Minimizing Pain

PAIN IS ONE OF THE SYMPTOMS that palliative care specialists and oncologists take the most seriously. Not everyone who has cancer gets pain, but if you do have pain, we want your pain to be well controlled, because living with pain is so exhausting. You can’t be yourself and do the things you love to do if you are constantly thinking about pain. And yet, this is the one area where patients seem to struggle the most to communicate how they feel. So many times I hear patients say, “Well, it hurts so much that I can’t walk, but I don’t want to take anything.” Or they say, “I can’t sleep at night, but if I take something won’t I become an addict?”

You should never expect to live with unmanaged pain, and if your pain is interfering with your daily life, keeping you bedridden, or even keeping you from spending time with your family, you need help.

The experience of pain is intensely personal, something that can make you feel vulnerable and even anxious about the future, and I understand that some people feel uncomfortable talking about it. Many times patients will tell an oncologist—even one they really like and trust—that they have no real problems with pain. Then, on the same day, they come to an appointment with me or with someone in palliative care, and the first subject they want to discuss is how they can’t sleep because of the pain or how the medication offered so far isn’t helping. When I ask why they didn’t bring this up with the oncologist, the answers are often similar:

You should never expect to have poorly controlled pain just because you have cancer, and nobody will think you are weak. While new or increasing pain might be a sign that the cancer is advancing, it might be due to something else entirely. Your oncologist wants to help you manage pain, and most oncologists have training in pain management. But sometimes pain is tricky to manage, and it may require more than one medication or strategy. You have to continue to communicate your symptoms so that the doctor can figure out the right approach to treat not just the pain but the cancer itself. If your doctor has prescribed a pain regimen that isn’t working, you need to speak up so that he or she can make adjustments or consult with a pain specialist like a palliative care clinician.

Describing the Intensity of Pain

At every visit to the clinic, someone in your medical team should be asking you whether your pain is acceptable and whether pain is interfering with your normal life. You will be asked whether you have any new pain. This is called a pain assessment. If you do have pain, you will be asked to describe its intensity and qualities. Is it dull or sharp? Can you easily identify the location, or is the pain diffuse? Is it a shooting pain that seems to radiate from one point to another? Does it burn or ache? Is it intermittent or constant? Does it increase or decrease at certain times of day? Is it worse when you move or sit or stand in a certain way?

These are not idle questions. If you develop new areas of discomfort, your doctor needs to know about it. Even if you don’t think that your pain is related to your cancer, you should still discuss it with your doctor. The sudden emergence of back pain or pain in your bones can alert your medical team to changes in your health. Also, some patients experience pain in areas that have nothing to do with their tumors.

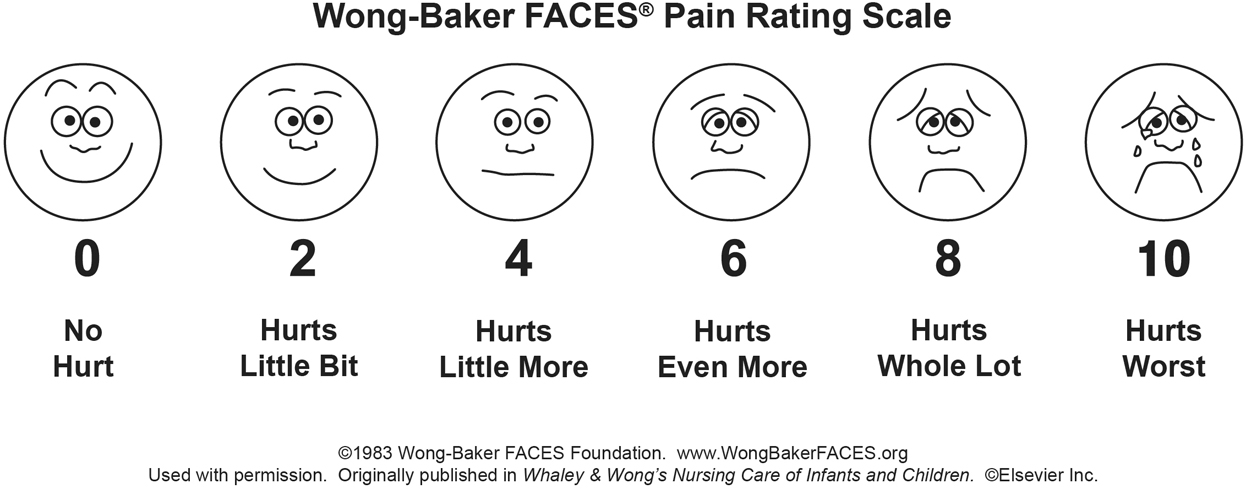

Figure 11.1 Wong-Baker FACES pain rating scale. Wong-Baker FACES Foundation (2015). Wong-Baker FACES® Pain Rating Scale. Retrieved August 19, 2016, with permission from http://www.WongBakerFACES.org.

Your doctor will ask you to rate your pain on a scale of 0 to 10 and might present you with a pain scale with numbers and faces on it. Figure 11.1 shows the kind of scale your doctor might use.

