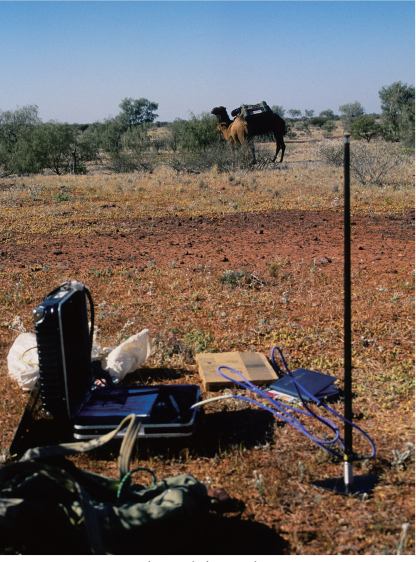

Dalhousie loves Kashgar, sniffing and rubbing anything that smells of her. With Kashgar unconcerned in the background.

8 To the Coast

– 25 September 1998

No mountain ranges, no rivers, no lakes, no pastoral lands, nor mineral districts has it brought to life; where the country was previously unknown it has proved only its nakedness; nevertheless I do not regret one penny of the cost or one minute of the troubles and labours entailed by it.

David Carnegie, 1898

We left Carnegie Station, named after one of the last explorers through Western Australia in the nineteenth century, late in the afternoon and camped not far from the station. We arrived there the day before, around 2 p.m. About four kilometres before arriving at the station I met Peter Buchanan, who told me he was a veteran of Korea and Malaya. He’d been out collecting wood for the donkey – the Outback hot water system.

Less than an hour later I saw the house, the first after weeks of walking. I realised that the prospect of nocturnal visitors, of teeth and screaming and fear was over. The camels could eat and rest and I could at last sleep through the night. As we came closer to the house I was struck by the presence of so many young trees. Citrus and ghost gums around 10 years old.

As we I arrived at the whitewashed front gate my knees were weak and my heart thumped harder. I turned to Kabul, caressed his nose and whispered a question into his twitching ear, ‘Have we done it?’ He sighed his fragrant sigh into my face and I kissed him under his wet left eye.

We were met by Faye Smith, who stood beside the gate in a floral print dress with her hands clasped in front. I wanted to embrace her and cry and sing with happiness and relief. Instead we shook hands and I introduced myself and each of the camels.

Faye invited me to lunch and later in the afternoon I cleaned and repaired gear. The camels were tethered just outside the house paddock, to the south of the front gate. Later in the evening I met some of the other workers and Faye’s husband Ian, who told me that Carnegie Station was the subject of a Native Title claim by local Aboriginal people. ‘Mate,’ said Ian, ‘there haven‘t been Aboriginal people out here for more than 50 years. What do they know of the land? I know its secret places, those dips and hollows where water might be. They don’t. How would they do on the land without me?’

Faye gave me mail that had been forwarded for me to Carnegie. There were letters from my parents and from friends a birthday cake which I shared with the Carnegie people. Faye smiled and said that I would be better keeping the cake for myself. ‘You look like you could do with some fattening up,’ she said gently.

Two nights from the homestead we camped about 10 kilometres past the Glenayle Station turnoff. So I guessed about 40 kilometres out of Carnegie Station. The days were getting very much warmer, and the light breeze from the west and north-west sucked the moisture from my cheeks. The country was red brown gibber stone with golden shadows of spinifex and shallow creek beds cutting the track. There were far more emus and kangaroo here than out in the desert. This was just west of the country that David Wynford Carnegie and his expedition passed through on their 1896 return journey to Halls Creek from Coolgardie. Carnegie was the fourth son of an earl, and an adventurer. After education as an engineer and a stint on tea plantations in Ceylon he joined the rush to Coolgardie when gold was discovered in Western Australia in 1892.

Though full of energy and passion, Carnegie was so ignorant of the land he resorted to capturing Aboriginal people, tying them up and feeding them salted beef until they revealed the presence of water. One such spring, named Empress Spring by Carnegie, was hidden 25 feet underground in a cave with a small entrance and not rediscovered by Europeans for 70 years.

Carnegie left Australia shortly after his expedition, was feted by the Royal Geographical Society in London, and appointed Assistant Resident in Nigeria. Here at the age of 29 he was mortally wounded while attempting to capture a criminal, struck in the thigh by a poison arrow. His was a life that flickered, just briefly, with an intense flame. I wondered if, as he lay dying, he thought it was worth it.

