Chloe giving birth to Dalhousie, just five kilometres short of Dalhousie Springs.

6 Dalhousie And to the Centre

– 14 July 1998

You got country in you and there’s a little bit of you in the country.

Jimmy, Docker River, 25 August 1998

Chloe’s calf was born on 14 July. I called the little fellow Dalhousie after the springs a few kilometres away. At 0740, in the full light of day, the birth of Dalhousie commenced with Chloe doing a lot of rolling on her back, inhibited as she was by her hump, scissoring her back legs. For much of the time she lay on her side, the other camels very interested in proceedings.

The calf’s offside foreleg appeared first, followed by his little head, and for an hour Chloe lay panting but not overly distressed. At 10 the birth was complete, Chloe getting to her feet and the calf sclooping to the ground. I was a little concerned about the placenta but again Chloe stood and at 11 it too sclooped wetly to the ground.

It was obvious that Dalhousie was a very strong calf. He took after Kabul, solid and alert. His long legs with their large bony knees were touched with white like the leg warmers of aerobic instructors in winter. Being the experienced mother, Chloe directed him to her very swollen udder and he sucked greedily at her nipples.

As I sat and watched I wondered whether I should shoot him. After all, his meat would make a welcome addition to my diet. Only later in the day did I think on how he might be left to live. It seemed to me that we are often given to dispose of those things that prove an inconvenience. So many things in life had become cheapened and disposable because they did not add value to busy lives. Around 4 p.m. I thought I might have a solution and started work. I built a sling on Chloe’s saddle and thought that Dalhousie could be carried in it. We would have few water problems until we reached the Gibson Desert, so I made certain that all the water was off Chloe and now with Kabul.

I also decided not to move that day in order to allow mother and calf to become stronger. Instead, I set about making the camp more comfortable and recalculated the distances we would have to achieve to arrive at Steep Point in mid-November, before it got too hot.

Distances along tracks marked on maps, calculated while waiting the day.

|

Dalhousie to Yulara |

697 |

|

Yulara to Warburton |

546 |

|

Warburton to Steep Point |

1574 |

|

Total: |

2817 kilometres |

With just 120 days until mid-November, that meant more than 25 kilometres a day. Every day. We could not afford to slow down. We could not fail. Not now, not after all that we had done and endured. I was not yet willing to contemplate what this might mean for the future of little Dalhousie.

The sling worked and the next day we camped in the cattle yards at Dalhousie Springs, hot, fresh water springs, one of the many mound springs of the Great Artesian Basin. It was a stopping place for explorers and the early cameleers of Australia who brought supplies into the country and took away wool.

We had set off in the morning, not long after Dean Ah-Chee, the Witjira Park Ranger, dropped by to meet us, and we made it into Dalhousie Springs in mid-afternoon, covering the seven kilometres in about two hours.

Chloe was reassured at having little Dalhousie close and with his head up he could see the world. As for me, it was wonderful to soak my tired body in the warm springs while the camels ate the pigweed in the yards. I thought about another rest day, but we had to keep moving. The camels needed good feed and routine on the march and I knew I did too.

So, after a day of rest I packed up and we made it to 3 O’clock Creek late in the day. Little Dalhousie made the 14 kilometres unaided. I tried to put him into the sling on Chloe’s saddle but in two days he had already become too big and certainly much heavier. So, at 1 p.m. we set off and I wondered if Dalhousie could follow. He did, and despite lagging back on a couple of stretches he did wonderfully well. When he did hang back, Chloe called to him with a rippling throaty bellow and simply refused to move forward until he had joined us.

Kabul had been keeping a special eye on young Dalhousie. On the morning of the birth he was a most interested spectator. The day after the birth I introduced Kabul to Dalhousie and there was a great deal of sniffing of the new member of the team. If Kabul had not been the sire of Dalhousie, he would most likely have killed him. I knew that Kabul was the father and that they should get along, at least until Dalhousie became a teenager. Kabul put young Dalhousie in his place on a number of occasions. One time gripping his little head between his jaws, and later giving a nip, much to the bleating humiliation of the little fellow.

It rained all afternoon at 3 O’clock Creek. Most things were wet. I was tired, wrinkled, wet and early into the swag.

It was wet again next morning and to make the morning brew I went into the creek to get dry kindling where the stuff was trapped under trees during floods. Because I was obsessed about moving, during that cold rainy day I felt I had to shoot little Dalhousie. He was slowing our progress and I was very concerned that unless we moved at a reasonable rate we would not finish the trip. In the evening, by the fire, I cradled the rifle and opened the breech to the glint of brass. I looked over to Chloe and Dalhousie, who both watched intently.

With the rifle in my hand I walked across to Chloe, sitting down next to Dalhousie, to pat and reassure him. He nuzzled his head against my chest and I knew then it was too late. I had named and bonded with him. To shoot him now would be a treachery too serious to contemplate. But I was going to make sure he kept up, even if I had to carry him myself.

We moved from desert sand country to gibber plain that stretched to the horizon in the north-west and in the course of the day made more than 20 kilometres to beyond Opossum Creek where we found a lonely one-room stone ruin. There were plenty of dingo tracks around the camp and during the night I saw their eyes reflecting the firelight. Little Dalhousie made the camp particularly attractive for dingos, animals that can readily take a camel calf. With Chloe by his side, however, I doubted if a dingo would have an opportunity to harm him. And it would only take a few weeks before he would be too big for a dingo to consider attacking.

We moved across red and shattered rocks the size of cricket balls where finding a safe place for my feet was difficult. I let the camels make their own time, weaving their way around the rocks and we camped 15 kilometres short of Mount Dare Station, formerly a cattle station but now a camp site and hotel servicing desert travellers.

It rained and stormed intermittently during the night and the clouds did not clear until dawn. At 2 a.m., through the wind and rain, Kabul woke me with a series of bellowing cries that in their deep base somehow reminded me of a whale’s call through the ocean. So I poked my head outside the swag and lit up the scene with my headlamp. For a heart-stopping moment I thought it was another feral bull come to challenge Kabul. He was nickering, with the occasional bellow toward Kashgar and Chloe. I had seen this behaviour before, particularly when there was little or no moon or high wind or rain. Kabul liked to see where the others were. I retired to the swag and its warm embrace.

I should have paid more attention and should not have been so lazy. I woke in the morning and put my head out of the swag to check the camels. Kashgar and Kabul – but no Chloe and Dalhousie! I felt the muscle of my heart beat hard and hollow against the bones of my ribs and felt the rapid swollen pulse of blood to my head.

Out of swag, boots, trousers, water and rifle and I was off. I checked the rope. Good mountain climbing rope. It had snapped. Maybe Dalhousie had been walking away and Chloe had pulled and pulled. In any event Chloe was still trailing some rope so I was able to track her. I followed for around two kilometres and finally found them only 500 metres away from the camp.

Chloe was quietly grazing and little Dalhousie cavorting in the breeze. They had walked with the wind and then turned against it to the scent of Kabul, Kashgar and the camp. Neither Chloe nor Dalhousie seemed surprised to see me, and it was no trouble to walk them back. Little did they know how I felt when I looked out of the swag or when I was looking for them – wondering if they had been lost to the desert.

We made it into Mount Dare Station in the afternoon and I led the camels to a small but splendid paddock where the abundance of green stuff obscured their legs and nearly hid little Dalhousie. They proceeded to make themselves even fatter.

Leaving Mount Dare early, we did more than 25 kilometres. Chloe was not her usual self, tossing her head and looking nervously to her left and right. I thought she may have seen some cattle or even donkeys in the distance. Once we camped I untied her from one tree and went to move her to another. With a buck and a canter she pulled away from me. I circled around and finally brought her and Dalhousie back to a tree near Kabul. She hooshed herself down and I gently caressed her face. I reassured her I would not shoot Dalhousie. In what was only a half-lie, I said he made a great addition to the team. My tone seemed to have had the necessary effect. She sighed and only speculated a half-hearted gaping snap at my face.

After dinner and another check of the camels I lay on my back in the swag feeling the heat of food in my belly and counted satellites. Three in 10 minutes. As I looked through the canopy of a nearby tree the night sky was crisscrossed with dark branches so that it looked like the stars were sewn into it.

