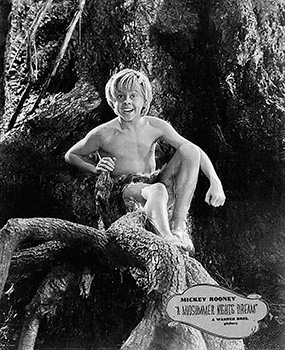

Mickey as Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1935.

POSTER COURTESY OF THE MONTE KLAUS COLLECTION.

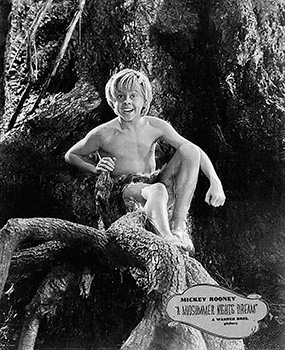

Mickey as Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1935.

POSTER COURTESY OF THE MONTE KLAUS COLLECTION.

Before Mickey signed his new contract at MGM, he was effectively a free agent and had started to draw attention with Manhattan Melodrama and Hide-Out. While his mother anxiously waited for Harry Weber to finalize the agreement with Mayer, Mick spent his summer playing tennis and enjoying the respite from work. Nell had rented them a recently constructed Spanish-style house designed by architect Vincent Treanor in 1929, in the neighborhood of Carthay Circle. Finally, they were in their own home and out of the many cramped rooming houses they’d been forced to live in. The four years Mickey Rooney would spend in that house on Schumacher Drive would be among the most important of his career.1

The ambitious Nell, who religiously scoured the Hollywood trade papers every morning, one day read with interest of the open casting call for the great Max Reinhardt’s production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Hollywood Bowl. While the stage was daunting to many film actors, Mickey at fourteen was a seasoned pro. As for this production, the trades were rampant with rumors of noted actors who were interested in snagging a role. While Nell had no knowledge of anything connected to Shakespeare, friends told her that Mickey would be perfect for the role of the sprite Robin Goodfellow, otherwise known as Puck. She also read that “America’s Sweetheart” forty-one-year-old Mary Pickford had shown some interest in the role, as had eighteen-year-old Olivia de Havilland. But any opportunity to join that cast would depend upon the decision of famed director Max Reinhardt.

Max Reinhardt was an Austrian-born Jew who lived in both Berlin and Salzburg, Austria, and had a worldwide reputation as the founder of the prestigious Salzburg Festival, where he became legendary as the director of stage spectacles such as Faust, Oedipus Rex, The Miracle, and, in 1927, a highly acclaimed production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which he later brought to Broadway. Reinhardt was presciently correct in fearing Hitler’s eventual Anschluss of Austria in 1938, and had sought permanent asylum in the United States in the summer of 1934. He quickly accepted an invitation by the Southern California Chamber of Commerce to produce and direct a revival of his 1927 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Hollywood Bowl. The costly $125,000 extravaganza would be underwritten by the mostly “Jewish moguls,” as the Los Angeles Times referred to them, at the major studios, according to author David Wallace. Times publisher Harry Chandler cajoled them to “unzip their pocketbooks” and bring some culture to Southern California.2

For Reinhardt, this was an important opportunity. He was known as a great stage director and an impresario, but he had met only reluctance in his attempt to become a film director, with studio bosses not convinced he could make the crossover from stage to screen. Reinhardt felt that if he could produce a great success—and he was confident that he would—with Midsummer, one of the studios might give him the chance to direct films.

Reinhardt sent his son, future film director and producer Gottfried Reinhardt, to make advance arrangements for the play. Gottfried recalled that his father sent a telegram to him in Los Angeles to secure a cast of “All-Stars,” one that included Charlie Chaplin for Bottom, Greta Garbo for Titania, Clark Gable for Demetrius, Gary Cooper for Lysander, John Barrymore for Oberon, W. C. Fields for Thisbe, Wallace Beery for Lion, Walter Houston for Theseus, Joan Crawford for Hermia, Myrna Loy for Helena, and Fred Astaire for Puck.3

Though Reinhardt was clearly ambitious, he was self-deluded in dealing with these mega stars. Certainly none of these box office actors would be interested in working for a tenth of their salaries, and had nothing to gain from being involved in the difficult production, Shakespeare or not. So Gottfried placed announcements in the Hollywood trade papers and contacted the talent agencies and casting offices to let the industry know that he was holding open auditions for all the parts in the play.

