Wester Ross & the North Coast • Orkney Islands

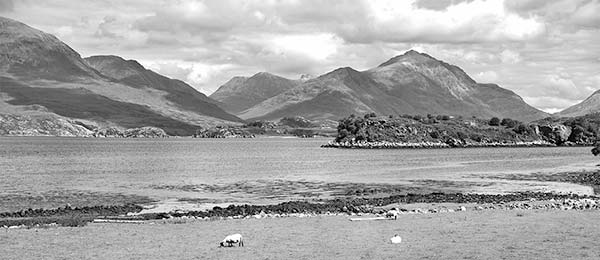

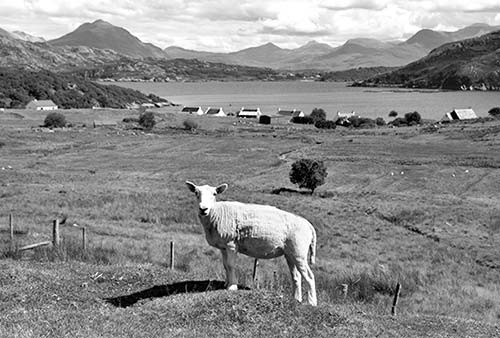

Scotland’s far north is its rugged and desolate “Big Sky Country”—with towering mountains, vast and moody moors, achingly desolate glens, and a jagged coastline peppered with silver-sand beaches. Far less discovered than the big destinations to the south, this is where you can escape the crowds and touristy “tartan tat” of the Edinburgh-Stirling-Oban-Inverness rut, and get a picturesque corner of Scotland all to yourself. Even on a sunny summer weekend, you may not pass another car for miles. It’s just you and the Munro baggers. Beyond Orkney, there’s no real “destination” in the north—it’s all about the journey.

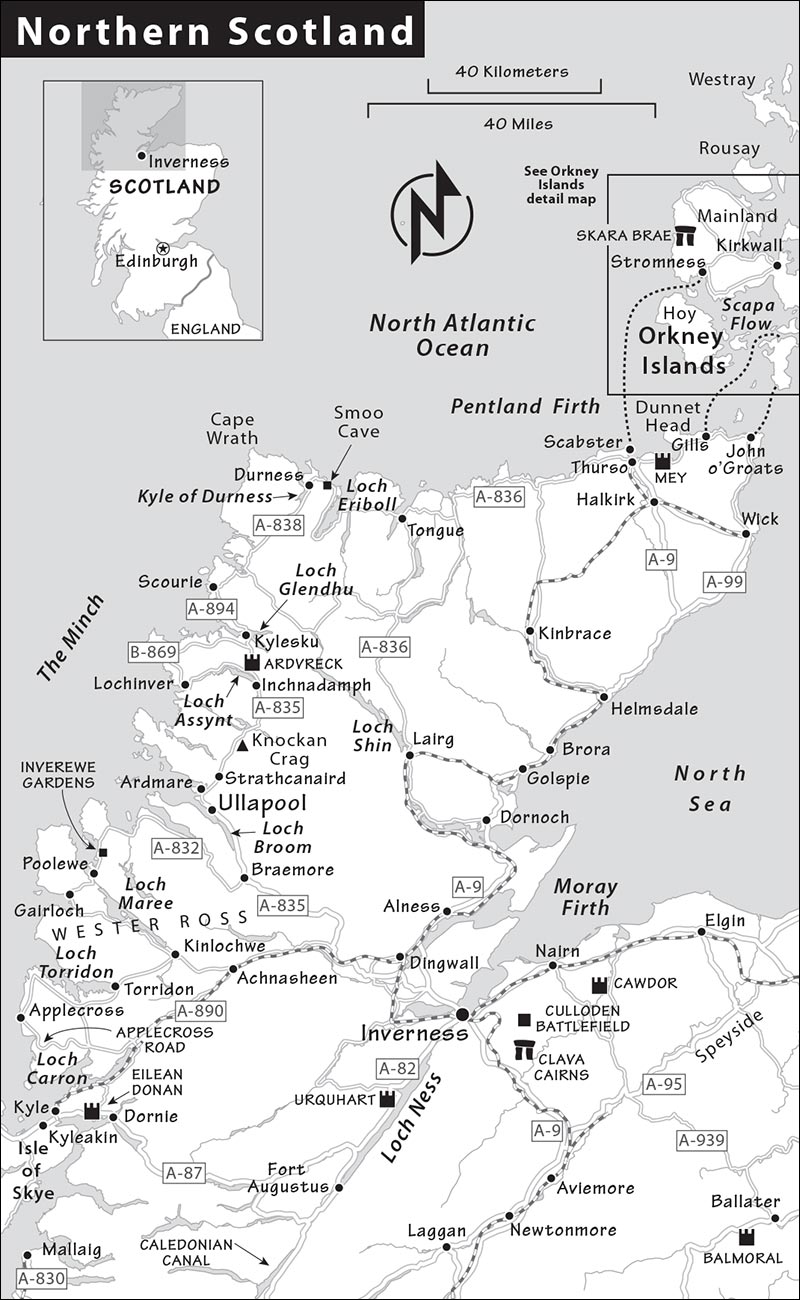

This chapter covers everything north of the Isle of Skye and Inverness: the scenic west coast (called Wester Ross); the sandy north coast; and the fascinating Orkney archipelago just offshore from Britain’s northernmost point.

Fully exploring northern Scotland takes some serious time. The roads are narrow, twisty, and slow, and the pockets of civilization are few and far between. With two weeks or less in Scotland, this area doesn’t make the cut (except maybe Orkney). But if you have time to linger, and you appreciate desolate scenery and an end-of-the-world feeling, the untrampled north is worth considering.

Even on a shorter visit, Orkney may be alluring for adventurous travelers seeking a contrast to the rest of Scotland. The islands’ claims to fame—astonishing prehistoric sites, Old Norse (Norwegian) heritage, and recent history as a WWI and WWII naval base—combine to spur travelers’ imaginations.

For a scenic loop through this area, try this four-day plan. For some this may be a borderline-unreasonable amount of driving, on twisty, challenging, often one-lane roads (especially on days 1 and 2). Connecting Skye or Glencoe to Ullapool takes a full day. If you don’t have someone to split the time behind the wheel, or if you want to really slow down, consider adding another overnight to break up the trip.

| Day 1 | From the Isle of Skye, drive up the west coast (including the Applecross detour, if time permits), overnighting in Torridon or Ullapool. |

| Day 2 | Continue the rest of the way up the west coast, then trace the north coast from west to east, catching the late-afternoon ferry to Orkney. Overnight in tidy Kirkwall (2 nights). |

| Day 3 | Spend all day on Orkney. |

| Day 4 | Finish up on Orkney and take the ferry back to the mainland; with enough time and interest, squeeze in a visit to John O’Groats before driving three hours back to Inverness (on the relatively speedy A-9). |

Planning Tips: To reach Orkney most efficiently—without the slow-going west-coast scenery—consider zipping up on a flight (easy and frequent from Inverness, Edinburgh, or Aberdeen), or make good time on the A-9 highway from Inverness up to Thurso (figure 3 hours one-way) to catch the ferry.

