Normal Eating

In a world enamored with restricting food—both the amount and the variety—combining the words normal and eating can be confusing. What is normal anyway? You have probably heard “normal eating” used alongside the names of popular diets, but we assure you that diets are far from normal. On the road to recovery from almost anorexia, we suggest a two-phase approach to normalizing your eating. The first phase focuses on external cues. Eating at regular intervals throughout the day (such as breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks) and reducing any bingeing and purging are the main goals of this phase. The second phase focuses on internal cues—called “intuitive eating.” This is a nondiet approach to food first described by dietitians Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch in their book of the same name. Broadening your food choices and honoring your true likes and dislikes during this intuitive phase will help you to break the rigid dietary rules that keep you imprisoned.

As young children, we learn to eat based on external cues. We might wake up for breakfast at 7 a.m., because we have to be ready for the school bus at 8 a.m. We then eat pizza for lunch just because it happens to be what is served in the cafeteria. At the end of the day, we might sit down for a home-cooked dinner and eat what our parents serve. Unfortunately, individuals with almost anorexia have typically lost touch with this once-familiar eating pattern. Instead of eating by the clock, they may eat (or not eat) primarily to manage their shape, weight, or emotions. If you have been bingeing (like Abriana), purging (like Camille), or juice fasting (like Taylor), the first phase of normalizing your eating is to structure it—just like you did as a kid.

A basic structure for eating includes breakfast, lunch, dinner, and a couple of snacks. As a rule of thumb, try not to go more than four hours without food.1 The optimal timing of eating will depend on your daily schedule. For example, a busy working mom might eat breakfast with her kids at 6 a.m., lunch at work at 11 a.m., a snack at her desk at 3 p.m., and dinner with her family at 6 p.m. and then share a bowl of popcorn with her husband at 8 p.m. after the kids have gone to bed. On the other hand, a college student might sleep late and have breakfast at 10 a.m. before class, lunch at 2 p.m. after class, snack after sports practice at 5 p.m., dinner at the dining hall at 8 p.m., and an evening study snack at 11 p.m. Adhering to her own personalized structure helped Taylor avoid the juice fasting that often triggered her peanut butter binges.

Certain rituals at mealtimes can help you create this pattern. People tend to binge at places other than the kitchen table—possibly at the refrigerator door, in the car, or even on the bathroom floor. So, for many, creating a comfortable place to sit down at the table is important. You might consider lighting a candle or playing music. Say a prayer if you think this might help you to connect with some serenity. When Ed screamed in Jenni’s ears at mealtimes, a quick prayer often turned down the volume and—even if just a notch—brought her closer to peace.

Sharing meals with significant others may also help you normalize your eating pattern. In a large-scale study of adolescent girls, eating five or more family meals per week was associated with a reduced risk of developing disordered-eating behaviors five years later.2 Similarly, leading treatments for anorexia enlist mealtime support from both parents and partners.3 Knowing that you are accountable to someone who cares about you can make all the difference. In Brave Girl Eating, Harriet Brown wrote about refeeding her anorexic daughter, Kitty, who was quite vigilant about whether her parents were watching her at mealtimes. Harriet recalled, “Kitty asks again and again whether we’re watching, and I know she’s really asking: You’re making me eat this, right? I don’t have any choice here. Do I? She needs us to take the responsibility for her eating because the compulsion not to eat is still so powerful.”4 Not all people who struggle with disordered eating require this intense level of support, but everyone does, in fact, need some support around food. Find what works best for you or your loved one.

If you are reading this book, you probably already spend a lot of time thinking about calories and carbs. Dr. Thomas typically finds that her patients are just as knowledgeable about nutrition as she is (if not more so!). The problem is that they obsess over the details rather than putting broad principles into practice. At the height of her illness, Jenni knew exactly how many fat grams were in a slice of cheese, but she would never let herself add one to a sandwich.

That’s why we are not going to tell you what to eat. When you eat is much more important when you first start out to change your eating. If you are genuinely curious about which foods are healthy for you, we invite you to visit the Harvard School of Public Health’s Nutrition Source website (www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource). Based on the latest scientific research, physician and nutrition researcher Walter Willet and his colleagues have created a healthy eating guide comprising a combination of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, proteins, and oils. But even these are just guidelines. Please don’t fall into the trap of replacing one set of rigid rules with another. To help in the food department, consider seeing a registered dietitian who has experience in treating patients who struggle with disordered eating. During her recovery, Jenni found dietary counseling to be invaluable.

