Kṣhetra Kṣhetrajña Vibhāg Yog

Yog through Distinguishing the Field and the Knower of the Field

The Bhagavad Gita consists of eighteen chapters, which are composed of three segments. The first set of six chapters describes karm yog. The second set describes the glories of bhakti, and for the nourishment of bhakti, it also dwells upon the opulences of God. The third set of six chapters expounds upon tattva jñāna (knowledge scriptural terms and principles). The present one is the first of the third set of chapters, and it introduces two terms—kṣhetra (the “field”) and kṣhetrajña (the “knower of the field”). We may think of the field as the body and the knower of the field as the soul that resides within. But this is a simplification, for the field is actually much more—it includes the mind, intellect, and ego, and all other components of the material energy that comprise our personality. In this wider sense, the field of the body encompasses all aspects of our personality, except for the soul who is the “knower the field.”

As a farmer sows seeds in a field and reaps the harvest from it, we sow the field of our body with good or bad thoughts and actions, and reap the consequent destiny. The Buddha had explained: “All that we are is the result of what we have thought; it is founded on our thoughts; and it is made of our thoughts.” Therefore, as we think, that is what we become. The great American thinker, Ralph Waldo Emerson, said: “The ancestor of every action is thought.” Thus, we must learn the art of cultivating the field of our body with appropriate thoughts and actions. This requires knowledge of the distinction between the field and the knower of the field. In the present chapter, Shree Krishna goes into a detailed analysis of this distinction. He enumerates the elements of material nature that compose the field of the body. He describes the modifications that arise in the field, in the form of emotions, sentiments, and feelings. He also mentions the virtues and qualities that purify the field and illumine it with the light of knowledge. Such knowledge helps us gain realization of the soul, who is the knower of the field. The chapter then describes God, who is the supreme knower of the fields of all the living beings. That Supreme Lord holds contradictory attributes, i.e. he possesses opposite qualities at the same time. So, he is all-pervading in creation and yet seated in the hearts of all living beings. He is thus the Supreme Soul of all living beings.

Having described the soul, the Supreme Soul, and material nature, Shree Krishna then explains which of these is responsible for actions by living beings, and also which is responsible for cause and effect in the world at large. Those, who can perceive these distinctions and properly pinpoint the causes of action, are the ones who actually see; and they are the ones who are situated in knowledge. They observe the Supreme Soul present in all living beings, and so they do not degrade themselves by their mind. They can see the variety of living beings situated in the same material nature. And when they see the common spiritual substratum pervading all existence, they attain the realization of Brahman.

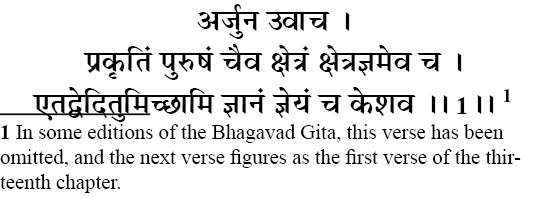

arjuna uvācha

prakṛitiṁ puruṣhaṁ chaiva kṣhetraṁ kṣhetra-jñam eva cha

etad veditum ichchhāmi jñānaṁ jñeyaṁ cha keśhava

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; prakṛitim—material nature; puruṣham—the enjoyer; cha—and; eva—indeed; kṣhetram—the field of activities; kṣhetra-jñam—the knower of the field; eva—even; cha—also; etat—this; veditum—to know; ichchhāmi—I wish; jñānam—knowledge; jñeyam—the goal of knowledge; cha—and; keśhava—Krishna, the killer of the demon named Keshi.

Arjun said, “O Keshav, I wish to understand what are prakṛiti and puruṣh, and what are kṣhetra and kṣhetrajña? I also wish to know what is true knowledge, and what is the goal of this knowledge?

