BUDDHIST ART

Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties

In this period, China witnessed the most frequent dynastic changes in its history. The long period of political turmoil and civil war ended with the integration of the north and south, including different ethnicities. Han Chinese culture began to spread to the south and there was an influx of Western culture to China, too. Buddhism, which was introduced in the Eastern and Western Han dynasties, also flourished during this time and became an important part of Chinese ideological field. Buddhist arts also prospered, with Buddhist cave art as an example. Cave temples were built for meditation as a way of repelling worldly desires. The construction, murals and sculptures inside the caves are visual demonstration of such artistry. In China, Dunhuang, Yungang, Longmen and Kizil Caves form the most important pantheon of Buddhist arts.

A Caisson Ceiling Painted with Flying Apsaras (Feitian Zaojing)

Zaojing is a frequently used art form in the decorations of Dunhuang Caves. Zaojing borrows the techniques of ceiling decorations in traditional Chinese architecture, i.e. decorative patterns painted on the concave surfaces of round, square and polygon. Traditional wooden structures are susceptible to fire and therefore water plants such as lotus flowers are the motifs for painting. Initially zaojing of Mogao Grottoes took lotus flowers as a predominant theme. Gradually other patterns started to emerge, such as flying apsaras, dragon and phoenix and canopy, and they were applied in many places. Among these, flying apsaras are most representative of Dunhuang’s artistic images. They are goddesses who dance, sing, and scatter blossoms to serve Siddhartha Gautama. These apsaras are always floating images in the air of beautiful women who sing and dance.

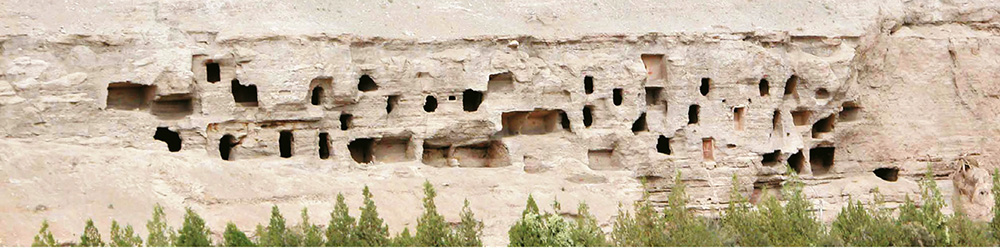

Exterior of Dunhuang Caves

Timeless Dunhuang

Around 366, a monk named Le Zun started to carve the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes, which marked the beginning of the popular art form of caves sculpture. Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes are located on the cliff of Mingsha Mountain (Singing Sand Mountain), northeast of Dunhuang City, Gansu Province. Its cave art is a mix of architecture, sculpture and painting, forming a timeless treasure house of art.

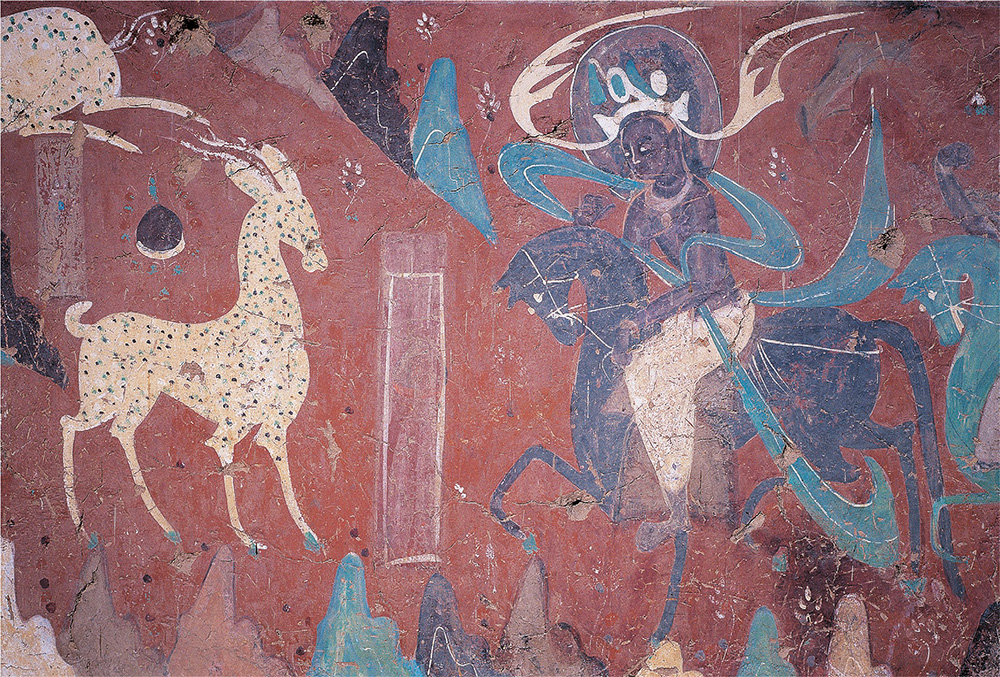

Jataka of the Nine-Colored Deer

(section)

