SIX

LEARNING TO SMELL AGAIN

Managing the Air between the Civil War and Germ Theory

IN SEPTEMBER 1873, THE SANITARIAN, A NEW MONTHLY JOURNAL dedicated to sanitary science and reform, mailed its sixth issue to subscribers. Nestled between articles that explained the appropriate methods of sea bathing and how to prevent cholera appeared a short paragraph titled simply “Disinfectants.” Without comment or elaboration, the paragraph quoted a student’s response to an exam asking how disinfectants worked: “They smell so badly that the people open the windows, and fresh air gets in.”1

The editors probably included this piece for some humorous relief from the long and serious articles about how to preserve and improve public health. One can easily imagine the bemused teacher smiling and shaking his head at the clever answer. However, readers of the Sanitarian recognized that the student, while evading the spirit of the question, was correct. The student’s answer emphasized the paradox of disinfectants—they worked, but the powerful odors of chemical disinfectants required open windows and thus ushered fresh air, one of nature’s disinfectants, into the room.

The student stood between two worlds that were quickly diverging after the Civil War, as new scientific knowledge disrupted the logic behind traditional practices. Journals such as the Sanitarian and Herald of Health tried to bridge these worlds by appealing to both medical and lay audiences, applying the most recent theories and discoveries of the laboratory to the lived spaces of city and home. The journals attracted interested lay readers who, like the student, blended long-standing practices of opening windows, positioning fragrant plants, and airing rooms with newer applications of chemical disinfectants to kill disease agents and ensure health through access to “fresh air,” an old friend whose definition was changing.

In their discussions of and practices for ensuring health in urban spaces, Americans began questioning miasma theory before germ theory was widely introduced, understood, or accepted. The experiments of chemist Louis Pasteur in France and physician Robert Koch in Germany increasingly proved that microbes caused the era’s deadliest diseases in the 1860s and 1870s, but the discovery of germs neither occurred overnight nor immediately changed ideas about health and illness. Instead of thinking of the turn from miasma to germ theory as a watershed moment that revolutionized medical practice and popular ideas about health, we might better see it as a turning of the tide. While the introduction of germ theory created a dramatic change overall, the transformation of beliefs and practices occurred in ebbs and flows spread across a variety of spaces and left behind scattered pools of unchanged thoughts. Decisions made in the home and discoveries made in the lab might have occurred in the same decades and in the same cultural context, but they did not necessarily happen for the same reasons.2

Women participated in conversations about disease etiology, sanitary science, and healthful environs. As they had been in antebellum homes, women were on the front lines of health preservation and disease prevention, and they guarded their families’ health both with methods proven effective by time and with the new ideas that circulated in scientific journals and the popular press. Like sanitarians and physicians, women had learned from the Civil War that there were times and places when it was impossible to access the fresh air that regularly blew across open space, but its beneficial qualities could be re-created through chemical disinfectants. Chemical disinfectants thus added to the common understanding of fresh air before germ theory. This augmented understanding of how to replicate the healthful benefits of fresh air was particularly important in cities, as the continued proliferation of industries and population growth made urban spaces increasingly foul after the Civil War. Even after the widespread acceptance of germ theory by the medical community in the 1880s, both physicians and everyday Americans continued to believe that fresh air was healthful, and they labored to ensure the presence of fresh air in the same ways as before: through disinfection, ventilation, and the use of sweet fragrances. The introduction of germ theory did not change existent practices but provided a new rationalization for why these practices worked, the explanation that had eluded the confused student.

Although germ theory did not change lay practices, it deepened the separation of medical practitioners from everyday Americans. Physicians and chemists became health board officials and scientific experts with jurisdiction over entire cities, while the women who had learned about disinfectants and health as Civil War nurses continued to oversee the home. Homes were growing larger and ever more connected to the city environs, expanding both the space and the potential health threats that women had to understand and manage. As Harriette Plunkett, domestic advice author and the wife of a Boston politician, explained women’s responsibilities in 1885, “Her ‘sphere’ begins where the service-pipe for water and the house-drain enter the street-mains, and, as far as sanitary plumbing goes, it ends at the top of the highest ventilating pipe above the roof.” Despite the separation of the “domestic sphere” from the politics of public spaces, women and health authorities recognized that efforts to preserve health in the home overlapped with efforts to accomplish the same throughout the city. Thus many of the documents circulated by city health boards and the domestic guides authored by women encouraged the use of chemical disinfectants in homes, explained new sanitary knowledge, and engaged germ theory. In their quest to ensure healthful environs, whether citywide or in individual homes, health officials and women were working toward the same goal and with similar knowledge and tools, but from opposite ends of newly installed sewer systems.3

EARLY CHALLENGES AND DISINFECTANT SMELLS

Scientific authorities had begun introducing disinfectants as a category of household chemicals separate from deodorizers in the 1850s. According to James Finlay Weir Johnston’s Chemistry of Common Life, chemical disinfectants differed from commonly used deodorizers by destroying both the poison and the smell. This distinction quickly made its way into domestic guides to science, in which men such as Edward Livingston Youmans chastised women for using “palliatives and disguisers” rather than chemical disinfectants. As Youmans, the founder of Popular Science, wrote in 1858, “When atmospheric impurities report themselves to the olfactory sense, they are pretty sure to receive attention, though we too often seek only relief from the disagreeable smell. This is done, not by removing it, but by smothering or overpowering it with sweet scents.” Youmans worried that by masking foul, unhealthy odors with the strong but pleasant smells of musk, attar of roses, fragrant spices, and aromatic vinegars, people tricked their noses into thinking the air was pure and healthy. In short, Youmans argued that sweet smells did not create fresh air.4

Rather than overpowering bad odors with sweet ones, Youmans advocated “cleansing the air” by “removing rather than concealing or destroying the offensive bodies.” Youmans believed that chemical disinfectants could “destroy evil odors and injurious gases” without disturbing their material sources. Whereas Catharine E. Beecher’s trusted domestic manual advocated removing odors by removing their sources, Youmans recommended a roster of chemicals that were familiar to women. Freshly burned lime, or quicklime, purified the air by attracting and removing carbonic acid, the danger in vitiated air. Chlorine gas cleansed and disinfected the air by attracting, decomposing, and destroying hydrogen compounds, “the gaseous poisons of the air,” and sulfurous acid had a similar effect. But Americans knew both chlorine and sulfur as noxious; chlorine irritated and inflamed one’s nose and throat, and sulfur had a “noxious odor … injurious to health,” so the use of either disinfectant required the evacuation of the space being cleansed and open windows to diffuse noxious disinfectant smells.5