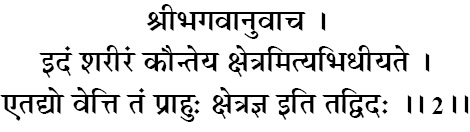

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha

idaṁ śharīraṁ kaunteya kṣhetram ity abhidhīyate

etad yo vetti taṁ prāhuḥ kṣhetra-jña iti tad-vidaḥ

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Supreme Divine Lord said; idam—this; śharīram—body; kaunteya—Arjun, the son of Kunti; kṣhetram—the field of activities; iti—thus; abhidhīyate—is termed as; etat—this; yaḥ—one who; vetti—knows; tam—that person; prāhuḥ—is called; kṣhetra-jñaḥ—the knower of the field; iti—thus; tat-vidaḥ—those who discern the truth.

The Supreme Divine Lord said: O Arjun, this body is termed as kṣhetra (the field of activities), and the one who knows this body is called kṣhetrajña (the knower of the field) by the sages who discern the truth about both.

Here, Shree Krishna begins explaining the topic of distinction between the body and spirit. The soul is divine, and can neither eat, see, smell, hear, taste, nor touch. It vicariously does all these works through the body-mind-intellect mechanism, which is thus termed as the field of activities. In modern science, we have terms like “field of energy.” A magnet has a magnetic field around it, which creates electricity on rapid movement. An electric charge has a force field around it. Here, the body is the receptacle for the activities of the individual. Hence, it is termed as kṣhetra (the field of activities).

The soul is distinct from the body-mind-intellect mechanism, but forgetful of its divine nature, it identifies with these material entities. Yet, because it has knowledge of the body, it is called kṣhetrajña (the knower of the field of the body). This terminology has been given by the self-realized sages, who were transcendentally situated at the platform of the soul, and perceived their distinct identity separate from the body.

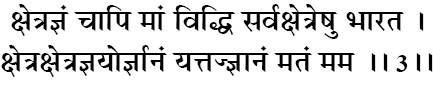

kṣhetra-jñaṁ chāpi māṁ viddhi sarva-kṣhetreṣhu bhārata

kṣhetra-kṣhetrajñayor jñānaṁ yat taj jñānaṁ mataṁ mama

kṣhetra-jñam—the knower of the field; cha—also; api—only; mām—me; viddhi—know; sarva—all; kṣhetreṣhu—in individual fields of activities; bhārata—scion of Bharat; kṣhetra—the field of activities; kṣhetra-jñayoḥ—of the knower of the field; jñānam—understanding of; yat—which; tat—that; jñānam—knowledge; matam—opinion; mama—my.

O scion of Bharat, I am also the knower of all the individual fields of activity. The understanding of the body as the field of activities, and the soul and God as the knowers of the field, this I hold to be true knowledge.

The soul is only the knower of the individual field of its own body. Even in this limited context, the soul’s knowledge of its field is incomplete. God is the knower of the fields of all souls, being situated as the Supreme soul in the heart of all living beings. Further, God’s knowledge of each kṣhetra is perfect and complete. By explaining these distinctions, Shree Krishna establishes the position of the three entities vis-à-vis each other—the material body, the soul, and the Supreme soul.

In the second part of the above verse, he gives his definition of knowledge. “Understanding of the self, the Supreme Lord, the body, and the distinction amongst these, is true knowledge.” In this light, persons with PhDs and DLitts may consider themselves to be erudite, but if they do not understand the distinction between their body, the soul, and God, then according to Shree Krishna’s definition, they are really not knowledgeable.

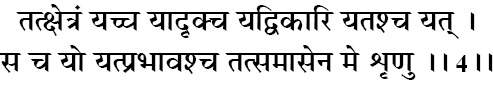

tat kṣhetraṁ yach cha yādṛik cha yad-vikāri yataśh cha yat

sa cha yo yat-prabhāvaśh cha tat samāsena me śhṛiṇu

tat—that; kṣhetram—field of activities; yat—what; cha—and; yādṛik—its nature; cha—and; yat-vikāri—how change takes place in it; yataḥ—from what; cha—also; yat—what; saḥ—he; cha—also; yaḥ—who; yat-prabhāvaḥ—what his powers are; cha—and; tat—that; samāsena—in summary; me—from me; śhṛiṇu—listen.

