Chapter 6

“Your Noble Boy is No More”

The Union’s Brig. Gen. Ulysses Simpson Grant commanded the military district at Cairo, Illinois. Grant was also a West Point graduate (Class of 1843) and veteran of the Mexican War. After the latter conflict, Captain Grant was posted on the west coast, where loneliness and the separation from his family caused him to turn to alcohol. He resigned from the army and returned east to try his luck at a variety of jobs, including helping to oversee the slaves on his father-in-law’s farm in Missouri. Nothing seemed to work out. When war came in 1861, Grant was working as a clerk in his father’s leather goods store in Galena, Illinois, not far from Josiah’s home. Anxious to get into the fight to save the Union, Grant successfully secured the colonelcy of the 21st Illinois before being promoted to his current position.2

Grant, who would prove tenaciously aggressive throughout the war, believed the design and location of the two Confederate forts in northern Tennessee just below the Kentucky border—Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland—exposed them to capture. He received permission from Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, the commander of the Department of Missouri and Grant’s superior, to launch an expedition against the forts. The plan included working in conjunction with Admiral Andrew Foote, the commander of the Western Gunboat Flotilla. On February 2, 1862, the 17th Infantry, along with the other troops of Grant’s command, boarded river steamers and embarked on the expedition. Fort Henry was the first target.3

As the Union vessels steamed up the Ohio River and then down the Tennessee, the Illinois men watched the green lands of their home state pass. Years later, Frank Peats wistfully described their leave from familiar lands as they viewed “the quiet pastoral scenes of meadow and woodland, of cosy cabins and thrifty orchards, troops of boys partially dressed in ventilated panteloons, that gazed upon us with wide wondering eyes and bashful girls whose youthful beauty was half concealed in poke bonnets and primitive gowns that were unvexed with tuck, pucker, or bustle.” Peats also described what the journey was like aboard ship. “Our boat is crowded full,” he wrote, “blankets are spread on deck, between decks and on the cabin floors. Officers can enjoy the privilege of occupying the state rooms a rare privilege when we discover that the little 4x7 state rooms are bereft of all beds, bedding and carpets. Even the little dainty Cleopatra lace curtains have been removed from the windows, inviting all the ‘peeping Toms’ of the regiment to make observation.”4

The 17th, along with the 49th Illinois and two batteries of Missouri artillery were part of Col. William Morrison’s 3rd Brigade, in Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand’s 1st Division. McClernand was a Democratic congressman from southern Illinois, but he was also ardently pro-Union. A “political general” rather than a professional soldier, Lincoln had given McClernand his commission to help keep southern Illinois solidly aligned with the Union—to “keep Egypt right side up,” as the president put it. McClernand had a difficult personality and has been described as “irascible, overly ambitious, flamboyantly patriotic, and polemic.” As the war progressed he became increasingly alienated from the senior staff with whom he served, particularly military professionals such as Grant and William T. Sherman, later one of Grant’s chief lieutenants.5

Escorted by seven gunboats, Grant’s men reached Fort Henry on February 6. The fort was poorly constructed, flooded, and its guns improperly positioned when Foote’s vessels made their appearance. The river warships reduced the fortification with heavy shelling. Some of the defenders surrendered, but about 2,500 fled as fast as they could scramble away, crossing the narrow neck of land separating the two rivers to reach Fort Donelson about 12 miles away. A Union infantry assault to take Henry proved unnecessary.6

McClernand’s division waded ashore through waist-high water and deep mud and spent time investigating the fort’s interior and examining the prisoners. Frank Peats, who commanded Company B during the 17th Illinois’ first major field campaign, was unimpressed with the Fort Henry captives, who “stand together in a straggling group and present a sorry appearance, clothed in misfit butternut homespun, unwashed and apparently hungry.” Some Union soldiers picked through the abandoned enemy belongings. One member of the 17th Illinois recalled confiscating an eclectic list of items, including “two or three corkscrews, an antique cameo breast pin, half a pair of earrings, an Italian night robe trimmed with sable … two pieces of child’s coral, part of a set of false teeth (somewhat worn), one dessert spoon with the initials Y. B. D. plainly engraved, six pages of a manuscript sermon entitled ‘What Shall I do to be saved,’ a lady’s morning wrapper … one and a half pairs of high heeled shoes and one quilted Morrocco side saddle, just as momentoes you know.” On February 11, Grant sent McClernand’s division overland to invest Donelson.7

A postwar image of Frank Peats, who joined the 17th Illinois in April of 1861 as captain of Company B. He would rise to the rank of major and command the regiment at Vicksburg. Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

Josiah recalled after the war that the short sloppy march to Fort Donelson took place on “a beautiful moonlight night,” with the weather so pleasant and the air so warm that the men decided to leave their gloves and overcoats behind them. On February 12, the Josiah and the rest of the Union soldiers caught their first glimpse of the outer ring of Fort Donelson, behind which rested a powerful garrison comprised of about 17,000 Confederates under the overall command of Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd. If the Union men had been excited about the prospect of a major battle, the strong outer earthworks mounted with heavy guns surely gave them pause.8

