Corones Hotel, Charleville.

Have you strung your soul to silence? Then for God’s sake go and do it; Hear the challenge, learn the lesson, pay the cost.

Robert Service

A week later we were on the Adavale road about 18 kilometres out of Charleville. There was a marker flanked by three kurrajong trees just off the right-hand side of the track that said:

Captain Sir Ross Smith and Lieutenant Sir Keith Smith landed on this plain on the first England to Australia flight on 23rd December 1919.

Erected by the Murweh Shire Council.

When I looked across the plain I thought it must have been nerve-racking for the two aviators. Even though the plain seemed pretty flat and the grass would have dried off in the summer and made any large obstacles visible, there were still plenty of ant nests up to a foot or so high that could have ripped the undercarriage from the fuselage. These must have been almost invisible from the air.

Charleville was good to me. I had the camels checked by the vet. The local police and officers of the water resources department advised me on the route. I had gear repaired and improved by Eric Burgess the saddler. I even had time to attend the Charleville Show Ball at the invitation of Alan MacDonald who brought me a beer in the main bar of the remarkable Corones Hotel.

This hotel was built over five years and completed in 1929 by Harry Corones, a man with vision. Reportedly costing £50,000, an enormous sum at the time, it had on its ground floor a reading room with copper-topped tables, deep leather lounges and a ballroom. Upstairs, the accommodation included private rooms with ensuite bathrooms. All the rooms had the advantage of opening on to the wide first-floor verandah, which in the height of summer must have been a blessing.

Harry and the hotel played host to Amy Johnson, the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester and Gracie Fields. On entering the main entrance you can imagine women with hair piled on their heads, jewels at their throats, swaying in silk; their men in dinner suits, collars starched and their foreheads glistening.

I spoke on the Charleville School of Distance Education, formerly known as the School of the Air, to tell the schoolchildren, and thus their parents, of the reasons for my trip and the route we would be taking. The school had been operating out of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory from 1951, on the back of recognition that each remote sheep or cattle station in Australia had an HF radio for communication with the Royal Flying Doctor Service network – another Outback institution. In Charleville the School of the Air came into operation in 1966. By 1970 it consisted of four teachers and ran lessons 11 hours a day for more than 200 children.

Sure Charleville was good to me but there was more to it than that. I liked the town, its open spaces and wide shaded verandahs. I learned that the first European in the area was Edmund Kennedy in 1847, that the town was gazetted in 1868 and drawn up with very wide streets to enable bullock teams of up to 14 pairs to turn pulling their wagons. Cobb & Co., the legendary Australian stage coach company that once ran services west from Brisbane, established a coach-building service in the town in 1886. This was very bad timing as the railway arrived two years later and drove the demise of the coach; and of the bullock teams for that matter.

While in town I also picked up parcels, one of which contained a sleeping bag. At last I no longer had to tolerate wet blankets for my bed. Instead they formed a mattress to ease the pain of my back, beginning to ache more and more from the pounding of my footfall on the track.

There had been talk of more rain and no sooner had we walked out of Charleville, along the track to Adavale, than down it came. It was a molten mist, a wet blur covering everything. It rained like this for a few minutes, so that everything was drenched – camels, gear and me.

Later, after the marker to the aviators, I set up an army hootchie, a plastic sheet, and was ready to settle in for the night by 5.45 p.m. With winter drawing closer the days were becoming shorter. And then it rained again. With my swag set out, at least I had a place that was relatively dry. As I lay in my swag I reflected on a meeting earlier in the day – with the Adavale policeman.

He stepped out of his Toyota air-conditioning and onto the dusty track in creased blue shorts. His shining black shoes soon grew a patina of red dust, and as we spoke the dust worked its way up the socks that hugged his calves to his bare knees. He told me he didn’t like metropolitan work, so he volunteered to come out here. He said he and his wife loved the country and the people. They loved the wide open spaces and the sense of freedom that seeing the horizon gave them. Geoff invited me to stay with him in Adavale on my way through to Windorah.

Lying in the swag, hands behind my head, the rain drumming on the sheet above me, I was feeling angry, a knot of frustration tightening in my belly. Maybe this was because no matter how hard I tried to make everything perfect for the camels, no matter how I tied the loads, no matter what I did with the sheepskin blankets and rugs, there was always some rubbing, something else that had to be done. I thought that I now knew enough to save myself some time and emotional energy not having to worry so much about gear, load and camels. I had to acknowledge the reality to myself, and there was no getting past it, I still had plenty to learn about the mechanics of camels and their saddles and one other very important thing: patience.

As I rolled over to sleep in the bivvy bag, I felt something run over my neck and across my face. It sensed it stop on the canvas of the swag. Clicking on my headlamp’s light I was greeted with quivering antennae and the largest centipede I had seen in some time, a good 30 centimetres, ceramic green and red, certainly with a painful bite. It was most unwelcome and with a flick of my wrist I sent it into the wet darkness.

Next morning the sky appeared to be clearing, though everything was wet. I spread out the gear to dry over green and sepia mulga bushes and put the camels on long lines to feed. According to reports on the radio, 112 millimetres of rain fell in parts of western Queensland the previous night. The table drains that carried water from the track were silt-laden bogs.

Late in the afternoon I met Julie Moore on her motorbike, out rounding up goats. I saw her coming in the distance, skinny white teenage legs, thin T-shirt and sandshoes but no helmet. In her lap sat a small fox terrier who yapped at the goats and me, but not at the camels. Julie told me she spent five days a week boarding in Charleville going to school, and the weekend at home. I asked her if she wanted to leave the mulga country and she looked at me with a bemused smile and gently shook her head.

She said I could stop by her place; her parents knew I was coming. I did, ‘just for a cup of tea’, and met Richard, who was working on some yards near the house, Liz, who had been working in the garden, and six-year-old Rosemary who scampered down the path from the house. She met me and the camels and was quick to show me her front tooth that was close to falling out. ‘Won’t the tooth fairy love it?’ she asked.

As the tea was being poured rain began to fall again. Richard and Liz glanced at each other for a moment and invited me to stay the night. Over dinner, Richard told me that the only way he could keep his place going was through raising and selling goats. There was no money raising sheep and the country could not sustain sufficient numbers of cattle to make the property financially viable. So he ran goats, all the while knowing the damage they do to the land. They grazed any grass they found to the root, and when there was no grass left they climbed into trees to eat the tender shoots of the eucalypt. Later still, when there was little else, they stripped the bark off the trees and killed them too.

Richard trucked the goats to the Charleville abattoir where the animals were butchered and sent overseas, mainly to the Middle East. Richard was caught in a bind, and he knew it. The goats were the things that kept the property in the black. Just. They were also the very things that would slowly, but very surely, kill the land he loved.

Goats were also the prey of unwelcome visitors from the city. Richard showed me a bullet hole in the side of the house. Someone after a good trophy head had shot at a goat from the road, not knowing or perhaps even caring that people lived in the house.

Leaving the Moore family, who headed off to the Charleville Show at around 10, we walked to Langlo Crossing. Langlo Crossing was marked on my map as a village. Maybe it once was, but not now. There was just one house and it looked very lonely and empty to me. I saw it from a way off, the corrugated-iron roof bouncing signals from the sun, the curtains drawn and no sign of people about. I did not even knock on the door.

A little way along to the north-west, we walked down into the river crossing and a narrow wooden bridge. As we approached, the camels became very nervous. They could see through the wooden planks to the brown flowing water beneath them. I told them there was nothing to worry about and tried to reassure them by speaking softly to them. Despite this, we finished the five metre crossing at a camel canter and there was lots of creaking of gear, deep sighing and blowing of cheeks. I turned to see Kashgar squirting liquid shit in a slippery green-brown arc to the east.

I felt pretty low in the morning and soon developed a headache; perhaps I had not been drinking enough. Even so, later in the day I felt better, the best I had for days. As I sat on the swag looking into the fire and beyond to the stars, I thought I could see a little of myself in both. The further west we headed the more connected I felt to the land, as if it was on, in and under my skin. I felt that a part of me was letting go, and another part of me was opening to the country.

