Lamenting the Consequences of War

The Bhagavad Gita was spoken on the battleground of the Mahabharat war, an enormous war that was just about to begin between two sets of cousins, the Kauravas and the Pandavas. A detailed description of developments that led to the colossal war is given in the Introduction to this book, in the section “The Setting of the Bhagavad Gita.”

The Bhagavad Gita begins to unfold as a dialogue between King Dhritarashtra and his minister Sanjay. Since Dhritarashtra was blind, he could not be personally present on the battlefield. Hence, Sanjay was giving him a first-hand account of the events on the warfront. Sanjay was the disciple of Sage Ved Vyas, the celebrated writer of the Mahabharat. Ved Vyas possessed the mystic power of being able to see what was happening in distant places. By the grace of his teacher, Sanjay also possessed the mystic ability of distant vision. Thus he could see from afar all that transpired on the battleground.

dhṛitarāśhtra uvācha

dharma-kṣhetre kuru-kṣhetre samavetā yuyutsavaḥ

māmakāḥ pāṇḍavāśhchaiva kimakurvata sañjaya

dhṛitarāśhtraḥ uvācha—Dhritarashtra said; dharma-kṣhetre—the land of dharma; kuru-kṣhetre—at Kurukshetra; samavetāḥ—having gathered; yuyutsavaḥ—desiring to fight; māmakāḥ—my sons; pāṇḍavāḥ—the sons of Pandu; cha—and; eva—certainly; kim—what; akurvata—did they do; sañjaya—Sanjay.

Dhritarashtra said: O Sanjay, after gathering on the holy field of Kurukshetra, and desiring to fight, what did my sons and the sons of Pandu do?

King Dhritarashtra, apart from being blind from birth, was also bereft of spiritual wisdom. His attachment to his own sons made him deviate from the path of virtue and usurp the rightful kingdom of the Pandavas. He was conscious of the injustice he had done toward his own nephews, the sons of Pandu. His guilty conscience worried him about the outcome of the battle, and so he inquired from Sanjay about the events on the battlefield of Kurukshetra, where the war was to be fought.

In this verse, the question he asked Sanjay was, what did his sons and the sons of Pandu do, having gathered on the battlefield? Now, it was obvious that they had assembled there with the sole purpose of fighting. So it was natural that they would fight. Why did Dhritarashtra feel the need to ask what they did?

His doubt can be discerned from the words he used—dharma kṣhetre, the land of dharma (virtuous conduct). Kurukshetra was a sacred land. In the Shatapath Brahman, it is described as: kurukṣhetraṁ deva yajanam [v1]. “Kurukshetra is the sacrificial arena of the celestial gods.” It was thus the land that nourished dharma. Dhritarashtra apprehended that the influence of the holy land of Kurukshetra would arouse the faculty of discrimination in his sons and they would regard the massacre of their relatives, the Pandavas, as improper. Thinking thus, they might agree to a peaceful settlement. Dhritarashtra felt great dissatisfaction at this possibility. He thought if his sons negotiated a truce, the Pandavas would continue to remain an impediment for them, and hence it was preferable that the war took place. At the same time, he was uncertain of the consequences of the war, and wished to ascertain the fate of his sons. As a result, he asked Sanjay about the goings-on at the battleground of Kurukshetra, where the two armies had gathered.

sañjaya uvācha

dṛiṣhṭvā tu pāṇḍavānīkaṁ vyūḍhaṁ duryodhanastadā

āchāryamupasaṅgamya rājā vachanamabravīt

sanjayaḥ uvācha—Sanjay said; dṛiṣhṭvā—on observing; tu—but; pāṇḍava-anīkam—the Pandava army; vyūḍham—standing in a military formation; duryodhanaḥ—King Duryodhan; tadā—then; āchāryam—teacher; upasaṅgamya—approaced; rājā—the king; vachanam—words; abravīt—spoke.

Sanjay said: On observing the Pandava army standing in military formation, King Duryodhan approached his teacher Dronacharya, and said the following words.

Dhritarashtra was looking for an affirmation that the battle would still be undertaken by his sons. Sanjay understood Dhritarashtra’s intent behind the question and confirmed that there would definitely be war by saying that the Pandavas were standing in military formation ready for war. He further turned the conversation to the subject of what Duryodhan was doing.

Duryodhan, the eldest son of Dhritarasthra, possessed a very evil and cruel nature. Since Dhritarashtra was blind, Duryodhan practically ruled the kingdom of Hastinapur on his behalf. He had a strong dislike for the Pandavas, and was determined to eliminate them, so that he may rule unopposed. He had assumed that the Pandavas would not be able to mobilize an army that could face his. But what happened was to the contrary, and beholding the extent of military might they had gathered, he was perturbed and unnerved.

Duryodhan’s move to approach his military guru, Dronacharya, revealed that he was fearful of the outcome of the war. He went to Dronacharya with the pretense of offering respect, but his actual purpose was to palliate his own anxiety. Thus, Duryodhan spoke nine verses beginning with the next one.

paśhyaitāṁ pāṇḍu-putrāṇām āchārya mahatīṁ chamūm

vyūḍhāṁ drupada-putreṇa tava śhiṣhyeṇa dhīmatā

paśhya—behold; etām—this; pāṇḍu-putrāṇām—of the sons of Pandu; āchārya—respected teacher; mahatīm—mighty; chamūm—army; vyūḍhām—arrayed in a military formation; drupada-putreṇa—son of Drupad, Dhrishtadyumna; tava—by your; śhiṣhyeṇa—disciple; dhī-matā—intelligent.

Duryodhan said: Respected teacher! Behold the mighty army of the sons of Pandu, so expertly arrayed for battle by your own gifted disciple, the son of Drupad.

Duryodhan diplomatically pointed to his military preceptor, Dronacharya, the mistake committed by him in the past. Dronacharya had once had a political quarrel with King Drupad. Angered by the quarrel, Drupad performed a sacrifice, and received a boon to beget a son who would be able to kill Dronacharya. As a result of this boon, Dhrishtadyumna was born to him.

