Ceux qui n’ont inventé ni la poudre ni la boussole

Ceux qui n’ont jamais su dompter la vapeur ni l’électricité

Ceux qui n’ont exploré ni les mers ni le ciel

mais ils savent en ses moindres recoins le pays de souffrance1

Those who invented neither powder nor compass

those who could harness neither steam nor electricity

those who explored neither the seas nor the sky

but who know in its most minute corners the land of suffering2

These lines by the poet laureate of Negritude present what might very well contain the most powerful, most harmful, and most ubiquitous stereotype of black subjectivity to inhabit the French imaginary of the twentieth century. Caribbeans, Africans, and black Americans living in Paris between the two world wars would have been exposed to this image: the black man “indifferent to conquering” (“insoucieux de dompter”), lacking initiative (“who could harness neither steam nor electricity”), in continuity with the very matter of the world (“flesh of the world’s flesh”).3 Not surprisingly, we find almost the same words penned by Léon-Gontran Damas a few years earlier: “De n’avoir jusqu’ici rien fait / détruit bâti / osé” (“Never, until now, to have done anything / destroyed built / dared anything”), he laments in his 1934 poem “Réalité.” Marcel Cohen, a professor of linguistics at the Institut d’Ethnographie where Damas was a student, taught that African peoples were “sans écriture” (without writing); their societies were poor in technologies of all kinds.4 Clearly, in the 1930s the black subject of the diaspora would have had to combat the racial stereotype—one among many—according to which possessing African ancestry means suffering an attenuated relation to all advanced technologies, including writing. Writing, the story goes, is an acquisition belonging to the mediosphere of modern Western man alone.

Ironically, however, before setting foot in France in 1926, Damas would have thought of himself as a full, card-carrying member of the modern mediosphere of writing and the printing press.5 Born in 1912 in French Guiana, Damas was an exemplary product of the assimilation policies imposed by the French. He followed almost the same trajectory as Césaire (they even attended the same English class), having left Guiana in 1924 to attend the Lycée Schoelcher in Fort-de-France. He arrived in France in 1926 to complete his secondary studies at the Collège de Meaux, then attended classes on law and finally ethnography at the Institut d’Ethnographie. The recipient of an education “très français français,” as Damas would say, he had every reason to believe that writing—and thus print culture—belonged to him just as much as it did to all the other offspring of “nos ancêtres les gaulois.” The overseas colonial institutions of France promoted the basic principle that black schoolchildren (and certainly mulattos, or métis) could learn to read and write and that eventually they would be able to intervene productively in the administrative, political, and professional arenas of French life. (Of course, in reality, this principle was not always applied, and equal opportunities were rarely meted out to all.6)

It was thus upon disembarking in France that Damas confronted a blanket policy of discrimination that no longer distinguished between educated assimilés and low-class nègres but instead bundled them all together, either in the embrace of “negrophilia” or in the chains of disgrace.7 This far less subtle racial hierarchy associated even the mulatto assimilé more closely with black Africa and its mediosphere (supposedly “without writing”) than with the advanced scriptural mediosphere of the industrialized West. According to the view that would have dominated at the time, the young Guyanese belonged not to a cultural elite but rather to a Negro race having never “done anything / destroyed built / dared anything.” Damas and his fellow Caribbeans suddenly found themselves deprived—in the eyes of their white compatriots—of any scriptural tradition whatsoever. Césaire and the students associated with the review L’Étudiant Noir quickly realized that this state of affairs left them with only two ways to respond: either they could deny their own cultural specificity (a mélange of Amer-Indian, East Indian, African, and European influences) and strive to express themselves in an impeccable “français français,” or—a much riskier venture—they could choose to explore their cultural specificity by reaching out to cultural traditions that were only imaginatively their own (such as African American music or African religious beliefs). Césaire and Damas forged a third route. While responding to Étienne Léro’s call in Légitime Défense of 1932 to reject the mimicry of “white culture, white education and white prejudices,” they set out to further a singularly Caribbean agenda that includes embracing the means and techniques of Western print.8

Benedict Anderson has argued persuasively in Imagined Communities that print culture played a major role in the development of modern Europe and thus, by corollary, in the construction of the colonial assimilationist project. A circulating print culture was the condition of possibility for the emergence not only of the political structures we call the nation but also of the sentiment of belonging to a collectivity defining itself primarily as a linguistic readership rather than a racial or even geographical body. It would be hard to overestimate the importance of print culture as a distribution system across regional and national boundaries; it contributed, according to Anderson, to the inception of the modern subject and defined this subject’s place in the public sphere.9 Building on Anderson’s work, Brent Hayes Edwards has demonstrated in The Practice of Diaspora that the social and aesthetic formation we call Negritude would never have seen the light of day without the mediating potential of print culture, its modes of distribution and material supports. The print network connecting Africans, African Americans, and Caribbeans, created by the transatlantic circulation of multiple reviews and translations, was absolutely indispensable to the production of a Pan-African solidarity—particularly the solidarity that characterizes Negritude as an engaged poetics. As Edwards avers, “the periodical print cultures of black internationalism were robust and extremely diverse on all sides of the Atlantic,” and translation of texts from English to French—and vice versa—was at the heart of the movement that revolutionized literature on both sides of the ocean.10 From Les Continents and La Voix des Nègres to L’Etudiant Noir and Présence Africaine, it was the mediosphere of writing technologies that permitted black affirmation movements to formulate a collective imaginary, one shared by peoples widely dispersed but drawn together by a common project articulated in print.

It was thus through means furnished above all by what Jean-Pierre Bobillot has called the “typosphere” that black writers and militants found it possible to explore their racial and cultural bonds. In this regard, it is worth noting that francophone black writers living in Paris, despite their familiarity with a varied and animated black popular culture, tended to associate their cultural project more closely with political and literary print matter than with jazz or the Bal Nègre. Damas and Senghor were admirers of African American jazz (and, with varying familiarity, Caribbean biguine and Serer drumming), but their respective styles reflect more consistently either the elevated diction of modern French poetry (from Baudelaire to Saint-John Perse), or the discourse forged by the militant black press (Le Cri des Nègres and La Race Nègre). In short, with few exceptions, it was the typosphere that afforded the tools with which Senghor, Césaire, and Damas interrogated and defined what they understood to be their racial voice and cultural values.

However, each writer of Negritude envisioned his task in a slightly different fashion. As I argued in chapter 1, Césaire sought to explore all the resources of the French language as it resonated in his local environment, which included a reading environment. His project involved bending (“infléchir” is his verb) the French language such that it could accommodate (while constituting in print form) “ce moi, ce moi-nègre, ce moi-créole, ce moi-martiniquais, ce moi-antillais.”11 Senghor, in contrast, desired to produce poems that would lend themselves to a musical scansion; he claims to have modeled his poetic meters on rhythms that were African in origin. (We will come back to this point later.) Finally, for Damas, the task of the poet consisted in forging a written language capable of incarnating visually as well as through text-produced sound the “stutter” (“bégaiement”) or “hiccup” (“hoquet”) that he associates with the profoundly negative experience of assimilation. According to Damas, assimilation could produce nothing other than a man out of step (“en syncope”) with his own essence, nothing other than a voice trapped in repetitious behaviors that could only be made expressive through their formal exaggeration.12 He turned to the medium of modernist print to capture what Frantz Fanon would later call the Leib noir of the assimilé, according great expressive power to the typographic support.13 Exploring experimental techniques for lineation and layout, Damas transformed the page itself into a site where a lack of essence, a negative ontology of the self, could be graphically staged and realized as a sonic positivity by the reader.

