Filled with more natural and historical mystique than people, the Highlands are where Scottish dreams are set. Legends of Bonnie Prince Charlie linger around crumbling castles as tunes played by pipers in kilts swirl around tourists. Intrepid Munro baggers scale bald mountains, grizzled islanders man drizzly ferry crossings, and midges make life miserable (bring bug spray). The Highlands are the most mountainous, least inhabited, and—for many—most scenic and romantic part of Scotland.

The Highlands are covered with mountains, lochs, and glens, scarcely leaving a flat patch of land for building a big city. Geographically, the Highlands are defined by the Highland Boundary Fault, which slashes 130 miles diagonally through the middle of Scotland just north of the big cities of the more densely populated “Central Belt” (Glasgow and Edinburgh).

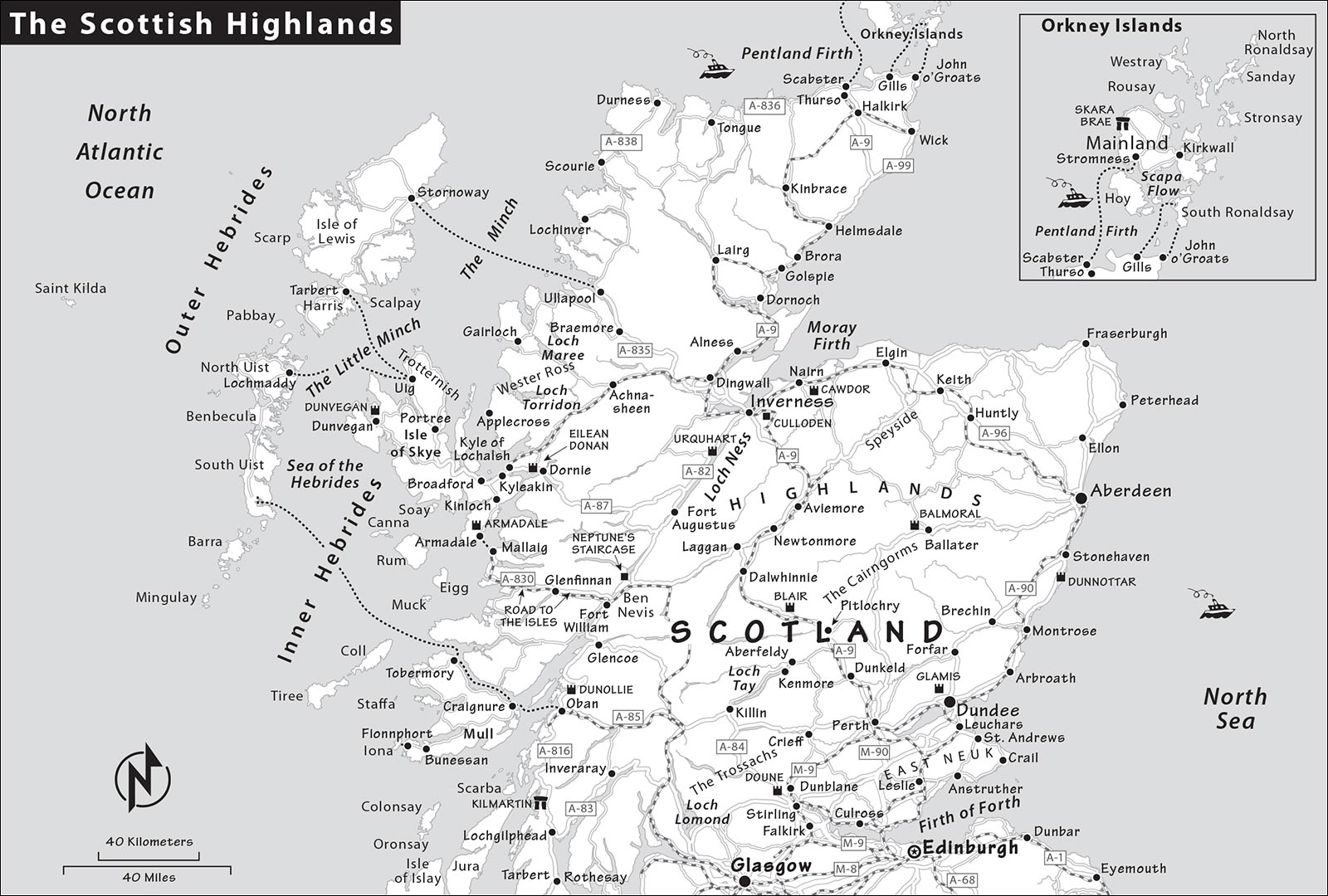

This geographic and cultural fault line is clearly visible on maps, and you can even see it in the actual landscape—especially around Loch Lomond and the Trossachs, where the transition from rolling Lowland hills to bald Highland mountains is almost too on-the-nose. Just beyond the fault, the Grampian Mountains curve across the middle of Scotland; beyond that, the Caledonian Canal links the east and west coasts (slicing diagonally through the Great Glen, another geologic fault, from Oban to Inverness), with even more mountains to the north.

Though the Highlands’ many “hills” are technically too short to be called “mountains,” they do a convincing imitation. (Just don’t say that to a Scot.) Scotland has 282 hills over 3,000 feet. A list of these was first compiled in 1891 by Sir Hugh Munro, and to this day the Scots call their high hills “Munros.” (Hills from 2,500-3,000 feet are known as “Corbetts,” and those from 2,000-2,500 are “Grahams.”) Avid hikers—called “Munro baggers”—love to tick these mini mountains off their list. According to the Munro Society, more than 5,000 intrepid hikers can brag that they’ve climbed all of the Munros. (To get started, you’ll find lots of good information at www.walkhighlands.co.uk/munros).

The Highlands occupy more than half of Scotland’s area, but are populated by less than five percent of its people—a population density comparable to Russia’s. Scotland’s Hebrides Islands (among them Skye, Mull, Iona, and Staffa), while not, strictly speaking, in the Highlands, are often included simply because they share much of the same culture, clan history, and Celtic ties. (Orkney and Shetland, off the north coast of Scotland, are a world apart—they feel more Norwegian than Highlander.)

Inverness is the Highlands’ de facto capital, and often claims to be the region’s only city. (The east coast port city of Aberdeen—Scotland’s third largest, and quadruple the size of Inverness—has its own Doric culture and dialect, and is usually considered its own animal.)

