At the Dajarra cattle yards breaking in Kabul.

All men dream, but not equally.

T.E. Lawrence, 1922

I lay just below the crest of a ridge and scanned across the Djiboutian border into Ethiopia. Dark sharp rocks pressed into my hips as I watched tall, lean men with coarse white cloth around their waists and daggers slid into wide leather belts. Tilting back my beret I leaned further into the rubber eyepiece of the telescopic sight. The rubber formed a seal and when I moved a little I felt the soft suction pulling at my eye. I was bound to the weapon and it seemed to be an extension of myself; my brain, my eye, the telescopic sight and the round that it carried in the chamber.

Emaciated men moved between camel thorn trees leading camels with ribs that threatened to spring from their hides. One man had wiry black hair and obsidian black eyes rimmed with red that spoke of too many days in the bright hard light and windblown sand. When he grimaced, which he did every few paces on his plastic sandals, he exposed a wide gap in perfect white front teeth. The men carried AK-47s across their shoulders; the camels carried weapons on their backs. They were bringing rifles into Djibouti to supply rebels, those ethnic Afars who felt themselves disenfranchised by the leadership of the Djiboutian President.

I marvelled at the life led by these men and their camels, moving across a country pitiless to the weak and ill-prepared. It was a place where people died too early, from tripping a mine, the lack of a few drops of water or even from a bullet like mine. I wondered at the toughness of these men in a land that was hard, indifferent and intolerant to weakness. It was watching them that inspired me to another adventure and I wondered what it would be like to Walk Across Australia with camels of my own.

I watched the men move off through the waves of heat and between the camel thorn trees then radioed back to camp. Later, I pulled out my notebook and drew a map of Australia. I wrote down Byron Bay, Australia’s most easterly point. I labelled my map with the Great Dividing Range, the Simpson Desert, Uluru, the Gibson Desert and Steep Point, the Australian mainland‘s most westerly point. Then I penned a dotted line across the heart of the country, all the way to the west coast. I closed the notebook and put it in my pocket where I imagined it glowed warm with promise.

The idea for a Walk Across Australia at its widest points came to me in 1990. I was a French Foreign Legionnaire on the Ethiopian border. It was a place where life could depend on the whim of a stranger and the tensing of muscle on a trigger. It was in the face of such uncertainty that I wanted to create something positive; the dream of an adventure that would sustain and motivate me through my remaining years in the Legion. I thought that to conceive, design and then execute a plan would be to give a life to a dream of my own. It would be a contrast to so many of the things I experienced in the Legion. As far as I knew it would be something that no other person had ever done. So, on a rocky hilltop looking into Ethiopia, the idea for the adventure was born. I would catch and train some camels; trained camels and I would Walk Across Australia.

I left the French Foreign Legion in May 1993, took a couple of weeks to walk across England, and arrived back in Australia a few weeks later to commence a graduate program at university. Between the essays and exams I began the long planning process necessary to bring the expedition alive.

I went to my study and the diaries I kept while I was in the Foreign Legion. They sat quietly neglected at the end of some shelves, at home it seemed to me, between a biography of Sir Robert Falcon Scott and a study of British travel writing, Mark Cocker’s Loneliness and Time.

I picked them from their resting place and put them on my desk. I sat down and for a moment considered the small pile. There were five volumes, schoolroom exercise books bound with wire or stapled, with blue or orange covers. They were scuffed, with evidence of scraping, smudging and dirt. As I held them in my hands I felt their grit in the lines of my hand.

Opening one volume, a scrap of paper fell from between the pages to the floor. It looked like it had been torn from a notebook. Picking it from the floor I knew at once what it was. It came from a different time in my life. It was a hand-drawn map of Australia with a dotted line across its centre. Though it was described in faded ink, I could make out the names of places I knew: Byron Bay, Simpson Desert, Uluru and Steep Point.

I had been on one journey. The French Foreign Legion was a journey, from enthusiasm to scepticism. I sometimes wondered why I felt I had to challenge myself again, on another difficult journey. Can a journey complete the self? Or was it a journey to meet the needs of the self or an acknowledgment of a need to move? Perhaps this you would never know. What you could know for certain was that until you undertake and commit to move, you will never know the cost or the prizes. Until you do, you will likely be angry with yourself, perhaps frustrated with your life and you will doubt the choices you make. As for me, I made my choices, committed to them and tried, with everything I had, to achieve them. It was as if I was reaching for challenge and passion, the feelings and the way they moved me. I wanted to taste the bitter and the sweet. When I thought about it, what I really wanted was part pilgrimage, part penance. Reaching for that seemed to be important enough in itself.