This scale is confusing for many people, and some patients are tempted to make their own sad or snarky face whenever presented with it. But doctors understand that pain is subjective, and your sensitivity to pain will be affected by other factors, including your general health, your mood, your level of fatigue. I typically explain it this way: it is unlikely that you will have 0 pain but more likely that we will be able to keep your cancer pain in the 1 to 2 range. The low end of the scale, 1 to 3, represents pain that you notice but that doesn’t interfere with your life. With a pain level of 2, most patients can still read the paper or engross themselves in a movie. You can ignore it enough to continue to do almost everything you want. Sometimes your doctor will tell you to treat this pain with over-the-counter analgesics like acetaminophen or ibuprofen. Please don’t take these medicines without asking someone on your medical team. There may be reasons your doctor wouldn’t want you to treat chronic pain with these types of medications, and there may be better solutions for you.

Moderate pain, between 4 and 6, represents pain that interferes with your daily activities. As part of my pain assessment, I always ask, “Is there anything that you want to do that you can’t do because of the pain?” The answer to this question helps me to know how to best treat the pain. Sometimes patients are fine if they are sitting but then have pain when they get up to walk, while other patients have pain that worsens when they are lying in bed, making it difficult to get a good night’s sleep. Moderate pain almost always requires treatment with an opioid pain medication such as morphine or oxycodone. Some people are startled by the names of these medications, because they are so often associated with recovery from surgery, but you will likely be starting at a low dose.

If your moderate pain is intermittent, meaning that it comes and goes, you might take an opioid as needed. However, if the pain is constant, your doctor might suggest that you take a short- or long-acting medication on a regular schedule. I am never worried about how much or what type of medication is needed to treat the pain as long as the patient has good pain control and few side effects from the medications.

Severe pain, anything above a 7, is serious and something your doctors will want to treat aggressively. In this situation, you might have a tough time doing anything but think about the pain. Some patients have told me that they have to hold perfectly still or they have to keep pacing to manage the pain. Your team needs to know about this kind of pain immediately. With the right treatments, even severe pain can be made better. Remember, our goal is to get the pain intensity down to that 1 to 2 range. We might not be able to eliminate your pain, but we can reduce it enough to improve your quality of life. Doctors often combine medications and treatments to reduce severe pain.

For example, I met Sarah shortly after she was admitted to Mass General with a diagnosis of breast cancer. Breast cancers tend to metastasize (spread) to the bone, and Sarah was having terrible pain in her left hip from a bone metastasis.

The pain was so bad that she couldn’t walk, stand up to shower, or spend time with her family. In fact, she told me that she had to slide herself across the floor to get from one room to another and that her children were really frightened by this. In fact, she cried when she described her children’s fears to me. And yet, when I asked her about taking medication for pain, she told me that she thought she should be tough enough to handle the pain, even though the scans revealed that she had a large tumor in the bones of her pelvis.

Before her diagnosis, Sarah had been incredibly active and fit. She played competitively in a women’s hockey league two to three times a week. Her children and husband also played hockey. “This is what we do together,” she told me. “This is important to me. I want to play hockey again.”

I started her on short-acting opioid oxycodone every three hours and ibuprofen every eight hours. This improved her pain in the short term so that she could function more normally. In addition, she started radiation to reduce the pain in her hip. I also started her on a low dose of long-acting oxycodone, which is a pain medication that lasts eight to twelve hours. Most patients with cancer pain need a combination of long- and short-acting pain medications if they have steady pain in addition to acute pain with some activity.

With these medications, Sarah had her pain down to a 2 out of 10. After radiation and some physical therapy, she was able to go back to playing hockey, and she felt like herself again.