Damas was not alone in emphasizing the value of print culture for black self-expression and resistance. Despite the enormous interest the Negritude poets expressed in African and African-inspired traditions, they do not seem to have aspired to practice orality in some putatively pure, pre-textual form. That is, although Negritude poets often drew attention to the rhythms of incantation, the refrain of the blues, or the narrative structure of the griot tale (either thematically or through verbal mime), they did not choose to produce or reproduce oral genres. It is indeed striking that during the interwar period not a single Negritude author developed a poetics of orality that was actualized in an exclusively oral form. The primary gesture toward orature remained that of the ethnographer: in 1943 Damas published a collection of Guyanese tales titled Veillées noires and, in 1948, Poèmes nègres sur des airs africains, a volume of African poems translated into French. Even if oral recitation was a widespread practice, and the orality of the griot or the musicality of the blues won unanimous praise, poets in general declined to produce verbal works that could not also play a significant role in the typosphere of modernity.14

The poets of Negritude may have stated that forms of orature, music, or dance were more authentically African, less corrupted by the colonial or diasporic experience, but they were decidedly writers invested in publishing texts. In fact, even when Damas collected African poems and published them under the title Poèmes nègres sur des airs africains, he did not present these “airs” as reconstitutions of some pre-lapserian ideal African world untouched by print culture.15 In contrast to Blaise Cendrars’s Anthologie nègre of 1921, Damas’s collection clearly registers the signs of European intervention. References to current events underscore the topical and evolving nature of supposedly “traditional” genres; whites are mentioned frequently, as in “Jamais Plus” and “Chants Funèbre”; and the page layout of the “airs” (as well as their verse structure) is modeled on European textual conventions. Similarly, although Senghor expresses admiration for the instruments of his native Senegal, and although he indicates at the head of each poem of Éthiopiques which instrument(s) should accompany which poem (the khalam, a tetracord guitar; the tabala, a war drum; the harp-like kôras; or the xylophone balafong), the poem still exists as a textual and not sonic entity in its first circulated form. In his preface to the poetic volume Éthiopiques, Senghor explicitly emphasizes that “reciting” is not “singing”; his poetry is a “mixed” form (“forme métissée”), he states, exposing a marked bias for “French” and French in print as singularly appropriate to the “expression” of what is nonetheless felt “en nègres.”16

Ostensibly, then, the preferred medium of Negritude was print, the preferred mediasphere—or organ of commercial distribution—the “revue,” the philosophical meditation, and the ethnographic tome, and—most importantly—the collection of poems. However, at the same time, and somewhat paradoxically, the poets of Negritude charged print (and French) with the responsibility of translating sound phenomena into written words. Text-based poetry now had to preserve the rhythm of the tom-tom (Senghor), the phrasing of blues and the melopoeia of song (Damas and Senghor), and the repetitive structure of chant (Césaire). A fact that has rarely been observed is that the poetry of this period constitutes one of the most rigorous, ambitious, and persistent attempts to generate graphic and graphemic equivalents for phenomena claimed to be of a fundamentally aural kind. If critics have often drawn attention to the “musicality” of a verse by Senghor or the calypso-like rhythm of a stanza by Damas, they have not yet fully inventoried the ways in which efforts to actualize sound in print influenced the evolution of the French lyric itself. The original practices that Damas in particular developed over the course of the mid-twentieth century opened up new possibilities for using typography and mise en page to represent but also produce sound. That is, Damas’s experimentation in the typosphere gave birth not to copies of verbal performance but to purely graphic means for symbolizing patterns that might have had no prior equivalent in the sonic realm.

Of course, the project of securing visual equivalents for aural phenomena is intrinsic to the poetics of the printed poem in general. However, it is also true that this project was taken up with renewed enthusiasm both by poets of the Harlem Renaissance and in the diasporic milieux of early twentieth-century Paris. As this project of remediation evolved, it began to grow the seeds of its own inversion. In other words, once the poet was able to create effective graphic means of evoking sound, the affective charge of enunciation could be transferred to the act of reading, thereby eliminating the need to recite. Ironically, then, the poet most concerned with aurality might also turn out to be the poet most distant from, least similar to, an oral poet. His technical understanding of the printed page distinguishes him from the griot and the dyâli; the printed poem that results from such technical understanding functions according to different strategies and conventions than a poem composed in the mouth and intended to be chanted out loud. Of course, nothing would prevent Negritude poets (and their readers) from reading a poem out loud, but such a reading would no longer be necessary, innovations in print having already visually incarnated the rhythms to the point where the verbal form could exist entirely without vocalization. Lesley Wheeler has argued persuasively that even silent reading (or “subvocalization”) engages the vocal cords in an active way, a point that I discussed in chapter 1 and that we will explore more thoroughly in the next chapter.17 But if subvocalization occurs during the silent reading of a poem by, say, Damas, this reading effectively transforms the reading body into the originary source of sound (here an imagined rather than actualized sound), a sequence produced on the page and thus subject to variation. Instead of being a transcription of a rhythm heard, the Negritude poem is a text from which performances may spring. In the hands (or mouths) of readers, the poem produces what Henri Meschonnic calls “ré-énonciations,” instantiations driven by the directives woven into the poem.18 These directives—line breaks, spatialization of words, font size and weight, diacritical marks—orient the initiated reader of print to vocalize (or subvocalize) a piece of printed matter in a particular way (although variations always occur). The printed poem can actually engender (and not simply convey) experience, producing in the reader a variant sensation of the Leib noir as an epiphenomenon of transmission. This is emphatically not to say that experience is “constructed” by its reenunciation but rather that it is altered in iteration, animated in performance, in ways that an author cannot entirely control.

“THE GAME OF BLACK AND WHITE”

Among the three poets of Negritude, Damas most clearly understood the possibilities of modern print culture and best exploited its political and aesthetic resources. It was Damas who participated in the first literary reviews dedicated to Pan-African solidarity—La Revue du Monde Noir; Légitime Défense; and L’Étudiant Noir.19 Again, it was Damas who made use of print (as had René Maran) to disseminate an ethnographic and historical study of a colony eviscerated by administrative abuse (Retour de Guyane, 1938). Yet again, it was Damas who produced the first anthology of francophone poetry in 1947 (Poètes d’expression française d’Afrique noire, Madagascar, Réunion, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Indochine, Guyane 1900–1945), even before Senghor’s more famous anthology appeared in 1948. And finally, it was Damas who published the first volume of poetry written by a man explicitly—and thus politically—nègre: Pigments, in 1937. If Césaire adopted (and transformed) the syllabic poetics of Rimbaud and the surrealist poetics of rapprochement, and if Senghor based his prosody on the rhythms of a supposedly racial heritage, Damas took hold of the graphic possibilities of the printing press, of spacing and typography, to elaborate a poetics of negativity capable of transmitting the peculiar facticity of the assimilé.

From the very beginning of his career, Damas distinguished himself from the Caribbean poets of the past by imitating the verse structure, the style of diction, the tone, and even the syntax of African American writing. Of the three major Negritude poets, Damas was closest to the African American poets living in or passing through Paris; his friendships with Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen probably account for his singular position in the field of Parisian cultural production as well as his greater interest in the possibilities of modernist print. Damas’s short, syntactically repetitive, appositive lines evoke in particular those of Langston Hughes, who in turn shared a number of syntactical innovations with Jacques Roumain. It is well established that Roumain, Damas’s classmate at the Institut d’Ethnographie, and Hughes, a fellow traveler from 1938 on, were both instrumental in his evolution as a writer.20 According to biographical accounts, Damas began writing around 1926, a date that coincides with the appearance of The Weary Blues of Langston Hughes, not to mention, a few months later, the publication of the first poems by Jacques Roumains in La Revue Indigène. Although Damas’s experimentation with typography culminated in 1962 (when he published what he called his “définitive” version of Pigments), he was already imitating typographic innovations introduced by Roumain and Hughes in the first version of 1934.21 Unique among the Negritude poets, Damas abandoned traditional verse structures early on in order to take fuller advantage of the printed page, treating it increasingly as a plastic and symbolically charged support.