At the place we camped there was a 30 metre ghost gum, a hot summer’s sentinel, just a square leg away from where I rolled out the swag, across the track from Johnston’s Water. A few metres from Johnston’s Water was Mingal Camp, a covered camp with stove heater built by the people of Wongawol Station, next station from Carnegie, who used the camp when they were out mustering cattle.

I was up in the early morning, the flies already batting their wings against my cheeks, searching for the moisture in my eyes. There were so many flies that for the first time since the Simpson Desert I went in search of the fly veil and put it on my hat. In the course of the day I met Kimberley John, so-called because he had worked in the Kimberley of north-west Australia, station owner Spencer Snell from Wongawol, and later in the day his wife Gloria. The generous Gloria invited me to stop over in the station buildings at Wongawol. Everyone was on their way east to Carnegie Station to help with the mustering of cattle.

When I packed up the following morning I counted eight centipedes up to 20 centimetres long in among the blankets of the swag. They were of the blue green variety and the colour reminded me of the ties around sacks of potatoes. Later in the day the wind picked up. If I dared to open my mouth the moisture evaporated and my tongue became dry felt. With my head down and the elastic of the fly veil around the crown of my hat, the veil flew off and I gave it up as lost. I was too tired to give chase and anyway. With the wind blowing as it did flies were not a problem.

We got away early from Johnston’s Water where there were great mobs of emus, up to 15 in one group. To the north-west, Desolation Hills lay squat and malevolent, monochromatic, bleak and lonely. They looked a place where a person could die and never be found, a place where dingos, birds of prey and ants would consume the flesh and disperse the bones.

Late in the afternoon we camped at Jackie Junction, 27 kilometres from Wongawol. Just before I went to sleep with my head relaxed on the canvas pocket of the swag, I felt a sensuous caress on my neck and jaw, a hundred soft caressing prickles. I turned on my headlamp to see legs and the biggest huntsman-like spider I had ever seen. A flick to a bush nearby and I went back to sleep. How could I worry about something that was not venomous?

Dalhousie loves Kashgar, sniffing and rubbing anything that smells of her. With Kashgar unconcerned in the background.

The Snells invited me to stay in the single men’s quarter, where the stockmen Keith and Kimberley John had their beds. The camels stopped in the house paddock where the generosity of the Snells saw them plied with hay. The last they did not bother with, preferring the lovely weeds that grew in profusion across the paddock.

The Snells told me they had inherited the property from a spinster aunt who died a year or so before. Estate problems saw to it that ownership took a long time to sort out. The station had originally included Carnegie and Wandidda and was built around the turn of the century, not long after David Carnegie had moved through the area. The original homestead was just three rooms and built of local stone with firing ports, one of which opened to cover the old well that had been dug by hand. According to Spencer there were at least two Aboriginal men killed around the old house. One had been shot near the well, the other had approached the house holding a spear against his leg and was shot.

I went to the old homestead and walked inside its walls. It was shaded inside, cool, with its history and memories tangible in the narrow firing ports and the stone bases of water tanks clearly evident inside the house. It had been designed so that the station people could hold out for some time if the house came under siege.

I was glad the old house had been kept standing. It was testament to a very different time, of hopes, fear and conflict, distrust and death. Over dinner that night the Snells told me that they had to be on Wongawol because it was part of their family. Spencer said that they had a responsibility to look after the station and care for the land and everyone nodded in agreement. It was a responsibility that came with the family, they said. It was in their blood and could not be denied.

At the conclusion of the next day, camels and I camped 25 kilometres along the track. It was so hot that the dirt track rippled and buckled into the horizon. I drank all the water I carried on me and by late afternoon had a headache that beat against my skull. What breeze there was came from the north, and it drove the brittle dust into our faces. The small radio told me that the forecast for the next day was for isolated showers clearing to the east. I hoped the forecast was right. There were just l90 kilometres to Wiluna.

As I sat on the swag that night the wind picked up from the north-west, heavy with moisture and the expectation of a storm. I felt the dust stick to the grease of my face making a gritty crust. Just after I had unrolled the swag and lay my bones in the sleeping bag the winds hit. Then the winds accelerated and blew hot fireflies from the campfire as it drove in from the north-west. I left the shelter of the swag, pulled on my boots and by hand doused the fire in sand. Watching the embers being blown into the night I had no doubt the wind and live lights of fire could have started a blaze capable of sweeping across the land.