I rolled out the swag and slipped inside, put my hands under my head, looked to the stars and sighed. My swag was a wonderful thing. It was my seat and my rip-stop canvas home that rolled up with many of the things I needed inside. I had the swag made to my design, in three parts. The central part was twice the width of my body, its length 60 centimetres longer than me with deep sleeves at the top and bottom and 30 centimetre flaps. A dense mat fitted into the sleeves as well as my shaving gear, small towel, diary, headlamp, spare clothes, small radio and sewing kit. On one side a similar length and width and the other side, double the width and the same length. This meant that when unrolled, the flap supplied a working surface where I could lay out gear and do sewing. Even if I dropped a needle, I could find it. I also had brass eyelets set into the corners of the widest side so that I could use the flap as a lean-to.

Walking the track we encountered the corrugations that reminded drivers they were in the country. For us they were even lake ripples, the height depending on when a breeze blew to freeze the waves before they broke. They were something to be crossed, the boot not able to plant itself squarely on the ground, and every day I felt my tendons stretch and bend, and my lower back jar. I slowed to a stroll to give the camels ample opportunity to feed. Chloe’s small rubs looked like they were healing up and she was looking fatter and fatter.

That night I turned on my small radio to a rugby match and the caller described the contact of men. To cries of ‘he’s got the ball’ I imagined the crowd of colours, cheering, crying and catcalling. It was a world away, of beer in plastic cups and corporate boxes. I lay in my swag looking at the darkness punctured with flickering, blinking light. To lie in my swag, the licking light of the fire, the company of the camels and the trees and watch the pinpricks move against the great dark dome was a gift of life and time. I felt so elated, so fortunate and so privileged I felt short of breath and almost guilty I was not sharing it with someone else.

Just after dawn and a night of dreamless sleep, I lay in the swag and looked out onto mulga ants’ nests, small cities raised above the hard red ground with the mulga leaf roofing like a thatch to prevent flooding. There was something about being out in the red soil country, the mulga, something clean about it. I was up and moving early to shift the camels to different trees on their long lines. Once they were happily eating I had breakfast, packed up the camp and moved off again.

Geoff the Adavale policeman, his wife Rhyna, Sam their son, and Tina the blue cattle dog came out to dinner from Adavale, bringing with them quiche, casserole, olives, beer, coffee and good conversation. Their generosity almost overwhelmed me and I simply could not fit it all inside me.

I had the fire going and the camels were tied to mulga trees that they ate in their measured and leisurely way. It seemed to me that Geoff wanted to discuss the nature of things – life and why we do the things we do. His wife, though, was not at all keen to see her man lapse into a discussion of this type. She seemed far too sensible for that and instead insisted on turning the discussion to children, air-conditioning and the quality of water to wash her family’s clothes.

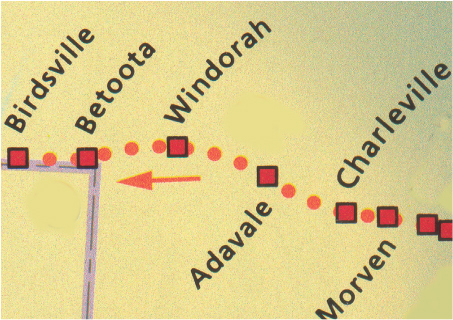

Rhyna and Geoff told me that the route I intended to take north-west from Adavale to Windorah was an old Cobb & Co. track only rarely used, and not in recent memory. I was looking forward to it. They seemed a little dubious about my taking it at all until I convinced them that if I did have a problem I always had an emergency locator beacon close to hand.

In fact, I had plenty of safety items, including a headlamp. I set the Petzl lamp on my head and before the generous and friendly family left I made a brew. Instead of the black stuff I had drunk for so long, Rhyna had brought some milk. As I poured it into my cup canteen, I watched it become an exploding nebula in the darkness of the coffee, spreading like the obsession that my walk had become.

Next morning it was after 0800 and we still had not moved off. The camels were tethered to mulga and browsing on the slim grey leaves. After another heavy dewfall, I dried out the swag and its contents. It was cold too, so over my greasy hair I pulled on my woollen beanie.

When I tilted my head to the sky I could see a trailing white fanion and its silver cause headed south, perhaps on the way to Melbourne. Would I rather be up there? No flies, no dirt, no damp, no camels. Be clean and be served a fresh brew of coffee? Even with my greasy shirt on my back, not at all. I loved being on the ground, with the red dirt, the animals and the sunrise a promise of hope in the east.

Passing rivulets and creeks not far out of Adavale I could see from the water-marked bank that the levels from the flooding of a few weeks ago had only recently dropped. We were fortunate to pass the concreted flood ways. In the washaways to the side of the track the fine silt had already formed dark parchment scrolls, leaving lighter brown coloured clay underneath.

On the track just outside the six-house town of Adavale I met Gracie Woods, self-styled Queen of the town. Gracie told me there was to be a barbeque that evening in my honour. People from stations all around were coming to see me and the camels. As Gracie said, ‘Any excuse for a get together to talk and drink something. And yeah, we heard you are a good bloke.’

An hour or so later I set the camels loose in the police house yard where there was plenty of feed for them. Geoff, Rhyna, Sam and Tina the dog met us at the gate and even had lucerne bales under the house, which I gave to the camels next morning.

The barbeque was held at the local hall and attended by more than 30 people. Some even flew in from Charleville for the event. After a warm introduction from Geoff I spoke briefly about the trip, the work of the Fred Hollows Foundation, and thanked everyone for coming. The Landsbergs from Milo Station stood next to the fire drinking rum and told me that at one time Milo was a station of a million acres fenced and a million more unfenced. Now though, due to time and taxes, it was much reduced. There just were not the people to manage it, so sections were sold off or simply handed back to the state government.

The barbeque finished up late, well after I excused myself from overindulgence in a potent home brew to write letters home. I finally packed up, with letters written and all farewells complete at mid-afternoon next day. Among the letters I wrote two were especially important. The one to the Fred Hollows Foundation included further donations and a brief outline of how the expedition was doing. The other was to Amber, to tell her how sorry I was that I could not speak with her. Due to some localised flooding, the phone lines out of Adavale were down and were expected to be down for days. Geoff used radio to keep in touch with the outside world.

Geoff went to Quilpie so I hoped Amber would have the letter the following week. Otherwise, given routine collections, the letter would not be collected until the week after, and probably would not reach her until the end of the following week, if not later. It was an odd thing that a letter posted in Washington or London would arrive in Canberra well before a letter posted in the very same country. Maybe that was the point. Being out here was like being in another country. It was a place few Australians ever thought about and fewer came to see.

Leaving Adavale the camels carried 60 litres of water, more than enough if there was a problem. I let Geoff know that I would stop in at Araluen Station in four or five days and call him. The camels were doing well and for this part of the trip Kabul had 40 litres of water and food, Chloe 20 litres and Kashgar as usual carried little except a camel smile. I was a little concerned about a slight limp in her offside foreleg but she seemed to be okay. The work in Charleville had seemed to have paid off and we had no problem with rubbing or chaffing. I wanted to keep it that way.

As I wrote my diary at the end of the day I could hear the sound of the ‘river on its banks’, the Bulloo River. The next day would mark the three month anniversary of leaving Byron Bay. In some ways it seemed close, in others so very far away. Sure we had come a long way, around one-third of the way across the continent. But there was a long, long way to go yet; including the first solo east–west crossing of the Simpson Desert.

I looked at the map and told my camel friends next day we would move to the now disused Old Windorah Road and follow what was the Cobb & Co. coach route to Windorah. From 1854, when the coaches first serviced the route to the Victorian goldfields from Melbourne, until 1924, Cobb & Co. coaches provided timetabled transport for mail, passengers and parcels throughout Australia. In early 1900 they were using almost 9000 horses each week in Queensland alone. There were changing stations at regular intervals where tired coach horses were replaced with a fresh team. For a time, until the arrival of the petrol engine, coaches bearing the name Cobb & Co. carried passengers and the mail in every mainland state of Australia

Far from being the six houses it was now, Adavale had been a flourishing centre of 7000 people and the hub of western Queensland. According to Geoff, the decision to build the railway from Charleville to Quilpie, and not to Adavale, killed the town. Not that I was convinced Adavale had much to offer as a commercial centre. It was built on a claypan on the banks of an overflow of Blackwater Creek. The heat in summer must have been extraordinary. There was no shade on the claypan as trees could not grow, and even on a late autumn day the reflected heat and light from the hard clay surface bit at the back of my eyes.

