In this chapter, Shree Krishna explains that all beings are compelled to work by their intrinsic modes of nature, and nobody can remain without action for even a moment. Those who display external renunciation by donning the ochre robes, but internally dwell upon sense objects, are hypocrites. Superior to them are those who practice karm yog, and continue to engage in action externally, but give up attachment from within. Shree Krishna then stresses that all living beings have responsibilities to fulfill as integral parts of the system of God’s creation. When we execute our prescribed duties as an obligation to God, such work becomes yajña (sacrifice). The performance of yajña is naturally pleasing to the celestial gods, and they bestow us with material prosperity. Such yajña causes the rains to fall, and rain begets grains which are necessary for sustenance of life. Those who do not accept their responsibility in this cycle are sinful; they live only for the delight of their senses, and their lives are in vain.

Shree Krishna then explains that unlike the rest of humankind, the enlightened souls who are situated in the self are not obliged to fulfill bodily responsibilities, for they are executing higher responsibilities at the level of the soul. However, if they abandon their social duties, it creates discord in the minds of common people, who tend to follow in the footsteps of the great ones. So, to set a good example for the world to emulate, the wise should continue working, although without any motive for personal reward. This will prevent the ignorant from prematurely abandoning their prescribed duties. It was for this purpose that enlightened kings in the past, such as King Janak and others, performed their works.

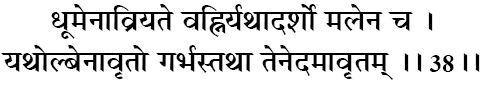

Arjun then asks why people commit sinful acts, even unwillingly, as if by force. The Supreme Lord explains that the all-devouring sinful enemy of the world is lust alone. As a fire is covered by smoke, and a mirror is masked by dust, in the same way desire shrouds one’s knowledge and drags away the intellect. Shree Krishna then gives the clarion call to Arjun to slay this enemy called desire, which is the embodiment of sin, and bring his senses, mind, and intellect under control.

arjuna uvācha

jyāyasī chet karmaṇas te matā buddhir janārdana

tat kiṁ karmaṇi ghore māṁ niyojayasi keśhava

vyāmiśhreṇeva vākyena buddhiṁ mohayasīva me

tad ekaṁ vada niśhchitya yena śhreyo ’ham āpnuyām

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; jyāyasī—superior; chet—if; karmaṇaḥ—than fruitive action; te—by you; matā—is considered; buddhiḥ—intellect; janārdana—he who looks after the public, Krishna; tat—then; kim—why; karmaṇi—action; ghore—terrible; mām—me; niyojayasi—do you engage; keśhava—Krishna, the killer of the demon named Keshi; vyāmiśhreṇa iva—by your apparently ambiguous; vākyena—words; buddhim—intellect; mohayasi—I am getting bewildered; iva—as it were; me—my; tat—therefore; ekam—one; vada—please tell; niśhchitya—decisively; yena—by which; śhreyaḥ—the highest good; aham—I; āpnuyām—may attain.

Arjun said: O Janardan, if you consider knowledge superior to action, then why do you ask me to wage this terrible war? My intellect is bewildered by your ambiguous advice. Please tell me decisively the one path by which I may attain the highest good.

Chapter one introduced the setting in which Arjun’s grief and lamentation arose, creating a reason for Shree Krishna to give spiritual instructions. In chapter two, the Lord first explained knowledge of the immortal self. He then reminded Arjun of his duty as a warrior, and said that performing it would result in glory and the celestial abodes. After prodding Arjun to do his occupational work as a Kshatriya, Shree Krishna then revealed a superior principle—the science of karm yog—and asked Arjun to detach himself from the fruits of his works. In this way, bondage-creating karmas would be transformed into bondage-breaking karmas. He termed the science of working without desire for rewards as buddhi yog, or Yog of the intellect. By this, he meant that the mind should be detached from worldly temptations by controlling it with a resolute intellect; and the intellect should be made unwavering through the cultivation of spiritual knowledge. He did not suggest that actions should be given up, but rather that attachment to the fruits of actions should be given up.

Arjun misunderstood Shree Krishna’s intention, thinking that if knowledge is superior to action, then why should he perform the ghastly duty of waging this war? Hence, he says, “By making contradictory statements, you are bewildering my intellect. I know you are merciful and your desire is not to baffle me, so please dispel my doubt.”

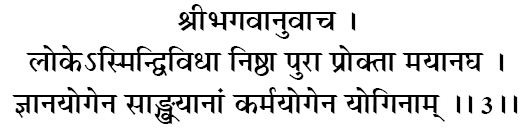

śhrī bhagavān uvācha

loke ’smin dvi-vidhā niṣhṭhā purā proktā mayānagha

jñāna-yogena sāṅkhyānāṁ karma-yogena yoginām

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Blessed Lord said; loke—in the world; asmin—this; dvi-vidhā—two kinds of; niṣhṭhā—faith; purā—previously; proktā—explained; mayā—by me (Shree Krishna); anagha—sinless; jñāna-yogena—through the path of knowledge; sānkhyānām—for those inclined toward contemplation; karma-yogena—through the path of action; yoginām—of the yogis.

The Blessed Lord said: O sinless one, the two paths leading to enlightenment were previously explained by me: the path of knowledge, for those inclined toward contemplation, and the path of work for those inclined toward action.

In verse 2.39, Shree Krishna explained the two paths leading to spiritual perfection. The first is the acquisition of knowledge through the analytical study of the nature of the soul and its distinction from the body. Shree Krishna refers to this as sānkhya yog. People with a philosophic bend of mind are inclined toward this path of knowing the self through intellectual analysis. The second is the process of working in the spirit of devotion to God, or karm yog. Shree Krishna also calls this buddhi yog¸ as explained in the previous verse. Working in this manner purifies the mind, and knowledge naturally awakens in the purified mind, thus leading to enlightenment.

Amongst people interested in the spiritual path, there are those who are inclined toward contemplation and then there are those inclined to action. Hence, both these paths have existed ever since the soul’s aspiration for God-realization has existed. Shree Krishna touches upon both of them since his message is meant for people of all temperaments and inclinations.

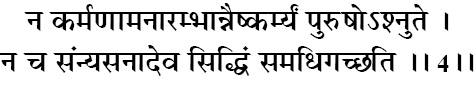

na karmaṇām anārambhān naiṣhkarmyaṁ puruṣho ’śhnute

na cha sannyasanād eva siddhiṁ samadhigachchhati

na—not; karmaṇām—of actions; anārambhāt—by abstaining from; naiṣhkarmyam—freedom from karmic reactions; puruṣhaḥ—a person; aśhnute—attains; na—not; cha—and; sannyasanāt—by renunciation; eva—only; siddhim—perfection; samadhigachchhati—attains.

One cannot achieve freedom from karmic reactions by merely abstaining from work, nor can one attain perfection of knowledge by mere physical renunciation.

The first line of this verse refers to the karm yogi (follower of the discipline of work), and the second line refers to the sānkhya yogi (follower of the discipline of knowledge).

In the first line, Shree Krishna says that mere abstinence from work does not result in a state of freedom from karmic reactions. The mind continues to engage in fruitive thoughts, and since mental work is also a form of karma, it binds one in karmic reactions, just as physical work does. A true karm yogi must learn to work without any attachment to the fruits of actions. This requires cultivation of knowledge in the intellect. Hence, philosophic knowledge is also necessary for success in karm yog.

In the second line, Shree Krishna declares that the sānkhya yogi cannot attain the state of knowledge merely by renouncing the world and becoming a monk. One may give up the physical objects of the senses, but true knowledge cannot awaken as long as the mind remains impure. The mind has a tendency to repeat its previous thoughts. Such repetition creates a channel within the mind, and new thoughts flow irresistibly in the same direction. Out of previous habit, the materially contaminated mind keeps running in the direction of anxiety, stress, fear, hatred, envy, attachment, and the whole gamut of material emotions. Thus, realized knowledge will not appear in an impure heart by mere physical renunciation. It must be accompanied by congruent action that purifies the mind and intellect. Therefore, action is also necessary for success in sānkhya yog.

It is said that devotion without philosophy is sentimentality, and philosophy without devotion is intellectual speculation. Action and knowledge are necessary in both karm yog and sānkhya yog. It is only their proportion that varies, creating the difference between the two paths.

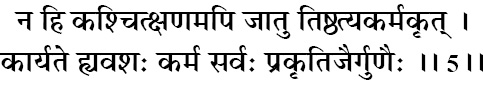

na hi kaśhchit kṣhaṇam api jātu tiṣhṭhatyakarma-kṛit

kāryate hyavaśhaḥ karma sarvaḥ prakṛiti-jair guṇaiḥ

na—not; hi—certainly; kaśhchit—anyone; kṣhaṇam—a moment; api—even; jātu—ever; tiṣhṭhati—can remain; akarma-kṛit—without action; kāryate—are performed; hi—certainly; avaśhaḥ—helpless; karma—work; sarvaḥ—all; prakṛiti-jaiḥ—born of material nature; guṇaiḥ—by the qualities.

There is no one who can remain without action even for a moment. Indeed, all beings are compelled to act by their qualities born of material nature (the three guṇas).

