TWO

Rachel Random

‘She has a bold stride,’ said Holmes, looking down at the street through our large front window. ‘I can hardly believe she is the sort of a woman who would resort to killing herself with sleeping tablets and pain pills.’

‘Do you presume to plumb her character from a second-storey glimpse?’ I said.

‘Idle speculation,’ he replied, with a laugh.

‘And what else do you dare deduce from this distance?’

He slipped his hands into his pockets as he gazed down. ‘Very little.’

‘I am relieved,’ I said.

‘All that is certain,’ he said, ‘is that she plays squash, is a serious cyclist, reads voraciously, is fond of dogs, allows herself to be pampered by men, is left-handed, and has recently travelled to the continent.’

‘You frighten me, Holmes.’

‘All quite obvious,’ he replied.

The bell rang. A moment later Percy Ffoulkes and a striking young redhead stood framed in our doorway. The woman immediately introduced herself as Rachel Random. I hung her stylish mauve coat on the coat tree, and I draped Percy’s blue wool topcoat and white scarf next to it. He was still the same good-looking, compact, energetic and affable fellow that he had been in the old days at university – the sort of chap people find immediately attractive. This evening he seemed subdued as he handed me a package. ‘A small gift of brandy, James. Bought it at auction several years ago. Hope you like it.’

‘My heavens,’ I said, looking at the label. ‘It’s a hundred years old, isn’t it?’

‘About that.’ He swept the air with the back of his hand as if to brush away my reluctance to accept so lavish a gift.

I set the bottle on the side table, carefully.

As my old friend and his niece walked in to meet Holmes, they struck me as a most handsome couple – perfectly matched in style and manner. He was sixty-two, she perhaps thirty-five. We all sat down by the dancing hearth, and their faces shone with excitement and concern.

‘Mr Holmes, I am sorry to impose on you so late in the evening,’ said Percy. ‘I rather desperately need your help, and that is my only excuse.’

‘You need no excuse,’ said Holmes. ‘Had you not introduced me to Wilson last autumn in Wales – at that critical moment when I was recuperating from years in the glacier, and he from Afghanistan’s wounds – I fear I would have had difficult days. Your old friend has helped me restart my career, and consequently I am very much in your debt.’

‘What a terrible tangle that Black Priest affair was!’ said Percy. ‘I followed it in the newspapers. You are to be congratulated for handling it so subtly, Mr Holmes.’

‘It was my first murder case in more than ninety years,’ he replied, ‘and solving it was a pleasure. But since then my services have been in very small demand.’ His eyes were alight with expectation. ‘But, please, be good enough to tell us what brings you to see me this evening.’

‘My niece and I have become entangled in a most unusual crime,’ said Percy. ‘I certainly hope matters can be set right.’

‘Pray give me the details,’ urged Holmes.

‘The long and the short of it, Mr Holmes, is that a letter has been stolen – a letter written and signed by William Shakespeare.’

Holmes lurched a little in his chair.

I too was startled.

‘I know how improbable my tale must sound,’ said Percy. ‘Apart from a few signatures on legal documents, nothing handwritten by William Shakespeare has ever been discovered – not a single letter, script or poem in four hundred years. Nothing. But several months ago a good friend of mine, Professor Hugh Blake of Oxford, confided to me that he had discovered a letter written and signed by Shakespeare. It was purportedly composed in Florence in March of 1592, and it was addressed to a woman named Emilia. Everything about the document appeared to Hugh to be perfectly genuine. But he felt he could not so much as whisper of his discovery until he was absolutely certain of the letter’s authenticity. He told no one but his wife and me. He felt he simply could not present to his peers a letter that would rock the foundations of scholarship and put the whole civilized earth in an uproar if there were any chance that it might prove to be a fake.’

‘Quite so, quite so,’ said Holmes.