Although Dronacharya knew the purpose of Dhrishtadyumna’s birth, yet out of his large-heartedness, when Dhrishtadyumna was entrusted to him for military education, he did not hesitate to impart all his knowledge to him. Now, in the battle, Dhrishtadyumna had taken the side of the Pandavas as the commander-in-chief of their army, and he was the one who had arranged their military phalanx. Duryodhan thus hinted to his teacher that his lenience in the past had gotten them into the present trouble, and that he should not display any further lenience in fighting the Pandavas now.

atra śhūrā maheṣhvāsā bhīmārjuna-samā yudhi

yuyudhāno virāṭaśhcha drupadaśhcha mahā-rathaḥ

dhṛiṣhṭaketuśhchekitānaḥ kāśhirājaśhcha vīryavān

purujit kuntibhojaśhcha śhaibyaśhcha nara-puṅgavaḥ

yudhāmanyuśhcha vikrānta uttamaujāśhcha vīryavān

saubhadro draupadeyāśhcha sarva eva mahā-rathāḥ

atra—here; śhūrāḥ—powerful warriors; mahā-iṣhu-āsāḥ—great bowmen; bhīma-arjuna-samāḥ—equal to Bheem and Arjun; yudhi—in military prowess; yuyudhānaḥ—Yuyudhan; virāṭaḥ—Virat; cha—and; drupadaḥ—Drupad; cha—also; mahā-rathaḥ—warriors who could single handedly match the strength of ten thousand ordinary warriors; dhṛiṣhṭaketuḥ—Dhrishtaketu; chekitānaḥ—Chekitan; kāśhirājaḥ—Kashiraj; cha—and; vīrya-vān—heroic; purujit—Purujit; kuntibhojaḥ—Kuntibhoj; cha—and; śhaibyaḥ—Shaibya; cha—and; nara-puṅgavaḥ—best of men; yudhāmanyuḥ—Yudhamanyu; cha—and; vikrāntaḥ—courageous; uttamaujāḥ—Uttamauja; cha—and; vīrya-vān—gallant; saubhadraḥ—the son of Subhadra; draupadeyāḥ—the sons of Draupadi; cha—and; sarve—all; eva—indeed; mahā-rathāḥ—warriors who could single handedly match the strength of ten thousand ordinary warriors.

Behold in their ranks are many powerful warriors, like Yuyudhan, Virat, and Drupad, wielding mighty bows and equal in military prowess to Bheem and Arjun. There are also accomplished heroes like Dhrishtaketu, Chekitan, the gallant King of Kashi, Purujit, Kuntibhoj, and Shaibya—all the best of men. In their ranks, they also have the courageous Yuyudhamanyu, the gallant Uttamauja, the son of Subhadra, and the sons of Draupadi, who are all great warrior chiefs.

In the eyes of Duryodhan, due to his fear of the looming catastrophe, the army mobilized by the Pandavas seemed larger than it actually was. Expressing his anxiety, he pointed out the maharathīs (warriors who could single handedly match the strength of ten thousand ordinary warriors) present on the Pandavas side. Duryodhan mentioned the exceptional heroes amidst the Pandavas ranks, who were all great military commanders equal in strength to Arjun and Bheem, and who would be formidable in the battle.

asmākaṁ tu viśhiṣhṭā ye tānnibodha dwijottama

nāyakā mama sainyasya sanjñārthaṁ tānbravīmi te

asmākam—ours; tu—but; viśhiṣhṭāḥ—special; ye—who; tān—them; nibodha—be informed; dwija-uttama—best of Brahmnis; nāyakāḥ—principal generals; mama—our; sainyasya—of army; sanjñā-artham—for information; tān—them; bravīmi—I recount; te—unto you.

O best of Brahmins, hear too about the principal generals on our side, who are especially qualified to lead. These I now recount unto you.

Duryodhan addressed Dronacharya, the commander-in-chief of the Kaurava army, as dwijottam (best amongst the twice-born, or Brahmins). He deliberately used the word to address his teacher. Dronacharya was not really a warrior by profession; he was only a teacher of military science. As a deceitful leader, Duryodhan even entertained shameless doubts about the loyalty of his own preceptor. The hidden meaning in Duryodhan’s words was that if Dronacharya did not fight courageously, he would merely be a Brahmin interested in eating fine food served at the palace of Duryodhan.

Having said that, Duryodhan now desired to boost his own morale and that of his teacher, and so he started enumerating the great generals in his own army.

bhavānbhīṣhmaśhcha karṇaśhcha kṛipaśhcha samitiñjayaḥ

aśhvatthāmā vikarṇaśhcha saumadattis tathaiva cha

bhavān—yourself; bhīṣhmaḥ—Bheeshma; cha—and; karṇaḥ—Karna; cha—and; kṛipaḥ—Kripa; cha—and; samitim-jayaḥ—victorious in battle; aśhvatthāmā—Ashvatthama; vikarṇaḥ—Vikarna; cha—and; saumadattiḥ—Bhurishrava; tathā—thus; eva—even; cha—also.

There are personalities like yourself, Bheeshma, Karna, Kripa, Ashwatthama, Vikarn, and Bhurishrava, who are ever victorious in battle.

anye cha bahavaḥ śhūrā madarthe tyaktajīvitāḥ

nānā-śhastra-praharaṇāḥ sarve yuddha-viśhāradāḥ

anye—others; cha—also; bahavaḥ—many; śhūrāḥ—heroic warriors; mat-arthe—for my sake; tyakta-jīvitāḥ—prepared to lay down their lives; nānā-śhastra-praharaṇāḥ—equipped with various kinds of weapons; sarve—all; yuddha-viśhāradāḥ—skilled in the art of warfare.

Also, there are many other heroic warriors, who are prepared to lay down their lives for my sake. They are all skilled in the art of warfare, and equipped with various kinds of weapons.

aparyāptaṁ tadasmākaṁ balaṁ bhīṣhmābhirakṣhitam

paryāptaṁ tvidameteṣhāṁ balaṁ bhīmābhirakṣhitam

aparyāptam—unlimited; tat—that; asmākam—ours; balam—strength; bhīṣhma—by Grandsire Bheeshma; abhirakṣhitam—safely marshalled; paryāptam—limited; tu—but; idam—this; eteṣhām—their; balam—strength; bhīma—Bheem; abhirakṣhitam—carefully marshalled.

The strength of our army is unlimited and we are safely marshalled by Grandsire Bheeshma, while the strength of the Pandava army, carefully marshalled by Bheem, is limited.

Duryodhan’s words of self-aggrandizement were the typical utterances of a vainglorious person. When their end draws near, instead of making a humble evaluation of the situation, self-aggrandizing people egotistically indulge in vainglory. This tragic irony of fate was reflected in the statement of Duryodhan, when he said that their strength, secured by Bheeshma, was unlimited.

Grandsire Bheeshma was the commander-in-chief of the Kaurava army. He had received the boon that he could choose his time of death, which made him practically invincible. On the Pandavas’ side, the army was secured by Bheem, who was Duryodhan’s sworn enemy. Thus, Duryodhan compared the strength of Bheeshma with the might of Bheem. Bheeshma, however, was the uncle of both the Kauravas and the Pandavas, and he was genuinely concerned about the welfare of both sides. His compassion for the Pandavas would prevent him from fighting the war wholeheartedly. Also, he knew that in this holy war, where Lord Krishna himself was present, no power on earth could make the side of adharma win. And so, in order to honor his ethical commitment to the subjects of Hastinapur and the Kauravas, he chose to fight against the Pandavas. This decision underscores the enigmatic character of Bheeshma’s personality.

ayaneṣhu cha sarveṣhu yathā-bhāgamavasthitāḥ

bhīṣhmamevābhirakṣhantu bhavantaḥ sarva eva hi

ayaneṣhu—at the strategic points; cha—also; sarveṣhu—all; yathā-bhāgam—in respective position; avasthitāḥ—situated; bhīṣhmam—to Grandsire Bheeshma; eva—only; abhirakṣhantu—defend; bhavantaḥ—you; sarve—all; eva hi—even as.