Some people think that action refers only to professional work, and not to daily activities such as eating, drinking, sleeping, waking and thinking. So when they renounce their profession, they think they are not performing actions. But Shree Krishna considers all activities performed with the body, mind, and tongue as actions. Hence, he tells Arjun that complete inactivity is impossible even for a moment. If we simply sit down, it is an activity; if we lie down, that is also an activity; if we fall asleep, the mind is still engaged in dreaming; even in deep sleep, the heart and other bodily organs are functioning. Thus Shree Krishna declares that for human beings inactivity is an impossible state to reach, since the body-mind-intellect mechanism is compelled by its own make-up of the three guṇas (sattva, rajas, and tamas) to perform work in the world. The Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam contains a similar verse:

na hi kaśhchit kṣhaṇam api jātu tiṣhṭhaty akarma-kṛit

kāryate hy avaśhaḥ karma guṇaiḥ svābhāvikair balāt (6.1.53) [v1]

“Nobody can remain inactive for even a moment. Everyone is forced to act by their modes of nature.”

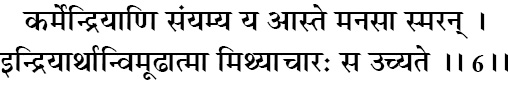

karmendriyāṇi sanyamya ya āste manasā smaran

indriyārthān vimūḍhātmā mithyāchāraḥ sa uchyate

karma-indriyāṇi—the organs of action; sanyamya—restrain; yaḥ—who; āste—remain; manasā—in the mind; smaran—to remember; indriya-arthān—sense objects; vimūḍha-ātmā—the deluded; mithyā-āchāraḥ—hypocrite; saḥ—they; uchyate—are called.

Those who restrain the external organs of action, while continuing to dwell on sense objects in the mind, certainly delude themselves and are to be called hypocrites.

Attracted by the lure of an ascetic life, people often renounce their work, only to discover later that their renunciation is not accompanied by an equal amount of mental and intellectual withdrawal from the sensual fields. This creates a situation of hypocrisy where one displays an external show of religiosity while internally living a life of ignoble sentiments and base motives. Hence, it is better to face the struggles of the world as a karm yogi, than to lead the life of a false ascetic. Running away from the problems of life by prematurely taking sanyās is not the way forward in the journey of the evolution of the soul. Saint Kabir stated sarcastically:

mana na raṅgāye ho, raṅgāye yogī kapaṛā

jatavā baḍhāe yogī dhuniyā ramaule, dahiyā baḍhāe yogī bani gayele bakarā [v2]

“O Ascetic Yogi, you have donned the ochre robes, but you have ignored dyeing your mind with the color of renunciation. You have grown long locks of hair and smeared ash on your body (as a sign of detachment). But without the internal devotion, the external beard you have sprouted only makes you resemble a goat.” Shree Krishna states in this verse that people who externally renounce the objects of the senses while continuing to dwell upon them in the mind are hypocrites, and they delude themselves.

The Puranas relate the story of two brothers, Tavrit and Suvrit, to illustrate this point. The brothers were walking from their house to hear the Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam discourse at the temple. On the way, it began raining heavily, so they ran into the nearest building for shelter. To their dismay, they found themselves in a brothel, where women of disrepute were dancing to entertain their guests. Tavrit, the elder brother, was appalled and walked out into the rain, to continue to the temple. The younger brother, Suvrit, felt no harm in sitting there for a while to escape getting wet in the rain.

Tavrit reached the temple and sat for the discourse, but in his mind he became remorseful, “O how boring this is! I made a dreadful mistake; I should have remained at the brothel. My brother must be enjoying himself greatly in revelry there.” Suvrit, on the other hand, started thinking, “Why did I remain in this house of sin? My brother is so holy; he is bathing his intellect in the knowledge of the Bhāgavatam. I too should have braved the rain and reached there. After all, I am not made of salt that I would have melted in a little bit of rain.”

When the rain stopped, both started out in the direction of the other. The moment they met, lightning struck them and they both died on the spot. The Yamdoots (servants of the god of Death) came to take Tavrit to hell. Tavrit complained, “I think you have made a mistake. I am Tavrit. It was my brother who was sitting at the brothel a little while ago. You should be taking him to hell.” The Yamdoots replied, “We have made no mistake. He was sitting there to avoid the rain, but in his mind he was longing to be at the Bhāgavatam discourse. On the other hand, while you were sitting and hearing the discourse, your mind was yearning to be at the brothel.” Tavrit was doing exactly what Shree Krishna declares in this verse; he had externally renounced the objects of the senses, but was dwelling upon them in the mind. This was the improper kind of renunciation. The next verse states the proper kind of renunciation.

yas tvindriyāṇi manasā niyamyārabhate ’rjuna

karmendriyaiḥ karma-yogam asaktaḥ sa viśhiṣhyate

yaḥ—who; tu—but; indriyāṇi—the senses; manasā—by the mind; niyamya—control; ārabhate—begins; arjuna—Arjun; karma-indriyaiḥ—by the working senses; karma-yogam—karm yog; asaktaḥ—without attachment; saḥ—they; viśhiṣhyate—are superior.

But those karm yogis who control their knowledge senses with the mind, O Arjun, and engage the working senses in working without attachment, are certainly superior.

The word karm yog has been used in this verse. It consists of two main concepts: karm (occupational duties) and Yog (union with God). Hence, a karm yogi is one who performs worldly duties while keeping the mind attached to God. Such a karm yogi is not bound by karma even while performing all kinds of works. This is because what binds one to the law of karma is not actions, but the attachment to the fruits of those actions. And a karm yogi has no attachment to the fruits of action. On the other hand, a false renunciant renounces action, but does not forsake attachment, and thus remains bound in the law of karma.

Shree Krishna says here that a person in household life who practices karm yog is superior to the false renunciant who continues to dwell on the objects of the senses in the mind. Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj contrasts these two situations very beautifully:

mana hari meṅ tana jagat meṅ, karmayog yehi jāna

tana hari meṅ mana jagat meṅ, yaha mahāna ajñāna

(Bhakti Śhatak verse 84) [v3]

“When one works in the world with the body, but keeps the mind attached to God, know it to be karm yog. When one engages in spirituality with the body, but keeps the mind attached to the world, know it to be hypocrisy.”

niyataṁ kuru karma tvaṁ karma jyāyo hyakarmaṇaḥ

śharīra-yātrāpi cha te na prasiddhyed akarmaṇaḥ

niyatam—constantly; kuru—perform; karma—Vedic duties; tvam—you; karma—action; jyāyaḥ—superior; hi—certainly; akarmaṇaḥ—than inaction; śharīra—bodily; yātrā—maintenance; api—even; cha—and; te—your; na prasiddhyet—would not be possible; akarmaṇaḥ—inaction.

You should thus perform your prescribed Vedic duties, since action is superior to inaction. By ceasing activity, even your bodily maintenance will not be possible.

Until the mind and intellect reach a state where they are absorbed in God-consciousness, physical work performed in an attitude of duty is very beneficial for one’s internal purification. Hence, the Vedas prescribe duties for humans, to help them discipline their mind and senses. In fact, laziness is described as one of the biggest pitfalls on the spiritual path:

ālasya hi manuṣhyāṇāṁ śharīrastho mahān ripuḥ

nāstyudyamasamo bandhūḥ kṛitvā yaṁ nāvasīdati [v4]

“Laziness is the greatest enemy of humans, and is especially pernicious since it resides in their own body. Work is their most trustworthy friend, and is a guarantee against downfall.” Even the basic bodily activities like eating, bathing, and maintaining proper health require work. These obligatory actions are called nitya karm. To neglect these basic maintenance activities is not a sign of progress, but an indication of slothfulness, leading to emaciation and weakness of both body and mind. On the other hand, a cared for and nourished body is a positive adjunct on the road to spirituality. Thus, the state of inertia does not lend itself either to material or spiritual achievement. For the progress of our own soul, we should embrace the duties that help elevate and purify our mind and intellect.

yajñārthāt karmaṇo ’nyatra loko ’yaṁ karma-bandhanaḥ

tad-arthaṁ karma kaunteya mukta-saṅgaḥ samāchara

yajña-arthāt—for the sake of sacrifice; karmaṇaḥ—than action; anyatra—else; lokaḥ—material world; ayam—this; karma-bandhanaḥ—bondage through one’s work; tat—of him; artham—for the sake of; karma—action; kaunteya—Arjun, the son of Kunti; mukta-saṅgaḥ—free from attachment; samāchara—perform properly.

Work must be done as a yajña (sacrifice) to the Supreme Lord; otherwise, work causes bondage in this material world. Therefore, O son of Kunti, perform your prescribed duties, without being attached to the results, for the satisfaction of God.

A knife in the hands of a robber is a weapon for intimidation or committing murder, but in the hands of a surgeon is an invaluable instrument used for saving people’s lives. The knife in itself is neither murderous nor benedictory—its effect is determined by how it is used. As Shakespeare said: “For there is nothing good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” Similarly, work in itself is neither good nor bad. Depending upon the state of the mind, it can be either binding or elevating. Work done for the enjoyment of one’s senses and the gratification of one’s pride is the cause of bondage in the material world, while work performed as yajña (sacrifice) for the pleasure of the Supreme Lord liberates one from the bonds of Maya and attracts divine grace. Since it is our nature to perform actions, we are forced to work in one of the two modes. We cannot remain without working for even a moment as our mind cannot remain still.