Dunhuang murals, which refer to the paintings on every surface of the corridors, the four walls and the ceilings, are an important part of Dunhuang’s cave art. The murals that have existed to this day cover an area of about 50,000 square meters in all. These paintings include portraits of Buddha, Bodhisattva and Buddhist followers, stories about Buddhism (including stories about Buddha’s life, the Jataka tales, stories about hetupratyaya and transformation), mythology and depictions of secular lives at that time. Some of the elongated pictures, shaped like a scroll, depict vividly and exquisitely stories about Buddhism. The Jataka of the nine-colored deer is among the early masterpieces of Dunhuang caves.

Giant Buddha

Statues of Buddha, usually tall and empowering, are a contrast to the humbleness of mortal beings. Buddhist followers and benefactors across the country try at all cost to build colossal statues of Buddha to express their humility and piety. The statues are scattered all across China, such as Leshan Buddha at Sichuan Province and Lushena Buddha at Longmen. Finely executed Buddha statutes are also found in Dunhuang. For example, Cave 96 houses a stone-bodied clay-stuccoed sculpture of Maitreya, which is thirty-five meters tall; Cave 148 is home to a colossal lying Buddha. The Buddha above is from Cave 158, the Buddha in Nirvana, which is fifteen meters long and lying on a bed over a meter above the ground. The Buddha, eyes half closed, appears serene, content and smiling. The features on his face, the bun on his head and the creases in his clothes are all softly and beautifully executed.

A Painted Bodhisattva Statue

This painted clay statue is a Bodhisattva created in the peak of the Tang Dynasty. Located in Cave 45, it is an exquisitely executed statue: she gracefully stands there, her head tipping slightly to the side, her body the shape of an S, her eyes half-closed, her lips wearing a smile—an elegant figure with a benevolent and charming countenance. Totally different from an Indian Bodhisattva, the features that have turned feminine clearly give statues like this its Chinese characteristics. Painted statues in High Tang testified to the highest artistic achievements among those in the Mogao Grottoes. These statues of female Bodhisattva, plump and beautifully dressed, were apparently meant to satisfy the secular aesthetic taste of the Tang people.

Longmen Grottoes

Longmen Grottoes, whose construction first started around 494, took about 400 years to complete. Of which, Fengxian Temple, started in the Tang Dynasty, houses the biggest group of nine statues, including a Buddha, two disciples, two Bodhisattvas, two heavenly kings, and two warriors. Among them the main statue—Virocana Buddha is 17.14 meters tall and has a 4 meters tall head and 1.9 meters long ears, with its trunk round and plum, an imposing and powerful presence.

The Big Vairocana of Longmen Grottoes

Yungang Grottoes

The carvings in Yungang Grottoes, located in Datong, Shanxi Province, were first started in 460. Most of the caves in Yungang Grottoes were completed around 494. They display an unprecedented fusion of styles of Buddhist statuary reflecting the secularization and localization of Buddhist art in China. Take Caves 9 and 10 for example: the entrances of both caves have octagonal columns that are carved with numerous Buddhas; inside the caves, the niches for Buddhist statues, whose tops and lintels reflect the style of Han-Dynasty architecture, are considered to have combined the structure of Central and Western Asian architecture and traditional Han-styled architecture.

Yungang Grottoes

Kizil Caves

Probably first carved at the end of the third century in Xinjiang, China, Kizil Caves are also known as Caves of a Thousand Buddhas. It was one of the first Buddhist cave complexes located at the farthest west of China’s territory. As a large cave-cluster, it is a demonstration of the tremendous achievements of Kucha, one of the significant states in the western part of the ancient China, with achievements in religion, culture, art and customs over a period of 500 years from the end of the third century to the end of the eighth century.

The Mural in Cave 175 of Kizil Caves