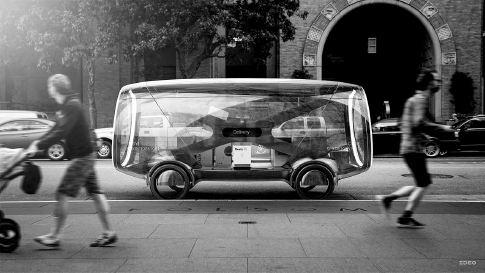

Figure 12.1 GM’s Electric Networked-Vehicle (EN-V) Concept pod, an autonomous two-seater codeveloped with Segway for short trips in cities.

Source: General Motors

Now that we’ve nearly reached the end of this book, we would like to bring up an issue that any in-depth exploration of driverless cars would be incomplete if it did not address: the topic of hype. In recent years, driverless cars have been the subject of a great deal of attention from the media. However, if there’s one lesson the long and colorful history of hands-free, feet-free driving should have taught us, it’s that even as people long for autonomous vehicles, desire is no guarantee that such a vehicle will actually appear.

Veterans of the tech industry may recall a two-wheeled go-cart called the Segway. In the year 2001, the Segway was launched with great fanfare. A few days before the launch, an article in Time magazine described the clouds of hype that accompanied the Segway’s secretive development process.1 According to the article, in a leaked book proposal about the technology, Steve Jobs predicted the Segway would be as “big as the PC” and legendary venture capitalist John Doerr pondered whether the Segway could be “maybe bigger than the Internet.” Turns out nearly everybody was wrong. Today, the Segway enjoys a quiet existence as a niche transportation solution, enabling warehouse workers and mail delivery personnel to roll short distances.

The swift rise and fall of emerging technologies such as the Segway raise an interesting question: why do some promising new technologies eventually disrupt entire industries, while others fail to live up to their hype? Like many others, we have pondered this question at length. Over the years, we’ve developed a useful little test we call the Zero Principle to assess the long-term potential of new technologies.

Here’s how the Zero Principle works. Emerging technologies that disrupt established industries share a common trait: their introduction dramatically reduces one or more production costs to nearly zero. In fact, once technologies that follow the Zero Principle have been in use for a few years, their effect on their industry is so disruptive that the eventual result is an industrial revolution.

Let’s look at some historical examples, beginning with the steam engine. If you were a technology observer in England during the late 1700s, would you have invested in the newly commercialized steam engine? If you had pondered this new contraption in the context of the Zero Principle, you would have immediately seen its potential.

The steam engine dramatically reduced the cost of keeping industrial machinery running. Before the invention of steam power, factories and mills were powered by sources that introduced either direct costs or indirect costs in the form of operating constraints. Factories fueled by running water had to be located in regions that boasted fast-running streams or waterfalls. Animal power was location-independent, but animals were not as powerful as the force of running water, plus they tired rapidly and had to be tended and fed.

When the commercial steam engine was introduced to industry, both the direct and indirect costs of powering industrial machinery nearly evaporated, transforming the manufacturing process and eventually bringing about an industrial revolution. Steam power made it cost-effective to produce steel, which triggered another cascade of downstream innovation. The availability of cheap, robust steel, in turn, gave birth to several downstream industries such as rail transportation and the construction of “ironclads,” naval vessels lined with steel to protect them against cannon fire.

Nearly two centuries later, another profoundly disruptive technology appeared: the computer. The computer, like the steam engine, was destined to shake up established industries since it reduced another once-formidable cost factor to nearly zero, the cost of numerical calculation. For most of human history, making mathematical calculations has been a slow, expensive, and (depending on the person) inaccurate process. Even the most highly trained expert humans armed with the best tools could make only a few hundred calculations per hour.

As computing technology matured in the 1950s, the cost of calculation began to drop precipitously. In the decades that followed, silicon chips replaced analog technologies, making computers faster and more reliable and affordable. Small businesses gained the capacity to carry out once-costly calculations quickly, accurately, and tirelessly. By the end of the twentieth century, cheap calculation enabled the emergence of a massive global market for productivity software and video games as regular people bought their own personal computer or gaming console.

