WHAT DOES IT MEAN these days to talk about environmental stewardship? How can we safeguard the planet if the daily actions of billions of people are undermining Earth’s basic functions?

Ask Moustapha Amadou, an elderly farmer in southwestern Niger, where the life-giving summer rains now arrive later, sometimes several weeks later, than they used to. Amadou lives on the edge of the Sahel in the small village of Samadey, about 100 km (62 mi) north of Niamey, the capital of Niger. During the past 20 years, farmers in this region have become increasingly anxious about what they’ve been witnessing—even more variability in an already variable rainfall regime. Something’s changing, they realize, and it’s happening quickly.

After the first heavy downpour in June, the savannah around Samadey smells of warm, sweet tropical fruit. The gray, dusty expanse has turned into a muddy brown landscape. Children are playing in the flooded lowland at the center of the village, recalibrating their bodies and minds from the dry to the wet season. There’s an aura of celebration in the community, a sense of being blessed.

Before he does anything else, Amadou checks to see if the rain has moistened the soil in his field to a depth of at least one hand’s length. Then, and only then, following a practice that goes back more generations than can be remembered, will he decide if the time has finally come to plant the precious millet seeds he’s kept stored away during the long, hungry dry season.

Things don’t seem quite right to Amadou. For one thing, the lowland shouldn’t be so drenched after the first rainfall. The land surrounding the village should absorb at least the first four to five rainfalls, filling up the 62-m (203-ft) deep, hand-dug, village well. The villagers rely on that well for precious freshwater throughout the eight-month dry season. But for some time now, the rains have fallen with a higher-than-normal intensity. Instead of soaking into the soil, as every farmer wants them to do, the rains from these downpours wash over land, triggering erosion, which every farmer dreads. This is the new curse.

The gradual warming of Earth has not only shifted rainfall patterns, it has also increased the likelihood of sudden downpours, floods, heat waves, droughts, and wildfires. Under such circumstances, it’s not enough any more for small farmers like Amadou to manage their local environment. He, like all of us, must learn how to become planetary stewards.

But what does that mean exactly? And how do we achieve it? The answer, we believe, involves a rapid transition from a way of life based on exploiting natural resources for our own benefit to one based on strengthening Earth’s resilience. Whether we’re farmers like Amadou, factory workers in Shanghai, fishermen in Indonesia, or shopkeepers in Des Moines, Iowa, we all depend on functioning lakes, forests, waterfalls, oceans, and glaciers for our wellbeing and prosperity. No matter how modernized we think we are, how alienated from the natural world, none of us can get by without thriving ecosystems all around us.

Farmers like Amadou are a step ahead of most of us urban dwellers, because his livelihood is so directly rooted in the variable swings of local weather. The challenge for the rest of us is to recognize that we also depend on sustainable management of watersheds, river basins, and large biomes such as glaciers and forests, as well as the entire climate system. The rainfall in Samadey is intricately linked to the way we manage ecosystems and the climate across the planet.

NEW RULES OF THE GAME

The challenge we all face now—to pursue a prosperous future for everyone within the safe operating space of planetary boundaries—calls for bold new strategies for governance at both the global and local levels. It won’t be enough to apply the “top down” power of institutions, enforcement agencies, global justice systems, international partnerships, new trade rules, or global regulations to demand changes at the planetary level. Nor will it be enough for “bottom up” grassroots activists, community managers, business innovators, educational experimenters, or public–private organizers to work their magic at the local level. We’re going to need both approaches. And we need them to interlink and work together.

Fortunately, these two strategies can support each other, with “top down” forces creatively stimulating “bottom up” ones, and vice versa. Clear rules from the top, for example, repeatedly asked for by business leaders, can create clarity at the bottom, stimulating investments in sustainable and resilient business strategies. We just need to establish the new rules of the game to get things started.

It’s become obvious, for one thing, that some form of strengthened governance at the planetary scale will be required to achieve the kind of transformative changes the world needs. In a world where the majority of inhabitants have yet to claim their fair right to development, strengthened global governance will be necessary to secure a just distribution of ecological space. We’re going to need global guardians of planetary boundaries—not as a means to “rule the world,” impose a cap on development, or limit growth, but rather to make sure we don’t derail Earth from its current stable condition.

Right now, we have nothing of the sort. In fact, leaders across the world remain skeptical about the need for governance of the Earth system. But the game has changed. We no longer have the luxury of debating whether or not we need to make ends meet at the global scale. We can’t afford to argue any more about whether or not to stay within a common global carbon budget, for example, or a land budget, or a freshwater budget. Knowing what we know now about the risks of crossing catastrophic tipping points, we must strengthen our capacity to meet global sustainability targets.

