Akṣhar Brahma Yog

The Yog of Eternal God

This chapter briefly explains several important terms and concepts that are presented more fully in the Upaniṣhads. It also describes what decides the destination of the soul after death. If we can remember God at the time of departing from the body, we will certainly attain him. Therefore, we must practice to think of him at all times, alongside with doing our daily works. We can remember him by thinking of his qualities, attributes, and virtues. We must also practice steadfast yogic concentration upon him by chanting his names. When we perfectly absorb our mind in him through exclusive devotion, we will go beyond this material dimension to the spiritual realm.

The chapter then talks about the various abodes that exist in the material realm. It explains how, in the cycle of creation, these abodes and the multitudes of beings on them come into existence, and are then again absorbed back at the time of dissolution. However, transcendental to this manifest and unmanifest creation is the divine abode of God. Those who follow the path of light, ultimately reach the divine abode, and never return to this mortal world, while those who follow the path of darkness keep transmigrating in the endless cycle of birth, disease, old age, and death.

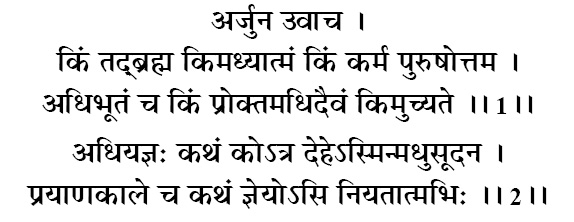

arjuna uvācha

kiṁ tad brahma kim adhyātmaṁ kiṁ karma puruṣhottama

adhibhūtaṁ cha kiṁ proktam adhidaivaṁ kim uchyate

adhiyajñaḥ kathaṁ ko ’tra dehe ’smin madhusūdana

prayāṇa-kāle cha kathaṁ jñeyo ’si niyatātmabhiḥ

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; kim—what; tat—that; brahma—Brahman; kim—what; adhyātmam—the individual soul; kim—what; karma—the principle of karma; puruṣha-uttama—Shree Krishna, the Supreme Divine Personality; adhibhūtam—the material manifestation; cha—and; kim—what; proktam—is called; adhidaivam—the Lord of the celestial gods; kim—what; uchyate—is called; adhiyajñaḥ—the Lord all sacrificial performances; katham—how; kaḥ—who; atra—here; dehe—in body; asmin—this; madhusūdana—Shree Krishna, the killer of the demon named Madhu; prayāṇa-kāle—at the time of death; cha—and; katham—how; jñeyaḥ—to be known; asi—are (you); niyata-ātmabhiḥ—by those of steadfast mind.

Arjun said: O Supreme Lord, what is Brahman (Absolute Reality), what is adhyātma (the individual soul), and what is karma? What is said to be adhibhūta, and who is said to be Adhidaiva? Who is Adhiyajña in the body and how is he the Adhiyajña? O Krishna, how are you to be known at the time of death by those of steadfast mind?

At the conclusion of Chapter seven, Shree Krishna had introduced terms like Brahman, adhibhūta, adhiyātma, adhidaiva, and adhiyajña. Arjun is curious to learn more about these terms, consequently he raises seven questions in these two verses. Six of these questions relate to the terms mentioned by Shree Krishna. The seventh question is about the time of death. Shree Krishna had himself raised the topic in verse 7.30. Arjun now wishes to know how one can remember God at the moment of death.

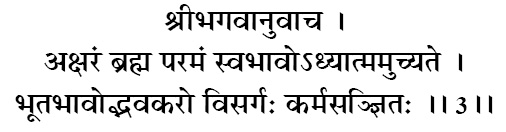

śhrī bhagavān uvācha

akṣharaṁ brahma paramaṁ svabhāvo ’dhyātmam uchyate

bhūta-bhāvodbhava-karo visargaḥ karma-sanjñitaḥ

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Blessed Lord said; akṣharam—indestructible; brahma—Brahman; paramam—the Supreme; svabhāvaḥ—nature; adhyātmam—one’s own self; uchyate—is called; bhūta-bhāva-udbhava-karaḥ—Actions pertaining to the material personality of living beings, and its development; visargaḥ—creation; karma—fruitive activities; sanjñitaḥ—are called.

The Blessed Lord said: The Supreme Indestructible Entity is called Brahman; one’s own self is called adhyātma. Actions pertaining to the material personality of living beings, and its development are called karma, or fruitive activities.

Shree Krishna says that the Supreme Entity is called Brahman (in the Vedas, God is referred to by many names and Brahman is one of them). It is beyond space, time, and the chain of cause and effect. These are the characteristics of the material realm, while Brahman is transcendental to the material plane. It is unaffected by the changes in the universe, and is imperishable. Hence, it is described as akṣharam. In the Bṛihadāraṇyak Upaniṣhad 3.8.8, Brahman has been described in the same manner: “Learned people speak of Brahman as akṣhar (indestructible). It is also designated as Param (Supreme) because it possesses qualities beyond those possessed by Maya and the souls.”

The path of spirituality is called adhyātma, and science of the soul is also called adhyātma. But here the word has been used for one’s own self, which includes the soul, body, mind, and intellect.

Karma is actions performed by the self, which forge the individual’s unique conditions of existence from birth to birth. These karmas keep the soul rotating in samsara (the cycle of material existence).

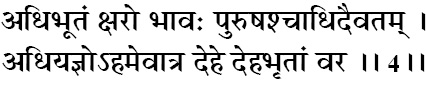

adhibhūtaṁ kṣharo bhāvaḥ puruṣhaśh chādhidaivatam

adhiyajño ’ham evātra dehe deha-bhṛitāṁ vara

adhibhūtam—the ever changing physical manifestation; kṣharaḥ—perishable; bhāvaḥ—nature; puruṣhaḥ—the cosmic personality of God, encompassing the material creation; cha—and; adhidaivatam—the Lord of the celestial gods; adhiyajñaḥ—the Lord of all sacrifices; aham—I; eva—certainly; atra—here; dehe—in the body; deha-bhṛitām—of the embodied; vara—O best.

O best of the embodied souls, the physical manifestation that is constantly changing is called adhibhūta; the universal form of God, which presides over the celestial gods in this creation, is called adhidaiva; I, who dwell in the heart of every living being, am called Adhiyajña, or the Lord of all sacrifices.

The kaleidoscope of the universe, consisting of all manifestations of the five elements—earth, water, fire, air, space—is called adhibhūta. The virāṭ puruṣh, which is the complete cosmic personality of God encompassing the entire material creation, is called adhidaiva because he has sovereignty over the devatās (the celestial gods who administer the different departments of the universe). The Supreme Divine Personality, Shree Krishna, who dwells in the heart of all living beings as the Paramātmā (Supreme soul) is called Adhiyajña. All yajñas (sacrifices) are to be performed for his satisfaction. He is thus the presiding divinity over all the yajñas and the one who bestows rewards for all actions.

This verse and the previous one answer six of Arjun’s seven questions, which are more in regard to terminology. The next few verses answer the question regarding the moment of death.

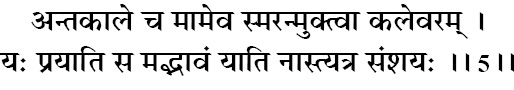

anta-kāle cha mām eva smaran muktvā kalevaram

yaḥ prayāti sa mad-bhāvaṁ yāti nāstyatra sanśhayaḥ

anta-kāle—at the time of death; cha—and; mām—me; eva—alone; smaran—remembering; muktvā—relinquish; kalevaram—the body; yaḥ—who; prayāti—goes; saḥ—he; mat-bhāvam—Godlike nature; yāti—achieves; na—no; asti—there is; atra—here; sanśhayaḥ—doubt.