History reveals that two very different technologies—the steam engine and the computer—shared an underlying trait in common. Their introduction to industry removed a once-major cost barrier, changing business practices in many different industry sectors and dramatically reshaping how people lived and worked. Today, driverless-car technology continues to develop by leaps and bounds. Only the passage of time will reveal whether we’re currently on the cusp of another period of sweeping social change, or whether we’ll eventually dismiss driverless cars as just another over-hyped emerging technology that failed to bear fruit.

Let’s apply the Zero Principle to driverless cars and examine the direct and indirect costs they reduce. One of the most significant monetary and social costs that driverless cars will reduce is that of harm from traffic-related accidents. Another cost that’s eradicated is the cost of time spent driving. For regular people, time spent driving is an indirect opportunity cost; for transportation companies, the cost of a human driver’s time is direct in the form of salary, a major cost component that defines how goods are moved from one place to another. Finally, since driverless cars remove accident-prone humans from the wheel, cars and delivery trucks will no longer need to be weighty and environmentally unfriendly, reducing the cost of fuel and enabling the introduction of a wide variety of vehicle body shapes and sizes.

Four core costs are reduced to nearly zero by autonomous vehicle technology.

Figure 12.1 GM’s Electric Networked-Vehicle (EN-V) Concept pod, an autonomous two-seater codeveloped with Segway for short trips in cities.

Source: General Motors

The direct and indirect costs of human-driven vehicles have defined business models for nearly a century. As driverless cars reduce or even remove these costs, the result will be that some businesses will no longer be viable. As some businesses close up shop and jobs disappear, new businesses and professions will emerge.

The first job likely to go will be that of driving a truck, a stable, well-paying blue-collar job that has been largely immune from the effects of offshoring and automation. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there are nearly 3.5 million truckers in the United States. In fact, driving a truck is the twenty-ninth most common job category in the nation. If driverless trucks become a viable way to transport merchandise from place to place, in a few short years automation may finally be coming to claim trucking jobs as well.

Figure 12.2 The most common job in most U.S. states in 2014 was truck driving.

Source: National Public Radio

Truckers won’t be the only ones whose jobs are taken by driverless vehicles. Taxi drivers and chauffeurs will also find themselves out of work. The profession of taxi driving has already been disrupted by the growing popularity of services such as Uber and Lyft, where anybody with a car can become a cabby. Driverless cars will sound the final death knell to the jobs of roughly 233,700 cabbies and chauffeurs employed in the United States.5

Uber’s CEO, Travis Kalanick, believes that the biggest cost component of running a taxi service is paying the car’s driver. In a talk at a conference, Kalanick said, “When there’s no other dude in the car, the cost of taking an Uber anywhere becomes cheaper than owning a vehicle.”6 To develop a car that can drive without a “dude” behind the wheel, Uber has invested $5.5 million to develop driverless-car technology, hiring dozens of robotics researchers from Carnegie Mellon University’s National Robotics Engineering Center (NREC).7

Driverless cars will transform other jobs in the gigantic economic value chain that supports the buying, selling, and maintaining of the automobile. We recently brought our car to the dealer for a routine service. While waiting in the service center’s waiting room, sipping free coffee from a Styrofoam cup and reading old, sticky magazines, we overheard a muffled argument between employees over their next week’s work schedules. The two employees were arguing about who would take the weekend shift. Little do they know that in a decade or two, clocking in on a Saturday may become a common occurrence.

When cars become capable of driving themselves, human passengers will no longer need to visit a car dealer’s service center during business hours. Cars will drive themselves to the dealership when they need service. Since most people won’t want their car to disappear at an inconvenient time, they’ll ask their car to go for service at 3 am and be home by morning. The 739,900 employees in the United States who currently work as automotive service technicians might argue about who’s going to take the 3 am shift, but no one will be there to overhear them.8

As jobs disappear, whether or not new jobs will appear in their place remains an open question. In the 1940s economist Joseph Schumpeter coined the term creative destruction to describe the restructuring process that follows the introduction of a disruptive technology. While this restructuring process touches several major parts of the economy, including equipment used and regulatory structures, its most visible and controversial manifestation is in the destruction of jobs.

