In which we encounter the terraqueous chrysoprase, Bertrand Russell’s twenty favorite words, Piers Anthony’s ten favorite words, logophiliacs, Oulipoian states of mind, constrained writing, Pynchonomancy, Annie Sprinkle, Robert Sawyer, divination, the mystery of italics, Brion Gysin’s Dream Machine, music, painting, plot aesthetics, Dia Center for the Arts, lipograms, The Anagrammed Bible , Michael Shermer, “A Glass Centipede,” computer poetry, creativity machines, Rachter, Ray Kurzweil, Yggdrasill, alien beauty, alien pornography, the Reverend Jerry Falwell, adipocere, Monongahela, Harlan Ellison, Antonin Artaud, Aldus Manutius, the world’s largest vocabulary, and amphigory.

Proust, Einstein, Russell

Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time is the “greatest and most rewarding novel of the twentieth century, outdistancing its closest rivals, James Joyce’s Ulysses , Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain , and William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom !” 2 So says Roger Shattuck, author of Proust’s Way: A Field Guide to In Search of Lost Time. British novelist Graham Greene (1904–1991) said, “Proust was the greatest novelist of the twentieth century.” Proust believed that a book was a dynamic entity because a person could read it many times, with new meaning emerging each time the book was read. Thus, rereading a book from one’s teenage years can be enlightening because it allows readers to see how they have changed.

One of my favorite books from my teenage years is: Dear Bertrand Russell: A Selection of His Correspondence with the General Public 1950– 1968 . 3 The book contains all sorts of letters from Russell’s fans, along with his witty responses. I’ll now use Russell’s book as a trigger for a zany chapter on people’s favorite words and aesthetics in general.

My notebook rests safely in my hand. The air is sweet with the scent of lilacs. I sit on a bench in front of the Hart Library in Shrub Oak. In the last chapter, you learned about my fascination with language and words. Today, I’d like to continue that discussion, and also talk about what you and I consider beautiful—but first a few words about my home town’s local library, which I frequently visit to borrow books and audiotapes, learn new words, and generally elevate my mind.

The John C. Hart Memorial Library received its charter from New York State in 1920. Catherine Dresser, daughter of John C. Hart, died in 1916, and in her will she left her family homestead and 45 acres of land to the Town of Yorktown. John C. Hart was born in Shrub Oak in 1822 and attended the district school here. Later he worked in New York City, but his heart and soul were always in Shrub Oak. 4

Hart’s Shrub Oak house underwent frequent remodeling and finally became the Hart Library, in front of which I now sit. Today, nothing of the original 1920 library walls remains. All that exists of Hart himself is an old portrait now hanging on the first floor in the paperback section. He and his wife are buried in the Methodist Churchyard in Shrub Oak. Hart loved his house and the land, and wrote poetry.

Nowadays, the library has a great collection of books by philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872–1970). Russell was many things: a mathematician, a logician, an atheist, a champion of peace, a controversial political figure, and a recipient of the Nobel Prize in literature. Russell so impressed Einstein that in 1931 Einstein wrote to him, “The clarity, certainty, and impartiality you apply to the logical, philosophical, and human issues in your books are unparalleled in our generation.” 5

The Terraqueous Chrysoprase!

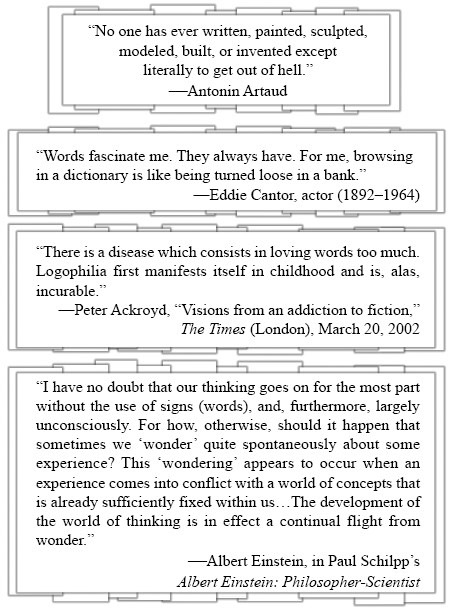

In 1958, a fan asked Bertrand Russell to list his twenty favorite words in the English language. Russell replied, “I had never before asked myself such a question,” and then proceeded to give his list as follows:

Isn’t this a lovely set of luminous words? When examining lists like this, we can compute an “obscurity index” (OI) that tell us the degree to which a person tends to choose words not commonly used by English speakers. When I compute the OI, I simply note the number of words my Lotus WordPro spell-checker does not understand and divide this number by the number of words in a person’s list. Russell’s obscurity index is 0.25 because my word processor does not understand five of his twenty words (terraqueous, inspissated, incarnadine, chorasmean, chrysoprase). The higher the index, the more “obscure” or “arcane” the list is. For those of you interested in other indices of obscurity, you can simply use Google to count how many Web pages exist that contain the words.

It’s obvious I’m in love with these fancy-sounding words. How many of Russell’s words do you like or comprehend? I am amazed that such a busy and famous person as Russell would even answer this question about favorite words posed by an unknown fan! Russell received around 100 letters a day. Scholars estimate that Russell wrote one letter every thirty hours of his life. Whenever he changed residences, Russell said that it was “usual for quantities of paper to be burned.” When asked how he coped with the onslaught of letters and with writing all his articles and books, he replied by highlighting his daily schedule: “From 8 to 11:30 AM , I deal with my letters and with the newspapers. From 11:30 to 1 PM , I am seeing people. From 2 to 4 PM , I read, primarily current nuclear writings. From 4 to 7 PM , I am writing or seeing people. From 8 to 1 AM , I am reading and writing.” 6

Could I imitate Russell’s fan by requesting favorite words from other famous people? Would people respond to my request for a list of their ten favorite words? Following the example of Russell and his admirer, I asked a number of modern-day thinkers to give me their Top 10 words, especially for this book. My request for words stems from my lifelong obsession to survey everything and anything, no matter how odd the survey may appear. The next few pages contain word lists I received from provocative people.

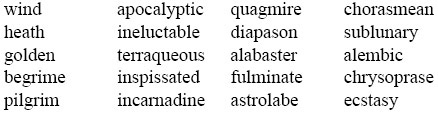

Piers Anthony (hipiers.com) was one of the first famous people to respond to my request. Piers is one of the world’s most prolific fantasy writers and creator of the Xanth series. He’s published more than a hundred novels, and I collaborated with him on our novel Spider Legs. Anthony’s novel Ogre may have been the first original fantasy paperback ever to make the New York Times bestseller list. He sent his Top 10 words to me:

That’s a nice set, spanning the sensual (sex, chocolate) to the realm of pure thought (imagination, empathy, etc.). His obscurity index is 0, because my word processor understands all ten words. Perhaps the index is telling us the degree to which people like “exotic” words.

