2 The Journey Begins

– 23 March 1998

A tolerable high point of land bore NWBW distant 3 miles. This point I named Cape Byron … It may be known by a remarkable sharp peaked Mountain lying NWBW from it.

Captain James Cook, 15 May 1770

Early on Monday 23 March 1998 I lay in bed, watching a mote kissing Amber’s cheek. Her mouth was open, lips moist with the touch of her tongue. Maybe, as she dreamed, she searched the air for her hopes and sureness in her future with me. The mote looked permanent, but was it like our love, a fiction illuminated by the golden glows of a sunrise? My eyes were grainy; stare-eyed apprehension had meant the moisture evaporated from my eyes.

The day before I lay in the Pacific Ocean, knees to my chest, suspended in the wet warmth, the foam washing and fizzing over my body. I thought back on the years of planning, the setbacks and disappointment that had to be fought and overcome. I had hit a cow and written off a vehicle. I had worked as a lawyer in sterile comfort watching the seasons turn, dreaming of the green, blue, red and gold of Australia’s outdoors. I even wondered whether I was wasting my time, but not often and never for long

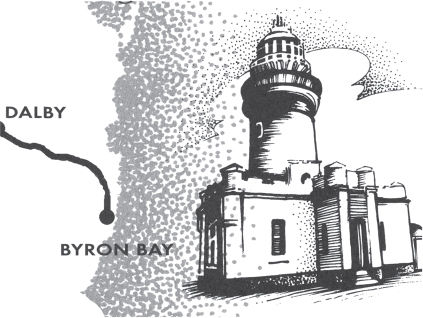

Later in the morning I drove with Amber to the Cape Byron lighthouse, the 18 metre high, round-topped chess piece opened in 1901 that reportedly had the brightest light in Australia. It was time to go and with a gulp of the sea salt air I began. Lifting my head I closed my eyes for a moment and tried to picture myself at the end of the expedition at Steep Point thousands of kilometres away. Doing the sums in my head again I knew I had to walk around 30 kilometres every day until mid November, when I planned to finish. One part of me said I was mad, possessed of an arrogant hubris that denied the possibility of hurt, injury or accident. How else could it be done? After all it was the equivalent of walking more than a half marathon every day for eight months. For every day I missed I would have to make up with more kilometres the next day, or the next. Another part of me marvelled at the possibility that it could be done no matter my fear, no matter what the numbers said. It was this part of me that won and drove me forward.

I missed a turn on the way out of Byron Bay. I prefer to think I was distracted by the people rather than a lack of navigation skills. Along with the beach, Byron Bay’s biggest asset is its people. I had never seen so many people wearing so little but tattoos and rings on and in various parts of their flesh. I walked on past the Returned Services Club before I realised I was off the track, then spun on my heel and retraced my steps.

Later than morning I wrote up my diary, which I kept to capture and keep my thoughts, fears and frustrations. I sat down to eat a meat pie at Uncle Tom’s Special Pie Shop, a food and petrol stop on the turnoff to Mullumbimby, the home of Australia’s counterculture in the 1970s and 80s. During the next few days I carried nothing for lunch, preferring to fill up on hotel breakfasts and just carry water in my little pack. According to the sign above the shop, approximately 550,000 pies would be baked at Uncle Tom’s in the course of the year. I ate two of them and as I sat chewing through the pastry I looked up to the opposite side of the road and a large traffic sign of towns and distances.

That sign reminded me there was a long way to go. It also made me think of kilometres as time. From now on time was on a different, a bigger, scale … certainly not of meetings or emails. There was no need to think of minutes or hours, but days and months. This was because time equalled distance and the only measure of success was distance. I suddenly felt very different from the people who rushed past me in their cars, perhaps late for some engagement. If they looked at me at all they probably wondered what the hell some fool was doing walking on the side of the road in a humid 36 degrees.

