THOUSANDS OF ATHLETES from around the world recently gathered in Beijing for the city’s annual marathon. But on the morning of the event the air was so polluted that many runners decided not to compete. Others took the extraordinary precaution of wearing a mask to keep from getting sick. Some criticized the organizers for not canceling the event after health officials announced that the air quality index that day was “hazardous,” well above the threshold at which citizens are urged not to engage in strenuous activities outdoors. Others noted that they could barely see the stadium through the smog. As one resident said, “It’s really hard to breathe when it’s like this.”

This occurred in October 2014, but the dilemma for Beijing is that these days it’s not an unusual occurrence at all. If you live in the Chinese capital, you start every morning by checking your smartphone app for air quality alerts. Regularly it’s on red alert, signifying hazardous levels, which is easily confirmed by looking out the window, where thick smog makes you wonder if you’re looking at a wall instead of glass.

Chinese authorities are well aware that deteriorating air quality, water quality, and food safety pose a significant threat to the nation’s economic development. Bright young Chinese academics aren’t attracted to live in such environments, despite the incentives of an economy with a booming GDP. The most appealing cities in the world—the ones attracting all the talent and innovation—are those offering a healthy, safe environment. It’s as simple as that.

Moreover, every business leader knows that no enterprise can operate successfully in a dysfunctional society, and that the environment is a critical determinant of whether the market, the community, or the nation is functional or not. Municipal leaders in São Paulo, Brazil, for example, are struggling with water-scarcity problems caused by rising water demand and falling water supply, very likely seriously affected by both climate change and deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. These problems are threatening the business environment and living conditions for the city’s eleven million people. Many other major cities, from Mumbai (Bombay) to Nairobi, face similar challenges with sewage, air, and chemical pollution.

It may seem obvious to point out that as we degrade our forests, waterways, soils, and air, and lose wild animals and plants, we should expect an inevitable decline in human wellbeing. We draw attention to this problem here because the scale of this decline is much greater than people imagine, with potentially serious economic consequences. As nature’s resilience is lost, thresholds in Earth’s physical processes are crossed that trigger runaway feedbacks, bringing abrupt changes, shocks, and stresses to our lives. As this happens, it no longer becomes possible to pursue economic development as we struggle with crisis after crisis. The future of our societies hinges on the resilience and sustainability of a stable climate and ecosystem. Or, as Petter Stordalen, CEO of Nordic Choice Hotels, says on the back of his business cards, “there is no business on a dead planet.”

The overall logic is simple. A stable planet provides us with the ecosystems we’ve learned to love and exploit. It provides us with the functions and services we need, from clean air to healthy food. These ecosystem functions and services form the basis not only of direct wealth but also of resilience—so we’re not only rich but also safe. Based on the ecological richness and the resilience that stability builds, we can fulfill our development needs and aspirations—from eradicating hunger to ensuring economic growth. But without this chain of factors, from stable ecosystems to resilience, we can’t expect economic development.

You might say, well, we’ve had great economic growth in the past, despite environmental degradation. But until around 1990 Earth’s resilience was high. Instead of incurring costs to the economy, ecosystems provided massive subsidies to the world economy. In fact, in a recent study by Robert Costanza of Australia National University and several co-authors, these subsidies were valued at about 125 trillion USD annually, or 1.5 times world GDP. The era of a free planetary ride is over.

SIGNS OF TROUBLE

One of the clearest warnings in recent times that human activities have been affecting the resilience of Earth was the collapse of the North Atlantic cod fisheries in the early 1990s off the coast of Newfoundland. After thriving for centuries under local fishing practices, the Canadian cod fishery in the late 1950s was assaulted by factory trawlers from around the world. By the end of the 1960s, the number of cod being taken increased almost four-fold to 800,000 tons a year. So many cod were being hauled in, the population wasn’t able to replenish itself, and by the end of the 1970s the annual catch fell to 139,000 tons. In reaction, Canada and the USA both extended their marine jurisdictions to 200 nautical miles (370 km), which pushed foreign fleets away. But foreign factory ships were soon replaced by Canadian ones, and the cod were fished to near-extinction until 1992, when Canadian federal officials finally declared a moratorium. By then it was too late. The cod fishery was destroyed.

