natural authority about him, organizing the others to make best use of the space they had and obtaining permission from the guards to visit the toilet in pairs.

After leaving Paris the train moved slowly east, travelling through the night. No food or water was provided and soon all of them were beginning to suffer dehydration in the intense heat. As they neared Châlons-sur-Marne on the afternoon of the next day they heard several aircraft approaching and a few seconds later a sudden explosion and bursts of cannon fire from RAF fighters rocked the carriage, bringing it to an immediate halt. The guards began shouting in the corridors as they attempted to set up machine guns by the side of the train, whilst the prisoners stayed locked in their compartments, unable to do anything other than pray that the aircraft didn't make another run.

In the midst of the confusion Peulevé saw that three men in his group were suffering seizures, brought on by the privations they had already endured during their captivity. However Violette, accompanied by fellow agents Denise Bloch (Ambroise) and Lilian Rolfe (Nadine) had managed to avoid the gunfire and crawled along the floor in order to bring water to the men in both compartments. In recounting the incident, Peulevé was later quoted as saying, ‘I shall never forget that moment… I felt very proud that I knew her. She looked so pretty, despite her shabby clothes and her lack of make-up – she was full of good cheer.’19 This act by the three women also made a deep impression on Yeo-Thomas: ‘Through the din, they shouted words of encouragement to us, and seemed quite un-perturbed. I can only express my unbounded admiration for them and words are so inadequate that I cannot hope to say what I felt then and still feel now.’20

