ONE

THE SMELLS OF SICK CITIES

AS HE DESCENDED INTO THE CELLAR APARTMENT, DR. JOHN HOSKINS Griscom covered his nose. This instinct was partly a reflex to the change in the air and partly a response to the many basements he had already visited. He expected the blast of stench that made him gasp for breath, just as he expected the pitch black that momentarily blinded him and the broken floor that tripped him. Yet knowing the conditions that awaited him made them no easier to endure. Griscom could not breathe.

His eyes adjusted to the darkness and Griscom’s heart went out to the poor patient, huddled on a makeshift bed of rags. Griscom ministered to this sufferer with little hope for her recovery. She did not have to die, but her basement room made it impossible to get the fresh air and sunshine that Griscom and other physicians knew a body desperately needed.1

Griscom served as the city inspector, or chief medical officer, of New York City in 1842 and 1843. During his tenure, Griscom daily encountered the ill health of urban residents and counted caskets into the thousands, but he lacked the political and regulatory power to eradicate the conditions that he blamed for sickening and killing his patients. Physicians similarly documented harmful sanitary conditions and agitated for public health reform in American and European cities. As they lashed out against governmental neglect of sanitary conditions, urban sanitarians built a public health movement upon common knowledge of fresh air and foul odors.

Physicians invoked the universality of olfaction to push for public health reform. As New York’s Griscom, Providence’s Edwin Snow, and Edward H. Barton of New Orleans conducted sanitary surveys of their cities, they charted many places where foul odors existed and threatened health. By pairing health dangers that city residents already smelled with newly calculated death rates that few knew, sanitarians argued that cities were unnaturally and unnecessarily dangerous. These sanitarians and their colleagues envisioned healthy cities as municipalities with active governments that empowered physicians to regulate the environment, to ensure ample fresh air, and to keep foul odors in check. As they vied for political power and authority over the city, physicians charted the sources of foul odors and locations of compromised air in a series of sanitary surveys that simultaneously reminded everyone about the health dangers they inhaled, spread new medical knowledge, and recorded ongoing environmental damage.

In the writings of antebellum health reformers, foul odors were not a symptom of unhealthy environments, as we think of them today, but the cause of illness. Because foul odors emanated from filth, historians writing after germ theory—including the sanitarians who lived through the paradigm shift of germ theory’s introduction—have construed filth rather than smell as the real danger of unhealthy environments. Changing the emphasis to filth obscures the original logic of sanitarians, who removed filth in order to eliminate stenches or, more often, sought methods for eliminating stenches without disturbing the filth that released the odors.

THE CITY THAT HAD BEEN HEALTHY

As he looked back from the 1840s, Griscom remembered growing up in a city where fresh air abounded, but New York City had been different then. In the 1810s, New York had been much smaller and less crowded; there was more room to breathe. Images of the city juxtaposed prominent buildings with bucolic surroundings, as the countryside was never far away. New York’s population of 96,373 had concentrated on the southern end of the island; Manhattan’s northern reaches were still a sparsely settled tangle of trees, creeks, and open spaces in the 1810s. Griscom believed that the air was refreshed and its healthful properties restored as it moved across these unsettled spaces, meaning that each breeze conveyed fresh air into the smaller city of his youth.

Confident that the countryside and its healthful benefits were within easy reach, New York’s leaders felt no need to preserve open spaces for health as they planned for economic and urban growth. The commissioners of New York City’s famous grid included few squares, parks, or open spaces in their 1811 plan, even as Europeans fought to preserve urban parks as necessary for health. Just three years earlier, Britain’s Parliament had rejected a proposal to build houses in Hyde Park because parks were “the lungs of London,” literal breathing spaces where residents went “to get a little fresh air.” In contrast, New York’s early planners explained that they set aside “so few vacant spaces … and those so small, for the benefit of fresh air” because New York had natural benefits that European cities lacked. Whereas the inland locations and narrow streets of London and Paris prohibited breezes from entering the cities’ centers, New York had “two arms of the sea,” the Hudson and East Rivers, that the commissioners trusted would channel ample fresh air from the ocean into the wide and regular streets of the grid. In essence, New York’s early urban planners, unable to foresee the tall buildings that would someday block river breezes from the heart of the island, believed that Manhattan’s coastal location would keep New York healthy.2

Medical geography and medical topography confirmed the grid commissioners’ belief in the natural healthfulness of Manhattan. These closely related fields of medical and scientific knowledge conceptualized health as a relationship between bodies and their local environs, correlating healthfulness and illnesses with geographical position and topographical features. These studies, the product of observation and physical experiences, led to the insight that higher elevations were often healthy, a theory that made Manhattan’s heights beneficial. Conversely, physicians and scientists believed that proximity to marshy areas, with their scents of putrefaction, would weaken and kill, so Americans tried to avoid swamps and wetlands.3

Medical geography taught Griscom, as it had the grid commissioners, that New York City had many natural advantages for health. Griscom summarized these lessons for his readers: “In geographical position, in climatic placement, and in geological structure, no site perhaps could be selected for all the purposes of a great city, of a more salubrious character, than Manhattan Island.” Sanitarians believed that the island benefited from a temperate climate and the two large rivers that flushed its shores, carrying wastes out to sea. Urban boosters and physicians praised Manhattan’s location near the ocean, which “insured sunlight and sea breezes,” but inland enough that plants “supplied to its atmosphere the life-giving virtues” of oxygen. Similar assertions of Manhattan’s natural healthfulness appeared in popular newspapers and medical writings of the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s, despite rising mortality rates. Sanitarians agreed that in an area with so many natural advantages for health, high death rates and frequent illnesses were unnatural or human-made. In other words, sanitarians were identifying environmental damage when they documented unhealthy conditions in the city.4

Unhealthy conditions were largely a product of population growth, which had come quickly both to New York City and the nation. As a teenager in the 1820s, Griscom witnessed the opening of the Erie Canal after eight years of construction and the sudden transformation of New York City from one of many seaports to the major entrepôt of the Northeast. Businessmen across the city rejoiced, as did the farmers upstate and throughout the Great Lakes region who now had easier, cheaper, and faster connections to markets in the city and overseas. Materials flooded the city markets and docks, and new industries took hold in Manhattan.

As prosperity reigned, migrants flocked to the city, arriving from rural areas and overseas to take part in the economic boom. The city ballooned from 60,000 inhabitants in 1800 to over 300,000 in 1840. Another 200,000 swelled the population in the 1840s, as the devastation of the Irish potato famine and the revolutions of 1848 displaced Europeans to the United States’ shores. The city would have grown even more if so many of its new residents hadn’t died; mortality rates in these decades ranged from twenty-four to more than fifty per thousand. While Griscom was city inspector, he was alarmed to see that total deaths, rather than declining, approached the peak death numbers of 1832, the most recent cholera year. Endemic respiratory diseases, led overwhelmingly by tuberculosis, had become just as deadly as a cholera epidemic. The dead were quickly replaced by new arrivals, many of whom would themselves sicken while “liv[ing] out their brief lives in tainted and unwholesome atmospheres.” The fate of Griscom’s cellar patient was far too common.5

