1

1

“ONE … TWO … three … four …” Dakota said, breathing in slow, steady breaths, air crawling gently, obediently, through his mask.

“Five … six … seven … eight …” Riley continued.

Dakota remained calm, focused, as his eyes sent an unspoken message to his younger brother.

Keep counting, they commanded, his smile, provoking and competitive. Eyes locked, a silent understanding between them, Dakota and Riley continued to count, a fight against the other’s will.

“Nine … ten … eleven …” Dakota continued.

They weren’t on the football field, or racing quads, or preying on the same seven-point deer in the woods. This wasn’t a game of baseball or basketball or “Underwear Olympics” that they played nightly with their father, Henry, in the hallways of their cozy, Cabot, Arkansas, home.

This time, Dakota and Riley were on the same team, fighting the same fight—but it was in their nature, their blood, to keep the competition alive, even during a transplant from one brother to the other.

“Twelve …” Riley nearly whispered into his mask, eyelids pushing down against his mental strength.

Keep counting, he demanded silently. He couldn’t let his brother win.

Dakota had always been the kid in track and field who pulled ahead of the other runners and stayed that way past the finish line. He was the star of every team—scoring the most goals, the highest points, the greatest touchdowns. He was a born athlete, a natural leader who was used to winning, addicted to victory.

Not today, Riley thought, but his words were floating away, leaving him.

“C’mon boys, keep counting,” he heard from one of the doctors, whose voice, encouraging competition, became whispers, clouds in his mind.

Dakota’s face, his stark blue eyes that were once paired with hair as fiery as his spirit—hair now gone—remained still and just as strong as Riley faded into the darkness.

“Thirteen … fourteen …” Dakota continued, but once he knew Riley was completely under, he closed his eyes, sinking heavily beneath the wave of anesthesia flowing through his body, letting it carry him away.

Dakota and Riley lay side by side, in silent peace, as the process began—the process to save Dakota’s life.

2

2

A year and a half earlier, Dakota ran beneath the white glow of towering stadium lights, which pushed against cold, black air, lighting up the small, all-American, football-loving town of Cabot.

Bleachers surrounding the field rumbled beneath pounding feet, shook with excitement, as eleven-year-old Dakota and his team, the Green Bay Packers, took on the undefeated Dallas Cowboys in the last game of the peewee championship.

A cool, November breeze carried the scent of fresh-cut grass and powdery chalk into the stands, where dozens of familiar faces screamed and cheered for their boys, who, for that one night, were NFL players in the Super Bowl.

Dakota was on fire. His cleats tore into the earth, heart pounding with every step, as he made every pass, every tackle, every play with perfection.

He had grown up on the sidelines, mapping out plays in the dirt for Henry, loosening the hillsides playing one-on-one with Riley. He spent years studying his father’s coaching technique, memorizing tactic, internalizing strategy, until Henry, who had played football for Arkansas Tech University and was an assistant coach for the Cabot High School football team for the past fourteen years, determined he was old enough to play.

The night of the last championship game, Dakota was unstoppable. He scored two touchdowns before the ball, leather spinning in a perfect spiral, landed in his arms at the twenty-yard line. He looked up from under his helmet, eyes of a cat before pouncing, and ran with the breeze down the length of the field, zigzagging, dodging, sprinting, until he was safe in the end zone.

He smashed the ball hard onto the ground, letting it fly, while his teammates stormed and the crowd went wild. They had won the game and the championship. At the end of the night, Dakota and his fellow Green Bay Packers smacked high fives into the crisp air and wrapped their arms around their hard-earned trophy.

“You played your heart out, buddy,” Henry said, hugging his son after the game. “Three touchdowns!”

“Yeah, that was an awesome game!” Dakota shouted, and Henry reached for Dakota’s forehead to find it warm, clammy.

“How are you feeling?” he asked.

“Fine, Dad,” Dakota said.

“Are you sure?” Henry asked, concerned.

It was hard to say whether the fire beneath his hand was fever or the game’s intensity. He let it fall from his son’s face, remembering the strep throat diagnosis Dakota’s doctor had given the week before.

Antibiotics she prescribed were not working, and Dakota’s fever was persistent. Until the big game, his body had been weak, lethargic, but that night, Henry and Sharon, Dakota and Riley’s mom, saw the first sign of energy, the real Dakota, that they had seen in several days. They saw his face crease with determination as he sprinted down the field, his spirit as strong as ever.

During the weeks following the game, Dakota’s walk gradually became slower, his skin whiter. Sharon tried to keep things as normal as possible for her boys as Christmas approached—a smile on her face, traditions alive—but her insides ached with every forced smile, every attempt at normalcy.

Why are the antibiotics not working? Why is he so weak? she questioned, the thoughts heavy on her mind, the answers unknown.

They baked cookies together and delivered them to retirement homes as they had every year, watched the town’s annual Christmas parade, attended their church’s cantata, and participated in their schools’ holiday programs. They put up their Christmas tree, hung ornaments, decorated their home, enjoyed the peace of freshly fallen snow, and counted the days until Santa arrived—but rather than a jolly heart, Sharon’s was heavy.

Her mother’s intuition, an internal knowing, grabbed at her stomach, made her ache with worry.

His bruises are probably from playing football, Sharon told herself as she stayed up late at night researching the symptoms her son had shown for weeks, but she couldn’t convince even herself. The symptoms were too close, too familiar.

She read: “Leukemia—headaches, lethargy, bruising.”

A few hours after Christmas Eve dinner, Sharon stood in the kitchen with her older sister, Regina.

“Oh, my goodness, what will I do if my Dakota has leukemia?” she sobbed into her sister’s arms.

The rest of their family was on the other side of the kitchen doors, laughing, celebrating, opening gifts, while Sharon remained in Regina’s embrace, their tears flowing together, dripping down linked arms.

“Oh, Sharon,” Regina managed. “I’m so sorry, I just don’t know what to say.”

She didn’t want to give Sharon false assurance with “It’s going to be okay” or “I know everything will be just fine” because, the truth was, she didn’t know. Instead, Regina hugged her tightly, feeling her sister’s pain deep within her own gut—a feeling of absolute desperation.

“I just don’t know what to say,” she cried, almost whispered, into her little sister’s ear.

3

3

The next night, at their church’s Christmas program, Dakota’s pediatrician, Dr. Ruth Ann Blair, stood beside Sharon in the choir loft, getting ready to sing their first song. Dakota walked down the aisle, toward the front of the church where he always sat, and as he took his seat, Sharon leaned over and whispered to Dr. Blair, “Does Dakota look pale to you?”