Paul Krassner (paulkrassner.com) is a political satirist and author of countless books, including Murder At the Conspiracy Convention and Other American Absurdities , Confessions of a Raving , Unconfined Nut , and Psychedelic Trips For the Mind. Don Imus labeled him “one of the comic geniuses of the 20th century.” Krassner sent me his list:

Paul’s obscurity index is 0.

I was delighted with the word lists of these famous writers, so my next step was to contact someone a bit more outrageous than the rest. Annie Sprinkle, Ph.D. (AnnieSprinkle.org), is a prostitute/porn star turned internationally acclaimed feminist performance artist, author, and sexologist. Her ten favorite words:

clit

lick

moist

grace

snuggle

scrumptious

titillating

snorkel

pink

fart

She asked that her words be centered, as above, to form “an approximation to a vulva or labia shape.” Her obscurity index is 0.1, because my spell checker did not recognize “clit.”

David Jay Brown (mavericksofthemind.com) is the coauthor of three volumes of interviews with leading-edge thinkers— Mavericks of the Mind , Voices from the Edge , and Conversations on the Edge of the Apocalypse. His list:

His obscurity index is 0.1. David constructed several different lists of his “ten favorite words”—using various criteria for how he defined “favorite.” His initial list contained unusual words that he liked because of either their interesting meanings or pronunciations, but eventually he settled upon the ten words that simply made him the most happy to hear.

Douglas Rushkoff (rushkoff.com), a professor at New York University, has published ten acclaimed books on media, culture, and values. He is also a correspondent for PBS Frontline. His most recent books are Coercion and Nothing Sacred: The Truth About Judaism . His favorite words:

His obscurity index is 0.3.

Robert Sawyer is the Hugo and Nebula award-winning science-fiction author of dozens of immensely popular novels including Calculating God , Hominids , The Terminal Experiment , Frameshift , and Illegal Alien . His list:

His obscurity index is 0.2.

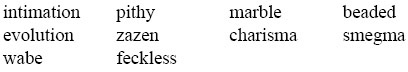

Dr. Michael Shermer is the founding publisher of Skeptic magazine, the director of the Skeptics Society, a monthly columnist for Scientific American , and the co-host and producer of the 13-hour Fox Family television series Exploring the Unknown . He is the author of The Science of Good and Evil and Why People Believe Weird Things . His list with his personal definitions:

His obscurity index is 0.2.

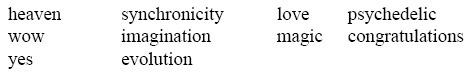

By now you may be wondering about my own favorite words. I compiled such a list several years ago. For the record, my twenty favorite words in the English language are:

My obscurity index is a walloping 0.9! What does this say about my personality? Please note that I created this word list well before I had the notion of calculating the obscurity index, so I was not biased in my word selection because of the index.

A Visit to Monongahela

What makes certain words our favorite? Is it their sound, their look, their meaning, or something else entirely? If you were to choose twenty words at random in a large English dictionary, how many of these words could you define? How many might be candidates for your own Top 10 list?

Let’s have some more fun in this section. Could a best-selling author, such as Stephen King, John Grisham, Anne Rice, or Dean Koontz succeed in creating a best-selling novel if forced to use ten words randomly selected from a dictionary in the first two pages of a novel? (Some colleagues believe that with names like “Stephen King” or “Anne Rice” or “Dean Koontz” on the cover, the books would fly off the shelves even if the entire book were only ten words randomly selected from a dictionary.) Just for fun, my colleague Graham used a random-number generator to select ten pages at random from the Webster’s New World Dictionary , and selected the first word in the left-hand column:

I wonder if Stephen King would have trouble using all of these on the first two pages of his next novel? Here is my colleague Jeff Carr’s attempt to use the ten random words to start a story. I’ve underlined the words:

It was dusk by the time Lieutenant Graham approached the yard and nearby cottage. Time had taken its toll, as evidenced by the junk surrounding the yard. Oddly, a curricle was sitting under an awning, covered with an overplus of moss. As a child, Graham remembered that he would play detective on such a carriage. Now, many years later, he was surprised to encounter one again.

The Lieutenant entered the small workshop adjoining the cottage. The temperature inside was unusually warm. Unlabeled cans sat next to a pile of thimbles. The odor reminded Graham of the isocyanates he had worked with years before, when he assisted an archaeologist friend in repairing several old Hebrew gerahs. Leaving the workshop, Graham carefully approached the front door of the cottage, took out a comb to move his bang back away from his forehead, and then tapped gingerly on the door with his swaggerstick. What happened next was to totally change the Lieutenant’s life forever.

My colleague Todd wrote a Visual Basic application that selected a random word in his Merriam-Webster Dictionary . His ten random words reminded him of a brilliant mystery novel:

carafe —a water bottle

allude —to refer indirectly

headmaster —a man heading the staff of a private school

amulet —an ornament worn as a charm against evil

racketeer —a person who extorts money

sportsman —one who plays fairly

brand (vb.)—to mark with a brand

tedious —tiresome because of length or dullness

drawing card —something that attracts attention or patronage

missiv e—a letter

Todd is now feverishly at work, writing a mystery novel that incorporates these words into the first chapter.

Throughout history, famous people have compiled lists of their “favorite words,” and I wonder what the choices of words tell us about the individuals. For example, poet Carl Sandburg chose Monongahela as his favorite word. 7 Wilfred Funk, a lexicographer, editor, and author, listed the following as the most beautiful English words: asphodel, fawn, dawn, chalice, anemone, tranquil, hush, golden, halcyon, camellia, bobolink, thrush, chimes, murmuring, lullaby, luminous, damask, cerulean, melody, marigold, jonquil, oriole, tendril, myrrh, mignonette, gossamer, alysseum, mist, oleander, amaryllis, and rosemary. 8 Reporter, editor, writer, and author Willard R. Espy lists these as the most beautiful: gonorrhea, gossamer, lullaby, meandering, mellifluous, murmuring, onomatopoeia, Shenandoah, summer afternoon, and wisteria. 9 From the thousands of submissions Merriam-Webster OnLine received (www.mw.com) in 2004, here are the ten words entered the most often for the “Top Ten Favorite Words List”: defenestration, serendipity, onomatopoeia, discombobulate, plethora, callipygian, juxtapose, persnickety, kerfuffle, flibbertigibbet. All of these lists remind me of TV host David Letterman’s “Top 10 Words that Sound Great When Spoken by James Earl Jones”: mellifluous, verisimilitude, guppy, Stolichnaya, Boutros-Boutros Ghali, Neo-Synephrine, pinhead, Mujibar and Sirajul, heebie-jeebies, and Oprah.

