“MY SON”… “THE WORLD HAS BECOME TOO EVIL. WITH THESE MAGIC WEAPONS, MAKE A NEW WORLD,” SAID THE MOTHER OF THE HERO, THE SON OF AYASH…. SO THE SON OF AYASH TOOK THE WEAPONS AND, ON A MAGIC WATER SNAKE, JOURNEYED DOWN INTO THE REALM OF THE HUMAN SOUL, WHERE HE MET…. [E]VIL AFTER EVIL… THE MOST FEARSOME AMONG THEM THE MAN WHO ATE HUMAN FLESH. —TOMSON HIGHWAY, KISS OF THE FUR QUEEN

18 October 2012

Conversation between Tomson Highway and Sam McKegney in Sam’s office at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

TOMSON HIGHWAY (Cree) is a playwright, novelist, and pianist/songwriter. Born along his parents’ trapline on what would become the Manitoba/Nunavut border, Highway attended Guy Hill Residential School before studying Music and English at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg and the University of Western Ontario in London. After graduating as a concert pianist, Highway spent several years in the field of Indigenous social work, working with children, prison inmates, and street people, and with various cultural educational programs. He worked in the theatre industry in Toronto for several years, acting as artistic director of Native Earth Performing Arts from 1986 to 1992. He is best known for his award-winning plays The Rez Sisters (Fifth House, 1988) and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing (Fifth House, 1989), although he’s written and produced scores more. He is also the author of the semi-autobiographical novel Kiss of the Fur Queen (Doubleday, 1998) and several children’s books published in Cree and English.

SAM MCKEGNEY: Often discussions of Indigenous masculinities start from a deficit model focusing on the negative. And I was wondering if we could begin with discussions of strength. Perhaps you could reflect a bit on positive gender models that emerge from Cree worldview and language.

TOMSON HIGHWAY: Do you have a tablet that I can put on my lap and write on? I’ll do some designs for you because there’s some visual explaining to do. My native language is Cree. I speak two Native languages because I come from a part of the country where Cree people moved so far north—my father, namely, and four other young men at a time in the 1920s—that they moved into Dene territory. I come from the Manitoba/Nunavut border, which is actually Dene territory, so we were Cree people living among the Dene. Our village was half Cree and half Dene. There was the non-status side and there was the status—we’re status—and in order to go from the status Cree side of the village to the non-status Cree part of the village, you had to pass through a Dene section, a Dene neighbourhood. Dene and Cree come from two totally different linguistic families. So we speak both languages because we had to. We had no choice. We didn’t speak English though. English didn’t exist back then. So when you speak Dene and Cree, it’s like being able to speak English and Mandarin. It’s a real gift to have had that as a child because, of course, the other languages came easier. So today I speak fluent French. And I work in English, French, and Cree—I have books published in those languages. So that’s where the big difference comes from.

The fact is that the origin of masculinity—the whole issue of gender—comes from linguistic structure. I think one has to understand that… oh, it’s a long story. How do I put it? Human behaviour is ruled, the subconscious life of an individual is governed by the subconscious life of his community, his society. And the dream world, so to speak, is defined by the mythology of a people. To simplify the explanation—or raccourcir, to shorten it—languages are given birth to by mythologies, by the collective dream world of a society. And they’re given birth to and they’re given form by that dream world. So the structure of a language depends on the nature of the mythology. And mythology spills into the discipline of theology, but the difference, of course, is that theology is only about “God” whereas mythology is about god and man and nature. It’s interesting when you think about it: mythology, in a sense, is a combination of theology, sociology, and biology—the study of gods, men, and nature.