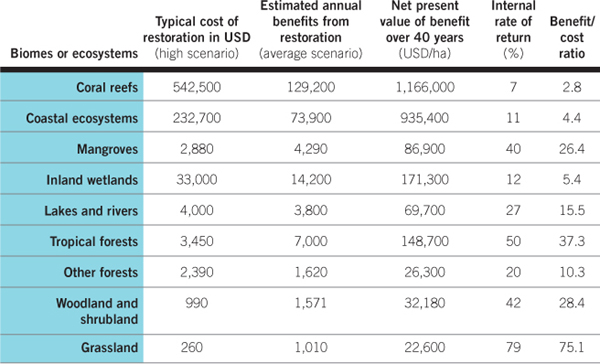

Wise management of ecosystems gives economic benefits. There are ample examples today showing that when we value, even at a conservative level, the role played by ecosystems in our economic activities, then sustainable practices and businesses are more profitable than unsustainable ones. Furthermore, sustainable management of ecosystems helps to build resilience, which forms an insurance capital in the face of various shocks. This is a key dimension of economic value.

This abrupt and irreversible collapse was a breakdown of an economic “fish-basket” worth an estimated 120 million USD in lost fish value (1989–1995) and several times more in lost incomes, ending a traditional way of life in many Newfoundland villages. More than 40,000 people lost their jobs. Similar collapses have followed in other marine systems around the world, including the Baltic Sea, where overfishing of cod and nutrient overload from cities and agriculture have turned large areas into dead zones.

Another example of human impact on the planet has come from the increased frequency of extreme weather events. Ever since we transgressed the planetary boundary for climate change—an atmospheric CO2 concentration level of 350 ppm— in the late 1980s, we’ve begun to see weather disasters such as heat waves, droughts, extreme downpours, and floods more often than we used to. In 2003, almost 40,000 Europeans died as a result of the worst heat wave ever recorded in the region, the largest environmental disaster to hit Europe in modern times. In Australia, a 12-year drought from 2000 to 2012 cost the nation an estimated 4 billion USD. In Pakistan, Afghanistan, Germany, and Thailand, massive floods displaced millions of people. When Hurricane Sandy in 2012 suddenly veered inland from its expected route in the Atlantic Ocean to strike New Jersey and New York, the storm surge put Wall Street 3 m (9.8 ft) under water and cost New York City a staggering 19 billion USD. In fact, the cost of natural disasters since the 1980s has been steadily rising, and true to the Anthropocene, it hasn’t been geological disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, or volcanic activity that have been happening more frequently, but rather climate events like heat waves, droughts, wildfires, floods, landslides, and big storms. Today, environmental disasters are estimated to cost the global economy more than 150 billion USD a year.

EARTH SUBSIDIZES WORLD ECONOMY

Another way to measure the economic impact of degrading our natural surroundings is to estimate what it would cost to replace the services we receive from them. Although we rarely consider this fact, Earth subsidizes economic growth to an astonishing degree. In fact, if you were to take into account the deterioration of social and natural capital as a cost of economic activities, many studies indicate that GDP-based growth would be significantly lowered, if not erased. Add up the cost of unsustainable use of ecosystems, natural resources, and the climate, and economic growth largely disappears in the USA, Germany, and China.

