Appendix 2

The Carpathian Language

Like all human languages, the language of the Carpathians contains the richness and nuance that can only come from a long history of use. At best we can only touch on some of the main features of the language in this brief appendix:

- The history of the Carpathian language

- Carpathian grammar and other characteristics of the language

- Examples of the Carpathian language

- A much abridged Carpathian dictionary

1. The history of the Carpathian language

The Carpathian language of today is essentially identical to the Carpathian language of thousands of years ago. A “dead” language like the Latin of two thousand years ago has evolved into a significantly different modern language (Italian) because of countless generations of speakers and great historical fluctuations. In contrast, many of the speakers of Carpathian from thousands of years ago are still alive. Their presence—coupled with the deliberate isolation of the Carpathians from the other major forces of change in the world—has acted (and continues to act) as a stabilizing force that has preserved the integrity of the language over the centuries. Carpathian culture has also acted as a stabilizing force. For instance, the Ritual Words, the various healing chants (see Appendix 1), and other cultural artifacts have been passed down the centuries with great fidelity.

One small exception should be noted: the splintering of the Carpathians into separate geographic regions has led to some minor dialectization. However the telepathic links among all Carpathians (as well as each Carpathian’s regular return to his or her homeland) has ensured that the differences among dialects are relatively superficial (e.g., small numbers of new words, minor differences in pronunciation, etc.), since the deeper, internal language of mind-forms has remained the same because of continuous use across space and time.

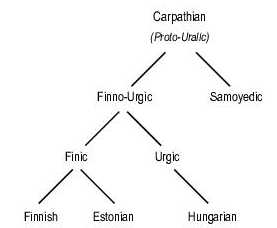

The Carpathian language was (and still is) the proto-language for the Uralic (or Finno-Ugrian) family of languages. Today, the Uralic languages are spoken in northern, eastern and central Europe and in Siberia. More than twenty-three million people in the world speak languages that can trace their ancestry to Carpathian. Magyar or Hungarian (about fourteen million speakers), Finnish (about five million speakers), and Estonian (about one million speakers), are the three major contemporary descendents of this proto-language. The only factor that unites the more than twenty languages in the Uralic family is that their ancestry can be traced back to a common proto-language—Carpathian—which split (starting some six thousand years ago) into the various languages in the Uralic family. In the same way, European languages such as English and French, belong to the better-known Indo-European family and also evolve from a common proto-language ancestor (a different one from Carpathian).

The following table provides a sense for some of the similarities in the language family.

Note: The Finnic/Carpathian “k” shows up often as Hungarian “h”. Similarly, the Finnic/Carpathian “p” often corresponds to the Hungarian “f.”

2. Carpathian grammar and other characteristics of the language

Idioms. As both an ancient language, and a language of an earth people, Carpathian is more inclined toward use of idioms constructed from concrete, “earthy” terms, rather than abstractions. For instance, our modern abstraction, “to cherish,” is expressed more concretely in Carpathian as “to hold in one’s heart”; the “nether world” is, in Carpathian, “the land of night, fog, and ghosts”; etc.

Word order. The order of words in a sentence is determined not by syntactic roles (like subject, verb, and object) but rather by pragmatic, discourse-driven factors. Examples: “Tied vagyok.” (“Yours am I.”); “Sívamet andam.” (“My heart I give you.”)

Agglutination. The Carpathian language is agglutinative; that is, longer words are constructed from smaller components. An agglutinating language uses suffixes or prefixes whose meaning is generally unique, and which are concatenated one after another without overlap. In Carpathian, words typically consist of a stem that is followed by one or more suffixes. For example, “sívambam” derives from the stem “sív” (“heart”) followed by “am” (“my,” making it “my heart”), followed by “bam” (“in,” making it “in my heart”). As you might imagine, agglutination in Carpathian can sometimes produce very long words, or words that are very difficult to pronounce. Vowels often get inserted between suffixes, to prevent too many consonants from appearing in a row (which can make the word unpronouncable).

Noun cases. Like all languages, Carpathian has many noun cases; the same noun will be “spelled” differently depending on its role in the sentence. Some of the noun cases include: nominative (when the noun is the subject of the sentence), accusative (when the noun is a direct object of the verb), dative (indirect object), genitive (or possessive), instrumental, final, supressive, inessive, elative, terminative, and delative.