I breathed the air, could smell Kashgar’s fragrance of warm wool and sweet vegetable digestion and could hear the others chewing. When I called out to them and said their names I could see the shadows of their movement to me, and perhaps a glint of wet eye. I could hear the empty space of silence as they stopped their chewing for a moment, waiting for me to say something more. What a wonderful place to be, in the quiet and the dark with friends.

Heading west next day was cold with the wind whipping unseen sand against my face, tugging at my oilskin coat and pulling at my hopes. I felt it more as I was becoming skinnier and skinnier. There was no fat on my belly and muscles felt tight under the skin of my thighs. When I clenched my jaw I could feel a ripple of sinew and little else.

I contemplated a short cut. It seemed crazy to go to New Crown Station and to Finke when we could cut west and north-west to intersect the track to Kulgera. From just a brief consideration of the map I knew the detour would save us three to four days walking, so we took it.

For most of the day we walked over bleak, brown blood gibber country. To the east was a tree line marking the Finke River and to the west, sun-blasted flattopped mesas so typical of central Australia. We camped 20 kilometres north of the New Crown Station boundary, not far from Charlotte Waters, now an abandoned telegraph station, where Ernest Giles, one of the great European explorers, had returned in 1872 from his first major expedition into central Australia. With two other men Giles left Chambers Pillar around the middle of August and traversed much unexplored to the north-west and west. Further travel was blocked by Lake Amadeus and with weakening horses the small party returned to the Finke River and then Charlotte Waters and Adelaide, where Giles arrived in early 1873.

I woke next day to sheeting rain and a sharp-bladed wind from the south. Fortunately I had continued my practice of covering up the gear with tarps before going to bed. It was also fortunate that I had decided to keep the gas stove, for without it there would have been no hot breakfast brew.

I lay for hours in the swag under the hootchie with the cold wet drops slapping the plastic. The ground around was all clay and to load up was to court disaster. The camels would slip and slide on such a surface and I was not prepared to risk a hurt camel. So I waited and from under the plastic sheet I could see that the camels seemed happy enough; they were either browsing on a bush or recumbent, chewing the cud. So as long as I kept moving them to new feed trees I thought they would be fine.

And still it rained. I saw just one car that day. It fishtailed past me early in the afternoon and the driver stopped long enough to tell me that all tracks in the area were closed. He had no idea of the weather forecast. Why he would be out here ruining the roads I did not ask, he just fishtailed the vehicle away and I was careful to stand clear of the mud spray.

The following day it was still raining. I was up to muesli and coffee from the gas burner and shifted the camels again. Around 1330 the weather looked like changing a little; even so I gathered more wood to ensure the fire kept going.

But then more rain. And more. We were camped on a clay floodplain turning into a bog. While I was dry and warm inside the bivvy bag, outside everything else was wet. In the late afternoon the wind died down and I could hear the rain on the plastic and see water droplets fall from the trees to the puddled water all around. If the rain continued much longer I was pretty sure the swag would be under water. It was not a cheerful prospect so, with a stick, a boot and my hands, I excavated a small trench around the swag, and at the lowest point a drain to take the water away.

Dawn the next morning arrived with the promise of light in the west. It was cold and wet again, but the rain stopped just before the sun dissolved the shadows. The breeze from the south was cold and I could feel it cut through my flesh, though I wore all my clothes and the oilskin coat.

With the hootchie up, and the trench dug around my sleeping place, I was warm all night. Even so, I got up twice in the rain to calm Kabul who was bellowing for some reason. He was not turned to his girls, but rather to the north. I caressed his nose and his flank till I took the trembling away. He settled down to chew his cud and buried his head in my armpit.

From my sleeping place I could watch little Dalhousie creating mischief by cantering to Kashgar, then Kabul and back to Chloe. He would let out a bellow whenever Kashgar or Kabul had a nip at him. After all, was he not the most important camel in the world? Eventually I had to get out of the swag. Having to put on wet trousers, wet socks and boots was not at all pleasant, but once I had the fire going and the brew on the world turned for the better. It seemed to happen every time.

Because water had collected in the tarpaulin hollows over the saddles, I decided to have a proper wash. I stripped off my clothes and boiled the billy again and again. I used my mug to scoop the water from the basin and felt the warmth wash over my body. Even though the wind was cold it was well worth it. I felt clean and fresh and ready to go again.

Given that the western sky appeared to be lighter, the wind drying the ground and a radio weather report that said ‘rain contracting to the east’, I thought we could make a start to Nine Mile Bore later in the afternoon. Having had a good long look at the map, it seemed to me that once we turned to the north-west, much of the ground was sandy and therefore easier for us. The ground was a sponge, so after waiting four hours I thought the surface would be safe for camels and man and we headed for the sand.

And it was safe. In the evening we camped about five kilometres along the track from the Nine Mile Bore. We left the clay bog at around two and headed north. The track turned sandy after about three kilometres proving the map correct, and it was very much easier and safer going once out of the clay.

Little Dalhousie was growing up far too fast and was far too energetic. He spent most of his time trying to be like Kabul, tough and in the lead. With his little head thrown up and legs working hard to keep himself just in front of Kabul, he thought himself the leader of this camel herd, if only for a moment or two. Kabul would quickly bring him down to size with a nip to a leg. Dalhousie would squeal, bleat and scamper up and down the line initiating mini camel stampedes.

The camels seemed to have done well in the course of our wet stop and the girth straps were tighter than normal. On the other hand, my belt needed tightening. A few days would see us at the Kulgera Roadhouse and I began to salivate at the prospect of mixed grills; of eggs, sausages, bacon and steak.

Our camp that night was marvellous, fragrant with the scent of flowers and camels eating sweet green stuff. Just before going to sleep I had a memory of my grandmother’s house in Brisbane. With my two brothers I slept in the covered verandah, her house full of fragrances; of the mango tree in the backyard and the lavender of the potpourri. Camels and I were on sand, there was plenty of wood for a fire and I slept a deep dreamless sleep.

Walking along the track to Coglin Bore I kept an eye out for the short cut to the north-west. I could not find it. As it was we kept on a disused track until we reached the Ghan railway line.

During the expedition I was very aware I was touching history, or even creating a small part of it myself. For a moment, standing on some whiteant rotten sleepers, I was aware of who had been here before me. The Ghan railway was named after the ‘Ghans’, the men from south Asia, including what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan, who came to Australia to work the camels that opened up the interior of Australia, before the arrival of the internal combustion engine and the railway line. These men and their camel teams supplied the overland telegraph, railways and pastoral stations with all their needs. They moved across the desert interior of Australia, from Western Australia to Queensland, and South Australia to the Northern Territory. They did so at the camels’ pace, bringing goods and mail to towns and stations and returning with wool or minerals. Their routes included what became known as the Birdsville Track, as well as the Oodnadatta and Strzelecki Tracks.

By early in the twentieth century though, the camel had lost out to the train and the truck. This was clear by 1925 when the South Australian government passed the Camel Destruction Act. This piece of legislation empowered police to shoot any camel found trespassing or without a registration disk. In 1935 the Marree police reportedly shot 153 camels in one day. The men themselves, those who had come to Australia to work with the animals, either went back to where they were born or disappeared into the Australian population, their names to appear on the war memorials of World War I, lost fighting for a country of which they had become a part. My camel team, Kabul, Chloe and Kashgar, were the descendants of those camels that technology had made redundant. I was selfishly grateful that they had escaped the Camel Destruction Act and police rifles.

The Ghan railway operated until 1980 when it was replaced by a new line, less vulnerable to the flash floods of the interior. The new line ran along a route from Adelaide to Alice Springs to the west of the old line. From the disused railway I turned north. I could not find the track to the west of Duffield siding so I simply took a compass bearing and set off. Just as we reached the track I had a small frisson of pleasure and excitement down the back of my neck. Of course it was impossible to get lost with the Beddome Range to the west, but the satisfaction of getting where you want to go using your brain and a map is something special.

In fact, I was so happy with where we were and the feed everywhere around us, I let the camels loose to graze on yellow flowering green succulent stuff. I dropped to my knees and rubbed noses with Dalhousie. In his surprise he swallowed a bleat and recovered quickly to suckle at my nose.