Sandra Newland from Bull’s Gully Station pulled up in her Toyota. She asked me why I was doing it. I thought of a pat, too smooth response like, ‘Well, if you’re not Shirley MacLaine or James Bond, you only live once.’ It was late in the day and there was not enough time to explain a burning desire, an ache and a need to move, especially to someone who may not have them. Even so, I tried and Sandra was quiet and gentle with me. She wished me luck and smiled as she drove away.

Some people called me a misanthrope. They believed I travelled on my own because I did not like other people. The fact was that I loved to travel with other people and share the experience, the pleasures and the pains. But the thing that you lost when you travelled with other people was a sense of vulnerability and exposure to the world. It can be harder to meet local people and to enter into their world. It can also be intellectually and emotionally easier when there is another person. When you are on your own, your internal world and the way it interacts with the exterior is the means by which things are understood. There is no distraction, only you. It means that you are responsible for the way in which you respond to the world; there is no filtering or testing. For a lot of people this can be intimidating and very frightening. It was what I sought, it was unashamedly unambiguous.

I woke in the morning to a sound I had not heard before. It was a scratching, accompanied by an occasional liquid bloop. I gently raised the canvas flap of my swag to see improbably skinny long legs pass not two metres from where I lay. When I poked my head out further I could see more of the remarkable legs moving through the camp. The camels did not seem concerned by emus; and the emus not concerned by the camels. There were two adults and six chicks. The liquid bloop, like cognac being poured from height into a crystal glass, was the noise made by the adults as they moved behind and shepherded their chicks.

One emu came very close to the swag, possibly interested in the round thing (my head) that stuck out. It looked at me and turned its head, a green-feathered bulb with a beak on a very long neck. Then it shook itself as if it was not quite sure what to make of the thing with shiny eyes sticking out of the green slug of the swag. It put its head a little closer, its face almost comical in its curiosity, very dark brown eyes looking into mine. I winked and it drew its head back on its long neck, gave a half flap of short green wings, trotted off five metres and continued to search for seeds on the ground. I put my hand under my head and watched the family group move off in a slow and measured way into the surrounding mulga scrub.

The Old Windorah Road was marked on my map as a secondary road but this was very much an overstatement. From the deeply eroded state of the track, where gullies up to a metre deep and wide had been ripped through the surface, there had been very good rain in recent times. I was pretty certain the track had not been used for weeks or months, and not by a vehicle. At the barbecue in Adavale, Les Landsberg had said many parts of the track were impassable after rain. As it was we were just able to work our way through. A week before the area would have been an impassable bog.

The previous day we climbed a shallow escarpment from the eastern edge of the Grey Range and were greeted by the sight of a sweeping plain, of grey-green mulga to the horizon, interspersed with three or four orange-red claypans under a line of crystal blue sky. With its patina of green it was like looking at an ancient Persian carpet.

We walked up a track to the Grey Range proper, where at 265 metres above sea level the view to the west was bright light and blue. In the east, the mulga sank away and melted into the horizon while in the middle distance a windmill with broken blades winked morse at me. A quick look at the map made me think we might reach Araluen Station late next day or early the day after.

As we walked along the track I thought about loneliness and particularly a book by Geoffrey Moorhouse titled The Fearful Void. In the course of his trip across the Sahara, Moorhouse reflected on the fact that the Point of Aries is the creation of man. There is no such point except that all the heavenly bodies are related to it. It enables navigators to cross the world as it is the point around which all the stars turn.

For Moorhouse, people are like the stars, spinning through life and God is the spiritual Point of Aries. Without God people are lost, spinning through what Moorhouse called ‘a fearful spiritual void of the spirit’.

I wondered about that. The Sahara was certainly not ‘the fearful void’. After all, how could we attribute an emotion or meaning that it does not have? There is nothing fearful in it. The fear there does not have a name. We cannot meet it because fear can only exist in ourselves. And there is certainly no ‘void.’ There is meaning wherever there is a human and there need only be fear if we give it life.

Just because we did not understand, did not seem to be able to find the connections or a meaning, or felt alone, did not mean we needed to feel unsafe. There were a lot of things we could never control. Places, whether they are inside us, or outside like the Foreign Legion or a desert, are not inherently strange or frightening places, just new or different ones where we must adapt, explore and try to understand. Most importantly, we have to understand that fear comes from within, and when the outside acts on us we may respond in a number of ways. The really difficult thing was to acknowledge that the way we view the world is a fundamental part of ourselves.

Some people I knew were fearful of new places, new experiences, new people and new ways of thinking. They were so fearful they tried hard to control every part of their lives, so that there was a sameness and constancy in their lives. A day would become stressful if something happened that was outside their control. Where there was no control some people reached outside, to God or money, to provide order or make sense of things.

To me, change and uncertainty were elemental, the stuff of life, and safety was an acquaintance who wanted to become too close. Why not embrace the fear, welcome the hollow feeling that comes with uncertainty and let your heart beat wildly for what the future might bring? I wondered if I would feel the same in the Simpson Desert when there would be less that I could control and the possibility of success far from certain.

I liked Moorhouse because he made me think. He made me realise that my journey was a reach for understanding. Did I really have to separate myself from the world I knew to get to know myself? Had I cast myself adrift like some religious ascetic to touch something inside myself? Did I really know what I was looking for, or was the looking for something enough?

Coming over the Grey Range, and just before a bleached rocky feature I saw on the ridge a number of weathered wooden posts next to an unusually dense collection of native scrub. To satisfy my curiosity I tied off the camels and walked over to the site. It seemed to have been a holding yard, and perhaps there had been a spring. An exposed miserable location, I thought it was most likely a staging post in the coach ride from Adavale to Windorah. I sat on the edge of the ridge and looked east across the sea of grey-green. Waiting on this sun-smashed ridge in summer for the coach to arrive must have driven some people mad.

The camels and I descended from the range and crossed Sandy Creek to where the land opened up to reveal the greenest country we had seen since Toowoomba. It was a country park, a green meadow to the horizon, starred with yellow and purple flowers and the occasional tall eucalypt to provide shade when resting. It was not easy to have the camels move along at the usual pace, all they wanted to do was rip up the green stuff and eat.

At the creek, just before moving up to the Araluen homestead, the camels baulked. Kabul started dancing, or maybe more accurately bouncing, lifting his fore legs and then his hind, trying to buck off the saddle or his fear. Chloe and Kashgar soon followed and I found myself holding a line with three prancing camels. Something had unsettled them but it was not obvious to me. A few minutes later I even had trouble unsaddling them. Perhaps it was the pigs kept in the pen not far from the house.

We arrived at the homestead just before dark. The home of Annie and Colin ‘call me Collie’ Rae and their daughter Colleen, their youngest, who did distance education on radio out of Charleville. Over a beer Collie told me he and his father came out here in 1968, lived in tents, then a demountable and later another prefabricated house, building up Araluen Station to what it was now. And the yards on the hill? According to Collie they were part of the Jack in the Rocks Hotel, a Cobb & Co. stop. At one time the pub was run by Mrs Tully, a family name prominent in the history of south-west Queensland. She was found dead on the pub floor. Collie reckoned that her husband did it but was not sure how it all ended up. In answer to another question I had about the vegetation there, Collie said there had been a natural spring. In the 1960s some mining exploration blokes had tried to make the spring wider, but only succeeded in closing it and sealing it from the animals around that depended on it. ‘They rooted it,’ Collie said.

As to the open paddock, Collie told me that it had not been cleared by him. ‘Just natural,’ and he had a ‘good block’ – ‘three by three’ which was one part open country, one part mulga, one part stony and rocky. This meant that in a good season the land could give a good deal back, in bad the mulga carried the sheep, and ‘rock because everyone has to have some!’