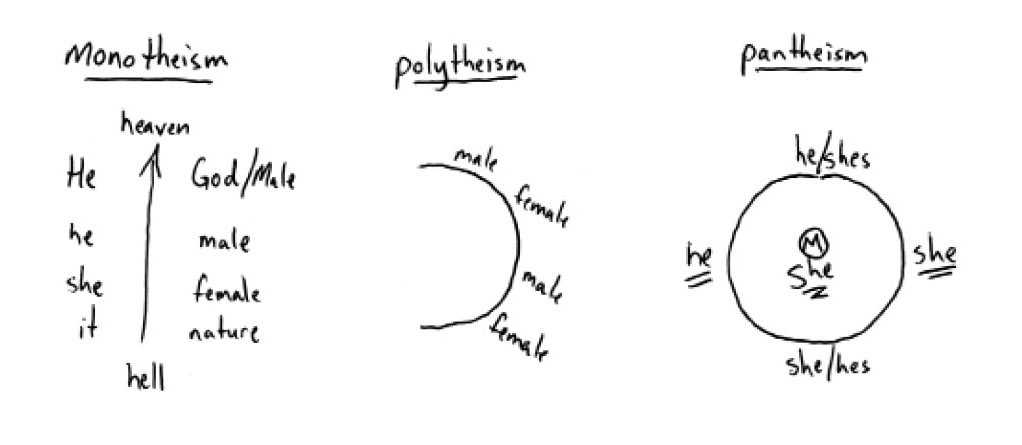

There’s mythologies, of course, all over the world. There’s as many mythologies as there are languages. And last time I counted, they say there’s between 5,000 and 6,000 languages in the world. And each one of them has a superstructure, like I say, given birth to by mythology, so that mythology is what decides the structure of the language. And those mythologies are divided into roughly three different categories: there’s monotheism, there’s polytheism, and there’s pantheism. These are all Greek words: Theos is “god.” So monotheism is about “one” god. Polytheism is about “many” gods. Pantheism is about god in “all”—pan meaning “all.” So the first mythology has one god, the second has many gods, and the third is a society where god has not yet left nature—god is in nature, nature is god; in a sense, biology is god.

So the monotheistic superstructure is Christianity—there’s only one god in Christianity—and polytheism is what preceded Christianity in that part of the world, the eastern Mediterranean. The Greek and Roman mythologies are polytheistic systems, just like today in a society like Japan. Shintoism is a polytheistic superstructure, meaning that there are many many gods in Shintoism. And then there’s pantheism; that’s Native. In monotheism, there’s only one god and it’s also a phallic superstructure. There’s one god and he’s male. Male with a capital M. Then there’s man with a small m. And there’s female with a small f. And finally then there’s nature. So there’s He, he, she, then it. In that order. One of my students asked me, “Is there a She with a capital S on this superstructure?” There’s none. There’s no room for it. There’s no room for the idea of She with a capital S. And the other thing that you’ll notice here is that there’s only two genders: male and female. And the male has complete power over the female. God created man first, and woman is an afterthought from his rib bone. It would be very interesting to see a society where, first of all, god was female—imagine the kind of world we would have if god was female and she created woman first and then created man from her rib bone? What an enormous difference that would make in human behaviour.

So polytheism is not a phallic superstructure. It’s a semi-circular superstructure, interestingly enough, in the sense that there are many gods and goddesses. In fact, the principal deities, the pantheon of twelve gods among the ancient Greeks atop Mount Olympus, consisted of six gods and six goddesses. So it was evenly divided. And there is historical proof of the time in history when one goddess was replaced by a god, resulting in seven male gods and five female gods, and that was the beginning of the end of the idea of divinity in female form. And those gods, as you probably know, are Zeus, the king of the gods; the queen of the goddesses being Hera, his wife; and then there’s Poseidon, god of the sea; there’s Hermes the messenger god; there’s the god of the intellect, Apollo; and then there’s Demeter, the goddess of grain, the goddess of the earth, an earth-based goddess, the goddess of fertility, really; the goddess of war, Athena; and the goddess of love, of human sexuality, Aphrodite, who became Venus in Roman mythology; and so on and so forth. So there’s all these gods and goddesses along this semi-circle and there is room in this polytheistic structure for the idea of male and female divinity.