Harrison Carroll of the Los Angeles Evening Herald Express wrote on June 14, 1934, that “actors and actresses have dropped their tennis rackets, picked up their Shakespeare anthologies and started practicing their elocution.”

With Mickey at his leisure for the summer, Nell asked Harry Weber to ask MGM if he could try out for the part. Although the contract was not signed yet, it was nearly formalized, and she did not want to rock the boat if the studio had plans for Mickey. Mayer recognized the importance the experience would have for Rooney, and for MGM if the play was successful, and allowed him to try out for the role. Fortune, again, smiled. This time through Louie Mayer.

In late June of 1934, Mickey and Nell went to the suite at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel where Reinhardt was holding the auditions. The director’s associate, Felix Weissberger, held court as hundreds of noted performers auditioned for him. He was immediately smitten with Mickey’s looks. Physically, the young actor was exactly what he envisioned as the perfect Puck:4 his small stature, age (Mickey was a young teenager), and looks (he had an impish, in fact, puckish, face). The important test, of course, was whether Mickey could handle the Shakespearean dialogue, not the street cant he spouted in Manhattan Melodrama. When Weissberger handed Mickey a script and asked him to read some stanzas of Puck’s dialogue, Mickey furrowed his forehead, took a deep breath, and stumbled through Puck’s opening lines as best he could.

How now, spirit, whither wander you? . . .

The King doth keep his revels here tonight5

As Mickey recalled, “Weissberger said, in his heavily accented English, ‘Not bad, not bad. Now I vant you should go home and memorize all zis und come beck for anozzer audition. Verstehen sie?’ He then handed me a script with my lines marked in red.”6

This was indeed a challenge for a young actor trained in vaudeville and burlesque. However, that experience may have held a key to his tremendous skill as an actor. Dr. Kevin Hagopian, a film historian and professor of film at Penn State University, offers an interesting perspective on Rooney’s training: “I strongly believe that his early training in vaudeville and burlesque gave him the tenacity to undertake roles like Puck. In burlesque, you undertook any part you were given. If the producer asked if you could play the trumpet, whether you could actually play or not, you answered in the affirmative. Then you went out and learned how. You performed before crowds that had no tolerance. You either succeeded or flopped on stage. There was no in between. It was a rough and tumble world and you learned to adapt. It taught great versatility. It was an amazing training ground. It was why I believe what the great film critic of the 1930s, Otis Ferguson, wrote in The New Republic, that ‘James Cagney and Mickey Rooney were among the finest actors of their generation.’ Both Cagney and Rooney were from burlesque and vaudeville.”7

Nell beamed with pride as her son passed the first test. However, Mickey was anxious, and had little of his usual confidence with this audition. He carped to Nell, “I can never learn these words and make them sound right!” Nell reassured him that all it took was familiarity with the lines. Mickey then started to memorize Puck’s speeches, with Nell feeding him his cues. Gradually he began to understand the character of Puck and get a feel for the rhythm of Shakespeare’s verse.8

At the second audition, Mickey was letter perfect. Although he did not understand all Shakespeare’s nuances, and he was still befuddled by the phrasing and archaic language, he just gave a reading of the lines as they were printed on the page. He imagined, with Nell’s encouragement, the merry impish spirit of Puck. Weissberger was astonished as Mickey embodied the character, from Puck’s mocking of the donkey’s braying to his maliciously playful child’s giggle. “Yah, goot!” Weissberger told Rooney, and then reminded him that he had one more hurdle. He had to get the approval of Herr Doctor Reinhardt.9

The day of the meeting with Reinhardt, Mickey and Nell waited nervously for the director’s arrival. Although they had been through countless auditions and cattle calls, this one was different. Hollywood was abuzz about Reinhardt’s production, and many performers felt that this could be the spotlight they needed to establish themselves firmly as accomplished actors. This was not for money or nationwide recognition; this was for prestige and honor.

