Jñāna Karm Sanyās Yog

The Yog of Knowledge and the Disciplines of Action

In Chapter four, Shree Krishna strengthens Arjun’s faith in the knowledge he is imparting to him by revealing its pristine origin. He explains how this is an eternal science that he taught in the beginning to the Sun God, and it was passed on in a continuous tradition to saintly kings. He is now revealing the same supreme science of Yog to Arjun, who is a dear friend and devotee. Arjun asks how Shree Krishna, who exists in the present, could have taught this science eons ago to the Sun God. In response, Shree Krishna discloses the divine mystery of his descension. He explains that though God is unborn and eternal, yet by his Yogmaya power, he descends on the earth to establish dharma (the path of righteousness). However, his birth and activities are both divine, and never tainted by material imperfections. Those who know this secret engage in his devotion with great faith, and on attaining him, do not take birth in this world again.

The chapter then explains the nature of work, and discusses three principles—action, inaction, and forbidden action. It discloses how karm yogis are in the state of inaction even while performing the most engaging works, and thus, they are not entangled in karmic reactions. With this wisdom, the ancient sages performed their works, without being affected by success and failure, happiness and distress, merely as an act of sacrifice for the pleasure of God. Sacrifice is of various kinds, and many of them are mentioned here. When sacrifice is properly dedicated, its remnants become like nectar. By partaking of such nectar, performers are cleansed of impurities. Hence, sacrifice must always be performed with proper sentiments and knowledge. With the help of the boat of knowledge, even the biggest sinners can cross over the ocean of material miseries. Such knowledge must be learnt from a genuine spiritual master who has realized the Truth. Shree Krishna, as Arjun’s Guru, asks him to pick up the sword of knowledge, and cutting asunder the doubts that have arisen in his heart, stand up and perform his duty.

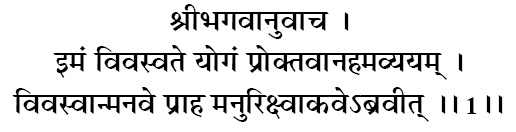

śhrī bhagavān uvācha

imaṁ vivasvate yogaṁ proktavān aham avyayam

vivasvān manave prāha manur ikṣhvākave ’bravīt

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Supreme Lord Shree Krishna said; imam—this; vivasvate—to the Sun-god; yogam—the science of Yog; proktavān—taught; aham—I; avyayam—eternal; vivasvān—Sun-god; manave—to Manu, the original progenitor of humankind; prāha—told; manuḥ—Manu; ikṣhvākave—to Ikshvaku, first king of the Solar dynasty; abravīt—instructed.

The Supreme Lord Shree Krishna said: I taught this eternal science of Yog to the Sun-god, Vivasvan, who passed it on to Manu; and Manu in turn instructed it to Ikshvaku.

Merely imparting invaluable knowledge to someone is not enough. The recipients of that knowledge must appreciate its value and have faith in its authenticity. Only then will they put in the effort required to implement it practically in their lives. In this verse, Shree Krishna establishes the credibility and importance of the spiritual wisdom he is bestowing on Arjun. Shree Krishna informs Arjun that the knowledge being imparted unto him is not newly created for the convenience of motivating him into battle. It is the same eternal science of Yog that he originally taught to Vivasvan, or Surya, Sun God, who imparted it to Manu, the original progenitor of humankind; Manu in turn taught it to Ikshvaku, first king of the Solar dynasty. This is the descending process of knowledge, where someone who is a perfect authority on the knowledge passes it down to another who wishes to know.

In contrast to this is the ascending process of acquiring knowledge, where one endeavors to enhance the frontiers of understanding through self-effort. The ascending process is laborious, imperfect, and time-consuming. For example, if we wish to learn Physics, we could either try to do it by the ascending process, where we speculate about its principles with our own intellect and then reach conclusions, or we could do it by the descending process, where we approach a good teacher of the subject. The ascending process is exceedingly time-consuming, and we may not even be able to complete the inquiry in our lifetime. We can also not be sure about the validity of our conclusions. In comparison, the descending process gives us instant access to the deepest secrets of Physics. If our teacher has perfect knowledge of Physics, then it is very straightforward—simply listen to the science from him and digest what he says. This descending process of receiving knowledge is both easy and faultless.

Every year, thousands of self-help books are released in the market, which present the authors’ solutions to the problems encountered in life. These books may be helpful in a limited way, but because they are based upon the ascending process of attaining knowledge, they are imperfect. Every few years, a new theory comes along that overthrows the current ones. This ascending process is unsuitable for knowing the Absolute Truth. Divine knowledge does not need to be created by self-effort. It is the energy of God, and has existed ever since he has existed, just as heat and light are as old as the fire from which they emanate.

God and the individual soul are both eternal, and so the science of Yog that unites the soul and God is also eternal. There is no need to speculate and formulate new theories about it. An amazing endorsement of this truism is the Bhagavad Gita itself, which continues to astound people with the sagacity of its perennial wisdom that remains relevant to our daily lives even fifty centuries after it was spoken. Shree Krishna states here that the knowledge of Yog, which he is revealing to Arjun, is eternal and it was passed down in ancient times through the descending process, from Guru to disciple.

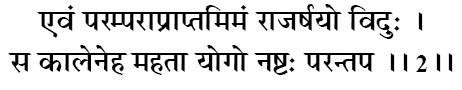

evaṁ paramparā-prāptam imaṁ rājarṣhayo viduḥ

sa kāleneha mahatā yogo naṣhṭaḥ parantapa

evam—thus; paramparā—in a continuous tradition; prāptam—received; imam—this (science); rāja-ṛiṣhayaḥ—the saintly kings; viduḥ—understood; saḥ—that; kālena—with the long passage of time; iha—in this world; mahatā—great; yogaḥ—the science of Yog; naṣhṭaḥ—lost; parantapa—Arjun, the scorcher of foes.

O subduer of enemies, the saintly kings thus received this science of Yog in a continuous tradition. But with the long passage of time, it was lost to the world.

In the descending process of receiving divine knowledge, the disciple understands the science of God-realization from the Guru, who in turn received it from his Guru. It was in such a tradition that saintly kings like Nimi and Janak understood the science of Yog. This tradition starts from God himself, who is the first Guru of the world.

tene brahma hṛidā ya ādi-kavaye muhyanti yat sūrayaḥ (Bhāgavatam 1.1.1)[v1]

God revealed this knowledge at the beginning of creation in the heart of the first-born Brahma, and the tradition continued from him. Shree Krishna stated in the last verse that he also revealed this knowledge to the Sun-god, Vivasvan, from whom the tradition continued as well. However, the nature of this material world is such, that with the passage of time, this knowledge got lost. Materially-minded and insincere disciples interpret the teachings according to their blemished perspectives. Within a few generations, its pristine purity is contaminated. When this happens, by his causeless grace, God reestablishes the tradition for the benefit of humankind. He may do so, either by himself descending in the world, or through a great God-realized Saint, who becomes a conduit for God’s work on Earth.

Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj, who is the fifth original Jagadguru in Indian history, is such a God-inspired Saint who has reestablished the ancient knowledge in modern times. When he was only thirty-four years old, the Kashi Vidvat Parishat, the supreme body of 500 Vedic scholars in the holy city of Kashi, honored him with the title of Jagadguru, or “Spiritual Master of the world.” He became the fifth Saint in Indian history to receive the original title of Jagadguru, after Jagadguru Shankaracharya, Jagadguru Nimbarkacharya, Jagadguru Ramanujacharya, and Jagadguru Madhvacharya. This commentary on the Bhagavad Gita has been written based upon its insightful understanding, as revealed to me by Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj.

sa evāyaṁ mayā te ’dya yogaḥ proktaḥ purātanaḥ

bhakto ’si me sakhā cheti rahasyaṁ hyetad uttamam

saḥ—that; eva—certainly; ayam—this; mayā—by me; te—unto you; adya—today; yogaḥ—the science of Yog; proktaḥ—reveal; purātanaḥ—ancient; bhaktaḥ—devotee; asi—you are; me—my; sakhā—friend; cha—and; iti—therefore; rahasyam—secret; hi—certainly; etat—this; uttamam—supreme.

The same ancient knowledge of Yog, which is the supreme secret, I am today revealing unto you, because you are my friend as well as my devotee, who can understand this transcendental wisdom.

Shree Krishna tells Arjun that the ancient science being imparted to him is an uncommonly known secret. Secrecy in the world is maintained for two reasons: either due to selfishness in keeping the truth to oneself, or to protect the abuse of knowledge. The science of Yog remains a secret, not for either of these reasons, but because it requires a qualification to be understood. That qualification is revealed in this verse as devotion. The deep message of the Bhagavad Gita is not amenable to being understood merely through scholasticism or mastery of the Sanskrit language. It requires devotion, which destroys the subtle envy of the soul toward God and enables us to accept the humble position as his tiny parts and servitors.

Arjun was a fit student of this science because he was a devotee of the Lord. Devotion to God can be practiced in any of the five sequentially higher bhāvas, or sentiments: 1) Śhānt bhāv: adoring God as our King. 2) Dāsya bhav: the sentiment of servitude toward God as our Master. 3) Sakhya bhāv: considering God as our Friend. 4) Vātsalya bhāv: considering God as our Child. 5) Mādhurya bhāv: worshipping God as our Soul-beloved. Arjun worshipped God as his Friend, and so Shree Krishna speaks to him as his friend and devotee.

