Dhyān Yog

The Yog of Meditation

In this chapter, Shree Krishna continues the comparative evaluation of karm yog (practicing spirituality while continuing the worldly duties) and karm sanyās (practicing spirituality in the renounced order) from chapter five and recommends the former. When we perform work in devotion, it purifies the mind and deepens our spiritual realization. Then when the mind becomes tranquil, meditation becomes the primary means of elevation. Through meditation, yogis strive to conquer their mind, for while the untrained mind is the worst enemy, the trained mind is the best friend. Shree Krishna cautions Arjun that one cannot attain success on the spiritual path by engaging in severe austerities, and hence one must be temperate in eating, work, recreation, and sleep. He then explains the sādhanā for uniting the mind with God. Just as a lamp in a windless place does not flicker, likewise the sādhak must hold the mind steady in meditation. The mind is indeed difficult to restrain, but by practice and detachment, it can be controlled. So, wherever it wanders, one should bring it back and continually focus it upon God. When the mind gets purified, it becomes established in transcendence. In that joyous state called samādhi, one experiences boundless divine bliss.

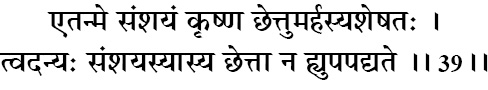

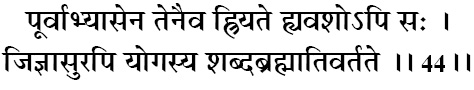

Arjun then questions Shree Krishna about the fate of the aspirant who begins on the path, but is unable to reach the goal due to an unsteady mind. Shree Krishna reassures him that one who strives for God-realization is never overcome by evil. God always keeps account of our spiritual merits accumulated in previous lives and reawakens that wisdom in future births, so that we may continue the journey from where we had left off. With the accrued merits of many past lives, yogis are able to reach God in their present life itself. The chapter concludes with a declaration that the yogi (one who strives to unite with God) is superior to the tapasvī (ascetic), the jñānī (person of learning), and the karmī (ritualistic performer). And amongst all yogis, one who engages in bhakti (loving devotion to God) is the highest of all.

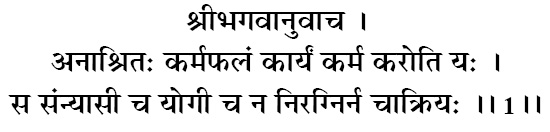

śhrī bhagavān uvācha

anāśhritaḥ karma-phalaṁ kāryaṁ karma karoti yaḥ

sa sanyāsī cha yogī cha na niragnir na chākriyaḥ

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Supreme Lord said; anāśhritaḥ—not desiring; karma-phalam—results of actions; kāryam—obligatory; karma—work; karoti—perform; yaḥ—one who; saḥ—that person; sanyāsī—in the renounced order; cha—and; yogī—yogi; cha—and; na—not; niḥ—without; agniḥ—fire; na—not; cha—also; akriyaḥ—without activity.

The Supreme Lord said: Those who perform prescribed duties without desiring the results of their actions are actual sanyāsīs (renunciates) and yogis, not those who have merely ceased performing sacrifices such as agni-hotra yajña or abandoned bodily activities.

The ritualistic activities described in the Vedas include fire sacrifices, such as agnihotra yajña. The rules for those who enter the renounced order of sanyās state that they should not perform the ritualistic karm kāṇḍ activities; in fact they should not touch fire at all, not even for the purpose of cooking. And they should subsist on alms instead. However, Shree Krishna states in this verse that merely giving up the sacrificial fire does not make one a sanyāsī (renunciant).

Who are true yogis, and who are true sanyāsīs? There is much confusion in this regard. People say, “This swamiji is phalāhārī (one who eats only fruits and nothing else), and so he must be an elevated yogi.” “This bābājī (renunciant) is dūdhāhārī (subsists on milk alone), and hence he must be an even higher yogi.” “This guruji is pavanāhārī (does not eat, lives only on the breath), and so he must definitely be God-realized.” “This sadhu is a nāgā bābā (ascetic who does not wear clothes), and thus he is perfectly renounced.” However, Shree Krishna dismisses all these concepts. He says that such external acts of asceticism do not make anyone either a sanyāsī or a yogi. Those who can renounce the fruits of their actions, by offering them to God, are the true renunciants and yogis.

Nowadays Yoga has become the buzz word in the western world. Numerous Yoga studios have sprung up in every town of every country of the world. Statistics reveal that one out of every ten persons in America is practicing Yoga. But this word “Yoga” does not exist in the Sanskrit scriptures. The actual word is “Yog,” which means “union.” It refers to the union of the individual consciousness with the divine consciousness. In other words, a yogi is one whose mind is fully absorbed in God. It also follows that such a yogi’s mind is naturally detached from the world. Hence, the true yogi is also the true sanyāsī.

Persons who perform karm yog do all activities in the spirit of humble service to God without any desire whatsoever for rewards. Even though they may be gṛihasthas (living with a family), such persons are true yogis and the real renunciants.

yaṁ sanyāsam iti prāhur yogaṁ taṁ viddhi pāṇḍava

na hyasannyasta-saṅkalpo yogī bhavati kaśhchana

yam—what; sanyāsam—renunciation; iti—thus; prāhuḥ—they say; yogam—yog; tam—that; viddhi—know; pāṇḍava—Arjun, the son of Pandu; na—not; hi—certainly; asannyasta—without giving up; saṅkalpaḥ—desire; yogī—a yogi; bhavati—becomes; kaśhchana—anyone.

What is known as sanyās is non-different from Yog, for none become yogis without renouncing worldly desires.

A sanyāsī is one who renounces the pleasures of the mind and senses. But mere renunciation is not the goal, nor is it sufficient to reach the goal. Renunciation means that our running in the wrong direction has stopped. We were searching for happiness in the world, and we understood that there is no happiness in material pleasures, so we stopped running toward the world. But, the destination is not reached just by stopping. The destination of the soul is God-realization. The process of going toward God—taking the mind toward him—is the path of Yog. Those who have incomplete knowledge of the goal of life, look upon renunciation as the highest goal of spirituality. Those who truly understand the goal of life, regard God-realization as the ultimate goal of their spiritual endeavor.

In the purport to verse 5.4, it was explained that there are two kinds of renunciation—phalgu vairāgya and yukt vairāgya. Phalgu vairāgya is that where worldly objects are seen as objects of Maya, the material energy, and hence renounced because they are detrimental to spiritual progress. Yukt vairāgya is that where everything is seen as belonging to God, and hence meant to be utilized in his service. In the first kind of renunciation, one would say, “Give up money. Do not touch it. It is a form of Maya, and it impedes the path of spirituality.” In the second kind of renunciation, one would say, “Money is also a form of the energy of God. Do not waste it or throw it away; utilize whatever you have in your possession for the service of God.”

Phalgu vairāgya is unstable, and can easily revert to attachment for the world. The name “Phalgu” comes from a river in the city of Gaya, in the state of Bihar in India. The river Phalgu runs below the surface. From atop, it seems as if there is no water, but if you dig a few feet, you encounter the stream below. Similarly, many persons renounce the world to go and live in monasteries, only to find that in a few years the renunciation has vanished and the mind is again attached to the world. Their detachment was phalgu vairāgya. Finding the world to be troublesome and miserable, they desired to get away from it by taking shelter in monastery. But when they found spiritual life also to be difficult and arduous, they got detached from spirituality as well. Then there are others who establish their loving relationship with God. Motivated by the desire to serve him, they renounce the world to live in a monastery. Their renunciation is yukt vairāgya. They usually continue the journey even if they face difficulties.

In the first line of this verse, Shree Krishna states that a real sanyāsī (renunciant) is one who is a yogi, i.e. one who is uniting the mind with God in loving service. In the second line, Shree Krishna states that one cannot be a yogi without giving up material desires. If there are material desires in the mind, then it will naturally run toward the world. Since it is the mind that has to be united with God, this is only possible if the mind is free from all material desires. Thus, to be a yogi one has to be a sanyāsī from within; and one can only be a sanyāsī if one is a yogi.

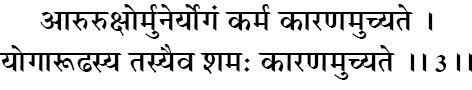

ārurukṣhor muner yogaṁ karma kāraṇam uchyate

yogārūḍhasya tasyaiva śhamaḥ kāraṇam uchyate

ārurukṣhoḥ—a beginner; muneḥ—of a sage; yogam—Yog; karma—working without attachment; kāraṇam—the cause; uchyate—is said; yoga ārūḍhasya—of those who are elevated in Yog; tasya—their; eva—certainly; śhamaḥ—meditation; kāraṇam—the cause; uchyate—is said.

To the soul who is aspiring for perfection in Yog, work without attachment is said to be the means; to the sage who is already elevated in Yog, tranquility in meditation is said to be the means.

In chapter 3, verse 2, Shree Krishna mentioned that there are two paths for attaining welfare—the path of contemplation and the path of action. Between these, he recommended to Arjun to follow the path of action. Again in chapter 5, verse 2, he declared it to be the better path. Does this mean that we must keep doing work all our life? Anticipating such a question, Shree Krishna sets the limits for it. When we perform karm yog, it leads to the purification of the mind and the ripening of spiritual knowledge. But once the mind has been purified and we advance in Yog, then we can leave karm yog and take to karm sanyās. Material activities now serve no purpose and meditation now becomes the means.

So the path we must follow filters down to a matter of our eligibility and Shree Krishna explains the criteria of eligibility in this verse. He says that for those who are aspiring for Yog, the path of karm yog is more suitable; and those who are elevated in Yog, the path of karm sanyās is more suitable.