At the end of the day the camels were all burping and farting and chewing the cud after feasting on even more green stuff. I forgot to put some muesli bars into my pocket and so went without anything to eat until dinner. Nor did I drink apart from the breakfast brew. It was hardly surprising that at the end of the day I felt a ‘too long fighting the surf 's rip’ tiredness. It was only after a big spaghetti dinner and three large mugs of water that I felt a little more energised, but still my muscles were weak, without the spring and elasticity they once had. My thighs were now so skinny I could wrap my two hands around one so that the thumbs and middle fingers touched. It had only been four months with I thought around four more months to go. I knew that my body had to adapt to this going or I would never achieve what in my ignorance and arrogance I had set out to do.

We camped about five kilometres west of Mount Beddome. We crossed the ridge that provided a vantage point to most of the country we had moved through, with the range on the right-hand side. In the late afternoon it was a view of muted reds and yellows, with the dome of a clear blue sky over all.

It was through the country I walked that day that John McDouall Stuart, Charles Sturt’s surveyor on his 1845 expedition to Eyre Creek and the Simpson Desert, moved in his expeditions to cross Australia. In all, from 1858 to 1862, Stuart led six expeditions into the interior of South Australia and north. His last expedition, in 1862, took him through the centre and across the continent then back to Adelaide where he claimed the £2000 reward offered by the South Australian government.

While Stuart survived to return to Adelaide, he did so at extraordinary cost to his health. In the course of his last expedition he was stricken with scurvy. His ankles swelled, his legs turned black and his eyesight dimmed so that survey readings had to be taken by one of his men. His gums were swollen, his teeth became loose and food tasted of his own blood. For a time he was unable to speak and for the last few weeks of the expedition he was carried on a litter between two horses, a sickly pathetic shadow of himself vomiting internal juices and blood.

Even more thought-provoking was what satisfaction of the obsessive quest had done to his mind. On raising the Union Jack on a beach of northern Australia, now called Point Stuart, one of Stuart’s men wrote of him that he ‘went about as if he had no ambition in his life’. Perhaps this was because Stuart recognised the pain that would be associated with the return to Adelaide rather than the completion of a dream that had been fuelling and driving him for so long. Whatever it was, and perhaps it was a combination of obsession satisfied and the privations he had endured for so long, it finally killed him. He died in Scotland on 4 June 1866 at the age of 50. Only seven people attended the funeral of arguably Australia’s greatest explorer.

That morning we started slowly. Kabul would not keep stride by me so I checked along the line to see Chloe pulling on her head rope! She kept holding up proceedings to let greedy little Dalhousie get to her udder. Thankfully things improved in the course of the day. I hoped that the next day we would be on the track to Kulgera.

That night there was hardly a mosquito, or a cloud in the sky, but there was lightning in a wide sweep around the western horizon. The only sound was just after 9 p.m. when I was sure I heard a bat overhead. I could hear its windy, wet-newspaper flapping in the breeze as it got close.

The lightning in the west was a precursor to the rain, which unusually came in from the south-west. With a mighty wind it struck just after midnight and I had not put tarps over the saddles! So I was up in my T-shirt, feet into boots, and on skinny bare legs I ran to Chloe’s canvas sacks and covered all the saddles just as the rain came sheeting down. Camels remained hooshed down and did not appear to be the least bit troubled by the drenching. As for me, I got to the swag wet and spent a deal of time trying to sponge dry myself before getting into my sleeping bag. Still, thanks to the bivvy bag, I was not too cold.

Stopped at a crossing on the now abandoned Ghan Railway.

The day dawned cloudy and cold but in the south-west a band of blue later in the day expanded to fill the sky and I wore all my clothes and over all the oilskin. The wind, cold and penetrating, blew all day. Even at night it blew, under a frigid starry sky.

The following day it was even colder. I put my head out of the swag to have it buffeted by a cold southerly wind. It was very unpleasant, like opening a back door to a winter storm, and I was tempted to snuggle back into the feather-down warmth. It was only the prospect of a couple of hot brews and a self-conscious guilt at my softness that got me moving.

But once out of the swag I had trouble standing. It was the old Achilles tendon problem. With the cold weather it had started to flare up again. I had put on a new pair of boots the previous morning as the old pair had hardened almost rigid, having been wet and dry so often the leather had lost its suppleness. I took a couple of aspirin in the evening and did what I always did then, placed folded camel blankets at the foot of the swag and elevated my feet.

For a few hours in the morning I could only hobble along as the camels paced confidently along the track, their noses in the air. In fact when I thought about it my movement was more a stumble into the cold wind. I wondered for a moment that things would not get better, and had to remind myself – one day at a time. There was still a long, long way to go.

Little Dalhousie had become more and more ‘bully’. He seemed to be growing before my eyes and trying out a variety of foods other than his mother’s milk. At the very least he appeared to suck on them, and I knew his firm baby teeth were hard and sharp. I knew because I put my honey-covered finger in his mouth. I thought he might lick it or maybe suck on it thinking it a sweet nipple, but the little fellow bit hard. Along with biting he was growing too, and beginning to make a throaty burbling noise, very bully sounding, at which Kabul grumbled his irritation.

We had come more than halfway across the continent, having passed the day before the turn-off to Lambert’s midway point, the geographical centre of Australia. Reading the map I wondered how I would make another four months. I felt weak. Many of the muscles I once had were gone, my back ached, my Achilles injury made me limp. I even had trouble, particularly at the end of the day, lifting the saddles off Kabul and Chloe. When I grimaced I felt the skin so tight across the bones of my face I wondered why it did not split.

After I wrote up my diary that night I went to bed exhausted. The cold and the worry of the wind saw the end of me and I sought refuge in the warm swag. Next morning I woke to find the country coated in frost. Even the camels had frost collected in the thick deep wool of their humps. In the course of the day we moved over country with rocky outcrops containing frozen white quartz. The exposed weathered rock looked like the backbones of the Dreamtime creatures that Aboriginal people said made the land. I imagined we were walking through an ancient sea bed where time was revealing these ancient creatures with a whisper of wind or a teardrop from the sky.

We also encountered our first cattle grid in the Northern Territory, a sure stop for camels as their pads, like cattle feet, would have fallen between the metals bars. Unfortunately for us, there was no gate to the left or the right, so taking a gamble we followed the fence to the right which paralleled the track. We walked and failed to find a gate to get us back onto the track. A moment later, something went very wrong.

We dropped into one creek bed and for some reason the camels baulked. Then they bolted. It was a stampede that ended after a few metres but I was alert to the fact they were very nervous about something. Out of the creek and again we followed the fence line that kept us from the track. There was still no gate, but we persisted and dropped into another creek bed. As we landed in the sand I turned to Kabul. In the shadows of the river red gums I could see the whites of his eyes, blank moons struck with the dawn of fear. Nostrils were flaring and ears flapping. I looked around for the reason, but all I could make out was the wind in the trees, the cries of galahs and the scent of eucalyptus.

Kabul started to prance then he reared up and kicked my leg. Fortunately he must have collected me on the uprise of his kick, for while I was knocked down I was not badly hurt. I rolled away from the now terrified three and a half camels to the safety of a tree. Nothing would hold them back.

Kabul took off at a canter and the other two were inexorably drawn along. Little Dalhousie screamed, ran into a fence, and bounced off. But no-one stopped. Trees and bushes were no barrier to the three. I could hear branches breaking and the snap of timber as one or two of the camels found themselves on the wrong side.

I was on my feet and hobbled after them. They headed back the way we had come. For more than a kilometre I followed, hearing the snap of timber and watching the tops of trees explode as the camels galloped through. Weak and helpless, in my deepest of selves I knew all was over. One camel would find itself on the wrong side of a tree too large to give way and be killed, others hurt, gear ruined. I even thought of having to bring the rifle to Kabul’s head, having to put him down. At this I sobbed and ran and stumbled to where they had finally stopped.

When I arrived they stood trembling, looking at me through wet eyes, chests heaving after their gallop. At least they remembered to look contrite. I couldn’t bring myself to use harsh words on Kabul, so I was friendly and calming. I caressed his neck and his head and gently blew into his nose. I spoke words of soft love to Chloe, Kashgar and Dalhousie, grouped close together in fear.

