DO WE NEED GOVERNMENTS AT ALL?

Political philosophers ask questions about individuals, communities, society, the law, political power, the State, and about how they all relate.

▶ Is it possible or desirable to say what human beings are “really like”?

▶ What is society? Is it something more than the people who live in it? Or was the British Prime Minister Mrs Thatcher right to say “There is no such thing as society”?

▶ What is the State? Is it an artificial construct or something that has naturally evolved?

▶ How free can the State allow individual citizens to be? Are there good moral reasons why citizens are obliged to obey the law? To what extent does the State have the right to punish those who disobey its commands?

▶ Is democracy the best form of government?

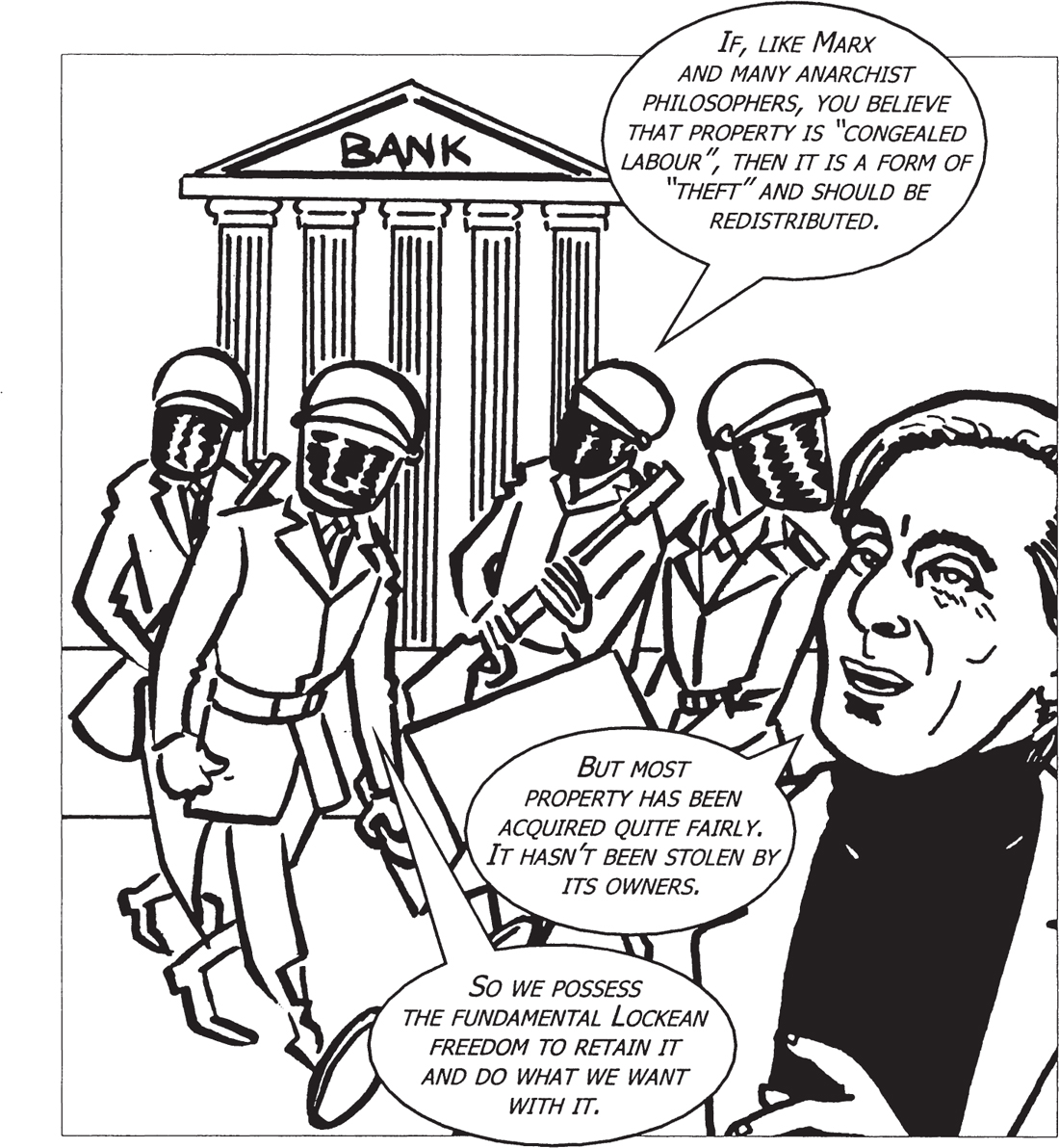

▶ Should the State be interested in furthering economic equality? If so, should it be allowed to interfere with other people’s private property?

DO WE NEED GOVERNMENTS AT ALL?

Many political philosophers begin by concentrating on individuals. After all, societies and states are made up of individuals first, and governments must come after. Are political institutions simply the end result of attempts to fulfil the essential and universal needs of individuals? But what if we have no real knowledge about the needs and purposes of human beings? Besides, we aren’t just dropped into society with all the ready-made capacities that make us human.

THERE CAN BE NO DOUBT THAT SOCIETY MAKES US. EVEN OUR MOST “PRIVATE” THOUGHTS DERIVE FROM LINGUISTIC RESOURCES THAT AREN’T OUR OWN. BUT EVEN THOUGH WE MIGHT ALL BE DERIVATIVE “SOCIAL PRODUCTS”, NONE OF US FEEL WE’RE JUST ROBOTS. PARADOXICALLY, WE ARE MADE BY SOMETHING THAT WE FEEL WE HAVE THE RIGHT (AND DUTY) TO QUESTION.

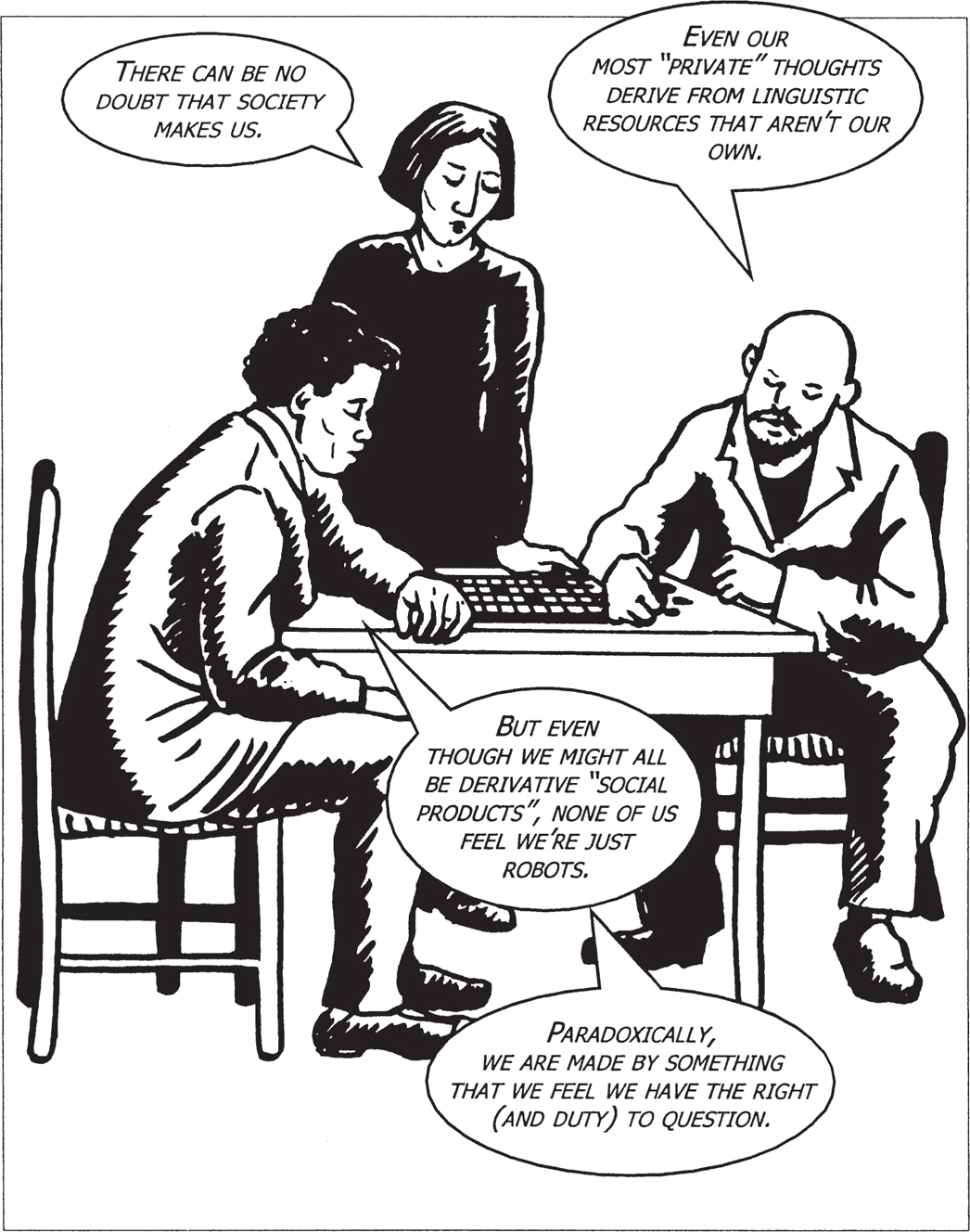

The word “community” suggests something immediate, local and praiseworthy. Political philosophers think of communities as small groups of people with shared values who enjoy solidarity with little need of laws or hierarchical chains of command.

THE EXISTENCE OF COMMUNITIES SUGGESTS THAT HUMAN BEINGS CAN BE SOCIAL WITHOUT NECESSARILY BEING “POLITICALLY GOVERNED”. SO WHAT’S “SOCIETY”, THEN? SOCIETIES ARE LARGER THAN COMMUNITIES AND HELD TOGETHER BY COMPLEX SYSTEMS OF RULES, CUSTOMS AND INSTITUTIONS.

17th-century political philosophers made distinctions between free associations of individuals – societies, perhaps agreed on by some form of “contract” between individuals – and States, which are constituted by specific hierarchical power structures and the threat of coercion.

Is it possible that we are all “social animals” but not necessarily political ones? Where is the evidence for non-political societies? Or is this an idealistic fantasy? Some philosophers believe that distinctions made between societies and States only lead to confusion. Societies can only exist if they are political. Power – and who has it – are features of human life that never go away.

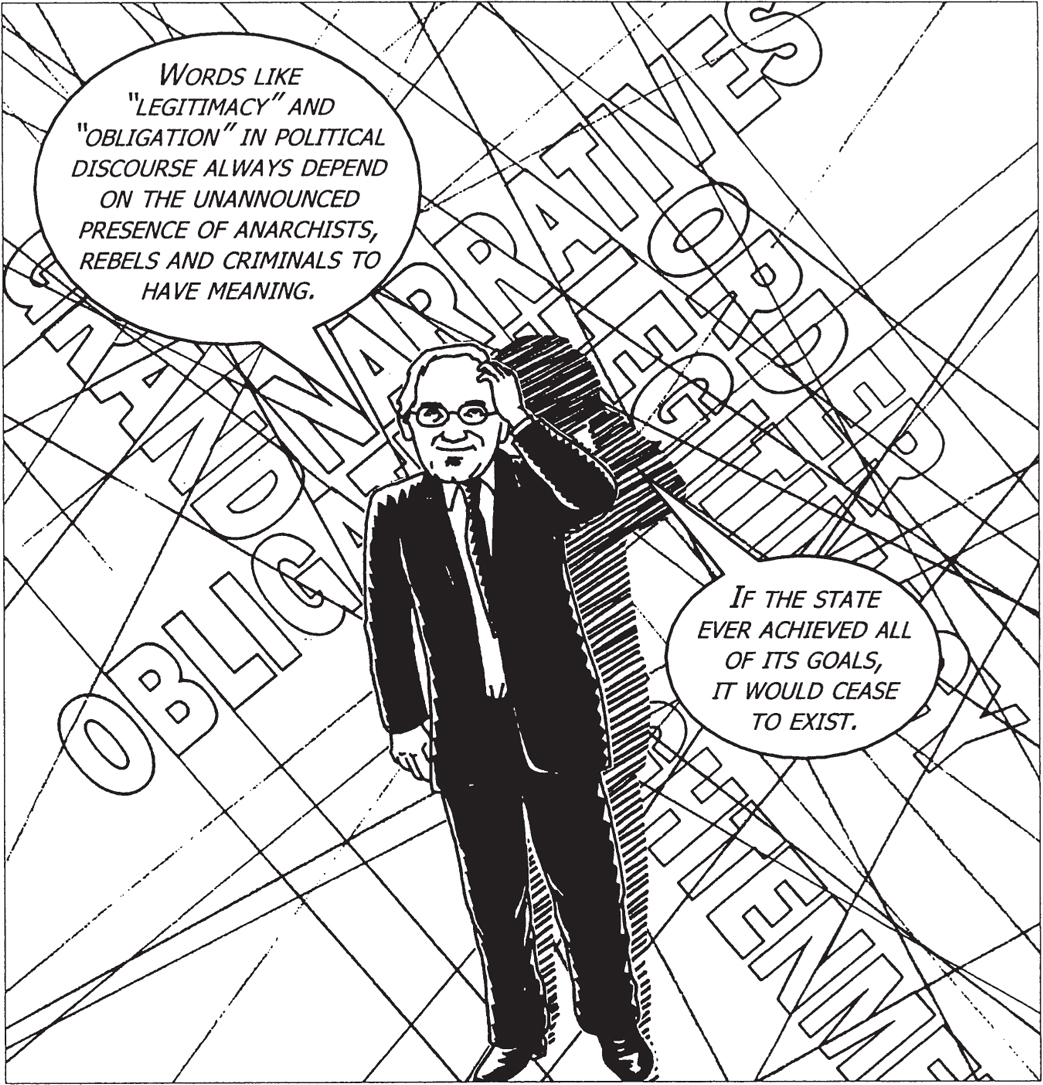

THE “STATE” IS DEFINED AS AN AREA OF TERRITORY WITH AN ORGANIZED LEGAL SYSTEM AND A GOVERNMENT THAT HAS A “LEGITIMATE” MONOPOLY OF FORCE OVER ITS CITIZENS. MODERN STATES HAVE ENORMOUS AND OFTEN INTRUSIVE AUTHORITY… THAT’S WHY PHILOSOPHERS ENDLESSLY REDEFINE WORDS LIKE “CONSENT” “AUTHORITY” AND “OBLIGATION”.

Most modern philosophers accept that moral and political propositions have no factual or logical status. Hence, it is impossible to prescribe what States should be or define what ought to be our relationship to them. Providing definitive answers to political problems must be ruled out.

ALL THAT PHILOSOPHERS CAN DO IS ANALYZE AND MAKE MORE PRECISE THE CONCEPTS WE USE IN EVERYDAY SPEECH – SUCH AS “POWER”, “LAW” “RIGHTS” AND SO ON. BUT POLITICS IS A VERY PRACTICAL AND IMPORTANT REALITY… WE EXPECT ADVICE FROM PHILOSOPHERS, NOT MERELY “ANALYSIS OF CONCEPTS”.

But political philosophy is as ideological as any other kind of discourse. We accept from it what agrees with our normal core beliefs and values. This is why all political concepts are always “essentially contrasted”.

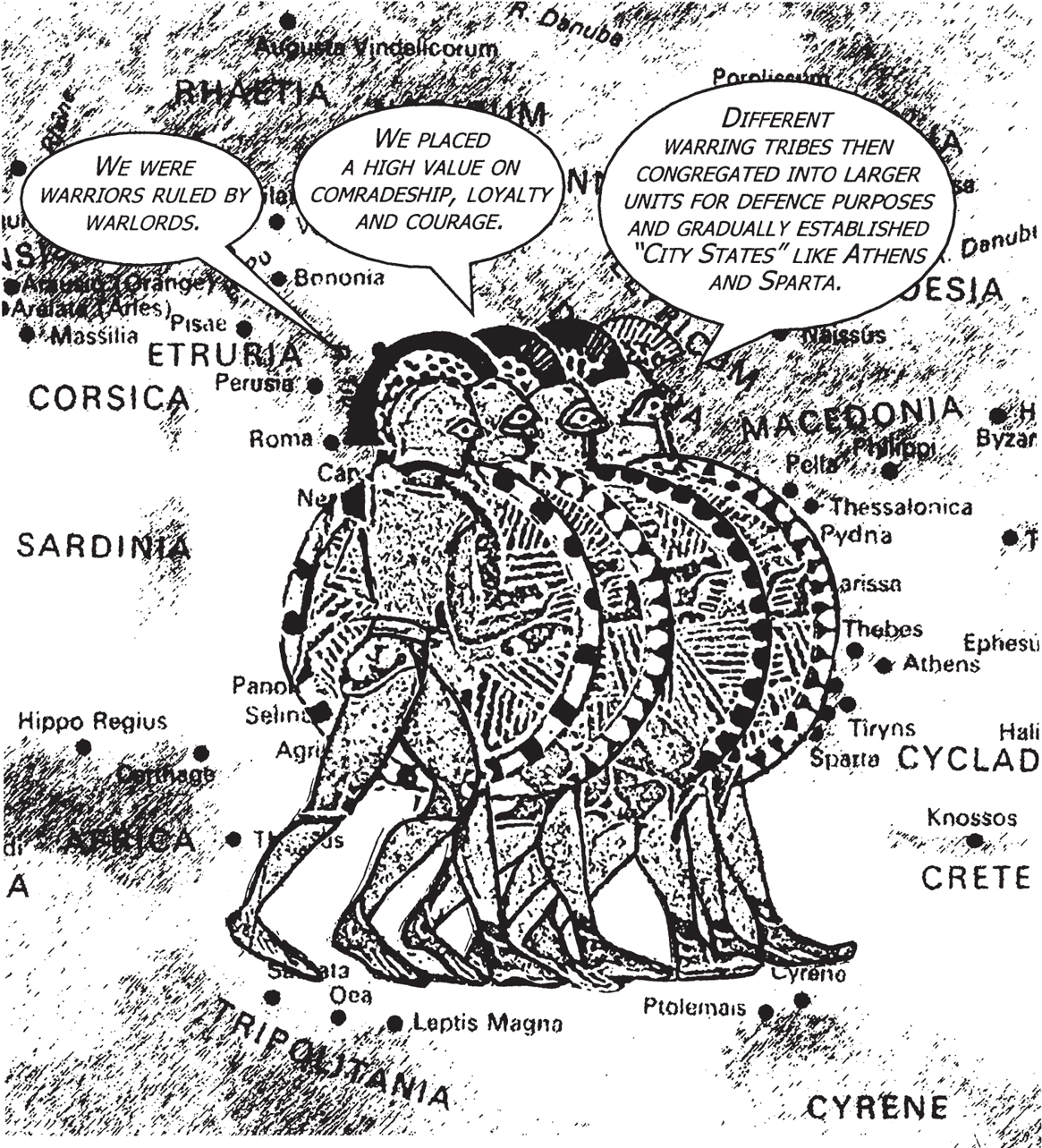

The first people to write about political philosophy were the ancient Greeks. To begin with they were “stateless” semi-nomadic tribes who finally settled all over the coastal regions of the Aegean and Mediterranean.

WE WERE WARRIORS RULED BY WARLORDS. WE PLACED A HIGH VALUE ON COMRADESHIP, LOYALTY AND COURAGE. DIFFERENT WARRING TRIBES THEN CONGREGATED INTO LARGER UNITS FOR DEFENCE PURPOSES AND GRADUALLY ESTABLISHED “CITY STATES” LIKE ATHENS AND SPARTA.

The “Polis” or City State was usually small and independent, and each one was ruled by its own unique kind of government.

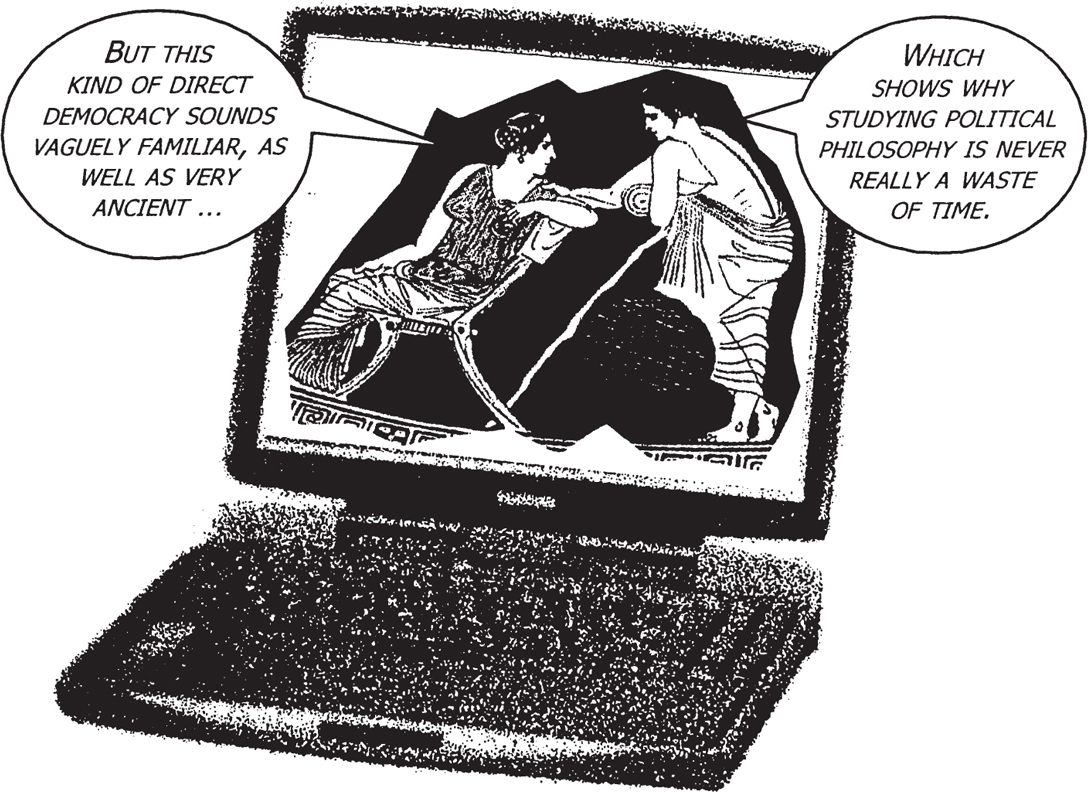

The most interesting and influential “Polis” was Athens, which experienced all sorts of governments. Political power had originally rested in the hands of a kind of aristocracy, similar to a tribal council, but gradually the citizen body itself acquired more and more power, and eventually ruled Athens between 461 and 322 BC.

ATHENS BECAME FAMOUS FOR ITS UNIQUE FORM OF DIRECT PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY. IT INVOLVED ALL OF ITS 50,000 ADULT MALE CITIZENS. BUT NOT WOMEN, SLAVES OR FOREIGNERS!

Being an Athenian “citizen” was a serious business, involving duties as well as rights.

WE DO NOT SAY THAT A MAN WHO TAKES NO INTEREST IN POLITICS IS A MAN WHO MINDS HIS OWN BUSINESS; WE SAY THAT HE HAS NO BUSINESS HERE AT ALL. THE POPULAR ASSEMBLY (I.E. THE “GOVERNMENT”), MADE UP OF ALL ADULT MALE CITIZENS, MET AT REGULAR INTERVALS TO DECIDE ON MATTERS OF STATE. SO ATHENS WAS GOVERNED BY AMATEURS.

The population was small enough for this kind of “pure” democracy to work, and most Athenians seemed to have been immensely proud of their State. They identified with it so completely that it was virtually impossible for any of them to imagine a life outside it.

Athenians fought alongside each other in battle and were more “tribal” than we are now. Their social and political world was very different from ours. They had little conception of “the individual” as something separate from “the citizen” and only very hazy notions of private rights. Society and State were indistinguishable.

FOR MODERN PHILOSOPHERS AND HISTORIANS THIS IS A MAJOR HEADACHE. MANY ANCIENT GREEK WORDS ARE ALMOST IMPOSSIBLE TO TRANSLATE, SO DEEPLY EMBEDDED ARE THEY IN THIS UNIQUE CULTURE. THIS HASN’T STOPPED MOST OF US FROM HAVING FIRM OPINIONS ABOUT THIS ANCIENT STATE RUN BY ITS OWN CITIZENS. Some, like Rousseau, Hegel and other modern “communitarians” think that many of its values and beliefs are exemplary, whereas other “liberals” express grave doubts about its notions of absolute citizenship.

Athenian philosophers were argumentative. They were fascinated by debate and ideas, and invented the subject we now call “philosophy”. This means that they were “modern” because they were critical. They refused to accept religious or traditional explanations for anything and asked disturbingly original questions that no one had ever thought of asking before – especially about “society”, “morality” and “politics” (which derives from the Greek word Polis).

WE EVEN SPECULATED ABOUT WHAT LIFE MIGHT HAVE BEEN LIKE BEFORE “SOCIETY” BEGAN. AS MORE BECAME KNOWN ABOUT STRANGE PLACES LIKE EGYPT AND PERSIA, WE WONDERED HOW “NATURAL” OR “ARTIFICIAL” SOCIETIES WERE. ATHENIANS WERE BEGINNING TO THINK OF THEMSELVES AS INDIVIDUALS, AS WELL AS SOCIAL BEINGS, AND POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY WAS BEGINNING.

Plato (c. 428–347 BC) was the first philosopher to record many of these theoretical discussions about politics. In his book The Republic, Socrates, Plato’s old teacher and friend, discusses the true nature of “justice” with his Sophist philosopher friends. (This “embedded” word “justice” means something like “behaving as you should”.) The Sophists were itinerant, radical thinkers who sold their services as tutors to wealthy families and specialized in teaching rhetoric.

