Setting the Goals of Treatment

IF YOU HAVE A PRELIMINARY DIAGNOSIS of cancer and are still waiting for your first appointment with a medical oncologist, you may be wondering what that appointment is going to be like and how much information you are going to get. On the other hand, if you have already met with a medical oncologist, you may be wondering what happened, how to interpret all that you were told, and how to ask all the questions you still have. Patients sometimes complain that their first meeting with an oncologist is more rushed and businesslike than they were hoping. I can tell you that, from the oncologist’s perspective, an initial appointment with a new patient is as tense as any first date. The stakes are very high, and it’s really easy for doctor and patient to misread each other, to get off to an awkward start.

As a new patient, you also bring a lot of intense emotions to this appointment: hope, dismay, sadness, even anger. That’s normal. And your oncologist is also anxiously trying to figure out what’s going on based on your medical history and test results, and he or she is concerned about how to come up with the most successful treatment plan.

Sometimes patients think that they should concentrate on making sure the doctor knows them and their personal histories, so that the doctor will see them as a person rather than a patient. I love that idea, but like all oncologists I know that I’m going to get to know my patients well during the course of treatment. People choose to specialize in medical oncology because they like spending time with patients and because they want to help people who are dealing with a difficult diagnosis. So, in that first appointment, I’m trying to answer critical questions to get an accurate diagnostic picture and to make the right treatment plan for the patient.

There is a lot of ground to cover in this initial one-hour meeting. You will be asked many questions that may seem repetitive. At the same time, your oncologist is wondering about a number of issues while asking you all these questions and getting a medical history:

The first visit may seem like a whirlwind, but that’s because the oncologist is trying to gather enough information to answer these questions and then explain those answers to you. Remember that this is just the first visit. This is a lot of new and unsettling information to take in, and processing this information is an intensely personal experience. As an oncologist, I know that while some people feel comfortable showing their emotions at such a time, others shut down or go quiet in order to protect themselves.

I know that some people are overwhelmed or angry or tuned out at some points during this first meeting as they try to take it all in. All of these reactions are common and normal. In fact, some people have very mixed feelings about their oncologist after the first appointment.

For example, I remember my first meeting with Phil, a sixty-five-year-old small business owner with a preliminary diagnosis of stage 4 colon cancer. I entered the exam room to find eight people there, including Phil and his wife, their three children, and their children’s spouses. Phil runs a business in which he takes people on day-long fishing trips. The family had closed the business for the day to attend this appointment. That’s how important it was to them. I took his medical history, went over the tests and scans, confirmed the diagnosis of stage 4 colon cancer, and offered a treatment plan.

While the group had started out jovial and joking, they became silent as I talked about the diagnosis. I didn’t know that they had come to this appointment desperately wanting this diagnosis to be a mistake and counting on me to say as much. When I finished talking about treatment options, no one said a word. Phil didn’t ask a single question. He stood, shook my hand, and they all left. I knew something had gone terribly wrong, but I didn’t know what it was, and I didn’t know whether I’d ever see Phil again. Fortunately, there are many great colon cancer specialists in Boston, and I knew he’d be in good hands if he went to someone else. I also knew that he was going to get the same diagnosis and the same treatment options from the next doctor he chose. For some people, it’s easier to hear the diagnosis for the second time.

What surprised me was that Phil did come back for another appointment. He told me that his kids begged him to see someone else, someone who was more hopeful. But Phil told them that he liked me because I was straight with him. He has responded well to chemo and to surgery, and during the past several years I’ve gotten to know him and his family really well. Our appointments are completely different from that first encounter, always a lot of joking and laughing, and he still teases me about the fact that I was almost fired after that first one. For me, it’s a great example of how awkward first meetings can be and how readily that tension fades once treatment begins.

The First Meeting with Your Oncologist

A lot is going to happen in your first meeting with an oncologist, and I think you’ll have a better chance of staying oriented if you know what questions the doctor is likely to ask you before talking about your diagnosis, your pathology report, and the recommended treatment. The first half of every initial appointment is really a chance for the oncologist to gather significant information about your medical history. Yes, it can seem boring and repetitive, and, yes, you’ve already filled out lots of forms. Just keep breathing, and get through this first part, knowing that you will have more time to ask questions in the second half of the appointment.