Soon I could feel the relaxation of muscles in Kabul’s neck and chest. After a few minutes, when camel and human breathing returned to normal, I called him on. And he followed, back to the grid where I started to fill it in with sticks and gravel and rock. Just as I was about to apply the sand, handful by handful, a couple pulled up in their Toyota. They had a shovel, so the job was made easy. I got the camels across and then pulled up the sticks and dug out the sand so that the grid was effective. Walking down the track we passed within 20 metres of the place where Kabul had taken fright. He passed by without even a flicker of recognition. I had no idea what provoked the fear, though I looked, smelled and listened as closely as I could. It was the first time Kabul had behaved that way, without apparent provocation, and it terrified me that it could happen at any time, perhaps when I least expected it and I was most vulnerable.

We arrived at Kulgera late in the afternoon and I walked around checking the adjacent racecourse fence line, only a few hundred metres from the highway, and let the camels feed in the central ring. Once the camels were settled, I made my way up to the Kulgera Roadhouse. The roof of the place was shining corrugated iron and as I approached the smell of diesel, sewage, alcohol and impatient lies seemed to hang over the place. Not a place where many people lingered, it sat astride the Stuart Highway 300 kilometres south of Alice Springs. The Stuart Highway was named after John McDouall Stuart whose tracks I had already crossed, and the highway followed some of the route he blazed across the continent from Adelaide in the south to east of Darwin in the north.

My first stop was the restaurant. I ordered roast lamb and as I wrote up the day thick rich gravy dripped onto my diary. It was cold outside and greasy warm inside the roadhouse. I helped myself to another serving of lamb and later went next door to the bar.

The implications of appetite visited me next night. The kitchen hand, a young rat-faced fellow with heroin acne and greasy, long braided ponytail, abused me for having two servings the previous night and warned me against breaking the rules. Instead of going back a second time I found the largest plate I could find. I filled it with greasy stuff, made a small pile of sweet lamb slices, sat down and ate. The rat kept an eye on me while I steadily worked my way through the calories.

Now that I was back in communication with the world I had a couple of jobs to do. First was a visit to the police station. Here I met with Phil Clapin, Kulgera’s police sergeant. Like all the police I met on the trip he was free with sensible advice and very helpful. He gave me parcels from Amber that included maps, moleskin pants and soft-pointed rounds for the rifle.

Phil was broad and tall, with black hair and black bushy moustache. We had a chat. Or rather, like many of the police I met, Phil went out of his way to sound me out. He told me he had watched me in the pub at the roadhouse the night before. When he heard about me he thought I would be all purple clothes, pierced bits and dreadlocks, ‘like a lot of the camel people we get through here.’ He said he thought I was okay. At the very least I could talk to people and not piss them off. He said he was happy to help.

‘It’s like I always say, you don’t have to be feral to love the country,’ he told me. This country is large enough for all of us. Just because we’re different doesn’t mean I’m a bastard. I’ve helped a lot of them.’

Phil also noted that it did not make much sense that the camel lady took more than nine months to walk and ride from west of Alice Springs to the west coast of Australia. ‘She didn’t even cross half of the country,’ he said. ‘You’ve just walked more than halfway across the country already, including the bloody Simpson Desert with its dunes, and you’ve taken what, four months?’ I nodded. ‘What on earth was she doing all that time?’ he asked.

Without wanting to enter into that discussion, I took myself back to the dining room of the roadhouse and morning tea. I sorted out the maps and found out that Warakurna, Warburton and Yulara had good stores. I also booked a seat on a Greyhound bus to Alice Springs to do some shopping.

I had a haircut, shower, made a list of shopping needs and organised washing for the next day in Alice Springs. I visited the camels just on dark, and very feral they were too. Chloe carried on over Dalhousie, Kashgar carried on as if on heat with lots of tail flipping and, on my arrival, Kabul trotted up, head rearing, burbling and trying to blow out his dulaa. What a difference a rest made! Perhaps he had forgotten he was a gelding. Maybe he did not recognise me with my hair cut. After a few words he soon calmed down.

From Kulgera I rode on a Greyhound bus to Alice Springs early next morning. I did the necessary shopping and washing, though there was not time enough to dry all my gear. I got into town at 1.45 p.m. and left at 3 with a checkin at the Greyhound desk at 2.30. ‘Otherwise, luv,’ said the passion pink floral dress, ‘youse might lose yer seat.’ It meant that all I got to see of the Alice was a laundromat and the inside of a supermarket. Not very exciting but I was happy to get the things I needed. In Alice I could have been anywhere in the world. Supermarkets, car parks, pubs, kerbing and air-conditioning. If you really wanted to you could easily isolate yourself from the land around you. Even there, in one of the most remote places on earth you could feel relaxed, comfortable and safe. I had to get back to the camels.

On the bus back to my humped friends I could feel the vibrations of engine through my seat and the warmth of the heating wrapped around me willing me to sleep. While German and English backpackers flirted and shared notes on the cheapest accommodation deals in Adelaide, I wondered why I persisted with my trip. The intangibility of satisfaction. You could taste it but you could not hold it or see it. Was it worth the tension, pain, cold and tiredness? God, why did I persist with the Legion when I knew what it was and what it did? Maybe it was so I could be happy with myself. If there is no passion, no adventure, what is life? I spent the next day cleaning gear, writing letters and making phone calls. Phil Clapin was a great help. I parcelled up my diary, letters, film and maps in a cylinder to send home. Phil wouldn’t take more than $20. He also let me use the station phone to call cattle stations on my route to the west.

Late in the day I made my way to the roadhouse thinking that it was probably the last mixed grill, shower or beer for a while. The roadhouse was a lot more than a collection of petrol bowsers. It offered camping facilities, a restaurant, a bar and a chance for conversation and fictions that made men feel better about themselves.

In the bar were the self-styled frontiersmen, their backs to the sparks from the roaring fire, and a fascist policy statement on the wall. ‘One man one vote – people have to earn the right for a place in this country. If you don‘t like it get out!’

The people who worked at the roadhouse spent 10 days on the job and five days off, normally going back to the Alice for a ‘blow’ or a rest. Leaving his scrutiny of the restaurant, Ratman served at the bar selling beer and rum. He believed he was a frontiersman, working as he did at the interface between Aboriginal people and their access to the bar in the centre of Australia. With an upward tilt of his head, to me he said, ‘Bloody boongs.’ Then to an Aboriginal man close to me, ‘Yer pissed, so fuck off.’ I watched, a passive accomplice in the humiliation of another person.

There were stories in the bar about four-wheel drives and bogs. Beers rested on bellies that muffined over shorts. I did not tell anyone about what I had done. The noise was too loud and busy so that the laughs and declarations of truth were discordant and hurt my ears. I ate my mixed grill and headed back to the camels because the bar was not my place.

I passed seven or eight Aboriginal people camped around an abandoned vehicle just beyond the petrol station. The fire was low but their eyes were bright. They told me they were from Finke, where alcohol was unavailable, come in to have a drink. I asked if they had plenty of tucker. An older woman said, ‘Tucker, yeah, we’re all right for eating. Back to Finke tomorrow. Thanks.’

The following morning was a city grey sky with light rain. The sky cleared from the west, the cloud pushed east to reveal blue. I lay in my swag and looked to the blue that grew and grew. It was time to start again.

Despite initial frustration over a lack of up-to-date mapping of fences I took a short cut into Mount Cavenagh Station and we found ourselves on the road to Mulga Park Station, less than 20 kilometres from Victory Downs. It was a very good day’s run.

I set up camp and put the camels out on long lines to feed. Then I pulled out my small radio to listen to the ABC news. The day before I had spoken with Tom Harwood out at Longreach, in western Queensland, and he must have liked the story. He got it on to Brisbane and then ABC Radio National PM. I was checking Chloe’s line when I heard something about camels on the radio. It was about us and I thought most of Australia would have heard! Maybe some would help fund the Alone Across Australia expedition. I could only hope so.

Meanwhile, I kept checking distances. I was obsessive about distances. Opening the map, I made lists of distances I had yet to walk and tried to estimate how many days it would take to walk one map sheet of 250,000:1. I confirmed the calculation made short of Dalhousie Springs. A minimum of 25 kilometres per day. Every day. There could be no rest.