In the 2014 study by Robert Costanza and his colleagues, humanity lost ecosystem services worth roughly 20 trillion USD a year between 2007 and 2011 as a result of degradation of the environment. To put the 20 trillion USD loss into perspective, the GDP of the entire world adds up to about 75 trillion USD a year. Costanza and his colleagues considered only “direct” services to the economy from nature, such as freshwater for food production, soil quality, timber value, and so on. They didn’t include “indirect” ecological functions, such as maintaining enough top predators to ensure that landscapes remain productive and resilient or enough pollinators to keep agriculture going even in the event of a disease outbreak. For that reason, the study’s estimate is conservative. Even so, it demonstrates the staggering level to which the world economy is subsidized by nature. If businesses had to pay for these ecosystem services, the result would be a 27 percent reduction in net economic output for the world economy.

There’s no shortage of evidence these days that sustainable management of ecosystems is good for businesses as well as for communities, nations, and regions. In the UN’s first Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) in 2005, 1,360 scientists from 95 nations estimated that almost two thirds of the critical environmental services that humans rely on today are being diminished by our activities. Similar assessments have come from the Natural Capital Project, and The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) initiative. The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has also been launched as a “sister” to the IPCC to map out the evidence of how biodiversity and ecosystem services contribute to human development. We’re sitting on a mountain of knowledge showing that everything we value on Earth, from the morning dew on swaying grass to the proud herd of wildebeests trekking across the savannah, determines our ability to prosper.

Every part of the planet, living and non-living, from phytoplankton in the oceans to mineral deposits in the bedrock, interacts to establish the biophysical configuration of Earth. It’s no coincidence that we have big stable biomes such as the taiga or the endlessly blue-white ice sheets, which, together with the global cycles of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and water, sustain the planet as we know it. Living organisms in the biosphere, from soil bacteria to dolphins, interact to create food webs in complex predator–prey relationships. They also serve as biological “insurance companies” by providing redundancy in the face of “low-probability, high-impact” events. In many landscapes or marine systems, different species may have the same or similar functions, such as decomposing soil or pollinating plants. But they’re not equally sensitive to a virus disease or drought or shift in air temperature, which gives ecosystems what we call “response diver-sity”—a critical element of resilience. As nature has learned the hard way over billions of years, you don’t want to put all your money on one horse.

Mangrove forests in West Papua, Indonesia, are nurseries for fish and build resilience in tropical coastline ecosystems.

Nature’s so resilient, in fact, we’ve been lured into a false sense of comfort. We’ve convinced ourselves that even unsustainable development—losing “a few species here and there”—can’t be such a big deal after all. But it is a big deal. We’re in the midst of the sixth mass extinction of species on Earth. Ecosystems can cope with this, to a point. If the species we lose are lower down in the food web, they can be replaced by others that play the same functional role. But that can’t go on forever. When the last critical functional group is lost, the system collapses. And as we increasingly realize, large ecosystems are particularly sensitive to losing top predators—keystone species such as cod, sharks, lions, and eagles. When these species are gone, the cascading effects can be devastating, causing entire ecosystems to crash.

WOLVES, TREES, AND BUMBLEBEES

A classic example of how change can cascade through an ecosystem took place in Yellowstone National Park. During the 1920s, wolves, one of the top predators in the park, were killed off by government hunters. For the next seven decades, the park’s ecosystem evolved without wolves, resulting in a huge increase in elk, which in turn had knock-on effects for the entire park. The elk overgrazed large tracts of land, resulting in a decline in forest land, and water flows, as well as the loss of habitats for species like songbirds and beavers. Then in 1995, following a heated debate among environmentalists, landowners, and park authorities, 14 wolves were reintroduced. Today there are about 100 wolves in the park, and we now know the extraordinary impact of their return. By controlling the elk population, against which only hunting by humans had provided a restraint, the wolves have reinstated the desired ecological balance. Reduced grazing pressure has allowed the forests to return, growing several times faster in only six years, resulting in more stable rivers (protecting river banks), and providing habitat for returning species such as eagles, badgers, and beavers. In just over a decade, the unique Yellowstone landscape was back in shape.