Chief complaint. This is a fancy term for “what brings you here?” Sometimes doctors will send patients to an oncologist without fully explaining to them that they have cancer. It’s critical for me to know why you think you’re in my office. The oncologist will also ask for what’s called a “history of present illness,” which is a list of what symptoms you’ve experienced in the past few weeks and whether you’ve undergone any tests to reach a diagnosis.

Medications. Your doctor will want to know your current medications and doses, and if you have a list of them, it’s good to bring it to the appointment. Your doctor will also ask whether you have any allergies to medications.

Medical history. You have probably filled out numerous forms detailing a lot of this, but the doctor will want to review them briefly as a way of keeping these details in mind as you go forward. This may be the point where you are thinking, “Can’t we just get on with it? I want to know what the tests say.” Believe me, the doctor knows how impatient you are.

Review of symptoms. The doctor will want to know how you are functioning in daily life. Are you sleeping? Are you in any pain? You may have to answer questions about your anxiety level, your bowels, your eating habits. Are there any activities that you can’t engage in because of symptoms? Your doctor may want to help you relieve certain symptoms right away, even before your cancer treatment starts.

Physical exam. This is an opportunity for the doctor to look for any signs of the tumor in your body. Usually, this is brief, and often it’s just a formality if we already know what we are going to find from the scans that you have had done. But your doctor wants to get every piece of information available.

Labs and scans. The doctor may review with you which blood tests and scans you’ve had done to make sure he or she has copies of all the information. I like to show people the scans if possible because it demystifies the cancer. The blobs and smears on the screen may not look like much to you, but they give a lot of information about the size of the tumors and how much the cancer has spread.

All of this should take place in the first half of your appointment. Don’t be alarmed if the doctor seems to want to take in all of this information at a brisk pace. That’s actually a good sign. Technically, this is a review of available information, but it’s a necessary review. Some patients want to interrupt this process and chat, or they want to try to skip this part and get directly to the diagnosis and treatment plan. Your best strategy is to let the doctor ask all of these initial questions, answer them succinctly, and then be ready to take notes and ask a lot of questions when the doctor gets to the next part: going over the pathology report on your biopsy, giving you what doctors call the clinical picture. This is when your doctor discusses his or her impression—or diagnosis—and then recommends what kind of treatment would be best.

Whenever one of my friends or family members goes to see an oncologist, I always tell them to spend the most time talking to the doctor about the pathology report and the stage of cancer. I know how hard that can be in the moment. Some people feel that the news is like a physical blow. Other people feel as though they are floating outside themselves, or they feel perfectly calm only to discover after the fact that they have only hazy memories about the entire medical visit. Almost every week, I get a phone call from a friend of a friend asking me for advice about a first appointment with an oncologist. It’s hard to give advice when the person on the other end of the phone can’t remember anything about the stage of cancer or the test results. Then it becomes a guessing game. Did the doctor talk about lymph nodes? How about metastases? Did the doctor talk about the size of the tumor or the margins? I sometimes ask these people to read the pathology report to me over the phone, because it contains details about the cancer cells, tumor size, and how far the cancer is spread, and this information will be the foundation for what the oncologist suggests as treatment options. You can and should get a copy of the pathology report at this first meeting.

That’s why I also tell people to bring a notebook or a recording device to this first meeting. It’s great to have another person in the room, so you can double the chances that you walk away knowing the staging and the pathology report. These are the crucial pieces of information to listen to, to ask questions about, and to remember later. When your doctor communicates with other specialists about you, he or she will likely refer primarily to these two things.

So, first, let’s look at what’s likely to be in your pathology report.

The Pathology Report

When tissue has been taken from someone’s body because a doctor suspects cancer, a pathologist takes that tissue and examines it under a microscope. The tissue can come from a biopsy, which is a sample of cells taken from a suspected tumor, or it can come from a surgeon who has removed all or part of the tumor. If your doctor suspects a liquid tumor (discussed in chapter 4), such as leukemia or lymphoma, your biopsy may have been taken from your blood or bone marrow. After examining the tissue sample or the entire tumor, the pathologist will fill out a report with the following information: diagnosis, tumor size and grade, margins, immunohistochemistry, and molecular pathology and genotyping.