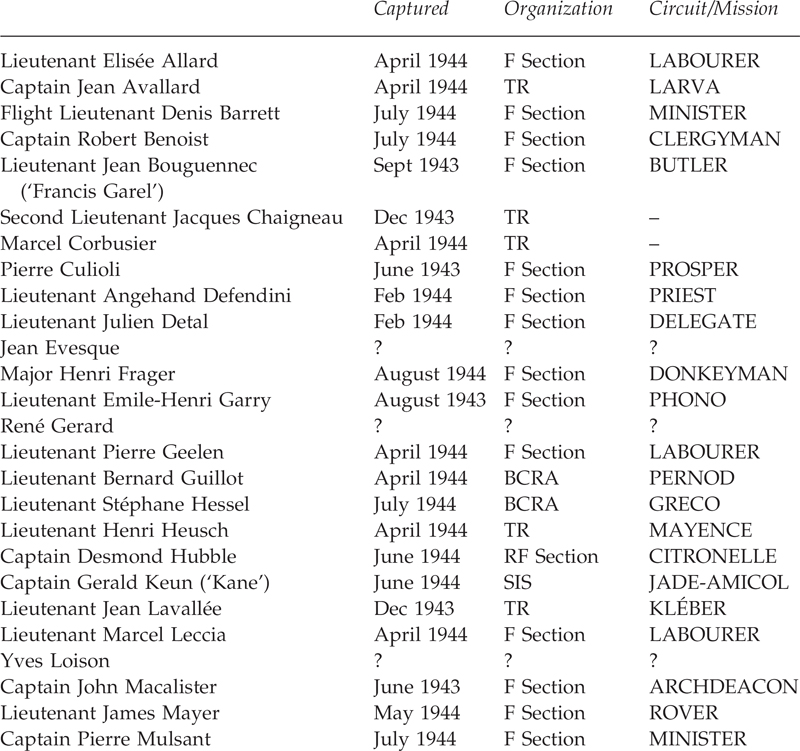

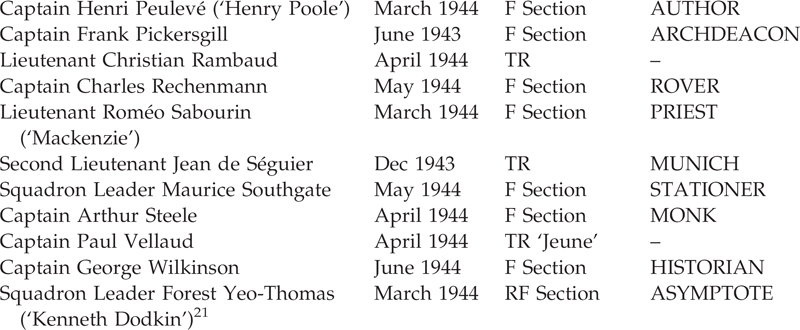

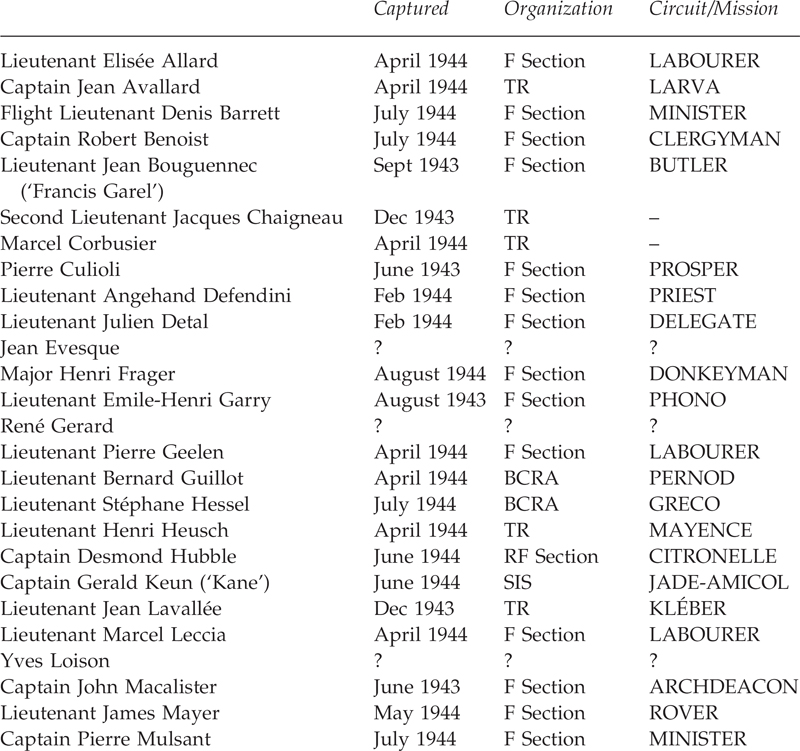

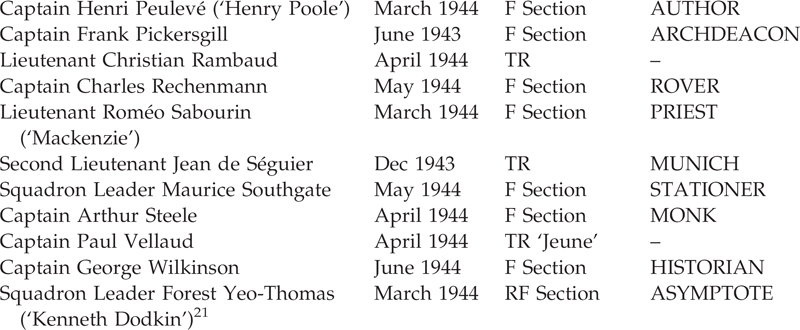

The train remained motionless for several hours after the raid, but eventually the prisoners were released from their carriage and shepherded into the back of two requisitioned trucks to continue the journey, being told that if any prisoner tried to escape, all would be shot. Yeo-Thomas took the opportunity to take note of the men assembled with him; the group included the following (aliases are shown in brackets):

Believing the officer's threat of execution to be a bluff, Peulevé still planned to escape and Barrett agreed to join him. Using a watch spring he managed to pick the locks of their handcuffs and made preparations to jump from the lorry, but at the last moment they were stopped by a number of the others, who maintained that they would endanger the lives of the group by doing so.

By the evening they reached Verdun, where they were taken from the trucks and placed in stables, the men in stalls on one side, the women on the other. Although they were forbidden from meeting, the darkness of the alley allowed Peulevé to get close enough to talk to Violette without the guards noticing. Peulevé's only reference to their reunion was quoted some time later:

We spoke of old times and we told each other our experiences in France. Bit by bit everything was unfolded – her life in Fresnes, her interviews at the Avenue Foch. But either through modesty or a sense of delicacy, since some of the tortures were too intimate in their application; or perhaps because she did not wish to live again through the pain of it, she spoke hardly at all about the tortures she had been made to suffer. She was in a cheerful mood. Her spirits were high. She was confident of victory and was resolved on escaping no matter where they took her.22

The next morning they wearily made their way in the summer heat towards Metz, stopping at the town's Gestapo headquarters. After several hours of waiting they were put into German trucks and driven further east, passing the forlorn sight of the Maginot line and finally arriving at a camp entrance just inside the German border at Saarbrücken; this was Neue Bremme, a straflager or punishment camp that mainly served as a transit point for Jews, Resistance workers and criminals who were destined for concentration camps. Though surrounded by barbed wire and machine-gun towers, Neue Bremme had virtually no facilities, consisting mainly of wooden huts, a rudimentary kitchen and a parade ground, in the middle of which sat a large tank of green, slimy water.