Yet another connection with African American writers might have influenced the course of his career, awakening in him a greater interest in typographic experiment as a potential form of subversion. Damas’s first collection, Pigments, was published by the foremost printer of surrealist books, Guy Lévis Mano, who owned Éditions GLM, a publishing house central to the interwar field of modernist production. Lévis Mano, a printer-cum-editor, was known to conceive of his typesetting work as “a typographic ‘interpretation’ of the text.”22 During the interwar period, Lévis Mano was responsible for publishing the most typographically experimental work by poets and artists of the French avant-garde, from René Char to Joan Miró, Paul Éluard to Man Ray. Damas had perhaps heard news of Lévis Mano through his surrealist friends (most likely Robert Desnos or Jacques Prévert). But it is equally possible that he knew of the printer’s work through the African American poets who were also part of his circle. Lévis Mano inherited his printing press in 1935, a Minerva “à pédale,” from none other than Nancy Cunard, the heiress and mécène of black writers.23 The acquisition of this Minerva permitted Lévis Mano to print surrealist works on the press that had produced texts over the previous decade by high modernists such as Samuel Beckett, Ezra Pound, and Laura Riding. The links between anglophone and francophone print culture, between international modernism and the origins of Negritude, were thus material as well as aesthetic. Cunard, Lévis Mano, and the writers they published shared an investment in the expressive potential of typography. Damas, alone among the Negritude poets, joined this company, becoming a member of the cohort that, according to Jerome McGann, “fashioned the bibliographical face of the modernist world.”24

Clearly, Damas, who published Pigments at his own expense, did not choose Éditions GLM at random. He must have selected the printer out of a sense of affinity with the typographical experimentation he witnessed in both surrealist and Harlem Renaissance publications. However, it is likely that Damas was able to interest Lévis Mano in his poems for more than aesthetic reasons. French surrealists as well as expatriot Americans like Cunard nourished a fascination with the exotic, and especially the “primitive” Negro, a fascination that may have worked, in this case, to his advantage. But Damas was by no means adapting to some imposed aesthetic identity manufactured by either milieux. A brief glance at his first published poems reveals that as early as 1934 (even before Pigments appeared), Damas was already developing a unique writing style. In “Réalité,” for instance, the poem I will take as my first example, Damas has to span the distance between his own experience as a black assimilé and the popularized image of the savage, the subject who has never “done” or “built” any lasting thing. Published for the first time in Esprit (an organ of the Christian Left run by Emmanuel Mounier), “Réalité” is one of five poems—“Solde” (Sell out), “La complainte du nègre” (The Negro’s complaint), “Un clochard m’a demandé dix sous” (A beggar asked me for ten cents), and “Cayenne 1927”—that propelled Damas onto the French literary scene. But before he could accede to the status of high modernist by publishing in the modernist mainstream, Damas had to wage battle against the stereotype of his own incapacity, promoted even in Esprit—and this, of course, is one of the ironies of “Réalité”:

RÉALITÉ

De n’avoir jusqu’ici rien fait

détruit bâti

osé

à la manière du Juif

du Jaune

pour l’évasion organisée en masse

de l’infériorité

c’est en vain que je cherche

le creux

d’une épaule où

cacher mon visage

ma honte

REALITY

To have never until now done

destroyed built

like a Jew

like a Chinaman

for the organized flight en masse

of inferiority

it is in vain that I seek

the hollow

of a shoulder

to hide my face

my shame

Before taking a closer look at “Réalité,” it is worth pausing to consider the way the poem was initially presented by the editors of Esprit. A short preface by Marcel Moré frames the five poems contributed by Damas. Titled simply “Poèmes de Léon Damas,” Moré’s preface tells us how he came to know the poet, as if their encounter—and the presence of Damas’s poems in the review—required explanation. Apparently, Moré was inspired to attend the projection of a short film, “Voodoo Magic,” upon finishing L’Afrique fantôme by Michel Leiris (another classmate of Damas’s at the Institut d’Ethnographie). Damas, as it happens, was also at the screening. Afterward Moré and Damas began to converse and decided to cross together the Buttes-Chaumont Park. In a chain of familiar associations, the Buttes-Chaumont Park reminds Moré of Aragon’s Paysan de Paris, in which the park is surrealistically described. These two allusions—to L’Afrique fantôme and Paysan de Paris—could not be more loaded, for they situate Damas squarely in a prefabricated context of ethnographic surrealist exoticism.27 It is not surprising, then, that Moré proceeds to gush over the “nouveauté” (“novelty”)—but also the “facilité” (“facility,” or “facile nature”)—of the poems Damas has contributed. These poems—significantly, for our purposes—appear to Moré to have been “dictated by the rhythm of a tom-tom.”28 Damas is thus framed by a stereotype even before he can begin to be read. He enters the interwar Parisian field of cultural production as the consumate “African,” despite his actual birth as a métissé in French Guiana (indicated to the readers by the direct allusion to its capital, Cayenne, in the title of one of the poems). The fact that Damas had probably never in his life played a tom-tom, and that he found his avatars not in the African bush but in the French and American lyric traditions, does not seem to have played the slightest role in his reception by the editors of Esprit. Moré’s short text efficiently establishes the lens through which Damas would be read by a long line of critics from Senghor to scholars of the present day.29 As Moré puts it, Damas, “with no political axe to grind … yearns only to be ‘nègre,’” and “nègres,” as everyone knows, play tom-toms and use print merely to evoke tom-toms for their reader’s ear.30

The poem, however, contradicts each claim Moré makes (“no political axe to grind”?). Right away, in a gesture that will soon be associated with the politics of Césaire’s Cahier d’un retour au pays natal, Damas identifies the speaker (Moré’s “l’être nègre”) not with an African body but rather with the “essence” of two other oppressed groups—the “Juif” and the “Jaune” (the Jew and the Chinaman). However, the solidarity among the three groups depends upon a common contingency, not a shared blood. In an important image, Damas tells us that “the manner” of the “Juif,” “Jaune,” and, by implication, the speaker—that is, their shared “essence” or “way of being”—consists in a tendency to evade (“l’évasion”): “pour l’évasion organisée en masse/de l’infériorité.” Looking at this image for the first time, one might be tempted to read “evasion” as eluding responsibility, as running away. And indeed, this form of “evasion” finds its gestural equivalent in the search for a hollow in which to hide (“un creux … [où se] cacher”). Yet a second glance suggests that this interpretation is misleading. Damas is, after all, printing these poems in an anticapitalist review. The word “masse” (in “organisée en masse”) would clearly evoke a very specific meaning for readers of Esprit. In fact, the medialogical context of “Réalité” invites us to read “evasion” in a much stronger sense—“evasion” as “escape from confinement,” as uprising, as revolt. From this angle, the verse seems more like a call to insurrection than a description of defection. The shame (“honte”) of which the poet speaks is inspired not by some purported “infériorité” but rather by the fact that he has not yet “done” anything “for” the evasion: “pour une evasion organisée en masse.”

The versification of the poem compounds the sense of imminent escape. Damas is careful to draw the reader’s eyes neither to the repeated past participles (with the exception of “osé”) nor to the agents of the poem in their singular, if repeated, form (the Juif or the Jaune). Instead, the eyes are drawn to the description of the act of evading: “pour l’évasion organisée en masse” is the longest verse of the poem. The other, shorter lines of the poem appear as if they wished to escape toward the spine of the volume; they cling to this spine, collapse into it, with the exception of “pour l’évasion organisée en masse” which extends its length toward the blank space on the right side of the page. Evasion, after all, is an act that takes place in space; it refers to an escape that is at the very same time an assumption of power, a kind of marronnage, escaping to the “morne” of Martinique to stage a rebellion, or, at least, to live a different way. Damas’s poem may sound to Moré like a tom-tom, but it references the “reality” of an assimilated Guyanese who confronts in turn oppression (described in “Un clochard m’a demandé dix sous”), servitude (described in “La complainte du nègre”), and colonial mimicry (the theme de “Solde”).