I was also different from the two young guys I woke up that morning on Cape Byron. They had spent the night 90 metres above the sea, and expected to wake with the sun. Instead it was me who woke them with ‘Hey guys, are you okay?’ Grey faces and red cobwebbed eyes peered from coloured sleeping-bag cocoons. They asked me if I had the ‘vibe’ and I asked them what they meant. One shook his head and the other said ‘Oh, wow man.’

I supposed they were looking for something. They were some of the many in Byron Bay who expressed their search in tattoos, piercings and the language of self-actualisation. I was looking for something too; in my own way, actively seeking, doing and testing. So I left them to pack up their sleeping-bags and moved over to the sign that declared ‘Australia’s most easterly point’. I looked to the east and the diamond points of the sea, picked up a loose rock and threw it, as far as I could, to where the sun rose out of the Pacific Ocean.

I took a breath for a moment then turned to the sign. Just as I moved to put my foot up on the sign I stood squarely on some droppings left by one of the many goats on the cape. I looked at my foot and then at Amber, who was preparing to photograph the beginning of the great endeavour. Her smirk was accompanied by the bleat of a goat. Having taken the photo Amber promised to meet me later and drove away.

From Tom’s Pies I headed to Amber and Brunswick Heads, my stop for the night. Just short of town I walked through Pilgrim’s Park. It had a barbeque, mown lawns and headstones, some vertical, others flat on the ground. It seemed to me that here were people, or at least their memories, and our paths crossed. On one tombstone was written a too brief story:

In loving memory of Minnie Beloved daughter of James and Mary Anne Mills Died 30th April 1886 Aged 3 years and 11 months ‘Of such is the Kingdom of Heaven’

I wondered what brought James and Mary Anne there. Was he a cedar cutter and did he work in the hinterland, or did he work at the port? Were they searching for a better life for Minnie? Was this a land they loved, or did they fear it? I was certainly looking for something; something in me, something in the land of which I was a part. Once I had begun the walk, and had time to think, I was starting realise that what had originally been something necessary to sustain me was now much more. I grasped the freedom I had to search for a part of myself in the land that was my home.

That night Amber and I stayed at the incongruously named Chalet Motel, not far from the beach. At the art deco Brunswick Hotel we had our final dinner together, outside on bricks laid like cobblestones. Though there were few people eating under the stars, we sat close like conspirators, whispered to one another and held hands so long they became hot and damp. I reminded Amber that we would be apart for eight months. She leaned forward so that her hair fell across her face. She held my hands in hers. With wet diamonds in her eyes she promised me she would help me no matter what happened or how long I took. I was more thankful and grateful than I could say, even more so because her statement was so unexpected. I was tired from the long day and felt very vulnerable and exposed. It was what I sought and the implications were close to me now. The expedition was on and the sense of vulnerability, exposure and fear of failure hung heavy on me, weighing down my usual optimism.

At the Chalet Motel I attended to practical matters, including my feet. I had a quick shower and later, as Amber watched, I punctured a blister. Five years in the Foreign Legion taught me a few very useful things. It taught me that the sometimes favoured method of puncturing the blister and then cutting off the troublesome piece of skin was just about the worst thing to do. Instead, I used a needle heated with the flame of a lighter, punctured the offending spot and put a plaster over it. This at least kept the skin and took the pressure and pain away. The fact was that running five or even 10 kilometres every day did not replicate walking 20, 30 or 40 kilometres a day. I hoped my feet would toughen up fast and I knew that before they did I would suffer the pain of the road. Following the minor surgery we fell into bed. We held each other closely, wondering what the future would bring. Then we slept and the darkness swept our doubts away.

Next morning I walked from the motel out onto the road. Amber stood next to the car, her face shiny and bright in the early morning sunshine. She had her work in a law firm and had to be back the following day. With what I thought was a brave wave, I walked away along the road to the north, my head down and tears now rolling down my cheeks. I did not feel guilty at leaving her; just a selfish sense of loss and sadness at leaving her warm smile and her warm embrace.