By next morning the weather had changed. A gentle breeze blew cool from the south-west. The camels were happy to be up and moving as there was little feed for them to pick. We moved past Little Banjo and then Banjo Well, beyond a salt lake with some water in it, and earlier than normal stopped at a terrific patch of a favourite camel food of mixed weeds, pigweed and low shrubs. It was not the sort of smorgasbord I thought we should pass up. As I did every day, after the routine of unsaddling and setting up camp I watched my friends and marvelled at their ability to eat. It seemed to me that a camel could eat enough in half an hour to change its profile, from a lean machine of labour to a plump bellied vegetarian.

We were fortunate to camp where we did as only a few hundred metres away the country changed and there was little feed for camels. We arrived at abandoned Yelma Station, noted on my map as Outback Bore, in the morning and after a drink moved off quickly, the camels made nervous, their eyes wide, by the squeaking of the windmill.

Though the day’s temperature quickly rose, the breeze from the west-south-west was just enough to take the edge off the heat. In the afternoon I stopped to look at a shaft of an abandoned gold mine near the track. I told the camels that if they should fall down they would never be found. If little Dalhousie did not understand my words, he understood their tone and kept well away. Maybe too, he had learned from his adventure in the rock pool.

I looked down the shaft into the shadows and marvelled at those who had come to this place to search for gold. Not only was this place remote from Wiluna, the ground was concrete hard. For men with little more than picks and shovels it must have broken backs and hearts.

We left the pastoral lease of Wongawal Station early in the morning. We passed Leeman’s Bore just off the track to the left, the last bore on the station. For the calcium they gave, Kabul and Chloe chewed some kangaroo bones along the way and we moved on to Lake Violet Station, de-stocked and run by a mining concern. We met Keith and Kimberley John on their way into Wiluna for a ‘blow’ – a drink and a general relax from the pressures of the station. In the afternoon I waved to Ian Smith driving back from a shire council meeting in Kalgoorlie, more than 600 kilometres from Carnegie. It was what people here did – long drives to do the things they believed they had to do.

We camped in what I thought was a reasonable spot up from Mitchell Bore, located on the third cattle grid on Lake Violet Station. It was the home of the scorpion and as I sat to write up my diary I felt fine-haired caresses on my leg and flicked three into the dust. I wondered if I had disturbed a family.

In the middle of the morning next day we met a very ‘second-hand’ Keith and Kimberley John coming back from Wiluna. They had enjoyed a big night in town. Not unexpectedly, it was etched under their eyes. They told me it would be the last for at least six weeks, during which time they would be out mustering.

Later we met Phil from Prenti Downs cattle station who was taking two new female workers to the station. One was a 20-year-old, very pale with dyed black hair. She stepped from Phil’s four-wheel drive and immediately began to slap on sunscreen.

The second had an accent of the US West Coast. Over 40 I supposed, bottlebleached blonde, a tattoo burned or skin-grafted off her left upper arm, with two more, one melting into a dark web on her hand and the other on her forearm; two flags, I thought. She insisted on ‘working the camels’ but had no idea how to do so. After I introduced the camels, she snatched at Kashgar’s lead rope and shouted ‘Down girl! Get down!’ I asked her to stop because Kashgar became unhappy, with a bellow and a beseeching look in my direction.

The woman’s aggression bled into the air around us and the camels. As I took Kashgar’s rope from her hand I told the bottle-blonde it was best to leave them be until they got to know her. She narrowed her eyes and told me she wanted to walk from Coolgardie, in the southern Western Australian goldfields, to ‘Ayers Rock’ with camels, but had been refused permission by ‘bloody Land Councils’. She said she wanted to be just like the camel lady.

I told her that all she needed were some camels, some gear, some maps, a rifle and lots of patience. I told her that times had changed and that it was necessary to secure permission to enter Aboriginal land. After all, it was theirs. ‘Bullshit,’ she said, ‘the Aboriginal people don’t want to keep me out, it’s the white men, the damn administrators.’ I wished her luck and Phil winked at me and left his hand in his pocket too long. The two women turned away from me and got back into the vehicle. Phil left me a smile.