THE SOPHIST THRASYMACHUS BEGINS BY INSISTING THAT ALL GOVERNMENTS ARE FRAUDULENT. EACH TYPE OF GOVERNMENT ENACTS LAWS THAT ARE IN ITS OWN INTEREST: A DEMOCRACY, DEMOCRATIC LAWS; A TYRANNY, TYRANNICAL ONES; AND SO ON. “RIGHT” IS MERELY THE INTEREST OF THE ESTABLISHED GOVERNMENT. IN OTHER WORDS, ALL GOVERNMENTS WHO CLAIM A “NATURAL” RIGHT TO RULE ARE ALWAYS DISGUISING THE FACT THAT THEY RULE IN THE INTERESTS OF ONE PARTICULAR GROUP.

Another Sophist, Glaucon, insists that societies exist only because human behaviour has always to be restrained by law.

WITHOUT LAWS, HUMAN BEINGS ALWAYS REVERT TO BARBARISM, AND SO EVERYONE SUFFERS. THE ONLY REMEDY IS FOR EVERYONE TO AGREE CONTRACTUALLY TO OBEY A FEW COMPULSORY MORAL RULES. SO IT IS ARTIFICIAL LAWS, NOT CO-OPERATIVE INSTINCTS, THAT CONSTITUTE SOCIETIES.

Most Sophists insisted that morality, society, the state and governments are always the artificial creations of human beings – there is nothing at all “natural” or “organic” about them.

Plato rejected this subversive scepticism. Both society and the State are natural, inevitable and benign. His mouthpiece “Socrates” rarely engages in real debate, but hammers away constantly at two ideas – that ruling is a skill, and that all human beings have a specific and prescribed natural function.

SOME PEOPLE ARE JUST SIMPLY BORN RULERS, AND THE REST OF US MUST REMAIN THEIR OBEDIENT WORKERS!

Plato was a communitarian and his ideal society is like a harmonious beehive in which everybody knows their role, and this is what “justice” or “behaving as you should” is all about.

Plato was an aristocrat, so his ideal hierarchical society of born rulers and submissive workers isn’t much of a surprise. But his advocacy of this orderly beehive rests on more than simple class loyalty. Plato was wholly convinced by the Pythagorean vision of mathematics. Numbers are “pure” – uncontaminated by the world, independent of human desires, eternal, incorruptible and always true. 2+2 will always equal 4, regardless of whether human beings exist or not.

ALL REAL KNOWLEDGE HAS TO BE LIKE NUMBERS – PERMANENT AND TRANSCENDENT. ALL WE SEE AROUND US ARE FEEBLE, TRANSIENT “COPIES” OF THE MORE REAL “FORMS” MYSTERIOUSLY ENCODED INTO THE UNIVERSE AND HUMAN MINDS.

Plato’s idealist metaphysics of “pure Forms” is the result of a whole series of linguistic confusions. It meant that there had to be a perfect “Form” for “The State”. His Republic is largely concerned with the education of the State’s rulers called “The Guardians” – an élite group of political experts who know all there is to know about “The Perfect State”, composed of a hierarchy of metals.

THE “GOLD” GUARDIANS RULE OVER EVERYONE. THERE ARE “SILVER” ADMINISTRATORS … AND BELOW THEM, “BRONZE” AND “IRON” WORKERS WHO ALL HAPPILY ACCEPT THEIR PLACE IN OUR STABLE, SELF-PERPETUATING AND PERFECT STATE.

This vision of a highly disciplined “command society” has always attracted those whose political instincts are authoritarian. Plato’s ideal republic has been condemned for its incipient totalitarianism and praised for its celebration of community values, in more or less equal measure.

We now think that human knowledge is intrinsically fallible and relative. What seems “true” to us about the planets and the stars today will probably seem mostly “false” to us in a few years’ time. Citizens of the future may be astonished at the political beliefs we hold now. Philosophers now consider it highly unlikely that there are such things as moral or political “facts”, let alone mysterious transcendent “Forms”.

IF THIS IS SO, THEN PLATO’S IDEALIST PHILOSOPHICAL “SYSTEM” IS WHOLLY UNDERMINED BY HIS “EPISTEMOLOGY” (HIS THEORY OF KNOWLEDGE). IF THERE ARE NO PERFECT “FORMS” THEN THERE CAN BE NO PERFECT KNOWLEDGE, MORALITY, STATES OR RULERS.

So Protagoras the Sophist was probably right to insist that the amateurs of Plato’s own democratic Athens had as much right to rule as anyone else.

Plato had an incurable dislike of the Athenian democratic government that had put his teacher, Socrates, to death in 399 BC. In The Republic he compares democracy to a ship with a mutinous crew.

THE SHIP’S CAPTAIN IS LOCKED UP, THE NAVIGATOR IGNORED, AND THE CREW HAS EARS ONLY FOR THE FOOLISH WORDS OF THEIR REBELLIOUS DEMAGOGUE LEADER WHO JUST PROMISES THEM WHAT THEY ALL WANT. COME ON FRIENDS, LET’S GO ON A PLEASURE CRUISE!

But their leader has no knowledge of navigation, the boat goes on the rocks and everyone drowns. Democracy, in other words, is leadership by the stupid, who make unrealizable promises to the ignorant, and this always leads to disaster.

Those who get impatient with the squabbles, delays, horse-trading, populism and general inefficiencies of democracy have often been attracted to the idea of Plato’s elitist government. But most of us still think that democracy is a good idea and preferable to all other political ideologies on offer. Plato’s analogies are also misleading.

WE SHOULD HAVE A SAY ABOUT THIS JOURNEY MADE BY OUR SHIP OF STATE! WE DEMOCRATIC CITIZENS ARE THE BOAT’S OWNERS AND NOT MERELY ITS “CREW”! INFORMED POLITICAL DEBATES ARE NORMALLY PREFERABLE TO MONOLITHIC CERTAINTIES IMPOSED FROM ABOVE.

One true mark of a healthy political society may be that its educated citizens engage in debate rather than passively obey orders. Democracies also enable citizens to remove corrupt or incompetent governments, without the need for violent revolution or civil war. But if you think that voters have become directionless consumers influenced by spin-doctors, or feel that politicians are now just populists led by focus groups, then Plato’s attacks on democracy might be worth thinking about.

Plato’s most famous student was the independently minded Aristotle (384–322 BC), who disagreed with most of what Plato taught him. Like most ancient Greeks, he believed in “teleological” or “final” causes.

EVERYTHING IN THE UNIVERSE IS DESIGNED FOR A SPECIFIC FUNCTION. SO, FOR THE GREEKS, THE WORD “GOOD” MEANT SOMETHING LIKE “ACHIEVING ITS PURPOSE”. ORGANIC THINGS CAN LOOK AS IF THEY HAVE A PURPOSE – A “GOOD” OAK TREE IS TALL AND STRONG AND A “GOOD” CAT IS AN EFFICIENT MOUSER.

Darwinists now think this is the wrong way to think about natural objects and causes. Natural objects may look perfectly designed, but this is because they have evolved that way, not because there is some mysterious cause pulling them towards perfection. If their environment changed, this would cause or “push” them to change, or face extinction.

But, for Aristotle, this comprehensive teleological biology made perfect sense. It meant that human beings could only ever be “good” or happy if they “flourished”. So politics needs to be a consequence of human nature. Everyone accepts that there are clear criteria we can use to judge whether certain kinds of qualified people, like carpenters and cobblers, are successful.

SO, IS IT LIKELY THAT JOINERS AND SHOEMAKERS HAVE CERTAIN FUNCTIONS, WHILE MAN AS SUCH HAS NONE, AND HAS BEEN LEFT BY NATURE AS A FUNCTIONLESS BEING? WHAT IS OUR ONE BIG UNIVERSAL FUNCTION AS HUMAN BEINGS? IT CANNOT BE MERE SURVIVAL.

By examining his fellow humans and himself, Aristotle concluded that the one thing that makes us wholly different from the rest of the natural world is our ability to reason. It is that we must cultivate, if we are to reach our inbuilt destiny.

A “good” or well-functioning human being is one who reacts appropriately (“rationally”) to every situation, usually by avoiding extremes of behaviour.

THE FUNCTION OF A MAN IS THE EXERCISE OF HIS SOUL, IN ACCORDANCE WITH A RATIONAL PRINCIPLE. THE FUNCTION OF A GOOD MAN IS TO EXERT SUCH ACTIVITY WELL. THE BEST SOCIETIES AND STATES ARE THEREFORE “RATIONAL” AND “MODERATE” ONES THAT FOSTER A COLLECTIVE SPIRIT OF MUTUAL CO-OPERATION AND RESPECT.

This means that individuals must think of themselves as citizens first and actively participate in political life, not just passively obey the law. Aristotle’s political philosophy isn’t exactly startling, but it avoids the utopianism of Plato’s Republic. If infallible experts do not exist, then politics has to be something rather more pragmatic.

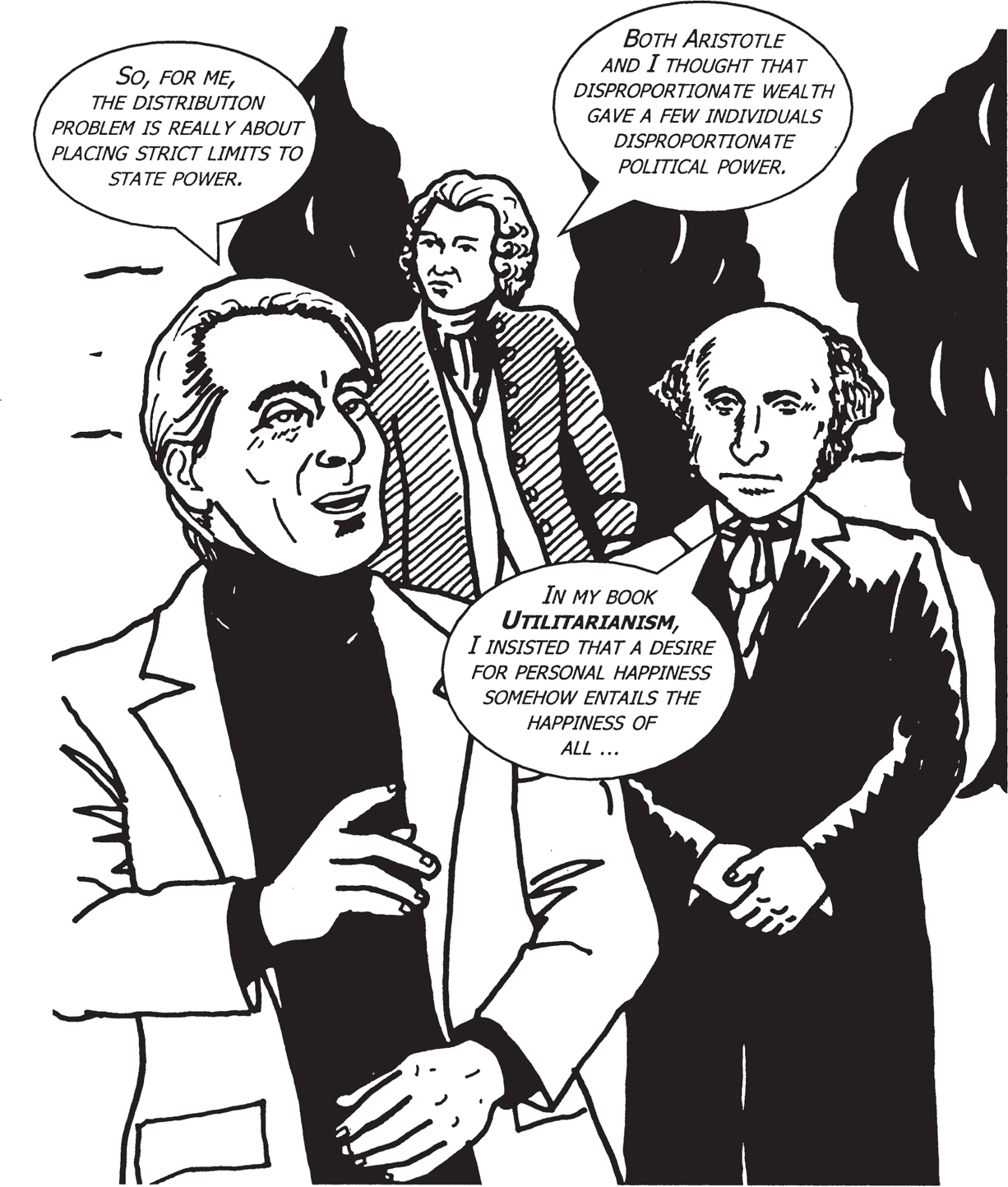

In The Politics, Aristotle recognized that political authority has to depend, to some extent, on the consent of the governed. Since different societies choose different sorts of government, there may not be one “perfect” State. Nevertheless, Aristotle disapproved of oligarchies (rule by the rich) and democracies (rule by the poor).

I FAVOUR A FORM OF “ARISTOCRATIC” RULE BY THOSE BEST QUALIFIED – A SYSTEM WHICH I CALLED “POLITY”.

Aristotle believed that the majority of citizens should be of “middling wealth”, so that political equality could not be undermined by economic inequality. Unfortunately, most Athenians would also have agreed with him that slaves were merely fulfilling their “natural” function.

THEIR FUNCTION IS THE USE OF THEIR BODIES, AND NOTHING BETTER CAN BE EXPECTED OF THEM. THEY ARE SLAVES BY NATURE. WOMEN WERE ALSO NOT “NATURALLY” SUITED TO POLITICAL LIFE.

Aristotle was the first philosopher to insist that political life has to be founded on some descriptive account of human nature.

EVERY FOOL PRESUMES TO SPEAK AUTHORITATIVELY OF HUMAN NATURE. BUT THERE ARE LOTS OF DIFFERENT VIEWS ABOUT WHAT HUMAN BEINGS ARE “REALLY LIKE”. YOUR OWN VIEW OF HUMAN NATURE WILL DETERMINE WHAT YOUR ETHICAL BELIEFS ARE AND HOW YOU SHOULD BEHAVE TOWARDS OTHER PEOPLE. IT WILL PROBABLY INFLUENCE YOUR POLITICAL VIEWS ON HOW SOCIETY SHOULD BE ORGANIZED.

Your beliefs about yourself and your fellow humans may suggest the meaning and purpose of human life to you, offer a remedy for all that is wrong with the world and may also inspire you with a vision of what society should be like.

But your theories and “facts” about human nature are very unlikely to be “value free”. They’ll be a reflection of your ideology.

Ideologies ultimately have a political function. They are normally the beliefs, attitudes and values used to legitimize the power of specific interest groups. They are also usually implicit and “naturalized” so that they remain safely unquestioned.

THE MORE UNEXAMINED THEY ARE, THE MORE POWERFUL THEY TEND TO BE. THAT IS WHY MOST WESTERNERS TEND “IDEOLOGICALLY” TO HAVE A HIGH REGARD FOR DEMOCRATIC GOVERNMENTS AND CAPITALISM, WHICH THEY THINK OF AS “NATURAL”.

The belief that there actually is something called “human nature” is now often criticized as “essentialist”. If there are some fundamental truths about what people are “really like”, then it makes sense to say that these truths should determine how society is organized.

IF, LIKE ME, YOU BELIEVE THAT MOST PEOPLE ARE “ESSENTIALLY” WICKED, THEN YOU’LL BELIEVE IN A REPRESSIVE AND HEAVILY POLICED SOCIETY. IF YOU ARE ALREADY IN FAVOUR OF AN AUTHORITARIAN SOCIETY, THIS PESSIMISTIC ACCOUNT OF “ESSENTIALLY WICKED" HUMAN NATURE MAKES FOR A GOOD EXCUSE.

Theories about human nature also raise metaphysical questions about how free or individual we are in our beliefs and behaviour. Some philosophers suggest that we have no essential human nature but are more like blank sheets of paper “written on” by our social and economic environment. Evolutionary psychologists can be equally determinist when they insist that we are all products of our genetic inheritance.

HUMAN BEINGS ARE EVOLVED PRIMATES WHO POSSESS ALL KINDS OF UNIVERSAL AND INESCAPABLE INNATE DRIVES AND INSTINCTS WHICH DETERMINE HOW AND WHAT WE THINK. THE EXISTENTIALIST PHILOSOPHER JEAN-PAUL SARTRE (1905–80) BRAVELY INSISTED THAT THERE IS NO “HUMAN ESSENCE” AT ALL … WE ARE “CONDEMNED TO FREEDOM” AND RESPONSIBLE BOTH FOR CHANGING OURSELVES AND OUR SOCIETY.

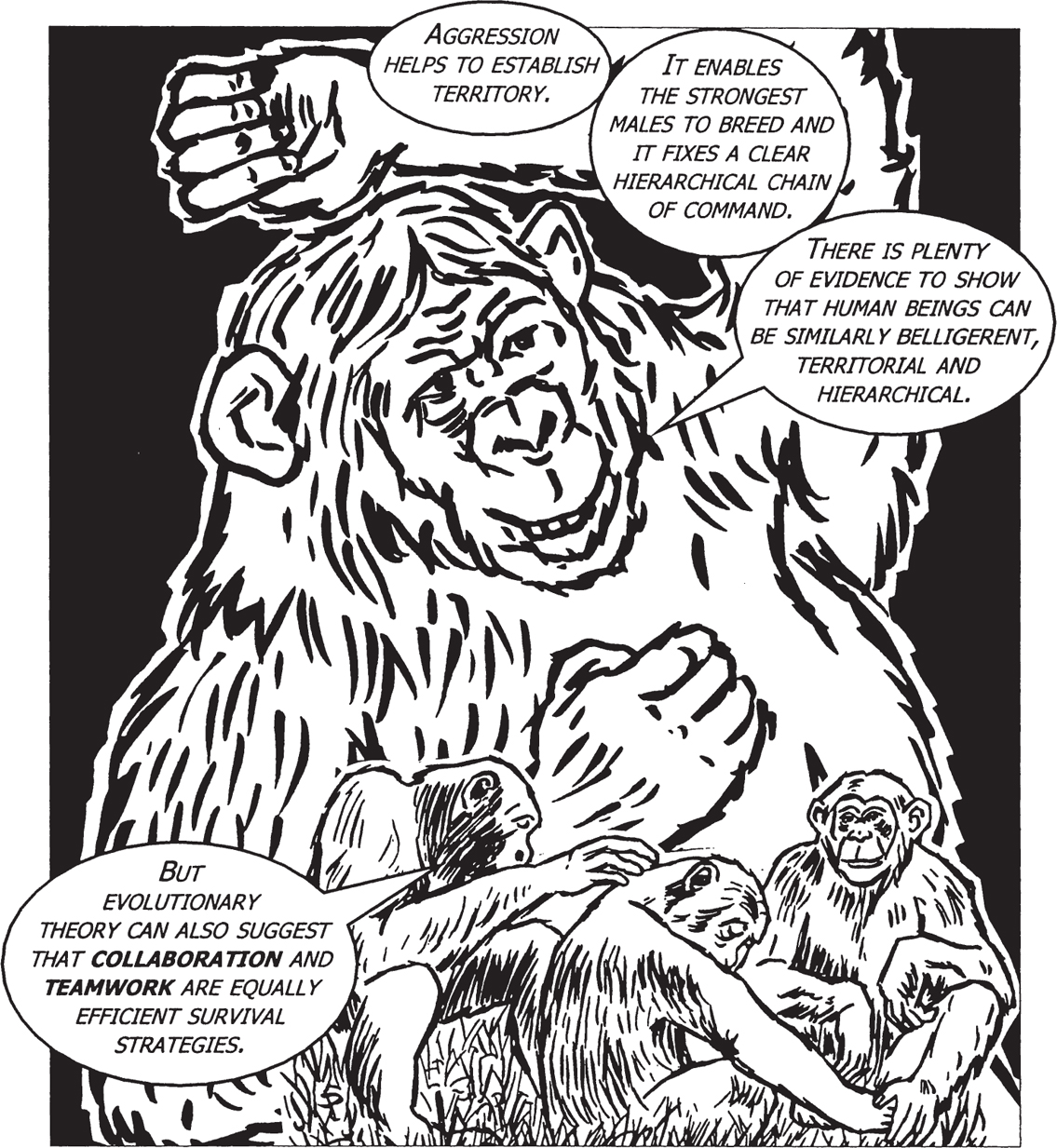

Our physical bodies are the result of millions of years of evolution. Evolutionary psychologists suggest that the same is true of our “human nature”. We all have certain inbuilt instincts and behavioural traits which are a direct result of our evolutionary past. What especially useful “survival genes” human beings have evolved is not entirely clear. In some non-human animals, aggression is clearly a useful survival mechanism.

AGGRESSION HELPS TO ESTABLISH TERRITORY. IT ENABLES THE STRONGEST MALES TO BREED AND IT FIXES A CLEAR HIERARCHICAL CHAIN OF COMMAND. THERE IS PLENTY OF EVIDENCE TO SHOW THAT HUMAN BEINGS CAN BE SIMILARLY BELLIGERENT, TERRITORIAL AND HIERARCHICAL. BUT EVOLUTIONARY THEORY CAN ALSO SUGGEST THAT COLLABORATION AND TEAMWORK ARE EQUALLY EFFICIENT SURVIVAL STRATEGIES.

Most importantly, however, unlike animals we are not trapped in a routine of unthinking instinctive responses. Human beings can choose to suppress their combative or co-operative instincts.

Comparing ourselves to animals is problematic and potentially misleading because ideology gets in the way.

The anarchist Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921) believed that a co-operative society was totally “natural”. Rich Victorian industrialists also examined nature, but came to very different and very convenient “Social Darwinist” conclusions.

BEES ARE CO-OPERATORS, SO SOCIABILITY MUST BE THE MAIN FACTOR IN ALL EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES. HUMAN ECONOMIC STRUGGLES AND INEQUALITIES ARE AS INEVITABLE AS ALL THE “SIMILAR” ONES OCCURRING IN THE NATURAL WORLD. IT’S QUITE NATURAL FOR US TO BE RICH AND THEM TO BE POOR. SO, WHAT YOU GET FROM EVOLUTION DEPENDS ON WHAT YOU WANT TO FIND IN IT.

It seems unlikely that human beings have survived by constantly fighting each other. It’s just as probable that human beings evolved as a successful species because they co-operated. Aristotle seems right to believe that it is as “natural” for gregarious human beings to live in groups as it is for them to have ten toes.

GROUPS OF PEOPLE ARE MORE EFFICIENT THAN ISOLATED INDIVIDUALS. WE CAN HUNT MORE EFFECTIVELY AND SHARE OUT OUR GOOD FORTUNE. SO, MOST INDIVIDUALS PROBABLY JOIN AND REMAIN IN GROUPS OUT OF ENLIGHTENED SELF-INTEREST – THAT WAY, YOU EAT MORE REGULARLY AND GET PROTECTION FROM ENEMIES.

Human beings usually place a high value on co-operation, generosity and sympathy, and disapprove of more egotistical behaviour. But living in groups can also have the drawbacks of conformity and obedience to tradition. Close-knit communities can stifle individuality, imagination and invention, and worse – encourage hostility to all those perceived as “outsiders”.

One way of testing many of these “co-operative” hypotheses about human nature is called “game theory”, which seems to show that people are usually nice to each other for selfish reasons. The best way to survive a large number of complex win-or-lose games is to adopt a “Tit-for-Tat” strategy.

YOU BEGIN BY CO-OPERATING WITH EVERYONE AND THEN KEEP DOING SO IF THEY CO-OPERATE WITH YOU. BY ESTABLISHING A SERIES OF LONG-TERM, STABLE AND REPETITIVE RELATIONSHIPS, YOU CAN BUILD UP “POINTS” IN A RELATIVELY STRESS-FREE AND PREDICTABLE WAY.

Reciprocity pays off. But the strategy works only if the games are played by relatively small groups in which each “player” can remember the names and previous behaviour of other players. This may be why Athenian democracy “worked”.

Evolutionary psychology and game theory seem to point to certain conclusions that are awkward for those who dream of an ideal utopian society. Humans are complicated beings who are quite prepared to be benevolent, but only if there is some kind of payback.

WE MAY BE SELFISH AT HEART, BUT IT IS THAT SAME SELFISHNESS THAT PROVIDES US WITH THE BEST REASON FOR HELPING OTHERS. BUT UNADULTERATED SELFISHNESS PRODUCES ONLY SHORT-TERM GAINS. A CAPITALIST SOCIETY THAT ENCOURAGES AND CELEBRATES RAPACIOUS INDIVIDUAL GREED PROBABLY GOES AGAINST WHAT EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY TELLS US ABOUT OUR NATURE AS GROUP ANIMALS.

Likewise, a benign but large society that is overburdened with too much government and impersonal bureaucracies may remove from its millions of anonymous members any sense of self-responsibility or reciprocity, and destroy what small sense of community remains.

The frustrating conclusion is that it is very difficult to know what human nature “really is”, and probably impossible to describe it with any degree of objectivity.

WE’RE ALL SO DEEPLY EMBEDDED IN A SPECIFIC WAY OF LIFE HAVE BELIEFS WHICH ARE PROBABLY NOT OUR OWN AND THINK IN A LANGUAGE WHICH MAY WELL PREDETERMINE HOW WE CONCEPTUALIZE OUR WORLD. IT’S THEREFORE JUST AS HARD TO SAY WHETHER SOCIETIES OR STATES ARE “NATURAL” IN THE WAY THAT ARISTOTLE THINKS THEY ARE.

Political philosophers will probably always disagree about how static or dynamic, rational or irrational, perfectible or corrupt, self-interested or altruistic we all are. It is not very clear how we can ever judge who is right or wrong about the matter.

States may have little to do with any essentialist models of human nature. Capitalist societies may be a “natural” development from the way we are, but could just as likely be an artificial aberration based on a misleading model of human nature.

ANARCHISTS SAY THAT HUMAN BEINGS CAN LIVE CO-OPERATIVELY, WITHOUT THE NEED OF STATE COERCION. GAME THEORY SEEMS TO SUGGEST THAT ANARCHISTS MIGHT BE RIGHT – PROVIDED THERE AREN’T TOO MANY POWER-HUNGRY INDIVIDUALS, CRIMINALS OR “FREE-RIDERS” AROUND. HUMAN BEINGS HAVE, AFTER ALL, LIVED WITHOUT GOVERNMENT FOR THOUSANDS OF YEARS MORE THAN THEY’VE LIVED WITH IT.