McClernand put his men into motion toward the Cumberland River to block reinforcements to the fort and prevent the troops inside from escaping. The move ran into a Confederate cavalry screen commanded by Lt. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest. After some sparring, the Union troops pushed Forrest’s men aside and established a position along Wynn’s Ferry Road, about one mile from the fort’s outer defenses. According to Peats, the unit advanced skirmishers to within range of the fort while the rest of McClernand’s men strengthened their position. As nightfall approached, they scraped away “sticks, stones, and briars” to make places to sleep.9

The next day, February 13, McClernand continued shifting his troops east to complete the fort’s encirclement, and his men came under fire from the Confederate batteries of Graves, Maney, and French. McClernand had orders from Grant not to bring on a general engagement, but the division commander was anxious for a fight, especially since the navy had done all the work and received all the glory from the the fall of Fort Henry. He ordered an assault to silence the Rebel guns, targeting a portion of the outer works held by Maney’s Tennessee Battery and an infantry brigade commanded by Col. Adolphus Heiman. The Confederate brigade consisted mostly of Tennessee units defending their home state, with one regiment of Alabama troops. Morrison’s brigade had only two regiments available, the 17th and 49th Illinois, but orders arrived to make the charge. At the last minute, McClernand ordered the 48th Illinois from W. H. L. Wallace’s brigade to assist. The 17th Illinois took up a position in the center of the line. According to one eyewitness, the men were to “descend a hill entangled for two hundred yards with underbrush, climb an opposite ascent partly shorn of timber; and make way through an abatis of tree-tops.” Even if the attack reached the fort, the entire garrison inside was available to reinforce the point of attack.10

“The Soldier in Our Civil War,” by Frank Leslie depicts the “Gallant charge of the Seventeenth, Fortieth, Eighth, and Forty-Ninth Illinois regiments Led by Colonel Morrison, on the outworks of Fort Donelson February 13th, 1862,” by Henry Lovie. Frank Leslie

Shortly before stepping off, Col. Isham Haynie of the 48th Illinois asserted that he was senior to Colonel Morrison and ought to command the assault. Morrison replied that he would command the brigade until the assault began, and would then relinquish leadership to Haynie.

Peats maintained that the Confederate artillery did not molest the Union assault line until “our little command of three colors started forward.” At that point they were “saluted with shrapnel, shell, and canister.” The three regiments moved down the hill, struggling to keep their alignment through the heavy underbrush and moving forward with “bowed heads as though buffeting a storm.” They had to contend not only with the fire from Maney’s battery, but from the supporting guns of Graves to their left and French to their right. In the valley between their jumping-off point and the fortifications, “Morrison reported to Haynie who neither accepted nor refused the command,” but announced, “Let us take it together.”11

By the time the assaulting column emerged from the tangled undergrowth, any sense of orderly formation was long-since gone. The serrated line of men in blue continued up the slope as best they could to within a short distance of the Confederate line, when the five enemy regiments within small arms range opened fire. For about a quarter-hour the boys from Illinois traded shots across the smoke-filled field with the men inside the fort. One of the Confederate musket rounds knocked Colonel Morrison from his horse. Unable to capture the Rebel position, the Union men fell back down the hill.12

McClernand sent over another Illinois regiment, the 45th, which had no better luck. The men tried and failed a third time before withdrawing. According to one of Peats’s poetic descriptions, a charge pushed forward toward the fortifications “only to fall back in broken fragments, than reform and again sweep forward, as the waves of a troubled sea whose foaming crest climbs the rock bound cliff only to fall back in glittering drops, to mingle again in unity of purpose.” The Union wounded experienced a new terror when the battery fire ignited dry leaves on the ground and many helpless men burned to death, “their despairing cries for help adding a new horror to this pandemonium of hell,” wrote Peats. The Confederate troops inside the fort, who just moments before had done everything in their power to kill the blue-coated men pouring out of the underbrush, jumped from their sheltered positions in an effort to drag as many of the wounded as possible to safety.13

This affair was no Fredericktown. The 17th and 49th Illinois regiments suffered 149 men killed or wounded. Haynie’s command lost nine casualties. One source numbered the Confederate losses as 10 killed and 30 wounded, most of whom were artillerymen. McClernand described the failed attack as “one of the most brilliant and striking incidents” of the campaign, and claimed it would have been successful if the rest of the army and navy had provided support. Grant, of course, had told McClernand not to make an assault or bring on a general engagement before the resources to support such a thing were in place. Peats had an entirely different view of the charge, which he called “wanton, cruel, and heartless.”14

A cold front arrived during the night, bringing with it snow, sleet, freezing rain, and temperatures that reportedly dropped to as low as 12 degrees. The survivors of the charge suffered terribly, for not only had they left some of the warm weather clothing behind, but Grant had banned fires in the Union camps to avoid giving away their positions and drawing enemy fire. Charles Smith of Josiah’s company wrote to complain that the men went to bed on the bare ground without any tents and awoke covered in two inches of fresh snow. When he checked the guards that night, Josiah “found their hands frozen to their guns.”15

Despite these miserable conditions, some of the men of the 17th found the strength and vigor to taunt the Rebels the next morning. “Hello Johnnie, who’s dat knocking at de door?” they hollered. The men inside the fort replied in an equally feisty manner by inviting the attackers to “come over and see, you damned Yank.”16