Like the people we met, the country changed all the time, from sand to clay pan to salt lake to breakaway and then to hard ground. We camped in a good spot for camels with plenty of feed. There was a full moon and with it, for some reason inexplicable to me, mosquitoes that whined around my head and made the camels snort, stamp and sigh.

We were just 25 kilometres east of Wiluna and I was emotionally and physically exhausted from having to put up with pain all the time; in my back, my legs – in the consistent jarring movement. Was it masochism, masculinity or the drive to achieve that kept me going? I was utterly fixated and obsessed with reaching my goal. There was no doubt about that. The real question was, at what cost? The only time the pain stopped was when I was on my back in the swag. How tempting it could be to ignore a check of the tethered lines or a look at the camels because a sixth sense told me to. But I never ignored the impulse to check them. Maybe that was what made things so hard. Never a rest from them. Never a time when I could truly relax.

Even so, there were compensations. As we moved along I looked back at the three, Dalhousie off to one side investigating a bush, and there they were in line abreast. I felt my heart swell; it was for love of these three and their calf. They were so very different in temperament, but when I said go, they followed. And followed beyond what I thought was possible or reasonable to ask. I knew that when the time came I would miss them very much.

The track into Wiluna took us past an Aboriginal outstation of corrugated iron and paint-peeled weatherboard homes where the people did not wave or laugh. They kept their heads down, as if a great load weighed heavy on their shoulders. The only sounds were the lonely banging of a door on its frame and the yelp of a dog.

Walking up into town we were met by Wiluna’s children. It was school holidays and news of our arrival spread fast. All were Aboriginal children in colourful clothes, smiling, clapping, cheering and coughing. Little fingers pointed at my friends. Dalhousie stayed close to Chloe. I told my new friends we had come from the desert where the sun comes up. Little faces frowned and lips were pushed up to noses and viscous green snot stuck. ‘Never been that way,’ they said, ‘Never seen camel before either.’

I asked the children to take us to the local caravan park, a place where I could camp, tie up the camels and let them feed and rest for a day. Little black hands reached for mine, and others for my shirt and my pants, just to touch me, help me along the way and make sure I did not get lost. Our escorts took us past shells of houses where shiny black bodies with forearms over faces lay on a car bench seat in the dust, and dark moving shadows were crows.

A sign on the caravan park perimeter fence, with its barbed wire and three metres of mesh, said: ‘park gates are locked between 6pm and 6 am’.

I clipped the camels to trees opposite the park, and following some inquiries camped outside the caretaker’s residence, the camels enjoying the grass and rolling in the dust. I reported to the police station, handed over my rifle and gave them what rounds I had left. They told me I could send the rifle home if I wanted, so long as the breech block or bolt was sent in a different package.

After washing clothes and cleaning gear, I made my way to the Club Hotel, the only pub in town, with a convenient gate providing for entry from the caravan park. I asked how to get to the front bar. The barman paused from his wiping the bench and said, ‘You don’t want to go in there. There’s coons fighting all the time.’

I went anyway and found myself in the front bar, a large dark room, slivers of light in the ceiling and beer served through slits in a grating. The place was concrete and reminded me too much of a prison cell. I could not ask for a beer here and was appalled that people could live and drink in a place where they were fed alcohol like prisoners. My shoulders slumped and my body sagged, limp in the knowledge that people should be so complicit in their own humiliation and fall.

He must have seen the sadness in my shoulders and I felt a wide warm hand on my back. ‘It’s all right,’ he said. ‘You drink in the other bar and we do our things here. Better to be separate sometimes.’ His warm hand walked me out to the evening light where broken black noses were slouched against the pub wall. A few metres away, across the road, ‘glass hill’ was a shattered brown diamond mound of smashed bottles and stubbies. His warmth and care for me only made me feel even worse.

I sat at the whitefella bar and ordered a mixed grill and a beer and watched TV for a while. I made my way back to the caravan park through the hotel’s garden, checked the camels and hit the swag. Though I had now crossed the Simpson and the Gibson deserts, I did not feel like celebrating, in fact I felt sad as hell.

I felt the camels stir before I heard the screaming and the threats of violence. The alcohol-fuelled arguments went on through the night, as did the smashing of bottles, screams and once or twice a devastated lonely whimper and a sniffle. I wondered if many people in Wiluna slept.