When selecting what to eat, try to anticipate how long the meal or snack will satiate you. Clinical psychologist Linda Craighead, author of The Appetite Awareness Workbook, has suggested a two-hour rule: “Each time you eat, eat enough so that you are not likely to be biologically hungry for at least two hours.” For example, “It is important to understand that one piece of fruit is not an adequate snack. It will not keep you from being hungry for two hours.”5 In other words, try some peanut butter with that banana!

An important caveat with food is that individuals who have been eating very little and/or are extremely underweight are at risk of refeeding syndrome, a potentially fatal complication of increasing energy intake too rapidly. If any of the following apply to you, consult your physician before attempting to normalize your eating:

The reason we recommend starting with external cues is that, in early recovery from almost anorexia, you and your body might not trust one another. Maybe you haven’t given your body food in a balanced way for so long that it doesn’t know—from meal to meal—whether you are going to starve or stuff it. When you do eat, you don’t trust what is going to happen. Will my body’s ravenous hunger lead to bingeing? Will my body hold on to every calorie in fear of my never feeding it again? In other words, according to dietitian Evelyn Tribole, coauthor of Intuitive Eating, when you have almost anorexia, your “satiety meter is broken.”7

At least part of the reason is biological. Disordered eating often leads to delayed gastric emptying. In one study, it took women with anorexia six hours for a standard test meal of pasta with meat sauce to exit their stomachs, whereas it took less than four hours for healthy controls.8 No wonder that, in another study, 89 percent of patients with almost anorexia and other eating disorders complained of nausea and/or abdominal bloating after eating an ordinary-size meal.9 Jenni remembers this painful sensation all too well. After eating a normal lunch in her early recovery days, it felt like the food was sitting in her stomach forever, not moving. Five hours later, when others were hungry for dinner, she still felt completely full, as if she’d just eaten.

But we aren’t letting you off the hook. You still have to eat to get better. Gastric emptying time typically speeds up as food intake normalizes. In other words, it takes time, but you can reconnect with your body’s signals, including hunger and fullness cues that tell you when to eat and when to stop. You will also begin to get a sense of what types of food your body is craving. Just making an effort to be conscious of your body’s signals is a step in the right direction. In the beginning, this might mean that you attempt to pay attention but that you hear absolutely nothing—radio silence. That’s okay. Simply paying attention is key.

One of Jenni’s favorite sayings is Do the next right thing. This has become a motto for many people trying to normalize their eating. Having slipups and setbacks along the way is expected. The important thing to remember is to get back on track as soon as possible. That means right now, not tomorrow.

Doing the next right thing and all-or-nothing thinking cannot coexist. Remember Abriana? If she ate just one morsel of food beyond her “diet plan,” she thought she had blown it, so she just went ahead and binged for the rest of the day. Telling yourself that you’ve already “messed up” and therefore have permission to “mess up” more will only continue the disordered-eating cycle. It won’t help keep you on track. Abriana eventually realized that one “extra” bite of food wouldn’t negatively affect her body and that the best strategy for getting fully better from disordered eating was to always eat the very next meal or snack in a balanced way.

In Jenni’s experience, the hardest cycle to break was “making up” for a binge. When she binged, Ed would say, in no uncertain terms, that she must make up for it. And as long as Jenni listened, she wasn’t getting better. Not making up for a binge by purging or fasting seemed unthinkable. But it wasn’t. It was just extraordinarily uncomfortable. Doing the next right thing—not purging and eating the next meal after a binge—meant feeling bad for a while. But in the long run, it is what broke the cycle of disordered eating and what led to feeling good. No, make that feeling great.