Friends and family agreed that, over the past few weeks, his skin had turned the color of gray sheep’s wool, but when Dr. Blair’s eyes studied him from a distance, squinting with concentration and then with concern, Sharon had her answer. That dark answer, lurking behind every thought, creeping through every part of her mind, was stepping into the light, standing directly before her.

“Yes, he looks pale to me,” Dr. Blair confirmed gently. She had diagnosed him just a few weeks before with strep throat and could see that the antibiotics were not working. “Have him come see me after Christmas.”

The music started, the soft, sweet sound of praise and rejoice. Sharon stared at her songbook and then blankly into the eyes of the congregation, and she knew hers were empty and deeply sad.

She glanced at Dakota, and the words, her voice, flowed heavily, resiliently, around the heavy lump in her throat. She made it through the cantata as she had the rest of the Christmas season, with a forced smile and a sickened heart.

“Mama, can we go home to play with my new toys?” Dakota asked the next day. It was 1:00 p.m. on Christmas afternoon, and the family had just finished eating a big, traditional meal at Papaw’s, Henry’s father’s, home.

The adults had gathered in the living room, drinking coffee and squeezing dessert into their stuffed bellies, while the kids played with their new toys. Sharon looked down at her son, who loved playing with his cousins, especially on Christmas, and smiled as best she could.

“Sure, baby,” she said, keeping her tears tucked away.

“Jingle Bells” and “Deck the Halls” swirled softly around the car on their drive home as Sharon glanced at Dakota, whose head was resting on his seat, eyes opening and closing slowly.

“Mama, thank you for a wonderful Christmas,” he said, looking at Sharon as she kept her eyes on the quiet, open road, not a soul around.

She looked at him with smiling eyes full of tears that she quickly blinked away when she turned her head back to the road.

“This was the best Christmas ever,” he added.

She couldn’t look at him again. She stared at the highway, reached a hand over, and squeezed Dakota’s knee, pursing her lips into a half smile, just in case he was looking to her for a sign that everything would be okay.

She knew this wasn’t his best Christmas ever. In her mind, the piles of toys in their trunk should have made him feel better. The distraction of family, the excitement of the holiday, should have been enough, but it wasn’t.

It was Christmas, and he wanted to go home and rest.

“You’re welcome, baby,” was all Sharon could manage, the lump in her throat suffocating.

The sweetness in Dakota’s voice, the kindness in his eyes that afternoon, would live inside of her forever. She believed it was his way of telling her that, somewhere, deep, deep down, he knew something was terribly wrong.

They both did.

4

4

“The doctor needs to speak with you,” a nurse said the next day at Dr. Blair’s office. “Dakota, sweetie, come with me to watch some cartoons.”

Sharon didn’t know this nurse, but even the eyes of a stranger could not conceal such a dark, unwanted secret.

God, this can’t be happening, Sharon pleaded. She wanted to stay right there, in that moment, before another word was spoken. She clung to those last few seconds of not knowing, of having an ounce left of hope. She wanted to live in that moment forever.

“Sharon,” Dr. Blair said when she walked into the room. She spoke as gently as she could, and Sharon closed her eyes. There was no easy way to say it. “Dakota’s white blood cell count is through the roof. I’m afraid he might have childhood leukemia.”

There they were: the words she knew were coming. Dr. Blair wrapped her arms around Sharon as she slipped through them.

“No, no, no, no, no …” she sobbed.

Maybe if she said it enough times, if she squeezed her eyes tight enough, shook her head back and forth hard enough, this would all go away.

“This can’t be, this can’t be …” Sharon cried.

Dakota doesn’t have cancer, she told herself, hardly able to even think the word.

Her body, her mind, numb.

She couldn’t live without Dakota, so the only option was to beat it.

Dr. Blair immediately sent her, Henry, and Dakota to Arkansas Children’s Hospital for blood tests and draws, and that day, it was confirmed. Dr. David Becton, the hospital’s chief oncologist, gave the news to Dakota in a way a child could understand.

“You have leukemia,” he said to Dakota, who suddenly turned from a growing eleven-year-old back into Sharon’s baby boy.

She watched as her son studied the doctor’s face. She wanted so desperately to wrap him in her arms, to protect him from the world, from cancer, from the rest of what the doctor was about to say, but she knew she couldn’t. This was in God’s hands now.

“Leukemia is a type of blood cancer,” Dr. Becton continued, “and the bad guys are fighting against the good guys in your immune system. We are going to annihilate the bad guys with chemotherapy, which we will start you on tomorrow.”

He didn’t tell Dakota that he suspected Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML), one of the most destructive, hard-to-beat cancers rarely found in children. He wanted to keep it simple but real.

“It’s going to make you sick,” he said. “And …” Dr. Becton paused.

He looked at Dakota’s beautiful, thick red hair and added, “Your hair will come out.”

“Son …” Henry said when Dakota started to cry. As his father, he needed to stay strong, even if his insides were falling apart. Henry placed an arm around Dakota’s shoulders and spoke his language. “We are in a marathon, and we are going to cross the finish line, and then we are going to keep running and running. We’re gonna keep our eye on what’s ahead, on the finish line.”

Dakota, blinking tears down his lightly freckled cheeks, looked at his dad and nodded.

“Will I ever play sports again?” he asked, turning his reddened face to Dr. Becton.

He smiled at his little patient.

“Yes, you will.”

5

5

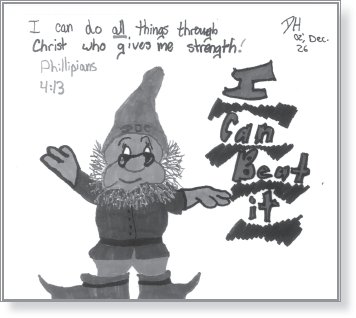

Dakota was admitted to the hospital that day, and two hours after he got settled into his hospital bed, a Child Life volunteer at the hospital brought Dakota a stuffed toy, Doc, one of Snow White’s Seven Dwarfs. Dakota placed the doll on his lap, making room for a sheet of paper, and began to draw.

Slowly, meticulously, he sketched an outline of Doc’s body, then filled in the details of his face. Beside Doc, he wrote, “I can beat it,” and at the top of the page, added, “I can do all things through Christ, who gives me strength—Philippians 4:13.”