‘Sir Hugh found the letter in a pile of papers at an art dealer’s shop in Florence, and purchased it for a song. When he got back to England he closeted himself at his manor in the Cotswolds and did everything in his power to ascertain the letter’s authenticity in absolute secrecy. He had the paper analysed in a laboratory. The paper was found to have been made in Italy in the late sixteenth century. He thoroughly analysed the contents of the letter, including the words used, the spellings, the subjects alluded to, the people and places mentioned in it, and so forth. He then checked his own judgement – without ever revealing the existence of the letter – with that of Shakespeare scholars around the world, asking them a number of questions. Their answers all suggested that the letter was one which Shakespeare certainly could have written. A month ago Sir Hugh came to the point when he could do no more to verify the authenticity of the letter without actually revealing its existence to the scholarly community – revealing it, that is, to the scrutiny of all those experts worldwide who will, quite naturally, be anxious to examine it. But Hugh is a worrier. Even at school – we were at Oxford together – he was a worrier. I suggested to him that he might consider, as one last precaution, submitting the letter to my niece. I told him that Rachel has worked for two major auction houses, is an expert in holograph letters, and now works for a firm in New Bond Street that specializes in authenticating documents of all kinds. I assured him that she, in strictest secrecy, would match the writing of the letter to Shakespeare’s known signatures, analyse the ink, and perform a number of other forensic tests to help determine if the letter is what it pretends to be. Hugh agreed that this would be a good idea. Seven days ago he brought the letter to Lashings and Bedrock, Ltd, in New Bond Street, and turned it over to my niece. And that is where the trouble began. This affair has caused my niece so much consternation that for a while I really believed she had tried to commit suicide with a cocktail of sleeping pills and pain pills—’

‘But that wasn’t it at all,’ broke in Rachel Random. ‘I certainly did not try to kill myself!’

She had been sitting very straight in her chair, listening intently as her uncle spoke. She was a statuesque young woman with very red hair and very green eyes. Her skin was smooth as soap, and it was exceptionally white, except for a few freckles on the nose. She gave an impression of boldness. Yet she exuded such femininity, particularly when she spoke, that the impression of boldness was diluted. She gave the immediate impression of being exceptionally beautiful – an impression no doubt enhanced by the fact that she was wrapped in a tight-fitting green dress. I felt, at first, that her face was as beautiful as that of any cover girl. Then I realized that this was not so, that the nose was a little too prominent, and that much of her beauty came from the animation of her face and the energy of her moods.

‘I admit I had a little too much wine on the night after the letter was stolen,’ she said. ‘As a result, I forgot which medications I had already taken. I had injured my wrist playing squash, and I took a pain pill for that. Then I took a sleeping pill to get some rest. But evidently I took each dose twice, or three times, and that made me very sick.’

‘Gave us all a scare,’ said Percy.

‘I suppose I ought to tell you exactly what happened, Mr Holmes,’ she said.

‘Pray do so, and omit no details.’ said Holmes. He sat in a state of utter quiescence and concentration, his wrists limp and thin hands falling bent over the ends of the chair arms. ‘Even the most seemingly inconsequential detail can sometimes be crucial in the solution of a case.’

‘I will do my best to omit nothing,’ she said. ‘Exactly one week ago today my uncle Percy phoned me and said that a friend of his would soon contact me about a very important matter. My uncle asked me to do everything in my power to accommodate his friend’s needs. A little later that day Sir Hugh Blake phoned and informed me that he had an old letter that might be of very great importance. He asked if I would be willing to examine it. We made an appointment for that very afternoon, and at exactly four thirty he stepped into my office. When I closed the door he informed me, in hushed tones, that he believed he had a letter in his hand that had been written by William Shakespeare. I dare say, you could have knocked me off my chair by simply blowing at me. I knew Professor Blake had a worldwide reputation as a Shakespeare scholar. If anyone else had made this claim to my face, I might have laughed out loud – or at least smiled. But in this case, I could only try to keep my pulse rate down. The letter was in an envelope about eight and a half inches long and five and a half inches wide. I drew the letter out very carefully, laid it on my table, unfolded it, and cast my eye over it. To my casual glance everything looked perfectly authentic. But, of course, many further tests would be required before I could say anything definite. Nonetheless, I suddenly felt as though I were handling a holy relic. I carefully slipped the letter back into its envelope and laid it on the table. Professor Blake and I talked a little longer. He told me nothing further about the letter I was to examine, neither its provenance nor what tests it had already been subjected to. He stood up and shook my hand, and he said, “Please take good care of it.” And at about ten minutes past five o’clock Sir Hugh left my office. From my office door I could see him go towards the elevator. I presume he got into the elevator and left the building.’