It’s possible (but very slow) to traverse this area by bus, but I’d skip it without a car. If you’re flying to Orkney, consider renting a car for your time here.

North of the Isle of Skye, Scotland’s scenic Wester Ross coast (the western part of the region of Ross), is remote, sparsely populated, mountainous, and slashed with jagged “sea lochs.” (That’s “inlets” in American English, or “fjords” in Norwegian.) After seeing Wester Ross’ towering peaks, you’ll understand why George R.R. Martin named the primary setting of his Game of Thrones epic “Westeros.”

The area is a big draw for travelers seeking stunning views without the crowds. For casual visitors, the views in Glencoe and on the Isle of Skye are much more accessible and just as good as what you’ll find farther north. But diehards enjoy getting away from it all in Wester Ross.

Scotland’s 100-mile-long north coast, which stretches from Cape Wrath in the northwest corner to John O’Groats in the northeast, is gently scenic, but less dramatic than Wester Ross. Views in this region are dominated by an alternating array of moors and rugged coastline. This is a good place to make up the long miles of Wester Ross.

This section outlines three drives that, when combined, take you along this region’s west and north coasts. The first Wester Ross leg (from Eilean Donan Castle to Ullapool) is the most scenic, with a fine variety of landscapes—but not many towns—along the way. The next Wester Ross leg gets you to Scotland’s northwest corner and the town of Durness. The final leg sweeps you across the north coast, to John O’Groats.

If you want just a taste of this rugged landscape—without going farther north—you can drive the Wester Ross coastline almost as far as Ullapool, then turn off on the A-835 for a quick one-hour drive to Inverness.

In this region, roads are twisty and often only a single lane, so don’t judge a drive by its mileage alone. Allow plenty of extra time.

This long drive, worth ▲▲, connects the picture-perfect island castle of Eilean Donan to the humble fishing village of Ullapool, the logical halfway point up the coast. Figure about 130 miles and nearly a full day for this drive, plus another 20 slow-going miles if you take the Applecross detour (described below).

From the A-87, a few miles east of Kyle of Lochalsh (and the Skye Bridge), follow signs for the A-890 north toward Lochcarron. (Note that Eilean Donan Castle is just a couple of miles farther east from this turnoff; if coming from Skye, you could squeeze in a visit to that castle before backtracking to this turnoff; for castle details see here). From here on out, you can carefully track the brown Wester Ross Coastal Trail signs, which will keep you on track.

You’ll follow the A-890 as it cuts across a hilly spine, then twists down and runs alongside Loch Carron. At the end of the loch, just after the village of Strathcarron, you’ll reach a T-intersection that offers two choices. The faster route up to Ullapool—which skips much of the best scenery—takes you right on the A-890 (toward Inverness). But for the scenic route outlined here, instead turn left, following the A-896 (following signs for Lochcarron). From here, you’ll follow the opposite bank of Loch Carron.

Applecross Detour: Soon after you pull away from the lochside, you’ll cross over a high meadow and see a well-marked turnoff on the left for a super-scenic—but challenging—alternate route: the Applecross Road, over a pass called Bealach na Bà (Gaelic for “Pass of the Cattle”). Intimidating signs suggest a much more straightforward alternate route that keeps you on the A-896 straight up to Loch Torridon (if doing this, skip down to the “Loch Torridon” section, later). But if you’re relatively comfortable negotiating steep switchbacks, and have time to spare (adding about 20 miles to the total journey), this road is drivable. You’ll twist up, up, up—hearing your engine struggle up gradients of up to 20 percent—and finally over, with rugged-moonscape views over peaks and lochs. From the summit (at 2,053 feet), the jagged mountains rising from the sea are the Cuillin Hills on the Isle of Skye. Finally, you’ll corkscrew back down the other side, arriving at the humble seafront town of Applecross.

Once in Applecross, you could either return over the same pass to pick up the A-896 (slightly faster), or, for a meandering but very scenic route, carry on all the way around the northern headland of the peninsula. This provides you with further views of Raasay and Skye, through a deserted-feeling landscape on one-lane roads. Then, turning the corner at the top of the peninsula, you’ll begin to drive above Loch Torridon, with some of the finest views on this drive.

Loch Torridon: Whether you take the Applecross detour or the direct route, you’ll wind up at the stunning sea loch called Loch Torridon—hemmed in by thickly forested pine-covered hills, it resembles the Rockies. You’ll pass through an idyllic fjordside town, Shieldaig, then cross over a finger of land and plunge deeper into Upper Loch Torridon. Near the end of the loch, keep an eye out for The Torridon—a luxurious lochfront grand hotel with gorgeous Victorian Age architecture, a café serving afternoon tea, and expensive rooms (www.thetorridon.com).

As you loop past the far end of the loch—with the option to turn off for the village of Torridon (which has a good youth hostel, www.hostellingscotland.org.uk)—the landscape has shifted dramatically, from pine-covered hills to a hauntingly desolate glen. You’ll cut through this valley—bookended by towering peaks and popular with hikers—before reaching the town of Kinlochewe.

At Kinlochewe, take the A-832 west (following Ullapool signs from here on out), and soon you’ll be tracing the bonnie, bonnie banks of Loch Maree—considered by many connoisseurs to be one of Scotland’s finest lochs. You’ll see campgrounds, nature areas, and scenic pullouts as you make good time on the speedy two-lane lochside road. (The best scenery is near the beginning, so don’t put off that photo op.)

Nearing the end of Loch Maree, the road becomes single-track again as you twist up over another saddle of scrubby land. On the other side, you’ll get glimpses of Gair Loch through the trees, before finally arriving at the little harbor of Gairloch. Just beyond the harbor, where the road straightens out as it follows the coast, keep an eye out (on the right) for the handy Gale Center. Run as a charity, it has WCs, a small café with treats baked by locals, a fine shop of books and crafts, and comfortable tables and couches for taking a break (www.galeactionforum.co.uk).