Without a devotional heart, one cannot truly grasp the message of the Bhagavad Gita. This verse also invalidates the commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita written by scholars, jñānīs, yogis, tapasvīs, etc., who lack bhakti (devotion) toward God. According to this verse, since they are not devotees, they cannot comprehend the true import of the supreme science that was revealed to Arjun, and hence their commentaries are inaccurate and/or incomplete.

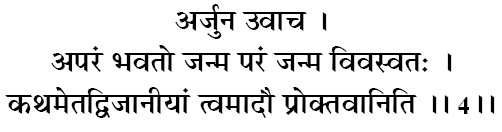

arjuna uvācha

aparaṁ bhavato janma paraṁ janma vivasvataḥ

katham etad vijānīyāṁ tvam ādau proktavān iti

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; aparam—later; bhavataḥ—your; janma—birth; param—prior; janma—birth; vivasvataḥ—Vivasvan, the sun-god; katham—how; etat—this; vijānīyām—am I to understand; tvam—you; ādau—in the beginning; proktavān—taught; iti—thus.

Arjun said: You were born much after Vivasvan. How am I to understand that in the beginning you instructed this science to him?

Arjun is puzzled by the apparent incongruity of events in Shree Krishna’s statement. The Sun god has been present since almost the beginning of creation, while Shree Krishna has only recently been born in the world. If Shree Krishna is the son of Vasudev and Devaki, then his statement that he taught this science to Vivasvan, the Sun god appears inconsistent to Arjun, and he inquires about it. Arjun’s question invites an exposition on the concept of the divine descension of God, and Shree Krishna responds to it in the subsequent verses.

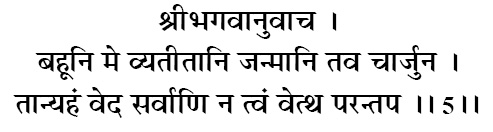

śhrī bhagavān uvācha

bahūni me vyatītāni janmāni tava chārjuna

tānyahaṁ veda sarvāṇi na tvaṁ vettha parantapa

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Supreme Lord said; bahūni—many; me—of mine; vyatītāni—have passed; janmāni—births; tava—of yours; cha—and; arjuna—Arjun; tāni—them; aham—I; veda—know; sarvāṇi—all; na—not; tvam—you; vettha—know; parantapa—Arjun, the scorcher of foes.

The Supreme Lord said: Both you and I have had many births, O Arjun. You have forgotten them, while I remember them all, O Parantapa.

Shree Krishna explains that merely because he is standing before Arjun in the human form, he should not be equated with human beings. The president of a country sometimes decides to visit the prison, but if we see the president standing in the jail, we do not erroneously conclude that he is also a convict. We know that he is in the jail merely for an inspection. Similarly, God sometimes descends in the material world, but he is never divested of his divine attributes and powers.

In his commentary upon this verse, Shankaracharya states: yā vāsudeve anīśhvarāsarvajñāśhaṅkā mūrkhāṇāṃ tāṃ pariharan śhrī-bhagavān uvācha (Śhārīrak Bhāṣhya on verse 4.5) [v2] “This verse has been spoken by Shree Krishna to refute foolish people who doubt that he is not God.” Non-believers argue that Shree Krishna too was born like the rest of us, and he ate, drank, slept, like we all do, and so he could not have been God. Here, Shree Krishna emphasizes the difference between the soul and God by stating that although he descends in the world innumerable times, he still remains omniscient, unlike the soul whose knowledge is finite.

The individual soul and the Supreme Soul, God, have many similarities—both are sat-chit-ānand (eternal, sentient, and blissful). However, there are also many differences. God is all-pervading, while the soul only pervades the body it inhabits; God is all-powerful, while the soul does not even have the power to liberate itself from Maya without God’s grace; God is the creator of the laws of nature, while the soul is subject to these laws; God is the upholder of the entire creation, while the soul is upheld by him; God is all-knowing, while the soul does not have complete knowledge even in one subject.

Shree Krishna calls Arjun in this verse as “Parantapa,” meaning “subduer of the enemies.” He implies, “Arjun, you are a valiant warrior who has slayed so many powerful enemies. Now, do not accept defeat before this doubt that has crept into your mind. Use the sword of knowledge that I am giving you to slay it and be situated in wisdom.”

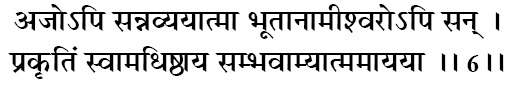

ajo ’pi sannavyayātmā bhūtānām īśhvaro ’pi san

prakṛitiṁ svām adhiṣhṭhāya sambhavāmyātma-māyayā

ajaḥ—unborn; api—although; san—being so; avyaya ātmā—Imperishable nature; bhūtānām—of (all) beings; īśhvaraḥ—the Lord; api—although; san—being; prakṛitim—nature; svām—of myself; adhiṣhṭhāya—situated; sambhavāmi—I manifest; ātma-māyayā—by my Yogmaya power.

Although I am unborn, the Lord of all living entities, and have an imperishable nature, yet I appear in this world by virtue of Yogmaya, my divine power.

Many people revolt at the idea of a God who possesses a form. They are more comfortable with a formless God, who is all-pervading, incorporeal, and subtle. God is definitely incorporeal and formless, but that does not mean that he cannot simultaneously have a form as well. Since God is all-powerful, he has the power to manifest in a form if he wishes. If someone stipulates that God cannot have a form, it means that person does not accept him as all-powerful. Thus to say, “God is formless,” is an incomplete statement. On the other hand, to say, “God manifests in a personal form,” is also only a partial truth. The all-powerful God has both aspects to his divine personality—the personal form and the formless aspect. Hence, the Bṛihadāraṇyak Upaniṣhad states:

dwe vāva brahmaṇo rūpe mūrtaṁ chaiva amūrtaṁ cha (2.3.1) [v3]

“God appears in both ways—as the formless Brahman and as the personal God.” They are both dimensions of his personality.

In fact, the individual soul also has these two dimensions to its existence. It is formless, and hence, when it leaves the body upon death, it cannot be seen. Yet it takes on a body—not once, but innumerable times—as it transmigrates from birth to birth. When the tiny soul is able to possess a body, can the all-powerful God not have a form? Or is it that God says, “I do not have the power to manifest in a form, and hence I am only a formless light.” For him to be perfect and complete, he must be both personal and formless.

The difference is that while our form is created from the material energy, Maya, God’s form is created by his divine energy, Yogmaya. It is thus divine, and beyond material defects. This has been nicely stated in the Padma Purāṇ:

yastu nirguṇa ityuktaḥ śhāstreṣhu jagadīśhvaraḥ

prākṛitairheya sanyuktairguṇairhīnatvamuchyate [v4]

“Wherever the Vedic scriptures state that God does not have a form, they imply that his form is not subject to the blemishes of the material energy; rather, it is a divine form.”

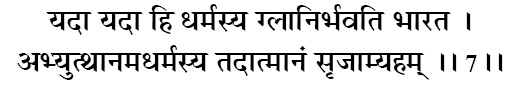

yadā yadā hi dharmasya glānir bhavati bhārata

abhyutthānam adharmasya tadātmānaṁ sṛijāmyaham

yadā yadā—whenever; hi—certainly; dharmasya—of righteousness; glāniḥ—decline; bhavati—is; bhārata—Arjun, descendant of Bharat; abhyutthānam—increase; adharmasya—of unrighteousness; tadā—at that time; ātmānam—self; sṛijāmi—manifest; aham—I.

Whenever there is a decline in righteousness and an increase in unrighteousness, O Arjun, at that time I manifest myself on earth.

Dharma is verily the prescribed actions that are conducive to our spiritual growth and progress; the reverse of this is adharma (unrighteousness). When unrighteousness prevails, the creator and administrator of the world intervenes by descending and reestablishing dharma. Such a descension of God is called an Avatār. The word “Avatar” has been adopted from Sanskrit into English and is commonly used for people’s images on the media screen. In this text, we will be using it in its original Sanskrit connotation, to refer to the divine descension of God. Twenty four such descensions have been listed in the Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam. However, the Vedic scriptures state that there are innumerable descensions of God:

janma-karmābhidhānāni santi me ’ṅga sahasraśhaḥ

na śhakyante ’nusankhyātum anantatvān mayāpi hi (Bhāgavatam 10.51.36) [v5]

“Nobody can count the infinite Avatars of God since the beginning of eternity.” These Avatars are classified in four categories, as stated below:

1. Āveśhāvatār—when God manifests his special powers in an individual soul and acts through him. The sage Narad is an example of Āveśhāvatār. The Buddha is also an example of Āveśhāvatār.

2. Prābhavāvatār—these are the descensions of God in the personal form, where he displays some of his divine powers. Prābhavāvatārs are also of two kinds:

a) Where God reveals himself only for a few moments, completes his work, and then departs. Hansavatar is an example of this, where God manifested before the Kumaras, answered their question, and left.

b) Where the Avatar remains on the earth for many years. Ved Vyas, who wrote the eighteen Puranas and the Mahabharat, and divided the Vedas into four parts, is an example of such an Avatar.

3. Vaibhavatār—when God descends in his divine form, and manifests more of his divine powers. Matsyavatar, Kurmavatar, Varahavatar are all examples of Vaibhavatārs.

4. Paravāsthāvatār—when God manifests all his divine powers in his personal divine form. Shree Krishna, Shree Ram, and Nrisinghavatar are all Parāvasthāvatār.