Despite the good intentions and tremendous efforts of men and women around the world who have signed more than 900 environmental treaties during the past 40 years, we’re still moving in the wrong direction. We still lack any mechanism for planetary-scale governance with the teeth to guide the development of our modern economy. The “tragedy of the commons”—in which shared resources are squandered by selfish but, given the rules of the game, “rational” behaviors—has never been more pronounced than today, when separate nations pursuing self-interests have kept the global curves of negative environmental change all pointing the wrong way.

The problem is that the old approach no longer works. In the Anthropocene, when humanity has saturated Earth’s capacity to buffer our pressures, one nation’s unsustainable growth is another nation’s threat to growth. We shovel environmental risks across the world in a way that wasn’t the case a decade or two ago. Global challenges require global solutions. Development at the local, national, and regional scales must now be capped by globally agreed-upon sustainability boundaries and targets. That’s why it’s become necessary to strengthen global governance on environment and development, which will support local actions and innovations.

But strengthening governance at the top doesn’t mean weakening it at the bottom. On the contrary, we’re convinced that we need to transform societies both at the bottom and at the top, creating a dual pressure on beneficial processes leading to a sustainable world. One approach might be to strengthen the multilateral governance system within the UN. The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), for example, should be transformed into a specialized agency with regulatory mandates at the global scale (like the WTO and WHO)—a United Nations Environment Organization (UNEO)—with strategies to empower local communities and businesses.

This upgrading has been discussed over the years, and in 2012 UNEP took a small step in that direction by establishing a universal membership in its governing council and providing a more stable funding base. We must now be brave and experiment with systemic shifts in the way we govern for global sustainability. The aim would be to universally agree on global sustainability criteria, such as planetary boundaries, that are monitored, reported, and enforced, with the objective of fostering not only a step-change in innovation, experimentation, learning, and practices to support human prosperity, but also a just way of sharing ecological space with all fellow citizens in the world, while staying within safe planetary boundaries.

It’s not for us to stipulate what these practices and innovations should be. But we do see an urgent need for a clearly defined playing field where all nations, businesses, and communities know the rules of the game. We believe a new set of global regulatory measures will be necessary, ranging from a global carbon tax to international agreements on all planetary boundaries. We don’t believe these will hamper the operations of market economies or stifle innovations and technology leaps. On the contrary, we all know that markets are social constructs. They’ve always required a “helping hand” to keep them focused on their primary role, to provide human wellbeing.

New legal regulations, norms, and values will be needed, including international recognition of every individual’s right to a resilient and well-functioning Earth system. Effective compliance regimes will also be required to compel collective action. We also urgently require a new global strategy for sustainability, building upon the voluntary action plan known as Agenda 21. Adopted at the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1992, Agenda 21 offered ideas to local, state, and national governments for sustainable ways to combat poverty and pollution while conserving natural resources.

A key step in this direction is to support current efforts to transform the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) into globally agreed-upon Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The eight MDGs, established as a result of the UN Millennium Summit in 2000, have been remarkably successful during the past decade in stimulating and focusing international efforts to alleviate poverty and hunger, among other important goals. Now we’re turning a corner. We’re starting to see the contours of a new paradigm building on the concept of development within the safe operating space of a stable planet.

It started with the Ban Ki-moon high-level panel on global sustainability, which formed the basis for the UN Earth summit in 2012 (the UN Rio+20 conference). For the first time, world leaders discussed the fact that global sustainability is now a prerequisite for poverty alleviation and that rising global environmental risks may undermine future progress in development. The UN Open Working Group (OWG), advancing the draft plan for the SDGs, has carried these insights forward in 2013–2014, and the final set of proposed SDGs actually includes the contours of a development agenda within planetary boundaries.

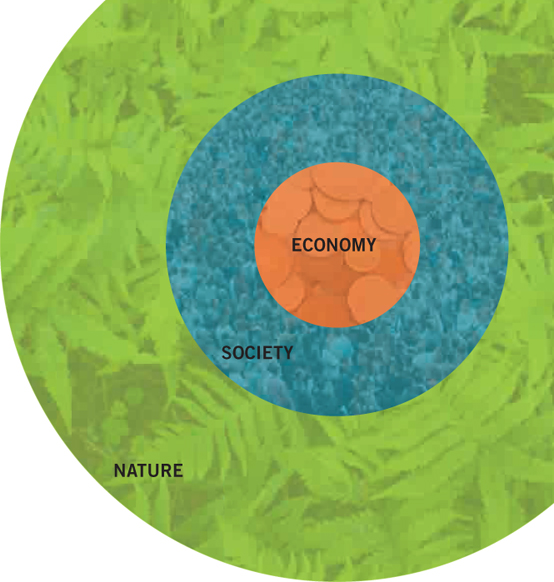

Figure 7.1 Shifting to a New Paradigm for Sustainable Development in the Anthropocene.

