The Manhattan Psychiatric Institute is located on Amsterdam Avenue at 112th Street in New York City. It is a private teaching and research hospital affiliated with the nearby Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. MPI is distinct from the Psychiatric Institute at Columbia, which is a general treatment center that deals with far more patients. We refer to it as “the big institute,” and ours, in turn, is known as “the little institute.” Our concept is unique: We take in only a limited number of adult patients (one hundred to one hundred twenty in all), either cases of unusual interest or those that have proven unresponsive to standard somatic (drug), electroconvulsive, surgical, or psychotherapies.

MPI was constructed in 1907 at a cost of just over a million dollars. Today the physical facility alone is worth one hundred fifty million. The grounds, though small, are well kept, with a grassy lawn to the side and back, and shrubs and flower gardens along the walls and fences. There is also a fountain, “Adonis in the Garden of Eden,” situated in the center of what we call “the back forty.” I love to stroll these pastoral grounds, listen to the bubbly fountain, contemplate the old stone walls. Entire adult lives have been lived here, both patient and staff. To some, this is the only world they will ever know.

There are five floors at MPI, numbered essentially in order of increasing severity of patient illness. Ward One (ground floor) is for those who suffer only acute neuroses or mild paranoia, and those who have responded to therapy and are nearly ready to be discharged. The other patients know this and often try very hard to be “promoted” to Ward One. Ward Two is occupied by those more severely afflicted: delusionals such as Russell and prot, manic and deep depressives, obdurate misanthropes, and others unable to function in society. Ward Three is divided into 3A, which houses a variety of seriously psychotic individuals, and 3B, the autistic/catatonic section. Finally, Ward Four is reserved for psychopathic patients who might cause harm to the staff and their fellow inmates. This includes certain autists who regularly erupt into uncontrollable rages, as well as otherwise normal individuals who sometimes become violent without warning. The fourth floor also houses the clinic and laboratory, a small research library, and a surgical theater.

Wards One and Two are not restricted in most cases, and the patients are free to mingle. In practice, this takes place primarily in the exercise/recreation and dining rooms (Wards Three and Four maintain separate facilities). Within each ward, of course, there are segregated sleeping and bathing areas for men and women. The staff, incidentally, maintains offices and examining rooms on the fifth floor; it is a common joke among the patients that we are the craziest inmates of all. Finally, the kitchens are spread over several floors, the laundry, heating, air-conditioning, and maintenance facilities are located in the basement, and there is an amphitheater on (and between) the first and second floors, for classes and seminars.

Before becoming acting director of the hospital I usually spent an hour or two each week in the wards just talking with my patients, on an informal basis, to get a sense of their rate of progress, if any. Unfortunately, the press of administrative duties put an end to that custom, but I still try to have lunch with them occasionally and hang around until my first interview or committee meeting or afternoon lecture. On the day after the Memorial Day weekend I decided to eat in Ward Three before looking over my notes for my three o’clock class.

Besides the autists and catatonics, this ward is populated by patients with certain disorders which would make it difficult for them to interact with those in Wards One and Two. For example, there are several compulsive eaters, who will devour anything they can get their hands on—rocks, paper, weeds, silverware; a coprophagic whose only desire is to consume his own, and sometimes others’, feces; and a number of patients with severe sexual problems.

One of the latter, dubbed “Whacky” by a comedic student some time ago, is a man who diddles with himself almost constantly. Virtually anything sets him off: arms, legs, beds, bathrooms—you name it.

Whacky is the son of a prominent New York attorney and his ex-wife, a well-known television soap opera actress. As far as we know he enjoyed a fairly normal childhood, i.e., he wasn’t sexually repressed or abused in any way, he owned a Lionel train and Lincoln logs, played baseball and basketball, liked to read, he had friends. In high school he was shy around girls, but in college he became engaged to a beautiful coed. Although convivial and outgoing, she was nevertheless extremely coquettish, leading him on and on but never quite going “all the way.” Crazed with desire, Whacky remained as virginal as Russell for two agonizing years—he was saving himself for the woman he loved.

But on their wedding day she ran off with an old boyfriend, recently released from the state prison, leaving Whacky literally standing at the altar (and bursting at the seams). When he received the news that his fiancée had jilted him, he took down his pants and began to masturbate right there in the church, and he has been at it ever since.