The State is a relatively recent invention. But there are no easy or instant answers. Political philosophy isn’t an empirical science. All it can do is clarify and debate these seemingly insoluble problems which always seem to emerge whenever human beings investigate themselves.

Aristotle was from Macedonia, and it was an invasion from his homeland that finally finished off the Greek City States. A unique kind of political philosophy, which stressed the importance of civic life, disappeared.

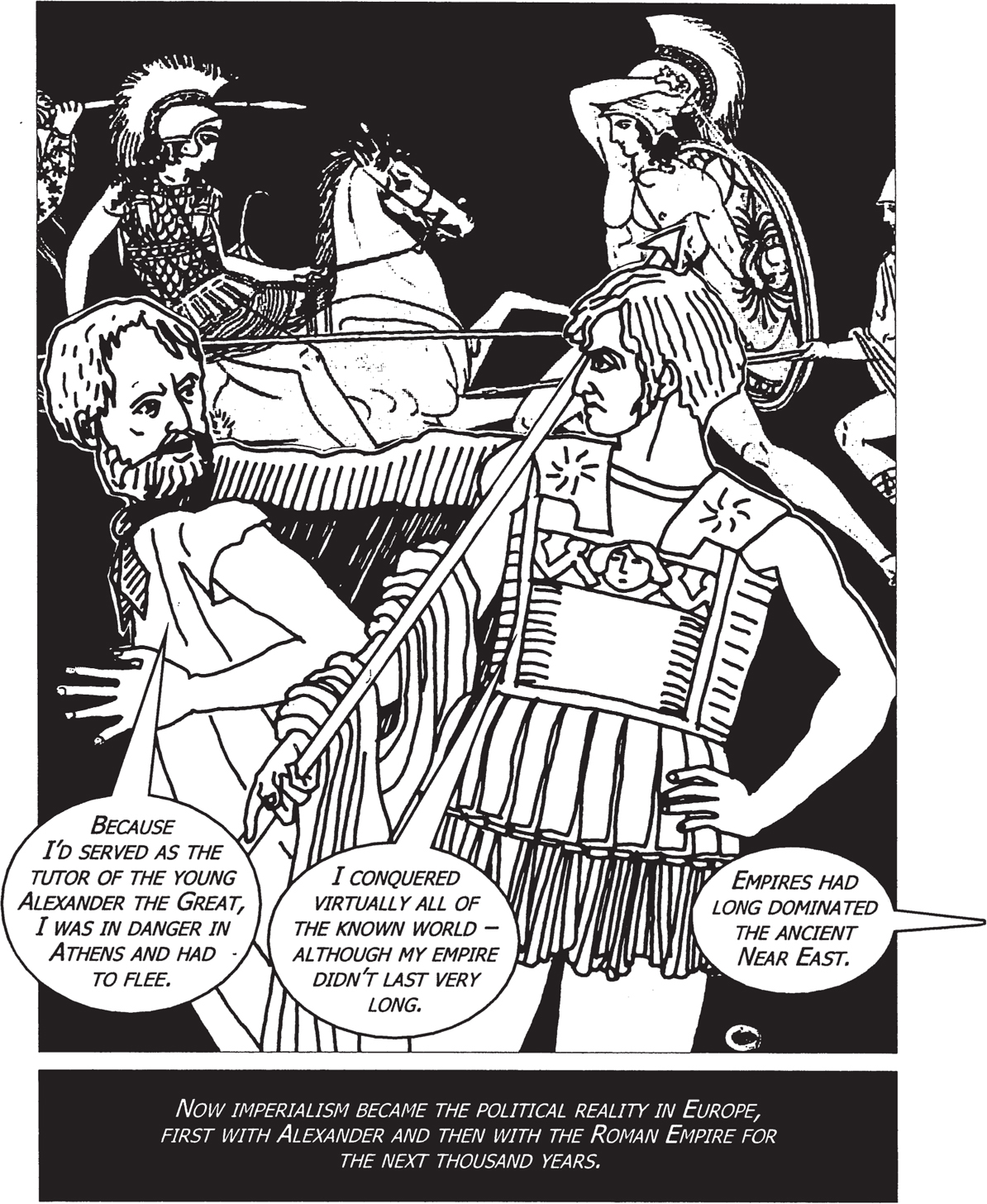

BECAUSE I’D SERVED AS THE TUTOR OF THE YOUNG ALEXANDER THE GREAT, I WAS IN DANGER IN ATHENS AND HAD TO FLEE. I CONQUERED VIRTUALLY ALL OF THE KNOWN WORLD – ALTHOUGH MY EMPIRE DIDN’T LAST VERY LONG. EMPIRES HAD LONG DOMINATED THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST. NOW IMPERIALISM BECAME THE POLITICAL REALITY IN EUROPE, FIRST WITH ALEXANDER AND THEN WITH THE ROMAN EMPIRE FOR THE NEXT THOUSAND YEARS.

The philosophers who emerged all over the Hellenistic and Roman worlds – Cynics, Sceptics, Epicureans and Stoics – had little time for political philosophy in a world that now seemed unpredictable and dangerous. The Cynic Antisthenes (c. 440-c. 370 BC) was the first Greek anarchist.

I WANT NOTHING TO DO WITH GOVERNMENTS, RELIGION OR PRIVATE PROPERTY. I AM ANOTHER CYNIC, DIOGENES (404–323 BC), AND CLAIM TO BE A “CITIZEN OF THE WORLD”. WE SCEPTICS FINALLY TOOK OVER PLATO’S ACADEMY, BUT HAD LITTLE INTEREST IN POLITICS. EPICUREANS ARE SENSIBLE ENOUGH TO REALIZE THAT ENGAGING IN POLITICAL DISCUSSIONS IS EXCEEDINGLY RISKY… WE RECOMMEND THAT HUMAN HAPPINESS IS SOMETHING THAT CAN NEVER BE FOUND IN POLITICAL LIFE.

The most famous Stoic philosophers were the Romans Seneca (2 BC-AD 65), tutor to the infamous Emperor Nero, and Emperor Marcus Aurelius (AD 121–180).

OUR PHILOSOPHY HAS MORE TO SAY TO THE PRIVATE INDIVIDUAL THAN THE CITIZEN. THE GOOD LIFE IS IN RETIREMENT FROM POLITICAL STRIFE. THE ROMAN EMPIRE IN WESTERN EUROPE COLLAPSED IN THE 5TH CENTURY.

The only civilized discussions about politics took place within the Christian Church, which was established as the official religion of the Roman Empire by Emperor Constantine around AD 320. The Church dominated all intellectual life until the Renaissance of the 15th century.

Medieval Christian theologians were pessimistic about human nature and therefore the possibility of any perfectible secular State. Christianity teaches that we are immortal souls, trapped in physical bodies, whose ultimate destiny therefore lies beyond this material plane. It’s a very powerful “dualist” model of human beings.

THIS MEANS THAT IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO HAVE ANY REAL KNOWLEDGE OF HUMAN NATURE… NOT BECAUSE IT DOESN’T EXIST, BUT BECAUSE “HUMAN NATURE” IS A SPIRITUAL ENTITY THAT NO AMOUNT OF MATERIALIST AND REDUCTIONIST SCIENCE CAN EVER FULLY PIN DOWN.

St Augustine (AD 354–430) lived at a time when Roman civilization was collapsing. Rome was sacked by invading Goths in 410, and many Romans blamed Christians for their apparent lack of interest in the survival of the State. In his book The City of God, Augustine attacks the classical Greek idea that human beings are somehow “fulfilled” by living in a rational City State.

HUMAN BEINGS ARE INTRINSICALLY IRRATIONAL AND VOLATILE. THIS IS WHY GOD HAS SANCTIONED EARTHLY GOVERNMENTS – TO PRESERVE THE PEACE AND ADMINISTER JUST LAWS.

Citizens should obey governments and fight in “just wars”. But the true destiny for all human beings lies elsewhere – they are really “citizens of an eternal kingdom” beyond this one.

The Dominican monk in Italy, St Thomas Aquinas (1225–74), was rather more optimistic about the State. In his Summa Theologiae, Aquinas described all the “Natural” or “Divine” Laws which govern everything in the universe, from gravity to human morality.

I AGREE WITH ARISTOTLE. CHRISTIANS, LIKE ALL HUMAN BEINGS, ARE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ANIMALS WITH A DESIRE TO LIVE IN SOCIETY. THE FELLOWSHIP OF SOCIETY BEING NATURAL TO MAN, IT FOLLOWS THAT THERE MUST BE SOME PRINCIPLE OF GOVERNMENT.

As conscious and rational beings, they are able to work out which universal “natural laws” apply to themselves. (These turn out to be mostly about “refraining from harm” and “reciprocity”.)

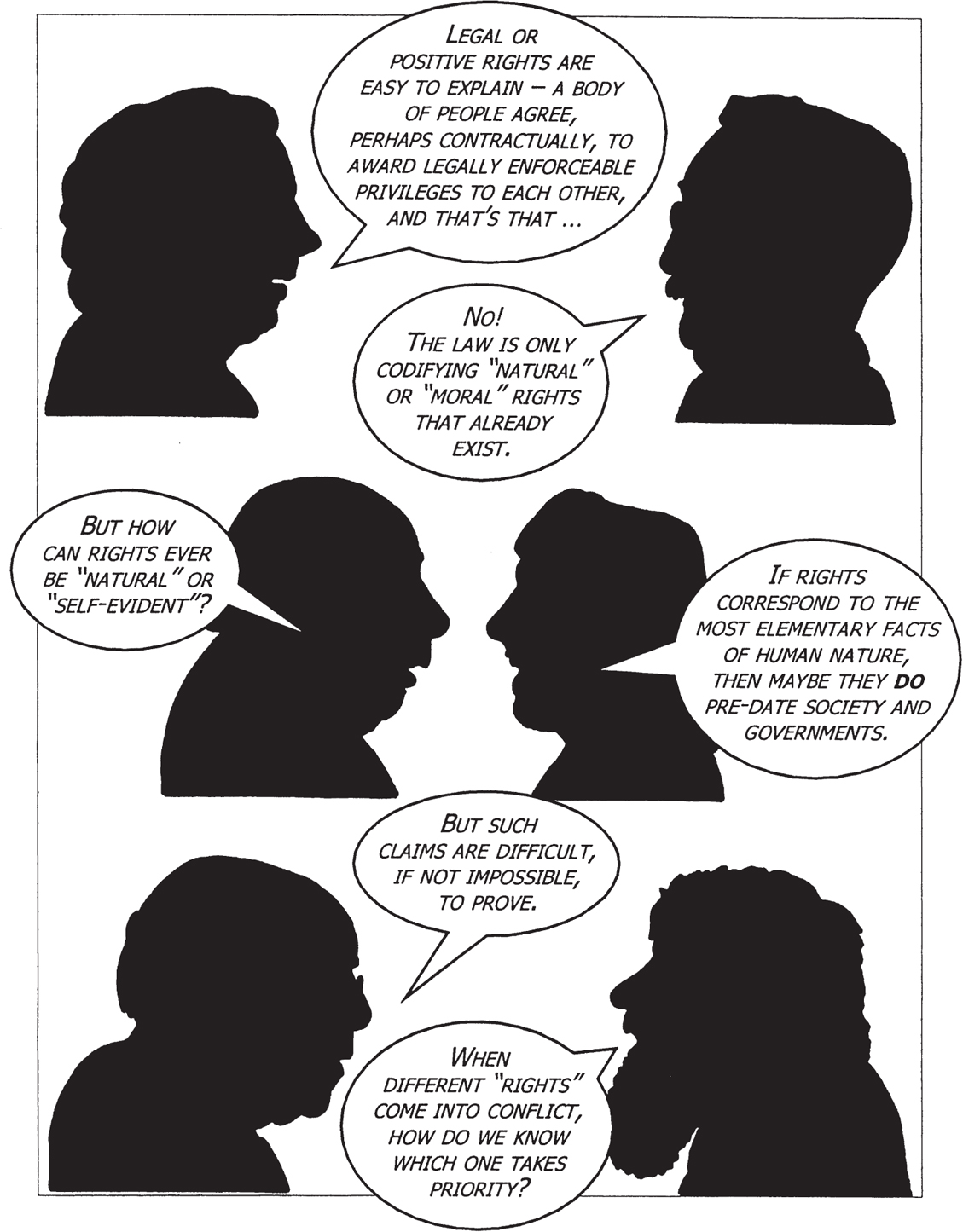

The “positive” or secular laws of the state are derived from natural laws. So, if positive law ever contradicts natural law, then it is invalid and can be disobeyed.

A tyrannical ruler can therefore be justifiably rejected by his people (even though the overthrow of governments usually leads to even greater suffering).

Aquinas’ idea of “Natural Law” came to dominate much 17th-century political philosophy. Nowadays, we make clear distinctions between the descriptive “laws” of nature and prescriptive laws that are man-made.

WE THINK THERE IS AN OBVIOUS DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SOMEONE “OBEYING” THE LAW OF GRAVITY BY FALLING OFF A CLIFF… AND SOMEONE FILLING IN A FORM IN ORDER TO OBEY THE LAWS ON TAXATION. BUT THE FICTION OF ANCIENT PRE-POLITICAL “NATURAL LAWS” OR “RIGHTS” AS LAID DOWN BY GOD, CAN BE A USEFUL TOOL WITH WHICH TO CRITICIZE TYRANNICAL GOVERNMENTS THAT MISTREAT THEIR CITIZENS.

That highly complex cultural phenomenon known as the “Renaissance” began in Northern Italy in the 14th century and quickly spread throughout Europe during the following two centuries. It inspired a new spirit of enquiry into all aspects of human life, including politics.

IN THE NEWLY PROTESTANT COUNTRIES OF NORTHERN EUROPE, IT BECAME POSSIBLE TO ARGUE AND DEBATE POLITICAL THEORY MORE OPENLY. AT LAST WE CAN ASK RADICALLY NEW QUESTIONS ABOUT THE ROLE OF THE STATE AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO ITS CITIZENS. ITALY ITSELF WAS DOMINATED BY A FEW POWERFUL CITY STATES LIKE VENICE AND FLORENCE.

Many contemporary inhabitants compared these states to ancient Athens, even though none of them were particularly “democratic”. They were ruled either by princes or cabals of rich families. But they did squabble among themselves, just like Athens and Sparta had done.

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) was a practising Florentine politician who did something unusual – he described the behaviour of politicians and wrote about politics as it is, rather than prescribing what it should be, as nearly all political philosophers had done before and since. His book The Prince shocked the whole of Europe and a new word – “Machiavellian” – was used to describe a specific kind of amoral opportunism. His book is about “realpolitik” – the grim reality of everyday political life.

MINE IS A HANDBOOK FOR THOSE WHO WISH TO PURSUE POLITICAL POWER – OR HANG ON TO IT. CHRISTIAN MORALITY IS CLEARLY INAPPROPRIATE FOR ANY PRINCE WHO WISHES TO MAINTAIN A STRONG AND SUCCESSFUL STATE.

Machiavelli observed what politicians actually do – like the infamous Duke Cesare Borgia – and drew some fairly unpalatable conclusions from their behaviour.

Wise politicians will lie and break their promises, if it is politically advantageous to do so. Even assassination is justified if it gets results.

A RULER NEEDS THE CUNNING AND FLEXIBILITY OF THE FOX AND THE STRENGTH AND COURAGE OF THE LION. THE MORALITY OF POLITICS CANNOT BE THAT PRESCRIBED BY RELIGION. I DON’T RECOMMEND UNDERHAND PRACTICES, BUT THEY ARE SOMETIMES NECESSARY,

And although Machiavelli thought that republics with a measure of popular support were the best form of government, he realized that most people are more interested in security than the morality of their governments.

Machiavelli saw that it was power, exercised with ruthless efficiency, that established and maintained stability and prosperity.

WHETHER MACHIAVELLI IS A “PHILOSOPHER” OR NOT IS DEBATABLE – HIS INTERESTS ARE NOT THOSE OF CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS. ABSTRACT THEORIZING IS A WASTE OF TIME! IT ACTUALLY OBSCURES THE REALITIES OF POLITICAL LIFE.

His “infamous” book paved the way for a new kind of political philosophy that had a more cynically realistic view of human nature, and a less idealistic vision of the State and its function.

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) was born in the year of the Spanish Armada. He spent most of his life as tutor to the children of the Earls of Devonshire and, as a royalist, had to escape to France to avoid the English Civil War and the rule of Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658). Hobbes is often thought of as the first great modern political philosopher.

IN MY BOOK LEVIATHAN, I TRIED TO SHOW HOW SOCIETY AND GOVERNMENTS WERE NEITHER ORDAINED BY GOD NOR “NATURAL”… THE STATE IS AN ARTIFICIAL CREATION, WHOLLY UNNATURAL BUT NEVERTHELESS ESSENTIAL.

Like Machiavelli, Hobbes insisted that politics should be removed from religious belief. People always believe in their own interpretation of the Bible, for instance, and are prompted to act from religious conscience. This inevitably leads to extremism and bloody civil war.

Hobbes was profoundly impressed by geometrical knowledge and how it can be built up deductively from a few elementary axioms. If it worked for mathematics, why not for politics? He began with a completely materialist “science of man”.

I HAD BEEN IMPRESSED BY THE PHYSICIST GALILEO’S “PRINCIPLE OF INERTIA”… THIS STATES THAT WHEN A BODY IS IN MOTION, IT MOVES FOR EVER. SO EVERYTHING THAT EXISTS, INCLUDING HUMAN BEINGS, IS ULTIMATELY BASED ON “MOVING MATTER”.

Human beings are endlessly restless and unstable creatures, pushed in all directions by their appetites and aversions.

Motives and beliefs are the end results of a series of colliding desires and aversions moving around in the mind like restless billiard balls. Human beings are also “rational” in the sense of planning how to satisfy their appetites and think how best to protect themselves from danger. Hobbesian human beings are involuntary “psychological egoists” – utterly selfish creatures programmed to be interested only in their own survival and prosperity.

AND WE ALL KNOW THIS TO BE TRUE … WHEN A MAN SLEEPS, HE LOCKS HIS DOORS. DOES HE NOT THERE AS MUCH ACCUSE MANKIND BY HIS ACTIONS AS I DO BY MY WORDS?

Whenever selfish individuals aggregate, in a pre-social “State of Nature”, each one tries to satisfy their own appetite for wealth, friends and reputation, in competition with others. Each individual is also roughly equal in terms of physical strength and intellect. But goods are scarce and violence endemic.

EVERY INDIVIDUAL IS RATIONAL ENOUGH TO REALIZE THAT THE BEST FORM OF DEFENCE IS USUALLY PRE-EMPTIVE ATTACK. THE END RESULT IS HORRIFIC, FOR EVERYONE… NO ARTS; NO LETTERS; NO SOCIETY; AND WHICH IS WORSE OF ALL, CONTINUAL FEAR, AND DANGER OF VIOLENT DEATH; AND THE LIFE OF MAN, SOLITARY, POOR, NASTY, BRUTISH AND SHORT.

Hobbes’s State of Nature is defined by the lack of all those things that society provides.

It is a nightmare of violence and insecurity that no one desires but which is the inevitable consequence of each aggressive individual attempting to survive by attacking first.

INDIVIDUALS WILL ACT QUITE RATIONALLY IN ORDER TO PRODUCE A SITUATION THAT NONE OF THEM WANT. JUST AS INDIVIDUAL FISHERMEN ACT INDEPENDENTLY AND RATIONALLY TO DEPLETE THE OCEANS AND SO DESTROY THEIR LIVELIHOOD.

Political philosophers sometimes call this kind of unwanted end result “The Prisoners’ Dilemma” (where it seems quite rational for two prisoners to betray each other, even though the outcome is worse for both of them).

If you accept Hobbes’s initial premise about human psychology, then his conclusion is logical. The vicious State of Nature is the chaotic and violent abyss we fall into when there is no sovereign power to impose order.

INNATE HUMAN SOCIABILITY IS A MYTH. SOCIETY IS A STATE OF EXISTENCE THAT HAS TO BE ARTIFICIALLY CREATED. BUT ALL INDIVIDUALS FEAR THEIR OWN PREMATURE DEATH AND WILL SEEK WAYS TO AVOID IT.

We can look rationally into the future and see how our personal survival can be assured by agreeing with each other to follow “laws of nature” necessary for self-preservation. Hobbes agrees with St Aquinas that there are “natural laws” – notably the right of every individual to preserve his or her own life, together with a corresponding duty not to injure others.

There must also be some form of coercive power to punish those who break this “social contract” to their own advantage. “Covenants, without the Sword, are but Words, and of no strength to secure a man at all.”

THIS IS HOW IT HAPPENS THAT ISOLATED STRANGERS CAN BECOME SOCIAL BEINGS BY “COVENANT” – AN ENFORCEABLE CONTRACT TO WHICH ALL AGREE. HUMAN SOCIETY IS NOT “NATURAL” BUT CONSTRUCTED. HUMAN BEINGS ONLY EVER BECOME “SOCIAL” BY AGREEMENT, UNLIKE THE INSTINCTIVE COMMUNITIES OF BEES AND ANTS.

Individuals have to give up their right to govern themselves. A sovereign power is then “authorized” to act for this society of egoistic individuals as a kind of legal fiction which somehow “represents” them all and has absolute power over everybody. This prevents any further conflict. Obedience means protection.

The subjects of the sovereign power are “obliged” to obey because they will be forced to do so. Individuals only have the freedom that the sovereign allows them. The sovereign himself does not enter into any kind of contract. If he did so, this would mean that some individuals might question his authority, and so provoke civil war and the return to a “State of Nature”.

INDIVIDUALS CAN ONLY EVER REBEL IF THE SOVEREIGN DELIBERATELY SETS OUT TO KILL OR INJURE THEM, AND SO BREAKS THE PRIMARY “NATURAL RIGHT” OF SELF-PRESERVATION FROM WHICH ALL OTHERS ARE DERIVED. HOW A SOVEREIGN COULD EVER CONSCRIPT AN ARMY IS THEREFORE NOT EXACTLY CLEAR.

Hobbes begins with free individuals and concludes with sovereignty, which has to be absolute if individuals are to avoid the ever-present threat of political chaos. This absolute sovereign power should be given to a single monarch, because this minimizes the sorts of divisions and corruption that plague all other forms of government.

HOBBES RELUCTANTLY SUGGESTS THAT “NATURAL LAW” ALSO PLACES A FEW LIMITATIONS ON THE TOTAL AUTHORITY OF ABSOLUTE MONARCHS. THEY SHOULD APPLY THE LAW UNIVERSALLY AND IMPARTIALLY AND PUNISH INDIVIDUALS ONLY WHEN THERE IS GOOD CAUSE.

But any restrictions on the sovereign’s power never become individual citizens’ “rights”, because these have now all been transferred to the sovereign. (Although how individual rights can be “transferred” or “renounced” isn’t always clear, or even necessary.)

Hobbes’s account of human nature, contractual “consent” and political authority has been extraordinarily influential. Contemporary critics were horrified by his cynical definition of human beings and a political philosophy that denied the State any divine sanction. They also saw that there was something “circular” about Hobbes’s social contract.

CONTRACTS ARE MADE BINDING ONLY AFTER THE FIRST ONE IS AGREED UPON. SO HOW CAN THE FIRST ONE BE MADE COMPULSORY?

Those who obeyed the contract before the sovereign power was authorized to enforce it would quickly become prey to those who didn’t. Hobbes’s solution is to make the whole process a kind of instantaneous gamble, made by all parties simultaneously.

Many critics also think that Hobbesian people are strangely atomistic, “ready-made” creatures with no inbuilt sociability. Advocates of “psychological egoism” like Hobbes have great difficulty in trying to redefine words like “generosity” and “altruism” and explain why it is that human beings still regularly approve of such kinds of behaviour.

THE EXISTENCE OF MORAL VOCABULARY IS INEXPLICABLE IF HOBBES’S ACCOUNT OF HUMAN NATURE IS TRUE, BUT QUITE UNDERSTANDABLE IF IT ISN’T. IT SEEMS TO BE MORE MALLEABLE AND SOCIAL THAN HE EVER ALLOWS IT TO BE. “HUMAN NATURE” MAY NOT BE AS FIXED AND DETERMINED AS HOBBES INSISTS.

Hobbes cannot allow his egoists to be motivated by anything other than selfishness, because then his “State of Nature” might be something rather less threatening and invalidate the need for absolute sovereignty. Hobbes shows little interest in some sort of intermediate “civil society”. His individuals jump from selfish isolationism into a fully formed authoritarian political state.

The political philosophy of John Locke (1632–1704) probably had more practical influence on historical events and political systems than anything Hobbes wrote. Locke’s patron was the famous Earl of Shaftesbury, the principal founder of the Whig party in English politics. Shaftesbury believed in religious toleration and was critical of all forms of absolutism. In 1683 both men had to flee to Rotterdam when Shaftesbury lost his political influence, but they returned in 1688 – the year of “The Glorious Revolution”, which replaced the Catholic monarch James II with the Protestant William of Orange.

IT ALWAYS SEEMS EAGER TO BURN DISSENTERS WHENEVER IT HAS THE POWER TO DO SO. AFTER THAT, I WAS ALWAYS SUSPICIOUS OF ROMAN CATHOLICISM, WHICH DEMANDS LOYALTY TO THE POPE ABOVE LOYALTY TO THE CONSTITUTION.

In the late 1670s, Locke wrote his famous Two Treatises of Government in secret and refused to acknowledge it as his own work for many years.

Like Hobbes, Locke begins with individuals in a “State of Nature”. But Locke’s individuals are less psychologically determined or detached. Locke argues that even in this primitive situation, everyone can distinguish between right and wrong.