It was early days yet and I was brutally honest with myself. I could read a map, was fit and could fire a rifle. I knew next to nothing about camels – except how to shoot them and the men who led them. I read everything I thought was relevant, from T.E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Richard Burton’s A Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Mecca and Al-Madina, Wilfred Thesiger’s Arabian Sands, the Australian explorers including Giles, Warburton, Stuart and Sturt, to more recent travellers and works of fiction, including Patrick White’s Voss.

Other than comments on the practical issues including water storage, food and camel care, there was one essential feature all these explorers and travellers shared. They shared a need to expose themselves to the potential for failure and death, to the certainty of pain and loneliness for the possible rewards of recognition and fame. All their energies were devoted to doing what they believed had to be done – never minding the cost in money, in relationships or health. They were fixated and obsessed.

I knew how they felt because like them, I was fixated and obsessed. It did not matter that many people I knew thought that I was wasting my time. ‘Mate, no one else has ever done it before. You know why – it’s because it’s hard. What makes you think you can do it?’ Or, ‘Think of your career, you’re not getting any younger you know,’ went the chorus. ‘Haven’t you had enough adventure with the Foreign Legion?’ Others were less generous though more direct and to the point, ‘Mate, you are mad. Ever thought of getting some professional help?’ I knew that I did not want to be an old man with a career who regretted not having done things in his life that he was passionate about. I knew I would never have enough ‘adventure’ – whatever that word meant. I knew I was not mad – just different. Anyway, just because I did things differently did not mean I was mad. In fact, I thought I was probably not much different from many men I knew, except I was prepared to do what I said. Planning continued because to give up would mean giving up part of me, and that was something I could not do.

That part of me that I could not ignore needed to be tested. It needed to be tired, cold, hungry, thirsty and frightened. It was not just a need for adrenaline; the Foreign Legion gave me plenty of that. It was a need to see other parts of me. If what other people thought of me did not matter, knowledge of my own self-certainly did. It meant that to be happy I had to know myself, and the only way I could do that was to be exposed to fear and hope and the possibility of losing everything. I wanted to see other parts of me that a comfortable life could never expose. I felt the need to strip away the noise and colour that made up so much of everyday life and find the noise and colour inside myself.

Other than the satisfaction of doing something I felt driven to do, there was nothing of value in the trip. It would not bring me money – after all, if I had been driven by money alone I would have joined the corporate world – nor was it likely to bring me fame. Few people seemed to be interested in adventure, camels or deserts. Even knowing this the greatest prize of all awaited; that of self satisfaction in achieving something no one had done before.

I reasoned that some of the only other people who thought this way were the early European explorers of Australia. I read their journals and tried to put myself in their shoes. Perhaps for a short while I could be like them, casting off the everyday to look for something new, something worthwhile and something of value. Even so, I was conscious I would be retracing and crossing the routes and stories of many people before me.

The land had been crossed by many Europeans and I read many of their stories. I recognised too that Aboriginal people had moved across the country for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. While few of their stories of the land had been written down, I wanted to meet Aboriginal Australians generous enough to share them with me. I knew that I was starting from a low point on the camel, and more generally, on the expedition learning curve. But this was how I wanted it to be. I knew I could learn. I would go to the experts for their help but it was me driving the trip, me deciding how it was to be done. If this was an Everest of my own choosing, I was not going to pay a Sherpa to lug me up a mountain. I had to learn about camels, who caught them, who trained them and who had good camel saddles. I had to learn about sponsorship and how to raise money for such a trip. There was a lot to read, many people to talk to, and a great deal to learn.

There was also one very important person to convince. I met Amber on the lawns of the Australian National University Law School in early 1994, a few months after I had returned from the Foreign Legion. It was late summer, the air was golden with wattle dust, and the irrigated grass just outside the main entrance was plump and green. Like me she was studying for admission to practice as a lawyer. We became lovers and eventually moved in together. From the start we loved each other though we feared what the other was thinking.

I explained that the need for me to do this trip and my loving her were just two parts of the same person. They were not contradictory – though Amber seemed to think they were. In that quiet time, after lovemaking and before sleep, I would look into the dark of her eyes and wonder if she would ask me to choose between her and what I was driven to do. These were things that we both put off discussing further and so remained unresolved.