In the evening we camped 10 kilometres west of Victory Downs homestead. When we turned into the station earlier in the day I found to my surprise they had a great little shop! I bought an orange, sweet and fresh, two boiled eggs, one ice-cream, one packet of salted peanuts, six sausages, one can tropical fruit, five disposable razors, one Coke. While talking with the family outside their house, I consumed all but the can, sausages and razors.

At about 65 kilometres west of Victory Downs we met Nathan out on patrol of the pastoral lease. He told me that Victory Downs was losing 300 head of cattle a year from its furthest paddock, near Ernabella, to the south-west. Apparently a man from Uluru country would soon appear in court. He had been turned in by people from Ernabella. The Victoria Downs people posted a $l000 reward for anyone reporting theft of a beast. Nathan told me that people would drive up to an animal, shoot it and hack off meat from the side not on the ground. It meant that along with the killing and theft at least half of the meat was wasted and left to rot.

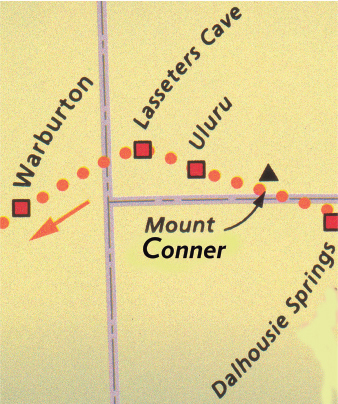

As Nathan drove off and the shadows began to grow from under the trees and bushes to march across the track, I did a short calculation. We had done l08 kilometres in three days. It hardly seemed possible; we were about 75 kilometres from Mulga Park Station where the track would take us north to Mount Conner and then west to Uluru. To the Western Australian border from Mulga Park was about 400 kilometres. It seemed to me that reaching the WA border by the end of the month was achievable. I could see to the end of the journey and repeated to myself a mantra, ‘I could not, must not fail.’

I sat on the food tin and watched little Dalhousie as he grew up. His ears had peeled away from his head, so that at a call from me or Chloe his ears swivelled and turned. He was becoming ever more assertive and very self-centred. He would purse his lips and attempt to bellow, though it sounded more of a bleat. He even started to eat or nibble some of the plants of his elders but still followed close in Chloe’s wake.

The morning was glorious with the sun rising to a full moon in the west. We camped at the bottom of a red rock weather-worn feature near to the track only 60 kilometres or so from Mulga Park Station. The feed was excellent and I left the camels alone to think camel thoughts while they rested recumbent, chewing their cud.

As the camels languidly chewed their cud, I set up the mobile sat phone and called Amber. It soon became clear that one issue I needed to address was that of permits. Aboriginal country meant I needed permits to move across it. Officers of Uluru National Park and the Central Land Council had called but Amber had no luck in getting in touch with them. I needed permits to move across the land because without them my presence would be illegal; or, at the very least, inconsistent with the relevant legislation and policy – whatever that policy was.

I set off in the morning thinking about paperwork until we moved past the Ernabella turnoff. At quarter right, just two kilometres after the turnoff to the Ernabella Aboriginal community, I could see the giant dinner plate of Mount Conner, so named by William Gosse, another European explorer, in 1873, and also known by its Aboriginal name of Artilla. We were at last moving through the centre of Australia, the great bowl that held Uluru, Kata Tjuta, Lake Amadeus and Kings Canyon, and that early European explorers, including Charles Sturt, thought held an inland sea.

Thinking it rude to turn up unannounced to someone’s home in the dark, late in the afternoon I camped just short of Mulga Park Station. Shane Nicol, the lease owner’s son, came out to see us and he returned later with pizza, beer and fruit cake! We chatted about his former place, down south in South Australia, the prevalence of camels on the property – some hundreds according to Shane – and a route to the west. He even suggested following a station track which would have led to the Docker River road and then west.

His enthusiasm took me to the map and I took it from where it lay on my swag and smoothed the case flat on the ground, my headlamp casting a beam across its surface while the insects of the night buzzed and clicked around my head. Not only was the track through Aboriginal country it was at least l30 kilometres as the crow flew and considerably more given the six metre sand dunes. I knew I needed to call the National Parks people and the Central Land Council. I also needed to speak with the Land Council in Western Australia to confirm permits for Aboriginal country there. There was a lot of paperwork to do.

The camels and I walked in to Mulga Park Station in the morning, only two kilometres or so up the road from where we had camped. Over a cup of tea I met Neville, Shane’s father, and we discussed cattle prices and the fact that there was Aboriginal ‘men’s business’ in the Musgrave Ranges to the west. ‘Men’s business’ meant the initiation of young men into the sacred knowledge of the country. In a practical sense it meant that I could not move through this area, which would have cut hundreds of kilometres and weeks from my journey.

I woke next day in a warm bed of blue striped flannelette sheets and feather quilt, lent to me by Alissa, newly married to Shane. After thanking the newlyweds I saddled up the camels and was feeling fine. By 9 a.m., however, I started to get stomach cramps, daggers that struck toward my spine. The cramps were so bad I doubled over from the spasms. Even so, I knew I had to keep moving. I had so little strength that getting one foot in front of the other was an achievement won from pain.

It was my good fortune that Dorothea, Colleen, and Dorothea’s two boys pulled up just before 5.30. Dorothea was a doctor from Bega on the New South Wales South Coast and had taken her sons out of school to travel around Australia for eight months. They invited me to dinner and fed me boiled eggs and potato and cans of fizzy drink. If I had been on my own I would have had nothing more than a large coffee and to bed at 6.30 or so.

I asked Dorothea why she thought it was so important for her sons to see Australia rather than continue through school that year. She smiled at me a gentle smile and reminded me that it was more important to share a sense of wonder and belonging. Wonder could be had by moving through the country, feeling the sun on your skin and talking to people who lived on the land. Belonging could be had in understanding that this place, this country and the people in it were part of us as Australians. Everything else could be learned. She was right.

Next day we camped within a few kilometres of the great elevated red dish of Mount Conner. I hoped the end of the day would see us on the track to the Curtin Springs yards, but I was wrong. Late in the evening I lay in the swag, tired but unable to sleep. We did not make it to the turnoff, or maybe I missed it. Either way I thought it must have been very close. As well as being weary my body ached and my joints hurt. Dorothea diagnosed me with a stomach virus. As she said, ‘Nothing to be done but to go to bed with a hot water bottle’ so as to slow the constant spasms in my belly. Even so I had to eat and dinner was uninspiring, of noodles, one can of baked beans, one slice of fruit cake and lots of water.

Just south of Mount Conner and two days from Curtin Springs.

We passed a sun-blasted rocky escarpment to the west of Mount Conner and camped among the sharp rocks. I did not even bother with a fire. All I wanted to do was lie on my back and sleep. I felt my belly concave, reaching for my backbone, and the gasses in my gut, product of the virus. But I knew that no matter what the day brought, no matter how much it hurt, nothing would ever take away from ‘the wond'rous glory of the everlasting stars’.

In the morning, feeling pathetically weak, I forced myself to move and we made it to Curtin Springs. The camels I let loose in yards full of pigweed. As I sat to write up my diary I could hear Kabul rolling and farting with joy. Little Dalhousie was clearly chuffed as Chloe just stood still and he got to drink his fill. Kashgar sighed with pleasure, the flowering pigweed hanging from both corners of her mouth.

Given the presence of the caravan park, fuel bowsers and the small bar, I anticipated more than a few people stopped to enjoy a few beers. What I did not anticipate were the numbers of buses and four-wheel drives passing through ‘The Springs’ on their way to ‘The Rock’. The road to Yulara, the tourist resort just outside the National Park boundary that includes Uluru and Kata Tjuta, was a good sealed road and just a few hours by car or bus from Alice Springs. While the road did not require a four-wheel drive, I was sure the car hire companies were not quick to tell their customers. After all, how can you have an ‘Outback experience’ without a four-wheel drive?

I made a couple of phone calls, one to Amber to get an update on permits, the other to Nick Smail at the Frontier Camel Depot at Yulara. I was keen to stay close to the Camel Depot and camel friendly people while I did my shopping at the Yulara supermarket.