I called Geoff in Adavale to let him know I was okay and then called Amber. We were gentle with each other, careful not to prickle at being apart for so long. As surely as I was making my way across the country I felt I was losing her. There was nothing to do but give up now or finish as soon as I could. For my own soul I chose the latter.

Later, over dinner, I admired Collie’s collection of trophies, mainly for boxing. ‘Amateur. Middleweight,’ was all Collie would say. I told him that I had boxed myself. ‘Amateur. Light Welterweight.’ He sniffed but I am sure he looked at me a little differently. He thought I was some soft bloke from Canberra on a holiday.

Along with helping Collie work the land, Annie was the proprietor of Quilpie Quilts, a famous company of western Queensland. I had an image of shearing sheds and ladies working hard at their machines. But there was only one hard-working lady, and that lady was Annie. She worked hard for the cash that such enterprise brought.

In single file, leather creaking, camels and I left Araluen around midday. Despite our late start we made about 20 kilometres toward Windorah. As we left Annie was bent over a machine, working on a quilt order, while Collie worked parts of the garden. Colleen came with me to the front gate and saw me off with a wave and a laugh.

That evening was so quiet I could hear the pulse in my ears again. There was no moon. No sound, bird or cricket. Nothing, that is, except for the occasional roll, fart or chewing of the cud. As the firelight shortened its reach, the stars seemed brighter still. The Southern Cross appeared almost directly overhead and to the west a sapphire planet invited me to follow.

It was a good day’s walk from the edge of Araluen to Canaway Station, through parts of Thylungra Station. We came across five young cattlemen from Thylungra setting up steel fabricated mobile yards, preparing for a cattle muster. It soon became clear that they had not expected anyone moving in from the east. After one pointed in our direction they all turned as if choreographed in a western revue, left hands on hips wrapped in tight jeans and primary coloured shirts, right index fingers pushing up the brim of their very tall hats.

As camels and I approached I said, ‘G’day’. Almost as one they replied, ‘G’day’ too, but each one with his own questioning lilt. I said, ‘Headed west’. A couple of them said, ‘Yeah, right’. And that was our meeting. Sometimes, even when there were very few people around, it seemed right to say little and not waste time or words.

We continued to Regleigh Station country where I met Russ. He pulled up in his white Toyota utility, put his red-capped, blotch-brown freckled face out of the window, shook his head and said, ‘The things ya see out in the bush.’ He told me he decided to inspect some bore sites as Jehovah’s Witnesses were visiting the homestead. ‘Can’t stand ’em,’ he said.

Russ told me that while Adavale had up to 10 inches of rain already this year, this country had only seen three. After I told him about the lads from Thylungra, Russ said thoughtfully, ‘Yep, Thylungra, it’s on bloody good country, lots of creeks and overflows. Old Man Durack, one of the first blokes out here, was no fool; he just fenced off the country he wanted. And then he went off to the Kimberley. What a family.’

In the morning I stayed in my swag until the sun reached the horizon, my usual practice being to get up at first light, build up the fire, put on the billy and move the camels to better feed. But this morning I reflected on what T.E. Lawrence had done in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, lay back in the swag, and let the day come to me. I cupped my hand under my chin and waited with my senses. I saw, felt and heard the crowing of a distant crow. Kashgar chewing her cud. A strand of spinifex was golden wire. The limbs of a tree reaching for the sky. A dewdrop on a stem of grass, a diamond suspended on the ear of a woman. Colours moving from black and white to shades of grey, to the red of a flower, the yellow of a grass stalk and the green of a leaf.

In mid-afternoon we finally made it to the single-lane black bitumen road that made its way across the old skin of the country. It would lead us to Windorah. I thought that we should be able to make it to town by Sunday afternoon. I needed a rest day to make telephone calls and my belly hungered for mixed grills with lots of chips and eggs and ice-cream.

I looked for a camp but I could not find trees or bushes that the camels might eat. Late in the afternoon I saw a line of acacia bushes in a watercourse. We made it just two fingers before sunset and soon after it was saddles off and camels happily munching. Rather than use my watch to set when we should camp, I used the sun. I held out my arm at full stretch from my body, my hand before my eyes, fingers below the sun and parallel to the horizon. If the sun was three fingers from the horizon I would have enough time to pull up, unload and put the camels onto long lines to feed. I also had time to collect wood and get a good fire going, lay out the swag and set up the camp the way I liked. Sometimes though, finding a good campsite was worth a little inconvenience, especially where there was food for the camels.

On the only road to Birdsville from the east, the track was very quiet. Only four cars and five road trains headed in my direction. In the late afternoon Maureen Scott pulled over on her way home from the weekly shopping at Quilpie 200 kilometres to the south. She offered me a bed and dinner. Her daughter Carly had heard one of the children at Adavale on radio talking about the camel man and she decided to watch out for us. And there we were on her doorstep! I thanked them both for their offer but we were still few kilometres too far away. I promised I would stop by next day.

Maureen and Bruce ran Moothadella Station just off the highway and not far from Windorah. They invited me in for morning tea while the camels had theirs in a lucerne paddock. Morning tea with the Scotts was a taste of civilisation, with coconut crumble of lamingtons washed down with sweet tea from cups that sat on knitted doilies. Sitting at the dark timbered dinner table under dark framed photographs of stern faces, I noticed myself talking too loudly and too quickly. I wanted to share my experiences and reconnect with other people. Maureen and Bruce shared a glance and their faces softened in mutual understanding. I slowed down and was quiet for a moment.

Bruce wrapped his hand around his teacup, and between sips said, ‘You know, this Channel Country is almost 300,000 square kilometres, marked by hundreds of shallow river courses and wide alluvial plains. It’s a tough country; it asks a lot of the people who live here. Even so, you know I’d never leave it, with its enormous skies and the people who are connected to the place.’ He looked to Maureen and said, ‘It’s a part of me and a part of our family’. He went on to wonder why so few Australians seemed to want to see and taste what the Channel Country had to offer.

I speculated that it was not time and distance from the coast, it was more likely its difference from the cities that made it so alien, unpredictable and perhaps intimidating and therefore uninviting.

Bruce and Maureen nodded and Maureen said, ‘Hmm, well, maybe that’s part of it; but how could you feel something that was intimidating and alien that was a part of yourself? Why not try to understand that part?’

I smiled and said, ‘I think you’re right. But then, how many people are truly prepared to confront themselves?’

Later, after another cup of tea, I went to the lucerne paddock and my friends and clipped them together. Maureen followed me and pressed a plastic packet of frozen sausages into my hand. I slipped them into Kashgar’s care and that evening as the saliva filled my mouth, cooked them with Tabasco sauce, pepper and salt. Never before had sausages tasted so good. I ate all nine and as my belly swelled and the fat coursed through my body I felt re-energised and warm.

After more than 2000 kilometres of walking, the Deadman Bridge over Cooper Creek was the last we would have to cross before the west coast more than 3500 kilometres away. The Cooper is one of the four main watercourses of the Channel Country, which includes the Georgina, Diamantina and Bulloo Rivers. The bridge itself was a significant marker, and another test. Charles Sturt named the creek in 1845 and wrote, ‘I would gladly have laid this creek down as a River, but as it had no current I did not feel myself justified in doing so.’ He would have written differently had he seen the creek the day we crossed it.

So there we were, camping on the Cooper where, as Banjo Paterson put it, ‘the western drovers go’. We had worked very hard to get to the bridge and it felt exciting to be there. For the camels there was galvanised burr and pigweed in abundance. Just past the turnoff to Hammond Downs, a cattle station taken up by Europeans in 1877, there was so much pigweed that as I walked down to the creek I could feel the water-laden leaves burst and flatten under my boots.

If we could successfully make our way across the bridge I thought we could make it into Windorah next day. Camels in general, and I knew my three friends in particular, had no fondness for bridges and we tried to avoid them where we could. The last bridge crossing, at Langlo Crossing, had been a near disaster, but with the experienced and steady Kabul in the lead I was sure we could make it across.