A short time later, the imposing figure of Max Reinhardt strode majestically into the room at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, where he was holding the auditions. Reinhardt nodded curt greetings to Mickey and Nell, and then dropped into a chair. Reinhardt was a squarely built man with piercing black eyes, which he fixed on Mickey momentarily before, through Weissberger—Reinhardt spoke very little English—ordering Mickey to begin.10

One could easily have become intimidated by this powerful man at such an important audition. But Mick was ready. He had faced audiences in burlesque since he was a year and a half old. He knew his lines and understood the character. He now had Puck down pat, understood the childish playfulness of the role above and beyond any meaning it had for an Elizabethan audience. Puck was an ebullient prankster, and Mickey understood that. With the confidence of a veteran performer at the Old Vic, he rattled off the lines with remarkable ease. He even added a few facial expressions and comedic touches. Then he emitted Puck’s famous laugh-cum-cackle, which he had carefully worked on with Nell the previous night. Enchanted, the great and powerful Reinhardt cracked a rare smile and hired Rooney on the spot. “Forget Pickford and the others,” Reinhardt told Weissberger and his son, Gottfried, “Das Lache [that laugh] ich mag ihn gern [I like it].”11

Mickey and Nell were elated that he got the part of Puck, a potential watershed in his career. Even better, he was hired at three hundred dollars per week, double his MGM salary. Reinhardt filled out the rest of the cast with Walter Connolly as Bottom, and for Flute, Sterling Hayden (who would later become the voice of Pooh in Disney’s Winnie the Pooh). Reinhardt cast the trained Shakespearean actor Philip Arnold as Oberon, Evelyn Venable as Helena, and a teenage Olivia de Havilland as Hermia. Mendelssohn’s score was adapted by Erich Wolfgang Korngold; and Bronislava Nijinska choreographed the ballet, which featured dancer Nini Theilade. Rehearsals were set to begin in early September.

With the MGM contract signed, and with Mickey’s casting as Puck, Louis B. Mayer was finally impressed: “I think we have a raw diamond on our hands,” Mayer told Selznick, and agreed that his son-in-law had been right to push to get Rooney under contract.

After four weeks of rehearsal, the troupe was ready for the premiere. The Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News of September 5, 1934, carried the headline “Eddie Cantor to Preside at Big Reinhardt Feast.” The article gushed about Max Reinhardt and the production of Midsummer:

More than 250 men and women who have given most of their lives to the cultural development of Los Angeles and to entertaining the world from stage or screen or concert rostrum will pay tribute to Max Reinhardt, Viennese theatrical genius, at a dinner and reception at the Biltmore. Sponsors of the Reinhardt presentations of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” at the Hollywood Bowl commencing September 17 as hosts of this evening’s dinner at which Rupert Hughes will act as toastmaster and at which Eddie Cantor will serve as Master of Ceremonies introducing such entertainers as Rubinoff, celebrated radio maestro; Ethel Merman, Broadway musical star; Hazel Hayes, concert and film singing star; Mickey Rooney, who plays Puck in the Reinhardt-Bowl presentations; and other celebrities.12

Early praise for the production was giving Mickey a certain acclaim he had never experienced before. The legendary gossip columnist Louella Parsons, in the Los Angeles Examiner, proclaimed on September 8, 1934:

Mickey Rooney, the freckle-faced thirteen-year-old youngster, is the very “Puck” that Max Reinhardt has been looking for all of these years. “He has that elfin quality, that mischievous impishness,” said Reinhardt, “that is so difficult to find, and he is the best Puck I have ever had.”

I sat in at the rehearsal of “Midsummer Night’s Dream” and heard Mickey read lines that astounded me. It took a Reinhardt to discover this little boy’s talents. “Mickey,” said Reinhardt, “is fantastic.” And now what about our film producers? Are they going to let Max Reinhardt return to Salzburg without producing a Shakespeare play?

Before the play ever premiered, the Los Angeles papers covered almost every rehearsal as if it were an event in itself. W. E. Oliver in the September 13, 1934, Los Angeles Evening Herald Express wrote the front-page story “Stars Frolic in Bowl Under Reinhardt’s Eye.” In a story about the “production of the biggest outdoor Shakespeare effort on record,” Oliver extolled Reinhardt’s “genius” and explained how he was “modifying the spirit of ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ to catch the spirit of the California setting.” The article focused on Mickey as Puck “screeching in practice under the scaffolding.”

On September 17, 1934, the big night—and a beautiful evening at that—finally arrived at the Hollywood Bowl. Mickey remembered, “The play went off without a hitch, not even a hitch in my jockstrap. In fact, it seemed over almost before we knew it had begun. All of a sudden, I was into my closing lines.”