Sharon’s eyes welled up when she saw the picture. She immediately thought of the time Dakota had brought his small New Testament Bible to show-and-tell in kindergarten.

Dakota drew this picture the day he was admitted to the hospital after being diagnosed with cancer.

“How many of you go to church?” he had asked his classmates, holding the Bible high into the air. A few kids raised their hands, most didn’t, some looked around, uneasy. His teacher, Mrs. Melder, who attended the same church as Dakota and his family, stood in the corner, watching, smiling.

“Well, if you don’t, you should consider it,” Dakota finished and sat down.

Even with news of cancer and within the confining walls of a hospital instead of a football field’s freedom, his faith was still alive, and so was his will.

The next day, after Dr. Becton confirmed to Sharon and Henry that Dakota had AML, a bag of red chemotherapy, the meanest, most intense and aggressive form of treatment, hung beside Dakota, dripping its life into his veins.

“I will beat this,” Sharon read again, and she pictured him at two weeks old, lifting himself with his arms when most babies couldn’t even lift their heads.

He’s a fighter, she thought, suddenly seeing the significance, the irony, of his name—Dakota, Native American for “Strong Warrior” in the Sioux tribe—she had always been told.

After two weeks of chemo, Dakota was in full remission. It was the end of January, but to make sure every cancer cell was gone, defeated, doctors continued his intense protocol for the next four months.

Most treatments kept him in the hospital for a week at a time before he was able to go home, where Sharon, his “codoctor,” administered natural remedies she had researched to keep him fighting—Shiitake mushrooms to build his immune system, oxygenated water to supply his blood, green barley for its natural healing ability, and milk from a local goat farm for his bones.

After learning that sugar can potentially feed leukemia cells, she kept Dakota on a low-sugar diet, had him take as many herbs and vitamins as possible, and eat fresh, raw vegetables to build up his weakened immune system. These remedies seemed to keep away the fever and infection that many leukemia patients developed, but Dakota still had good days and bad—days when he couldn’t get out of bed, days he couldn’t keep anything down, quiet days of sickness and sleep.

One morning during a hospital stay, Dakota slept soundly, peacefully, as the sun rose and poured in through his window, crawling slowly across his face and onto his pillow, revealing the undeniable sign that they were actually going through this, cancer’s most irrefutable presence—a beautiful lock of strawberry hair lay, detached, inches from his head.

This can’t be! Sharon wailed in her mind, silent tears and whispered sobs escaping her uncontrollably. This isn’t right!

It didn’t take long before every strand, falling out by the handful, was gone.

When Dakota saw the sympathy, the sadness, in Henry’s eyes, he teased, “Daddy, you always said hair was way overrated.”

Dakota looked at his father’s balding head, sensed from his smile that he was warming Henry’s broken heart.

“Now I look like you!”

He was easing Henry’s pain, softening the severity of his situation, as he had tried to do from the beginning when he said with determination, “I can beat this.”

During hospital stays, Dakota had good days and bad. On good days, when chemo would release its firm grip, even momentarily, Dakota would roam the halls and even leave with doctors’ permission to go to the movies, race go-carts with Henry and Riley, and make visits to Toys “R” Us, before returning for more treatment.

“I’ll be in here!” he whispered to his parents loudly one afternoon on a good day, crawling into the medical closet of his hospital room.

He had filled two syringes with apple juice and closed the door behind him, waiting patiently to hear the voice of one of his nurses.

“All right, Dakota …” she said before he threw open the door, aimed and squirted the juice, his laugh filling the room, the halls, the lives of other families nearby who needed the sound of a child’s laughter.

Dakota had pulled his first prank at six years old while visiting Sharon’s mom, “Mama Lamb,” on her farm at the end of a dirt road in Delight, Arkansas. Mama Lamb’s tiny washroom was in the corner of the barn, the clothesline outside. It was a breezy day and clothes flapped in the wind as Dakota helped hang them with wooden pins.

When Mama Lamb entered the barn, darkened without the help of the sun peeking through its door, Dakota used all his weight to swing it shut, locking her tightly into that dim, smelly barn.

“Dakota, if I ever get a hold of you, I’m gonna wear you out!” Mama Lamb shouted, and Dakota chuckled, just the way he did when he squirted apple juice at his nurses or put Riley in his place in his hospital bed, shocking the nurses when they’d pull back the sheets.

On days when Dakota wasn’t feeling well, when it took all of his energy to get out of bed, he would pile games, books, puzzles, and video games from friends, family, and church members into the hospital’s red wagon—the wagon used to discharge kids once they got well—and drag his IV pole with its hanging bag of fluid to distribute the gifts to the other sick children on the third floor.

Dakota visited a two-year-old little girl with leukemia down the hall one day and told his parents about how happy he had made her. He imitated her smile, mimicked her laugh, reliving the girl’s joy when he handed her a “Dora the Explorer” balloon. “Oooh, Dora! I love Dora!”

He created smiles with jokes, laughter from words, and hope with his presence in the hallways coming and going from his hospital room.

6

6

Dakota remained in remission but struggled against the tight grip of chemotherapy, its cruel demands, relentless misery, until May, when he received his final treatment and a “last chemo party” in the oncology department’s outside courtyard where he was showered with love and gifts from friends and family.

The courtyard’s water fountain, its colorful flowers and small wooden bridge, had been a place of escape, of make-believe, for Sharon and Dakota throughout his treatment. They had left the doors of the cold, sterile-smelling hospital every day to enter this place of peace, where they shared their thoughts, sat in silence, read books, and made plans for when Dakota came home for good.

Sky-high glass windows with peeking patients surrounded them, reminding them of where they were—in the middle of this nightmare. But in those moments, in their minds, they had left the hospital and entered the outside world.

The day of the party was a day when the door opened, even just the slightest bit, to that outside world—that world filled with family and friends and a future without cancer. Dakota had undergone his last treatment that morning, and in his twelve-year-old mind, “last” meant forever. But for Sharon and Henry, “last” signified only a moment in time—the “last” treatment in a month, a year, a lifetime? They didn’t know.

All they knew was they had this moment, this very special moment that brought Dakota, weak and sick from chemo, out of his hospital room and into the sunshine, where six of his best friends gathered around and performed a humorous jingle they wrote about Dakota and his love for sports and life.

Bless his heart, Sharon thought. He just doesn’t feel good.

She could see the misery in his face, the weakness in his eyes, but, as always, the joy he had in his heart, the hope and happiness he felt in his soul, lived in his smile, which reached from ear to ear as he received gifts and hugs from his friends, his family, his doctors, and his nurses.