True to its name, Gair Loch (“Short Loch”) doesn’t last long, and soon you’ll head up a hill (keep an eye out for the pullout on the left, offering fine views over the village). The next village is Polewe, on Loch Ewe. Just after the village, on the left, is the Inverewe Gardens. These beautiful gardens, run by the National Trust for Scotland, were the pet project of Osgood Mackenzie, who in 1862 began transforming 50 acres of his lochside estate into a subtropical paradise. The warming Gulf Stream and—in some places—stout stone walls help make this oasis possible. If you have time and need to stretch your legs from all that shifting, spend an hour wandering its sprawling grounds. The walled garden, near the entrance, is a highlight, with each bed thoughtfully labeled (£12.50, daily, www.nts.org.uk).

Continuing on the A-832 toward Ullapool, you’ll stay above Loch Ewe, then briefly pass above the open ocean. Soon you’ll find yourself following Little Loch Broom (with imposing mountains on your right). At the end of that loch, you’ll carry on straight and work your way past a lush strip of farmland at the apex of the loch. Soon you’ll meet the big A-835 highway; turn left and take this speedy road the rest of the way into Ullapool. (Or you can turn right to zip on the A-835 all the way to Inverness—just an hour away.) Whew!

A gorgeously set, hardworking town of about 1,500 people, Ullapool (ulla-PEWL) is what passes for a metropolis in Wester Ross. Its most prominent feature is its big, efficient ferry dock, connecting the mainland with Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis (Scotland’s biggest, in the Outer Hebrides). Facing the dock is a strip of cute little houses, today housing restaurants, shops, B&Bs, and residences. Behind the waterfront, the town is only a few blocks deep—you can get the lay of the land in a few minutes’ stroll. Curving around the back side of the town—along a big, grassy campground—is an inviting rocky beach, facing across the loch in one direction and out toward the open sea in the other.

Orientation to Ullapool: Ullapool has several handy services for travelers. An excellent bookshop is a block up, straight ahead from the ferry dock. Many services line Argyle Street, which runs parallel to the harbor one block up the hill: the TI is to the right, while a Bank of Scotland ATM and the post office are to the left. On this same street, the town runs a fine little museum with well-done exhibits about local history (closed Sun and Nov-March, www.ullapoolmuseum.co.uk). This street, nicknamed “Art-gyle Street,” also has a smattering of local art galleries.

Sleeping in Ullapool: Several guesthouses line the harborfront Shore Street, including $ Waterside House (3 rooms, minimum two-night stay in peak season, https://waterside.uk.net) and the town’s official ¢ youth hostel (www.hostellingscotland.org.uk). A block up from the water on West Argyle Street, $ West House has three rooms and requires a two-night minimum stay (no breakfast, closed Oct-April, www.westhousebandb.co.uk).

Eating in Ullapool: The two most reliable places are the $$ Ceilidh Place, on West Argyle Street a block above the harbor (www.theceilidhplace.com); and $$$ The Arch Inn, facing the water a half-block from the ferry dock (www.thearchinn.co.uk). Both have a nice pubby vibe as well as sit-down dining rooms with a focus on locally caught seafood. Both also rent rooms and frequently host live music. For a quick meal, two $ chippies (around the corner from each other, facing the ferry dock) keep the breakwater promenade busy with al fresco budget diners and happy seagulls.

This shorter drive, worth ▲, connects one quaint seaside town (Ullapool) to another (Durness—on the north coast) through rolling hills sprinkled with wee lochs and the dramatic landscape. Expect this drive (about 70 miles) to take another couple scenic hours, depending on your sightseeing stops.

Leaving Ullapool, follow signs that read simply North (A-835). You’ll pass through the cute little beachside village of Ardmair, then pull away from the coast.

About 15 minutes after leaving Ullapool, just after you exit the village of Strathcanaird and head uphill, watch on the left for a pullout with a handy orientation panel describing the panorama of towering peaks that line the road. It looks like a mossy Monument Valley. Enjoy the scenery for about four more miles—surrounded by lochs and gigantic peaks—and watch for the Knockan Crag visitors center, above you on the right, with exhibits on local geology, flora, and fauna and suggestions for area hikes (unmanned and open daily 24 hours, WCs, www.nnr.scot).

Continuing north along the A-835, you’ll soon pass out of the region of Ross and Cromarty and enter Sutherland. At the T-intersection, turn left for Kylesku and Lochinver (on the A-837). From here on out, you can start following the North & West Highlands Tourist Route; you’ll also see your first sign for John O’Groats at the northeastern corner of Scotland (152 miles away).

You’ll roll through moors, surrounded on all sides by hills. Just after the barely-there village of Inchnadamph, keep an eye out on the left for the ruins of Ardvrech Castle, which sits in crumbled majesty upon its own little island in Loch Assynt, connected to the world by a narrow sandy spit. Just after these ruins, you’ll have another choice: For the fastest route to the north coast, turn right to follow A-894 (toward Kylesku and Durness). If you have some time to spare, you could carry on straight to scenically follow Loch Assynt toward the sleepy fishing village of Lochinver (12 miles). After seeing the village, you could go back the way you came to the main road, or continue all the way around the little peninsula on the B-869, passing several appealing sandy beaches and villages.

Back on the main A-894, you’ll pass through an almost lunar landscape, with peaks all around, finally emerging at the gorgeous, mountain-rimmed Loch Glendhu, which you’ll cross on a stout modern bridge. From here, it’s a serene landscape of rock, heather, and ferns, with occasional glimpses of the coast—such as at Scourie, with a particularly nice sandy beach. Finally (after the road becomes A-838—keep left at the fork, toward Durness), you’ll head up, over, and through a vast and dramatic glen. At the end of the glen, you’ll start to see sand below you on the left; this is Kyle of Durness, which goes on for miles. You’ll see the turnoff for the ferry to Cape Wrath, then follow tidy stone walls the rest of the way into Durness.

This driving route takes you along the picturesque, remote north coast from west (Durness village) to east (the touristy town of John O’Groats). Allow at least 2.5 hours for this 90-mile drive (add more time for stops along the way).

This beachy village of cow meadows is delightfully perched on a bluff above sandy shores. This area has a different feel from Wester Ross—it’s more manicured, with tidy farms hemmed in by neatly stacked stone walls. There’s not much to see or do in the town, but there is a 24-hour gas station (gas up now—this is your last chance for a while...trust me) and a handy TI (by the big parking lot with the “Award Winning Beach,” tel. 01971/509-005).

Head east out of the village on the A-838, watching for brown signs on your right to Durness Village Hall. Pull over here to stroll through the small memorial garden for John Lennon, who enjoyed his boyhood vacations in Durness.