The word Yog refers to both the goal and the process to reach the goal. When we talk of it as being the goal, we use Yog as meaning “union with God.” And when we talk of it as being the process, we use Yog as meaning the “path” to union with God.

In this second context, Yog is like a ladder we climb to reach God. At the lowest rung, the soul is caught in worldliness, with the consciousness absorbed in mundane matter. The ladder of Yog takes the soul from that level to the stage where the consciousness is absorbed in the divine. The various rungs of the ladder have different names, but Yog is a term common to them all. Yog-ārurukṣhu are those sādhaks who aspire for union with God and have just begun climbing the ladder. Yog-ārūḍha are those who have become elevated on the ladder.

So, how do we understand when one is elevated in the science of Yog? Shree Krishna explains this next.

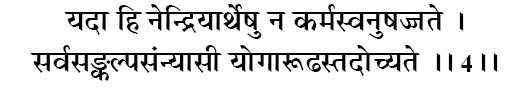

yadā hi nendriyārtheṣhu na karmasv-anuṣhajjate

sarva-saṅkalpa-sanyāsī yogārūḍhas tadochyate

yadā—when; hi—certainly; na—not; indriya-artheṣhu—for sense-objects; na—not; karmasu—to actions; anuṣhajjate—is attachment; sarva-saṅkalpa—all desires for the fruits of actions; sanyāsī—renouncer; yoga-ārūḍhaḥ—elevated in the science of Yog; tadā—at that time; uchyate—is said.

When one is neither attached to sense objects nor to actions, that person is said to be elevated in the science of Yog, for having renounced all desires for the fruits of actions.

As the mind becomes attached to God in Yog, it naturally becomes detached from the world. So an easy criterion of evaluating the state of one’s mind is to check whether it has become free from all material desires. A person will be considered detached from the world when one no longer craves for sense objects nor is inclined to perform any actions for attaining them. Such a person ceases to look for opportunities to create circumstances to enjoy sensual pleasures, eventually extinguishes all thoughts of enjoying sense objects, and also dissolves the memories of previous enjoyments.

The mind now no longer gushes into self-centered activities at the urge of the senses. When we achieve this level of mastery over the mind, we will be considered elevated in Yog.

uddhared ātmanātmānaṁ nātmānam avasādayet

ātmaiva hyātmano bandhur ātmaiva ripur ātmanaḥ

uddharet—elivate; ātmanā—through the mind; ātmānam—the self; na—not; ātmānam—the self; avasādayet—degrade; ātmā—the mind; eva—certainly; hi—indeed; ātmanaḥ—of the self; bandhuḥ—friend; ātmā—the mind; eva—certainly; ripuḥ—enemy; ātmanaḥ—of the self.

Elevate yourself through the power of your mind, and not degrade yourself, for the mind can be the friend and also the enemy of the self.

We are responsible for our own elevation or debasement. Nobody can traverse the path of God-realization for us. Saints and Gurus show us the way, but we have to travel it ourselves. There is a saying in Hindi: ek peḍa do pakṣhī baiṭhe, ek guru ek chelā, apanī karanī guru utare, apanī karanī chelā [v.01] “There are two birds sitting on a tree—one Guru and one disciple. The Guru will descend by his own works, and the disciple will also only be able to climb down by his own karmas.”

We have had innumerable lifetimes before this one, and God-realized Saints were always present on Earth. At any period of time, if the world is devoid of such Saints, then the souls of that period cannot become God-realized. How then can they fulfill the purpose of human life, which is God-realization? Thus, God ensures that God-realized Saints are always present in every era, to guide the sincere seekers and inspire humanity. So, in infinite past lifetimes, many times we must have met God-realized Saints and yet we did not become God-realized. This means that the problem was not lack of proper guidance, but either our reticence in accepting it or working according to it. Thus, we must first accept responsibility for our present level of spirituality, or lack thereof. Only then will we gain the confidence that if we have brought ourselves to our present state, we can also elevate ourselves by our efforts.

When we suffer reversals on the path of spiritual growth, we tend to complain that others have caused havoc to us, and they are our enemies. However, our biggest enemy is our own mind. It is the saboteur that thwarts our aspirations for perfection. Shree Krishna states that, on the one hand, as the greatest benefactor of the soul, the mind has the potential of giving us the most benefit; on the other hand, as our greatest adversary, it also has the potential for causing the maximum harm. A controlled mind can accomplish many beneficial endeavors, whereas an uncontrolled mind can degrade the consciousness with most ignoble thoughts.

In order to be able to use it as a friend, it is important to understand the mind’s nature. Our mind operates at four levels:

1. Mind: When it creates thoughts, we call it mana, or the mind.

2. Intellect: When it analyses and decides, we call it buddhi, or intellect.

3. Chitta: When it gets attached to an object or person, we call it chitta.

4. Ego: When it identifies with the bodily identifications and becomes proud of things like wealth, status, beauty, and learning, we call it ahankār, or ego.

These are not four separate entities. They are simply four levels of functioning of the one mind. Hence, we may refer to them all together as the mind, or as the mind-intellect, or as the mind-intellect-ego, or as the mind-intellect-chitta-ego. They all refer to the same thing.

The use of the word ego here is different from its connotation in Freudian psychology. Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939), an Austrian neurologist, proposed the first theory of psychology regarding how the mind works. According to him, the ego is the “real self” that bridges the gap between our untamed desires (Id) and the value system that is learnt during childhood (Superego).

Various scriptures describe the mind in one of these four ways for the purpose of explaining the concepts presented there. They are all referring to the same internal apparatus within us, which is together called antaḥ karaṇ, or the mind. For example:

- The Pañchadaśhī refers to all four together as the mind, and states that it is the cause of material bondage.

- In the Bhagavad Gita, Shree Krishna repeatedly talks of the mind and the intellect as being two things, and emphasizes the need to surrender both to God.

- The Yog Darśhan, while analyzing the different elements of nature, talks of three entities: mind, intellect, and ego.

- Shankaracharya, while explaining the apparatus available to the soul, classifies the mind into four—mind, intellect, chitta and ego.

So when Shree Krishna says that we must use the mind to elevate the self, he means we must use the higher mind to elevate the lower mind. In other words, we must use the intellect to control the mind. How this can be done has been explained in detail in verses 2.41 to 2.44 and again in verse 3.43.

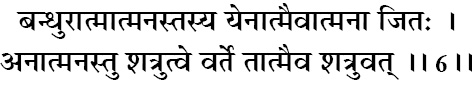

bandhur ātmātmanas tasya yenātmaivātmanā jitaḥ

anātmanas tu śhatrutve vartetātmaiva śhatru-vat

bandhuḥ—friend; ātmā—the mind; ātmanaḥ—for the person; tasya—of him; yena—by whom; ātmā—the mind; eva—certainly; ātmanā—for the person; jitaḥ—conquered; anātmanaḥ—of those with unconquered mind; tu—but; śhatrutve—for an enemy; varteta—remains; ātmā—the mind; eva—as; śhatru-vat—like an enemy.

For those who have conquered the mind, it is their friend. For those who have failed to do so, the mind works like an enemy.

We dissipate a large portion of our thought power and energy in combating people whom we perceive as enemies and potentially harmful to us. The Vedic scriptures say the biggest enemies—lust, anger, greed, envy, illusion, etc.—reside in our own mind. These internal enemies are even more pernicious than the outer ones. The external demons may injure us for some time, but the demons sitting within our own mind have the ability to make us live in constant wretchedness. We all know people who had everything favorable in the world, but lived miserable lives because their own mind tormented them incessantly through depression, hatred, tension, anxiety, and stress.

The Vedic philosophy lays great emphasis on the ramification of thoughts. Illness is not only caused by viruses and bacteria, but also by the negativities we harbor in the mind. If someone accidentally throws a stone at you, it may hurt for a few minutes, but by the next day, you will probably have forgotten about it. However, if someone says something unpleasant, it may continue to agitate your mind for years. This is the immense power of the thoughts. In the Buddhist scripture, the Dhammapada (1.3), the Buddha also expresses this truth vividly:

“I have been insulted! I have been hurt! I have been beaten! I have been robbed! Misery does not cease in those who harbor such thoughts.

I have been insulted! I have been hurt! I have been beaten! I have been robbed! Anger ceases in those who do not harbor such thoughts.”

When we nourish hatred in our mind, our negative thoughts do more damage to us than the object of our hatred. It has been very sagaciously stated: “Resentment is like drinking poison and hoping that the other person dies.” The problem is that most people do not even realize that their own uncontrolled mind is causing them so much harm. Hence, Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj advises:

mana ko māno śhatru usakī sunahu jani kachhu pyāre (Sādhan Bhakti Tattva) [v1]

“Dear spiritual aspirant, look on your uncontrolled mind as your enemy. Do not come under its sway.”

So, through spiritual practice, if we bring the mind under the control of the intellect, it has the potential to become our best friend. However, the same mind has the potential of becoming our best friend, if we bring it under control of the intellect, through spiritual practice. The more powerful an entity is, the greater is the danger of its misuse, and also the greater is the scope for its utilization. Since the mind is such a powerful machine fitted into our bodies, it can work as a two-edged sword. Thus, those who slide to demoniac levels do so because of their own mind while those who attain sublime heights also do so because of their purified minds. Accordingly, Winston Churchill, the successful British Prime Minister during the Second World War, said: “The price of greatness is the responsibility over your every thought.” In this verse, Shree Krishna enlightens Arjun about the potential harm and benefits our mind can bestow upon us. In the following three verses, Shree Krishna describes the symptoms of one who is yog-ārūḍha (advanced in Yog).

jitātmanaḥ praśhāntasya paramātmā samāhitaḥ

śhītoṣhṇa-sukha-duḥkheṣhu tathā mānāpamānayoḥ

jita-ātmanaḥ—one who has conquered one’s mind; praśhāntasya—of the peaceful; parama-ātmā—God; samāhitaḥ—steadfast; śhīta—in cold; uṣhṇa—heat; sukha—happiness; duḥkheṣhu—and distress; tathā—also; māna—in honor; apamānayoḥ—and dishonor.