The small pub at Curtin Springs beckoned. I leaned against the long arm of the L-shaped bar and ordered a beer from Ash Severin, the barman. Peter, his father, ran Curtin Springs as a cattle station, taking up the lease in 1956. But most of their money came from the bar and the restaurant just off the highway. On the walls of the bar were ripped and faded flyers of roundups and rodeos, business cards from around the world and comments scrawled in pen, ‘Great pub!’ ‘Great beer!’ and ‘Great place!’ At the far end of the bar I saw a large green Akubra of the sort favoured by the cattlemen of the Territory and a shiny pink face. He said, ‘and the best thing is, yer jump off the ute, throw yer arms around the mother’s neck and cut the bastard’s throat. They goes down then.’ He brought out a large knife he had in a pouch at his side and in sweeping arcs began to flourish the blade.

‘And then,’ as he was sure everyone was listening, ‘ya push the blade into its chest and rip out the camel’s still beating heart,’ and he clenched the air and his curved fingers moved. ‘Too many camels anyway,’ he said, reaching for his beer.

Ash looked at me, smiled and said, ‘Mate, he’s a wanker,’ and from the corner of my eye could see him shake his head. I took my eye from the green Akubra and two people away along the bar, I saw a smoker. He leaned his greasy green rump against the bar and held his cigarette in his right hand, between thumb and middle finger, so that the lighted end almost burned his palm. When he put the filtered end to his lips it was if he was clawing at his own face. The sleeves of his jumper were pulled up and bunched at the elbows to reveal bleeding tattoos of knives and women. He ordered a rum and Coke and I tuned into what he was telling the two British girls who leaned forward into the conversation, hanging off his every word.

He said he had worked at Lightning Ridge in northern New South Wales. ‘Lots of seam opal there’, he said. ‘You get the black stuff in long seams, like black gold.’ His lies were empty things that fell at my feet. I had worked at Lightning Ridge and knew that the opal came in pockets of nodules that you snipped to see what colour they were. So I sighed to myself and turned my body away from them. Even so, I could still hear his lecture.

He talked about his job, ‘From over East. I sell gearboxes and shit. Give out calendars with pictures of sheilas on ‘em.’ Then, in what was probably a response to a question from one of the girls, I heard ‘Blacks! Blacks! Just let me tell you about blacks.’ And I turned to face him. He was dirty stubble on a greasy face, hair hidden underneath a Caterpillar dozer cap and a shine to his small pig eyes, warming to his subject.

‘Bastards they are. And don’t we give ’em everything? Let me tell ya, my brother had an Abo wife, and a kid by her. Pissed her off and got another wife with three kids. I’m telling yers that the little coon kid gets more benefits than the other three put together.’ And he blew out his cheeks, greasy and bristled. For some reason his shiny eyes lighted on me and as he drew himself almost as tall as me, he asked too loudly, ‘So what do ya reckon about that?’ The bar went quiet and I felt the blood pulse in my ears.

I looked at his boots where the steel caps showed through, to the skinny calves, the smear of grease on a hairless knee, the greasy green shorts, the belly, the beige V-necked bunched jumper, the cigarette, the stubble, skin, cap and shiny eyes. I put my beer on the bar, turned to him and said very slowly to everyone, ‘Mate, you are a liar and an ignorant racist bastard.’

I turned from him and ordered a coffee from Ash. I held the polystyrene cup against me and said to Caterpillar Cap, ‘I’m going outside to drink my coffee in the fresh air. If you are looking for trouble, you’ll find it out with me.’

He didn’t follow, which was just as well. I was having enough trouble walking, without having to deal with a brawl. Sometimes you have to do what you think is right. He was not from the bush, but went from bar to bar across the country where he demeaned himself, compromised others and flamed in me a white-hot sense of righteousness.

I lay down in my swag that night, put my hands behind my head, looked at the stars and wondered why Caterpillar Cap and his wilful violent ugliness were tolerated when all they did was alienate and distance people. In a different environment, he would probably retreat to the shadows and keep his poisonous thoughts to himself. Here, though, where people stopped for minutes or hours and met for moments, it was possible to be whatever you wanted to be. It was possible to tell the world what you really thought without a care for seeing people again or being responsible for your words or actions. Curtin Springs would be just the place for Caterpillar Cap.

At around 2 p.m. next day, 30 kilometres west of Curtin Springs, a Land Rover pulled up and out stepped Mark Swindells. Almost two metres tall, with straight, jet black hair and an open, frank face, Mark had been one of a party walking from Broome to Melbourne with camels, but turned back at the Western Australia– Northern Territory border. We talked about camels and he told me he had worked for Noel Fullerton outside Alice Springs. ‘A real bush gentleman,’ Mark described him, and probably Australia’s foremost camel man.

Mark was with William who reckoned he deserted from the Foreign Legion in the early 1960s. I was not so sure, he didn’t even know the ‘Boudin,’ the song known by every Legionnaire. Mark thought William was with British Intelligence and sent to Vietnam. I smiled. At least William had some yarns. Not like Caterpillar Cap, the poisonous smoker with bleeding tattoos. Mark and I talked about my plans, his plans and what might become of my four camel friends.

Early next morning we saw Uluru and further away Kata Tjuta, the Anunga Aboriginal people’s name meaning ‘place of many heads’, red living things floating on a sea of grey green scrub. Uluru’s colour changed in the course of the day, a beating heart affected by cloudy moods. We moved single file through a forest of desert oaks that bent and sighed in the breeze. I thought that if only we knew the language we could understand the whispered secrets of the land.

I watched Uluru growing in the distance, looking like a giant red tree stump floating on the horizon above the bleached and faded gold of prickly spinifex growing in the red earth. I imagined people looking and marvelling at it for tens of thousands of years. At that thought my heart swelled in a bond with those long gone and a shared experience of looking and reaching for understanding of the country.

More pragmatically, the closer we got to Yulara the more concerned I was about getting through the National Park and to the Docker River track beyond. We had permits for the land beyond Uluru and to Warburton in Western Australia, but the National Park Authority was still to make its decision. I had waited on a decision for months and anyway, why would anyone want to stop a fellow with three and a half camels walking across some country?

The administrative aspect of this trip occupied the brown folder in Chloe’s canvas saddle bag. Emotionally, it was eating me away. Just as I was thinking dark thoughts about European administrators a battered Toyota pulled up by the side of the road. Bill, a European adviser with the Mutitjulu community on the southern side of the Rock where the traditional owners lived, stepped from the vehicle. He said, ‘Heard about you the other day. People are looking forward to meeting you. There’s something about a meeting tonight though. It’s National Parks and the traditional owners’ meeting. They’re talking about your application. The local people are fine. See you in a few days.’ I was delighted and much relieved, and we continued on our way, listening to the whisper of the desert oaks.

I should not have felt so relaxed. Next day, after I set up camp at Nick Smail’s Frontier Camel Depot, I called one of the National Park Service officials named Peter. At the end of the call I thought about naming him a few other things. In his best public official’s voice, he said that the traditional owners had endorsed his suggestion ‘that your camel trip would not be in the best interest of the park’.

To put my application in context, Peter told me of an early-morning patrol around the base of the Rock. It was done by one of his Parks officers ‘a little while back’. It had been just on dawn and he had noticed a wisp of smoke coming from a cave. The cave was strictly out of bounds for tourists. It was a place for secret men’s business, where the rituals necessary for the care of the land were performed.

The ranger worked his way to the cave. At a respectful distance from its mouth he asked if anyone was inside. From inside came shouts of abuse, slung from a female voice. It was not long before she presented herself, blonde, naked except for the red earth smeared on her body and a loud California accent.

The ranger tried to tell her that the place was sacred to the local people, that it was special to the men. That she was trespassing. She just put her hands on her hips and said, ‘Hey man. What’s the problem? Fuck off. I have just as much right as anyone. I want to get in touch with the vibe.’

Later, when the Aboriginal men were told, they spoke together sadly, quietly and spent days tending the place and the land. Peter told me that because Uluru was so accessible, people like the Californian were always a problem. ‘It’s like they think they have a monopoly on understanding,’ he said. But this did not help me at all.