It was a night of dislocated obscenities and finished people; a people whose spiritual and emotional link to the past was language and land. That link, that umbilical cord had been cut, and they no longer had the fuel and food of their history, their language or their stories. Even worse was the knowledge that, once lost, it could not be passed on to their children. Their food did not have its roots in the red land, or the crystal waters of the rock pools. Instead, it was an amber transfusion, beer from the Club Hotel, where knowledge of loss and dislocation was numbed and the only way to express a present hell and a future without hope was through stupor and violence.

In the hour or so before dawn I slept and was woken by small voices asking, ‘Hey camel man, you all right?’ I folded back the canvas flap to see two small boys, bare feet, shorts, T-shirts and thick black hair. Jerry had a large bottle of coke in one hand, the fingers of his other hand wrapped around the mesh that kept him out. Billy watched me with enormous black eyes while he munched his way through a large bag of crisps.

I asked them if they were eating breakfast and they nodded seriously. I left the swag and prepared for them both a breakfast of muesli and honey. I sat watching both as they chewed their way through the dried fruit and bran. They did not seem keen on the breakfast. ‘Too long chew him up,’ Jerry said.

I spent the day on the telephone, calling Amber and a number of radio stations. Tears filled my eyes when Amber said she was proud of me. Radio stations had to fit me into their schedules so I waited for a long time by the phone. While I was waiting I met Kerry, known she said as the Dragon Lady of Wiluna. She and her husband Ken, who had been in the army, were the publicans of the Club Hotel.

As I stood waiting for a call on the public phone, Kerry told me what she thought about the Aboriginal people in Wiluna. She told me how, after pension day, she made sure that mothers bought food for their families before coming to the pub. She pointed to the American Indian dream catcher above the phone and said that there were more live legends and languages in the United States than here in Australia. I asked her how could she be so sure?

‘David,’ she said, ‘have you looked outside today? These people have ruined themselves. I don’t make them drink. I don’t stop them from going back to their country. Isn’t the government going out of its way to give land to Aboriginal people who want it? No, I’m not taking any responsibility for what’s outside. Why should I?’

A day later I left town and saw what I had not noticed before. Over the door to the front bar, the Aboriginal bar, Kerry had painted ‘Welcome to Paradise’ in rainbow colours flanked by two tropical palms. Across the road ‘glass hill’, the smashed, shattered glass was covered with a hint of dew so that it looked like a mound of dirty frozen teardrops.

I could not get out of town quickly enough.

Next morning I was woken well before 5 a.m. by flies pricking the sweat around my face. I poured some water into the billy to make a cup of coffee and was greeted with a whiff of chlorine. This after only two days in jerry cans. Even the water from Wiluna was bad and I wondered if it would last the four days to Meekatharra.

Two days later we were only 20 kilometres to Meekatharra and we were met by John and Leah Bryant, with whom I had shared a coffee at the caravan park at Wiluna. They asked me if there was anything I needed in Meekatharra. On a moment’s reflection I said that all we needed was a place to put the camels.

John and Leah told me later what they had found. They went to the shire council where men in creased white shirts told him ‘in no uncertain terms’ that there were to be no camels in the town. Then they visited the police who were apparently surprised by the council’s refusal, then to Elders, the cattle and camel feed people. The Elders people said I could put the camels in the cattle yards just out of town, which solved my immediate problem. They even said they would drive me out some lucerne hay for my friends, which anticipated and solved my second problem. John and Leah did not have to help me. In fact it was probably quite inconvenient for them to do so, but I was grateful they did and I told them so. They even brought out a chicken and chips takeaway pack for lunch. It was salty, greasy and quite delicious.

As we made our way into Meekatharra, the hills around made it very clear it was a mining town. It was apparent from the bleached red and orange heaps of earth from under the earth’s skin, tens of metres high across many hectares around the town, insulating it from the flat and scrub of the inland. The heaps were devoid of vegetation or life, just colours of the land that had been in darkness for thousands of years.

I turned the camels into the cattle yards just out of town, piled their loads into another empty yard and left them to enjoy bales of lucerne hay. Taking a small bag that held a change of clothes and shaving kit, I walked into town and checked into the Commercial Hotel.