Over here, pantheism is a complete circle. (My weakness here is that I don’t speak ancient Greek. That would help me tremendously in my analysis of this situation.) But over here there is no “he” and there is no “she.” In the Native languages of North America, so far as I know—certainly Cree, Ojibway, and Dene—there is no “he” and there is no “she.” There is no gender. In the monotheistic superstructure, on the other hand, there seems to be an obsession with division of the universe according to gender. There’s the part of the universe that is male and then there’s the part that is female. And it’s even more pronounced in French with le and la. And it’s even more pronounced in German with der, die, and das. In French un bureau is masculine but une table is feminine. Very interesting that most of the negative nouns are feminine: la colère—anger; la douleur—pain; la tristesse—sadness. Whereas the positive terms, for the most part, are masculine: le bonheur—happiness. And of course there’s always exceptions, but that’s generally the case. And it’s always the man having superior power over the woman because of the creation story that underpins this superstructure.

ON THE LIVING CIRCLE, THE ANIMATE CIRCLE, THERE’S ROOM FOR THE MALE AND THE FEMALE, AS WELL AS ALL OF THESE OTHER SHADES OF GENDER. WE HAVE THE HE/SHES, AND WE HAVE THE SHE/HES. WE HAVE ROOM FOR THE IDEA OF MEN WITH THE SOULS OF WOMEN AND WOMEN WITH THE SOULS OF MEN.

If the universe in a monotheistic system is divided into genders—that which is male and that which is female—the universe in a pantheistic system is divided into animate and inanimate. There’s the animate part of the universe and there’s the inanimate part of the universe, meaning that there’s that which has a soul and that which has no soul. Anything that has biological life is a living, animate creature. In Cree we’d say, ana nepêw, the man. Ana iskwéw, the woman. Ana mistik, the tree—ana being the article. Ana asinîy, the rock. They all have a place in the circle. There is no gender difference and one does not have power over the other. The only way that these animate creatures can be made inanimate is if you kill the man and the body becomes anima mêo, the corpse. It’s no longer a he, it’s an it. Anima, that’s one of the great accidents of linguistics, in that it has nothing to do with the Latin anima—which is where the word “animate” comes from, meaning “soul.” The only way you can make this living creature inanimate is to remove the life, so she becomes anima mêo, a corpse. The only way you can turn the tree into an inanimate creature is to chop it down and turn it into a chair. So that a chair is a tree without a soul. And a rock has a soul, according to this superstructure, and the only way you can make it not have a soul is to kill it, to crush it up into cement, and to make a sidewalk out of that cement. So that sidewalk is a rock without a soul. So the rock is now anima miskêw. So the articles change accordingly.

Basically in Cree all of these living creatures have equal status, as do all of these non-living creatures. So that this circle contains two circles: there’s the circle with the animate creatures and within that is the circle with the inanimate creatures. When a man dies, he goes to another circle. He undergoes transference. He doesn’t go to hell or heaven. He just stays here, which is why we believe that the planet is just filled with our ancestors. They’re still here, they never went anywhere. My brother, who died of AIDS twenty-one years ago—tomorrow is the anniversary of his death—he never went anywhere, he’s still here, still with me. Even biologically, I have his lips, I have his eyes, I have this, I have that. I even have his voice, apparently.

So there’s room on the living circle, the animate circle, there’s room for the male and the female, as well as all of these other shades of gender. We have the he/shes, and we have the she/hes. We have room for the idea of men with the souls of women and women with the souls of men. Those are gay people. To put it in blunt terms, the role of men in the circle of our society was to hunt and the role of women was to give birth—my mother had twelve children and my father was a fabulous hunter—but there was also a group who biologically were assigned neither role. Neither the hunt nor giving birth. So our responsibility became the spirit, to take care of the spirit of the community, which is where all the artists are from. This is why so many artists are gay. And that’s our job, to create this magic; we’re the magicians.