What the readers of Esprit might not have been able comprehend (especially after reading Moré’s preface) is that Damas is presenting his “negro being” (“être nègre”) as implicated in his specificity as a Caribbean Guyanese. The shame to which he confesses results from inaction, from lack of connection. As the poem implies through synecdoche, his plight as an assimilé involves an inability to find solidarity with others, represented here by a comforting—but absent—body: “le creux d’une épaule.”31 His shame (“la honte”) might be related to his current passivity and alienation. At the same time, however, to avow this alienation is to rise up, to initiate an eventual “évasion organisée en masse.” Damas is presenting here in its most concentrated and concise form the primary poetic mechanism, the tiny but potent rhetorical bomb not only of his own poetry but also of Césaire’s. For the Cahier, too, is articulated—albeit more gregariously—as a debasement (“la négraille”) that simultaneously uplifts. “Réalité” is, in embryonic form, the model of Martiniquan Negritude: it performs the typical Negritude gesture in which a subject repeats an insult (“nègre”) until that insult is emptied of its pejorative connotations and produces a neologism—a substantive with no essence—like the word “Negritude.” Damas’s poem—similar to the neologism “négritude”—is a speech act that exposes shame in order to generate revolt. It is a performance in which the speaker removes his mask not to proclaim authenticity but to take up arms.

Whereas Césaire engages in expansive imagery and the build-up of momentum over many pages, Damas employs irony, understatement, and—equally important—the spatial relation among words on one page to establish an equivalence between confession and resistance. That is, Damas carefully uses the paper support to invent what might be called a graphic irony born of an astute manipulation of letters in space. To give just one example from “Réalité,” with respect to line 4, we can observe that Damas has taken pains to distance the past participle “osé” (“dared”) as far as possible from its auxiliary verb, “avoir”: “De n’avoir rien” appears in the first verse, “osé” in the fourth. Damas has expressly isolated “osé” on the page; by doing so, he casts doubt on the meaning of the word itself. “Osé” can be read as a past participle or as an adjective qualifying “Juif” and “Jaune”; in the latter case, the sentence reads, “osé à la manière d’un Juif / d’un Jaune” (daring in the manner of a Jew / of a Chinaman). The distance between the auxiliary infinitive and the past participle is augmented by the versification; the space of the page is working to offer an alternate reading, one that is in conflict with the first. Clearly, Damas is attending to the appearance of his poem (and not just its sonority). This appearance, the way in which the poem offers itself to the eye, permits him to play with the ambiguity of a word, to evoke several ways of understanding an utterance, and thus to trouble the transparent relation between spoken word and written letter presupposed by Moré’s preface and its metaphor of “dictation.”

Admittedly, these innovations on the level of the mise en page are quite modest. It is as though in 1934 Damas were still testing out his muscles, trying to discover what kind of effects he could obtain from small shifts in spacing or different enjambments of the line. In the 1937 GLM edition of Pigments, Damas goes much further, resetting verses and sometimes even the letters of poems such as “Réalité.” For instance, in “Ils sont venus ce soir” (They came that evening), Damas inaugurates a manner of spacing his words along a kind of invisible descending staircase, an avant-garde typographical procedure he most likely learned from Hughes (and which he applies to the 1962 versions of “Captation,” “Le vent,” “Limbé,” “S.O.S.,” and “Shine”). It turns out that the modest strategies Damas develops in 1937 are simply a prelude to a more thorough exploration of the possibilities afforded by the modernist typosphere. One need only consider the resetting of “Réalité” in the 1962 edition to seize immediately how much more “osé” Damas has become.

RÉALITÉ

De n’avoir jusqu’ici rien fait

détruit

bâti

osé

du Juif

du Jaune

pour l’évasion organisée en masse

de l’infériorité

C’est en vain que je cherche

le creux d’une épaule

où cacher mon visage

ma honte

de

la

Ré

a

li

té

What might have inspired Damas to atomize the syllables of “Réalité” and drop them down the page like staircase steps? Damas’s own creativity was considerable; however, it is also clear that between 1934 and 1962 (that is, between the first and the third typesetting of “Réalité”) Damas absorbed a good many typographic innovations introduced by, among others, his friend Langston Hughes. It is worth recalling that Hughes first used this “staircase technique” in The Weary Blues (1926) in a poem titled “Fantasy in Purple.” However, the “staircase technique” or “vers en escalier,” as it is known in French, has a long history in French lyric poetry. Mallarmé made the technique famous in “Un Coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard” of 1897, but Jules Laforgue had already graduated his lines in a similar way in L’imitation de notre-dame la lune of 1885. Guillaume Apollinaire advanced the technique yet further in Calligrammes (1918). Perhaps Damas had seen the “vers escalier” in Vladimir Mayakovsky’s “Vo ves’ golos” (1930), translated by Louis Aragon into French as “À pleine voix” in 1933 (Aragon also translated poems by Langston Hughes). While Damas employs the “vers en escalier” in a rather classical fashion in several of his poems, the typographic reformatting of “Réalité” introduces a new twist. Here it is not complete words that descend the page from left to right (as in Hughes’s poem); rather, it is individual letters or letter clusters that float down the page, a practice that strangely disrupts the perceptual norm of reading. Damas often performs this type of syllabic découpage to produce a parodic effect, as we see vividly in the case of “Shine,” where the words are cut up as in a dictionary to form sequences of syllables that descend the page:

por-

no-

gra-

phie

In “Shine,” the word parts are followed by dashes connecting one to the next, reminiscent of the way lexemes are presented in the dictionary, that archive par excellence of the typosphere. However, in “Réalité,” the connective tissue of punctuation has disappeared, leaving only the bare bones of fragments floating in space. At the time, Damas was not the only poet working with such fragments. In 1934, the same year that Esprit printed the first version of “Réalité,” Hughes published a poem titled “Cubes” in the Marxist review New Masses.32 “Cubes,” while not identical to Damas’s poem, still suggests a similar intent; Hughes also atomizes the letters of words, but he forms these letters into an undulating wave. Both authors employ a subversive strategy that consists in imitating in exaggerated fashion the perceptual conventions of writing and reading—the letteral regime of inscription—to the point where these very conventions produce the opposite of unimpeded literacy: the left-to-right movement of the eye is mobilized to complicate a clear and unidirectional presentation of meaning. The atomization of sound units facilitated by alphabetic writing ends up working against the unity of the word on the page. Typography, then, becomes a medium in which to expose what Hughes will call the “disease” of civilization, a hyper-rationalization that, when pushed to its extreme, produces a fixation on the grapheme that disrupts the conventional use of textual space. (See the original page of New Masses at www.faculty.sites.uci.edu/aestheticsubjectivity/.)

CUBES

In the days of the broken cubes of Picasso

And in the days of the broken songs of the young men

A little too drunk to sing

A little too unsure of love to love—

I met on the boulevards of Paris

An African from Senegal

God

Knows why the French

Amuse themselves bringing to Paris

Negroes from Senegal.

It’s the old game of the boss and the bossed,

boss and the bossed,

amused

and

amusing,

worked and working,

Behind the cubes of black and white,

black and white,

black and white

But since it is the old game,

For fun

They give him the three old prostitutes of

France—

Liberty, Equality, Fraternity—

And all three of ’em sick

In spite of the tax to the government

And the legal houses

And the doctors

And the Marseillaise.

Of course, the young African from Senegal

Carries back from Paris

A little more disease

To spread among the black girls in the palm huts.

He brings them as a gift

disease—

disease—

From the boss to the bossed

disease—

From the game of black and white

disease

From the city of the broken cubes of Picasso

d

i

s

e

a

s

e

The historical frame of the poem appears at first to be the arrival of Senegalese soldiers in Paris (the 200,000 tirailleurs sénégalais who fought in World War I) and their eventual return to Africa, infected by the European “disease.” However, a closer look reveals that there is in fact an even larger frame: the triangular commerce of empire. This commerce included the transport of African objects into France, without which cubism, the movement alluded to in the title, would never have evolved the way it did.33 The circulation between the two continents of goods and men—and men as goods—is the backdrop against which Hughes stages a trenchant critique of such aesthetics. The poet appears to be making a claim about the relation of modernist aesthetics (cubism in particular) to colonization and imperial rule; he is even suggesting that the typographic experimentation practiced by the cubists (and by the black poets who come after them) ultimately derives from the slave trade as well. On this reading, the “disease” of modernity, here visualized as an almost corporeal fragmentation, attacks the Senegalese soldiers, the cubist artists, and—by implication—the poet too.