A car went by. It was Amber. She pulled off the road some 50 metres in front of me. Stepping from the car she waited till I caught up. ‘I’m not going to cry any more. I want you to know that I love you and I want you to finish this. I want you to come home to me.’ She swallowed a sob and put her arms around my neck. I could feel her warm tears on my wet cheek and then she let go. Was there ever a right way to say goodbye?

Without wiping her wet eyelids or the tears that coursed down her cheeks, she kissed me on the mouth, got into the car and drove off. I stood still with my little green day pack on my back. Through the back window of the car I saw her draw the back of her hand across her eyes. I felt at once utterly foolish, selfish and alone. My little green pack had never been heavier. The idea of walking across Australia had, suddenly, never seemed so self-indulgent or full of risk.

I steeled myself, took a deep breath and lifted my face to the sound of early morning birds and the sunrise over the ocean to the east. I walked toward the coast through Brunswick Heads past the fishing cooperative, and then turned right into Ocean Shores, a suburban estate with watered lawns, neat flowerbeds, fences, kerbed roads and shopping centre. The curtained windows winked at me as I walked by, the occupants probably nervous at a person purposefully striding through their piece of bliss with a little pack on his back. I marched across the Orana Bridge, a wooden footbridge, which brought me to the beach, the muscles in my legs at last stretching out after the work of the previous day. Apart from a few rocky headlands, my map told me the beach extended past the Gold Coast to the north.

I turned left and headed north along the golden ribbon of sand. When I looked behind me the Cape Byron lighthouse seemed suspended above the blue promontory in the distance. Appearing now and again over the dunes was Mount Warning, and at my right shoulder blue green mercury licked at the golden sand. I felt moisture trickle down my neck to my back where it was stopped by the pressure of the pack against my skin. The moisture spread as the air was too dense to allow for evaporation and there was no breeze to provide a cool caress to my cheek.

Over the next few hours there were times when I could see an Impressionist smudge of people, in front or behind me, but too far away to make out clearly, to wave at, or to shout to. For most of the morning my only companion was a sea eagle, patrolling her stretch of beach with bright, shining, dark glass eyes. I felt sure she was keeping a benevolent eye on me. I loved her ability to move on the dense air and the thought that we were sharing the same place, that ambivalent place, on the sand between the land, sea and the sky.

I watched her for a while and reached into my little pack for my diary, ‘We share more than you know. Your passing is marked by a little turbulence in the air, mine by the movement of a few grains of sand, soon smoothed into sameness by the action of the sea. If someone were to follow you or me, they would never know we were here.’ For those who leave no marks on the land the only evidence of their passing are stories. I felt no need to create something substantial, to build a tangible legacy. Instead, I wanted to show myself and others that stories really mattered. They mattered because stories are who we really are.

An hour or so later I met a far away smudge that hardened into Bill. He was fishing from the beach in baggy blue shorts with a rod longer than a station wagon. His feet were buried in the wet sand of the shore break and a cigarette lolled between his lips. As the muscles of his calves bulged he told me about the fish. ‘There are mullet out there, mate, but the bloody commercial fishermen take too much. Greedy bastards they are. They take roe for the overseas market and dump most of the fish back into the ocean. Bloody criminal it is. Whaddya reckon?’ I said that it did not seem to make much sense to me.

At Hastings Point further north, surfers knifed a right-hand break, and I made it to the Kingscliff Hotel as the sun began to paint orange and red the border between land and sky. I arrived with a screaming headache of dehydration, right eye blurry with the throb. From the front balcony of the hotel I could see Surfers Paradise, the high-rise buildings like a row of broken teeth, curving away into a rotten smile to the north-east. Windows facing west were honey-gold in the late afternoon, though I doubt if anyone noticed – everyone looked out to sea.

At the bar of the hotel I ordered a jug of iced lemonade and wore hot narrow eyes on my back from the bronzed blue-signeted patrons of the public bar. They probably thought drinking lemonade in a public bar was the violation of an unwritten law. With a pleasure born of need I ignored the men around me and heard nothing but the hum of the overhead fan and the tinkle of ice against glass as I poured the sweet, cool liquid into my body.