That day, February 14, Grant had Foote’s gunboats attempt to repeat their success at Fort Henry by pounding Fort Donelson into submission. This fort, however, was well built and some of its guns were situated to fire down the river. The Federal warships were knocked back, and Foote was wounded in the effort. The Union infantrymen watched with keen disappointment as their hopes for a speedy victory were dashed.17

The cold and snow continued to bedevil the Yankees. Peats reported how some men in the 17th Illinois ignored the ban and built campfires to brew some coffee. A squad formed a small circle and built a fire on one side of a tree away from the fort, hoping to keep the flames hidden from the gunners inside. The effort didn’t work and a ball from a Confederate rifle zipped through the kettle, spilling the precious brown liquid on the ground. As men scrambled to scoop what they could into their cups, an artillery shell burst overhead, scattering the men and drawing the attention of officers, who hurried over to rail against the violation of orders. One enlisted man lifted his cup to one of the officers. “Colonel, won’t you take a drink?” he asked. “It’s danged thin but its like you—‘hot.’” To the dismay of the man who had offered it, the officer grabbed the cup and drained it dry. When the officer left, the soldier muttered, “[I]ts all well enough to talk about having confidence in your officers, but I’m hanged if I haven’t lost all confidence in that feller.”18

As daylight crept over the frozen ground on the morning of February 15, the men of the 17th Illinois found themselves on the far left of McClernand’s divisional line, which held the right side of Grant’s investing army. Only the guns of Battery D, 2nd Illinois, were arrayed beyond them. The right flank of Lew Wallace’s division (in position on McClernand’s left) was almost a mile away. The killing ground of the previous day, where so many men of the unit had fallen, remained a no-man’s land in front. The Confederates, still assailed by Foote’s gunboats and increasingly constricted by Grant’s noose of infantry and artillery, were planning to open the river road on Grant’s far right flank in an effort to escape to Nashville. Shortly after dawn, five brigades of Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s division, along with Forrest’s cavalry, rolled out of the fort and attacked the Yankees. The effort brushed aside a contingent of Federal cavalry and crashed against John McArthur’s brigade of mostly Illinois troops. McArthur’s men held for a while, but eventually the Rebel assault shoved them backward. Rebel artillery pounded McClernand’s line from the front, and the enemy infantry advance threatened him from the right and rear. Three additional regiments from the fort stormed against the front of Lew Wallace’s brigade on the right side of Morrison’s brigade (now commanded by Ross). The sudden attack shoved McClernand’s entire division out of position and folded part of it back upon itself.

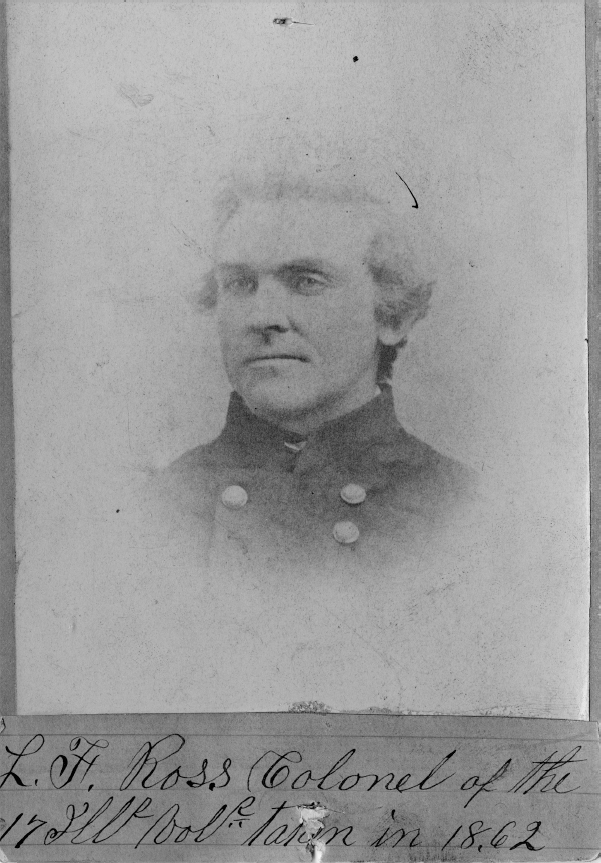

Colonel Leonard F. Ross, the first colonel of the 17th Illinois. He was promoted to brigadier general in April 1862. This image was captured that year in St. Louis. Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

Peats was with his company in an advanced skirmish position when he spotted Confederates in their rear and a heavy line of gray infantry in their front. The enemy infantry demanded their surrender. According to Peats, they “profanely called us Yankees, with a prefix and an affix that would shock all ears polite.” As Peats put it, he made the decision to “advance backwards.” After some searching, the skirmishers found the rest of the regiment in the new position where it had been driven and reorganized.19

McClernand sent couriers flying in a desperate search for assistance. Lew Wallace sent some troops from his division to help stymie further Rebel progress. The assault gave the Confederate defenders a brief window to make good their improbably escape. Inexplicably, after tearing a large hole in the Yankee right wing, Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow ordered his troops to halt their advance and return to the fort for baggage before setting out for Nashville. By that time, Grant was busy bringing up reinforcements to restore his lines and bottle up the Confederates. The small brigade now led by Leonard Ross, consisting of the 17th and 49th Illinois regiments, joined with other units of McClernand’s and Lew Wallace’s divisions and moved forward against the Rebels. On the far left of the Union line, which Grant believed must have been stripped thin, Brig. Gen. Charles Smith’s division went over to the attack. All that remained there was a lone Tennessee regiment. Smith’s men overwhelmed the Tennesseans and occupied the outer works before stopping. The gray troops who had pushed back the Yankee right returned to their defenses, once again pinned inside the fort.