EVEN THE PENIS HAS NO SOUL. IT’S AN INANIMATE CREATURE BY ITSELF. THE ONLY PARTS OF THE HUMAN BODY THAT HAVE A SOUL BY THEMSELVES ARE THE VAGINA, THE WOMB, AND THE BREASTS—THE FEMALE RECREATIVE PARTS OF THE HUMAN BODY.

Noticing European life from up close as a Native man, the great arc of European history contains three arcs. First of all, there’s war after war after war after war in which human blood has been spilt; I swear to god, there’s not a square inch of that continent that hasn’t been soaked in human blood. And 97 percent of that is caused by “man.” When you look at world wars, where are the women? Why are these men killing each other? Where are the women in all that? When you see these military marches, thousands and thousands and thousands of soldiers… it’s just men. Where are the women? Anyway, that’s one part, the destruction, the pain, and the agony and the trauma. Europeans are a traumatized people. To this very day, we talk to our friends in France about the Second World War and they start to cry because their parents were prisoners of war. There are Jewish friends who lost parents to the Holocaust, who were incinerated in Auschwitz.

And that’s one arc. The other picture you see that astonishes you even more is that they’re still there, the Europeans are still there, and they’re beautiful. The Italians are beautiful. The Spanish are beautiful. The Germans are beautiful, physically and emotionally. And that beauty was given to us by “woman.” She’s the one who nurtured those people, who made them survive, who gave birth and rebirth and rebirth. And the third arc of European civilization is the shoes, the hair, the fashion, the theatre, the poetry, the music, the architecture, the film, the pure spectacle of it all, a spectacle for which people pay millions of dollars from all over the world to come and gawk at. And that was given to the planet by these people—the he/shes and the she/hes. And yet in the monotheistic superstructure there’s no room for them. There is no room for a third gender here in this phallic superstructure. Nobody crosses the path. Anybody who crosses that dividing line is to be destroyed, and we were destroyed by the thousands.

So on this side of the diagram the idea of god in female form is completely non-existent, and god as male has complete power over us, the male has complete power over the woman, and all have complete power over nature. On the other side of the diagram the power is nature. To take this idea of the phallic structure versus the yonic structure—meaning “womb-like” structure—the idea of the animate and inanimate dichotomy needs to be made more specific. The parts of the human body are, by themselves, all inanimate. The head by itself doesn’t have a soul. The hand by itself doesn’t have a soul. The stomach by itself doesn’t have a soul. Even the heart by itself doesn’t have a soul. On the male side, even the penis has no soul. It’s an inanimate creature by itself. The only parts of the human body that have a soul by themselves are the vagina, the womb, and the breasts—the female recreative parts of the human body. Those are the only parts that have a soul. And that is the very centre of the idea of matriarchy and the idea of divinity in female form. Where in one superstructure god is super-male, in the pantheistic superstructure god is super-female. And that’s where the She with a capital S belongs. From this other superstructure she’s been completely excised, creating the male/female power imbalance.

When 1492 came along and Columbus came along, the most significant item in his baggage was the religion—the theology/mythology. That’s when the god met the goddess for the first time and punctured her, and the circle was broken, almost destroyed, to serve the Genesis-to-Revelation straight line. So what we artists are doing right now is trying our very best, especially female artists and feminist thinkers, to bend this straight line back into a circle, to repair the circle. If the principal prayer in the Christian canon says, “Our Father, who art in Heaven,” where’s our mother? The fourteenth century and the fifteenth century, when the witch-burnings were at their height in Europe, that was the very same period that the monotheistic superstructure arrived in North America. I live in France; I swear to god, when the wind has a certain power, you can hear the women screaming and howling in the middle of the night. It was the thing to do on a Saturday night in villages across Germany and France and Spain and England, to go down to the village square and watch the women scream their tits off through the flames. Wholesale destruction. And as recently as 1945, women in France weren’t allowed to vote or own property. And as recently as sixty years ago here on this campus women weren’t allowed; they weren’t allowed to set foot on campus. They were chained to their wombs and their kitchens. And now, finally, the superstructure that made such horror is being bent back into a curve and the circle is being repaired. And that’s what we see right now.