As my thirst was slaked I considered the following day. It was another 35 kilometres to Surfers Paradise, a repeat of the walk from Brunswick Heads. Already in pain, my hands beaded with sweat thinking about how hard this would be. When I sat at a barstool for a few minutes the blood pooled in my feet. To straighten my legs was to allow gravity to have its way and more blood rushed toward the ground. I imagined my feet exploding, the bottom of my legs just bloody stumps. Having underestimated the training necessary for this trip, I rapidly concluded that to continue walking I had to get my feet up for as long as possible at the end of each day.

Rather than walk along the beach I chose the road, to rest my sinews and tendons stretched by the giving sand. Just out of Kingscliff I moved inland from the beach and the concrete began. After an hour or so I rested for a few minutes in a bus shelter on the Gold Coast Highway. My skin was greasy and sticky and grit stuck to my face, the sand blown from the beach and the dirt of so many exhaust pipes. The bus shelter was opposite PK’s Chooks, where you could get ‘the best chicken in Australia’, and I watched the cars and buses go by with their colours and coughed dirt. Blue Nurse, Greyhound Pioneer buses, Regent Taxi, Positive Pest Control, Australian Air Express and Multi Constructions all hurrying, hurrying to the Gold Coast and Surfers Paradise. Alone, on the opposite footpath, was an old lady with purple-grey hair, grey handbag and white polka dot shift. She shuffled into the Palm Beach Mobile and Tourist Park while the world rushed by and paid her no attention at all.

My goal and finish for the day was the Marriott Hotel, and for a moment as I sat its bar I thought it was Paradise. From a hot, slogging day, I sat down to the gentle hum of an air-conditioner, the clink of ice-filled glasses and the tender attentions of Natasha the barmaid. All that day the high rise of the Gold Coast hotels were easy enough to make out at the end of the curve of the beach to the north while concrete radiated heat and the Pacific Ocean blinked the sun just a few metres away to my right.

Around 10 the next morning I glimpsed the sea for the last time and headed north-west to follow the Beenleigh Highway. The rest of that day was spent battling all forms of motorised road transport and construction equipment. This highway was a four-lane, dual carriageway slash across the landscape. It was no place for camels or pedestrians. There was stinking road kill every few hundred metres, glued to the road like ripped and scuffed squares of carpet.

I passed well-attended amusement parks that catered to some people who had so few thrills, so little time and so little imagination that they paid for them. From the side of the road and above the noise of traffic I heard screams and laughter bought with the dollars of people who traded living a life for the security of sameness. It seemed to me that many people paid good money for stimulation to displace the fear and quiet knowledge of an emptiness inside themselves. In knowing a little about myself I knew what I had to do. No matter what others thought, this was my adventure; I researched it, risked things for it and lived it. I owned it. The people in these amusement parks were like people I met who brought memorabilia – to experience and try to own in a small way some of the excitement of risk and of something special and unique. Many did this rather than risking or achieving for themselves. Sadly, some did it because they never had the chance, and never would, to do something themselves.

The grey-green scrub that flanked the highway choked off any hint of a sea breeze so there was just the dirty breath of passing vehicles against my skin. I was happy to finish the day at the Yatala Pie Shop more than 40 kilometres from the morning’s start.

The pie shop opened early next day and with a pie inside me I walked across the road bridge into Beenleigh and eventually west onto Browns Plains Road. As the sun began to make its way above the trees I passed two women, perhaps in their forties, in a park. I stopped and witnessed a curious sight. They were standing a few paces apart wearing pink chiffon dresses with fairy wings. They raised their arms to reveal paintbrushes. I watched for a moment as they studied each other very carefully and painted each other with a caress that appeared both tender and loving. I could have expected this in Byron Bay, where assisting others to self-knowledge and expression was an industry.