Another classic example of how sustainable management of ecosystems provides economic and social values to society comes from New York City. More than a century ago, officials had to make a decision: build a water-treatment plant to clean water flowing to the city or protect the 4,900 square km (1,900-square-mile) watershed, mostly in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York, let the forest regulate the water flows, and use nature as the treatment service for the water supply. They chose the latter, and today the city’s 8.4 million residents enjoy 4.5 billion m3 (1.2 billion gallons) of the nation’s cleanest water every day. To replace the current system with a conventional treatment plant, consuming energy and chemicals, would cost as much as 10 billion USD, officials estimate. By using the forest as a water-regulator instead, the city saves many millions of dollars a year in reduced operational costs.

A more recent example of the value of ecosystem services came to light in 2012, when the UK sent scientists to Sweden on an unannounced mission to capture short-haired bumblebee queens. Once common in southern England, the bumblebees had vanished by 1988 after nearly all of the nation’s wildflower meadows had been replaced by croplands. The irony of this development was that these same croplands depend on bumblebees and other insects for pollination, a service estimated to contribute at least £400 million a year to the UK economy. So the loss of bumblebees was a disaster.

A minor controversy erupted when the Swedish public discovered what the British scientists were up to, particularly as they had no official permission to collect Swedish bees. Sounding the alarm, local environmentalists warned that if the scientists collected too many Swedish bumblebees “we could end up in the same situation as the UK.” One retired biologist fumed that the interlopers were “no longer the world’s rulers as they were before when they just went around and took stuff.” But as it turned out, in order to avoid a diplomatic skirmish between the UK and Sweden, the British scientists were quietly and rapidly given permission for their originally clandestine mission by Swedish authorities, and the controversy subsided. The British were then able to focus on the challenging job of reintroducing the bees to the English countryside, where conservationists had replanted areas with wildflowers, clover, and vetch. Nearby farmers also did their part, creating “green corridors” for the bumblebees along the margins of their fields, which they left undisturbed. They, more than anyone, wanted to see the bumblebees settle in back home.

The bumblebee incident was a reminder of the often unsung role played by so many species in landscapes and marine systems—and the cost to our economies when they’re removed. As we mentioned in Chapter 3, the world is losing species today at a devastating pace, 100 to 1,000 times faster than the natural background rate. Unless this mass extinction is halted, the price tag could be too high to calculate.

CSR IS DEAD

More and more companies have reached the same conclusion: Sustainable business is good business. When General Electric announced that it has generated more than 160 billion USD in revenue, realizing 300 million USD in savings since 2005 by integrating energy efficiency into their production chain, it turned some heads. When they pointed out that, just as companies like Puma, Walmart, and Unilever are also doing, they make an increasingly significant portion of their net profit from sustainable business solutions, ranging from wind farms to solar voltaics and hyper-efficient turbines, it sent a clear message. The environment is no longer the domain of social or ethical responsibility in a company. It’s increasingly becoming core business, the true heartbeat of the enterprise, the key to either dominating a market or disappearing.

A few visionary business leaders have known this for some time. For them, the triple bottom line of people, planet, and profit has always been an integral goal. But it has only been during the past three to five years that a major mind-shift is emerging in the business world at large, as climate and ecosystems issues have moved out of the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) departments and into the boardrooms.

Speaking on a panel at the Stockholm Food Forum in May 2014, Peter Bakker, President of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), a global network of 200 multinational companies representing about 10 percent of the world economy, declared that “CSR is dead.” To survive in a world of rising competition for finite and increasingly dwindling resources, Bakker explained, of increasingly volatile and uncertain fossil fuel prices, of potentially destabilizing feedbacks from Earth for entire societies, we can no longer consider the planet as an external issue for businesses. Instead the planet is the business of business. Bakker’s own organization has taken this to heart, transforming their so-called Vision 2050 initiative into an Action 2020 plan that translates the science of planetary boundaries—including climate, biodiversity, water, land and nutrients—into science-based definitions of what green business means for the next few decades and beyond.