Diagnosis. The pathologist will categorize the type of cancer cell found in the tumor or sample. Types include:

Sometimes, the pathologist can state definitively what type of cell is in the sample, which helps doctors figure out the organ in which the cancer started, if it’s a solid tumor. This diagnosis is the cornerstone of everything that will happen in treatment, so be sure to ask your oncologist whether this diagnosis is straightforward and definitive. If it’s not, you may want to ask for a second opinion from another pathologist.

Tumor size. If an entire tumor was removed, the pathologist will measure it from several angles and record the largest measurement as the tumor size. Sometimes the size of the tumor matters, and, as you might imagine, the smaller the tumor, the better. But you should ask your oncologist whether the size of the tumor matters in your case. Tumor size often isn’t relevant if you have leukemia or lymphoma or some cancers in the gastrointestinal system.

Tumor grade. This tells us how aggressive the cancer looks under the microscope. In some cancers, this is not relevant, but in other cancers, such as lymphomas, it is a critical piece of information.

Margins. Again, if an entire tumor has been removed, the surgeon will also have removed some of the normal tissue surrounding the tumor, so that it can be examined for the presence of cancer cells. The result of this examination is crucial. I often give patients the example of a jellyfish. You can see the red center of the jellyfish but you always give it a wide berth because you know it has tentacles that you can’t see. A negative margin or a clear margin indicates that the surgeon removed the visible tumor as well as those tentacles of tumor that were not visible. That’s what the surgeon means (or hopes) when he or she says, “We got it all.”

A positive margin can mean that there was more cancer in the area than the surgeon could see. It also means that the cancer is much more invasive and therefore less likely to be curable. Usually, you don’t need a second opinion on tumor margins because the original pathologist is the only person who knows how the tumor was laid out and how much tissue the surgeon took out. A close margin usually means that the tumor came within millimeters of where the surgeon cut. Close margins are usually associated with a higher risk of the cancer coming back locally. The status of the margin is another factor that won’t matter if you have a liquid tumor, such as leukemia or lymphoma.

Immunohistochemistry. Pathologists can stain tissues with substances that reveal more characteristics about the cancer cells. This process can detect certain cell markers that can give more information about the likely prognosis and give clues about how the cells may respond to treatment. The relevant question to ask is whether the immunohistochemistry is consistent with the diagnosis. If it’s not, ask why not. This is where a second opinion on the pathology might be appropriate.

Molecular pathology and genotyping. The genetics of the tumor are becoming a more significant part of the pathology report. However, we have to wait several weeks or even months for the full genotyping to be done. In this report, pathologists determine which mutations and gene alterations occurred in your tumor. This is not the same as inheriting a predisposition to cancer. This part of the report usually describes how the DNA of your tumor has changed from the DNA of normal tissue to become a cancer.

Here’s a quick primer on DNA, which stands for deoxyribonucleic acid. It is the building block of our entire body. DNA gets translated in the cell into RNA (ribonucleic acid). RNA in turn gets translated into proteins. Proteins are the building blocks of the cell or the pistons in the engine. All you really need to know is that it’s the overexpression of some proteins and the underexpression of other proteins that leads to a cancer.

Sometimes, this information can lead to significant treatment changes. It is extremely important that you ask your oncologist whether molecular pathology or genotyping is significant in your type of cancer.

Tests and Scans That Help with Staging

The second most important thing to pay attention to in this meeting is the stage of your cancer. If your doctor is able to stage your cancer in this first meeting, that’s probably because you’ve had one or more scans that allow doctors to look at the rough outlines of the tumor and study its exact location. Your doctor may have ordered additional scans of your whole body or other parts of your body to search for metastases, or small tumors that may be visible in other areas of the body. This information, combined with notes from the surgeon and the pathology report of the biopsy or tumor will provide the information needed to set the stage of your cancer.

You should get information about staging at your first appointment with your medical oncologist, unless more testing needs to be done. (We talk more fully about tests and scans in chapter 6.) At a major teaching hospital, there is a whole system in place for staging cancer, so at the first suspicion of cancer, the patient will meet with an interventional radiologist or surgeon who will order scans and then do a biopsy for the pathologist. These are the details doctors need to give you staging information. At smaller community hospitals, the medical oncologist is often responsible for ordering those tests and then making the diagnosis.

What Is the Stage of My Cancer?

You may already know that all cancers have four stages—except for some hematologic malignancies and brain tumors, which are staged differently (hematologic malignancies, or cancers of the blood, are discussed in chapter 4). For every other type of cancer, we talk about stages in terms of the numbers 1 through 4. This is an internationally recognized staging process for all cancer established by the World Health Organization.