ENCOUNTERING FRESH AND FOUL AIR IN NEW YORK CITY

Griscom emphasized tainted and unwholesome atmospheres because these were immediately obvious to his readers regardless of their background or education. Medical training did not convey the ability to evaluate air quality; the sense of smell did. Griscom called upon the universality of olfaction to argue that everyone, including the aldermen who had rejected his public health recommendations, knew that cities were unhealthy: “Every city resident who takes a stroll in the country, can testify to the difference between the atmospheres of the two situations:—the contrast of our out-door (to say nothing of in-door) atmosphere, loaded with the animal and vegetable exhalations of our streets, yards, sinks, and cellars—and the air of the mountains, rivers, and grassy plains, needs no epicurean lungs to detect it.” One might need specialized knowledge to evaluate other urban ills, such as the effects of drunkenness or vice that other social reformers targeted, but anyone could identify the tainted atmospheres that harmed health. They could smell the danger. By emphasizing olfaction, Griscom dared his readers to evaluate the stinking city environs they smelled as healthy.6

When Griscom touted “the air of mountains, rivers and grassy plains” as the opposite of tainted urban atmospheres, he was defining fresh air as the product of open spaces and constant, unrestrained movement. These ideas about fresh air were neither new nor unique to Griscom but stretched back to William Harvey’s 1628 publication De motu cordis. Harvey explained that the heart pumped blood, received from the veins, throughout the arteries of the body. The discovery of circulation revolutionized ideas of health. The ancient Greek physician Galen had defined health as balance between four humors that existed both in bodies and in the natural world, making ill health the consequence of imbalance. Harvey’s scientific discoveries and subsequent studies of bodily systems added an emphasis on free and open circulation to the idea of balance. In the eighteenth century, popular medical advice stipulated that “the first care, in building cities, is to make them airy and well perflated,” meaning that breezes must be able to blow through. Comments such as this one indicate that scientific beliefs about the importance of circulation shaped theories of urban space and public health.7

Eighteenth-century ideas about climate change further contributed to the beliefs that healthful fresh air was rural, and city atmospheres required special attention. As they cleared forests, cultivated fields, and introduced European agricultural methods to the North American continent, colonists and Europeans observed that the harsh seasons they had originally encountered were becoming more moderate. Writers interpreted these changes as evidence that cultivation was tempering the extremes of North America’s climate and predicted that expansion would continue this trend. However, deadly epidemics of yellow fever decimated the new nation’s capital city of Philadelphia in 1793 and again in 1798, leading physicians and citizens to doubt that development improved the climate. Benjamin Rush, one of Philadelphia’s leading physicians, blamed the epidemic on the stench emitted by a rotting pile of coffee beans. Rush further argued that deforestation on the outskirts of Philadelphia had enabled miasmas to flow into the city from nearby marshes and swamps. Though none of them knew that mosquitoes spread yellow fever, many of Rush’s peers challenged his ideas about the origin of the disease. Nonetheless, Philadelphia’s physicians and citizens agreed with the assessment that something had changed the city’s air. As a consequence, Americans started to worry about the air quality of local environs, especially in densely populated cities.8

Although everyone recognized fresh air as healthy, the scientists and physicians who had been working for decades to understand respiration now believed that the air one breathed determined one’s health or illness. The chemical theories of Joseph Black, Joseph Priestley, and Antoine Lavoisier taught Griscom and his peers that respiration purified blood as it flowed across the lungs, a discovery that made air quality imperative to health. Griscom was sharing modern scientific knowledge when he called fresh air a “powerful stimulant” and “nutrient substance.” He explained that “air, when pure, gives a freshness and vigor, a tone to the nervous and muscular parts of the system, productive of the highest degree of mental and physical enjoyment.” Griscom’s logic led him to conclude that the absence of fresh air made people ill, despondent, and prone to vices. Intemperance and tobacco particularly worried Griscom, a Quaker who was active in antebellum reform movements, and he thought that both these urban vices were directly traceable to the absence of fresh air.9

In discovering that respiration purified the blood, scientists also learned that regular breathing fouled the air by changing its chemical composition. David Boswell Reid, the Englishman who had ventilated the new houses of Parliament and established himself as a respiration expert, wrote that air’s interaction with blood was “a never-ceasing circle of chemical changes” that required the free movement of air as well as blood. When the air was fresh, each inhalation provided the blood with oxygen, then called “vital air,” and every exhalation cast out moisture and “carbonic acid gas,” a compound of oxygen with carbon and any impurities in the blood that “vitiated” or ruined the air. Nineteenth-century physicians and biologists believed that carbonic acid gas, better known today as carbon dioxide, was the chief poison and main hazard in respired air.10

Carbon dioxide smells unpleasant at high concentrations, which explains why Griscom and his peers could smell vitiated air. Griscom alleged that impure atmospheres had a “disagreeable odor,” which indicated that the air was “not proper to be breathed.” The chemists who worked with carbonic acid gas agreed that it smelled badly and was unhealthy; in 1850, Edinburgh chemist George Wilson defined carbonic acid as “a colorless, invisible gas, having a peculiar sharp, but not sour odour and taste,” and “poison” to breathe. New York physician and health reformer Elisha Harris wrote that ancient civilizations had also suffered from vitiated air and thus employed “pungent or agreeable perfumes” to deodorize “the offensive, stagnant atmosphere of unventilated apartments.” In 1857, London health officer and chemist Dr. Henry Letheby was disturbed by the “peculiar, fusty and sickening smell” of tenement apartments and ran a series of tests on tenement air. Letheby hoped to discover if the air contained “some peculiar product of decomposition to which might be attributed its foul odor and its rare power of engendering disease.” The only peculiarity Letheby found was an imbalance in the air’s constituent gases: oxygen was absent, and the room held three times the usual amount of carbonic acid. When they talked about the air as stale, respired, vitiated, tainted, or full of carbonic acid, physicians were talking about air that smelled badly.11

FIGURE 1.1. “Fixed Air” illustrates uneven knowledge about vitiated, or “fixed,” air. The man at the window knows the dangers of vitiated air and worries that Bob has been sleeping in the room with the window closed for too long. He warns Bob that the room is full of fixed air, but Bob, unaware of the new beliefs about respiration and health, misunderstands and protests that it does not concern him because “I did’n’t fix it.” David Claypoole Johnston, Scraps (Boston: D. C. Johnston, 1830), 3. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

To illustrate the health dangers of breathing vitiated air, Griscom recounted everyone’s nightmare scenario, the “Black Hole of Calcutta.” In June 1756, Siraj ud-Daulah, the nawab of Bengal, had allegedly imprisoned 146 English soldiers and allies for one night. In the morning, only 23 emerged, the rest having expired in the hot, cramped cell as they beseeched their guards for water and fought for space near the window. Experts on respiration and ventilation attributed these deaths to “the large volume of carbonic acid gas emitted from their lungs.” The dungeon room was small, designed to hold two or three men, and had only a few vents for air. When Griscom narrated the incident, he calculated the dungeon’s capacity at “not more than four or five thousand cubic feet of air,” far less than the “three hundred cubic feet” that ventilation experts deemed necessary for a single person’s safe respiration. According to these calculations, the dead men had suffocated on their own exhalations, which their bodies had filled with deadly carbonic acid. Griscom also reported that the health of those who lived until morning was impaired: many suffered from a typhus-like fever, probably caused by breathing “a highly concentrated dose of the ammoniacal effluvia arising from the putrifying [sic] exhalations” of their comrades’ lifeless bodies. Griscom feared that overcrowded and unventilated buildings would become the black holes of New York.12

While he was city inspector, Griscom experienced foul-smelling, vitiated air throughout New York City and concluded that radical changes in city government were necessary to improve the air and protect residents’ health. He suggested that city aldermen appoint medically trained men, rather than their friends and supporters, to the positions of the Internal Health Police, which included the office of city inspector as well as eighteen health wardens. A Health Police composed of trained doctors who understood health threats and disease etiology would be a marked improvement over the spoils system, in which the appointed officers lacked the knowledge and fortitude to protect the city’s health; many spoils-appointed health officers fled the city at the first rumor of disease. Although the mayor endorsed Griscom’s recommendations, the Board of Aldermen dismissed his suggestions. Then the election of a new administration ousted Griscom from office, and the city’s government continued as before.