I needed a day off in Windorah to do the administrative things that the expedition required, like calling supporters and writing letters to friends and sponsors to secure a mobile satellite phone for the Simpson Desert crossing. I wanted to make Birdsville on 20 June and it seemed to me to be very possible, with the distance just 400 kilometres. So, around 20 easy kilometres a day.

On another front, I was a little worried about my brain, about intellectual stimulation. I had read a couple of books, but during the day it was impossible to read. I learned plenty of Banjo Paterson poems but I knew my brain needed more exercise. Thoughts were becoming mere fleeting fragments, and I was becoming unable to concentrate on a train of thought longer than an impression or a feeling. I knew I had to make myself think, not just act, so I carried a notebook in my pocket and wrote down feelings, dreams and observations, to collect them and give them form. Otherwise I found myself dwelling on the past or becoming fixated by the map and obsessed with distances.

Camels and I made it into Windorah 10 kilometres after crossing the Deadman Bridge. The Cooper had risen and I could hear it lapping against the concrete supports. There were no sides to the bridge, just elevated concrete, maybe 15 centimetres high on its edges. We walked onto the bridge and I looked over to see the water, a swirling dark brown just under the road. We had more than 100 metres of bridge to cross before the safety of the western bank. As I stood on the eastern side, contemplating the gap, it looked a lot, lot further.

Before we began the crossing, I asked a couple of passing motorists to lend a hand. I asked one to stop and flag down any vehicles that might follow up behind. He agreed and his mate in the vehicle behind agreed to go to the other side of the bridge to stop any other traffic from the other direction. The thought of a 50 metre long road train bearing down on me and three camels was terrifying.

Then we started. As I had done so often before, I relied on Kabul. I patted his neck, caressed his wool and told him that this was probably our last bridge to cross before the coast and the Indian Ocean. With a flare of his nostrils he sniffed the air and moaned a low moan of uncertainty, perhaps fear.

Even so, we began our walk across, the three camels looking very regal, noses in the air and the pink of their nostrils winking against the matt of their skin and woolly coats. They could smell water and lots of it. Only when Kabul could see the water did he really become nervous. There was nowhere to cross but this narrow band of concrete.

Kabul began to make more nervous noises. Low throaty moans were a deep whimper that told me he really was frightened. I kept turning around, touching his nose, patting his face and reassuring him and Chloe and Kashgar that everything was fine, that all would be wonderful once on the other side. Despite the warmth of the day, I felt the thick cold snake of fear wrap around my chest.

We were getting closer to the other bank and I could see the gap in the trees on the far side of the bridge where the road climbed the bank into open country. For some reason, though, the gap began to close. I narrowed my eyes to see 20 people gathered at the end of the road to take pictures of the camels crossing the bridge. They were across the road, and as far as Kabul could tell there was no way out.

Kabul kept moaning. Finally he baulked and stopped. I caressed his face. I reassured him in the calmest voice I could muster. I cried out to the people to move off the bridge and could see some people urging others to move to the bank. Some refused. At last, though, the dark smudge of people moved enough so that there was daylight behind. We carried on and finally made it to the bank.

Some people, clutching their cameras like a tourist’s tika, said, ‘Can you go back a bit? I want to get a couple of good shots.’ There were so many people standing around, making so much noise, I could not quite make out what they were saying. A little way from the crowd one lean man folded himself into a hunker, rolled a cigarette and said, ‘Would never had believed it if I hadn’t seen it myself. Could never have got horses across like that.’

Around mid-afternoon, on the outskirts of Windorah beyond the turnoff to Jundah, a town to the north-east on the track to Longreach, we were stopped by a cattle grid and a padlocked gate in a new tightly strung fence that stretched as far as I could see. On the other side of the fence working in a small bobcat was a mahogany skinned man loading soil into the tray of a large truck. In what I hoped was a nonchalant pose, I unclipped the camels, tied them onto feed trees, jumped the fence and leaned against the gate. Then I waited until I caught his attention. He glanced over to me and indicated with a tilt of his head that he would speak with me once the truck had been loaded.

Merv Geiger stepped from his bobcat in boots, shorts and blue flannelette shirt. We met each other halfway and reached out our arms to shake hands. Merv took my hand in a firm handshake slightly moist from work and gritty from the soil he had been moving. He looked at me with extraordinary eyes, eyes that saw me but seemed preoccupied with another place at another time. Merv’s eyes were faraway eyes. I had seen them in the faces of Legionnaires returning from patrol.

‘How can I help ya?’ he asked with lips that seemed to curl up into a quizzical smile. I told him I wanted to bring the camels into town, check in with the police sergeant and eat at the pub. To get in I needed the key to the padlocked gate. ‘No worries,’ he said after a slight pause, ‘let me drop off the load and I’ll chase up the key.’ Only later, during a discussion with the police sergeant, did I learn the reason for Merv’s hesitation.

Merv was back in half an hour. He opened the gate, we passed through and he locked it again. He indicated where the police sergeant’s house was and said ‘You won’t have any worries there. Kevin is a pretty good bloke.’

Merv was right. Kevin let me put the camels in the police yard and while only 20 metres by 30 metres square it still had plenty of food for the camels. ‘Don’t thank me,’ he said, ‘I’d just have to mow it or something anyway. You’re doin’ me a favour.’ I was glad he thought so.

I discussed with Kevin the road forward and when I proposed to be in Birdsville. ‘No dramas,’ he said, ‘looks to me like you’ll do fine. Otherwise you wouldn’t have got here. Geoff told me you were okay.’ He paused for a moment and said, ‘You must be a silver-tongued bastard. You know why there is a lock on the gate?’ I told him I had no idea. ‘Blokes from around here used to drive their cattle through town. It meant that apart from a few old gums there was no green in the town. Some people, including Merv, got a bit pissed off by it all; put a fence around the town, with a grid and a padlocked gate. Now there’s some kind of council by-law that prohibits grazing animals from entering town. Merv’s on the council and if he reckons you can come in, that’s okay by me.’

Kevin watched me unload the camels and lay out the gear. After the camels were brushed and patted and settled in, I moved off across the road to the Western Star Hotel where my first question to the barmaid related to when the dining room opened.

The Western Star Hotel was serving beer before the town of Windorah, from the local Aboriginal word for ‘place of large fish’, was first surveyed in 1880. I spent two long nights in the dining room of the Western Star Hotel. Wonderful dinners they were, of mixed grills with chips and salad, followed by ice-cream. It took me a couple of hours to make my way through it all and I was one of the last to leave the dining room. A couple, he in creased khaki and she in pastel polyester, kept looking across at me and then leaning forward to share quiet conversation. I had never thought of myself as the most attractive of men and never really cared if people look at me or talk about me, so I waited until they both looked at me and gave them a big wink. They smiled at me warmly and simply said, ‘Good on yer mate. Hang in there won’t you?’ They then got up and left. I was glad I shut up.

The proprietors of the Western Star, Ian and Marilyn Simpson, were like so many other people, patient and they spoke quietly to me, as if I was something delicate and easily damaged by loud noise and ugly words. Ian also shared his knowledge of the working bores on the route to Birdsville as well as a couple of beers. Marilyn went out of her way to see that I had enough to eat and that my clothes were clean.

The camels looked rested. When I checked them again in the afternoon they were down on their pedestals, languidly chewing the cud, bending necks and blinking brown eyes at me. They looked better than ever, with large humps and muscled rumps, and very relaxed in my presence. Seeing my friends so well I headed for the front bar of the hotel for a beer. Sitting and listening I breathed cigarettes, Bundaberg Rum, love for the land and sometimes, in the silent places between words, a quiet desperation among some, born of loneliness and open spaces.

I spent two days cleaning gear, telephoning and writing to sponsors, organising a loan to keep the expedition going and calling the police in Birdsville to let them know what I had planned. I spoke with Amber and she was very keen on meeting me in Birdsville. I told her it was not necessary, all the supplies I needed could be freighted to me. She insisted and I could not deny that I would be very happy to see her again, even though it might mean having to talk about our future and possibly the future of the trip.