Underscoring the image of the “broken cubes of Picasso,” Lesley Wheeler has also proposed that the allusion to cubism contains a sharp rebuke. On the one hand, she states, the poem indexes the experimentation of both Picasso and Apollinaire; with typographic sophistication, it investigates (as do cubist works) the difference between the linear temporality of reading and the simultaneity of the gaze, the aural function of poetry and its graphic form.34 To that extent, “Cubes” is a modernist poem, fully implicated in—and an accomplished example of—the aesthetics of fragmentation that cubism introduced. On the other, Wheeler continues, the allusion to the cubists in the context of imperial power condemns their complicity with a circulation of (human) objects that could only result from European incursion into African space. Picasso and Apollinaire were members of the generation that “discovered” and promoted l’art nègre; they drew African tribal (and tourist) objects into the limelight but they also made profitable use of a decontextualized heritage that was not their own. Thus, the fragmentation of the word “disease” in Hughes’s “Cubes” serves many purposes at once: it allows Hughes to mime the cubist gesture that accentuates the visual aspect of writing, and it offers an implicit critique of the imperialism that made it possible to do so in the first place. Because the poem ultimately associates experimental techniques (including typographic ones) with “disease”—“the game of black and white” as well as the “broken cubes”—it stands as an acerbic commentary on two incompatible realities: (1) that the poet is an accomplice, insofar as he benefits aesthetically from the same conditions of possibility (imperialism) as do the cubists; and (2) that the poet is a victim, conscious as no white modernist could ever be of the ravages slavery’s “disease” has wrought.

In “Cubes,” Hughes uses the “staircase” technique repeatedly: the word “disease,” for instance, is repeated three times in six lines, appearing each time slightly further to the right. At the same time, he also uses indented words to create shapes, such as the hourglass produced by “amused / and / amusing,” which could easily be an allusion to Apollinaire. The irony here is that the critics who have noted the use of patterned lineation in Hughes or Damas have consistently related such patterning to the putative musicality of their poems. Black poets, the story goes, always base the visual rhythms of their writing on the aural rhythms of jazz, the tom-tom, or the calypso; accordingly, a poem written by a black author should be able to be read like a musical score. But Hughes’s “Cubes” directly links such scribal experimentation to the attempt on the part of the cubist poets to render poetry more graphic, not the attempt of black poets to render poetry more sonorous. Further, instead of producing a musical score, the typographic layout seems to ask whether it is in fact possible to find a sonic counterpart to the staircase of words—or, for that matter, to the string of letters that ends the poem. How are these sequences to be pronounced? How are we to subvocalize them in our minds or mouths?

Both Damas and Hughes tend, therefore, not to fortify but rather to undermine the supposedly intimate connection between the written and the aural—and, even more surprisingly, between the aural and the African. The mastery displayed in “Cubes,” for instance, is clearly a mastery of the printed page, not the musical instrument. The poet places himself on the side of inscription while, on the thematic level at least, the allusion to the Marseillaise associates song and music not with the Senegalese but rather with the French. Hughes chooses to place the word “Marseillaise” in italics, stressing the convention that allows diacritical decisions to convey information. “Cubes” cultivates our sensitivity to typography as information, and the italics of “Marseillaise” prepare us to read other elements of the poem as possessing a graphic identity, such as the repeated s’s of “disease” which serve as miniature versions of the undulating, snaking “s” shape of the curling last lines (d / i / s / e / a / s / e). Everything in the poem urges us to look at—not listen to—the figures on the page. An exaggerated use of what the printed text allows ends up shifting our perceptual mode away from reading a text toward contemplating a design. Hughes thus proves himself to be thoroughly in control of the modernist typosphere from which he draws, in large part, his poetic force. Still, as Hughes’s irony reinforces, the claim to mastery—“I too am a cubist!”—can turn out to be a case of colonial mimicry rather than postcolonial critique. Demonstrating one’s ability to manipulate type might turn out to be just another way of catching the “disease,” or “selling out” (“Solde”).

THE ASSIMILATION OF NEGATION AS THE POWER TO NEGATE

This cycle of self-affirmation (“I can do what the ‘boss’ does”) and self-implication (“What does that mean that I can do what the ‘boss’ does?”)—or resistance and complicity—is frequently the subtext of Damas’s poetry as well. But in at least one sense, Damas manages to go a step further than Hughes does in “Cubes.” Damas removes himself from the conflict between “boss and bossed” and “black and white” in order to suggest that prowess with typography—or musicality, for that matter—need not be associated with either one or the other. Perhaps for Hughes the disease of modernity is contagious, and therefore typographic experimentation risks becoming merely another way of showing that he, too, has caught the bug. (He has become “blanchi”—“whitened,” as Damas would say.) But for Damas, typographic experimentation can be a powerful weapon, not necessarily a form of colonial mimicry or even a reflection of colloquial speech but rather a means to express the negativity that breaks apart all words, undermines all essences, and weakens all oppositions—including the aural versus the visual, or the black versus the white.

Let us observe again how the fragmentation practiced in “Cubes” differs from its parallel in “Réalité.” Immediately, we see that Damas is careful to avoid the association of poetry with an entirely visual exercise. In the closing lines of “Réalité,” for instance, the word remains, although splintered, capable of being pronounced. As opposed to “d-i-s-e-a-s-e,” the separate letters of which, once pronounced separately, no longer render meaning, “Ré-a-li-té” can be vocalized; it can still produce a recognizable word. However, this word has been blasted, reduced to an assemblage of syllables linked by an eye that must “read” the space of the page in a different way. The systematic rupture of the syllables after the vowel is respectful of the way in which the word would be pronounced (or rendered in a dictionary); yet the fragmenting and “staircasing” of the word manifests a desire to hammer at, even to violate, the word. Damas marries a hyperrespectful approach to textual conventions with a clearly legible destructive intention that is typical of his work as a whole. Such negativity surges up in his poetry in many forms: it is lodged in his sarcasm, palpable in images such as “couper leur sexe aux nègres / pour en faire des bougies pour leurs églises” (cut off the negros’ genitals / to make candles for their churches) (“S.O.S.”); or “les mains effroyablement rouges / du sang de leur ci-vi-li-sa-tion” (hands frighteningly red from the blood of their ci-vi-li-sa-tion) (“Solde”). We hear it in the insistent repetition of words or phrases, such as “Bientôt” (Soon) in the poem of the same name, or “Moi je leur demande” (I ask them) in “Et caetera.” Finally, Damasian negativity resurfaces in the form of a fragmented, constantly interrupted utterance. Damasian negativity is a “stutter” (bégaiement), or “hiccup” (hoquet), a visceral rupture in the skin of the morpheme and the flow of the breath. In “Réalité,” as elsewhere, the typographic placement of the letters inspires us to vocalize them, but the exaggerated correctness of this vocalization—“Ré-a-li-té”—transforms the word into a parody of itself. Thus, interruption and fragmentation of the printed word render speech print-like: to vocalize the text we must pronounce the syllables separately, as though reading a spelling manual (or doing a dictée). But such interruption and fragmentation also render print speech-like: to make sense of the text we must link the fragments together through their sequential articulation and thus rely on the continuity provided by vocalization in time.

“Hoquet” is a poem that thematizes this experience of rupture while reproducing rupture on the surface of the page in such as way as to produce a series of rhythmic effects singular to scripted sound. (Please see the appendix 1 for an English translation.)

