5 Across the Simpson Desert

– 24 June 1998

The most forbidding our eyes had ever wandered over.

Charles Sturt, 1845

Camp 1 – 24 June

The camels and I camped on the other side of the ‘ten mile’ dune, named because it was that far from the Birdsville Hotel. It was where Malcolm Fraser, a former prime minister, came for a break from the pressures of office and camped in the desert.

After unloading and turning out the camels on long lines, it was all I could do to cook noodles and heat a can of baked beans before I went to bed. I had a pain in my head that threatened to burst like a live thing from my temple, probably brought on by a recalcitrant Kashgar, loads that did not seem quite right and the stress of the departure from Birdsville.

Everything was done in slow motion. With the pounding in my head I barely managed to bend over and pull the saddles from the camels’ backs. Knowing I was in trouble I forced myself to double-check the knots of each line and give a quiet word and gentle brush to each camel. All I wanted was the deep sleep of the swag and to rest. Before 8 that night I was horizontal and dreaming.

Birdsville is 1590 kilometres west of Brisbane with a permanent population of less than 100. Proclaimed a town in 1887, like Betoota, Birdsville was established to collect tolls from those who drove cattle, mainly from Queensland to the railhead at Maree in South Australia, at the end of the Birdsville Track. When Federation saw the end of inter-colony tolls the town declined. Before itwas gazetted, some of Australia’s most famous European explorers moved through the district, following the Diamantina River. Explorers included Sturt, Burke and Wills, Madigan and others. I had read their reports or, at least, many of the books about them.

Sure, my time in Birdsville was wonderful, but not really relaxing. There was plenty to eat and drink and it was wonderful to see Amber again. To hold her, touch her soft skin and smell her hair made the days of emptiness worthwhile. We laughed and smiled at each other again. I was sorry I made her cry as I took off my clothes. She told me I was very skinny and I felt her tears on my shoulder as she held me tight at night. Perhaps she was frightened by what she saw, not only my physical condition but my obsession and determination and commitment to continue. If she did not raise the question of our relationship, I knew I would not. So we kept silent on the future and held each other close in the present.

In the few days I was in town I met a number of locals. One morning I was feeding the camels on the western edge of town when a tour guide offered to show Amber and me a tree that had been blazed by Burke and Wills. These two had undertaken a journey through this country in 1860 and 1861 on the first crossing of Australia from Melbourne in the south to the Gulf of Carpentaria in the north – and back. The tree’s trunk was narrow and it looked to me like the blaze was dated from 1961. Whoever had scarred the tree forgot that Burke and Wills cut their trees with roman numerals. There was nothing fictional about the story of Burke and Wills though, and the pain, suffering and coincidence sat equally as a tragedy worthy of Shakespeare and as an important fragment of Australian history.

Robert O’Hara Burke and his second-in-command, William Wills, died in circumstances that bring tears to those who hear or read of the story for the first time; or for that matter, even those who read it more often. That they died was in part due to inexperience and a lack of knowledge of the people and country around them. Their deaths linger in the minds of so many Australians precisely because their deaths are testament to, and confirmation of, fear of a place that is unknown, threatening and unforgiving.

At least one reason to dispel uncertainty about what lay in Australia’s centre was driven by the quest for better and faster communications between Australia’s colonies and the rest of the world. From the First Fleet of English officers, convicts and settlers who departed England in 1787, communication came only by ship. The journey took six months, sometimes longer, and too often the ships did not arrive, lost on the rocks of Australia’s coastline or in the seas of the Roaring Forties. By 1860, though, plans were being made for a submarine telegraph cable linking Australia with India and the rest of the world. The question for decision makers in the Australian colonies was where the cable should land. Leaders in South Australia argued that it should be brought ashore on the northern coast, near the mouth of the Victoria River, and then cross the continent’s heart to Adelaide. In Victoria and New South Wales others argued that the line should be brought ashore at the Gulf of Carpentaria or Cape York and then south to Sydney and Melbourne.

In practical terms though, the centre of Australia had to be crossed before the line could be surveyed. The South Australian government offered a £2000 prize for the first expedition to cross from south to north. In Melbourne, the Royal Society of Victoria set up an Exploration Committee which raised £3000 and appointed Robert O’Hara Burke, Inspector of Mounted Police in the Goldfields, as leader of its expedition.

Burke’s expedition set off from Melbourne on 19 August 1860. There were 15 Europeans, 3 Indians to manage the 25 specially imported camels, 22 horses and more than 21 tons of stores and equipment. After arguing with most of those who accompanied him, including those who had far more experience of the inland, Burke appointed William Wills as his second in command. He then split his party and on 16 December set out from Cooper Creek, south of present day Birdsville, for the Gulf of Carpentaria, some 1200 kilometres to the north. Reaching the Gulf on 11 February 1861 the small party of four men, one horse and six camels turned to retrace their steps to the relative safety of Cooper Creek and the depot camp party they thought would be awaiting their return.

Before leaving Cooper Creek, Burke told the leader of the depot party that he was not to wait at the Cooper longer than 12 weeks. The leader, William Brahe, later told the committee of inquiry into the expedition that Burke had said to him, ‘If we are not back in three months, consider us dead.’ Though Brahe waited four months, Burke still did not return.

Despite the suffering he and his team endured, Burke, Wills and John King did return to the depot on the Cooper in the evening of 21 April. The same day, Brahe and his men had abandoned the camp, leaving a cache of food at the base of the famous ‘DIG tree’ on the northern bank of Bullah Bullah waterhole of Cooper Creek. Blazed on a branch by Brahe was the date of his departure and on the trunk:

DIG

3 FT NW

Burke recovered the cache and, overruling Wills and King, left a note in the tin outlining his intention to follow the creek to the south-west, believing he had no hope of catching up with the main party. He would take the two men 240 kilometres to a cattle station near Mount Hopeless. Having carefully filled in the hole, Burke failed to mark the tree or leave any indication he and his men had been there.

A little over two weeks later, while Burke, Wills and King were just 65 kilometres away, Brahe returned to the depot site in the hope that the party had returned. Seeing nothing to indicate Burke had done so he did not dig up the cache to check its contents and rode away.

Two months later Burke and Wills were dead. The sole survivor, John King, had been cared for by Aboriginal people and a relief party reached him in mid-September 1861. Edwin Welch, the relief party’s second in command, reported finding King. As he rode toward a group of Aboriginal men they retired: ‘leaving one solitary figure apparently covered in with some scarecrow rags and part of a hat, prominently alone on the sand. Before I could pull up, I had passed it, and as I passed it, it tottered, threw up its hands in the attitude of prayer, and fell on the sand.’

Thinking back on Burke and Wills I knew I had to take care. So for those few days in Birdsville there was much that had to be done. For me though, there was too much noise and movement. There were people to call and radio interviews to do. It was good to be on the track again, to sit before a small fire with brew in hand and camels contentedly chewing their cud.

I called in to see Warwick, the town policeman, in the station on the other side of the airstrip from the Birdsville Hotel. I outlined what I had planned. I said I had a mobile-sat phone and an emergency locator beacon. He took down the number of the phone and I assured him I would be checking with Amber in Canberra once a week. He also took Amber’s number, and then I showed him my proposed route and projected time of arrival at Dalhousie Springs.

Warwick leaned on the bench in the station and asked, ‘You got a rifle for them feral camels out there?’ I told him that I had, including the various State, Territory and National Parks permits. He grunted and said, ‘Probably won’t be seein’ ya again,’ which I took to mean that the planning I had done met with, if not approval, at least his tacit ‘okay.’ We shook hands.

Warwick was the last Queensland police officer I expected to deal with on my trip. Not once had I had any problems. On the contrary, every policeman I met was efficient and even friendly. They went out of their way to be helpful. Maybe they thought I was reasonable sort of person, or maybe they wanted me out of their hair as quickly as they were able. Probably both.

Camp 2

It was a gentle stroll to our camp, which included lots of camel browsing, next to a gravel borrow pit some 500 metres to the east of Nappanerica, local Aboriginal name for Big Red, the 40 metre dune that marked the eastern edge of the Simpson. From the gravel pit I filled another three jerry cans; water for the camels that they would drink on the crossing.