Rather than accept these defeats, Griscom responded with a reformer’s zeal and called upon New Yorkers’ common knowledge of the air they breathed to rally popular support for public health reform. In the heat of August 1844, Griscom wrote the first sanitary survey of New York City while the sights and smells of crowded tenements and cellar apartments were “fresh upon [his] senses.” To publicize his concerns and the recommendations that city leaders had dismissed, Griscom invited readers to join him on a tour of New York City that went behind closed doors and entered homes, to see and smell the miseries of the city’s overlooked laborers. Part exposé, part medical treatise, and part reform tract, this sanitary survey simultaneously documented unhealthy living conditions and reminded readers of what they knew and what science validated: health or sickness resulted from inhaling fresh air or foul odors. Griscom concluded that the absence of fresh air was the chief cause of New Yorkers’ ill health, and he dedicated his lifelong campaign for public health to ventilating the city.13

Over the next thirty years, Griscom repeatedly insisted that New York’s poorest residents suffocated in foul air, and thus they died. Griscom was not alone in this conclusion, but he was dogged, publishing The Uses and Abuses of Air in 1848, regularly participating in sanitary surveys, and corresponding with colleagues across the country about public health. In the 1840s and 1850s, physicians and sanitarians across the United States joined Griscom in condemning foul odors and celebrating fresh air to build a reform movement for public health.

BUILDING PUBLIC PARKS, BUILDING FRESH AIR

While pushing for political reform that would institutionalize public health, Griscom also advocated more immediate changes to the built environment. In his survey, Griscom documented how New Yorkers had built a city of closely packed, poorly ventilated buildings that sickened them, and he argued that they could also build the solution, ventilation. Fresh air was absent from cellar apartments, narrow alleys, and tightly sealed rooms, but it abounded at the edges of the city. Griscom urged residents to overcome the shortcomings of their environs and make provisions to introduce air, the “life-giving, ethereal, and invisible fluid,” into city homes and buildings.14

To encourage funding for public parks as “urban lungs” that would provide fresh air to everyone, Griscom touted New Yorkers’ extraordinary efforts to secure fresh water. City governments had long recognized the importance of fresh water for health. Politicians and businessmen approved of and constructed expensive, complex systems that conquered distance and elevation to carry fresh water from countryside lakes and ponds into the heart of cities. Engineers were increasingly taking control of water in the nineteenth century; in addition to building canals and water systems, they moved rivers underground, constructed sewers, and pumped water in and out of individual houses. After the devastating yellow fever epidemics of 1793 and 1798, Philadelphia had erected the nation’s first comprehensive water system in 1801. Boston began work on its own water system in 1825, its goals being to prevent a catastrophic fire and provide soft water to homes throughout the city. Fresh water had also been scarce in Manhattan until New Yorkers came together in support of the Croton Aqueduct and Reservoir, a water-supply system that carried fresh water into the city from forty-one miles away and, like the grid and Erie Canal, set the stage for further population growth. The water system’s engineering was impressive and its expense enormous: New York City spent $15 million between 1837 and 1842.15

Griscom thought it ironic and shortsighted that city residents had spent so much to secure fresh water but did nothing to introduce fresh air into city homes and buildings. Though upper-class New Yorkers had begun building private parks in the 1830s, these exclusionary spaces were expensive and benefited few. Griscom began his public lectures and publications with the contrast between water and air expenditures, and he emphasized it in private letters as well. Others would echo these sentiments on the economics of fresh air throughout the century.16

Though neither a physician nor a reformer, Andrew Jackson Downing also worried about Americans’ health. After a European sojourn, Downing thought that Americans were “pale and sickly,” a sharp contrast to the robust and healthy bodies he had seen everywhere on the continent. As editor of the Horticulturalist and a leading authority on fashion and taste, Downing had no reason to frequent the dispensary or visit cellar apartments, but he saw the same dangers of vitiated air in middle- and upper-class homes. Downing condemned heated but unventilated rooms, declaring that stoves were “the favorite poison of America,” whose hot iron he thought released arsenic and sulfur vapors. Americans shut their windows and sealed their doors to protect the warmth of their rooms and save money on fuel, but ventilation advocates worried that these practices effectively contained and concentrated poisonous vapors, respired air, and bodily effluvia. Downing noted that Americans preferred “the continual atmosphere of close stoves” to deep breaths of “that blessed air, bestowed by kind Providence as an elixir of life,” and that their health suffered for it.17

This preference for heat over fresh air perplexed Downing, who thought back to the hues of health and vigor he had seen in the parks and gardens of European cities. As a horticulturalist, Downing had taken a keen interest in these spaces. He had marveled at the rare plants, hothouses, hardy shrubs, and trees at London’s Kew Gardens. He had inhaled the fragrance of two-hundred-year-old orange trees in Paris’s Garden of the Tuileries. In Vienna, Munich, and even industrial Frankfurt, he had found the loveliest plants and shrubs planted for the people’s enjoyment. Downing concluded that these public parks, where citizens from all social levels enjoyed fresh air and exercise, were indispensable to good health. New York’s problem, Downing realized, was that the city had no public parks, no “breathing zones” of its own.18

Historians have emphasized refinement, social control, and property values as incentives for America’s first urban parks, but fresh air and public health were also on the minds of park advocates. As early as 1848, Downing advocated public parks and gardens as “salubrious and wholesome breathing places” where urban residents would “exercise in the pure open air.” Downing supported Mayor Ambrose Kingsland’s 1851 proposal for People’s Park (known today as Central Park), arguing that a large urban park would be “a breathing zone, and healthful place for exercise.” Additionally, a park would bring “the perfume and freshness of nature” into the foul-smelling city. Though Downing undoubtedly saw the plan for a large urban park as another marker of Americans’ improving “popular taste,” his emphasis on the health and respiratory benefits of the park was consistent with his laments about foul domestic air. If unhealthy air harmed bodies in small spaces, Downing thought, then unbounded fresh air could do the reverse in a capacious space that brought the benefits of the countryside into the city.19

Griscom supported city parks but did not share Downing’s ardor for Mayor Kingsland’s plan. While Downing thought the spacious park would be a welcome breathing space, Griscom argued in the New York Times that giving residents an hour in a park and twenty-three in the vitiated air of their apartments “is like administering one grain of antidote for a pound of poison.” No matter how large or grand, a park could not offset the “stifling vapors, and … poisonous gases” of cellar apartments and overflowing tenements. Because Griscom believed that fresh-air problems were gravest within domiciles, he thought changes to the ventilation of individual buildings and the provision of greater space between buildings were the best ways to improve urban health.20