Am I Curable?

You do want to ask this question after your doctor has staged your cancer, but I will warn you that the doctor might not have a definitive answer. Usually when doctors talk about being cured, we mean that after treatment the cancer is gone and doesn’t come back even after five years. But this isn’t always the case, because some cancers do return. You can follow up by asking what the chances are that you might be cured. This is where you want to ask a lot of questions about the type of treatment the oncologist is suggesting and how likely you are to be cured if you agree to all of these treatments.

Sometimes it’s clear that a cancer should be curable. For example, a relatively small tumor that has not spread to the lymph nodes or any other areas usually has a good chance of being cured. I remember one patient who came to me about ten years ago with a diagnosis of stomach cancer. She was relatively young, but her mother had died of stomach cancer at a similar age, so this patient assumed that she would also die. In fact, she was already getting her affairs in order, and her main treatment questions were about managing pain. I had to say to her, “No, I think we can cure this.” She didn’t quite believe me at first, but her cancer was curable. I still hear from her sometimes.

However, if the cancer has spread into the liver and other organs, it’s likely not curable. But in some cases there’s a possibility of cure with aggressive treatment, and in that case you want to ask how aggressive the treatment has to be to give you that chance.

The Goal of Treatment

The first question you want to ask after staging is what the oncologist hopes treatment will do for you. By knowing the goal of treatment, you can better choose treatment options that are right for you. We can talk about the goal of treatment only when we know the pathology and the staging. I’ve had patients blurt out in the first several seconds that they are never going to do chemotherapy, before they even know the diagnosis, stage, and treatment options. Or I’ve had patients say that they will do everything to fight the cancer and try to beat it. People and the media always talk about fighting cancer, but oncologists don’t think in these terms. We think in terms of the goals of treatment. There are just three possible goals in treatment:

Nothing should be prescribed for you unless it fits one of these stated goals: to try to cure the cancer, to prolong life, or to make you feel better. And this is a good time to ask your doctor what the goals of treatment are. What does your doctor think is possible for you? You also want to be thinking about your goals and values. How much treatment do you want? How aggressive can those treatments be while allowing you to maintain your quality of life?

Your Goals and Values

Sometimes the goal of therapy changes when people find out what it will take to have a chance at a cure. I’m treating an author who lives in the Berkshires and has metastatic colon cancer. We talked about how surgery alone would be unlikely to cure her cancer and that if she had additional chemotherapy and radiation, her likelihood of a cure would go up by about 10 percent. It was going to be a tough treatment regimen, one that would likely have disrupted her work life, making it impossible to finish her novel. She told me that she was perfectly comfortable with surgery alone because finishing her novel meant more to her than gaining a better chance of surviving the cancer. So her goal changed. Instead of pursuing the chance of a cure at all costs, she decided to forego chemotherapy because she believed that the treatment wasn’t worth the better odds it offered for a cure.

If the doctor tells you that your cancer isn’t curable, you still have choices about what treatments to use to control the cancer. Surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation treatments are all disruptive, and you will need to think about what you want to endure to prolong your life. Some people view living as long as they possibly can as the ultimate goal, while others prefer to emphasize living as well as they can. For example, one of my patients has a slow-growing gastrointestinal stromal tumor, and the recommended treatment includes imatinib to help slow the tumor’s growth. Even though this medication is working as it should and keeping the tumor growth down, it has side effects that that patient hates. As a result, she insists upon taking treatment breaks that may shorten her life. She has decided that gaining extra time, even if it’s a year or two, isn’t worth the side effects of continuous treatment.

Even if the goal of treatment is to make you comfortable, you have choices about which treatments you do and don’t want. You can opt for some disease-modifying treatments to pursue that goal. For instance, I had a patient who told me that she didn’t want to do anything except see Vicki in palliative care to manage the symptoms and side effects of her cancer, because she didn’t want any more chemotherapy. She later developed a small metastasis in her rib right underneath her armpit. Every time she rolled over in her sleep a sharp jab of pain would wake her up. She experimented with all types of pain and sleeping medicines, but nothing worked. I finally convinced her to let us radiate the rib metastasis. After three short treatments the next week, she started to notice improvement. She was sleeping through the night without any pain two weeks after the radiation finished.