HOQUET

Et j’ai beau avaler sept gorgées d’eau

trois à quatre fois par vingt-quatre heures

me revient mon enfance

dans un hoquet secouant

mon instinct

tel le flic le voyou

Désastre

parlez-moi du désastre

parlez-m’en

Ma mère voulant d’un fils très bonnes manières à table

Les mains sur la table

le pain ne se coupe pas

le pain se rompt

le pain ne se gaspille pas

le pain de Dieu

le pain de la sueur du front de votre Père

le pain du pain

Un os se mange avec mesure et discrétion

un estomac doit être sociable

et tout estomac sociable

se passe de rots

une fourchette n’est pas un cure-dents

défense de se moucher

au su

au vu de tout le monde

un nez bien élevé

ne balaye pas l’assiette

Et puis et puis

et puis au nom du Père

du Fils

du Saint-Esprit

à la fin de chaque repas

Et puis et puis

et puis désastre

parlez-moi du désastre

parlez-m’en

Ma mère voulant d’un fils mémorandum

Si votre leçon d’histoire n’est pas sue

vous n’irez pas à la messe

dimanche

avec vos effets des dimanches

Cet enfant sera la honte de notre nom

cet enfant sera notre nom de Dieu

Taisez-vous

Vous ai-je ou non dit qu’il vous fallait parler français

le français de France

le français du français

le français français

Désastre

parlez-moi du désastre

parlez-m’en

Ma mère voulant d’un fils

fils de sa mère

Vous n’avez pas salué la voisine

encore vos chaussures de sales

et que je vous y reprenne dans la rue

sur l’herbe ou la Savane

à l’ombre du Monument aux Morts

à jouer

à vous ébattre avec Untel

avec Untel qui n’a pas reçu le baptême

Désastre

parlez-moi du désastre

parlez-m’en

Ma Mère voulant d’un fils très do

très ré

très mi

très fa

très so

très la

très si

très do

ré-mi-fa

sol-la-si

do

Il m’est revenu que vous n’étiez encore pas

à votre leçon de vi-o-lon

Un banjo

vous dîtes un banjo

comment dîtes-vous

un banjo

vous dîtes bien

un banjo

Non monsieur

vous saurez qu’on ne souffre chez nous

ni ban

ni jo

ni gui

ni tare

les mûlatres ne font pas ça

laissez donc ça aux nègres

On a first reading, many readers are tempted to associate the eponymous hiccup (“hoquet”) with something natural, like the burp (“rot”) that surges up from an a-social stomach (“et tout estomac sociable / se passe de rots”). In this case, the hiccup would bring with it “childhood” (“revient mon enfance”), the word “enfance” presumably evoking an innocence and originary authenticity that has been lost. It is conventional, even banal, to speak of the lost innocence of childhood returning suddenly in memory to the jaded adult, but this is not what Damas is saying at all. The initial grammatical parallelism (“tel que”) actually links “mon enfance” to “flic” (“cop”) and “instinct” to “voyou” (“rascal”). Thus, what returns like a “hiccup”—a convulsive, involuntary eruption—is an “enfance” that has nothing natural or instinctual about it, a childhood characterized by the suppression of the physical body (the “rots”), the memorization of somebody else’s history, and the playing of a “vi-o-lon.” Considered more closely, the “hiccup” appears to exert a negative power on the subject’s ability to utter speech and therefore to vocalize desire. It is a rapid inhalation that cuts speech, an in-pression rather than ex-pression, shaking up the subject (“secouer”), just as a mother might shake the shoulders of an impulsive child.

We should note further that it is not the child (“enfant”) who returns with the hiccup but rather the childhood (“enfance”), the greatest period of apprenticeship during which the subject learns to adopt the “ci-vi-li-sa-tion” of the colonizer—here, through the conduit of the anxious mother. Because, as Richard Burton has remarked, the “enfance” in question is not only childhood but a childhood of “a peculiarly structured and overdetermined kind,” the author encourages us to associate “enfance” with an experience of limitation, not plenitude, of stifling, not self-discovery.35 As a result, what returns in visceral fashion does not itself belong to the order of an instinct or a positive impulse; rather, what returns is the only thing that can return, the “no” of the repressive mother, anxious for the full integration of her child into a society of culturally elite métissés. To be sure, the hiccup belongs to the order of the body, but it is not by the same token emancipatory; it is the visceral, the corporeal turned against itself. Like a reflex, a function of involuntary memory, the hiccup prevents the subject from ever definitively leaving childhood behind; thus, the return of the repressed is the return of repression itself. Even when invited to step onto the stage and assume speech, the subject fails to “parler du désastre” (speak of the disaster) without stuttering, an effect captured in the lines “Et puis et puis / et puis désastre.” The repeated “puis” indicates that such speech is not about the disaster but is a symptom of disaster itself. The injunctions suffered in childhood return in the form of a hiccup that the adult cannot erase no matter how hard he tries (“J’ai beau avaler sept gorgées d’eau …”). The injunctions impose a kind of gag on the adult as well as on the child he once was, practicing on the hapless body of the assimilé an internalized form of an oppression imposed initially from without.

This experience of constant negation, of a gag placed on emission, is represented in several ways in the poem. First of all, the repetitive interpellations of the mother create a pattern—the columns of syntactical parallelisms—that proves to be contagious, affecting the way the child performs as well. Thus, the solfège exercises presumably practiced by the child are not occasions for melody but instead enforce a form of delivery that is less like the chant of anaphora than the stuttering of a broken record. Impersonal directives such as “Le pain ne se coupe pas / le pain ne se gaspille pas / le pain de Dieu” eventually resolve into rhythmic nonsense—“le pain du pain”—as a result of the reiteration of syntagmatic units. The repetitive nature of the mother’s instructions ends up transforming all utterance into mechanical repetition: the prayer—“et puis au nom du Père / du Fils / du Saint-Esprit”; the lesson—“très ré / très mi / très do”; and even memory’s account, the substance of his personal experience, or black Leib—“et puis et puis / et puis. …” In short, the poem recounts an “enfance” that is nothing but one long stream of repeated injunctions, a sequence of “Taisez-vous”s (Be quiet) spoken in the “vous” form that annihilates the subject through excessive politesse. Reduced to a kind of miming monkey, the child can no longer utter much more than rupture itself. This rupture is at the same time an effect and a cause; it is the symptom of a repressive childhood transformed by the poet into a technique productive of visual and sonic patterns. Following the logic of détournement, Damas shows here that by assimilating the negativity of a repressive regime he also assimilates the power to negate. And this power to negate turns out to have its own critical force when manipulated as a poetic device.

“Hoquet” is a kind of poetic drama in which three voices—that of the mother, the “je,” and perhaps the child—take turns holding the stage. The mise en page of the poem underscores the division of voices: the words of the mother (mouth-piece for the colonial system) are indented and placed in a column slightly to the right while the words of the speaker (the “je”) are properly lineated on the left. The source of the repeated refrain, “Désastre / parlez-moi du désastre / parlez-m’en,” is unclear; these words seem to constitute an interpellation from without, another form of verbal force obliging the child to recount his disastrous childhood. One might argue that the source of the interpellation is the “monsieur” to whom the child—or the mother—responds “non” in the penultimate stanza. Or they could be the call of the adult (the “je” of the beginning) who hopes to make the silenced child deep within him speak. In any case, the refrain punctuates the poem in a regular fashion, encouraging the “je” to tell the story from the point of view of its victim (the child)—that is, to recount a childhood given over to the process of assimilation.