This classification does not imply that any one Avatār is bigger than the other. Ved Vyas, who is himself an Avatār, clearly states this: sarve pūrṇāḥ śhāśhvatāśhcha dehāstasya paramātmanaḥ (Padma Purāṇ) [v6] “All the descensions of God are replete with all divine powers; they are all perfect and complete.” Hence, we should not differentiate one Avatar as bigger and another as smaller. However, in each descension, God manifests his powers based on the objectives he wishes to accomplish during that particular descension. The remaining powers reside latently within the Avatar. Hence, the above classifications were created.

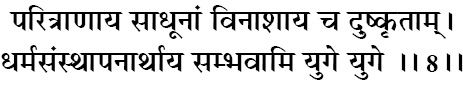

paritrāṇāya sādhūnāṁ vināśhāya cha duṣhkṛitām

dharma-sansthāpanārthāya sambhavāmi yuge yuge

paritrāṇāya—to protect; sādhūnām—the righteous; vināśhāya—to annihilate; cha—and; duṣhkṛitām—the wicked; dharma—the eternal religion; sansthāpana-arthāya—to reestablish; sambhavāmi—I appear; yuge yuge—age after age.

To protect the righteous, to annihilate the wicked, and to reestablish the principles of dharma I appear on this earth, age after age.

Having stated in the last verse that God descends in the world, he now states the three reasons for doing so: 1) To annihilate the wicked. 2) To protect the pious. 3) To establish dharma. However, if we closely study these three points, none of the three reasons seem very convincing:

To protect the righteous. God is seated in the hearts of his devotees, and always protects them from within. There is no need to take an Avatar for this purpose.

To annihilate the wicked. God is all-powerful, and can kill the wicked merely by wishing it. Why should he have to take an Avatar to accomplish this?

To establish dharma. Dharma is eternally described in the Vedas. God can reestablish it through a Saint; he does not need to descend himself, in his personal form, to accomplish this.

How then do we make sense of the reasons that have been stated in this verse? Let’s delve a little deeper to grasp the import of what Shree Krishna is stating.

The biggest dharma that the soul can engage in is devotion to God. That is what God strengthens by taking an Avatār. When God descends in the world, he reveals his divine forms, names, virtues, pastimes, abodes, and associates. This provides the souls with an easy basis for devotion. Since the mind needs a form to focus upon and to connect with, the formless aspect of God is very difficult to worship. On the other hand, devotion to the personal form of God is easy for people to comprehend, simple to perform, and sweet to engage in.

Thus, since the descension of Lord Krishna 5,000 years ago, billions of souls have made his divine leelas (pastimes) as the basis of their devotion, and purified their minds with ease and joy. Similarly, the Ramayan has provided the souls with a popular basis for devotion for innumerable centuries. When the TV show, Ramayan, first began airing on Indian national television on Sunday mornings, all the streets of India would become empty. The pastimes of Lord Ram held such fascination for the people that they would be glued to their television sets to see the leelas on the screen. This reveals how Lord Ram’s descension provided the basis for devotion to billions of souls in history. The Ramayan says:

rām eka tāpasa tiya tārī, nāma koṭi khala kumati sudhārī. [v7]

“In his descension period, Lord Ram helped only one Ahalya (Sage Gautam’s wife, whom Lord Ram released from the body of stone). However, since then, by chanting the divine name “Ram,” billions of fallen souls have elevated themselves.” So a deeper understanding of this verse is:

To establish dharma: God descends to establish the dharma of devotion by providing souls with his names, forms, pastimes, virtues, abodes, and associates, with the help of which they may engage in bhakti and purify their minds.

To kill the wicked: Along with God, to help facilitate his divine pastimes, some liberated Saints descend and pretend to be miscreants. For example, Ravan and Kumbhakarna were Jaya and Vijaya who descended from the divine abode of God. They pretended to be demons and opposed and fought with Ram. They could not have been killed by anyone else, since they were divine personalities. So, God slayed such demons as a part of his leelas. And having killed them, he sent them to his divine abode, since that was where they came from in the first place.

To protect the righteous: Many souls had become sufficiently elevated in their sādhanā (spiritual practice) to qualify to meet God face-to-face. When Shree Krishna descended in the world, these eligible souls got their first opportunity to participate in God’s divine pastimes. For example, some gopīs (cowherd women of Vrindavan, where Shree Krishna manifested his pastimes) were liberated souls who had descended from the divine abode to assist in Shree Krishna’s leelas. Other gopīs were materially bound souls who got their first chance to meet and serve God, and participate in his leelas. So when Shree Krishna descended in the world, such qualified souls got the opportunity to perfect their devotion by directly participating in the pastimes of God.

This is the deeper meaning of the verse. However, it is not wrong if someone wishes to cognize the verse more literally or metaphorically.

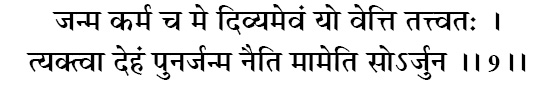

janma karma cha me divyam evaṁ yo vetti tattvataḥ

tyaktvā dehaṁ punar janma naiti mām eti so ’rjuna

janma—birth; karma—activities; cha—and; me—of mine; divyam—divine; evam—thus; yaḥ—who; vetti—know; tattvataḥ—in truth; tyaktvā—having abandoned; deham—the body; punaḥ—again; janma—birth; na—never; eti—takes; mām—to me; eti—comes; saḥ—he; arjuna—Arjun.

Those who understand the divine nature of my birth and activities, O Arjun, upon leaving the body, do not have to take birth again, but come to my eternal abode.

Understand this verse in the light of the previous one. Our mind gets cleansed by engaging it in devotional remembrance of God. This devotion can either be toward the formless aspect of God or toward his personal form. Devotion toward the formless is intangible and nebulous to most people. They find nothing to focus upon or feel connected with during such devotional meditation. Devotion to the personal form of God is tangible and simple. Such devotion requires divine sentiments toward the personality of God. For people to engage in devotion to Shree Krishna, they must develop divine feelings toward his names, form, virtues, pastimes, abode, and associates. For example, people purify their minds by worshipping stone deities because they harbor the divine sentiments that God resides in these deities. It is these sentiments that purify the devotee’s mind. The progenitor Manu says:

na kāṣhṭhe vidyate devo na śhilāyāṁ na mṛitsu cha

bhāve hi vidyate devastasmātbhāvaṁ samācharet [v8]

“God resides neither in wood nor in stone, but in a devotional heart. Hence, worship the deity with loving sentiments.”

Similarly, if we wish to engage in devotion toward Lord Krishna, we must learn to harbor divine sentiments toward his leelas. Those commentators who give a figurative interpretation to the Mahabharat and the Bhagavad Gita, do grave injustice by destroying the basis of people’s faith in devotion toward Shree Krishna. In this verse, Shree Krishna has emphasized the need for divine sentiments toward his pastimes, for enhancing our devotion.

To develop such divine feelings, we must understand the difference between God’s actions and ours. We materially bound souls have not yet attained divine bliss, and hence the longing of our soul is not yet satiated. Thus, our actions are motivated by self-interest and the desire for personal fulfillment. However, God’s actions have no personal motive because he is perfectly satiated by the infinite bliss of his own personality. He does not need to achieve further personal bliss by performing actions. Therefore, whatever he does is for the welfare of the materially conditioned souls. Such divine actions that God performs are termed as “leelas” while the actions we perform are called “work.”

Similarly, God’s birth is also divine, and unlike ours, it does not take place from a mother’s womb. The all-Blissful God has no requirement to hang upside down in a mother’s womb. The Bhāgavatam states:

tam adbhutaṁ bālakam ambujekṣhaṇaṁ

chatur-bhujaṁ śhaṅkha gadādyudāyudham (10.3.9) [v9]

“When Shree Krishna manifested upon birth before Vasudev and Devaki, he was in his four-armed Vishnu form.” This full-sized form could definitely not have resided in Devaki’s womb. However, to create in her the feeling that he was there, by his Yogmaya power, he simply kept expanding Devaki’s womb. Finally, he manifested from the outside, revealing that he had never been inside her:

āvirāsīd yathā prāchyāṁ diśhīndur iva puṣhkalaḥ (Bhāgavatam 10.3.8) [v10]

“As the moon manifests in its full glory in the night sky, similarly the Supreme Lord Shree Krishna manifested before Devaki and Vasudev.” This is the divine nature of God’s birth. If we can develop faith in the divinity of his pastimes and birth, then we will be able to easily engage in devotion to his personal form, and attain the supreme destination.

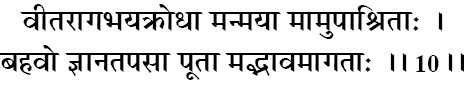

vīta-rāga-bhaya-krodhā man-mayā mām upāśhritāḥ

bahavo jñāna-tapasā pūtā mad-bhāvam āgatāḥ

vīta—freed from; rāga—attachment; bhaya—fear; krodhāḥ—and anger; mat-mayā—completely absorbed in me; mām—in me; upāśhritāḥ—taking refuge (of); bahavaḥ—many (persons); jñāna—of knowledge; tapasā—by the fire of knowledge; pūtāḥ—purified; mat-bhāvam—my divine love; āgatāḥ—attained.

Being freed from attachment, fear, and anger, becoming fully absorbed in me, and taking refuge in me, many persons in the past became purified by knowledge of me, and thus they attained my divine love.