Earlier, just before we arrived at the gravel borrow pit, Selwyn Kirstenfelder pulled up in a large white Toyota. With its antennae and spotlights it looked a lot like a four-wheeled insect. The tray of the vehicle was full of welding gear, eskys of food and jerry cans of water. From the bullbar three beach fishing rod long antennae extended, still trembling minutes after he had stopped. He was working on some yards out at Hertzols Tank, near Eyre Creek, for David Brook, owner of cattle stations, part-owner of the Birdsville Hotel and mayor of one of Australia’s most remote towns. ‘Got to do it on me own. Can’t get blokes to come out and work for me,’ he said as his 50-year-old gnarled face creased into a frown.

I asked him why he worked in this country so far from towns and their pleasures. The corners of his mouth almost gave way to a smile and said that of all people I should understand.

Not far from the shallow borrow pit, I sat on my swag watching the camels feed and looked west to Big Red. I thought more about what lay ahead. The Simpson Desert is the driest region of the driest continent, other than Antarctica. Over an area of around 160,000 square kilometres, the desert’s temperatures rise over 50ºC in summer and drop to -5º. Over 1100 parallel red sand dunes roll across the desert, some up to 200 kilometres in length with heights between 10 and 40 metres. The dunes are aligned in a NNW/SSE direction, generally static with crests and sides continually shaped by the winds from the south. We would have to cross them all. On foot. Our task would be much harder from the eastern side, as the dunes are not symmetrical. The western slopes are a gentle 12 degrees while the eastern sides are at least double that. This explained why most people who attempt a crossing of the desert approach it from the west.

While Aboriginal people moved across this country for thousands of years, the first recorded desert crossing was in 1936 by Ted Colson, Peter Ains and five camels. Since that time the desert had been crossed by vehicle and other means, mostly from the west and the easier slopes, or from the north moving in the swales between the dunes. There had not been a recorded crossing of the Simpson Desert by a lone person walking east to west. Until me.

As a bird flew, we had 130 kilometres to Poeppel Corner and another 190 kilometres to Purnie Bore. Of course the distance was made a great deal longer having to scale and descend the dunes. On our crossing so much depended on the going, the availability of feed, and the presence of surface water. On this last I had heard many conflicting stories so I planned on there being none. We would carry eight jerry cans, each of 22 litres of water, with two litres on me, and food for up to seven weeks, to last us until the small settlement of Finke. But everything depended on the camels, especially Kabul and Chloe who carried the water. The brutal, simple fact was that if the camels did not make it, nor would I.

The diary lay open on my lap as I listened to dingos, their calls a low cry from the heart. Camel heads turned to the sound and the chewing of cud stopped for a moment. I looked down at the page to my thumb where grains were black under the nail and grains of desert were gently blown across my page.

Camp 3

How could I ever forget crossing Big Red and entering the red dunes? Red ridges were soft walls, like battlements blocking our passage from the horizon of the future and the past. For those who sought it, quiet eternity waited in places like these and my heart beat hollow with knowing that there was now no past or future, just now. I had brought us to a place where we could disappear, where the sun would dry our skins and the dingos crack and crunch at our bones. We were but blood and bone moving across a surface of sand. No time but desert time, of sun and dark, of hot and cold.

Sitting on the swag in camp I looked between my feet to the fine red sand and leaned back to suck in the air from a sky turned dark with the setting of the sun. All around was silence that seemed to belong to a different world, a world where worry and nervous haste were intruders and did not belong.

We camped three to four kilometres from Eyre Creek where the flies were so bad I had to scrape them from my eyes. I tried to brush them away but it was useless. I reached in to the corners of my eyes and with my thumb at the top of my nose I dragged my fingers across my lids and captured five or 10 flies in my palm. I presumed they had grown from maggots in the carcasses of kangaroo and cattle drawn to the creek. Before long my fingers were grey and bloody from the buzzing bodies and I scrubbed my hands in the sand.

In 1845, on a quest to find the inland sea that did not exist, Charles Sturt moved along Eyre Creek until at last, his men weak and his horses close to failing, he retreated south. The Simpson Desert had very nearly killed him and his men. His story was another reminder that it was a place to take great care.

Sturt, almost 50 years of age, set out from Adelaide on 10 August 1844 with 15 men, including John McDouall Stuart, the expedition draftsman, whose path I would cross again. The party also included a surgeon, stockman, bullock drivers and a sailor. The party took with them, among other things, a boat, bullock drays, horse carts, 200 sheep, two sheep dogs and four kangaroo dogs. Two months into the expedition Sturt wrote to a friend of his quest for an anticipated inland sea:

Tomorrow we start for the ranges and then for the waters – the strange waters on which boat never swam and over which flag never floated … We have the heart of the interior laid open to us, and shall be off with a flowing sheet in a few days.

He was very, very wrong. Later, having breached the desert ramparts, he wrote the land was ‘The most forbidding our eyes had ever wandered over’.

Sturt arrived home in Adelaide on 19 January 1846. He had been carried much of the way south in a cart, sick with scurvy and unable to walk until he had consumed some wild berries. Even so, Sturt wrote that, on crossing the threshold to his home, his wife saw him and collapsed. He then, ‘raised my wife from the floor on which she had fallen, and heard the carriage of my considerate friends roll rapidly away.’

Sturt never again went in search of the Inland Sea. Instead of water lapping on shores he found a sea of sand and a blinding sun that seared his sanity.

Our evening camp was not as good as I would have liked but I wanted to have the weight of saddles, water and food off the camels early. With tired, resigned sighs they dropped to the ground more often as the day wore on. Their weights were heavy and if I found the going desperately hard, for them it must have been doubly so. Kabul would drop first, followed by Chloe and Kashgar. It happened at the first dune after Big Red and four times later. I rationalised that their dropping might be because of the change in activity, going up and down the dunes, and to the weight they were carrying, which was more than they had carried before.

We approached each new dune with some trepidation. They were high; challenging and confronting. I tried to crab my way across the faces, zigzagging as we made our way to the top. The only sounds were panting, the creak of leather, a slosh of water and a quiet crunch as feet and pads moved across the sand’s thin surface crust.

Camels carried what I had planned. Kabul carried around 200 kilograms, 88 kilograms of water, most of the food, the mobile-sat phone, the rifle and the steel-framed winged saddle. Chloe carried around 120 kilograms, including water, spare rope, food and miscellaneous supplies like books and medical kits, camel and human. Kashgar’s load remained similar to that which she always carried; the swag, the camera and the food for the day.

Early that day the camels seemed almost fearful of being in the desert. Kabul’s nostrils flared and his whimpering gave away his uncertainty. Was it the dingo loping off over a dune or the scent of camels on the breeze? I was unsure, so I unzipped the rifle from its case and carried it over my shoulder. On arriving at camp I fired it twice, just to make sure. I paced out 100 metres, walked back and settled myself in the sand. I aimed for a small log on the face of the dune opposite. I fired and the round struck just a fraction low. I turned to watch the effect the sound had on the camels. They did not take fright and resumed chewing their cud as I watched. I took up the same position and fired again.

I remembered that camels and rifles did not always go well together. In 1846 John Horrocks, the first explorer in Australia to use a camel, was shot by one. As Horrocks was preparing his gun to shoot a bird, Harry the camel lurched and caused the weapon to discharge. The ramrod took off two fingers and ripped through Horrocks’ face, knocking out a row of teeth. A few weeks later he died of an infection caused by the accident. In his will Horrocks ordered that Harry be shot.

I wanted to do more than 25 kilometres a day as the crow flew. This was a lot, given the amount of climbing and descending we had to do. But I knew we had to keep moving. I felt that if I lost focus and drive I would vanish in the emptiness, that my soul would dissolve and my flesh and bones would be nothing but dust. But it was not only because I felt I could vanish in the emptiness, it was because of a fear inside me. It was a fear not only of failure to complete what I had set out to do, or even death. It was a fear of failing myself. This was because I wanted to exalt in my own dreams and it meant I would hurt myself. Was I up to it? Could I do it?