If we do not perform actions as a sacrifice to God, we will be forced to work to gratify our mind and senses. Instead, when we perform work as a sacrifice, we then look upon the whole world and everything in it as belonging to God, and therefore, meant for utilization in his service. A beautiful ideal for this was established by King Raghu, the ancestor of Lord Ram. Raghu performed the Viśhwajit sacrifice, which requires donating all of one’s possessions in charity.

sa viśhwajitam ājahre yajñaṁ sarvasva dakṣhiṇam

ādānaṁ hi visargāya satāṁ vārimuchām iva

(Raghuvanśh 4.86) [v5]

“Raghu performed the Viśhwajit yajña with the thought that just as clouds gather water from the Earth, not for their enjoyment, but to shower it back upon the Earth, similarly, all he possessed as a king had been gathered from the public in taxes, not for his pleasure, but for the pleasure of God. So he decided to use his wealth to please God by serving his citizens with it.” After the yajña, Raghu donated all his possessions to his citizens. Then, donning the rags of a beggar and holding an earthen pot, he went out to beg for his meal.

While resting under a tree, he heard a group of people discussing, “Our king is so benevolent. He has given away everything in charity.” Raghu was pained on hearing his praise and spoke out, “What are you discussing?” They answered, “We are praising our king. There is nobody in the world as charitable as him.” Raghu retorted, “Do not ever say that again. Raghu has given nothing.” They said, “What kind of person are you who are criticizing our king? Everyone knows that Raghu has donated everything he owned.” Raghu replied, “Go and ask your king that when he came into this world did he possess anything? He was born empty-handed, is it not? Then what was his that he has given away?”

This is the spirit of karm yog, in which we see the whole world as belonging to God, and hence meant for the satisfaction of God. We then perform our duties not for gratifying our mind and senses, but for the pleasure of God. Lord Vishnu instructed the Prachetas in this fashion:

gṛiheṣhv āviśhatāṁ chāpi puṁsāṁ kuśhala-karmaṇām

mad-vārtā-yāta-yāmānāṁ na bandhāya gṛihā matāḥ

(Bhāgavatam 4.30.19) [v6]

“The perfect karm yogis, even while fulfilling their household duties, perform all their works as yajña to me, knowing me to be the Enjoyer of all activities. They spend whatever free time they have in hearing and chanting my glories. Such people, though living in the world, never get bound by their actions.”

saha-yajñāḥ prajāḥ sṛiṣhṭvā purovācha prajāpatiḥ

anena prasaviṣhyadhvam eṣha vo ’stviṣhṭa-kāma-dhuk

saha—along with; yajñāḥ—sacrifices; prajāḥ—mankind; sṛiṣhṭvā—created; purā—in beginning; uvācha—said; prajā-patiḥ—Brahma; anena—by this; prasaviṣhyadhvam—increase prosperity; eṣhaḥ—these; vaḥ—your; astu—shall be; iṣhṭa-kāma-dhuk—bestower of all wishes.

In the beginning of creation, Brahma created living beings along with duties, and said, “Prosper in the performance of these yajñas (sacrifices), for they shall bestow upon you all you wish to achieve.”

All the elements of nature are integral parts of the system of God’s creation. All the parts of the system naturally draw from and give back to the whole. The sun lends stability to the earth and provides heat and light necessary for life to exist. Earth creates food from its soil for our nourishment and also holds essential minerals in its womb for a civilized lifestyle. The air moves the life force in our body and enables transmission of sound energy. We humans too are an integral part of the entire system of God’s creation. The air that we breathe, the Earth that we walk upon, the water that we drink, and the light that illumines our day, are all gifts of creation to us. While we partake of these gifts to sustain our lives, we also have our duties toward the integral system. Shree Krishna says that we are obligated to participate with the creative force of nature by performing our prescribed duties in the service of God. That is the yajña he expects from us.

Consider the example of a hand. It is an integral part of the body. It receives its nourishment—blood, oxygen, nutrients, etc.—from the body, and in turn, it performs necessary functions for the body. If the hand looks on this service as burdensome, and decides to get severed from the body, it cannot sustain itself for even a few minutes. It is in the performance of its yajña toward the body that the self-interest of the hand is also fulfilled. Similarly, we individual souls are tiny parts of the Supreme Soul and we all have our role to play in the grand scheme of things. When we perform our yajña toward him, our self-interest is naturally satiated.

Generally, the term yajña refers to fire sacrifice. In the Bhagavad Gita, yajña includes all the prescribed actions laid down in the scriptures, when they are done as an offering to the Supreme.

devān bhāvayatānena te devā bhāvayantu vaḥ

parasparaṁ bhāvayantaḥ śhreyaḥ param avāpsyatha

devān—celestial gods; bhāvayatā—will be pleased; anena—by these (sacrifices); te—those; devāḥ—celestial gods; bhāvayantu—will be pleased; vaḥ—you; parasparam—one another; bhāvayantaḥ—pleasing one another; śhreyaḥ—prosperity; param—the supreme; avāpsyatha—shall achieve.

By your sacrifices the celestial gods will be pleased, and by cooperation between humans and the celestial gods, prosperity will reign for all.

The celestial gods, or devatās, are in-charge of the administration of the universe. The Supreme Lord does his work of managing the universe through them. These devatās live within this material universe, in the higher planes of existence, called swarg, or the celestial abodes. The devatās are not God; they are souls like us. They occupy specific posts in the affairs of running the world. Consider the Federal government of a country. There is a Secretary of State, a Secretary of the Treasury, a Secretary of Defense, Attorney General, and so on. These are posts, and chosen people occupy those posts for a limited tenure. At the end of the tenure, the government changes and all the post-holders change too. Similarly, in administering the affairs of the world, there are posts such as Agni Dev (the god of fire), Vāyu Dev (the god of the wind), Varuṇa Dev (the god of the ocean), Indra Dev (the king of the celestial gods), etc. Souls selected by virtue of their deeds in past lives occupy these seats for a fixed number of ages, and administer the affairs of the universe. These are the devatās (celestial gods).

The Vedas mention various ceremonies and processes for the satisfaction of the celestial gods, and in turn these devatās bestow material prosperity. However, when we perform our yajña for the satisfaction of the Supreme Lord, the celestial gods are automatically appeased, just as when we water the root of a tree, the water inevitably reaches its flowers, fruits, leaves, branches, and twigs. The Skandh Purāṇ states:

archite deva deveśhe śhaṅkha chakra gadādhare

architāḥ sarve devāḥ syur yataḥ sarva gato hariḥ [v7]

“By worshipping the Supreme Lord Shree Vishnu, we automatically worship all the celestial gods, since they all derive their power from him.” Thus, the performance of yajña is naturally pleasing to the devatās, who then create prosperity for living beings by favorably adjusting the elements of material nature.

iṣhṭān bhogān hi vo devā dāsyante yajña-bhāvitāḥ

tair dattān apradāyaibhyo yo bhuṅkte stena eva saḥ

iṣhṭān—desired; bhogān—necessities of life; hi—certainly; vaḥ—unto you; devāḥ—the celestial gods; dāsyante—will grant; yajña-bhāvitāḥ—satisfied by sacrifice; taiḥ—by them; dattān—things granted; apradāya—without offering; ebhyaḥ—to them; yaḥ—who; bhuṅkte—enjoys; stenaḥ—thieves; eva—verily; saḥ—they.

The celestial gods, being satisfied by the performance of sacrifice, will grant you all the desired necessities of life. But those who enjoy what is given to them, without making offerings in return, are verily thieves.

As administrators of various processes of the universe, the devatās provide us with rain, wind, crops, vegetation, minerals, fertile soil, etc. We human beings are indebted to them for all that we receive from them. The devatās perform their duty, and expect us to perform our duty in the proper consciousness too. Since these celestial gods are all servants of the Supreme Lord, they become pleased when someone performs a sacrifice for him, and in turn assist such a soul by creating favorable material conditions. Thus, it is said that when we strongly resolve to serve God, the universe begins to cooperate with us.

However, if we begin looking upon the gifts of nature, not as means of serving the Lord but as objects of our own enjoyment, Shree Krishna calls it a thieving mentality. Often people ask the question, “I lead a virtuous life; I do not harm anyone, nor do I steal anything. But I do not believe in worshipping God, nor do I believe in him. Am I doing anything wrong?” This question is answered in the above verse. Such persons may not be doing anything wrong in the eyes of humans, but they are thieves in the eyes of God. Let us say, we walk into someone’s house, and without recognizing the owner, we sit on the sofa, eat from the refrigerator, and use the restroom. We may claim that we are not doing anything wrong, but we will be considered thieves in the eyes of the law, because the house does not belong to us. Similarly, the world that we live in was made by God, and everything in it belongs to him. If we utilize his creation for our pleasure, without acknowledging his dominion over it, from the divine perspective we are certainly committing theft.

The famous king in Indian history, Chandragupta, asked Chanakya Pundit, his Guru, “According to the Vedic scriptures, what is the position of the king vis-à-vis his subjects?” Chanakya Pundit replied, “The king is the servant of the subjects and nothing else. His God-given duty is to help the citizens of his kingdom progress in their journey toward God-realization.” Whether one is a king, a businessperson, a farmer, or a worker, each person, as an integral member of God’s world, is expected to do his or her duty as a service to the Supreme.

yajña-śhiṣhṭāśhinaḥ santo muchyante sarva-kilbiṣhaiḥ

bhuñjate te tvaghaṁ pāpā ye pachantyātma-kāraṇāt

yajña-śhiṣhṭa—of remnants of food offered in sacrifice; aśhinaḥ—eaters; santaḥ—saintly persons; muchyante—are released; sarva—all kinds of; kilbiṣhaiḥ—from sins; bhuñjate—enjoy; te—they; tu—but; agham—sins; pāpāḥ—sinners; ye—who; pachanti—cook (food); ātma-kāraṇāt—for their own sake.