Prostitution therapy was completely ineffective in Whacky’s case. However, drug treatments have proven marginally successful, and he can usually come to the table and get back to his room without causing a disturbance.

When he is not caught up in his compulsion, Whacky is a very pleasant guy. Now in his mid-forties, he is still youthfully handsome, with closely cropped brown hair, a strong cleft chin, and a terrible melancholy that shows in his sad blue eyes. He enjoys watching televised sporting events and talks about the baseball or football standings whenever I see him. On this particular occasion, however, he did not discuss the Mets, his favorite team. Instead, he brought up the subject of prot.

Whacky had never seen my new patient as far as I knew, since inhabitants of Ward Three are not permitted to visit the other floors. But somehow he had heard about a visitor in Ward Two who had come from a faraway place where life was very different from ours, and he wanted to meet him. I tried to discourage the idea by downplaying prot’s imaginary travels, but his pathetic baby-blue eyes were so insistent that I told him I would give the matter some thought. “But why do you want to meet him?” I inquired.

“Why, to see if he will take me back with him, of course!”

The sudden silence was eerie—the place is usually one of noisy confusion and flying food. I glanced around. No one was wailing or giggling or spitting. Everyone was watching us and listening. I mumbled something about “seeing what I could do.” By the time I got up to leave, the whole of Ward Three had made it clear that they wanted a chance to take their cases to my “alien” patient, and it took me nearly half an hour to calm everyone down and make my exit.

Talking with Whacky always reminds me of the awesome power that sex has over all of us, as Freud perceived in a moment of tremendous inspiration a century ago. Indeed, most of us have sexual problems at some time in, if not throughout, our lives.

It wasn’t until my wife and I had been married for several years that it suddenly occurred to me what my father had been doing on the night he died. The realization was so intense that I leaped out of bed and stared at myself in the closet-door mirror. What I saw was my father looking back at me: same tired eyes, same graying temples, same knobby knees. It was then that I understood with crystal clarity that I was a mortal human being.

My wife was wonderfully understanding throughout the ensuing ordeal—she is a psychiatric nurse herself—though she finally insisted I seek professional help for my frustrating impotence. The only thing that came from this was the “revelation” that I harbored tremendous guilt feelings about my father’s death. But it wasn’t until after I finally passed the age he was when he died that the (midlife) crisis mercifully ended and I was able to resume my conjugal duties. During that miserable six-month period I think I hated my father more than ever. Not only had he chosen my career for me and precipitated a lifelong guilt complex, but, thirty years after his death, he had nearly managed to ruin my sex life as well!

Steve did even better than he promised. He faxed the astronomical data, including a computerized printout of a star chart of the night sky as seen from the hypothetical planet K-PAX, directly to my office. Mrs. Trexler was quite amused by the latter, referring to it as my “connect-the-dots.”

Armed with this information, which prot could not possibly have had in his possession, I met with him again at the usual time on Wednesday. Of course I knew he could not be a space traveler any more than our resident Jesus Christ could have stepped out of the New Testament. But I was nonetheless curious as to just what this man could pull from the recesses of his unpredictable, though certainly human, mind.

He came into my examining room preceded by his standard Cheshire-cat grin. I was ready for him with a whole basket of fruit, which he dug into with relish. As he devoured three bananas, two oranges, and an apple he asked me a few questions about Ernie and Howie. Most patients express some curiosity about their fellow inmates and, without divulging anything confidential, I did not hesitate to answer them. When I thought he was relaxed and ready I turned on the recorder and we began.