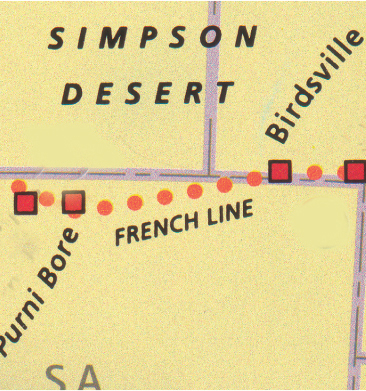

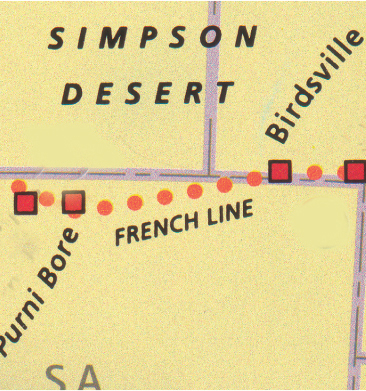

As I sat on my rolled-up swag, sipping coffee from my old Foreign Legion steel mug, with headlamp on my head, I reflected on the day and reminded myself why I was there. We had been close to the QAA Line, one of a number of tracks over the desert created by geological parties using seismic survey in the 1950s and 1960s. The QAA Line headed west till at a point north of Poeppel Corner it turned south onto another track and then became the French Line, the only east–west track across the Simpson Desert. I wanted to contact a person who could reassure Warwick that he need not send out a rescue party.

Camels and I had a Toyota pull up to us on the track. A tinted window slid down to release mint scented cool air. The air brushed my face and the driver spat at me, ‘You are a bloody idiot,’ and with a rigid finger to the desert, to the camels and me, concluded with a ‘What a waste of time.’ Before I could reply, or even ask if he would pass a message to Warwick, the window slid closed, the vehicle forced into gear and the diesel engine took him away.

In his vehicle, how could he see the value of what we were doing? The unanswered question was why did we get frissons of empathetic pleasure when we read about the ‘Worst Journey in the World’, go climbing, sailing or otherwise risk everything to achieve something that has no intrinsic value? Even without knowing the answers to these questions we recognise people who do these things are fascinating. Why do some people do these things without compulsion, without any exterior force being applied to them? Why do human beings go out of their way to push themselves beyond what is normally required of them by society, when society is at best ambivalent about the activity itself?

The answer was for me clear: because it is what makes us human. We look for challenges. I was sure the willingness to do this was in all of us, to a greater or lesser degree, hence the feelings of empathy and sharing in the fear and the cold and the hunger and the loneliness. Human beings are the only creatures to look beyond themselves. I believed it was what made us great and provided us with a remarkable ability to improvise, adapt and, ultimately, to survive.

For some reason this drive has been numbed in many of us, indeed actively discouraged in many people all over the world. Perhaps it is because people have become factors of production. Maybe this explained the little financial and social support we provide to poets, playwrights, performers and dreamers, those people who remind us that our lives, to be most economic and efficient, are regulated, managed, self-proscribed and, too often, directed by others.

I wanted to tell him, to cry out to the desert; there is value in passion, in touching the land and feeling a sunset touch your soul. But he was gone, and no matter what I said or did he would never hear me. I wanted to challenge him to look, and it became clear to me why I was in the desert. It was in seeking that I acknowledged my true self, a seeker of moments when my heart sang and my mind swam with colour.

As we camped on the western slope of a dune we were denied the sunrise until late in the morning. We were, however, blessed with sunrise on the facing dune, which described itself as a darkened line of shadow being pulled down into the sand to reveal a swathe of light. It was cold and as I left the swag I pulled on my woollen cap and curled the scarf around my neck. My lips were so dry I could feel the moist flesh inside wanting to split open the tight thin skin. The camels were just up and browsing.

Camp 4 Evening

I sat on the metal food box, the fire a long arm’s reach away, dinner warm in my belly. There was plenty of fuel in the swales between the dunes, where old stands of georgina gidgee had shed branches. In fact, across the Simpson Desert there was plenty of fuel among the pigweed and the flowers. I loved it here at night! There was probably no human being within 50 kilometres in any direction. The night was cold and the stars hard and brilliant in velvet dark. There is something profoundly elemental in being alone and self-sufficient.

The camels were tired. What a subdued trio they made after a few days hard work! Kashgar stopped prancing, Chloe continued to pointedly ignore me and Kabul manfully carried on. He sat down three times with a low groan and a sigh, Chloe only once. I unloaded the camels just after 6 p.m. and it was not until 8.30 that Chloe got to her feet and started to move around to graze. Both Kashgar and Kabul remained down and chewing. I knew these first few days had been hard on them so I watched them closely and checked them again for rubs and small hurts. If they were hurt I was finished here. I checked the bowline knots and the long ropes and left them to do camel things and think camel thoughts until the morning.

I watched Kabul, and the fleshy pink inside his nostrils as he tasted the desert air very closely as the days wore on. I reminded myself I needed to have the rifle handy in case we came across any bull camels. The distance between the dunes was only a few hundred metres and if I left it in its case I might not have enough time to bring it to bear, so I fixed up a sling for the rifle out of a spare length of rope and carried it on my shoulder.

Later in the evening, with a hot brew in my hand and the fire a whisper of embers, I turned on the radio to hear something completely unexpected. The last item of ABC’s PM reported on a pair of adventurers named Anderson and Gates from the University of Tasmania. According to the interviewer, the two were pulling a cart east to west across the Simpson Desert. They had made it across the fourth dune from Big Red and were complaining about ‘bush flies’ and a bent shaft on their cart. In the past they had arranged dinner parties underground and out-of-the-way-places to raise money for a scholarship fund. Good for them. Given the speed they suggested they were travelling, and their proposed time of arrival at Dalhousie Springs, I thought it likely we would meet.

Camels and I camped about 200 metres east of a wooden sign that marked the entrance to the Simpson Desert National Park, just at the bottom of the park’s first dune to the north side of the track. We did not arrive at Eyre Creek, a dry bed with a denser growth of bushes and trees on its banks, until after midday. This meant that we could not have gone far on the day of Big Red. So if the dune heights remained as they had been over the previous days, I calculated we might be able to make 20 kilometres a day. Not even that far perhaps. But then, it was hard, very hard work. No one had walked alone from east to west and I was fully aware of how difficult the challenge really was. My plan to reach Poeppel Corner in four to five days was entirely based on Kabul and Chloe, for they carried most of our gear, including all the water. I planned giving the camels their ration of 22 litres each when we got to what some people called simply the ‘The Corner’.

Sturt had something to say about what he named Eyre Creek. He wrote in his journal in September 1845: ‘the ridges extended northwards in parallel lines beyond the range of vision and appeared as if interminable. To the eastward and westward they succeeded each other like the waves of the sea. The sand was of a deep red colour, and the bright narrow line of it marked the top of the ridge, amidst the sickly pink and glaucus coloured vegetation around.’ As far as I could tell, Sturt was not far from the mark. I couldn’t help but think that his description was, in part at least, seen from a jaundiced eye – one that ached not for a sea of sand, but for an inland sea of water and prosperity.

As we descended one of the dunes that day, my body twisted and moved awkwardly through the sand. In so doing I strained my Achilles tendon, damaged while at university playing football. My right ankle became swollen so I tightened my boots further and took some aspirin as an anti-inflammatory.

Even without being hurt, going up a dune was painful. The skinny muscles in my thighs burned fire as I turned the outside of one boot to the sand, crabbing my way up its face. But there was little purchase; my feet were not camel pads that spread the weight across the surface. Instead I sank, ankle deep at times, into sand that seemed too reluctant to release me. Every single step up the face of a dune was tiring. If there were over one thousand dunes, and I took 30 or 40 or 50 or sometimes many more steps up the face of a dune, I would have to walk tens of thousands of paces up sand dunes. It was intimidating to contemplate. Worse still, it stretched my tendons and muscles so that sometimes I felt they were close to tearing. Like my sanity. So I broke the Simpson crossing into manageable parts that did less to frighten or intimidate me. From Birdsville to Eyre Creek. From Eyre Creek to the Corner, and so on. Sometimes, I even broke up a succession of dunes into a series of small victories as we crested each one.