The spiritually-minded, who eat food that is first offered in sacrifice, are released from all kinds of sin. Others, who cook food for their own enjoyment, verily eat only sin.

In the Vedic tradition, food is cooked with the consciousness that the meal is for the pleasure of God. A portion of the food items is then put in a plate and a verbal or mental prayer is made for the Lord to come and eat it. After the offering, the food in the plate is considered prasād (grace of God). All the food in the plate and the pots is then accepted as God’s grace and eaten in that consciousness. Other religious traditions follow similar customs. Christianity has the sacrament of the Eucharist, where bread and wine are consecrated and then partaken. Shree Krishna states in this verse that eating prasād (food that is first offered as sacrifice to God) releases one from sin, while those who eat food without offering commit sin.

The question may arise whether we can offer non-vegetarian items to God and then accept the remnants as his prasād. The answer to this question is that the Vedas prescribe a vegetarian diet for humans, which includes grains, pulses and beans, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, etc. Apart from the Vedic culture, many spiritually evolved souls in the history of all cultures around the world also rejected a non-vegetarian diet that makes the stomach a graveyard for animals. Even though many of them were born in meat-eating families, they gravitated to a vegetarian lifestyle as they advanced on the path of spirituality. Here are quotations from some famous thinkers and personalities advocating vegetarianism:

“To avoid causing terror to living beings, let the disciple refrain from eating meat... the food of the wise is that which is consumed by the sādhus; it does not consist of meat.” The Buddha.

“If you declare that you are naturally designed for such a diet, then first kill for yourself what you want to eat. Do it, however, only through your own resources, unaided by cleaver or cudgel or any kind of ax.” The Roman Plutarch, in the essay, “On Eating Flesh.”

“As long as men massacre animals, they will kill each other. Indeed, he who sows the seeds of murder and pain cannot reap joy and love.” Pythagoras

“Truly man is the king of beasts, for his brutality exceeds them. We live by the death of others. We are burial places! I have since an early age abjured the use of meat...” Leonardo da Vinci.

“Nonviolence leads to the highest ethics, which is the goal of all evolution. Until we stop harming all living beings, we are all savages.” Thomas Edison.

“Flesh-eating is simply immoral, as it involves the performance of an act which is contrary to moral feeling—killing.” Leo Tolstoy.

“It may indeed be doubted whether butchers’ meat is anywhere a necessary of life… Decency nowhere requires that any man should eat butchers’ meat.” Adam Smith.

“I look my age. It is the other people who look older than they are. What can you expect from people who eat corpses?” George Bernard Shaw.

“A dead cow or sheep lying in a pasture is recognized as carrion. The same sort of carcass dressed and hung up in a butcher’s stall passes as food!” J. H. Kellogg.

“It is my view that the vegetarian manner of living, by its purely physical effect on the human temperament, would most beneficially influence the lot of mankind.” Albert Einstein

“I do feel that spiritual progress does demand at some stage that we should cease to kill our fellow creatures for the satisfaction of our bodily wants.” Mahatma Gandhi

In this verse, Shree Krishna goes further and says that even vegetation contains life, and if we eat it for our own sense enjoyment, we get bound in the karmic reactions of destroying life. The word used in the verse is ātma-kāraṇāt, meaning “for one’s individual pleasure.” However, if we eat food as remnants of yajña offered to God then the consciousness changes. We then look upon our body as the property of God, which has been put under our care for his service. And we partake of permitted food, as his grace, with the intention that it will nourish the body. In this sentiment, the entire process is consecrated to the Divine. Bharat Muni states:

vasusato kratu dakṣhau kāla kāmau dṛitiḥ kuruḥ

pururavā madravāśhcha viśhwadevāḥ prakīrtitāḥ [v8]

“Violence is caused unknowingly to living entities in the process of cooking, by the use of the pestle, fire, grinding instruments, water pot, and broom. Those who cook food for themselves become implicated in the sin. But yajña nullifies the sinful reactions.”

annād bhavanti bhūtāni parjanyād anna-sambhavaḥ

yajñād bhavati parjanyo yajñaḥ karma-samudbhavaḥ

annāt—from food; bhavanti—subsist; bhūtāni—living beings; parjanyāt—from rains; anna—of food grains; sambhavaḥ—production; yajñāt—from the performance of sacrifice; bhavati—becomes possible; parjanyaḥ—rain; yajñaḥ—performance of sacrifice; karma—prescribed duties; samudbhavaḥ—born of.

All living beings subsist on food, and food is produced by rains. Rains come from the performance of sacrifice, and sacrifice is produced by the performance of prescribed duties.

Here, Lord Krishna is describing the cycle of nature. Rain begets grains. Grains are eaten and transformed into blood. From blood, semen is created. Semen is the seed from which the human body is created. Human beings perform yajñas, and these propitiate the celestial gods, who then cause rains, and so the cycle continues.

karma brahmodbhavaṁ viddhi brahmākṣhara-samudbhavam

tasmāt sarva-gataṁ brahma nityaṁ yajñe pratiṣhṭhitam

karma—duties; brahma—in the Vedas; udbhavam—manifested; viddhi—you should know; brahma—The Vedas; akṣhara—from the Imperishable (God); samudbhavam—directly manifested; tasmāt—therefore; sarva-gatam—all-pervading; brahma—The Lord; nityam—eternally; yajñe—in sacrifice; pratiṣhṭhitam—established.

The duties for human beings are described in the Vedas, and the Vedas are manifested by God himself. Therefore, the all-pervading Lord is eternally present in acts of sacrifice.

The Vedas emanated from the breath of God: asya mahato bhūtasya niḥśhvasitametadyadṛigvedo yajurvedaḥ sāmavedo ’thavaṅgirasaḥ (Bṛihadāraṇyak Upaniṣhad 4.5.11) [v9] “The four Vedas—Ṛig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sāma Veda, Atharva Veda—all emanated from the breath of the Supreme Divine Personality.” In these eternal Vedas, the duties of humans have been laid down by God himself. These duties have been planned in such a way that through their performance materially engrossed persons may gradually learn to control their desires and slowly elevate themselves from the mode of ignorance to the mode of passion, and from the mode of passion to the mode of goodness. These duties are enjoined to be dedicated to him as yajña. Hence, duties consecrated as sacrifice to God verily become godly, of the nature of God, and non-different from him.

The Tantra Sār states yajña to be the Supreme Divine Lord himself:

yajño yajña pumāṁśh chaiva yajñaśho yajña yajñabhāvanaḥ

yajñabhuk cheti pañchātmā yajñeṣhvijyo hariḥ svayaṁ [v10]

In the Bhāgavatam (11.19.39), Shree Krishna declares to Uddhav: yajño ’haṁ bhagavattamaḥ [v11] “I, the Son of Vasudev, am Yajña.” The Vedas state: yajño vai viṣhṇuḥ [v12]“Yajña is indeed Lord Vishnu himself.” Reiterating this principle, Shree Krishna says in this verse that God is eternally present in the act of sacrifice.

evaṁ pravartitaṁ chakraṁ nānuvartayatīha yaḥ

aghāyur indriyārāmo moghaṁ pārtha sa jīvati

evam—thus; pravartitam—set into motion; chakram—cycle; na—not; anuvartayati—follow; iha—in this life; yaḥ—who; agha-āyuḥ—sinful living; indriya-ārāmaḥ—for the delight of their senses; mogham—vainly; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; saḥ—they; jīvati—live.

O Parth, those who do not accept their responsibility in the cycle of sacrifice established by the Vedas are sinful. They live only for the delight of their senses; indeed their lives are in vain.

Chakra, or cycle, means an ordered series of events. The cycle from grains to rains has been described in verse 3.14. All members of this universal wheel of action perform their duties and contribute to its smooth rotation. Since we also partake of the fruits of this natural cycle, we too must do our bounden duty in the chain.

We humans are the only ones in this chain who have been bestowed with the ability to choose our actions by our own free will. We can thus either contribute to the harmony of the cycle or bring about discord in the smooth running of this cosmic mechanism. When the majority of the people of human society accept their responsibility to live as integral parts of the universal system, material prosperity abounds and spiritual growth is engendered. Such periods become golden eras in the social and cultural history of humankind. Conversely, when a major section of humankind begins to violate the universal system and rejects its responsibility as an integral part of the cosmic system, then material nature begins to punish, and peace and prosperity become scarce.

The wheel of nature has been set up by God for disciplining, training, and elevating all living beings of varying levels of consciousness. Shree Krishna explains to Arjun that those who do not perform the yajña enjoined of them become slaves of their senses and lead a sinful existence. Thus, they live in vain. But persons conforming to the divine law become pure at heart and free from material contamination.

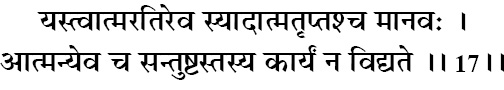

yas tvātma-ratir eva syād ātma-tṛiptaśh cha mānavaḥ

ātmanyeva cha santuṣhṭas tasya kāryaṁ na vidyate

yaḥ—who; tu—but; ātma-ratiḥ—rejoice in the self; eva—certainly; syāt—is; ātma-tṛiptaḥ—self-satisfied; cha—and; mānavaḥ—human being; ātmani—in the self; eva—certainly; cha—and; santuṣhṭaḥ—satisfied; tasya—his; kāryam—duty; na—not; vidyate—exist.

But those who rejoice in the self, who are illumined and fully satisfied in the self, for them, there is no duty.