In the years leading to the start of the expedition there were practical things I decided early. I approached a number of charities to ask if they would like my help. Some never responded. In the end I chose the Fred Hollows Foundation, and they chose me, because of their connection with the Australian Outback, the desert, and the help it gives to Aboriginal people with cataract blindness. I set up a web site to promote the trip and the Foundation.

An early decision was to take female camels. According to many written accounts they were far easier to deal with than bulls or bullocks and so were preferred as members of camel trains. The impact of this decision would not become apparent until I was almost half way across Australia – and it nearly cost me my life.

I decided too that the camels would not be nose-pegged. Nose-pegging involves a small piece of plastic or wood inserted through a camel nostril and round which a line is tied. Given the sensitivity of the camel nose, it is a popular method of steering and maintaining control, used by camel handlers across India, the Middle East and Africa. But it seemed to me that if the rest of the world’s camel handlers could get away without using a nose peg, so could I. In a practical sense, this decision meant I would have to work doubly hard to win my camels’ trust.

I realised that I could not catch camels and train them without help. Nor could I build appropriate camel saddles for the sort of gear I thought I would need. I was a public servant lawyer, not a saddler or a welder. In Africa I had shot camels that had been carrying rifles. I had been a camel killer, not a camel man. All this meant that I had to find people willing and able to help with the practical side of camel handling. It meant too that I had to keep working to be able to pay those who helped.

Then there were the camels. Though there were reportedly hundreds of thousands of camels in desert Australia, it was hard to find people who actually caught them and trained them for use. And when I did find people who caught and trained them, unless I joined a camel safari operation it seemed unlikely that I would ever be able to learn. At least that was until I heard Paddy McHugh.

Driving home from the office one afternoon I heard the radio announcer introduce a camel man planning to export camel milk to Thailand. The camel man had a deep gravel voice, was evidently articulate, engaging and most importantly seemed to know a thing or two about camels. I called a couple of camel owner contacts who gave mixed reviews about Paddy, the sum total of which was to keep a careful eye on him. It was advice I’d heard about many others and if I’d learned anything in my short time in the very small camel world it was that there were only two or three men who had the unreserved respect of the rest. Newcomers were just that and though I had no personal experience of it, I’d heard some were decidedly opportunistic.

I badgered the phone company and they gave me Paddy’s telephone number. Then I called him. The conversation was the same I had with every other self-styled camel man. I gave Paddy an outline of what I needed to do and what I wanted. There were long silences and I sensed a tension in him, between telling me I was completely out of my depth and foolish, and wanting to make money. Before making up his mind he questioned my outdoors background and paused to reflect again.

Finally, he told me he was going out camel catching and could catch some extra camels for me. The camels he caught for me could be trained at the same time as his new ones, thus solving the training question. As to my camel handling training, he was leading a two week trip along the eastern edge of the Simpson Desert and me and my newly trained camels were welcome to join him. In all, of course he could help – for a price – and once that was agreed my planning began in earnest. Despite what someone had said, I was very glad I had been listening to the radio that afternoon.

I first saw my camels at Dajarra, 110 kilometres south of Mount Isa in western Queensland. Dajarra was once the westernmost railhead in Queensland, where cattle from the Northern Territory were moved in mobs to be held in the large steel cattle yards before being loaded on rail trucks for the run east to the market. There was a local legend that the Dajarra railhead moved more cattle than were moved through Texas in the United States. It was probably a very old legend, and spoke of better days, far removed from its population of some 170 people, mainly on welfare.

In winter 1996, Paddy hired a helicopter, mobile yards and a number of men in vehicles to round up a camel herd to the west of the town. Selecting the animals he wanted, including some likely camels for me, they were trucked into yards on the edge of town. A day or so later Paddy, with most of his team, left town for home on Queensland’s east coast.

While I missed Paddy and the camel roundup, I got to town just as Jim Green, Paddy’s bearded, curly-headed, shorts and flannelette-wearing British offsider, began to work the recently arrived camels through the yards. I met 20-something Jim at the Dajarra Hotel sitting in the front bar. While the overhead fans stirred the air, he flirted with the barmaid, the policeman’s wife, and hid behind a mop of curly black hair and a belly laugh that later that afternoon even made camels pause in the chew of their cud.