Economists who are Schumpeterians take a positive view of the cycle of creative destruction. They believe that the net long-term effect of disruptive technology is job creation. Although a disruptive technology may displace an entire sector of workers, Schumpeterian thinking would argue that the long-term effect will be the creation of more and better jobs, as new industries spring out of the ashes of the old one.

Proponents of creative destruction point out that as technology destroys old industries, new industries emerge. Countless examples of creative destruction abound. Desktop-publishing software eliminated typesetting jobs, but it created new market opportunities for creative people and small firms who finally had their own tools to design and publish their own brochures, books, and newsletters. In the travel industry, web sites such as Expedia led to the near-elimination of the occupation of travel agents. Yet when travelers gained the ability to make their own travel arrangements, Expedia also helped spark the creation of a much larger and more active global tourism industry.

As artificial-intelligence software and robots become increasingly sophisticated and skilled, however, the notion that the process of creative destruction ushers in newer and better jobs for displaced workers is falling under greater scrutiny. In the previous two centuries, human workers displaced by a new technology could (at least in theory) find jobs in the industries spawned by the new technology. In contrast, in recent years as the automation of jobs climbs the skill ladder from manual factory jobs to white-collar analytical jobs, it’s harder to find uses for the human workers automation displaces. Because of the efficiencies enabled by modern information technologies, when old jobs go away, frequently the number of new jobs created is far fewer and these new jobs are poorly paid.

As more and more future work will be handled by intelligent software and robots, two key questions will determine whether the process of creative destruction winds up eventually being truly creative, or whether its long-term impact will be merely destructive. The first question is whether new jobs are better than the old ones, meaning as secure, interesting, and well paid. The second question involves the length of the period of displacement. Will displaced workers be unemployed for just a few months, or will their displacement stretch on for years? Ideally, displaced workers would be retrained and quickly rehired. However, in the worst-case scenario, workers displaced by technology would be forced to sit outside of the workforce for years, perhaps even a lifetime.

As machines take away human jobs, one potentially devastating effect will be to further exacerbate the trend toward income inequality, a growing global problem. Research published by antipoverty charity Oxfam shows that the world’s rich are getting richer. The percentage of the world’s wealth that’s owned by the wealthiest 1 percent of the global population has increased from 44 percent in 2009 to 48 percent in 2014 and is expected to continue until, in the next couple of years, the wealthiest 1 percent will own more than half of the world’s assets and resources.9

An in-depth analysis of creative destruction is beyond the scope of this book. We introduce the concept here to demonstrate what could happen when driverless cars—like other disruptive technologies before them—rearrange the structure of several industries and take away millions of jobs. The worst-case scenario would be that as driverless cars disrupt industries and remove the need for human drivers, the already widening gap between rich and poor will only grow larger. On the other hand, a more positive outcome could be that driverless cars create economic growth and high-quality jobs for people at all levels of society.

Let’s examine some industries whose profitability will be dented by driverless cars. As the old saying goes, one man’s gain is another man’s loss. While driverless cars will save lives, fuel, and time, the losers will be the companies whose business models rely on the morbid profits generated by car accidents. These morbid merchants include a broad array of businesses, from car insurers to personal-injury lawyers, from body shops to part suppliers, from highway-patrol officers to defensive-driving instructors, from organ-donation organizations to emergency-room operators, and from traffic courts to jails.

In the United States, each year the total population spends a total of one million days in the hospital as a result of injuries from car accidents.10 Approximately 20 percent of organ transplants in the United States originate from victims of fatal traffic accidents.11 Even prisons rely on the weakness of human drivers. In 1997, 7 percent of jail inmates and 14 percent of probationers were in for driving while intoxicated (DWI).12

Car-related foibles earn cities billions of dollars each year from collected fines. An unpleasant truth about law and parking enforcement is that tickets are sometimes given not as a matter of public safety, but in order to maintain a municipality’s coffers. If humans were no longer speeding or parking badly, an important source of revenue for many municipalities would disappear.