Confederate officers met that night to debate surrender. Those present included brigadier generals John Floyd, Simon Buckner, Gideon Pillow, and Bushrod Johnson. Forrest, who commanded the cavalry that had opposed the 17th during the fight’s opening action, determined not to give up. He called his men together. “Boys,” he explained, “these people are talking about surrendering, and I am going out of this place before they do or bust hell wide open!” Floyd and Pillow also managed to find a route out of the fort for themselves, leaving Generals Buckner and Johnson to deal with Grant. (Johnson, too, escaped after the fort surrendered.)

On Sunday, February 16, white flags fluttered above Fort Donelson and Buckner sent Grant a request for surrender terms. The generals knew each other from their days at West Point and time together during the Mexican War. Buckner had even helped Grant financially before the war. If he hoped for lenient terms from his old friend, he was disappointed. Grant demanded “unconditional surrender,” and added that if he failed to comply, he would “move immediately upon your works.” Buckner called Grant’s terms “ungenerous and unchivalrous,” but had no choice other than capitulation. The surrender of the fort and its garrison gave the Union 12,000 to 15,000 prisoners, 20,000 small arms, 48 pieces of artillery, 17 heavy guns, 2,000 to 4,000 horses, and large quantities of commissary stores.20

When the Yankees arrived in the fort, Josiah discovered the enemy had “torn up old carpets and clad themselves in all kinds of rags to protect themselves from the cold.” When the men of Grant’s army marched past the disheveled and dispirited prisoners, Frank Peats recalled, an Irishman of the 17th Illinois discovered another son of Erin clad in gray. “What the devil are yees doing here?” he demanded.

“Foiten,” came the reply.

“Foiten for what?” asked the Yankee.

“Fur glory.”

“How much glory did yees git yer damn fools?” shot back the blue-clad Irishman. According to Peats, “Blue and gray both roared with laughter”21

* * *

Jennie’s letter of February 8, 1862, arrived when Josiah was in the battle line at Donelson. He wrote back after the fighting ended.

Fort Donelson Tennessee

February 22nd 1862

\Miss Jennie E. Lindsay,

The “poor soldier boy” is here, the storm has passed and I improve the first opportunity of making known my whereabouts.

Well Jennie it is a dark day that has no sunshine and tho “disappointment” rules the day yet for once disappointment came as a pleasant messenger to your humble servant on last Sabbath morning, as you have no doubt heard of the Fort Donelson battle I need not say much the old 17th had its share, for 3 days and nights we were incessantly exposed to the rebel fire—shell, grape, canister & leaden hail by day—storm rain & snow by night all combined to exhibit in the most vivid colors the true “horrors of war.”

Col Ross, Lt. Col Wood, Cap Norton, & Dr Kellogg22 all arrived on the afternoon of Saturday the 18th inst being the third day of our engagement—we had then fallen back a short distance to give place to some fresh troops but on the arrival of our commander our Regt took new life and fixed for the contest anew—Col Ross lead us forward to support other advancing forces but as the enemy disappeared behind their breast works, we after remaining there till dark fell back to get a nights rest but Oh what a nights rest—not that of the criminal conscience stricken, no, but that of the wearied soldier drenched in rain for we had no tents and but little covering since we left Fort Henry about daylight we were called on to prepare for the solemn contest of the day for this day (Sabbath) had been fixed to give the decisive blow to the infernal crew—I was pondering over the past (for I had loosed one of my most noble men the morning previous a fellow classmate) when Cap Norton called my name delivered me a paper and left.

I was in no plight to read newspapers but from the fact of it coming from Peoria I first examined and then suspected and then came the pleasant “disappointment” for Oh what a dear little package that was – it seemed like sunshine amid the storm—the horrors of the past 3 days yielded to the welcome “intruder” and sorrow was wiped away, while thus exulting over that happy moment the report came that Fort Donelson had surrendered and I thot it must be a dream, that was too much joy for one hour but the fact was real for as our Regiment was in the Brigade more directly engaged we had the honor of first entering the fort—this was a very strong place and tho many of our noble freemen have fallen in the conflict yet it is a great victory.

Oh Jennie it was a sorrowful sight to pass over the battle field on Sabbath, hundreds lay dead side by side and Oh the contrast, true american soldiers here and a few rods beyond the vile rebel each sleeping the sleep that knows no waking.

Capt Swarthout formerly of Peoria fell mortally wounded on Saturday I spoke to him not 20 minutes previous, he was a fine fellow, my company lost one killed23 (by a shell) and four wounded I did not receive a scratch tho I do not feel very well since, but were ready for Nashville as I think that is the next point (110 miles up the Cumberland river).