The Highlands are where you’ll most likely see Gaelic—the old Celtic language that must legally accompany English on road signs. While few Highlanders actually speak Gaelic—and virtually no one speaks it as a first language—certain Gaelic words are used as a nod of respect to their heritage. Fàilte (welcome), Slàinte mhath! (cheers!—literally “good health”), and tigh (house—featured in many business names) are all common. If you’re making friends in a Highland pub, ask your new mates to teach you some Gaelic words.

The Highlands are also the source of many Scottish superstitions, some of which persist in remote communities, where mischievous fairies and shape-shifting kelpies are still blamed for trouble. In the not-so-distant past, new parents feared that their newborn could be replaced by a devilish imposter called a changeling. Well into the 20th century, a midwife called a “howdie” would oversee key rituals: Before a birth, doors and windows would be unlocked and mirrors would be covered. And the day of the week a baby is born was charged with significance (“Monday’s child is fair of face, Tuesday’s child is full of grace...”).

Many American superstitions and expressions originated in Scotland (such as “black sheep,” based on the idea that a black sheep was terrible luck for the flock). Just as a baseball player might refuse to shave during a winning streak, many perfectly modern Highlanders carry a sprig of white heather for good luck at their wedding (and are careful not to cross two knives at the dinner table). And let’s not even start with the Loch Ness monster...

In the summer, the Highlands swarm with tourists...and midges. These miniature mosquitoes—like “no-see-ums”—are bloodthirsty and determined. They can be an annoyance from late May through September, depending on the weather. Hot sun or a stiff breeze blows the tiny buggers away, but they thrive in damp, shady areas. Locals suggest blowing or brushing them off, rather than swatting them—since killing them only seems to attract more (likely because of the smell of fresh blood). Scots say, “If you kill one midge, a million more will come to his funeral.” Even if you don’t usually travel with bug spray, consider bringing or buying some for a summer visit. Locals recommend Avon’s Skin So Soft, which is effective against midges, but less potent than DEET-based bug repellants.

Keep an eye out for another Scottish animal: shaggy Highland cattle called “hairy coos.” They’re big and have impressive horns, but are best known for their adorable hair falling into their eyes (the hair protects them from Scotland’s troublesome insects and unpredictable weather). Hairy coos graze on sparse vegetation that other animals ignore, and, with a heavy coat (rather than fat) to keep them insulated, they produce a lean meat that resembles venison. (Highland cattle meat is not commonly eaten, and the relatively few hairy coos you’ll see are kept around mostly as a national symbol.)