In the previous verse, Lord Krishna explained that those who truly know the divine nature of his birth and pastimes attain him. He now confirms that legions of human beings in all ages became God-realized by this means. They achieved this goal by purifying their minds through devotion. Shree Aurobindo put it very nicely: “You must keep the temple of the heart clean, if you wish to install therein the living presence.” The Bible states: “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.” (Matthew 5.8) [v11]

Now, how does the mind get purified? By giving up attachment, fear, and anger, and absorbing the mind in God. Actually, attachment is the cause of both fear and anger. Fear arises out of apprehension that the object of our attachment will be snatched away from us. And anger arises when there is an obstruction in attaining the object of our attachment. Attachment is thus the root cause of the mind getting dirty.

This world of Maya consists of the three modes of material nature—sattva, rajas, and tamas (goodness, passion, and ignorance). All objects and personalities in the world come within the realm of these three modes. When we attach our mind to a material object or person, our mind too becomes affected by the three modes. Instead, when we absorb the same mind in God, who is beyond the three modes of material nature, such devotion purifies the mind. Thus, the sovereign recipe to cleanse the mind from the defects of lust, anger, greed, envy, and illusion, is to detach it from the world and attach it to the Supreme Lord. Hence, the Ramayan states:

prema bhagati jala binu raghurāī, abhiantara mala kabahuñ jāī [v12]

“Without devotion to God, the dirt of the mind will not be washed away.” Even the ardent propagator of jñāna yog, Shankaracharya, stated:

śhuddhayati hi nāntarātmā kṛiṣhṇapadāmbhoja bhaktimṛite

(Prabodh Sudhākar) [v13]

“Without engaging in devotion to the lotus feet of Lord Krishna, the mind will not be cleansed.”

On reading the previous verse, a question may arise whether Lord Krishna is partial in bestowing his grace upon those who absorb their minds in him versus the worldly-minded souls. The Supreme Lord addresses this in the next verse.

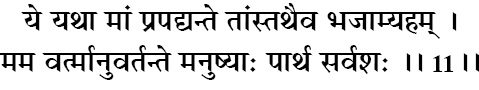

ye yathā māṁ prapadyante tāns tathaiva bhajāmyaham

mama vartmānuvartante manuṣhyāḥ pārtha sarvaśhaḥ

ye—who; yathā—in whatever way; mām—unto me; prapadyante—surrender; tān—them; tathā—so; eva—certainly; bhajāmi—reciprocate; aham—I; mama—my; vartma—path; anuvartante—follow; manuṣhyāḥ—men; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; sarvaśhaḥ—in all respects.

In whatever way people surrender unto me, I reciprocate with them accordingly. Everyone follows my path, knowingly or unknowingly, O son of Pritha.

Here, Lord Krishna states that he reciprocates with everyone as they surrender to him. For those who deny the existence of God, he meets them in the form of the law of karma—he sits inside their hearts, notes their actions, and dispenses the results. But such atheists too cannot get away from serving him; they are obliged to serve God’s material energy, Maya, in its various apparitions, as wealth, luxuries, relatives, prestige, etc. Maya holds them under the sway of anger, lust, and greed. On the other hand, for those who turn their mind away from worldly attractions and look upon God as the goal and refuge, he takes care of them just as a mother takes care of her child.

Shree Krishna uses the word bhajāmi, which means “to serve.” He serves the surrendered souls, by destroying their accumulated karmas of endless lifetimes, cutting the bonds of Maya, removing the darkness of material existence, and bestowing divine bliss, divine knowledge, and divine love. And when the devotee learns to love God selflessly, he willingly enslaves himself to their love. Shree Ram thus tells Hanuman:

ekaikasyopakārasya prāṇān dāsyāsmi te kape

śheṣhasyehopakārāṇāṁ bhavām ṛiṇino vayaṁ

(Vālmīki Ramayan) [v14]

“O Hanuman, to release myself from the debt of one service you performed for me, I shall have to offer my life to you. For all the other devotional services done by you, I shall remain eternally indebted.” In this way, God reciprocates with everyone as they surrender to him.

If God is so merciful upon his devotees, why do some people worship the celestial gods instead? He explains in the following verse.

kāṅkṣhantaḥ karmaṇāṁ siddhiṁ yajanta iha devatāḥ

kṣhipraṁ hi mānuṣhe loke siddhir bhavati karmajā

kāṅkṣhantaḥ—desiring; karmaṇām—material activities; siddhim—success; yajante—worship; iha—in this world; devatāḥ—the celestial gods; kṣhipram—quickly; hi—certainly; mānuṣhe—in human society; loke—within this world; siddhiḥ—rewarding; bhavati—manifest; karma-jā—from material activities.

In this world, those desiring success in material activities worship the celestial gods, since material rewards manifest quickly.

Persons who seek worldly gain worship the celestial gods and seek boons from them. The boons the celestial gods bestow are material and temporary, and they are given only by virtue of the power they have received from the Supreme Lord. There is a beautiful instructive story in this regard:

Saint Farid went to the court of Emperor Akbar, a powerful king in Indian history. He waited in the court for an audience, while Akbar was praying in the next room. Farid peeped into the room to see what was going on, and was amused to hear Akbar praying to God for more powerful army, a bigger treasure chest, and success in battle. Without disturbing the king, Farid returned to the royal court.

After completing his prayers, Akbar came and gave him audience. He asked the great Sage if there was anything that he wanted. Farid replied, “I came to ask the Emperor for things I required for my āśhram. However, I find that the Emperor is himself a beggar before the Lord. Then why should I ask him for any favors, and not directly from the Lord himself?”

The celestial gods give boons only by the powers bestowed upon them by the Supreme Lord. People with small understanding approach them, but those who are intelligent realize that there is no point in going to the intermediary and they approach the Supreme Lord for the fulfillment of their aspirations. People are of various kinds, possessing higher and lower aspirations. Shree Krishna now mentions four categories of qualities and works.

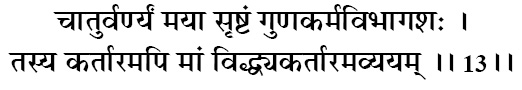

chātur-varṇyaṁ mayā sṛiṣhṭaṁ guṇa-karma-vibhāgaśhaḥ

tasya kartāram api māṁ viddhyakartāram avyayam

chātuḥ-varṇyam—the four categories of occupations; mayā—by me; sṛiṣhṭam—were created; guṇa—of quality; karma—and activities; vibhāgaśhaḥ—according to divisions; tasya—of that; kartāram—the creator; api—although; mām—me; viddhi—know; akartāram—non-doer; avyayam—unchangeable.

The four categories of occupations were created by me according to people’s qualities and activities. Although I am the creator of this system, know me to be the non-doer and eternal.

The Vedas classify people into four categories of occupations, not according to their birth, but according to their natures. Such varieties of occupations exist in every society. Even in communist nations where equality is the overriding principle, the diversity in human beings cannot be smothered. There are the philosophers who are the communist party think-tanks, there are the military men who protect the country, there are the farmers who engage in agriculture, and there are the factory workers.

The Vedic philosophy explains this variety in a more scientific manner. It states that the material energy is constituted of three guṇas (modes): sattva guṇa (mode of goodness), rajo guṇa (mode of passion), and tamo guṇa (mode of ignorance). The Brahmins are those who have a preponderance of the mode of goodness. They are predisposed toward teaching and worship. The Kshatriyas are those who have a preponderance of the mode of passion mixed with a smaller amount of the mode of goodness. They are inclined toward administration and management. The Vaishyas are those who possess the mode of passion mixed with some mode of ignorance. Accordingly, they form the business and agricultural class. Then there are the Shudras, who are predominated by the mode of ignorance. They form the working class. This classification was neither meant to be according to birth, nor was it unchangeable. Shree Krishna explains in this verse that the classification of the Varṇāśhram system was according to people’s qualities and activities.

Although God is the creator of the scheme of the world, yet he is the non-doer. This is similar to the rain. Just as rain water falls equally on the forest, yet from some seeds huge banyan trees sprout, from other seeds beautiful flowers bloom, and from some thorny bushes emerge. The rain, which is impartial, is not answerable for this difference. In the same way, God provides the souls with the energy to act, but they are free in determining what they wish to do with it; God is not responsible for their actions.

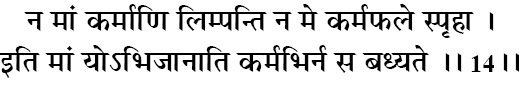

na māṁ karmāṇi limpanti na me karma-phale spṛihā

iti māṁ yo ’bhijānāti karmabhir na sa badhyate

na—not; mām—me; karmāṇi—activities; limpanti—taint; na—nor; me—my; karma-phale—the fruits of action; spṛihā—desire; iti—thus; mām—me; yaḥ—who; abhijānāti—knows; karmabhiḥ—result of action; na—never; saḥ—that person; badhyate—is bound.

Activities do not taint me, nor do I desire the fruits of action. One who knows me in this way is never bound by the karmic reactions of work.

God is all-pure, and whatever he does also becomes pure and auspicious. The Ramayan states:

samaratha kahuñ nahiṅ doṣhu gosāīṅ, rabi pāvaka surasari kī nāīṅ. [v15]

“Pure personalities are never tainted by defects even in contact with impure situations and entities, like the sun, the fire, and the Ganges.” The sun does not get tainted if sunlight falls on a puddle of urine. The sun retains its purity, while also purifying the dirty puddle. Similarly, if we offer impure objects into the fire, it still retains its purity—the fire is pure, and whatever we pour into it also gets purified. In the same manner, numerous gutters of rainwater merge into the holy Ganges, but this does not make the Ganges a gutter—the Ganges is pure and in transforms all those dirty gutters into the holy Ganges. Likewise, God is not tainted by the activities he performs.