Though Youmans recommended chemicals in place of sweet fragrances, he did this without knowledge of bacteria or microbes. Youmans believed that miasmas caused illness and aimed to improve the air with his disinfectants. This is evident in his instructions for using his preferred disinfectant, chloride of lime: “It may be dissolved in water and sprinkled through bad smelling apartments, or cloths dipped in a diluted solution of it can be hung up in the room. After infectious diseases, a weak solution of chloride of lime should be sprinkled over sheets and family linen before washing, and the walls of the room washed down with it.” This range of applications did not fight odors at their source or require identifying a miasma’s origins but was a general approach to preventing disease by treating the air.6

Women already possessed the methods and chemicals recommended by Youmans and employed these with care. Women knew that these chemicals were effective but also poisonous; they regularly used chloride of lime to kill rats, mice, and cockroaches as well as to purify the air. When the Beecher sisters added a section on chemical disinfectants to their 1869 guide, they included words of caution: “Great care should be taken to guard against [the disinfectants] getting into any article of food or utensil or vessel used for cooking or keeping food, or where children can get at them.” Before warning labels or childproof cupboards, women knew that the same substances that cleansed the air and created a healthy atmosphere were also poisons that would cause sickness and death if used improperly or ingested by children.7

At the same time that chemists were starting to distinguish disinfectants from deodorizers, medical authorities began questioning the connection between odors and disease. As early as the eve of Civil War, the Chicago Medical Journal wondered, “Do Bad Smells Cause Disease?” In response to public health reform and newly strident campaigns against commonplace nuisances such as pigsties, ash heaps, pools of dirty water, and open privies, the authors suggested that attributing all fevers to stinking environments was oversimplification. As evidence, the journal referred to a recent study of Londoners who labored among the nuisances targeted for removal. Although they regularly inhaled a “so-called miasmatic atmosphere” from cesspools and piles of household waste, these workers were in good health, and thus the Chicago Medical Journal amended miasma theory. The authors concluded that bad odors were not dangerous in and of themselves but “become noxious when much concentrated.” Where freely moving air could diffuse foul odors, there was little danger of falling ill; but where the air was still and foul odors built up, they were likely to cause disease. This recognition focused attention on the home: “Our houses, for instance, are built on the principle of a bell-glass; and our drains and privies, and all other impurities, if allowed to give off a deleterious miasma, most certainly do become most virulent sources of disease.”8

A similar conversation took place in New York City at the end of the Civil War. When the Polytechnic Association of the American Institute investigated the causes of New York’s odors, one of its members observed, “In the part of the city where the odor complained of is the strongest, the children are remarkably plump and healthy.” The speaker concluded that although the odor “may be offensive to some,” it did not harm health. The Herald of Health disagreed vehemently with this conclusion, as did a “sensible young man” in the audience who responded that “those who lived in cleaner neighborhoods and fine houses may, and often do, because of inattention to ventilation, breathe a worse atmosphere than do those whose domiciles are among barn-yards and pig-pens.” Both the audience member and the Herald of Health insisted that concentrated odors required careful attention, whether in cities or in homes, until research could determine “what the noxious principles are that make the difference between an unpleasant and malarious odor.” Individuals such as these were open to alternative explanations for disease but unwilling to abandon olfactory concerns until another explanation could be proven.9

While some Americans were questioning miasma theory in the 1860s, most agreed that concentrated odors constituted a serious health threat. If anything, the massive scale of Civil War destruction reinforced common knowledge about the dangers of concentrated odors. The lingering stenches and ill health of large battlefields and camps in otherwise rural areas also taught Americans that odors could be concentrated in open space as well as within buildings. Free-moving air could no more dissipate the intense stenches of environments disrupted by war than those of poorly ventilated homes. Thus the experiences of the Civil War bolstered the belief that cities were unhealthy environments where foul air accumulated in the large spaces that urban development filled with industries, residences, and their refuse.

The Civil War also proved many of Youmans’s prewar claims about chemical disinfectants and spread this knowledge widely. Everyone who passed through a hospital, whether patient, nurse, doctor, or visitor, came in contact with disinfectants and learned that the benefits of fresh air could be re-created in foul spaces through the application of chemicals. As the nation braced itself for cholera’s advance in 1866, city governments urged the public to employ disinfectants. In Philadelphia, the Sanitary Committee advised citizens to focus on the familiar domestic concerns of cleanliness and ventilation, and urged disinfection, but the committee explained the effects of these activities in new scientific terms. Ventilation, achieved through open windows that admitted sunlight and fresh air, would purify homes by oxidizing and drying. “Purifiers, antiseptics and disinfectants” would “absorb impure exhalations, prevent decomposition, and destroy noxious gases.” In a pamphlet for the public, the Sanitary Committee instructed Philadelphians to apply these chemicals “when there are offensive odors emitted” and explained that disinfectants such as sulfate of iron, chloride of zinc, and nitrate of lead worked by “combin[ing] with the Ammonia and Sulphurated Hydrogen, and thus for the time being correct their offensive odors and noxious influence.” In pamphlets such as this one, medical authorities promoted disinfectants as a new category of disease-prevention agents but conflated the olfactory effects of these chemicals with their antiseptic power because they had not yet learned to distinguish between the two.10

In domestic guides, women also blended old beliefs that bad smells caused disease with new knowledge about chemical disinfectants. In her 1872 New Cyclopaedia of Domestic Economy and Practical Housekeeper, Elizabeth Fries Ellet reiterated Catharine E. Beecher and Andrew Jackson Downing’s preferences for heating by fireplaces over stoves, maintaining that open grates were better for maintaining a “salubrious atmosphere” and stoves were “apt to give the air a close or disagreeable smell.” Ellet also repeated Beecher’s advice about airing rooms, clothes, furniture, and all fabrics that harbored both stale odors and illness. Yet Ellet differentiated disease prevention from disinfection, explaining that the latter was a distinct practice for destroying infection. In this breakdown of household care, fresh air and ventilation were necessary to prevent infection, while “the best means of destroying it [infection] are those powerful chemical agents which have the power of uniting with the hydrogen which is supposed to form part of the infectious substances.”11