The camels were wild and wild eyed. At up to 1000 kilograms of humped four-legged muscle they squirted skinny cylinders of green shit and at every opportunity kicked, gaped and spat their cud. I loved them instantly. I loved their sweet smell of greasy wool, their grace and their arrogance in an environment of which they knew nothing. Over the next few weeks Jim and I worked the camels through the yards, touched them, spoke to them and fed them. During that period too I named the camels I thought I wanted: Kashgar, Chloe and Kabul.

Kabul was a male and I wondered if he would be suited to the trip I was planning. After all, my reading told me that male camels were little short of trouble. I knew that male camels became aggressive and violent around shecamels in the rutting season. They would charge and challenge other males, sometimes killing competitors and certainly trampling anything in their way. Unfortunately for me the rutting season was during autumn and winter, a large slice of the eight months I planned to be walking across the continent.

Nevertheless, I thought he was different from all the other camels. Kabul was aloof, independent and seemingly untroubled by the newness around him. I wanted him on my team. I wanted to make him my friend and my lead camel. In the end, I was right.

Paddy arrived back at Dajarra a week or so before the trek along the eastern edge of the Simpson Desert. He was less than 170 centimetres, slim with wild, shoulder length sun-bleached hair, the whites of his eyes bloodshot from too long blinking in the sun and the dust. Though he was busy in the coordination of the forthcoming trip, he patiently showed me how to tie a camel down and put on a headstall so a lead rope could be attached. He introduced me to different saddles and instructed me on how to put a saddle on a camel’s back.

With a group of camels and paying customers like me we walked and rode from Dajarra to the south-west, through Glenormiston cattle station, and finally to the township of Bedourie. My camels were tense and often lifted their noses to scents from the desert. I thought the scents included other camels and freedom, so at night I tied them off to trees with climbing rope four or five metres in length. It meant they could feed at night and in the dark I left the comfort of my swag, patted and talked to them in a low voice, and double and triple-checked the bowline knots.

The trip to the Simpson Desert’s edge woke in me a passion for the desert with its giant blue dome of sky and dunes of rippled red sand. It also taught me that though I knew a little about camels there was a lot, one hell of a lot, left to learn. At the end of the trip Paddy promised to freight the camels to me in Canberra while I undertook the search for saddle-makers and sponsors.

In 1997 the camels arrived in Canberra and were agisted on a property on the northern edge of the suburban fringe. People driving to work listening to the news on their radios could watch the fluid movements of camel necks as their bodies glided across the paddocks in search of grazing. Kabul, Chloe and Kashgar adapted quickly to the change of environment, and in an old utility that was all I could afford I drove to the camels every dawn and dusk, trying to balance the demands of my job as a government lawyer with the needs of the camels. I checked their water, patted, stroked and brushed camel coats, and fed them lucerne hay and a mix of pollard and molasses. All through the winter and into the spring of 1997 I planned the route. I rolled out maps, checked stock routes, chased up sponsors who seemed vaguely interested (and many who were not) and tried to reassure myself that the little money I had would be enough to carry me through the next year.

The gear began to arrive. I had maps covering my route across Australia. I designed a swag and had it made with heavy-duty rip-stop canvas. The camel saddles I measured up, running tapes around camel bellies like a couturier, and sent the numbers off to a saddler in Alice Springs. I wrote out inventories of the equipment I needed, including food, camel medical kit, ropes and an array of spares. I made up my mind we would leave early next year.

In that Christmas of 1997 I must have been a very difficult person to be around and certainly to live with. After four years the plan was coming together and its different parts, from National Park permits to rifle licences, were like delicate threads woven carefully into the plan to give it form. I had to be very careful not to snap or forget one of those threads. It made me obsessive about details, obsessive about the expedition.

On my final day at work my boss took me into his office and with a wave of his hand directed I sit in a chair opposite his desk. He sat down, the desk between us. In the low, patient, measured tones of a middle ranking public servant concerned about his career, he said that I needed to rethink my future in the law and the future of my job. In the silence punctuated by the arrival of an email, I was less than pleased. Though he had known of my plans for two years, he had waited till then, the day of my departure from the office, to tell me. For a moment it was just something else to worry about. He was a good lawyer but looking into the dull opaqueness of his eyes I knew he and I had little in common; even less so now. I would not be making money for eight months and knew that I would have to find a job on my return. I looked at him with what I thought was grave concern and told him I would indeed be thinking very seriously about my future. I stood up to shake his hand. He turned his back and, speaking to a bookshelf, reminded me to hand in my identity pass. Through three doors, an elevator descent and the wave of a security guard, I walked outside into the sunshine.