Those who relinquish the body while remembering me at the moment of death will come to me. There is certainly no doubt about this.

In the next verse, Shree Krishna will state the principle that one’s next birth is determined by one’s state of consciousness at the time of death and the object of one’s absorption. So if, at the time of death, one is absorbed in the transcendental names, forms, virtues, pastimes, and abodes of God, one will attain the cherished goal of God-realization. Shree Krishna uses the words mad bhāvaṁ, which mean “Godlike nature.” Thus, if one’s consciousness is absorbed in God at the moment of death, one attains him, and becomes God-like in character.

yaṁ yaṁ vāpi smaran bhāvaṁ tyajatyante kalevaram

taṁ tam evaiti kaunteya sadā tad-bhāva-bhāvitaḥ

yam yam—whatever; vā—or; api—even; smaran—remembering; bhāvam—remembrance; tyajati—gives up; ante—in the end; kalevaram—the body; tam—to that; tam—to that; eva—certainly; eti—gets; kaunteya—Arjun, the son of Kunti; sadā—always; tat—that; bhāva-bhāvitaḥ—absorbed in contemplation.

Whatever one remembers upon giving up the body at the time of death, O son of Kunti, one attains that state, being always absorbed in such contemplation.

We may succeed in teaching a parrot to say “Good morning!” But if we press its throat hard, it will forget what it has artificially learnt and make its natural sound “Kaw!” Similarly, at the time of death, our mind naturally flows through the channels of thoughts it has created through lifelong habit. The time to decide our travel plans is not when our baggage is already packed; rather, it requires careful planning and execution beforehand. Whatever prominently dominates one’s thoughts at the moment of death will determine one’s next birth. This is what Shree Krishna states in this verse.

One’s final thoughts will naturally be determined by what was constantly contemplated and meditated upon during the span of life, as influenced by one's daily habits and associations. The Puranas relate the story of Maharaj Bharat. He was a king, but he renounced his kingdom to live in the forest as an ascetic and pursue God-realization. One day, he saw a pregnant deer jump into the water on hearing a tiger roar. Out of fear, the pregnant deer delivered a baby deer that began floating on the water. Bharat felt pity on the baby deer and rescued it. He took it to his hut and began bringing it up. With great affection, he would watch its frolicking movements. He would gather grass to feed it, and would hug it to keep it warm. Slowly, his mind came away from God and became absorbed in the deer. The absorption became so deep that, practically all day long, his thoughts would wander toward the deer. When he was about to die, he called out to the deer in fond remembrance, concerned about what would happen to him. Consequently, in his next life, Maharaj Bharat became a deer. However, because he had performed spiritual sādhanā, he was aware of the mistake in his previous life, and so even as a deer, he would reside near the āśhrams of saintly persons in the forest. Finally, when he gave up the deer body, he was again given a human birth. This time, he became the great sage Jadabharat, and attained God-realization by completing his sādhanā.

One should not conclude upon reading the verse, that for the attainment of the ultimate goal, the Supreme Lord is only to be meditated upon at the moment of death. This is well-nigh impossible without a lifetime of preparation. The Skandh Purāṇ states that at the time of death it is exceedingly difficult to remember God. Death is such a painful experience, that the mind naturally gravitates to the thoughts that constitute one’s inner nature. For the mind to think of God requires one’s inner nature to be united with him. The inner nature is the consciousness that abides within one’s mind and intellect. Only if we contemplate something continuously does it manifest as a part of our inner nature. So to develop a God-consciousness inner nature, the Lord must be remembered, recollected, and contemplated upon at every moment of our life. This is what Shree Krishna states in the next verse.

tasmāt sarveṣhu kāleṣhu mām anusmara yudhya cha

mayyarpita-mano-buddhir mām evaiṣhyasyasanśhayam

tasmāt—therefore; sarveṣhu—in all; kāleṣhu—times; mām—me; anusmara—remember; yudhya—fight; cha—and; mayi—to me; arpita—surrender; manaḥ—mind; buddhiḥ—intellect; mām—to me; eva—surely; eṣhyasi—you shall attain; asanśhayaḥ—without a doubt.

Therefore, always remember me and also do your duty of fighting the war. With mind and intellect surrendered to me, you will definitely attain me; of this, there is no doubt.

The first line of this verse is the essence of teachings of the Bhagavad Gita. It has the power of making our life divine. It also encapsulates the definition of karm yog. Shree Krishna says, “Keep your mind attached to me, and do your worldly duty with your body.” This applies to people in all walks of life—doctors, engineers, advocates, housewives, students, etc. In Arjun’s specific case, he is a warrior and his duty is to fight. So he is being instructed to fulfill his duty, while keeping his mind in God. Some people neglect their worldly duties on the plea that they have taken to spiritual life. Others excuse themselves from spiritual practice on the pretext of worldly engagements. People believe that spiritual and material pursuits are irreconcilable. But God’s message is to sanctify one’s entire life.

When we practice such karm yog, the worldly works will not suffer because the body is being engaged in them. But since the mind is attached to God, these works will not bind one in the law of karma. Only those works result in karmic reactions which are performed with attachment. When that attachment does not exist, even worldly law does not hold one culpable. For example, let us say that one man killed another and is brought to court. The judge asks him, “Did you kill that man?” The man replies, “Yes, your honor, there is no need for any witness. I confess that I killed him.” “Then you should be punished!” “No, your honor, you cannot punish me.” “Why?” “I had no intention to kill. I was driving the car on the proper side of the road, within speed limits, with my eyes focused ahead. My brakes, steering, everything was perfect. That man suddenly ran in front of my car. What could I do?” If his attorney can establish that the intention to kill did not exist, the judge will let him off without even the slightest punishment.

From the above example we see that even in the world we are not culpable for those actions we perform without attachment. The same principle holds for the law of karma as well. That is why, during the Mahabharat war, following Shree Krishna’s instructions, Arjun did his duty on the battlefield. By the end of the war, Shree Krishna noted that Arjun did not accrue any bad karma. He would have been entangled in karma if he had been fighting the battle with attachment, for worldly gain or fame. However, his mind was attached to Shree Krishna, and so what he was doing was multiplication in zeros, performing his duty in this world without selfish attachment. Even if you multiply one million with zero, the answer will still be zero.

The condition for karm yog has been stated very clearly in this verse: The mind must be constantly engaged in thinking of God. The moment the mind forgets God, it comes under the attack of the big generals of Maya’s army—lust, anger, greed, envy, hatred, etc. Thus, it is important to always keep it attached to God. Often people claim to be karm yogis because they say they do both—karm and yog. For the major part of the day, they do karm, and for a few minutes they do yog (meditation on God). But this is not the definition of karm yog that Shree Krishna has given. He states that 1) even while doing the work, the mind must be engaged in thinking of God, and 2) the remembrance of God must not be intermittent, but constant throughout the day.

Saint Kabir expresses this in his famous couplet:

sumiran kī sudhi yoṅ karo, jyauṅ gāgar panihāra

bolat dolat surati meṅ, kahe kabīra vichār [v1]

“Remember God just as the village woman remembers the water pot on her head. She speaks with others and walks on the path, but her mind keeps holding onto the pot.”