Ellet clearly understood the chemical activity of hydrogen within the home, and she was starting to differentiate the actions of different chemicals from that of fresh air. Female authors such as Ellet applied the new language of disinfection to chemicals they had long been using in their homes, reflecting a refined and deepened understanding of how substances such as quicklime worked. For example, in 1880 Beecher’s sister-in-law, Eunice, offered this solution for mildew in damp closets: “By putting an earthen bowl or deep plate full of quicklime into the closet the lime will absorb the dampness but also sweeten and disinfect the place.” Quicklime, which had long been central to the household cleaning arsenal and remained the key ingredient of whitewash, provided three overlapping services by absorbing moisture, improving the smell, and killing germs. Eunice Beecher’s phrasing indicates that “sweeten and disinfect” were now separate functions of household chemicals and that both functions remained desirable.12

DISINFECTING PLUMBING AND IMPROVING VENTILATION

Women were particularly eager to sweeten and disinfect spaces they could neither touch nor see, but could smell. The enthusiasm for household plumbing that had begun in the 1840s continued apace after the Civil War, becoming more common in American homes and changing the odors about which women worried. Though the Beecher sisters advocated the earth closet instead of wastewater plumbing in 1869, Catharine E. Beecher gave in to popular demand and turned her attention to the plumbing needs of water closets in her 1873 Housekeeper and Healthkeeper, explaining that while earth closets might replace wastewater plumbing in the future, “at present the water is much more convenient.” Indeed, most of Beecher’s contemporaries with means were installing water closets, sinks, boilers, and the ultimate luxury of bathtubs. As they connected new plumbing fixtures to city sewer lines for effortless waste removal, householders quickly discovered plumbing’s dangers. Foul smells and “sewer gas” entered the home through plumbing connections and ultimately escaped from unsealed pipes and faulty fixtures to alter domestic ventilation and, many thought, poison the air. While city residents complained about the concentrated stenches of sewer outfalls and health boards turned their attention to these new features in the urban smellscape, women and domestic guides focused on the health threats posed by household plumbing.13

Like the latrines of the Civil War camps or cesspools in antebellum cities, sewers released odors and gases that both lay citizens and health officials considered dangerous. Roger S. Tracy, a sanitary inspector for New York City’s Board of Health, claimed that breathing concentrated sewer gas would produce immediate unconsciousness and death and that inhaling diluted sewer gas caused nausea, vomiting, low fever, and a “tedious convalescence.” This list of afflictions only grew; by 1893, Americans had blamed sewer gas for “small pox, scarlet fever, measles, malaria, diphtheria, typhoid, inflammations of the ear, eye, throat, etc., dyspepsia, diarrhoeal affections, coughs, colds, lung diseases, liver affections and skin troubles.”14

Olfactory vigilance could identify sewer gas and diagnose plumbing problems. Tracy instructed women to recognize sewer gas by its odor of rotten eggs, which indicated the presence of sulfide of ammonium and sulfureted hydrogen. However, since Tracy thought sewer gas’s other constituents—carbureted hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbonic acid—were odorless, he recommended expanding the nose’s diagnostic powers through the peppermint test. The principle of this test was simple: pour some peppermint oil down a drain to introduce a distinctive odor into the pipes and then sniff around the home. Wherever one smelled peppermint, there was “an opening in some pipe, through which sewer-air may escape.” The other reason for the peppermint test was to check whether the smells were in fact coming in through the pipes; odors in city homes could also emanate from rats decomposing in the walls or waft through walls from faulty plumbing in an adjoining house. While leaking or improperly sealed pipes were the most likely source of sewer gas, “the walls of buildings [were] full of channels and openings, through which offensive gases might be carried by currents of air, so as to emerge at a considerable distance from their origin.”15

Whereas Tracy and other sanitary inspectors knew the danger of sewer gas and the necessity of testing for its presence in homes before illness struck, the vast majority of those who embraced household plumbing remained ignorant of sewer gas because it accumulated slowly and rarely reached the fearful concentrations of stenches from cesspools or latrines. Brooklyn’s Moreau Morris, a doctor and sanitary engineer, warned the readers of the Sanitarian that “the slow insidious poison from these sources [defective drainage and sewerage], so gradually and imperceptibly infects the system, that it is oftentimes with the greatest difficulty that persons thus exposed can be aroused to a true sense of their danger.” Morris and other sanitary engineers launched a public education campaign in the pages of trade journals and the popular press to convince householders of the threat’s existence and to explain how to remain vigilant against an invisible nemesis. These lessons even took the form of verse:

Our drains! our drains! our foul, leaking drains!

They poison the air of our streets and our lanes,

....................................................

How can we have health if the blood in our veins

Is poisoned by breathing foul air from drains?”16

Illustrations were even more explicit than rhymes. In 1875, a full-page illustration of the dangers of sewer gas appeared in the Days’ Doings, Frank Leslie’s penny paper better known for its licentious coverage of criminal, sporting, and theatrical events than attention to sanitary issues. In “The Death-Traps We Live In,” a family sobbed over the body of their young daughter and a nurse administered medicine to an ill infant, oblivious to the sewer gas steadily and silently seeping into the bedroom from the corner sink. The home’s extensive plumbing, which also included a large bathtub in the adjoining room, furnished death and despair rather than convenience.17

The cause of the child’s sickness was a familiar one, the lack of ventilation, but plumbing complicated ventilation systems. In this case, the sewer connection needed to be ventilated by continuing the waste pipe to the roof of the house, where sewer gases could escape to the harm of none but possibly a few birds, whose inclusion in the illustration reflected the recognition that indoor and outdoor environments were closely connected. The foul-air trap, the bend of pipe beneath drains that created a water seal, was ineffective without pipe ventilation, and its dangers were many. If sewer gases did not have an outlet, their pressure would build until the gases forced an exit, which the illustration depicted in its scene of sickness and farther down the page, where gases burst in flame from cracked pipes. The illustration also shows how commonsense solutions were ineffective against this new health threat: women might try to fill a basin with water to block sewer gases’ entrance, but sewer gas would pass through the overflow pipe instead. Even in the finest homes, inattention to “the new style of waste pipe system” would result in pestilence and the early graves depicted in the bottom-left corner.

FIGURE 6.1. Faulty plumbing connected to an unventilated sewer was an invisible but deadly threat in this illustration of modern homes. The schematics below the picture of the sobbing family explain common defects that allowed sewer gas to enter the home and the proper way to plumb a house to protect the health of its inhabitants. “The Death Traps We Live In,” Days’ Doings, November 27, 1875, 8, Charles F. Chandler Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York.