Only those who have given up desires for external objects can rejoice and be satisfied in the self. The root of bondage is our material desires, “This should happen; that should not happen.” Shree Krishna explains a little further ahead in this chapter (in verse 3.37) that desire is the cause of all sins, consequently, it must be renounced. As explained previously (in the purport of verse 2.64), it must be borne in mind that whenever Shree Krishna says we should give up desire, he refers to material desires, and not to the aspirations for spiritual progress or the desire to realize God.

However, why do material desires arise in the first place? When we identify the self with the body, we identify with the yearnings of the body and mind as the desires of the self, and these send us spinning into the realm of Maya. Sage Tulsidas explains:

jiba jiba te hari te bilagāno taba te deha geha nija mānyo,

māyā basa swarūp bisarāyo tehi brama te dāruṇa duḥkh pāyo. [v13]

“When the soul separated itself from God, the material energy covered it in an illusion. By virtue of that illusion, it began thinking of itself as the body, and ever since, in forgetfulness of the self, it has been experiencing immense misery.”

Those who are illumined realize that the self is not material in nature, but divine, and hence imperishable. The perishable objects of the world can never fulfill the thirst of the imperishable soul, and therefore it is a folly to hanker after those sense-objects. Thus, self-illumined souls learn to unite their consciousness with God and experience his infinite bliss within them.

The karm (duties) prescribed for the materially conditioned souls are no longer applicable to such illumined souls because they have already attained the goal of all such karm. For example, as long as one is a college student, one is obliged to follow the rules of the university, but for one who has graduated and earned the degree, the rules now become irrelevant. For such liberated souls, it is said: brahmavit śhruti mūrdhnī [v14] “Those who have united themselves with God now walk on the head of the Vedas,” i.e. they have no need to follow the rules of the Vedas any longer.

The goal of the Vedas is to help unite the soul with God. Once the soul becomes God-realized, the rules of the Vedas, which helped the soul to reach that destination, now no longer apply; the soul has transcended their area of jurisdiction. For example, a pundit unites a man and woman in wedlock by performing the marriage ceremony. Once the ceremony is over, he says, “You are now husband and wife; I am leaving.” His task is over. If the wife says, “Punditji, the vows you made us take during the marriage ceremony are not being followed by my husband, the pundit will reply, “That is not my area of expertise. My duty was to get you both united in marriage and that work is over.” Similarly the Vedas are there to help unite the self with the Supreme Self. When God-realization takes place, the task of the Vedas is over. Such an enlightened soul is no longer obliged to perform the Vedic duties.

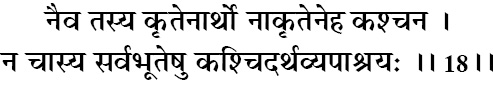

naiva tasya kṛitenārtho nākṛiteneha kaśhchana

na chāsya sarva-bhūteṣhu kaśhchid artha-vyapāśhrayaḥ

na—not; eva—indeed; tasya—his; kṛitena—by discharge of duty; arthaḥ—gain; na—not; akṛitena—without discharge of duty; iha—here; kaśhchana—whatsoever; na—never; cha—and; asya—of that person; sarva-bhūteṣhu—among all living beings; kaśhchit—any; artha—necessity; vyapāśhrayaḥ—to depend upon.

Such self-realized souls have nothing to gain or lose either in discharging or renouncing their duties. Nor do they need to depend on other living beings to fulfill their self-interest.

These self-realized personalities are situated on the transcendental platform of the soul. Their every activity is transcendental, in service of God. So the duties prescribed for worldly people at the bodily level, in accordance with the Varṇāśhram Dharma, no longer apply to them.

Here, the distinction needs to be made between karm and bhakti. Previously, Shree Krishna was talking about karm, (or prescribed worldly duties) and saying that they must be done as an offering to God. This was necessary to purify the mind, helping it rise above worldly contamination. But self-realized souls have already reached absorption in God and developed purity of mind. These transcendentalists are directly engaged in bhakti, or pure spiritual activities, such as meditation, worship, kīrtan, service to the Guru, etc. If such souls reject their worldly duties, it is not considered a sin. They may continue to perform worldly duties if they wish, but they are not obliged to do them.

Historically, Saints have been of two kinds. 1) Those like Prahlad, Dhruv, Ambarish, Prithu, and Vibheeshan, who continued to discharge their worldly duties even after attaining the transcendental platform. These were the karm yogis—externally they were doing their duties with their body while internally their minds were attached to God. 2) Those like Shankaracharya, Madhvacharya, Ramanujacharya, and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who rejected their worldly duties and accepted the renounced order of life. These were the karm sanyāsīs, who were both internally and externally, with both body and mind, engaged only in devotion to God. In this verse, Shree Krishna tells Arjun that both options exist for the self-realized sage. Now, he states this in the next verse which of these he recommends to Arjun.

tasmād asaktaḥ satataṁ kāryaṁ karma samāchara

asakto hyācharan karma param āpnoti pūruṣhaḥ

tasmāt—therefore; asaktaḥ—without attachment; satatam—constantly; kāryam—duty; karma—action; samāchara—perform; asaktaḥ—unattached; hi—certainly; ācharan—performing; karma—work; param—the Supreme; āpnoti—attains; pūruṣhaḥ—a person.

Therefore, giving up attachment, perform actions as a matter of duty, for by working without being attached to the fruits, one attains the Supreme.

From verses 3.8 to 3.16, Shree Krishna strongly urged those who have not yet reached the transcendental platform to perform their prescribed duties. In verses 3.17 and 3.18, he stated that the transcendentalist is not obliged to perform prescribed duties. So, what path is more suitable for Arjun? Shree Krishna’s recommendation for him is to be a karm yogi, and not take karm sanyās. He explains the reason for this in verses 3.20 to 3.26.

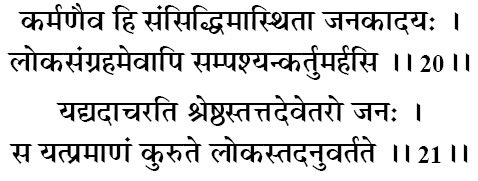

karmaṇaiva hi sansiddhim āsthitā janakādayaḥ

loka-saṅgraham evāpi sampaśhyan kartum arhasi

yad yad ācharati śhreṣhṭhas tat tad evetaro janaḥ

sa yat pramāṇaṁ kurute lokas tad anuvartate

karmaṇā—by the performace of prescribed duties; eva—only; hi—certainly; sansiddhim—perfection; āsthitāḥ—attained; janaka-ādayaḥ—King Janak and other kings; loka-saṅgraham—for the welfare of the masses; eva api—only; sampaśhyan—considering; kartum—to perfrom; arhasi—you should; yat yat—whatever; ācharati—does; śhreṣhṭhaḥ—the best; tat tat—that (alone); eva—certainly; itaraḥ—common; janaḥ—people; saḥ—they; yat—whichever; pramāṇam—standard; kurute—perform; lokaḥ—world; tat—that; anuvartate—pursues.

By performing their prescribed duties, King Janak and others attained perfection. You should also perform your work to set an example for the good of the world. Whatever actions great persons perform, common people follow. Whatever standards they set, all the world pursues.

King Janak attained perfection through karm yog, while discharging his kingly duties. Even after reaching the transcendental platform, he continued to do his worldly duties, purely for the reason that it would set a good example for the world to follow. Many other Saints did the same.

Humanity is inspired by the ideals that they see in the lives of great people. Such leaders inspire society by their example and become shining beacons for the masses to follow. Leaders of society thus have a moral responsibility to set lofty examples for inspiring the rest of the population by their words, deeds, and character. When noble leaders are in the forefront, the rest of society naturally gets uplifted in morality, selflessness, and spiritual strength. But in times when there is a vacuum of principled leadership, the rest of society has no standards to pursue and slumps into self-centeredness, moral bankruptcy, and spiritual lassitude. Hence, great personalities should always act in an exemplary manner to set the standard for the world. Even though they themselves may have risen to the transcendental platform, and may not need to perform prescribed Vedic duties, by doing so, they inspire others to perform prescribed Vedic actions.

If a great leader of society becomes a karm sanyāsī, and renounces work, it sets an errant precedent for others. The leader may be at the transcendental platform and therefore eligible to renounce work and engage completely in spirituality. However, others in society use their example as an excuse for escapism, to run away from their responsibilities. Such escapists cite the instances of the great karm sanyāsīs, such as Shankaracharya, Madhvacharya, Nimbarkacharya, and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Following their lofty footsteps, these imposters also renounce worldly duties and take sanyās, even though they have not yet attained the purity of mind required for it. In India, we find thousands of such sadhus. They copy the examples of the great sanyāsīs and don the ochre robes, without the concurrent internal enlightenment and bliss. Though externally renounced, their nature forces them to seek happiness, and devoid of the divine bliss of God, they begin indulging in the lowly pleasure of intoxication. Thus, they slip even below the level of people in household life, as stated in the following verse:

brahma jñāna jānyo nahīṅ, karm diye chhiṭakāya,

tulasī aisī ātmā sahaja naraka mahñ jāya.[v15]

Sage Tulsidas says: “One who renounces worldly duties, without the concurrent internal enlightenment with divine knowledge, treads the quick path to hell.”

Instead, if a great leader is a karm yogi, at least the followers will continue to do their karm and dutifully perform their responsibilities. This will help them learn to discipline their mind and senses, and slowly rise to the transcendental platform. Hence, to present an example for society to follow, Shree Krishna suggests that Arjun should practice karm yog. He now gives his own example to illustrate the above point.