The EU recently finalized work within the so-called European Resource Efficiency Platform (EREP), which analyses the future competiveness of European industry. It has become increasingly clear, putting all the planetary risk cards on the table, that the only way for Europe to compete, creating growth and jobs in the future, is through major improvements in resources efficiency in the short term, and, in the long term, through a transformation to a circular economy. In a globalized world, where all citizens have a right to resources for development, 100-percent-green development just makes the most sense from the perspective of competiveness and the ethical responsibility of sharing. But the argument becomes even more persuasive if you consider the rapidly rising risks of global environmental disasters. Sustainability is the shortest path to prosperity, and it hinges on us being wise stewards of the remaining beauty in our ecosystems and planet as a whole. As Lord Nicolas Stern wisely pointed out at the World Economic Forum in 2014, sustainability is not a growth story, it is the only growth story for the world.

A NEW NARRATIVE

It’s high time we changed the narrative of why we should care for our planet. It’s long overdue, in fact, by at least 40 years. As “environmentalists” we’re probably a big part of the problem. We’ve created a whole movement based on “protecting” the environment, and it has been so successful, it has contaminated everyone’s thinking. We now live in a world where nature is placed on one side and society on the other. Environment versus development. And the two never meet. Economists are stuck in the obsolete mantra of addressing impacts on the planet as “externalities.” Can you think of anything less accurate? How can you stand on a planet—one that is the source of all wealth—and declare it to be an externality?

In our attempts to solve environmental problems through civil, societal, business, and policy efforts, we get locked into the logic of “protecting” the environment from human damage. In UN climate negotiations, we talk about “protecting” the climate system and “burden sharing” to solve issues of responsibility. In the biodiversity convention, we focus on maximizing what’s left to be conserved, to be “protected” from humans, appealing first and foremost to our ethical responsibility to protect other species. Businesses over the decades have responded very wisely to this state of affairs by creating a whole league of senior CSR officers and heads of the environment. Any company with global ambition has declared an altruistic engagement in “protecting” some element of the externalities affected by human action.

Well, this era is over. The story has changed. In the saturated and turbulent world of the Anthropocene, where we need to become stewards of the entire planet. Becoming planetary stewards means recognizing that our grand challenge is not about saving a species or an ecosystem. It’s about saving us. It’s about making it possible for humanity to continue pursuing economic development, prosperity, and good lives. The planet won’t care if everything changes. It’s our world that’s at stake. Ultimately, any business must recognize that there can be no business in societies destabilized by abrupt social–ecological change. Only a stable climate and ecosystem can provide the resilience and sustainability we need to make our cities and villages livable.

Can we make the shift quickly enough? We think the answer is yes. Roughly 60 percent of the urban areas the world will need by 2030 have yet to be built. We know how to do that now in cost-effective ways that are smart from a climate, water, energy, and nutrient-recycling perspective. We also know how to plan urban areas for resilience with natural buffer zones to safeguard us against storms and floods. We know how to integrate ecosystems into dense urban areas to improve quality of life and diversity in ecological functions. The world will invest an estimated 90 trillion USD in new infrastructure over the coming decades. A mere four percent increase in that investment could make the entire infrastructure green from a climate perspective.

The only thing holding us back, in the end, is the obsolete but remarkably stubborn belief that what worked for us yesterday will work well tomorrow. We need a new paradigm of human prosperity within the safe operating space on Earth, growth within planetary boundaries, a development paradigm in which we succeed by becoming stewards of the remaining beauty on Earth, not as an aside, but as an integral part of our lives and businesses. We need to make it as natural as breathing. Once we do that, success in creating the base for thriving future generations will be that much closer.

A boy from the island of Batanta dives for shells in the waters off the Raja Ampat Islands, West Papua, Indonesia.

Amphibious houses in Maasbommel, the Netherlands, are built with floating foundations that enable them to rise by up to 4 m (13 ft) in response to changes in the water level.