“Assimilation” means, literally, to take in from the outside; the “hiccup” is thus a perfect symbol for assimilation since it cancels speech through the swift, convulsive intake of air. But there is in the poem at least one sign of ex-pression, a sign of an intervention into the mother’s world that is so disturbing it causes her to respond. “Il m’est revenu,” recalls the speaker, addressing the “vous” (presumably the object of all the injunctions), “que vous n’étiez encore pas / à votre leçon de vi-o-lon / Un banjo.” This “banjo” appears to have the privilege of temporal priority with respect to the violin lesson.36 Its eruption into the scene of instruction suggests an alternative lesson that could be learned, an alternative “voice” that could be heard (that could “return”: “il m’est revenu”). But “no,” the mother interjects quickly: “vous dîtes un banjo / comment dîtes-vous / un banjo / vous dîtes bien / un banjo/ Non monsieur. …” Her consternation mingles with astonishment as she begins to repeat her own refusal. However, in repeating herself she inadvertently allows the forbidden word to be pronounced four times in rapid succession, submitting thereby her own words to the hiccupping rhythm, the poetic device, derived mimetically from the force of her injunctions. In a wonderful reversal perhaps available only to written poetry, the text assimilates the mother’s logic—the logic of the taboo—and exerts its force on the forbidden words, “banjo” and “guitare,” to produce an innovative sequence: “ni ban / ni jo / ni gui / ni tare.” In the final passage, the forbidden words are fragmented in space, mutilated by the denial, or “ni,” of the mother, thus producing a propulsive rhythm even as the verbal unit is scattered in space. If the child finds himself unable to speak, unable to answer the repeated call to “parlez du désastre,” the blame lies with the mother—or more precisely, with the colonial system that encourages her to despise her son. The mother wants a son “très” correct, capable of reciting his solfège not for the purpose of making music or of singing but so he can perform his perfect assimilation, his mime of what he has been taught to be. Ironically, however, her quest for perfection, for an exaggerated domestication of his instinctive self, results in nothing more than the mechanical recitation of a list. He can only mutter a scale that is constantly interrupted by the traumatic force of his mother’s desire (“très ré / très mi / très do”).

What, then, could possibly emerge from the mouth of this thoroughly assimilated, indoctrinated child if not the impulse of denial, the “ni … ni” (“neither … nor”) signifying the double bind of a thoroughly interiorized negativity? What instrument could this child possibly play other than a “vi-o-lon”? The cavity of that violin is rendered almost visible by the typographic characters, the spacing of which evokes the great zero (“-o-”) in the middle of the violin, or the hole installed at the heart of this violated “voyou.” If the child finally does manage to make some noise, it is due to the hiccup itself, the “hoquet”—the empty “o” added to a “k” (“o-kay”) that paradoxically works as a negation. The eruptive hiccup allows him to interrupt the course of what can be said, what can be done. It sustains the power of the “flic,” mobilizing the force of self-denial and repression to forge a writing style. The “hoquet” becomes the vehicle of an aesthetic subjectivity, marking the spaces where the “lyric I” would be. The spasmodic interruption shapes the poem’s rhythmic patterns, patterns made both of tones (“ré-mi-fa” or “sol-la-si”) and of the silent spaces in which the reader takes (or holds) her breath.

A question the poem seems to raise is whether the child ever manages to express his own rather than his mother’s desire. Does the poet—the “monsieur”?—find a way to make this child speak? (“Parlez-moi du désastre.”) Another way to ask this question would be: Does the affective experience of a repressive upbringing manage to find expression on the page? Perhaps what the poem illustrates most successfully is the way the disaster of assimilation can be mobilized to organize language—here, into staccato patterns of words constantly ruptured and reruptured as the gag on self-expression is tightened. The hiccup of repression, that gap in speech created by a sudden intake of air, creates a stutter-like rhythm of locution that becomes itself a kind of style, a “stylistique du bégaiement,” in Jean-Pierre Bobillot’s felicitous phrase.37 Theorists have written in general terms about stuttering (or “bégaiement”) as a style—or, rather, as style itself. We might consider, for instance, Gilles Deleuze’s treatment of the stutter as “éminément poétique” in “Bégaya-t-il …,” an essay in which he treats the poetry of Gherasim Luca as though it derived from a strategy similar to that at work in “Hoquet”: “Every word divides, but divides with itself (pas-rats, passions-rations); every word combines, but with itself (pas-passe-passion).”38 Luca’s formula, “je t’aime passionément” (I love you passionately), “bursts out [éclate] like a cry,” writes Deleuze, “after a long series of stutters”:39 “je t’ai je t’aime te / je je jet je t’ai jetez …” we finally arrive at “je t’aime” (I love you).40

One could see the word “nègres” printed in bold in the very last line of “Hoquet” as a similar moment in which the repressed term of the series is finally blurted out. After all, the one thing one must never say, think, or be, is black. For Deleuze, the stutter mechanism, the parsing and parcelling of phonetic packets, constitutes style in general. “Le style,” he writes, is “la langue étrangère dans la langue” (style is the foreign language in the language).41 Similarly, Bobillot understands the “stylistique du bégaiement” to consist in an “effort to find spaces within language where it might be possible to stage a return of the repressed.”42 Both find that a kind of “jouissance” of language is generated not despite but because of repression. The negativity of a law (the “Symbolic”) that makes us speak correctly (or hypercorrectly), a law that insists we separate words from noise, ends up producing more noise than words. Out of this noise, the poet creates a verbal universe of fragments that can be organized into new sequences, new patterns, other than those required by conventional syntactical or lexical laws. In other words, not being able to speak produces a verbal style, a qualitatively different sound pattern, and thus a different way of taking up (graphic) space.

UNE MÉDIOSPHÈRE MÉTISSÉE

It is important to signal that both Deleuze and Bobillot consider “le stylistique du bégaiement” to be either a general phenomenon of writing or, alternatively, a phenomenon specific to “grands écrivains” such as Henri Michaux. Further, they both see the stuttering style as an attack not on a particular language (e.g., French) but on the Symbolic, or language in general.43 In contrast, Fred Moten, writing on the stylistics of African American poetry, has cautioned against equating the resistent practices of African-derived writers with those of writers in general (or experimental writers in particular). He writes astutely that “the tragic in any tradition, especially the black radical tradition, is never wholly abstract.”44 In other words, the attack is not against “the Symbolic” as such but rather is “always in relation to quite particular and material loss.”45 Moten’s reminder is crucial, for the problematic Damas confronts in “Hoquet” is specific to the psychic life of the populations named “mûlatres” and “nègres” in the poem. Further, the injunctions voiced by the mother are not exemplary of the “law” of Language, but metonymies for an entire colonial regime. Finally, the subaltern is not just any disenfranchised writer, repressed child, or high modernist practitioner of the “sémiotique” but rather a raced subject struggling with a very concrete set of prohibitions indeed.

Still, the poetic expression of this specificity is not entirely unique to Damas or to black writers as a group. As members of the typosphere, Damas and the Negritude poets draw from a shared set of typographic, alphabetic, and graphemic possibilities for evoking repression on the page. Graphemic–phonemic relations constitute a field of acoustic exploration available to all poets invested in bringing the visceral experience of negative injunctions to the reader’s eyes. It may be, as Édouard Glissant has proposed, that the peoples of the Caribbean possess a heightened sensitivity to sound due to the circumstances of their enslavement.46 For them, sound—not as immediacy but as opacity—bears an almost graphemic heft. But is this not the case for many poets? Of many nationalities, ethnicities, and political orientations? Again, the inflection matters here; the cultural associations with which sound is freighted inform what sound can come to mean. There are historical reasons for the particular attention black cultures have paid to oral and musical forms, and these should be taken into account. Yet it is unlikely that one culture alone has a privileged relation to what Glissant calls the “noise in speech.”47 In his reading of “Hoquet,” Richard Burton (echoing a generation of scholars) posits a binary opposition between the “instinctive, lyrical and improvisatory energies expressed in the Afro-creole banjo” and the “hierarchical rigidities and repetitions of the Gregorian scale.”48 Certainly there is a difference between a spontaneous effort and the solfège exercises the child is compelled to recite. But when Burton contrasts “the joyously rebellious rhythms and accents of the colonized” with the “regularized crochets, minims and quavers … fixed for all time within the staves, bar-lines and time-signatures of the colonizer” (25) he comes dangerously close to identifying “instinctual” and “joyous” musicality with blacks and the regime of writing (“time-signatures of the colonizer”) with whites. Is the acoustic universe so neatly divided?