Attaining world-development aspirations—from eradicating poverty and hunger to economic growth—requires that the world evolves within the safe and just operating space of a resilient and stable Earth system: abundance within planetary boundaries. This changes our paradigm for development, away from the current sectoral-pillar approach of social, economic, and ecological development, as separate parts often seen as contradictory forces, with the economy advancing at the expense of natural and social capital. Now we must transition toward a world logic where the economy serves society so that it evolves within the safe operating space on Earth.

Most important, the proposed SDGs include an aspirational set of goals that constitute what we could call the social “end game” for humanity. The objective is not to reduce poverty and hunger by 50 percent, but to eradicate them entirely. The new agenda is about enabling education, health services, gender equity, and transparent governance for all. The 17 proposed goals—and more than 150 targets—include global sustainability goals that essentially cover all nine planetary boundaries. There are explicit goals on oceans, climate, ecosystems, and freshwater. Taken together, the SDGs show that we’re entering a new development logic, based on a new narrative, in which world leaders recognize that human progress hinges on Earth resilience.

Such an integrated SDG framework requires that we abandon our old approach to sustainable development, based on the three separate pillars of social, economic, and ecological sustainability. Instead, as we recently showed in a scientific paper produced by a team led by David Griggs of the Australia National University, we must adopt a nested development framework in which the economy is a method to serve society, which in turn develops within the safe operating space of planetary boundaries.

A NEW SHADE OF GREEN

At the same time that policymakers have been struggling to negotiate new approaches to global governance (with meager results so far), more and more business leaders have realized that “business-as-usual” is no longer an option. Until recently, too many executives operated under the assumption that “environmental stewardship” meant wrapping their profit-focused business core in a flowery shield of green consciousness. This superficial camouflage resulted in various attempts to “green-wash” annual reports and results. But today we see a shift. The Anthropocene has entered the boardrooms, not as a threat but as strategic “insider” information about the risks and opportunities of tomorrow’s markets—in simple terms, as core business.

Consider, for example, the cornerstone report, Vision 2050, by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), which has recently been translated into an Action 2020 strategy. While the report laid out a pathway for business to reach sustainability by 2050, the Action 2020 document is a result of a profound effort to translate the science on planetary boundaries into actionable targets for business. Specifically, Action 2020 identifies a set of “must-have” immediate actions to enable businesses to progress within a safe operating space, by staying within a science-based carbon budget, raising agricultural outputs on existing land without increasing water-use and nutrient-loading, halting deforestation, and biodiversity loss.

Similarly, the “Shell Energy Scenarios to 2050” describes an era of “revolutionary transitions,” including a global resource crunch, global environmental risks, and momentous growth in energy demand. The latest scenarios offered a “blueprint” for a sustainable energy future that meets both social and ecological requirements. In the same vein, “Getting into the Right Lane for 2050,” by the National Environmental Assessment Agency of the Netherlands (PBL) and the Stockholm Resilience Centre, assesses the feasibility of implementing a sustainable vision for Europe. It also shows that Europe can get into the right lane—within a safe operating space with respect to climate, energy, land, and biodiversity—while supporting economic development.

Probably the most comprehensive vision for future global sustainability, however, is a scenario analysis by the Great Transitions Initiative (GTI) led by the Tellus Institute. This analysis, covering most of the planetary boundaries, shows how challenging it is to provide a fair future for all within the world’s safe operating space. Even with the most ambitious and optimistic implementation of all the policy options within our current development paradigm, we show that humanity will face great difficulties in staying within safe levels of all planetary boundaries.

To us, this conclusion demonstrates two things: First, that action now is possible; and second, that “tweaking and tuning” of our current social and economic systems won’t be enough. We’re going to need immediate actions that aim at far-reaching systemic changes of our economies and institutions, our values and lifestyles, supported by a broad mind-shift that can trigger such a great transformation. The critical thing to remember is that these transformative changes have only one aim: to improve our prospects for growth and prosperity in the future, not to hamper them. Remember, without Earth resilience, there will be no world prosperity. Can transformational change happen fast enough? Well, in truth we do not know, but there are inspiring examples of social tipping points toward sustainable wealth.