Shree Krishna explains the consequences of practicing karm yog in the next verse.

abhyāsa-yoga-yuktena chetasā nānya-gāminā

paramaṁ puruṣhaṁ divyaṁ yāti pārthānuchintayan

abhyāsa-yoga—by practice of yog; yuktena—being constantly engaged in remembrance; chetasā—by the mind; na anya-gāminā—without deviating; paramam puruṣham—the Supreme Divine Personality; divyam—divine; yāti—one attains; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; anuchintayan—constant remembrance.

With practice, O Parth, when you constantly engage the mind in remembering me, the Supreme Divine Personality, without deviating, you will certainly attain me.

This instruction to keep the mind always engaged in meditating upon God has been repeated numerous times in the Bhagavad Gita. Here are a few verses:

ananya-chetāḥ satataṁ 8.14

mayyeva mana ādhatsva 12.8

teṣhāṁ satata-yuktānāṁ 10.10

The word abhyāsa means practice—the training and habituating of the mind to meditate upon God. Such practice is to be done, not at fixed times of the day at regular intervals, but continuously, along with all the daily activities of life.

When the mind is attached to God, it will get purified, even while performing worldly duties. It is important to remember that what we think with our mind fashions our future, not the actions we perform with our body. It is the mind that is to be engaged in devotion, and it is the mind that is to be surrendered to God. And when the absorption of the consciousness in God is complete, one will receive the divine grace. By God’s grace, one will attain liberation from material bondage, and will receive the unlimited divine bliss, divine knowledge, and divine love of God. Such a soul will become God-realized in this body itself, and upon leaving the body, will go to the abode of God.

kaviṁ purāṇam anuśhāsitāram

aṇor aṇīyānsam anusmared yaḥ

sarvasya dhātāram achintya-rūpam

āditya-varṇaṁ tamasaḥ parastāt

prayāṇa-kāle manasāchalena

bhaktyā yukto yoga-balena chaiva

bhruvor madhye prāṇam āveśhya samyak

sa taṁ paraṁ puruṣham upaiti divyam

kavim—poet; purāṇam—ancient; anuśhāsitāram—the controller; aṇoḥ—than the atom; aṇīyānsam—smaller; anusmaret—always remembers; yaḥ—who; sarvasya—of everything; dhātāram—the support; achintya—inconceivable; rūpam—divine form; āditya-varṇam—effulgent like the sun; tamasaḥ—to the darkness of ignorance; parastāt—beyond; prayāṇa-kāle—at the time of death; manasā—mind; achalena—steadily; bhaktyā—remembering with great devotion; yuktaḥ—united; yoga-balena—through the power of yog; cha—and; eva—certainly; bhruvoḥ—the two eyebrows; madhye—between; prāṇam—life airs; āveśhya—fixing; samyak—completely; saḥ—he; tam—him; param puruṣham—the Supreme Divine Lord; upaiti—attains; divyam—divine.

God is omniscient, the most ancient one, the controller, subtler than the subtlest, the support of all, and the possessor of an inconceivable divine form; he is brighter than the sun, and beyond all darkness of ignorance. One who at the time of death, with unmoving mind attained by the practice of Yog, who fixes the prāṇ (life airs) between the eyebrows, and steadily remembers the Divine Lord with great devotion, certainly attains him.

Meditation upon God can be of a variety of types. One can meditate upon the names, forms, qualities, leelas, abode, or associates of God. All these different aspects of the Supreme Divinity are non-different from him. When we attach our mind to any of these, our mind comes into the divine realm and hence becomes purified. Hence, any or all of these can be made the object of meditation. Here, eight qualities of the Supreme Lord have been described, which can be meditated upon.

Kavi means poet or seer, and by extension, omniscient. As stated in verse 7.26, God knows the past, present, and future.

Purāṇ means without beginning and the most ancient. God is the origin of everything spiritual and material, but there is nothing from which he has originated and nothing that predates him.

Anuśhāsitāram means the Ruler. God is the creator of the laws by which the universe runs; he administers its affairs, directly and through his appointed celestial gods. Thus, everything is under his regime.

Aṇoraṇīyān means subtler than the subtlest. The soul is subtler than matter, but God is seated within the soul, and hence he is subtler than it.

Sarvasya Dhātā means the sustainer of all, just as the ocean is the support of the waves.

Achintya rūpa means of inconceivable form. Since our mind can only conceive material forms, God is beyond the scope of our material mind. However, if he bestows his grace, by his Yogmaya power he makes our mind divine in nature. Then alone, by his grace, he becomes conceivable.

Āditya varṇa means he is resplendent like the sun.

Tamasaḥ Parastāt means beyond the darkness of ignorance. Just as the sun can never be covered by the clouds, even though it may seem to us that it has been obscured, similarly God can never be covered by the material energy Maya even though he may be in contact with it in the world.

In bhakti, the mind is focused upon the divine attributes of God’s form, qualities, pastimes, etc. When bhakti is performed by itself, it is called śhuddha bhakti (pure bhakti). When it is performed alongside with aṣhṭāṅg yog, it is called yog-miśhra bhakti (devotion alloyed with aṣhṭāṅg yog sādhanā). From verses ten to thirteen, Shree Krishna describes yog-miśhra bhakti. One of the beauties of the Bhagavad Gita is that it embraces a variety of sādhanās, thereby bringing people of diverse upbringing, backgrounds, and personalities in its embrace. When western scholars attempt to read the Hindu scriptures without the help of a Guru, they often become confused by the variety of paths, instructions, and philosophical viewpoints in its various scriptures. However, this variety is actually a blessing. Because of the sanskārs (tendencies) of endless lifetimes, we all have different natures and preferences. When four people go to buy clothes for themselves, they end up choosing different colors, styles, and fashions. If the shop kept clothes of only one color and style, it would be unable to cater to the variety inherent in human nature. Similarly, on the spiritual path too, people have performed various sādhanās in past lifetimes. The Vedic scriptures embrace that variety, while simultaneously stressing bhakti (devotion to God) as the common thread that ties them all together.

In aṣhṭāṅg yog, the life force is raised through the suṣhumṇā channel in the spinal column. It is brought between the eyebrows, which is the region of the third eye (the inner eye). It is then made to focus on the Supreme Lord with great devotion.

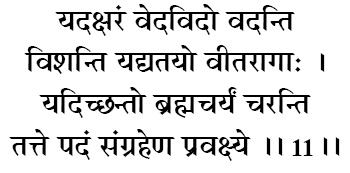

yad akṣharaṁ veda-vido vadanti

viśhanti yad yatayo vīta-rāgāḥ

yad ichchhanto brahmacharyaṁ charanti

tat te padaṁ saṅgraheṇa pravakṣhye

yat—which; akṣharam—Imperishable; veda-vidaḥ—scholars of the Vedas; vadanti—describe; viśhanti—enter; yat—which; yatayaḥ—great ascetics; vīta-rāgāḥ—free from attachment; yat—which; ichchhantaḥ—desiring; brahmacharyam—celibacy; charanti—practice; tat—that; te—to you; padam—goal; saṅgraheṇa—briefly; pravakṣhye—I shall explain.

Scholars of the Vedas describe him as Imperishable; great ascetics practice the vow of celibacy and renounce worldly pleasures to enter into him. I shall now explain to you briefly the path to that goal.

God has been referred to by many names in the Vedas. Some of them are: Sat, Avyākṛit, Prāṇ, Indra, Dev, Brahman, Paramātmā, Bhagavān, Puruṣh. In various places, while referring to the formless aspect of God, he has also been called by the name Akṣhar. The word Akṣhar means “imperishable.” The Bṛihadāraṇyak Upaniṣhad states:

etasya vā akṣharasya praśhāsane gārgi sūryachandramasau vidhṛitau tiṣhṭhataḥ

(3.8.9) [v2]

“Under the mighty control of the Imperishable, the sun and the moon are held on their course.” In this verse, Shree Krishna describes the path of yog-miśhrā bhakti, to attain the formless aspect of God. The word sangraheṇa means “in brief.” He will describe the path only briefly, to avoid emphasizing it, since the path is not suitable for everyone.