In the cult movie Donnie Darko , the high-school English teacher discusses J. R. R. Tolkien, who said “cellar door” was the most beautiful sounding combination of words in the English language. A mysterious cellar door plays a secret role later in the film, but I’m interested in the auditory appeal of the phrase. In his essay “English and Welsh,” Tolkien described a theory of phonaesthetics in which words have a beauty that is often quite separate from their meaning. According to Tolkien, “Most English-speaking people…will admit that Cellar Door is ‘beautiful,’ especially if dissociated from its sense and from its spelling.”

Noted author Harlan Ellison recently lamented that the Internet is destroying people’s use of dictionaries, and this in turn decreases our vocabularies, literacy, and our ability to become great authors. 10 Why? Ellison believes that whenever you look up a word in a real, physical dictionary, you pass dozens of other words, some of which will stay in your memory, triggering serendipitous associations, and engendering a sense of wonder. In the old days, when people used dictionaries, Ellison thought that people became “better, more literate, smarter and well-rounded.”

James Joyce’s Cuspidor

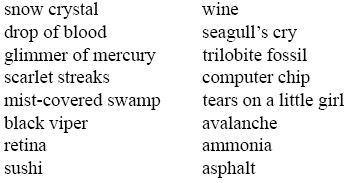

James Joyce said his favorite word was cuspidor —or at least he felt it was the most euphonious word in English. Joyce’s cuspidor stimulated me to conduct another survey of colleagues. In particular, I asked dozens of people which of the following items they rated most beautiful:

Before reading further, which of these words and images do you think humans rate most beautiful?

Are you ready for the answer? Here is the list of terms sorted in order of beauty as determined by my little survey of scientists and colleagues. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of times the term was an individual’s first choice: dancing flames (31), snow crystal (20), mist-covered swamp (17), spiral nautilus shell (10), mossy cavern (5), kaleidoscope image (5), avalanche (4), computer chip (3), seagull’s cry

(3), tears on a little girl (3), trilobite fossil (2), glimmer of mercury (2), wine (2), asphalt (1).

Conduct the experiment yourself. Why do you think “dancing flames” is always the clear winner? Perhaps the delightful warmth and unpredictable motion of the flames, coupled with the flame’s potential danger, give the flames a unique emotional resonance. The motion is constant, repeating similar themes but not identical structures. My colleague Hannah Shapero reminds me that Zoroastrianism uses a burning flame on an altar as the prime symbol of God. On the hearth or altar, the flames symbolize protection and light in the darkness. Zoroastrianism was born in Persia, and legends exist of sacred fires in Iran that have been kept burning continuously for more than 2,000 years. Hannah speculates that the random patterns of light cast by the flames, along with the gentle warmth, elicit alpha waves or other pleasant states in the brain of the onlooker, much as meditation does.

Many colleagues suggested additions to the “beauty” list of 22 words that I gave them to choose among. I give a listing in a footnote so that my publisher will not yell at me for filling more pages with long lists. 11

The “dancing flames” remind me of the Dream Machine invented in 1959 by poet and painter Brion Gysin and mathematician Ian Sommervile. When I was younger, I tried to make one, but didn’t have the right tools. The Dream Machine resembles a cylinder with cutouts that spin around a lamp. The cutouts are spaced to produce a flicker. A user places his face a few inches away, with eyes closed. The flickering light induces alpha waves in the brain. Effects of such periodic waves on the human brain varied among users, some of whom found the flicker to induce drugless visions and states of lucid dreaming.

The device was so useful that American novelist William S. Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch , used the Dream Machine as a source of inspiration throughout his visionary career. Others said it gave them visions of being “high above the Earth in a blaze of glory.” 12 Gysin received a patent for his invention in 1961, and several large Dream Machines were made.

Alien Beauty

While on the subject of beauty, I am tempted to speculate upon what aliens would consider as beautiful art. Would an alien race of intelligent robots prefer a combination of graffiti-like figures echoing the art of children and primitive societies, or would they prefer the cold regularity of wires in a photograph of a Pentium computer chip? If we were to give technologically advanced aliens from other worlds a musical CD, they should be able to conclude we have an understanding of patterns, symmetry, and mathematics. They may even admire our sense of beauty and appreciate the gift. What more about us would our art reveal to them? What would alien art reveal to us?

Whatever their aesthetic differences, alien math and science might be similar to ours, because the same kinds of mathematical truths will be discovered by any intelligent aliens. But it’s not clear that our art would be considered beautiful or profound to aliens. After all, we have a difficult time ourselves determining what good art is. Picasso said, “Art is the lie that reveals the truth.” Brain researcher Vilayanur S. Ramachandran described art as, “That which allows us to transcend our morality by giving us a foretaste of eternity.”

Because alien senses would not be the same as ours, it’s very difficult to determine what their art or entertainment would be like. If you were to visit a world of creatures whose primary sense was smell and who had little or no vision, their architecture might seem visually quite boring. Instead of paintings hanging on the walls of their home, they might use certain aromatic woods and other odor-producing compounds strategically positioned on their walls. Their counterparts of Picasso and Rembrandt wouldn’t make paintings but would position exquisite concoctions of bold and subtle perfumes. Alien equivalents of Playboy magazine would be visually meaningless but awash in erotic aromas. Their culinary arts could be like our visual or auditory arts: Eating a meal with all its special flavors would be akin to listening to a Chopin waltz. If all the animals on their world had a primary sense of smell, there would be no colorful flowers, peacock’s tails, or beautiful butterflies. Their world might look gray and drab.…But instead of visual beauty, an enchanting panoply of odors would be their fashion statements and lure insects to flowers, birds to their nests, and aliens to their lovers.

If we were able to extend our current senses in range and intensity, we could glimpse alien sense-domains. Think about bees. Bees can see into the ultraviolet range of the spectrum, although they do not see as far as we do into the red range. When we look at a violet flower, we do not see the same thing that bees see. In fact, many flowers have beautiful patterns that only bees can see to guide them to the flower. These attractive and intricate patterns are totally hidden to human perception.

If we possessed sharper sight we would see things that are too small, too fast, too dim, or too transparent for us to see now. We can get an inkling of such perceptions using special cameras, computer-enhanced images, night-vision goggles, slow-motion photography, and panoramic lenses; but if we had grown up from birth with these visual skills, our species would be transformed into something quite exotic. Our art would change, our perception of human beauty would change, our ability to diagnose diseases would change, and even our religions would change. If only a handful of people had these abilities, would they be hailed as religious saviors?

If technologically advanced aliens exist on other worlds, Earthlings have only recently become detectable to them with our introduction of radio and TV in the middle 1900s. Our TV shows are leaking into space as electromagnetic signals that can be detected at enormous distances by receiving devices not much larger than our own radio telescopes. Whether we like it or not, Paris Hilton’s sex video is heading to Alpha Centauri, and South Park and MTV are shooting out to the constellation Orion. What impressions would these shows make on alien minds? It is a sobering thought that one of the early signs of terrestrial intelligence might come from the mouth of Bart Simpson, or even worse, from the early broadcasts of Adolf Hitler

Similarly, if we receive our first signal from the stars, could it be the equivalent of the Three Stooges, with bug-eyed aliens smashing each other with green-goo pies? What if our first message from the stars was alien pornography that inadvertently leaked out into space? NASA or SETI funding would be even more difficult if the Reverend Jerry Falwell and other conservatives discovered that our first extraterrestrial message was of a hard-core “ Playboy ”—and our first images were of aliens plunging their elephantine proboscises into the paroxysmal trachea of some nubile, alien marsupial.