A hole of uncertainty ached in Sharon’s heart as she watched her son’s happy but pained face, and while the reality of possible relapse would inevitably live in the back of her mind, she decided to view this moment as a milestone, the first step in possibly beating cancer forever.

The peace that surrounded them that day—their family and friends, the bridge and the trickle of the fountain, the place that had provided hours of respite for Dakota and his mom—would soon become a memory for them to hang on to. A memory of the place they left, the door they stepped through, to re-enter life.

When the party was over, that’s where Dakota went, to the outside world, the real world—the world he had wanted to rejoin for the past five months. He had the entire summer before his seventh-grade year to let his body heal from the damages of chemotherapy. After a few weeks, Sharon, who hadn’t left Dakota’s side since December, knew she needed to let go.

She, Henry, and Riley drove Dakota to church camp at Camp Wyldewood, about thirty miles away, where she and her siblings had spent their summers growing up. Dakota walked beside them, bald head held high, a proud cancer survivor. The camp nurse was aware of his condition and would administer his doctor-prescribed medicine, as well as Sharon’s natural remedies, during the week he was gone. She felt confident that he would be in good hands but said a little prayer anyway that God would take good care of Dakota while he was out of her care.

Giddy with excitement and anticipation of long-awaited freedom, Dakota eagerly followed his parents to the cabin where he would be staying and listened as they shared Dakota’s story with his bunkmates. Certain that church camp was the safest place for their son to enjoy himself without getting teased for having a bald head, Henry and Sharon wanted to make sure that the other kids understood and treated him kindly—treated him the way they would treat any of the other children at camp.

Sharon set up Dakota’s bed with his pillows and blankets from home. After he placed his favorite stuffed animal, a black Labrador named Trouble, on top, Sharon smiled and hugged her son, embracing him with all the love inside of her. She saved her tears for the car ride home, focusing, in that moment, only on Dakota’s happiness and his freedom, the greatest gifts she could ever receive.

When they returned a week later to pick up Dakota, he ran from his cabin, tearing down the dirt trail, a big smile leading the way, and skidded to a dusty halt in front of his parents.

“I have hair!” he yelled before wrapping his arms around them. The fuzz tickled Sharon’s chin as she embraced him with all her might.

He has his life back, she thought, tears dripping into her smile.

When they returned home, Dakota spent every day that summer playing football and basketball in their front yard with Riley and the other neighborhood kids. He dribbled and passed as though he had never been sick and chased runaway balls down the street and into the woods. He returned to school that August and tried out for basketball, making the seventh-grade team.

Dakota played with all his might, with every ounce of vigor as any other player on the court. The first point he made that season was a free throw. Standing at the foul line, looking down at the ball intently, he dribbled in place, looked up at the hoop with determined eyes, and …

Swoosh.

The crowd erupted, Dakota shot a smile at his parents, and Sharon dropped her head into her hands, sobbing right there in the stands, right there in the middle of the wild crowd.

She didn’t care. Her son was back.

Dakota was excelling in all of his pre-advanced placement classes, learning as much as he could to pursue his dream of becoming an engineer, a missionary, or the President of the United States. He thrived in math and had a passion for history, which started as a child when he spent hours creating homemade Civil War and John Wayne movies with neighborhood kids. Dressed in boots, holsters, and bandanas, Dakota would use his parents’ camcorder to film scenes with his friends, rolling handwritten credits at the end on rolls of paper towels. Dakota was the star of every film—always the toughest soldier, always John Wayne, always the last one standing.

Two weeks after the seventh-grade basketball game, Dakota relapsed.

Sharon could feel it in her bones on the way to his routine checkup. The anticipation of every appointment sat heavy in her chest, nestled deep into her heart, but this appointment was different. Dakota’s color wasn’t quite right. It hadn’t been for two weeks, and his energy had dipped with his spirit.

“I’m afraid to tell you this,” said Dr. Becton after returning to the tiny room where Sharon and Dakota waited, hours after he drew Dakota’s blood. Every tick of the clock, every minute it had taken to comprise those hours had settled miserably into Sharon’s gut, second by second, and she knew what was coming. She knew that any sign of cancer, any glimpse of its existence, required multiple tests, trips to pathology, second and third opinions—required time.

After those long, torturous, unsettling hours, Dr. Becton’s eyes, usually radiating strength and confidence, looked down, troubled, before looking up at her, this time strikingly sad. “The leukemia has returned.”

Sharon’s heart folded over itself, fell into the abyss of the pit in her stomach. The pain of it pounded into her chest so violently that everything else went numb—her arms, her legs, her mind. Dakota dropped his head to look at the floor, and Sharon wrapped him in her arms.

“We’re going to get through this again, son,” she reassured him. “We’ll do whatever it takes. We’re going to get through this as a family.”

You’re the mother, she thought to herself. Keep it together, stay strong. Save your tears for later.

When Dakota called to tell his father the news, Henry closed his eyes. He pictured the bruises on Dakota’s knees—bruises he had convinced himself were from kneeling on the basketball court during season pictures, bruises that could indicate the return of cancer, bruises he wished he could pray away.

“I hate this, Dad,” Dakota said. “But Dr. Becton said we can beat it again.”

“You bet, son,” Henry said, his voice unwavering. “We will beat it again.”

And he already knew how.

Nine months earlier, when Dakota was in remission from cancer but still undergoing chemo, Henry, Sharon, and Riley had all been tested as potential bone marrow donors—for the possibility that cancer would return, for this very moment.

It was Valentine’s Day 2003 when Dr. Becton skipped into the room where Sharon sat, waiting for results. He was barely through the door before nearly shouting, “Riley is a perfect match! If we ever need him, if it ever comes to that, he may be Dakota’s lifesaver.”

Lifesaver.

Sharon let that word, with all its hope, all its promise, rise up and float there. She closed her eyes, breathed out, silently thanking God. It was no coincidence to her that on this day of love she found out her son, Riley, could possibly give the gift of life to his brother.

She couldn’t get to Riley’s school fast enough, where she knew he was celebrating this very special day in his fourth-grade class, opening tiny, stuffed envelopes with messages from Scooby Doo and Elmo, eating heart-shaped candies etched with “I love you” and “Hug me.”

She led him by the hand and into the hall, then hollered, “Riley, we’ve been given the greatest gift of all today! You’re a perfect match for Dakota!”

Riley’s face beamed, radiating happiness, but he remained silent in shock as his mom squeezed him tight, grabbing and kissing his face all over.