AN AMERICAN SAVAGE WHO MAKES A PROMISE TO A SWISS GENTLEMAN IN THE BACKWOODS KNOWS THAT PROMISES ARE BINDING. EVERY INDIVIDUAL IS WELL AWARE OF THE “LAWS OF NATURE”, AND OBEDIENCE TO THESE LAWS ENSURES THAT MOST MEN DO NOT HARM THE LIVES, HEALTH, LIBERTY OR PROPERTY OF OTHERS.

Locke’s pre-political “community” is essentially a benign version of his own 17th-century society, minus government. It seems quite attractive, but Locke believed that it could only ever be a temporary state of affairs.

Locke is more of a traditionalist than Hobbes. He is wisely vague about the origins of “Natural Laws” but insists that they are compulsory because they are God-ordained (which makes God rather like Hobbes’s absolute monarch). Natural Laws are also “rational”, which makes them universal and absolute.

I THOUGHT I COULD EVENTUALLY PRODUCE A WHOLE MORAL SYSTEM OF “DEDUCTIVE ETHICS” BASED ON “SELF-EVIDENT” NATURAL LAWS FROM SUCH PREMISES AS, “WHERE THERE IS NO PROPERTY, THERE CAN BE NO INJUSTICE.” AND THIS CONCEPT OF “PROPERTY” IS THE KEY TO ALL OF LOCKE’S POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY.

According to Locke, in the original State of Nature, God gave the Earth to all men. He also gave everyone reason, so that everyone can utilize the world’s resources to their best advantage. Everyone owns their own body, so, by mixing the body’s labour with nature, individuals acquire property rights over certain bits of land and thereby remove it from the common store.

SERVANTS CAN ALSO SELL LABOUR TO THEIR MASTERS… THIS RESULTS IN ONE MAN OWNING MORE THAN HIS OWN LABOUR CAN EVER ACHIEVE. A PROCESS ACCELERATED BY THE INVENTION OF MONEY. THIS IS THE FUNDAMENTAL WAY IN WHICH GOD REWARDS THE INDUSTRIOUS AND SANCTIONS SOCIAL INEQUALITY.

The Right of Inequality LOCKE NEVER QUESTIONED SOCIAL INEQUALITY. IT IS PLAIN THAT THE CONSENT OF MEN HAS AGREED TO A DISPROPORTIONATE AND UNEQUAL POSSESSION OF THE EARTH. IT’S HARD TO SEE HOW “MIXING” YOUR LABOUR WITH THE LAND GIVES YOU EXCLUSIVE RIGHTS OVER IT.

But what Locke wants to emphasize is that the institution of property existed long before any kind of society or political State came into being. Property ownership gives individuals inviolable rights and freedom from State interference.

But even this rather sophisticated State of Nature (that already allows for landed gentry and servant classes) is “inconvenient”. A few degenerate individuals will always exist to rob and murder innocent individuals.

IF A MAN KILLS ANOTHER, THEN SOME WILL INSIST THAT “NATURAL LAW” SANCTIONS THE RIGHT OF THE VICTIM’S BROTHER TO SEEK REVENGE. BUT WHEN EVERY INDIVIDUAL IS THE JUDGE OF HIS OWN CAUSE, THIS LEADS TO ENDLESS VENDETTAS. EVERY MAN WILL INTERPRET NATURAL LAW DIFFERENTLY, AND SOME MAY EVEN RESORT TO “PRE-EMPTIVE” ACTS OF VIOLENCE THAT HOBBES DESCRIBED.

The solution is to convert the ambiguous diktats of natural law into clearer and enforceable positive law. And this is why individuals first agree to form a contractual “society”, but not a State. Society is therefore rather like a joint-stock company that prosperous individuals enter into freely, for reciprocal advantage.

ONCE YOU JOIN IT, HOWEVER, YOU, AND YOUR DESCENDANTS, CAN NEVER LEAVE. THE POWER THAT EVERY INDIVIDUAL GIVES TO THE SOCIETY WHEN HE ENTERS INTO IT CAN NEVER REVERT TO THE INDIVIDUAL AGAIN. LOCKE’S SOCIAL CONTRACT IS TOTALLY BINDING.

Locke’s political philosophy is partly a dialogue with Sir Robert Filmer’s Patriarcha – a text first published in 1679 which claimed that all sovereigns were sacred persons, divinely appointed, and therefore like fathers given a “natural” authority over their large “family”.

KINGS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN RATHER FOND OF THE IDEA OF “DIVINE RIGHT”, WHICH ASSUMES THAT THE RELATIONSHIP OF THE SOVEREIGN TO THE STATE IS LIKE THAT OF LANDOWNERSHIP. KINGS ARE JUSTLY CALLED GODS, FOR THAT THEY EXERCISE A RESEMBLANCE OF DIVINE POWER UPON EARTH.

But such absolutist views seem impossible to prove, do not explain how it is that successful usurpers inherit divine authority, and, most worryingly, give limitless power to one individual and define all others as “subjects” with no property rights of their own.

Locke’s individuals have already made themselves social and do not need an absolute monarch to keep order. All they require is some neutral authority to settle disputes and ensure that criminals are punished “indifferently”.

THE CHIEF END OF MEN PUTTING THEMSELVES UNDER GOVERNMENTS IS THE PRESERVATION OF THEIR PROPERTY. SO SOCIETY CREATES GOVERNMENTS. LOCKE’S CONCLUSION IS THAT IT CAN THEREFORE REMOVE THEM IF IT WISHES.

In a political society, Locke’s individuals do not have to give up their rights to life, liberty and property just because a person or institution has been appointed to make law and enforce it. Government is more of a “trustee” than a party to a contract – so it has obligations but no rights. There are also strict limitations placed on government power which depends totally upon the consent of citizens.

OTHERWISE THERE WOULD BE NO POINT IN ANYONE LEAVING EITHER A MILDLY IMPERFECT STATE OF NATURE OR A CONTRACTUAL SOCIETY FOR SOMETHING MUCH WORSE. YOU’D BE FLEEING FROM POLECATS AND FOXES, ONLY TO FIND YOURSELF ATTACKED BY LIONS.

So Hobbes uses his State of Nature to show why an absolute sovereignty is necessary; Locke employs his to prove that governments must only ever have limited powers.

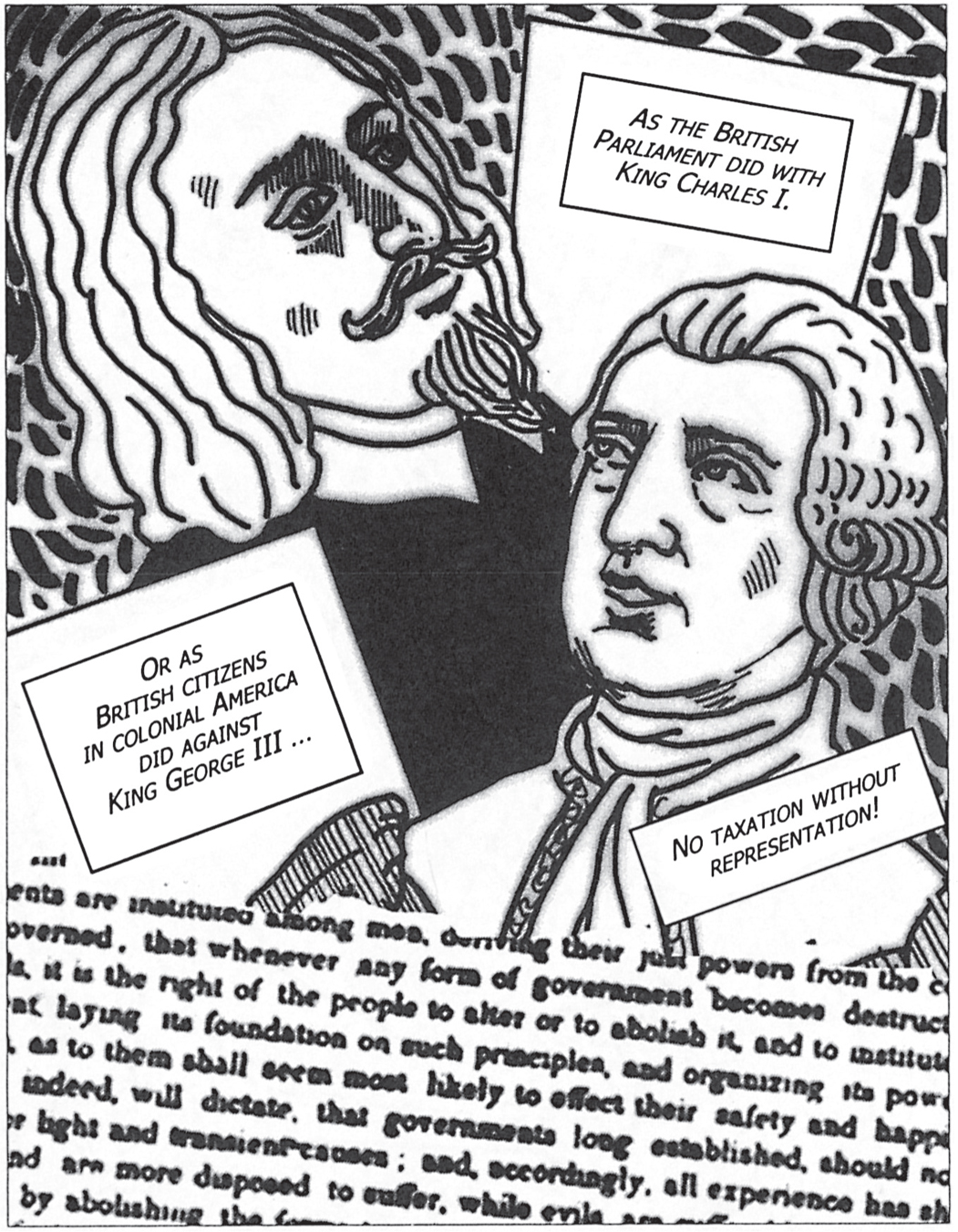

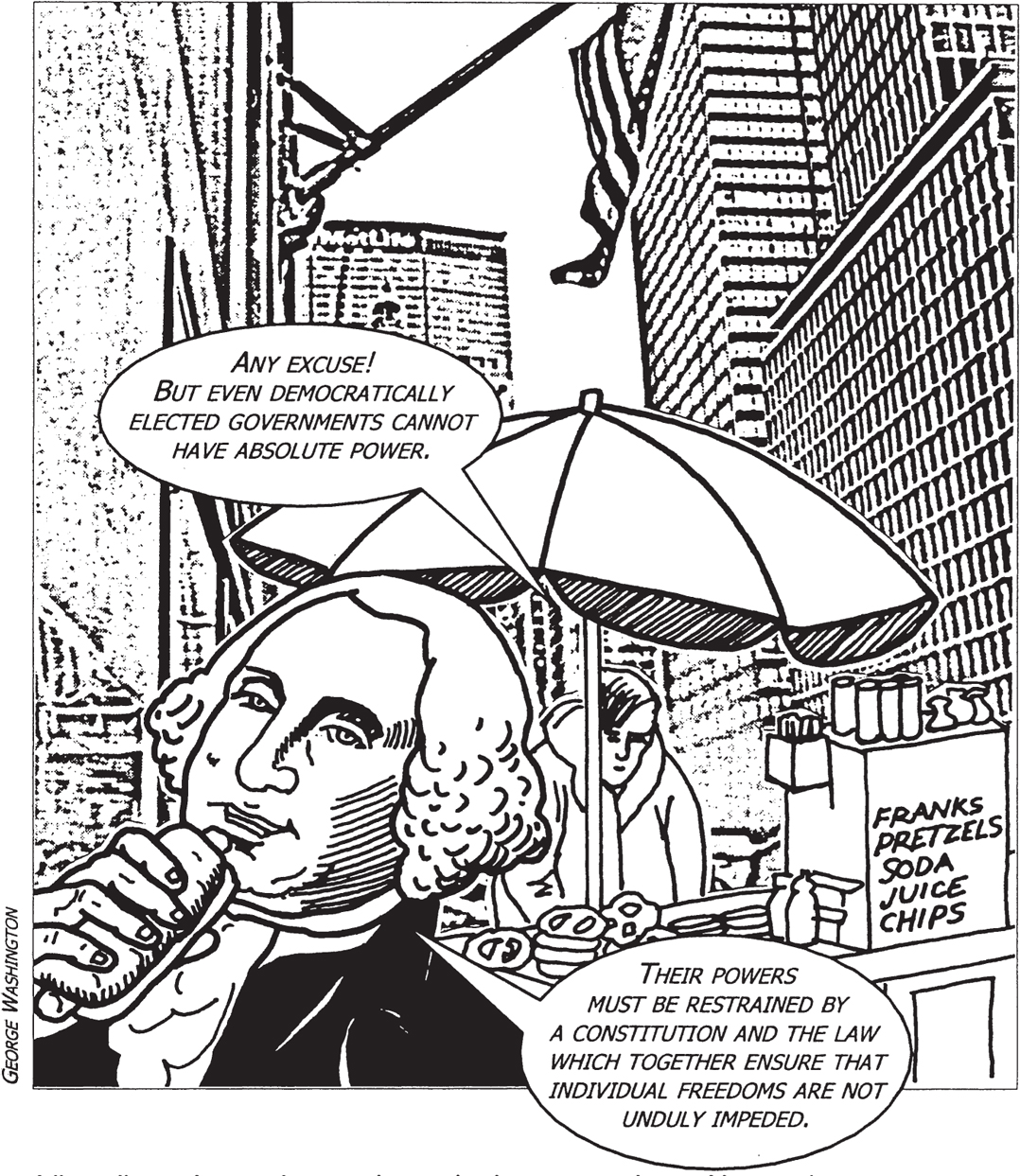

A political society that has neutral judges, a legal framework and an executive with limited powers should be predictable, stable and peaceful. Governments are entrusted with power, but citizens always have the right to remove them if they abuse it – if, for example, they raise taxes against property without consent. If the executive ever becomes tyrannical, then the people may remove it by force.

Locke considered that a government or monarch would have to be completely oppressive (not just corrupt or mediocre) for this to be a legitimate act. A despotic ruler is best imagined as a “rebel” against political society. An uprising against his authority is merely a way of restoring the political status quo.

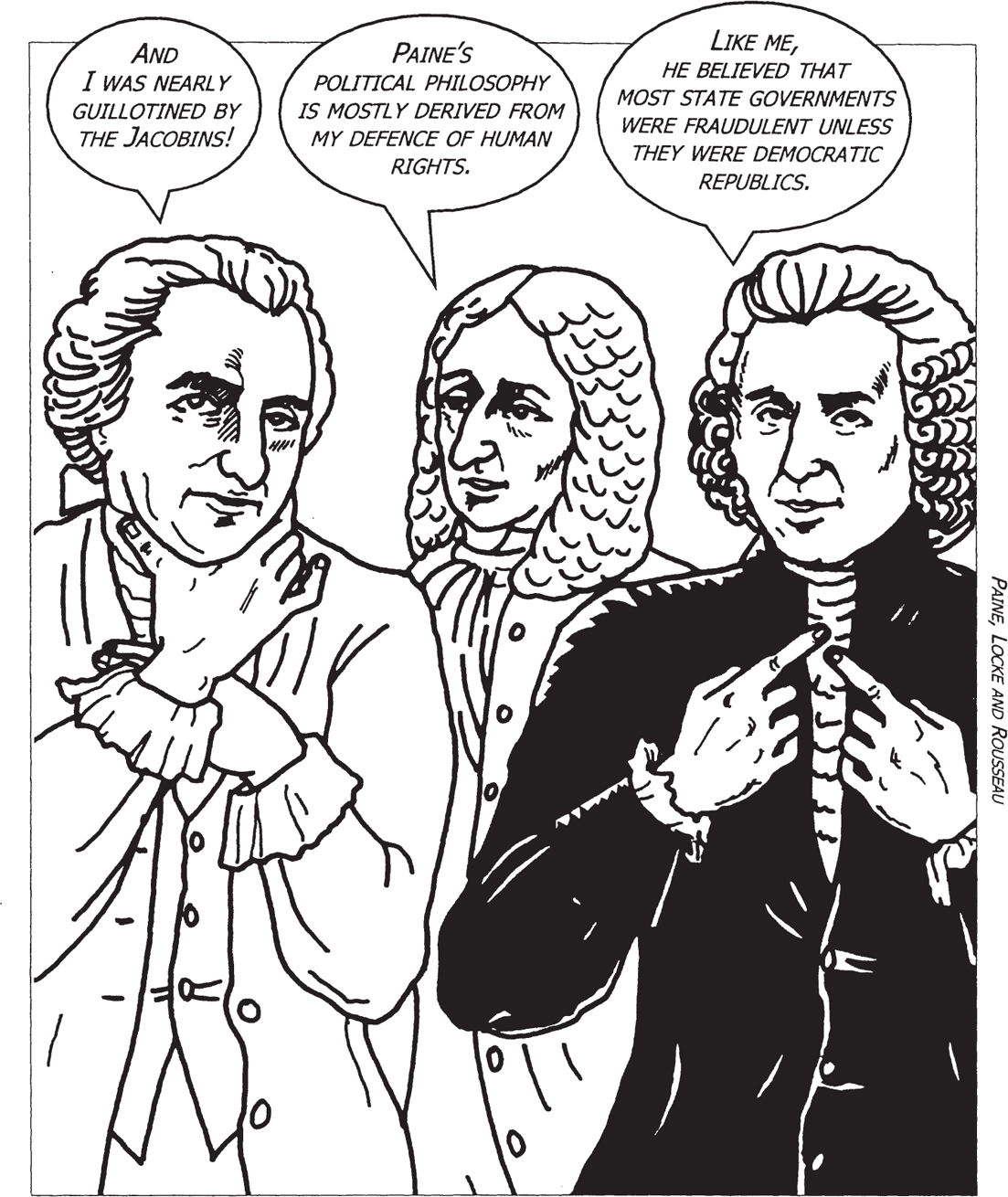

THE GOVERNMENT MAY BE OVERTHROWN, BUT THE POLITICAL REGIME ITSELF CARRIES ON. LOCKE WAS NO REVOLUTIONARY, IN SPITE OF THE INFLUENCE HIS WRITINGS HAD ON FUTURE RADICALS LIKE MYSELF IN DEFENDING THE AMERICAN COLONISTS.

Locke argued that power should be separated, so that no one political institution has a monopoly. The Legislative body makes the laws after due debate and discussion. The Executive then carries them out. Locke assumes that the Judiciary is part of the Executive.

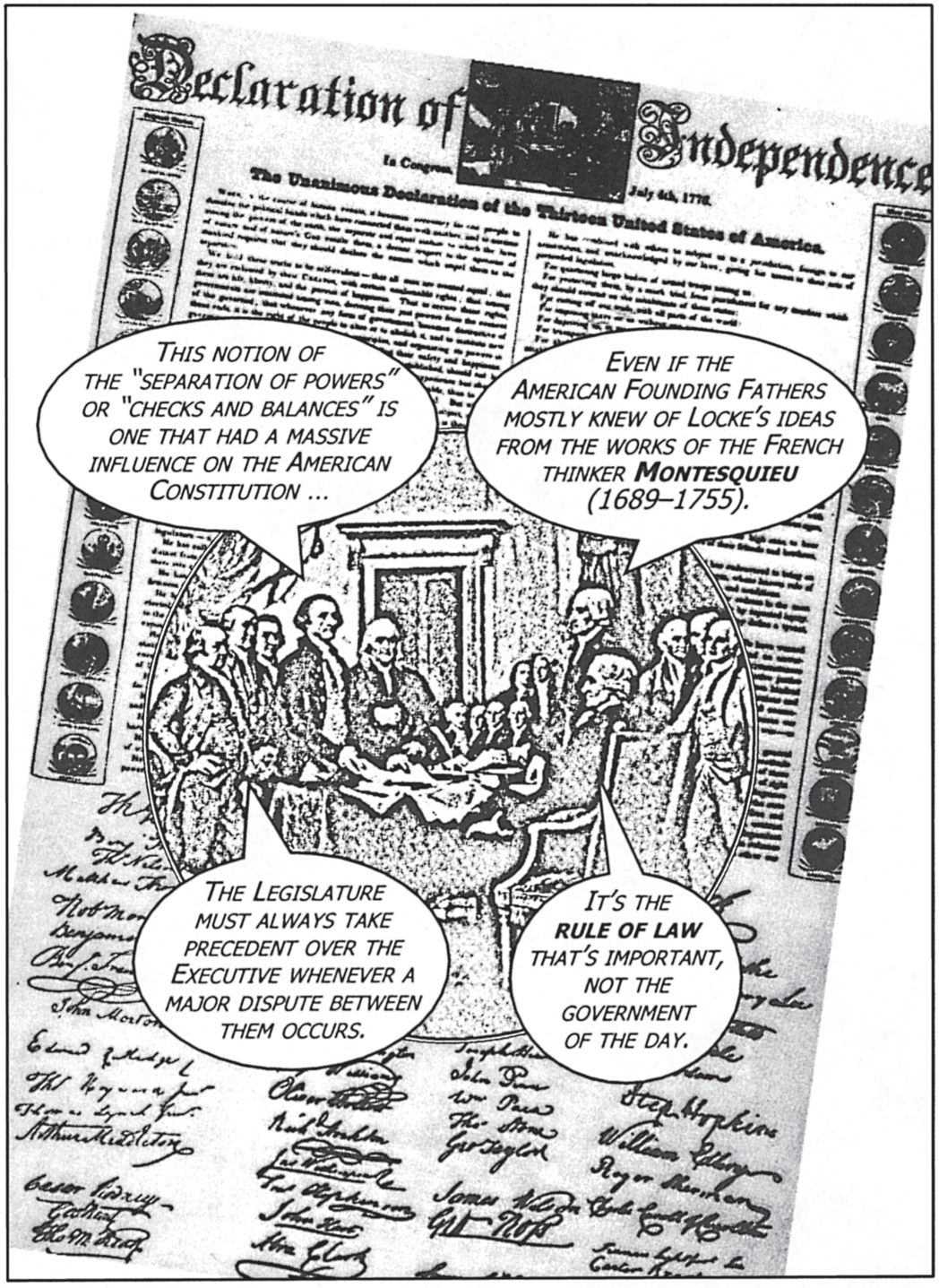

THIS NOTION OF THE “SEPARATION OF POWERS” OR “CHECKS AND BALANCES” IS ONE THAT HAD A MASSIVE INFLUENCE ON THE AMERICAN CONSTITUTION … EVEN IF THE AMERICAN FOUNDING FATHERS MOSTLY KNEW OF LOCKE’S IDEAS FROM THE WORKS OF THE FRENCH THINKER MONTESQUIEU (1689–1755). IT’S THE RULE OF LAW THAT’S IMPORTANT, NOT THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DAY. THE LEGISLATURE MUST ALWAYS TAKE PRECEDENT OVER THE EXECUTIVE WHENEVER A MAJOR DISPUTE BETWEEN THEM OCCURS.

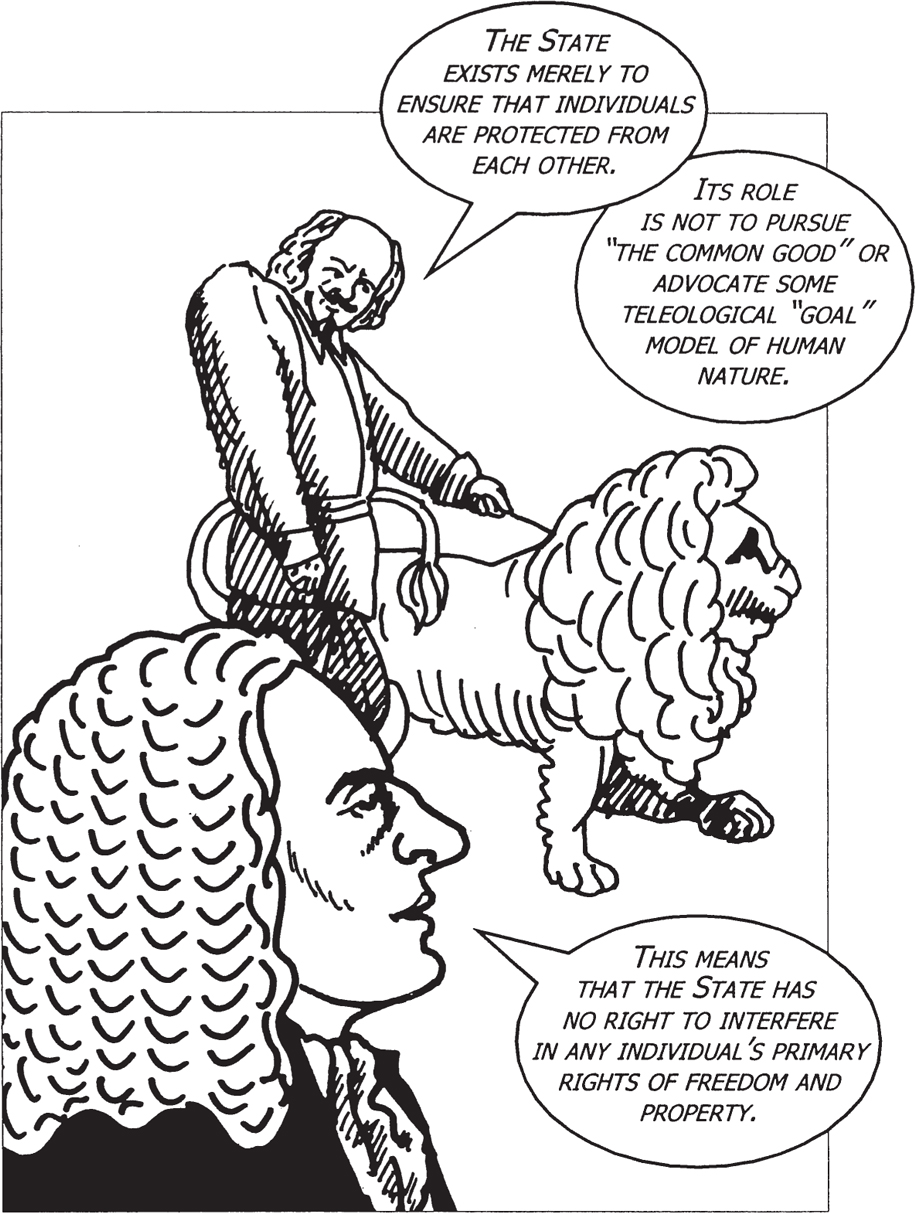

The role of Locke’s government is minimal. The state exists primarily to ensure that there are systematic rules governing the transference of property – and not to redistribute wealth or maintain public welfare.