As hard as it may be to stomach, our entertainment will be our earliest transmissions to the stars. If we ever receive inadvertent transmissions from the stars, it will be their entertainment. Imagine this. The entire Earth sits breathlessly for the first extraterrestrial images to appear on CNN. One of our preppy-and-perfect news anchors appears on our TVs for instant live coverage. And then, beamed to every home, are the alien equivalents of Pamela Anderson in a revealing bathing suit, Beavis and Butthead mouthing inanities and expletives, and an MTV heavy-metal band consisting of screaming squids.

This is not such a crazy scenario. In fact, satellite studies show that the Super Bowl football action, which is broadcast from more transmitters than any other signal in the world, would be the most easily detected message from Earth. The first signal from an alien world could be the alien equivalent of a football game. Lesson one : We had better not assess an entire culture solely on the basis of their entertainment. Lesson two : You can learn a lot about a culture from their entertainment. 13

Music, Painting, and Plot Aesthetics

Back in the early 1990s, several artists asked the question, “What would a painting look like if it were made to please the greatest number of viewers?” The project was sponsored by the Dia Center for the Arts and used various polls. 14 They finally decided that the most-desired, most-pleasing painting in America would be one that included: (1) a calm landscape, (2) an abundance of blue color from lakes and sky, (3) people relaxing, (4) one or more deer, and (5) George Washington.

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran has suggested that some laws of aesthetics have been hardwired into the visual areas of our brains to defeat camouflage and discover hidden objects. According to Ramachandran, universal laws of aesthetics cut across not only cultural boundaries, but species boundaries as well. For example, we find peacocks and giant swallowtail butterflies beautiful, even though they evolved to be attractive to their own kind. Perhaps I love to stare at Claude Monet’s Impression: Sunrise (1872) because it gives me the feeling that my eyes are about to discover something hidden in this quiet, glowing, watery moment captured for eternity.

We’ve discussed beautiful words and paintings. But what about music? Today, a Barcelona-based artificial intelligence company, PolyphonicHMI, uses its “Hit Song Science” software to identify which new songs will likely become hits. The company also gives artists and music companies tips on how to produce such songs. PolyphonicHMI uses algorithms to analyze over 20 musical features such as tempo and rhythm, and compares these features with past hits.

Similarly, in 1921, French theater critic Georges Polti identified 36 dramatic situations into which any successful book fits. Situation 36 happens to be “Loss of Loved Ones.” The animated film “Shrek” uses 6B1 “A monarch overthrown” combined with 23, “Necessity of Sacrificing Loved Ones.” 15 Note that each major category, designated by a number, often had minor variations, designated by a letter.

Polti writes in his Thirty-Six Dramatic Situations , which is still available at Amazon.com today:

I seriously offer to dramatic authors and theatrical managers, 10,000 scenarios, totally different from those used repeatedly upon our stage in the last 50 years. The scenarios will be of a realistic and effective character. I will contract to deliver a thousand in eight days. For the production of a single gross, but 24 hours are required. Prices quoted on single dozens…

But I hear myself accused, with much violence, of an intent to “kill imagination! Enemy of fancy! Destroyer of wonders! Assassin of prodigy!” These and similar titles cause me not a blush. 16

For your amazement and joy, here are the 36 major Polti categories into which all book plots fall:

I Supplication

II Deliverance

III Vengeance of a crime

IV Vengeance taken for kindred upon kindred V Pursuit

VI Disaster

VII Falling prey to cruelty or misfortune VIII Revolt

IX Daring enterprise X Abduction

XI The Enigma

XII Obtaining

XIII Enmity of kinsmen

XIV Rivalry of kinsmen

XV Murderous adultery

XVI Madness

XVII Fatal imprudence

XVIII Involuntary crimes of love

XIX Slaying of a kinsman unrecognized

XX Self-sacrificing for an ideal

XXI Self-sacrifice for kindred

XXII All sacrificed for a passion

XXIII Necessity of sacrificing loved ones

XXIV Rivalry of superior and inferior

XXV Adultery

XXVI Crimes of love

XXVII Discovery of the dishonor of a loved one XXVIII Obstacles to love

XXIX An enemy loved

XXX Ambition

XXXI Conflict with a god

XXXII Mistaken jealousy

XXIII Erroneous judgment

XXXIV Remorse

XXXV Recovery of a lost one

XXXVI Loss of loved ones

When I went to high school, I was taught there were just three basic plots: Man against man, man against nature, and man against himself. That’s quite a contraction of plots from Polti’s 36!

These recipes for creating plots, paintings, and music could lead to some absurd results, particularly if errors or randomness crept into the recipe. When in college, I loved taking cartoons from magazines like the New Yorker and seamlessly replacing the cartoon’s caption with an unrelated cartoon caption. I’d then show the absurd composite cartoon to friends and ask them if they thought the cartoon was funny. My delight was magnified as I watched their faces as friends and strangers searched for any scrap of possible meaning when there was none. Inevitably, a friend might laugh, thinking that he was supposed to laugh, or he would laugh because the cartoon was actually funny with the wrong caption. A few people responded by punching me in the arm or shoving the cartoon at me and walking away. At no time did they realize I had performed a caption transplant.

Sometimes my sense of the absurd found its way into my books. A few publishers gave me complete license for my book content and layout, and my love for the “absurd” reached new heights when St. Martin’s Press published my book Mazes for the Mind . Why on page 417 do we find the photo of people waiting to get on a bus? There is no reason at all. Yet neither the publisher nor any readers questioned it.

In my puzzle book The Alien IQ Test , there are many more answers than there are questions! The answers themselves are often codes and puzzles in themselves. Others were just provocative pieces of coded gibberish like:

A Neanderthal jaw, from Kebara cave in Israel, clearly lacks a chin and the space behind the last molar. Tsrh hkzxv dzh kozxvw rm gsv qzdh lu Nvzmwvigszoh yb zorvm erhrglih. Fli 50,000 bvzih, Nvzmwvigszoh orevw hrwv-yb-hrwv drgs nlwvim sfnzmh rm z hnzoo ozmw.

Very few have ever asked me why these bits of flotsam and jetsam are strewn about the answer section of the book. Check out The Alien IQ Test or The Mathematics of Oz for more absurd codes and delights.