Give me your hands, if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.13

Mickey recalled, “I raced up the long, flowered ramp to what I remember as thundering applause, a roar that I thought everyone in Los Angeles could hear. My gosh, I said to myself, they’re cheering for me.”14

The play was a complete triumph. Critics from coast to coast raved about it, making it a national sensation. Elizabeth Yeaman for the Hollywood Citizen-News wrote:

Long before the memory of man, Dame Nature fashioned the Hollywood Bowl, endowed with wooded beauty and astounding acoustic properties. Shakespeare, preceding the imaginative fantasy of Walt Disney by over 300 years wrote his immortal play of love, sprites and buffoonery and called it “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Max Reinhardt, German of colorful, dramatic spectacle, assumed the task of blending these two miracles—one man-made and one wrought by a higher-power. And last night the Weather Man conferred his blessing on the undertaking by providing a midsummer’s night of incredible perfection—a sky flecked with clouds that even a Reinhardt could not have produced and lighted by a moon suspended low against the Bowl horizon. And yet, even with the aid of Dame Nature, the Weather Man, Shakespeare and Max Reinhardt, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” would have lacked its wondrous fulfillment last night without the presence of Mickey Rooney, 13-year old Irish genius who was known, a year or so ago, as Mickey McGuire of short comedy fame. The achievement of Master Rooney in the role of Puck ranks second to none along with Shakespeare and Reinhardt.

Quite heady stuff, the kind of praise usually reserved for the crowning achievement of a career in the theater for the likes of an Olivier, Barrymore, or Gielgud. This was for a Rooney, who was only thirteen years old.

And the accolades kept on coming. On September 20, 1934, Louella Parsons, in the Los Angeles Examiner, wrote, “This suggestion comes from Edgar Allen Woolf and it sounds like a good idea. Edgar, who was one of the first to persuade MGM to put Mickey Rooney, the inspired Puck of the Reinhardt festival, under contract [everyone was now claiming credit for having discovered Rooney], sees the child as Peter Pan. Always a girl has played the part—Maud Adams and Betty Bronson—but Mickey could do it and be more like Barrie’s delightful character than anyone I know.”

Selznick must have appreciated this chorus of cheers for Rooney. Mayer was thrilled, too, not just because he had the hottest child star under contract, but because he had him under contract for only $150 per week.

After twenty-seven sold-out days at the Hollywood Bowl, a record at that time, Reinhardt took the show on the road, according to plan. There were two weeks at the University of California at Berkeley; then onto the nearby San Francisco opera house for four weeks, where the play was standing room only; and then to Chicago for four weeks at the Blackstone Theatre. Beyond the sudden acclaim and spotlight, Mickey and Nell were thrilled with the $300 a week for the play and their $150 stipend from MGM. This was a windfall for them.

Meanwhile, back in Hollywood, no studios were rushing to fulfill Reinhardt’s dream to direct. A Shakespeare film, hardly a commercial endeavor, was not alluring, especially in the midst of a depression. No doubt great prestige would be attached to such a film, but it would also create a large financial loss that most studios could not afford. The Laemmles at Universal were swimming in debt. Mayer and Thalberg rarely attempted “arty” projects. Zukor and Paramount considered the project, but were having an awful year financially. One studio was above water, though, and that was Jack and Harry Warner’s Warner Bros. It was doing quite well that year, with its gangster epics. And Jack Warner was interested in taking Midsummer on.

This was so for a few reasons, according to Kevin Hagopian, who, in recounting the history of the making of Midsummer, writes:

It was to be Warner Brothers’ entry into prestige film-making, a bid for the carriage trade by a studio whose trademarks were the staccato burp of the gangster tommy gun and the clatter of the newsman’s city room. But there was no denying the noisy hoi polloi that was Warner Brothers in 1935. What emerged from its sound stages was a Mulligan’s Stew of performance styles that showed off the vitality of American immigrant and ethnic culture at its most.