On this path, one must perform severe austerities, renouncing worldly desires, practicing brahmacharya, and living a life of rigid continence. Brahmacharya is the vow of celibacy. Through it, a person’s physical energy gets conserved, and then transformed through sādhanā into spiritual energy. An aspirant who practices celibacy enhances memory power and the intellect for comprehending spiritual topics. This has been previously explained in detail in verse 6.14.

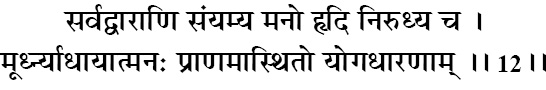

sarva-dvārāṇi sanyamya mano hṛidi nirudhya cha

mūrdhnyādhāyātmanaḥ prāṇam āsthito yoga-dhāraṇām

sarva-dvārāṇi—all gates; sanyamya—restraining; manaḥ—the mind; hṛidi—in the heart region; nirudhya—confining; cha—and; mūrdhni—in the head; ādhāya—establish; ātmanaḥ—of the self; prāṇam—the life breath; āsthitaḥ—situated (in); yoga-dhāraṇām—the yogic concentration.

Restraining all the gates of the body and fixing the mind in the heart region, and then drawing the life-breath to the head, one should get established in steadfast yogic concentration.

The world enters the mind through the senses. We first see, hear, touch, taste, and smell the objects of perception. Then the mind dwells upon these objects. Repeated contemplation creates attachment, which automatically creates further repetition of the thoughts in the mind. Restraining the senses is thus an essential aspect of locking the world out of the mind. A practitioner of meditation who neglects this point has to keep grappling with the incessant stream of worldly thoughts that the unrestrained senses create. Hence, Shree Krishna delivers the instruction to guard the gates of the body. The words sarva-dvārāṇi-sanyamya mean “controlling the passages that enter the body.” This implies restricting the senses from their normal outgoing tendencies. The words hṛidi nirudhya mean “locking the mind in the heart.” This denotes directing devotional feelings from the mind to the akṣharam imperishable Supreme Lord enthroned there. The words yoga-dhāraṇām mean “uniting the consciousness with God.” This refers to meditating upon him with complete attention.

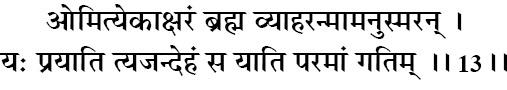

om ityekākṣharaṁ brahma vyāharan mām anusmaran

yaḥ prayāti tyajan dehaṁ sa yāti paramāṁ gatim

om—sacred syllable representing the formless aspect of God; iti—thus; eka-akṣharam—one syllabled; brahma—the Absolute Truth; vyāharan—chanting; mām—me (Shree Krishna); anusmaran—remembering; yaḥ—who; prayāti—departs; tyajan—quitting; deham—the body; saḥ—he; yāti—attains; paramām—the supreme; gatim—goal.

One who departs from the body while remembering me, the Supreme Personality, and chanting the syllable Om, will attain the supreme goal.

The sacred syllable Om, also called Praṇav, represents the sound manifestation of Brahman (the formless aspect of the Supreme Lord, without virtues and attributes). Hence, it is considered imperishable like God Himself. Since here Shree Krishna is describing the process of meditation in the context of aṣhṭāṅg yog sādhanā, he states that one should chant the syllable “Om,” to bring the mind into focus, while practicing austerities and maintaining the vow of celibacy. The Vedic scriptures also refer to “Om” as the anāhat nād. It is the sound that pervades creation, and can be heard by yogis who tune in to it.

The Bible says “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1) [v2.1] The Vedic scriptures also state that God first created sound, from sound he created space, and then proceeded further in the process of creation. That original sound was “Om,”. As a result, it is accorded so much of importance in the Vedic philosophy. It is called a mahā vākya, or great sound vibration of the Vedas. It is also called the bīja mantra, because it is often attached to the beginning of the Vedic mantras, just as hrīṁ, klīṁ, etc. The vibrations of Om consist of three letters: A…U…M. In the proper chanting of Om, one begins by making the sound “A” from the belly, with an open throat and mouth. This is merged into the chanting of the sound “U” that is created from the middle of the mouth. The sequence ends with chanting “M” with the mouth closed. The three parts A … U … M have many meanings and interpretations. For the devotees, Om is the name for the impersonal aspect of God.

This Praṇav sound is the object of meditation in aṣhṭāṅg yog. In the path of bhakti yog, devotees prefer to meditate upon the personal names of the Lord, such as Ram, Krishna, Shiv, etc. because of the greater sweetness of God’s bliss in these personal names. The distinction is like the difference between having a baby in the womb and a baby in the lap. The baby in the lap is a far sweeter experience than the baby in the womb.

The final examination of our meditation is the time of death. Those who are able to fix their consciousness upon God, despite the intense pain of death, pass this exam. Such persons attain the Supreme destination upon leaving their body. This is extremely difficult and requires a lifetime of practice. In the following verse, Shree Krishna gives an easy way of gaining such mastery.

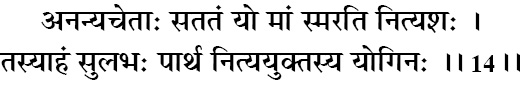

ananya-chetāḥ satataṁ yo māṁ smarati nityaśhaḥ

tasyāhaṁ sulabhaḥ pārtha nitya-yuktasya yoginaḥ

ananya-chetāḥ—without deviation of the mind; satatam—always; yaḥ—who; mām—me; smarati—remembers; nityaśhaḥ—regularly; tasya—to him; aham—I; su-labhaḥ—easily attainable; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; nitya—constantly; yuktasya—engaged; yoginaḥ—of the yogis.

O Parth, for those yogis who always think of me with exclusive devotion, I am easily attainable because of their constant absorption in me.

Throughout the Bhagavad Gita, Shree Krishna has repeatedly stressed upon devotion. In the previous verse, Shree Krishna expounded meditation on the formless manifestation of God, devoid of attributes. This is not only dry but also very difficult. So now he gives an easier alternative, which is meditation upon his personal form as Krishna, Ram, Shiv, Vishnu, etc. This includes the names, forms, virtues, pastimes, abodes, and associates of his supreme divine form.

In the entire Bhagavad Gita, this is the only verse in which Shree Krishna says that he is easy to attain. However, the condition he states is ananya-chetāḥ, which means that the mind must be exclusively absorbed in him and him alone. The word ananya is very important. Etymologically, it means na anya, or “no other.” The mind should be attached to no one else but God alone. This condition of exclusivity has often been repeated in the Bhagavad Gita.

ananyāśh chintayanto māṁ 9.22

tam eva śharaṇaṁ gachchha 18.62

mām ekaṁ śharaṇaṁ vraja 18.66

Exclusive devotion has been stressed in the other scriptures too.

mām ekam eva śharaṇam ātmānaṁ sarva-dehinām (Bhāgavatam 11.12.15) [v3]

“Surrender to me alone, who am the Supreme soul of all living beings.”

eka bharoso eka bala ek āsa visvāsa (Ramayan) [v4]

“I have only one support, one strength, one faith, one shelter; and that is Shree Ram.”

anyāśhrayāṇāṁ tyāgo ’nanyatā (Nārad Bhakti Darśhan, Sūtra 10) [v5]

“Reject all other shelters, and become exclusive to God.”