While the prickly, purple thistle is the official national flower, heather is the unofficial national shrub. This scrubby vegetation blankets much of the Highlands. It’s usually a muddy reddish-brown color, but it bursts with purple flowers in late summer; the less common bell heather blooms in July. Heather is one of the few things that will grow in the inhospitable terrain of a moor, and it can be used to make dye, rope, thatch, and even beer (look for Fraoch Heather Ale).

Highlanders are an outdoorsy bunch. For a fun look at local athletics, check whether your trip coincides with one of the Highland Games that enliven Highland communities in summer (see the sidebar later in this chapter). And keep an eye out for the unique Highland sport of shinty: a brutal, fast-paced version of field hockey, played for keeps. Similar to Irish hurling, shinty is a full-contact sport that encourages tackling and fielding airborne balls, with players swinging their sticks (called camans) perilously through the air. The easiest place to see shinty is at Bught Park in Inverness (see here), but it’s played across the Highlands.

Here are three recommended Highland itineraries: two days, four days, or a full week or more. These plans assume you’re driving, but can be done (with some modifications) by bus. Think about how many castles you really need to see: One or two is enough for most people.

This ridiculously fast-paced option squeezes the maximum Highland experience out of a few short days, and assumes you’re starting from Glasgow or Edinburgh.

Day 1: In the morning, head up to the Highlands. (If coming from Edinburgh, consider a stop at Stirling Castle en route.) Drive along Loch Lomond and pause for lunch in Inveraray. Try to get to Oban in time for the day’s last distillery tour (see here; smart to book ahead). Have dinner and spend the night in Oban.

Day 2: Get an early start from Oban and make a beeline for Glencoe, where you can visit the folk museum and enjoy a quick, scenic drive up the valley. Then drive to Fort William and follow the Caledonian Canal to Inverness, stopping at Fort Augustus to see the locks (and have a late lunch). Drive along Loch Ness to search for monsters, then wedge in a visit to the Culloden Battlefield (outside Inverness) in the late afternoon. Finally, make good time south on the A-9 back to Edinburgh (3 hours, arriving late).

Day 3: To extend this plan, take your time getting to Inverness on Day 2 and spend the night there. Follow my self-guided Inverness Walk either that evening or the next morning. Leaving Inverness, tour Culloden Battlefield, visit Clava Cairns, then head south, stopping off at any place that appeals: The best options near the A-9 are Pitlochry and the Scottish Crannog Centre on Loch Tay, or take the more rugged eastern route to see the Speyside whisky area, Balmoral Castle and Ballater village, and Cairngorms mountain scenery. Or, if this is your best chance to see Stirling Castle or the Falkirk sights (Falkirk Wheel, Kelpies sculptures), fit them in on your way south.

While you’ll see the Highlands on the above itinerary, you’ll whiz past the sights in a misty blur. This more reasonably paced plan is for those who want to slow down a bit.

Day 1: Follow the plan for Day 1, above, sleeping in Oban (2 nights).

Day 2: Do an all-day island-hopping tour from Oban, with visits to Mull, Iona, and (if you choose) Staffa.

Day 3: From Oban, head up to Glencoe for its museum and valley views. Consider lingering for a (brief) hike. Then zip up to Fort William and take the “Road to the Isles” west (pausing in Glenfinnan to see its viaduct) to Mallaig. Take the ferry over the sea to Skye, then drive to Portree to sleep (2 nights).

Day 4: Spend today enjoying the Isle of Skye. In the morning, do the Trotternish Peninsula loop; in the afternoon, take your pick of options (Talisker Distillery, Dunvegan Castle, multiple hiking options).

Day 5: Leaving Portree, drive across the Skye Bridge for a photo-op pit stop at Eilean Donan Castle. The A-87 links you over to Loch Ness, which you’ll follow to Inverness. If you get in early enough, consider touring Culloden Battlefield this evening. Sleep in Inverness (1 night).

Day 6: See the Day 3 options for my Highlands Highlights Blitz, earlier.

Using the six-day Highlands and Islands Loop as a basis, pick and choose from these possible modifications (listed in order of where they’d fit into the itinerary):

• Add an overnight in Glencoe to make more time for hiking there.

• Leaving the Isle of Skye, drive north along Wester Ross (the scenic northwest coast). Go as far as Ullapool, then cut back down to Inverness, or...