Griscom and Downing agreed that parks were reservoirs of pure air in crowded cities, but they differed on how residents would access the resource. Pipes conveyed fresh water from the Croton Reservoir into homes throughout the city, but there was no infrastructure that could move the air. Remembering how urban Europeans frequented their public parks, Downing thought New Yorkers would go to the park for fresh air and thus improve their health. But Griscom, aware of the airless homes and limited time of urban laborers, thought that cities needed to bring fresh air to residents in their homes. Griscom argued that the benefits of a “reservoir of pure air, as a means of ventilating its neighborhood,” would extend fewer than a thousand feet from the park’s edge, and he therefore proposed the dispersal of small fifty- or one-hundred-acre parks across the city as better for urban ventilation. Such small, regularly spaced parks would benefit more urban residents than a single large park, but Griscom’s preference was that the time, space, and money invested in the idea of a grand park go instead to the construction of well-ventilated dwellings. When city leaders adopted the plan for People’s Park in 1853, Griscom lost his fight for the dispersal of fresh air in pockets across the city, but he continued to agitate for improvements to the built environment.21

MANUFACTURING MIASMA IN NEW ORLEANS

At the same time that Griscom published the first sanitary survey of New York, physician and sanitarian Edward H. Barton was conducting a similar examination of the environment and health of New Orleans. Like New York City, the southern port city was a commercial hub, but it lacked Manhattan’s supposed geographic advantages for health. Medical topography interpreted New Orleans’s bayou location as swampy, miasmatic, and unhealthy. In the city’s early years, the purported miasmas were not deadly; slow urban growth and a small population kept epidemics in check. When Louisiana became American territory in 1803, the port city began smelly cycles of population boom and epidemic bust accompanied by stagnant ponds that overflowed with the growing city’s putrid wastes. Thus, by the 1840s, many Americans thought of New Orleans as an epidemic city, where outbreaks of malaria, cholera, and yellow fever were annual occurrences. City leaders and urban boosters fought this reputation, claiming that New Orleans was a healthy place in spite of the marshy land and water that surrounded the delta city. Once new residents became “seasoned,” boosters claimed, they were virtually immune to disease.22

Barton upended the boosters’ positive image of New Orleans as healthy when he penned the annual report of the Board of Health in 1849, a document that compared New Orleans’s scant vital statistics with those of other cities. Barton worked from incomplete information, as the collection of vital statistics was new and unevenly practiced in the United States during the 1840s. While London and Paris published detailed reports that enumerated causes of death, American cities did not have any laws or systems to regularly collect the same information. As a result, American health officials worked with annual death reports but little else. In New York City, Griscom dismissed the annual reports as “useful for little more than to satisfy ordinary curiosity.” In Massachusetts, statistician Lemuel Shattuck collaborated with health reformer Dr. Edward Jarvis to push for the passage of the Massachusetts Registration Act of 1842, which created a uniform system of vital statistics collection and dissemination for the entire state. Though New Orleans’s annual death reports were incomplete and did not include causes of death, they enabled Barton to calculate the city’s ratio of mortality, a number “large enough to remove the scales from the eyes of error.” Barton’s charts and calculations revealed that New Orleans had the nation’s worst mortality rate and was the least healthy city in the United States.23

The numbers were shocking, but Barton argued that New Orleans’s leaders could improve mortality if they better understood its causes. Thus Barton explained the effects of a “damp, sickly city” on human health and suggested environmental improvements such as planting trees to provide “fresh air during the day and [absorb] noxious gases during the night.” Likewise, Barton advocated installing a system of sewerage that would carry the city’s wastes away from the streets and alleys; otherwise, these spaces became repositories of filth that festered in the heat and vitiated the city’s air. In order to improve public health, Barton asserted that urban leaders must “make a city approach the country in its vicinage, as to heat, ventilation, dryness and cleanliness, and all those conditions which conduce to purity of air.”24

Barton’s solutions might have been effective, but they were costly and rejected by city leaders who preferred to invest in projects that would benefit trade along the Mississippi and into the Gulf of Mexico. Yet Barton, like Griscom, was not deterred by rejection. When yellow fever struck the Crescent City with particular vehemence in 1853, killing approximately ten thousand, Barton accepted the city government’s commission to examine the sanitary conditions that had created the epidemic. Barton’s investigation was a thorough sanitary survey of New Orleans that totaled 542 pages of mortality calculations, detailed testimonies of firsthand experience with disease and the environment, and maps of the city’s sanitary conditions.

Physicians in the 1850s did not agree on the cause of yellow fever, which would be traced to mosquitoes later in the century, but Barton and his fellow investigators concurred that the fever had originated in New Orleans because of the interaction of “atmospheric and terrene causes,” medical language for the creation and diffusion of miasmas. Barton explained that all smells were dangerous: “whatever impairs the impurity of the atmosphere is pro tanto, for the time being, the miasm, or rather, the mal-aria.” While Barton acknowledged that the atmosphere itself was beyond human control, he asserted that urbanites could stop activities that tainted the air with bad smells. This certainty guided both Barton’s description of health-threatening sanitary conditions and his recommendations to prevent further epidemics.25

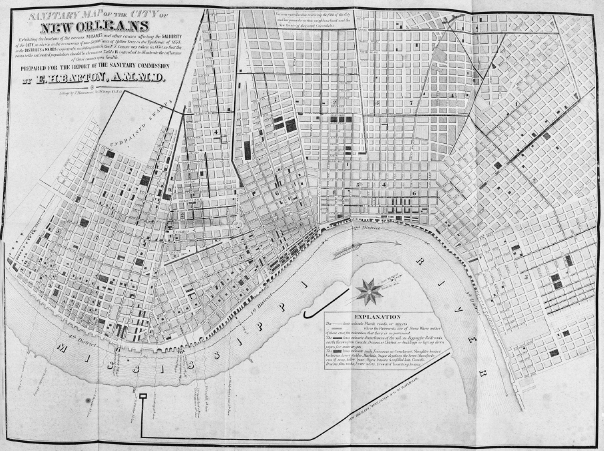

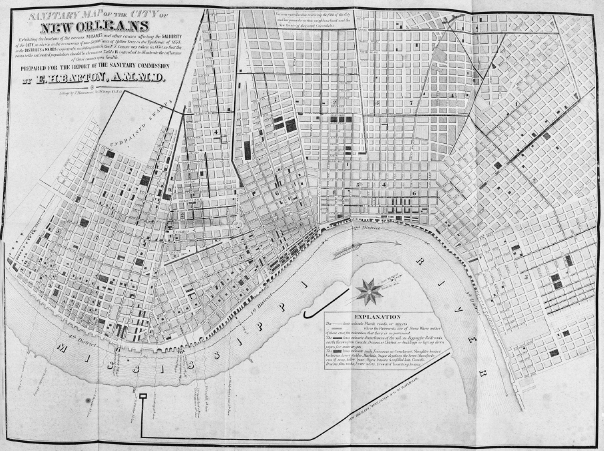

To impress the ubiquity of sanitary problems upon city leaders, Barton charted every dangerous interaction of land and air on a thorough sanitary map. While the heavily dotted map clearly displayed the prevalence of health threats, Barton’s detailed descriptions of the problematic interactions between atmosphere and earth emphasized the production of foul odors. In his words, “Fever has again been manufactured,” in all the places that created foul odors: “the filthy wharves and river banks have cast again their noisome odor to poison the atmosphere, and … the corrupted bilge water and filthy vessels from abroad, the dirty back yards and unfilled lots and overflowing privies.” The “various nuisances and other cases affecting the salubrity of the city” also included canals, railroads, and water and gas lines, as building these improvements for industrial and urban growth disturbed the damp soil of the delta and released fetid exhalations of marshland into the atmosphere. It was not just the existence of these noxious odors but their proximity to dwellings and residents’ inability to breathe fresh air that made New Orleans a sickly city. As he detailed the many ways in which urban growth and development created foul odors, and mapped the coincidence of internal improvements, nuisances, and deaths, Barton reinforced his main contention: “the fever originated with us.” In a conclusion that echoed Griscom’s criticism that New Yorkers built the city that sickened them, Barton asserted that urban growth and development manufactured disease whenever and wherever it created stenches.26