Illustrations such as this one were instrumental in spreading the knowledge of newly recognized dangers in the household and the newest fixes for these problems. Innovations in technology and domestic advice occurred rapidly, often barely keeping up with each other in the race to improve the home and protect the health of its inhabitants. Engineers ventilated sewers and drainage systems with air-inlet pipes, vent pipes, and the extension of soil pipes above the roof. Sanitarians also devised traps—literally, bends in the pipe that trapped enough water to block the movement of air. These innovations were commonly advertised as “stench traps,” a name that appealed to consumers’ desires for indoor toilets without the smell of the outhouse. Water seals were an improvement over straight pipes but an imperfect solution, because evaporation, back pressure, and siphonage could break the seal and make the home vulnerable. Pan closets and incomplete flushing added to the dangers of plumbing, as both retained rather than expelled wastes from the home. Excrement clung to the sides and corners of pan closets, a waterless toilet that emptied by gravity as the user raised the pan to slide wastes into the soil pipe, and released the noxious effluvia of human waste into living and sleeping rooms. Furthermore, leaking drains spilled foul water and wastes into the ground beneath the home. As the Days’ Doings illustration showed, ground air thus tainted would be carried throughout the home by the updraft that fires and furnaces created in winter months. While plumbing systems eliminated the trip to the outhouse, such convenience complicated homes and health in many other ways.

Physicians and engineers loudly criticized women for not understanding how their homes sickened their families. In 1883, Charles F. Wingate, editor of the Plumber and Sanitary Engineer, blamed illness on mistaken attempts to improve the home. Wingate told the wide audience of the North American Review that when Britain’s Prince Albert died from typhoid fever in 1861, the real culprit was Albert’s castle. Wingate had recently learned that Albert’s study seat had been located directly above a cesspool, “whose emanations were undoubtedly the cause of his disease.” In Wingate’s retelling, the deadly defects of castle construction were a parable that should frighten wealthy Americans into evaluating the safety of their own domestic sanitary arrangements. In Murray Hill, where some of New York’s wealthier residents made their homes in “palatial residences,” the houses crowded so closely together that sunshine rarely entered. Fresh air was also absent from these homes, since “careful housekeeper[s]” shut the windows tightly against the smells of stables, factories, and Hunter’s Point. In excluding the city’s stenches, women inadvertently exposed their families to the poorly ventilated air of the furnace register, made worse by the odors of kitchen, laundry, and faulty plumbing, so that foul odors concentrated in mansions just as they did in overcrowded tenements. Wingate concluded that “our people are starving for the want of fresh air,” and “ventilation is decidedly one of the lost arts.”18

Ventilation had not been lost exactly, but domestic guides were not keeping pace with the proliferation of new household technologies. Boston’s Harriette Plunkett noted that the newest domestic advice of the 1880s focused almost exclusively on cooking methods, aiding women in adapting recipes to their new cookstoves. As a consequence, these books excluded the information about household construction, air circulation, and healthfulness that older domestic manuals had contained, despite changing technologies for ventilation that also required explanation. To fill the void and provide updated information on plumbing and ventilation, Plunkett dedicated her specialized volume of domestic advice, Women, Plumbers, and Doctors, to “the less obvious but equally important topics of pure air and pure water.” In exploring these issues, Plunkett directed women to reexamine their entire homes, from the trees in the yard and the soil beneath their basements to the air that entered attic windows. She explained that close examination was especially important in cities because urban houses often changed hands, obscuring the blunders of previous owners, and because sewers linked buildings of varying degrees of healthfulness over a large geography. Plunkett instructed her readers that, though improving sewer systems was the province of voting men and city governments, women had complete control of and responsibility for the home. Sewers connected the interests of housekeepers with those of city officials.19

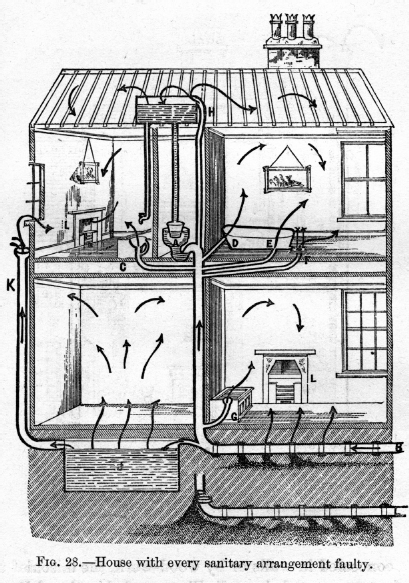

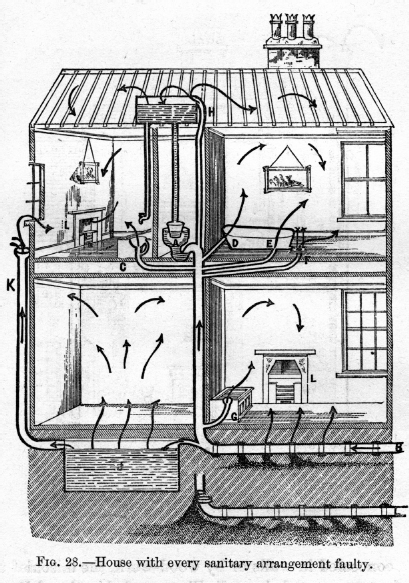

The same women who had carefully studied Beecher’s instructions for ventilating rooms with stoves now turned to Plunkett’s manual for lessons on detecting and controlling the air currents created by plumbing. Plunkett included numerous illustrations of ominous arrows emanating from plumbing fixtures to show her readers how dramatically drains changed the air of their homes. In an illustration captioned “House with every sanitary arrangement faulty,” foul air entered through every crack and fissure, swirling around rooms and finding its only exit through the chimney, as all the windows were tightly closed. Most of the sewer gas remained, vitiating the air before family members ever entered the room and inhaled. Plunkett contrasted this image with that of a properly plumbed home, wherein a full system of traps and ventilating pipes controlled and contained air currents, safely conducting sewer gases out of the house rather than poisoning domestic air.