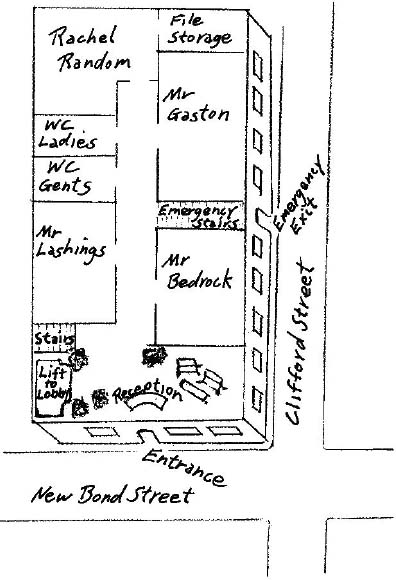

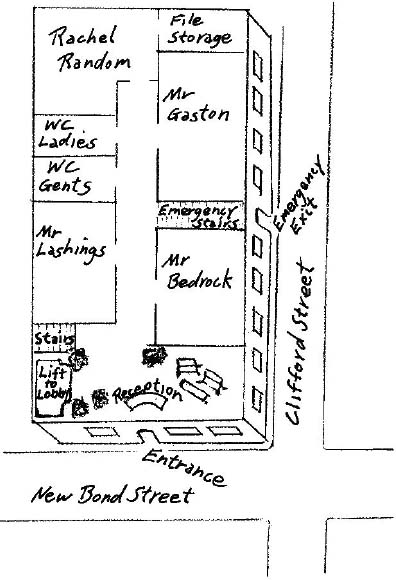

Rachel Random paused in her narrative, leant forward, and drew something out of her purse. ‘I thought this might help you to visualize our building, Mr Holmes. It is a little sketch I made of our office layout.’

‘You are very thorough,’ said Holmes, taking the foolscap sheet.

‘It is my job to be thorough,’ she replied. ‘When Sir Hugh Blake left, there were just three of us remaining in the building: Paul, our receptionist; Mr Gaston, whose office is nearest mine; and me. Mr Lashings had already left, and Mr Bedrock had not come to work that day for he was on holiday in Spain.’

‘What happened next?’

‘I sat down at my desk and ate a sandwich left over from my lunch. I felt the most urgent need to look at the letter and determine whether it was real. At the same time I was reluctant to begin – perhaps for fear of what I’d find. I was in a very strange state of mind, Mr Holmes. After having boosted my energy with the sandwich and a pickle, I decided I would freshen up and begin work immediately. I left the Shakespeare letter in its envelope on the table where Sir Hugh and I had been looking at it. I stepped out of my office and went into the WC just next door.’

‘Did you lock your office when you went to the WC?’ asked Holmes.

‘No. I didn’t even close the door. I presumed the letter was perfectly safe in its anonymous manila envelope on my table, especially since no one but me, my uncle, Sir Hugh and his wife even knew of its existence.’

‘That makes sense,’ Holmes nodded. ‘And then?’

‘I had been in the WC for perhaps a minute and a half, and I had just turned on the water faucet when I heard a terrible shout. I rushed into the hallway but saw nothing. I heard a clatter of footsteps, then heard Paul’s voice shouting “Stop!” from the emergency staircase that leads down to Clifford Street. A moment later the emergency door alarm went off. A few moments after that Mr Gaston’s head appeared in his doorway. “What’s going on?” Mr Gaston asked. Paul soon emerged from the emergency stairwell and cried, “Someone just ran out of the building.” He looked rather distracted and wild, and he said to me, “Who was in your office, Rachel?”

‘“No one,” I answered.

‘But already a cold feeling had come over me, Mr Holmes. Already I seemed to know what had happened. I hurried to my office and looked on the table: the envelope containing the letter was gone. I searched the desk and the floor behind the desk, thinking it might have fallen. I could not believe it had vanished. And yet from the moment the alarm sounded I knew perfectly well that the Shakespeare letter was gone, stolen – gone before I had kept it in my care for even half an hour. You cannot imagine how I felt, Mr Holmes! How I feel!’