I hung on the end of the telephone thinking about what Peter had done. By framing the question as he had, he got the answer he wanted. Like most people, Aboriginal people are, on the whole, polite and disinclined to argue a point. It was far easier to agree than to argue and create tension between people. It seemed I did not have many friends in the National Park Service, or that the National Parks people were nervous about creating some sort of precedent. It all meant that the Management Committee did not want me to walk camels along the road in the park. I could, according to Peter, float the camels through the park while I walked. However, I could not camp in the park. This meant I would have to walk 55 kilometres or so in a day, or organise to be picked up.

So, four months after my initial application, they came up with this. No reason other than, ‘it doesn’t fit within our scheme of management’. There was nothing written, no right of appeal. What to do? There were no fences around the park. In fact feral camels were common sights and another three and a half for two days or so would make no difference. I undertook not to camp anywhere near Uluru or Kata Tjuta, I just wanted to move across the country. There was no flexibility, no compromise. I was forbidden entry.

If I was to go around the park I would need more permits. But I did not want to walk the road, just get to the Docker River track where I did have permits. The situation called for some sanity. I rang National Parks again, hoping to get some help out of the impasse. A warm voice at the other end said, ‘Mate, heard about you. Sounds a bit stiff to me. If I were you I’d follow the northern boundary. Strictly speaking that way you would not be “moving through” the park or need Aboriginal permits. Of course don’t quote me, and you had better look out for feral camels. Good on you.’

After a stressful morning of phone calls, Jarred took me along to the Outback Pioneer Hotel at Yulara. He wanted to fill me with beer and deep-fried food. Jarred was not yet 30 but wise and thoughtful. He worked with Nick Smail at the Frontier Camel Depot, a friendly, well-run camel operation with the greatest advertisement of them all, relaxed fat camels.

Nick was the boss of the operation. Slim, brown and passionate about camels, Nick was helpful, warm and obviously pleased that Kabul, Chloe, Kashgar and little Dalhousie were in very good condition. Along with Noel Fullerton and Rex Ellis, Nick was a giant of the Australian camel industry.

At the Outback Pioneer Jarred fed me hamburger, chips and beer. And what a coincidence! We happened to see George. George was the self-styled jackaroo of Curtin Springs, the one brandishing his knife at the bar for the benefit of tourists, waxing on about cutting out still-beating camel hearts. I remember him saying, ‘Yeah mate. Gets dirty out here.’

As I told Jarred the story his grin grew wider and the gloss white of his teeth had a special sheen. George was playing pool near the bar, throwing back his head and laughing too loudly at a shared joke with blotchy faced and pasty skinned Yulara workers having a day off. I told Jarred I needed to introduce myself. We stood up from the table and made our way to George. But he saw us coming, blinked twice, sucked in a breath then bleated, ‘Jesus, not him again, I’m late for an appointment.’

Later, spluttering in his beer, Jarred told me that George was in fact an electrician at Yulara. Apparently he took himself off to Curtin Springs once or twice a week to ‘play the lad’. George particularly liked talking about camels. ‘Shoot ’em. And if you’re a real bloke, rip their hearts out.’ He was a fake.

We left the fakes, fools and officials and camped north-east of Kata Tjuta, and the day after beside the track to Docker River and the Western Australia border. I stood looking back at Uluru and Kata Tjuta and could not help but feel sad. Two landforms that had been imbued with meaning by Aboriginal people had instead become tourist sites like Niagara Falls or the Grand Canyon. I supposed the Cultural Centre attempted to convey to tourists some of the importance of the places to Aboriginal people. But the visitors did not care. They just wanted a T-shirt that said, ‘I climbed the Rock’.

People imbued things with meaning. The Aboriginal view of the world and their place in it was uniquely theirs. If they did not feel they could share it, or if we did not try to understand it, we would lose an insight into the world that few people ever had. As human beings we would lose a part of ourselves, a way of thinking about the world and the way we lived and died in it. I turned west and I must have sighed because I felt Kabul close and he gave me a reassuring nuzzle on my shoulder. I felt an emptiness that so much knowledge could be lost with so little care. In the days and weeks ahead I reflected on people who moved across the land and wondered why we paid them so little regard. More practically, I thought we would be at Lasseter’s cave in a couple of days, which meant that we would not be too far from Warakurna and the border.

All the camels were still very fat and at the end of that day I found time to take to them great armloads of succulents which they crunched and chewed and swallowed. The pile in front of Chloe was up to her chest and she took almost an hour to get through it all. I watched the muscles of her jaw working, munching her way through the crunchy green stuff. For hours after there was much chewing of cud, then farting. Camels seemed to fart a lot, especially after eating succulent things.

Earlier in the day we crossed the dry bed of the Irving River and as we did so saw a dingo look us over. Seeing there were so many he tried to scamper off. I thought he was lame in his near side foreleg. I watched him move off to the south, toward the red ranges of the Petermanns. Sometimes I imagined the bent and fractured hills to be the petrified roots of all that remained of the great tree of life at Uluru.

There were so many changes in the land. Shadows, contrasts and primary colours filled my mind’s eye and my walk every moment of the day. I felt I was starting to know it, to feel it in my pores and in my chest. But without some knowledge of the land I did not think this country would have been easy on me. The Aboriginal people had a long time to learn to live with the land, to know its secret places and secret ways that made life easier. What must the early white explorers have felt! They knew maps, horses and their men. But how could they know a timeless land without living in it and being part of it? Instead, they walked across its skin, not touching the pulses or hearing the sighs of the old land.

We camped just short of Pinta Punta, past a whiteant-riddled sign that declared Ernest Giles named the Petermann Range after Sir Augustus Petermann, a cartographer. The faded sign gave a date that indicated Giles and his party had been moving though this country in summer. What a heated hell it must have been. Pausing for a while in front of the sign I was reminded that on this expedition he was the first European to see Mount Olga, as he named Kata Tjuta, and more significantly, later in the expedition he named Mount Destruction. I was to continue west across much of the land crossed and labelled by Giles. In a few weeks I would arrive near the place where he lost one of his men. To the south of where we stood were the ranges, shattered, jagged and fractured indigo and red knobs, knuckles and teeth. Perhaps, rather than roots, they were the desiccated bones of a Dreamtime creature breaking the surface of the dark red sea, exposed to those who understood what they saw.

We saw a lone male camel. I bent down to check his tracks and his off-side rear pad print had ridges in it. I looked into the distance and saw him, too old now to gather a harem around himself and probably too old to hold his own in a bachelor group. In a land hard on all those who lived in it, I wondered how long he might survive. There were no old age homes here, for camels or for people. You survived, grew old, got thin and died. Elemental stuff, and a reminder of how far we had come from the coast where people grew fat, old and died on life support machines, with flaccid muscle and bones too weak to carry them.

We walked parallel to the raised red of the Ranges and looked up to the bones left to bleach under the sun. I was distracted, thinking of the Aboriginal people who had lived here for thousands of years, so Kabul heard it first. I watched his hippo-like ears prick and swivel to catch the sound. I heard it at last, still a long way off. A bang, whine and shake of a large metallic dog. We moved north to make contact. I watched the red crust of the land scroll beneath our feet, looked up to white trunks and green crowns painted against the blue sky and turned toward the track and the direction of the sound.

I wanted to wave to let people know I was there and okay. The vehicle slowed in the distance and we had time to consider each other. The car was an old purple Holden sedan, much battered, the windscreen a cobweb of splinters and the other windows down. Black arms hung outside the car reaching for the cool and the country. There were two men in the front and five along the back seat.

As they pulled up, I could hear, even over the rattle of the engine, a discussion among the men. The discussion was not in English. A young man wearing a black and white striped football jumper, baggy black shorts, a mop of black hair and with a very generous belly stepped from the back of the car. He leaned on the car door and asked me if everything was okay. I told him everything was fine. The country was good to us. The young man nodded and I heard a voice of warm tobacco from the front of the vehicle, ‘You all right then?’ I nodded and Kabul blew from his nose in agreement.

Then a pause. The men in the rear of the vehicle looked away and the young man who had left the car found himself a very interesting tree to consider. They were waiting for something. I speculated with a ‘You blokes like a cup of tea?’ Faces instantly transformed from shiny black to red and white with smiles. The young man moved forward and opened the door for the man in the front. The other men waited while the man moved his legs from the car to the desert dust.