Activities bind one in karmic reactions when they are performed with the mentality of enjoying the results. However, God’s actions are not motivated by selfishness; his every act is driven by compassion for the souls. Therefore, although he administers the world directly or indirectly, and engages in all kinds of activities in the process, he is never tainted by any reactions. Lord Krishna states here that he is transcendental to the fruitive reactions of work.

Even Saints who are situated in God-consciousness become transcendental to the material energy. Since all their activities are effectuated in love for God, such pure-hearted Saints are not bound by the fruitive reactions of work. The Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam states:

yat pāda paṅkaja parāga niṣheva tṛiptā

yoga prabhāva vidhutākhila karma bandhāḥ

svairaṁ charanti munayo ’pi na nahyamānās

tasyechchhayātta vapuṣhaḥ kuta eva bandhaḥ (10.33.34) [v16]

“Material activities never taint the devotees of God who are fully satisfied in serving the dust of his lotus feet. Nor do material activities taint those wise sages who have freed themselves from the bondage of fruitive reactions by the power of Yog. So where is the question of bondage for the Lord himself who assumes his transcendental form according to his own sweet will?”

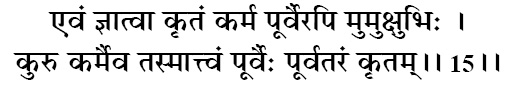

evaṁ jñātvā kṛitaṁ karma pūrvair api mumukṣhubhiḥ

kuru karmaiva tasmāttvaṁ pūrvaiḥ pūrvataraṁ kṛitam

evam—thus; jñātvā—knowing; kṛitam—performed; karma—actions; pūrvaiḥ—of ancient times; api—indeed; mumukṣhubhiḥ—seekers of liberation; kuru—should perform; karma—duty; eva—certainly; tasmāt—therefore; tvam—you; pūrvaiḥ—of those ancient sages; pūrva-taram—in ancient times; kṛitam—performed.

Knowing this truth, even seekers of liberation in ancient times performed actions. Therefore, following the footsteps of those ancient sages, you too should perform your duty.

The sages who aspire for God are not motivated to work for material gain. Why then do they engage in activities in this world? The reason is that they wish to serve God, and are inspired to do works for his pleasure. The knowledge of the previous verse assures them that they themselves will never be bound by welfare work that is done in the spirit of devotion. They are also moved by compassion on seeing the sufferings of the materially bound souls who are bereft of God consciousness, and are inspired to work for their spiritual elevation. The Buddha once said, “After attaining enlightenment, you have two options—either you do nothing, or you help others attain enlightenment.”

Thus, even sages who have no selfish motive for work still engage in activities for the pleasure of God. Working in devotion also attracts the grace of God. Shree Krishna is advising Arjun to do the same. Having asked Arjun to perform actions that do not bind one, the Lord now begins expounding the philosophy of action.

kiṁ karma kim akarmeti kavayo ’pyatra mohitāḥ

tat te karma pravakṣhyāmi yaj jñātvā mokṣhyase ’śhubhāt

kim—what; karma—action; kim—what; akarma—inaction; iti—thus; kavayaḥ—the wise; api—even; atra—in this; mohitāḥ—are confused; tat—that; te—to you; karma—action; pravakṣhyāmi—I shall explain; yat—which; jñātvā—knowing; mokṣhyase—you may free yourself; aśhubhāt—from inauspiciousness.

What is action and what is inaction? Even the wise are confused in determining this. Now I shall explain to you the secret of action, by knowing which, you may free yourself from material bondage.

The principles of dharma cannot be determined by mental speculation. Even intelligent persons become confused in the maze of apparently contradictory arguments presented by the scriptures and the sages. For example, the Vedas recommend non-violence. Accordingly in the Mahabharat, Arjun wishes to follow the same course of action and shun violence but Shree Krishna says that his duty here is to engage in violence. If duty varies with circumstance, then to ascertain one’s duty in any particular situation is a complex matter. Yamraj, the celestial god of Death, stated:

dharmaṁ tu sākṣhād bhagavat praṇītaṁ na vai vidur ṛiṣhayo nāpi devāḥ

(Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam 6.3.19) [v17]

“What is proper action and what is improper action? This is difficult to determine even for the great ṛiṣhis and the celestial gods. Dharma has been created by God himself, and he alone is its true knower.” Lord Krishna says to Arjun that he shall now reveal to him the esoteric science of action and inaction through which he may free himself from material bondage.

karmaṇo hyapi boddhavyaṁ boddhavyaṁ cha vikarmaṇaḥ

akarmaṇaśh cha boddhavyaṁ gahanā karmaṇo gatiḥ

karmaṇaḥ—recommended action; hi—certainly; api—also; boddhavyam—should be known; boddhavyam—must understand; cha—and; vikarmaṇaḥ—forbidden action; akarmaṇaḥ—inaction; cha—and; boddhavyam—must understand; gahanā—profound; karmaṇaḥ—of action; gatiḥ—the true path.

You must understand the nature of all three—recommended action, wrong action, and inaction. The truth about these is profound and difficult to understand.

Work has been divided by Shree Krishna into three categories—action (karm), forbidden action (vikarm), and inaction (akarm).

Action. Karm is auspicious actions recommended by the scriptures for regulating the senses and purifying the mind.

Forbidden action. Vikarm is inauspicious actions prohibited by the scriptures since they are detrimental and result in degradation of the soul.

Inaction. Akarm is actions that are performed without attachment to the results, merely for the pleasure of God. They neither have any karmic reactions nor do they entangle the soul.

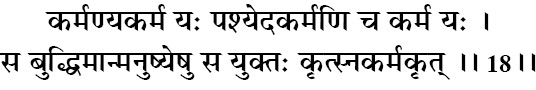

karmaṇyakarma yaḥ paśhyed akarmaṇi cha karma yaḥ

sa buddhimān manuṣhyeṣhu sa yuktaḥ kṛitsna-karma-kṛit

karmaṇi—action; akarma—in inaction; yaḥ—who; paśhyet—see; akarmaṇi—inaction; cha—also; karma—action; yaḥ—who; saḥ—they; buddhi-mān—wise; manuṣhyeṣhu—amongst humans; saḥ—they; yuktaḥ—yogis; kṛitsna-karma-kṛit—performers all kinds of actions.

Those who see action in inaction and inaction in action are truly wise amongst humans. Although performing all kinds of actions, they are yogis and masters of all their actions.

Action in inaction. There is one kind of inaction where persons look upon their social duties as burdensome, and renounce them out of indolence. They give up actions physically, but their mind continues to contemplate upon the objects of the senses. Such persons may appear to be inactive, but their lethargic idleness is actually sinful action. When Arjun suggested that he wishes to shy away from his duty of fighting the war, Shree Krishna explained to him that it would be a sin, and he would go to the hellish regions for such inaction.

Inaction in action. There is another kind of inaction performed by karm yogis. They execute their social duties without attachment to results, dedicating the fruits of their actions to God. Although engaged in all kinds of activities, they are not entangled in karmic reactions, since they have no motive for personal enjoyment. There were many great kings in Indian history—Dhruv, Prahlad, Yudhisthir, Prithu, and Ambarish—who discharged their kingly duties to the best of their abilities, and yet because their minds were not entangled in material desires, their actions were termed Akarm, or inaction. Another name for akarm is karm yog, which has been discussed in detail in the previous two chapters as well.

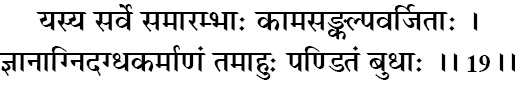

yasya sarve samārambhāḥ kāma-saṅkalpa-varjitāḥ

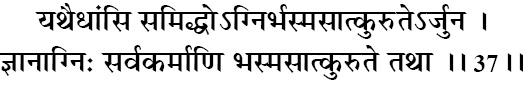

jñānāgni-dagdha-karmāṇaṁ tam āhuḥ paṇḍitaṁ budhāḥ

yasya—whose; sarve—every; samārambhāḥ—undertakings; kāma—desire for material pleasures; saṅkalpa—resolve; varjitāḥ—devoid of; jñāna—divine knowledge; agni—in the fire; dagdha—burnt; karmāṇam—actions; tam—him; āhuḥ—address; paṇḍitam—a sage; budhāḥ—the wise.

The enlightened sages call those persons wise, whose every action is free from the desire for material pleasures and who have burnt the reactions of work in the fire of divine knowledge.

The soul, being a tiny part of God who is an ocean of bliss, naturally seeks bliss for itself. However, covered by the material energy, the soul mistakenly identifies itself with the material body. In this ignorance, it performs actions to attain bliss from the world of matter. Since these actions are motivated by the desire for sensual and mental enjoyment, they bind the soul in karmic reactions.

In contrast, when the soul is illumined with divine knowledge, it realizes that the bliss it seeks will be attained not from the objects of the senses, but in loving service to God. It then strives to perform every action for the pleasure of God. “Whatever you do, whatever you eat, whatever you offer as oblation to the sacred fire, whatever you bestow as a gift, and whatever austerities you perform, O son of Kunti, do them as an offering to me.” (Bhagavad Gita 9.27) Since such an enlightened soul renounces selfish actions for material pleasures and dedicates all actions to God, the works performed produce no karmic reactions. They are said to be burnt in the fire of divine knowledge.