To summarize, he knew everything about the newly discovered star system. There was some discrepancy in his description of the way K-PAX revolved around the two stars it was associated with—he claimed it was not a figure eight but something simpler—and the corresponding length of the putative planet’s year was not what Steve or, rather, Dr. Flynn had calculated. But the rest of it fit quite well: the size and brightness of Agape and Satori (his K-MON and K-RIL), the periodicity of their rotation about each other, the next closest star, etc. Of course it could have been a series of lucky guesses, or perhaps he was reading my mind, though the tests showed no special aptitude for this ability. It seemed to me more likely, however, that this patient could somehow divine arcane astronomical data much like the savants mentioned earlier can make computer-like calculations and pull huge numbers from their heads. But it would have been an astonishing feat indeed if he could have constructed a picture of the night sky as seen from the planet K-PAX, which, incidentally, Professor Flynn had now chosen to call his previously unnamed planet. In anticipation of this result I think I was already contemplating the book the reader is now holding. So it was with some excitement that I nervously watched as he sketched his chart, insisting all the while that he wasn’t very good at freehand drawing. I cautioned him to remember that the night sky as observed from K-PAX would look quite different from the way it does on Earth.

“Tell me about it,” he replied.

It took him only a few minutes. While he was sketching I mentioned that an astronomer I knew had informed me that light travel was theoretically impossible. He stopped what he was doing and smiled at me tolerantly. “Have you ever studied your EARTH history?” he asked. “Can you think of a single new idea which all the experts in the field did not label ‘impossible’?”

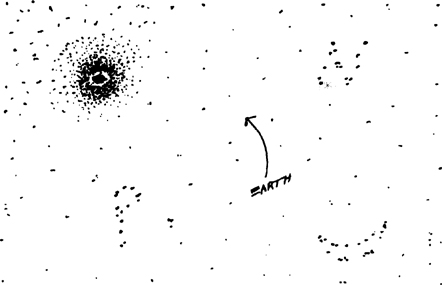

He returned to his diagram. As he drew he seemed to focus on the ceiling, but perhaps his eyes were closed. In any case he paid no attention to the map he was working on. It was as if he were simply copying it from an internal picture or screen. This was the result:

There are several notable features about his sketch: a “constellation” shaped like an N (upper right), another like a question mark (lower left), a “smiling mouth” (lower right), and an enormous eye-shaped cluster of stars (upper left). Note that he also indicated the location of the invisible Earth on his chart (center). The reason for the relatively few background stars in the diagram was, according to prot, that it never got completely dark on K-PAX, so there are fewer stars visible in the sky than one can ordinarily see, in rural areas, from the nighttime Earth.

However, it was clear that prot’s and Steve’s charts were completely different. Although not surprised to find that my “savant” had his limits I was, nonetheless, somewhat disappointed. I am aware that this is not a very scientific attitude, and I can only attribute it to the post-midlife-crisis syndrome first described by E. L. Brown in 1959, something that occurs most often in men who have entered their fifties: a curious desire for something interesting to happen to them.

Be that as it may, at least I would now be able to confront the patient with this contradictory evidence, which would, I hoped, help to convince him of his Earthly origin. But that would have to wait until the next session. Our time was up, and Mrs. Trexler was impatiently flashing me a telephone signal to remind me of a safety committee meeting.

According to my notes the place was a zoo the rest of the afternoon with meetings, a problem with several of the photocopy machines, Mrs. Trexler at the dentist, and a seminar by one of the candidates for the position of permanent director. But I did find time to fax prot’s star map to Steve before escorting the applicant to dinner.

The candidate, whom I shall call Dr. Choate, exhibited a rather peculiar mannerism: He continually checked his fly, presumably to make sure it was closed. Quite unconsciously, it appeared, since he did it in the conference room, in the dining room, in the wards, with women present or not. And his specialty was human sexuality! It has been said that all psychiatrists are a little crazy. Dr. Choate did nothing to dispel that canard.

I took the candidate to Asti, a lower Manhattan restaurant where the proprietor and his waiters are apt to break into an aria at the drop of a fork and encourage their patrons to do likewise. But Choate had no interest in music and finished his meal in rather glum silence. I had a lovely time, however, catching a flying doughball in my teeth and singing the part of Nadir in the lovely duet from The Pearl Fishers, and still made the 9:10 to Connecticut. When I got home, my wife told me Steve had called. I rang him back immediately.

“Pretty amazin’ stuff!” he exclaimed.

“Why?” I said. “His drawing didn’t look a thing like yours.”

“Yes, Ah know. Ah thought your man had just concocted somethin’ out of his head, at first. Then Ah saw where he had put in the arrow indicatin’ the position of the Earth.”

“So?”