Therefore, I call upon all the generals of the Kaurava army now to give full support to Grandsire Bheeshma, even as you defend your respective strategic points.

Duryodhan looked upon Bheeshma’s unassailability as the inspiration and strength of his army. Thus, he asked his army generals to rally around Bheeshma, while defending their respective vantage points in the military phalanx.

tasya sañjanayan harṣhaṁ kuru-vṛiddhaḥ pitāmahaḥ

siṁha-nādaṁ vinadyochchaiḥ śhaṅkhaṁ dadhmau pratāpavān

tasya—his; sañjanayan—causing; harṣham—joy; kuru-vṛiddhaḥ—the grand old man of the Kuru dynasty (Bheeshma); pitāmahaḥ—grandfather; sinha-nādam—lion's roar; vinadya—sounding; uchchaiḥ—very loudly; śhaṅkham—conch shell; dadhmau—blew; pratāpa-vān—the glorious.

Then, the grand old man of the Kuru dynasty, the glorious patriarch Bheeshma, roared like a lion, and blew his conch shell very loudly, giving joy to Duryodhan.

Grandsire Bheeshma understood the fear in his grand-nephew’s heart, and out of his natural compassion for him, he tried to cheer him by blowing his conch shell very loudly. Although he knew that Duryodhan had no chance of victory due to the presence of the Supreme Lord Shree Krishna on the other side, Bheeshma still let his nephew know that he would perform his duty to fight, and no pains would be spared in this connection. In the code of war at that time, this was the inauguration of the battle.

tataḥ śhaṅkhāśhcha bheryaśhcha paṇavānaka-gomukhāḥ

sahasaivābhyahanyanta sa śhabdastumulo ’bhavat

tataḥ—thereafter; śhaṅkhāḥ—conches; cha—and; bheryaḥ—bugles; cha—and; paṇava-ānaka—drums and kettledrums; go-mukhāḥ—trumpets; sahasā—suddenly; eva—indeed; abhyahanyanta—blared forth; saḥ—that; śhabdaḥ—sound; tumulaḥ—overwhelming; abhavat—was.

Thereafter, conches, kettledrums, bugles, trumpets, and horns suddenly blared forth, and their combined sound was overwhelming.

Seeing the great eagerness of Bheeshma for battle, the Kaurava army also became eager, and began creating a tumultuous sound. Paṇav means drums, ānak means kettledrums, and go-mukh means blowing horns. These are all musical instruments, and the sounds of all these combined together caused a great uproar.

tataḥ śhvetairhayairyukte mahati syandane sthitau

mādhavaḥ pāṇḍavaśhchaiva divyau śhaṅkhau pradadhmatuḥ

tataḥ—then; śhvetaiḥ—by white; hayaiḥ—horses; yukte—yoked; mahati—glorious; syandane—chariot; sthitau—seated; mādhavaḥ—Shree Krishna, the husband of the goddess of fortune, Lakshmi; pāṇḍavaḥ—Arjun; cha—and; eva—also; divyau—Divine; śhaṅkhau—conch shells; pradadhmatuḥ—blew.

Then, from amidst the Pandava army, seated in a glorious chariot drawn by white horses, Madhav and Arjun blew their Divine conch shells.

After the sound from the Kaurava army had subsided, the Supreme Lord Shree Krishna and Arjun, seated on a magnificent chariot, intrepidly blew their conch shells powerfully, igniting the Pandavas eagerness for battle as well.

Sanjay uses the name “Madhav” for Shree Krishna. Mā refers to the goddess of fortune; dhav means husband. Shree Krishna in his form as Lord Vishnu is the husband of the goddess of fortune, Lakshmi. The verse indicates that the grace of the goddess of fortune was on the side of the Pandavas, and they would soon be victorious in the war to reclaim the kingdom.

Pandavas means sons of Pandu. Any of the five brothers may be referred to as Pandava. Here the word is being used for Arjun. The glorious chariot on which he was sitting had been gifted to him by Agni, the celestial god of fire.

pāñchajanyaṁ hṛiṣhīkeśho devadattaṁ dhanañjayaḥ

pauṇḍraṁ dadhmau mahā-śhaṅkhaṁ bhīma-karmā vṛikodaraḥ

pāñchajanyam—the conch shell named Panchajanya; hṛiṣhīka-īśhaḥ—Shree Krishna, the Lord of the mind and senses; devadattam—the conch shell named Devadutta; dhanam-jayaḥ—Arjun, the winner of wealth; pauṇḍram—the conch named Paundra; dadhmau—blew; mahā-śhaṅkham—mighty conch; bhīma-karmā—one who performs herculean tasks; vṛika-udaraḥ—Bheem, the voracious eater.

Hrishikesh blew his conch shell, called Panchajanya, and Arjun blew the Devadutta. Bheem, the voracious eater and performer of herculean tasks, blew his mighty conch, called Paundra.

The word “Hrishikesh” means Lord of the mind and senses, and has been used for Shree Krishna. He is the Supreme Master of everyone’s mind and senses, including his own. Even while performing amazing pastimes on the planet Earth, he maintained complete mastery over his own mind and senses.

anantavijayaṁ rājā kuntī-putro yudhiṣhṭhiraḥ

nakulaḥ sahadevaśhcha sughoṣha-maṇipuṣhpakau

kāśhyaśhcha parameṣhvāsaḥ śhikhaṇḍī cha mahā-rathaḥ

dhṛiṣhṭadyumno virāṭaśhcha sātyakiśh chāparājitaḥ

drupado draupadeyāśhcha sarvaśhaḥ pṛithivī-pate

saubhadraśhcha mahā-bāhuḥ śhaṅkhāndadhmuḥ pṛithak pṛithak

ananta-vijayam—the conch named Anantavijay; rājā—king; kuntī-putraḥ—son of Kunti; yudhiṣhṭhiraḥ—Yudhishthir; nakulaḥ—Nakul; sahadevaḥ—Sahadev; cha—and; sughoṣha-maṇipuṣhpakau—the conche shells named Sughosh and Manipushpak; kāśhyaḥ—King of Kashi; cha—and; parama-iṣhu-āsaḥ—the excellent archer; śhikhaṇḍī—Shikhandi; cha—also; mahā-rathaḥ—warriors who could single handedly match the strength of ten thousand ordinary warriors; dhṛiṣhṭadyumnaḥ—Dhrishtadyumna; virāṭaḥ—Virat; cha—and; sātyakiḥ—Satyaki; cha—and; aparājitaḥ—invincible; drupadaḥ—Drupad; draupadeyāḥ—the five sons of Draupadi; cha—and; sarvaśhaḥ—all; pṛithivī-pate—Ruler of the earth; saubhadraḥ—Abhimanyu, the son of Subhadra; cha—also; mahā-bāhuḥ—the mighty-armed; śhaṅkhān—conch shells; dadhmuḥ—blew; pṛithak pṛithak—individually.