Jack Warner’s decision to take a flyer in high art would prove financially disastrous; the film lost heavily at the box office. But that’s not what “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” was all about. The Warner family had fled Krasnashiltz, then in Czarist Russia, in 1883, to escape the murderous anti-Semitism of the Cossack pogroms. Jack and three of his brothers had clawed their way to the top of the fledgling motion picture industry by the late 1920s, and now, Jack was eager to cement his new status as an American aristocrat. Warner had seen Max Reinhardt’s “epic theater” production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” at the Hollywood Bowl, and though he’d understood little of it and enjoyed even less, the appeal of Shakespeare to a boy from a shtetl family was irresistible. The colonnaded Greek-revival house in Beverly Hills, the exclusive private schools for his kids, the polo matches, the charity soirees, even the Ronald Colman mustache—“A Midsummer Night’s Dream” was to be the capstone in a campaign to signal high society that Jack Warner had arrived. This 1.5 million dollar production would seal Jack Warner’s miraculous transformation from the 12th son of a Russian Jewish refugee to English gentility, a make over possible only in Hollywood. Warner determined to make “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” tonier than anything his lot had ever produced.15

Indeed, Jack Warner heeded Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler’s call and unzipped his wallet to produce something of culture, the sound of flutes and the choreography of dancing sprites, to replace, at least for an hour and a half, the sound of submachine-gun fire and the ballet of bullets.

On October 7, 1934, about two weeks after the debut of the play, it was announced that Warner Bros. would produce the film version.

The casting of the film was of great speculation throughout Hollywood. Jack Warner wanted to include many of Warner’s contract players, to bring them prestige. He was insisting on their hottest star, James Cagney, and on dancing star Dick Powell. He also wanted to use an English actor with a Shakespearean background, Ian Hunter. Reinhardt had no problem with the fact that many of the actors Warner wanted to cast had no experience with Shakespeare; the director had faced this in past productions. However, he wanted to be the auteur of the film and make his imprint on it.

Throughout the process of preproduction and into filming, Reinhardt, whose huge artistic ego was on the line since this was his first major Hollywood film directorial venture, butted heads with Jack Warner, whose financial ego was on the line. They disagreed in several areas. Reinhardt kept escalating the cost of the film, which infuriated Warner, and Reinhardt was aggravated over Warner’s using William Dieterle as the lead director, because Reinhardt spoke very poor English. Another major argument took place when Mickey broke his leg. Warner wanted to replace Mickey with George Breakston, Mickey’s understudy, but Reinhardt loved Mickey and refused, saying he would shoot around him while the actor’s leg healed.

Reinhardt’s son, film director Gottfried Reinhardt, claimed that Jack Warner “derived pleasure” from humiliating subordinates. “Harry Cohn was a sonofabitch,” he said, referring to the head of Columbia, “but he did it for business; he was not a sadist. [Louis B.] Mayer could be a monster, but he was not mean for the sake of meanness. Jack was.”16

Reinhardt thought Warner an illiterate, uncouth bully, but he needed to do this project to prove he could direct American films, and he was determined to do it his way. Elizabeth Yeaman of the Hollywood Citizen-News reported on October 30, 1934, about Reinhardt’s assembling a staff of his own choosing:

Speaking of technical experts, Warner appears to be making an effort to corner the market for their production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Max Reinhardt is supervising every aspect of the picture as they now have Erich Wolfgang Korngold, famous German composer to orchestrate the Mendelssohn music for the score; Bronislava Nijinskaia, sister of the famous dancer, Nijinsky, has been engaged to direct the dances; Anton Grot will design the sets; Max Rée will design the costumes; William Dieterle will direct; and Charles Kenyon and Mary McCall, Jr. are working on the screen adaptation of Shakespeare’s play! So far only Mickey Rooney is engaged for the role of Puck and is the only member of the cast definitely set.”

While the Rooneys assumed that MGM would easily loan Mickey out to Warner for Midsummer, Louis B. Mayer wanted to play some hardball. MGM producer/writer Sam Marx recalled, “Mayer knew he had Warner over a barrel . . . that little Mickey was the cornerstone to any success of that picture and that they needed him. Mick was getting next to nothing in salary, to boot. In the end, [Mayer] got ten times his salary and some great return cheap loan-outs [to MGM] for some Warner players.”17 This was one of the profit streams Mayer enjoyed by lending Mickey out for films he never would have made at MGM.

The drama of casting Mickey played out in the newspapers. On November 5, 1934, the Hollywood Citizen-News reported, “Despite rumors to the contrary, I have the assurance that Mickey Rooney will be definitely contracted for the role of Puck in the Warner production of ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ . . . although they suggested they could substitute young George Breakston in the role of Puck . . . however after seeing Rooney as Puck it would be a Herculean task for any other child to fill his shoes.” On November 7, the paper printed an update: “[T]here is some confusion over Mickey filling the role of Puck.” It was hard to keep up.