Treatments for Pain

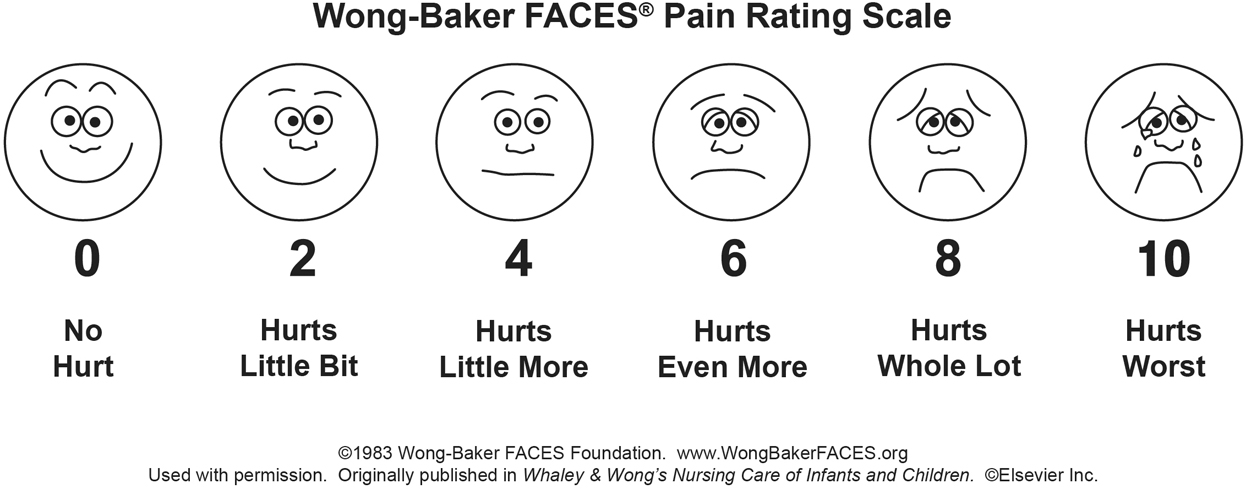

Actively engage your medical team about the symptoms of pain and how treatments are working. You can copy table 11.1 and use it to track your symptoms and the effectiveness of any treatments you receive. This will help your medical team assess your dosage and recommend alternatives if your current medication isn’t working or has too many side effects.

Nonopioid Pain Relievers

Ibuprofen and naproxen are both nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, commonly called NSAIDs. These medications can be incredibly helpful in treating any pain caused by inflammation, including bone pain. In truth, most types of pain have some inflammatory component, which is why NSAIDs are so often prescribed. You do need to be careful, though. These medications can cause irritation in the stomach and even lead to an ulcer, so they should be used in conjunction with a medication that reduces the stomach’s production of acid, such as omeprazole or another proton pump inhibitor. Even with these additional drugs, you can still develop an ulcer. NSAIDs can also affect the kidneys and how they function, so they need to be used very cautiously in patients with kidney problems. Your doctor will want you to monitor for any signs of bleeding while taking an NSAID.

TABLE 11.1 Tracking pain and pain management at home

Your clinician will be also looking for other nonopioid treatments for your pain. Acetaminophen can be helpful as an extra medication to treat pain. Other medications such as gabapentin or tricyclic antidepressants can be helpful in the treatment for neuropathic (nerve) pain. These can be prescribed before opioids or in conjunction with opioids.

Short-Acting Opioids

Most patients will require the addition of a short-acting opioid pain medication like morphine or oxycodone to effectively manage cancer-related pain. These medications bind with opioid receptors in areas of the body, including the brain and spinal cord, and reduce your perception of pain. Most short-acting opioids take about an hour to reach peak effect and last somewhere between two and four hours, depending on the intensity of the pain.

If you have intermittent pain or pain associated with a particular activity, you know that the pain might start slowly and peak for a time before it starts to fade. Your doctor may tell you to take a short-acting opioid when the pain starts, so that it increases in effectiveness as the pain increases and then fades roughly when the pain itself will fade. It may be tempting to wait as long as possible before taking the pill, thinking that you should tough it out. But when you do that, you risk doing what we call “overshooting the pain.” That means that the opioid takes full effect after the pain has gone away, and that might leave you feeling groggy when you want to be more alert.

One caution using short-acting opioids: it is best to use preparations that do not contain acetaminophen or ibuprofen as a combination product. The reason is that you may need the short-acting opioid every three hours to manage your pain, but it is not safe to take acetaminophen or ibuprofen that frequently. We recommend dosing acetaminophen or ibuprofen separately from the short-acting opioid.

Long-Acting Opioids

If you find yourself taking a short-acting opioid at regular intervals throughout the day, your doctor may suggest that you switch to a long-acting opioid, which is a similar medication but the effects last for many more hours. Table 11.2 lists common long-acting opioids. Many opioids come in a long-acting form. Oxycodone and morphine both have long-acting pills that last eight to twelve hours. These are also known as controlled-release or extended-release oxycodone. Although manufacturers suggest taking a new dose every twelve hours, we have found that it is not uncommon for the pain relief to fall short of the full twelve hours, and you may need to take a new dose after eight. Fentanyl comes in a patch that goes on the skin and typically lasts seventy-two hours. Methadone is another opioid that can be used as a long-acting medication, but it works a bit differently and requires special precautions, so I will describe it in a separate section.

Most often in the outpatient setting we start with medications taken by mouth or patches that are placed on the skin. Many clinicians like to start with oral medications if possible, because it is easier to adjust the dosage as needed. Your doctor may suggest a fentanyl patch if you are having nausea and can’t reliably keep down pills or because it is just easier for you to remember to put a patch on every three days rather than taking a pill two or three times per day.