Well I must have wearied you Jennie you have all this in the papers ere this–I keep that dear little memento of Sabbath morning noteriety as my daily companion to cheer on through these darksome days my only regret being that the “intruder” had not been the original—Remember me to Mrs Currie and all the dear old friends of Peoria and in view of a brighter day I bid thee most worthy lady, a kind adieu (pro tempore).

Josiah Moore (I am still waiting for those letters)

P.S. Excuse blots and scribling for this is a sorry place to write. J.M.

Please address: 17th Ills. Regt. Co. F via St Louis Mo I think this is the surest way

The man killed “by a shell,” Pvt. Clark Kendall, was killed at 7:00 a.m. on February 15 when an artillery projectile carried away the top of his head. According to Sergeant Duncan’s log book, Kendall was “[b]uried near the center of the north line of the graveyard near Dover Tenn. Head board marked with name.” Kendall, who enlisted at the age of 18, was the first Monmouth College student killed in the war. His body was one of the hundreds that lay in the fields after the fight for Donelson. Unfortunately, in 1862 there was no organized system of communication that existed to inform families of the fate of their loved ones. After initial reports of a terrific battle, people back home would anxiously wait for news and, in the absence of a letter from the front, scanned the casualty lists of killed and wounded that often appeared in hometown newspapers. Typically, the job of notifying a family with news of a fallen member was taken up by one of the soldier’s comrades or his commanding officer. In Kendall’s case, that sad task fell to Josiah.24

On February 21, Josiah composed the following letter to Kendall’s parents, which eventually appeared in the March 28, 1862, edition of the Monmouth Atlas:

Letter from Capt. Moore

Fort Donelson, Tennessee

February 21st, 1862

Mr. and Mrs. Kendall:

Dear Friends:

I improve the first opportunity of writing you a few lines, and though at other times the task would have been pleasant, yet on such an occasion, it is most painful, yet duty requires that I conceal not the fact. My request then is, that you prepare for the worst. Your noble boy—Clark A. Kendall—is no more. Comment is not necessary. The stroke is a hard one, and bereaved friends, you have your sympathizers. Clark was beloved by all. The loss of a brother could not have made me more sad. In him my highest hopes were centered. But God’s ways are not as ours. He doeth all things well. It then becomes our duty, though sad and solemn, to bow in humble reference and say, not our will but thine, O God, be done. Clark’s work on earth is finished; but I trust he has left the blood—stained hosts of earth to join the blood washed army of the redeemed in glory. Dear Christian friends, though we may weep that the silver cord is broken, yet we do no sorrow as those who have no hope.

[The next dozen or so lines are illegible.]

I hope that by trusting in a friend that sticketh closer than a brother, you may be enabled to best the present shock with Christian resignation. I am not old but have tasted some of the sorrows of this present evil world; yet I have never drank a more bitter draught than the subject of this epistle calls me to indite. A fellow class mate, a fellow soldier, and last but not least, I trust, a fellow soldier of the cross, constitute a three fold cord of friendship, than which, except the parental ties of endearment few are more sacred.

A few items, (though I presume you have heard ere this) Clark was killed on Saturday morning of the 15th inst, about 7 o’clock, by a four pound shell shot from the enemies’ batteries. The shell carried away the entire top of his head, killing him instantly. Sergeant Duncan, Corp. Clark, J.C. Weede and G. Matchett stood close by—none were hurt. Matchett had his coat torn and himself shocked badly, but not hurt otherwise. We saw brother Frank immediately afterward. He requested that we send the corpse home. We were forced by the enemy to leave our position that night, so we carried the body over two miles to our camp. In the morning, news came of the surrender. We were marched through the fort and after being stationed we had the body brought to our camp, with the hope of being able to get up some sort of a coffin that would bear transportation. Sergeant McClanahan worked hard nearly a day, but without any success. No tools could be found, and as the weather was becoming warm, our only alternative for the present was to bury him. He is buried in a grave yard close to a little town called Dover, that is included inside of the enemies breastworks. We had a board marked with his name as well as we could, and I think it will not be interfered with. I was to see it today. It is easily found. If I had any assurance of remaining here for some time, I would send to Cairo for a metalic case but I believe we have orders now to move, and I have no chance. Our destination I do not know. The war clouds are gathering thick and fast. God only knows what the result shall be; but we have the assurance that all things work together for good to them that are called, according to his purpose. There are fiery trials—the people have sinned and the land mourneth. O, may we as a nation be enabled to break off by righteousness and bow before the footstool of the most High.

Dear friends, anything that I can do for you, shall be done with greatest of pleasure. I shall speak to the Orderly, that he may also write you a little. Excuse my random letter. I should have written sooner, but I had no means. We stood these days and nights on the battle field; often exposed to the enemies fire. We were almost exhausted—the only wonder is that any escaped. The wounded are doing well and we are all fast recruiting.

That God may enable each of you to look beyond this dark world to the brighter land, is the sincere hope and prayer of your sorrowing friend.