Just after the village hall, on the left, pull over at Smoo Cave (free WCs in parking lot). Its goofy-sounding name comes from the Old Norse smúga, for “cave.” (Many places along the north coast—which had a strong Viking influence—have Norse rather than Gaelic or Anglo-Saxon place names.) It’s free to hike down the well-marked stairs to a protected cove, where an underground river has carved a deep cave into the bluff. Walk inside the cave to get a free peek at the waterfall; for a longer visit, you can pay for a 20-minute boat trip and guided walk (unnecessary for most; sign up at the mouth of the cave).

Back on the road, soon after Smoo Cave, on the left, is the gorgeous Ceannabeinne Beach (Gaelic for “End of the Mountains”). Of the many Durness-area beaches, this is the locals’ favorite.

Heading east from the Durness area, you’ll traverse many sparsely populated miles—long roads that cut in and out from the coast, with scrubby moorland and distant peaks on the other side. You’ll emerge at the gigantic Loch Eriboll, which you’ll circumnavigate—passing lamb farms and crumbling stone walls—to continue your way east. Leaving this fjord, you’ll cut through some classic fjord scenery until you finally pop out at the scenic Kyle of Tongue. You’ll cross over the big, modern bridge, then twist up through the village of Tongue and continue your way eastward (the A-838 becomes the A-836)—through more of the same scrubby moorland scenery. Make good time for the next 40 lonely miles. Notice how many place names along here use the term “strath”—a wide valley (as opposed to a narrower “glen”), such as where jagged mountains open up to the sea.

Finally—after going through little settlements like Bettyhill and Melvich—the moors begin to give way to working farms as you approach Thurso. The main population center of northern Scotland (pop. 8,000), Thurso is a functional transit hub with a charming old core. As you face out to sea, the heavily industrialized point on the left is Scrabster, with the easiest ferry crossing to Orkney (for details, see “Getting to Orkney,” later).

Several sights near Thurso are worth the extra couple miles.

Dunnet Head: About eight miles east of Thurso (following brown John O’Groats signs on the A-836) is the village of Dunnet. If you have time for some rugged scenery, turn off here to drive the four miles (each way) to the Dunnet Head peninsula.

While John O’Groats is often dubbed “Britain’s northernmost point,” Dunnet Head pokes up just a bit farther. And, while it lacks the too-cute signpost marking distances to faraway landmarks, views from here are better than from John O’Groats. Out at the tip of Dunnet Head, a lonely lighthouse enjoys panoramic views across the Pentland Firth to Orkney, while a higher vantage point is just up the hill. Keep an eye out for seabirds, including puffins.

Mary-Ann’s Cottage: In the village of Dunnet, between the main road and Dunnet Head, this little stone house explains traditional crofting lifestyles. It appears just as it was when 92-year-old Mary-Ann Calder moved out in 1990 (very limited hours).

Castle of Mey: About four miles east of Mary-Ann’s Cottage (on the main A-836) is the Castle of Mey. The Queen Mother grew up at Glamis Castle, but after her daughter became Queen Elizabeth II, she purchased and renovated this sprawling property as an escape from the bustle of royal life...and you couldn’t get much farther from civilization than this. For nearly 50 years, the Queen Mum stayed here for annual visits in August and October. Today it welcomes visitors to tour its homey interior and 30 acres of manicured gardens (closed Oct-April, www.castleofmey.org.uk).

From Mey, it’s another six miles east to John O’Groats. About halfway there, in Gills Bay, is another ferry dock for cars heading to Orkney (see “Getting to Orkney,” later).

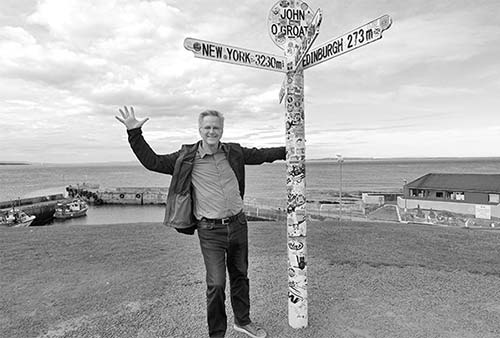

A total tourist trap that’s somehow also genuinely stirring, John O’Groats marks the northeastern corner of the Isle of Britain—bookending the country with Land’s End, 874 miles to the southwest in Cornwall. People enjoy traversing the length of Britain by motorcycle, by bicycle, or even by foot (it takes about eight weeks to trudge along the “E2E” trail—that’s “End to End”). And upon arrival, whether they’ve walked for two months or just driven up for the day from Inverness, everyone wants to snap a “been there, done that” photo with the landmark signpost. Surrounding that is a huge parking lot, a souvenir stand masquerading as a TI, and lots of tacky “first and last” shops and restaurants. Orkney looms just off the coast.

Nearby: The real target of “End to End” pilgrims isn’t the signpost, but the Duncansby Head Lighthouse—about two miles to the east, it’s the actual northeasternmost point, with an even more end-of-the-world vibe. (By car, head away from the John O’Groats area on A-99, and watch for the Duncansby Head turnoff on the left, just past the Seaview Hotel.) If you have time for a hike, about a mile south of the lighthouse are the Duncansby Stacks—dramatic sea stacks rising up above a sandy beach.

The Orkney Islands, perched just an hour’s ferry ride north of the mainland, are uniquely remote, historic, and—for the right traveler—well worth the effort.

Crossing the 10-mile Pentland Firth separating Orkney from northern Scotland, you leave the Highlands behind and enter a new world. With no real tradition for clans, tartans, or bagpipes, Orkney feels not “Highlander” or even “Scottish,” but Orcadian (as locals are called). Though Orkney was inhabited by Picts from the sixth century BC, during most of its formative history—from 875 all the way until 1468—it was a prized trading hub of the Norwegian realm, giving it a feel more Scandinavian than Celtic. The Vikings (who sailed from Norway, just 170 miles away) left their mark, both literally (runes carved into prehistoric stone monuments) and culturally: Many place names are derived from Old Norse, and the Orkney flag looks like the Norwegian flag with a few yellow accents.

There are other historic connections. In later times, Canada’s Hudson’s Bay Company recruited many Orcadians to staff its outposts. And given its status as the Royal Navy headquarters during both World Wars, Orkney remains one of the most pro-British corners of Scotland. In the 2014 independence referendum, Orkney cast the loudest “no” vote in the entire country (67 percent against).

Orkney’s landscape is also a world apart: Aside from some dramatic sea cliffs hiding along its perimeter, the main island is mostly flat and bald, with few trees, the small town of Kirkwall, and lots of tidy farms with gently mooing cows. While the blustery weather (which can change several times a day) keeps the vegetation on the scrubby side, for extra greenery each town has a sheltered community garden run by volunteers. Orkney’s fine sandy beaches seem always empty—as if lying on them will give you hypothermia. Sparsely populated, the islands have no traffic lights and most roads are single lane with “passing places” politely spaced as necessary.