I took short steps with Kabul close behind, his breath in my left ear as we worked our way up the dunes. At the crests we paused and savoured the gentle breeze that seemed to cool us a little and, for a moment, took the flies away. I had never seen Kabul’s sides heave as they did then, nor heard him suck in oxygen, great gulps, his lungs bellows. I told him that there were more dunes like these, many, many more and he seemed to understand and tremble a little, so I gently blew in his nostrils and spoke to him in smiling tones. His exhaustion worried me more than I could say, for I was nearly done and without him I was finished.

It was at the top of one dune, just west of Eyre Creek, that I stopped again. With my head bowed and hands on my knees I waited while the camels crested the dune and then stretched myself upright. It was a moment that made me catch my breath.

Kabul rested at the crest of the dune, his shadow in sharp relief against the terracotta red of the sand, its stippled surface clean, pristine and perfect. His shadow belonged to the desert. In the curve of the shadow of his neck grew white-petalled flowers. I knew no-one else would ever see them. The timeless shadow on an ancient canvas, coupled with the transient beauty of a flower, seemed to sum up life itself.

I looked to the west and the crests of hundreds of red dunes marking the progress of the ocean of sand. I turned to the east and there too were the crests of dunes, rolling waves never to break. Across the waves moved the shadows of clouds mating and parting. Surrounding me were colours, shapes, and time, lots of time, dense with life and a history of living.

My mouth was too dry to swallow. I took some of the sand at my feet and held it tight in my hand. The desert had me now. The land was reaching out to me, talking to me and wanting to claim me as part of itself.

Camp 5

Flowers, white, yellow and pale purple, made the walk seem like a stroll through a meadow. We camped on the western side of a dune among the flowers. I put the camels out on long leads and despite the day’s hard work they were up on their legs browsing noisily on the succulent green stuff all around. Later, as I lay in the swag, I could hear them rolling, farting and chewing their cud. Even from where I lay I could distinguish them by sound. Chloe had a hard-pitched, forceful chew. Kashgar’s was more mellifluous, gentle and musical. Kabul had a smooth, rhythmic approach to the cud, efficient, pragmatic and practical. There was no wasted energy in anything he did.

Kabul sat down three times in the course of the day. Chloe not once. I could never be angry with them, hurt, punch or scream at them. I loved all three. Using some camel psychology I unclipped the carabineer from Kabul’s saddle and walked Chloe and Kashgar around Kabul to the crest of the dune. Kabul whimpered as they passed and struggled to his feet under the weight of his load. Sometimes I felt like a bastard. I loved him so much and I did not want to hurt his heart but I knew we had to keep moving.

They were all still passing damp shit. As the rounded lumps fell to the red desert ground I squeezed one of the brown-green walnuts between my fingers. The plasticine dampness was testament to the wonderful season and the abundance of daisies, parakeelya and pigweed.

There was only one discordant note. We passed what would have been a beautiful campsite under a stand of georgina gidgee, the campfire coals still smouldering. Lying all around were onion peels, pumpkin, bread slices and wrapper, beer stubbies, smashed and whole, along with brown-stained toilet paper caught in the spinifex and blowing from the ground. I bent my head and set to cleaning the land. I burned the paper and other flammables. Anything that could not burn I put in my rubbish sack. The only thing I would leave behind were a few footprints, sweat, coals and a daily shit next to the fire. I wondered if my compatriots in their four-wheel drives had any idea what rubbish they left behind.

Later in the evening I heard the trolley men, Anderson and Gates, being interviewed. They said they were 15 kilometres east of Eyre Creek, about 60 kilometres from Birdsville. It seemed to me that were making little distance or maybe I did not hear them correctly. In any event they were having trouble with a main shaft on their vehicle. One person who passed me earlier in the day gave them a hand, adding ‘They don’t seem too well prepared to me.’ We would see. They hoped to be at Dalhousie Springs on 14 July, a fortnight from now, around the same time as me. They had a lot of catching up to do.

My Achilles tendon was worse. As I had done so often in the past, I took two aspirin in the evening. I had a lump along the tendon that was very hot and very tender. I knew I would have to elevate it in the swag and strap it up in the morning. We were doing too well to slow down now. According to my map, we were about 90 kilometres from Birdsville, and 60 kilometres from Big Red. This gave us around 70 kilometres to Poeppel Corner, roughly three or four days. Arrival depended on how the camels performed: it always did. Everything depended on them.

I looked at the map and the compass, across to the next dune crest, the next, the next and then to where the sun set. I wondered sometimes if I needed a map at all, but it was a way to measure things, to focus my mind in a place where eternity could dissolve your mind to the nothingness it really was. I also used the map to distract me from the pain of my body, the thing of flesh and bone that hurt when I moved, that pleaded for more food and cried out for rest.

Over those days the flies were so bad that when I glanced at my shadow on a dune there was not the sharply defined shape I had expected. Instead, the edges were blurred, an out-of-focus negative, from what seemed to be millions of flies buzzing around the camels and me. Where did all they come from?

In the evening’s bright moonlight I got up from the swag to check the camels. There was something about the air that wrapped itself around me. I looked to my feet and the carpet of snowflakes. All over the dunes, as far as I could see the petals of the flowers were open. While the air was cold, it was the clean and freshness of an early spring morning in a garden. And it was silent. It was a silence that gripped my throat with fear and wonder.

With 50 kilometres and our rate of travel, I estimated we would take over two more days to reach Poeppel Corner. It would be good to get the water off Chloe and give it to the camels. Both Chloe and Kabul seemed to be managing well, and I made sure there were plenty of stops for the yellow and white flowering succulents. Kashgar seemed to be more tucked up, with her sweat glands showing on her neck, and when I took her saddle and blankets off she was much damper than the other two. I wondered if it could it be due to her much finer wool.

By early evening I had them tethered and feeding on their own patch of shrub and bushes and an hour or so later heard Kabul nickering and pulling on his rope looking for the other two. Even though they were no more than 20 metres away, I got up from the fire and moved him nearer to his girls. He was boss camel, they were his harem, and he wanted them close.

That day Kabul dropped to the desert sand eight times. Though still fat, he seemed to tire, especially when he saw another dune coming. Though I could not blame him, he developed a smart, but to me very annoying habit. At the base of the dune he would move to pick at something, stop and then go to hoosh down. It did no good to my body to be twisted and I had to be ready to tug on his lead rope, to let him know I knew what he was planning.

Kabul’s procedure to hoosh down was different from that of Chloe and Kashgar. First, a pause and a blink of eyes as he appeared to collect his thoughts. He put both hind legs together and a drop onto his right foreleg with a whump, followed quickly with the left and a tuck in of rear legs. He sighed as he settled forward on his brisket and buried his forelegs into the sand.

Chloe gaped. Instead of methodically putting one foreleg to the ground like Kabul, she would fold both forelegs and thud to the ground, all her weight on her knees. Quick to follow was a brief jig as her hind legs were tucked in and a perfect settling on the brisket.

Kashgar was similar to Chloe in that she dropped to both knees, but instead of a gape she would give a little bellow of distress. When settled on her brisket she would let out a sigh, perhaps of resignation, a camel comment on the state of things.

We had seen dingos, only one rabbit and plenty of camel sign. For the first time I wore the fly veil. I was prepared to suffer a little more heat, as the mesh slowed the movement of air, than the onslaught of the flies. I was tired of squeezing them from the corners of my eyes, or having climbed another dune and breathing deeply, having to expel them from up my nose where they struggled in the mucus or from my throat when I gagged. The black buzzing spots were everywhere.

Camp 7

We walked another 20 kilometres. We even passed a salt lake to the south, white glass reflecting the light. The dunes were getting more broken up, rather than consistently longitudinal across our path. All these elements indicated we were getting close to the point where we would turn south along the shore of a dry salt lake to Poeppel Corner. This I expected after lunch the next day.

Late in the day, just before we camped, we passed some four-wheel drivers setting up camp. I watched from a distance as the four tents were set up in a square, all facing inward, the vehicles stationed on the outside of the square, each just beyond its tent. One fellow stood at the entrance of his tent, stretched out his arms and said ‘Ah, home sweet home.’