Following a shower to sluice my body clean of dust, I descended the steps to the front bar of the hotel. Here I met Les Baker. Les was at least 70 years old and had lived in Meekatharra for 47 years. He told me he was on the last truck run from Carnegie to Wiluna and the train that used to run from town to the coast. The barman at the hotel gave Les cheap beer. As we sat there in the early afternoon Les said, ‘Yep, I guess this bar is the only real home I have.’ He was quiet for a moment then I bought him a beer.

As I lay on the bed in room 1, I could not sleep. I wondered what the camels were doing. I could not breathe properly, I felt as if the walls were closing around me. The air was too close and I could not see the stars. I needed to be outside. With a creak of the bed springs I went to the window, drew the flimsy curtain open and looked to the night sky. I only went back to bed as the stars began to fade and melt into the light of day.

In keeping with the formal requirement that animals moving across state boundaries be checked by vets, Chris Brandis of the Western Australian Agricultural Protection Board ran his hands over camel bellies and gave them a clear bill of health. Indeed he seemed to think they were the healthiest, happiest camels he had seen in some time. The lucerne hay was just the thing. They were looking fatter than ever before, even Chloe with an always hungry Dalhousie suckling from her. Chris showed us a route out of town and late in the afternoon we camped opposite Opal Mountain about l5 kilometres out of Meekatharra.

We were slow in leaving town. First, after settling up the feed bill, a long chat with Richard from the Elders feed store whose brother was running Mileura Station on our way to the coast. Then, and as we were saddling up, we were joined by Chris Huddle who lived in a small shack at the cattle yards, who used to be a dogger. Chris said that even now a dingo scalp was $40.

I wrote up my diary as the rice was on the boil. It was a tuna mornay night. While I had some time I double checked our route and distances. I found that as of just short of Belele Station we had 700 kilometres to Steep Point. This meant we had to average just under 30 kilometres for the next 27 days by which time I wanted us to be at Steep Point.

It was an early start next day and we made it into Belele homestead, the whitewashed building made of locally cut and carted stone, with a billiard table green and smooth lawn of couch grass and kikuyu, just before midday. I had lunch in the kitchen and sat at a large table with Brett, Coralie and the station hands. Brett and Coralie Smith managed the property for the local Aboriginal Corporation.

Lunch was marvellous, lots of sweet lamb and I felt very good all afternoon. I also had the chance to change the dreadful water secured at the Meekatharra cattle yards. As I sat outside the kitchen filling jerry cans and trying to recalculate the distances, I decided that 700 kilometres did not seem right at all. The track we were on was marked on the map as the primary route to Mileura Station. In fact a new track, exiting the northerly Carnarvon track, headed west 25 kilometres further north from Belele homestead. All this meant that I reckoned we were now 583 kilometres to Steep Point and I breathed a sigh of relief.

We camped on the Mount Hale Road, a dirt track about l5 kilometres along from Koonmarra Station. At Koonmarra we met Maree Brosnan, her daughter and kids. Maree was not at all keen on letting me through her place to take a short cut. Not that I blamed her. As she said, they had not used those tracks, my intended short cut, in the five years they had been on the property. I nodded, told her I understood, and undertook to follow the usual track north toward Mount Hale and west to Mileura Station.

It was a small world. Over biscuits and a cup of tea Maree told me that Snowy Brosnan, her husband, used to work at Wongawol and knew Margaret Donovan, the spinster aunt who left the property to the Snells. Certainly it was a hard land, but those who knew it came to love it and they stayed.

At the end of the day’s walk I looked at the map, took out a pencil, and reckoned we did almost 40 kilometres, so that we were just l0 kilometres short of Mileura homestead. The track had come out at Nama Bore where a road sign on a windmill vane marked ‘Mileura 27 kilometres’. As I sat on my tin that night, watching the flames lick the wood, I wondered at my fixation with distances. Sometimes I thought numbers the most important thing in the world, and I knew that I had become a little mad.

I met Patrick Walsh next morning. His brother Richard told him we were on our way. Patrick was the only person working Mileura Station, over 250,000 acres of mixed sheep and cattle. His family had owned it for generations. Patrick offered me a cup of tea, gave me a tour of the homestead and told me stories about the past. Just inside the front door was an old oilskin jacket that had a rust stain on its front. Patrick told me that the coat had been the bed of a baby born decades before to one of the Aboriginal women who lived on the station. ‘It’s a reminder of where we come from,’ said Patrick, ‘a raw place where we help each other when we can.’ He agreed to meet us that evening at our camp on the track west.