Mickey appeared sporadically in the traveling play (the first three performances in Chicago and for part of the run in San Francisco and Berkeley) because he was also being loaned out to the Fox Film Corporation to costar with Will Rogers in The County Chairman. His replacement in the play during this period was his understudy and threatened replacement in the film, George Breakston (who later played Breezy in the Andy Hardy films).

After much deliberation and bickering among the Warner brothers, the film version of Midsummer was budgeted at the then-astounding cost of $1.5 million. Oldest Warner brother, Harry unleashed his fury on his youngest brother, Jack, when he saw the budget, screaming, “Are you trying to destroy us for the name of prestige?”

Reinhardt was hired to direct, of course. However, director William Dieterle was brought in both to assist Reinhardt and to interpret for him in much the same way Weissberger had done in the stage production of the play. Under Reinhardt’s supervision, Dieterle would carefully oversee every detail. Mickey was the first actor to be cast, followed by Olivia de Havilland. They were the only two who made the transition from the stage version to the screen.

On November 27, 1934, the studio and Reinhardt announced the casting of the film. As Elizabeth Yeaman reported in the Hollywood Citizen-News:

Joe E. Brown will definitely play the role of “Flute” . . . [W]ith him will be Jimmy Cagney as “Bottom,” Dick Powell as “Lysander,” Jean Muir as “Helena” Donald Woods as “Oberon,” Ian Hunter as “Theseus,” Frank McHugh as “Snout,” Otis Harlan as “Starveling,” Grant Mitchell as “Egeus,” Anita Louise as “Titania,” Hobart Cavanaugh as “Philostrate,” Ross Alexander as “Demetrius,” Eugene Pallette as “Snug,” and Arthur Treacher as “Ninny Tomb.”18 Frank McHugh ended up playing Quince.

The cast was a mix of some Warner players who had Shakespearean backgrounds, such as English actors Ian Hunter and Hobart Cavanaugh, and great character actors such as Eugene Pallette and Frank McHugh. Included in the cast, but not mentioned in Yeaman’s column, were Olivia de Havilland and Mickey Rooney. Also on hand, based on Mickey’s suggestion, was Mickey’s friend from the McGuire shorts, Billy Barty, who would play the elfin Mustard Seed. There was some other interested casting with vaudeville comic Hugh Herbert, actor Victor Jory (who, instead of Donald Woods, ended up playing Oberon, and would go to play the evil overseer in Gone with the Wind), and celebrated dancer Nini Theilade.

Comic Joe E. Brown later remembered, “Some of us were certainly not Shakespearean actors. Besides myself from the circus and burlesque, there was Jimmy Cagney from the chorus and Mickey Rooney and Hugh Herbert from burlesque. At the beginning we went into a huddle and decided to follow the classic traditions in which Herbert and I were brought up. I really believe Shakespeare would have liked the way we handled his low comedy and I’m sure the Minsky brothers did. The Bard’s words have been spoken better but never bigger or louder.”19

Jimmy Cagney recalled that the actors often stood around on the sidelines whispering to one another and that Reinhardt didn’t realize that some of them didn’t understand the lines they were speaking. “Somebody ought to tell him,” Cagney said in the November 1935 issue of Screenplay magazine. The confusion [over the meaning of Shakespeare’s verse] didn’t bother Dick Powell, who said he never really understood his lines, anyway.”

Right before the start of principal photography, Mickey was reunited with his father, Joe Yule Sr.—a rare treat, as Mickey had had only intermittent contact with his dad over the previous ten years—and the two went to the Big Pines Resort in California, near Lake Tahoe. It was here where Mickey broke his femur while tobogganing. He later claimed, in Life Is Too Short, that he himself reset the break, or “yanked it back into position,” and that the medics later told him he would make a great doctor. They put his leg first in a splint and then later a hard cast.

There have been some discrepancies among reports over when Mickey had last seen his dad. In both his autobiographies, i.e., and Life Is Too Short, Mickey claims he did not see his father until after he had filmed Boys Town in 1938, a separation of about thirteen years. In both those books, Mickey claims to have gone to Big Bear with his mother even though newspapers said he had gone with his father to Tahoe.