In the United States alone, an estimated $6 billion of revenue is generated from speeding tickets each year.13 In an average year, New York City collects more than $600 million from parking tickets.14 A world of driverless cars that obey the law perfectly and have recorded data to prove it would disrupt revenue sources on which cities and states have come to rely.

Another industry that will need to be revamped is the business of selling car insurance. The jury is still out on how, exactly, the $200 billion-a-year auto insurance industry will be affected. One the one hand, insurance companies might see a boom in their profits as driverless cars have fewer accidents, costing less money in claims. On the other hand, if car accidents become exceedingly rare, people who own driverless cars might pressure companies to lower their insurance rates. In the United States, since car insurance is regulated at the state level, consumers could pressure their state governments to eventually eliminate mandatory car insurance requirements altogether.

Driverless cars will force the law and insurance companies to reconsider how fault is assigned in car accidents. Insurance legal scholar Robert Peterson writes that insurance and tort law (the law of who’s at fault) are like fraternal twins: not identical, but a reflection of one another. Peterson states that as autonomous vehicles gain popularity, “an increasing amount of liability for injuries is likely to bypass drivers and alight on the sellers and manufacturers of the vehicle.”15

If the burden of liability is passed from individual human driver to driverless vehicle, insurance companies will be forced to change how they structure the cost of insurance. Traditional vehicle insurance premiums hinge on the human driver’s risk profile. If the age, gender, and driving record of a car owner are no longer relevant in the calculation of insurance premiums, traditional ways to assess a driver’s risk will no longer apply.

If driverless cars were to be insured in the same way that products are, the manufacturers of the vehicles would be legally required to assume liability in the case of an accident. The cost of insuring a driverless car would be based on the potential risk the car represents as a product. New ways to assess a car’s risk profile would have to be invented, perhaps the humansafe rating of the car’s operating system we discussed earlier, or the total number of deep-learning miles the car’s “fleet mind” has collectively driven.

If insurance companies held car manufacturers responsible for passengers’ safety, a tremendous amount of work would have to be done to legally clarify exactly which manufacturer was at fault in the case of a driverless car accident. The two primary manufacturers in question would likely be those that provide the car’s operating system and those that provide the car’s mechanical body. Given the complexity of a driverless car’s operating system and the tight integration of hardware and software, however, deciding which manufacturer is ultimately at fault will a difficult process, particularly in cases where misuse or hazardous road conditions are involved.

Another area that will need further exploration in assigning liability is the issue of car maintenance. If the owner of a driverless car or taxi were to fail to obtain regular software and hardware updates for his vehicle, it would no longer be an open-and-shut case that the car’s manufacturer was at fault. A good corporate lawyer could argue that if a mechanic tampered with a car’s operating system or broke a critical hardware sensor, the mechanic—not the manufacturing company or the car’s owner—should be responsible for paying damages resulting from an accident.

One solution to the problem of car insurance would be for taxi companies to offer “per ride” insurance as part of the car’s software guarantee. Before hopping into a driverless taxi, a passenger would be asked to agree to accept whatever harmful consequences might arise as a result of riding in the car. Today we buy our computers with a click-through license. Perhaps someday, as we clamber into a driverless taxi pod, we may find ourselves squinting at a 200-page click-through license that asks us to agree to waive our right to seek retribution if our taxi winds up in a car crash.

We predict that driverless cars will look different, both inside and outside. The steering wheel will disappear, the dashboard will become flexible workspace, and the car’s cabin will contain whatever people need for their on-board leisure and work activities. Outside, cars won’t need side mirrors or tail lights.

As we described in chapter 3, our prediction is that the car industry of the future will divide itself into two broad categories: companies that make standard-issue utilitarian transportation pods, and companies that produce special-purpose cars for consumers, ranging from tiny one-person custom pods to large, luxurious mobiles for sleeping or work. Most of the new cars will be sold to transportation companies rather than directly to consumers. While the market for special-purpose, privately owned cars will be relatively small, it will need skilled car designers.