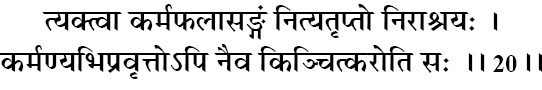

tyaktvā karma-phalāsaṅgaṁ nitya-tṛipto nirāśhrayaḥ

karmaṇyabhipravṛitto ’pi naiva kiñchit karoti saḥ

tyaktvā—having given up; karma-phala-āsaṅgam—attachment to the fruits of action; nitya—always; tṛiptaḥ—satisfied; nirāśhrayaḥ—without dependence; karmaṇi—in activities; abhipravṛittaḥ—engaged; api—despite; na—not; eva—certainly; kiñchit—anything; karoti—do; saḥ—that person.

Such people, having given up attachment to the fruits of their actions, are always satisfied and not dependent on external things. Despite engaging in activities, they do not do anything at all.

Actions cannot be classified by external appearances. It is the state of the mind that determines what is inaction and action. The minds of enlightened persons are absorbed in God. Being fully satisfied in devotional union with him, they look upon God as their only refuge and do not depend upon external supports. In this state of mind, all their actions are termed as akarm, or inactions.

There is a beautiful story in the Puranas to illustrate this point. The gopīs (cowherd women) of Vrindavan once kept a fast. The ceremony of breaking the fast required them to feed a sage. Shree Krishna advised them to feed Sage Durvasa, the elevated ascetic, who lived on the other side of River Yamuna. The gopīs prepared a delicious feast and started off, but found the river was very turbulent that day, and no boatman was willing to ferry them across.

The gopīs asked Shree Krishna for a solution. He said, “Tell River Yamuna that if Shree Krishna is an akhaṇḍ brahmacharī (perfectly celibate since birth), it should give them way.” The gopīs started laughing, because they felt that Shree Krishna used to dote upon them, and so there was no question of his being an akhaṇḍ brahmacharī. Nevertheless, when they requested River Yamuna in that manner, the river gave them way and a bridge of flowers manifested for their passage across.

The gopīs were astonished. They went across to the āśhram of Sage Durvasa. They requested him to accept the delicious meal they had brought for him. Being an ascetic, he ate only a small portion, which disappointed the gopīs. So, Durvasa decided to fulfill their expectations, and using his mystic powers, he ate everything they had brought. The gopīs were amazed to see him eat so much, but were very pleased that he had done justice to their cooking.

The gopīs now asked Durvasa for help to cross the Yamuna and return to the other side. He replied, “Tell River Yamuna that if Durvasa has not eaten anything today except doob (a kind of grass which was the only thing Durvasa used to eat), the river should give way.” The gopīs again started laughing, for they had seen him eat such an extravagant meal. Yet to their utmost surprise, when they beseeched River Yamuna in that manner, the river again gave them way.

The gopīs asked Shree Krishna the secret behind what had happened. He explained that while God and the Saints appear to engage in material activities externally, internally they are always transcendentally situated. Thus, even while doing all kinds of actions, they are still considered to be non-doers. Although interacting with the gopīs externally, Shree Krishna was an akhaṇḍ brahmacharī internally. And though Durvasa ate the delectable meal offered by the gopīs, internally his mind only tasted the doob grass. Both these were illustrations of inaction in action.

nirāśhīr yata-chittātmā tyakta-sarva-parigrahaḥ

śhārīraṁ kevalaṁ karma kurvan nāpnoti kilbiṣham

nirāśhīḥ—free from expectations; yata—controlled; chitta-ātmā—mind and intellect; tyakta—having abandoned; sarva—all; parigrahaḥ—the sense of ownership; śhārīram—bodily; kevalam—only; karma—actions; kurvan—performing; na—never; āpnoti—incurs; kilbiṣham—sin.

Free from expectations and the sense of ownership, with mind and intellect fully controlled, they incur no sin, even though performing actions by one’s body.

Even according to worldly law, acts of violence that happen accidentally are not considered as punishable offences. If one is driving a car in the correct lane, at the correct speed, with eyes fixed ahead, and someone suddenly comes and falls in front of the car and dies as a result, the court of law will not consider it as a culpable offence, provided it can be proved that the person had no intention to maim or kill. It is the intention of the mind that is of primary importance, and not the action. Similarly, the mystics who work in divine consciousness are released from all sins, because their mind is free from attachment and proprietorship, and their every act is performed with the divine intention of pleasing God.

yadṛichchhā-lābha-santuṣhṭo dvandvātīto vimatsaraḥ

samaḥ siddhāvasiddhau cha kṛitvāpi na nibadhyate

yadṛichchhā—which comes of its own accord; lābha—gain; santuṣhṭaḥ—contented; dvandva—duality; atītaḥ—surpassed; vimatsaraḥ—free from envy; samaḥ—equipoised; siddhau—in success; asiddhau—failure; cha—and; kṛitvā—performing; api—even; na—never; nibadhyate—is bound.

Content with whatever gain comes of its own accord, and free from envy, they are beyond the dualities of life. Being equipoised in success and failure, they are not bound by their actions, even while performing all kinds of activities.

Just like there are two sides to a coin, so too God created this world full of dualities—there is day and night, sweet and sour, hot and cold, rain and drought, etc. The same rose bush has a beautiful flower and also an ugly thorn. Life too brings its share of dualities—happiness and distress, victory and defeat, fame and notoriety. Lord Ram himself, in his divine pastimes, was exiled to the forest the day before he was to be crowned as the king of Ayodhya.

While living in this world, nobody can hope to neutralize the dualities to have only positive experiences. Then how can we successfully deal with the dualities that come our way in life? The solution is to take these dualities in stride, by learning to rise above them in equipoise in all situations. This happens when we develop detachment to the fruits of our actions, concerning ourselves merely with doing our duty in life without yearning for the results. When we perform works for the pleasure of God, we see both positive and negative fruits of those works as the will of God, and joyfully accept both.

gata-saṅgasya muktasya jñānāvasthita-chetasaḥ

yajñāyācharataḥ karma samagraṁ pravilīyate

gata-saṅgasya—free from material attachments; muktasya—of the liberated; jñāna-avasthita—established in divine knowledge; chetasaḥ—whose intellect; yajñāya—as a sacrifice (to God); ācharataḥ—performing; karma—action; samagram—completely; pravilīyate—are freed.

They are released from the bondage of material attachments and their intellect is established in divine knowledge. Since they perform all actions as a sacrifice (to God), they are freed from all karmic reactions.

In this verse, Lord Krishna summarizes the conclusion of the previous five verses. Dedication of all one’s actions to God results from the understanding that the soul is eternal servitor of God. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu said: jīvera svarūpa haya kṛiṣhṇera nitya-dāsa (Chaitanya Charitāmṛit, Madhya Leela, 20.108) [v18] “The soul is by nature the servant of God.” Those who are established in this knowledge perform all their actions as an offering to him and are released from the sinful reactions of their work.

What is the kind of vision that such souls develop? Shree Krishna explains this in the next verse.

brahmārpaṇaṁ brahma havir brahmāgnau brahmaṇā hutam

brahmaiva tena gantavyaṁ brahma-karma-samādhinā

brahma—Brahman; arpaṇam—the ladle and other offerings; brahma—Brahman; haviḥ—the oblation; brahma—Brahman; agnau—in the sacrificial fire; brahmaṇā—by that person; hutam—offered; brahma—Brahman; eva—certainly; tena—by that; gantavyam—to be attained; brahma—Brahman; karma—offering; samādhinā—those completely absorbed in God-consciousness.

For those who are completely absorbed in God-consciousness, the oblation is Brahman, the ladle with which it is offered is Brahman, the act of offering is Brahman, and the sacrificial fire is also Brahman. Such persons, who view everything as God, easily attain him.

Factually, the objects of the world are made from Maya, the material energy of God. Energy is both one with its energetic and also different from it. For example, light is the energy of fire. It can be considered as different from the fire, because it exists outside it. But it can also be reckoned as a part of the fire itself. Hence, when the rays of the sun enter the room through a window, people say, “The sun has come.” Here, they are bundling the sunrays with the sun. The energy is both distinct from the energetic and yet a part of it.

The soul too is the energy of God—it is a spiritual energy, called jīva śhakti. Shree Krishna states this in verses 7.4 and 7.5. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu stated:

jīva-tattva śhakti, kṛiṣhṇa-tattva śhaktimān

gītā-viṣhṇupurāṇādi tāhāte pramāṇa

(Chaitanya Charitāmṛit, Ādi Leela, 7.117) [v19]

“Lord Krishna is the energetic and the soul is his energy. This has been stated in Bhagavad Gita, Viṣhṇu Purāṇ, etc.” Thus, the soul is also simultaneously one with and different from God. Hence, those whose minds are fully absorbed in God-consciousness see the whole world in its unity with God as non-different from him. The Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam states:

sarva-bhūteṣhu yaḥ paśhyed bhagavad-bhāvam ātmanaḥ

bhūtāni bhagavatyātmanyeṣha bhāgavatottamaḥ (11.2.45) [v20]

“One who sees God everywhere and in all beings is the highest spiritualist.” For such advanced spiritualists whose minds are completely absorbed in God-consciousness, the person making the sacrifice, the object of the sacrifice, the instruments of the sacrifice, the sacrificial fire, and the act of sacrifice, are all perceived as non-different from God.

Having explained the spirit in which sacrifice is to be done, Lord Krishna now relates the different kinds of sacrifice people perform in this world for purification.

daivam evāpare yajñaṁ yoginaḥ paryupāsate

brahmāgnāvapare yajñaṁ yajñenaivopajuhvati

daivam—the celestial gods; eva—indeed; apare—others; yajñam—sacrifice; yoginaḥ—spiritual practioners; paryupāsate—worship; brahma—of the Supreme Truth; agnau—in the fire; apare—others; yajñam—sacrifice; yajñena—by sacrifice; eva—indeed; upajuhvati—offer.