ONLY THOSE WHO INHERIT PROPERTY SHOULD HAVE THE VOTE BECAUSE THEY ARE EXPRESSING CONSENT TO A REGIME WHOSE PRIMARY FUNCTION is TO PROTECT PROPERTY. THE POOR ARE TOO BUSY WITH THE TASK OF SURVIVING TO EDUCATE THEMSELVES SUFFICIENTLY TO THINK ABOUT POLITICAL MATTERS. SO WE ARE NOT ENFRANCHISED.

Locke realized that the idea of everyone “consenting” to be ruled by governments was problematic. He agrees that the “consent” of most people is merely “tacit” – citizens are deemed to have agreed to obey the State because they do not emigrate, or because they benefit from all that it provides.

BUT IT IS HARD TO SEE HOW TACIT CONSENT IS MUCH DIFFERENT TO RESIGNATION, SUBSERVIENCE OR INDIFFERENCE. AND IN A MODERN SOCIETY OF MASS MEDIA, CONSENT CAN SOON BE MANUFACTURED. TRUE CONSENT PROBABLY INVOLVES FREE PUBLIC DEBATE AND SOME ELEMENT OF CHOICE.

In reality, a political system that was truly serious about “consent” would soon become a patchwork quilt of secessionist states. There are also no political states that have ever been founded by hypothetical “contracts”, as the Scottish philosopher David Hume (1711–76) pointed out. “If you were to ask most people whether they had ever consented to the authority of their rulers, they would be inclined to think very strangely of you and would reply that the affair depended not on their consent but that they were born to such obedience.”

NEVERTHELESS, TO BE A CITIZEN SUBJECTED TO LAW DOES NOT MEAN BEING COERCED BY AN ABSOLUTE MONARCH.

Citizens must consent to be ruled, and this means continuously and not just at the moment when political society comes into being. There must always be a large area of personal freedom left to each individual and well-defined limits to State power.

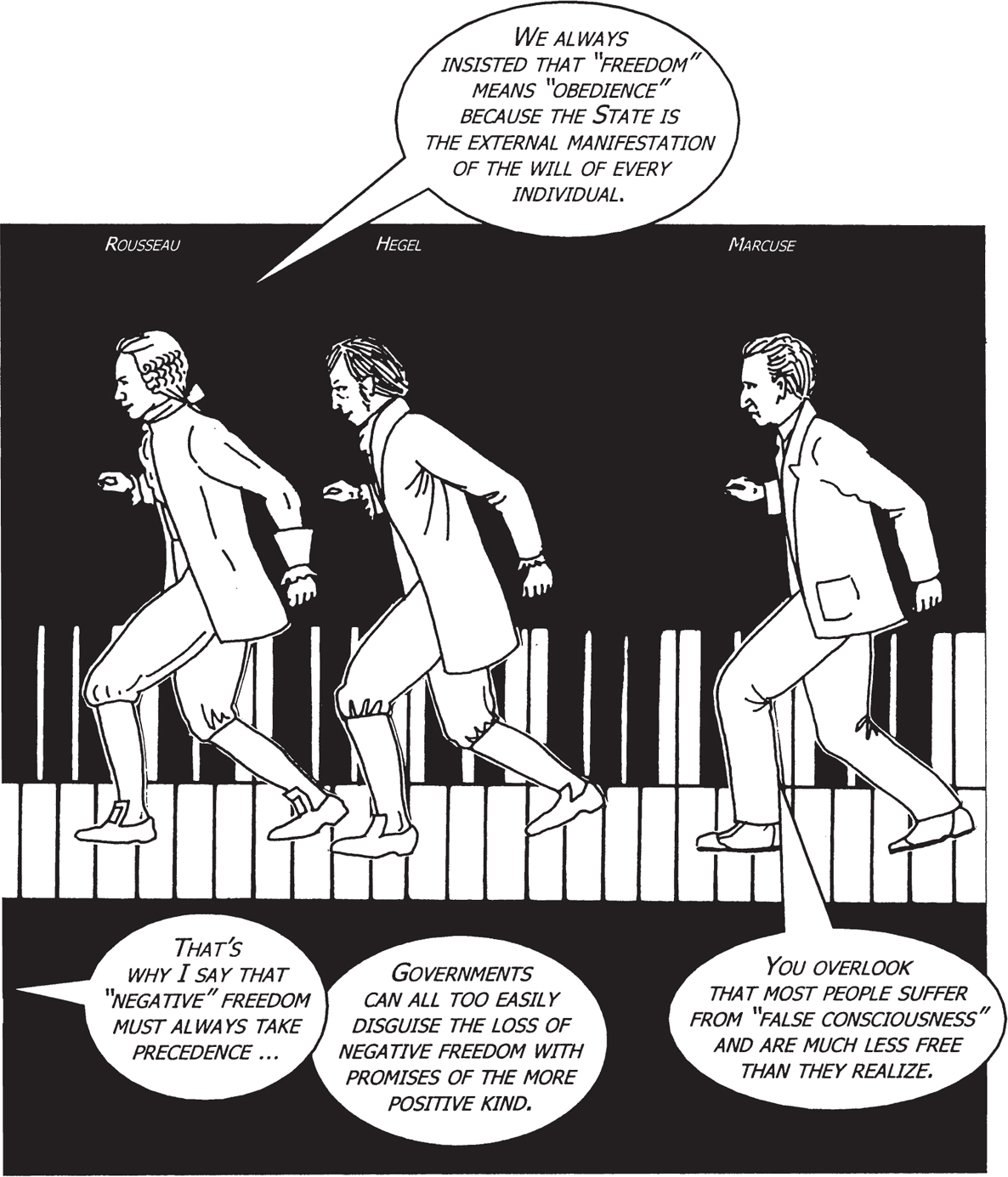

The political philosophy of Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) often follows that of Hobbes and Locke in textbooks on political philosophy.

LIKE THEM I BEGIN WITH A HYPOTHETICAL “STATE OF NATURE”, FOLLOWED BY A CONTRACTUAL EXPLANATION OF CONSENT AND OBLIGATION, AND THE INEVITABLE CONCLUSIONS ABOUT THE NECESSITY OF A STATE. BUT THERE THE SIMILARITIES END…

Rousseau was born in the protestant Republic of Geneva, ruled by legislative and administrative assemblies, both composed of ordinary citizens. He was a self-taught scholar of political philosophy and a great admirer of the Greek City States of Athens and Sparta. In 1749, he had a sudden “vision” which made him famous throughout Europe.

I SAW THAT HUMAN BEINGS WERE NOT AS HOBBES OR LOCKE HAD DESCRIBED THEM – PERFECTLY FORMED INDIVIDUALS WITH FIXED CHARACTER TRAITS. HUMAN NATURE IS NEVER STATIC BUT EVOLVES ACCORDING TO THE SORTS OF CIVILIZATIONS THAT FORM IT.

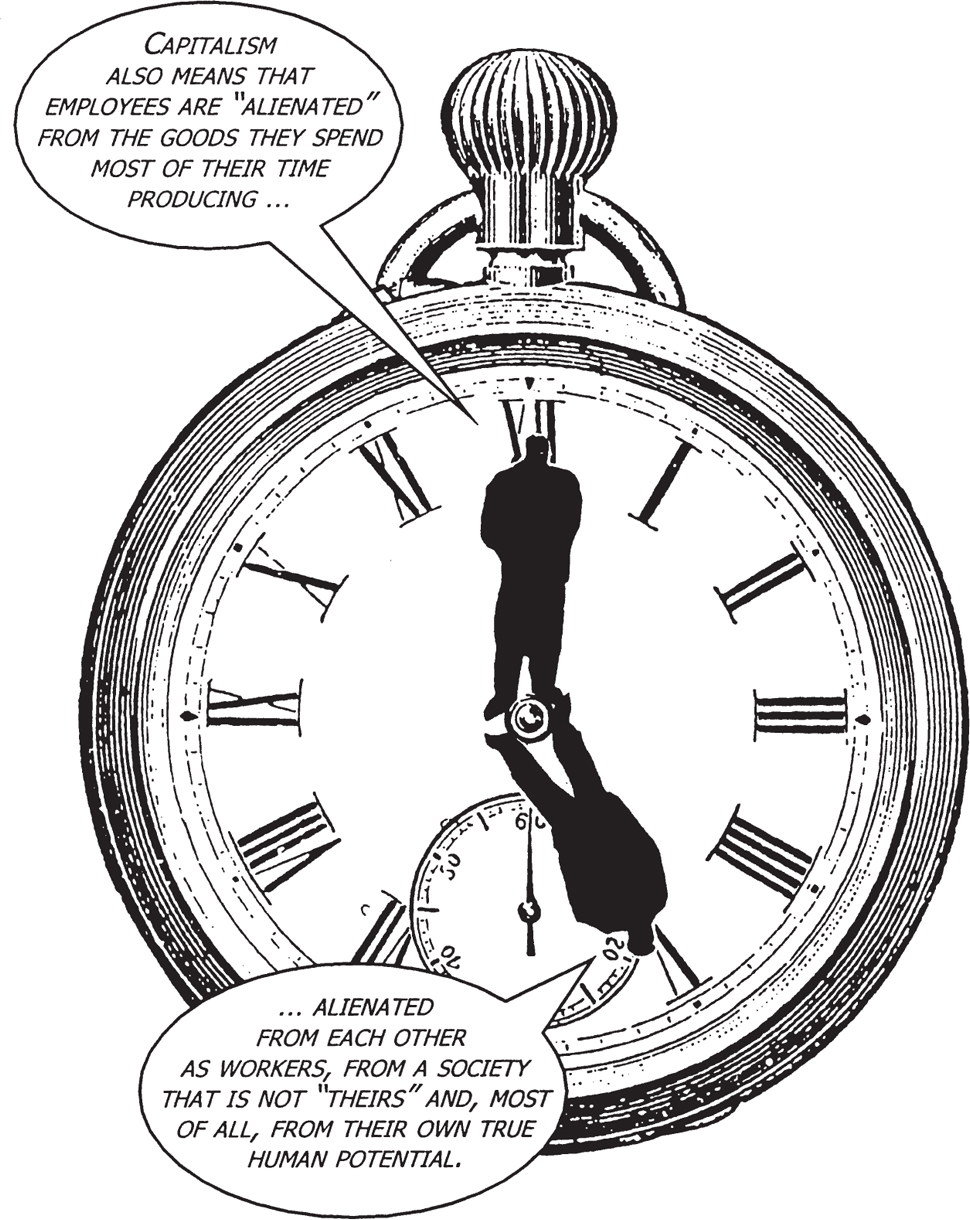

Human beings have created unjust and oppressive political States and it is these that have made individuals greedy, vicious and “Hobbesian”. Most people are alienated from the very institutions they themselves have created.

In his Second Discourse, Rousseau describes pre-social men and women living in a “State of Nature”. But this time they aren’t vicious egoists or landed gentry. Rousseau’s original humans are equally fictitious but more anthropological.

IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO “READ OFF” FROM CORRUPTED MODERN INDIVIDUALS WHAT UNCONTAMINATED PRE-SOCIAL HUMAN BEINGS WERE LIKE… ALL ONE CAN DO IS CONJECTURE.

Rousseau’s first men and women are only potential human beings – isolated, harmless primates who are utterly ignorant of “natural law”, even though they instinctively refrain from harming each other.

Then the unfortunate invention of agriculture arrives and is accompanied by the even more disastrous idea of “property” with its corresponding economic inequality. A few clever landowners quickly recognize their need for legitimate and enforceable property rights and so devise the idea of social and political contracts. Everyone who desires peace and security consents to them.

ONLY WE, THE PRIVILEGED FEW, CAN SEE THAT THE REAL PURPOSE OF “CONTRACTS” IS TO CONSTITUTE COERCIVE GOVERNMENTS WHICH SANCTION THE LOSS OF FREEDOM FOR THE MAJORITY. CIVILIZATION GETS INVENTED AND A NEW KIND OF HUMAN NATURE EMERGES, MORE SOPHISTICATED THAN BEFORE, BUT WHOLLY HYPOCRITICAL AND SELFISH.

Rousseau does not claim that there is a better “essentialist” human nature that we should all return to, but he does think that the benefits of civilization can only be achieved at the disproportionate cost of a distorted and unnatural humanity.

Rousseau’s critique of civilization at first startled and then irritated his fellow Enlightenment “Philosophes”, Voltaire (1694–1778) and Denis Diderot (1713–84). But his “primitivist” philosophy continues to influence all those who think that the price of civilization remains far too high. Fortunately, Rousseau’s vision is also more optimistic than it might appear. If human beings have both reason and free will, then it is always possible for them to change their human nature into something more altruistic and collectivist.

IN MY NOVEL EMILE, I SUGGEST THAT IT IS POSSIBLE TO EDUCATE A CHILD “NATURALLY” SO THAT HE REMAINS UNCONTAMINATED BY THE EVILS OF CIVILIZATION. BUT EVEN I MUST EVENTUALLY ABANDON MY SEALED ENVIRONMENT AND INNOCENCE, AND RETURN TO CIVILIZATION – TO BECOME A “GOOD CITIZEN”.

Emile must forsake his “natural” self – which makes his unique education seem rather pointless. What needed to change was society itself, and that’s what Rousseau’s most important political work, The Social Contract, is all about.

Rousseau realized that children must be socialized if they are ever to become truly human. Human beings function best in families, small groups and as committed citizens of the State. But societies can only come into existence if the behaviour of every individual is restrained by customs, rules and compulsory laws.

SO, SOME INDIVIDUAL OR INSTITUTION MUST HAVE THE SOVEREIGN AUTHORITY TO FRAME THESE NECESSARY LAWS AND ENFORCE THEM. THE COST OF JOINING SOCIETY IS HIGH … EVERY INDIVIDUAL HAS TO GIVE UP “NATURAL” FREEDOM AND OBEY LAWS CONTRARY TO EACH ONE’S DESIRES.

Like Hobbes and Locke before, Rousseau accepted the need to explain the moral foundations of political “consent” and “obligation”. Hobbes equated sovereignty with an absolute power, separate from the needs and desires of citizens, because the alternative is endless misery. But Rousseau insisted there is a truly moral, and not just a prudential, reason for his citizens to obey the law – because all laws are truly “theirs”.

THE LAW MUST BE MADE BY A LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY COMPOSED OF ALL CITIZENS WHO ARE THEN OBLIGED TO OBEY THEIR “OWN” LAWS AS “SUBJECTS”. THE REWARDS OF SOCIETY ARE HIGH. INDIVIDUALS ARE NO LONGER PREY TO HOSTILE AND UNPREDICTABLE FORCES OF NATURE OR RANDOM VIOLENCE.

So, paradoxically, in a political society people are more “free”. Obedience to society’s laws brings everyone more freedom.

Since Rousseau’s Legislative Assembly involves all citizens, the State must remain small – rather like ancient Athens or 18th-century Geneva.

CITIZENS MUST BE EXTREMELY CONSCIENTIOUS AND COLLECTIVIST IF THEY ARE TO EXPRESS THIS “GENERAL WILL” WHICH FRAMES ALL STATE LAWS. THE ASSEMBLY MAKES LAWS WHICH EVERYONE THINKS WILL BENEFIT SOCIETY AS A WHOLE, RATHER THAN THEMSELVES AS INDIVIDUALS.

Children are raised to be good citizens who think and behave with a collectivist spirit that soon becomes as natural to them as familial affection. The law and the State are therefore appropriate expressions of the people’s will, and this justifies the sovereignty of both.

Erring individuals who disobey the law, ultimately framed for their own benefit, would have to be reminded of their obligations to the State.

THEY MUST BE FORCED TO BE FREE.

Rousseau’s ideal Republic sounds democratic and decent but is founded on very optimistic foundations – perfect citizens expressing some mythical “General Will” for the good of society.

Unlike Locke’s landed gentlemen, Rousseau’s citizens have no individual rights. The citizens’ State has a total monopoly over all political opinion and the absolute power to enforce its will.

Rousseau’s collectivist State somehow “emerges” from an understanding between primitive individuals in a process that seems more organic than contractual, and so needs a human catalyst in the form of the “Legislator”.

THIS MYSTERIOUS BUT WISE OFFICIAL ADVISES THE FIRST LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLIES ON THOSE CONSTITUTIVE LAWS THAT ARE INEVITABLE IF A COLLECTIVIST STATE IS TO FLOURISH. I HAVE NO POLITICAL AUTHORITY AND QUIETLY DISAPPEAR WHEN NO LONGER REQUIRED.

Rousseau also recommended that his citizens all agree to a “Civic Religion”, a mild form of vague Deism which would nevertheless be compulsory because such a religion would encourage allegiance to the State.

Rousseau’s collectivist State is therefore very different from Hobbes and Locke’s associations of selfish or property-owning individuals who congregate only for pragmatic reasons of self-interest. For Rousseau, like Plato and Aristotle, politics is a branch of ethics.

THE PRIMARY ETHICAL FUNCTION OF THE STATE IS TO ENABLE HUMAN BEINGS TO FULFIL THEIR TRUE SOCIAL NATURE. PEOPLE REMAIN NON-HUMAN UNTIL THEY ARE ENROLLED AS MEMBERS OF SOMETHING GREATER THAN THEMSELVES.

This means that abstract entities like Society, the State and the General Will have a unique moral existence of their own, wholly separate from the selfish desires of individuals.

Rousseau’s strict communitarianism might appear inconsistent. It came from a man famous for his advocacy of artistic freedom who fled the religious intolerance of his own citizens’ Republic of Geneva. However, the advice he gave to the citizens of Corsica and Poland showed that he wasn’t a rigid ideologue.

I HAVE NO FERVENT OBJECTIONS TO SOME PROPERTY OWNERSHIP AND I RESPECT LOCAL TRADITIONS, PROVIDED THAT THE ORIGINAL POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS ARE SMALL ENOUGH FOR ALL CITIZENS TO PARTICIPATE DIRECTLY IN PUBLIC LIFE.

As a lifelong stateless outsider, Rousseau fantasized about a life spent in a small community of like-minded companions. He never completely abandoned his admiration for the Geneva of his childhood.

Rousseau’s theoretical citizens’ State is potentially totalitarian. Recent history seems to show that creating ideal citizens is impossible and probably undesirable. State education in “citizenship” can easily descend into indoctrination. For most ordinary people, loyalty to their oppressive collectivist State is only ever simulated – out of a need for self-preservation.

IF EVERYONE SURRENDERS THEIR INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS TO THE STATE, THEN THE STATE BECOMES FAR TOO POWERFUL. IF “FREEDOM” IS A GIFT ALLOTTED TO INDIVIDUALS, IT CEASES TO BE A PRIVATE RIGHT AND BECOMES INDISTINGUISHABLE FROM “OBEDIENCE”. ROUSSEAU’S VISION OF A COLLECTIVIST HUMAN NATURE SEEMS UNREAL AND SUFFOCATING – LITTLE BETTER THAN THE SELFISH INDIVIDUALISM IT IS SUPPOSED TO REPLACE.

Rousseau’s State has no constitutional checks on its absolute power and fails to recognize individual privacy. His citizens might easily become alienated from the political institutions they themselves have made, a frequent feature of political life that seems inevitable, however hard you try to avoid it.

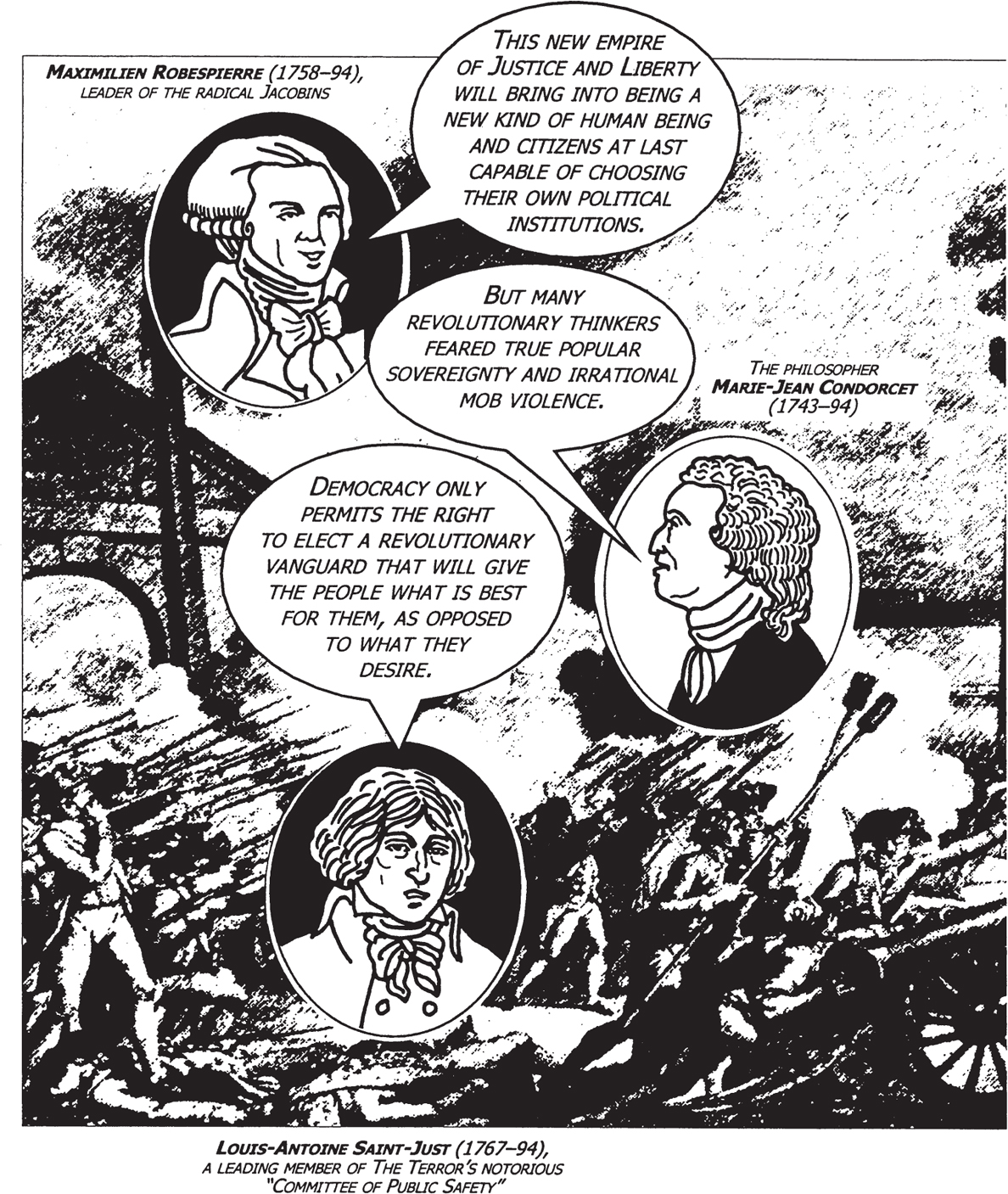

The French Revolution began in 1789 with a demand for a more constitutional monarchical government. It ended with the abolition of the monarchy and hereditary aristocracy, the erosion of most formal class distinctions, and the chaotic violence and guillotine of “The Terror”. There was now a nation of “equal citizens” with no place for the aristocracy or clergy.

THIS NEW EMPIRE OF JUSTICE AND LIBERTY WILL BRING INTO BEING A NEW KIND OF HUMAN BEING AND CITIZENS AT LAST CAPABLE OF CHOOSING THEIR OWN POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS, BUT MANY REVOLUTIONARY THINKERS FEARED TRUE POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY AND IRRATIONAL MOB VIOLENCE. DEMOCRACY ONLY PERMITS THE RIGHT TO ELECT A REVOLUTIONARY VANGUARD THAT WILL GIVE THE PEOPLE WHAT IS BEST FOR THEM, AS OPPOSED TO WHAT THEY DESIRE.