The yogis who have conquered the mind rise above the dualities of cold and heat, joy and sorrow, honor and dishonor. Such yogis remain peaceful and steadfast in their devotion to God.

Shree Krishna explained in verse 2.14 that the contact between the senses and the sense objects gives the mind the experience of heat and cold, joy and sorrow. As long as the mind has not been subdued, a person chases after the sensual perceptions of pleasure and recoils from the perceptions of pain. The yogi who conquers the mind is able to see these fleeting perceptions as the workings of the bodily senses, distinct from the immortal soul, and thus, remain unmoved by them. Such an advanced yogi rises above the dualities of heat and cold, joy and sorrow, etc.

There are only two realms in which the mind may dwell—one is the realm of Maya and the other is the realm of God. If the mind rises above the sensual dualities of the world, it can easily get absorbed in God. Thus, Shree Krishna has stated that an advanced yogi’s mind becomes situated in samādhi (deep meditation) upon God.

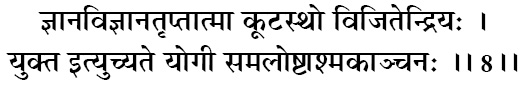

jñāna-vijñāna-tṛiptātmā kūṭa-stho vijitendriyaḥ

yukta ityuchyate yogī sama-loṣhṭāśhma-kāñchanaḥ

jñāna—knowledge; vijñāna—realized knowledge, wisom from within; tṛipta ātmā—one fully satisfied; kūṭa-sthaḥ—undistrubed; vijita-indriyaḥ—one who has conquered the senses; yuktaḥ—one who is in constant communion with the Supreme; iti—thus; uchyate—is said; yogī—a yogi; sama—looks equally; loṣhṭra—pebbles; aśhma—stone; kāñchanaḥ—gold.

The yogi who are satisfied by knowledge and discrimination, and have conquered their senses, remain undisturbed in all circumstances. They see everything—dirt, stones, and gold—as the same.

Jñāna, or knowledge, is the theoretical understanding obtained by listening to the Guru and from the study of the scriptures. Vijñāna is the realization of that knowledge as an internal awakening and wisdom from within. The intellect of the advanced yogi becomes illumined by both jñāna and vijñāna. Equipped with wisdom, the yogi sees all material objects as modifications of the material energy. Such a yogi does not differentiate between objects based on their attractiveness to the self. The enlightened yogi sees all things in their relationship with God. Since the material energy belongs to God, all things are meant for his service.

The word kuṭastha refers to one who distances the mind from the fluctuating perceptions of senses in contact with the material energy, neither seeking pleasurable situations nor avoiding unpleasurable ones. Vijitendriya is one who has subjugated the senses. The word yukt means one who is in constant communion with the Supreme. Such person begins tasting the divine bliss of God, and hence becomes a tṛiptātmā, or one fully satisfied by virtue of realized knowledge.

suhṛin-mitrāryudāsīna-madhyastha-dveṣhya-bandhuṣhu

sādhuṣhvapi cha pāpeṣhu sama-buddhir viśhiṣhyate

su-hṛit—toward the well-wishers; mitra—friends; ari—enemies; udāsīna—neutral persons; madhya-stha—mediators; dveṣhya—the envious; bandhuṣhu—relatives; sādhuṣhu—pious; api—as well as; cha—and; pāpeṣhu—the sinners; sama-buddhiḥ—of impartial intellect; viśhiṣhyate—is distinguished.

The yogis look upon all—well-wishers, friends, foes, the pious, and the sinners—with an impartial intellect. The yogi who is of equal intellect toward friend, companion, and foe, neutral among enemies and relatives, and impartial between the righteous and sinful, is considered to be distinguished among human.

It is the nature of the human mind to respond differently to friends and foes. But an elevated yogi’s nature is different. Endowed with realized knowledge of God, the elevated yogi see the whole creation in its unity with God. Thus, they are able to see all living beings with equality of vision. This parity of vision is also of various levels:

1. “All living beings are divine souls, and hence parts of God.” Thus, they are viewed as equal. ātmavat sarva bhūteṣhu yaḥ paśhyati sa paṇḍitaḥ “A true Pundit is one who sees everyone as the soul, and hence similar to oneself.”

2. Higher is the vision: “God is seated in everyone, and hence all are equally respect worthy.”

3. At the highest level, the yogi develops the vision: “Everyone is the form of God.” The Vedic scriptures repeatedly state that the whole world is a veritable form of God: īśhāvāsyam idam sarvaṁ yat kiñcha jagatyāṁ jagat (Īśhopaniṣhad 1) [v2] “The entire universe, with all its living and non-living beings is the manifestation of the Supreme Being, who dwells within it.” puruṣha evedaṁ sarvaṁ (Puruṣh Sūktam) [v3] “God is everywhere in this world, and everything is his energy.” Hence, the highest yogi sees everyone as the manifestation of God. Endowed with this level of vision, Hanuman says: sīyā rāma maya saba jaga jānī (Ramayan) [v4] “I see the face of Sita Ram in everyone.”

These categories have been further detailed in the commentary to verse 6.31. Referring to all three of the above categories, Shree Krishna says that the yogi who can maintain an equal vision toward all persons is even more elevated than the yogi mentioned in the previous verse. Having described the state of Yog, starting with the next verse, Shree Krishna describes the practice by which we can achieve that state.

yogī yuñjīta satatam ātmānaṁ rahasi sthitaḥ

ekākī yata-chittātmā nirāśhīr aparigrahaḥ

yogī—a yogi; yuñjīta—should remain enganged in meditation; satatam—constantly; ātmānam—self; rahasi—in seclusion; sthitaḥ—remaining; ekākī—alone; yata-chitta-ātmā—with a controlled mind and body; nirāśhīḥ—free from desires; aparigrahaḥ—free from desires for possessions for enjoyment.

Those who seek the state of Yog should reside in seclusion, constantly engaged in meditation with a controlled mind and body, getting rid of desires and possessions for enjoyment.

Having stated the characteristics of one who has attained the state of Yog, Shree Krishna now talks about the self-preparation required for it. Mastery in any field requires daily practice. An Olympic swimming champion is not one who goes to the local neighborhood swimming pool once a week on Saturday evenings. Only one who practices for several hours every day achieves the mastery required to win the Olympics. Practice is essential for spiritual mastery as well. Shree Krishna now explains the process of accomplishing spiritual mastery by recommending the daily practice of meditation. The first point he mentions is the need for a secluded place. All day long, we are usually surrounded by a worldly environment; these material activities, people, and conversations, all tend to make the mind more worldly. In order to elevate the mind toward God, we need to dedicate some time on a daily basis for secluded sādhanā.

The analogy of milk and water can help elucidate this point. If milk is poured into water, it cannot retain its undiluted identity, for water naturally mixes with it. However, if the milk is kept separate from water and converted into yogurt, and then the yogurt is churned to extract butter, the butter becomes immiscible. It can now challenge the water, “I will sit on your head and float; you can do nothing to me because I have become butter now.” Our mind is like the milk and the world is like water. In contact with the world, the mind gets affected by it and becomes worldly. However, an environment of seclusion, which offers minimal contact with the objects of the senses, becomes conducive for elevating the mind and focusing it upon God. Once sufficient attachment for God has been achieved, one can challenge the world, “I will live amidst all the dualities of Maya, but remain untouched by them.”

This instruction for seclusion has been repeated by Shree Krishna in verse 18.52: vivikt sevī laghvāśhī “Live in a secluded place; control your diet.” There is a beautiful way of practically applying this instruction without disturbing our professional and social works. In our daily schedule, we can allocate some time for sādhanā, or spiritual practice, where we isolate ourselves in a room that is free from worldly disturbances. Shutting ourselves out from the world, we should do sādhanā to purify the mind and solidify its focus upon God. If we practice in this manner for one to two hours every day, we will reap its benefits all through the day even while engaged in worldly activities. In this manner we will be able to retain the elevated state of consciousness that was gathered during the daily sādhanā in isolation from the world.

śhuchau deśhe pratiṣhṭhāpya sthiram āsanam ātmanaḥ

nātyuchchhritaṁ nāti-nīchaṁ chailājina-kuśhottaram

śhuchau—in a clean; deśhe—place; pratiṣhṭhāpya—having established; sthiram—steadfast; āsanam—seat; ātmanaḥ—his own; na—not; ati—too; uchchhritam—high; na—not; ati—too; nīcham—low; chaila—cloth; ajina—a deerskin; kuśha—kuśh grass; uttaram—one over ther other.

To practice Yog, one should make an āsan (seat) in a sanctified place, by placing kuśh grass, deer skin, and a cloth, one over the other. The āsan should be neither too high nor too low.

Shree Krishna explains in this verse the external practice for sādhanā. Śhuchau deśhe means a pure or sanctified place. In the initial stages, the external environment does impact the mind. In later stages of sādhanā, one is able to achieve internal purity even in dirty and unclean places. But for neophytes, clean surroundings help in keeping the mind clean as well. A mat of kuśh grass provides temperature insulation from the ground, akin to the yoga mats of today. The deer skin atop it deters poisonous pests like snakes and scorpions from approaching while one is absorbed in meditation. If the āsan is too high, there is the risk of falling off; if the āsan is too low, there is danger of disturbance from insects on the ground. Some instructions regarding external seating given in this verse may be somewhat anachronous to modern times, in which case the spirit of the instruction is to be absorbed in the thought of God, while the instructions for the internal practice remain the same.