As far as I was concerned, there were more important and pressing matters. There was a castration to be done. I was sure that my decision to keep Kabul had been the right one, but all the camel hormones coursing around his body made him difficult and perhaps even unreliable, particularly in winter, the rutting season. I declined to do the slicing myself so I sought the local vet. Though Ken was a horse rather than camel expert, we were on first-name terms and I thought my payments had funded at least one of his children through an exclusive school.

On Ken’s arrival at the paddock I tied Kabul down. This was done by having him drop into the camel recumbent position, front legs folded parallel to his chest and hind legs under his belly. The lead rope of 10 millimetre climbing rope knotted at his headstall was tied round his right forward leg and then taken over the base of his neck to the left forward leg. Without breaking the climbing rope there was no way he could get up on his front legs. I tied down his hind legs as well, to make sure he could not move at all during the proceedings.

Before the sharp-blade work, Ken wanted to ensure Kabul would feel very little. To that end, Ken asked me how much Kabul weighed. I said at least 800 kilograms and in response Ken put together a cocktail of drugs. The injection went into Kabul’s neck and in a few minutes his eyelids grew heavy and spittle began to drip from a lower lip that sagged away from his teeth. Even so, when Ken moved to Kabul’s rear, Kabul remained very interested, his head turning to keep Ken in view.

I knelt in front of Kabul and scratched in the coarse black curls behind his ears. I told him I loved him and that this little procedure was for the best – though this last was clearly more for me than him. Meanwhile Ken set out his tool kit and was soon brandishing a shiny blade. With a ‘Hang on, that’s it … Good boy,’ and a, ‘Jesus they’re big,’ the job was done. Kabul barely moved and there were tears in my eyes.

I untied his hind legs and then the ropes at the front so that he could stand and move. The idea was that as long as he continued to move the site would drain and heal quickly and cleanly. I got Kabul to his feet and, as he swayed groggily away, Ken assured me everything had gone well and I should not expect any complications. As we stood watching Kabul lumber away two waiting crows saw their chance. Sharp beaks speared bloody eggs, wings flapped and in their turn the crows lurched, swayed and lumbered away.

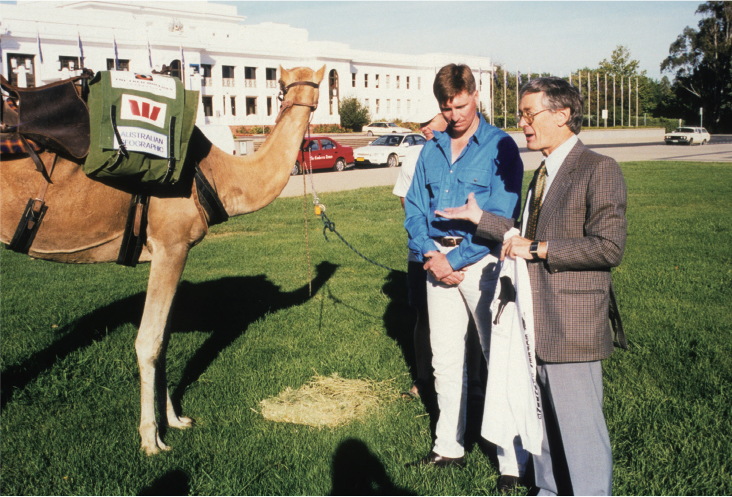

In the hope of securing more sponsorship, I approached Dick Smith to be the Patron of the Expedition. He generously agreed and in February 1998 the trip was launched on the lawns of Old Parliament House in Canberra. I spoke with representatives of the Aboriginal Embassy on the site who graciously agreed to the launch and attendant media. They were very supportive when they heard the expedition was to raise money for the Fred Hollows Foundation. To make the launch a real attraction I brought Kashgar to the lawns in a horse float. Unloaded, her pads on the manicured green grass, she behaved like a princess. After Dick Smith had given a short speech, she let me walk her around the fountains for the media to take photographs of the two of us.

The local paper carried a picture of us on page three while the rest of the media stayed away. I had done all I could. A few days later camels, gear and I headed north.

With Dick Smith, patron, and Kashgar in front of Old Parliament House in Canberra.