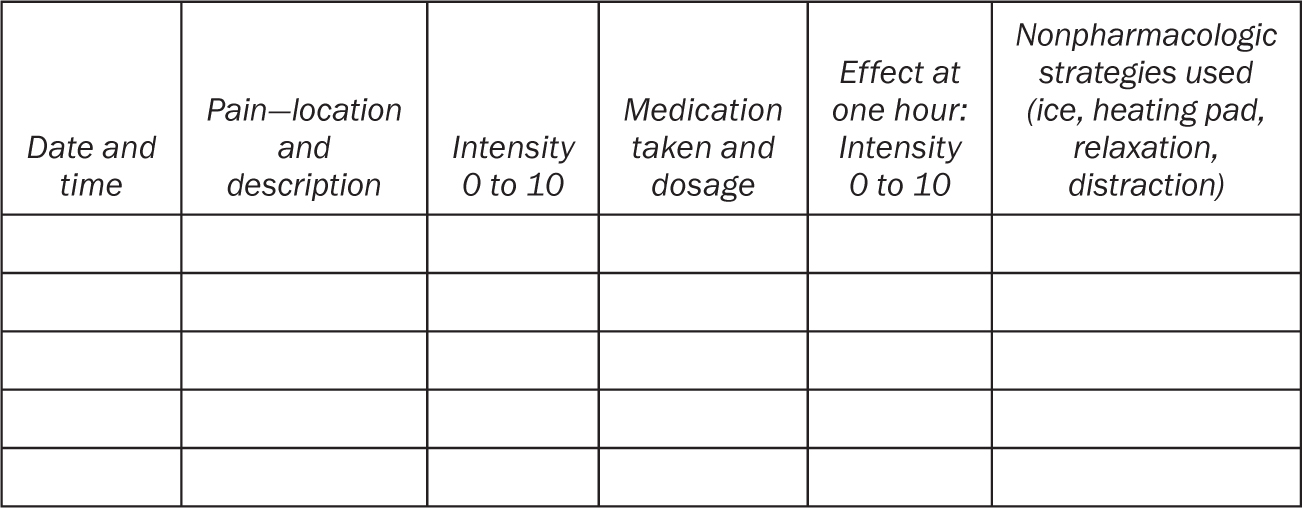

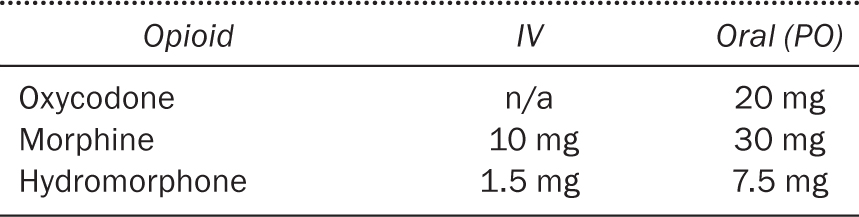

TABLE 11.2 Equivalent IV to oral dosing for opioids

The downside of using a patch is that it can take twelve to twenty-four hours to fully kick in whenever you change the dose. The patch works by seeping into the thin layer of fatty tissue beneath the skin. Patients can struggle to find the right dose if they have lost a great deal of weight during their illness.

Methadone for Pain

Methadone is another long-acting opioid, which you may have heard about as a treatment for heroin addiction. But what you might not know is that it is also an extremely effective, inexpensive, high-potency pain medication sometimes prescribed to treat cancer pain. It may be especially helpful for pain from nerve irritation, the kind that feels like shooting or burning pain.

Methadone is a terrific opioid for severe pain, but it can be very tricky to administer, so you want to make sure that your clinicians have experience prescribing it. Unlike other opioids, methadone takes three to five days to reach peak effect. You and your clinician will need to devise a plan to manage your pain aggressively for those first three days. Your doctor may add steroids to help with the pain for those few days and give you additional short-acting medications. After three days, your doctor can safely increase the methadone.

You never want to overshoot the dose of methadone because it can be unsafe at high levels. I tell patients to be aware of how they feel during those first two days of using methadone. The crazy thing is this: If you feel great on day one or day two, we probably gave you too much. By day three, you could be sleeping all the time if we don’t decrease the dose right away.

Remember to take the methadone exactly as prescribed. Never increase your use of methadone without guidance from your clinical team.