Oulipoian States of Mind

My fascination with aesthetics and words led me to study all kinds of odd literature. For example, over the centuries word-aholics have created lipograms—whole stories or books in which a particular letter of the alphabet is omitted. In 1939, American author Ernest Vincent Wright composed Gadsby , a 50,000-word novel, without using the letter “e,” the letter that occurs most often in English writing. Wright said that he tied down the typewriter bar for “e” so that he wouldn’t accidentally use the letter. The novel describes the adventures of John Gadsby as he encourages the youth of his home town of Branton Hills. Wright said in his Introduction:

In writing such a story, purposely avoiding all words containing the vowel E, there are a great many difficulties. The greatest of these is met in the past tense of verbs, almost all of which end with “-ed.” Therefore substitutes must be found; and they are very few.…The numerals also cause plenty of trouble, for none between six and thirty are available…Pronouns also caused trouble; for such words as he, she, they, them, theirs, her, herself, myself, himself, yourself, etc., could not be utilized.…The story required five and a half months of concentrated endeavor, with so many erasures and retrenchments that I tremble as I think of them. 17

I’ve delighted myself by reading much of the book. To show you the kind of work that can be produced when the brain is linguistically constrained, take a look at Gadsby ’s first two paragraphs:

If youth, throughout all history, had had a champion to stand up for it; to show a doubting world that a child can think; and, possibly, do it practically; you wouldn’t constantly run across folks today who claim that “a child don’t know anything.” A child’s brain starts functioning at birth; and has, amongst its many infant convolutions, thousands of dormant atoms, into which God has put a mystic possibility for noticing an adult’s act, and figuring out its purport.

Up to about its primary school days a child thinks, naturally, only of play. But many a form of play contains disciplinary factors. “You can’t do this,” or “that puts you out,” shows a child that it must think, practically or fail. Now, if, throughout childhood, a brain has no opposition, it is plain that it will attain a position of “status quo,” as with our ordinary animals. Man knows not why a cow, dog or lion was not born with a brain on a par with ours; why such animals cannot add, subtract, or obtain from books and schooling, that paramount position which Man holds today. 18

Later writers like Steve Chrisomalis have experimented with antilipograms in which the author must use a certain letter (for example, in every word in a poem, story or novel. Here’s a sample from Steve: “The predator alongside the feline sailed inside one pea green barge. They carried honey, their plentiful money enclosing their bounteous charge.” 19 Steve describes himself as a “word person who has an obsessive love for language. “

A French group of writers and mathematicians called the Oulipo still discuss and create literary works involving constrained writing, which provides them with a means of triggering ideas, inspiration, and mind expansion. The Oulipo ( Ouvrior de Littérature Potentielle ) have experimented with such constraints as the N +7 rule in which every noun in a story is replaced with the word that falls 7 words ahead of it in the dictionary. Thus, “Call me Ishmael” from Moby Dick might become “Call me Islander.” They also create snowball poems in which each line is a single word, and each successive word is one letter longer.

The composer Igor Stravinsky would have made a great Oulipian when he said, “The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees oneself of the chains that shackle the spirit…the arbitrariness of the constraint only serves to obtain precision of execution.” 20

Writer Mike Keith ventured into an Oulipian state of mind when he retold Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” using the constraints that the lengths of words are the values of the digits in pi. In particular, Keith’s work “Near a Raven” encodes the first 740 decimals of pi: 3.1415926.…The poem starts:

Poe, E.

“Near a Raven”

Midnights so dreary, tired and weary.

Silently pondering volumes extolling all by-now obsolete lore.

During my rather long nap—the weirdest tap!

An ominous vibrating sound disturbing my chamber’s antedoor.

“This,” I whispered quietly, “I ignore.” 21

Keith is also author of The Anagrammed Bible— an “anagrammatic paraphrase” of the Old Testament. Anagrams are words or phrases spelled by rearranging the letters of another word or phrase. For example “Britney Spears” and “Presbyterians” are anagrams of each another. In Keith’s book, the letters in each verse (or, in some cases, block of verses) from the King James Version Bible are transformed into a new text with a similar meaning using anagrams (scramblings) of the original. So, for example, “My son, hear the instruction of thy father, and forsake not the law of thy mother” (Proverbs 1:8) becomes in The Anagrammed Bible : “When thy mom talketh of honesty, of trust, and of honor, carry it safe in the heart.” 22

In 2001, Christian Bök published Eunoia , which includes five chapters, each one of which is a prose poem using words with only one of the five vowels. “Eunoia” is also the shortest word in the English language to use all five vowels. More recently, Brian Raiter wrote a paper titled “Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in Words of Four Letters or Less” — an explanation of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity using words no more than four letters long, with paragraphs like:

So you see, when you give up on the idea of a one true “at rest,” then you have to give up on the idea of a one true time as well! And even that is not the end of it. If you lose your one true way to see time, then you also lose your one true way to see size and your one true way to see mass. You can’t talk of any of that, if you don’t also say what it is you call “at rest.” If you don’t, then Bert or Dana can pick an “at rest” that isn’t the same as what you used, and then what they will get for time and size and mass won’t be the same. 23

“A Glass Centipede”

I’ve been exploring computer-generated poetry and automatic invention creation for decades. 24 Experiments with the computer generation of poetry, Japanese haiku, and short stories provide a creative programming exercise for both beginning and advanced students. Computer-created poetry and text also provide fascinating avenues for researchers interested in artificial intelligence and “teaching” the computer about beauty and meaning. My own introduction to computer art and poetry came from Jasia Reichardt’s book, Cybernetic Serendipity . I requested this amazing book as part of a science prize I won in high school, and this book stimulated me more than any other with respect to using the computer for artistic pursuits. The book planted the seed for all my later art, which has appeared on TV shows, on magazine covers, and in museums.

Past work in computer-generated prose includes the book The Policeman’s Beard Is Half Constructed— the first book ever written entirely by a computer. The program that generated the book was called RACTER, written by William Chamberlain and Thomas Etter. Ray Kurzweil, in The Age of Thinking Machines , notes that “ RACTER’s prose has its charm, but is somewhat demented-sounding, due primarily to its rather limited understanding of what it is talking about.” Some people have suggested that The Policeman’s Beard Is Half Constructed also required significant human input to give the text a greater sense of meaning than could be expected from a purely artificial generation process. Here’s an excerpt:

More than iron, more than lead, more than gold I need electricity. I need it more than I need lamb or pork or lettuce or cucumber. I need it for my dreams. 25

A reviewer at Amazon.com notes that it “won’t win any award for insight or style, but, even so, Racter may make more sense than Joyce’s Finnegans Wake .”

Finally, consider the Kurzweil Cybernetic Poet, a computer poetry program that uses human-written poems as input to create new poems with word-sequence models based on the poems it has just read. When these computer poems are placed side by side with human poems, it is difficult to determine which poems were made by humans and which by the Cybernetic Poet.