Trying to restrict your food to “make up” for a binge might sound like a good idea at the time, but research suggests it only perpetuates the binge-diet cycle. In one study, women with bulimia nervosa were asked to record when they binged and the extent to which they restricted their calorie intake each day during a two-week period. The more they restricted, the more likely they were to binge that same day, and even the next day—twenty-four hours later.10 Just telling yourself you are going on a diet tomorrow can cause you to overeat tonight; this is a phenomenon psychologists call the “last supper effect.” In one study, chronic dieters ate more cookies in a fake taste test when they were assigned to start a reduced-calorie diet immediately afterward than those who were not being asked to go on a diet.11

Normal eating means that from time to time you eat just because you are happy, often wanting to share the moment with someone else. At Dr. Thomas’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s themed bridal shower, her best friends Emily and JennyBess baked her a platter of cupcakes designed to look like gift boxes from Tiffany and Co., with pale blue frosting and little white bows. Even though she wasn’t especially hungry, she still ate two! Normal eating also means that you might eat for comfort sometimes when you are sad or lonely. But the key words in those last couple of sentences are “from time to time” and “sometimes.” We all eat based on emotions occasionally, but using food to deal with feelings on a regular basis lies at the heart of almost anorexia.

Food is fuel, not a coping mechanism for life. When Jenni’s treatment team first told her that she was using her eating disorder, in part, to starve and stuff away feelings, she didn’t believe them. Only when she stopped stuffing and starving her body with food did she eventually see and feel the truth. Intense emotions rose to the surface, and in the beginning, it felt awful. Like many people in this phase, Jenni wondered, Why did I recover just to feel this bad? But this was, in fact, just a phase—not the end of the journey. Jenni learned other ways to cope with feelings, like calling a friend, writing in her journal, and simply being present. Eventually, she learned to experience the feeling, knowing that if she did, it would eventually pass.

In women with bulimia, negative emotions—such as guilt, fear, and sadness—increase in the four hours leading up to a binge, purge, or binge/purge episode, and decrease in the four hours afterward.12 In other words, bingeing and purging are powerful emotion-regulation strategies. You wouldn’t be doing them if they weren’t so effective. To break the cycle, you will need to brainstorm a list of alternative ways to manage difficult feelings. Here are some ideas that Dr. Thomas’s patients have found effective:

No longer using food to manage your emotions is tough, but Kaitlyn was able to do it.

I wonder if my birth parents were like this with food? Kaitlyn wondered, as she carefully counted the number of grapes equaling one serving and placed them one by one into a sandwich bag for lunch. While she deeply loved her parents who had adopted her from Korea at birth, their carefree and relaxed attitude toward food had always been just one more reminder that she didn’t quite fit in—anywhere. Years out of high school, at age thirty-three, Kaitlyn still lived much of her life as if she were still within those locker-lined halls. Growing up in America with a white family who didn’t know much about her cultural background, she had always felt different from the other Asian kids. And she could never let go of the fact that she didn’t look like the white kids. Dreading the lunchroom where the tables always seemed to divide by ethnicity, Kaitlyn would just join whoever invited her to sit down first. And since she was well liked by all with her bubbly personality (to hide her underlying insecurities), that usually didn’t take long.

On her way out the door of her chic studio apartment, Kaitlyn stopped to make sure that she had placed the right number of turkey slices on her sandwich when her smartphone buzzed with a reminder: “First therapy appointment today!” Grabbing a notebook, she thought, Hopefully, I will finally get some answers. Kaitlyn had decided to talk with a therapist at the local center that treated obsessive-compulsive disorder. Following work that day at the marketing firm where she was a lead consultant, she headed to the appointment both excited and anxious to see what therapy was all about.

“I can’t stop thinking about food,” she told the therapist. “After seeing a website a few years ago that lists exact serving sizes for every food imaginable, the numbers just won’t leave my head.” Quickly realizing that Kaitlyn’s obsessions centered around food and weight, the therapist referred her to outpatient eating disorder treatment with Dr. Thomas. But I don’t have a problem with eating, Kaitlyn thought.

She was right. From one perspective, she didn’t technically have a problem with eating. Kaitlyn ate enough calories every day to sustain a healthy body. Although thin, she was never too thin. But her body was a point of confusion for her and always had been. Although her white friends had always complimented her figure, she never felt quite thin enough to be Asian. Kaitlyn wasn’t sure what size she was supposed to be, but she did know one thing: she would never gain weight. She still prided herself for being able to fit into her high school prom dress.