I lay in the dark on a Western Star Hotel bed. It was the morning before moving off again and I had a crisis of nerves. It was a sinking feeling of desperate fear; a crisis of confidence. What would happen if I failed? I would look a fool and some would say that I had attempted something beyond my knowledge and capabilities. The years of effort, the dreams of achieving a goal would dissolve and the energy and enthusiasm dissipate. It was a good thing that the cockatoos flew from a couple of nearby conifers. As they wheeled and banked across town on their broad white wings they dropped near with their cry of ‘Wake up! Wake up.’ And I did. As the sun rose it warmed the day and chased the darkness from my mind. I knew that sometimes I felt very, very vulnerable. It was the price I paid to be alone; I had chosen to be exposed and I wondered if the risk of failure made achievement even sweeter.

Merv Geiger opened another padlocked gate to let us out of town. He also gave me a donation for the Fred Hollows Foundation. As he shook my hand in parting he looked at me again and I had a feeling he was trying to tell me something with his eyes. His family had been part of this country for a century. Some of them lay in the ground not far from where we stood together for a moment, silently regarding each other. I felt that at the same time the land hurt him he needed it, to be on it, working it and touching it. ‘Take care out there,’ he said, ‘sometimes the country can ask a lot of a man.’

Just out of town a snake crossed our path, a glide of snake belly on tarmac. It was so long it almost traversed the road. It paused for a moment, its purplepink tongue tasting the air. Kabul snorted and we watched the snake’s languid movement as it bent its way from the road and into the scrub. In the afternoon rain fell in the east; I could taste the moisture and smell the ozone in the air.

We camped around 10 kilometres west of Windorah. I found some wooden cattle yards on the northern side of the road full of good feed. Once unsaddled and brushed, the camels grouped themselves in the north-west corner of the yard, all looking west. I wondered what was on their minds. Did they know something I did not? They were dark grey smudges in the west where the sunset put the horizon on fire. That evening was the first I had seen the camels against red desert sand and they looked very much at home. I lay in my swag writing up the day in my diary and again worked out the distance to Birdsville, around 20 days.

As I sat on the food tin next morning waiting for the billy to boil, I consulted the camel man’s bible, Camels: A Compendium by Manefield and Tinson. I decided it was time to start conditioning of the camels to be without water. Popular mythology has us believe that a camel can go without water any time there was a need. Not quite. Camels have to be conditioned to water deprivation, to allow their physiology time to adapt. In the past week or two I had deprived them of water for up to three days. On the track to Birdsville I proposed to formally start the program. Three days, then a drink, three days, a drink, four days, a drink, and so on. According to the book a camel could go without water for 15 days and could cover up to 1000 kilometres in 20 to 30 days.

Next evening we camped on the Whitula West Bore. I went to the bore to see if there were any cat scats that might be of interest to Walter Boles from the Australian Museum in Sydney. The droppings were a record of recent cat consumption of small things – too often small, almost extinct Australian marsupials. Arriving at the bore I found it full of pigweed and galvanised burr, and even though we were about an hour short of our usual stopping time we made camp and I let the camels free to graze in the bore’s holding paddock. The camels took a long time grazing before they stopped eating, and then settled themselves down to chew the cud.

Then there were birds of prey; from the large wedge-tail eagles to the smaller black falcon and spotted harrier. Beautiful birds. For some reason I felt as though these animals were keeping an eye on me, from the sea eagle on the very first day. I kept an eye out for them and scanned the sky, and somehow, as if it was a reward for continuing to try, every day I would see a bird of prey.

Later in the evening I had a wash in the dam, including a delicious wash of my feet. The level of the water was much higher than the surrounding land, the sides of the dam having been built up over decades. That was why this type of dam is called a turkey nest.

Leaning against the steel leg of the windmill I watched the camels feeding or chewing the cud and looked up to the country around. Just before sunset all I could see were primary colours, the blue of the sky above the purple of the horizon, the yellow of the sun, the red of the earth and the white exclamations of the cockatoos in the dark green trees. I watched Kashgar watching the cockatoos coming to drink at the bore trough. She seemed to find them amusing. I thought the curl in her lips told of a pleasant distraction. Or was it disdain?

That night, and I was not sure why, I dreamed of the Foreign Legion. Perhaps the dream was provoked by some people who drove by and poked cameras out of their car at us. They did not stop, question or smile. What they did was aggressive and insensitive. For I moment I wondered how their memories would sit with their photographs. As for me, I remembered sitting at home thumbing through some old photographs and being taken back to a different time and place. And so I wrote what I dreamed next morning, with the cockatoos screeching their call and the camels waiting patiently. I called the poem ‘Like You’ and it was five years of my life:

Like You

Photograph.

Jesus Christ on your back, a trophy.

Green beret and golden flame sits on the back of your head.

Two golden stripes of rank a velcro tab on your chest.

Hands that could never take a tan, luminous on your hips.

Black boot on the wheel of the truck still holds its sheen.

Your smile is a sucking wound.

Photograph.

Hands red and broken.

Ropes, rifles, rocks and running.

Commando badges on the Red Sea coast.

You are our instructor in all things.

Photograph.

Sunset over the Gulf, bleeding on dark blue.

Above the collar of your shirt the crown of thorns caresses your neck.

Your skin wrinkled and creased by the sun.

The young Legionnaire surrenders and allows your arm to embrace him, a lover.

Photograph.

The jump.

My only friends a rifle and a miracle green wing hanging in the heat of a pale blue dome. Over desert brown and a grey green sea of acacia.

One of us lost, caught in the grey green.

The thorns penetrating, piercing, capturing his body.

His ripped wing a shroud, as silent as his last scream.

My Sergeant says we lose the ones we love. Need to avenge.

Photograph.

The ambush.

Ears ringing from rapid fire rifles and camels and people screaming before death.

Red and white, nostrils flaring and spittle, later blood and bone.

Smell of fear and piss in boots.

Sharp red dots, cigarettes illuminate gaunt faces and the Sergeant herds us together.

He marches us to safety in an ecstasy of stumbling.

Photograph.

The parade ground.

A gravel horizon to lay out the dead.

Sergeant shepherding the ranks of Legionnaires, melted waves licking their boots.

Perfect ranks with bright medals, red, blue and green ribbons, shoulders broad with epaulettes.

Rifles black across chests beneath kepis blanc.

I watch my Sergeant take his shoulders and medals from his body.

He reveals Christ to the light.

I watch the muscles of his back move in anticipation of the work ahead.

The sounds come to me as frozen meat hitting hard ground.

The only grunts from my Sergeant at the sound of knuckle and boot on flesh and bone.

Christ’s eyes are filled, his tears course down my Sergeant’s back.

Photograph.

The corner stabs the base of my palm and my memory.

I half expect to see again the words at Christ’s feet.

The inscription, ‘Comme toi, j’ai suffre’

Like you I have suffered.

Five years in such a place was a long time and the experiences I had in the Foreign Legion remained deep within me. It surprised me, when perhaps it should not, that memories would surface when I least expected them.

Arriving at Canterbury late that day I walked the camels straight to the bore. Only Kashgar drank, and even then it was only a little. After unloading them all near the tanks, Chloe sucked a few sips and Kabul seemed to just wet his lips. So, even after three days they did not seem very thirsty at all. It was clear to me that the pigweed, abundant on the sides of the track, had enough moisture in it to supply their needs.

That evening I lay inside my Gore-Tex bivvy bag inside the swag as the mosquitoes outside whined for my blood. We camped at the Canterbury town bore, on the southern side of the track to Birdsville. Though the township was laid out in 1884 Canterbury was a town of the 1890s. The hotel and township have long disappeared. All that remained was the bore, some ruins and a small cemetery. The hotel was a pisé building and when the nearby landowner purchased the hotel to close its doors – to protect the stockmen from themselves – the roof was pulled off in 1956. It meant that when it rained, the hotel walls turned to mud and melted into the surrounding earth. It appeared that people from Windorah had gone out of their way to care for the cemetery. A well-kept fence and white railings surrounded the ground. With the camels in tow, I visited the cemetery late in the afternoon. I clicked the carabineer just outside the fenced-off ground and walked in.