One such example at the national level was what happened in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park a few decades ago. Like many people around the world, Australians were struggling to manage vulnerable coral reef ecosystems in the face of climate change, polluted runoff, overfishing, and other human and natural pressures. Confronted with declines in the populations of dugongs, turtles, sharks, and other fish, it became clear to everyone who knew the reef that the original management system was no longer adequate.

Walking together with nature, a mother and child stroll along Leblon Beach in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

One of the most controversial initiatives proposed at the time was to extend the zone closed to all forms of fishing from 6 to 33 percent of the total reef area—creating the largest no-take zone in the world. A critical step in the process was to convince local communities that the reef was facing many threats, and to enlist public support for protecting a larger area of the reef and managing it more flexibly. This was accomplished through a major “Reef Under Pressure” community consultation campaign, supported by a steady flow of science from leading international coral-reef scientists like Professor Terry Hughes of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University in Australia, and co-author of our original planetary boundaries research.

The successful campaign to rezone the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park has been recognized as a groundbreaking international model for better resilience management of the oceans. In a 2008 study, researchers from the Stockholm Resilience Centre and the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies concluded that the campaign represented a “mental tipping point” for the public, in which the earlier perception of a pristine reef shifted into a growing awareness that the ecosystem was approaching a critical point of no return. This shift in thinking led to a more integrated view of humans and nature, based on active and flexible stewardship of marine ecosystems for human wellbeing. The bottom line, according to our science peers, was that laws alone can’t bring about the changes necessary to protect the world’s ecosystems. Good science and public support are also vital.

MEASURE, MEASURE, MEASURE

What we don’t understand, we ignore. What we don’t measure, we don’t manage. For the past 30 years or so, ignoring environmental risks has worked out quite well for us. We saw few if any signs of the social–environmental turbulence now playing out at the global scale. But those days are over. It’s time to open our eyes. We must both measure and understand what’s happening to Earth.

We believe this to be a key step in the mind-shift required to reconnect with the biosphere. We must measure every aspect of how nature interacts with societies and track changes in the stability of the Earth system in real time. The architecture for this effort already exists in many places. Scientists and agencies around the world have established a Global Earth Observation System of Systems (GEOSS) covering many of the key planetary boundary processes, from changes in the climate to the chemical composition of the oceans. Earth-observing satellites monitor changes in sea level, and a global mesh of floating Argo buoys report continuously on shifts in temperature and acidity in our oceans, among other things.

We understand much better now how Earth operates. Yet there are still frustratingly large gaps in our knowledge. Data on the pace and global distribution of sea level rise, for example, remains incomplete and uncertain. So does information about the energy exchange between oceans and atmosphere in the global ocean conveyor belt; the global rate of biodiversity loss; actual melt of ice sheets in Antarctica, the Arctic, and Greenland; cloud dynamics and local shifts in rainfall as a result of global changes in weather patterns; and the importance of air pollution for the global climate. To put it simply, we need to measure, measure, measure, not to get certainty, but to understand risk and become cleverer stewards of nature for our own benefit.

A key priority is to track biodiversity loss. Why? Because biodiversity plays such a critical role in the resilience of ecosystems. There are still major gaps in our knowledge about species richness in the world. We’re losing massive amounts of biodiversity without ever knowing what we are losing.

But measuring alone won’t be enough. We must also share with the public our knowledge of how Earth works and changes, showing how it affects and changes our societies. This will require a deeper integration between natural sciences and social sciences. Luckily there is a growing momentum around the world at high-quality research institutions to address the interconnected links between humans and nature. And great things are happening here, such as the launch of Future Earth, the world’s largest international science endeavor on Earth system research for global sustainability. Future Earth aims to foster new knowledge to support a transformation to global sustainability with stakeholders outside of science.

We also need to connect the dots between observations, understanding, and society. Here we have a big gap. We still live in a world with islands of insight in an ocean of ignorance on both the risks and opportunities in a sustainable world. We believe the public’s lack of awareness about the global risks we face is largely due to the shortage of user-friendly, attractive, and widely accessible information, and that new scientific insights advance so fast that educational systems can’t keep up. That makes education our number one priority. If every secondary school classroom in the world were to tear down its geological charts and replace them with one that includes the Anthropocene, we would already have come a long way. We need new curricula for high schools and undergraduate programs at universities. Above all, we need to train a new generation of economists who understand that generating wellbeing for society means keeping the economy within planetary boundaries. As Kate Raworth at Oxford University has pointed out, if every student studying economics would start his or her program learning about planetary boundaries, the world would look different.