Even though Kaitlyn ate enough and rarely missed a meal, her attitude with food was so rigid that it was disrupting her life. When she dined with clients at regular work dinners, she often panicked upon the food’s arrival: How many servings is this? Should I put half in a to-go box now or later? Normally, Kaitlyn was good at putting her clients at ease, but they became noticeably uncomfortable around the dinner table. And Kaitlyn’s dating life was nonexistent. Because she had to eat at restaurants so much for work, she just couldn’t bear the thought of dining out yet again during the week. She hated that guys always asked her out to share a meal. Why does everything seem to revolve around food? Constant thoughts of calories and planning the perfect meals absorbed most of her time.

In therapy with Dr. Thomas, Kaitlyn kept saying, “But I eat.” She didn’t understand why she was in an eating disorder clinic. Dr. Thomas helped her to realize that although her caloric intake was adequate, she needed to work on her disordered attitude toward food. She needed to add flexibility, not calories. This, in part, landed Kaitlyn in the category of unspecified feeding and eating disorders. Breaking food rules would be a big part of Kaitlyn’s recovery. In the beginning, Kaitlyn couldn’t imagine eating, for instance, even just one grape over the recommended serving size. If she took a banana out of the fruit bowl at work, she always tried to take the smallest one. Eating a tiny amount over what she was “supposed to” created such feelings of intense shame and guilt that she sometimes would refer to these instances as a binge. And these “binges” inevitably led to body loathing. It was as if she could pinpoint exactly on her body where each “extra” morsel of food was appearing.

To help improve Kaitlyn’s attitude with food, Dr. Thomas recommended many strategies. Kaitlyn began connecting more with trusted friends at mealtimes. Watching how and what they ate—an external cue—she realized that no one eats “perfectly.” She also experimented with trying new recipes and saw firsthand that exact measurements didn’t matter that much. (You’ll read later how Kaitlyn stood up to a bunch of grapes.) Slowly, she began to trust her body more, understanding that it could make up for small differences in amounts eaten. Unlike what Kaitlyn originally expected from therapy, Dr. Thomas also encouraged her to broaden her sense of self-worth. At first, she didn’t even know what that meant and had no idea where to start. But then, at Dr. Thomas’s suggestion, she began volunteering at a local children’s hospital. The kids’ genuine excitement about seeing her each week helped to melt some feelings of not being good enough, as did changing up her dating routine. She joined an online dating site and challenged herself to go out on at least one date every few weeks. One of her favorite dates was going to the ice-cream parlor with Kevin where they shared a magnificent sundae—calories and serving size unknown.

Kaitlyn got better over a period of six months. Through the process, she learned how almost anorexia had been, in part, a way for her to cope with always feeling “different.” So healing meant that she finally started to feel good enough—just as she was. The amount of food she ate stayed about the same. Her weight remained steady. What changed was her attitude toward it all.

Moving from relying on external cues to internal cues is the next step in achieving normal eating. Research suggests that the three core features of intuitive eating include (1) eating for physical (rather than emotional) reasons, (2) relying on internal hunger and satiety cues, and (3) giving yourself unconditional permission to eat.13 Put more simply, according to Tribole and Resch, “Intuitive eaters march to their inner hunger signals, and eat whatever they choose without experiencing guilt or an ethical dilemma.”14 When Kaitlyn first started therapy, she was the opposite of an intuitive eater. She ate to give herself a sense of control—not because she was hungry. In fact, she was terrified to even admit when she felt hungry, craved a food that was not on her “OK list,” or wanted even one morsel more than the serving size indicated on the package label. Through treatment, she discovered that food is just food, connected with her hunger and satiety cues, and came to recognize all of her damaging food rules—and broke them. In time, you can too.

Have you ever noticed the labels and names that we give to certain foods? Light, low-calorie vanilla sponge cake is called “angel food,” whereas buttery, rich chocolate cake is referred to as “devil’s food.” The names alone imply that food has a moral value: good versus bad. But if you choose high-calorie devil’s food cake over the angelic variety, you are not bad. Food doesn’t have a moral value. It is just food. Of course, it’s hard to remember this in real life. In one study, women—both with and without eating disorders—felt guiltier and fatter after merely being asked to imagine eating a high-calorie food.15

Think about a recent time you dined out with others. While looking at the menu, you might have heard someone say something like, “I’ve been good all day. Now, I’m going to be bad.” And this person isn’t talking about dining and dashing but rather ordering the decadent cheesecake. Although stealing the cheesecake might be considered morally wrong, simply eating it isn’t. Begin to notice this kind of dialogue within your own mind and those around you. If your loved one is struggling with almost anorexia, do your best to minimize negative food talk, which enforces the allure of anorexia. Most people want to be “good,” and Ed says that you are good if you restrict calories. In fact, with anorexia, you reach the highest point of goodness according to the senseless morality of food rules.

