11

Jumpin Jack Frost

JUMPIN Jack Frost always seemed like the archetypal jungle DJ to me. Others might be slicker, more high-tech, more full of tricks to rock the party, he was the one you could trust to roll it out, as the popular junglist phrase went. His sets combined deranged dancehall edge, wild breakbeat cascade and extended peak sensation, with a reliable funk / soul groove undercurrent. And they just kept going and going, exactly between chaos and control. Plus he looked imposing – he who could walk into the most ravaged rave and the crowd would part. And listening back to the mixtapes my schoolfriends had amassed, I realised he'd been an amazing talent right through the rave era.

His one release as an artist (the dancefloor classic Leviticus ‘The Burial’, a dubplate staple from 1993, released in 1994) is really a work of DJing too. Where so much else in emergent jungle was about micro-edits and processing of the breaks and bass, he continued the hardcore tradition of records as a perfectly matched set of samples. In ‘The Burial’ these were selected and directed by Frost, and then assembled in the studio by Dillinja, deeply cementing jungle as much in the traditions of rare groove, dancehall, lovers rock and street soul as in rave or techno. And as jungle furiously mutated into drum’n’bass, Frost's (with his creative partner Bryan Gee's) curation made him one of the greatest label bosses. His V and Philly Blunt labels launched Bristolians Krust, Roni Size, Die and Suv, and gave early platforms to Ed Rush, Optical and Adam F.

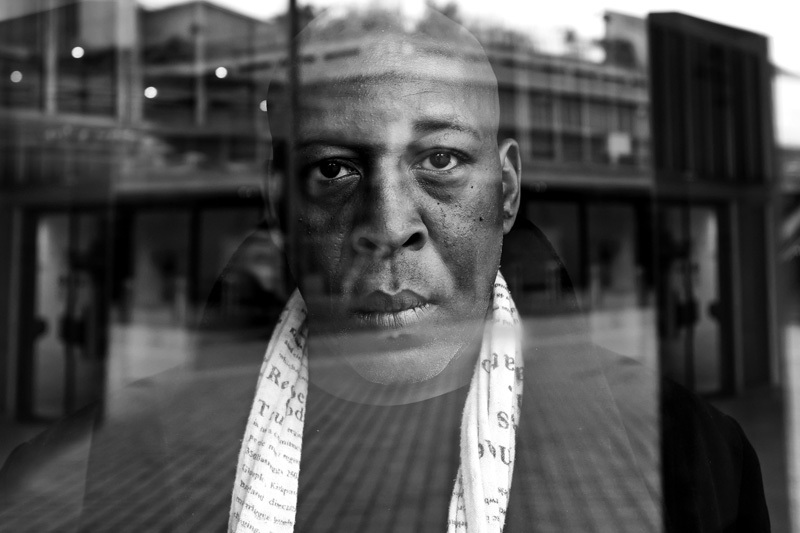

The early releases on those labels still stand up as classics, but Frost has never stood still. Once he tied his fate to drum’n’bass, he remained utterly faithful to it, rolling out the beats globally, whatever the ebbs and flows of scene politics. Around the millennium, he stood out for me as someone who appreciated a heads-down rave-up: still on the global d’n’b circuit, he remained good friends with Brighton crusty ravers of my acquaintance, and would join their tear-ups in the Volks Tavern, a little sweatbox in the seafront arches. Meeting him for this interview in the Royal Festival Hall foyer, there was something about his demeanour that made absolute sense, given his continual, unchanging presence as a rave trouper. Something about Nigel Thompson seems carved out of stone, as implacably focused and indomitable as the beats he continues to roll out.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in St Stephens Hospital in what's now Chelsea and Westminster, May 29, 1967. My first four to five years I lived in Chelsea, then we moved to Brixton, where I lived up until recently.

What was your family background?

Both my mum and dad are both Guyanese, and so's my grandmother obviously. She came here with my mum, and my mum went to school here. My Dad came a bit later.

What were your interests at school?

I was a football fanatic, I support Manchester United, I have done since 1976. I went to Tulse Hill boys, which isn't there anymore. I was a bit of a tearaway, got into trouble a lot, got expelled, and went to a school that was quite smart. My mum and the government paid half each, as it was a boarding school. I was quite well educated, I learnt a lot about myself. The average kid at a London comprehensive, 30 plus boys in a class., won't get that much attention. In my school we had five boys in every class, so it was very hands on.

And what was the social mix?

It was pretty much well mixed. It was in Newbury, Berkshire, and it was a culture shock for me because there were no black people in the area. I remember we were right near Greenham Common, with all the women. We used to drive past there and we had women chained to the fence and protesting about the cruise missiles at the time. A pretty unique way to grow up.

What were you into culturally?