Knowing the goal of treatment as well as your values empowers you throughout treatment. It gives you the ability to choose treatments that help you achieve your goal and to refuse treatments that you don’t want. Early on, you may want to pursue every treatment to have a chance at curing a cancer or to prolong your life. Over time, that goal may change, and that’s okay.

The Treatment Plan

Once your doctor tells you what your type of cancer is and the stage, he or she may talk about a plan for treatment. Just as there are only three goals of cancer treatment (cure, live longer, feel better), there are only three broad options to treat a cancer:

That’s it. I always give people treatment options in all three categories, but I also initiate a conversation about the patient’s goals and values and then make a recommendation for treatment based on that. Some oncologists offer a lot of treatment options as though it’s an à la carte menu and then ask you to choose the best option. And while I agree that the patient ultimately decides on the treatment option, I disagree with the à la carte menu approach. Patients should make treatment decisions in line with their values. You have the right to choose whether you want to undergo a specific type of treatment. I’ve had patients who have come out of surgery with clear margins and good prognosis to whom I have recommended chemotherapy because it improves their chance of being cured and because that’s what I would have chosen for myself. And in some cases patients have said, “No, thanks.” Some patients know exactly what they want and don’t want, and I respect that.

But I also know that some people struggle with the burden of choosing treatment. The last thing I want patients to feel is that they are all alone in making this decision.

For example, seventy-eight-year-old Margaret is a retired lawyer who has stage 3 colon cancer. She has three options. We can pursue supportive care alone in which we will help her recover from her surgery and follow her closely for recurrence. She has a 75 percent chance of being cured without any chemotherapy. She could choose to pursue standard chemotherapy for six months, which will improve her chances of being cured to 80 percent. And finally, we have an experimental clinical trial for patients with stage 3 colon cancer in which we add a drug to the standard regimen. We don’t know that the drug in this clinical trial is any better or worse than standard chemotherapy. It could be better than standard treatment. In fact, it could become the new standard of treatment in five years. But we don’t know that.

Margaret’s number one fear is that she won’t be around to take care of her husband, who has just been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. She would feel awful if she didn’t do everything possible to be around for him. But she needs to have all her strength to help him now, and she believes the clinical trial with its extra visits and extra chances of side effects is not the right choice. So we make a decision together to give her six months of chemotherapy to give her the best chance possible to be cured.

Can I Die from Treatment?

The final question you want to ask is a tough one. Ask whether there is a chance that certain side effects are permanent or whether there is a chance that you could die from a side effect of treatment. For many standard chemotherapy treatments, there is a 0.5 to 1 percent chance of dying from the treatment. While it’s not high, it’s not as low as for other medications. This is a meaningful discussion to have with your oncologist, particularly if you have other chronic health issues. Nobody likes to think about the possibility of dying from treatment, but some treatments do come with a higher risk of death, and you want to have this information before you begin.

For example, I had a patient who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Charlie was seventy-nine years old at the time of diagnosis, and he was also coping with diabetes, mild kidney dysfunction, and heart failure. I explained to Charlie that he could have the tumor removed with surgery and then undergo chemotherapy for a chance at a cure, but that the treatments came with a lot of risk. Charlie’s wife asked the critical question, which was how likely was he to die if he had the surgery, given his other medical issues. The answer was that he had a 10 to 20 percent chance of dying in surgery. Although Charlie was optimistic about his chances, he and his wife agreed to think about this more and talk to their children before deciding on a course of treatment.