I stood on the summit of a far dune, watching. My hand scratched Kabul’s favourite spot behind his ear and the other camels took advantage of the pause to browse. I wondered at the point of being out here if you did not embrace it. Did people congregate because they felt nervous about the ‘emptiness’ of the desert? Why did they feel that it was better to have the desert outside the tent and their world on the inside? Is not being in the desert wanting to be part of what the desert is? We did not stop to introduce ourselves.

Late that same night I watched camel ears prick and faces turn to the west. In the distance I heard the chug of a struggling vehicle. I thought something must have been wrong and I walked the few hundred metres to the track with a torch and an offer to help, if help was needed. None was. It was a red dust face in a Toyota doing food and water drops for a Japanese guy attempting to walk the French Line from west to east and Birdsville. Apparently the walker and I would meet on the track in a few days.

I went back to the fire and reflected on others in the desert. Anderson and Gates had problems. They had yet to reach Eyre Creek, and as one chap described it today, ‘There was stuff and jerry cans all over the dune as they pushed and pulled the wagon up it.’ Not good. Apparently the axle was shorter than the axle width of a four-wheel drive, which meant their wheels could not run in the ruts of the QAA Line, like so many others of the tracks across the Simpson, the remnant of a seismic line.

I wondered if I had planned well enough. As we were descending dunes my mind kept resting on what would happen if I slipped or if Kabul did. I could so easily break a leg or be crushed under three rushing camels. Holding his headstall with my left hand I tried to walk Kabul slowly down the dunes. If there was a rush I believed I could either keep up with him or turn him in a circle. Of course, I had thought that outside Birdsville and I had been wrong.

A reminder of my vulnerability came when I was between Chloe and Kabul, tightening Kabul’s girth strap. Both Chloe and Kabul moved closer. For a moment my head was almost trapped between the two lateral bars of the winged saddles, and I had a vision of my head crushed like a melon.

Camp 8

I was getting skinnier and the cold worried and bit at me like an angry dog. The dry air and the cold made my skin want to crack and split. When it did, moisture from my body collected dust and flies. We camped approximately four kilometres short of Poeppel Corner in a beautiful meadow, a camel heaven.

For much of the day we walked south along the western edge of the salt lake. Oddly enough seeing my shadow falling in front of me, and having the lake to my left, reminded one of a walk I did in November and December 1992, north along the eastern shore of Loch Lomond in Scotland, when on leave from the Foreign Legion.

As I had planned, at the end of the day I gave the camels all the water they wanted to drink. Predictably Kabul drank most, then Chloe and Kashgar. There was more than a jerry can and a half left of the camels’ water, and I decided to present it to them in the morning.

Camp 9

It was getting colder, much colder. The cold bit my ears with what felt like fire and my forehead ached. I thought it must be due to the fact we camped so close to the salt pan. My breath froze on the underside of the swag and light dew froze on the face of the desert flowers, diamonds for a moment as the sun rose above the horizon.

Later in the morning, only a few kilometres from our camp, we made it to Poeppel Corner where a plaque on a wooden post read:

This red gum replica of survey corner post was presented by Friends of the Simpson Desert 4 July 1989. Original erected 1880 by Surveyor Augustus Poeppel. Fallen post recovered 1962 by Dr Reg Sprigg AO, held History Trust, Adelaide.

Along with Big Red in the east, and Purnie Bore on the desert’s western edge, Poeppel Corner was probably the most widely known landmark in the Simpson Desert. It marked the point at which the borders of South Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory met. In 1880 surveyor Augustus Poeppel located the South Australian and Queensland border from Haddon Corner, the northeasterly corner of South Australia, to Poeppel Corner. Just a year later it was found that the chain he used to mark the border had lengthened by an inch through use and wear. It meant that the survey work had to be redone. In 1884 the corner post was reached by surveyor Lawrence Wells who calculated that it was 315 metres too far west in the bed of Lake Poeppel itself. The post was moved out of the lake bed to its correct position on the eastern edge of Lake Poeppel.

We arrived at Poeppel Corner near 11.30, or at 11, South Australian time. I took some photos and we moved across the salt of Lake Poeppel where our shadows trailed behind us and onto the French Line. We soon came across fresh camel sign. There, in the middle of the track a number of camels had settled for the night. I counted four discrete piles of dung. By the length of the impression in the sand, of forelegs and the end of hind legs, at least two were much, much bigger than Kabul. The spheres of dung were rounded walnuts and still soft. Camel urine still stained the red sand and was of great interest to Kabul and the others who sniffed and nuzzled the damp dust. As for me, I gripped the rifle tighter.

Before I hit the swag I forced myself to have another weak brew of coffee. As I sat on the feed tin tipping the fluid into my body to make my cells swell, I reflected on the quietness of the desert. Where were the night birds and the crickets? If I listened carefully I could hear the crackling and sighs of the fire, water against the side of the billy sizzling, and the digestive vegetable murmurings and burblings of Kashgar and Kabul close at hand.

Chloe was a little further away. As the birth of her calf drew nearer she seemed to be getting crankier, more inclined to curl her lip at me and even hiss with displeasure. I even caught her moving her body preparing to kick me with a hind leg. Camel training taught me that a kick from a camel was not something to be taken lightly. I could be winded if I was lucky. Anything else I would have to manage as best I could. What to do if Chloe calved while we were in the desert? It seemed that we did not have time to stop while the calf grew strong enough to accompany us. I again told myself I would worry about that when it happened.

When all the camels were out on long lines, browsing, burping, rolling and farting, I went for a short walk, just a few metres away over the crest of a dune, and sat down. I felt the warmth of the sand wrap itself around my now bony backside as I settled into the land. I let gravity take the heels of my boots into the sand and the grains stuck to what little moisture remained on my hands. Just then it was easy to imagine the land opening up and taking me to its heart. For a breath or two I even expected it.

To the west the sharp dune crest darkly underscored the glowing sky and above a planet was the first of many pinpricks of light to illuminate the velvet darkness. Just below my feet was a yellow petalled flower. Looking at it for a moment I thought again of Amber. It seemed that I did not have much to offer her except a beautiful treasure such as this. Apart from the things I learned and kept close in my heart, it was the only thing I took from the desert to give her. Not much, a worthless thing to many people, but so very precious to me.

Camp 10

The cold breeze sucked the moisture from my skin and because the sky did not clear it made the morning seem to drag and be oppressive. One benefit was that there were very few flies. From the time I gave the camels their water Kabul had not once sat down. Chloe was getting so touchy she would hiss and gape when I approached to do up her girth strap, or even tighten it while she was standing. Her udder had swollen to extraordinary proportions, an inflated rubber glove with veins.

A rest on the crest of a dune – a timeless shadow on ancient canvas.

There was plenty of good feed along the way, and in the afternoon as the sky cleared delightful red-beaked finches. Sometimes alone, in pairs or in flocks, they made a wave of colour when swooping and wheeling in amongst the green and the yellow, white and purple flowers of the desert. It was a special day.

On the radio that night I heard that Anderson and Gates were ‘about 70 kilometres east of Poeppel Corner’. If that was right they had done about 60 kilometres from Big Red, or an average of less than nine kilometres per day. I hoped they could pick things up and move along a little quicker. But at the speed they were going I did not think it possible they would be able to finish when they had planned, if at all. I wondered what they were thinking, knowing that their plans were unlikely to succeed.

We came to another inscription. This time at the turnoff to the Approdinna Attora Knolls. A plaque was set between two star pickets, the inscription made out in strips of metal. It said:

Surveyor and explorer David Lindsay passed this point 11-1-1886 while on a traverse from Dalhousie Station SA to the Queensland border [and here a strip had been removed] Simpson Desert by a white man. Erected 5.8.72. WSA.

Lindsay had set out in 1885 from the Finke River and crossed here on the way to the Queensland border. Along the way he visited and recorded nine Aboriginal wells. Believing the country east of the Northern Territory/Queensland border to be discovered he returned to the Finke, skirting the western edge of the desert, and then headed north-east to Lake Nash and finally to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Camp 11

The day was dark and sometimes very cool. In the late afternoon it began to drizzle a fine mist and as I set up camp it rained. Still, I had no trouble starting the fire and as I sat looking into the flames I thought over the previous days. I had an extraordinary feeling that time was collapsing, folding in on itself so that days seemed lost. There were no physical reference points against which we could measure movement, except the dunes that in their physical effect on me were the same and they went on and on to the west. I imagined people going quite mad where there were so few reference points except the self. As I sat with the mug warming my hands I could believe solitude was the closest thing to eternity. Maybe it was little wonder that people cluttered their lives with irrelevance to keep the reality of that knowledge at bay. I wondered what people thought before they died. Was it a welcome or a screaming white knowing that life had been wasted?