Around midday I stopped to drink the last of the water I carried. I sat down opposite the gates to the Greenbank Military Training Area range control. The red flag was up indicating that live ammunition was being used somewhere within the 4500 hectare facility, but sitting outside range control I heard nothing more than the occasional backfire of a vehicle.

Later, at the end of a hot, humid day in Brisbane’s west, I called my brother Brett. The laces on my boots were tight from the swelling of my feet and each step on the grease-stained concrete outside a petrol service station was a burning brand against my soles. I was in trouble and not up to much more walking. I needed to recover so spent the next two nights with Brett in Brisbane, wishing my feet would shrink so that I could fit them back into my boots. I spent most of the time with my feet up, a fan cooling my skin and a glass with plenty of ice in my hand.

Brett dropped me off on Sunday morning at the point where he had picked me up two days before. We stood for a moment looking at each other. After Law School, Brett went to Cambridge to do a postgraduate degree. I joined the French Foreign Legion. While I planned my trip across Australia, Brett worked to secure preselection for the Senate. Rather formally we shook hands in a patch of long grass beside a road littered with broken bottles and dog shit. He screwed up his eyes and indoor skin stretched tight across his face; the stress and paleness from spending long days on the telephone doing deals. I wondered what the year would bring for us both.

As I walked a few prohibited kilometres along the Logan Expressway and west into Ipswich I reflected again on choices and why some people chose to do difficult things when a far easier life lay very close to hand. As I strolled past sharp-sided schools, dark green treed parks and shaded verandah pubs, it became clear to me that for some people at least, their choices were made, or made for them, when they were very young. I stopped to ask directions of two skinny young men. Their naked white knees were thrown over the arms of shredded cane chairs which sat among the weeds in front of their house. The rip in the fine wire mesh front door was a frozen grimace. Their faces were sickly green and greasy in the sun. The blue shirted one said, ‘Get fucked. Waddjya want in our town?’ I looked at them for a moment, said nothing, and then walked on just as a cloud passed overhead.

From the start of that day my right ankle gave me trouble. As the day progressed it got worse. With every pace it felt like a length of hot wire was being drawn around the outside of my ankle. I felt my foot swell in my boot and the day ended with me shambling along beside the road. In an ecstasy of shuffling I saw myself as an old man, a small pack on my back, a set of lungs wheezing and a pain in my foot that filled my mind with redness and stars.

The mental effort of blocking out the pain became as tiring as walking. By the end of the day I was exhausted. I made it to Walloon, named by settlers who brought the name with them from Prussia, passing on its outskirts an enthusiastic evangelical congregation celebrating their joy in the warm and moist Sunday evening air. Through the window of the church I could see people with sure, knife-edged creased pants, shirts, hair and beliefs.

Walloon was eight kilometres short of Rosewood which had been my aim that evening. I asked the barmaid at the hotel if there was any accommodation. ‘No – sorry love, don’t do accommodation.’ I had a glass of lemonade and thought through my situation. I could not walk further that day and so I decided to hitch-hike to Rosewood.

I hobbled to the first floor of the Sunshine Hotel in Rosewood to find the only other occupant of the public rooms. He was an Irishman, perhaps in his sixties, on his way to watch TV in baggy pyjamas, silver chest and fragrance of hops. In a soft burr to match his eyes he said, ‘Son, I’ve never known it to be as hot as this in March. It was 37 Celsius today.’ The Sunshine was what Queensland hotels used to be. I could easily imagine a team of shearers or canecutters sleeping four to a high-ceilinged room, the overhead fan cutting through the heat of the evening blessing those below with a shiver.

In keeping with the trip being one walk across the country, next morning I hitch-hiked back to Walloon. Greg was in his twenties, in a bright red bubble car, matching bright red short-sleeve shirt, very dark sunglasses and platinumblonde hair. As soon as I was sitting in his car we got talking. He told me that he was a sponsored skateboarding professional looking to compete in Sydney the following weekend. He was an expert in ‘verts’ – going up and down a wall up to 14 feet high. He had broken his wrist, his leg twice, and driven his upper arm through his elbow. He showed me the scar.