King Yudhishthir, blew the Anantavijay, while Nakul and Sahadev blew the Sughosh and Manipushpak. The excellent archer and king of Kashi, the great warrior Shikhandi, Dhrishtadyumna, Virat, and the invincible Satyaki, Drupad, the five sons of Draupadi, and the mighty-armed Abhimanyu, son of Subhadra, all blew their respective conch shells, O Ruler of the earth.

Yudhisthir was the eldest of the Pandava brothers. Here, he is being called “King”; he had earned the right to that title after performing the Rājasūya Yajña and receiving tribute from all the other kings. Also, his bearing exuded royal grace and magnanimity, whether he was in the palace or in exile in the forest.

Dhritarashtra is being called “Ruler of the earth” by Sanjay. To preserve a country or engage it in a ruinous warfare is all in the hands of the ruler. So the hidden implication in the appellation is, “The armies are heading for war. O Ruler, Dhritarashtra, you alone can call them back. What are you going to decide?”

sa ghoṣho dhārtarāṣhṭrāṇāṁ hṛidayāni vyadārayat

nabhaśhcha pṛithivīṁ chaiva tumulo nunādayan

saḥ—that; ghoṣhaḥ—sound; dhārtarāṣhṭrāṇām—of Dhritarashtra's sons; hṛidayāni—hearts; vyadārayat—shattered; nabhaḥ—the sky; cha—and; pṛithivīm—the earth; cha—and; eva—certainly; tumulaḥ—terrific sound; abhyanunādayan—thundering.

The terrific sound thundered across the sky and the earth, and shattered the hearts of your sons, O Dhritarasthra.

The sound from the conch shells of the Pandava army shattered the hearts of the Kaurava army. However, no such effect on the Pandava army was mentioned when the Kaurava army blew on their conches. Since the Pandavas had taken the shelter of the Lord, they were confident of being preserved. On the other hand, the Kauravas, relying on their own strength, and pricked by the guilty conscience of their crimes, became fearful of defeat.

atha vyavasthitān dṛiṣhṭvā dhārtarāṣhṭrān kapi-dhwajaḥ

pravṛitte śhastra-sampāte dhanurudyamya pāṇḍavaḥ

hṛiṣhīkeśhaṁ tadā vākyam idam āha mahī-pate

atha—thereupon; vyavasthitān—arrayed; dṛiṣhṭvā—seeing; dhārtarāṣhṭrān—Dhritarashtra's sons; kapi-dwajaḥ—the Monkey Bannered; pravṛitte—about to commence; śhastra-sampāte—to use the weapons; dhanuḥ—bow; udyamya—taking up; pāṇḍavaḥ— Arjun, the son of Pandu; hṛiṣhīkeśham—to Shree Krishna; tadā—at that time; vākyam—words; idam—these; āha—said; mahī-pate—King.

At that time, the son of Pandu, Arjun, who had the insignia of Hanuman on the flag of his chariot, took up his bow. Seeing your sons arrayed against him, O King, Arjun then spoke the following words to Shree Krishna.

Arjun is called by the name Kapi Dhwaj, denoting the presence of the powerful Hanuman on his chariot. There is a story behind this. Arjun once became proud of his skill in archery, and told Shree Krishna that he could not understand why, in the time of Lord Ram, the monkeys labored so much to make the bridge from India to Lanka. Had he been there, he would have made a bridge of arrows. Shree Krishna asked him to demonstrate. Arjun made the bridge by releasing a shower of arrows. Shree Krishna called Hanuman to come and test the bridge. When the great Hanuman began walking on it, the bridge started crumbling. Arjun realized that his bridge of arrows would never have been able to uphold the weight of the vast army of Lord Ram, and apologized for his mistake. Hanuman then taught Arjun the lesson to never become proud of his skills. He benevolently gave the boon to Arjun that he would sit on his chariot during the battle of Mahabharat. Therefore, Arjun’s chariot carried the insignia of Hanuman on its flag, from which he got the name “Kapi Dhwaj,” or the “Monkey Bannered.”

arjuna uvācha

senayor ubhayor madhye rathaṁ sthāpaya me ’chyuta

yāvadetān nirīkṣhe ’haṁ yoddhu-kāmān avasthitān

kairmayā saha yoddhavyam asmin raṇa-samudyame

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; senayoḥ—armies; ubhayoḥ—both; madhye—in the middle; ratham—chariot; sthāpaya—place; me—my; achyuta—Shree Krishna, the infallible One; yāvat—as many as; etān—these; nirīkṣhe—look; aham—I; yoddhu-kāmān—for the battle; avasthitān—arrayed; kaiḥ—with whom; mayā—by me; saha—together; yoddhavyam—must fight; asmin—in this; raṇa-samudyame—great combat.

Arjun said: O Infallible One, please take my chariot to the middle of both armies, so that I may look at the warriors arrayed for battle, whom I must fight in this great combat.

Arjun was a devotee of Shree Krishna, who is the Supreme Lord of the entire creation. Yet, in this verse, Arjun instructed the Lord to drive his chariot in to the desired place. This reveals the sweetness of God’s relationship with His devotees. Indebted by their love for him, the Lord becomes the servant of his devotees.

ahaṁ bhakta-parādhīno hyasvatantra iva dvija

sādhubhir grasta-hṛidayo bhaktair bhakta-jana-priyaḥ

(Bhāgavatam 9.4.63)[v2]

“Although I am Supremely Independent, yet I become enslaved by my devotees. They are very dear to me, and I become indebted to them for their love.” Obliged by Arjun’s devotion, Shree Krishna took the position of the chariot driver, while Arjun sat comfortably on the passenger seat giving him instructions.

yotsyamānān avekṣhe ’haṁ ya ete ’tra samāgatāḥ

dhārtarāṣhṭrasya durbuddher yuddhe priya-chikīrṣhavaḥ

yotsyamānān—those who have come to fight; avekṣhe aham—I desire to see; ye—who; ete—those; atra—here; samāgatāḥ—assembled; dhārtarāṣhṭrasya—of Dhritarashtra's son; durbuddheḥ—evil-minded; yuddhe—in the fight; priya-chikīrṣhavaḥ—wishing to please.

I desire to see those who have come here to fight on the side of the evil-minded son of Dhritarasthra, wishing to please him.