“The chart Ah gave you was for the sky as seen from Earth, except that it was transposed seven thousand light-years away to the planet he calls K-PAX. Do you see what Ah’m sayin’? Lookin’ back here from there, the sky would appear entirely different. So I went back to my computer, and voilà! There was the N constellation, the question mark, the smile, the eyeball cluster—all where he said they’d be. This is a joke, idn’ it? Ah know Charlie put you up to this!”

That night I had a dream. I was floating around in space and utterly lost. No matter which direction I turned, the stars looked exactly the same to me. There was no familiar sun, no moon, not even a recognizable constellation. I wanted to go home but I had no idea which way it was. I was afraid, terrified that I was all alone in the universe. Suddenly I saw prot. He was motioning that I should follow him. Greatly relieved, I did so. As we proceeded he pointed out the eyeball cluster and all the rest, and at last I knew where I was.

Then I woke up and couldn’t go back to sleep. I recalled an incident a few days earlier when I was running across the hospital lawn on my way to a consultation with the family of one of my patients. Prot was sitting on the grass clutching, it appeared, a batch of worms. I was late for an appointment and didn’t dwell on it then. Later on I realized that I had never seen any of the patients playing with a handful of worms before, and where did he get them? I puzzled over this as I lay in bed awake, until I remembered his saying, in session two, that on K-PAX everything had evolved from wormlike creatures. Was he studying them as we might scrutinize our own cousins, the fishes, whose gills still manifest themselves for a time in the human embryo?

* * *

I hadn’t yet found an opportunity to call Dr. Rappaport, our ophthalmologist, about the results of the vision test, but I did so the following morning. It is “highly unlikely,” he told me, somewhat testily, I thought, that a human being would be able to detect light at a wavelength of three hundred angstroms. Such a person, he pointed out, would be able to see things only certain insects can see. Though he seemed extremely dubious, as if I were trying to make him the victim of a practical joke, he wouldn’t go so far as to deny our examination results.

Once again I reflected on how remarkably complex the human brain really is. How can a sick mind like prot’s possibly train itself to see UV light, and figure out how to diagram the sky from seven thousand light-years away? The latter was not completely outside the realm of possibility, but what an astonishing talent! Furthermore, if he was a savant, he was an intelligent, amnesiacal, delusional one. This was absolutely extraordinary, an entirely new phenomenon. And I suddenly realized: I’ve got my book!

Savant syndrome is one of the most amazing and least understood pathologies in the realm of psychiatry. The affliction takes many forms. Some savants are “calendar calculators,” meaning that they can tell you immediately what day of the week July 4, 2990 falls on, though they are often unable to learn to tie their shoes. Others can perform incredible arithmetical feats, such as to add long columns of numbers, mentally calculate large square roots, etc. Still others are wonderfully musically gifted and can sing or play back a song, or even the various parts of a symphony or opera, after a single first hearing.

Most savants are autistic. Some have suffered clinically detectable brain damage, while others show no such obvious abnormality. But nearly all have IQs well below average, usually in the fifty to seventy-five range. Rarely has a savant been found to exhibit a normal or greater intelligence quotient.

I am privileged to have known one of these remarkable individuals. She was a woman in her sixties who had been diagnosed with a slow-growing brain tumor centered in the left occipital lobe. Because of this malignancy she was almost totally unable to speak, read, or write. She was further plagued by a nearly constant chorea and barely able to feed herself. As if that weren’t enough, she was one of the most unattractive women I have ever seen. The staff called her, affectionately, “Catherine Deneuve,” after the lovely French film star, who was very popular at that time.

But what an artist! When provided with suitable materials, her head and hands stopped shaking and she began to create, from memory, near-perfect reproductions of works by many of the greatest artists in history. Though they ordinarily took only a few hours to complete, her paintings are virtually indistinguishable from the originals. Amazingly, while she worked she even seemed to become beautiful!

Some of her work now resides in various museums and private collections all over the country. When she died, the family generously donated one of her pictures to the hospital, where it graces the wall of the faculty conference room. It is a perfect copy of van Gogh’s “Sunflowers,” the original of which hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and one is just as awestruck by her talent as by the genius of the master himself.