SM: How can even those who identify as heterosexual men learn to recognize that health and power for women is, in fact, a pathway towards their own health and well-being? In other words, how do they not perceive women’s power as their own emasculation?

TH: That’s the other side of the coin. That’s the dark side of the coin, eh? It’s easy to trash all men. I mean, god knows, where I come from up north, where Christianity just swept across like a wildfire, up there—I mean the situation is changing now, thank goodness—but when I was growing up, men used their women like punching bags. Wife battery was like… it was like a festival. It was like an art form. And rape happens every day. Even down here in Kingston, a town as civilized as it is, is not free of the battery of women. There are women being beaten right now somewhere in this city.

Let me put it this way, I grew up and went to school with Helen Betty Osborne—you know that name? She’s from Norway House in northern Manitoba and I’m from Brochet, Manitoba. We went to the same school and we’re about the same age. In fact, she was my younger brother’s girlfriend for a short while, like puppy love—fifteen or sixteen, whatever it was. Those four guys who abducted Helen Betty Osborne dragged her off into the forest, and raped her by ramming a screwdriver fixty-six times up her vagina and left her there to bleed to death—it was November in northern Manitoba, that’s already winter—those guys are considered “normal.” They’re just normal healthy guys. There’s no taboo against that kind of behaviour. That’s just what men do with girls. They were just out, four guys having a good time with a girl on a Saturday night. That’s all it was. You know, if those guys had gone into those bushes and made love to each other instead, then and only then would they be considered sick. Where does that thinking come from? It comes from that [points to the phallic, monotheistic superstructure on the diagram]. Just for that one crime alone, it’s worth it to take this superstructure apart and have it replaced by a woman-centred superstructure, the pantheistic circle. Just for that one crime alone. Imagine that happened to your daughter, you know?

IT’S WHEN YOU BELIEVE THAT YOU’RE 100 PERCENT MALE THAT THE TROUBLE STARTS. THAT SIMPLY DOESN’T EXIST BIOLOGICALLY, SPIRITUALLY, PSYCHOLOGICALLY.

On the other side, as a gay man, when I look at stories like that and I see all these women being battered across America, I thank my lucky stars every day of my life that I’m not a heterosexual man. I’m so proud to be who I am. For one thing—we’re not perfect, we’re far from perfect, there’s a lot of abuse that happens within the gay community—but we don’t treat women like meat. We don’t consider women as just a hole to stick your dick into, which is what too many heterosexual men think of women as. There’s way too much of that kind of thinking and that kind of behaviour—running through women like pieces of toilet paper. But, on the other hand, there’s an awful lot of straight men who are trying their very, very best to reverse that trend, to change their behaviour for the better. And I’m surrounded by them. Some of my best friends are straight men; I just love them. When they’re beautiful, they’re beautiful. And one of the things that makes them truly beautiful is when they have no fear of their femininity, their feminine sides. Because ultimately, whether we’re born into this world biologically male or biologically female, we are either 90 percent female and 10 percent male—eighty-twenty, seventy-thirty, sixty-forty, fifty-fifty. Myself, actually, I’d imagine I’m about forty-sixty. I love women too… just not as much as men, physically. Emotionally, they’re equals. It’s when you believe that you’re 100 percent male that the trouble starts. That simply doesn’t exist biologically, spiritually, psychologically. We all have elements of both sexes in us. And so men who are scared of that, who are terrified, and who are trying to prove that they are 100 percent male, those are the men that go around ramming screwdrivers up people’s vaginas. They’re real men.