Once I was 12 or 13 years old I used to go to Jah Shaka. I used to go out raving since I was young. Kids were more trusted then to go out and roam the streets. Not like now.

There was more space for kids to play in the 70s, half of London was still derelict

Yeah do you known what I mean? We used to have wild packs of dogs running around, stuff like that, you don't see that now. But yeah, I was really into Jah Shaka, Jah Shaka and dub. Sounds like Mount Zion, Stereograph, Nasty Rockers, Small Axe, Dread Diamonds, Frontline International, Sir Coxsone.95 That was me at that age. And from then, more dancehall stuff – that's how it all started off for me.

You mentioned the gang culture…

Me and my friends used to go around and rob parties, big parties – it wasn't very nice, y’know what I mean? I was a bit of a bad kid and um, yeah [laughs]. It was fun but it wasn't very nice.

And at what point did you start getting involved with music?

I used to go to the Africa Centre on Sundays. No, first of all I started going to Electric Ballroom [in Camden] and it was there I got really interested in the music and what records was being played. There was funk and hip hop and stuff, and I was like “This is alright!” I gravitated to it. We used to go up there as a gang, but I just started to get into it. All my boys were like, “Yeah we've come to rob people” but I started thinking “No, wait, I like this music!” So I started breaking away and going up on my own, and meeting people and getting into it. And then I started going to Soul II Soul at the Africa Centre and got to know Jazzie B really well.

When did that start?

This must have been around 1985, meeting Jazzie, meeting Trevor Nelson. They kind of took to me and I learnt a lot of stuff from them, know what I mean? Just watching and observing. Then I started wanting to play music myself! So I started collecting a lot of rare groove, a large amount of records in a short space of time. I was just very good at getting all the right records and it became an obsession. Then just as I was getting into that mode of DJing, I went to this Acid House party in Clink Street, London Bridge, my first one. And I got hooked, just like that.

That whole Soul II Soul warehouse party thing, just before acid house arrived, did it feel it was something particularly British? I mean up to then, the influences were Jamaican or American, dub and dancehall or funk and hip hop

It was. It was really good culture there as well, because you had people from all different kinds of backgrounds going to these parties and it just kept it a good mix of people. Soul II Soul had their own identity, the Funky Dread thing and E=Mix on the mic and it was like an awakening of young British culture. It was very… real.

And the fashion industry was involved too – at the parties, but the distinctive look also feeding back into the fashion world

Definitely, it all went hand in hand. I think it was the first time I'd witnessed a totally British vibe that was just positive and influential. And it became stronger. Just before that Rapattack was very influential – I used to love Rapattack, I loved the way Alistair mixed, he was one of my heroes – but Soul II Soul, was like more a [draws the word out with relish] viiiiiibe, know what I mean?

Was there any trouble fitting in for you personally, with your reputation and your crew?

At first there was. But after a while I was meeting people who didn't know anything about that. So, it was pretty cool. Even though I was a bit rough around the edges. People would be like “Oh is that guy alright?”, because I still had the mannerisms and all that from that lifestyle. But yeah, it smoothed itself out nicely.

So, acid house. What was your first impression walking in to Clink Street? Did you know about the culture?

Nahhh. Someone said “Man, you gotta come to one of these parties!” I went over there and everyone was on ecstasy and everything. I was like “Rahh, what is this?” It was just crazy. I remember going in there and coming straight out for about 20 minutes, and standing outside having a spliff thinking “Fuck me, what the fuck is going on here?” But then I went back in and was like “You know what? This is alright!” I was walking around and soaking it up, it just went from there man.

Had you heard house or techno at any point before that?

Not really, not really. Little bits and bobs on the radio – Colin Faver on Kiss, Colin Dale – but not much, not much. I hadn't given it any attention.

I mean Clink Street was acid and Detroit techno – it wasn't soulful or Balearic or anything, just machine music. So seemingly you'd feel miles removed from the laid-back dubby stuff or rare groove at Soul II Soul. But you got it pretty quickly on that first visit?

It just hit me. I just got it. I heard this record by Armando called ‘Land of Confusion’.96 It was the first acid house record I ever bought. But I just loved it. It spun me out and done something to me. And from that, that was just me – done. Hook line and sinker.

Did you start meeting the people in that scene straight away?

No. At the time I played at a pirate station, called Passion, a community station in Brixton. But they played mostly reggae, it was a proper black station. I used to play the funk and stuff there, and that fit in OK. But overnight, I was just like “Nah, this is what I play now” and everyone was like “What the fuck? This is like devil music, what the fuck are you doing man?” and I was like “Nah this is IT, this is what I'm doing now, yeah?” and then they were like “Alright then, alright, get on with it” [laughs]. But I was getting a lot of callers calling in, they wouldn't let me go on with it. But one day I had a call on my show from Tony Colston-Hayter, who run the parties called Sunrise. He was like “Man I love what you're doing. I want you to come down and play at my club!” At the time they were doing this thing called Club Sunrise at Heaven so I went down there to play. I met Eddie Richards, and we got on like a house on fire straight away. So I started playing at Sunrise, then I met Tintin and I started playing at Energy, which was real massive illegal parties in fields, for 20,000 people, where you gotta go to meeting points and stuff like that.