For the new arrivals there was an almost palpable change of atmosphere as they passed through the gate. After the trucks had stopped the men were violently ousted amidst a cacophony of shouts and insults, while Violette and the other women were led off to another area of the compound. Aided by several NCOs, the guards beat and kicked the first few of Peulevé's group as they descended onto the square, continuing with this treatment as they were made to line up. It became immediately apparent that the SS who ran the camp did as they pleased, though Hessel wasn't expecting such a harsh reception: ‘It gave us a real shock, because of course we were very naïve… we were convinced that this was the end, that Paris would be shortly liberated, that the war was practically over.’23

After the line-up the men were chained by the ankle in groups of five and ordered to run round the pond. This sight initially caused laughter to spread across the whole group, as being shackled together in fives made any coordinated movement virtually impossible, though the guards swiftly put a stop to their enjoyment of the bizarre spectacle. This practice was a common initiation and known in some cases to carry on for hours, though on this occasion their overseers quickly tired of the game and the party was led off to the foetid latrine, the use of which required some ingenuity with one or two coming very close to falling in.

Having undergone their brief introduction to the camp, they were once more chained together in twos before being locked in a small hut close to the camp's kitchen. Peulevé describes it as being 12feet square, though Yeo-Thomas and Hessel both recall it being even smaller, with one small window and narrow benches running around the sides of the walls; the only other furniture was an oil drum in the corner, to serve as a latrine. Thirty-seven men in such a small space was uncomfortable, but compounded with the stifling heat, lack of water and the stench from the oil drum the conditions were soon unbearable. An arrangement had to be worked out in order to make the most of the room they had, which ended up with about two-thirds of them sitting on the benches, eight lying on the floor and the remainder standing, leaning against the wall as best they could. They would have to endure this appalling situation through the rest of the day and a very long night before being released.

When morning eventually came the group was brought out to witness the roll-call, a pitiful spectacle and their first real glimpse of what might lie ahead for themselves. Peulevé noted what the long-term effect of this camp appeared to have on its inmates:

Living out every moment of their lives like hunted animals, they had become like it in appearance, their features were animal, bestial. Some of them had been eminent men, leaders of European thought and art; their only thoughts now were how to scrounge more food and avoid a blow. I saw something, too, of the reactions of the SS, handpicked sadists let loose to vent all their lowest instincts on helpless prisoners. My initiation into concentration camp life was beginning.24

They were also acquainted with the camp's water supply, the filthy tank in the middle of the camp, where they attempted to wash despite still being handcuffed. Afterwards, they were taken to the kitchen to sample the camp's rations: a thin mangel-wurzel soup and sawdust bread, which they ate while witnessing what Peulevé referred to as ‘one of the lighter forms of the SS idea of fun’.25 Having stationed SS guards behind the doors of the huts, a whistle would call out the prisoners, who each received a blow on the back of the neck as they rushed out; two blasts on the whistle would then dismiss them back to the huts before this ‘fun’ would begin again.

How long they actually stayed at the camp is not clear, though Peulevé states it was four days, which is corroborated by the report of another prisoner, Guillot. When brought out from the hut for the last time, they were handed over to an SD officer accompanied by a dozen Feldgendarmerie guards; locked into prison vans, they were then driven to the station in Saarbrücken and loaded onto a goods train. Only three guards were assigned to watch over them and the door to the truck was left open, assuming that handcuffed prisoners would not be so stupid as to try and jump from a moving train whilst attached to another man.

Yet several in the group were still willing to try any possible means of escape. Loison had managed to unfasten his own handcuffs and, whilst keeping a careful eye on the guards, began to free the others. A rough plan was devised to despatch the guards when night fell, after which small groups of them would jump from the train to make their way back to France. Unfortunately some of the prisoners still believed that they were bound for a POW camp and were so intent on preventing the plan that they threatened to warn their captors. For the second time Peulevé saw his chance of freedom being foiled by people he should have been counting on, and in the end there was no choice but to abandon the idea and replace their handcuffs, waiting to see where they would be taken next.

By dusk they had passed through Ludwigschafen and Frankfurt, finally stopping at Kassel where they were transferred onto another train. This time they were given a proper third-class carriage, prompting some of the group to think that perhaps they really were going to be treated as prisoners of war. Hessel asked a German officer about their destination and received a glowing report of the conditions at Buchenwald: ‘There is a fine library with books in all languages, concerts on the square every night, a cinema, theatre and even a brothel. There is a finely equipped hospital and the food is very good; you get practically the same as the civilians.’26 On reflection Peulevé later commented, ‘I don't think the Captain was trying to fool us; probably, like many other Germans who had never been inside the camp, he believed Goebbels' story that it was a sort of prisoners' paradise.’27 However, Hessel had heard very different reports about this place – a number of his left-wing friends had been political prisoners at Buchenwald in 1937 and 1938, and only survived by buying themselves out. Remembering the grim stories they had told him, he now knew something of the brutalities they were likely to face.