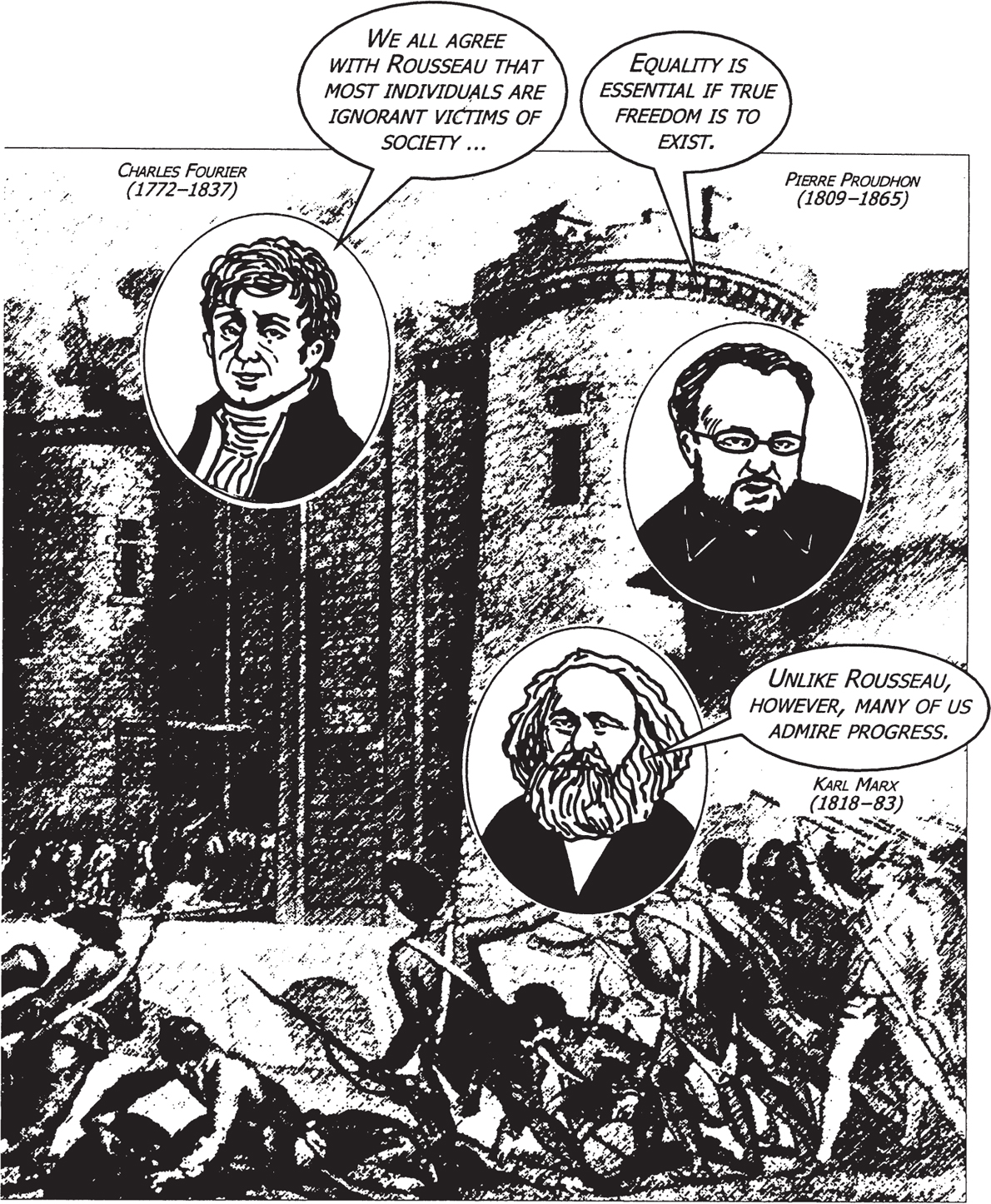

The Revolution posed new theoretical and practical political problems for which there were no easy or obvious answers. It also gave birth to those early socialists and anarchists, sometimes called “Rousseau’s grandchildren”.

EQUALITY IS ESSENTIAL IF TRUE FREEDOM IS TO EXIST. WE ALL AGREE WITH ROUSSEAU THAT MOST INDIVIDUALS ARE IGNORANT VICTIMS OF SOCIETY… UNLIKE ROUSSEAU, HOWEVER, MANY OF US ADMIRE PROGRESS.

They had lived through a time of immense revolutionary upheaval and saw how it was possible to change society for ever.

Claude-Henri Saint-Simon (1760–1825) (the “father of French Socialism”) was convinced that the rigorous application of philosophy and science could solve most social and political problems. By studying the past, one could understand its patterns of evolutionary change – from “organic” feudal states, based on religious superstition, to new secular kinds of “critical” industrial societies ruled by élites of scientists, engineers, and industrialists.

I RECOGNIZED THE IMPORTANCE OF CLASS CONFLICT AS A MAJOR CAUSE OF SOCIAL CHANGE – A MAJOR INFLUENCE ON KARL MARX … THAT’S THE REASON WHY MOST PEOPLE EVER GET TO HEAR OF HIM!

Saint-Simon’s socialist vision is of a highly rational and supremely efficient society – a centralized meritocratic beehive guided by technocrats and administrators, and made up of different workers labouring in perfect harmony and solidarity. France would become a vast workshop run by managers, but this time the immense productive potential of science and industry would benefit not just a few entrepreneurs but all the impoverished “industrious classes” that actually create society’s wealth.

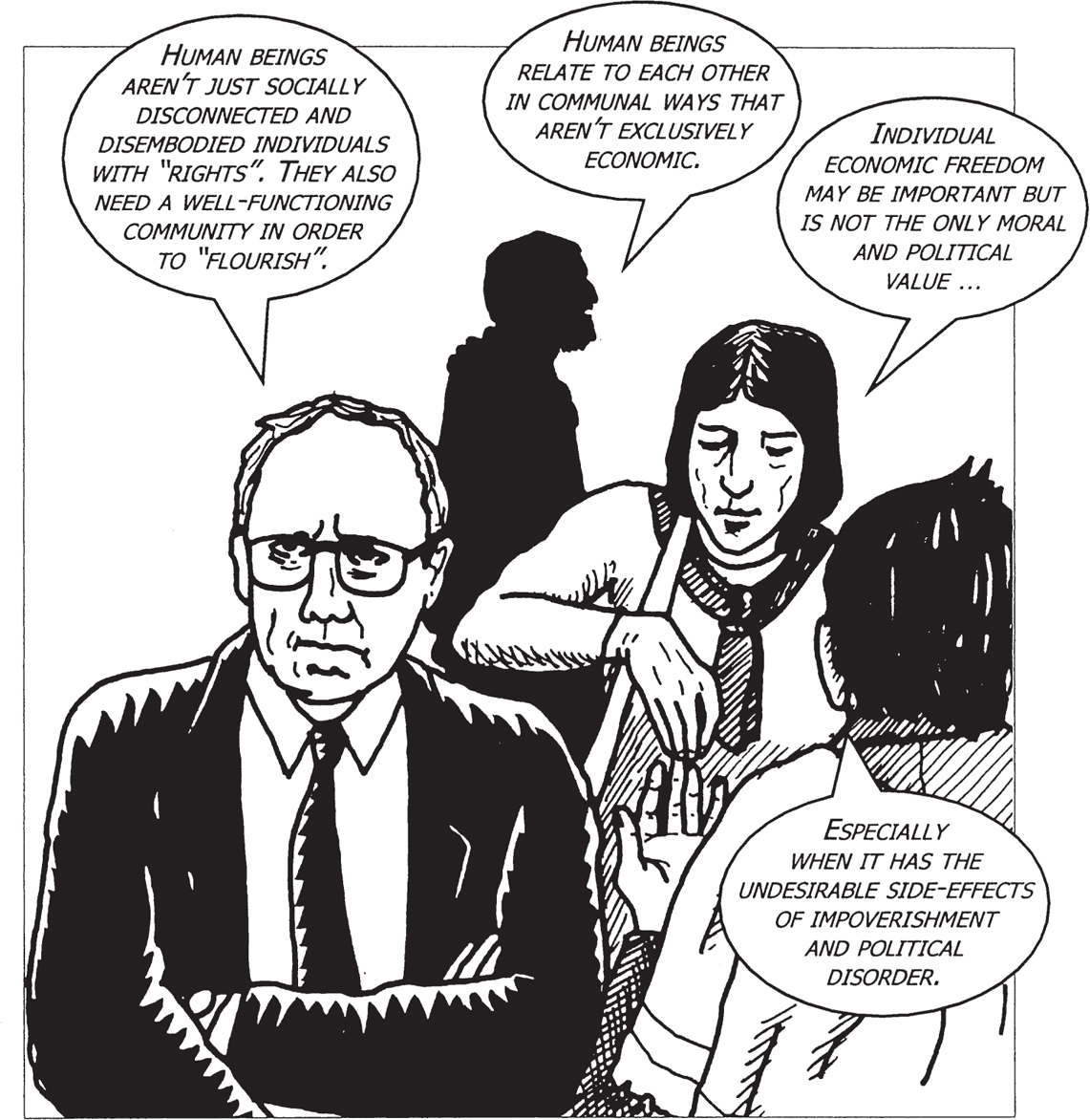

Like all ideologies, socialism comprises arguments, beliefs and ideas about the “true nature” of human beings and the kind of society that best fulfils their needs and desires. It arose in response to industrial capitalism which began to flourish in Europe at the end of the 18th century. Most socialists agree that capitalist societies are deliberately organized so that a small privileged class is always able to exploit the rest. It is only when the working class gains political power that this abuse will end. Individuals have to learn how and why they are oppressed, in order to change the way things are. One obvious remedy against inequality and poverty is to ensure that the various means of producing wealth (land, machinery and factories) are communally owned. But socialists do not agree about what sorts of “communities” should do the owning.

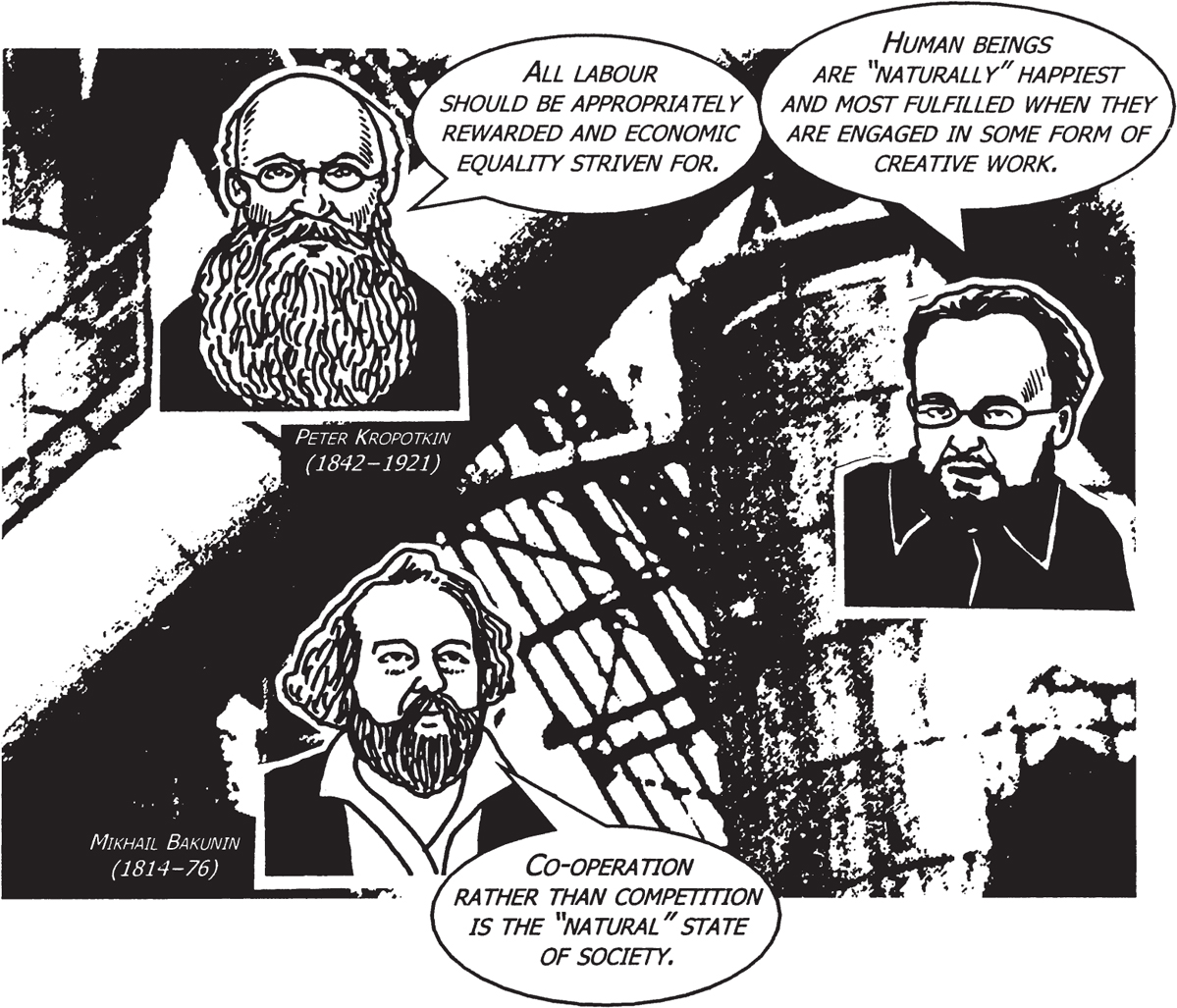

ALL LABOUR SHOULD BE APPROPRIATELY REWARDED AND ECONOMIC EQUALITY STRIVEN FOR. HUMAN BEINGS ARE “NATURALLY” HAPPIEST AND MOST FULFILLED WHEN THEY ARE ENGAGED IN SOME FORM OF CREATIVE WORK. CO-OPERATION RATHER THAN COMPETITION IS THE “NATURAL” STATE OF SOCIETY.

Most liberal philosophers are dubious about socialist ideology. Human beings, they reply, may be “naturally” aggressive, competitive and idle, rather than industrious and co-operative. And a socialist society must be less free because economic equality has to be imposed onto all.

The eccentric Charles Fourier (1772–1837) agreed with Saint-Simon that human history showed the inevitability of enlightenment and progress. Human beings had to progress through 36 different historical periods before they could experience a time of social and political perfection. His most famous work The Theory of Universal Harmony is an extraordinary Utopian fantasy proposing communities (or “Phalansteries”) of 1,610 people, living communally in one huge building and working each day at 12 different jobs.

WORK WILL BE ALLOCATED TO THOSE WHO HAVE A “PASSION” FOR IT. INDIVIDUALS WILL FORM NON-HIERARCHICAL RELATIONSHIPS WITH EACH OTHER AND HAVE DIFFERENT SEXUAL PARTNERS. CHILDREN WILL BE RAISED COMMUNALLY. THE SELF-INTEREST AND NATURAL INCLINATIONS OF EVERY INDIVIDUAL WOULD THEREBY BE FULFILLED AND THIS WOULD SPONTANEOUSLY PRODUCE THE GENERAL INTEREST OF ALL. AT LEAST, FOURIER EMPHASIZES HAPPINESS AND SPONTANEITY, AND DOES NOT SUBORDINATE THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE STATE.

Many English writers and philosophers were initially enthralled by events in France but then horrified by the excesses of “The Terror” which gave revolutions a bad name. Robert Owen (1771–1858) believed that the social and economic changes he favoured would occur naturally, without any need for violent upheaval.

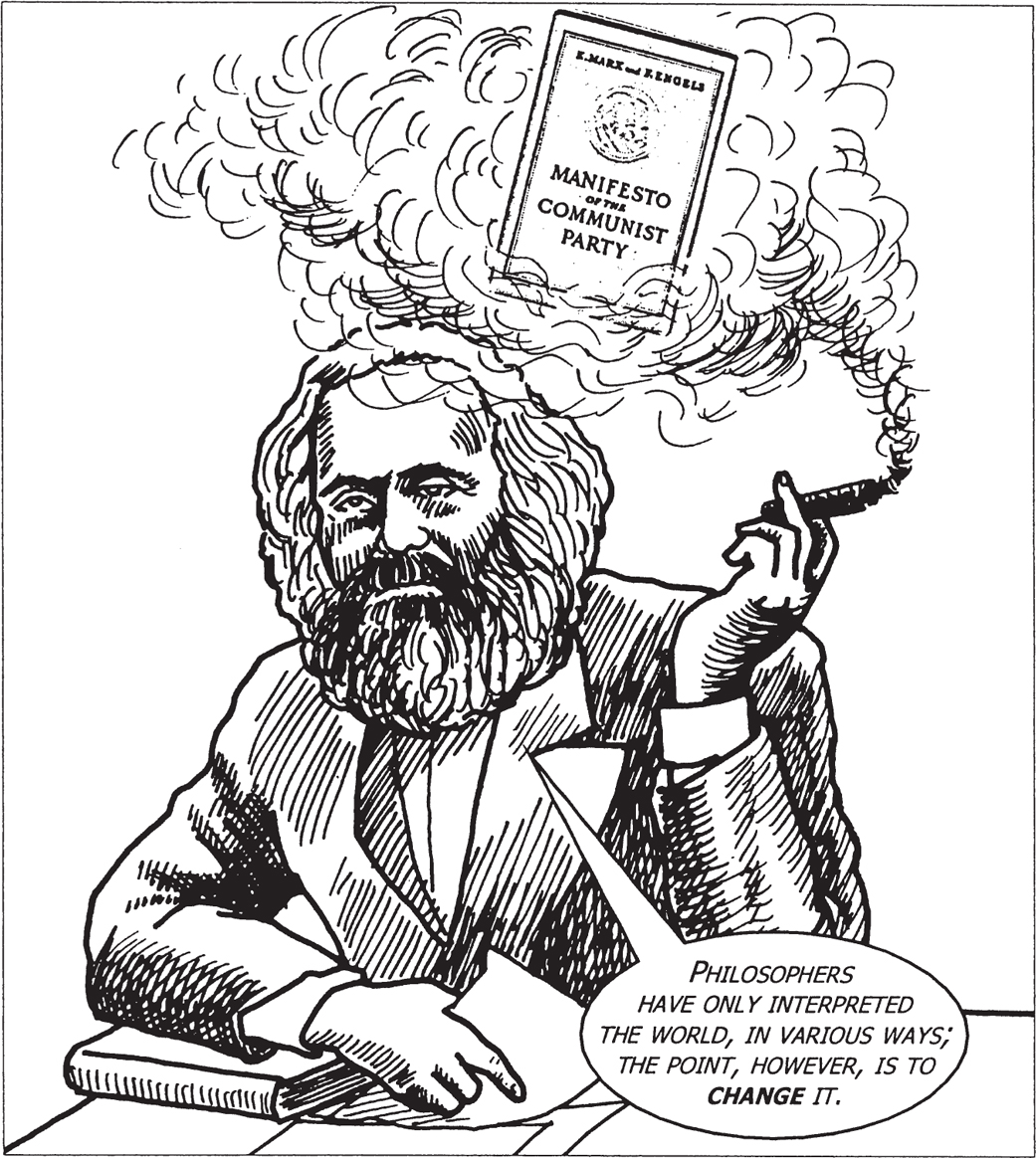

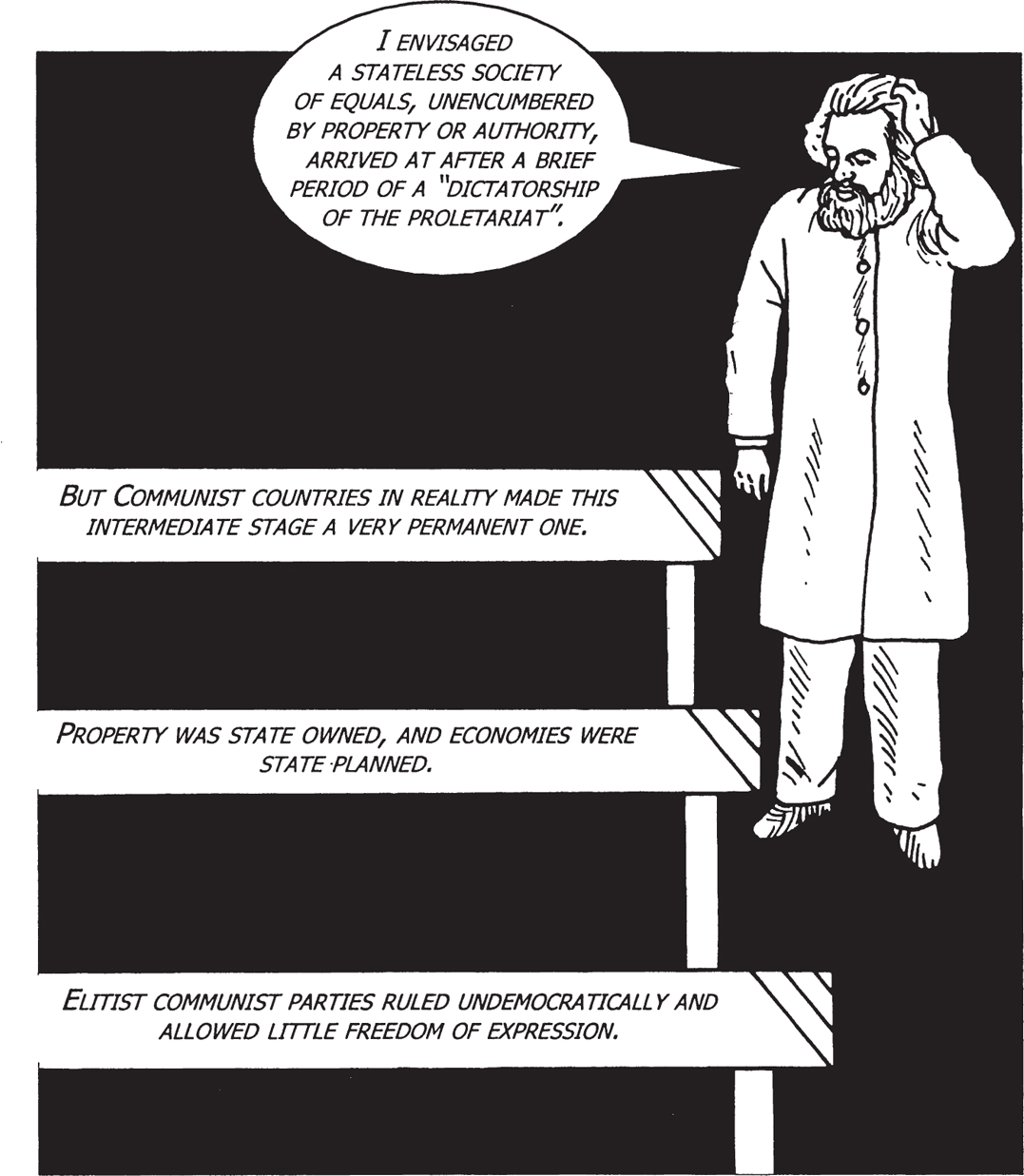

THE BRITISH WILL SOON COME TO RECOGNIZE THE MERITS OF COMMUNISM, AND IT WILL GRADUALLY BE ADOPTED BY ALL. I CRITICIZED EARLY SOCIALISTS LIKE OWEN AS “UTOPIANIST” FOR FONDLY BELIEVING THAT A SOCIALIST SOCIETY WOULD EVOLVE BY APPEALING TO THE GOODWILL OF THE PRIVILEGED CLASSES. THE CAPITALIST STATE WILL NEED RATHER MORE THEN RATIONAL PERSUASION IF IT IS EVER TO “WITHER AWAY”!

Owen, the “father of English Socialism”, prided himself on being ignorant of most works of political philosophy. He was a manager and then owner of various cotton mills, and a great social reformer. In New Lanark, he devised a model village for the workers at his factories, and made a brief attempt to establish a more radical communitarian society in New Harmony, Indiana.

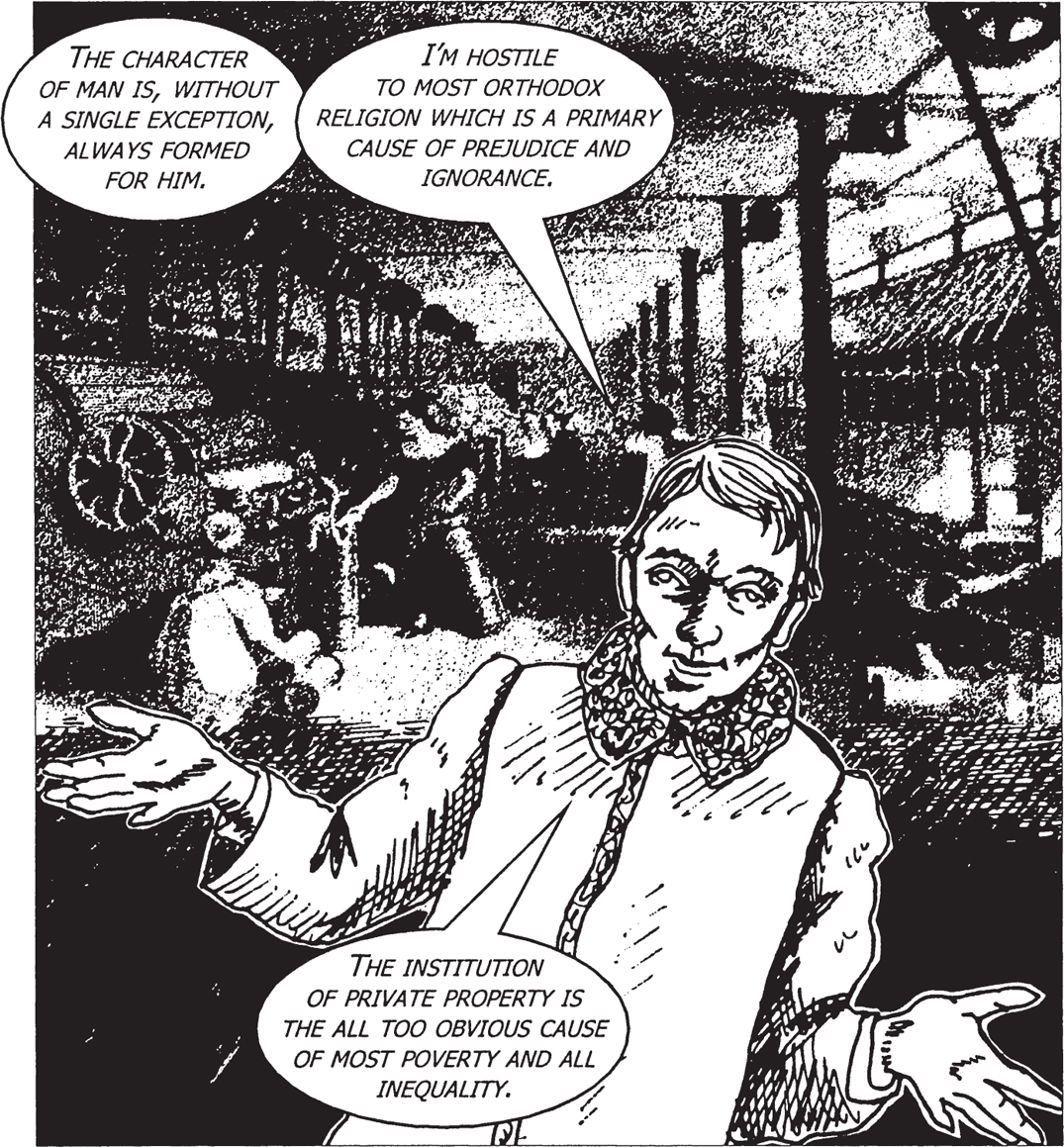

Owen was also closely involved with both the co-operative and trade-union movements in Britain. In A New View of Society, he firmly agreed with Rousseau that human beings are determined by social, educational and economic circumstances – the poor are rarely poor because they are idle or feckless.