He stood no more than the height of the purple roof and considered me. A sparkle under milk-bottle glasses, and though the temperature had to be in the high twenties a black beanie so full of red dust that it looked rusted to his head, ripped and faded green shirt with buttons missing from the pockets, red dust coloured white cotton trousers held up by a thin black belt, and Dunlop Volley sandshoes that he wore as slippers.

‘Already heard ’bout you long way back. You bin walkin’ long way,’ and he paused, ‘You all right.’ A statement. I was instantly glad I had taken the time to secure permits for Aboriginal land. I tilted my head to a shady place a short walk away where I could start the fire and we could talk. He smiled and said ‘After you.’

I tied the camels off, started the fire and set the billy to boiling. I apologised to the young men that I only had two mugs. They shrugged and one said ‘No worries.’ Another returned to the vehicle to search out some mugs while the rest sat a little away, at a respectful distance.

I sat in the red dust next to the old man and we introduced ourselves. Jimmy was from Docker River and had just come back from a visit to Uluru. ‘I been watchin’ em 40 year an’ I still don’t know why whitepela wanna walk up ’im,’ he said, shaking his head gently, referring to the thousands of tourists who lean into the rock and walk to the top.

He asked me whether I had ever walked to the top. I hesitated for a moment and told him of my work with the Aboriginal Land Commissioner in the mid-1980s. I said that at the time I had asked an Aboriginal man what he thought of people walking to the top of Uluru. That man also said that he didn’t understand it at all. He said it was because white people needed to be on top of things all the time they felt they had to do it. So I did not.

Jimmy told me he had heard about the incident at Curtin Springs and that I had come with the camels across the Simpson Desert. ‘You come long way, eh?’

His voice was tobacco, whiskey and long draughts of sweet black tea. His tongue was fat and lingered near the roof of his mouth so that his consonants were warm and flat. Jimmy slipped off his shoes and began to wriggle a white rheumy toenail into the ground. I found myself drawing my fingers across the surface of the red dust, warm and giving to the touch, the grains parting under my fingers leaving gentle curves and ridges. I was feeling the curves and the contours, feeling the grains against my skin.

We watched each other for a moment and gently smiled. We had been doing the same thing. Reaching for the land, needing to touch it and feel it against our skin. The billy was on the boil and I began to make the brew.

Just before a sugary sip he asked, ‘You like camel?’ I smiled and said that camels were wonderful animals, friendly, trustworthy – though I didn’t mention Chloe’s snakiness – and a great way to move across the country, to feel it, taste it, hear it and even if for only a short time, be a part of it. He nodded, and turned to me again.

He paused for a moment and said, ‘I know that one camel lady. You know?’ I said that I did know that a camel lady had been along this way 20 years before. He looked away, shook his head gently and said with a low throaty laugh, ‘Funny one, that one.’ Jimmy told me that the ‘old fella’ who had gone with her was his cousin. His cousin had told him that he had to accompany her on the track to make sure she didn’t stumble on men’s or women’s business, or get lost. After all, it was his country and he was responsible for taking care of it. He was quiet then, and looked into the hot coals.

I took a sip of the hot sweet brew and thought about whether he wanted someone to accompany me across his country. This was not a question I wanted to ask. It might be difficult for Jimmy to answer. He would want to find a way to look after the land and my feelings at once. I watched his feet for a while and his big toe as it burrowed into the ground.

He put his hand on mine and said, ‘You be all right. I know ’bout you. You got country in you and there’s a little bit of you in the country.’ We shared touch, texture and warmth; we shared too the ground on which we sat and the need to touch it. And he smiled, the warmest most open smile I had ever seen. In that one smile he summed up friend, welcome and homecoming at once. That one action was a vindication and a validation of all I had set out to do.

Jimmy told me stories about the land and its people. He described how, in one Dreaming story, the Possum moved across this country and met with the great Dreamtime Serpent. As he did so his arms pointed to the rugged red escarpments around us, and a moment later one finger carefully described curves and circles in the red sand at his feet. As he told his story the past was immanent – everywhere around us – and time seemed to swim before my eyes. Time was no longer linear. It became a plane on which any story was possible, where wooden ships were pulled by white clouds and the men on them were the objects of curiosity for the Dreamtime animals of Australian Aboriginal lore.

We sat there quietly for a while, listening to the bursting coals, the rush of a desert pigeon, the slurp of warm sweet tea being drunk by the young men and the peace in each other’s company. We were layers, just points in time. There were people before us at this spot, as there would be people after us. And because we were there, on the country, touching it and it touching us, we became part of it and its history. Without touching the land, without being a part of the land, you could never know it, which was why, when people left the land they lost a part of themselves and the land lost a part of itself. Jimmy reminded me that if a person did not have a relationship with the place they lived in, they were tourists, invaders, exploiters or worse.

We sat together for hours, talking about the land, its people, the young men and women, the rubbish children, the problems of petrol-sniffing and alcohol. He spoke of the land’s meanings, its sacredness, and watching him and listening to his stories I was reminded of our need to create and our craving for immortality through story and meaning. I was reminded too that thought shapes place and creates meanings where there was nothing before; just land and sky.

Too soon Jimmy said he needed to leave for Docker River. His wife was waiting for him. He passed his mug to me and we stood. As he made to slip his feet into his sandshoes he stumbled and I caught him, my hand on his back. The young men started and sprang forward to lend a hand. Jimmy put out his arm and said, ‘I’m orright.’

I remember the touch of his body, firm yet frail, warm and enduring. The touch of his body was like the land itself.

The young men thanked me for the tea and said goodbye to the camels hooshed down in the shade. Little Dalhousie watched them closely and even allowed one to scratch under his chin. At the Holden the young men piled into the back and Jimmy took his place in the passenger seat. We shook hands again and over the sound of the engine starting up he simply said, ‘Thank you.’ I could never forget the thump of the cylinders as the car headed west along the track, black arms outside, hands reaching for the country.

Next day we camped just short of the turnoff to some prefabricated houses on the road to Lasseter’s cave, another 500 metres or so to the south-west. There was plenty of good feed for the camels and even a water trough from which I could wash and the camels drink.

Once the camels were settled I paid homage at the cave. What a country! To have entered it as Lasseter did, without knowing the location of water, or even more remarkable, move through the country knowing that there was a risk that water might be impossible to find, must have been daunting. The search for gold drove him hard. Certainly there was water in some rock holes and there were natural springs. But the time it must have taken to find these!

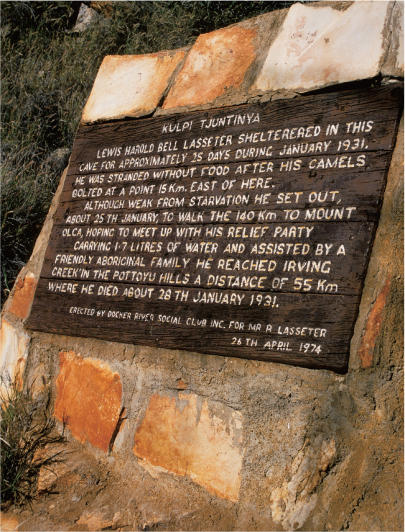

In 1930s Australia, Harold Lasseter’s story attracted nationwide attention. He had been looking for a gold reef that he swore he had discovered on an expedition years before. Many people did not believe him and some refused to continue on the expedition with him. So he found himself at this place. Without the assistance of the local Aboriginal people he would have perished far sooner than he had. At least he had a chance to survive.

The cave was some three paces wide and six deep, with the cave roof dipping sharply down after two. Much of the rock had been darkened by smoke, the campfires of many people over a long time.

The cave mouth faced west and as I hunkered down in front of the cave I wondered what Lasseter thought during the 25 days he sat waiting, thinking about what to do next. He died at Irving River 55 kilometres away, after his camels bolted, trying to make his way to the small settlement at Uluru.

Memorial outside Lasseter’s cave.

Later in the afternoon, as we moved along, I wondered at the heat of the centuries that bleached out much of the colour of the land forms, the hills and ranges and ground. So much colour of the land was now provided by flowers, yellows, blues and reds. Later, I found myself singing old Foreign Legion songs to the camels and the country. I was caught up thinking about the past and how dark things could infect the present and the future.