Plunkett’s volume moved methodically through the house, from cellar floor to attic roof, teaching women to look for openings, vents, cracks, and construction defects that made the home permeable and constantly reminding women of the importance of fresh air. The goal, Plunkett explained, was not to seal the home off entirely, which would violate the principles of ventilation, but to control the home’s permeability and thus the family’s health. In the cellar, a floor of Trinidad asphalt, “as impervious as glass,” would offset the risks of wet soil and ground air loaded with carbonic acid that were the bane of cellar apartments everywhere. A safe basement was important to the entire house because public health authorities and doctors believed that buildings acted as bell jars, retaining the gases exhaled from the ground below them. To make this point, Plunkett used the example of a family who abandoned their $40,000 home on Fifth Avenue because of recurrent bouts of illness that had killed two children. The new owner discovered the home’s fault in the cellar, where a sickening stench emanated from a heap of discarded turnips, mildewed sponges, and decaying wood. Plunkett explained that the previous mistress had never descended to the cellar, leaving the nether regions of the house to her servants, and that this oversight had killed her children. Plunkett noted that this fashionable woman “never drank a glass of water without holding it up to the light to detect visible impurities. It never occurred to her to investigate the vital air she was hourly breathing.” Plunkett’s comparison was slightly unfair, as it was impossible to see impurities in smelly air.20

FIGURE 6.2. Arrows indicate the entrance of sewer gas through unsealed pipes and its movement throughout the rooms of the home. In a house with the windows closed, sewer gas could only exit through the fireplaces and chimneys, so it was likely to build up to unsafe concentrations. “House with Every Sanitary Arrangement Faulty,” in Mrs. H. M. Plunkett, Women, Plumbers, and Doctors; or, Household Sanitation (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1885), 123. Used with permission from the Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University Libraries.

Just as in the antebellum period, the invisibility of foul air made homes deadly. When plumbing was hidden within walls, it added to the unseen and easily overlooked dangers of the home. Thus Plunkett recommended attention to both plumbing materials and the location of pipes. Plunkett cited the recommendations made by New York City sanitary engineer William Paul Gerhard for household plumbing constructed of iron or other “strong, hard, well-burnt, vitrified” materials instead of brick and wood. Like the cellar floor, these pipes should be impervious to both moisture and gas. Lead, though easily pliable for bends and traps, was not strong enough for household plumbing; Gerhard recalled tracing the smell of sewer gas “to a picture-nail driven into a lead vent-pipe concealed behind the plaster of a room.” This error might have been avoided had the mistress of the house kept a map of the plumbing, one of Plunkett’s key recommendations. Rather than a map, Gerhard suggested that pipes not be hidden within walls or encased in plaster, because such arrangements made it difficult to locate the damaged section. If pipes were visible, one would not accidentally nail through the plumbing, and defects could be quickly ascertained and fixed.21

Plunkett and Gerhard disagreed about more than just the visibility of pipes; they also differed on the subject of germ theory. Plunkett and Gerhard wrote about sewer gas while germ theory was beginning to gain acceptance in the United States, but new knowledge about germs did little to change Plunkett’s or Gerhard’s beliefs about the dangers of sewer gas. Gerhard noted that research conducted in the laboratory of Bavarian chemist and hygienist Max Joseph von Pettenkofer led to the conclusion that foul odors might disrupt comfort but did not adversely affect health. Not yet convinced of germ theory’s veracity, Gerhard argued against the hasty rejection of long-standing knowledge about odors: “As long as there are doubts as to the causes of infectious disease, it is wise to err on the side of safety.” Rather than debate the infectiousness of sewer gas, Gerhard accepted common sense about bad smells and urged his readers to prevent the contamination of domestic air by foul gases.22

Plunkett was more open to the idea of germ theory than Gerhard, but like other health authorities and domestic authors, she too folded new ideas about microbes as the seeds of disease into older beliefs about miasmas as the source of illness. Even though physicians had conclusively determined the specific microbes that caused some diseases by the 1880s, the sources of deadly epidemics like the yellow fever that decimated Memphis in 1878 were still a mystery and assumed to be atmospheric. Consequently, Plunkett urged the same course of action as Gerhard, taking preventive measures to exclude sewer gases and all other foul odors from the home. Though Plunkett worried about germs and advocated wastewater plumbing, a stark contrast to Catharine E. Beecher’s earlier fears of miasma and reluctance to move the outhouse indoors, Plunkett’s recommendations for a healthy home ultimately repeated Beecher’s. Despite following different medical theories, both women advocated the same environmental logic and instructed their readers to pay attention to ventilation, admit fresh air into the home, and banish the sources of foul smells.23

THE NOSE AS A SANITARY AGENT

The peppermint test was not the only way that women continued to use the sense of smell to evaluate domestic healthfulness as germ theory gained adherents. Plunkett’s tale of the fashionable Fifth Avenue wife who lost two children when putrefaction-laden cellar air rose through the house raised an important issue: How was it possible to ignore the sources of miasma or germs in one’s home? Even if she never entered the cellar, the Fifth Avenue wife must have smelled the foul air emanating therefrom. Plunkett used the death of these children not only as a lesson in the importance of examining the entire house but also to explain the dangers of familiar odors. Because the smell was a constant presence in her home, changing gradually as the refuse accumulated, it never assaulted the woman’s sense as did the stenches one suddenly encountered in full force while moving through the city. Thus the woman’s familiarity with the smell kept her from thinking it dangerous or investigating its source.24

Both physicians and domestic authors battled the familiarity of foul odors. When health officials encountered foul air in tenements, and women wrote about odors imperceptibly accumulating in cellars or emanating from plumbing fixtures, they worried about the dullness of the human nose. Because these odors were so commonplace or familiar, the individuals who constantly inhaled the compromised air seemingly did not notice the offensive smells. Yet the danger of these smells remained. As Celia M. Haynes, a Civil War nurse and one of the first female physicians in Chicago, explained in her 1887 Happy Home Health Guide, “If we ignore Nature, and submit ourselves to foul air until our sense is dulled, that does not save us from the consequences. Many a case of malaria owes its origin to a filthy cellar.” Thus, while domestic guides and health officials taught individuals to use disinfectants and kill germs, they continued to train readers’ noses to recognize unhealthy odors. The goal was for everyone to employ “the nose as a sanitary agent,” as sanitarian and Michigan Board of Health member Charles H. Brigham advocated in the pages of the Herald of Health. Brigham argued that the nose “warned of danger as effectually as a watch-dog, or as an alarm-bell,” and summed up the nose’s sanitary importance with three simple rules: “It is a safe rule to follow, never to eat any thing that has an unpleasant smell, never to wear any thing that offends this sense, never to live in any place where this sense is vexed and irritated.”25