Some yogis worship the celestial gods with material offerings unto them. Others worship perfectly who offer the self as sacrifice in the fire of the Supreme Truth.

Sacrifice, or yajña, should be performed in divine consciousness as an offering to the Supreme Lord. However, people vary in their understanding, and hence perform sacrifice in different manners with dissimilar consciousness. Persons with lesser understanding, and wanting material rewards, make offerings to the celestial gods.

Others with deeper understanding of the meaning of yajña offer their own selves as sacrifice to the Supreme. This is called ātma samarpaṇ, or ātmāhutī, or offering one’s soul to God. Yogi Shri Krishna Prem explained this very well: “In this world of dust and din, whenever one makes ātmāhutī in the flame of divine love, there is an explosion, which is grace, for no true ātmāhutī can ever go in vain.” But what is the process of offering one’s own self as sacrifice? This is performed by surrendering oneself completely to God. Such surrender has six aspects to it, which have been explained in verse 18.66. Here, Shree Krishna continues to explain the different kinds of sacrifice that people perform.

śhrotrādīnīndriyāṇyanye sanyamāgniṣhu juhvati

śhabdādīn viṣhayānanya indriyāgniṣhu juhvati

śhrotra-ādīni—such as the hearing process; indriyāṇi—senses; anye—others; sanyama—restraint; agniṣhu—in the sacrficial fire; juhvati—sacrifice; śhabda-ādīn—sound vibration, etc.; viṣhayān—objects of sense-gratification; anye—others; indriya—of the senses; agniṣhu—in the fire; juhvati—sacrifice.

Others offer hearing and other senses in the sacrificial fire of restraint. Still others offer sound and other objects of the senses as sacrifice in the fire of the senses.

Fire transforms the nature of things consigned into it. In external ritualistic Vedic sacrifices, it physically consumes oblations offered to it. In the internal practice of spirituality, fire is symbolic. The fire of self-discipline burns the desires of the senses.

Here, Shree Krishna distinguishes between two diametrically opposite approaches to spiritual elevation. One is the path of negation of the senses, which is followed in the practice of haṭha yog. In this type of yajña (sacrifice), the actions of the senses are suspended, except for the bare maintenance of the body. The mind is completely withdrawn from the senses and made introvertive, by force of will-power.

Opposite to this is the practice of bhakti yog. In this second type of yajña, the senses are made to behold the glory of the Creator that manifests in every atom of his creation. The senses no longer remain as instruments for material enjoyment; rather they are sublimated to perceive God in everything. In verse 7.8, Shree Krishna says: raso 'ham apsu kaunteya “Arjun, know me to be the taste in water.” Accordingly, bhakti yogis practice to behold God through all their senses, in everything they see, hear, taste, feel, and smell. This yajña of devotion is simpler than the path of haṭha yog; it is joyous to perform, and involves a smaller risk of downfall from the path. If one is riding a bicycle and presses the brakes to stop the forward motion, he will be in an unstable condition, but if the cyclist simply turns the handle to the left or right, the bicycle will very easily stop its forward motion and still remain stably balanced.

sarvāṇīndriya-karmāṇi prāṇa-karmāṇi chāpare

ātma-sanyama-yogāgnau juhvati jñāna-dīpite

sarvāṇi—all; indriya—the senses; karmāṇi—functions; prāṇa-karmāṇi—functions of the life breath; cha—and; apare—others; ātma-sanyama yogāgnau—in the fire of the controlled mind; juhvati—sacrifice; jñāna-dīpite—kindled by knowledge.

Some, inspired by knowledge, offer the functions of all their senses and their life energy in the fire of the controlled mind.

There are some yogis who follow the path of discrimination, or jñāna yog, and take the help of knowledge to withdraw their senses from the world. While haṭha yogis strive to restrain the senses with brute will-power, jñāna yogis accomplish the same goal with the repeated practice of discrimination based on knowledge. They engage in deep contemplation upon the illusory nature of the world, and the identity of the self as distinct from the body, mind, intellect, and ego. The senses are withdrawn from the world, and the mind is engaged in meditation upon the self. The goal is to become practically situated in self-knowledge, in the assumption that the self is identical with the Supreme Ultimate reality. As aids to contemplation, they chant aphorisms such as: tattvamasi “I am That,” (Chhāndogya Upaniṣhad 6.8.7) [21] and ahaṁ brahmāsmi “I am the Supreme Entity.” (Bṛihadāraṇyak Upaniṣhad 1.4.10) [v22]

The practice of jñāna yog is a very difficult path, which requires a very determined and trained intellect. The Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam (11.20.7) states: nirviṇṇānāṁ jñānayogaḥ [23] “Success in the practice of jñāna yog is only possible for those who are at an advanced stage of renunciation.”

dravya-yajñās tapo-yajñā yoga-yajñās tathāpare

swādhyāya-jñāna-yajñāśh cha yatayaḥ sanśhita-vratāḥ

dravya-yajñāḥ—offering one's own wealth as sacrife; tapaḥ-yajñāḥ—offering severe austerities as sacrifice; yoga-yajñāḥ—performance of eight-fold path of yogic practices as sacrifice; tathā—thus; apare—others; swādhyāya—cultivating knowledge by studying the scriptures; jñāna-yajñāḥ—those offer cultivation of transcendental knowledge as sacrifice; cha—also; yatayaḥ—these ascetics; sanśhita-vratāḥ—observing strict vows.

Some offer their wealth as sacrifice, while others offer severe austerities as sacrifice. Some practice the eight-fold path of yogic practices, and yet others study the scriptures and cultivate knowledge as sacrifice, while observing strict vows.

Human beings differ from each other in their natures, motivations, activities, professions, aspirations, and sanskārs (tendencies carrying forward from past lives). Shree Krishna brings Arjun to the understanding that sacrifices can take on hundreds of forms, but when they are dedicated to God, they become means of purification of the mind and senses and elevation of the soul. In this verse, he mentions three such yajñas that can be performed.

Dravya yajña. There are those who are inclined toward earning wealth and donating it in charity toward a divine cause. Although they may engage in large and complicated business endeavors, yet their inner motivation remains to serve God with the wealth they earn. In this manner, they offer their propensity for earning money as sacrifice to God in devotion. John Wesley, the British preacher and founder of the Methodist Church would instruct his followers: “Make all you can. Save all you can. Give all you can.”

Yog yajña. In Indian philosophy the Yog Darśhan is one of the six philosophical treatises written by six learned sages. Jaimini wrote “Mīmānsā Darśhan,” Ved Vyas wrote “Vedānt Darśhan,” Gautam wrote “Nyāya Darśhan,” Kanad wrote “Vaiśheṣhik Darśhan,” Kapil wrote “Sānkhya Darśhan,” and Patañjali wrote “Yog Darśhan.” The Patañjali Yog Darśhan describes an eight-fold path, called aṣhṭāṅg yog, for spiritual advancement, starting with physical techniques and ending in conquest of the mind. Some people find this path attractive and practice it as sacrifice. However, Patañjali Yog Darśhan clearly states:

samādhisiddhirīśhvara praṇidhānāt (2.45) [v24]

“To attain perfection in Yog, you must surrender to God.” So when persons inclined toward aṣhṭang yog learn to love God, they offer their yogic practice as yajña in the fire of devotion. An example of this is the yogic system “Jagadguru Kripaluji Yog,” where the physical postures of aṣhṭaṅg yog are practiced as yajña to God, along with the chanting of his divine names. Such a combination of yogic postures along with devotion results in the physical, mental, and spiritual purification of the practitioner.

Jñāna yajña. Some persons are inclined toward the cultivation of knowledge. This propensity finds its perfect employment in the study of scriptures for enhancing one’s understanding and love for God. sā vidyā tanmatiryayā (Bhāgavatam 4.29.49) [v25] “True knowledge is that which increases our devotion to God.” Thus, studiously inclined sādhaks engage in the sacrifice of knowledge, which when imbued with the spirit of devotion, leads to loving union with God.

apāne juhvati prāṇaṁ prāṇe ’pānaṁ tathāpare

prāṇāpāna-gatī ruddhvā prāṇāyāma-parāyaṇāḥ

apare niyatāhārāḥ prāṇān prāṇeṣhu juhvati

sarve ’pyete yajña-vido yajña-kṣhapita-kalmaṣhāḥ

apāne—the incoming breath; juhvati—offer; prāṇam—the outgoing breath; prāṇe—in the outgoing breath; apānam—incoming breath; tathā—also; apare—others; prāṇa—of the outgoing breath; apāna—and the incoming breath; gatī—movement; ruddhvā—blocking; prāṇa-āyāma—control of breath; parāyaṇāḥ—wholly devoted; apare—others; niyata—having controlled; āhārāḥ—food intake; prāṇān—life-breaths; prāṇeṣhu—life-energy; juhvati—sacrifice; sarve—all; api—also; ete—these; yajña-vidaḥ—knowers of sacrifices; yajña-kṣhapita—being cleansed by performances of sacrifices; kalmaṣhāḥ—of impurities.

Still others offer as sacrifice the outgoing breath in the incoming breath, while some offer the incoming breath into the outgoing breath. Some arduously practice prāṇāyām and restrain the incoming and outgoing breaths, purely absorbed in the regulation of the life-energy. Yet others curtail their food intake and offer the breath into the life-energy as sacrifice. All these knowers of sacrifice are cleansed of their impurities as a result of such performances.