I looked into the sky and did not want to speak out loud. The entire desert was a sacred place, so in low tones I whispered secrets to the camels.

Camp 12

The morning dawned fluorescent orange and blue, bright and clear, with not a cloud in the sky. We walked a day full of sunshine, but for some reason my spirits did not lift. I felt flat, without energy, sore and my hurt tendon was swollen. I had begun to dream about food. I dreamed of greasy T-bones with heaps of salad, tomatoes and lettuce, oranges and apples. My muscles seemed to be melting or dissolving from my body and the saddles were getting harder to lift. In fact, everything seemed to be getting harder.

I supposed we had to be about halfway through the journey, though it still did not seem that the end I had planned was possible or even likely. There was uncertainty in every day, about the camels and the land, along with a dose of pain that was tempered by hope and wonder.

It came as a complete surprise then that, just as we rejoined the track, we met the Land Rover Australia Club. Around 30 vehicles full of people were driving along the French Line. I was adjusting Kabul’s saddle, as his blankets had ridden up his shoulder which often happened as he descended a dune, when the first five of the Land Rovers zoomed by. They did not slow, not even a wave and they disappeared. Kabul was up and down until there was a break in the traffic. And I thought it was courtesy to slow down near a working animal. But these people had no interest in camels or the land other than the sport it provided for their vehicles.

A highlight of that day was meeting John Thompson, a ‘shooter’ or seismic worker with the Compagnie Geńeŕale de Geógraphie (CGG) in 1963. He was part of the team that created the seismic line, now called the French Line, so named because the company that created the line was French. He thought it was great work. He started early in the mornings and only worked till 2 p.m. every day, when he and the others could take time off from work and walk in the desert.

The Land Rover people stood about on the crests of dunes cheering each other over the summits. My heart sank and a part of me was very depressed. I thought the desert was the point. These people did not appear to bring an appreciation or a willingness to embrace the environment around them. Just noise, in their shallow cheers, the changing of gears and the racing of engines.

Later we met two vehicles parked off the track, tail gates down with women preparing lunch. The vehicles bore the number plates of Canberra, my home town. I watched a man descended from the crest of a dune with a loose end of toilet paper in one hand, a flapping fanion. Green-snot kids were walking around in bare feet. One of the adults was wearing an Australian football club jacket and took it off to reveal the club shirt, as if his identity was such an intangible thing he had to wear it or lose it in the desert.

One of the women called me over to a cup of tea, which was kind, but I swore off saying that the Land Rover people had held me up, and imagined that the bloke with the toilet paper would want to shake my hand, without washing his first. I needed to escape the suburban in the desert.

I supposed that seeing all these people depressed me because it meant that anyone could get out into the desert. Yet no one had earned the privilege of being there. Nothing was difficult. All was quite banal. All you needed was a four-wheel drive and some time. After all, was I not the strange one wanting to do it the ‘hard way’? Was it really a stunt, when all I wanted was to touch the elementary in the country and in myself?

I had thought that it was important to earn the right to special knowledge, knowledge that can only come from experience, pain, long suffering and the exposure to fear. While it might have been important once, it was irrelevant now. You can pay to get to the summit of Everest or even a trip into space. What once had taken years of effort required a different knowledge now; a focus on the dollar or the yen or the pound or the rouble. Every experience has its price. While I did not like it, perhaps it had its benefits, like exposing more people to the land or the sea or the sky – with the effect that more people might act to protect and preserve these special places.

I hoped that the following day we would meet the Japanese guy. I wanted to ask how he felt being in this beautiful exhilarating place. How was it that I had more in common with a Japanese guy than people from home? I was sure that it had more to do with what was in our hearts than where we lived. I would offer to build a campfire and make him a brew.

Later that night, I lay in the cocoon of the swag in that place between the dunes where the crowns of old, gnarled and very tough and enduring trees kissed. The sound of their embraces in the breeze lulled me to sleep.

A wind from the north meant that dust got into everything; my ears, eyes, nose, brew and my food. It was 30 to 40 knots which meant a very gritty brew and, I supposed, more roughage in my diet. Even brushing my teeth felt like stripping enamel with a wire brush.

I gave the camels the last of the water. Kashgar wanted only a few drops though Kabul took up more than 10 litres. I thought this should see them through to Purnie Bore. Laying out the map on the desert sand I could see nothing but the brown of desert scratched by the darker brown of the dunes. I remembered researching the route across the Desert and finding Aboriginal wells marked on old maps. Places called Mirranponga, Poolaburda and Walperracanna, used by the Wangkangurru people. They were not marked on these more recent maps and I wondered if they had been lost or whether they were being protected from football jumpers and their four-wheel drives.

On the map there were no points of reference, no rivers, hills, powerlines or lakes. The map was like the land itself, just shape and colour.

Camp 13

Taking 20 minutes or so to set up the mobile sat phone, I rang Amber in the morning and how wonderful it was to hear her voice!

After we spoke I sat on the sand for a moment thinking of the emptiness around me in the absence of her voice. I felt the hollowness of being alone and we finally left camp about 10.30. The day was very overcast with another strong wind from the north. This meant that the temperature was up and when not on dune crests we were plagued by flies. Even after we camped and after 9 p.m. I was still in my T-shirt, flies buzzing about my ears.

The camels and I walked to the track in the hope of meeting the Japanese walker. In the distance I saw a movement and sun reflected, then more clearly two aluminium poles above his shoulders supporting a pack that seemed so much bigger than him. I tied the camels off to trees and walked on to the track.

When he was perhaps two seconds from a handshake away I put my heels together, my arms by my side and straightened my back. I bowed, a slight inclination of my head. I said ‘Konichiwa,’ and he stopped for a moment in a mirror of me, smiled and said the same.

Kenji told me he was 27, from Hiroshima, and lived only five minutes walk from the Peace Park, dedicated to the memory of so many people of the first city to endure, on 6 August 1945, a nuclear attack. He was a teacher in a cramming school for primary school kids from 4 p.m. to 9 p.m. He worked, he told me, to fund his trips away from Japan which had become too crowded, too busy and too noisy.

While the camels looked on we shook hands and I offered to make a cup of tea. We talked about walking, tourists and Aboriginal people. Kenji told me he walked the Tanami Track a few years ago and was distressed by the racism of the many tourists he passed and of the compatriots he met in Alice Springs or Cairns. I liked him very much. I showed him the mobile sat phone – he was so slight he found it difficult to lift – the saddles, and I formally introduced him to each camel. Then I collected some twigs and put together the makings of a brew.

When it came time to say goodbye we shook hands with red grit hands and grit in our eyes. We parted at last and waved to one another on the distant dune crests, he heading east, me west. It was an odd meeting and one I treasured. He at least knew why he wanted to be here, to taste the solitude and the dust.

That night was almost a full moon. Did that explain why there were so many flies? The elevated temperature meant that getting into the swag did not mean comfort. I was gritty, sweaty and very greasy. My hair was matted and my feet far too fragrant. Even so, I did not stop shaving and brushing my teeth every morning. I simply left a little water in the billy, the rest going into my brew mug and inside me. I did not really need that much water for a shave. Once done I applied sunscreen, especially on my right side, where the sun shone in the north. The routine was good, it made me feel a little clean at least, and I never liked mossy teeth.

Camp 14

During the night the direction of the wind changed. It swung from the north around to the west-south-west. The change brought with it a drop in temperature and a beautiful morning, at least for a while devoid of flies. The air was crisp, fresh and new.

We were under way well before 8 a.m. I took great care with the saddling of Kabul and later in the morning took great pains to ensure his girth strap was tight. The daily examination revealed that while some wool had been rubbed off a small area of his shoulder, my attention meant it would probably not deteriorate. I was sure that much of the problem could be avoided once we were away from the dunes and the inevitable forward pressure of the pad on his shoulder as we descended the western face of the dunes.