The environmental agenda deserves to be elevated from its “second-rate” position in politics and business. This is already gradually happening. In the global risk reports in recent years by the World Economic Forum, leading executives put global environmental risks near the top of the things they worry about, both in terms of their likelihood of occurring and in terms of the seriousness of the consequences for their businesses. Among the threats they identified were water supply crises, food shortages, extreme volatility in energy and agriculture prices, rising greenhouse gas emissions, and failure to adapt to climate change. Other threats mentioned were terrorism, chronic fiscal imbalances, and severe income disparities. This tells us something about the rapidly changing risk landscape. As these executives realize, we’re living in an increasingly turbulent world where social and ecological crises are not only equally likely, they’re also interconnected, potentially interacting and reinforcing one another.

When environmental risks are properly understood, that is, they become security risks, stability risks, foreign policy risks, financial and business risks. Developing a strategy to manage environmental problems becomes a question of risk management. Compare that to what we see in global markets today. The only risks markets appear to be interested in, officially at least, are economic ones. The possibility that businesses could lose market shares and profit margins is taken so seriously that companies on the stock market provide quarterly reports on their performance.

To us, this seems shortsighted. By fixating on short-term profit, businesses ignore long-term growth of social–ecological welfare.

For that reason, we think it would be a good idea to phase out quarterly financial reports, and replace them with bi-annual ones, or replace the current system with quarterly reports on how well businesses are doing in meeting targets aimed at staying within safe planetary boundaries. These should include accounting for carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, water use, and other impacts on ecosystem services. (Advanced tools already exist for this, such as the Corporate Ecosystem Services Review, developed by the World Resources Institute.) A natural evolution of such a business reconnection to the biosphere would be to see “state of the planet” pages next to the business pages in our daily newspapers and news programs. Imagine if there were Earth pages next to the financial pages in the Wall Street Journal, presenting quarterly reports on greenhouse gas emissions and use of ecosystem services among the largest companies in the world.

Finally, we believe grand experiments are needed to share knowledge with society at large. One idea would be to develop a global network of Earth Situation Rooms—physical or virtual—where citizens across the world could follow, in real time, what’s happening to the planet. Picture a wide circular room, surrounded by large video screens connected to the world’s most advanced Earth-observing satellites and monitoring systems. Here, in one place, citizens could catch up, in real time, on the environmental state of the planet, as well as regional trends, with respect to all of the planetary boundaries and key biomes.

Figure 7.2 A Safe and Just Space for Humanity. If there is a biophysical ceiling for human development on Earth—the planetary boundaries—then there must be a social floor, as pointed out by Kate Raworth, then at Oxfam, now at Oxford University. The social floor should consist of the universal human rights of access to resources, ecosystems, atmospheric space, a stable climate, and the dimensions of equity, dignity, resilience, and agency that are associated with a good life.

It might seem paradoxical in this epoch of escalating threats to the planet that we should put such a strong emphasis on preserving the beauty of nature at the local scale, or that we should lobby on behalf of the diversity of landscapes, or that we should urge local actions by individuals, communities, and other sectors. But it all starts where we stand. As Mahatma Gandhi is said to have advised, you must “be the change you want to see in the world.” That means we must build from the “bottom up”, whether we’re trying to save the jaguar in Latin America, the wolf in the Nordic countries, or the tiger in South Asia; whether we’re trying to secure freshwater supplies for a village in India, or plant a field with millet seeds outside a small village in Niger.

It no longer makes sense to us, in fact, to keep talking about a “global commons” or about economic “externalities.” These terms for the complex environment “out there” were developed for the old paradigm, where humans and nature were seen as separate entities. Today, in our big world on a small planet, we’re all part of the same commons, and changes in our shared environment—such as the climate system, the ozone layer, or the global hydrological cycle—rebound directly on local economies. In today’s interconnected and environmentally saturated world, there are no externalities. Everything, from finite resources to clean air, forms an integral part of our efforts to generate human wellbeing.

That’s why we say there aren’t any global commons any more. Because of the feedbacks generated by the Earth system as we push environmental processes too far, every part of our surroundings has become a personal responsibility for each one of us. A global commons is something that no one owns, and therefore is poorly managed. In the Anthropocene we all “own” every bit of the global commons and have a responsibility for them—because their fate will determine our future.

The Milky Way photographed from Cameroon.

Plantations in Sarawak have replaced diverse, resilient rainforest with monoculture palm oil trees, creating short-term benefits but uncertain returns when subject to shocks.