FIGURE 1.2. In his 1854 “Sanitary Map of the City of New Orleans,” physician Edward H. Barton noted the location of every city feature that produced foul odors. In addition to the undrained swamps, open drains, and filth-covered low ground noted on the margins of the map, the dark crosshatched blocks indicate the location of “such Nuisances as Cemetaries [sic], Slaughter houses, Vacheries, Livery stables, Markets, Sugar depots on the levee, Manufactories of soap, tallow, bone, Open basins & unfilled lots, Canals, Drains, Gas works, Fever nests, Crowded boarding houses.” The dark lines along streets indicate soil that had been disturbed for improvements such as railroads, canals, drains, ditches, water mains, and gas lines. Report of the Sanitary Commission of New Orleans on the Epidemic Yellow Fever of 1853 (New Orleans: Picayune Office, 1854), map S. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

Barton thought that city air was different from rural air, not only because of the high concentration of odors, but also because urban residents spent their time differently than those in rural areas. Whereas farmers spent most of their time in fields where they inhaled freely circulating fresh air, city residents and laborers spent “more than two thirds of [their] time … in the confined and … deteriorated atmosphere of houses and apartments.” Due to poor ventilation and overcrowding, “the atmosphere has to be breathed over and over again,” meaning that city residents inhaled vitiated air full of carbonic acid. The foul air of homes combined with the smells of the disturbed environment to create “a peculiar air” that “the more sensitive of our race easily perceive.” When supposedly sensitive children, women, and convalescents balked at the air of cities, they innately recoiled from miasma and disease.27

Smells defined both the problems Barton identified and the solutions he proposed. Barton suggested numerous regulations, practices, and technologies that would control or eliminate the creation of bad smells within city limits, thereby improving and protecting the urban atmosphere and the health of all who inhaled it. His first recommendation was the principle that “streets should, were it possible, run East and West and North and South, and always be at right angles, to prevent obstruction and permit perfect ventilation” of the city. The Massachusetts Sanitary Commission had made a similar recommendation in its 1850 sanitary survey, suggesting the preservation of open spaces and creation of wide streets to enable the circulation of air. Minister and lecturer Horace Bushnell echoed this principle, telling the Public Improvement Society of Hartford, Connecticut, that streets should be “laid diagonally in relation to the breeze” so that “the current would press into all the streets and into and through all the houses open to its passage, making eddies and whirls at every crossing, and fanning, as it were, by its breath, the whole city.” The wide boulevards and spacious parks of the City Beautiful movement were advocated at midcentury, not for aesthetics, but for fresh air and public health.28

These city planners thought freely moving air was fresh, and they similarly believed that stagnant air accumulated exhalations and odors of decay. Barton reasoned that, just as the city plan should allow air circulation, houses “should be so constructed as to promote the maximum of ventilation and the minimum of moisture and temperature,” changes that would keep the air moving and eliminate the heat and moisture that sped putrefaction and the generation of odors. Barton advocated the relocation of “slaughter-houses, soap, bone, candle manufactories, or others creating nuisances” away from any square containing fifty people or ten houses, thereby removing stench producers from the neighborhood of houses. He urged the city government to pave city streets, coordinate the removal of filth, require that all backyards and empty lots be paved with cement, and forbid improvement projects that would disturb the soil between May and October, the warmest and smelliest months of the year. Measures such as these would control the interaction between air and soil and inhibit the rapid decomposition that generated stenches and diseases in the heat of summer. Finally, Barton urged city leaders to close all cemeteries within city boundaries and forbid further interments, a recommendation specific to New Orleans’s environment and culture. Since swampy soil made burial impossible, residents had adopted burial practices that encased bodies in sepulchers and mausoleums aboveground, but these often leaked the gases of human decomposition.29

In addition to these specific and detailed recommendations, Barton’s primary solution reiterated Griscom’s rejected proposal for New York City: the creation of a Health Department, to be consulted by the city government on all situations that affected the health of the city. The three physicians who served as members of this department would not only advise the government but “have surveillance and control, over everything that may affect the salubrity of the city of New Orleans, or have a tendency to impair the same.” Among the department’s duties, Barton included inspections of “any place which it has reason to believe there may be a nursery of filth, impairing the purity of the air.” In other words, members of the Health Department would be smell detectives, officially charged with seeking out the sources of stenches in order to eliminate them. These physicians would police the air.30

New Orleans’s wealthy disagreed with Barton’s conclusions and preferred the logic of Dr. J. S. McFarlane to that of the sanitarians. In his analysis of the epidemic, McFarlane recounted how New Orleanians had, at great expense, paved streets and built brick sidewalks when they were told that unpaved streets and rotting wooden planks caused yellow fever. These expenditures had not prevented the epidemic; instead, citizens died on the very streets they had paved. Now sanitarians said that the stenches of filth and overcrowding caused yellow fever, and they urged the creation of a Health Department and the cleansing of every portion of the city. McFarlane argued against these measures, explaining that New York and Philadelphia were far filthier than New Orleans but undisturbed by yellow fever. In McFarlane’s view, creating a Health Department was a costly knee-jerk reaction to the high death rate that New Orleanians would come to rue. McFarlane conjured all-powerful inspectors who could enter any home at will and would regulate all aspects of the city, costing its citizens both money and freedom.31

Objections like McFarlane’s arose everywhere that reformers urged creating a standing health board or legislating for public health. New York’s industrialists feared intrusion and regulation as much as New Orleans’s capitalists did, but sanitarians made a compelling case every time they ranked cities by mortality rate and cataloged local stenches. As sanitarians improved the collection of vital statistics and conducted ever more thorough surveys of American cities, they began to sway newspaper editorials, public opinion, and political action toward governmental reform and greater control of the environment.