The evil-minded sons of Dhritarasthra had usurped the kingdom, and so the warriors fighting from their side were also naturally ill-intentioned. Arjun desired to see those whom he would have to fight in this war. To begin with, Arjun was valiant and eager for the battle. Hence, he referred to the evil-minded sons of Dhritarasthra, conveying how Duryodhan had conspired several times for the destruction of the Pandavas. Arjun’s attitude was, “We are the lawful owners of half of the empire, but he wants to usurp it. He is evil-minded and these kings have assembled to help him, so they are also evil. I want to observe the warriors who are so impatient to wage war. They have favored injustice, and so they are sure to be destroyed by us.”

sañjaya uvācha

evam ukto hṛiṣhīkeśho guḍākeśhena bhārata

senayor ubhayor madhye sthāpayitvā rathottamam

sañjayaḥ uvācha—Sanjay said; evam—thus; uktaḥ—addressed; hṛiṣhīkeśhaḥ—Shree Krishna, the Lord of the senses; guḍākeśhena—by Arjun, the conqueror of sleep; bhārata—descendant of Bharat; senayoḥ—armies; ubhayoḥ—the two; madhye—between; sthāpayitvā—having drawn; ratha-uttamam—magnificent chariot.

Sanjay said: O Dhritarasthra, having thus been addressed by Arjun, the conqueror of sleep, Shree Krishna then drew the magnificent chariot between the two armies.

bhīṣhma-droṇa-pramukhataḥ sarveṣhāṁ cha mahī-kṣhitām

uvācha pārtha paśhyaitān samavetān kurūn iti

bhīṣhma—Grandsire Bheeshma; droṇa—Dronacharya; pramukhataḥ—in the presence; sarveṣhām—all; cha—and; mahī-kṣhitām—other kings; uvācha—said; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; paśhya—behold; etān—these; samavetān—gathered; kurūn—descendants of Kuru; iti—thus.

In the presence of Bheeshma, Dronacharya, and all the other kings, Shree Krishna said: O Parth, behold these Kurus gathered here.

The word “Kuru” includes both the Kauravas and the Pandavas, because they both belong to the Kuru family. Shree Krishna deliberately uses this word to enthuse the feeling of kinship in Arjun and make him feel that they are all one. He wants the feeling of kinship to lead to attachment, which would confuse Arjun, and give Shree Krishna the opportunity to preach the gospel of the Bhagavad Gita for the benefit of the human beings of the forthcoming age of Kali. Thus, instead of using the word dhārtarāṣhṭrān (sons of Dhritarashtra), he uses the word kurūn (descendants of Kuru). Just as a surgeon first gives medicine to a patient suffering from a boil, to suppurate it, and then performs surgery to remove the diseased part, the Lord is working in the same way to first arouse the hidden delusion of Arjun, only to destroy it later.

tatrāpaśhyat sthitān pārthaḥ pitṝīn atha pitāmahān

āchāryān mātulān bhrātṝīn putrān pautrān sakhīns tathā

śhvaśhurān suhṛidaśh chaiva senayor ubhayor api

tatra—there; apaśhyat—saw; sthitān—stationed; pārthaḥ—Arjun; pitṝīn—fathers; atha—thereafter; pitāmahān—grandfathers; āchāryān—teachers; mātulān—maternal uncles; bhrātṝīn—brothers; putrān—sons; pautrān—grandsons; sakhīn—friends; tathā—also; śhvaśhurān—fathers-in-law; suhṛidaḥ—well-wishers; cha—and; eva—indeed; senayoḥ—armies; ubhayoḥ—in both armies; api—also.

There, Arjun could see stationed in both armies, his fathers, grandfathers, teachers, maternal uncles, brothers, cousins, sons, nephews, grand-nephews, friends, fathers-in-law, and well-wishers.

tān samīkṣhya sa kaunteyaḥ sarvān bandhūn avasthitān

kṛipayā parayāviṣhṭo viṣhīdann idam abravīt

tān—these; samīkṣhya—on seeing; saḥ—they; kaunteyaḥ—Arjun, the son of Kunti; sarvān—all; bandhūn—relatives; avasthitān—present; kṛipayā—by compassion; parayā—great; āviṣhṭaḥ—overwhelmed; viṣhīdan—deep sorrow; idam—this; abravīt—spoke.

Seeing all his relatives present there, Arjun, the son of Kunti, was overwhelmed with compassion, and with deep sorrow, spoke the following words.

The sight of his relatives in the battlefield brought for the first time to Arjun’s mind the realization of the consequences of this fratricidal war. The valiant warrior who had come for battle, mentally prepared for dispatching his enemies to the gates of death, to avenge the wrongs that had been committed to the Pandavas, suddenly had a change of heart. Seeing his fellow Kurus assembled in the enemy ranks, his heart sank, his intellect became confused, his bravery was replaced by cowardice toward his duty, and his stoutheartedness gave way to softheartedness. Hence, Sanjay calls him as the son of Kunti, his mother, referring to the softhearted and nurturing side of his nature.

arjuna uvācha

dṛiṣhṭvemaṁ sva-janaṁ kṛiṣhṇa yuyutsuṁ samupasthitam

sīdanti mama gātrāṇi mukhaṁ cha pariśhuṣhyati

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; dṛiṣhṭvā—on seeing; imam—these; sva-janam—kinsmen; kṛiṣhṇa—Krishna; yuyutsum—eager to fight; samupasthitam—present; sīdanti—quivering; mama—my; gātrāṇi—limbs; mukham—mouth; cha—and; pariśhuṣhyati—is drying up.

Arjun said: O Krishna, seeing my own kinsmen arrayed for battle here and intent on killing each other, my limbs are giving way and my mouth is drying up.

Affection can be either a material or a spiritual sentiment. Attachment for one’s relatives is a material emotion arising from the bodily concept of life. Thinking oneself to be the body, one gets attached to the relatives of the body. This attachment is based on ignorance, and drags one further into materialistic consciousness. Ultimately, such attachment ends in pain, for with the end of the body, the familial relationships end too. On the other hand, the Supreme Lord is the Father, Mother, Friend, Master, and Beloved of our soul. Consequently, attachment to him is a spiritual sentiment, at the platform of the soul, which elevates the consciousness and illumines the intellect. Love for God is oceanic and all-encompassing in its scope, while love for bodily relations is narrow and differentiating. Here, Arjun was experiencing material attachment, which was drowning his mind in an ocean of gloom, and making him tremble at the thought of doing his duty.

vepathuśh cha śharīre me roma-harṣhaśh cha jāyate

gāṇḍīvaṁ sraṁsate hastāt tvak chaiva paridahyate

na cha śhaknomy avasthātuṁ bhramatīva cha me manaḥ

nimittāni cha paśhyāmi viparītāni keśhava

na cha śhreyo ’nupaśhyāmi hatvā sva-janam āhave

vepathuḥ—shuddering; cha—and; śharīre—on the body; me—my; roma-harṣhaḥ—standing of bodily hair on end; cha—also; jāyate—is happening; gāṇḍīvam—Arjun's bow; sraṁsate—is slipping; hastāt—from (my) hand; tvak—skin; cha—and; eva—indeed; paridahyate—is burning all over; na—not; cha—and; śhaknomi—am able; avasthātum—remain steady; bhramati iva—whirling like; cha—and; me—my; manaḥ—mind; nimittāni—omens; cha—and; paśhyāmi—I see; viparītāni—misfortune; keśhava—Shree Krishna, killer of the Keshi demon; na—not; cha—also; śhreyaḥ—good; anupaśhyāmi—I foresee; hatvā—from killing; sva-janam—kinsmen; āhave—in battle.