Exclusive devotion means that the mind must be attached only to the names, forms, virtues, pastimes, abodes, and associates of God. The logic is very simple. The aim of sādhanā is to purify the mind, and this is accomplished only by attaching it to the all-pure God. However, if we cleanse the mind by contemplating upon God, and then again dirty it by dipping it in worldliness, then no matter how long we try, we will never be able to clean it.

This is exactly the mistake that many people make. They love God but they also love and get attached to worldly people and objects. So whatever positive gains they accomplish through sādhanā become tarnished by worldly attachment. If you apply soap on a cloth to cleanse it, but simultaneously keep throwing dirt upon it, your effort will be an exercise in futility. Hence, Shree Krishna says that it not just devotion, but exclusive devotion to him that makes him easily attainable.

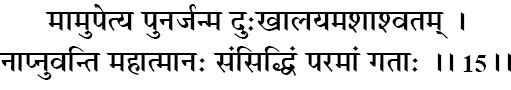

mām upetya punar janma duḥkhālayam aśhāśhvatam

nāpnuvanti mahātmānaḥ sansiddhiṁ paramāṁ gatāḥ

mām—me; upetya—having attained; punaḥ—again; janma—birth; duḥkha-ālayam—place full of miseries; aśhāśhvatam—temporary; na—never; āpnuvanti—attain; mahā-ātmānaḥ—the great souls; sansiddhim—perfection; paramām—highest; gatāḥ—having achieved.

Having attained me, the great souls are no more subject to rebirth in this world, which is transient and full of misery, because they have attained the highest perfection.

What is the result of attaining God? Those who become God-realized get released from the cycle of life and death, and reach the divine abode of God. Thus, they do not have to take birth again in this material world, which is a place of suffering. We suffer the painful process of birth, crying helplessly. Then as babies, we have needs that we can’t express, and so we cry. In adolescence we have to grapple with bodily desires that make us suffer mental anguish. In married life, we endure the idiosyncrasies of the spouse. When we reach old age, we suffer from bodily infirmities. All through life, we suffer the miseries from our own body and mind, the behavior of others, and inclement environment. Finally, we suffer the pain of death.

All this misery is not meaningless; it also has a purpose in the grand design of God. It gives us the realization that the material realm is not our permanent home. It is like the reformatory for souls like us who have turned their backs toward God. If we did not suffer misery here, we would never develop the desire for God. For example, if we put our hand in the fire, two things happen—the skin starts getting burnt, and the neurons create a sensation of pain in the brain. The burning of the skin is a bad thing, but the sensation of pain is a good thing. If we did not experience the pain, we would not extract our hand from the fire, and it would suffer extensive damage. The pain is thus an indication that something is wrong, which needs to be corrected. Similarly, the pain we experience in the material realm is God’s signal that our consciousness is defective and we need to progress from material consciousness toward union with God.

Ultimately, we get whatever we have made ourselves worthy of through our chosen efforts. Those who remain with their consciousness turned around from God continue rotating in the wheel of birth and death; and those who achieve exclusive devotion to God attain his divine abode.

ā-brahma-bhuvanāl lokāḥ punar āvartino ’rjuna

mām upetya tu kaunteya punar janma na vidyate

ā-brahma-bhuvanāt—up to the abode of Brahma; lokāḥ—worlds; punaḥ āvartinaḥ—subject to rebirth; arjuna—Arjun; mām—mine; upetya—having attained; tu—but; kaunteya—Arjun, the son of Kunti; punaḥ janma—rebirth; na—never; vidyate—is.

In all the worlds of this material creation, up to the highest abode of Brahma, you will be subject to rebirth, O Arjun. But on attaining my abode, O son of Kunti, there is no further rebirth.

The Vedic scriptures describe seven planes of existence lower than the earthly plane—tal, atal, vital, sutal, talātal, rasātal, pātāl. These are called narak, or the hellish abodes. There are also seven planes of existence starting from the earthly plane and above—bhūḥ, bhuvaḥ, swaḥ, mahaḥ, janaḥ, tapaḥ, satyaḥ. The ones above are called swarg, or celestial abodes. Other religious traditions also refer to the seven heavens. In Judaism, seven heavens are named in the Talmud, with Araboth named as the highest (see also Psalm 68.4). In Islam also, there is mention of seven heavens with the sātvāñ āsmān (seventh sky) enumerated as the highest.

The different planes of existence are called the various worlds. There are fourteen worlds in our universe. The highest amongst them is the abode of Brahma, called Brahma Lok. All of these lokas are within the realm of Maya, and the residents of these lokas are subject to the cycle of birth and death. Shree Krishna has referred to them in the previous verse as duḥkhālayam and aśhāśhvatam (impermanent and full of misery).

Even Indra, the king of the celestial gods, has to die one day. The Puranas relate that once Indra engaged Vishwakarma, the celestial architect, in the construction of a huge palace. Wearied by its construction, which was not ending, Vishwakarma prayed to God for help. God came there, and he asked Indra, “Such a huge palace! How many Vishwakarmas have been engaged in its making?” Indra was surprised by the question, and replied, “I thought there was only one Vishwakarma.” God smiled and said, “Like this universe with fourteen worlds, there are unlimited universes. Each has one Indra and one Vishwakarma.”

Then Indra saw lines of ants walking toward him. He was surprised and asked from where so many ants were coming. God said, “I have brought all those souls here who were Indra once in their past lives, and are now in the bodies of ants.” Indra was astonished by their vast number.

Shortly after, Lomesh Rishi came to the scene. He was carrying a straw mat on his head; on his chest was a circle of hair. Some hair had fallen from the circle, creating gaps. Indra received the sage, and politely queried from him, “Sir, why do you carry a straw mattress on your head. And what is the meaning of the hair circle on your chest?”

Lomesh Rishi replied, “I have received the boon of chirāyu (long life). At the end of one Indra’s tenure in this universe, one hair falls of. That explains the gaps in the circle. My disciples wish to build a house for me to stay in, but I think that life is temporary, so why build a residence here? I keep this straw mat, which protects me from rain and the sun. At night, I spread it on the ground and go to sleep.” Indra was astonished, thinking, “This ṛiṣhi has the lifespan of many Indras, and yet he says that life is temporary. Then why am I building such a big palace?” His pride was squashed and he let Vishwakarma go.

While reading these stories, we also must not fail to marvel at the amazing insight of the Bhagavad Gita regarding the cosmology of the universe. As late as in the sixteenth century, Nicholas Copernicus was the first western scientist to propose a proper heliocentric theory stating that the sun was in fact the center of the universe. Until then, the entire Western world believed that the earth was the center of the universe. Subsequent advancement in astronomy revealed that the sun was also not the center of the universe, but rotating around the epicenter of a galaxy called the Milky Way. Further progress enabled scientists to conclude that there are many galaxies like the Milky Way, each of them having innumerable stars, like our Sun.

In contrast, Vedic philosophy states five thousand years ago that the earth is Bhūr Lok, which is rotating around Swar Lok, and between them is the realm called Bhuvar Lok. But Swar Lok is also not stationary either; it is fixed in the gravitation of Jana Lok, and between them is the realm called Mahar Lok. But Jana Lok is not stationary either; it is rotating around Brahma Lok (Satya Lok), and between them is the realm called Tapa Lok. This explains the seven higher worlds; similarly, there are seven lower worlds. Now, for an insight given five thousand years ago, this is most amazing!