Today’s economy is based mostly on North Sea oil, renewable energy, and fishing. The boats you’ll see are creel boats with nets and cages to collect crabs, lobsters, scallops, and oysters. Unless a cruise ship drops by, tourism seems to be secondary.

For the sightseer, Orkney has two draws unmatched elsewhere in Scotland: It has some of the finest prehistoric sites in northern Europe, left behind by an advanced Stone Age civilization that flourished here. And the harbor called Scapa Flow has fascinating remnants of its important military role during the World Wars—from intentional shipwrecks designed to seal off the harbor, to muscular Churchill-built barriers to finish the job a generation later.

Orkney (as the entire archipelago is called) is made up of 70 islands, with a total population of 24,500. The main island—with the primary town (Kirkwall) and ferry ports connecting Orkney to northern Scotland (Stromness and St. Margaret’s Hope)—is called, confusingly, Mainland. (It just goes to show you: One man’s island is another man’s mainland.)

Orkney merits at least two nights and one full day. Some people (especially WWII aficionados) spend days exploring Orkney, but I’ve focused on the main sights to see in a short visit—all on the biggest island.

The only town of any substance, Kirkwall is your best home base. You can see its sights in a few hours (a town stroll, the fine Orkney Museum, and its striking cathedral). From there, to see the best of Orkney in a single day, plan on driving about 70 miles, looping out from Kirkwall in two directions: Spend the morning at the prehistoric sites (Maeshowe and nearby sites, Skara Brae), and the afternoon driving along the Churchill Barriers and visiting the Italian Chapel.

Cruise Crowds: Orkney is Scotland’s busiest cruise port; on days when ships are in port, normally sleepy destinations can be jammed. Check the cruise schedule at www.orkneyharbours.com and plan accordingly to avoid busy times at popular sights (such as Skara Brae and the Italian Chapel).

By Car/Ferry: Two different car-ferry options depart from near Thurso, which is about a three-hour drive from Inverness (on the A-9); for the scenic longer route, you could loop all the way up Wester Ross, and then along the north coast from Durness to Thurso (see earlier in this chapter). The two companies land at opposite corners of Orkney, at Stromness and St. Margaret’s Hope; from either, it’s about a 30-minute drive to Kirkwall.

Plan on about £60 one-way for a car on the Northlink ferry, or £40 on the Pentland ferry, plus £20 per passenger. For either company, reserve online at least a day in advance; check in at the ferry dock 30 minutes before departure.

For most, the best choice is the Scrabster-Stromness ferry, operated by NorthLink (3/day in each direction in summer, 2/day off-season, 1.5-hour crossing, www.northlinkferries.co.uk). While it’s a slightly longer crossing, it’s also a bigger boat, with more services (including a good sit-down cafeteria—and famously tasty fish-and-chips), and it glides past the Old Man of Hoy, giving you an easy glimpse at one of Orkney’s top landmarks. This ferry is coordinated with bus #X99, connecting Scrabster to Inverness (www.stagecoachbus.com).

The Gills Bay-St. Margaret’s Hope route is operated by Pentland Ferries; its main advantage is the proximity of Gills Bay to John O’Groats, making it easy to visit Britain’s northeasternmost point on your way to or from the ferry—but Gills Bay is also that much farther from Inverness (3/day in each direction, one-hour crossing, www.pentlandferries.co.uk).

There’s also a passenger-only boat directly from John O’Groats to Burwick, which connects conveniently to an onward bus to Kirkwall (3/day June-Aug, 2/day May and Sept, none Oct-April, 40-minute crossing, www.jogferry.co.uk). While this works for those leaving their car at John O’Groats for a quick Orkney day trip, it’s more weather-dependent.

By Plane: Kirkwall’s little airport has direct flights to Inverness, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Aberdeen (www.flybe.com [URL inactive] has good deals if you book ahead). Landing at the airport, you’re four miles from Kirkwall; pick up a town map at the info desk. It’s convenient to pick up a rental car at the airport. There are not many taxis, so without a car your best bet is the bus that runs every 30 minutes—just pay the driver (airport code: KOI, tel. 01856/872-421, www.hial.co.uk/kirkwall-airport).

By Tour from Inverness: The John O’Groats foot ferry operates a very long all-day tour from Inverness that includes bus and ferry transfers, and a guided tour around the main sights (£76, daily June-Aug only, www.jogferry.co.uk).

While this chapter is designed for travelers with a car (or a driver/guide—see next), public buses do connect sights on Mainland (operated by Stagecoach, www.stagecoachbus.com). From Mainland, ferries fan out to outlying islets (www.orkneyferries.co.uk); the main ports are Kirkwall (for points north) and Houton (for Hoy). If taking a car on a ferry, it’s always smart to book ahead.

Local Guide: Husband-and-wife team Kinlay and Kirsty run Orkney Uncovered. Energetic and passionate about sharing their adopted home with visitors, they’ll show you both prehistoric and wartime highlights (everything in this chapter—which Kinlay helped research). They’re also happy to tailor an itinerary to your interests and offer a special price for Rick Steves readers (RS%—£300 for a full-day, 9-hour tour in a comfy van, more for 5 or more people, multiday tours and cruise excursions possible, tel. 01856/878-822, www.orkneyuncovered.co.uk, enquiries@orkneyuncovered.co.uk).

Kirkwall (pop. 9,000) is tidy and functional. Like the rest of the island, most of its buildings are more practical than pretty. But it has an entertaining and interesting old center and is a smart home base from which to explore the island. Whether sleeping here or not, you’ll likely pass through at some point (to gas up, change buses, use the airport, or stock up on groceries).

Historic Kirkwall’s shop-lined, pedestrian-only main drag leads from the cathedral down to the harbor, changing names several times as it curls through town. It’s a workaday strip, lined with a combination of humble local shops and places trying to be trendy. You’ll pop out at the little harbor, where fishing boats bob and ferries fan out to the northern islets.

The handy TI is at the bus station (on West Castle Street, daily 9:00-18:00, Oct-March until 17:00, tel. 01856/872-856, www.orkney.com). They produce a handy “breakfast bulletin” with the day’s events and tourist news. The bus station stores bags for free (but not overnight). If you don’t have a car, Craigies Taxi is reliable and responds quickly to a call (tel. 01856/878-787).

You’re likely to find live music somewhere most nights. The Reel Coffee Shop, next to the cathedral, is passionate about music and hosts folk and “trad” evenings with an inviting vibe (generally Wed, Thu, and Sat at 20:00). Among the local craft beers on tap, the most popular, a pale ale, is Scapa Special. (They say it goes down better than the German fleet.)