My whole body shudders; my hair is standing on end. My bow, the Gāṇḍīv, is slipping from my hand, and my skin is burning all over. My mind is in quandary and whirling in confusion; I am unable to hold myself steady any longer. O Krishna, killer of the Keshi demon, I only see omens of misfortune. I do not foresee how any good can come from killing my own kinsmen in this battle.

As Arjun thought of the consequences of the war, he grew worried and sad. The same Gāṇḍīv bow, the sound of which had terrified powerful enemies, began dropping from his hand. His mind was reeling, thinking it was a sin to wage the war. In this unsteadiness of mind, he even descended to the level of accepting superstitious omens portending disastrous failures and imminent consequences.

na kāṅkṣhe vijayaṁ kṛiṣhṇa na cha rājyaṁ sukhāni cha

kiṁ no rājyena govinda kiṁ bhogair jīvitena vā

yeṣhām arthe kāṅkṣhitaṁ no rājyaṁ bhogāḥ sukhāni cha

ta ime ’vasthitā yuddhe prāṇāṁs tyaktvā dhanāni cha

na—nor; kāṅkṣhe—do I desire; vijayam—victory; kṛiṣhṇa—Krishna; na—nor; cha—as well; rājyam—kingdom; sukhāni—happiness; cha—also; kim—what; naḥ—to us; rājyena—by kingdom; govinda—Krishna, he who gives pleasure to the senses, he who is fond of cows; kim—what?; bhogaiḥ—pleasures; jīvitena—life; vā—or; yeṣhām—for whose; arthe—sake; kāṅkṣhitam—coveted for; naḥ—by us; rājyam—kingdom; bhogāḥ—pleasures; sukhāni—happiness; cha—also; te—they; ime—these; avasthitāḥ—stan; yuddhe—for battle; prāṇān—lives; tyaktvā—giving up; dhanāni—wealth; cha—also.

O Krishna, I do not desire the victory, kingdom, or the happiness accruing it. Of what avail will be a kingdom, pleasures, or even life itself, when the very persons for whom we covet them, are standing before us for battle?

Arjun’s confusion arose from the fact that killing itself was considered a sinful act; then to kill one’s relatives seemed an even more grossly evil act. Even if he did engage in such a heartless act for the sake of the kingdom, Arjun felt that victory would not give him eventual happiness. He would be unable to share its glory with his friends and relatives, whom he would have to kill to achieve this victory.

Here, Arjun is displaying a lower set of sensibilities, and confusing them for noble ones. Indifference to worldly possessions and material prosperity is a praiseworthy spiritual virtue, but Arjun is not experiencing spiritual sentiments. Rather, his delusion is masquerading as words of compassion. Virtuous sentiments bring internal harmony, satisfaction, and the joy of the soul. If Arjun’s compassion was at the transcendental platform, he would have been elevated by the sentiment. But his experience is quite to the contrary—he is feeling discord in his mind and intellect, dissatisfaction with the task at hand, and deep unhappiness within. The effect of the sentiment upon him indicates that his compassion is stemming from delusion.

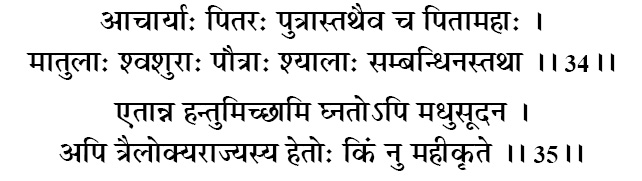

āchāryāḥ pitaraḥ putrās tathaiva cha pitāmahāḥ

mātulāḥ śhvaśhurāḥ pautrāḥ śhyālāḥ sambandhinas tathā

etān na hantum ichchhāmi ghnato ’pi madhusūdana

api trailokya-rājyasya hetoḥ kiṁ nu mahī-kṛite

āchāryāḥ—teachers; pitaraḥ—fathers; putrāḥ—sons; tathā—as well; eva—indeed; cha—also; pitāmahāḥ—grandfathers; mātulāḥ—maternal uncles; śhvaśhurāḥ—fathers-in-law; pautrāḥ—grandsons; śhyālāḥ—brothers-in-law; sambandhinaḥ—kinsmen; tathā—as well; etān—these; na—not; hantum—to slay; ichchhāmi—I wish; ghnataḥ—killed; api—even though; madhusūdana—Shree Krishna, killer of the demon Madhu; api—even though; trai-lokya-rājyasya—dominion over three worlds; hetoḥ—for the sake of; kim nu—what to speak of; mahī-kṛite—for the earth.

Teachers, fathers, sons, grandfathers, maternal uncles, grandsons, fathers-in-law, grand-nephews, brothers-in-law, and other kinsmen are present here, staking their lives and riches. O Madhusudan, I do not wish to slay them, even if they attack me. If we kill the sons of Dhritarasthra, O Janardan, what satisfaction will we derive from the dominion over the three worlds, what to speak of this Earth?

Dronacharya and Kripacharya were Arjun’s teachers; Bheeshma and Somadatta were his grand-uncles; people like Bhurishrava (son of Somdatta) were like his father; Purujit, Kuntibhoj, Shalya, and Shakuni were his maternal uncles; the hundred sons of Dhritarashtra were his cousin brothers; Lakshman (Duryodhan’s son) was like his child. Arjun refers to all the varieties of his relatives present on the battlefield. He uses the word api (which means “even though”) twice. Firstly, “Why should they wish to kill me, even though I am their relative and well-wisher?” Secondly, “Even though they may desire to slay me, why should I wish to slay them?”