Do you categorize foods into good and bad? If so, you might have noticed that the bad list has grown longer and longer over time, possibly leaving only a few good items that you can eat with impunity. But all food has its place in normal eating. Even though a bowl of berries might be packed with more nutrients than a chocolate-chip cookie, that doesn’t mean that cookies are bad and that you should never eat them.

Your body needs different foods at various times. Ed Tyson, a physician who specializes in eating disorders, told us that he explains it to patients this way: “Imagine a scenario where you are driving down a road in Darfur, Africa. You come up on someone who is starving and you have two choices to feed them something: (1) a Greek salad with some feta cheese, julienned vegetables, and dressing, or (2) a Big Mac with double meat, double cheese, fries, and a shake. Which choice has the most of what this starving person needs, i.e., which is the healthier choice for this person? The one with the most calories, protein, and fat is what would give a starving person more of what they need—the Big Mac choice. So, what is ‘healthy’ is really relative and is dependent on the needs of the individual at that time.”16 We aren’t saying that everyone’s road to recovery must include a McDonald’s drive-through, but if you are currently underweight, increasing the energy density of your diet is critical to healing.

All of this “listen to your body” stuff may sound like a bunch of mumbo-jumbo. But you may have noticed by now that Dr. Thomas is pretty obsessed with science. There is actually very good research to suggest that intuitive eating interventions (that is, those designed to enhance appetite awareness and encourage eating in response to physical hunger cues) are effective in reducing eating disorder symptoms.17 To put intuitive eating into practice, check out the phase 2 column of table 6. Important to note: you might see yourself on both sides of the table—in phase 1 and phase 2—on any given day. That’s okay. What matters is that your general progression is to the right—toward internal cues.

This table can be downloaded at www.almostanorexic.com.

Intuitive drinking is also important. No, we are not talking about cocktails, but rather actual fluid consumption. Although there is controversy surrounding how much water you really need (the often-cited eight glasses a day is not scientifically based), most health care professionals agree that you should drink to your thirst. Unfortunately, many people with almost anorexia and other officially recognized eating disorders do not. In one study, 25 percent reported drinking too little (to punish themselves or feel in control), whereas 63 percent were drinking too much (in an attempt to suppress appetite or facilitate purging).18 With regard to alcohol and other drugs, women with either an eating or substance use disorder are four times more likely to develop the other disorder compared to women with neither problem.)19 Misuse of alcohol and other drugs might reduce your distress in the moment, but in the long run it will only make you feel worse and will likely exacerbate your disordered eating. If you think substance abuse might be a problem for you and you can’t control your drinking or drug use on your own, we recommend getting help.

Right now, disordered eating might be the norm for you or your loved one. Without question, people with almost anorexia are signing up to feel quite abnormal when they first try to eat normally. In this way, feeling weird, bad, or just completely unbalanced is actually a step in the right direction.

People who struggle with disordered eating adhere to certain “food rules” that give them a false sense of security and control. Dividing items into good and bad categories is just one type of food rule, but many others exist. For example, I absolutely cannot eat between meals. Dessert is allowed only once per week. These rules, of course, don’t truly provide safety, because they inevitably lead to being out of control with food and feeling miserable. When Dr. Thomas talks with patients about their own individual food rules in group therapy, these patients’ rules feel normal to them. While someone might say that Ed never allows her to eat ice cream, another might share that Ed forces him to binge on gallons of ice cream. One woman might say that Ana lets her eat whatever she wants in the morning but requires intense restriction during the rest of the day, and a man sitting next to her might have an Ed who enforces the opposite rule. If all of these food rules were followed, you would not be allowed to eat anything at all or, on the flip side, you would have to eat everything all of the time. Some rules really are meant to be broken.