In the past, the emphasis has been on trying to “normalize” such individuals, to mold them into products more suitable to society’s needs. Even “Catherine Deneuve” was encouraged to spend less time painting and more time learning to dress and feed herself. If not cultivated, however, these remarkable abilities can be lost, and attempts are now being made, at various institutions, to allow such people to develop their gifts to the fullest.

However, most savants are very difficult to communicate with. Normal discourse with “Catherine,” for example, was impossible. But prot was alert, rational, able to function normally. What might we learn from such an individual? What else did he know about the stars, for example? Might there be more ways to arrive at knowledge than we are willing to consider or admit? There is, after all, a fine line between genius and insanity—consider, for example, Blake, Woolf, Schumann, Nijinsky, and, of course, van Gogh. Even Freud was plagued by severe mental problems. The poet John Dryden put it this way:

Great wits are sure to madness near alli’d And thin partitions do their bounds divide.

I brought this up at the Monday morning staff meeting, where I proposed to let prot ramble on about whatever he wanted and try to determine whether there was anything of value he might have to tell us about his (our) world, as well as his own condition and identity. Unfortunately, despite the substantiating presence of “Catherine Deneuve” ‘s priceless painting, there was little enthusiasm for this idea. Indeed, Klaus Villers, without ever having seen the patient, pronounced him such a hopeless case that more aggressive measures should be instigated “at ze first suitable opportunity,” though he’s probably more conservative in his approach to his own patients than anyone else on the staff. The consensus, however, was that little was to be lost by giving my patient a few more weeks to have his say before turning him over to the pharmacologists and surgeons.

There was another facet to the case that I did not mention at that meeting: Prot’s presence seemed to be having a positive effect on some of the other patients in his ward. For example, Ernie was taking his temperature less frequently, and Howie seemed a bit less frenetic. He even sat down one night and watched a New York Philharmonic concert on television, I was told. Some of the other patients were beginning to take a greater interest in their surroundings as well.

One of these was a twenty-seven-year-old woman whom I shall call Bess. Homeless and emaciated when she was brought to the hospital, she had never—not even once— smiled, as far as I am aware. From the time she was a child, Bess had been treated like a slave by her own family. She did all the cleaning and cooking and laundering. Her Christmas presents, when she got anything at all, consisted of utensils and appliances, a new ironing board. She felt it should have been she who perished in the fire that devastated the family’s tenement apartment, rather than her brothers and sisters. It was shortly thereafter that she was brought to us, nearly frozen because she wouldn’t go to one of the shelters the city provides for the homeless.

From the beginning it was difficult to get her to eat. Not, like Ernie, because she was afraid to, or like Howie, was too busy, but because she didn’t think she deserved to: “Why do I get to eat when so many are hungry?” She was certain it was raining on the sunniest days. Everything that happened seemed to remind her of some tragedy, some terrible incident from her past. Neither electroconvulsive therapy nor a variety of neuroleptic drugs had proven effective. She was the saddest person I had ever met.

But on one of my decreasingly frequent travels through the wards I noticed that she was sitting with her knees up and her arms wrapped around them, paying rapt attention to whatever prot might choose to say. Not smiling, but not crying, either.

And seventy-year-old Mrs. Archer, ex-wife of one of America’s foremost industrialists, ceased her constant muttering whenever prot was around.

Known in Ward Two as “the Duchess,” Mrs. Archer takes her meals on fine china in the privacy of her own room. Trained since birth for a life of luxury, she complains constantly about the service she receives, and about everyone’s deportment in general. Amazingly, the Duchess, who once ran naked for a mile down Fifth Avenue when her husband left her for a much younger woman, became a lamb in the presence of my new patient.

The only person who seemed to resent prot’s proximity was Russell, who decided that prot was scouting the Earth for the devil. “Get thee behind me, Satan!” he exclaimed periodically, to no one in particular. Although many of the patients continued to flock to him for sympathy and advice, his coterie was shrinking almost daily and gravitating toward prot instead.

But the point I was making was that prot’s presence seemed to be beneficial for many of our long-term patients. This raised an interesting dilemma: If we were successful in diagnosing and treating prot’s illness, might not his recovery come at the expense of many of his fellow sufferers?