This grand edifice, whose pointy steeple is visible from just about anywhere in town, is one of Scotland’s most enjoyable churches to visit (free, Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, Sun from 13:00). The building dates from the 12th century, back when this was part of the Parish of Trondheim, Norway. Built from vibrant red sandstone by many of the same stonemasons who worked on Durham’s showpiece cathedral, St. Magnus is harmonious Romanesque inside and out: stout columns and small, rounded windows and arches. Inside, it boasts a delightful array of engaging monuments, all well-described by the self-guided tour brochure: a bell from the Royal Oak battleship, sunk in Scapa Flow in 1939 (explained later); a reclining monument of arctic explorer John Rae, who appears to be enjoying a very satisfying eternal nap; the likely bones of St. Magnus (a beloved local saint); and many other characteristic flourishes. But the highlight is the gravestones that line the walls of the nave, each one carved with reminders of mortality: skull and crossbones, coffin, hourglass, and the shovel used by the undertaker. Read some of the poignant epitaphs: “She lived regarded and dyed regreted.”

Nearby: The Bishop and Earl’s Palaces (across the street) are a pair of once-grand, now-empty ruined buildings—for most, they’re not worth the admission fee.

Just across the street from the cathedral, this museum packs the old parsonage with well-described exhibits covering virtually every dimension of history and life on the island. A visit here (to see the Stone Age, Iron Age, and Viking artifacts) can be good preparation before exploring the islands’ archaeological sites. Poking around, you’ll see a 1539 map showing how “Orcadia” was part of Scandinavia, an exhibit about the crazy annual brawl called The Ba’, and lots of century-old photos of traditional life (free, Mon-Sat 10:30-17:00, closed Sun, fine book shop, tel. 01856/873-535, www.orkney.gov.uk).

In front of the cathedral stands Kirkwall’s mercat cross (market cross), which is the starting point for the annual event called The Ba’. Short for “ball,” this is a no-holds-barred, citywide rugby match that takes place every Christmas and New Year’s Day. Hundreds of Kirkwall’s rough-and-tumble young lads team up based on neighborhood (the Uppies and the Doonies), and attempt to deliver the ball to the opposing team’s goal by any means necessary. The only rule: There are no rules. While it’s usually just one gigantic scrum pushing back and forth through the streets, other tactics are used (such as the recent controversy when one team simply tossed the ball in a car and drove it to the goal). Ask locals about their stories—or scars—from The Ba’.

Outside the town center is a sprawling stone facility that’s been distilling whisky since 1789 (legally). They give 75-minute tours similar to other distilleries, but this is one of only six in all of Scotland that malts its own barley—you’ll see the malting floor (where the barley is spread and stirred while germinating) and the peat-fired kilns. Guides love to explain how the distillery’s well-regarded whiskies get their flavor from Orkney’s unique composition of peat (composed mostly of heather on this treeless island) and its high humidity (which minimizes alcohol “lost to the angels” during maturation). While the distillery is “silent” for much of July and August, its one-hour tour is good even if the workers are gone (£10, tours on the hour daily 10:00-16:00, Sun 12:00-16:00, fewer off-season, includes two tasty shots; on the edge of town to the south, toward the Scapa Flow WWII sites; tel. 01856/874-619, www.highlandparkwhisky.com).

These accommodations are in or near Kirkwall. Orkney’s B&Bs are not well-marked; get specific instructions from your host before you arrive.

In Kirkwall: $$$ Lynnfield Hotel rents 10 rooms that are a bit old-fashioned in decor, but with modern hotel amenities (on Holm Road/A-961, tel. 01856/872-505, www.lynnfield.co.uk). High up in town, consider $$ Hildeval B&B, in a modern home with five contemporary-style rooms (on East Road, tel. 01856/878-840, www.hildeval-orkney.co.uk). With a handy location just behind the cathedral, $ 2 Dundas Crescent has four old-fashioned rooms rented by welcoming Ruth, in a big old house that used to be a manse—a preacher’s home (tel. 01856/874-805, www.twodundas.co.uk [URL inactive]). And ¢ the Kirkwall Youth Hostel rents both dorm beds and private rooms (Old Scapa Road, 15-minute walk from center, tel. 01856/872-243, www.hostellingscotland.org.uk).

In the Countryside: Just past the airport, $$ Straigona B&B, about a five-minute drive outside of Kirkwall, has three rooms in a cozy modern home, run by helpful Julie and Mike (two-night minimum stay in summer, tel. 01856/861-328, www.straigona.co.uk). For more anonymity and grand views over Scapa Flow, the recommended restaurant $$ The Foveran has eight rooms, some with contemporary flourish and others more traditional (5 minutes from Kirkwall by car on the A-964, tel. 01856/872-389, www.thefoveran.com).

The first two places are near the cathedral; the next two are on the harbor. The main pedestrian street connecting the harbor and cathedral is lined with other options. Hotels along the harbor are also a good bet for dinner.

$$ The Reel Coffee Shop is a music club, café, and pub popular for its light lunches (open daily 9:00-17:00, next to the cathedral). It reopens on many evenings to host live music (Wed, Thu, and Sat evenings from 20:00, 6 Broad Street, tel. 01856/871-000).

$$ Judith Glue Shop is a souvenir-and-craft shop across from the cathedral, with a cutesy café in the back (25 Broad Street, tel. 01856/874-225).

$ The Harbour Fry is the best place for fish-and-chips, with both eat-in and takeaway options (daily 12:00-21:00, half a block off the harbor at 3 Bridge Street, tel. 01856/873-170).

$$ Helgi’s Pub, facing the harbor, serves quality food and is popular for its fun menu and burgers. Upstairs is boring, the ground floor is more fun, and you’re welcome to sit at the bar if the tables are full. Reservations are smart for dinner (daily 12:00-14:00 & 17:00-21:00, 14 Harbor Street, tel. 01856/879-293, www.helgis.co.uk).

With talented chefs working hard to elevate Orcadian cuisine—using traditional local ingredients, but with international flourish, these are considered the best restaurants around.

$$$$ The Foveran, perched on a bluff with smashing views over Scapa Flow, has a cool, contemporary dining room with a wall of windows (dinner nightly May-Sept, weekends-only in winter, southwest of Kirkwall on the A-964, tel. 01856/872-389, www.thefoveran.com).

$$$$ Lynnfield Hotel, near the Highland Park Distillery on the way out of town, has a more traditional feel (open daily for lunch and dinner, reservations smart in the evening, on Holm Road/A-961, tel. 01856/872-505, www.lynnfield.co.uk).