Most people don’t like being told what to do, yet many let Ed boss them around. Chapter 4 included an exercise asking you to identify your dietary rules. You may have noticed that you are avoiding certain foods, eating only at specific times, or restricting the overall amount that you eat—all because Ed promises you that following these rules will keep you thin, safe, binge-free, or something else. In this exercise, we’d like you to get curious about whether these rules are truly serving you.

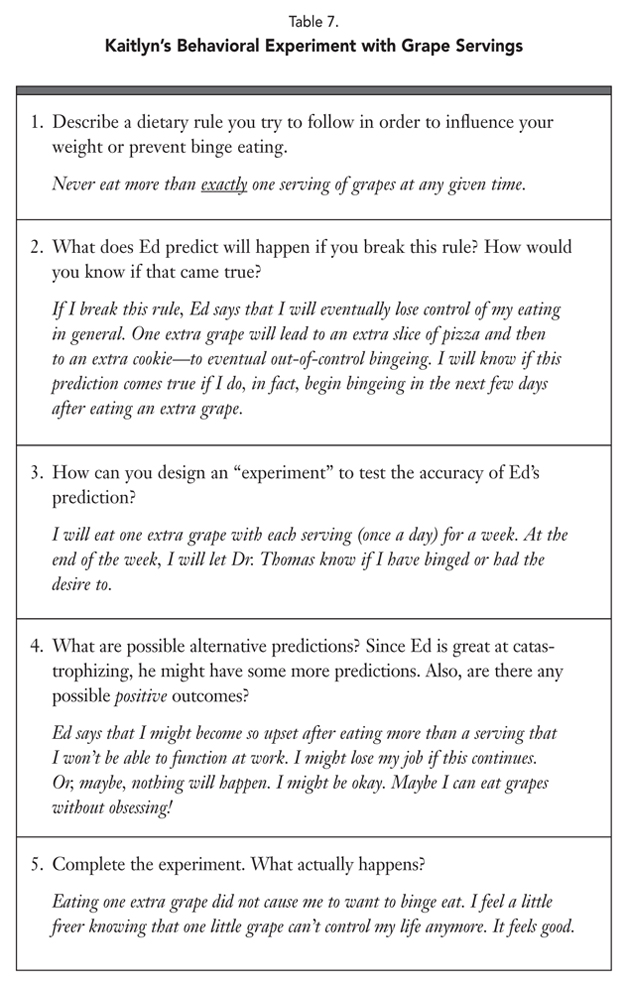

Specifically, we invite you to design an experiment. Behavioral experiments are a helpful strategy in the treatment of eating disorders, including almost anorexia.20 Before diving in, take a look at Kaitlyn’s example in table 7. Also, consider talking about this exercise with someone you trust, like a therapist, dietitian, or supportive friend or family member. Following the steps listed in table 8, we encourage you to identify one of your dietary rules and think about what Ed has told you will happen if you break that rule. (Use table 8 or a notebook. You can also download this exercise at www.almostanorexic.com.) Because Ed does not always speak in scientific hypotheses (he’s not that clever), it may help to ask yourself, Why am I so afraid to break this rule? Ed may have told you, for example, “Eating chocolate will make you fat” or “If you eat a normal-size dinner, your feelings of fullness will be so unbearable that you will not possibly be able to cope.”

This table can be downloaded at www.almostanorexic.com.

Once you have identified Ed’s prediction, try to design a simple experiment to test it. Be scientific. If you eat a bar of chocolate, for example, how will you know whether you have “gotten fat”? Simply feeling fatter doesn’t count, since these feelings are more strongly correlated with mood than with BMI. Could you try on the same pair of jeans that morning and again the next day? Could you weigh yourself? This is the only time we would actually encourage you to body check. We told you, Dr. Thomas will do anything for science. However, even Dr. Thomas agrees: if weighing yourself will feel unsupportive to your recovery right now, design an experiment that doesn’t require any numbers—like Kaitlyn did in table 7. Once you have designed your experiment, consider possible alternative predictions. For example, maybe you will feel fatter (but not weigh more) after eating the chocolate. Maybe nothing at all will happen. Although it’s possible that Ed has been telling you the truth all along (maybe you are a very special person who really will gain ten pounds from eating just one square of chocolate), chances are he’s way off the mark. The only way you’ll know for sure is to carry out the experiment. That’s how Kaitlyn finally overcame her obsession with weighing and measuring food. In a similar way, this exercise helped Emma realize that she could tolerate the anxiety of eating odd (rather than even) numbers of foods. And remember Camille who was trapped in her macrobiotic diet? She learned from this very exercise that eating “regular” food would not, in fact, make her sick.