From Walloon I walked back to Rosewood and its video shop with posters of two action hero brand names – Stallone and Van Damme. Had I arrived a day earlier I could have ridden on a steam train. A banner suspended across the main street told me that on the last Sunday of every month train rides could be taken from town – from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. The destination was not clear, but it could have been fun, and it cannot have been far. I did know for certain that it would be a burning and humid 24 kilometres to Laidley. The way out of town was flanked by the dark green of the long grass by the road’s edge and sub-tropical green of the fields.

Later that day I sat at the bar of the Grandchester Hotel in Grandchester, a town that was just a small dot on my map. Down the bar a little way a bald local in shorts and with a tattooed, very sun-browned upper arm told me that the very first train in Queensland ran between here and Ipswich in 1865. It made me smile that the town’s name was changed from Bigge’s Camp; apparently the railway’s terminus deserved something grander. In the valley, on the left into town, was a corrugated-iron roofed steam-driven saw mill. According to Fred, who sat along from the tattooed arm, it was one of the few remaining steam-driven mills in Queensland. As I watched his fist around the frosted glass I wondered if he had lost his fingers at the mill.

I was going to ask the publican if she would like to step outside to have a photograph with me but she had a black eye and I did not want her to have to say no or have to explain how she got it. Her husband sidled up to her with an air of possessive and distracted menace. I did not feel very comfortable and I do not think she did either so I let my eyes go to the small model train that ran around the back of the bar, just below roof level. On just one loop it ran around and around the back of the bar. It must have been very hypnotic for the regular patrons. It certainly was for me.

On the wall of the pub, next to the entrance, was a noticeboard with yellowed reminders of tennis matches and tractors for sale. There was a note that read:

Peacocks for 2 cartons

Mum, Dad and kids Ph: 43598

With cool lemonade in hand I mused over the cryptic note and figured it meant that in exchange for two cartons of beer one could have a family of peacocks.

I arrived at the outskirts of Laidley, what the locals call the ‘country garden of Queensland’, as the sun began to throw a long shadow behind me. I noticed stationary cars, one behind the other, with large water containers on trailers or in the trays of utilities. Nearby was a sign indicating it was a council water filling station. It seemed that the green of crops all around was deceptive. Lush crops were thanks to water from deep underground. There was no water in the creeks or in the rivers. It was drought and it was affecting many people. I met Frank and Gwen, a couple in their fifties who had been ‘married longer than we can remember’ and who finished each other’s sentences as they leaned against their front gate watching the proceedings. According to them, there was often insufficient water in their house tanks for people who were not connected to the town water supply. So they fell into line and filled up at the water station. At least they did not have to pay. Watching the water stream from the hoses I knew that someone would eventually have to pay the price of convenience, thoughtlessness and greed.

After the filling station I stopped at the Queensland National Hotel in Laidley. I arrived sticky and relieved I was merely footsore and still able to walk. I lay on the bed and its threadbare pink cover and must have dozed off for a few minutes because the room had become darker as the sun set on the day. Along with a couple of beers, I had a T-bone steak so big it hung over the sides of the plate and its juices dripped bloody to the bar. As I chewed the beef I listened in to talk of rain, or the lack of it, and of stock and feed prices.

After a breakfast of eggs and as many cups of tea I could drink, the road next day took me west to a picture postcard town. In Forest Hill two old pubs faced off under wide verandahs and at the end of the street stood a war memorial, where a white stone soldier rested on arms reversed, eyes bent to the sunrise. Every town I walked through in my crossing had one; a memorial to its lost men of World War I. Often, on another face of a column or the reverse of a plinth, the names of those who had served or lost their lives in World War II or later conflicts were also remembered. Thanks to directions from a council worker in a fluorescent orange waistcoat, I took a short cut and followed a track parallel to the railway lines into Gatton.