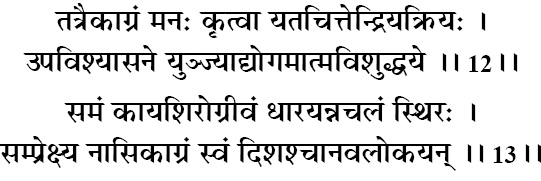

tatraikāgraṁ manaḥ kṛitvā yata-chittendriya-kriyaḥ

upaviśhyāsane yuñjyād yogam ātma-viśhuddhaye

samaṁ kāya-śhiro-grīvaṁ dhārayann achalaṁ sthiraḥ

samprekṣhya nāsikāgraṁ svaṁ diśhaśh chānavalokayan

tatra—there; eka-agram—one-pointed; manaḥ—mind; kṛitvā—having made; yata-chitta—controlling the mind; indriya—senses; kriyaḥ—activities; upaviśhya—being seated; āsane—on the seat; yuñjyāt yogam—should strive to practice yog; ātma viśhuddhaye—for purification of the mind; samam—straight; kāya—body; śhiraḥ—head; grīvam—neck; dhārayan—holding; achalam—unmoving; sthiraḥ—still; samprekṣhya—gazing; nāsika-agram—at the tip of the nose; svam—own; diśhaḥ—directions; cha—and; anavalokayan—not looking

Seated firmly on it, the yogi should strive to purify the mind by focusing it in meditation with one pointed concentration, controlling all thoughts and activities. He must hold the body, neck, and head firmly in a straight line, and gaze at the tip of the nose, without allowing the eyes to wander.

Having described the seating for meditation, Shree Krishna next describes the posture of the body that is best for concentrating the mind. In sādhanā, there is a tendency to become lazy and doze off to sleep. This happens because the material mind does not initially get as much bliss in contemplation on God as it does while relishing sense objects. This creates the possibility for the mind to become languid when focused on God. Hence, you do not find people dozing off half-way through their meal, but you do see people falling asleep during meditation and the chanting of God’s names. To avoid this, Shree Krishna gives the instruction to sit erect. The Brahma Sūtra also states three aphorisms regarding the posture for meditation:

āsīnaḥ saṁbhavāt (4.1.7) [v5] “To do sādhanā, seat yourself properly.”

achalatvaṁ chāpekṣhya (4.1.9)[v6] “Ensure that you sit erect and still.”

dhyānāchcha (4.1.8) [v7] “Seated in this manner, focus the mind in meditation.”

There are a number of meditative āsans described in the Hath Yoga Pradeepika, such as padmasan, ardha padmasan, dhyanveer asan, siddhasan, and sukhasan. We may adopt any āsan in which we can comfortably sit, without moving, during the period of the meditation. Maharshi Patañjali states:

sthira sukhamāsanam (Patañjali Yog Sūtra 2.46) [v8]

“To practice meditation, sit motionless in any posture that you are comfortable in.” Some people are unable to sit on the floor due to knee problems, etc. They should not feel discouraged, for they can even practice meditation while sitting on a chair, provided they fulfill the condition of sitting motionless and erect.

In this verse, Shree Krishna states that the eyes should be made to focus on the tip of the nose, and prevented from wandering. As a variation, the eyes can also be kept closed. Both these techniques will be helpful in blocking out worldly distractions.

The external seat and posture do need to be appropriate, but meditation is truly a journey within us. Through meditation, we can reach deep within and cleanse the mind of endless lifetimes of dross. By learning to hold the mind in concentration, we can work upon it to harness its latent potential. The practice of meditation helps organize our personality, awaken our inner consciousness, and expand our self-awareness. The spiritual benefits of meditation are described later, in the purport on verse 6.15. Some of the side benefits are:

- It reins the unbridled mind, and harnesses the thought energy to attain difficult goals.

- It helps maintain mental balance in the midst of adverse circumstances.

- It aids in the development of a strong resolve that is necessary for success in life.

- It enables one to eliminate bad sanskārs and habits, and cultivate good qualities.

The best kind of meditation is one where the mind is focused upon God. This is clarified in the next two verses.

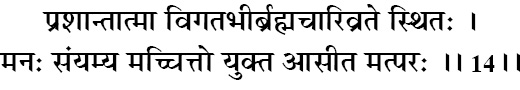

praśhāntātmā vigata-bhīr brahmachāri-vrate sthitaḥ

manaḥ sanyamya mach-chitto yukta āsīta mat-paraḥ

praśhānta—serene; ātmā—mind; vigata-bhīḥ—fearless; brahmachāri-vrate—in the vow of celibacy; sthitaḥ—situated; manaḥ—mind; sanyamya—having controlled; mat-chittaḥ—meditate on me (Shree Krishna); yuktaḥ—engaged; āsīta—should sit; mat-paraḥ—having me as the supreme goal.

Thus, with a serene, fearless, and unwavering mind, and staunch in the vow of celibacy, the vigilant yogi should meditate on me, having me alone as the supreme goal.

Shree Krishna emphasizes the practice of celibacy for success in meditation. The sexual desire facilitates the process of procreation in the animal kingdom, and animals indulge in it primarily for that purpose. In most species, there is a particular mating season; animals do not indulge in sexual activity wantonly. Since humans have greater intellects and the freedom to indulge at will, the activity of procreation is converted into a means of licentious enjoyment. However, the Vedic scriptures lay great emphasis on practicing celibacy. Maharshi Patanjali states: brahmacharyapratiṣhṭhāyāṁ vīrya lābhaḥ (Yog Sūtras 2.38) [v9] “The practice of celibacy leads to great enhancement of energy.”

Ayurveda, the Indian science of medicine extolls brahmacharya (the practice of celibacy) for its exceptional health benefits. One of the students of Dhanvantari approached his teacher after finishing his full course of Ayurveda (the ancient Indian science of medicine), and asked: “O Sage, now kindly let me know the secret of health.” Dhanvantari replied: “This seminal energy is verily the ātman. The secret of health lies in preservation of this vital force. He who wastes this vital and precious energy cannot have physical, mental, moral, and spiritual development.” According to Ayurveda, forty drops of blood go into making one drop of semen. Those who waste their semen develop unsteady and agitated prāṇ. They lose their physical and mental energy, and weaken their memory, mind, and intellect. The practice of celibacy leads to a boost of bodily energy, clarity of intellect, gigantic will power, retentive memory, and a keen spiritual intellect. It creates a sparkle in the eyes and a luster on the cheeks.

The definition of celibacy is not restricted to mere abstinence from physical indulgence. The Agni Purāṇ states that the eightfold activities related to sex must be controlled: 1) Thinking about it. 2) Talking about it. 3) Joking about it. 4) Envisioning it. 5) Desiring it. 6) Wooing to get someone interested in it. 7) Enticing someone interested in it. 8) Engaging in it. For one to be considered celibate, all these must be shunned. Thus, celibacy not only requires abstinence from sexual intercourse, but also refrainment from masturbation, homosexual acts, and all other sexual practices.

Further, Shree Krishna states here that the object of meditation should be God alone. This point is again reiterated in the next verse.

yuñjann evaṁ sadātmānaṁ yogī niyata-mānasaḥ

śhantiṁ nirvāṇa-paramāṁ mat-sansthām adhigachchhati

yuñjan—keeping the mind absorbed in God; evam—thus; sadā—constantly; ātmānam—the mind; yogī—a yogi; niyata-mānasaḥ—one with a disciplined mind; śhāntim—peace; nirvāṇa—liberation from the material bondage; paramām—supreme; mat-sansthām—abides in me; adhigachchhati—attains.

Thus, constantly keeping the mind absorbed in me, the yogi of disciplined mind attains nirvāṇ, and abides in me in supreme peace.

Varieties of techniques for meditation exist in the world. There are Zen techniques, Buddhist techniques, Tantric techniques, Taoist techniques, Vedic techniques, and so on. Each of these has many sub-branches. Amongst the followers of Hinduism itself, there are innumerable techniques being practiced. Which of these should we adopt for our personal practice? Shree Krishna makes this riddle easy to solve. He states that the object of meditation should be God himself and God alone.

The aim of meditation is not merely to enhance concentration and focus, but also to purify the mind. Meditating on the breath, chakras, void, flame, etc. is helpful in developing focus. However, the purification of the mind is only possible when we fix it upon an all-pure object, which is God himself. Hence, verse 14.26 states that God is beyond the three modes of material nature, and when one fixes the mind upon him, it too rises above the three modes. Thus, meditating upon the prāṇas may be called transcendental by its practitioners, but true transcendental meditation is upon God alone.

Now what is the way of fixing the mind upon God? We can make all of God’s divine attributes—names, forms, virtues, pastimes, abodes, associates—the objects of meditation. They are all non-different from God and replete with all his energies. Hence, devotees may meditate upon any of these and get the true benefit of meditating upon God. In the various bhakti traditions in India, the name of God is made the basis of contemplation. Thus, the Ramayan states:

brahma rām teṅ nāmu baṛa, bara dāyaka bara dāni [v10]

“God’s name is bigger than God himself, in terms of its utility to the souls.” Taking the name is a very convenient way of remembering God, since it can be taken anywhere and everywhere—while walking, talking, sitting, eating, etc.

However, for most sādhaks the name by itself is not sufficiently attractive for enchanting the mind. Due to sanskārs of endless lifetimes, the mind is naturally drawn to forms. Using the form of God as the basis, meditation becomes natural and easy. This is called rūp dhyān meditation.