As well as a number of unmarked graves there was:

In Loving Memory of Our Dear Son George Adam Geiger Who passed away On July 1st 1893 and died from exposure Aged 2 years 4 months

The Geiger family have a presence in the west of Queensland almost as long as Europeans had settled the land.

And a plaque:

In one of these unmarked graves lies the remains of GEORGE TELFORD WEAVE Who died of dysentery here on 9.6.1886 Born London 20.9.1840, Married Isobel Tomkinson 1863, Came to Queensland 1864 and was registered as a surveyor that year.

He mapped much of the Darling Downs until 1881 when his mark took him to SW QLD to survey new pastoral leases. Erected by his descendants in recognition of his pioneering work

The Whitley and Boadle families with Assistance from the Institution of Surveyors Qld. 1996

And others:

In Loving Memory of Kathleen Charlotte Bowman.

Died Nov. 12th 1895 Aged 1 year and 6 months.

EILEEN BOWMAN. Died July 2nd 1901 Aged 2 years and 6 months.

I buried my knees at the foot of the small mounds and wondered what it had been like for those who buried loved ones here; the enormity of the sky, the weight of the heat and the distances to be travelled to a cool drink of lemonade. At least those who lay around me were not alone.

A couple of hours after leaving Canterbury we came to a small escarpment that dropped abruptly to the Morney Plains. Standing at the crest of the jump I could see a wide plain, that once must have been an inland sea, now covered in a rippling sea of grass. Not far along from this place called Jump Up Gap there was a small red-painted cross with a vertical RIP and on the horizontal bar: ‘Red Atherton 31.12.84 Jingles Jones.’ I wondered if they were headed to a party to see in the New Year. If they were, they never made it. I reflected too on the fact that while there were memorials to some, most had none. Their bodies had become part of the land again and memories of them lost and dissolved into the past. Another reason, I thought, that stories are so important.

Later that night a matronly cook named Shirley, who worked at an oil exploration camp along a track just after Tanbar Creek, stopped with us and set up a barbeque. Seeing the fire some other people pulled in and joined us. The evening was filled with stories of stations and shearing sheds, combs and clips as well as lies that made people laugh. They were shearers from Balranald in western New South Wales and slept in their swags near the fire. The oil crew drove back to camp that night.

With so many people close by who laughed, coughed or made too many other noises of massed humanity, I had trouble sleeping. In the brittle night, the fire in the sand and the skeleton branches of acacias black silhouettes against the horizon I sat with Kabul, Chloe and Kashgar. I caressed their muscled necks and spoke gentle words, a reminder to myself that my friends were most important to me. They would see me through the long, difficult days ahead.

After the shearers had gone and just before we moved off, Shirley dropped by again, took some photos and gave me meringues, slice and cake. With a wet kiss on my cheek and a pat for Kabul she said what I was doing was ‘marvellous, wonderful, exciting and moving, all at once’. Then she sighed and wished me well. Finally, with a plume of black smoke from the exhaust of her Toyota diesel, she drove away.

I elected to walk down to the road sign marked ‘Birdsville’ to take a photo and then turned south-west along the track. We had gone two kilometres and were walking into a cool south-westerly breeze. I was walking in the middle of the road with the camels in line abreast behind.

I felt more than heard Kashgar take off first, closely followed by Chloe. I turned to look over my left shoulder. I was greeted to a sight not unlike the etching by Dürer, the four horsemen of the apocalypse, only these were camels and there were only three. My mind registered colour. Red, the colour of the interior of the flared nostrils and mouths. White, the colour of eyes, teeth and spittle. Camel terror.

I normally had time to sidestep Kabul when he took off, but he pushed me into the path of Chloe. She knocked me down. I saw Chloe’s pad come to my head and I thought of the Ethiopian soldier I had seen, his head crushed by the wheel of a truck, his brains squeezed from his skull and splurted over the dusty road like rotten fruit, his face hanging like a mask over the emptiness. For a moment I thought his fate would be mine.

But Chloe missed my head and in tandem the three galloped 200 metres down the road. I lay on the dusty track and thought my dream must be over. I was sure I had broken a femur. I could not move my left leg. I imagined the blood spilling into the tissues of my thigh, slowly killing me and my adventure. After a systematic check I tried moving my leg again, and peeling down my trousers I found nothing other than a couple of scratches and some marks on my thighs beginning to manifest themselves into semi-permanent tattoos.

I hauled myself to my feet, tucked in my shirt and checked the cause of the problem. A car. I had not heard it. Nor had Kashgar until it closed right up. What breeze there was came from the west, into our faces. The driver had moved right up close behind us in an effort to get some good video footage.

I glanced at the camels that had stopped to feed and I hobbled over to the car. Eric and Rohan were on holidays from a Baptist Theological College. Eric had been videotaping ‘the camel man’ and there we were on replay. Me being run down. Eric said he felt very guilty. He even said sorry. He thought I’d be killed. I told him it wasn’t his fault, and anyway, at least he was good enough to wait to see if I was okay.

I walked, or more accurately limped, up to the camels. My intention was to re-tie Chloe’s load and Kashgar’s swag which had worked a little loose in the gallop. I separated Chloe from Kabul and hooshed her down. I left Kabul to continue grazing while I tightened the loads. But for some reason Chloe was not happy. She jumped to her feet and took off at a gallop to the south over the open plain with a bellowing Kashgar in tow. Kabul looked at me for a moment, blinked and then ran off to follow his girls.

Eric and Rohan followed them in the four-wheel drive and I hobbled along as fast as I could. I picked up fallen sheepskin and blankets as they flapped and floated to the ground. The saddles stayed on camel backs and around two kilometres later the camels stopped and resumed grazing. I hooshed Chloe the ringleader, unloaded her and left her in peace. The same with Kashgar. Kabul was fine. He sat himself down and waited. While the camels cooled down, Eric, Rohan and I set up the brew and had a cup of tea. They talked about the journey of life through God. I talked about the journey of life and the search for meaning. We sat and contemplated the small fire and the wisps of smoke that dissipated into the enormous sky.

The two well-intentioned believers left soon enough, though their legacy was pain. Both my thighs wanted to seize up during the afternoon and walking was almost impossible. But this was the test, I reminded myself, was it not? Faced with a setback, pain and fear that it might happen again, take precautions that they will not. I told myself I could not afford to be distracted. I had to stop daydreaming. My body hurt so much there were tears in my eyes, but my heart would never let me stop.

It was only with great difficulty I got out of the swag next morning. I had less than a quarter movement in my left leg. Badly bruised, I clutched onto a tree and leaned back to relieve myself. A tear squeezed from my eye when I started to walk. I could not bend my legs to sit down so I kept moving. I hoped the camels would not decide to try and escape that night. How would I keep up with them?

I was so sore I had trouble moving around the camp and so we got away later than usual. I did not feel too bad as the feed was so good the camels were simply picking or chewing the cud. On the march we paused for a moment, and while the camels grazed I put my arms across my chest, planted my feet better in the sand and tilted my face to the sky. Over the plain I watched a Nankeen kestrel as it hovered for a moment, then began its stepped descent to an unsuspecting prey.

There were lots of tourists. That is, people like me, but unlike me they travelled in four-wheel drives, sometimes with a trailer, to ‘do’ the French Line or the Rig Road across the Simpson Desert. I always said hello and returned their greetings. They were, after all, as much of the landscape as me, and in their way wanted to be part of the odd experience of a bloke and three camels.

Two kilometres short of the Cuddapan Station turnoff we camped on a stand of mimosa and I was sure the camels were fatter. For some reason Kashgar had been quite skittish. Initially I put it down to the brumbies that ghosted our track to the south though maybe it was just being too full of feed and not enough work.

I loved moving across the Morney Plains. The land made my heart beat faster. It was almost Dali; open expanses that left me with the feeling that somehow there were only two dimensions. Here it seemed possible. Rocky outcrops were raw, jagged, dark paintings on the blue sky. The camels ground their plates together, jaws working, chewing their cud. I listened for other life about me and I heard the high-pitched howl of a dingo or the fluttering of a bird, but no insects.