Finally he spoke.

“Let’s go!” he shouted, leading Sharon back into his classroom, where he told his teacher and made an announcement to the class. The words cancer and transplant probably meant nothing to that room full of fourth graders, but Riley’s excitement, the smile that stretched across his entire face, sent his classmates out of their seats, their hands pounding together, their cheers filling the halls.

7

7

Cancer had made its return, but before Riley could save Dakota’s life, Dr. Becton had to get him back into remission, at least partially.

As before, Dakota had good days and bad. And while his body was tired, weakened by such an intense first round of chemo, he resisted the treatment’s misery and remained hopeful and spirited. His hospital stays were longer, darker than before, but he still made rounds to eagerly awaiting children, still tricked his nurses with apple juice-filled syringes.

After just a few days, two Child Life volunteers made a visit to Dakota’s room and told him about the Make-A-Wish Foundation—told him that he could ask for anything in the world, seek anything in his heart’s desire, and his wish would be granted.

Anything—that word would stretch any twelve-year-old’s imagination to its limit.

A trip to Australia, Dakota thought. Meeting Brett Favre from the Green Bay Packers … No, the memories will fade.

Sharon and Henry leaned forward, wanting desperately to read his mind, to hear his wish.

“I want something that will last,” he finally said.

Dakota closed his eyes, remembering a moment just a few weeks before, when he was living a cancer survivor’s dream—remission—still living his answered prayer.

It had been a brisk, October morning when he, Riley, Henry, and Henry’s father, Papaw, rode their ATVs through the silence of the woods, the sun still resting peacefully beneath the horizon, the freedom of the wilderness stretching endlessly ahead, dark and adventurous.

It was the first day of deer hunting season, and at the ages of ten and twelve, Henry decided it was time for Riley and Dakota each to have his own deer stand. Hunting from the time they were toddlers and shooting with their own guns starting at six and eight, their senses were trained, their instincts polished.

They were ready.

Riley’s eyes looked up the length of an oak tree at his deer stand—one of the tallest he had ever seen—placed, from his point of view, sloppily up top. A steep, skinny, worn ladder led toward the sky and into the stand, which offered no place to sit.

“I don’t want to go up there,” Riley said, keeping his wide eyes on the stand.

They had just come from looking at Dakota’s stand—300 yards away—a shorter, more solid-looking tree house–type structure with a chair.

Dakota looked at his younger brother.

“Papaw, Riley can have my stand.”

They got settled into their own stands, sat, and waited in the silence, the serenity, of the forest. Endless stars dotted the black sky while a light breeze danced peacefully through the trees, the only sound for miles. After fifteen minutes, a sudden bang cracked that silence, its echo a warning to all wildlife.

“He got a deer,” said Henry, who was about 300 yards away.

Riley also heard the shot.

“It’s a seven-point buck!” Dakota yelled, hovering over his fallen prey.

He smiled in his hospital bed at the memory and decided in that moment what his wish would be.

“I wish to have an ATV,” he said proudly.

Not only was he choosing something he knew his parents could not afford to buy for him, he was choosing a wish of freedom, of independence, of adventure. He would use it to maneuver the thick woods, haul animals, explore.

He brainstormed aloud all of the desired features for his ATV—its speed, capability.

“We’ve never met anyone who knew what he wanted quite the way you do!” said one of the volunteers, laughing, charmed.

In between IV drips, blood draws, chemo, trips home, and back to the hospital, Dakota was attached to his laptop, researching every detail, every function, of his new, personalized ATV. Nurses continued to poke and prod, change medicines, switch arms for IVs, but he would work with them, using his good arm to run the mouse, peek around them politely to see the computer screen. He never stopped researching—color, speed, engine size, brand, model, accessories.

His thoughts went from leukemia—from chemotherapy and test results and transplant—to riding the ATV through the forest, hunting, life after cancer.

Dakota settled on a John Deere Gator HPX 4 × 4—it went one mile an hour faster than the rest.

8

8

When he went into partial remission—enough for a transplant—it was time to get Dakota and Riley to Houston, Texas, where the bone marrow transplant would take place. Obtaining doctor’s approval of Dakota’s wish, getting every detail of his special order just right, took a significant amount of time, which volunteers with the Arkansas Make-A-Wish chapter suddenly ran out of when they learned that Dakota was in partial remission and leaving town very soon.

Knowing the family was heading to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston on Saturday morning, it was a small miracle that the chapter received the Gator in time. They quickly made sure it had the correct hood, windshield wipers, doors—every detail—before covering it with bows and balloons and taking it to Dakota’s home Friday night.

Sharon and Henry, who knew it was coming that night, hosted dinner for a house full of loved ones, their closest family and friends, telling Dakota they were there to see him off before their eight-hour drive to Houston the next morning.

The smell of wholesome Southern cooking lingered in the kitchen after dinner and followed the group into the game room, where they laughed, chatted, and played pool until a big, dark, quiet figure snuck up to the glass patio doors that lead from the game room to the pitch blackness of the night.

“No way!” Dakota yelled when the porch light illuminated two Make-A-Wish volunteers pushing his Gator, his wish, his freedom, toward the closed door. His beaming smile pierced Sharon’s heart as he ran past her, opened the door quickly, and crawled inside the Gator.

“Who wants to go for a ride?” he asked excitedly.

Everyone gathered around as Dakota checked the wipers and the hood, opened and closed the doors, and gave the Gator a full inspection. The volunteers handed him a pile of John Deere clothing, which he layered with his own before heading out into the cold, January night. The summer sounds of crickets and bullfrogs had been hushed for months, the absence of lightning bugs leaving the moon and stars to light the way.

Dakota took one load after another of friends and family for a ride, and as Sharon and Henry watched, the Gator disappeared time after time into nothing but the sound of its own hum, taking the silence of the night with it. They had never seen him happier, or, after everything he had been through, more free.

As excitement and adrenaline sizzled inside of Dakota later that night, thoughts of all the places he would ride on his Gator dizzying his mind, he forced himself to fall asleep so he was ready for the big day ahead of him.

When he, Henry, Sharon, and Riley arrived at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston the next day, Dakota was immediately started on chemo, hoping to wipe away any remaining leukemia cells and demolishing his old immune system to replace it with Riley’s.

A month later, with Dakota’s numbers moving in the right direction, his condition improving just enough, it was time to harvest Riley’s cells, time to start the process of saving Dakota’s life.