Late in the day I stripped off my clothes and wearing boots only aired my body and felt my skin warmed by the sun’s last rays. Certainly my body was losing muscle. But more than that, I felt I was wasting away. Skin was tight across hip bones and my knees stood out from the leanness of my thighs that carried so little curve of muscle. Everything was an effort but I knew that a drive inside me would keep me going. It would keep me going west to the setting sun, but I knew it would get harder and harder.

It was a good day’s walk. The desert was changing as it always did. There were fewer dunes that had single crests. Instead, the dunes had become crowded with many summits. This meant that we walked switchbacks that ran across the face of the dunes rather than directly over the top, making climbing the dunes a little slower but much easier. All camels were still fat and as always we spent the first couple of hours strolling along feeding, with me seeking out the green yellow flowering succulents to put into Kabul’s mouth, the others sampling the smorgasbord the country had to offer.

Camp 15

We must have camped about 18 kilometres short of the Colson Track, as the crow flew, as we did not reach its intersection with the French Line until 3.30 in the afternoon. In the morning I decided to collect samples of all the plants the camels ate during the course of the day. In all, I collected 13 different types of plant – eight from the campsite and five on the march. It was obvious there was a great diversity of feed in the desert in a good year, when there were few rabbits. I wondered how often in the last two hundred years of white occupation of Australia the welcome conjunction had arrived. I had no doubt it was infrequent.

A woman and her husband pulled up early in the day. As the passenger window glided down, out came the nose of a large video camera, the large matte black snout of a Cyclops. Kay said it must be a wonderful way to relax, to take it easy and be away from the city. I was taken aback. I told her a little of my background and said that physically and emotionally this was a very, very trying enterprise. I tried to relate it to her by asking her if she had ever bush-walked (no, she had not), ever gone on a solo trip overseas (no she had not), ever been in the army (no she had not). I realised there was no way I could relate my experience to her other than the usual statement of fact. There was no shared experience that could provide the basis for a discussion. As I had to do so often I simply recited facts, saddling hundreds of kilograms, unsaddling, walking, fear of being stomped or trampled and then have the camels escape, finding water, a good camp, the right route and the list went on. She thought it would be pleasant. I put it differently, hard work, pain and tiredness, with moments of pure joy and exhilaration.

We camped about three to five kilometres past the Colson Track intersection. As we pulled up late in the day the sky became very dark, with the threat of rain in the distance, and wind that had turned cold from the south.

The following morning they came as I always knew they would. Camels lived and roamed, lusted and bred in the Simpson Desert and I knew we would meet some. I knew too that when we did it would mean a test. I wrote the following sitting on my swag, just before we moved off again, heading west:

My hands cup warmth, sweet caffeine on tongue and a lick of heat on my cheek. I hunker in the sun burnt desert dust savouring the embers of the morning fire and the sizzle of water in the billy. My back to the Antarctic breeze, an invisible standing wave that carves itself between the red waves that rise up to greet the blue, suspended and never to crash. The desert shrubs and flowers are brittle in the chill morning light. We are alone in the bowl of sand – three camels, Kabul, Chloe and Kashgar, the desert and my thoughts.

I turn to Chloe and Kashgar. They stand and watch at attention, their reassuring rhythmic mellifluous grind no longer. Their eyes are bright and their ears are rigid. I turn to Kabul, my dusky woollen companion, my friend, my lead.

The sun is behind the anchor tree and around Kabul leaves dance dark shadows in the stippled sand. The line of his lead rope hums under tension, its shadow a dark arrow to the south. His small hippo ears unmoving, slit nostrils flaring black and red as he tastes his future. His wet brown eyes are shiny with anticipation. Poll glands behind his head oozing, rancid, black and sticky, like the foreboding in my belly.

200 metres. They come from the cold where the south wind blows.

I feel the fear take form again, a dark wet reptile causing my belly to spasm and my throat to tighten. Not so much fear of what lies ahead, but rather, fear that I will not be able to do what has to be done. Fear I might discover the person I believe myself to be is a fiction.

180 metres. Brew mug hits the desert with a subdued metal kiss. I reach for the zippered plastic sheath and the rifle of steel and wood inside. I unsheathe it from its home and feel the cool contact of the barrel, the oily touch of the wooden butt and stock. ‘Made in Australia 1943’ it says. It is a good rifle, proven and true. I am a servant who must obey its rules to make it work. Rules allow me to kill if I wish. It was made to kill men in another place, another time. I feel for the magazine in the rifle’s belly. I take it off and check the clutch of golden brass cylinders nestled inside. I press my thumb against the rounds and feel the tension of the spring.

I genuflect in the dust. At my left Kabul is a handshake away. He shuffles his hind legs, spreads them apart and pisses on his tail. His tail slaps wet on his back. Some of the golden piss a benediction on my head.

150 metres. They are coming at us now; two of them. They have seen us. The air so recently filled with the cool of the icy south and fragrance of flowers is now made denser, thicker with the rich sweet, pungency of animals searching for a mate. They see our camp and are working their way in to investigate. They see the females, Chloe and Kashgar, and the bulls begin to trot. Slack lipped, foamed spittle and eyes bright with lust.

Need to concentrate. Need to shoot. Rounds are in the magazine and on the weapon. Just need to cock the weapon and push one of the brass cylinders from the clutch and introduce it into the chamber. Left handed this is not easy. Butt of the rifle goes to my belly, left hand on stock while right hand grasps rounded cocking handle and cocks the weapon. Do it. But the round won’t lock in the chamber. I can still see part of the round. The chamber remains partly open, the gold winking at me, a witness to my failure.

Come on. Come on. Something is wrong. Magazine off. Check the weapon. Put a round in the chamber by hand and work the bolt forward.

100 metres. Still won’t lock. Panic at my shoulder. Nothing works. They are coming to kill.

I can still escape. There is time enough to run. The warm dune summit, alive with gold, white, green and red of the winter is a saviour. No one will know I ran. I can lie on my back and feel the sun kiss my face, the perfume of desert blooms a balm. They want Kashgar and Chloe, not me. They would not chase me there. A part of me is screaming to escape the inevitable rolling eyes and lolling tongue. Panic whispers temptation in my ear – no one will ever know my weakness. But I need the intensity of reality. I ache for it. I need to know that whatever drives me does not also make me weak. I try again.

Don’t move. Snap the bolt into place. No good. No good. Something still wrong. Magazine off, uncock the weapon. Put a round in the chamber manually and work the bolt forward. Still won’t work. The dark reptile in my throat fatter and starting to pulse with strength.

50 metres. Come on. Come on. Butt, belly, stock, cock. Take out the round. Take out the bolt. Seems fine. Blow into the chamber. It’s clean. Look into the barrel. It is clear. Reassemble the weapon. And I see it. The head of the bolt isn’t wound entirely in. I screw it in, the lathed metal fitting neatly, snugly with itself. Slide the bolt into the rifle. The big bull now roaring and burbling. Magazine in the weapon. Butt, belly, stock, cock. The lathed metal of the cocking handle is locked all the way forward. The round is chambered and the firing pin set. Now to my shoulder. Now the safety catch off.

The big bull is running now, head down, his dulaa a wet pink obscenity hanging from his mouth. A pink chewing gum bubble blown from the corner of his mouth, opalescent with vivid capillaries and marbled with his spittle. The hump on his back is a wobbling woollen dorsal fin, lolling from one side to another. He comes at Melbourne Cup pace, so that I can see the river pebble smooth darkness of his feet and the spurts of dust, exclamations against the sand.

20 metres. Calm now. Breathe deep.

The charging golden chest fills my mind and the foresight blade of the rifle is lost in the shadows of his chest as his muscles move and tense to drive him forward. The drumming of pads at one with the pulse pounding in my ears.

Fire. A Rorschach blot florid on his chest. His legs fold beneath him and he meets the desert, half a cricket pitch away. In the silence that follows the round I feel the air tremble on my skin.

Butt, belly, stock, cock and to the shoulder. Now the camel screams. White teeth, canines to rip and blood-red throat. It bellows. The second circles and I squeeze the trigger’s 1.3 kilograms of tension and I will the bullet to his heart. But miss. Knocked to the ground he flails, the dark of his pads circling in the air, exposed the sun. The fat-filled woollen hump stops him from rolling over.