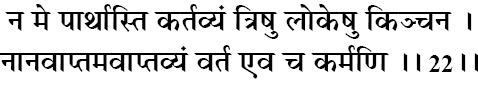

na me pārthāsti kartavyaṁ triṣhu lokeṣhu kiñchana

nānavāptam avāptavyaṁ varta eva cha karmaṇi

na—not; me—mine; pārtha—Arjun; asti—is; kartavyam—duty; triṣhu—in the three; lokeṣhu—worlds; kiñchana—any; na—not; anavāptam—to be attained; avāptavyam—to be gained; varte—I am engaged; eva—yet; cha—also; karmaṇi—in prescribed duties.

There is no duty for me to do in all the three worlds, O Parth, nor do I have anything to gain or attain. Yet, I am engaged in prescribed duties.

The reason why we all work is because we need something. We are all tiny parts of God, who is an ocean of bliss, and hence we all seek bliss. Since, we have not attained perfect bliss as yet, we feel dissatisfied and incomplete. So whatever we do is for the sake of attaining bliss. However, bliss is one of God’s energies and he alone possesses it to the infinite extent. He is perfect and complete in himself and has no need of anything outside of himself. Thus, he is also called Ātmārām (one who rejoices in the self), Ātma-ratī (one who is attracted to his or her own self), and Ātma-krīḍa (one who performs divine pastimes with his or her own self).

If such a personality does work, there can be only one reason for it—it will not be for oneself, rather for the welfare of others. Thus, Shree Krishna tells Arjun that although in his personal form as Shree Krishna, he has no duty to perform in the universe, yet he works for the welfare of others. He next explains the welfare that is accomplished when he works.

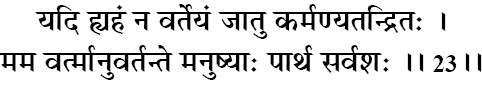

yadi hyahaṁ na varteyaṁ jātu karmaṇyatandritaḥ

mama vartmānuvartante manuṣhyāḥ pārtha sarvaśhaḥ

yadi—if; hi—certainly; aham—I; na—not; varteyam—thus engage; jātu—ever; karmaṇi—in the performance of prescribed duties; atandritaḥ—carefully; mama—my; vartma—path; anuvartante—follow; manuṣhyāḥ—all men; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; sarvaśhaḥ—in all respects.

For if I did not carefully perform the prescribed duties, O Parth, all men would follow my path in all respects.

In his divine pastimes on the Earth, Shree Krishna was playing the role of a king and a great leader. He appeared in the material world as the son of King Vasudeva from the Vrishni dynasty, the foremost of the righteous. If Lord Krishna did not perform prescribed Vedic activities then so many lesser personalities would follow in his footsteps, thinking that violating them was the standard practice. Lord Krishna states that he would be at fault for leading mankind astray.

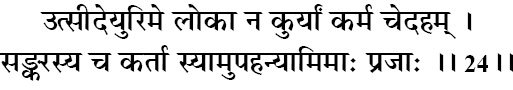

utsīdeyur ime lokā na kuryāṁ karma ched aham

sankarasya cha kartā syām upahanyām imāḥ prajāḥ

utsīdeyuḥ—would perish; ime—all these; lokāḥ—worlds; na—not; kuryām—I perform; karma—prescribed duties; chet—if; aham—I; sankarasya—of uncultured population; cha—and; kartā—responsible; syām—would be; upahanyām—would destroy; imāḥ—all these; prajāḥ—living entities.

If I ceased to perform prescribed actions, all these worlds would perish. I would be responsible for the pandemonium that would prevail, and would thereby destroy the peace of the human race.

When Shree Krishna appeared on the Earth, seemingly as a human being, he conducted himself in all ways and manners, appropriate for his position in society, as a member of the royal warrior class. If he had acted otherwise, other human beings would begin to imitate him, thinking that they must copy the conduct of the worthy son of the righteous King Vasudev. Had Shree Krishna failed to perform Vedic duties, human beings following his example would be led away from the discipline of karm, into a state of chaos. This would have been a very serious offence and Lord Krishna would be considered at fault. Thus, he explains to Arjun that if he did not fulfill his occupational duties, it would cause pandemonium in society.

Similarly, Arjun was world-famous for being undefeated in battle, and was the brother of the virtuous King Yudhisthir. If Arjun refused to fulfill his duty to protect dharma, then many other worthy and noble warriors could follow his example and also renounce their prescribed duty of protecting righteousness. This would bring destruction to the world balance and the rout of innocent and virtuous people. Thus, for the benefit of the entire human race and the welfare of the world, Shree Krishna coaxed Arjun not to neglect performing his prescribed Vedic activities.

saktāḥ karmaṇyavidvānso yathā kurvanti bhārata

kuryād vidvāns tathāsaktaśh chikīrṣhur loka-saṅgraham

saktāḥ—attached; karmaṇi—duties; avidvānsaḥ—the ignorant; yathā—as much as; kurvanti—act; bhārata—scion of Bharat (Arjun); kuryāt—should do; vidvān—the wise; tathā—thus; asaktaḥ—unattached; chikīrṣhuḥ—wishing; loka-saṅgraham—welfare of the world.

As ignorant people perform their duties with attachment to the results, O scion of Bharat, so should the wise act without attachment, for the sake of leading people on the right path.

Previously, in verse 3.20, Shree Krishna had used the expression loka-saṅgraham evāpi sampaśhyan meaning, “with a view to the welfare of the masses.” In this verse, the expression loka-saṅgraham chikīrṣhuḥ means “wishing the welfare of the world.” Thus, Shree Krishna again emphasizes that the wise should always act for the benefit of humankind.

Also, in this verse the expression saktāḥ avidvānsaḥ has been used for people who are as yet in bodily consciousness, and hence attached to worldly pleasures, but who have full faith in the Vedic rituals sanctioned by the scriptures. They are called ignorant because though they have bookish knowledge of the scriptures, they do not comprehend the final goal of God-realization. Such ignorant people perform their duty scrupulously according to the ordinance of the scriptures, without indolence or doubt. They have firm faith that the performance of Vedic duties and rituals will bring the material rewards they desire. If the faith of such people in rituals is broken, without their having developed faith in the higher principle of devotion, they will have nowhere to go. The Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam states:

tāvat karmāṇi kurvīta na nirvidyeta yāvatā

mat-kathā-śhravaṇādau vā śhraddhā yāvan na jāyate (11.20.9) [v16]

“One should continue to perform karm as long as one has not developed renunciation from the sense objects and attachment to God.”

Shree Krishna urges Arjun that just as ignorant people faithfully perform ritualistic duties, so also the wise should perform their works dutifully, not for material rewards, but for setting an ideal for the rest of society. Besides, the particular situation in which Arjun finds himself is a dharma yuddha (war of righteousness). Thus, for the welfare of society, Arjun should perform his duty as a warrior.

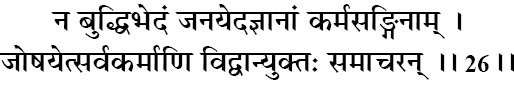

na buddhi-bhedaṁ janayed ajñānāṁ karma-saṅginām

joṣhayet sarva-karmāṇi vidvān yuktaḥ samācharan

na—not; buddhi-bhedam—discord in the intellects; janayet—should create; ajñānām—of the ignorant; karma-saṅginām—who are attached to fruitive actions; joṣhayet—should inspire (them) to perform; sarva—all; karmāṇi—prescribed; vidvān—the wise; yuktaḥ—enlightened; samācharan—performing properly.

The wise should not create discord in the intellects of ignorant people, who are attached to fruitive actions, by inducing them to stop work. Rather, by performing their duties in an enlightened manner, they should inspire the ignorant also to do their prescribed duties.

Great persons have greater responsibility because common people follow them. So Shree Krishna urges that wise people should not perform any actions or make any utterances that lead the ignorant toward downfall. It may be argued that if the wise feel compassion for the ignorant, they should give them the highest knowledge—the knowledge of God-realization. Lord Krishna neutralizes this argument by stating na vichālayet, meaning the ignorant should not be asked to abandon duties by giving superior instructions they are not qualified to understand.

Usually, people in material consciousness consider only two options. Either they are willing to work hard for fruitive results or they wish to give up all exertions on the plea that all works are laborious, painful, and wrought with evil. Between these, working for results is far superior to the escapist approach. Hence, the spiritually wise in Vedic knowledge should inspire the ignorant to perform their duties with attentiveness and care. If the minds of the ignorant become disturbed and unsettled then they may lose faith in working altogether, and with actions stopped and knowledge not arising, the ignorant will lose out from both sides.

If both the ignorant and the wise perform Vedic actions, then what is the difference between them? Apprehending such a question, Shree Krishna explains this in the next two verses.

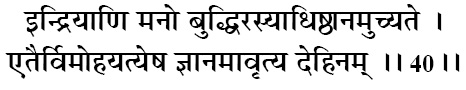

prakṛiteḥ kriyamāṇāni guṇaiḥ karmāṇi sarvaśhaḥ

ahankāra-vimūḍhātmā kartāham iti manyate

prakṛiteḥ—of material nature; kriyamāṇāni—carried out; guṇaiḥ—by the three modes; karmāṇi—activities; sarvaśhaḥ—all kinds of; ahankāra-vimūḍha-ātmā—those who are bewildered by the ego and misidentify themselves with the body; kartā—the doer; aham—I; iti—thus; manyate—thinks.