Josiah Moore

In their letters home, soldiers typically omitted the more gruesome details of a soldier’s death, or asked male recipients not to show the letter to the women of the family. Josiah graphic description of Kendall’s death perhaps was intended to assure the family that he had died bravely for a noble cause. His wish that Kendall’s parents endure with “Christian resignation” is typical of the time. Josiah and many other Christians of that era believed that bearing the loss of a loved one with dignity while suffering with nobility brought one closer to God. A contemporary historian notes the importance of “well borne suffering” by soldiers as “evidence of the justice of their cause.” Josiah was asking the family to adopt that same “well borne suffering” as a testament to their son. Unfortunately for Josiah, he would have cause to pen similar letters over the months to come.25

Josiah’s graphic description illustrates again the crucial role that officers played in the lives of their men. Many soldiers had never left home before they entered military service. Previously, a mother or sister had taken care of their basic needs. In the absence of women, officers typically fulfilled that role. They oversaw the safety of the men, made sure they were keeping themselves clean and healthy, and served as mentors and consolers. This role of consolation was one of the most important “feminine” duties the captain of a company assumed. As the man who had led his men away from Monmouth, it was Josiah’s duty to explain to families such as the Kendalls why their sons would not return. In fact, it is fair to say the captain of the company filled the traditional nineteenth-century roles of both mother and father. He oversaw their needs, enforced discipline, and somewhat ironically, issued orders that often led to their deaths. Enlisted men were aware of how their company commanders treated them, and they approved those who prioritized their welfare. Men also wanted their leaders to be morally upright. By all accounts Josiah won the approval and respect of his men. He also complimented his company in his letters back home, something that people in the community took note of and appreciated.26

A letter from the mother of Sgt. Joshua Allen of the 17th Illinois’ Company B provides yet another example of the lingering agony family members endured back home. Mrs. Allen sent the letter to Frank Peats after she heard rumors that her son had been killed in the Fort Donelson fighting. “Will you be so very kind as to take the trouble to write and let an anxious mother know if he is dead?” she pleaded. Before she could mail it, however, the Allen family received confirmation of their son’s death. His mother added a postscript to the letter: “Will you write me and let me know if there is any possibility of me getting his body? We hear that it was buried on the battlefield. Is his grave marked by anything? If you can find his body and send it to Hartford (Connecticut) you will confer an unlimited favor on his mother.”27

In addition to the notification of death, families yearned for details of how their loved ones lived and died. They wanted to know if they had been good soldiers and good people, and if they had experienced what people in the nineteenth century called a “Good Death,” which meant dying bravely and willingly giving up one’s soul to God. We find an example of this in another letter Peats received, this one from the family of John Pendleton, another sergeant in his company:28

Captain, while the whole Nation, North has been filled with ecstasy at the late victory won at Fort Donelson by the ‘brave sons and youths of our land’ many hearts at the same time have been filled with mourning for their dear ones that fell in defence of the Old Stars and Stripes. I too had an only brother fall on the 15th of Feb. one on whom all of my pride, hope, and anxiety was placed. Will you allow me to ask me what kind of life he lived in camp? Or did you ever hear him say he was ready to die at any moment? Were you near him at his late moments so that you could hear what his last words were? Captain, I ask these questions as none others can ask unless they feel the anxiety that a sister does when she finds her only brother and idol has been torn from her.”29

This with respect,

Rose Pendleton

Rose Pendleton also asked for her brother’s personal effects, including a picture of her he had carried in his knapsack. Peats reported that both Joshua Allen and John Pendleton were killed on February 15 and found clutching their rifles, “their faces upturned with open eyes looking through the calm bright sunlight of the Sabbath.” Unfortunately, the enemy had taken the items Rose requested be returned.30

More than a quarter-century after the battle, Peats recalled that the “saddest duty that falls to the lot of a soldier—gather up the dead,” and he remembered retrieving the bodies of these two young men “just standing upon the threshold of manhood.” “Will the infirmities of age so dim the vision, that our eyes will lose the reflected image of a soldier’s funeral? Will our ears ever become so deaf that we will forget the sound of the muffled drum and the three mournful volleys that have echoed above the grave of a fallen comrade?” Peats wondered.31

A visitor to Fort Donelson a month after the battle discovered indications of just how ferocious the fighting had been. “Frozen pools of blood were visible on every hand, and I picked up over twenty hats with bullet holes in them and pieces of skull, hair, and blood sticking to them inside,” he wrote. “The dead were buried from two to two and a half feet deep; the rebels didn’t bury that deep and some had their feet protruding from the graves.”32

Grant’s army numbered about 25,000 men and lost about 500 killed and another 2,100 wounded. Smith’s brief history of the 17th Illinois claimed the regiment lost 14 killed, 58 wounded, and seven captured during the Fort Donelson operations. According to the Official Records, however, 13 enlisted men were killed (one in Company F, Clark Kendall), five officers and 57 enlisted men wounded, and six enlisted men missing. Confederate strength was about 16,200, and of that number 327 were killed, 1,127 wounded, and 12,392 captured.33

Many in the Confederate ranks reexamined some commonly held beliefs after Fort Donelson. “I had been taught by demagogues and politicians to believe that I could whip a ‘cowpen full’ of common Yankees,” confessed a Mississippi soldier. “I lived and acted under this delusion till Gen. Grant and his army met us at Fort Donelson. I soon found that the Yankees could shoot as far and as accurately as I could, and from then until the end of the war I was fully of the opinion that the United States Army was fully prepared to give me all the fight I wanted.”34