Orkney boasts an astonishing concentration of 5,000-year-old Neolithic monuments worth ▲▲▲—one of the best such collections in Great Britain (and that’s saying something). And here on Orkney, there’s also a unique Bronze and Iron Age overlay, during which Picts, and then Vikings, built their own monuments to complement the ones they inherited. The best of these sites are easily toured along a single stretch of road, as described below.

Background: Five thousand years ago—centuries before Stonehenge—Orkney had a bustling settlement with some 30,000 people (a population larger than today’s). The climate, already milder than most of Scotland thanks to the Gulf Stream, was even warmer then, making this a desirable place to live. Orkney’s prehistoric residents left behind structures from every walk of life: humble residential settlements (Skara Brae, Barnhouse Village), mysterious stone circles (Ring of Brodgar, Stenness Stones), more than 100 tombs (Maeshowe, Tomb of the Eagles), and what appears to be a sprawling ensemble of spiritual buildings (the Ness of Brodgar). And, this being the Stone Age, all of this was accomplished using tools made not of metal, but of stone and bone. Many more sites await excavation. (Any time you see a lump or a bump in a field, it’s likely an ancient site—identified with the help of ground-penetrating radar—and protected by the government.) While you could spend days poring over all of Orkney’s majestic prehistoric monuments, on a short visit focus on the following highlights. (Actual artifacts from these sites are on display only in the Orkney Museum in Kirkwall.)

The finest chambered tomb north of the Alps, Maeshowe (mays-HOW) was built around 3500 BC. From the outside, it looks like yet another big mound. But inside, the burial chamber is remarkably intact. The only way to go inside is on a fascinating 30-minute tour. You’ll squeeze through the entrance tunnel and emerge into a space designed for ancestor worship, surrounded by three smaller cells. At the winter solstice, the setting sun shines through the entrance tunnel, illuminating the entrance to the main cell. How they managed to cut and transport gigantic slabs of sandstone, then assemble this dry-stone, corbeled pyramid—all in an age before metal tools—still puzzles present-day engineers. Adding to this place’s mystique, in the 12th century, a band of Norsemen took shelter here for three days during a storm, and entertained themselves by carving runic messages into the walls—many of them still readable (£9, tours daily 10:00-16:00, tel. 01856/761-606, www.historicenvironment.scot/maeshowe). Reservations are required (book in person or online, but not by phone).

A narrow spit of land just a few hundred yards from Maeshowe is lined with several stunning, free-to-visit, always-“open” Neolithic sites (from Maeshowe, head south on the A-965 and immediately turn right onto the B-9056, following Bay of Skaill signs). Along this road, you’ll reach the following sites, in this order (watch for the brown signs). Conveniently, these line up on the way to Skara Brae.

Stones of Stenness: Three-and-a-half standing stones survive from an original 12 that formed a 100-foot-diameter ring. Dating from around 3000 BC, these are some of the oldest standing stones in Britain (a millennium older than Stonehenge).

Barnhouse Village: From the Stones of Stenness, a footpath continues through the field to the Barnhouse Village. Likely built around the same time as the Stones of Stenness, this was probably a residential area for the priests and custodians of the ceremonial monuments all around. Discovered in 1984, much of what you see today has been reconstructed—making this the least favorite site of archaeological purists. Still, it provides an illuminating contrast to Skara Brae (described later): While those Skara Brae homes were built underground, the ones at Barnhouse were thatched stone huts not unlike ones you still see around Great Britain today. The entire gathering was enclosed by a defensive wall.

Back on the road, just before the causeway between two lochs—saltwater on the left and freshwater on the right—two pillars flank the road (one intact, the other stubby). These formed a gateway of sorts to the important Neolithic structures just beyond.

Ness of Brodgar: On the left, look for a busy excavation site in action. The Ness of Brodgar offers an exciting opportunity to observe an actual archaeological dig in progress (discovered only in 2003). The work site you see covers only one-tenth of the entire complex, which was likely an ensemble of important ceremonial buildings...think of it as the “Orkney Vatican.” The biggest foundation, nicknamed “the Cathedral,” appears to have been a focal point for pilgrimages. Don’t be surprised if there’s no action—due to limited funding, archaeologists are likely at work here only in July and August (at other times, it’s carefully covered, with nothing to see). The archaeologists hope to raise enough funds to build a permanent visitors center. Free guided tours are sometimes available (July-Aug Mon-Fri at 11:00, 13:00, and 15:00, check www.nessofbrodgar.co.uk for details).

The Ring of Brodgat: Farther along on the left, look for stones capping a ridge above the road. The Ring of Brodgar is more than three times larger than the Stones of Stenness (and about 500 years newer). Of the original 60 or so stones—creating a circle as wide as a football field—25 still stand. The ring, which sits amidst a marshy moor, was surrounded by a henge (moat) that was 30 feet wide and 20 feet deep. Walking around the ring, notice that some are carved with “graffiti”—names of visitors from the late 19th century to the early 20th century, as well as some faint Norse runes carved by a Viking named Bjorn around AD 1150 (park 300 yards away, across the road).

At the far-eastern reaches of Mainland (about a 20-minute drive from Maeshowe), this remarkable site illustrates how some Neolithic people lived like rabbits in warrens—hunkered down in subterranean homes, connected by tunnels and lit only by whale-oil lamps. Uncovered by an 1850 windstorm, Skara Brae (meaning roughly “village under hills”) has been meticulously excavated and is very well-presented.

Cost and Hours: £9, daily 9:30-17:30, shorter hours Oct-March, last entry 45 minutes before closing, café and WCs, http://www.historicenvironment.scot.

Visiting Skara Brae: Begin your visit in the small exhibition hall, where you’ll watch a short film and see displays on Neolithic life. Then head out and walk inside a reconstructed home from Skara Brae—with a hearth, beds, storage area, and live-bait tanks dug into the floor. Finally, walk across a field to reach the site itself. Museum attendants stand by to answer any questions.

The oldest, standalone homes at Skara Brae were built around 3100 BC; a few centuries later, the complex was expanded and connected with tunnels. You’ll walk on a grassy ridge just above the complex, peering down into 10 partially ruined homes and the tunnels that connect them. For safety, all of this was covered with turf, with only two or three entrances and exits. Because sandstone is a natural insulator, these spaces—while cramped and dank—would have been warm and cozy during the frequent battering storms. If you see a grate, squint down into the darkness: A primitive sewer system, flushed by a rerouted stream, ran beneath all of the homes, functioning not too differently from modern sewers. And all of this was accomplished without the use of metal tools. They even created an ingenious system of giant stone slabs on pivots, allowing them to be opened and closed like modern doors.