Figure 12.3 Passengers relax with electronics in this driverless concept mockup.

Source: Rinspeed AG; image © Rinspeed, Inc.

One positive side effect of driverless cars will be that consumer car design will enjoy a renaissance, a new golden age of automobiles. In the 1950s and 1960s, car designers created cars with showy large fins, painted in unapologetically cheerful colors. Driverless car designers will specialize in shamelessly luxurious or cleverly designed multipurpose flexible interiors that enable people to sleep, eat, and work inside their cars.

As safety becomes less of a concern, perhaps consumers will design their own car bodies with the help of intelligent, automated design software. New car buyers, even those who know nothing of car design, will browse through virtual showrooms online. As their eyes alight on a pleasing design, their computer will note the dilation of their pupils and show them several additional iterations. Of course consumer’s car designs would be subject to some restrictions in order to obey the laws of aerodynamics. To be considered “street legal,” consumer’s designs would also have to meet other established basic safety guidelines in order to be manufactured.

The buyer and software would follow an iterative design process, going back and forth several times to refine the new car’s shape and styling. Once a buyer settled on a design, the car would take a week to manufacture. Its body panels and chassis would be 3-D printed out of carbon fiber, creating a frame as light and strong as a bird’s bones. The freshly printed car would be sent on its way and programmed to text its new owners when it was an hour away from their home. Upon arrival, the new custom car would glide into the driveway, unlock its doors, and present itself to its new owner/passengers.

In an era of driverless vehicles, some automotive jobs will be quite specialized. A new high-paying specialty will emerge, that of software mechanic. Software mechanics will be automotive engineers who specialize in a particular aspect of a car’s operating system, either low-, mid-, or high-level controls. Some software mechanics will be reliability specialists who advise car buyers on the merits of different humansafe ratings.

Another specialty will be noise and vibration cancellation. Anyone who has tried to sleep in a rocking, rattling bed in an RV that’s in motion has experienced the discomforts of sleeping in a moving vehicle. Acoustic dampening, vibration cancellation, and motion compensation have long been an area of engineering expertise in many other fields. Automotive engineers who specialize in predictive signal processing (the same technology used by noise canceling headphones) will be able to make driverless cars smoother and quieter.

Another side effect of driverless cars that we foresee will be that the process of marketing products gains a new physical dimension. Driverless-car software will become the site of a new marketing battleground: route bidding. Today’s traditional static maps point out local “points of interest,” notable landmarks that could be anything from restaurants to tourist attractions to parks to shopping malls to museums.

In a driverless future, businesses will pay the companies that make HD maps to be presented as a “point of interest.” When a passenger hails a driverless taxi and asks to get to her destination, the pod’s operating system will ask whether she wants to stop at a few, specially chosen, destinations. Passengers who agree will get 25 percent off on every store they stop at along the way.

The idea that merchants can influence a customer’s experience in return for free or discounted prices is not new. Even now, people enjoy reading content on free websites whose business model is based on online advertising. Most of us accepted this new kind of “free” tradeoff long ago. We permit companies to mine the contents of our emails and our text messages in exchange for free email services and cheap phones.

Driverless car passengers will negotiate their terms as well. Savvy passengers will know how to exchange their physical presence at a “point of interest” destination for reduction in taxi fare, or if they own the driverless car, to receive cheaper fuel. Restaurants will agree to split the cost of the gas for a family’s road trip if their digital profile indicates that each time this family dines out, they spend $200. Some passengers will trade the value of their time. In exchange for a slightly longer and less convenient route, they’ll get cheaper taxi fare.

Business and restaurants that skillfully find ways to route customers their way will benefit from driverless cars. Another industry that will change is the retail business. Driverless cars will be the latest disruption in an industry that’s already been transformed several times over the past century, first by the introduction of mass production, then malls, then big box discount stores, then online retail.

Figure 12.4 Autonomous delivery method.