That evening I sat on the swag watching the fire, the only sounds were camels chewing their cud and the sighs of the mulga under the flame. Patrick pulled up just on dark. He took off his hat and put on a cap. He reached into the tray for a small esky and groaned, ‘Me back’s buggered, but don’t you try to help me.’ He put the esky beside me then leaned forward and cocked his torso over his left leg to rest his lower back damaged from falling from too many motorbikes. He shuffled a little and sat down. His fine red hair was the colour of the fire, his eyes the sky five minutes after sunrise, alight alive and imbued with the energy of a new day. His hands freckled and scabbed, like so many ants stuck to his skin. Patrick Walsh was 27 years old.

He looked into the fire and told me of his great-grandfather, who had ridden here from Perth, over 500 kilometres away. Patrick said that his grandfather stood to the west of the great bowl that he named Mileura Station and decided it was here he wanted to create a family and raise his children.

I asked Patrick what his plans were for a family, and briefly, the dark smudges below his eyes appeared to grow darker. He said, ‘It’s hard to get a good girl out here. They like the city life and it’s difficult for them to get settled unless they’ve come from it.’

Patrick was thoughtful for a moment and changed subject. He talked about the fires, the floods, the loss of family and the droughts. ‘Sure it’s hard sometimes,’ he said, ‘but where else could we go?’ I asked him how much the property was worth. Well over a million dollars he reckoned. And how much did the property return last year? ‘All up we paid ourselves about $20,000,’ he said. I told him that I was no accountant, but that such a low return was not much good for any investment.

He looked at me and said, ‘Sure you’re right, but that’s not the point. We have to live here. It’s our place. Who else would look after it properly?’ He sat on my food tin, leaned forward and scraped up into his hands a little of the red dust at his feet. He sat back and gently rubbed his hands together, savouring the texture, his eyes closed for a moment, concentrating to feel every grain as it touched his skin. He let the dust fall to the ground and as the last grain joined the others he asked, ‘You know what “Mileura” means?’ Of course, I had no idea. He said, ‘It means “see a long way” in the local language.’ Patrick was quiet then, and we sat together, not saying anything for some time.

Setting up the mobile sat phone.

I loved Patrick Walsh for his various hurts, his scabs and his serious concerns. In one way, he was like a soldier, permanently on patrol of that place that was his responsibility. In another way he was a warrior priest guarding the past and its significance for the future. I loved him and envied him because his life had meaning beyond the dollar and necessary return. His life was rooted in the land, in place and its stories. My world told me I was to work to consume, consume as much as I could, and then die.

Patrick Walsh – Mileura Station.

We were away just after 7 a.m. next morning and did not set up camp until 6 p.m. – just after what my map told me was 7 Mile Bore or about five kilometres short of Berringarra Station. The day was full of a light drizzle rain and thankfully cool. We walked through the Jack Hills, according to Patrick some of the oldest stones in the world, and from a low saddle could see into the great bowl of Mileura Station.

That evening I ate spaghetti bolognaise for what must be around the one hundred and fiftieth time on my journey. The tuna mornay did not have enough fat in it. I began to think about some of the other things Patrick told me. He said that the original homestead could be found along Poonthoon Pool. The house was moved to its present location as the old homestead was too far away from the centre of the station.

Patrick also said that there were two Afghan graves on the station, the men buried with gold sovereigns in their mouths. ‘That’s the way they did it back then,’ said Patrick, ‘and we’ve left them in peace and intend to do so. They are part of the history of the land now.’ The Afghan men worked the camels that carried fencing equipment, food and people to outlying parts. Patrick had taken me to one of the sheds where he showed me the old camel gear, still in good condition.

On the track next day we met Wendy Penn, from Mount Gould Station, who told me how delighted she was to see the camels. Her grandfather had a station to the north and used to run camels to Meekatharra. She told me she loved to open the photo album to images of her grandfather breaking in young camels.

That night, with the brew mug in my hand, I spilt a little of the precious liquid onto the sand. I watched the liquid spread through the grains and understood that I did not want to mark the land, blemish or stain it with anything other than my sweat and blood. I knew the only stain, mark or brand that would take place was deep inside me. Perhaps that was something we learn when we are truly part of the country. You don’t need to wear it; it is part of you and you can never forget it. Your country is as indelible a part of you as hope, fear and laughter.