Timing Pain Medications

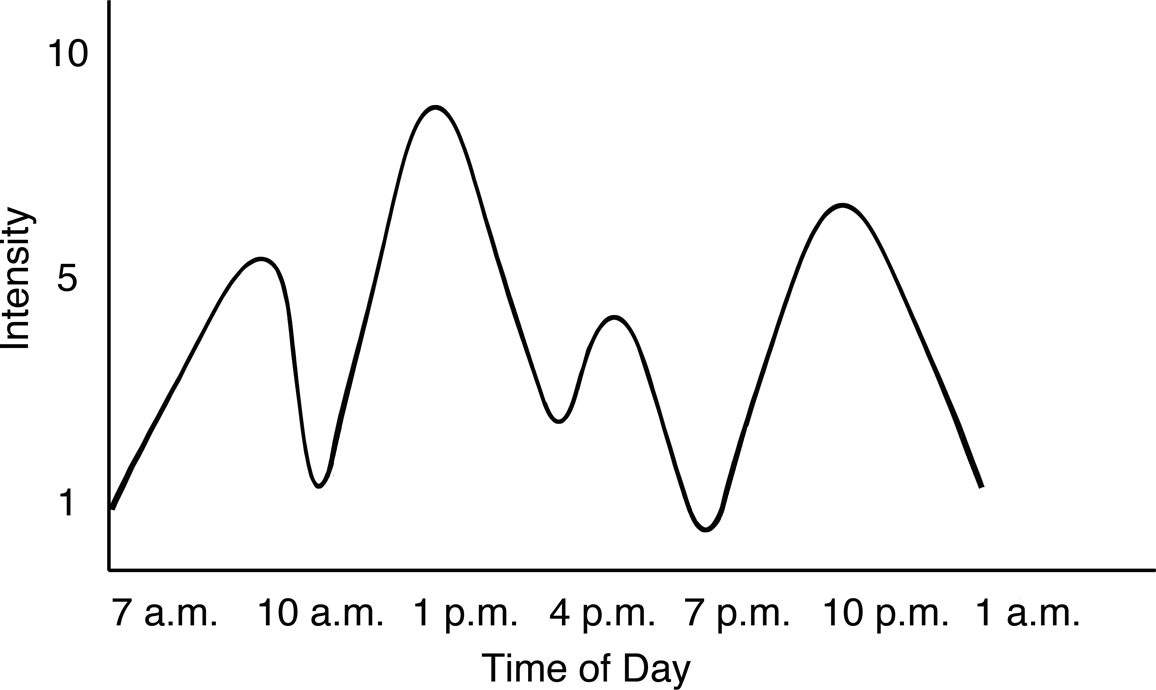

It’s sometimes tricky to figure out how to time pain medications, because people are sometimes tempted to hold off as long as they can before taking anything for relief. When I explain the timing of these medications, I sometimes draw a graph on a piece of paper, like the one in figure 11.2. This illustrates the normal ebb and flow of cancer pain through a typical day. There are often normal variations in pain caused by physical movement or other factors, and these are sometimes predictable.

Figure 11.2 Pain without narcotics

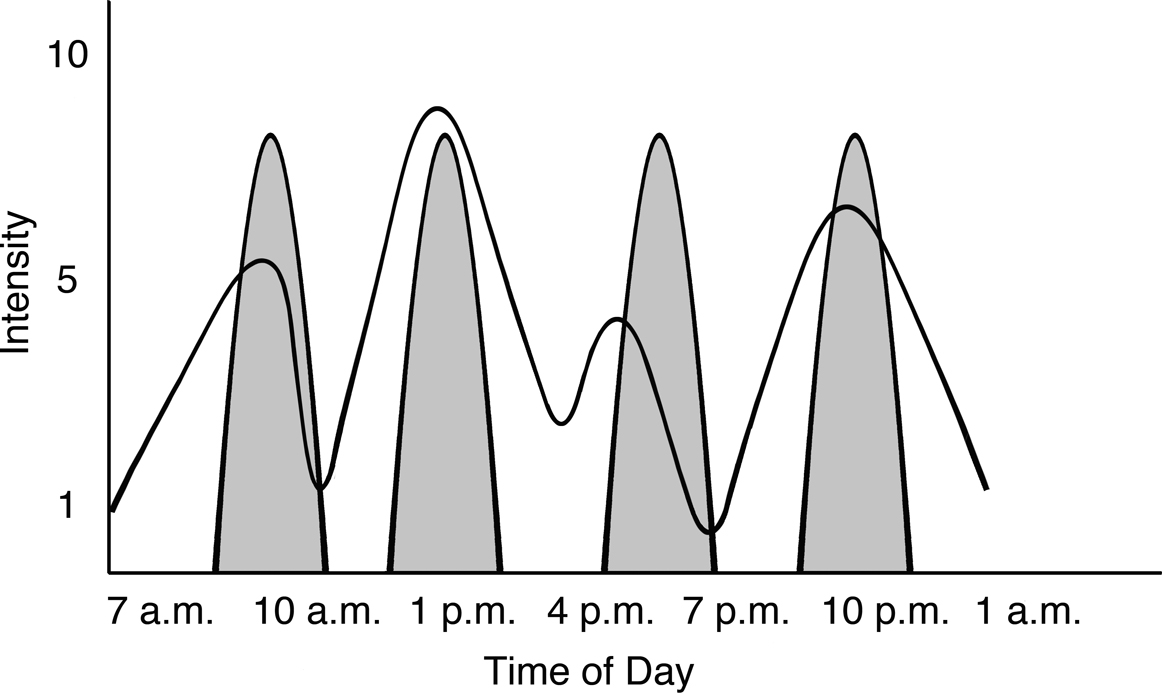

Figure 11.3 Pain with short-acting narcotics; shaded areas indicate pain relief

Figure 11.3 shows with shading how the pain medication starts and builds slowly to full effect and then wears off. You can see how the pain medication taken was more than was needed in two out of the four spikes. When you wait to take medication, sometimes the short-acting medication is reaching peak effect when the pain is less severe. We refer to this as “overshooting the pain” and in that case people experience drowsiness (sedation). It’s important to remember that short-acting medications last just three to four hours, so patients can experience erratic pain control.