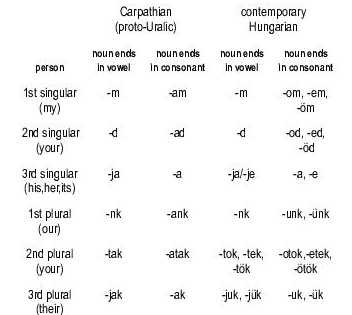

We will use the possessive (or genitive) case as an example, to illustrate how all noun cases in Carpathian involve adding standard suffixes to the noun stems. Thus expressing possession in Carpathian—“my lifemate,” “your lifemate,” “his lifemate,” “her lifemate,” etc.—involves adding a particular suffix (such as “=am”) to the noun stem (“päläfertiil”), to produce the possessive (“päläfertiilam”—“my lifemate”). Which suffix to use depends upon which person (“my,” “your,” “his,” etc.) and whether the noun ends in a consonant or vowel. The following table shows the suffixes for singular nouns only (not plural), and also shows the similarity to the suffixes used in contemporary Hungarian. (Hungarian is actually a little more complex, in that it also requires “vowel rhyming”: which suffix to use also depends on the last vowel in the noun; hence the multiple choices in the cells below, where Carpathian only has a single choice.)

Note: As mentioned earlier, vowels often get inserted between the word and its suffix so as to prevent too many consonants from appearing in a row (which would produce unpronouncable words). For example, in the table above, all nouns that end in a consonant are followed by suffixes beginning with “a.”

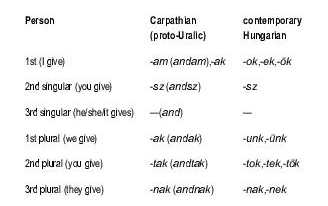

Verb conjugation. Like its modern descendents (such as Finnish and Hungarian), Carpathian has many verb tenses, far too many to describe here. We will just focus on the conjugation of the present tense. Again, we will place contemporary Hungarian side by side with the Carpathian, because of the marked similarity of the two.

As with the possessive case for nouns, the conjugation of verbs is done by adding a suffix onto the verb stem:

As with all languages, there are many “irregular verbs” in Carpathian that don’t exactly fit this pattern. But the above table is still a useful guideline for most verbs.

3. Examples of the Carpathian language

Here are some brief examples of conversational Carpathian, used in the Dark books. We include the literal translation in square brackets. It is interestingly different from the most appropriate English translation.

Susu.

I am home.

[“home/birthplace.” “I am” is understood, as is often the case in Carpathian.]

Möért?

What for?

csitri

little one

[“little slip of a thing”, “little slip of a girl”]

ainaak enyém

forever mine

ainaak sívamet jutta

forever mine (another form)

[“forever to-my-heart connected/fixed”]

sívamet

my love

[“of-my-heart,” “to-my-heart”]

Sarna Rituaali (The Ritual Words) is a longer example, and an example of chanted rather than conversational Carpathian. Note the recurring use of “andam” (“I give”), to give the chant musicality and force through repetition.

Sarna Rituaali (The Ritual Words)

Te avio päläfertiilam.

You are my lifemate.

[You wedded wife-my. “Are” is understood, as is generally the case in Carpathian when one thing is equated with another: “You-my lifemate.”]

Éntölam kuulua, avio päläfertiilam.

I claim you as my lifemate.

[To-me belong-you, wedded wife-my.]

Ted kuuluak, kacad, kojed.

I belong to you.

[To-you belong-I, lover-your, man/husband/drone-your.]

Élidamet andam.

I offer my life for you.

[Life-my give-I. “you” is understood.]

Pesämet andam.

I give you my protection.

[Nest-my give-I]

Uskolfertiilamet andam.

I give you my allegiance.

[Fidelity-my give-I.]

Sívamet andam.

I give you my heart.

[Heart-my give-I.]

Sielamet andam.

I give you my soul.

[Soul-my give-I.]

Ainamet andam.

I give you my body.

[Body-my give-I.]

Sívamet kuuluak kaik että a ted.

I take into my keeping the same that is yours.

[To-my-heart hold-I all that-is yours.]

Ainaak olenszal sívambin.

Your life will be cherished by me for all my time.

[Forever will-be-you in-my-heart.]

Te élidet ainaak pide minan.

Your life will be placed above my own for all time.

[Your life forever above mine.]

Te avio päläfertiilam.

You are my lifemate.

[You wedded wife-my.]

Ainaak sívamet jutta oleny.

You are bound to me for all eternity.

[Forever to-my-heart connected are-you.]

Ainaak terád vigyázak.

You are always in my care.

[Forever you I-take-care-of.]

See Appendix 1 for Carpathian healing chants, including both the Kepä Sarna Pus (“The Lesser Healing Chant”) and the En Sarna Pus (“The Great Healing Chant”).

To hear these words pronounced (and for more about Carpathian pronunciation altogether), please visit: http://www.christinefeehan.com/members/

4. A much abridged Carpathian dictionary

This very much abridged Carpathian dictionary contains most of the Carpathian words used in these Dark books. Of course, a full Carpathian dictionary would be as large as the usual dictionary for an entire language.

