By the time he was ten, Philip had acquired so many doctors, if you had laid them end to end they would have stretched from the top of the cul-de-sac to the main road. They peered into his eyes and ears, while their machines peered into his brain, and they used long words that no one except doctors ever understood.

Mostly they just stared, probably hoping something extraordinary …*

would erupt from Philip’s ears, which might explain why he was completely fearless in the face of danger, and could remember all sorts of mathematical equations, but nothing else.

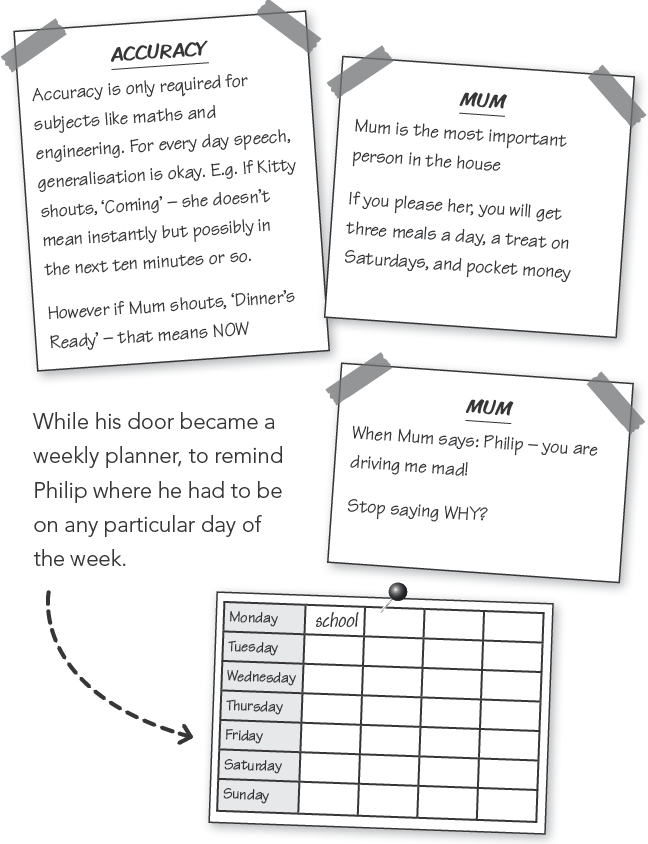

For Philip, even remembering ordinary things was a problem, which is why he carried a notebook to write everything down, while the walls in his bedroom began to fill up with posters.

Mrs Longbotham finally gave up on doctors when they introduced the word concept into the conversation. She had become used to their using long words to describe her son, such as extraordinary, amazing and brilliant. However, the word concept generally followed sentences which began, ‘Unfortunately Philip has no understanding of …’ followed by words such as:

danger, fear, pain and spacial awareness.*

‘What concept are you talking about now?’ Mrs Longbotham asked the doctor.

‘Prettiness,’ he said, studying the clipboard in his hand.

Mrs Longbotham groaned.

‘Are you ill, Mum?’ Philip asked.

Mrs Longbotham shook her head, dreading what was coming next.

‘Philip recognises the human form of course,’ the doctor began not looking up, something that Mrs Longbotham knew from long experience was an ominous sign.

‘Of course,’ she said.

‘I understand he has two older sisters?’

She nodded.

‘I expect they are both drop-dead gorgeous.’ The doctor laughed. ‘Smokin’ is the modern saying, I believe.’

Mrs Longbotham said quickly, ‘Philip wouldn’t understand that term.’

‘I wouldn’t expect him too,’ the doctor sounded irritated. ‘But I would expect him to understand the word pretty.’

Mrs Longbotham closed her eyes and leaned back in her chair.

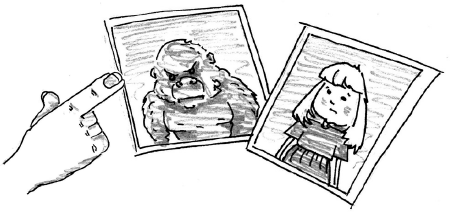

‘Philip was shown two pictures; the first a beautiful film star, the second a gorilla. When asked which one was the prettiest, he pointed to the gorilla.’

On the way home, she asked, ‘Why the gorilla?’

‘The gorilla what, Mum?’ said Philip, having completely forgotten the earlier conversation.

‘You told the doctor that the gorilla was the prettiest.’

Philip’s brain kicked in. ‘I remember,’ he said. ‘The girl’s eyes were big and round and empty. I chose the gorilla because its eyes spoke to you.’

Mrs Longbotham took her son’s hand and hugged it to her heart. ‘I think we’ve had enough of doctors, Philip,’ she said. ‘We’ll manage on our own from now on. But perhaps a new poster.’

Philip nodded happily.

Of the two people who eventually explained to Philip how his brain worked, the first was Mrs Edwards. She was his Year 5 teacher. She had a grown family of her own and told everyone who asked, that she had learned about children the hard way.

Philip thought her fantastic, because she never got angry and didn’t use words like: ‘You’re driving me bonkers,’ which his sisters said all the time, or der brain, which the kids in his class called him. She also spoke proper English which Philip understood perfectly.

‘Your brain is like a rook. You know, as in chess,’ she said.

Since Philip was super-duper at chess and had already beaten everyone in primary school, he understood immediately.

‘You mean it can only move in straight lines?’

‘Exactly.’

‘Is that why I’m good at maths and science?’

Mrs Edwards nodded. ‘Better than good – brilliant.’

‘And why I’m rotten at English.’

‘I wouldn’t say … er … rotten, Philip.’

‘Kitty would,’ he gloomed.

Mrs Edwards, who had had the privilege of teaching Kitty some years previously, and remembered her very well indeed, sighed loudly. ‘Perhaps we could say your English is unusual.’

Philip nodded. ‘So why does my brain seize up and why do I forget things?’

‘I can’t explain why you forget things but I think your brain seizes up when it’s overloaded with too much information. Remember the other day in the school yard, when that boy fell off the climbing frame? There was a lot of confusion, with kids screaming and shouting. I expect your brain couldn’t cope – so it shut down.’*

Philip shook his head. ‘I don’t remember. It’s okay though, I never do.’

It was Kitty who eventually explained to Philip why he forgot things, although even she took a couple of goes to get it right.