Some persons are drawn to the practice of prāṇāyām, which is loosely translated as “control of breath.” This involves:

Pūrak—the process of drawing the breath into the lungs.

Rechak—the process of emptying the lungs of breath.

Antar kumbhak—holding the breath in the lungs after inhalation. The outgoing breath gets suspended in the incoming breath during the period of suspension.

Bāhya kumbhak—keeping the lungs empty after exhalation. The incoming breath gets suspended in the outgoing breath during the period of suspension.

Both the kumbhaks are advanced techniques and should only be practiced under the supervision of qualified teachers, else they can cause harm. Yogis who are inclined toward the practice of prāṇāyām utilize the process of breath control to help tame the senses and bring the mind into focus. Then they offer the controlled mind in the spirit of yajña to the Supreme Lord.

Prāṇ is not exactly breath; it is a subtle life force energy that pervades the breath and varieties of animate and inanimate objects. The Vedic scriptures describe five kinds of prāṇas in the body—prāṇ, apān, vyān, samān, udān—that help regulate various physiological bodily functions. Amongst these, samān is responsible for the bodily function of digestion. Some people may also be inclined toward fasting. They curtail their eating with the knowledge that diet impacts character and behavior. Such fasting has been employed as a spiritual technique in India since ancient times and also considered here a form of yajña. When the diet is curtailed, the senses become weak and the samān, which is responsible for digestion, is made to neutralize itself. This is the nature of the sacrifice that some people perform.

People perform these various kinds of austerities for the purpose of purification. It is desire for gratification of the senses and the mind which leads to the heart becoming impure. The aim of all these austerities is to curtail the natural propensity of the senses and mind to seek pleasure in material objects. When these austerities are performed as a sacrifice to the Supreme, they result in the purification of the heart (as mentioned before, the word “heart” is often used to refer to the internal machinery of the mind and intellect).

yajña-śhiṣhṭāmṛita-bhujo yānti brahma sanātanam

nāyaṁ loko ’styayajñasya kuto ’nyaḥ kuru-sattama

yajña-śhiṣhṭa amṛita-bhujaḥ—they partake of the nectarean remnants of sacrifice; yānti—go; brahma—the Absolute Truth; sanātanam—eternal; na—never; ayam—this; lokaḥ—planet; asti—is; ayajñasya—for one who performs no sacrifice; kutaḥ—how; anyaḥ—other (world); kuru-sat-tama—best of the Kurus, Arjun.

Those who know the secret of sacrifice, and engaging in it, partake of its remnants that are like nectar, advance toward the Absolute Truth. O best of the Kurus, those who perform no sacrifice find no happiness either in this world or the next.

The secret of sacrifice, as mentioned previously, is the understanding that it should be performed for the pleasure of God, and then the remnants can be taken as his prasād (grace). For example, devotees of the Lord partake of food after offering it to him. After cooking the food, they place it on the altar and pray to God to accept their offering. In their mind, they meditate on the sentiment that God is actually eating from the plate. At the end of the offering, the remnants on the plate are accepted as prasād, or the grace of God. Partaking of such nectar-like prasād leads to illumination, purification, and spiritual advancement.

In the same mood, devotees offer clothes to God and then wear them as his prasād. They install his deity in their house, and then live in it with the attitude that their home is the temple of God. When objects or activities are offered as sacrifice to God, then the remnants, or prasād, are a nectar-like blessing for the soul. The great devotee Uddhav told Shree Krishna:

tvayopabhukta-srag-gandha-vāso ’laṅkāra-charchitāḥ

uchchhiṣhṭa-bhojino dāsās tava māyāṁ jayema hi

(Bhāgavatam 11.6.46) [v26]

“I will only eat, smell, wear, live in, and talk about objects that have first been offered to you. In this way, by accepting the remnants as your prasād, I will easily conquer Maya.” Those who do not perform sacrifice remain entangled in the fruitive reactions of work and continue to experience the torments of Maya.

evaṁ bahu-vidhā yajñā vitatā brahmaṇo mukhe

karma-jān viddhi tān sarvān evaṁ jñātvā vimokṣhyase

evam—thus; bahu-vidhāḥ—various kinds of; yajñāḥ—sacrifices; vitatāḥ—have been described; brahmaṇaḥ—of the Vedas; mukhe—through the mouth; karma-jān—originating from works; viddhi—know; tān—them; sarvān—all; evam—thus; jñātvā—having known; vimokṣhyase—you shall be liberated.

All these different kinds of sacrifice have been described in the Vedas. Know them as originating from different types of work; this understanding cuts the knots of material bondage.

One of the beautiful features of the Vedas is that they recognize and cater to the wide variety of human natures. Different kinds of sacrifice have thus been described for different kinds of performers. The common thread running through them is that they are to be done with devotion, as an offering to God. With this understanding, one is not bewildered by the multifarious instructions in the Vedas, and by pursuing the particular yajña suitable to one’s nature, one can be released from material bondage.

śhreyān dravya-mayād yajñāj jñāna-yajñaḥ parantapa

sarvaṁ karmākhilaṁ pārtha jñāne parisamāpyate

śhreyān—superior; dravya-mayāt—of material possessions; yajñāt—than the sacrifice; jñāna-yajñaḥ—sacrifice performed in knowledge; parantapa—subduer of enemies, Arjun; sarvam—all; karma—works; akhilam—all; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; jñāne—in knowledge; parisamāpyate—culminate.

O subduer of enemies, sacrifice performed in knowledge is superior to any mechanical material sacrifice. After all, O Parth, all sacrifices of work culminate in knowledge.

Shree Krishna now puts the previously described sacrifices in proper perspective. He tells Arjun that it is good to do physical acts of devotion, but not good enough. Ritualistic ceremonies, fasts, mantra chants, holy pilgrimages, are all fine, but if they are not performed with knowledge, they remain mere physical activities. Such mechanical activities are better than not doing anything at all, but they are not sufficient to purify the mind.

Many people chant God’s name on rosary beads, sit in recitations of the scriptures, visit holy places, and perform worship ceremonies, with the belief that the physical act itself is sufficient for liberating them from material bondage. However, Saint Kabir rejects this idea very eloquently:

mālā pherata yuga phirā, phirā na mana kā pher,

kar kā manakā ḍāri ke, manakā manakā pher. [v27]

“O spiritual aspirant, you have been rotating the chanting beads for many ages, but the mischief of the mind has not ceased. Now put those beads down, and rotate the beads of the mind.” Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj says:

bandhan aur mokṣha kā, kāraṇ manahi bakhān

yate kauniu bhakti karu, karu man te haridhyān

(Bhakti Shatak verse 19) [v28]

“The cause of bondage and liberation is the mind. Whatever form of devotion you do, engage your mind in meditating upon God.”

Devotional sentiments are nourished by the cultivation of knowledge. For example, let us say that it is your birthday party, and people are coming and handing you gifts. Someone comes and gives you a ragged bag. You look at it disdainfully, thinking it is insignificant in comparison to the other wonderful gifts you have received. That person requests you to look inside the bag. You open it and find a stack of one hundred notes of $100 denomination. You immediately hug the bag to your chest, and say, “This is the best gift I have received.” Knowledge of its contents developed love for the object. Similarly, cultivating knowledge of God and our relationship with him nurtures devotional sentiments. Hence, Shree Krishna explains to Arjun that sacrifices performed in knowledge are superior to the sacrifice of material things. He now explains the process of acquiring knowledge.

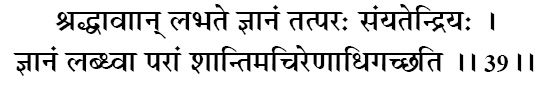

tad viddhi praṇipātena paripraśhnena sevayā

upadekṣhyanti te jñānaṁ jñāninas tattva-darśhinaḥ

tat—the Truth; viddhi—try to learn; praṇipātena—by approaching a spiritual master; paripraśhnena—by humble inquiries; sevayā—by rendering service; upadekṣhyanti—can impart; te—unto you; jñānam—knowledge; jñāninaḥ—the enlightened; tattva-darśhinaḥ—those who have realized the Truth.

Learn the Truth by approaching a spiritual master. Inquire from him with reverence and render service unto him. Such an enlightened Saint can impart knowledge unto you because he has seen the Truth.

On hearing that sacrifice should be performed in knowledge, the natural question that follows is, how can we obtain spiritual knowledge? Shree Krishna gives the answer in this verse. He says: 1) Approach a spiritual master. 2) Inquire from him submissively. 3) Render service to him.

The Absolute Truth cannot be understood merely by our own contemplation. The Bhāgavatam states:

anādyavidyā yuktasya puruṣhasyātma vedanam

svato na sambhavād anyas tattva-jño jñāna-do bhavet (11.22.10) [v29]

“The intellect of the soul is clouded by ignorance from endless lifetimes. Covered with nescience, the intellect cannot overcome its ignorance simply by its own effort. One needs to receive knowledge from a God-realized Saint who knows the Absolute Truth.”

The Vedic scriptures advise us repeatedly on the importance of the Guru on the spiritual path.

āchāryavān puruṣho vedaḥ (Chhāndogya Upaniṣhad 6.14.2) [v30]

“Only through a Guru can you understand the Vedas.” The Pañchadaśhī states:

tatpādāmburu hadvandva sevā nirmala chetasām

sukhabodhāya tattvasya viveko ’yaṁ vidhīyate (1.2) [v31]