Shree Krishna says in this verse that all the fourteen worlds in the universe are within the realm of Maya, and hence their residents are subject to the cycle of birth and death. However, those who attain God-realization are released from the bondage of the material energy. Upon leaving this material body at death, they attain the divine abode of God. There, they receive divine bodies in which they eternally participate in the divine pastimes of God. Thus, they do not have to take birth in this material world again. Some Saints do come back even after liberation from Maya. But they do so only to help others get out of bondage as well. These are the great descended Masters and great Prophets, who engage in the divine welfare of humankind.

sahasra-yuga-paryantam ahar yad brahmaṇo viduḥ

rātriṁ yuga-sahasrāntāṁ te ’ho-rātra-vido janāḥ

sahasra—one thousand; yuga—age; paryantam—until; ahaḥ—one day; yat—which; brahmaṇaḥ—of Brahma; viduḥ—know; rātrim—night; yuga-sahasra-antām—lasts one thousand yugas; te—they; ahaḥ-rātra-vidaḥ—those who know his day and night; janāḥ—people.

One day of Brahma (kalp) lasts a thousand cycles of the four ages (mahā yug) and his night also extends for the same span of time. The wise who know this understand the reality about day and night.

The measurements of time in the Vedic cosmological system are also vast and staggering. For example, there are insects that are born in the night; they grow up, procreate, lay eggs, and grow old, all in one night. In the morning, you see then all dead under the street lights. If these insects were told that their entire lifespan was only one night of human beings, they would find it incredulous.

Similarly, the Vedas state that one day and night of the celestial gods, such as Indra and Varun, corresponds to one year on the earth plane. One year of the celestial gods, consisting of 30 × 12 days is equal to 360 years on the earth plane. 12,000 years of the celestial gods correspond to one mahā yug (cycle of four yugas) on the earth plane, i.e. 4 million and 320 thousand years. This is the highest unit of time in the world, and is called a kalp.

1,000 such mahā yugas comprise one day of Brahma,. This is called kalp and is the largest unit of time in the world. Equal to that is Brahma’s night. By these calculations, Brahma lives for 100 years. By earth calculations, it is 311 trillion 40 billion years.

Thus, the Vedic calculations of time are as follows:

Kali Yug: 432,000 years.

Dwāpar Yug: 864,000 years.

Tretā Yug: 1,296,000 years.

Satya Yug: 1,728,000 years.

Together, they comprise a Mahā Yug: 4,320,000 years.

One thousand Mahā Yugas comprise one day of Brahma, which is a kalp: 43,200,000 years. Of equal duration is Brahma’s night. Shree Krishna says that those who understand this are the true knowers of day and night.

The entire duration of the universe is equal to Brahma’s lifespan of 100 years: 311 trillion 40 billion years. Brahma is also a soul, who has attained that position and is discharging his duties for God. Hence, Brahma is also within the cycle of life and death. However, being of extremely elevated consciousness, he is assured that at the end of his life, he will be released from the cycle of life and death and go to the abode of God. Occasionally, when no soul is eligible to perform the duties of Brahma at the time of the creation of the world, God himself becomes Brahma.

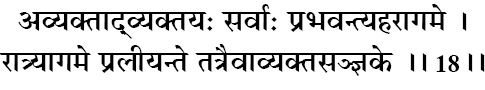

avyaktād vyaktayaḥ sarvāḥ prabhavantyahar-āgame

rātryāgame pralīyante tatraivāvyakta-sanjñake

avyaktāt—from the unmanifested; vyaktayaḥ—the manifested; sarvāḥ—all; prabhavanti—emanate; ahaḥ-āgame—at the advent of Brahma’s day; rātri-āgame—at the fall of Brahma’s night; pralīyante—they dissolve; tatra—into that; eva—certainly; avyakta-sanjñake—in that which is called the unmanifest.

At the advent of Brahma’s day, all living beings emanate from the unmanifest source. And at the fall of his night, all embodied beings again merge into their unmanifest source.

In the amazing cosmic play of the universe, the various worlds (planes of existence) and their planetary systems undergo repeated cycles of creation, preservation, and dissolution (sṛiṣhṭi, sthiti, and pralaya). At the end of Brahma’s day, corresponding to one kalp of 4,320,000,000 years, all the planetary systems up to Mahar Lok are destroyed. This is called naimittik pralaya (partial dissolution). In the Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam, Shukadev tells Parikshit that just as a child makes structures with toys during the day and dismantles them before sleeping, similarly, Brahma creates the planetary systems and their life forms when he wakes up and dismantles them before sleeping.

At the end of Brahma’s life of 100 years, the entire universe is dissolved. At this time, the entire material creation winds up. The pañch-mahābhūta merge into the pañch-tanmātrās, the pañch-tanmātrās merge into ahankār, ahankār merges into mahān, and mahān merges into prakṛiti. Prakṛiti is the subtle form of the material energy, Maya. Maya, in its primordial state, then goes and sits in the body of the Supreme Lord, Maha Vishnu. This is called prākṛit pralaya, or mahāpralaya (great dissolution). Again, when Maha Vishnu wishes to create, he glances at the material energy in the form of prakṛiti, and by his mere glance, it begins unfolding. From prakṛiti, mahān is created: from mahān, ahankār is created; from ahankār, pañch-tanmātrās are created; from pañch-tanmātrās, pañch-mahābhūta are created. In this way, unlimited universes are created.

Modern day scientists estimate that there are 100 billion stars in the Milky Way. Like the Milky Way, there are 1 billion galaxies in the universe. Thus, by estimation of scientists, there are 1020 stars in our universe. According to the Vedas, like our universe, there are innumerable universes, of differing sizes and features. Every time, Maha Vishnu breathes in, unlimited universes manifest from the pores of his body, and when he breathes out, all the universes dissolve back. Thus the 100 years of Brahma’s life are equal to one breath of Maha Vishnu. Each universe has one Brahma, one Vishnu, and one Shankar. So there are innumerable Brahmas, Vishnus, and Shankars in innumerable universes. All the Vishnus in all the universes are expansions of Maha Vishnu.

bhūta-grāmaḥ sa evāyaṁ bhūtvā bhūtvā pralīyate

rātryāgame ’vaśhaḥ pārtha prabhavatyahar-āgame

bhūta-grāmaḥ—the multitude of beings; saḥ—these; eva—certainly; ayam—this; bhūtvā bhūtvā—repeatedly taking birth; pralīyate—dissolves; rātri-āgame—with the advent of night; avaśhaḥ—helpless; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; prabhavati—become manifest; ahaḥ-āgame—with the advent of day.

The multitudes of beings repeatedly take birth with the advent of Brahma’s day, and are reabsorbed on the arrival of the cosmic night, to manifest again automatically on the advent of the next cosmic day.

The Vedas list four pralayas (dissolutions):

1. Nitya Pralaya: This is the daily dissolution of our consciousness that takes place when we fall into deep sleep.

2. Naimittik Pralaya: This is the dissolution of all the abodes up to Mahar Lok at the end of Brahma’s day. At that time, the souls residing in these abodes become unmanifest. They reside in a state of suspended animation in the body of Vishnu. Again when the Brahma creates these lokas, they are given birth according to their past karmas.

3. Mahā Pralaya: This is the dissolution of the entire universe at the end of Brahma’s life. At this time, all the souls in the universe go into a state of suspended animation in the body of Maha Vishnu. Their gross (sthūl śharīr) and subtle (sūkṣhma śharīr) bodies dissolve, but the causal body (kāraṇ sharīr) remains. When the next cycle of creation takes place, they are again given birth, according to their sanskārs and karmas stored in their causal body.