Desperate for positive war news after the debacles of Bull Run, Ball’s Bluff, and Wilson’s Creek, as well as the Army of the Potomac’s continued inactivity, the people of the North were jubilant when news of the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson reached them. Newspapers trumpeted victor U. S. Grant as “Unconditional Surrender” Grant, and President Lincoln promoted him to major general, making him the highest ranking officer in the Western Theater after Henry Halleck. The twin victories were critical turning points in the war in the West. The successes opened broad avenues of invasion into the deep South and eliminated about one-third of Albert S. Johnston’s command in the Kentucky-Tennessee theater. Of the remaining enemy troops under Johnston’s control, about one-half were organized around Nashville with the balance much farther north at Columbus, Kentucky.35

The 17th Illinois remained in the vicinity of Fort Donelson until March 4. Six days later Jennie wrote another letter to Josiah.

Peoria, March 10 1862

Capt. Moore

I received your dear kind letter on last Thursday and was so thankful to hear of your safety. The first news we had of the battle was on Sabbath the 16th Oh that day of fearful suspense I would wish that we might never realize another such of it were not too impossible to hope for, for alas I fear it is but the commencement of many [illegible] busy with her thousand tongues telling of the dreadful conflict then raging and adding fuel to the flame by exaggerating everything that came within her reach It were impossible to give half the accounts that were told. One time the 17th Regt were all killed then again they had not left Fort Henry. So passed Sunday no one knowing what to believe But all hoping that our Father in Heaven would be merciful and give unto us the victory and forever crush this wicked rebellion.

Monday morning dawned upon many an anxious heart. all longing to hear the news yet dreading lest it might be such as to forever banish the sunlight from the lonely heart made desolate on hearing that the loved one has gone gone without a parting word or look to cheer them on through lifes dreary pilgrimage.

About noon we received a dispatch telling of the surrender of the Fort. The people were perfectly wild with joy, truly it was a great victory and we all rejoiced on that day not knowing what sad tidings the morrow might bring. On Tuesday morning as dispatch came from Capt Norton saying the officers of the 17th were all safe. I say blessed be the hand that sent that message.

I have been staying with Cousin Sarah while Mr Currie was in New York. The Regt left while he was gone his brother took his place to keep it for him but I guess as Sarah is so much opposed to his leaving home he will give it up. Your old Friend Mr Young has gone with the Regt so poor Mollie is left a widow She is keeping house on the bluff. They have a very pleasant little home and seem to live very happily.

The week after the battle they had it reported that the 17th Regt were on their way to Peoria with one thousand prisoners to be stationed at Camp Mather. But this child felt that was one of the joys too good to be true. The Peorians were looking daily for your arrival but as you are aware they looked in vain.

I suppose you have received my letter ere this time it was mailed on the 17th day of Feb and directed to Gireudeau.

Well as it is growing dark and this uninteresting epistle must be in the office tonight I will have to say farewell hoping many happy days are yet in store for thee.

Please write soon

Jennie

P.S. I know it is wrong to cherish a feeling of envy but I do envy this letter. JEL

Jennie’s letter demonstrates the anxiety those at home experienced after hearing reports of a major battle they feared might have involved their loved ones. Unsubstantiated rumors of disaster crushed morale at home, while talk of victory sent jubilation sweeping through the community. Meanwhile, soldiers’ families could do nothing but sit and wait with apprehension until more definite news arrived.

* * *

Grant’s victorious command had to deal with the military material it captured at Fort Donelson, and faced here in the Donelson aftermath another problem for the first time: slaves in the field. Confederates soldiers, particularly officers, often took their slaves to war with them, and the victorious Union forces now had to deal with the slaves of surrendered Rebel soldiers. On February 27, Lt. Col. Enos Wood, now in command of the 17th Illinois after Leonard Ross was advanced to brigade command to replace the wounded Morrison, issued an order directing officers to “report … all slaves in their possession that were taken at the Capture of Fort Donelson. Company Commanders will be held accountable for all violations of this order.” Captain Peats and Lt. Jones, also of Company B, “engaged [a black youth] at Fort Henry to carry our blankets and rations.”36

The treatment of captured and runaway slaves had posed problems for the military from the outset of the war. The typical Union soldier, neither an abolitionist nor a believer in the equality of the races, nonetheless understood that slavery lay at the root of the bloody conflict. Those who were ardent abolitionists protected runaways from their masters who came to claim them, and any Northern soldiers who might want to mistreat them. But these soldiers were in the minority. Many others routinely used derogatory and demeaning terms to describe the slaves they encountered. Some treated them as sources of amusement and played practical jokes on them—or worse. Since soldiers saw slavery as the cause of the war, they viewed slaves as both culprit and victim. Some Union officers returned runaway slaves to their masters. Others, most notably Union General Benjamin Butler, did not. Just one month into the war, for example, Butler, who was then at Fort Monroe in Virginia, announced that he would keep escaped slaves as “contrabands of war.” As far as he was concerned slavery had caused the war, and only its destruction could end it. Butler felt justified in not returning them. Through the second half of 1861, many more men in blue came to see things about the same way. As one Wisconsin soldier saw it, the war was “abolitionizing the whole army.”37

In order to clarify the status of freed and escaped slaves, Congress passed the First Confiscation Act in August 1861. It gave the Union army the right to take any slaves engaged in overt acts of support for the Confederate effort, such as building entrenchments. In practice, though, any slaves who entered Union lines voluntarily or were left behind when their masters fled were considered emancipated. As one historian pointed out, military emancipation and state abolition were two different policies pursued by Republicans along parallel lines throughout the war.