THE CHARACTER OF MAN IS, WITHOUT A SINGLE EXCEPTION, ALWAYS FORMED FOR HIM. I’M HOSTILE TO MOST ORTHODOX RELIGION WHICH IS A PRIMARY CAUSE OF PREJUDICE AND IGNORANCE. THE INSTITUTION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY IS THE ALL TOO OBVIOUS CAUSE OF MOST POVERTY AND ALL INEQUALITY.

Owen had his own unique vision of a future society – small-scale self-governing communities of workers and families owning all the means of production. Only such small self-supporting communities could ever be truly democratic. Eventually, when the whole world consisted of federations of agricultural and industrial communities, the need for governments and States would disappear.

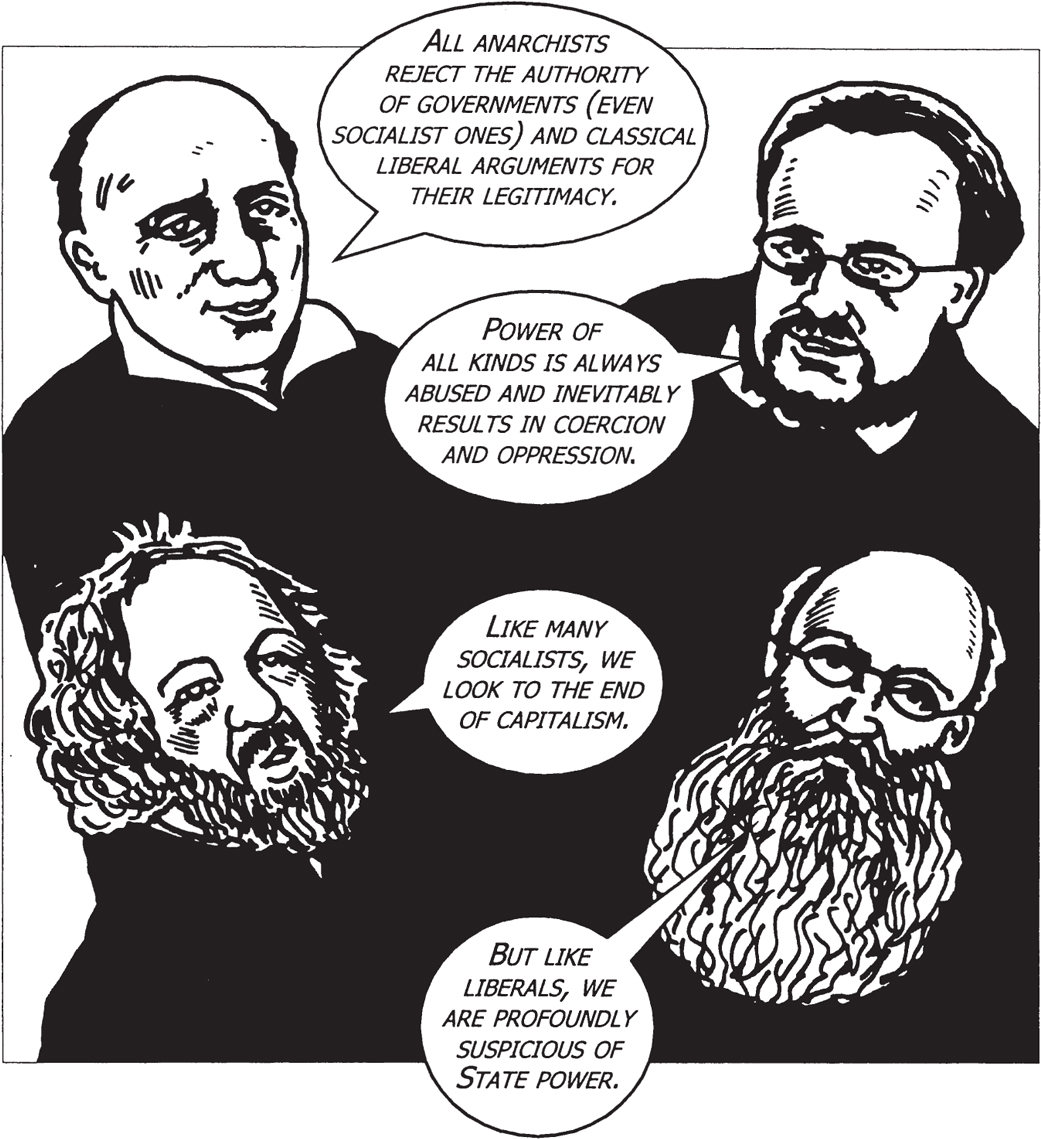

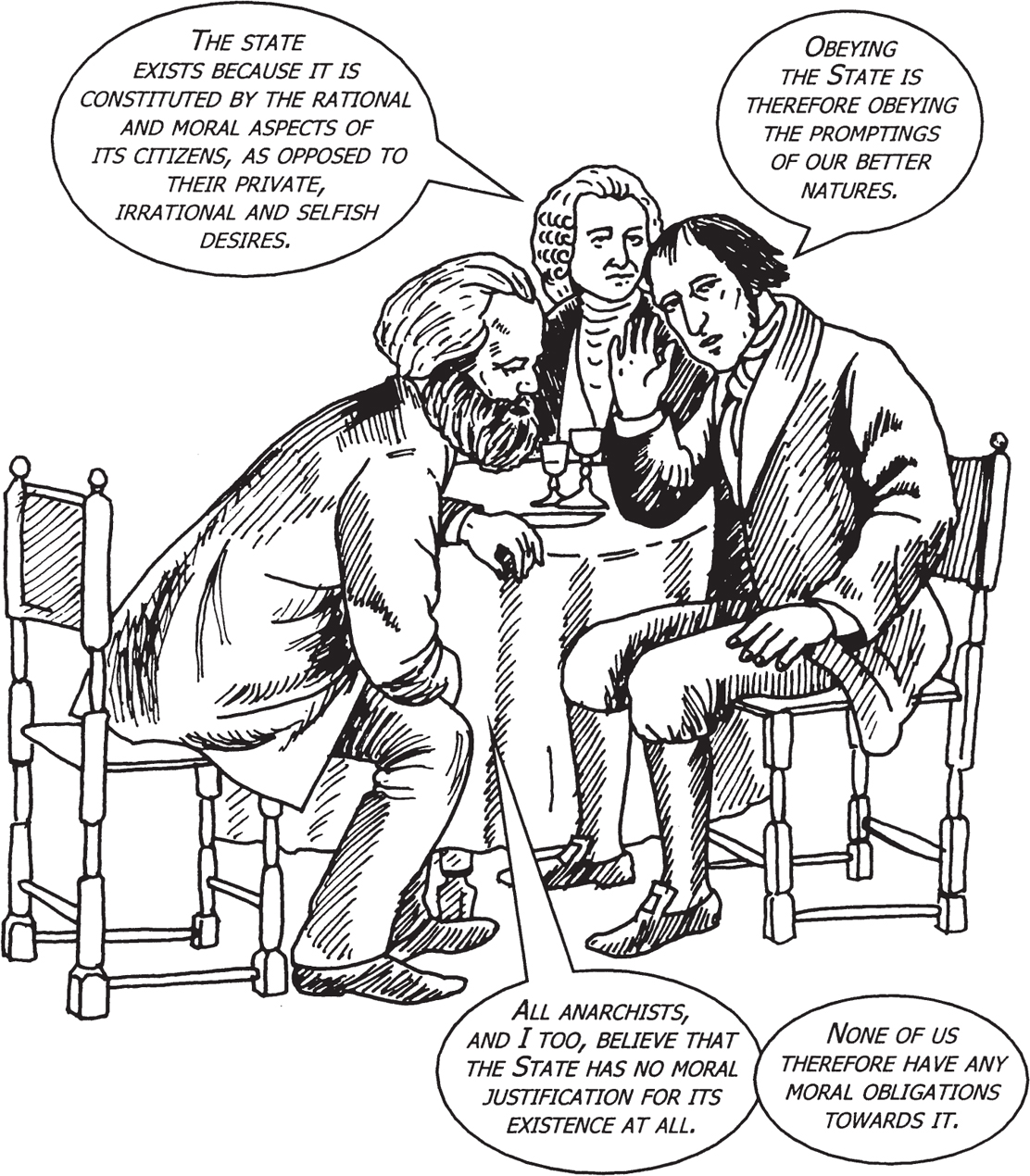

Anarchism is the other great political ideology fathered by the French Revolution. Anarchist ideology has much in common with socialism but firmly believes that individuals and societies can be organized without any need for state coercion. Societies are natural but states are artificial impositions. William Godwin (1756–1836) was inspired by the Revolution to write his book Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) in which he argued for a stateless society. Some other key anarchists are Pierre Proudhon (1809–65), Mikhail Bakunin (1814–76) and Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921).

ALL ANARCHISTS REJECT THE AUTHORITY OF GOVERNMENTS (EVEN SOCIALIST ONES) AND CLASSICAL LIBERAL ARGUMENTS FOR THEIR LEGITIMACY. POWER OF ALL KINDS IS ALWAYS ABUSED AND INEVITABLY RESULTS IN COERCION AND OPPRESSION. LIKE MANY SOCIALISTS, WE LOOK TO THE END OF CAPITALISM. BUT LIKE LIBERALS, WE ARE PROFOUNDLY SUSPICIOUS OF STATE POWER.

Anarchists envisage a future society free of exploitation and inequality, and somehow more “rational” or “natural” than any that now exist. Personal freedom would be maximized, material goods fairly distributed, and governments would cease to exist.

How this attractive state of affairs can be achieved, however, is a problem that has always divided anarchists because they give different accounts of human nature, the altruism of which it is capable and therefore of the forms of economic life appropriate to such beliefs.

PROUDHON’S “MUTUALISM” INDIVIDUAL OR GROUPS OF SMALLHOLDERS AND ARTISANS WHO POSSESS THEIR OWN MEANS OF PRODUCTION CAN ONLY BE REWARDED FOR THEIR OWN LABOURS. THEY CANNOT BENEFIT FROM THE WORK OF OTHERS.

BAKUNIN’S “COLLECTIVISM” I ALLOW FOR A MUCH LARGER-SCALE ORGANIZED LABOUR IN WHICH INDIVIDUALS ARE APPROPRIATELY REWARDED FOR THEIR WORK.

KROPOTKIN’S “COMMUNISM” ALL MATERIAL GOODS MUST BE COMMUNALLY OWNED, AND ONLY LOCAL COMMUNES CAN DECIDE HOW TO MEET THE NEEDS OF THEIR MEMBERS. KROPOTKIN IS HIGHLY OPTIMISTIC ABOUT THE WILLINGNESS OF INDIVIDUALS TO HAVE NO PROPERTY OF THEIR OWN AND TO WORK WITHOUT MATERIAL INCENTIVES OF ANY KIND.

Some anarchists are right-wing libertarians who reject any State interference in the affairs of the individual – even if this means that powerful capitalists will flourish at the expense of everyone else.

Those very few short-lived anarchist societies have usually been violently suppressed – for instance, by Spanish Fascism in the Civil War of 1936–9 and Russian Bolshevism in 1921. But anarchist ideology itself seems unlikely to disappear. It is a useful corrective to authoritarian aspects of socialist ideology and has contributed greatly towards modern feminist theory and practice. Various direct-action campaigns, like the current movement against global capitalism, are “anarchist inspired”.

INDIVIDUALS HAVE TO SURRENDER THEIR NATURAL FREEDOMS TO A SOCIAL MORALITY OF SOME SORT, IF ANY SOCIETY IS TO GET OFF THE GROUND. ANARCHISTS INSIST THAT THIS KIND OF SELF-SACRIFICE AND CONFORMITY IS EITHER INSTINCTIVE OR CAN BE TAUGHT. BUT ANARCHIST APPEALS TO WHAT IS “RATIONAL” OR “NATURAL” DO NOT ALWAYS CONVINCE THE UNCONVERTED.

Quite what a “natural society” without governments would be like is anyone’s guess. So again, as always, political ideology depends on the even more speculative one about the “true nature” of human beings.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) was a professional academic for most of his life and an employee of the Prussian state.

LIKE ROUSSEAU I WAS IMPRESSED BY THE SOCIAL COHESION OF THE GREEK POLIS. BUT HEGEL REALIZED, MORE SENSIBLY, THAT HUGE MODERN POLITICAL STATES COULD NO LONGER IMITATE THE DIRECT DEMOCRACY OF ATHENS.

Hegel agreed that civil society and the State were more or less the same thing and, like Rousseau, rarely made much distinction between them. For Hegel, the State is an ethical entity with a unique identity of its own, not just an artificial legal arrangement made by individuals striving to protect their own interests.

Like most political philosophers, Hegel tries to reconcile subjective individuals, and their specific interests, with their equal need for objective social and political institutions.

LIKE ROUSSEAU, I RECOGNIZE THAT THERE IS A COMPLEX INTERRELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE INDIVIDUALS WHO MAKE SOCIETY AND THE SOCIETY THAT MAKES THEM.

It is a complicated and lengthy interactive process which Hegel explores at length in The Philosophy of Right.

Hegel begins by pointing out that human beings are social animals defined by their relation to others.

THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF CHILDREN IS FIRST DETERMINED BY FAMILIES – TO WHICH THEY ARE INSTINCTIVELY LOYAL. THE MASTER IS DEFINED BY THE SLAVE, EVEN MORE THAN THE SLAVE BY THE MASTER. FOR ADULTS, IT IS THE MORE COMPLEX RELATIONSHIPS OF THE LARGER WORLD OF CIVIC SOCIETY THAT DETERMINES THEIR INNER BEING.

Adult individuals have a greater sense of their own unique identity, are also driven by self-interest and a desire to accumulate property, so their relationships with others are primarily economic. But a market economy needs to be controlled by a legal system so that exchange is well regulated. And, according to Locke, that is more or less how the State begins and its function ends.

Hegel’s State has to be much more than just a regulatory body. It is not a product of contractual negotiations but the organic and inevitable consequence of how human beings are. It is therefore the destiny of human beings to develop within States. The State has an ethical dimension beyond the self-interest of its individual members.

THE STATE IS ALMOST AN EXTENSION OF “FAMILY” BECAUSE IT DEMANDS A SIMILAR MEASURE OF ALTRUISTIC BEHAVIOUR AND SOLIDARITY AMONG ITS CITIZENS. IT EXPECTS THEM TO FIGHT IN ITS DEFENCE AND TO PAY TAXES TO SUPPORT ITS WEAKER MEMBERS.

And States don’t just control civic society – they constitute it. They make “rational freedom” possible for all. Being a part of the State also changes the consciousness of each individual – how they think about themselves and each other.

Citizenship of a modern State creates more individual freedom than was ever possible within the ancient Greek Polis. Individuals can pursue their own interests in various economic, cultural and religious activities, as well as participating in social and political life.

THE STATE MAKES POSSIBLE BOTH THE MAXIMUM SATISFACTION OF THE INDIVIDUAL’S PARTICULAR WANTS AND NEEDS AND THE REALIZATION OF ONE’S ESSENTIAL NATURE AND TRUE FREEDOM.

Hegel’s ideal political society consists of an Assembly of States in which different elements of society have a say in the legislature and political decision making. An upper echelon of professional civil servants (the “universal class”) ensures that no one interest group comes to dominate. Rather like Plato’s Guardians, this élite group is appointed on merit and is extremely powerful.

Hegel’s political structure is headed by a hereditary monarch, a symbolic figure who embodies the unity of the State. Its framework of checks and balances is conservative, traditional and very similar to the constitutional monarchy of Hegel’s own 19th-century Prussia. Hegel’s feelings about his State are sometimes rather alarming.

THE STATE IS A DIVINE IDEA AS IT EXISTS ON EARTH. WE MUST THEREFORE WORSHIP THE STATE AS THE MANIFESTATION OF THE DIVINE ON EARTH…

Hegel is often accused of being the servile prophet of Prussian nationalism, even though he was in favour of a constitutional monarchy with a well-defined separation of powers, codified law, jury systems and freedom of speech and opinion.

Like many other political philosophies, Hegel’s is founded on an extremely elaborate metaphysics of philosophical idealism, theories about the evolution of human consciousness, and a profoundly historicist vision of human progress. Aristotle maintained that reason was the defining characteristic of human beings.

REASON IS THE VIRTUE WHICH ENABLES US TO GRASP THE INTEGRAL RATIONALITY OF THE UNIVERSE ITSELF. I AGREE. THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF HUMAN BEINGS, THEIR CULTURAL LIFE, CONCEPTUAL EQUIPMENT AND POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS ARE FOREVER CHANGING AND PROGRESSING TOWARDS HIGHER FORMS OF POLITICAL AWARENESS.

Hegel was convinced that history is essentially the evolutionary and progressive narrative of this collective human consciousness, a mysterious entity he called “Spirit”. Individual minds are therefore all part of the one universal mind that determines all that is “real” for human beings.

Human consciousness is never static but constantly evolving more productive conceptual frameworks which stem from the absorption of older, less adequate ones. New experiences can be structured appropriately in progressive stages.

HUMAN CONSCIOUSNESS EVOLVES BY CONFLICTS AND RESOLUTIONS… HUMAN BEINGS DON’T JUST APPREHEND THE WORLD BUT MANIPULATE AND CHANGE IT.

Constant changes in history mean that there must always be a battle between different political ideas in a uniquely Hegelian “logical” process known famously as the “dialectic”. Opposing political theories inevitably enter a complex operation of mutual assimilation (or “synthesis”) to produce yet more progressive notions of the State, citizenship and freedom.

This dialectical process means that human beings will eventually achieve an awareness of the necessity for “rational freedom” – the synthesis between abstract limitless freedom and the demands of social and political life.

THE VIOLENT EXCESSES OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION WERE THE DIRECT RESULT OF AN ABSOLUTE “EMPTY” CONCEPTION OF FREEDOM IN WHICH NO ONE IS ACTUALLY FREE. TRUE POLITICAL FREEDOM IS MODERATED BY RATIONAL POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS WHICH CONTROL THE POTENTIAL IRRATIONALITY OF THE MOB AND DISCOURAGE ARBITRARY TYRANNY.

Hegel concludes that human beings are necessarily state creatures destined to develop within political communities. States are the inevitable result of us being the sort of gregarious, freedom-loving creatures that we are.

HUMAN MINDS PRESUPPOSE THE INSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURES OF SOCIETY… STATES DEVELOP OUT OF THE INNER NATURE OF HUMAN BEINGS AND THEIR NEED FOR INDIVIDUAL FREEDOM AND POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS.

States and citizens together will grow increasingly more rational as the whole teleological process advances through time.

telos, from the Greek, “goal” or “aim” – teleological, “goal-directed”