4. Ātyantik Pralaya: When the soul finally attains God, it gets released from the cycle of birth and death forever. Ātyantik Pralaya is the dissolution of the bonds of Maya, which were tying the soul since eternity.

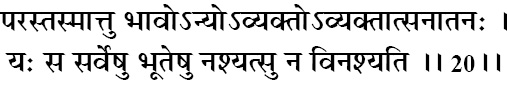

paras tasmāt tu bhāvo ’nyo ’vyakto ’vyaktāt sanātanaḥ

yaḥ sa sarveṣhu bhūteṣhu naśhyatsu na vinaśhyati

paraḥ—transcendental; tasmāt—than that; tu—but; bhāvaḥ—creation; anyaḥ—another; avyaktaḥ—unmanifest; avyaktāt—to the unmanifest; sanātanaḥ—eternal; yaḥ—who; saḥ—that; sarveṣhu—all; bhūteṣhu—in beings; naśhyatsu—cease to exist; na—never; vinaśhyati—is annihilated.

Transcendental to this manifest and unmanifest creation, there is yet another unmanifest eternal dimension. That realm does not cease even when all others do.

After completing his exposé on the material worlds and their impermanence, Shree Krishna next goes on to talk about the spiritual dimension. It is beyond the scope of the material energy, and is created by the spiritual Yogmaya energy of God. It is not destroyed when all the material worlds are destroyed. Shree Krishna mentions in verse 10.42 that the spiritual dimension is three-fourth of God’s entire creation, while the material dimension is one-fourth.

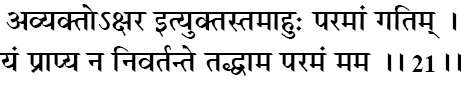

avyakto ’kṣhara ityuktas tam āhuḥ paramāṁ gatim

yaṁ prāpya na nivartante tad dhāma paramaṁ mama

avyaktaḥ—unmanifest; akṣharaḥ—imperishable; iti—thus; uktaḥ—is said; tam—that; āhuḥ—is called; paramām—the supreme; gatim—destination; yam—which; prāpya—having reached; na—never; nivartante—come back; tat—that; dhāma—abode; paramam—the supreme; mama—my.

That unmanifest dimension is the supreme goal, and upon reaching it, one never returns to this mortal world. That is my supreme abode.

The divine sky of the spiritual realm is called Paravyom. It contains the eternal abodes of the different forms of God, such as Golok (the abode of Shree Krishna), Saket Lok (the abode of Shree Ram), Vaikunth Lok (the abode of Narayan), Shiv Lok (the abode of Sadashiv), Devi Lok (the abode of Mother Durga), etc. In these Lokas, the Supreme Lord resides eternally in his divine forms along with his eternal associates. All these forms of God are non-different from each other; they are various forms of the same one God. Whichever form of God one worships, upon God-realization, one goes to the abode of that form of God. Receiving a divine body, the soul then participates in the divine activities and pastimes of the Lord for the rest of eternity.

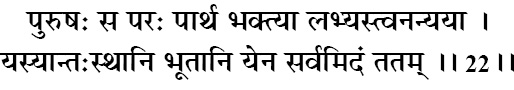

puruṣhaḥ sa paraḥ pārtha bhaktyā labhyas tvananyayā

yasyāntaḥ-sthāni bhūtāni yena sarvam idaṁ tatam

puruṣhaḥ—the Supreme Divine Personality; saḥ—he; paraḥ—greatest; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; bhaktyā—through devotion; labhyaḥ—is attainable; tu—indeed; ananyayā—without another; yasya—of whom; antaḥ-sthāni—situated within; bhūtāni—beings; yena—by whom; sarvam—all; idam—this; tatam—is pervaded.

The Supreme Divine Personality is greater than all that exists. Although he is all-pervading and all living beings are situated in him, yet he can be known only through devotion.

The same Supreme Lord, who resides in his divine abode in the spiritual sky, is seated in our hearts; he is also all-pervading in every atom of the material world. God is equally present everywhere; we cannot say that the all-pervading God is twenty-five percent present, while in his personal form he is a hundred percent present. He is one hundred percent everywhere. However, that all-pervading presence of God does not benefit us because we have no perception of it. Sage Shandilya states:

gavāṁ sarpiḥ śharīrasthaṁ na karotyaṅga poṣhaṇam (Śhāṇḍilya Bhakti Darśhan) [v6]

“Milk resides in the body of the cow, but it does not benefit the health of the cow, which is weak and sick.” The same milk is extracted from the body of the cow and converted into yogurt. The yogurt is then fed to the cow with a sprinkling of black pepper and it cures the cow.

Similarly, the all-pervading presence of God does not have the intimacy to enrich our devotion. We need to first worship him in his divine form and develop the purity of our heart. Then we attract God’s grace, and by his grace, he imbues our senses, mind, and intellect with his divine Yogmaya energy. Our senses then become divine and we are able to perceive the Divinity of the Lord, whether in his personal form or in his all-pervading aspect. Thus, Shree Krishna states that he can be known only through bhakti.

The need for doing bhakti has been repeatedly emphasized by Shree Krishna in the Bhagavad Geeta. In verse, 6.47, he stated that he considers one who is engaged in devotion to him to be the highest of all. Here, he emphatically uses the word ananyayā, which means “by no other path” can God be known. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu puts this very nicely:

bhakti mukh nirīkṣhata karm yog jñāna

(Chaitanya Charitāmṛit, Madhya 22.17) [v7]

“Although karm, jñāna, and aṣhṭāṅg yog are also pathways to God-realization, all these require the support of bhakti for their fulfillment.” Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj says the same thing:

karm yog aru jñāna saba, sādhana yadapi bakhān

pai binu bhakti sabai janu, mṛitaka deha binu prān (Bhakti Śhatak verse 8) [v8]

“Although karm, jñāna, and aṣhṭāṅg yog are paths to God-realization, without blending bhakti in them, they all become like dead bodies without life-airs.” The various scriptures also declare:

bhaktyāhamekayā grāhyaḥ śhraddhayātmā priyaḥ satām (Bhāgavatam 11.14.21) [v9]

“I am only attained by my devotees who worship me with faith and love.”

milahiṅ na raghupati binu anurāgā, kieṅ joga tapa gyāna birāgā (Ramayan) [v10]

“One may practice aṣhṭāṅg yog, engage in austerities, accumulate knowledge, and develop detachment. Yet, without devotion, one will never attain God.”