All activities are carried out by the three modes of material nature. But in ignorance, the soul, deluded by false identification with the body, thinks itself to be the doer.

We can see that the natural phenomena of the world are not directed by us, but are performed by prakṛiti, or Mother Nature. Now, for the actions of our own body, we usually divide them into two categories: 1) Natural biological functions, such as digestion, blood circulation, heartbeat, etc., which we do not consciously execute but which occur naturally. 2) Actions such as speaking, hearing, walking, sleeping, working etc. that we think we perform.

Both these categories of works are performed by the mind-body-senses mechanism. All the parts of this mechanism are made from prakṛiti, or the material energy, which consists of the three modes (guṇas)—goodness (sattva), passion (rajas), and ignorance (tamas). Just as waves are not separate from the ocean, but a part of it, similarly the body is a part of Mother Nature from which it is created. Hence, material energy is the doer of everything.

Why then does the soul perceive itself to be doing activities? The reason is that, in the grip of the unforgiving ego, the soul falsely identifies itself with the body. Hence, it remains under the illusion of doership. Let us say there are two trains standing side-by-side on the railway platform, and a passenger on one train fixes his gaze on the other. When the second train moves, it seems that the first is moving. Likewise the immobile soul identifies with the mobility of prakṛiti. Thus, it perceives itself as the doer of actions. The moment the soul eliminates the ego and surrenders to the will of God, it realizes itself as the non-doer.

One may question that if the soul is truly the non-doer, then why is it implicated in law of karma for actions performed by the body? The reason is that the soul does not itself perform actions, but it does direct the actions of the senses-mind-intellect. For example, a chariot driver does not pull the chariot himself, but he does direct the horses. Now, if there is any accident, it is not the horses that are blamed, but the driver who was directing them. Similarly, the soul is held responsible for the actions of the mind-body mechanism because the senses-mind-intellect work on receiving inspiration from the soul.

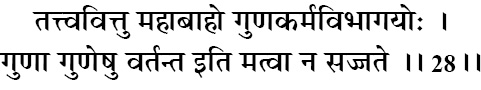

tattva-vit tu mahā-bāho guṇa-karma-vibhāgayoḥ

guṇā guṇeṣhu vartanta iti matvā na sajjate

tattva-vit—the knower of the Truth; tu—but; mahā-bāho—mighty-armed one; guṇa-karma—from guṇas and karma; vibhāgayoḥ—distinguish; guṇāḥ—modes of material nature in the shape of the senses, mind, etc.; guṇeṣhu—modes of material nature in the shape of objects of perception; vartante—are engaged; iti—thus; matvā—knowing; na—never; sajjate—becomes attached.

O mighty-armed Arjun, illumined persons distinguish the soul as distinct from guṇas and karmas. They perceive that it is only the guṇas (in the shape of the senses, mind, etc.) that move amongst the guṇas (in the shape of the objects of perception), and thus they do not get entangled in them.

The previous verse mentioned that the ahankāra vimūḍhātmā (those who are bewildered by the ego and misidentify themselves with the body) think themselves to be the doers. This verse talks about the tattva-vit, or the knowers of the Truth. Having thus abolished the ego, they are free from bodily identifications, and are able to discern their spiritual identity distinct from the corporeal body. Hence, they are not beguiled into thinking of themselves as the doers of their material actions, and instead they attribute every activity to the movements of the three guṇas. Such God-realized Saints say: jo karai so hari karai, hota kabīr kabīr [v17] “God is doing everything, but people are thinking that I am doing.”

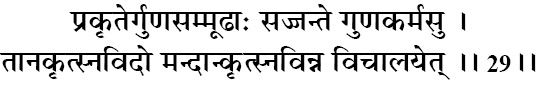

prakṛiter guṇa-sammūḍhāḥ sajjante guṇa-karmasu

tān akṛitsna-vido mandān kṛitsna-vin na vichālayet

prakṛiteḥ—of material nature; guṇa—by the modes of material nature; sammūḍhāḥ—deluded; sajjante—become attached; guṇa-karmasu—to results of actions; tān—those; akṛitsna-vidaḥ—persons without knowledge; mandān—the ignorant; kṛitsna-vit—persons with knowledge; na vichālayet—should not unsettle.

Those who are deluded by the operation of the guṇas become attached to the results of their actions. But the wise who understand these truths should not unsettle such ignorant people who know very little.

The question may be raised that if soul is distinct from the guṇas and their activities, then why are the ignorant attached to sense objects? Shree Krishna explains in this verse that they become bewildered by the guṇas of the material energy, and think themselves to be the doers. Infatuated by the three modes of material nature, they work for the express purpose of being able to enjoy sensual and mental delights. They are unable to perform actions as a matter of duty, without desiring rewards.

However, the kṛitsna-vit (persons with knowledge) should not disturb the minds of the akṛitsna-vit (persons without knowledge). This means that the wise should not force their thoughts onto ignorant persons by saying, “You are the soul, not the body, and hence karm is meaningless; give it up.” Rather, they should instruct the ignorant to perform their respective karm, and slowly help them rise above attachment. In this way, after presenting the distinctions between those who are spiritually wise and those who are ignorant, Shree Krishna gives the sober caution not to unsettle the minds of the ignorant.

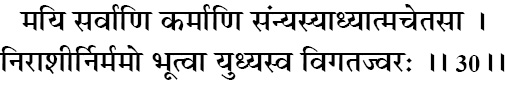

mayi sarvāṇi karmāṇi sannyasyādhyātma-chetasā

nirāśhīr nirmamo bhūtvā yudhyasva vigata-jvaraḥ

mayi—unto me; sarvāṇi—all; karmāṇi—works; sannyasya—renouncing completely; adhyātma-chetasā—with the thoughts resting on God; nirāśhīḥ—free fom hankering for the results of the actions; nirmamaḥ—without ownership; bhūtvā—so being; yudhyasva—fight; vigata-jvaraḥ—without mental fever.

Performing all works as an offering unto me, constantly meditate on me as the Supreme. Become free from desire and selfishness, and with your mental grief departed, fight!

In his typical style, Shree Krishna expounds on a topic and then finally presents the summary. The words adhyātma chetasā mean “with the thoughts resting on God.” Sanyasya means “renouncing all activities that are not dedicated to him.” Nirāśhīḥ means “without hankering for the results of the actions.” The consciousness of dedicating all actions to God requires forsaking claim to proprietorship, and renouncing all desire for personal gain, hankering, and lamentation.

The summary of the instructions in the previous verses is that one should very faithfully reflect, “My soul is a tiny part of the Supreme Lord Shree Krishna. He is the Enjoyer and Master of all. All my works are meant for his pleasure, and thus, I should perform my duties in the spirit of yajña or sacrifice to him. He supplies the energy by which I accomplish works of yajña. Thus, I should not take credit for any actions authored by me.”

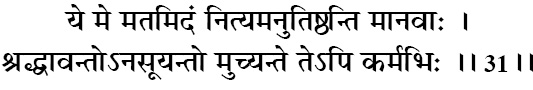

ye me matam idaṁ nityam anutiṣhṭhanti mānavāḥ

śhraddhāvanto ’nasūyanto muchyante te ’pi karmabhiḥ

ye—who; me—my; matam—teachings; idam—these; nityam—constantly; anutiṣhṭhanti—abide by; mānavāḥ—human beings; śhraddhā-vantaḥ—with profound faith; anasūyantaḥ—free from cavilling; muchyante—become free; te—those; api—also; karmabhiḥ—from the bondage of karma.

Those who abide by these teachings of mine, with profound faith and free from cavil, are released from the bondage of karma.

Very beautifully, the Supreme Lord terms the siddhānt (principle) explained by him as mata (opinion). An opinion is a personal view, while a principle is universal fact. Opinions can differ amongst teachers, but the principle is the same. Philosophers and teachers name their opinion as principle, but in the Gita, the Lord has named the principle explained by him as opinion. By his example, he is teaching us humility and cordiality.

Having given the call for action, Shree Krishna now points out the virtues of accepting the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita with faith and following them in one’s life. Our prerogative as humans is to know the truth and then modify our lives accordingly. In this way, our mental fever (of lust, anger, greed, envy, illusion, etc.) gets pacified.

In the previous verse, Shree Krishna had clearly explained to Arjun to offer all works to him. But he knows that this statement can cause ridicule from those who have no belief in God and rebuke from those who are envious of him. So, he now emphasizes the need for accepting the teachings with conviction. He says that by faithfully following these teachings one becomes free from the bondage of karma. But what happens to those who are faithless? Their position is explained next.

ye tvetad abhyasūyanto nānutiṣhṭhanti me matam

sarva-jñāna-vimūḍhāns tān viddhi naṣhṭān achetasaḥ

ye—those; tu—but; etat—this; abhyasūyantaḥ—cavilling; na—not; anutiṣhṭhanti—follow; me—my; matam—teachings; sarva-jñāna—in all types of knowledge; vimūḍhān—deluded; tān—they are; viddhi—know; naṣhṭān—ruined; achetasaḥ—devoid of discrimination.

But those who find faults with my teachings, being bereft of knowledge and devoid of discrimination, they disregard these principles and bring about their own ruin.