The tarmac on the road to Gatton was sticky from the sun and sucked at my boots. In town I bought myself a litre of mango juice and a meat pie. I lunched on a bench beside the road watching the traffic speed by. Then, with a belly full of juice I headed to Grantham and a walk up the escarpment toward Toowoomba and the west. I arrived at the Helidon Motel Spa just an hour or so before sunset.

Once in my room, I took off humid and smudged clothes and walked the few metres to the soothing waters of the Helidon Spa, known even in Aboriginal times as having healing powers. The spa was roofed and enclosed by clear glass panels. I was alone, and in the still quiet floated on my back, the only sounds the pulsing in my ears, the lick of water against my body and the gentle click as cartilage, bone and muscle disengaged in my lower back. I hoped the spa worked its wonders on me; my body ached and I knew the next day would be no easier.

A big voiced journalist from the local paper took my photograph and interviewed me the following morning. She had a firm view about the drought and use of the water in the Lockyer Valley. ‘It’s just no longer sustainable. They’re rooting the land,’ she lectured. The water was being pumped out of the natural chambers underground and on to crops of the valley at a rate far exceeding projected future rainfall. It meant, in her view, that our grandchildren, if we had any, would be left without the resources necessary to manage the land as we did today. ‘It’s bloody criminal,’ she said, which made as much sense as anything I had heard over the last few days.

I left the Helidon Motel and its spa and turned left onto the Warrego Highway. Just a few kilometres away to the west the country buckled up to the Great Dividing Range. The range is the geographical, spiritual and economic divide that marks the separation of the coastal dwellers from the people of Australia’s hinterland. On the right-hand side of the road I came across a plaque commemorating Allan Cunningham, the earliest European explorer through this part of Queensland. It read:

Cunningham and his party passed this way on 27 June 1829. During this portion of his journey he climbed Mount Davidson (Sugarloaf) and discovered Mount Tabletop. The spa water region was also discovered by him at this time.

(Gatton and District Historical Society)

Cunningham was recognised as the first European explorer through much of the country to the west and south-west of the penal settlement of Moreton Bay, later renamed Brisbane. It was Cunningham who named the Darling Downs further to the west, a mere 50 kilometres away. I reminded myself I was crossing the paths of many people, some of whom were remembered, though most I understood very well were not.

From the small plaque beside the road I began the steep walk to the top of the escarpment. On the walk to the top it rained fat warm drops. I looked down to the right where the ground fell away to dense rainforest and the air I breathed was thick and heavy with moisture. Once I crested the ridge, however, the environment changed and the subtle soft light of the coast became the brittle hard light of the inland.

I walked through Toowoomba, a town of warm blooms and smiling people, and then down to the western plains. In just one day’s walking I had moved from the moist green of the coastal plain to the dry brown of Australia’s interior. I stood on the western outskirts of Toowoomba and looked down on wide open plain and another country. The distance was shortened in the haze of late afternoon – filmy gauze to obscure and perhaps soften the future. There was no more green, no lush fecundity.

Instead, there was this other land, a place generally little understood by those who lived on the coast who peopled it with clicheś; of drought, of burned land, shrivelled ideas and flies. To some people, those who owned shares in the great agricultural enterprises of the country, a drought was a loss of profit, perhaps a tax deductible loss. For others, flood and drought were a death in life, something that touched the heart and made people fear for the present and their future.

Late in the day, I stopped at the truck stop at Charlton for something to eat. The truck stop lay at the bottom of the range on the Warrego Highway, named after the river at the end of the highway almost due west. It was a brown place that smelled of greasy eggs, oil and people moving on.