Long-Acting plus Short-Acting Medication

Patients with chronic cancer pain will always need both a long- and a short-acting opioid. The long-acting opioid treats the baseline pain and provides a constant level of pain relief. It is much more effective because it doesn’t cause the peaks and valleys that you get with short-acting pain meds alone. If you just take short-acting pills in succession, you will have peak times when you feel drowsy, and then, as the pill wears off, you will be in a valley with more intense pain until you take the next dose. A long-acting medication will give you moderate pain control all the time, and then you can take an additional short-acting dose when the pain breaks through. This so-called breakthrough pain can happen two or three times per day. If it happens more often than that, we typically use this as a cue to increase the long-acting medication.

A patient of mine, Steve, was really reluctant to start a long-acting opioid. He would say, “I don’t need that stuff.” He would take the short-acting medication intermittently and as a result alternated between severe pain and sedation. He was too often too miserable to socialize with anyone, and, when he did take pills, he would nod off during conversations. He was sure that starting a long-acting medication would just make that problem worse.

When he finally decided to give it a try, I started him on a low-dose long-acting morphine preparation that he took once in the morning and once in the evening. He felt like a new man. On the scale of 0 to 10, his pain decreased from a 6 to a 3, which was acceptable to him. His sedation was gone, and he had to take a short-acting med only once or twice a day when the pain broke through. I always remind people that in almost every case we can treat pain to bring it down to an acceptable level. Long-acting pain medications can be an important tool in the tool box.