GOVERNMENT NEGLECT AND CHOLERA IN PROVIDENCE

When a cholera epidemic struck Providence, Rhode Island, in 1854, Dr. Edwin M. Snow was in a better position than either Barton in New Orleans or Griscom in New York. At Snow’s urging, Rhode Island had followed Massachusetts’s lead and passed a statewide registration law in 1852 that made the state an early adopter of health statistics collection. Providence’s city leaders had appointed Snow as city registrar, and thus Providence was the only American city to have a physician as its health officer when cholera returned to the United States. Snow’s collection of vital statistics during the epidemic yielded what he called “facts” and “lessons.” One of these facts was that deaths were concentrated in two small areas of the city. When Snow investigated the neighborhoods of the canal and Fox Point Hill, he found obvious lessons for disease prevention.32

Forty percent of Providence’s deaths had occurred near the canal, which everyone called a nuisance because of its stench. The entire neighborhood of the canal reeked from the decomposing cats, dogs, and hogs that bobbed in the discolored water. The canal also harbored the wastes of the printworks and released gases produced by decaying vegetation. Before cholera arrived, Providence’s aldermen had investigated the canal and declared it “a nuisance which may be abated, in part at least, by removing the sediment in the basin, where the stench is greatest.” Despite their pronouncement, the aldermen failed to enact any abatement measures. Snow pointed to the costs of this inaction, which had allowed the stenches to fester.33

Just as Barton attributed yellow fever to New Orleans’s air, Snow believed that cholera had its “mysterious cause” in the atmosphere. Though he could neither define nor identify this cause, which affected everyone alike, Snow interpreted the geographic concentration of deaths as meaning that certain areas of the city incubated the disease atmosphere. Snow thus argued that the stench-laden airs of the canal and Fox Point Hill fostered cholera.34

In contrast to the canal district, Fox Point Hill was an elevated area that had the geographic advantages of a constant harbor breeze and good drainage. Nevertheless, 30 percent of the cholera deaths had occurred in a small neighborhood atop the hill within the span of a few days. Snow investigated the area in person and was overcome by the stench of hogs. Ships and rails met at Fox Point, making this neighborhood a hub for trade and necessitating the many hogpens that Snow smelled. Just as the canal’s smell prevailed in its vicinity, the hogpens dominated the atmosphere of Fox Point Hill. Snow visited houses that were physically clean, but “the stench was so great as to create a feeling of nausea.” When they reported cholera deaths, several local doctors corroborated Snow’s experiences and noted that residents had closed their windows against the stench, a commonsense response that dangerously increased the concentration of vitiated air in their homes.35

FIGURE 1.3. This woodcut depicts a foul and unhealthy industrial canal like the one that Dr. Edwin M. Snow blamed for cholera in Providence. In the full image, wastes flow into the canal from a slaughterhouse and glue factory, a figure on the right is drowning cats in the canal, and dead animals bob in the water. The figure in the center foreground holds his nose because of the stench, though his companion is collecting water in a bucket. Lament of the Albany Brewers: After the Verdict in the Libel Case of Taylor vs. Delavan, broadside ca. 1840. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

In his report on the cholera epidemic, Snow spared no detail in blaming his employers, the city authorities, for the death toll. He and fellow physicians agreed that cholera had been aided by a local nuisance in each death. In addition to the canal and hogpens, life-ending stenches emanated from unclean privies, clogged street gutters, foul drains, stables, and piles of rotting garbage. These were nuisances, “such as the city authorities are responsible for, and it is their duty to remove them.” Snow’s question was an emphatic “Will they do it?”36

In 1858, Snow wrote to his colleague John Hoskins Griscom, explaining that Providence’s aldermen had finally acted: “I procured the passage of a law by which the board of health are authorized to remove the occupants and close any tenement which they consider unfit for occupation as a dwelling.” Snow then used this law to eliminate cellar apartments from Providence, though he reported doing so through “appeals to [the people’s] common sense … without a resort to legal process.” Though Snow led an annual spring inspection of all domiciles and served owners with notices for any nuisance he found, he did not have to enlist the courts to eliminate nuisances and improve health in Providence.37

TESTIMONIES OF STENCH AS TOOLS OF REFORM

Griscom read Snow’s account to a committee of New York state senators in 1858. In response to repeated petitions about the sanitary affairs of New York City, the state legislature had appointed five of its members to investigate complaints and report on what legislation “is requisite and necessary to increase the efficiency of [the health] department.” Griscom was the first to testify about the insanitary conditions of the city and how they could be alleviated or even eliminated by the creation of an active Health Department, staffed by physicians and armed with regulatory powers. Snow’s successes in Providence proved the efficacy of the latter, but Griscom also had to prove the danger of breathing in the city.38

To do this, Griscom guided the committee on a narrative tour of the city, explaining his experiences within poorer wards and cellar apartments much as he had in his 1842 survey. Griscom tried to share his visceral experiences by emphasizing the sensory aspects of the city, such as the choking stenches and blinding darkness, so that his audiences would virtually experience and evaluate city smells and health alongside him. He led his audience into the crowded tenements and down into the offensive cellars, so they could “feel the blast of foul air as it meets your face upon opening the door.” He brought concerned New Yorkers into the tiny sleeping rooms that had no ventilation, to inhale “the effluviae of the bodies and breaths of the persons sleeping” that generated an intolerable smell and an “atmosphere productive of the most offensive and malignant diseases.” For Griscom, the experience of entering these apartments and inhaling “the suffocating vapors of the sitting and sleeping rooms” was evidence enough that tenements and a poorly built city caused illness and death.39

To the listening senators, Griscom explained his visit to a single city block, located between First and Second Avenues between Thirty-Third and Thirty-Fourth Streets, where he had breathed an atmosphere “of the foulest kind, as the place cannot be visited by winds unless they blow down from over the tops of houses, and consequently there is a miasma continually filling up that great bowl.” Buildings crowded the street, leaving culs-de-sac where the yards met behind tenements. The houses were too tall to admit a current of air from the street, and the stagnant atmosphere quickly absorbed emanations from overflowing privies and undrained soil. Sloping streets further contaminated the atmosphere by funneling moisture into yards and basements, where refreshing rains became putrid, stagnant water. Nearly overcome, Griscom did not linger; he quickly concluded that the residents of this block had little hope for relief.40

Although the senators had read petitions from suffering citizens and the recent sanitary reports of the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, they scarcely believed Griscom’s descriptions. A horrified committee member asked, “Is there any other such locality?”

“Hundreds,” Griscom replied.41

Griscom suggested that the senators visit Oliver Street in the Fourth Ward and see for themselves how fourteen families crowded into the ten tiny rooms of a three-story building. Or they could go to Cherry Street, where they would find a tenement “of the better class” that held 120 families numbering five hundred people in its poorly ventilated rooms. If they entered any of the city’s cellar apartments, committee members would experience foul air and blinding darkness firsthand. Behind nearly any building, they could enter courtyards “so literally hemmed in, that [the air] remains in a state of almost complete stagnancy.” As the first to testify before this committee, Griscom explained that the stagnant air of unventilated tenements, dank cellar apartments, and filth-filled yards was hurting the health of the city.42

Impaired health was not limited to the poor, as high concentrations of carbonic acid could be found wherever men and women “separated for [their] own exclusive use, a small portion of the great atmospheric ocean” by building a house with solid walls and an impervious roof. To drive this point home, Griscom recounted one of his own experiences in the home of “a professional gentleman, residing at the corner of two of the most fashionable streets.” The builder of this stylish house had done his job well, fitting windows and doors almost exactly to their frames and thus preventing the circulation of air between inside and out. Two stoves warmed the front rooms on a frigid December evening when a charitable organization met there. Despite the education and refinement of the illustrious gentlemen within—numbering among them judges, physicians, merchants, and editors—they did not realize the danger of meeting in airtight rooms heated by stoves until it was almost too late. When the chair complained of the closeness of the room and tried to open a window, his peers cried out and warned him against “catching cold.” He persisted, only to have his committee members complain variously of great heat and intense cold, the result, Griscom explained, of deficient oxygen affecting their bodies differently. Griscom concluded, “Doubtless a good system of ventilation would have obviated the whole difficulty, and avoided evils for which neither the beautiful paintings, the costly furniture, nor the downy carpets, could compensate.”43