Next morning I continued west to Oakey, the home of Bernborough, ‘The best race horse,’ according to the plaque at the foot of the statue next to the Shire Council Headquarters, ‘ever produced in Queensland.’ Further along, on the footpath in the middle of town and under a wide verandah, I walked past a lady in her sixties. She sat behind a card table and a handwritten sign, under a large wide-brimmed hat with a plastic flower in its crown, selling raffle tickets in support of the local Scouts. She was engaged in a very animated conversation with a woman wearing a long flowing floral skirt, sensible flat black shoes and a lavender scent to match the colour of her hair. Her eyes were bright and hard and the floral skirt said, ‘and you wouldn’t believe it. She walked in as bold as brass and she said …’ I didn’t linger to listen.

Oakey is also home to the Australian Army Helicopter School, and the Black Wasps followed me west. I could not imagine there would be too many navigational problems for the pilots; there was only one road and one railway track and they paralleled my direction – unerringly and always west.

By mid-afternoon I was becoming dehydrated and my breath made a rasping noise. Soon after, I arrived at Jondaryan. The small town was the home of the largest operating woolshed in the Southern Hemisphere and marked my earliest arrival at a night stop. The pub’s front door was just a few metres off the highway and its interior was cool, dark and welcoming. The only sounds were the hum of a fat fly batting itself against the ceiling and the low drone of the television. All I wanted was to sit down and rest with a cold glass. The barmaid ignored me, far more interested in what was happening on a flickering screen than someone wanting a drink at her bar.

She sat at the other end of the bar and refused to turn to me. I said ‘Hello,’ and her back said enough. It took a commercial break before I was able to order a tall glass of cold lemonade. Even showing me to a room was a real task for her though I waited until her program was over to ask if one was available. Maybe I upset her daily routine of not doing much at all but sitting and watching television.

As the sun came up next morning, I walked between golden fields and began to think more of what lay ahead. The first part of this trip had taken 10 days and I wondered about the camels. Even though Gibbo and Mary-Anne assured me over the phone they were fine, I wondered if they had forgotten me. I wondered too if I would be able to walk with them; whether or not they would follow.

At midday I had lunch at York Stud, a mixed property of cattle and wheat on the south side of the road to Dalby. Joe was a plumber who purchased the property when he retired ‘from wages’, as he put it, 15 years before. He filled me with eggs and stories of his native Austria. He told me that Austria was good and Australia better. ‘Austria is a closed place. No space. In Australia there is space all around us and room in our heads to think. Here,’ he went on tapping his head with his right forefinger, ‘a man can do what he wishes. What better thing is it for a man to be able to choose whatever he wants to do with his life? There is nothing better.’ He told me that he loved the land, the woody-nut smell of the black soil and space to watch a sun rise above a horizon. Joe stood at the gate and saw me off with a smile and an Austrian accented ‘Good on ya mate.’

The road to Dalby was flat, the black top merging into the dark scalp of rich soil, the hallmark of the Darling Downs. The country was gold with the stalks of recently harvested wheat, and the sky a dark china blue with a few cumulus clouds like so many lost sheep wandering to the horizon. As so often before, I arrived in town just before sunset. My breath came in short gasps, my lips were caked in dried spittle and my feet had swollen to stretch the lacing of my boots. I lay on the bed in the motel and wondered if every day had to be like this. It was all I could do to order some takeaway Chinese food.

On my way out of town to Aronui in the morning I passed the Dalby Bowls Club. It was competition day. I could hear warm voices congratulating, ‘Oh well done!’ and, ‘Good shot!’ There was also the crack of colliding bowls, ripples of applause and the occasional cheer. A portly fellow in a too figure-hugging and not altogether flattering competition outfit of bright whites and broadbrimmed hat called out to me. It was Bob Collins, a self-confessed ‘bowls fool’ who welcomed me to Dalby. ‘Glad you could make it mate. You remember me – from Burleigh Heads Bowls Club?’ I did. It was a place where I had slowed for a moment to watch other people, and I had watched him play an end. He had asked me what my T-shirt logo ‘Alone Across Australia’ meant and I explained it to him. I was delighted to see him again and somehow it felt that he had measured the distance I had already come. He wished me luck before he went off to play another shot. I headed off to Aronui and the camels.