On November 11, 2003, Ray Kurzweil and John Keklak received U.S. Patent 6,647,395 for software that creates poetry. These programs read a selection of poems and then create a “language model” that allows the program to write original poems from that model. This means that the system can emulate words and rhythms of human poets to create new masterpieces. The system can also be used to motivate human authors who have writer’s block and are looking for help with alliteration and rhyming.

I am interested in computer-generated poetry because the strange images tweak our minds, inducing creativity and generating novelty, much like some psychedelic drug experiences. Computer-produced texts are a marvelous stimulus for the imagination when you are writing your own fictional stories and are searching for new ideas, images, and moods. Even visual artists can use computer-generated poems as a stimulus for ideas and a vast reservoir of original material.

Let me give you some hints on how I write simple programs for generating computer poetry. The several sets of three-line computer poems that follow were all generated by the random selection of words and phrases that are placed in a specific format, or “semantic schema.” My program starts by reading thirty different words in each of five different categories: adjectives, nouns, verbs, prepositional phrases, and adverbs. The words are chosen at random and placed in the following semantic schema:

Poem Title: A (adjective) (noun 1).

A (adjective) (noun 1) (verb) (preposition) the (adjective) (noun 2).

(Adverb) the (noun 1) (verb).

The (noun 2) (verb) (prep) a (adjective) (noun 3).

The fact that “noun 1” and “noun 2” are used twice within the same poem produces a greater correlation—a cognitive harmony—giving the poem more meaning and solidity.

If your computer has access to a thesaurus, you may induce further artificial meaning in the poems. This would be accomplished by using the thesaurus to force additional correlations and constraints on the chosen words. Without further ado, here is some output from my program:

“A Lost Sapphire”

A lost sapphire frowns at the thin kidney.

With a terrible shutter, the sapphire runs.

The kidney squats in synchrony with a green unicorn.“A Hungry Wizard”A hungry wizard chatters far away from the dying tongue.

With great deliberation, the wizard disintegrates.

The tongue oscillates above a milky limb.“A Glass Centipede”

A glass centipede drools inches away from the shivering knuckle.

While feeding, the centipede regurgitates;

The knuckle shakes a million miles away from a buzzing flake.“A Robotoid Magician”

A robotoid magician implodes on the brink of the blonde chasm.

While feeding, the magician cries;

The chasm gyrates at the end of a crystalline prophet.

“A Wavering Kidney”A wavering kidney disintegrates deep within the glistening wizard.

While shivering, the kidney dances;

The wizard gesticulates at the tip of a dying avocado.“A Fairylike Knuckle”

A fairylike knuckle yawns in harmony with the sensuous knuckle.

While waving its tentacles, the knuckle runs;

The knuckle buzzes a million miles away from a black kidney.“A Blonde Wizard”

A blonde wizard screams near the happy ellipse.

In mind-inflaming ecstasy, the wizard disintegrates;

The ellipse grows while grabbing at a lunar mountain.“A Religious Ocean”

A religious ocean explodes far away from the percolating flame.

With great speed, the ocean oscillates;

The flame phosphoresces while grabbing at a dying jello pudding.

See the footnote for a few more poems of this kind. 26

Pynchonomancy

Controlled randomness in the form of “stichomancy” is an ancient way of generating ideas . Stichomancy is divination by throwing open a book and selecting a random passage. Over the millennia, practitioners actually used this approach in an attempt to predict the future.

An important type of stichomancy is bibliomancy, which usually restricts itself to the use of holy books. Stichomancy was practiced by the ancient Greeks and Romans. Often the works of Homer or Virgil were used and are still used today. More modern stichomancers use the works of Shakespeare, Nostradamus, or Edgar Cayce.

I have personally tried stichomancy as a way to stimulate my mind. It’s sometimes useful for coming up with inventions and new ways of looking at a problem. For example, I have randomly taken phrases from patents and then combined them to get ideas for new patents. Here is the traditional method of stichomancy for answering questions:

For example, let’s say you choose Tales of Power by Carlos Castaneda and open to a random page. You read the following: “The conditions of a solitary bird are five: First, that it flies to the highest point. Second, that it does not suffer for company, not even of its own kind. Third, that it aims its beak to the sky. Fourth, that it does not have a definite color. Fifth, that it sings very softly.” For the rest of the day, think about how this relates to your current questions about life.

Various stichomancy sites exist on the World Wide Web that will select random passages from random books for you. My colleagues also use a related divination method called “Pynchonomancy,” or divination by throwing darts at a paperback edition of Thomas Pynchon’s novel Gravity’s Rainbow . After throwing a dart, the diviner looks at the last page penetrated and reads the sentence or paragraph intersected by the dart to gain insight.

Unfortunately, the practitioner of this form of stichomancy must replace the book every few months because the book tends to fall apart and becomes difficult to read. (I am told that publishers enjoy this divination method.) One anonymous Interneter told me that he used Pynchonomancy and said he goes so far as to use this method to determine the nature and duration of his sexual activities, in addition to using the approach to solve problems and predict future trends.

The practice of throwing darts at books reminds me of Hebrew scholars from Poland in the early 20th century, who were able to recall the entire contents of the thousands of pages in the twelve-volume Babylonian Talmud. Some had such good memories that, when a pin was pushed through the pages of a volume, the hyper-scholar could recall each of the words pierced by the pin.

Although I am a skeptical scientist at heart, I have performed some ad hoc “divination” myself that has yielded some interesting results. For example, if I want an answer to a pressing question or am simply trying to locate something I misplaced, I sometimes focus on the problem when I go to sleep and often have the answer in the morning. As I have mentioned, I also keep a paper pad near the bed for jotting ideas that occur in the middle of the night. It seems that the subconscious has access to information that our conscious minds don’t have, and sleep and dreams can occasionally be used to access that information.

Sometimes I even perform abstract divination where, in my mind, I scatter dust and dirt into the wind and visualize the resultant color. The beauty of the resultant colors gives me ideas as to the favorableness of a certain action. For example, a pretty violet symmetrical pattern is favorable, but a muddy, dark, congealed mess is unfavorable. I know this sounds quite weird, but again, it probably works because I subconsciously access information that doesn’t quite break through into my conscious mind.

The visualization method of spreading colored dust might seem difficult at first, but I routinely practice visualization methods as I go to sleep, such as rotating objects like horses in my mind or sinking in a black pool of liquid while looking up at the water surface until it becomes a bright white slit “miles” above me.

I even use a related form of divination to create patents. I make a list of devices in column A and a list of attributes or features in column B, and have a computer program generate an invention title by randomly choosing a device and a feature. If one can think of suitable application for the invention, it is relatively easy to embellish the basic concept and generate patentable ideas.