Though Brigham made his recommendation before germ theory was widely known or understood, the principle of heeding one’s nose remained relevant after germ theory’s acceptance. Authors who wrote after germ theory, such as Haynes, repurposed rather than dismissed the sense of smell as a diagnostic tool. Haynes authored her domestic advice book because new knowledge had made older guides obsolete: “Important discoveries are constantly being made; new experience changes the old practice; certainty, little by little, is taking the place of theory, so that a book which at one time may be justly regarded as a good authority, in a few years is out of date.” Haynes believed in germ theory and dedicated a chapter to the microscopic germs that she explained abounded everywhere. While Haynes and other physicians now believed that the air teemed with germs rather than miasmas, she maintained that the nose scented germs just as it had miasmas: “Wherever foul smells exist, or any form of germ life grows, such as mold or mildew, there everything is favorable for other germs.” She also explained that bad odors were still harmful to health, though indirectly: “A bad odor means the presence of germs or gases, usually both, neither of which are fit to enter the human body, and that is why Nature made this offensive, and gave us the sense of smell to detect them.” Both before and after the introduction of germ theory, good health was the result of heeding one’s nose.26

Noses could only object to the bad smells of food, clothes, and homes if people trained themselves to recognize rather than ignore dangerous odors. Therefore, domestic advice authors launched an olfactory reeducation campaign. Catharine E. Beecher had begun this work with gentle reminders about the offensiveness of everyday smells: “Fish and cabbages, in a cellar, are apt to scent a house.” In House and Home Papers, Harriet Beecher Stowe explained how the “effluvia of vegetable substances” infused cream in storage and tainted butter with the flavors of cabbage and turnip. Plunkett contributed with her explanation of how to banish the cellar’s dangerous vapors. Christine Terhune Herrick, a frequent contributor to Good Housekeeping and daughter of the popular author Marion Harland, chastised women for assuming that “the unwholesome and unpleasant odor that rises like a cloud whenever the cellar-door is opened” was natural to underground rooms. Instead, Herrick argued, the accumulation of rubbish in damp, poorly drained spaces produced the odor associated with cellars. Rather than enduring this musty smell, women should recognize that the cellar’s emanations caused “slight but persistent unhealthiness in the family” and strive to keep the space belowground as clean and airy as the rooms above.27

Plunkett, Haynes, and Herrick accepted germ theory, but the belief in germs changed neither their emphasis on olfactory vigilance nor the practices they recommended for household health. Both before and after germ theory, the traditional practice of “airing” rooms, bedding, and clothing remained simple, popular, and effective. According to Herrick, “the odor of stale breakfasts and dinners is extremely de-appetizing” but could be avoided by daily airings of the dining room following each meal. Echoing Beecher, Herrick also advocated airing out clothes before hanging them in the closet and airing the closet itself by removing all the clothes and leaving both closet door and the room’s windows wide-open for hours. She further explained that all bedding, from coverlet to the mattress itself, should be hung in the open air to release the effluvia absorbed from resting bodies. Such advice was not new but was imbued with new meaning by experiences with germ theory, chemical disinfectants, and the oxidizing power of ozone.28

OZONE: THE FRESHNESS IN FRESH AIR

Airing remained a common, effective practice within both domestic advice and medical circles because it employed fresh air. As physicians debated the validity of germ theory and the effectiveness of chemical disinfectants, they never wavered in the celebration of fresh air as necessary for health. At the meeting of the American Public Health Association in 1879, doctor Henry Fraser Campbell of Augusta, Georgia, insisted that fresh air would remain a central and important agent for health because it was a proven disinfectant:

Freezing, steaming, and the diffusion of atomized chemical germicides, have caused us greatly to forget the trust we so long have given to thorough ventilation in fresh and healthy air as a disinfectant, not only in the case of germs, but even where the virus of the most contagious diseases was to be combated. What other disinfectant do we practically now depend upon for the protection of families, when, as physicians, we go from the bedside of scarlatina, of diphtheria, and measles, but the airing of our clothes in passing from house to house? And it is known how seldom medical men carry infection in their daily rounds of attendance. This, we can all remember, must have been the great disinfectant which, in the slow-going days of stages and coaches, and private travel, so purified the refugee from all atmospheric propagating germs.29

Direct experiences with fresh air, like those described by Campbell, taught all Americans that fresh air was an able disinfectant. By definition, fresh air was healthy and did not cause illness, but this common knowledge had new scientific backing after the discovery of ozone in 1839. Following German chemist Christian Freidrich Schönbein’s explanation that the “odor of electricity” was a form of oxygen consisting of three atoms instead of the usual two, chemists and sanitarians fixated on the presence of ozone and its connection to health. Scientists on both sides of the Atlantic measured ozone’s presence in nature and realized that ozone was abundant in the countryside, at the seashore, and at higher elevations, all places that people sought for good air. At Stevens Institute in New Jersey, chemist A. R. Leeds argued that ozone was what made the sanitariums of the Adirondacks so effective. Conversely, measurements showed that ozone was lacking in cities and nearly absent during epidemics, leading many to conclude that ozone was the freshness in fresh air.30

The chemists who studied ozone and witnessed its oxidizing powers decided that ozone “plays a very important part in the economy of nature.” In other words, they thought that ozone was nature’s way of cleaning up and restoring the air: “By virtue of its extraordinary affinity for the products of decomposition it undoubtedly purifies the air of localities in which it abounds by destroying noxious gases and by oxidizing decomposing organic substances.” This belief quickly made its way into the popular press and advertisements, where editors and inventors celebrated ozone as “the natural scavenger” that could clean foul air and ward off urban disease. As authors cited chemical studies and their personal experiences, they promoted the idea that wherever there was ozone, there was health—and wherever ozone was absent, disease would flourish. This association of ozone with health remained powerful well into the twentieth century, until the negative effects of ground-level ozone on respiratory tissue became obvious in smoggy cities.31