Before leaving, look out over the nearby bay, and consider that this is only about one-third of the entire size of the original Skara Brae. What’s now a beach was once a freshwater loch. But with the rising Atlantic, the water became unusable. About 800 years after it was built, the village was abandoned; since then, most of it has been lost to the sea. This area is called Skaill Bay, from the Old Norse skål, for “cheers!”—during Viking times, this was a popular place for revelry...but the revelers had no clue they were partying on top of a Neolithic village.

And now for something completely different: Your ticket to Skara Brae also includes the Skaill House, the sprawling stone mansion on the nearby hilltop. Here you can tour some lived-in rooms (c. 1950) and see a fascinating hodgepodge of items once important to a leading Orkney family. Some items illustrate Orkney’s prime location for passing maritime trade: The dining room proudly displays Captain James Cook’s dinner service—bartered by his crew on their return voyage after the captain was killed in Hawaii (Orkney was the first place they made landfall in the UK). You’ll also see traditional Orkney chairs (with woven backs); in the library, an Old Norse “calendar”—a wooden stick that you could hold up to the horizon at sunset to determine the exact date; a Redcoat’s red coat from the Crimean War; a Spanish chest salvaged from a shipwreck; and some very “homely” (and supposedly haunted) bedrooms.

Nearby: About five miles south of Skara Brae, the sightseeing twofer of Yesnaby is worth a quick visit for drivers (watch for the turnoff on the B-9056). On a bluff overlooking the sea, you’ll find an old antiaircraft artillery battery from World War II, and some of Orkney’s most dramatic sea-cliff scenery.

For a quick and fascinating glimpse of Orkney’s World War II locations, worth ▲▲▲, drive 10 minutes south from Kirkwall on the A-961 (leave town toward St. Mary’s and St. Margaret’s Hope, past the Highland Park Distillery)—to the natural harbor called Scapa Flow (see the sidebar). From the village of St. Mary’s, you can cross over all four of the Churchill Barriers, with subtle reminders of war all around. The floor of Scapa Flow is littered with shipwrecks, and if you know where to look, you can still see many of them as you drive by.

Barrier #1 crosses from St. Mary’s to the Isle of Burray. This narrow channel is where, in the early days of World War II, the German U-47 slipped between sunken ships to attack the Royal Oak—demonstrating the need to build these barriers. Notice that the Churchill Barriers have two levels: smaller quarried stone down below, and huge concrete blocks on top.

Just over the first barrier, perched on the little rise on the left, is Orkney’s most fascinating wartime site: the Italian Chapel (£3, daily 9:00-18:30 in summer, shorter hours off-season). Italian POWs who were captured during the North African campaign (and imprisoned here on Orkney to work on the Churchill Barriers) were granted permission to create a Catholic chapel to remind them of their homeland. While the front view is a pretty Baroque facade, if you circle around you’ll see that the core of the structure is two prefab Nissen huts (similar to Quonset huts). Inside, you can see the remarkable craftsmanship of the artists who decorated the church. In 1943, Domenico Chiocchetti led the effort to create this house of worship, and personally painted the frescoes that adorn the interior. The ethereal Madonna e Bambino over the main altar is based on a small votive he had brought with him to war. An experienced ironworker named Palumbi used scrap metal (much of it scavenged from sunken WWI ships) to create the gate and chandeliers, while others used whatever basic materials they could to finish the details. (Notice the elegant corkscrew base of the baptismal font near the entrance; it’s actually a suspension spring coated in concrete.) These lovingly crafted details are a hope-filled symbol of the gentility and grace that can blossom even during brutal wartime. (And the British military is proud of this structure as an embodiment of Britain’s wartime ethic of treating POWs with care and respect.) Spend some time examining the details—such as the stained-glass windows, which are painted rather than leaded. The chapel was completed in 1944, just two months before the men who built it were sent home. Chiocchetti returned for a visit in the 1960s, bringing with him the wood-carved Stations of the Cross that now hang in the nave.

Continuing south along the road, you’ll cross over two more barriers in rapid succession. You’ll see the masts and hulls of shipwrecks (on the left) scuttled here during World War I to block the harbor. As you cross over the bridges, notice that these are solid barriers, with no water circulation—in fact, the water level on each side of the barrier varies slightly, since the tide differs by an hour and a half.

At the far end of Barrier #3, on the left, watch for the huge wooden boxes on the beach. These were used in pre-barrier times (WWI) for boom floats, which supported nets designed to block German submarines.

After Barrier #3, as you climb the hill, watch for the pullout on the right with an orientation board. From this viewpoint, you can see three of the Churchill Barriers in one grand panorama.

Carrying on south, the next barrier isn’t a Churchill Barrier at all—it’s an ayre, a causeway that was built during the Viking period.

Finally you’ll reach Barrier #4—hard to recognize because so much sand has accumulated on its east side (look for the giant breakwater blocks). Surveying the dunes along this barrier, notice the crooked concrete shed poking up—actually the top of a shipwreck. The far side of this sand dune is one of Orkney’s best beaches—sheltered and scenic.

From here, the A-961 continues south past St. Margaret’s Hope (where the ferry to Gills Bay departs) and all the way to Burwick, at the southern tip of South Ronaldsay. From here you can see the tip of Scotland. Nearby is the Tomb of the Eagles, a burial cairn similar to Maeshowe, but less accessible (time-consuming visit, www.tomboftheeagles.co.uk).

More WWII Sites: For those really interested in the World War II scene, consider a ferry trip out to the Isle of Hoy; the main settlement, Lyness, has the Scapa Flow Visitors Centre and cemetery (https://hoyorkney.com). Near Lyness alone are some 37 Luftwaffe crash sites. A tall hill, called Wee Fea, was hollowed out to hold 100,000 tons of fuel oil. Also on Hoy, you can hike seven miles round-trip to the iconic Old Man of Hoy—a 450-foot-high sea stack in front of Britain’s tallest vertical sea cliffs. (Or you can see the same thing for free from the deck of the Stromness-Scrabster ferry.)

With more time, check out these two towns with connections to northern Scotland. Stromness is Orkney’s “second city,” with 3,000 people. It’s a stony 17th-century fishing town and worth a look. Equal parts fishing town and tourist depot, its traffic-free main drag has a certain salty charm. If driving, there’s easy parking at the harbor. If catching the ferry to Scrabster, get here early to enjoy a stroll.

St. Margaret’s Hope—named for a 13th-century Norwegian princess who was briefly Queen of Scots until she died en route to Orkney—is even smaller, with a charming seafront-village atmosphere. Ferries leave here for Gills Bay.