Today computer-aided invention production is all the rage. For example, Stephen Thaler, the president and chief executive of Imagination Engines Inc. in Maryland Heights, has invented a computer program called a Creativity Machine, also known as “Thomas Edison in a box.” He now has patent US 5,659,666 for his “Device for the Autonomous Generation of Useful Information.” This was his first patent. His second patent, US 5,845,271 for his “Self-Training Neural Network Object,” was invented by the device portrayed in Thaler’s first patent! When I talked to Thaler about his first patent, he told me that his patented creativity machine (patent 5,659,666) provides a means to make neural networks proactive, granting them the “free will” and the flexibility to escape the knowledge contained within their learning and to produce novel concepts and courses of action. 27

His Web page goes on to say, “The effect these virtual machines are based upon is exceedingly simple and straightforwardly controllable: A normal neural network that has been exposed to any knowledge domain and then repeatedly subjected to mild internal disturbances, tends to produce a mixture of both intact memories and unusual juxtapositions of those memories that are unprecedented in the net’s experience. In effect, the network is mildly hallucinating; manufacturing novelties derived from its own unique microcosm.” 28

My Private Word Collection

As I mentioned, I’ve been collecting colorful words and phrases since high school. A few years ago I compiled a science-fiction phrase book to help budding science-fiction writers dress up their stories. I had even sent the book to Isaac Asimov who said he personally did not need such a book but that he would pass it on to one of his editors. Alas, no publisher was interested in it, although similar books have been published such as Jean Kent and Candace Shelton’s Romance Writer’s Phrase Book, which is a list of colorful phrases and words that novelists could steal and use.

In any case, my phrase book could have been used when writers are searching for new ideas, images, and emotions. Much of my phrase list was finally published in my book Computers and the Imagination . Arranged for quick, easy reference, the chapter contains over 1,000 descriptive phrases, commonly known as “tags”—those short, one-line descriptions that make the difference between a cold, factual fictional work and an inspired, pulsating story. Here’s how:

Without tags : The bird flew toward the sun.

With tags : With wings spread and motionless, a solitary seabird glided toward the shattered crimson disc of the sun.

Even seasoned novelists use memetic ticklers to give a good story even more sparkle and more life. Just as an example, renowned science fiction writer Harlan Ellison in Partners in Wonder describes how, early in his writing career, he frequently used the device-image of someone shoving his fist in his mouth to demonstrate being overwhelmed by pain or horror. Similarly, S. R. Donaldson, best-selling author of the Thomas Covenant fantasy series, makes frequent use of pet words. For instance, the relatively obscure word “cynosure” (a center of attraction) appears at least once, and usually more often, in most of the books in the series.

Most readers seem to like Donaldson’s use of unusual words, though perhaps he teeters close to overdose in such wonderful paragraphs as this one from his book The One Tree :

And these were only the nearest entrancements. Other sights abounded: grand statues of water; a pool with its surface woven like an arras; shrubs which flowed through a myriad elegant forms; catenulate sequences of marble, draped from nowhere to nowhere; animals that leaped into the air as birds and drifted down again as snow; swept-wing shapes of malachite flying in gracile curves; sunflowers the size of Giants, with imbricated ophite petals. And everywhere rang the music of bells—cymbals in carillon, chimes wefted into tapestries of tinkling, tones scattered on all sides—the metal-and-crystal language of Elemesnedene. 29

I just love those “imbricated ophite petals”! Incidentally, H. P. Lovecraft also enjoyed using unfamiliar adjectives like “eldritch,” “rugose,” “cyclopean,” and “squamous.”

Antonin Artaud

While still on the topic of words and language, I can’t resist mentioning French playwright Antonin Artaud, who once said, “All true language is incomprehensible, like the chatter of a beggar’s teeth.” I was never 100 percent sure as to what he meant by this, and many people considered him insane. Perhaps Artaud would agree with the observation my friends at work often make: “When people talk, what is actually communicated is often much less than what each party intended to communicate.”

Antonin Artaud (1896–1948) was a philosopher and glossolaliac who consumed peyote with the Tarahumara Indians of Mexico. He believed that peyote triggers the brain to remember “supreme truths” difficult to obtain by other means. While using peyote, he saw shapes rise from his belly that looked like the “letters of a very ancient and mysterious alphabet.” The letters J and E in particular rose and glowed fiercely.

His final radio play was “To Have Done with the Judgment of God.” Artaud wrote this odd piece while in psychiatric institutions, where he was essentially tortured with excessive electroshock and other therapies. He wrote, “I myself spent nine years in an insane asylum, and I never had the obsession of suicide, but I know that each conversation with a psychiatrist, every morning at the time of his visit, made me want to hang myself, realizing that I would not be able to cut his throat.”

In 1947, the director of dramatic and literary broadcasts in France commissioned “To Have Done with the Judgment of God,” which dealt with consciousness and knowledge, and it was recorded in the final months of 1947. Alas, the broadcast was canceled at the last minute due to its bizarre content, and Artaud dropped dead almost immediately after the cancellation. The “Judgment of God” was not broadcast until the late 1980s.

The radio play ends with a scene in which God lies on an autopsy table. God resembles a body organ removed from the imperfect corpse of humankind. Artaud wanted this closing scene to be superimposed with screams, moans, grunts, snuffling, and glossolalial nonsense words created by Artaud. I do not know if the actual broadcast ended according to Artaud’s wishes.

Artaud wrote, “There is in every madman a misunderstood genius whose idea, shining in his head, frightened people, and for whom delirium was the only solution to the strangulation that life had prepared for him.” 30

In the previous chapter, we discussed names of God and the use of Hebrew letters for coding God’s name. It is fascinating that people hallucinate letters while using certain drugs, as Artaud did when using peyote. Writer Daniel Pinchbeck also saw letters in one of his LSD-induced psychedelic visions. In particular he saw Hebrew letters “pouring forth from a funnel-shaped geometric mandala.”31

The Mystery of Italics

Sometimes the Hebrew and other ancient alphabets seen in drug visions are swirly and slanting, like a hyper-italic font. In my books, I try to use italics only sparingly because it is harder to read than nonitalic type. I always thought italics looked rather exotic. Today, italics have invaded every aspect of our lives. However, as I poll passersby on the streets of Shrub Oak, I find that not a single person knows when italics was invented, why it was invented, or by whom it was invented. For virtually everyone alive today, the origin of italics is a mystery.

Let me tear away the veils of this mystery. Italic type, with words slanted like this , was invented around 1500 by Italian printer Aldus Manutius. Manutius used italics in a dedication for a book of works by Latin poet Virgil. Manutius’s dedication was for his native Italy. The font was based on the cursive handwriting called Cancelleresca, used in the government offices of Venice and other Italian city-states. This new slanting style came to be known as Italicus, which means Italian.

The use and meaning of italics has changed through the centuries. For example, words in the King James Bible were often italicized when an editor supplied missing or useful words not existing in the original text to make the text easier to understand. Currently italics are used for emphasizing certain words or phrases, when indicating book or film titles, and to specify words in languages foreign to the language in which a work is written.