Source: Image courtesy Starship Technologies

In ancient times, rare spices were transported in camel caravans from the Far East to European markets. Today, tankers carry mass-produced goods to ports all over the world where gigantic containers are loaded onto trucks and carried to the loading dock of the store. Regardless of the nature of the product, transportation costs factor into its price. For physical products, transportation costs account for approximately 14 percent of the price of agricultural goods, and 9 percent of the price of manufactured goods.16

The cost of transporting goods to the buyer has always been a key element in determining a retailer’s business strategy. Driverless cars will remove one major competitive advantage enjoyed by large companies, economies of scale. As the once-prohibitive costs of transporting cottage goods to market shrink, small companies will be able to compete on price with larger companies.

One retail industry that’s poised for disruption is that of locally grown and organic food. Consumers happily pay top dollar for fresh, locally produced, farm-to-table food. Consumers also like the idea of supporting a diverse agricultural economy made up of several small regional farms. Despite the appeal of locally grown food, however, most of us still wind up buying factory farmed produce in the grocery store. Since they grow and transport food in high volumes, industrial-scale corporate farms can survive with smaller profit margins on individual products, and therefore are able to offer consumers lower-priced food in chain grocery stores.

Driverless trucks will enable artisan food producers to compete with corporate factory farms. Our friends in upstate New York own a sheep farm where they enjoy a peaceful life in the countryside growing organic vegetables and tending their animals. The most expensive and onerous part of their go-to-market strategy is their biweekly drives to the city where they sell their fresh merchandise in urban farmer’s markets.

Twice a week during the summer months, their market day begins at 1 am. The drive to New York City takes four hours, leaving them one hour to rest and another two to set up before the market opens at 7 am. At the end of a long day of selling their wares, they drive back in the dark. Imagine if they could buy a driverless truck and spend the journey sleeping soundly in the back. Even better, they could broaden their commercial reach by sending some of their produce off in a driverless vehicle to other regional markets where a colleague could sell their products on commission.

Small farms are just one of millions of regional-scale manufacturers whose business model is burdened by transportation overhead. Any company that produces small runs of perishable lower-margin commodities needs an efficient distribution network to remain profitable. Networks of efficient driverless transportation vehicles will enable small firms to sell their wares at regional points of retail at prices that are competitive with those of mass-produced, corporate products.

One of the major components in the cost of transporting goods has been the salary of the human driver. Companies deal with the high cost of salaries by delivering goods to retail outlets using one large truck rather than two or three small ones. Cost-conscious shipping companies aggregate several individual shipments into a single, large delivery vehicle. This approach has led to the widespread use of an inefficient “hub and spoke” transportation model that delays delivery and causes vehicles to drive additional miles. In a hub-and-spoke model, individual shipments must first journey to the nearest hub, or distribution center, where they are aggregated with other small shipments into a single, larger one before being finally dispatched to their final destination. When the cost of the human driver is removed from the equation, a shipment can take a more direct route to its buyer.

When autonomous delivery vehicles deliver merchandise directly to stores or customer’s doorsteps, their size and shape will reflect the physical dimensions of the products they deliver. Today’s delivery vehicles have to account for the fact that there’s a human driver on board, therefore a substantial portion of their size is dedicated to the driver’s comfort and safety. For example, a human-driven vehicle that delivers pizza weighs more than a ton, even though the pizza being delivered weighs only a few pounds. In contrast, an autonomous delivery vehicle would not need airbags or a heavy, crash-resistant frame, spare tire, dashboard, or air-conditioning. It would be compact, lightweight, and cheap and just a little bit larger than its on-board merchandise.

Online shopping already has made inroads into traditional forms of in-store retail and each year, the number of goods that people buy online continues to increase. According to the NPD group, a market research firm that tracks sales instances across 165,000 stores worldwide, brick-and-mortar retailers have been experiencing a gradual drop in “buying visits,” visits where a buyer walks out of the store with a product in hand.17 Between the years 2012 and 2014, brick-and-mortar buying visits dropped by 13 percent, while online buying visits rose by 21 percent. Although in-person buying visits are still almost four times more common than online buying visits, as time passes, eventually online shopping will dominate.