The teachings presented by Shree Krishna are perfect for our eternal welfare. However, our material intellect has innumerable imperfections, and so we are not always able to comprehend the sublimity of his teachings or appreciate their benefits. If we could, what would be the difference between us tiny souls and the Supreme Divine Personality? Thus, faith becomes a necessary ingredient for accepting the divine teachings of the Bhagavad Gita. Wherever our intellect is unable to comprehend, rather than finding fault with the teachings, we must submit our intellect, “Shree Krishna has said it. There must be veracity in it, which I cannot understand at present. Let me accept it for now and engage in spiritual sādhanā. I will be able to comprehend it in future, when I progress in spirituality through sādhanā.” This attitude is called śhraddhā, or faith.

Jagadguru Shankaracharaya defines śhraddhā as: guru vedānta vākyeṣhu dṛiḍho viśhvāsaḥ śhraddhā [v18] “Śhraddhā is strong faith in the words of the Guru and the scriptures.” Chaitanya Mahaprabhu explained it similarly: śhraddhā śhabde viśwāsa kahe sudṛiḍha niśhchaya (Chaitanya Charitāmṛit, Madhya Leela, 2.62) [v19] “The word Śhraddhā means strong faith in God and Guru, even though we may not comprehend their message at present.” The British poet, Alfred Tennyson said: “By faith alone, embrace believing, where we cannot prove.” So, śhraddhā means earnestly digesting the comprehensible portions of the Bhagavad Gita, and also accepting the abstruse portions, with the hope that they will become comprehensible in future.

However, one of the persistent defects of the material intellect is pride. Due to pride, whatever the intellect cannot comprehend at present, it often rejects as incorrect. Though Shree Krishna’s teachings are presented by the omniscient Lord for the welfare of the souls, people still find fault in them, such as, “Why is God asking everything to be offered to him? Is he greedy? Is he an egotist that he asks Arjun to worship him?” Shree Krishna says that such people are achetasaḥ, or “devoid of discrimination,” because they cannot distinguish between the pure and the impure, the righteous and the unrighteous, the Creator and the created, the Supreme Master and the servant. Such people “bring about their own ruin,” because they reject the path to eternal salvation and keep rotating in the cycle of life and death.

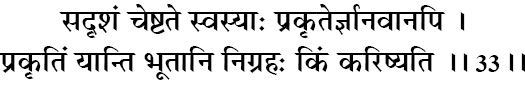

sadṛiśhaṁ cheṣhṭate svasyāḥ prakṛiter jñānavān api

prakṛitiṁ yānti bhūtāni nigrahaḥ kiṁ kariṣhyati

sadṛiśham—accordingly; cheṣhṭate—act; svasyāḥ—by their own; prakṛiteḥ—modes of nature; jñāna-vān—the wise; api—even; prakṛitim—nature; yānti—follow; bhūtāni—all living beings; nigrahaḥ—repression; kim—what; kariṣhyati—will do.

Even wise people act according to their natures, for all living beings are propelled by their natural tendencies. What will one gain by repression?

Shree Krishna again comes back to the point about action being superior to inaction. Propelled by their natures, people are inclined to act in accordance with their individual modes. Even those who are theoretically learned carry with them the baggage of the sanskārs (tendencies and impressions) of endless past lives, the prārabdh karma of this life, and the individual traits of their minds and intellects. They find it difficult to resist this force of habit and nature. If the Vedic scriptures instructed them to give up all works and engage in pure spirituality, it would create an unstable situation. Such artificial repression would be counter-productive. The proper and easier way for spiritual advancement is to utilize the immense force of habit and tendencies and dovetail it in the direction of God. We have to begin the spiritual ascent from where we stand, and doing so requires we have to first accept our present condition of what we are and then improve on it.

We can see how even animals act according to their unique natures. Ants are such social creatures that they bring food for the community while forsaking it themselves, a quality that is difficult to find in human society. A cow has such intense attachment for its calf that the moment it goes out of its sight, the cow feels disturbed. Dogs display the virtue of loyalty to depths that cannot be matched by the best of humans. Similarly, we humans too are propelled by our natures. Since Arjun was a warrior by nature, Shree Krishna told him, “Your own Kṣhatriya (warrior) nature will compel you to fight.” (Bhagavad Gita 18.59) “You will be driven to do it by your own inclination, born of your nature.” (Bhagavad Gita 18.60) That nature should be sublimated by shifting the goal from worldly enjoyment to God-realization, and performing our prescribed duty without attachment and aversion, in the spirit of service to God.

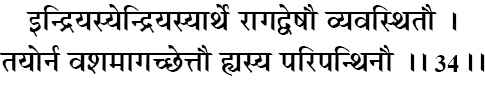

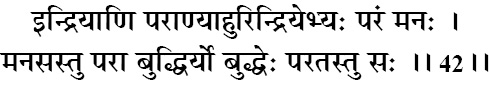

indriyasyendriyasyārthe rāga-dveṣhau vyavasthitau

tayor na vaśham āgachchhet tau hyasya paripanthinau

indriyasya—of the senses; indriyasya arthe—in the sense objects; rāga—attachment; dveṣhau—aversion; vyavasthitau—situated; tayoḥ—of them; na—never; vaśham—be controlled; āgachchhet—should become; tau—those; hi—certainly; asya—for him; paripanthinau—foes.

The senses naturally experience attachment and aversion to the sense objects, but do not be controlled by them, for they are way-layers and foes.

Although Shree Krishna previously emphasized that the mind and senses are propelled by their natural tendencies, he now opens up the possibility of harnessing them. As long as we have the material body, for its maintenance, we have to utilize the objects of the senses. Shree Krishna is not asking us to stop consuming what is necessary, but to practice eradicating attachment and aversion. Definitely sanskārs (past life tendencies) do have a deep-rooted influence on all living beings, but if we practice the method taught in the Bhagavad Gita, we can succeed in correcting the situation.

The senses naturally run toward the sense objects and their mutual interaction creates sensations of pleasure and pain. For example, the taste buds experience joy in contact with delicious foods and distress in contact with bitter foods. The mind repeatedly contemplates the sensations of pleasure and pain which it associates with these objects. Thoughts of pleasure in the sense objects create attachment while thoughts of pain create aversion. Shree Krishna tells Arjun to succumb neither to feelings of attachment nor aversion.

In the discharge of our worldly duty, we will have to encounter all kinds of likeable and unlikeable situations. We must practice neither to yearn for the likeable situations, nor to avoid the unlikeable situations. When we stop being slaves of both the likes and dislikes of the mind and senses, we will overcome our lower nature. And when we become indifferent to both pleasure and pain in the discharge of our duty, we will become truly free to act from our higher nature.

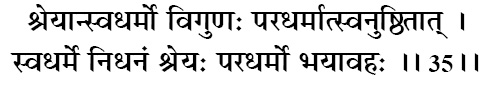

śhreyān swa-dharmo viguṇaḥ para-dharmāt sv-anuṣhṭhitāt

swa-dharme nidhanaṁ śhreyaḥ para-dharmo bhayāvahaḥ

śhreyān—better; swa-dharmaḥ—personal duty; viguṇaḥ—tinged with faults; para-dharmāt—than another’s prescribed duties; su-anuṣhṭhitāt—perfectly done; swa-dharme—in one’s personal duties; nidhanam—death; śhreyaḥ—better; para-dharmaḥ—duties prescribed for others; bhaya-āvahaḥ—fraught with fear.

It is far better to perform one’s natural prescribed duty, though tinged with faults, than to perform another’s prescribed duty, though perfectly. In fact, it is preferable to die in the discharge of one’s duty, than to follow the path of another, which is fraught with danger.

In this verse, the word dharma has been used four times. Dharma is a word commonly used in Hinduism and Buddhism. But it is the most elusive word to translate into the English language. Terms like righteousness, good conduct, duty, noble quality, etc. only describe an aspect of its meaning. Dharma comes from the root word dhṛi, which means ḍhāraṇ karane yogya, or “responsibilities, duties, thoughts, and actions that are appropriate for us.” For example, the dharma of the soul is to love God. It is like the central law of our being.

The suffix swa means “the self.” Thus, swa-dharma is our personal dharma, which is the dharma applicable to our context, situation, maturity, and profession in life. This swa-dharma can change as our context in life changes, and as we grow spiritually. By asking Arjun to follow his swa-dharma, Shree Krishna is telling him to follow his profession, and not change it because someone else may be doing something else.

It is more enjoyable to be ourselves than to pretend to be someone else. The duties born of our nature can be easily performed with stability of mind. The duties of others may seem attractive from a distance and we may think of switching, but that is a risky thing to do. If they conflict with our nature, they will create disharmony in our senses, mind, and intellect. This will be detrimental for our consciousness and will hinder our progress on the spiritual path. Shree Krishna emphasizes this point dramatically by saying that it is better to die in the faithful performance of one’s duty than to be in the unnatural position of doing another’s duty.

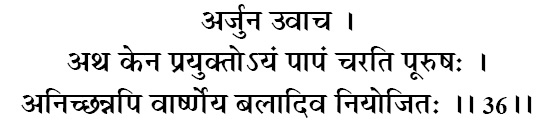

arjuna uvācha

atha kena prayukto ’yaṁ pāpaṁ charati pūruṣhaḥ

anichchhann api vārṣhṇeya balād iva niyojitaḥ

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; atha—then; kena—by what; prayuktaḥ—impelled; ayam—one; pāpam—sins; charati—commit; pūruṣhaḥ—a person; anichchhan—unwillingly; api—even; vārṣhṇeya—he who belongs to the Vrishni clan, Shree Krishna; balāt—by force; iva—as if; niyojitaḥ—engaged.

Arjun asked: Why is a person impelled to commit sinful acts, even unwillingly, as if by force, O descendent of Vrishni (Krishna)?