Oncologic Emergencies

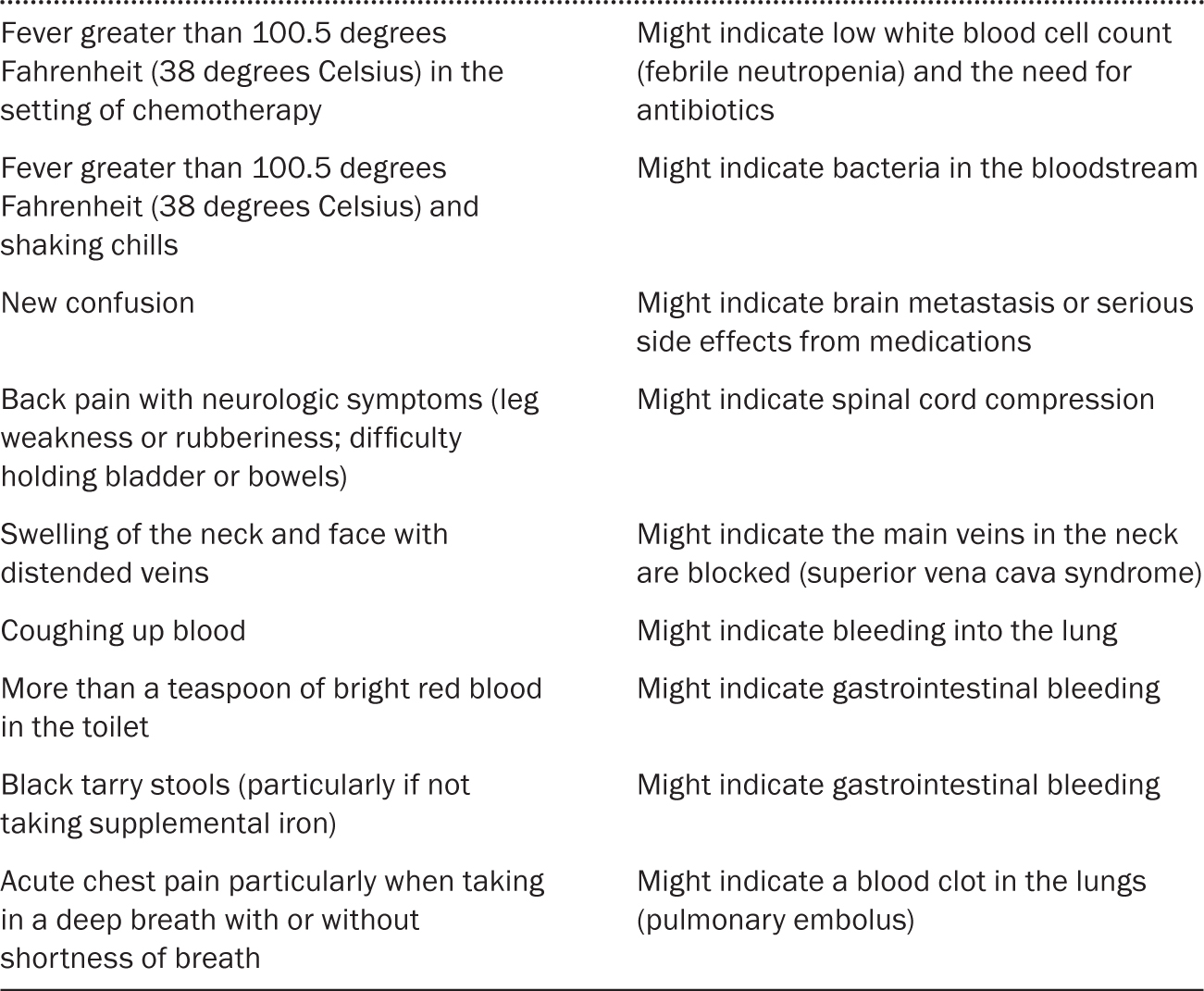

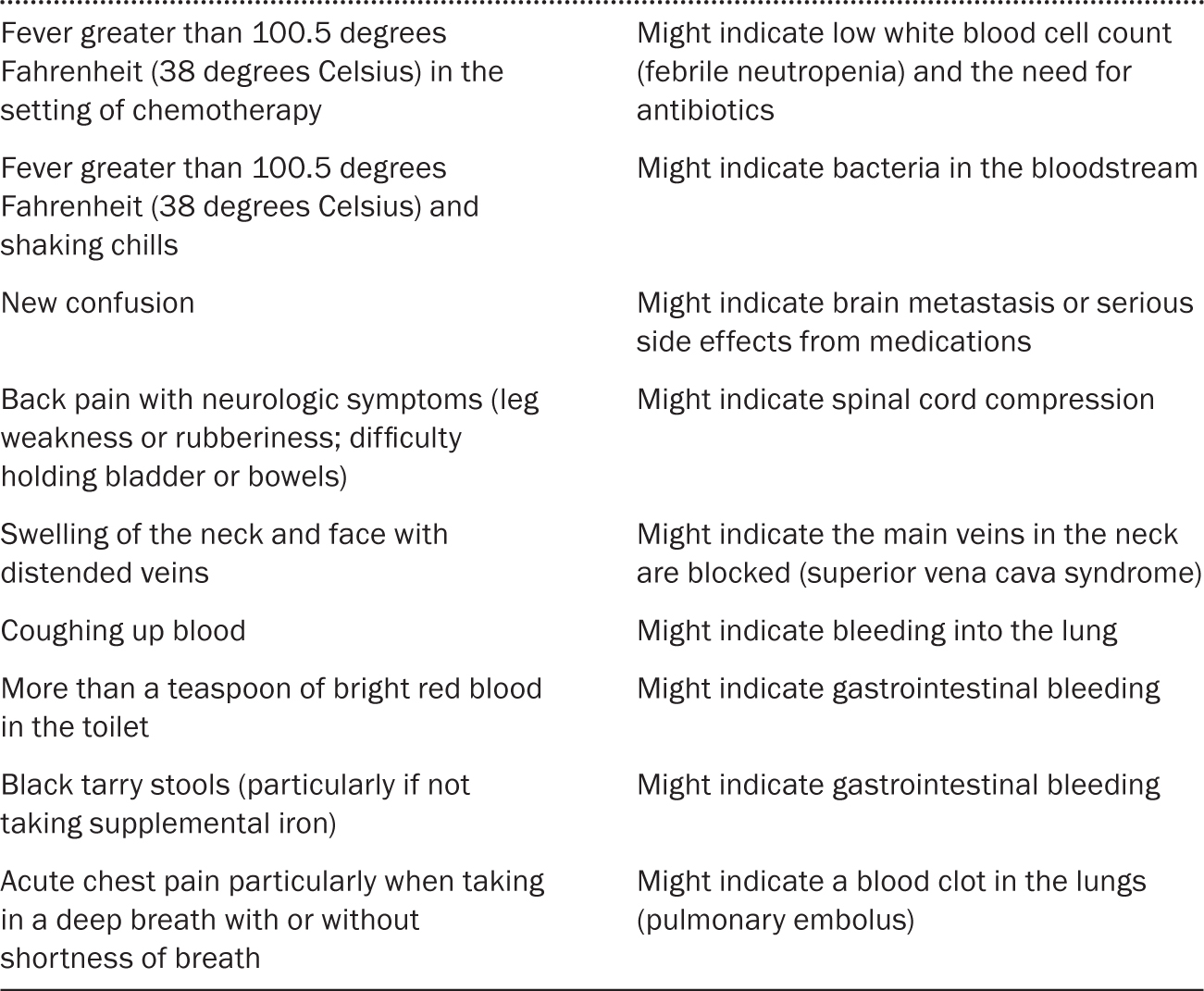

Even at this early stage of diagnosis for cancer, emergencies can occur. At any time in your treatment, if you experience the following symptoms, call your doctor or the clinic immediately, regardless of the time. In the following instances (table 2.1), you want a call back from a clinician within ten to fifteen minutes. If you don’t hear back from a clinician and are feeling unwell, you should go to the emergency room.

TABLE 2.1 Oncological emergencies

Often I hear from friends who live in another part of the country and who are dealing with a cancer diagnosis for themselves or a loved one. And they want to know how to find the best oncologist, or they want to fire the oncologist they have and find a new one. I tell them to look for someone who has treated a lot of people with your type of cancer. Some people want a doctor who is prominent in the field, but that’s not as important as finding someone who is a good communicator.

One of my colleagues uses what he calls the 3 A’s for judging a doctor: able, available, and affable. By that, he means that your oncologist’s first responsibility is to be competent in his or her specialty. Second, a great doctor is available to patients. You want to have a phone number that you can call at any time and know that the doctor or nurse practitioner will get back to you quickly. The third marker for greatness in a doctor—affability—is harder to come by among oncologists. A few oncologists are charming, but many great oncologists tend to be more serious or a bit shy. So affability for an oncologist may mean finding someone who can explain technical issues and options and who is emotionally supportive.

You want to work with a doctor who invites questions and answers them, someone who sees you as a person, someone you can call at any time, someone you trust. When you are getting references, be sure to ask about the doctor’s communication style. When you meet with a new doctor, be sure to ask, “How can I reach you if I need something?” You also want to work with someone who is part of a well-staffed team, so that there are nurse practitioners, nurses, social workers, and other team members who can talk to you any time and see you right away when you need advice and help.