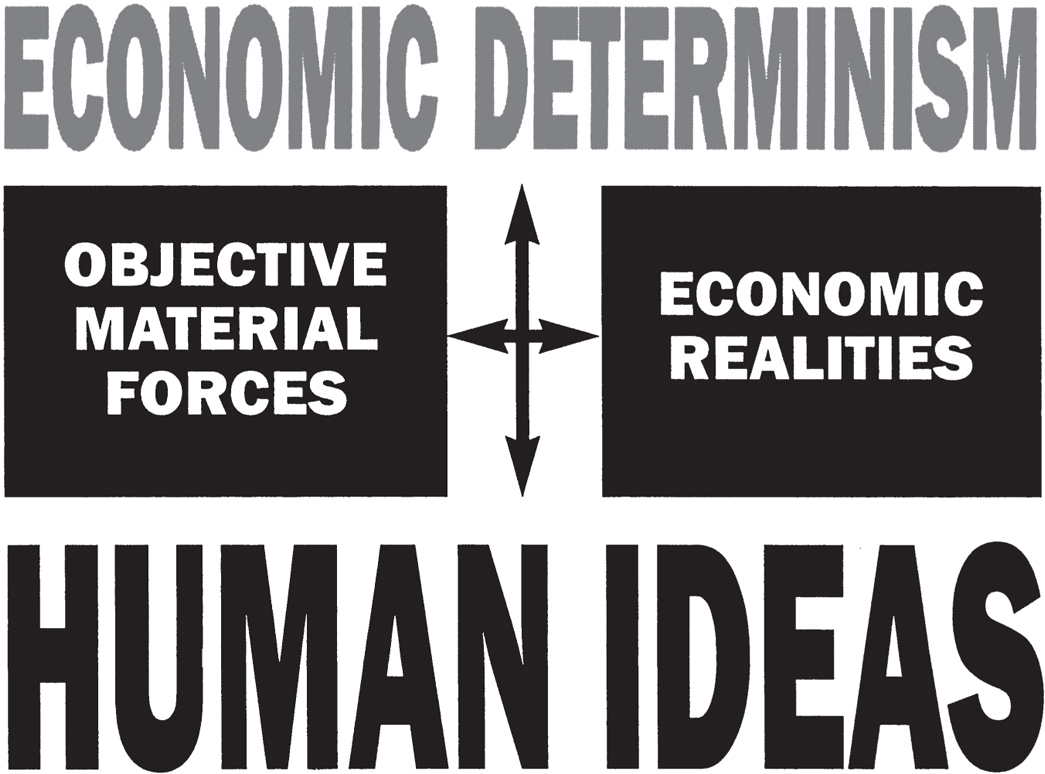

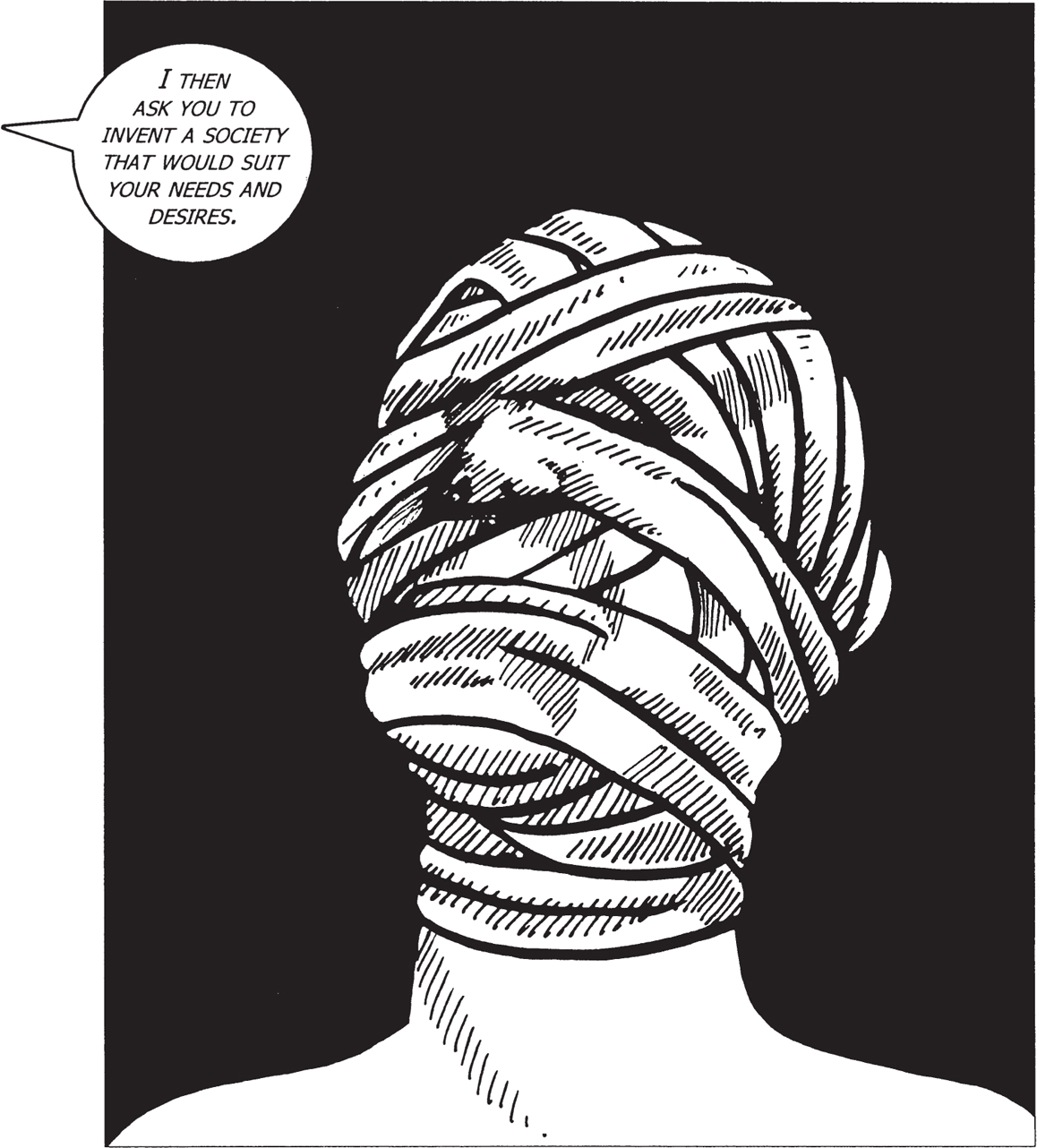

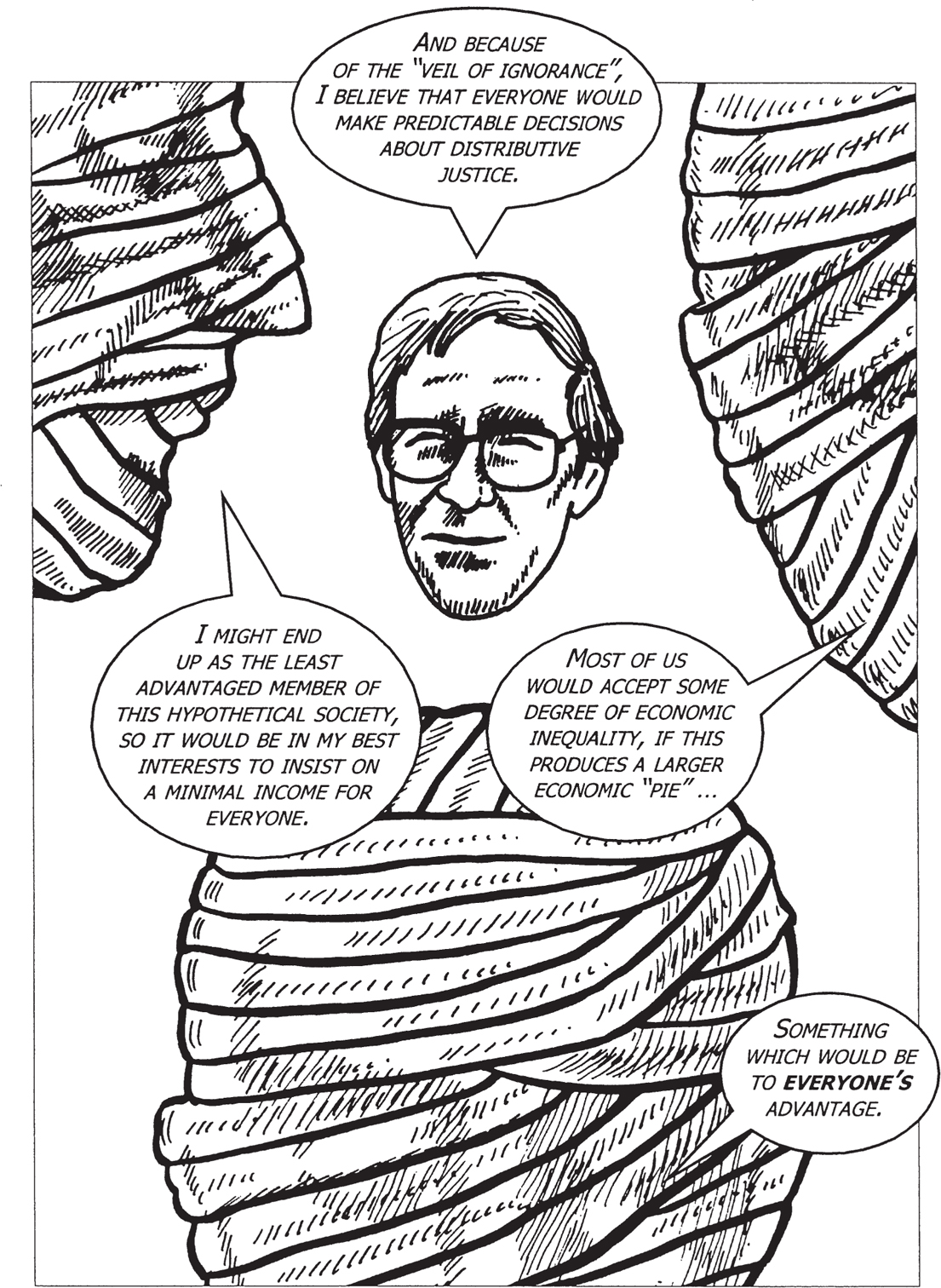

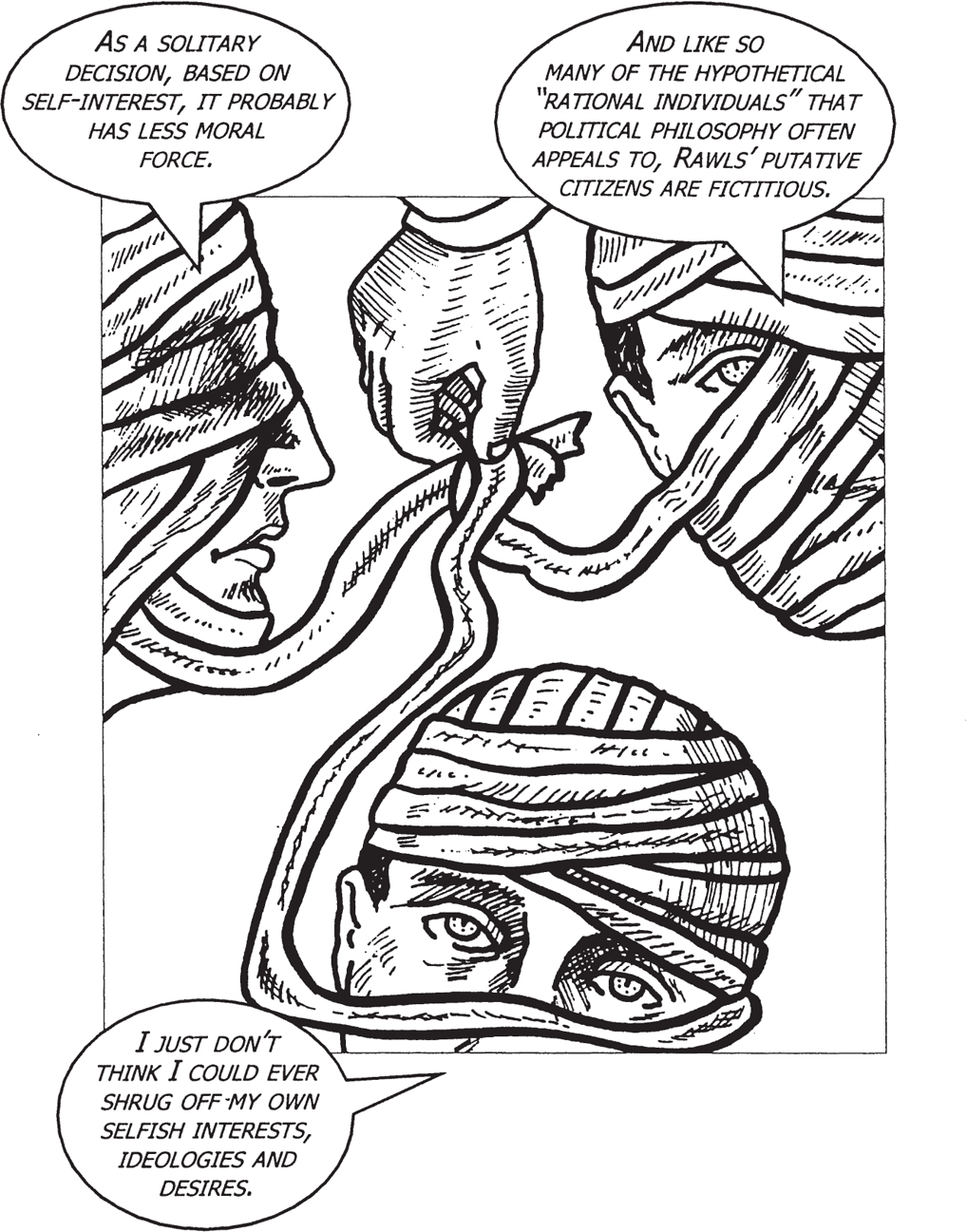

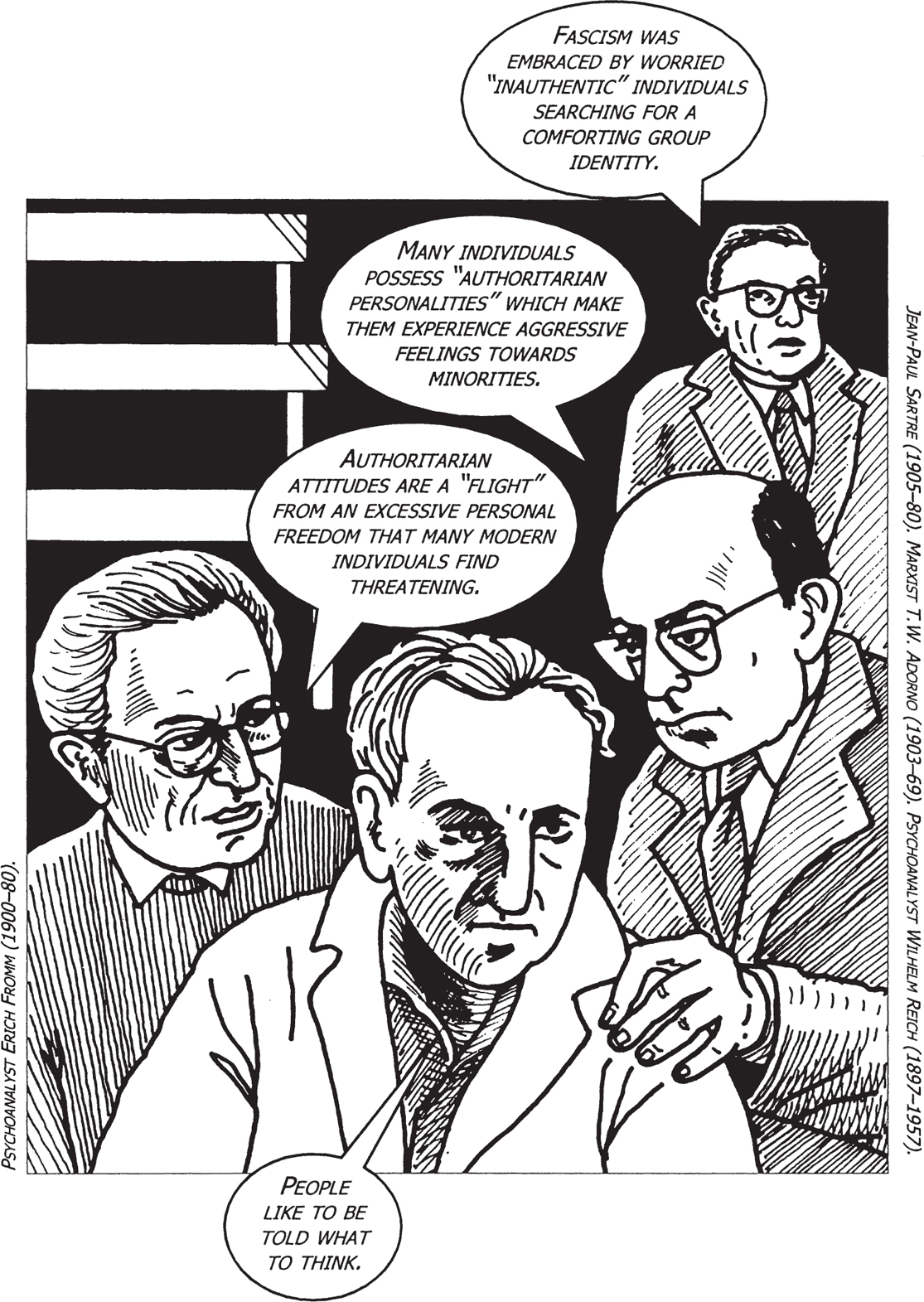

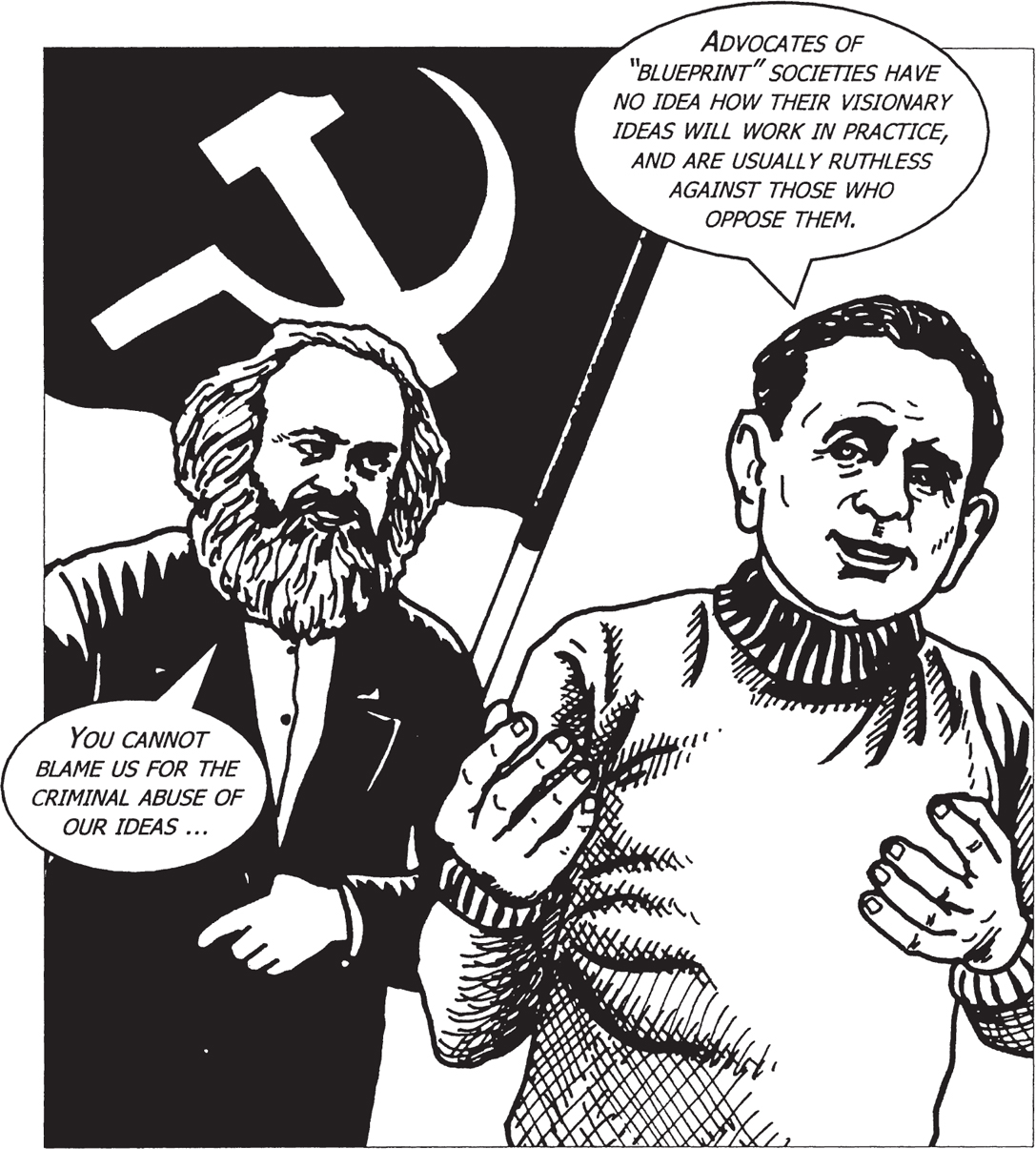

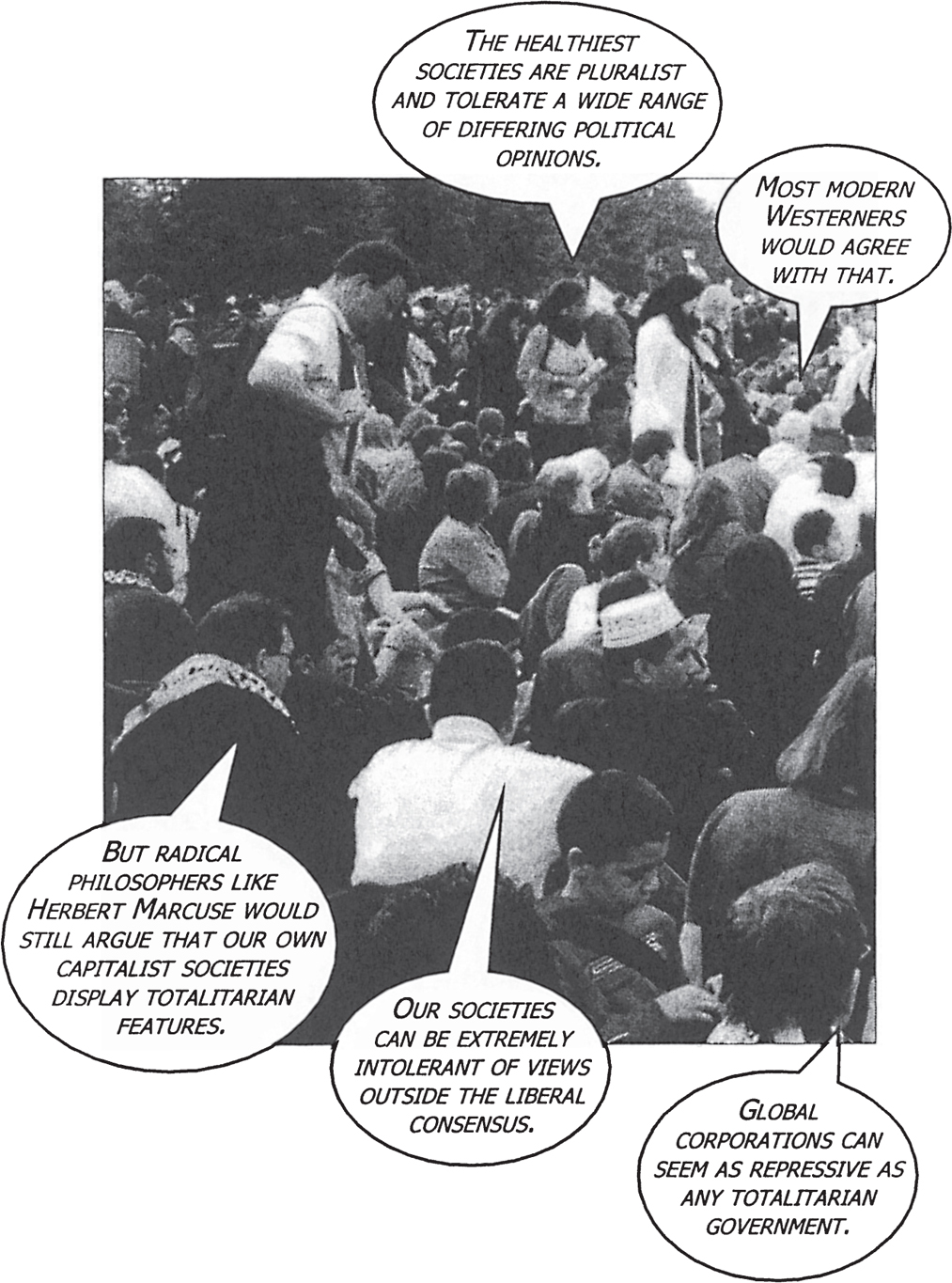

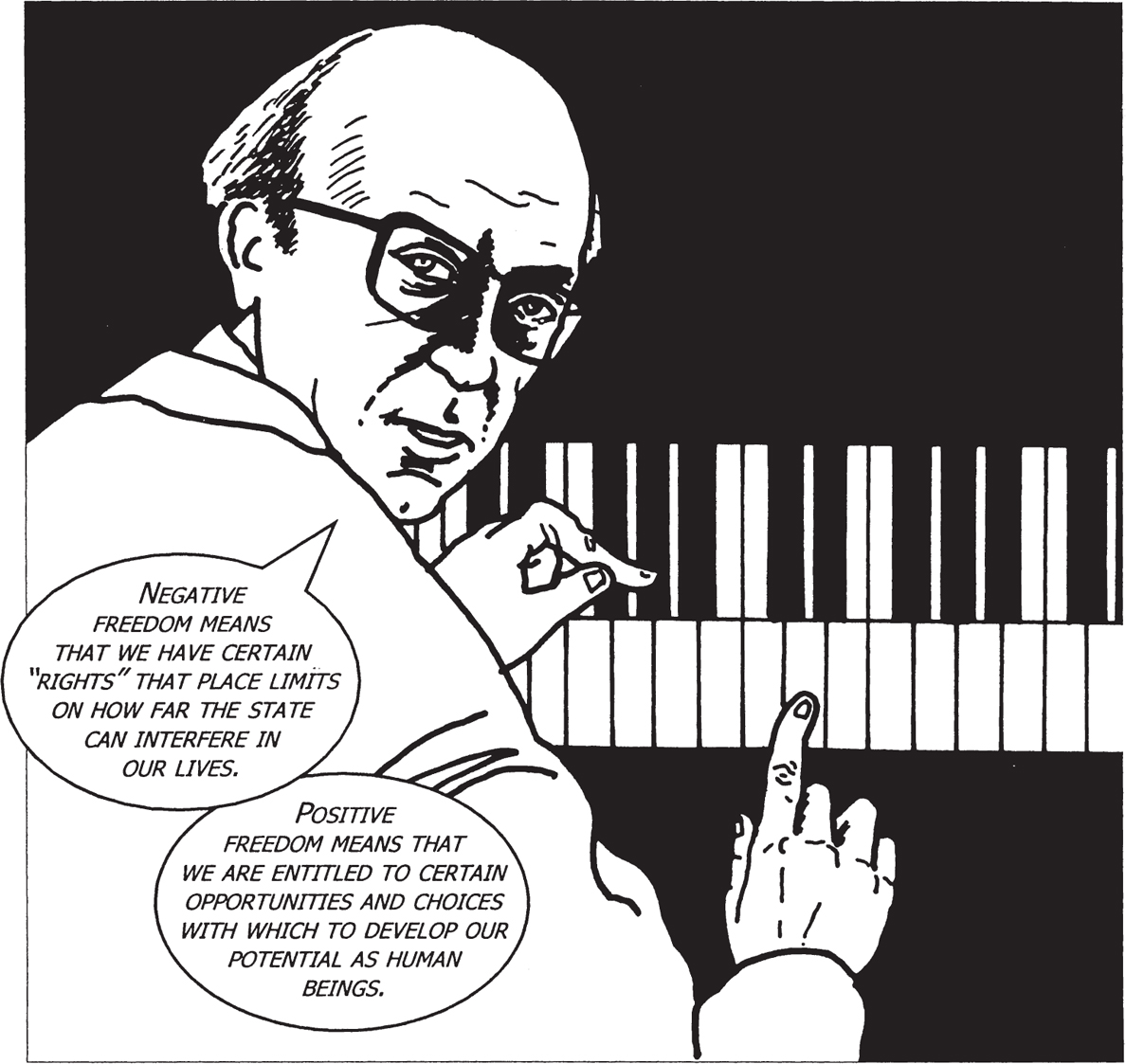

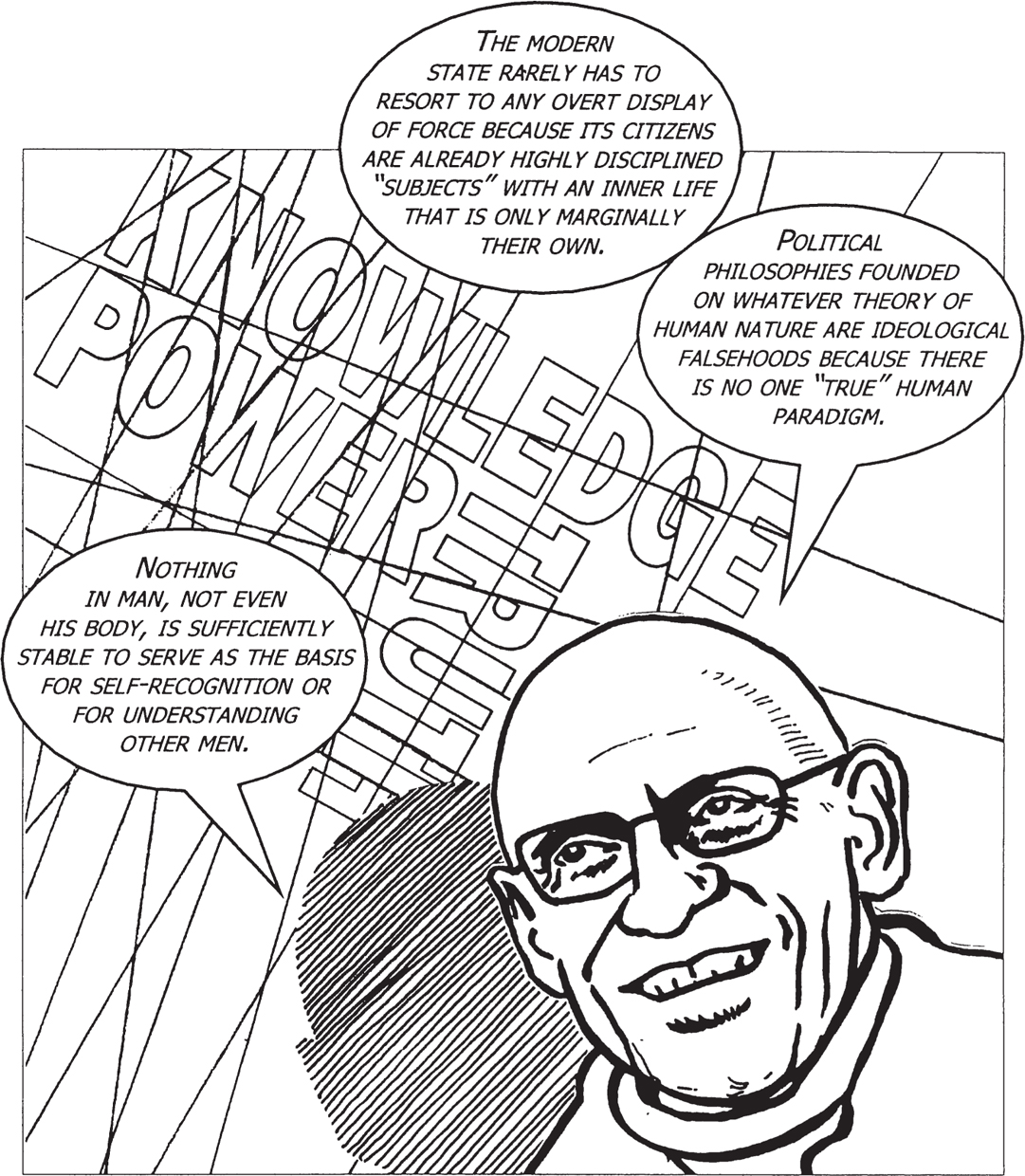

Hegel’s attempts to make the State a logical and ethical offshoot of an evolving human consciousness has not gone unquestioned. Not many philosophers now accept the core “theological” doctrines of Hegelianism – especially his account of “Spirit” as divine universal mind – and not many now believe in his progressive, teleological and historicist account of human consciousness, societies and states.