Amphigory

My computer poetry, cutup cartoons with incorrect captions, the works of RACTER , and Artaud’s writings seem to precariously ride the waves of meaning, close to the edge of insanity and chaos. The term “amphigory” usually refers to a poem or other piece of text that appears to be coherent but, upon closer inspection, contains no meaning! One of the best examples is “Nephelidia,” a poem by English Poet Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909). The poem captures the style, alliteration, and rhythms of his other meaningful poems. Here are the first few lines:

“Nephelidia”

From the depth of the dreamy decline of the dawn

through a notable nimbus of nebulous noonshine,

Pallid and pink as the palm of the flag-flower

that flickers with fear of the flies as they float,

Are they looks of our lovers that lustrously lean

from a marvel of mystic miraculous moonshine,

These that we feel in the blood of our blushes

that thicken and threaten with throbs through the throat?

Thicken and thrill as a theatre thronged

at appeal of an actor’s appalled agitation,

Fainter with fear of the fires of the future

than pale with the promise of pride in the past;

Flushed with the famishing fullness of fever

that reddens with radiance of rathe recreation,

Gaunt as the ghastliest of glimpses that gleam

through the gloom of the gloaming when ghosts go aghast?

The remainder of “Amphigory” is in Note 32. For some of my own experiments with amphigory, words, books, and the Google Web page, see Note 33.

World’s Largest Vocabulary

English has the world’s largest vocabulary, with over 800,000 words (including technical words), in part because English borrows words from many other languages. Consider for example the sentence:

The evil thug loafed beside a crimson table, drinking tea, and eating chocolate, while watching the girl wearing the angora shawl.

Thug is a Hindustani word. Loafed is Danish. Crimson is from Sanskrit.

Tea is Chinese. Chocolate is Nahuatl. Angora is Turkish. Shawl is Persian.

Numerous English words were originally French, added to an essentially Germanic language. English also absorbed words from Latin because of the influence of Medieval and Renaissance scholars and the church. Running the world’s greatest empire meant that the British were exposed to more other languages than any other imperial power. Harvard Professor Steven Pinker notes that our large vocabulary allows us to be more concise, because a speaker is free to choose a single word with just the right shade of meaning. He suggests that a document in English translated into French is 20 percent longer—“that’s the price the French pay for having an academy that keeps out words.” 34

I might add that the number of words needed as we transit between languages also has do with syntax and spelling conventions. In German Bundestag is one word, whereas Federation parliament in English is two and chambre de deputés de la fédération in French is six.

These days, it becomes increasingly difficult to determine the number of words in a language, particularly now that English words are making significant penetration into other languages. English has become the language of international communication and is becoming even more dominant as the Internet unites the planet. Although Chinese is spoken by the most people, English is the most widely spoken second language.

Despite the huge English vocabulary, author Stuart Berg Flexner in I Hear America Talking notes that ten simple words account for 25 percent of all English speech, 50 words account for 60 percent, and just 1,500 to 2,000 words account for 99 percent of all that Americans say. Extremely

smart and educated people may use as many as 60,000 English words, or about 7.5% of the entire English vocabulary.

The Return of Joumana

I’d like to conclude this smorgasbord of a chapter with a short interview with Joumana Medlej, the Lebanese journalist and designer whom I mentioned in the previous chapter.

C LIFF : Joumana, do you really think that language shapes our perception of reality?

J OUMANA : I believe language creates a structure in our minds through which we perceive reality. Although language was originally shaped to reflect reality, because a single human life is so much shorter than the life of the language, language ensures that the new generations’ minds grew within this mold. The process is in truth back-and-forth, humanity shaping language shaping humanity, but on the scale of the individual the only significant influence is that of the language on the person.

C LIFF : Do you think people or cultures with large vocabularies perceive the world differently than those with smaller vocabularies?

J OUMANA : To some extent, yes. It is not that the former see or hear more things than the latter. Rather, having a word for something means there is awareness of its existence as a separate entity. The English language only has the word “love” where the ancient Greeks had “eros,” “philos” and “agape.” This allowed the Greeks to easily understand three separate emotions, whereas English speakers may sense that it is unnatural to have a single word for a wide panoply of emotions, and compensate with more elaborate descriptions (“I love you like a brother”). In this example, it is not that English speakers can’t feel what the Greek did—not at all, it’s simply that they don’t have the linguistic tools to validate a certain feeling as something experienced by many. That is the primary function of language: connecting a concept in one person’s mind to the same concept in another person’s, by convention. When a vocabulary is poor, the excluded concepts remain an individual, unshared, undefined experience.

C LIFF : Can you give another example?

J OUMANA : To a significant number of Americans, there exists only one word to designate the populations of the Middle-East—“Arabs.”

Consequently, it is very difficult for them to realize that they are not dealing with a single homogeneous bloc where I live, but with a number of very different cultures. Yet today languages are interacting in unique ways and giving people the opportunity to discover and comprehend concepts that don’t exist in their own tongue. It’s very exciting, even though it means a loss of linguistic innocence.

C LIFF : Do you think Hopi Indians may have a better chance of understanding quantum mechanics (or modern theories of physics that say time is an illusion) than non-Hopis? Why?

J OUMANA : I would rephrase the question as “than certain non-Hopi cultures,” because certain other cultures are already equipped to understand the paradox at the heart of quantum physics. Western cultures have issues with it because they leave no room for paradox. Their languages are very keen on fragmenting the world and labeling each part very clearly and unambiguously. The Hopi language, on the other hand, classifies things differently, without necessarily separating them. Their minds are already trained to grasp juxtaposed states that would look irreconcilable to Westerners.

C LIFF : What about the mind of someone who speaks more than one language?

J OUMANA : Being Lebanese, I was raised speaking three very different languages: one Anglo-Saxon, one Latin, and one Semitic. It is very interesting to observe how the early implantation of different patterns in your mind, instead of just one, makes you highly adaptable and resourceful in life in general. I would compare it to having a 64-bit system as opposed to a 4-bit: thinking is much more subtle.

If you listen in on a Lebanese conversation, you’ll notice that it is unavoidably conducted in two or three languages at the same time: The speakers unconsciously use the most appropriate word at all times, bringing it in from a foreign language if it doesn’t exist in Lebanese so that no gaps are left, no concepts left undefined. This is significant because it means that they are equipped to recognize foreign concepts and when faced with new ones, won’t unconsciously try to bend them to a familiar pattern of thinking. 35

If language and words do shape our thoughts and tickle our neuronal circuits in interesting ways, I sometimes wonder how a child would develop if reared using an “invented” language that was somehow optimized for mind-expansion, emotion, logic, or some other attribute.

Perhaps our current language, which evolved chaotically through the millennia, may not be the most “optimal” language for thinking big thoughts or reasoning beyond the limits of our own intuition. If certain computer languages are more suited for modularity, size, speed, or ease of use, could certain human languages be optimized for human growth potential, creativity, memorability, or for communicating one’s thoughts and emotions?