Online shopping changes the trade-offs that consumers have to make. According to conventional retail wisdom, most people make their purchasing decisions based on “3 Cs”: Cost, Quality, and Convenience. For most of history, consumers had to choose two of these three ideal qualities. Convenient, high-quality goods were not cheap, whereas easily accessible cheap goods usually involved a compromise on quality. E-commerce, however, has changed the rule of the 3 C’s. As online retailers continuously accelerate the speed of their shipping methods and offer high quality products at low prices, the trend toward buying online is likely to continue.

Figure 12.5 Autonomous delivery truck.

Source: Inage courtesy IDEO

Driverless delivery vehicles will increase the appeal of online shopping even more. Some enterprising retailers will take advantage of the low cost of driverless pods to bring the physical store to the customer. For example, if a customer of the future wants to buy a new pair of shoes, she’ll order half a dozen candidate pairs of shoes online. A driverless pod will deliver several pairs of shoes to her home so she can try them on in private, test them out for size and comfort, and pack the unwanted pairs back into the delivery pod to take back to the store.

Driverless delivery vehicles will usher in a new era of e-commerce. Today, online retailers in urban areas already compete over who can deliver purchases more quickly. In population-dense cities, same-day delivery, even two-hour delivery, is becoming an increasingly popular option. Nearly instantaneous delivery by a swift, fuel-efficient pod will erode one of the few remaining benefits offered by brick-and-mortar stores, the ability to receive products immediately.

No analysis of a new technology would be complete without acknowledging one of its potential dark sides: criminal activity. Many of us have already experienced the dark side of computer crime in the form of malevolent data breaches and identify theft. Driverless cars will also appeal to ambitious and intelligent criminals who have a taste for high-tech crime.

Some hackers will apply their talents to stealing and compromising data from driverless car sensors, digital maps, and operating systems. Another type of attack that will require a less brainy perpetrator will be that of robojacking, or hijacking a driverless car by walking in front of it while it is stopped at an intersection. Robojacking will be a particular problem in countries that are already plagued today by crimes of kidnapping and ransom.

Robojackers will take advantage of the fact that driverless cars will be programmed to spare the lives of a human whenever possible. To stop a two-ton driverless vehicle in its tracks, all a gang of robojackers would have to do would be to exploit the vehicle’s built-in safety features. If a few robojackers stood firmly in front and behind a driverless car, it would be frozen in place, unable to move.

Most robojacking assaults would be made on vehicles carrying lucrative, high-value cargo. Occasionally, however, a passenger car would be captured. With no “manual override” to force the stalled driverless vehicle to speed away to safety, the terrified passenger would be a sitting duck, trapped in a bizarre AI nightmare.

Another new form of mischief might be that human drivers bully driverless cars by driving erratically near them. A human-driven vehicle zigzagging down the highway, weaving in and out of a driverless platoon, would create mayhem. Over time, this sort of disruption, however, would eventually die out. As the car’s on-board machine-learning software learns to share the road with vehicles exhibiting erratic driving patterns, human troublemakers would have to come up with some other new form of unpredictable behavior.

Speaking of potential mischief and unpredictable behavior, what will regular people do in driverless cars, once they no longer have to worry about driving? According to a survey conducted by Carnegie Mellon University, the most popular pastime for passengers in a driverless car will be using their mobile devices. Next on the list will be eating, then reading, watching movies, and, finally, working.18

Once people no longer have to worry about driving, they’ll find new ways to entertain themselves while they travel. Today most ease the tedium of driving by listening to the car radio. In fact, surveys show that nearly half of the time people spend listening to the radio is while they’re in the car.19 When people are no longer limited to hearing only their in-car entertainment, radio consumption will plummet while consumption of visual entertainment such as movies and video games will increase.