Once the mind is focused upon the form of God, we can then further enhance it by contemplating upon the virtues of God—his compassion, his beauty, his knowledge, his love, his benevolence, his grace, and so on. One can then advance in meditation by serving God in the mind. We can visualize ourselves offering foodstuffs to him, worshipping him, singing to him, massaging him, fanning him, bathing him, cooking for him, etc. This is called mānasī sevā (serving God in the mind). In this way, we can meditate upon the names, forms, virtues, pastimes, etc. of God. All these become powerful means of fulfilling Shree Krishna’s instruction to Arjun, in this verse, to keep the mind absorbed in him.

At the end of the verse, Shree Krishna gives the ultimate benefits of meditation, which are liberation from Maya and the everlasting beatitude of God-realization.

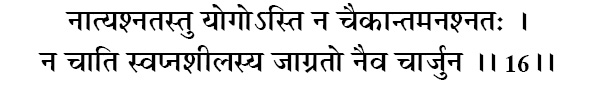

nātyaśhnatastu yogo ’sti na chaikāntam anaśhnataḥ

na chāti-svapna-śhīlasya jāgrato naiva chārjuna

na—not; ati—too much; aśhnataḥ—of one who eats; tu—however; yogaḥ—Yog; asti—there is; na—not; cha—and; ekāntam—at all; anaśhnataḥ—abstaining from eating; na—not; cha—and; ati—too much; svapna-śhīlasya—of one who sleeps; jāgrataḥ—of one who does not sleep enough; na—not; eva—certainly; cha—and; arjuna—Arjun.

O Arjun, those who eat too much or eat too little, sleep too much or too little, cannot attain success in Yog.

After describing the object of meditation and the end-goal achieved by it, Shree Krishna gives some regulations to follow. He states that those who break the rules of bodily maintenance cannot be successful in Yog. Often beginners on the path, with their incomplete wisdom state: “You are the soul and not this body. So simply engage in spiritual activity, forgetting about the maintenance of the body.”

However, such a philosophy cannot get one too far. It is true that we are not the body, yet the body is our carrier as long as we live, and we are obliged to take care of it. The Ayurvedic text, Charak Samhitā states: śharīra mādhyaṁ khalu dharma sādhanam [v11] “The body is the vehicle for engaging in religious activity.” If the body becomes unwell, then spiritual pursuits get impeded too. The Ramayan states: tanu binu bhajana veda nahiṅ varanā [v12] “The Vedas do not recommend that we ignore the body, while engaging in spirituality.” In fact, they instruct us to take good care of our body with the help of material science. The Īśhopaniṣhad states:

andhaṁ tamaḥ praviśhanti ye ’vidyām upāsate

tato bhūya iva te tamo ya u vidyāyām ratāḥ (9) [v13]

“Those who cultivate only material science go to hell. But those who cultivate only spiritual science go to an even darker hell.” Material science is necessary for the maintenance of our body, while spiritual science is necessary for the manifestation of the internal divinity within us. We must balance both in our lives to reach the goal of life. Hence, yogāsans, prāṇāyām, and the science of proper diet are an essential part of Vedic knowledge. Each of the four Vedas has its associate Veda for material knowledge. The associate Veda of Atharva Veda is Ayurveda, which is the hoary science of medicine and good health. This demonstrates that the Vedas lay emphasis on the maintenance of physical health. Accordingly, Shree Krishna says that overeating or not eating at all, extreme activity or complete inactivity, etc. are all impediments to Yog. Spiritual practitioners should take good care of their body, by eating fresh nutritious food, doing daily exercise, and getting the right amount of sleep every night.

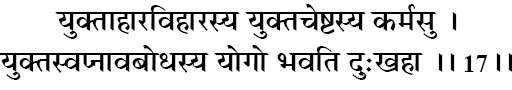

yuktāhāra-vihārasya yukta-cheṣhṭasya karmasu

yukta-svapnāvabodhasya yogo bhavati duḥkha-hā

yukta—moderate; āhāra—eating; vihārasya—recreation; yukta cheṣhṭasya karmasu —balanced in work; yukta—regulated; svapna-avabodhasya—sleep and wakefulness; yogaḥ—Yog; bhavati—becomes; duḥkha-hā—the slayer of sorrows.

But those who are temperate in eating and recreation, balanced in work, and regulated in sleep, can mitigate all sorrows by practicing Yog.

Yog is the union of the soul with God. The opposite of Yog is bhog, which means engagement in sensual pleasures. Indulgence in bhog violates the natural laws of the body, and results in rog (disease). As stated in the previous verse, if the body becomes diseased, it impedes the practice of Yog. Thus in this verse, Shree Krishna states that by being temperate in bodily activities and practicing Yog, we can become free from the sorrows of the body and mind.

The same instruction was repeated two-and-a-half millennium after Shree Krishna by Gautam Buddha, when he recommended the golden middle path between severe asceticism and sensual indulgence. There is a beautiful story regarding this. It is said that before gaining enlightenment, Gautam Buddha once gave up eating and drinking, and sat in meditation. However, after a few days of practicing in this manner, the lack of nourishment made him weak and dizzy, and he found it impossible to steady his mind in meditation. At that time, some village women happened to be passing by. They were carrying water pots on their heads that they had filled from the river nearby, and were singing a song. The words of the song were: “Tighten the strings of the tānpurā (a stringed Indian musical instrument, resembling a guitar). But do not tighten them so much that the strings break.” Their words entered the ears of Gautam Buddha, and he exclaimed, “These illiterate village women are singing such words of wisdom. They contain a message for us humans. We too should tighten our bodies (practice austerities), but not to the extent that the body is destroyed.”

Benjamin Franklin (1706 – 1790), a founding father of the United States, is highly regarded as a self-made man. In an effort to grow his character, starting at the age of 20, he maintained a diary in which he tracked his performance related to the 13 activities he wanted to grow in. The first activity was “Temperance: Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation.”

yadā viniyataṁ chittam ātmanyevāvatiṣhṭhate

niḥspṛihaḥ sarva-kāmebhyo yukta ityuchyate tadā

yadā—when; viniyatam—fully controlled; chittam—the mind; ātmani—of the self; eva—certainly; avatiṣhṭhate—stays; nispṛihaḥ—free from cravings: sarva—all; kāmebhyaḥ—for yearning of the senses; yuktaḥ—situated in perfect Yog; iti—thus; uchyate—is said; tadā—then.

With thorough discipline, they learn to withdraw the mind from selfish cravings and rivet it on the unsurpassable good of the self. Such persons are said to be in Yog, and are free from all yearning of the senses.

When does a person complete the practice of Yog? The answer is when the controlled chitta (mind) becomes fixed and focused exclusively on God. It is then simultaneously and automatically weaned away from all cravings of the senses and desires for worldly enjoyment. At that time one can be considered as yukt, or having perfect Yog. At the end of this very chapter, he also states: “Of all yogis, those whose minds are always absorbed in me, and who engage in devotion to me with great faith, I consider them to be the highest of all.” (Verse 6.47)

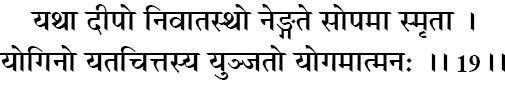

yathā dīpo nivāta-stho neṅgate sopamā smṛitā

yogino yata-chittasya yuñjato yogam ātmanaḥ

yathā—as; dīpaḥ—a lamp; nivāta-sthaḥ—in a windless place; na—does not; iṅgate—flickers; sā—this; upamā—analogy; smṛitā—is considered; yoginaḥ—of a yogi; yata-chittasya—whose mind is disciplined; yuñjataḥ—steadily practicing; yogam—in meditation; ātmanaḥ—on the Supreme.

Just as a lamp in a windless place does not flicker, so the disciplined mind of a yogi remains steady in meditation on the self.

In this verse, Shree Krishna gives the simile of the flame of a lamp. In the wind, the flame flickers naturally and is impossible to control. However, in a windless place, the flame becomes as steady as a picture. Similarly, the mind is fickle by nature and very difficult to control. But when the mind of a yogi is in enthralled union with God, it becomes sheltered against the winds of desire. Such a yogi holds the mind steadily under control by the power of devotion.

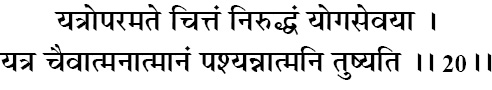

yatroparamate chittaṁ niruddhaṁ yoga-sevayā

yatra chaivātmanātmānaṁ paśhyann ātmani tuṣhyati

yatra—when; uparamate—rejoice inner joy; chittam—the mind; niruddham—restrained; yoga-sevayā—by the practice of yog; yatra—when; cha—and; eva—certainly; ātmanā—through the purified mind; ātmānam—the soul; paśhyan—behold; ātmani—in the self; tuṣhyati—is satisfied.

When the mind, restrained from material activities, becomes still by the practice of Yog, then the yogi is able to behold the soul through the purified mind, and he rejoices in the inner joy.

Having presented the process of meditation and the state of its perfection, Shree Krishna now reveals the results of such endeavors. When the mind is purified, one is able to perceive the self as distinct from the body, mind, and intellect. For example, if there is muddy water in a glass, we cannot see through it. However, if we put alum in the water, the mud settles down and the water becomes clear. Similarly, when the mind is unclean, it obscures perception of the soul and any acquired scriptural knowledge of the ātmā is only at the theoretical level. But when the mind becomes pure, the soul is directly perceived through realization.

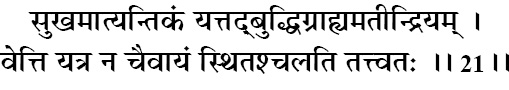

sukham ātyantikaṁ yat tad buddhi-grāhyam atīndriyam

vetti yatra na chaivāyaṁ sthitaśh chalati tattvataḥ

sukham—happiness; ātyantikam—limitless; yat—which; tat—that; buddhi—by intellect; grāhyam—grasp; atīndriyam—transcending the senses; vetti—knows; yatra—wherein; na—never; cha—and; eva—certainly; ayam—he; sthitaḥ—situated; chalati—deviates; tattvataḥ—from the Eternal Truth.