• Take another day or two (after spending the night in Ullapool) to carry on northward through remote and rugged scenery to Scotland’s north coast. Drive east along the coast all the way to John O’Groats; then either take the ferry from Scrabster across to Orkney, or shoot back down to Inverness on the A-9 (about 3 hours).

• Visit Orkney (2-night minimum). This can fit into the above plan after John O’Groats. Or, to cut back on the remote driving, simply zip up on the A-9 from Inverness (about 3 hours)—or fly up from Inverness, Edinburgh, or Aberdeen.

• On the way south from Inverness, follow the Speyside whisky trail, cut through the Cairngorms, visit Balmoral Castle, and sleep in Ballater. Between Balmoral and Edinburgh, consider visiting Glamis Castle (Queen Mum’s childhood home), Dundee (great industrial museums), or Culross (scenic firthside village).

• Add an overnight wherever you’d like to linger; the best options are the Isle of Skye (to allow more island explorations) or Inverness (to fit in more side-trips).

By Car: The Highlands are made for joyriding. There are a lot of miles, but they’re scenic, the roads are good, and the traffic is light. Drivers enjoy flexibility and plenty of tempting stopovers. Be careful about passing, but don’t be too timid; otherwise, diesel fumes and large trucks might be your main memory of driving in Scotland. The farther north you go, the more away-from-it-all you’ll feel, with few signs of civilization. Even on a sunny weekend, you can go miles without seeing another car. Don’t wait too long to gas up—village gas stations are few and far between, and can close unexpectedly. Get used to single-lane roads: While you can make good time when they’re empty (as they often are), stay alert, and slow down on blind corners—you never know when an oncoming car (or a road-blocking sheep) is just around the bend. If you do encounter an oncoming vehicle, the driver closest to a pullout is expected to use it—even if they have to back up. A little “thank-you” wave (or even just an index finger raised off the steering wheel) is the customary end to these encounters.

By Public Transportation: Glasgow is the gateway to this region (so you’ll most likely have to transfer there if coming from Edinburgh). Trains zip from Glasgow to Fort William, Oban, and Kyle of Lochalsh in the west; and up to Stirling, Pitlochry, and Inverness in the east. For more remote destinations (such as Glencoe), the bus is better.

Most buses are operated by Scottish Citylink. In peak season—when these buses fill up—it’s smart to buy tickets at least a day in advance: Book at Citylink.co.uk [URL inactive], call 0871-216-3333, or stop by a bus station or TI. Otherwise, you can pay the driver in cash when you board.

Glasgow’s Buchanan Station is the main Lowlands hub for reaching Highlands destinations. From Edinburgh, it’s best to transfer in Glasgow (fastest by train, also possible by bus)—though there are direct buses from Edinburgh to Inverness, where you can connect to Highlands buses. Once in the Highlands, Inverness and Fort William serve as the main bus hubs.

Note that bus frequency can be substantially reduced on Sundays and in the off-season (Oct-mid-May). Unless otherwise noted, I’ve listed bus information for summer weekdays. Always confirm schedules locally.

These buses are particularly useful for connecting the sights in this book:

Buses #976 and #977 connect Glasgow with Oban (5/day, 3 hours).

Buses #914/#915/#916 go from Glasgow to Fort William, stopping at Glencoe (7-8/day, 2.5 hours to Glencoe, 3 hours total to Fort William). From Fort William, some of these buses continue all the way up to Portree on the Isle of Skye (3/day, 7 hours for the full run).

Bus #918 goes from Oban to Fort William, stopping en route at Ballachulish near Glencoe (2/day, 1 hour to Ballachulish, 1.5 hours total to Fort William).

Bus #N44 (operated by Shiel Bus) is a cheaper alternative for connecting Glencoe to Fort William (about 8/day, fewer Sat-Sun, www.shielbuses.co.uk).

Buses #919 and #920 connect Fort William with Inverness (6/day, 2 hours, fewer on Sun).

Buses #M90 and #G90 run from Edinburgh to Inverness (express #G90, 2/day, 3.5 hours; slower #M90, some stop in Pitlochry, 6/day, 4 hours).

Bus #917 connects Inverness with Portree, on the Isle of Skye (3-4/day, 3 hours).

Bus #G10 is an express connecting Inverness and Glasgow (5/day, 3 hours). National Express #588 also goes direct (1/day, 4 hours, www.nationalexpress.com).