Brent Hayes Edwards has recently published impressive studies of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong as writers that place into question what he calls the “compulsion among generations of African American writers”—and, one might add, critics—to associate “black writing” with “the condition of music.”49 By pointing out this “compulsion,” Edwards does not mean to “undermine the importance of black music,” nor does he wish to deny that black expression pays a heightened attention to sound. But he nonetheless encourages us “to begin to challenge some of our assumptions about the relations among aesthetic media in black culture.”50 To give just one example of how such assumptions might be challenged, Edwards demonstrates that Ellington saw print as a medium that could itself produce rhythm, a medium that could be scored such that words on a page might suggest a phrase or riff. Similarly, I have maintained that Damas by no means abandons the text for either music or noise, nor does he seek a mastery over sounds instead of words. The stuttering sounds of “Hoquet” do not trail off into sonic nonsense but instead produce with ringing clarity (and usher into the lyric tradition) the words “nègres” and “mûlatres,” and, elsewhere, “Juif,” and “Jaune.” In a sense, then, Damas’s “stylistique du bégaiement” presents a way out of the trap of colonial mimicry that Hughes points to in “Cubes.” For Damas the danger lies not implicating oneself in the master’s practice by imitating too closely his techniques; the trap lies instead in assuming those techniques to be owned by one “race” alone. Embracing print as a support, Damas uses the means of print—words, but also spaces, marks of punctuation, and the resources of the written alphabet—to carve out a site of personal expression, something like “le creux d’une épaule” he sought in “Réalité.” He manages to convey an experience of alienation that is caused not by the loss of some originary orality but rather by almost complete submission to authority in exaggerated form.

Among all the critics who have glossed “Hoquet”—and there are many—it is perhaps Aimé Césaire who best grasped the import of the poem. In an homage to Damas written soon after his death, Césaire suggests that the Damasian hiccup (“le hoquet damassien”) is a version of the Sartian “Nausée”: “As there is the Sartian Nausea,” he writes, “there is fundamentally the Damasian hiccup, which is disgust, repulsion, attempts never completely fulfilled. … [There is] the Damasian stutter [“le bégaiement damassien”] … a weakness transformed into strength because it is responsible, ultimately, for creating the Damasian rhythm.”51 As I have argued, the poems of Damas do indeed have rhythm, but it is his rhythm, as Césaire states, not the rhythm of Africa resurrected, as Senghor would have us believe. “Hoquet” contains many rhythmic sequences that could easily have been based on, or could produce, a musical recitation, a drum-like beat. Damas was always conscious that he had succeeded in this way. According to witnesses, Damas loved to recite “Hoquet” before his friends; the poem became a sort of poetic signature, a little performance piece that he gave at the conclusion of dinner parties. One could even argue that performance is precisely the theme of “Hoquet”—musical performance as a kind of symbolic capital—not simply a case of colonial mimicry but also, potentially, a source of cultural pride. The poem contains multiple evocations of musical instruments: the violin, the banjo, the guitar, and—implicitly—the drumbeat of syntactical units in apposition, seductive rhythms that are hard to resist. Yet “Hoquet” is also the poem in which Damas refines and systematizes a set of typographical innovations unknown to previous poets of the diaspora: the use of the dash and letters in bold, the placement of phrases, words, and word fragments in vertical columns, and the exploitation of the iconic values of printed characters (as in “vi-o-lon”).

Ultimately, Damas does not wish to choose between a sound poetics coded as black and a typosphere coded as white. His best work makes rhythms by shuttling between the graphic entity of the page and the vocalized beating of the syllable. And his most memorable performances are those in which words admit their inability to “Speak of the disaster”—that is, to make repression go away. “Hoquet” deserves its renown—and exerts its influence—not because Damas knew how to imitate the beating of a tom-tom, the strumming of a banjo, or even the tonality of the human voice. The achievement of Damas is to have written a poem, and this poem is neither African nor French, neither black nor white, neither tom-tom nor orchestra but rather a singular phenomenon in print lending itself to actualization on many planes in all the plenitude of a mediosphere métissée.

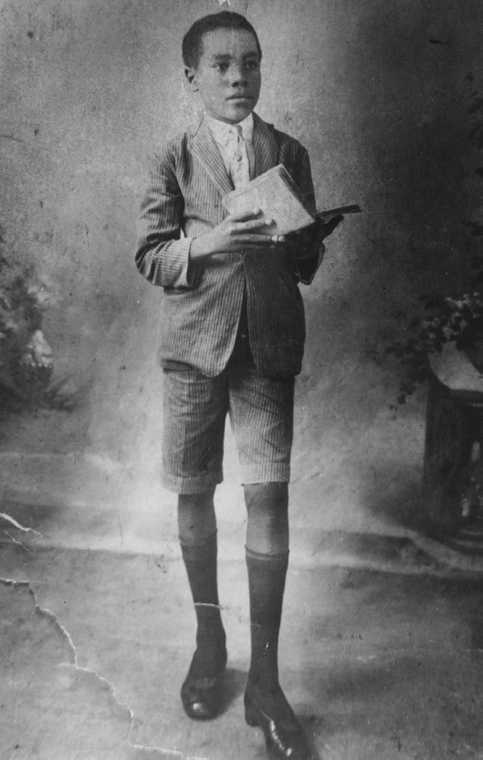

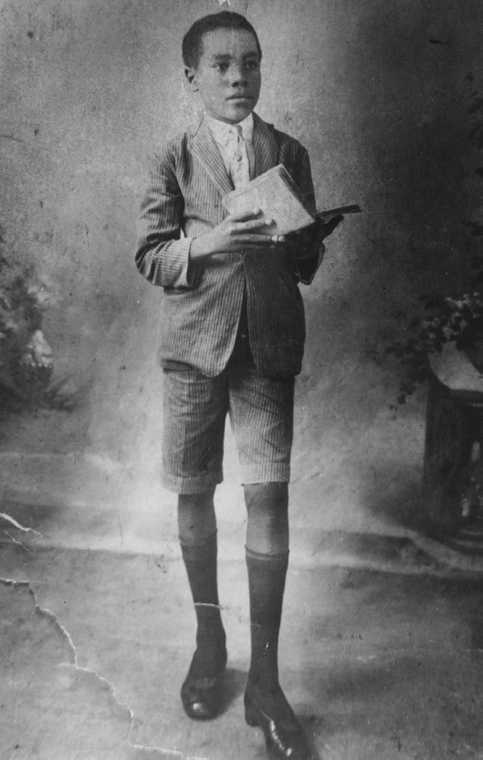

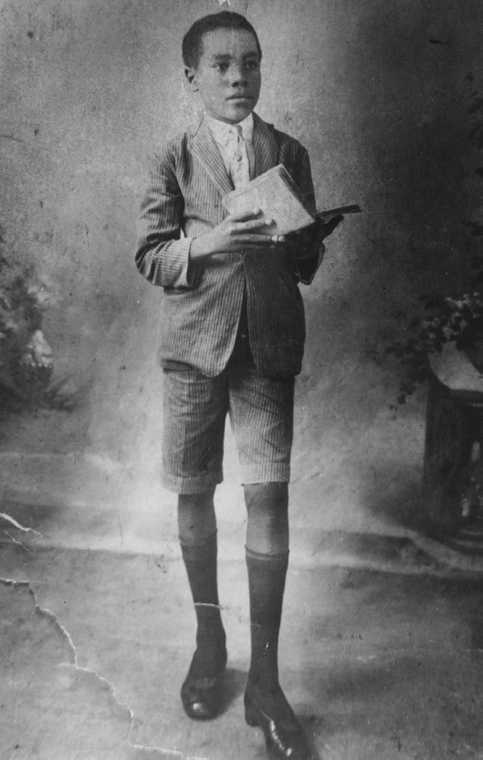

Figure 3.1: Portrait of Léon-Gontran Damas as a youth, about age nine, holding a book, circa 1921. Photographer unknown. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.