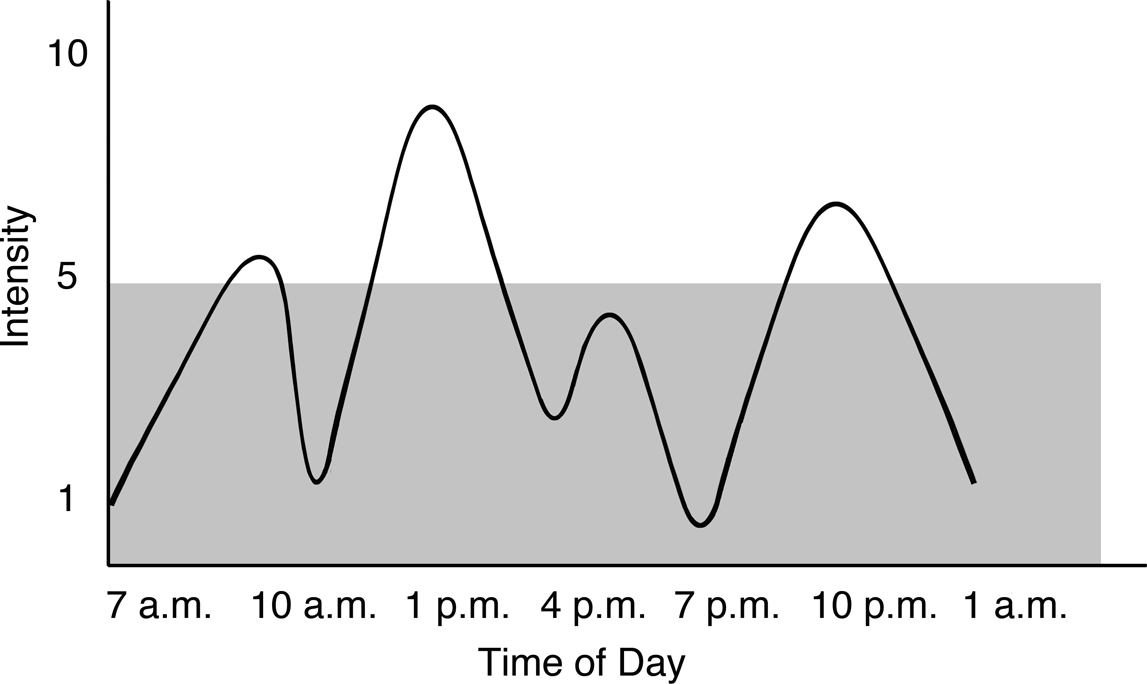

Figure 11.4 Pain with long-acting narcotics; shaded area indicates pain relief

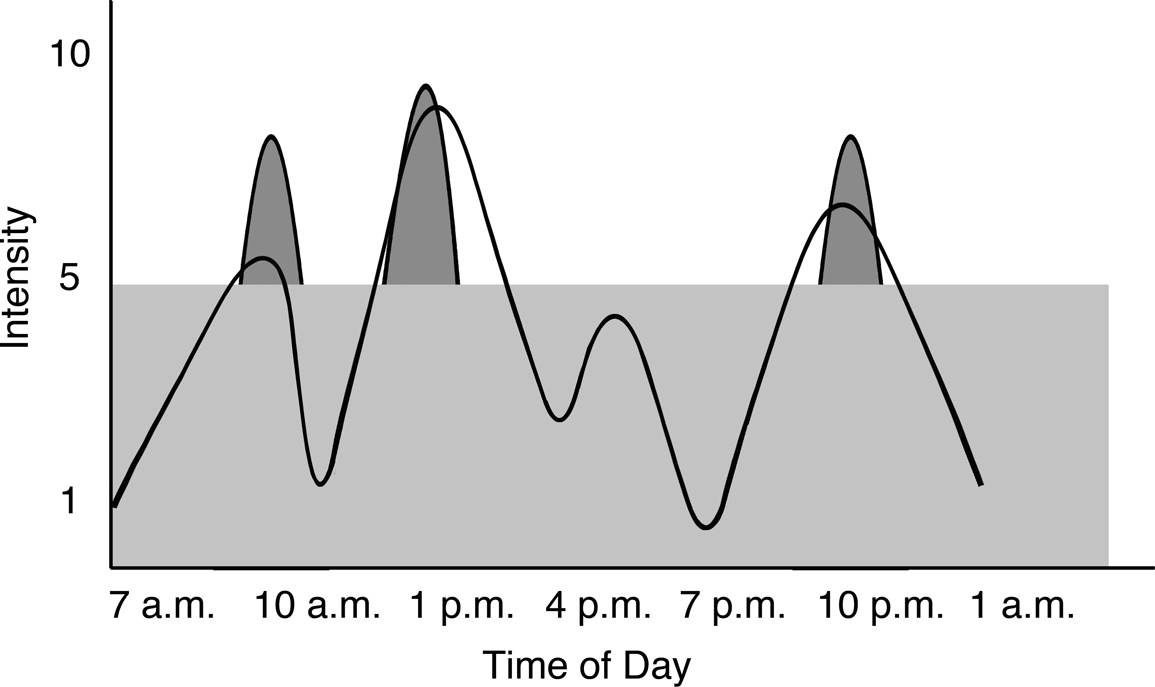

Figure 11.5 Pain with short- and long-acting narcotics; lighter shading indicates pain relief from long-acting medications; darker shading indicates pain relief from short-acting medications

When we start a long-acting opioid, as in figure 11.4, patients experience a much more consistent treatment of their pain. We can still use short-acting opioids for any pain not adequately controlled by the long-acting medication. In general after we start a long-acting opioid, most patients will need the short-acting medication just two to three times per day, as you can see in figure 11.5.

A common mistake that patients make is letting the pain get ahead of them. It’s tempting to think that you can handle the pain and take care of it later. Patients sometimes tell me that they didn’t call the clinic when their pain became disruptive because they didn’t want to bother anyone, or they thought they could wait it out until the next medical visit. The trouble is that your pain can escalate over a couple of days, and then it becomes harder to treat.

I suggest that my patients take the short-acting pain medications every three to four hours as needed to keep the pain at an acceptable level so they can do the activities that matter to them. I also advise them to take the long-acting medications as prescribed. Devise a system so you don’t forget a dose, because your overall pain control will be worse if you skip doses.

Make sure to track your responses to the pain medication you have been given. You may want to do this in writing or bring someone with you to clinic visits who can talk about your response to pain medication and how it’s working. Your medical team wants to know how your pain medications affect you. If the doses make you feel sedated and sleepy when you want to be more active and engaged with your family, your doctor can help you find a better dose for those times of the day. The goal is to have you feeling alert but with good pain control. Sometimes pain can be difficult to manage, and you may need to decide whether you would prefer to have a little more pain but be more alert or have a little less pain and be more sleepy. Sarah, for example, had good pain control for the metastasis in her hip with her oral regimen but experienced sedation. We added a low dose of methylphenidate (a stimulant that is sometimes used to treat ADHD) each morning and at noon, and she was able to have good pain control and still be alert.

Side Effects

Opioids are wonderfully helpful to treat cancer pain, but they can have some side effects that we need to be aware of and manage. These include constipation, nausea, and grogginess. Not everyone experiences all of the side effects. In fact, many of my patients start opioids and don’t experience any except for constipation, which is the most persistent side effect.

Constipation is the main side effect you want to be aware of when starting to take an opioid. See chapter 10 for a discussion of the laxatives doctors usually prescribe alongside opioids.

While you may feel groggy or experience some nausea during the first few days of taking an opioid, these feelings should subside within a few days, or a week at most. In those first few days after starting an opioid, I suggest that patients have a medication available to take if they feel any nausea.

Patients also worry about respiratory depression. Opioids are highly unlikely to cause respiratory depression if they are taken as prescribed. Patients who are taking large doses of other sedating medications such as lorazepam and also patients with renal failure, pulmonary issues, or sleep apnea should discuss appropriate dosing with their clinician. Pain can be effectively and safely treated with opioids. You just need to work with your care team to find what works best for you.

It’s normal to be concerned that you may need multiple medications or treatments to reduce your pain. Many patients have asked me whether they will become an addict because they are taking medications sometimes associated with addiction or abuse. Others fear that the medications won’t make their life normal, or that they will lose effectiveness over time. Let’s take these one by one.