But did you like the adventure aspect of it?

[Lost in memory for a second] I remember once getting in a car at 10 o’clock at night and we're waiting around all night waiting for the call to tell us where the venue was. And it started at like six in the morning and this was in, like, Ipswich. You got there driving down the hill and you'd see the field with thousands of people and you're like “Wow.” So, the buzz was just incredible. After that I started playing at The Fridge in Brixton, my hometown, every Thursday with Eddie Richards, Paul “Trouble” Anderson97 and Ellis Dee – we were the four residents. From there, Eddie started an agency called Dynamix: Colin Faver was on it, all the Clink Street lot. And he [asked me to join]. So a lot of people started to get to hear about me from there. And I started travelling around Europe, Germany and bom-bom-bom-bom. The momentum went from there.

This is just a year from first hearing acid house! But already you can see how things would split apart: acid house for a while, Paul “Trouble” Anderson playing soulful stuff, Eddie playing techno, Colin Faver the harder techno, and hardcore was coming in. Where did you fit in among all this?

I started off playing things like Joey Beltram. Actually, acid house first then a lot of R&S, I was really into that vibe. But I loved the Detroit stuff – Mark Kinchen, Derrick May, Juan Atkins – Underground Resistance was probably my favourite at the time. That was my little niche. I would go to Germany a hell of a lot. I was actually playing [in Berlin] the night when the wall came down, which was absolutely amazing. I've still got a big bit of it my house, the wall, so yeah, good times!

So 1991-92, you had techno, you had hip hop influence in people like 4 Hero and Shut Up And Dance – but it was still a bit everyone in a field together…

Yeah, but already at that point everything just started proper splintering? You had Carl Cox would go off and do his thing, Paul “Trouble” Anderson – everyone found their niche and I think that's when jungle started, and drum’n’bass. We started using more breaks, taking out the kick – at first you had the 4 x 4 and the breaks, but the 4 x 4 disappeared somehow and it was just the breaks. And we all went that way, me, Grooverider, Fabio, Mickey Finn, Bryan Gee. And other people, well, everyone found their home.

Even as jungle separated off, you were generally still playing alongside the happy hardcore and house DJs at the big events, the Tribal Gatherings. There'd still be this intersection of people, even if it was different arenas and different crowds. But as the sounds started accelerating and splintering, was there a moment when you thought “OK, this is a whole new thing that I'm part of”?

I think when Goldie started coming around, and ‘Terminator’ [actually credited to Metalheadz]. When I first heard that I was like “Wow, this is like a next thing now.” It was like [mimics the voice on the record] “Terminator is coming”. I mean I can't say THE point because there were many points. But I think that was one of the pivotal moments.

So 1992, when the kind of futuristic, sci-fi breakbeat element came along…

What about the reggae influence? When did you feel like your soundsystem stuff was coming back in through the jungle stuff?

Basically I made a record called ‘Burial’, which was probably one of the biggest kind of reggae influenced jungle tunes made. And I got the vibe to do that. I mean there was tunes that had reggae in there going back a way before that, I'm not claiming it was some radical idea to do it – but I think when I made that record.

So you knew that was a big tune once you finished it?

Yeah straight away. As soon as I finished it I just thought, “Ohhhh yeah!” Funnily enough, Dillinja mastered it for me. I went over to his studio with some samples and it just came together in something like five hours, quickly. I listened back at home to it and I just went “Wow”. Obviously, at around the same time as General Levy done ‘Incredible’ [produced by M-Beat].

Were you involved with the Jungle Committee?

Nah, not really. At the time, there was a lot of bitching and people pointing their fingers at this and that. I just went to one meeting to see what was going on, and then let people get on with it. It didn't last very long, I think they had two meetings. Finger pointing, kids being kids.

The energy at jungle raves was unreal, but it was lawless and chaotic. Did it ever feel out of control? Because there was obviously violence as well…

You know what, I started feeling that it was out of hand, because a lot of my friends that I grew up with wanted to start coming to parties and raves. A lot of the Brixton boys were like “We wanna come to parties”. The same people that were years ago saying “You're playing devil music, what the hell?” Suddenly they're at parties – the reggae vibe, it's kind of married to the streets. But there was violence, it did get a bit out of hand, people taking a lot of drugs, a lot of champagne, bling bling lifestyle, gangsters. So it got to a point where a lot of us DJs started pulling away from it and changing the vibe. The dark side vibe was born, so we kind of just left. Because when UK garage came out, a lot of the gangsters and people making trouble went over to that, so it was great for us.