Butt, belly, stock, cock and to the shoulder. They are both on their feet. Charging away from me, their blood drips to the ground which drinks it up. Over the lip of the dune they are gone, my last sight of them the flick of a tail. Gone, galloping east along the French Line.

I grab my water bottle and give chase following the thread of dark red life. I follow for at least five kilometres and find traces of bright red arterial blood, bright and shiny against the terracotta grains of sand. But the camels keep on moving and I realise I have to go back to my own camp, my own camels and my own dreams. I give up the chase because I cannot leave my camels, Kabul, Chloe and Kashgar, alone any longer. To the embers, the swag and caffeine on tongue.

Back at the camp, all three are hooshed down chewing the cud. Lips and tongues and teeth working pulped green desert leaves. I hunker down to where the big camel dropped, just 10 paces from Kabul. All that remains is a blur in the sand and a smudge of darker red. The earth does not remember life, death or fear. It endures.

To my right, not far apart, lie two brass shells, golden exclamations nestled in the dust. I reach for them, the smooth surfaces, warm from the sun against my fingertips. In the palm of my hand they move together, their long bodies, tapered shoulders and dark interiors the abandoned carapaces of golden butterflies. I put them in my pocket, their firmness against my thigh a reminder of transformations.

Evening. As the sun rose higher into the day, climbing above the eastern dunes, it began to suck the colours from the land again and the cool and the moisture from the air. In single file I led Kabul, Chloe and Kashgar at a slow walk out of the desert’s amphitheatre, and climbed to the ridge of the western dune, for a moment a little closer to the darker blue and the sun. I looked to the east and the western facing dune where the sand turned to rippled bloody scabs. With us the creak of saddle leather, and slap and slosh of water in jerry-cans. Everything we need we have, water, food, shelter and shared experience of fear and the knowledge that we can survive. We needed nothing more.

Though both animals had been hit they were able to move rapidly away. This could have been due to my poor shooting, though more probably to the military rounds I used. I had no doubt that having been hit with a .303 round they would not survive long. To defend myself against bull camels with anything less would be irresponsible and might see an animal survive for too long in agony.

I was relatively well prepared. If I had not had a rifle Kabul would have been injured at best, or at worst even killed. Possibly the same with Chloe and Kashgar. Sure I should have used soft points that cause massive trauma, for there were no Laws of War here. It was the rule of the land. If you lived with it and were prepared, you might survive. We had been lucky.

Camp 16

We camped and I used a little of the water for other than drinking or cooking. I dampened sandpaper skin and scrubbed with a soon dark stained towel for a delicious wash. I think we did about 20 kilometres. This meant we had some 20 kilometres until the road to Purnie Bore became surfaced and from there another 29 kilometres. In total 47 kilometres to go till we reached Purnie Bore. It did not seem far, but a lot could happen in two days or so.

It was a cold night and it sucked the warmth from my hands and from my breath. It was a good night to have a sleeping bag inside a bivvy bag.

Camp 17

It was so cold this morning my ears ached and my cheeks were numbed. At first light I heard a bull camel roar and saw Kashgar and Chloe tremble. Again Kabul was rigid and tense, his ears swivelling to catch the source of the sound and his nostrils flaring to catch a scent. I reached for the rifle, my heart pounding hollow in my chest. During the night I had woken up to piss and put a log on the fire. Perhaps the fire kept the feral bull away and I never saw him.

Before I had finished packing up the camp I looked west to a dune where my eye caught a movement. For a moment I thought it was a cat, but it was too skinny and its tail too long. Just fur and dirty red. A fox.

It warmed up enough to take off my overshirt before midday, even though the breeze was from the south which kept the temperature down and the flies at bay. In mid-afternoon we crossed a dune and there was the intersection with the Rig Road, a hard topped track winding away to the south-east. The French Line heading west looked firm, as though it had been graded and surfaced with clay. It meant that we could move across the land a great deal faster – even though I slowed to allow the camels to browse on the abundant feed.

Just before we moved off in the morning, a four-wheel drive crunched down its gears and stopped. The driver descended, walked over to me and shook my hand. ‘I’ve been hearing about you for a while. It‘s amazing what you are doing and I wish I were with you.’ Then he looked into the fire. From his vehicle came a cry, ‘Don’t leave me alone!’ He turned to the vehicle and then back to me. ‘My wife,’ he said.

I looked to the vehicle and a woman put her head from the passenger window. The newcomer said, ‘It’s okay, come out over here by the fire.’ But she was not so sure. ‘I can’t. I’ll get dirty and there are animals too. Can you come and get me?’

He sighed, walked back to the vehicle and opened the door. She stepped out in a gleaming white shell suit, shiny new white trainers and bleached white hair. The two of them walked over to me and the fire. I shook her moisture cream hand and told them both about the trip. I also told her not to get too close to the embers or her shell suit would melt. With a sharp intake of breath she moved away slightly and trod in something. ‘Er, what’s this?’ she asked.

It was the morning shit I should have buried a little deeper. ‘Last night’s leftovers,’ I said, and she scuttled back to the vehicle. Her husband grimaced, shook my hand again and wished me luck. As I watched them go I wondered why she had come to this special place, a place I felt was a privilege to be earned through effort and a willingness to be touched by its wonder. Maybe I was kidding myself but I knew we valued things that are hard won. It was too easy to come here now.

The map told me that it was another 25 kilometres or so to Purnie Bore. The radio told me that the cart pullers would arrive at Poeppel Corner the next day or the day after. According to people who had seen them, they were very happy. They only needed more tobacco. There was no way they could complete what they had set out to do, and I felt a little sorry for them.

Camp 18

We did it! Purnie Bore at 4.00 p.m. The first recorded solo east–west crossing on foot of the Simpson Desert. Cresting the dune I was greeted by a forest of antennae topped with orange or red pennants. To sporadic cries of ‘Ooh, get ya camera,’ we descended to the camping area of Purnie Bore.

To our left was the green drum of the water storage for the shower and the plumes of vapour from the bore, which at first I thought was a large camp fire. There were more than 30 people and nearly as many questions: ‘Where have you come from?’ ‘Where are you going?’ ‘How far do you do in a day?’

We left the camping area, crossed a dune and took photos with the camels. I unloaded my friends and walked them down to the so-called ‘cool pool’, where the temperature was such that you could put your hand in the water for a drink. I was interested to see how my friends might deal with the water. Surprisingly, they took up little more than they would in a normal drink. Once, twice and that was enough. I waited for a few minutes but they seemed uninterested, so I long-tethered them around the camp. Once they were settled in, I had a cold shower. To get myself warm again, I put together a fire and had a ritual burning of my socks, rigid with sweat, grease and desert dust.

What remarkable camels. They appeared not at all distressed by the 16 days from Birdsville. Of the 66 litres they carried for their own consumption, Kabul drank 35, Chloe 22 and Kashgar only 9 litres! It was a reflection of the amount of work demanded of each animal and a testament to the wonderful season in the desert. I was sure Kashgar was getting even fatter!

Camp 18 Morning

I wrote up my diary snuggled deep in my sleeping bag in the swag. There was a frost on everything and the sky was achingly blue.

The towel I used the night before was rigid, frozen stiff on a branch close by. I supposed much of the frost could be put down to the mist produced by the bore where the water temperature exceeded 80 °C. The camels were blowing vapour like woolly dragons.

I went for a short walk and looked at the bird-viewing hut erected by the Friends of the Simpson Desert in July 1992. Cold as it was, flutterings, splashings and plonks accompanied my walk to the hut. The bore was a paradise for bird life. It was also a reminder of the early petroleum exploration that took place in the western Simpson in the early 1960s. At one time the volume of water flowing from the bore amounted to 2.5 million litres per day. Despite lobbying from some quarters to have the bore capped, the flow had instead been reduced so that it continued to provide a habitat for a variety of native plants and animals, particularly birds, as well as providing the last source of readily accessible permanent water before crossing the desert from west to east.

My enjoyment of the birdcalls was interrupted by coughing, forced laughs and coffee making of the people camped by the showers and toilets. Why did people camp so close to ‘the amenities’ and each other? I just could not fathom it.