And, on the other hand, if those boys had been seen walking down the street holding hands and kissing in public, I think that they’d be much healthier men. And so I’m surrounded by these heterosexual men who are not afraid of holding hands, who are not afraid of hugging. There are even heterosexual men who’ve gone to bed together—you don’t even have to have sex. Sex is so grossly overrated in this society. And there are reasons behind that that go back again to those superstructures. In only one of these superstructures is there a story of eviction from the garden. And guess which one? According to the other ones we’re still in the garden. You don’t think that tree over there in the garden is a miracle? So I have friends like that whom I absolutely adore. And fascinatingly enough, thank god, those are the men who make the best partners to women, who treat women as equals. And even more importantly, those are usually the men who make the best parents.

SM: You were saying that a lot of violence erupts from male panic around “what if I’m not 100 percent masculine, if I’m not 100 percent male?”—which connects intriguingly to some of the depictions in your work. For instance, Big Joey [in Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing] dreams of blood spilling out from his groin, which he perceives as an indication of his impotence or emasculation, when it could be seen as the awakening of female power through symbolic menstruation or something…

TH: Absolutely, that’s what that scene’s all about. The superstructure of mythology is so deeply embedded in the human subconscious that we don’t even realize it’s working within us. I’ll give you a prosaic example. The cereal that we eat comes from the goddess Ceres, who was the Roman version of the goddess Demeter, goddess of grain. And so in eating that cereal, we pay homage to the goddess of grain. Whereas in the monotheistic superstructure, the idea of female divinity is completely forbidden—it’s a crime. That moment of orgasm, that moment when the human body is at its peak in terms of the experience of pleasure, that’s when you come face-to-face with Aphrodite, the goddess of love, the goddess of orgasm—that joy, that extraordinary physical joy—which is forbidden in this system because Aphrodite doesn’t exist here [pointing to monotheism on the diagram]. Which is why sex is so fucked up in this society. You’re not supposed to do it. It’s forbidden. Nobody does it. It’s only for recreative purposes. You have two kids, and that means you’ve only fucked twice in your life. How sick can you get? When the human body is just so filled with these lovely, lovely, lovely liquids—tears and perspiration being the least of it, you know?

I always dreaded going to heaven. When we were kids and we were being taught by these missionaries and these nuns, the charts showed that all the white people went to heaven and all the brown people went to hell. Ever since then I didn’t want to go to heaven. In heaven you can’t smoke, you can’t drink, and you can’t have sex—in hell you can do all of them, all of them. If there’s a party anywhere, it’s in hell, not up there with the one male god who says all the way through the First Testament, “I am the only God and I’m a jealous God, and anyone who worships another god will be destroyed”—now who else talked like that in 1930s Germany? To me, monotheism is a form of fascism. It’s brutal. And too many people have had brutal fathers who’ve had masculinity beaten into them. The prisons of our country are filled with the victims of that system. The prison system of our country is filled with the products of abusive marriages of that ilk. Anyway, if you do what I say, you’ll go to heaven and you’ll spend eternity on your knees telling god how perfect he is because, for some reason, even though he’s supposed to be omniscient he has to be told a thousand times a day how great he is. Down here in hell you’ll spend eternity on your knees doing something one hell of a lot more fun. One hell of a lot more interesting. And that’s where I’m going.

But those men who embrace their femininity—who cook, who make cakes for their wives and children, all that kind of stuff—those are the men who are contributing to the elimination of the very dangerous system of monotheism and to the revitalization and the renaissance of female divinity and pantheism. If anything ensures that the planet survives the next century, it’ll be pantheism not monotheism, the circle not the phallus. So time is of the essence, in that sense. And Aboriginal literature couldn’t have come at a better time.

SM: What do you see as the role of literature and performance and dance and music in this mythological revolution?

TH: The arts, it’s a medicine. It’s a salve that society needs. Imagine a world without music, without dance, without theatre, without colour, just a black-and-white world of he and she. And who adds the colour? All the colours? The other genders. And you have to have that, or else you just die. Life wouldn’t be worth living.