Yet in an article by Elizabeth Yeaman in the Hollywood Citizen-News on January 15, 1935, she wrote, “It was a sad blow to Warner and the entire cast of ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ when young Mickey suffered while on a tobogganing expedition Sunday near Big Pines. Mickey’s father, Joe Yule Sr., ruefully admitted that there were 10,000 people on vacation at Big Pines Sunday and Mickey was the only one to be injured.” No matter who was with him, the tobogganing accident became a national news event and a disaster for Warner.

The Hollywood Citizen-News reported on January 15, 1935:

[A]ll the [Warner] executives went into a huddle yesterday to seek a solution to the great problem, since Mickey has already appeared in several scenes and the production is too expensive to be held over and wait until his leg permits him to run again . . . George Breakston is a brilliant little actor and had some fine notices for his work on the road as “Puck” and he knows the part just as well as Mickey Rooney. For the present, at least, Georgie will do the running and elfin sprints for the long shots in the picture. Warner may be able to use Mickey Rooney for the remaining close-ups.

Jack Warner was reportedly apoplectic. As Mickey wrote, “Jack Warner didn’t get angry. He went insane. The first thing he wanted to do was kill me. ‘Then after I kill him,’ he said, ‘I’m going to break his other leg.”20

Arthur Marx wrote in his Mickey Rooney biography, and told us in an interview, “There was a special clause in Mickey’s contract specifically forbidding him to engage in any contact sports.”21 This story (told by others as well) was untrue because Rooney, although he did have an agreement with Warner Bros. for this particular film, was under contract with MGM, not Warner Brothers.

IN THE END, WARNERS could not cut out the scenes already shot with Mickey. The studio had spent almost a quarter of the budget. As reported in the Hollywood Citizen-News, the studio revised the shooting schedule, shot the long shots with George Breakston as Puck, and waited for Mickey to return.

In the end, Mickey spent the next months recuperating in a hospital bed at Hollywood Presbyterian Hospital in a heavy cast. Eleanor Barnes, in the Hollywood Illustrated Daily News, wrote on February 9, 1935:

Mickey, gifted boy actor, left Hollywood Hospital yesterday after spending several weeks there with a broken left leg, suffered while tobogganing at Big Pine Lake. Although his leg is in a cast, Mickey insisted upon being taken to Warner Brothers’ Studio, where he reported to Max Reinhardt and said he was ready to resume work on “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Mickey was given a rousing reception by James Cagney, Joe E. Brown, Jean Muir, Veree Teasdale [sic], Anita Louise and other players in the cast, and all of them autographed his cast.

Despite all the hype, Reinhardt’s film adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream did rather poorly at the box office, as expected. The movie was a spectacle, to be sure, and it had a powerful cast, but the story itself didn’t resonate with theatergoers during the height of the Great Depression. Moreover, audiences seemed surprised, and perhaps disappointed, to see the likes of James Cagney running around in theatrical versions of Elizabethan costumes and mouthing sixteenth-century verse. The reviews were mixed. The film won only two Academy Awards, for Best Cinematography and Best Film Editing (and was nominated for Best Picture and Best Assistant Director). While the cinematography, use of Mendelssohn’s music, and dance sequences were highly praised, the acting received much criticism, especially Dick Powell’s. Early on, Powell, then a “Hollywood crooner,” had realized he was completely wrong for the role of Lysander and asked to be taken off the film, only to have Warner demand that he play the part.

Negative reviews notwithstanding, the film transported Mickey Rooney from the ranks of second-rate kid actors and into the forefront of child stars. He was talked about in every column, appeared on countless radio shows, and was now in demand for the choice roles at his home studio.

Did the film transform Jack Warner, as he had probably wished, from the “12th son of a Russian Jewish refugee to cultured English gentility”? Not at all. (However, it did vindicate Harry Warner’s outrage over the oversize budget.) Yet Jack Warner’s decision to open his wallet for what was surely going to be a money-losing proposition, and Max Reinhardt’s acquiescence to the demands of a studio production populated by song-and-dance men and a teenage ingénue, Olivia de Havilland, who barely understood their lines at first, became a great Hollywood moment. The film brought the breadth and egalitarian optimism of Shakespeare’s sylvan vision of a topsy-turvy society to an audience of everyday folk struggling to make a buck under the grinding weight of the Great Depression. And the magic of Mickey Rooney’s Puck was at its center as, laughing like a mischievous child, he spouted to an audience of modern-day groundlings, “Oh, Lord, what fools these mortals be.”