Even though I hurt very much, I loved moving and seeing different things. In fact, while the world’s traditional nomads searched for food, many others searched for meaning. I counted myself among them, looking across the world’s many landscapes for a meaning beyond bondage to a salary or understandings as to future. Even more than this, the search captured a reaching for meaning, something beyond what was normally understood, but that was within us and only exposed when we really exposed and challenged ourselves.

More to the moment, I only just made it out of the swag next morning. I got up in stages and I was on my feet after 10 minutes. I still could not squat to relieve myself so I looked for trees to grab and leaned back. During the day there were a couple of ‘dancing sessions’ of camels cavorting and bucking. Late in the afternoon one dancing session was led by Kabul. Not long after, I found the map case near the tree where I had tied him for the evening. Only hours before had I thought about needing a better way of attaching it than with a single carabineer and reminded myself that it was important to act on an idea, especially when it was to be an improvement on how I managed the walk.

The moonlight that evening was so bright I could make out the different colours of the camel blankets; green, orange, red and brown. I looked across to Kashgar and she looked at me. I could see the glistening in her eyes before she resumed chewing her cud. She was flighty and at times too nervous but I loved her nonetheless. Of the three camels she was the most likely to bury her head in my armpit, and at night she moved as close to me as possible.

But I hated being sore. Because I was stiff and found it difficult to move I was bowled over twice by the camels. Muscles stretched and ripped as I forced my body to move or was made to move. I simply could not jump out of the way of dancing camels quickly enough. I had to accept the possibility of being trampled again, but I did my damnedest to try and ensure it did not happen. I knew I was vulnerable and I did not like it. Even though my body was tired and skinny I liked it because it did whatever I asked. I did not want to hurt it without good reason.

Just before the sun moved above the horizon in the morning, I turned to the west and saw the moon before it set. The dappled sphere was as large as I had ever seen it and solid gold. I returned its smile and, as the fire’s embers flickered, sucked on the sweet hot coffee in my hand.

We must have walked over 25 kilometres as we moved into Diamantina Shire, dropping through a gap that led to a magnificent view of the country west. There was a clear drop to the rusty bowl of the land and a view to the horizon that bent around the sky. I wondered what the Aboriginal people called this country west of the escarpment and sadly admitted to myself that I would probably never know. We camped at a gravel borrow pit full of water at the foot of the drop. After the camels decided not to drink at Taracara Bore earlier in the day, there was nothing but desultory slurps after four days without water, I tried again. That evening though, they really took it up. Kashgar pursed her lips and took more time than the others. I wondered why she seemed to need more when she carried so much less than the other two.

But it was a miserable camp, stony with no breeze to cool my cheeks. I had hoped to camp on something that held better feed for the camels. Dropping down to the gravel pit seemed a good idea, such places normally had plenty of pigweed. Not here. Maybe the ground was too hard. My body was still sore but I felt a little better, helped by a wash in the brown water of the pit. I washed my hair and my body and, despite the cold water, the grit and the mosquitoes, I felt refreshed. I felt so good I smiled for the second time that day and the dried silt of the pit cracked on my face.

On the track next day, just short of the Betoota Hotel, I met Dave Graham. He was on his way to Mount Leonard Station, a cattle station like all the places out here, only 10 kilometres away. He stopped his vehicle and I saw him reach across the seat. I heard a full bottle clink and he said with his head through the window, ‘You probably wouldn’t mind a drink!’ The beer was warm. He had brought the carton in Windorah earlier that day, a place for me that was over a week away. I tied the camels to a bush and joined him leaning against his car.

At 52 years of age he looked what he had done all his life. His legs were bowed, his hands large, dark and callused. His eyes were narrowed from looking too long into the sun, his nose broken from too many Saturday nights in town. The diamonds in his eyes grew brittle and he said, ‘I’m a ringer and a horse tailer. Always have been, always will be. And no one is going to tell me any different.’

Camels and I arrived at the Betoota Hotel, just a boarded-up one-storey stone building, early in the afternoon. Simon Remienko, who people referred to as Ziggy, owned and ran the pub for 35 years and only the year before shut it down, though he still lived there. He had come to Australia from Poland when he was 25, became a grader driver out of Boulia to the north and brought the pub in 1953. He allowed me to put up the camels in one of his outside pens full of pigweed. The crunchy sound of the moisture-rich weed being chewed by my friends was music to my ears.

That night Dave Graham and I sat with Ziggy and talked. We sat in the kitchen with the flames of hurricane lamps flickering – Ziggy had switched off the generator ‘to save important diesel,’ he said. Sitting there, on hard chairs, elbows on an enormous dark wooden table, it was like being in a cave, the light from the lamps stroking shadows on the walls. Dave tried to extract beer, and his eyes keep glancing to the door leading into the bar and its dust-coated bottles, but Ziggy ignored him and wanted to tell stories about drug-running and crime out in the west. He was in his eighties, lean with a pinched face of fear and anxiety. He said he distrusted everyone and when his attention turned to me he could not believe I was doing this trip for adventure and to raise money for a charity. Instead, he turned his head to look at me from the corner of narrow eyes and said in his Polish accent, ‘If I cannot understand why you do things, I cannot understand you. If I cannot understand you, how can I trust you?’

Dave commented that this was very insightful and licked his lips. For my part I asked, ‘How can we ever really know another person; their fears and their hopes? Isn’t it better to treat a person as you would be treated – at least until proved otherwise?’ Ziggy snorted and called me naive.

In the course of that night I did learn that as long ago as 1885 the Queensland government set up a customs post on the bleak gibber plain to collect a toll for stock headed to South Australia. This was discontinued at Federation in 1901. The town was surveyed in 1887, expanded to include three hotels and a police station and became a site of a Cobb & Co. change station. There was little left now though, just the one hotel, surrounded by wire, broken bottles, flapping corrugated iron, enormous views and the pinched fear of one man.

We left breaking camp a little later than usual as the feed was so good, because Ziggy was not up until after 9 a.m. and because it took him so long to unlock the fortress that was the pub. As he moved through the stone building I could hear the sliding of chains and the rattling of keys. Eccentric and fearful? Absolutely, he was paranoid.

Chloe was shitting a bit wet early in the morning and was very flighty in the afternoon. Her udder was so swollen it looked like an inflated rubber glove. There seemed little doubt that a calf was on the way. I wondered when it was due and what I would do when it was born. I decided there was no need for a decision just then so put it out of my mind. I’d worry about these things when the birth occurred.

On the walk from Betoota along the track to Birdsville we followed a mesa that trended west. Small, rust-coloured gibber stones and stunted grey-green leaved trees with white trunks painted the ground of the country sloping gently away north to the Diamantina River. The course of the river was a denser green, a songline of sand, white trunks and canopy shade. It was the umbilical cord to Lake Eyre a thousand kilometres away. To say that I loved this country was not enough; I needed it. There was a poignant sparse beauty in the loneliness, the caw of a crow, the screech of a cockatoo or the loping hop of a kangaroo. Time and space on your own permitted the petty and small matters to dissolve and allowed transcendence and the heart to sing.

I had been carefully checking the map and at last there were sand dunes on the left-hand side, the western side, of the map. Sand dunes! And not long before midday we reached the first. As I sat on the swag that night I knew that at last the real test was about to begin.

That night I tethered the camels to bushes, ensuring the rope was wrapped around the base. There was a yellow flowering succulent plant that the camels loved. It was similar to pigweed with an even greener stem. The camels munched their way through great mouthfuls that I relayed to them from along the dune. While I was collecting I did not have to worry about pricking fingers on a cactus. Cacti rely on seasonal torrential downpours. Here in western Queensland, rain is less frequent than that and these succulents would disappear after only a few months. I placed the crunchy green clumps in sacrificial piles before each camel. They did not even have to stand to eat their fill.

The following day dawned grey and overcast, with the occasional drop of rain and no wind. Later in the afternoon we were slowed down by a mob of brumbies. The horses had probably never seen camels before and were prancing and snorting into the air with the strange smell of them. Led by a large dark stallion, they circled and galloped off, circled and galloped off. At last they lost interest and cantered away to the south. The camels were not alarmed. They just lifted their noses, winked red nostrils and sifted the air for new scents.