Sitting at the foot of Riley’s bed, Dakota watched as hospital staff placed a mask over his younger brother’s face—something he had been through a hundred times—and he instigated a competition that he knew would take Riley’s mind off of being put under.

“Let’s see who can count longer,” Dakota said right before the machine was turned on.

When Riley got to twelve, Dakota pushed even further.

“Thirteen … fourteen …”

Riley’s eyes closed against his will, and Dakota closed his, too, saying a silent prayer that the cells they were taking would save his life. On transplant day, when doctors hung a bag of cells, Riley’s lifesaving cells, above Dakota on his IV tree, Sharon prayed over them—prayed that those cells would work as God’s army, march into Dakota’s veins, swim through his blood, give him back his life. Each drip crawled through the clear tube, forcing its way into Dakota’s body, demanding acceptance, creating life.

Dakota’s eyes moved up and down with every drop, watching intently as Riley’s cells fell into his body. His parents watched, too, and Sharon took her eyes away only to look at the sun as it crawled in through the shaded window, warming the room and her spirits. It was the first time in a long time she had actually noticed the sun, cared about its existence.

Things of beauty had been hiding for months beneath the selfish darkness, bleeding agony, which had consumed them. Sharon paid close attention to the movement of the sun, its morning dance, as though it were the first time she had ever seen it. This was a good day, a day of renewal, of new life. She felt it in every ounce of her being.

They all did.

When the last drops seeped in, the bag above hanging clear, it was time to wait. At 4:30 every morning, nurses came in to draw Dakota’s blood, and again, Sharon prayed. She prayed for signs of Riley’s cells in Dakota’s blood, and after twenty-one days, that prayer was answered—his red blood cell count was going up.

After a month and a half, with counts continuing to increase, Dakota could leave the hospital with daily visits. It was his first step toward getting back to the Gator. Thinking about the friends he would take and the places he would go, kept his mind clear, free, during those long days and nights at the hospital, just waiting.

“I can’t wait to take Zach and Brandon and Riley and Justin on long rides,” Dakota said of his brother and best friends. He talked every day about riding into the woods, hunting with his Gator, and visiting Moccasin Gap in the Ozark Mountains.

When Dakota was released from the hospital, he, Riley, and their parents stayed in what they called The Treehouse, a small, above-garage apartment at Sharon’s brother’s Houston home. Its soft white walls were somehow different from the bright, sterile shade in the hospital. This white was inviting, as was the old-fashioned, claw-foot tub in place of a cold, tile shower; books that had nothing to do with cancer; contemporary art hanging on the walls rather than posters of the body’s systems; and meals served on plates rather than trays. The Treehouse was just minutes away from MD Anderson, making daily visits easy and convenient.

The normal life Dakota was about to re-enter started in Houston, where he hung out and watched Survivor every Thursday night with good family friends, the Johnstons, played games and ate pizza with his Grandma Pat and Pa Pa Tom every Sunday night, and spent the weekends—when his counts were good and his energy was up—riding go-carts, visiting the zoo, going to the park, and playing golf, the only sport he never had to give up.

One day, he got a call from The Point, a classic rock radio station based out of Little Rock, Arkansas, during its annual Make-A-Wish Foundation fundraiser. Dakota Hawkins had become a household name across the state of Arkansas, with local and statewide news coverage of his condition, his progress, and his story.

At the MD Anderson clinic, where he went for regular tests and blood draws, Dakota sat at the nurse’s station for a phone interview with the radio station’s DJs about his progress, his transplant, his wish, and all the specifics of the Gator.

“You know, man, it’s like a pimped up four-wheeler,” Dakota said, smiling at the nurses surrounding him, who threw their heads back with laughter, clapping their hands, catching their breaths.

“A pimped up …” the DJ couldn’t even finish the sentence. He and the other DJs were in hysterics at the description.

When the laughter faded, Dakota looked down at the ground, fingers intertwined in the cord of the phone, his face serious.

“I’d like to thank Make-A-Wish for making my wish come true,” he said, and Sharon’s heart instantly became filled with happiness. She imagined her son’s voice in the ears of thousands, driving their cars, sitting in their offices or homes, listening to his story. The sincere gratitude in her son’s voice reflected how strongly he felt about the gift he had received and echoed his love for the Gator with which he would soon reunite.

9

9

Everyday checkups at MD Anderson turned into every three-day checkups, and after one hundred days, Dakota was released and sent home. The cancer was gone, his counts were up, and his organs were healthy.

Two weeks after settling home, he and his family went to Colorado on an all-expense-paid, five-day trip to a dude ranch near Steamboat Springs with nine other families, a doctor, and a nurse from MD Anderson. With the other kids, Dakota and Riley explored the mountain ranges on horses during the day, played kickball in the evenings, and enjoyed cookouts, barn dances, and dips in their cabin’s hot tub.

On their bus ride back to the airport, as they made their way toward Denver, nearing the Continental Divide, small, white flurries turned into what looked like the insides of a Christmas snow globe.

“Stop the bus!” Dakota shouted, and the driver slowly pulled to the side of the road. “Let’s have a snowball fight!”

That’s our Dakota, Sharon thought, grinning.

He and the other kids, all cancer patients, survivors, poured from the bus and into the snow, shoveling handfuls into balls and launching them like little cannonballs. They dusted the bus, its driver, the doctor, and nurse, one another, in white—all while laughing, living in that moment, undefined by cancer, in its cool freedom.

Sharon and Henry watched, smiles dancing on their faces, frozen in that moment of time. And while nothing could take away Sharon’s happiness, the heaviness in her chest, its pull through her belly, was something she could not deny. They were about to return to MD Anderson for a bone marrow aspiration—the deepest, most accurate cancer-detecting test—and all she could do was pray for good results.

Once again, her prayer was answered. Dakota was still cancer-free and Riley’s cells, in all of their determination, remained a friend to his brother’s body. Dakota could go home and continue that life of normalcy, of freedom, that had started in Houston just a few months earlier.

A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line in his chest was the only thing keeping Dakota from enjoying one of his favorite past times—swimming—so he had a decision to make. He could leave it in as a way for doctors to insert medicines and draw blood every month without having to poke him, or he could have it removed and get poked for those purposes every month.

He wanted it out—needed what was, in his mind, permanent detachment from cancer.

After healing from surgery to remove the line, Dakota went with Sharon to his friend Chad’s house for an afternoon dip, his first swim all summer. Chad and his family, who welcomed Dakota to their home at any time, were not home that afternoon, so Sharon soaked in the enjoyment of watching her son dive from the board, flip from the sides, and plunge deep into the water.