Am I going to become addicted? That’s highly unlikely. In the vast majority of cases, cancer patients take opioids effectively just as they are prescribed. These opioids are powerful medications, but the key to avoiding issues related to addiction is to take the medications only as prescribed and to take pain medications for pain only. If you are having anxiety, we should treat it with a medication for anxiety, not a pain medication. Additionally, pain medications help you engage more fully in life. Good pain control means that you can do what you want to do, unlike people with addiction issues, who use opioids to withdraw from life.

Can I drive while taking narcotics? The short answer is no. You should not drive while taking narcotics. The long answer is that people who are on a stable dose of long-acting narcotics for well-established pain might be able to drive without feeling impaired. But this has never been proven. From a legal standpoint, I tell patients that if you do choose to drive and if you cause an accident or injure someone, you may have no legal defense against the accusation that you were impaired.

Will pain medicine make my life normal? The goal of pain medication is to reduce the discomfort that would prevent you from living as fully as you can. Cancer changes your life, and some activities that you used to do may not be possible, but most patients can do a great deal of what they loved before. The key is to reframe your expectations. A patient of mine loves to row crew. He loves to be on the water out there with the other rowers. Then he had a surgery that made getting into a scull hard for several weeks. With aggressive pain control, he could get into a coaching boat with his buddies and be on the water, which he loved. He is still looking ahead to the time when he feels better and in that spirit signed up for a rowing camp that will take place three months after his surgery.

What if they stop working? Another worry that patients have is that pain medications will lose their effectiveness over time. It is true that bodies get more efficient at processing these medications over time—which is called tolerance. Your medical team will know how to compensate to find reasonable pain control. All opioids have different potencies (e.g., 20 mg of oxycodone is equivalent to 7.5 mg of oral hydromorphone). If we find that one opioid isn’t working as well as it needs to, you can switch to another. I have had patients who required hundreds of milligrams of opioids per day over the course of several years in order to function. Rest assured your doctor can figure something out. He or she can also refer you to a pain specialist such as a palliative care clinician. We have lots of expertise in managing complex pain syndromes.

Can I just stop taking them? If your pain decreases dramatically, your doctor can reduce the dosage. Do not stop taking opioids abruptly, because you can have rebound pain that is difficult to get under control, and it’s possible to have a pain crisis if you stop taking your pain medication suddenly.

Other Strategies for Serious Pain

If you have a sudden, severe onset of pain, your doctor might consider giving pain medication through an IV infusion. Medication delivered in this way typically reaches peak effect in fifteen minutes. You will probably have to be in a hospital setting to receive IV pain medication, but this allows your clinician to quickly figure out how much medication you need and then convert this dosage to an oral regimen you can use at home.

Some patients who need more constant access to IV pain medication can use a PCA, or patient-controlled analgesia pump, that is attached to an IV line. This allows patients to give themselves pain relief as needed. You can just press a button, and the machine will give you a dose of pain medication. Your doctor might suggest this if you are having trouble with oral medications or if your stomach is having trouble absorbing the medication.

These PCA pumps can be portable enough for patients to take them home, if that’s necessary. Patients will need to have a longer-term IV, called a PICC line or a portacath, that the medication infuses into, and they will have a small pump for the pain medication to carry with them at all times. It usually fits into a fanny pack.

There are other interventions for pain beyond medication. For some patients, a nerve block can help improve pain control and limit the amount of opioids they need to take. Other patients may benefit from a form of opioid delivery called an intrathecal pump. It delivers pain medication directly to the spinal cord, allowing doctors to prescribe a much lower dose. It does require a trial of the approach to make sure it will work for a particular kind of pain and then a small surgery to implant the pump into the abdomen. It is a great option for certain patients.

Treatments for Localized Pain

When doctors ask patients to describe the pain associated with cancer, they will always ask about location. Is the pain in a defined area, or does it seem to be located inside a bone? Sometimes tumors cause serious pain in a small, well-defined area. If so, your medical team may look to treat that area rather than giving narcotics alone.

Palliative radiation. While radiation is usually given to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors, it has the side benefit of reducing the pain caused by these tumors. And this can be particularly effective if the cancer has metastasized inside a bone. Rather than using radiation to completely remove the tumor, which may not be possible, the treatments can contain it and dramatically reduce the pain it causes. If your doctor thinks you have a metastasis developing in the backbone, he or she will likely suggest radiation as a means of preventing the tumor from reaching the spinal cord. However, if the pain is occurring in multiple sites, radiation may not be the best course of treatment to control it.

Nerve blocks. Another strategy to deal with pain not well controlled by medication is something called a nerve block. An anesthesiologist or pain specialist can inject a substance into or around a nerve to numb it and prevent it from sending pain sensations to the brain. This helps control pain contained in one specific area of the body, and it is often used for people with pancreatic cancer or other cancers in specific organs.

Some people come to the clinic and tell me that they have pain that’s exactly like the sciatica they remember experiencing earlier in life. A sharp, shooting pain originating in the lower back and descending down one leg. I have to tell them that this is exactly what they are experiencing. Instead of a disc fragment pressing on the nerve, it’s a small tumor. In these cases, a nerve block can be quite effective in controlling the pain.