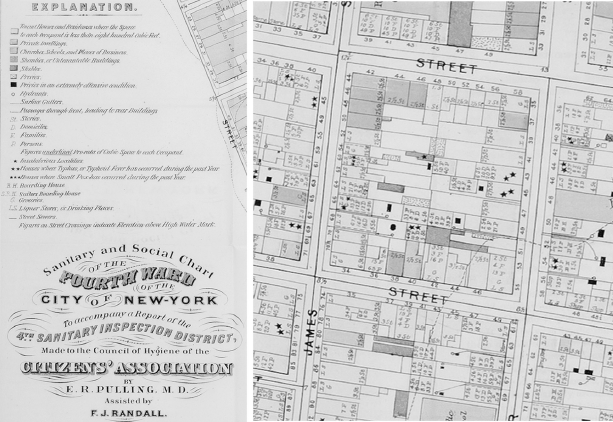

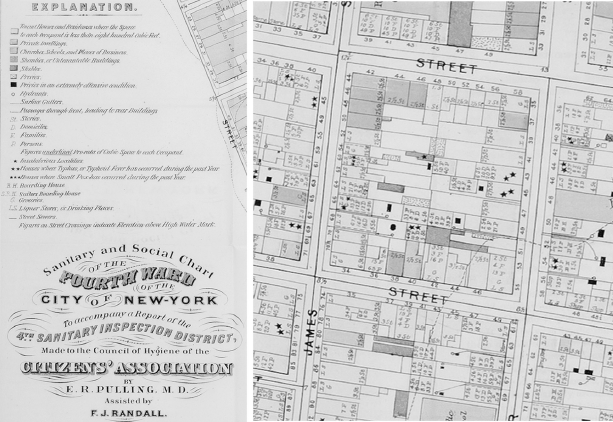

FIGURE 1.4. Dr. John Hoskins Griscom and other sanitarians interpreted culs-de-sac, the narrow spaces between tall buildings, as pools of stagnant, unhealthy air that could not be moved by a breeze and thus were never fresh. Report of the Council of Hygiene and Public Health of the Citizens’ Association of New York upon the Sanitary Condition of the City (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1865). Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

Other physicians concurred with Griscom, noting that stately homes suffered from foul odors just as cellar apartments did. When Griscom testified about “defective internal domiciliary arrangements” before the state senators, fellow doctor Joseph M. Smith interrupted. Smith shared his personal experience at a “respectable looking house in West Broadway,” which a running sewer had forced him to leave. Smith recalled “a most abominable stench pervaded the neighborhood for hours, and drove me from the place.”44

Smith’s decision to leave was a prudent one, as the experience of new president James Buchanan the year before had illustrated. When Buchanan arrived in Washington, DC, for his March inauguration, he stayed at the National Hotel and fell ill with scores of other guests. Newspapers across the country published stories about the mysterious sickness at the hotel, recounting episodes of listlessness, nausea, diarrhea, and at least one death. Recovery was slow and kept Buchanan from meeting with office seekers. Theories as to the cause of the illness abounded, including speculation that it had been an assassination attempt. When physicians investigated the hotel, they discovered that the sickness was “produced by the inhalation of a poisonous miasm, … which entered the hotel through the sewer.” The noses of city officials corroborated this explanation, as they documented “a peculiar and offensive odor [that] pervaded the premises.” The health officers, aided by a civil engineer, traced the foul air to a faulty and unventilated sewer connection in the hotel basement. These smell detectives explained that the heating system dispersed the “foetid gas” through the hotel, where it built up to unhealthy levels because the hotel lacked a ventilation system and every window was tightly shut against the bitter cold of March.45

Smell testimonies convinced the senators that many places, businesses, and buildings of the city fouled the air and harmed public health citywide. In its report to the state senate, the committee prefaced its recommendations with its genial goal “that the city of New York shall be secured in every part alike, in the means of preserving the public health; and that the blessings of light and sunshine, and pure air shall be equally enjoyed by all its people, under the wise provisions of suitable laws.” Through their references to the entire city, the senators acknowledged disparities in the geography of odors and health and accepted sanitarians’ argument that the government was responsible for eliminating these disparities. The senators recommended that the New York State Senate established a Board of Health independent of the city inspector’s office and composed solely of physicians. The committee concluded that this board should have responsibility for “whatever relates to the sanitary affairs of the city,” a capacious category that alarmed critics but thrilled sanitarians. Finally, they would be able to prevent disease in New York City, but the committee’s recommendations failed to secure enough votes. Political reform was, then as now, a painfully slow process.46

THE SANITARY SURVEY PERFECTED

The air of the entire city came into sharper focus in the 1860s, when the destruction of the Civil War draft riots prompted New York’s leading businessmen to pay closer attention to the lives and grievances of poor laborers. Leading citizens including Peter Cooper, Robert Roosevelt, and John Jacob Astor Jr. formed a Citizens’ Association to agitate for reforms that would improve public health. These leading citizens were familiar with Griscom’s exposés and adapted his method of combining personal experience, vital statistics, and the geography of the city. The Report of the Council of Hygiene and Public Health of the Citizens’ Association of New York upon the Sanitary Condition of the City documented the sanitary condition and health threats of New York City with a new level of detail and precision.47

In order to assemble a picture of the sanitary condition of the entire city, the Citizens’ Association broke the city into thirty-one sections and, adhering to Griscom’s call for trained professionals, enlisted physicians as “competent experts” to investigate every aspect of their assigned districts through “house-to-house visitation.” These men descended to the basements and smelled the blast of foul air that Griscom had first described two decades earlier. In their individual reports, the inspecting physicians detailed the sanitary conditions of individual buildings and blocks. They specified the addresses of the “most offensive odors” and of buildings whose ventilating provisions failed to admit enough fresh air for the inhabitants.48

What emerged from these thirty-one detailed reports was a citywide catalog of sanitarians’ concerns, from natural topography to the built environment and from soil drainage to aerial currents. The minute mapping of these concerns onto specific building addresses and street blocks redefined the geography of fresh air and foul odors. Where Griscom had focused on the bad air of individual apartments and buildings, the Citizens’ Association also documented the odors and emanations of entire blocks, squares, and neighborhoods. Ventilated buildings offered few advantages when the air of the neighborhood contained “the most nauseous odors,” “noxious gases,” and “insalubrious emanations.” Consequently, inspectors turned their attention to the accumulation of filth—including garbage, manure, sewage, and animal carcasses—not so much for its material presence or unsightliness, but because these nuisances “contaminate[d] the atmosphere of the locality.” As Edward H. Barton had in New Orleans, the physicians cited certain businesses for infecting the atmosphere and, when located in populous areas, classed these along with filth as nuisances “injurious to public health and to individual welfare.” Inspectors focused on the proximity of slaughterhouses, hide and fat depots, bone-boiling and fat-melting establishments, gas manufacturers, and manure yards to residential areas and crowded tenements. It was not the mere existence of these industries within the city that made them nuisances; it was the smells they released into the air that residents and visitors daily breathed.49