In that joyous state of Yog, called samādhi, one experiences supreme boundless divine bliss, and thus situated, one never deviates from the Eternal Truth.

The yearning for bliss is intrinsic to the nature of the soul. It stems from the fact that we are tiny parts of God, who is an ocean of bliss. A number of quotations from the Vedic scriptures establishing this were mentioned in verse 5.21. Here are some more quotations expressing the nature of God as having an infinite ocean of bliss:

raso vai saḥ rasaṁ hyevāyaṁ labdhvā nandī bhavati

(Taittirīya Upaniṣhad 2.7) [v14]

“God is bliss himself; the individual soul becomes blissful on attaining him.”

ānandamayo ’bhyāsāt (Brahma Sūtra 1.1.12) [v15]

“God is the veritable form of bliss.”

satya jñānānantānanda mātraika rasa mūrtayaḥ

(Bhāgavatam 10.13.54) [v16]

“The divine form of God is made of eternity, knowledge, and bliss.”

ānanda sindhu madhya tava vāsā, binu jāne kata marasi piyāsā

(Ramayan) [v17]

“God, who is the ocean of bliss, is seated within you. Without knowing him, how can your thirst for happiness be satiated?”

We have been seeking perfect bliss for eons, and everything we do is in search of that bliss. However, from the objects of gratification, the mind and senses perceive only a shadowy reflection of true bliss. This sensual gratification fails to satisfy the longing of the soul within, which yearns for the infinite bliss of God.

When the mind is in union with God, the soul experiences the ineffable and sublime bliss beyond the scope of the senses. This state is called samādhi in the Vedic scriptures. The Sage Patanjali states: samādhisiddhirīśhvara praṇidhānāt (Patañjali Yog Darśhan 2.45) [v18] “For success in samādhi, surrender to the Supreme Lord.” In the state of samādhi, experiencing complete satisfaction and contentment, the soul has nothing left to desire, and thus becomes firmly situated in the Absolute Truth, without deviating from it for even a moment.

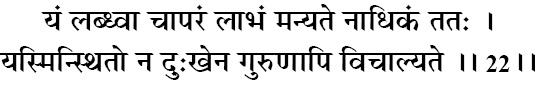

yaṁ labdhvā chāparaṁ lābhaṁ manyate nādhikaṁ tataḥ

yasmin sthito na duḥkhena guruṇāpi vichālyate

yam—which; labdhvā—having gained; cha—and; aparam—any other; lābham—gain; manyate—considers; na—not; adhikam—greater; tataḥ—than that; yasmin—in which; sthitaḥ—being situated; na—never; duḥkhena—by sorrow; guruṇā—(by) the greatest; api—even; vichālyate—is shaken.

Having gained that state, one does not consider any attainment to be greater. Being thus established, one is not shaken even in the midst of the greatest calamity.

In the material realm, no extent of attainment satiates a person totally. A poor person strives hard to become rich, and feels satisfied if he or she is able to become a millionaire. But when that same millionaire looks at a billionaire, discontentment sets in again. The billionaire is also discontented by looking at an even richer person. No matter what happiness we get, when we perceive a higher state of happiness, the feeling of unfulfillment lingers. But happiness achieved from the state of Yog is the infinite bliss of God. Since there is nothing higher than that, on experiencing that infinite bliss, the soul naturally perceives that it has reached its goal.

God’s divine bliss is also eternal, and it can never be snatched away from the yogi who has attained it once. Such a God-realized soul, though residing in the material body, remains in the state of divine consciousness. Sometimes, externally, it seems that the Saint is facing tribulations in the form of illness, antagonistic people, and oppressive environment, but internally the Saint retains divine consciousness and continues to relish the bliss of God. Thus, even the biggest difficulty cannot shake such a Saint. Established in union with God, the Saint rises above bodily consciousness and is thus not affected by bodily harm. Accordingly, we hear from the Puranas how Prahlad was put in a pit of snakes, tortured with weapons, placed in the fire, thrown off a cliff, etc. but none of these difficulties could break Prahlad’s devotional union with God.

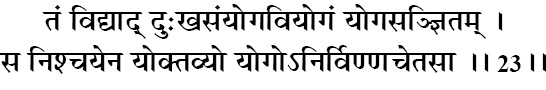

taṁ vidyād duḥkha-sanyoga-viyogaṁ yogasaṅjñitam

sa niśhchayena yoktavyo yogo ’nirviṇṇa-chetasā

tam—that; vidyāt—you shout know; duḥkha-sanyoga-viyogam—state of severance from union with misery; yoga-saṁjñitam—is known as yog; saḥ—that; niśhchayena—resolutely; yoktavyaḥ—should be practiced; yogaḥ—yog; anirviṇṇa-chetasā—with an undeviating mind.

That state of severance from union with misery is known as Yog. This Yog should be resolutely practiced with determination free from pessimism.

The material world is the realm of Maya, and it has been termed by Shree Krishna in verse 8.15 as duḥkhālayam aśhāśhvatam, or temporary and full of misery. Thus, the material energy Maya is compared to darkness. It has put us in the darkness of ignorance and is making us suffer in the world. However, the darkness of Maya naturally gets dispelled when we bring the light of God into our heart. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu states this very beautifully:

kṛiṣhṇa sūrya-sama, māyā haya andhakāra

yāhāñ kṛiṣhṇa, tāhāṅ nāhi māyāra adhikāra

(Chaitanya Charitāmṛit, Madhya Leela, 22.31) [v19]

“God is like the light and Maya is like darkness. Just as darkness does not have the power to engulf light, similarly Maya can never overcome God.” Now, the nature of God is divine bliss while the consequence of Maya is misery. Thus, one who attains the divine bliss of God can never be overcome by the misery of Maya again.

Thus, the state of Yog implies both 1) attainment of bliss, and 2) freedom from misery. Shree Krishna emphasizes both successively. In the previous verse, the attainment of bliss was highlighted as the result of Yog; in this verse, freedom from misery is being emphasized.

In the second line of this verse Shree Krishna states that the stage of perfection has to be reached through determined practice. He then goes on to explain how we must practice meditation.

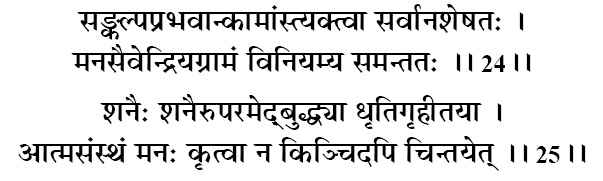

saṅkalpa-prabhavān kāmāns tyaktvā sarvān aśheṣhataḥ

manasaivendriya-grāmaṁ viniyamya samantataḥ

śhanaiḥ śhanair uparamed buddhyā dhṛiti-gṛihītayā

ātma-sansthaṁ manaḥ kṛitvā na kiñchid api chintayet

saṅkalpa—a resolve; prabhavān—born of; kāmān—desires; tyaktvā—having abandoned; sarvān—all; aśheṣhataḥ—completely; manasā—through the mind; eva—certainly; indriya-grāmam—the group of senses; viniyamya—restraining; samantataḥ—from all sides; śhanaiḥ—gradually; śhanaiḥ—gradually; uparamet—attain peace; buddhyā—by intellect; dhṛiti-gṛihītayā—achieved through determination of resolve that is in accordance with scriptures; ātma-sanstham—fixed in God; manaḥ—mind; kṛitvā—having made; na—not; kiñchit—anything; api—even; chintayet—should think of.

Completely renouncing all desires arising from thoughts of the world, one should restrain the senses from all sides with the mind. Slowly and steadily, with conviction in the intellect, the mind will become fixed in God alone, and will think of nothing else.

Meditation requires the dual process of removing the mind from the world and fixing it on God. Here, Shree Krishna begins by describing the first part of the process—taking the mind away from the world.

Thoughts of worldly things, people, events, etc. come to the mind when it is attached to the world. Initially, the thoughts are in the form of sphurṇā (flashes of feelings and ideas). When we insist on the implementation of sphurṇā, it becomes saṅkalp. Thus, thoughts lead to saṅkalp (pursuit of these objects) and vikalp (revulsion from them), depending upon whether the attachment is positive or negative. The seed of pursuit and revulsion grows into the plant of desire, “This should happen. This should not happen.” Both saṅkalp and vikalp immediately create impressions on the mind, like the film of a camera exposed to the light. Thus, they directly impede meditation upon God. They also have a natural tendency to flare up, and a desire that is a seed today can become an inferno tomorrow. Thus, one who desires success in meditation should renounce the affinity for material objects.

Having described the first part of the process of meditation—removing the mind from the world—Shree Krishna then talks of the second part. The mind should be made to reside upon God. He says this will not happen automatically, but with determined effort, success will come slowly.

Determination of resolve that is in accordance with the scriptures is called dhṛiti. This determination comes with conviction of the intellect. Many people acquire academic knowledge of the scriptures about the nature of the self and the futility of worldly pursuits. But their daily life is at variance with their knowledge, and they are seen to indulge in sin, sex, and intoxication. This happens because their intellect is not convinced about that knowledge. The power of discrimination comes with the conviction of the intellect about the impermanence of the world and the eternality of one’s relationship with God. Thus utilizing the intellect, one must gradually cease sensual indulgence. This is called pratyāhār, or control of the mind and senses from running toward the objects of the senses. Success in pratyāhār will not come immediately. It will be achieved through gradual and repeated exercise. Shree Krishna explains next what that exercise involves.

