For me, middle school was one never-ending game of dodgeball. Back in elementary school, I’d frequently been the victim of friendly fire. The ball always seemed to miss its actual target and hit me, no matter where I was on the circle.

Today, school started out kind of like that.

Out in the lobby, before the first bell, Morgue MacKenzie snagged me by the arm as I tried to pass his hulking frame. He looked down at me and said, “Quarter.”

Morgue was standing in front of a Juice Express Refreshment Kiosk, the capitalized first letters of the words glowing a bright purple over his head. He needed an additional twenty-five cents for a can of Agra Nation® Energy Blaster. I dug in my pocket and gave him the change.

“Why do you let him do that?” asked Freak when I joined him a few moments later.

“He’s twice my size,” I said. “And he never asks for more than he needs.”

“Next time, tell him your money is radioactive.”

“Why would he believe that?”

“You live on the edge of Hellsboro.”

“Hellsboro isn’t radioactive.”

“Morgue doesn’t know that. He’s one of those people who thinks Hellsboro is the work of the devil. I’ve heard him say he’d never set foot in it. If he thinks your money has something to do with Hellsboro, he’ll go bother somebody else.”

I decided Freak might be right.

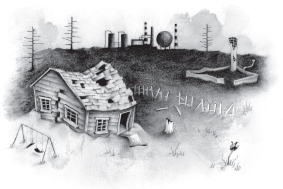

Hellsboro was the name the Cheshire newspaper had given to our local underground coal-seam fire. Hellsboro had turned eight hundred acres on the west side of town into a treeless, lifeless wasteland. The fire had been burning for twelve years. It could burn for a hundred more, or until all the underground coal was consumed. Coal-seam fires were almost impossible to put out. Ours had pretty much stopped spreading, although a small tongue of it had stuck itself out under Breeland Road that past summer and caused a sinkhole.

At Hellsboro’s center was the abandoned Rodmore Chemical plant. Rodmore had once been a big employer for the town of Cheshire. Now it was like a cinder-covered castle in the middle of a burned-down amusement park. It had been closed since the fire started. Nobody went there anymore. People said the plant was even more dangerous than the fire that surrounded it.

The fire had made almost all of the houses in the nearby Sunnyside housing development uninhabitable. Only three families still lived in the development: Freak’s, Fiona’s, and mine. We had to walk several miles to get to the next inhabited place, if you didn’t count Old Man Underhill’s.

Most people in Cheshire feared Hellsboro. It hadn’t stopped them from renaming the high school football team the Hellions or the middle school team the Devils (a faded banner in the gym says we used to be the Cheshire Cats) or having an annual dance at the town hall called the Hellsboro Hop. But nobody went near the actual fire zone. The mayor joked that it was a good way to get a hotfoot. If reminding Morgue MacKenzie how close I lived to Hellsboro would get him to leave my money alone, I would try it. As soon as I got up the nerve to tell him.

In English class, we got our spelling tests back. The one word I got wrong was renaissance. I put in too many n’s. Renaissance means rebirth. I asked Mr. Hendricks, our teacher, why, if it meant rebirth, we didn’t just say rebirth, which is easier to spell. This led to a long lecture from him about how important it is to have a large vocabulary. Mr. Hendricks started throwing around words like quintessential, lexicographer, and hyperdiculous. Everybody blamed me for the lecture, of course. Just as, the previous week, they had blamed me for the pop quiz on Tom Sawyer, just because I’d shown up wearing suspenders. I was used to it.

At the end of class, Mr. Hendricks admitted he had made up the word hyperdiculous. He wanted to see if any of us would raise our hand and ask him what it meant. None of us did. We were, I could tell, a constant disappointment to Mr. Hendricks.

It was during lunch that the school day really went off the tracks.

There was another flash mob.

It happened shortly after Rudy Sorkin slipped on a string bean. His feet went out from under him. He fell on the floor with his lunch tray, and we all applauded. Then the applause cut off in mid-clap. I brought my hands together two more times into the dead silence and then caught myself.

“Uh-oh,” I said to Freak.

“Not again,” he said, rolling his eyes. The last flash mob had been only a week earlier.

Almost everybody stood up, except Freak and me and two or three other kids. But the majority of the lunchroom, including Fiona, who was two tables away, and all the adult monitors and the food-service ladies, turned and faced the window.

“That’s different,” I said.

“Yeah,” agreed Freak. “Last week they faced the wall.”

Everybody clapped twice. Then they crossed their hands in front of their faces, tugged on their earlobes, put their hands on their hips, and launched into an ear-splitting performance of the song “Oklahoma.” For two and a half minutes everybody assured us that Oklahoma was doing fine, it was grand, and, while it might not be terrific, it was certainly okay.

Then everybody sat back down, finished their round of applause for Rudy Sorkin, and picked up their conversations right where they had left off. The lunchroom filled instantly with its usual noise.

The first time this had happened, over a year earlier, it had been scary. We had been new to the school then, so we thought maybe it was a middle school ritual that no one had let us in on. That time, everybody had stood, faced the kitchen, and sung about raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens. And it turned out it hadn’t been just the lunchroom. It hadn’t been just the school. It had been the entire surrounding town of Cheshire. Or 90 percent of it. People had pulled their cars to the side of the road, gotten out, and sung.

I immediately decided it was alien mind control.

The next day, the newspaper said it was a flash mob. According to the report, everybody had been texting one another on their cell phones for weeks ahead of time. They had chosen what direction to face. They had picked out the song. They had agreed that everybody would perform together, no matter where they were or what they were doing, at exactly eleven forty-eight on the morning of September 28. After it was over, everybody who participated would deny having any memory of having done it if they were questioned by any nonparticipants. It would all be part of what the paper called “a grand and glorious lark.”

To me, it seemed like a grand and glorious waste of time.

After that, it kept happening. Freak and I learned to expect a singing flash mob every eight to ten weeks. Sometimes, there was even a dance step or two.

Fiona was good at it. She followed instructions perfectly, and after each flash mob she always claimed she couldn’t remember doing anything out of the ordinary.

I started to feel left out. Since Freak and I didn’t have cell phones, we were out of the loop. We had almost gotten cells the summer we graduated from elementary school, when the Disin Tel store opened on Coal Avenue and had offered an irresistible limited-time promotion.

LISTEN TO DISIN! the cleverly rhyming banner in front of the store had proclaimed, going on in smaller print to offer free phones to every family member past the age of ten in any family that signed a one-year contract. It was so inexpensive that practically every family in town took advantage of the offer. Then Freak’s father accidentally dropped his new phone down the garbage disposal, and he took Freak’s phone to replace it. And my aunt Bernie pulled mine out of my jeans after they’d gone through the wash. I’d had the phone for one day.

“Even if we had cells, would we be doing this?” demanded Freak, after everybody had finished singing “Oklahoma.” “How is it possible that there isn’t one kid here with a cell who doesn’t think this is totally stupid? Not a single person can decide to just sit it out? And why are they doing it again so soon?”

“Maybe the Elbonian overlords are stepping up their plans for world domination,” I said, adding a couple of potato chips to my cheese sandwich. I like a sandwich with crunch.

“The Elbonian overlords?”

“Weird foreign people in the Dilbert comic strip.”

“Why would you read Dilbert? It’s about office workers.”

“Someday I figure I’ll work in a cubicle. That’s what middle school is training us for. I think there’s some serious mind control going on here.”

“You mean the flash mobs.”

“That, too.”

Freak scowled.

“You can’t be right,” he said. “This is weird.”

“No, it’s not,” I assured him.

“It’s not?”

“No,” I said. “It’s hyperdiculous.”

It was the only word that described it.