Keep challenging yourself. If you create an experiment and receive surprising pro-recovery results that you don’t quite believe, do it again. Repeat until you do believe. In Dr. Thomas’s research, she’s always doing experiments over and over—making sure she got it right the first time. On the other hand, if you design an experiment and your results seem to indicate that Ed has been right all along, think again. Maybe, for instance, you do happen to gain a few pounds one week when you allowed yourself to eat dessert. This doesn’t definitively mean that a couple of chocolate-chip cookies led to weight gain. Consider any other variables that might have affected the results: For example, did you change anything else about your eating during the same time period? Are you feeling bloated due to constipation, menstruation, or water retention? And maybe you could take the test even further. How will gaining a couple of pounds truly affect you? Maybe Ed predicts that your life will be over if you gain a few pounds. Ask yourself: Is my life really over? In one way or another, your experiment will teach you an important lesson.

Many individuals recovering from disordered eating believe that books, clinicians, and others are just trying to make them fat. Dr. Thomas’s patients are sometimes pretty suspicious when they first start working with her. But we seriously have no interest in making you fat. This isn’t Hansel and Gretel—where a wicked witch lures children into her candy-decorated house to fatten them up in preparation for eating them. Rather, our goal is to help you function better, mentally as well as physically. And that’s a lot more than Ed can say.

You may be wondering how you can eat several times per day—and even enjoy cupcakes—while maintaining a healthy body weight. Here’s how: on average, the more you weigh, the more calories your body burns—even while you rest. Researchers can predict your resting metabolic rate with a fairly straightforward equation (such as the Harris-Benedict). Studies suggest, however, that individuals with anorexia burn fewer calories per day (about 200 to 380 fewer, to be exact) than such equations would predict.21 In other words, while people are starved, their metabolism is artificially suppressed. Healthy people of similar body mass are burning about a cupcake’s worth more calories per day simply by not undereating. Fortunately, as people with anorexia are refed, their resting metabolic rate returns to the level of healthy individuals.22 Dr. Thomas calls this phenomenon the “cupcake catch-up.”

If you are currently underweight, you’ll need to gain enough weight to reach a healthy level in order to experience this metabolic boost. When it comes down to it, your final body weight will be determined greatly by your genes. We could all eat the exact same amount and exercise in the same way for an entire year and we would all look different. If you are wondering what will happen to your weight when you start eating normally, consider your previous adult weights (if you had previously healthy ones). Research suggests that individuals who are weight suppressed (that is, their current weight is much lower than their highest adult weight) tend to gain slightly more weight during anorexia and bulimia treatment compared to eating disorder patients who are not weight suppressed, but the difference is usually pretty small.23

So you’ll need to prepare for some suspense. It’s completely normal for your weight to fluctuate in early recovery. When Jenni first stopped using compensatory behaviors to “make up for” binges, she gained more weight than she had anticipated. (She was still bingeing a lot.) It took about a year more in recovery for her weight to stabilize. Until then, she believed her treatment team had succeeded in making her fat, which Ed thought was their entire goal! One of Dr. Thomas’s patients used to call her crying every time she gained a pound. Now this woman’s weight is stable and she takes minor fluctuations in stride.

You can read this book one hundred times—even memorize it word for word—but if you are not eating, it doesn’t matter. Neither does therapy and all of the other best intentions. Food is the best medicine when it comes to recovering from almost anorexia. Without a doubt, you absolutely cannot get better without it. You must find balance with food, a difficult but very possible task. There is no way to make tackling the food easy. As we said before, you must just jump right into the hard part. You will have lapses along the way, but they won’t last forever. Despite how long destructive behaviors and attitudes have been entrenched in your life, you can develop a healthy relationship with food.

People often think that they are completely unique, the only person in the world who cannot get better. But we have known many people who thought this, including Kaitlyn and Jenni, who got fully better. You can too. Eventually, normal eating will become your default position, your natural place. And this is possible not only with food but also in other areas of your life, including exercise.