Rachel Random stopped speaking. She looked shaken. I felt sorry for her.

‘What made Paul think someone had been in your office?’ asked Holmes.

‘The sound of footsteps,’ she said. ‘Paul usually does not stay after hours, but this night he stayed late to catch up on some filing. He found a file that I had asked for earlier in the day, and he brought it to my office – just at the time I was in the WC. But when he tossed it on to the desk top, it slid right off on to the floor behind. So he knelt down and collected the papers that had slid out of the file folder. At that moment he heard a sound behind him, someone hurrying out the door. Paul got up and ran across the room into the hallway. He saw no one, but he heard footsteps rushing down the emergency exit staircase. So he hurried to the staircase and chased whoever it was. As he went around the first turning he heard the outer door open somewhere below him – and then the alarm went off. When Paul reached the bottom of the stairs he looked out the door in hopes of seeing someone running, but he saw only the usual street crowds flowing by. So he closed the door and came back up. That’s when he met me and Mr Gaston in the hallway, and told us what had happened.’

‘Why was Mr Gaston there after hours?’ asked Holmes.

‘He comes to work a bit later than the rest of us, and so he always stays until five forty-five.’

‘Did you call the police?’

‘Immediately. Detectives very soon arrived. I put on my coat and went with one of them to headquarters at New Scotland Yard, where I told him everything I have told you.’

‘And nothing has been learnt of the letter since it vanished a week ago?’

‘Nothing that I know of. I suppose the police are working on it.’

Holmes sprang to his feet and stood in front of the fire, looking at the plan of the office that she had given him. ‘According to your diagram, the storage room can be entered only through your office. Could someone have been hiding there?’

‘Not possible. I went into that room for a pad of paper at four o’clock or so. No one was there. Besides, I can’t imagine how a stranger would get into the building. The only entrance is through the front, and someone is at the desk all the time. Mr Bedrock is very particular about security. Important books, manuscripts and documents are always on the premises.’

Holmes walked to the window and looked out at the square. ‘The case has some singular and, indeed, startling features,’ he said. ‘Will you be at your office tomorrow, Ms Random?’

‘Eight to five,’ said she.

She and Percy rose. As I helped Rachel into her stylish coat, she turned to me suddenly and said, ‘A month ago I was on a motoring holiday in Germany and everything seemed perfect – isn’t it strange how quickly fortune changes!’

Percy touched her arm. ‘Never worry, my dear. Mr Holmes will take care of everything – depend upon it!’

‘I have every confidence,’ she said. Again she turned to me. ‘Who is that lovely old lady I met out front, with the two poodles? Luckily, I always carry dog biscuits for such meetings!’

‘That would be Mrs Cleary,’ I said. ‘She lives in the ground floor flat beneath us.’

‘Good night, Mr Wilson – and thank you, Mr Holmes,’ she said.

When they had left I walked to the front window and looked down. Rachel Random had parked her bright red car beneath the streetlamp. Her uncle opened the driver’s door for her. Very clearly on the rear window shelf I could see a scattering of books . . . and a squash racquet in its case. The car was this year’s model. It had a GB sticker on the back, which of course suggested she had driven it abroad. Standing up in the rack on top was a road bicycle. ‘I am beginning to learn your methods, Holmes,’ I said.

Long after our guests had left us, Holmes still paced about, revved by the fuel of this seemingly inexplicable crime. I almost hoped he would not solve it too quickly. He was more cheerful than I’d seen him in weeks.

Before we retired, I opened the old bottle of brandy that Percy had brought, and I poured us each a small splash. I toasted Holmes and wished him success in his search for the Shakespeare letter. He sipped the brandy, and smiled with pleasure at the first sip. Then he put the brandy glass to his nose, sniffed it curiously. A haunted look crept into his eyes.

‘How do you like it?’ I asked.

He did not answer.

‘Are you all right, my good fellow?’

Holmes leapt from his chair and pointed out the window. ‘Look out! It’s coming!’ he cried.

‘Holmes!’ I said.

But he did not hear me. He was staring out the window into the emptiness of night, with a look of fear on his face.