We lunched at Milly Milly Station, passed through Byro Station and camped at Ballythanna. Crossing the dry bed of the westerly trending Murchison River I saw a metal plaque planted on the south bank, barely visible through the leaves. It marked the general location of camp l8 of John Forrest’s l874 expedition. The plaque was erected by the Geraldton Historical Society, a group of people who liked to mark and name things. I remembered that the expedition was Forrest’s third major expedition and he was not yet 30 years of age. He led the expedition from Geraldton on the coast to the Overland Telegraph Line just south of Alice Springs. From what I knew, his expedition was a close-run thing though he did, once and for all, kill off the notion that there was an inland sea.

Lying back on the swag I felt my bones melting through my back. In a tree not 20 metres away a small falcon was watching me. I could see its head swivelling, its bright dark eyes locked on mine. I could feel its power and I was so weak. I could not even remember the name of the next station when I must have looked at it 10 times.

When I looked up to the sky I saw the moon in its half phase. If all went well this would be the last time I would see it like that, and I was sure I would miss it. Only another l7 days or so till the end.

At Ballythanna Station, where we camped not far from the main house, I got to talking with Bill, the maintenance man. Bill let me use the station telephone to call Paul and Pam Dickenson, the rangers at Steep Point. In his British accent Paul told me that from the Useless Loop turnoff it was 78 kilometres to Steep Point. The first 50 kilometres were okay, the last 28 very sandy. No good for cattle trucks. Paul told me that once I got to the most westerly point I would have to walk the camels back to where they could be loaded onto a truck.

A plan had been forming in my mind. It was to truck the camels from near Steep Point to a station that would keep them until I could find a better solution. In order to keep them from filling cans of dog food I would even give them to people who would work them free of charge. The bottom line was that I wanted someone who would look after them and give them a good home. After all they had done for me it was the least I could do for them.

According to Paul and Pam, there were camels on the road to Steep Point and I would need a rifle. Apparently these camels were the descendants of those of early last century that worked on Hamelin Station. As to the rifle, I had sent it back to Canberra from Wiluna, little knowing I might need it again.

In the early afternoon next day the temperature was over l00 degrees in the old Fahrenheit scale. My body was screaming for water and I even had Kabul hoosh down so I could access one of the jerry cans of water at 4 in the afternoon. It was November at last, perhaps the last month of the great expedition. If we did not finish soon it would be too hot for me to walk during the middle of the day.

The heat outside was nothing compared to what was happening inside me. I felt myself wanting to cry again. Whenever I thought of a song, or a special moment, tears flowed. I was clearly in an emotionally fragile state. Not angry or sad but a combination of a very deep tiredness and a pleasant sensation of giving way to quiet sobs followed by tears. I was close to breaking point and I knew it.

We camped about eight kilometres short of the Princes Highway and a few kilometres along the track from old Woodleigh Station homestead. I took the camels in to the station bore to give them a drink. It was not long before I began to doubt my judgment. Loose tin flapped like the wings of ancient birds, fences were down, a windmill squealed, and wire lay loose on the ground to catch camel legs. The camels went to the water through a narrow passage next to a water tank, the yards shaded by large trees. They bolted the last 10 metres. After they had drunk the water I found I could not turn or have them out the same way.

Camels become tense then frightened. Dalhousie caught the general feeling and ran through one fence that had some strands missing. After an unsuccessful attempt at getting Kashgar along the passage I decided to take the fence down. In the meantime there was much concern at being fenced in. There was snorting, bellowing and flapping of ears at the squeak of the mill and the squeals of the selfish little camel on the other side of the fence. Kashgar bolted for the fence and to my horror was trapped. She screamed and writhed and after a few heart-stopping moments for me managed to free herself of the wire. Other than a couple of shallow cuts to her chest there appeared to be no other damage. Just two red stripes across her golden coat.

I brought the wire down and as quickly and calmly as I could I walked the camels through the fence, past the disused tennis court, the homestead with its dirty dusty windows and silver satellite dish, the meathouse, and more shaded ways till we got to the entrance to old Woodleigh Station and then to the Woodleigh – Byro road.

As we moved away I wondered about the tennis parties that once might have taken place there. I could almost hear the rustle of tennis skirts and rattle of ice in tall glasses of gin and tonic. We continued to the sea.