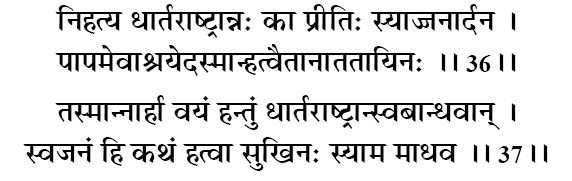

nihatya dhārtarāṣhṭrān naḥ kā prītiḥ syāj janārdana

pāpam evāśhrayed asmān hatvaitān ātatāyinaḥ

tasmān nārhā vayaṁ hantuṁ dhārtarāṣhṭrān sa-bāndhavān

sva-janaṁ hi kathaṁ hatvā sukhinaḥ syāma mādhava

nihatya—by killing; dhārtarāṣhṭrān—the sons of Dhritarashtra; naḥ—our; kā—what; prītiḥ—pleasure; syāt—will there be; janārdana—he who looks after the public, Shree Krishna; pāpam—vices; eva—certainly; āśhrayet—must come upon; asmān—us; hatvā—by killing; etān—all these; ātatāyinaḥ—aggressors; tasmāt—hence; na—never; arhāḥ—behoove; vayam—we; hantum—to kill; dhārtarāṣhṭrān—the sons of Dhritarashtra; sa-bāndhavān—along with friends; sva-janam—kinsmen; hi—certainly; katham—how; hatvā—by killing; sukhinaḥ—happy; syāma—will we become; mādhava—Shree Krishna, the husband of Yogmaya.

O Maintainer of all living entities, what pleasure will we derive from killing the sons of Dhritarasthra? Even though they may be aggressors, sin will certainly come upon us if we slay them. Hence, it does not behoove us to kill our own cousins, the sons of Dhritarashtra, and friends. O Madhav (Krishna), how can we hope to be happy by killing our own kinsmen?

Having said “even though” twice in the last verse to justify his intention not to slay his relatives, Arjun again says, “Even though I were to kill them, what pleasure would I derive from such a victory?”

Fighting and killing is in most situations an ungodly act that brings with it feelings of repentance and guilt. The Vedas state that non-violence is a great virtue, and except in the extreme cases violence is a sin: mā hinsyāt sarvā bhūtāni [v3] “Do not kill any living being.” Here, Arjun does not wish to kill his relatives, for he considers it to be a sin. However, the Vasiṣhṭh Smṛiti (verse 3.19) states that there are six kinds of aggressors against whom we have the right to defend ourselves: those who set fire to one’s property, those who poison one’s food, those who seek to murder, those who wish to loot wealth, those who come to kidnap one’s wife, and those who usurp one’s kingdom. The Manu Smṛiti (8.351) states that if one kills such an aggressor in self-defense, it is not considered a sin.

yady apy ete na paśhyanti lobhopahata-chetasaḥ

kula-kṣhaya-kṛitaṁ doṣhaṁ mitra-drohe cha pātakam

kathaṁ na jñeyam asmābhiḥ pāpād asmān nivartitum

kula-kṣhaya-kṛitaṁ doṣhaṁ prapaśhyadbhir janārdana

yadi api—even though; ete—they; na—not; paśhyanti—see; lobha—greed; upahata—overpowered; chetasaḥ—thoughts; kula-kṣhaya-kṛitam—in annihilating their relatives; doṣham—fault; mitra-drohe—to wreak treachery upon friends; cha—and; pātakam—sin; katham—why; na—not; jñeyam—should be known; asmābhiḥ—we; pāpāt—from sin; asmāt—these; nivartitum—to turn away; kula-kṣhaya—killing the kindered; kṛitam—done; doṣham—crime; prapaśhyadbhiḥ—who can see; janārdana—he who looks after the public, Shree Krishna.

Their thoughts are overpowered by greed and they see no wrong in annihilating their relatives or wreaking treachery upon friends. Yet, O Janardan (Krishna), why should we, who can clearly see the crime in killing our kindred, not turn away from this sin?

Although a warrior by occupation, Arjun abhorred unnecessary violence. An incident at the end of the battle of Mahabharat reveals this side of his character. The hundred Kauravas had been killed, but in revenge, Ashwatthama, son of Dronacharya, crept into the Pandava camp at night and killed the five sons of Draupadi while they were sleeping. Arjun caught Ashwatthama, tied him like an animal, and brought him to the feet of Draupadi, who was crying. However, being soft-hearted and forgiving, she said that because Ashwatthama was the son of their Guru, Dronacharya, he should be forgiven. Bheem, on the other hand, wanted Ashwatthama to be killed immediately. In a dilemma, Arjun looked for a solution toward Shree Krishna, who said, “A respect-worthy Brahmin must be forgiven even if he may have temporarily fallen from virtue. But a person who approaches to kill with a lethal weapon must certainly be punished.” Arjun understood Shree Krishna’s equivocal instructions. He did not kill Ashwatthama; instead he cut the Brahmin tuft behind his head, removed the jewel from his forehead, and expelled him from the camp. So, Arjun’s very nature is to shun violence wherever possible. In this particular situation, he says that he knows it is improper to kill kindred and elders:

ṛitvikpurohitāchāryair mātulātithisanśhritaiḥ

bālavṛiddhāturair vaidyair jñātisaṁbandhibāndhavaiḥ

(Manu Smṛiti 4.179) [v4]

“One should not quarrel with the Brahmin who performs the fire sacrifice, the family priest, teacher, maternal uncle, guest, those who are dependent upon one, children, elders, and relatives.” Arjun thus concluded that being overpowered by greed, the Kauravas might have deviated from propriety and had lost their discrimination, but why should he, who did not have any sinful motive, engage in such an abominable act?

kula-kṣhaye praṇaśhyanti kula-dharmāḥ sanātanāḥ

dharme naṣhṭe kulaṁ kṛitsnam adharmo ’bhibhavaty uta

kula-kṣhaye—in the destruction of a dynasty; praṇaśhyanti—are vanquished; kula-dharmāḥ—family traditions; sanātanāḥ—eternal; dharme—religion; naṣhṭe—is destroyed; kulam—family; kṛitsnam—the whole; adharmaḥ—irreligion; abhibhavati—overcome; uta—indeed.

When a dynasty is destroyed, its traditions get vanquished, and the rest of the family becomes involved in irreligion.

Families have age-old traditions and time-honored customs, in accordance with which, elders in the family pass on noble values and ideals to their next generation. These traditions help family members follow human values and religious propriety. If the elders die prematurely, their succeeding generations become bereft of family guidance and training. Arjun points this out by saying that when dynasties get destroyed, their traditions die with them, and the remaining members of the family develop irreligious and wanton habits, thereby losing their chance for spiritual emancipation. Thus according to him, the elders of the family should never be slain.

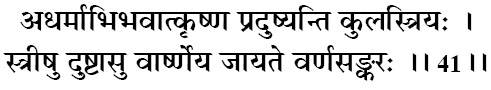

adharmābhibhavāt kṛiṣhṇa praduṣhyanti kula-striyaḥ

strīṣhu duṣhṭāsu vārṣhṇeya jāyate varṇa-saṅkaraḥ

adharma—irreligion; abhibhavāt—preponderance; kṛiṣhṇa—Shree Krishna; praduṣhyanti—become immoral; kula-striyaḥ—women of the family; strīṣhu—of women; duṣhṭāsu—becme immoral; vārṣhṇeya—descendant of Vrishni; jāyate—are born; varṇa-saṅkaraḥ—unwanted progeny.