The crude, poorly designed in-car infotainment systems of today’s vehicles will no longer exist. Privately owned luxury mobile offices or commuting vehicles will boast their own entertainment devices. In contrast to their luxurious cousins, driverless taxis will be stripped-down, no-nonsense affairs. Passengers will spend their time watching media on their own private devices and socializing online over the car’s on-board wireless network.

For those lucky few who own their own mobile, driverless luxury vehicles, drive-time will also become time to indulge in their vice of choice, be it sex, drugs, or alcohol. We’ve learned from direct experience that many people have a strong interest in the future of vice. Every time we speak about driverless cars, someone approaches us privately afterward to ask “offline” whether we have thought about these three taboo “elephants,” the topics that everybody thinks about but no one wants to mention out loud. In a nutshell, our answer is “yes.” People will use driverless cars to indulge in all of these three popular vices.

There’s one caveat, however. Since it’s illegal to consume drugs in general, and against the law to consume alcohol inside a vehicle, if driverless cars are equipped with a camera that faces inside the cabin, some interesting things could happen. Deep-learning software could learn to detect the presence of people using drugs or imbibing alcohol in the car. If cities are struggling to make up for the lost revenue that used to come from parking and speeding tickets, one way they could revitalize their bottom lines could be to require that the car “report” on its passengers’ wrongdoings.

Sex in a driverless car, however, would likely not be illegal (as long it’s between two, unpaid consenting adults). One new line of driverless cars could be a “bed bus” model, complete with shaded windows for privacy. Over the past few decades, the consumption of pornography has been an accelerating force in the development of technologies like the VHS video player, streaming video, and the internet. Driverless cars could offer a comfortable new viewing environment for fans of pornography to immerse themselves in, particularly as virtual-reality goggles like the Oculus Rift make the experience even more intense.

What lies ahead? Robotics technologies are reaching a critical tipping point and driverless cars are finally showing real promise in becoming a safe and viable mode of transportation. I sometimes find myself wondering what it will be like to someday explain to younger generations how the act of driving used to be equated with adulthood and freedom. I imagine them snickering in disbelief when I mention that in high school, we studied driving for an entire semester.

Those of us old enough to remember what it felt like to drive will miss human-driven cars in the same way people once claimed they missed using a manual typewriter when word processors became available. Intelligent autonomous vehicles will swiftly seduce us with their efficiency and ease of use. Yet, I suspect that some of us will insist that we miss the feeling of our hands on the steering wheel and feet on the brakes, our memory of the hassles of driving cloaked by a fond haze of nostalgia.

Perhaps someday when driverless cars make travel nearly painless, people will find themselves craving a new form of entertainment: driving ranges. These future driving ranges won’t be for playing golf; they’ll be for driving old-fashioned cars around a track, a retro form of entertainment popular with the older generation and a few youngsters savoring the pleasures of being ironic. Maybe one of those people drawn to the driving range will be me.

A few decades from now when I’m retired and find myself with time on my hands, I may surprise myself and buy a membership in a driving range, let’s call it U-Drive. Like a temperamental writer of yore letting off steam by banging hard on the keys of an old manual typewriter, when I’m craving speed or need some meditative time behind the steering wheel, I’ll grab my protective driving helmet and ask my driverless car to take me to U-Drive.

Once I get there, I’ll hurry to the check-in desk in hopes of getting my hands on one of the more sought-after vehicles, an ambulance or a police car. Nothing like speeding around a race track to the accompaniment of a wailing siren! As I slide behind the old, familiar steering wheel, it will feel like coming home. I’ll sing along loudly to the antique radio inside the car. I’ll honk the horn until the other human drivers make rude gestures at me.

Some days, this future me might drive without a helmet, even without wearing a seatbelt if I’m feeling particularly bold. I’ll press my car’s gas pedal as hard as I can, gleefully ignoring the rusty antique speed-limit signs posted at regular intervals next to the driving range’s track. Regardless of how wild my fellow human drivers and I become, one thing is certain: the company that owns U-Drive will know how to handle us. U-Drive’s owners won’t tell customers this, but at the first hint of real trouble, their old-fashioned cars will shift immediately into driverless mode and their steering wheels and brakes will become useless.