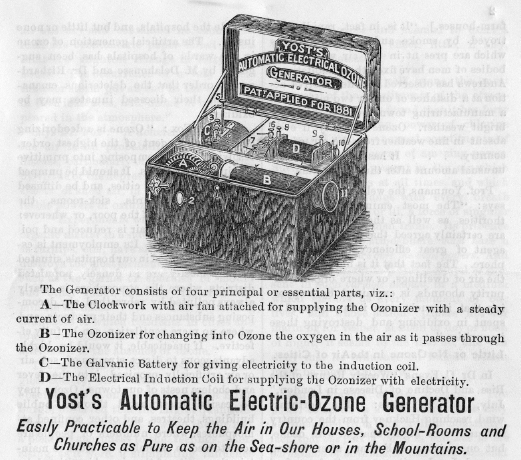

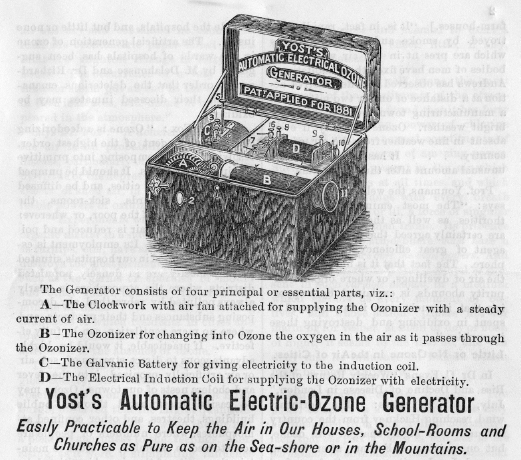

Once they had identified ozone as the difference between healthy air and city air, sanitarians hoped to apply this knowledge to improve the health of cities. If ozone were the freshness in fresh air and nature’s disinfectant, as so many claimed, then it was logical to think that cities could be made healthy by an infusion of ozone. When he outlined the features that made the fictional Hygeia a health utopia in 1875, British sanitarian Benjamin Ward Richardson included an ozone generator that would pump the gas into private homes throughout the city. Richardson’s optimistic future sprang from an existent technology. Schönbein and other chemists had generated ozone in their laboratories by electricity and by phosphorous reactions, leading to the idea that humans could create fresh and healthy air anywhere.32

FIGURE 6.3. Ozone generators promised to re-create the healthful air of the seashore or mountains in the closed spaces of houses, schools, and churches. Advertisement for Yost’s Automatic Electric-Ozone Generator, ca. 1879, Charles F. Chandler Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York.

The ozone generator heralded a change in the relationship between individual spaces and the surrounding environment. In every pamphlet and article advocating chemical disinfectants, health officials were careful to explain that these substances replicated the benefits of fresh air within foul spaces but were neither a substitute for nor preferable to fresh air. The scientific belief that ozone was nature’s disinfectant led to different conclusions, because generating ozone meant generating fresh air rather than merely replicating its benefits. By using ozone generators, people would not have to travel to the seashore or mountains to access fresh air but could create fresh air wherever they lived. Thus ozone generators promised to free homes and offices from foul emanations in the immediate environs and to solve the problem of windows that either opened to admit smelly urban air or shut occupants in with the foul air that they vitiated by breathing.

Doctors and public health officials soon recommended the use of ozone in a wide variety of contexts. In 1878, Nashville doctor J. D. Plunket suggested stringing interrupted wire through sewers, connected to a battery or engine that would provide the spark to produce ozone. Ozone thus generated would “antagonize and render harmless the hydra-headed monster, sewer-gas,” as long as the spark did not ignite the gas. The Encyclopedia of Health and Home, authored by three physicians, gave instructions on how to mix permanganate of potash and sulfuric acid to generate ozone in the sickroom. These doctors recommended the constant presence of ozone for the “invigorating quality … imparted to the atmosphere of the room,” especially when the room could not be opened to admit fresh air. The American Ozone Company, founded by Chicago’s public health pioneer John Henry Rauch, patented ozone generators for physicians. The company’s pamphlets advocated ozone treatments as a replacement for visiting distant locales in search of fresh air: “The physician can give his patients more Ozone in an average treatment of twenty minutes in his office than they could get in one hundred hours in any country or seaside resort.” While the ozone generator would not supplant other medical remedies, it would overcome the “impure office air” that might inhibit a patient’s recovery. Inventors addressed the lack of ozone in city homes by patenting their own ozone generators that they advertised for household use with the same promises: that ozone was healthful, would destroy both odors and germs, and would create the healthy air of seashore or mountaintop in the home.33

Women rarely discussed ozone by name in domestic advice, but the scientific belief that ozone was healthful reinforced women’s traditional practices. In 1884, the Ladies’ Floral Cabinet recounted recent ozone experiments that gave scientific validation to common knowledge about the healthfulness of fragrant plants. In Philadelphia, the publication wrote, a Dr. Andrews “has shown that plants in sleeping or sick-rooms fulfill two functions, namely: that of the generation of ozone and exhalation of vapor, by which the atmosphere of the room is kept in a healthful condition.” Similarly, Italian professor Mantegazza “discovered that ozone is generated in immense quantities by all plants and flowers possessing green leaves and aromatic odors.” Mantegazza’s experiments revealed that the most fragrant plants produced the largest quantities of ozone, and so he recommended “the use of strong and pungent aromatic substances as a prophylactic against malaria through the ozone thus produced.” Mantegazza’s recommendations included the same fragrant plants that women had long been planting in their windows: hyacinths, mignonette, and heliotrope. Knowledge of ozone similarly bolstered the practice of airing rooms, bedding, and clothes, as the casual mention of ozone in an 1895 Ladies’ World column illustrates: “Try it [airing] every day, and don’t forget that the mattresses and the feather beds, bolsters and pillows will part with their peculiar body odors, and bring in [to the home] an abundance of oxygen and vivifying ozone, if you will only hang them out of the window for a couple of hours in windy weather every few days.”34

As scientific research provided new rationales for old practices, and sickness continued to proliferate in cities, new charities combined scents, disinfectants, and fresh air. In the 1870s and 1880s, middle-class women capitalized on the universal appreciation of and desire for sweet scents by forming Flower Missions in cities including Boston, New York, Cincinnati, Saint Louis, and Indianapolis. Flower Missions were premised on the belief that the healthfulness of the countryside could be imported into the worst parts of the city through colorful and fragrant blooms that would literally brighten the city’s shadows and inspire those who suffered. These charities collected donations of excess plants from suburban and rural women, arranged the stems into bouquets, and delivered the bounty to the impoverished sufferers in city hospitals. The early successes of these organizations soon led to an expansion of recipients. The New-York Flower Mission distributed its fragrant alms to prisons, crowded factory rooms, asylums, Children’s Aid Society schools, and tenement houses.35