The Second Confiscation Act, enacted in July 1862, went even further. This law officially emancipated every slave who entered Union lines on their own volition, freed slaves who had been “abandoned” by their masters in the face of incursion by the Yankee armies, and finally ended the bonds of slavery for all those slaves living in areas that were currently occupied by northern armies, whether their masters remained or not. The act also gave Lincoln the discretion to further broaden the scope of emancipation by granting the president the power to end slavery in all areas still in rebellion and, for the first time, to allow blacks to wear Union blue. Lincoln would soon use this power to transform the war effort.38

1 Boatner, Civil War Dictionary, 440.

2 Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity 1822-1865 (New York, NY, 2000), 71; Boatner, Civil War Dictionary, 352-353.

3 McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 392-397; Boatner, Civil War Dictionary, 367.

4 Peats, Recollections, 9.

5 Hicken, Illinois in the Civil War, 12-13, 162-164.

6 McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 396-397. McClernand was difficult, but he was also a fighter. Grant despised him and would eventually sack him, but he would also give him important tasks, especially during the Vicksburg Campaign. McClernand proved to be one of the better Union political generals of the war.

7 Peats, Recollections, 15-16.

8 Moore, A History of the 17th Illinois.

9 Peats, Recollections, 23.

10 Steven E. Woodworth, Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861-1865 (New York, 2005), 87; James Jobe, “The Battles for Forts Henry and Donelson,” in Blue and Gray Magazine Volume XXVIII, Number 4, (2011), 25-26; Peats, Recollections, 20-25. Lew Wallace, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War: The Century War Book: People’s Pictorial Edition (New York, 1894), Vol 1, Number 3, 40-41. Lew Wallace (not to be confused with W. H. L. Wallace), would go on to pen the bestseller Ben-Hur.

11 Ibid., 40-41; Peats, Recollections, 24; Jobe, The Battles for Fort Henry and Donelson, 43.

12 Colonel Morrison was struck in the hip and knocked out of the battle and the war. Unable to take the field, he finally resigned in December 1863. He was replaced as brigade commander by Leonard Ross, the commander of the 17th Illinois, who was absent on the day of the battle.

13 Peats, Recollections, 20-25.

14 Wallace, Battles and Leaders, 41. Smith, History of the 17th Illinois; M.F. Force, Campaigns of the Civil War: From Fort Henry to Corinth (Edison, New Jersey, 2002), 42-43; Report of Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 Vols. (Washington, DC 1880-1901), Series 1, Volume 7, 173 (hereafter cited as OR. All references are to Series 1 unless otherwise noted); Peats, Recollections, 20-25.

15 Woodworth, Nothing But Victory, 88-89.

16 Peats, Recollections, 26.

17 Ibid, 26-27.

18 Ibid., 27-28.

19 Jobe, The Battles for Fort Henry and Donelson, 45-48; Peats, Recollections, 28-31.

20 Jobe, “The Battles for Fort Henry and Donelson,” 45-49; Benjamin F. Cooling, “Forts Henry and Donelson,” in Blue and Gray, Volume IX, Issue 3, (1992), 52.

21 Peats, Recollections, 37.

22 Lucius D. Kellogg was the surgeon of the 17th Illinois Infantry.

23 Private Clark Kendall.

24 Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York, NY, 2008), 14.

25 Ramold, Across the Divide, 4, 28; Clarke, War Stories, 16—19, 54.

26 Mitchell, The Vacant Chair, 82—84; Ibid., 42—51.

27 Letter to Frank Peats from Mrs. Robert Allen, March 4, 1862.

28 Faust, This Republic of Suffering, 6.

29 Letter to Frank Peats from Rose Pendleton, March 9, 1862.

30 “Inventory of the Effects of Deceased Soldiers” for John Pendleton. Peats Collection.

31 Peats, Recollections, 37.

32 Hicken, Illinois in the Civil War, 42.

33 Smith, A Brief History of the 17th Illinois Volunteer Regiment; Kendal D. Gott, Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862 (Mechanicsburg, PA, 2003), 284–85, 288.

34 Jeff Giambrone, Blog: Mississippians in the Army of Tennessee, www.mississippiconfederates.wordpress.com/2011/09/01/mississippians—in-the-army-of-tennessee; Statement of George E. Estes, 2nd Lieutenant, 14th Mississippi.

35 McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, 405; Smith, History of the 17th Illinois.

36 Order book for Company K, 17th Illinois, May 1861-July 1862; Regimental Order No. 55, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum; Peats, Recollections, 33.

37 Manning, What This Cruel War Was Over, 43-45; Mitchell, Civil War Soldiers, 122-125.

38 James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery (New York, London, 2013), xiii, 224-225, 226-229.