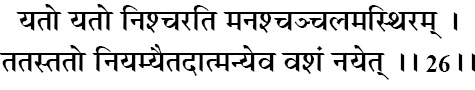

yato yato niśhcharati manaśh chañchalam asthiram

tatas tato niyamyaitad ātmanyeva vaśhaṁ nayet

yataḥ yataḥ—whenever and wherever; niśhchalati—wanders; manaḥ—the mind; chañchalam—restless; asthiram—unsteady; tataḥ tataḥ—from there; niyamya—having restrained; etat—this; ātmani—on God; eva—certainly; vaśham—control; nayet—should bring.

Whenever and wherever the restless and unsteady mind wanders, one should bring it back and continually focus it on God.

Success in meditation is not achieved in a day; the path to perfection is long and arduous. When we sit for meditation with the resolve to focus our mind upon God, we will find that ever so often it wanders off in worldly saṅkalp and vikalp. It is thus important to understand the three steps involved in the process of meditation:

1. With the intellect’s power of discrimination we decide that the world is not our goal. Hence, we forcefully remove the mind from the world. This requires effort.

2. Again, with the power of discrimination we understand that God alone is ours, and God-realization is our goal. Hence, we bring the mind to focus upon God. This also requires effort.

3. The mind comes away from God, and wanders back into the world. This does not require effort, it happens automatically.

When the third step happens by itself, sādhaks often become disappointed, “I tried so hard to focus upon God, but the mind went back into the world.” Shree Krishna asks us not to feel disappointed. He says the mind is fickle and we should be prepared that it will wander off in the direction of its infatuation, despite our best efforts to control it. However, when it does wander off, we should once again repeat steps 1 and 2—take the mind away from the world and bring it back to God. Once again, we will experience that step 3 takes place by itself. We should not lose heart, and again repeat steps 1 and 2.

We will have to do this repeatedly. Then slowly, the mind’s attachment toward God will start increasing. And simultaneously, its detachment from the world will also increase. As this happens, it will become easier and easier to meditate. But in the beginning, we must be prepared for the battle involved in disciplining the mind.

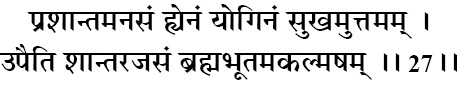

praśhānta-manasaṁ hyenaṁ yoginaṁ sukham uttamam

upaiti śhānta-rajasaṁ brahma-bhūtam akalmaṣham

praśhānta—peaceful; manasam—mind; hi—certainly; enam—this; yoginam—yogi; sukham uttamam—the highest bliss; upaiti—attains; śhānta-rajasam—whose passions are subdued; brahma-bhūtam—endowed with God-realization; akalmaṣham—without sin.

Great transcendental happiness comes to the yogi whose mind is calm, whose passions are subdued, who is without sin, and who sees everything in connection with God.

As a yogi perfects the practice of withdrawing the mind from sense objects and securing it upon God, the passions get subdued and the mind becomes utterly serene. Earlier, effort was required to focus it upon God, but now it naturally runs to him. At this stage, the elevated meditator sees everything in its connection with God. Sage Narad states:

tat prāpya tad evāvalokayati tad eva śhṛiṇoti

tad eva bhāṣhayati tad eva chintayati

(Nārad Bhakti Darśhan, Sūtra 55) [v20]

“The consciousness of the devotee whose mind is united in love with God is always absorbed in him. Such a devotee always sees him, hears him, speaks of him, and thinks of him.” When the mind gets absorbed in God in this manner, the soul begins to experience a glimpse of the infinite bliss of God who is seated within.

Sādhaks often ask how they can know that they are progressing. The answer is embedded in this verse. When we find our inner transcendental bliss increasing, we can consider it as a symptom that our mind is coming under control and the consciousness is getting spiritually elevated. Here, Shree Krishna says that when we are śhānta-rajasaṁ (free from passion) and akalmaṣham (sinless), then we will become brahma-bhūtam (endowed with God-realization). At that stage, we will experience sukham uttamam (the highest bliss).

yuñjann evaṁ sadātmānaṁ yogī vigata-kalmaṣhaḥ

sukhena brahma-sansparśham atyantaṁ sukham aśhnute

yuñjan—uniting (the self with God); evam—thus; sadā—always; ātmānam—the self; yogī—a yogi; vigata—freed from; kalmaṣhaḥ—sins; sukhena—easily; brahma-sansparśham—constantly in touch with the Supreme; atyantam—the highest; sukham—bliss; aśhnute—attains.

The self-controlled yogi, thus uniting the self with God, becomes free from material contamination, and being in constant touch with the Supreme, achieves the highest state of perfect happiness.

Happiness can be classified into four categories:

sāttvikaṁ sukhamātmotthaṁ viṣhayotthaṁ tu rājasam

tāmasaṁ moha dainyotthaṁ nirguṇaṁ madapāśhrayām

(Bhāgavatam 11.25.29) [v21]

1. Tāmasic happiness. This is the pleasure derived from narcotics, alcohol, cigarettes, meat products, violence, sleep, etc.

2. Rājasic happiness. This is the pleasure from the gratification of the five senses and the mind.

3. Sāttvic happiness. This is the pleasure experienced through practicing virtues, such as compassion, service to others, cultivation of knowledge, stilling of the mind, etc. It includes the bliss of self-realization experienced by the jñānīs when they stabilize the mind upon the soul.

4. Nirguṇa happiness. This is the divine bliss of God, which is infinite in extent. Shree Krishna explains that the yogi who becomes free from material contamination and becomes united with God attains this highest state of perfect happiness. He has called this unlimited bliss in verse 5.21 and supreme bliss in verse 6.21.

sarva-bhūta-stham ātmānaṁ sarva-bhūtāni chātmani

īkṣhate yoga-yuktātmā sarvatra sama-darśhanaḥ

sarva-bhūta-stham—situated in all living beings; ātmānam—Supreme Soul; sarva—all; bhūtāni—living beings; cha—and; ātmani—in God; īkṣhate—sees; yoga-yukta-ātmā—one united in consciousness with God; sarvatra—everywhere; sama-darśhanaḥ—equal vision.

The true yogis, uniting their consciousness with God, see with equal eye, all living beings in God and God in all living beings.

During the festival of Diwali in India, shops sell sugar candy molded in various forms, as cars, airplanes, men, women, animals, balls, caps, etc. Children fight with their parents that they want a car, elephant, and so on. The parents smile at their innocuousness, thinking that they are all made from the same sugar ingredient, and are all equally sweet.

Similarly, the ingredient of everything that exists is God himself, in the form of his various energies.

eka deśhasthitasyāgnirjyotsnā vistāriṇī yathā

parasya brahmaṇaḥ śhaktistathedamakhilaṁ jagat (Nārad Pañcharātra) [v22]

“Just as the sun, while remaining in one place, spreads its light everywhere, similarly the Supreme Lord, by his various energies pervades and sustains everything that exists.” The perfected yogis, in the light of realized knowledge, see everything in its connection with God.

yo māṁ paśhyati sarvatra sarvaṁ cha mayi paśhyati

tasyāhaṁ na praṇaśhyāmi sa cha me na praṇaśhyati

yaḥ—who; mām—me; paśhyati—see; sarvatra—everywhere; sarvam—everything; cha—and; mayi—in me; paśhyati—see; tasya—for him; aham—I; na—not; praṇaśhyāmi—lost; saḥ—that person; cha—and; me—to me; na—nor; praṇaśhyati—lost.

For those who see me everywhere and see all things in me, I am never lost, nor are they ever lost to me.

To lose God means to let the mind wander away from him, and to be with him means to unite the mind with him. The easy way to unite the mind with God is to learn to see everything in its connection with him. For example, let us say that someone hurts us. It is the nature of the mind to develop sentiments of resentment, hatred, etc. toward anyone who harms us. However, if we permit that to happen, then our mind comes away from the divine realm, and the devotional union of our mind with God ceases. Instead, if we see the Supreme Lord seated in that person, we will think, “God is testing me through this person. He wants me to increase the virtue of tolerance, and that is why he is inspiring this person to behave badly with me. But I will not permit the incident to disturb me.” Thinking in this way, we will be able to prevent the mind from becoming a victim of negative sentiments.

Similarly, the mind separates from God when it gets attached to a friend or relative. Now, if we train the mind to see God in that person, then each time the mind wanders toward him or her, we will think, “Shree Krishna is seated in this person, and thus I am feeling this attraction.” In this manner, the mind will continue to retain its devotional absorption in the Supreme.

Sometimes, the mind laments over past incidents. This again separates the mind from the divine realm because lamentation takes the mind into the past and the present contemplation of God and Guru ceases. Now if we see that incident in connection with God, we will think, “The Lord deliberately arranged for me to experience tribulation in the world, so that I may develop detachment. He is so concerned about my welfare that he mercifully arranges for the proper circumstances that are beneficial for my spiritual progress.” By thinking thus, we will be able to protect our devotional focus. Sage Narad states:

loka hānau chintā na kāryā niveditātma loka vedatvāt

(Nārad Bhakti Darshan, Sūtra 61) [v23]

“When you suffer a reversal in the world, do not lament or brood over it. See the grace of God in that incident.” Our self-interest lies in somehow or the other keeping the mind in God, and the simple trick to accomplish this is to see God in everything and everyone. That is the practice stage, which slowly leads to the perfection that is mentioned in this verse, where we are never lost to God and he is never lost to us.

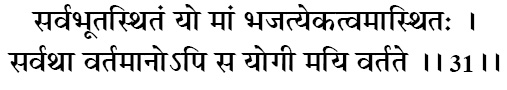

sarva-bhūta-sthitaṁ yo māṁ bhajatyekatvam āsthitaḥ

sarvathā vartamāno ’pi sa yogī mayi vartate

sarva-bhūta-sthitam—situated in all beings; yaḥ—who; mām—me; bhajati—worships; ekatvam—in unity; āsthitaḥ—established; sarvathā—in all kinds of; varta-mānaḥ—remain; api—although; saḥ—he; yogī—a yogi; mayi—in me; vartate—dwells.