Chemists joined physicians in the sanitary survey, asserting their importance with the argument that “hygiene must rest on the basis of chemical investigation.” This assertion had long been true, as many of the measurements upon which Griscom evaluated fresh air and ventilation came from chemical research into the gaseous composition of air. Rather than relying on personal observation and maps, chemists could pinpoint health threats by analyzing aspects of the environment and measuring any impurities therein. Professors John W. Draper of New York University and R. Ogden Doremus of Bellevue Hospital reported on the hygienic applications of chemistry to the water, air, food, and soil of the city. The chemists advocated water analysis to test for impurities in the Croton Reservoir and local wells and the use of charcoal in sewer ventilators to absorb noxious gases. They concluded that the dangers of rotting and adulterated food were omnipresent but adequately addressed by “modern methods of analysis and examination.” Soil was best managed through street cleaning and sewerage. Air, like water and food, required analysis to determine its quality and the sources of impurities it carried. Though recent advances in gas analysis enabled the chemists to “offer legal evidences of sources of contamination by clearly identifying them,” a systematic examination of the city’s air would be “the most difficult and expensive of the inquiries thus recommended.” Chemistry could provide invaluable knowledge on the sanitary condition of the city and methods for improvement, but such knowledge came at a higher price than the commonsense solutions already available to sanitary reformers and urban residents.50

Sanitary inspectors returned to the addresses Griscom had been lamenting for years. At “Rotten Row,” a stretch of eight houses on Laurens Street, Griscom had inhaled a “pestiferous stench” that poisoned the atmosphere. Inspectors had little difficulty believing that cholera had first broken out in this spot, since they found that smallpox was a regular feature of life in those tenements. On Cherry Street, Griscom had found “imperfect ventilation and overcrowding” that weakened and sickened the five hundred residents of a single tenement. Revisiting Cherry Street, the Citizens’ Association’s inspector was horrified by the now-notorious “Gotham Court.” Dr. Ezra Pulling had inspected Gotham Court over the three preceding years, and he included three pages of building schematics that showed how grave the overcrowding had become in this “human packing-house.” Emanations from the basement privies could be perceived “as a distinct odor as high as the third floor.” The placement of doors on the same wall as windows made it “impossible for a current of air to pass through the rooms under any circumstances.” Though 49 of the 120 apartments were vacant when Pulling visited, there were still 504 occupants who inhaled and exhaled the building’s stagnant air. Pulling thought it a “misfortune to possess an acute sense of smell” in such crowded and unventilated quarters. Given these deficiencies, Pulling was unsurprised that 146, or 29 percent of the occupants, were ill when he visited.51

The sanitary deficiencies of Gotham Court were largely internal: privies in the basement that infected the air of rooms above, unventilated rooms whose air remained stagnant, and overcrowding that exhausted the tenement’s air through respiration. Pulling explained that these unhealthy conditions were fairly standard for tenements, but far worse was the mixture of internal and external sanitary problems that existed just a few blocks away, in a block between Cliff and Vandewater Streets. Here, tenements abutted stables, tanning vats, and an extensive soap and candle factory. Privy odors competed with “noxious gases” from the stables, the “peculiar stench” of green hides, and the “emanations” of soap and candle making, which “vitiate the atmosphere for a considerable space around.” Pulling concluded that residents of this district could not avoid breathing these many scents and therefore suffered “epidemic visitations” of typhus fever, smallpox, and scarlet fever.52

It was impossible for Pulling and other inspectors to share the experience of breathing such foul air with their audience, but they could and did use maps to show the conditions that created such an olfactory cocktail. These maps took Griscom’s geographic thinking to the next level; inspectors both indicated addresses in their narratives, as Griscom had, but also marked everything they observed and experienced on detailed maps of single blocks and the entire city. The published report included floor plans of individual buildings and plats of single blocks as well as civil engineer Egbert Viele’s topographical map of the entire island.

These maps presented familiar information in a new way, literally showing readers the invisible dangers of crowded buildings and blocks, where the air connected unsuspecting residents with churches, schools, offices, and stench-producing offensive trades. For the unhealthiest ward of the city, color coding helped make the sources of stenches stand out. In the Fourth Ward, the squalid home of Five Points, Gotham Court, and Rotten Row, yellow denoted the overcrowded tenements where vitiated air stifled residents, while proximity to brown and black meant that people inhaled the stenches of horse manure and privies overflowing with human waste. While businessmen and middle-class shoppers might not visit Five Points or Gotham Court, they certainly inhaled the air tainted by those spaces; blue-shaded churches, schools, and businesses were only one block from the highest concentration of yellow.53

FIGURE 1.5. In their sanitary survey of New York City, inspecting physicians included maps to show the proximity of businesses and residences to the sources of foul odors. This map of the congested Fourth Ward uses a combination of color coding, symbols, and notations of building size and population to explain the many and overlapping threats to air and health. Report of the Council of Hygiene and Public Health of the Citizens’ Association of New York upon the Sanitary Condition of the City (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1865). Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

The experiences of inspectors with contagious diseases made this proximity between unventilated tenements, overflowing privies, and businesses even more threatening. The buildings were static, but their inhabitants were constantly on the move. Inspector after inspector reported witnessing people circulating between fever-ridden tenements and the businesses on the next block: “no district or street in the city is free from the peril of exposure to the maladies here mentioned.” Children with visible pockmarks gathered “unrestrained, and apparently unnoticed,” near the entrances to stores and offices in their neighborhood, where they could spread smallpox to unsuspecting customers. The elegant mansions of Stuyvesant Square backed up against a row of typhus-filled tenements, whose residents undoubtedly shared the air they breathed with their wealthy neighbors. One inspector traced typhus from its origin in an Eleventh Ward tenement to the homes of family members scattered across the city: one in the Seventeenth Ward, another in Brooklyn, and cases on Avenue A, Sixteenth Street, and Eleventh Street. Another inspector connected seventeen cases of typhus in four distinct localities of the city to their “careless exposure” to a single source.54

In the hands of the Citizens’ Association, vital statistics and medical geography were changing to make, at long last, a compelling case for government protection of public health. Maps and charts concretized the dangers of living in the city and demanded government intervention that would address the city as a whole, an improvement over the private charities that worked piecemeal in specific blocks and neighborhoods. Confronted with the numbers, images, and maps of ill health on the heels of the Civil War and the worst riots the city had ever experienced, New York State’s legislature chartered the first standing health board composed of physicians in an American city in 1866.55

The sanitary surveys and reports of the 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s documented, in increasing detail, the confluence of environmental and human factors that generated stenches and, everyone believed, ill health. Vital statistics and detailed maps augmented and reinforced the lessons of personal experience with city environs. Surveys and reports spread the knowledge that American cities were unhealthy but could be improved by active governance in the form of physicians armed with regulatory power. Though sanitarians documented America’s cities in increasing detail, making urban environs more knowable and raising alarms about the proliferation of foul airs, public health reform was slow in coming.

It took the Civil War and the 1866 cholera epidemic to achieve the early sanitarians’ goals of making public health a regular governmental concern, staffing health committees with physicians and scientists, and strengthening the enforcement of sanitary regulations. While Griscom and his colleagues spent decades assembling experiential, quantitative, and cartographic evidence to push for change, urban residents suffered from the air they breathed. City dwellers knew the material conditions of ill health, because they smelled and saw them daily. Laborers descended into cellars, felt “the blast of foul air,” and inhaled “the suffocating vapor of the sitting and sleeping rooms.” Far from complacent victims, urban men and women harnessed personal experiences to protect their individual health.56