“I feel so free,” he said with a smile, looking right at her before ducking under the water, swimming quickly to the other side. He got out of the pool, stood on the diving board in his bright yellow swim shorts, and smiled again at his mom. A soft layer of golden hair that had just started to grow back gleamed like the sun, mirrored his shorts, became living proof that her Dakota was here to stay.

He’s the picture of health, Sharon thought to herself, smiling through tears as Dakota jumped back into the pool.

As a family, they traveled to Silver Dollar City theme park that summer, the resort town of Branson, Missouri, and to Moccasin Gap—a place where Dakota, Riley, and Henry rode four-wheelers—with its endless streams and twenty-eight miles of ATV and horse trails weaving through the hills and hollows of Arkansas’s Ozark Mountains.

As they did every year, Dakota, Riley, and Henry prepared for the upcoming deer hunting season at a deer camp in south Arkansas. They searched for signs of deer, inspecting bushes for places they might have rested and trees for traces of rubbing. They scoped out areas close to water that would quench the deer’s thirst and analyzed trees for their height and potential for deer spotting. Dakota would bring his Gator to collect their fallen prey, and his anticipation for October, deer hunting season, started on their three-hour drive home.

When the summer was over, Dakota registered for eighth grade and, once again, excelled with straight As, advanced placement classes, and a position on the varsity basketball team. He attended school dances, birthday parties, church on Sundays, and rode his Gator often with friends. He had returned to his old, normal life, where cancer was just a nightmare from which he had woken.

During Dakota’s next five monthly appointments, he received a clean bill of health—his cells were dead; Riley’s were thriving. The front door to cancer’s old home was closed, but like a sneaky robber, a malicious intruder, it found its way back in and hid behind corners inside Dakota’s body.

“It’s like hide-and-seek,” Dr. Becton explained to Dakota and Sharon during their sixth monthly checkup, where cancer cells had slowly come out from around those corners. “We found little, bitty cancer cells hiding within your cells.”

Cancer cells. Those words were supposed to be gone from their lives. How can this be happening again?

Sharon didn’t speak her thoughts; she didn’t mutter a word. And neither did Dakota. They sat in silence, the heaviness of Dr. Becton’s words setting like stone in their hearts.

It was time for chemo, once again.

10

10

They tried for two months at Arkansas Children’s and another two at MD Anderson in Houston, where doctors determined that those tiny cells had multiplied and cancer had taken over 100 percent of Dakota’s body.

After realizing that chemo wasn’t working, they exhausted every experimental and compassionate drug and determined a second transplant would most likely be fatal.

“I’m afraid Dakota doesn’t have long to live,” said Dr. Michael Rytting, one of Dakota’s doctors from MD Anderson, whom Henry and Sharon had grown to respect and trust over the course of the past year. He was one of those special doctors who treated patients the way Sharon imagined he would treat his own child. He was Dakota’s favorite doctor, he had years of experience, he specialized in cancer treatment, and he had an MD behind his name.

Henry and Sharon, however, had never made decisions based on statistics or speculations, and they weren’t about to start. They trusted the man standing before them, but trust only went so far. They needed to know if it was time to start seeking other options, finding other solutions. They were not going to give up.

“How long?” Sharon asked. “A month, a couple of months, years?”

“I’m thinking less than a year,” Dr. Rytting said sadly. “Single digit months.”

Dakota’s blood had become a river of cancer, but his organs were still healthy, and Henry and Sharon were not going to wait around for their son to die. They stayed up late each night, got up early every morning, to research any other possibility, any other solution, to save their son.

A friend at church told them about a missionary from Little Rock who was receiving treatment in Jerusalem, Israel, from Dr. Shimon Slavin, who, according to all of their research, was world-renowned for his work, untraditional and sometimes experimental, with cancer.

“Blood cancer doesn’t scare me,” Dr. Slavin said to Sharon when she called to explain Dakota’s situation. “If his organs are good, get him here healthy, and I can help him.”

His unwavering confidence rushed through the phone lines and into Sharon and Henry’s ears, into their hearts. They needed to get to Jerusalem.

“He’s your best option,” Dr. Rytting confirmed. “If Dakota was my son, I would do it. I’m not saying it’ll work, but it’s your best option.”

They had one week to return to Arkansas from Houston, get passports, and collect the money to pay Israel’s Hadassah Medical Hospital upfront—$175,000. Henry and Sharon planned to mortgage their home, but instead, word of mouth in the small town of Cabot spread like wildfire through every home, store, restaurant, and church.

In one Sunday, their home church offerings raised $40,000, while other community churches raised a combined total of $40,000. After golf tournaments, school fundraisers, and personal donations, Henry and Sharon needs were met—ample enough to cover all expenses in one week.

In Cabot, coming together as a community was a way of life. Aside from leaving for a few years to go to college, Henry grew up there and had never left. Cabot was home, and its people were his family. Local media had covered Dakota’s story from the beginning, keeping everyone in town up-to-date on his condition, encouraging endless support, welcoming love and prayers. But Henry, overwhelmed by their generosity, never imagined they would come together in such a powerful way for their son.

They had returned from Houston to Cabot on a Thursday, and within one week, they scrambled to pack and obtain all necessary medical releases and passports before boarding a plane from Little Rock to Jerusalem, where they would live for nearly four months. Dr. Slavin’s plan was to perform a transplant on Dakota, but not with Riley’s cells this time. Wiping away Dakota’s blood to replace it with his brother’s was no longer a solution—he was going to use Sharon’s cells, a partial donor.

He would replace half of Dakota’s blood with hers and let the battle begin with a graft-versus-host situation, where the healthy cells would fight against the remaining cancer cells, hopefully victoriously. It would be a fifty-fifty war, with well-planned strategies by Dr. Slavin and complicated manipulation tactics that would potentially wipe out the cancer cells.

During the first several days in Jerusalem, Dakota and his family felt like they had stepped back in time and into the pages of the Bible. In between blood draws and preliminary tests, Dakota remained well enough to see many of the places he had studied in Sunday school since he was a little boy, turning scripture he had read and pictures he had seen into something real.