When you say dark side, do you mean the more techstep kind of stuff?

Yeah, we were like “Drop this stuff, mate.” I think the dark side thing plus the UK garage thing going on saved our scene at that point because the violence was becoming really negative.

Who was making the most interesting stuff at that point? Obviously with the V label you started connecting with the Bristol guys…

Yeah that was our label and we always kept it funky. We are lucky because our music stood the test of time. It went through all the different eras, but it stayed true to its path. It was never a dark side label, never really a jungle label, just classic music including jungle and drum’n’bass. Smooth, funky, very compatible with everyone really.

Right, because things locked into certain clichés around 1996 onward; there was the jump-up, there was the techstep, there was the jazzy, soulful side. But you guys managed to go between those styles, and have this less defined sound. And maybe people with very artist- or DJ-controlled labels, like Rebel MC. Was this a conscious decision?

It was the people that we were working with, that Bristol vibe, whether it's Massive Attack, Smith & Mighty, even Portishead. All the artists, creative people – everyone has just got that same energy. I dunno if there's something in the weed [laughs]. It's all got that [he draws out the word again] viiiibe, that smoking vibe, know what I mean?

Who else were your closest allies going through that late 90s period?

Fabio and Grooverider obviously, always been very close to those guys, Goldie, J Majik, Bryan Gee – my business partner too obviously – plus the guys from Bristol, Roni, Krust, Die, Dynamite MC. Mickey Finn, Dillinja, Matty Optical and Ed Rush. That's it really.

So when Dego got his deal, he was hiring orchestras and stuff. Roni made the connection with Gilles Peterson and branched out into a lot of different things. Were you tempted to make hip hop or dub or something different?

Nah, nah, nah. That was me. I just stayed on my path. I love the music so much. I love discovering new music within our scene, me and Bryan, and finding new artists. It was just our label, V. And our other label Philly Blunt as well. It was just about that, know what I mean?

You had such a clear identity for Philly Blunt. Just seeing the logo gives me flashbacks, like Firefox ‘Warning’ 98 [actually credited to Firefox & 4-Tree] or Dillinja ‘Motherfucker’. What's interesting about drum’n’bass is, as it became less fashionable – and garage took over and then dubstep and grime – it never died away? Did your bookings ever take a dip?

Nah, nah. It always stayed the same. Maybe about 2000? Actually nah, it always stayed the same.

Are there particular territories internationally or does it rise and fall in different countries?

And places like Russia, the scene picked up incrementally

Drum’n’bass has maintained this weird internal stability. How do you think that's been managed, given its chaotic beginnings?

Our loyalties to each other, we all helped, it was like our baby and we all helped it to grow. There was so much loyalty among one another. We all needed each other to maintain our standards and to keep pushing each other to new heights.

What about developments in drum’n’bass over the 2000s? I mean this heavy production arms race with Bad Company and then Pendulum and the mega acts. Did you ever feel that might derail things? And then the pop side as well, Hospitality and stuff like that

You're talking about popular music – that's what “pop” is. If someone makes a good record and suddenly it becomes popular, does that make it pop? At some point, the underground liked it – just because loads of people like it doesn't make it “pop”. know what I mean? People wanted to try new things, and it evolved into this polished production that could stand up to any genre in the world.

A lot of the grime MCs had been in the drum’n’bass scene, and a lot of the dubstep guys, their older brothers were drum’n’bass guys. Dubstep started pushing into the jungle raves and the drum’n’bass raves…

In America dubstep totally took over. There was a time when I wasn't even going to America anymore because they were just all over the dubstep. Last couple of years it seems to have burnt itself out.

Do you feel like a musical family connection in music? I mean in dubstep, Hatcha's mum was in jungle, Skream's older brother [Hijak], Benga's older brother

At the end of the day it's electronic bass music, know what I mean? It's all related: made on a computer by very talented people!

Do you ever feel we've run out of musical revolutions? Drum’n’bass began 25 years ago!

As soon as you start thinking like that, you're on the wrong track. Something else will come up to [punctuates the words with heavy seriousness] blow. you. away.

Do you feel the legacy of all that stuff – like Soul II Soul and Clink – is healthy? Are you proud of what you achieved then and what it's done?

Yeah yeah yeah yeah – I do, I do. I think it's had such a good effect, especially the acid house parties. You get people from all kinds of backgrounds, colours, nationalities, all coming together and meeting each other. You wouldn't get that in any other kind of time or genre. We all knew different people and that – it was a revolution, a cultural explosion at the time it was so unique.

Jumpin’ Jack Frost's autobiography ‘Big, Bad & Heavy’ was published by Music Mondays in 2017.99