In the popular understanding of health and fragrance, Flower Missions were dispensing disinfectants to the city’s most dangerous breathing spaces, the foul air of tenements and hospitals. Recipients of these ministrations specifically praised the charities for distributing sweet fragrances, rather than commenting on the Victorian “language of flowers” that imbued plants and bouquets with specific meanings. Reporters noted that floral decorations visibly brightened hospital wards and, just as importantly, dispelled “the sickening odor of chloroform.” Doctors and surgeons frequently praised the missions’ work, testifying that the flowers did as much good work as the physicians’ own ministrations. “The most eminent surgeons and medical men in the city” looked forward to the start of the New-York Flower Mission’s season in 1878, explaining to Harper’s Weekly that “surgical operations were more successful on the flower days.” Writers for Harper’s Weekly and the New York Times did not require an explanation of how the fragrances aided surgery. The benefit of flowers was as obvious as that of day excursions to the shore or mountains: a change of air improved health.36

FIGURE 6.4. The middle-class women of Flower Missions assembled bouquets of colorful and fragrant flowers to distribute as philanthropy to the residents of tenements, prisons, and hospitals. In the popular understanding of good smells and health, the charities were distributing disinfectants to improve some of the worst air in cities. “The Flower Mission—Making Bouquets for Hospitals and Prisons,” Harper’s Weekly, July 28, 1877, 590. Reproduced with the permission of the Pennsylvania State University Libraries.

Accounts of the New-York Flower Mission indicate that the charity’s recipients did not simply want colorful flowers; the poor, infirm, and incarcerated desired good smells. As the Flower Mission interacted with its beneficiaries, it updated its donation requests to meet the desires of the poor. An 1879 profile of the charity in the New York Times noted that, “while all flowers are gladly received, the most acceptable have proved to be lilacs, laurel, pond lilies, roses, pinks, and sweet geranium.” Middle-class women joined the mission to put their floral-arranging skills to productive use outside the home, and they were careful to include both “a sweet-scented and bright-colored flower” in each bouquet. For the recipients, fragrant blooms not only promised health but also triggered memories of better times in better places: “More than once, some wasted, hollow-eyed creature has smiled at the bunch of wild flowers handed her, saying feebly, ‘They bring back the fields—I was a country girl, Miss!’” Just as the flowers brought the scents of health into foul urban spaces, the fragrances mentally transported recipients to the supposedly healthier countryside, thereby conveying both physical and psychological comfort.37

Domestic practices and technologies after germ theory blended old beliefs about smells with new knowledge of germs and microbes. When scientific research demonstrated the efficacy of ozone as a disinfectant that would kill germs, many interpreted the science as also validating olfactory practices that diffused pleasant fragrance throughout the home. Women paired airing to admit ozone with the long-standing use of potpourri, as author Annie Marie advised readers of the Ladies’ Floral Cabinet in 1884: “Every week after the usual sweeping, dusting and airing, open your [potpourri] jar and shake the contents thoroughly; this will give your room a delicate perfume.” Similarly, women justified the fragrant sachets that they had tucked into closets and bureaus before the Civil War in new, scientific terms. In 1896, the Ladies’ World published an enthusiastic account of “special sachets capable of diffusing certain perfumes that are disinfective.” These sachets contained two sheets of paper, one of which was saturated with perfume and “oxalosaccharic acid,” and another contained “dry bicarbonate of soda.” When the sachet was moistened, the acid and soda would react to fight a familiar foe, carbonic acid gas, and release a familiar sweet scent. Thus the special sachets combined new scientific ideas of disinfection with time-honored methods of improving the air: “The result is carbonic acid gas is liberated and diffuses the odor about the room and saturates it with a fragrant medium which disinfects the air.” In practices such as these, women continued to manage the domestic environment by merging miasmatic concerns about foul air with the new knowledge of germs.38

Before the discovery of microbes, physicians and commentators wondered if all bad odors caused illness, but they could not answer that question conclusively. Nonetheless, they agreed that concentrated odors were noxious, a conclusion that the Civil War experience with stench and disease bolstered, and directed their attention to the spaces that concentrated odors, such as the home. This shift ostensibly brought men and women into conversation about domestic environs, but the conversation was selective and uneven. While physicians became health authorities and circulated new knowledge about disinfectants and the dangers of defective plumbing, women incorporated this information in their domestic guides with caveats and recommendations specific to the home.

The experiences of women and physicians with health and the household led to a number of innovative ideas and practices between the Civil War and the final decade of the nineteenth century. These ideas did not reject the logic and accepted knowledge of miasma theory outright but began a gradual shift away from the belief that foul odors directly harmed health. In the course of this cultural shift, women and physicians exchanged ideas about the definition and best use of disinfectants, pondered the ways in which plumbing threatened health, and found new ways to use the sense of smell to identify health hazards. Concentrated odors continued to worry Americans, who opened windows after using smelly disinfectants in their homes and feared the accumulation of foul air in any space.

Although ideas about bad smells began to change, the belief that fresh air was healthful remained powerful in both medical wisdom and popular culture. Through their use of disinfectants, both physicians and women expanded their definition of fresh air. While they still preferred the fresh air that John Hoskins Griscom had touted, produced by air movement across open spaces and not yet breathed, Americans also replicated the benefits of fresh air through chemical disinfectants, called fresh air itself a disinfectant, and, after the discovery of ozone, thought they could create fresh air in any space by generating ozone. In a feedback loop, these ideas about fresh air reinforced practices that deployed good smells, such as those of fragrant plants, perfumed sachets, and potpourri, for good health.

These ideas about good and bad smells also lingered because germ theory did not explain all the causes of illness in the late nineteenth century. The sources of yellow fever and malaria remained unknown until the end of the century, as did the causes of the diarrhea, nausea, headaches, fevers, and vomiting that constituted ill health and conjured fear in many homes. As men and women continued to suffer from these physical ailments, they blended new scientific knowledge with trusted domestic practices to protect health. Thus in everyday life, Americans continue to heed their noses, detect smells, and evaluate the healthfulness of their environs. Germ theory alone did not change how Americans thought about the air they breathed. Instead, the courtrooms and proceedings of health boards in the 1870s and 1880s changed meanings of and discussions about olfaction.