The yogi who is established in union with me, and worships me as the Supreme Soul residing in all beings, dwells only in me, though engaged in all kinds of activities.

God is all-pervading in the world. He is also seated in everyone’s heart as the Supreme Soul. In verse 18.61, Shree Krishna states: “I am situated in the hearts of all living beings.” Thus, within the body of each living being, there are two personalities—the soul and the Supreme Soul.

1. Those in material consciousness see everyone as the body, and make distinctions on the basis of caste, creed, sex, age, social status, etc.

2. Those in superior consciousness see everyone as the soul. Thus in verse 5.18, Shree Krishna states: “The learned, with the eyes of divine knowledge, see with equal vision a Brahmin, a cow, an elephant, a dog, and a dog-eater.”

3. The elevated yogis in even higher consciousness see God seated as the Supreme Soul in everyone. They also perceive the world, but they are unconcerned about it. They are like the hansas, the swans who can drink the milk and leave out the water from a mixture of milk and water.

4. The most elevated yogis are called paramahansas. They only see God, and have no perception of the world. This was the level of realization of Shukadev, the son of Ved Vyas, as stated in the Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam:

yaṁ pravrajantam anupetam apeta kṛityaṁ

dvaipāyano viraha-kātara ājuhāva

putreti tan-mayatayā taravo ’bhinedustaṁ

sarva-bhūta-hṛidayaṁ munim ānato ’smi (1.2.2) [v24]

When Shukadev entered the renounced order of sanyās, walking away from home in his childhood itself, he was at such an elevated level that he had no perception of the world. He did not even notice the beautiful women bathing in the nude in a lake, while he happened to pass by there. All that he perceived was God; all that he heard was God; all that he thought was God.

In this verse, Shree Krishna is talking about the perfected yogis who are in the third and fourth stages of the above levels of realization.

ātmaupamyena sarvatra samaṁ paśhyati yo ’rjuna

sukhaṁ vā yadi vā duḥkhaṁ sa yogī paramo mataḥ

ātma-aupamyena—similar to oneself; sarvatra—everywhere; samam—equally; paśhyati—see; yaḥ—who; arjuna—Arjun; sukham—joy; vā—or; yadi—if; vā—or; duḥkham—sorrow; saḥ—such; yogī—a yogi; paramaḥ—highest; mataḥ—is considered.

I regard them to be perfect yogis who see the true equality of all living beings and respond to the joys and sorrows of others as if they were their own.

We consider all the limbs of our body as ours, and are equally concerned if any of them is damaged. We are incontrovertible in the conviction that the harm done to any of our limbs is harm done to ourselves. Similarly, those who see God in all beings consider the joys and sorrows of others as their own. Therefore, such yogis are always the well-wishers of all souls and they strive for the eternal benefit of all. This is the sama-darśhana (equality of vision) of perfected yogis.

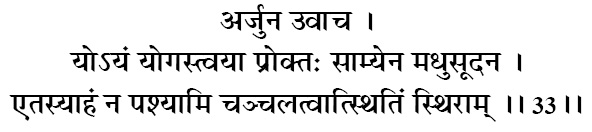

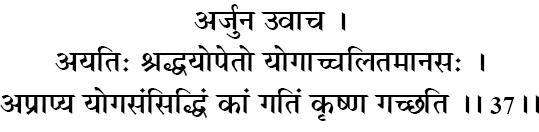

arjuna uvācha

yo ’yaṁ yogas tvayā proktaḥ sāmyena madhusūdana

etasyāhaṁ na paśhyāmi chañchalatvāt sthitiṁ sthirām

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; yaḥ—which; ayam—this; yogaḥ—system of Yog; tvayā—by you; proktaḥ—described; sāmyena—by equanimity; madhu-sūdana—Shree Krishna, the killer of the demon named Madhu; etasya—of this; aham—I; na—do not; paśhyāmi—see; chañchalatvāt—due to restlessness; sthitim—situation; sthirām—steady.

Arjun said: The system of Yog that you have described, O Madhusudan, appears impractical and unattainable to me, due to the restless mind.

Arjun speaks this verse, beginning with the words yo yam, “This system of Yog,” referring to the process described from verse 6.10 forward. Shree Krishna has just finished explaining that for perfection in Yog we must:

— subdue the senses

— give up all desires

— focus the mind upon God alone

— think of him with an unwavering mind

— see everyone with equal vision

Arjun frankly expresses his reservation about what he has heard by saying that it is impracticable. None of the above can be accomplished without controlling the mind. If the mind is restless, then all these aspects of Yog become unattainable as well.

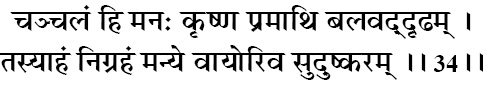

chañchalaṁ hi manaḥ kṛiṣhṇa pramāthi balavad dṛiḍham

tasyāhaṁ nigrahaṁ manye vāyor iva su-duṣhkaram

chañchalam—restless; hi—certainly; manaḥ—mind; kṛiṣhṇa—Shree Krishna; pramāthi—turbulent; bala-vat—strong; dṛiḍham—obstinate; tasya—its; aham—I; nigraham—control; manye—think; vāyoḥ—of the wind; iva—like; su-duṣhkaram—difficult to perform.

The mind is very restless, turbulent, strong and obstinate, O Krishna. It appears to me that it is more difficult to control than the wind.

Arjun speaks for us all when he describes the troublesome mind. It is restless because it keeps flitting in different directions, from subject to subject. It is turbulent because it creates upheavals in one’s consciousness, in the form of hatred, anger, lust, greed, envy, anxiety, fear, attachment, etc. It is strong because it overpowers the intellect with its vigorous currents and destroys the faculty of discrimination. The mind is also obstinate because when it catches a harmful thought, it refuses to let go, and continues to ruminate over it again and again, even to the dismay of the intellect. Thus enumerating its unwholesome characteristics, Arjun declares that the mind is even more difficult to control than the wind. It is a powerful analogy for no one can ever think of controlling the mighty wind in the sky.

In this verse, Arjun has addressed the Lord as Krishna. The word “Krishna” means: karṣhati yogināṁ paramahansānāṁ chetānsi iti kṛiṣhṇaḥ [v25] “Krishna is he who forcefully attracts the minds of even the most powerfully-minded yogis and paramahansas.” Arjun is thus indicating that Krishna should also attract his restless, turbulent, strong, and obstinate mind.

śhrī bhagavān uvācha

asanśhayaṁ mahā-bāho mano durnigrahaṁ chalam

abhyāsena tu kaunteya vairāgyeṇa cha gṛihyate

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—Lord Krishna said; asanśhayam—undoubtedly; mahā-bāho—mighty-armed one; manaḥ—the mind; durnigraham—difficult to restrain; chalam—restless; abhyāsena—by practice; tu—but; kaunteya—Arjun, the son of Kunti; vairāgyeṇa—by detachment; cha—and; gṛihyate—can be controlled.

Lord Krishna said: O mighty-armed son of Kunti, what you say is correct; the mind is indeed very difficult to restrain. But by practice and detachment, it can be controlled.

Shree Krishna responds to Arjun’s comment by calling him Mahābāho, which means “Mighty armed one.” He implies, “O Arjun, you defeated the bravest warriors in battle. Can you not defeat the mind?”

Shree Krishna does not deny the problem, by saying, “Arjun, what nonsense are you speaking? The mind can be controlled very easily.” Rather, he agrees with Arjun’s statement that the mind is indeed difficult to control. However, so many things are difficult to achieve in the world and yet we remain undaunted and move forward. For example, sailors know that the sea is dangerous and the possibility of terrible storms exists. Yet, they have never found those dangers as sufficient reasons for remaining ashore. Hence, Shree Krishna assures Arjun that the mind can be controlled by vairāgya and abhyās.

Vairāgya means detachment. We observe that the mind runs toward the objects of its attachment, toward the direction it has been habituated to running in the past. The elimination of attachment eradicates the unnecessary wanderings of the mind.

Abhyās means practice, or a concerted and persistent effort to change an old habit or develop a new one. Practice is a very important word for sādhaks. In all fields of human endeavor, practice is the key that opens the door to mastery and excellence. Take, for example, a mundane activity such as typing. The first time people begin typing, they are able to type one word in a minute. But after a year’s typing, their fingers fly on the keyboard at the speed of eighty words a minute. This proficiency comes solely through practice. Similarly, the obstinate and turbulent mind has to be made to rest on the lotus feet of the Supreme Lord through abhyās. Take the mind away from the world—this is vairāgya—and bring the mind to rest on God—this is abhyās. Sage Patanjali gives the same instruction:

abhyāsa vairāgyābhyāṁ tannirodhaḥ (Yog Darśhan 1.12) [v26]

“The perturbations of the mind can be controlled by constant practice and detachment.”

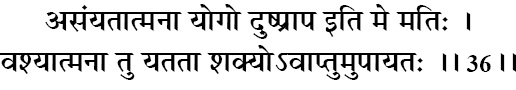

asaṅyatātmanā yogo duṣhprāpa iti me matiḥ

vaśhyātmanā tu yatatā śhakyo ’vāptum upāyataḥ

asanyata-ātmanā—one whose mind is unbridled; yogaḥ—Yog; duṣhprāpaḥ—difficult to attain; iti—thus; me—my; matiḥ—opinion; vaśhya-ātmanā—by one whose mind is controlled; tu—but; yatatā—one who strives; śhakyaḥ—possible; avāptum—to achieve; upāyataḥ—by right means.