Note: The Carpathian nouns and verbs below are word stems. They generally do not appear in their isolated, “stem” form, as below. Instead, they usually appear with suffixes (e.g., “andam”—“I give,” rather than just the root, “and”).

aina—body

ainaak—forever

akarat—mind; will

ál—bless, attach to

alatt—through

ale—to lift; to raise

and—to give

avaa—to open

avio—wedded

avio päläfertiil—lifemate

belso—within; inside

ćaδa—to flee; to run; to escape

ćoro—to flow; to run like rain

csitri—little one (female)

ekä—brother

elä—to live

elävä—alive

elävä ainak majaknak—land of the living

elid—life

én—I

en—great, many, big

En Puwe—The Great Tree. Related to the legends of Ygddrasil, the axis mundi, Mount Meru, heaven and hell, etc.

engem—me

eći—to fall

ek—suffix added after a noun ending in a consonant to make it plural

és—and

että—that

fáz—to feel cold or chilly

fertiil—fertile one

fesztelen—airy

fü—herbs; grass

gond—care; worry (noun)

hän—he; she; it

hany—clod; lump of earth

irgalom—compassion; pity; mercy

jälleen—again.

jama—to be sick, wounded, or dying; to be near death (verb)

jelä—sunlight; day, sun; light

joma—to be under way; to go

jorem—to forget; to lose one’s way; to make a mistake

juta—to go; to wander

jüti—night; evening

jutta—connected; fixed (adj.). to connect; to fix; to bind (verb)

k—suffix added after a noun ending in a vowel to make it plural

kaca—male lover

kaik—all (noun)

kana—to call; to invite; to request; to beg

kank—windpipe; Adam’s apple; throat

Karpatii—Carpathian

käsi—hand

kepä—lesser, small, easy, few

kinn—out; outdoors; outside; without

kinta—fog, mist, smoke

koje—man; husband; drone

kola—to die

koma—empty hand; bare hand; palm of the hand; hollow of the hand.

kont—warrior

kule—hear

kuly—intestinal worm; tapeworm; demon who possesses and devours souls

kulke—to go or to travel (on land or water)

ku a—to lie as if asleep; to close or cover the eyes in a game of hide-and-seek; to die

a—to lie as if asleep; to close or cover the eyes in a game of hide-and-seek; to die

kunta—band, clan, tribe, family

kuulua—to belong; to hold

lamti—lowland; meadow

lamti ból jüti, kinta, ja szelem—the nether world (literally: “the meadow of night, mists, and ghosts”)

lejkka—crack, fissure, split (noun). To cut ø hit; to strike forcefully (verb).

lewl—spirit

lewl ma—the other world (literally: “spirit land”). Lewlma includes lamti ból jüti, kinta, ja szelem: the nether world, but also includes the worlds higher up En Puwe, the Great Tree

löyly—breath; steam. (related to lewl: “spirit”)

ma—land; forest

mäne—rescue; save

me—we

meke—deed; work (noun). To do; to make; to work (verb)

minan—mine

minden—every, all (adj.).

möért?—what for? (exclamation)

molo—to crush; to break into bits

molanâ—to crumble; to fall apart

mozdul—to begin to move, to enter into movement

nä—for

naman—this; this one here

nélkül—without

nenä—anger

nó—like; in the same way as; as

numa—god; sky; top; upper part; highest (related to the English word: “numinous”)

nyelv—tongue

nyál—saliva; spit (noun). (related to nyelv: “tongue”)

odam—dream; sleep (verb)

oma—old; ancient

omboće—other; second (adj.)

o—the (used before a noun beginning with a consonant)

ot—the (used before a noun beginning with a vowel)

otti—to look; to see; to find

owe—door

pajna—to press

pälä—half; side

päläfertiil—mate or wife

pél—to be afraid; to be scared of

pesä—nest (literal); protection (figurative)

pide—above

pirä—circle; ring (noun). To surround; to enclose (verb).

pitä—keep, hold

piwtä—to follow; to follow the track of game

pukta—to drive away; to persecute; to put to flight

pusm—to be restored to health

pus—healthy; healing

puwe—tree; wood

reka—ecstasy; trance

rituaali—ritual

saγe—to arrive; to come; to reach

salama—lightning; lightning bolt

sarna—words; speech; magic incantation (noun). To chant; to sing; to celebrate (verb)

aro—frozen snow

aro—frozen snow

siel—soul

sisar—sister

sív—heart

sívdobbanás—heartbeat

sone—to enter; to penetrate; to compensate; to replace

susu—home; birthplace (noun). at home (adv.)

szabadon—freely

szelem—ghost

tappa—to dance; to stamp with the feet (verb)

te—you

ted—yours

toja—to bend; to bow; to break

toro—to fight; to quarrel

tule—to meet; to come

türe—full, satiated, accomplished

tyvi—stem; base; trunk

uskol—faithful

uskolfertiil—allegiance

veri—blood

vigyáz—to care for; to take care of

vii—last; at last; finally

wäke—power

wara—bird; crow

we ća—complete; whole

ća—complete; whole

wete—water