Together, Dakota and his family walked along the edges of the Dead Sea and the Sea of Galilee, and visited the Valley of Megiddo, Nazareth, and the Jordan River. The day before entering the hospital, they went to the Garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus prayed his last prayer before crucifixion. They went into the Church of All Nations, a monastery that enshrines a piece of bedrock where Jesus had prayed. They walked along the quiet, marble floors, admiring the beautiful, floor-to-ceiling murals and mosaics, until they reached the center of the church, the Rock of Agony.

Taking turns, Dakota, Riley, Henry, and Sharon leaned down and placed their hands on the rock, closing their eyes, saying the same prayer.

Dakota’s transplant, his last chance, was the next day, and as they walked quietly from the church and into Jerusalem’s warm, promising air, Dakota sat without a word on the steps outside the church.

Henry and Sharon looked at each other and tugged at Riley’s arm, motioning him away. They gave Dakota the space he needed, the quiet he craved in that very moment where, though she will never know for sure, Sharon assumed her son was talking with the Lord, praying for His healing, moved by the burden Christ must have felt when kneeling at that very rock the day before His crucifixion.

Elbows resting on his knees, head in his hands, Dakota looked out over the old City of Jerusalem and wiped his tears.

“I want to be with Jesus,” Dakota said.

He was ready.

They had been back from Israel for more than nine months, where a transplant with Sharon’s cells had failed and another using Riley’s cells for rescue wasn’t enough. Riley had given his brother life for the second time, just enough to bring him home to enjoy a couple of months, once again, in remission, his future unknown.

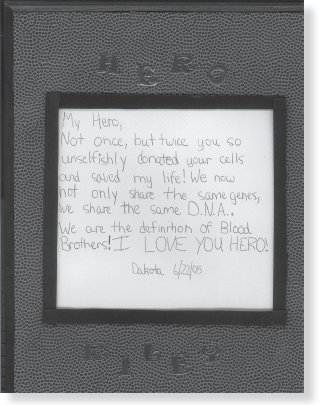

Dakota wrote these words for his brother, Riley, after Riley gave his bone marrow twice to help save his big brother’s life. Riley framed the words and placed them in his room, where they would remain a reminder of Dakota’s battle, his strength, his love, and his life.

11

11

A few months after writing those words to his brother, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) sped along cancer’s mission of taking Dakota’s life, which it did on March 2, 2006, when he was fifteen years old, four years after his diagnosis.

During the last few months of his life, as Dakota suffered through GVHD with respiratory syncytial viruses and lung and skin infections, he came to peace with thoughts of Heaven as his new home and God and angels, his new family.

Sharon had prayed on the hillsides of Jerusalem in the early mornings that God would take her life instead. But when they got home and Dakota’s condition worsened, pain and misery defining his life, hope was no longer something to hold onto, so she made one final plea before accepting the destiny her son had already accepted.

“Please just give Dakota the thirty-three years you gave to your own son, Jesus,” she asked, but she knew that God had His own plan, His own reason for taking Dakota.

From the day he took his last breath in Sharon’s arms, she struggled to see that reason—struggled to recognize God’s plan, to know His intentions, to understand His purpose for Dakota in the lives of others. But she never doubted.

Less than a year later, she became involved with the Keep The Faith (KTF) Foundation in memory of Dakota and two other children who lost their lives to cancer, as a way to keep the spirits of those children alive and to carry out what she believed was their purpose—to help other families with what hers had already been through.

With annual fundraisers and contributions, the Foundation raised more than $100,000 in its first six years to help families of children with cancer. In addition to helping families through prayer and encouragement, they also help relieve financial burdens by paying medical bills and other expenses accrued through cancer diagnosis and treatment.

A true believer that no tears exist in Heaven, Sharon knows Dakota is watching from above, unable to see the wretched pain of loss she and her family live with every day. He cannot hear the sadness in their voices, feel the pain in their hearts. He can only smile, and she gives him plenty of reasons to do so through KTF and its largest fundraiser, Pennies from Heaven (PFH).

She and KTF volunteers place buckets in schools, businesses, churches, and civic organizations all over town annually on March 5—the day they buried Dakota—and their first goal in 2008 was to collect one million pennies in one hundred days. They collected 1.1 million pennies—$11,000. They have collected a few thousand more every year, and in 2011, when they launched PFH statewide, the program raised $21,000.

Sharon asks no questions, has no doubts, when pennies cross her path on the sidewalk or appear strategically placed on Dakota’s tombstone—they are small, shiny reminders that he is always with her.

And over the years, with each fallen penny, Sharon, Henry, and Riley have slowly learned to see the world again through their tears, feel again through their constant ache, enjoy moments through their grief and pain, their forever loss.

They have realized that Dakota is always with them, sending reminders with pennies on the street or memories with the Gator he left behind—a gift for them, a gift that will forever give.

On the afternoon of Dakota’s death, Riley rode the Gator deep into the forest, through its endless trees, into the serenity his brother had always found in the woods. He found peace in the Gator’s hum that day, guidance in its freedom, hope that riding the Gator would always bring a sense of comfort, of closeness, to Dakota and his love for his Gator.

Adventures on the Gator would not end that day, and it didn’t take much time for the Hawkins family to realize what a true gift it really was. Over the years, Henry, Sharon, and Riley have traveled hundreds of miles on the Gator, in the presence of Dakota’s spirit, through hills and forests, rain, mud, and the Arkansas sunshine. It has been stuck, rescued, and the saving grace on good hunting days.

When Dakota first made his wish, Sharon was certain it was for him. It was for his freedom, his need to explore and was his way of getting something he knew his parents could not afford to buy.

But every treasured moment on the Gator has revealed to Sharon and her family Dakota’s clear intent; his wish was for them—he had chosen something he could leave behind.

Three years after Dakota’s death, Sharon and Henry received a clear message from God, telling them that, even in grief, even with holes in their hearts that could only be filled by Dakota, they still had love to give. After months of family discussion and lots of prayer, they called a local adoption agency to foster a child in need. They received a phone call one day about a two-year-old little boy waiting for a good home, and as soon as they heard the boy’s birth name—Dakota Quinn—they knew in her hearts that it was providential.

Sharon sat, silenced, on the phone, eyes filling with tears, heart filling with God’s message. This little boy, Dakota Quinn, was meant to be with them. Sharon, Henry, and Riley opened their home and their hearts to the boy, who they decided to call Quinn, and a year later, adopted him into their family.

There was no doubt in their minds that Quinn was sent from above—a gift that they knew Dakota would smile about from Heaven. God had given his parents this gift, just as Dakota had given the Gator, a gift that would keep on giving; a gift for his brother, Riley; his parents; and now their son Quinn.