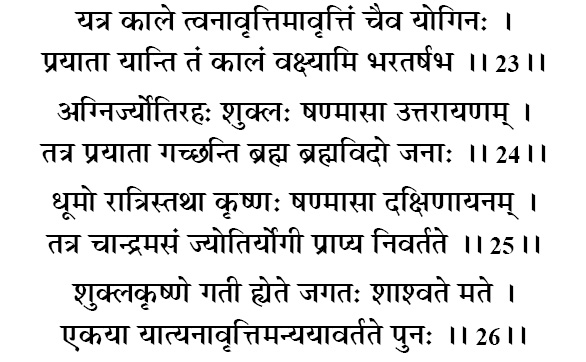

yatra kāle tvanāvṛittim āvṛittiṁ chaiva yoginaḥ

prayātā yānti taṁ kālaṁ vakṣhyāmi bharatarṣhabha

agnir jyotir ahaḥ śhuklaḥ ṣhaṇ-māsā uttarāyaṇam

tatra prayātā gachchhanti brahma brahma-vido janāḥ

dhūmo rātris tathā kṛiṣhṇaḥ ṣhaṇ-māsā dakṣhiṇāyanam

tatra chāndramasaṁ jyotir yogī prāpya nivartate

śhukla-kṛiṣhṇe gatī hyete jagataḥ śhāśhvate mate

ekayā yātyanāvṛittim anyayāvartate punaḥ

yatra—where; kāle—time; tu—certainly; anāvṛittim—no return; āvṛittim—return; cha—and; eva—certainly; yoginaḥ—a yogi; prayātāḥ—having departed; yānti—attain; tam—that; kālam—time; vakṣhyāmi—I shall describe; bharata-ṛiṣhabha—Arjun, the best of the Bharatas; agniḥ—fire; jyotiḥ—light; ahaḥ—day; śhuklaḥ—the bright fortnight of the moon; ṣhaṭ-māsāḥ—six months; uttara-ayanam—the sun’s northern course; tatra—there; prayātāḥ—departed; gachchhanti—go; brahma—Brahman; brahma-vidaḥ—those who know the Brahman; janāḥ—persons; dhūmaḥ—smoke; rātriḥ—night; tathā—and; kṛiṣhṇaḥ—the dark fortnight of the moon; ṣhaṭ-māsāḥ—six months; dakṣhiṇa-ayanam—the sun’s southern course; tatra—there; chāndra-masam—lunar; jyotiḥ—light; yogī—a yogi; prāpya—attain; nivartate—comes back; śhukla—bright; kṛiṣhṇe—dark; gatī—paths; hi—certainly; ete—these; jagataḥ—of the material world; śhāśhvate—eternal; mate—opinion; ekayā—by one; yāti—goes; anāvṛittim—to non return; anyayā—by the other; āvartate—comes back; punaḥ—again.

I shall now describe to you the different paths of passing away from this world, O best of the Bharatas, one of which leads to liberation and the other leads to rebirth. Those who know the Supreme Brahman, and who depart from this world, during the six months of the sun’s northern course, the bright fortnight of the moon, and the bright part of the day, attain the supreme destination. The practitioners of Vedic rituals, who pass away during the six months of the sun’s southern course, the dark fortnight of the moon, the time of smoke, the night, attain the celestial abodes. After enjoying celestial pleasures, they again return to the earth. These two, bright and dark paths, always exist in this world. The way of light leads to liberation and the way of darkness leads to rebirth.

Shree Krishna’s statement in these verses still pertains to the question Arjun asked in verse 8.2, “How can we be united with you at the time of death?” Shree Krishna says that there are two paths—the path of light and the path of darkness. Here, in these somewhat cryptic statements, we may discern a wonderful allegory for expressing spiritual concepts around the themes of light and darkness.

The six months of the northern solstice, the bright fortnight of the moon, the bright part of the day, are all characterized by light. Light is symbolic for knowledge, while darkness is symbolic for ignorance. The six months of the southern solstice, the dark fortnight of the moon, the night, all these have the commonality of darkness. Those, whose consciousness is established in God and detached from sensual pursuits, depart by the path of light (discrimination and knowledge). Being situated in God-consciousness, they attain the Supreme abode of God, and are released from the wheel of samsara. But those, whose consciousness is attached to the world, depart by the path of darkness (ignorance). Being entangled in the bodily concept of life and the illusion of separation from God, they continue rotating in the cycle of life and death. If they had performed Vedic ritualistic activities, they are temporarily promoted to the celestial abodes, and then have to return to the earth planet. In this way, all human beings have to take one of the two paths after death. It now depends upon them, according to their karmas, whether they pass along the bright path or the dark path.

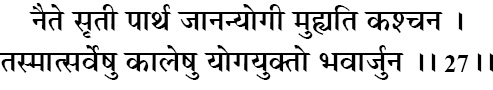

naite sṛitī pārtha jānan yogī muhyati kaśhchana

tasmāt sarveṣhu kāleṣhu yoga-yukto bhavārjuna

na—never; ete—these two; sṛitī—paths; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; jānan—knowing; yogī—a yogi; muhyati—bewildered; kaśhchana—any; tasmāt—therefore; sarveṣhu kāleṣhu—always; yoga-yuktaḥ—situated in Yog; bhava—be; arjuna—Arjun.

Yogis who know the secret of these two paths, O Parth, are never bewildered. Therefore, at all times be situated in Yog (union with God).

Yogis are aspirants who are striving to unite their minds with God. Knowing themselves to be tiny fragments of God, and the futility of a lascivious life, they attach importance to the enhancement of their love for God, rather than the temporary perceptions of sense pleasures. Thus, they are the followers of the path of light. Persons who are deluded by the Maya, thinking of this temporary world as permanent, of their body as the self, and of the miseries of the world as sources of pleasure, follow the path of darkness. The results of both paths are diametrically opposite, one leading to eternal beatitude and the other leading to the continued misery of material existence. Shree Krishna urges Arjun to discriminate between these paths, and become a yogis, thereby following the path of light.

He adds a phrase there, “at all times,” which is very important. Many of us follow the path of light for some time, but then regress to the path of darkness. If someone wishes to go northward, but keeps going four miles south for every mile north, then that person will end up being south of the starting point, despite endeavoring greatly. Similarly, following the path of light for some time in the day does not ensure our progress. We must constantly move ahead in the right direction and stop moving in the wrong direction, only then will we go forward. Hence, Shree Krishna says, “Be a yogi at all times.”

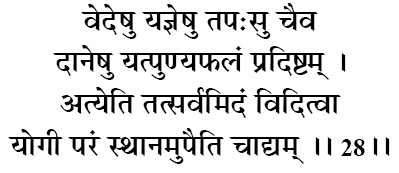

vedeṣhu yajñeṣhu tapaḥsu chaiva

dāneṣhu yat puṇya-phalaṁ pradiṣhṭam

atyeti tat sarvam idaṁ viditvā

yogī paraṁ sthānam upaiti chādyam

vedeṣhu—in the study of the Vedas; yajñeṣhu—in performance of sacrifices; tapaḥsu—in austerities; cha—and; eva—certainly; dāneṣhu—in giving charities; yat—which; puṇya-phalam—fruit of merit; pradiṣhṭam—is gained; atyeti—surpasses; tat sarvam—all; idam—this; viditvā—having known; yogī—a yogi; param—Supreme; sthānam—Abode; upaiti—achieves; cha—and; ādyam—original.

The yogis, who know this secret, gain merit far beyond the fruits of Vedic rituals, the study of the Vedas, performance of sacrifices, austerities, and charities. Such yogis reach the Supreme Abode.

We may perform Vedic sacrifices, accumulate knowledge, perform austerities, and donate in charity, but unless we engage in devotion to God, we are still not on the path of light. All these mundane good deeds result in material rewards, while devotion to God results in liberation from material bondage. Thus, the Ramayan states:

nema dharma āchāra tapa gyāna jagya japa dāna,

bheṣhaja puni koṭinha nahiṅ roga jāhiṅ harijāna. [v11]

“You may engage in good conduct, righteousness, austerities, sacrifices, aṣhṭāṅg yog, chanting of mantras, and charity. But without devotion to God, the mind’s disease of material consciousness will not cease.”

The yogis who follow the path of light detach their mind from the world and attach it to God, thereby gaining eternal welfare. Thus, Shree Krishna says they reap fruits beyond those bestowed by all other processes.