With the preponderance of vice, O Krishna, the women of the family become immoral; and from the immorality of women, O descendent of Vrishni, unwanted progeny are born.

The Vedic civilization accorded a very high place in society to women, and laid great importance on the need for women to be virtuous. Hence, the Manu Smṛiti states: yatra nāryas tu pūjyante ramante tatra devatāḥ (3.56) [v5] “Wherever women lead chaste and virtuous lives, and for their purity they are worshipped by the rest of society, there the celestial gods become joyous.” However, when women become immoral, then irresponsible men take advantage by indulging in adultery, and thus unwanted children are born.

saṅkaro narakāyaiva kula-ghnānāṁ kulasya cha

patanti pitaro hy eṣhāṁ lupta-piṇḍodaka-kriyāḥ

saṅkaraḥ—unwanted children; narakāya—hellish; eva—indeed; kula-ghnānām—for those who destroy the family; kulasya—of the family; and—also; patanti—fall; pitaraḥ—ancestors; hi—verily; eṣhām—their; lupta—deprived of; piṇḍodaka-kriyāḥ—performances of sacrifical offereings.

An increase in unwanted children results in hellish life both for the family and for those who destroy the family. Deprived of the sacrificial offerings, the ancestors of such corrupt families also fall.

doṣhair etaiḥ kula-ghnānāṁ varṇa-saṅkara-kārakaiḥ

utsādyante jāti-dharmāḥ kula-dharmāśh cha śhāśhvatāḥ

doṣhaiḥ—through evil deeds; etaiḥ—these; kula-ghnānām—of those who destroy the family; varṇa-saṅkara—unwanted progeny; kārakaiḥ—causing; utsādyante—are ruined; jāti-dharmāḥ—social and family welfare activities; kula-dharmāḥ—family traditions; cha—and; śhāśhvatāḥ—eternal.

Through the evil deeds of those who destroy the family tradition and thus give rise to unwanted progeny, a variety of social and family welfare activities are ruined.

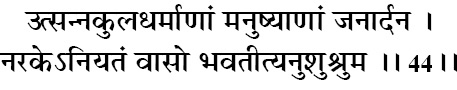

utsanna-kula-dharmāṇāṁ manuṣhyāṇāṁ janārdana

narake 'niyataṁ vāso bhavatītyanuśhuśhruma

utsanna—destroyed; kula-dharmāṇām—whose family traditions; manuṣhyāṇām—of such human beings; janārdana—he who looks after the public, Shree Krishna; narake—in hell; aniyatam—indefinite; vāsaḥ—dwell; bhavati—is; iti—thus; anuśhuśhruma—I have heard from the learned.

O Janardan (Krishna), I have heard from the learned that those who destroy family traditions dwell in hell for an indefinite period of time.

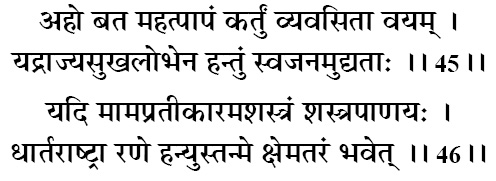

aho bata mahat pāpaṁ kartuṁ vyavasitā vayam

yad rājya-sukha-lobhena hantuṁ sva-janam udyatāḥ

yadi mām apratīkāram aśhastraṁ śhastra-pāṇayaḥ

dhārtarāṣhṭrā raṇe hanyus tan me kṣhemataraṁ bhavet

aho—alas; bata—how; mahat—great; pāpam—sins; kartum—to perform; vyavasitāḥ—have decided; vayam—we; yat—because; rājya-sukha-lobhena—driven by the desire for kingly pleasure; hantum—to kill; sva-janam—kinsmen; udyatāḥ—intending; yadi—if; mām—me; apratīkāram—unresisting; aśhastram—unarmed; śhastra-pāṇayaḥ—those with weapons in hand; dhārtarāṣhṭrāḥ—the sons of Dhritarashtra; raṇe—on the battlefield; hanyuḥ—shall kill; tat—that; me—to me; kṣhema-taram—better; bhavet—would be.

Alas! How strange it is that we have set our mind to perform this great sin. Driven by the desire for kingly pleasures, we are intent on killing our own kinsmen. It will be better if, with weapons in hand, the sons of Dhritarashtra kill me unarmed and unresisting on the battlefield.

Arjun mentioned a number of evils that would come from the impending battle, but he was not able to see that evil would actually prevail if these wicked people were allowed to thrive in society. He uses the word aho to express surprise. The word bata means “horrible results”. Arjun is saying, “How surprising it is that we have decided to commit sin by engaging in this war, even though we know of its horrifying consequences.”

As often happens, people are unable to see their own mistakes and instead attribute them to situations and to others. Similarly, Arjun felt that the sons of Dhritarashtra were motivated by greed, but he could not see that his outpouring of compassion was not a transcendental sentiment, but materialistic infatuation based on the ignorance of being the body. The problem with all of Arjun’s arguments was that he was using them to justify his delusion that had been created from his bodily attachment, weakness of heart, and dereliction of duty. Shree Krishna explains the reasons why Arjun’s arguments were defective in subsequent chapters.

sañjaya uvācha

evam uktvārjunaḥ saṅkhye rathopastha upāviśhat

visṛijya sa-śharaṁ chāpaṁ śhoka-saṁvigna-mānasaḥ

sañjayaḥ uvācha—Sanjay said; evam uktvā—speaking thus; arjunaḥ—Arjun; saṅkhye—in the battlefield; ratha upasthe—on the chariot; upāviśhat—sat; visṛijya—casting aside; sa-śharam—along with arrows; chāpam—the bow; śhoka—with grief; saṁvigna—distressed; mānasaḥ—mind.

Sanjay said: Speaking thus, Arjun cast aside his bow and arrows, and sank into the seat of his chariot, his mind in distress and overwhelmed with grief.

Often while speaking, a person gets carried away by the sentiments, and so Arjun’s despondency, which he began expressing in verse 1.28, has now reached a climax. He has given up the struggle to engage in his dhārmic duty in desperate resignation, which is entirely opposite to the state of self-surrender to God in knowledge and devotion. It is appropriate to clarify at this point that Arjun was not a novice bereft of spiritual knowledge. He had been to the celestial abodes and had received instructions from his father Indra, the king of heaven. In fact, he was Nar in his past life and hence situated in transcendental knowledge (Nar-Narayan were twin descensions, where Nar was a perfected soul and Narayan was the Supreme Lord). The proof of this was the fact that before the battle of Mahabharat, Arjun chose Shree Krishna on his side, leaving the entire Yadu army for Duryodhan. He possessed the firm conviction that if the Lord was on his side he would never lose. However, Shree Krishna desired to speak the message of the Bhagavad Gita for the benefit of posterity, and so at the opportune moment he deliberately created confusion in Arjun’s mind.