Listen and I will explain to you what that field is and what its nature is. I will also explain how change takes place within it, from what it was created, who the knower of the field of activities is, and what his powers are.

Shree Krishna now poses many questions himself, and asks Arjun to listen carefully to their answers.

ṛiṣhibhir bahudhā gītaṁ chhandobhir vividhaiḥ pṛithak

brahma-sūtra-padaiśh chaiva hetumadbhir viniśhchitaiḥ

ṛiṣhibhiḥ—by great sages; bahudhā—in manifold ways; gītam—sung; chhandobhiḥ—in Vedic hymns; vividhaiḥ—various; pṛithak—variously; brahma-sūtra—the Brahma Sūtra; padaiḥ—by the hymns; cha—and; eva—especially; hetu-madbhiḥ—with logic; viniśhchitaiḥ—conclusive evidence.

Great sages have sung the truth about the field and the knower of the field in manifold ways. It has been stated in various Vedic hymns, and especially revealed in the Brahma Sūtra, with sound logic and conclusive evidence.

Knowledge is appealing to the intellect when it is expressed with precision and clarity, and is substantiated with sound logic. Further, for it to be accepted as infallible, it must be confirmed on the basis of infallible authority. The reference for validating spiritual knowledge is the Vedas.

Vedas: These are not just the name of some books; they are the eternal knowledge of God. Whenever God creates the world, he manifests the Vedas for the benefit of the souls. The Bṛihadāraṇyak Upaniṣhad (4.5.11) states: niḥśhvasitamasya vedāḥ [v1] “The Vedas manifested from the breath of God.” They were first revealed in the heart of the first-born Brahma. From there, they came down through the oral tradition, and hence, another name for them is Śhruti, or “knowledge received through the ear.” At the beginning of the age of Kali, Ved Vyas, who was himself a descension of God, put down the Vedas in the form of a book, and divided the one body of knowledge into four portions—Ṛig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sāma Veda, and Atharva Veda. Hence, he got the name Ved Vyās, or “one who divided the Vedas.” The distinction must be borne in mind that Ved Vyas is never referred to as the composer of the Vedas but merely the one who divided them. Hence, the Vedas are also called apauruṣheya, which means “not created by any person.” They are respected as the infallible authority for spiritual knowledge.

bhūtaṁ bhavyaṁ bhaviṣhyaṁ cha sarvaṁ vedāt prasidhyati (Manu Smṛiti 12.97) [v2]

“Any spiritual principle must be validated on the authority of the Vedas.” To elaborate this knowledge of the Vedas, many sages wrote texts and these traditionally became included in the gamut of the Vedic scriptures because they conform to the authority of the Vedas. Some of the important Vedic scriptures are listed below.

Itihās: These are historical texts, and are two in number, the Ramayan and the Mahabharat. They describe the history related to two important descensions of God. The Ramayan was written by Sage Valmiki, and describes the leelas, or divine pastimes, of Lord Ram. Amazingly, it was written by Valmiki before Shree Ram actually displayed his leelas. The great poet Sage was empowered with divine vision, by which he could see the pastimes Lord Ram would enact on descending in the world. He thus put them down in 24,000 most beautifully composed Sanskrit verses of the Ramayan. These verses also contain lessons on ideal behavior in various social roles, such as son, brother, wife, king, and married couples. The Ramayan has also been written in many regional languages of India, thereby increasing its popularity amongst the people. The most famous amongst these is the Hindi Ramayan, Ramcharit Manas, written by a great devotee of Lord Ram, Saint Tulsidas.

The Mahabharat was written by Sage Ved Vyas. It contains 100,000 verses and is considered the longest poem in the world. The divine leelas of Lord Krishna are the central theme of the Mahabharat. It is full of wisdom and guidance related to duties in all stages of human life, and devotion to God. The Bhagavad Gita is a portion of the Mahabharat. It is the most popular Hindu scripture, since it contains the essence of spiritual knowledge, so beautifully described by Lord Krishna himself. It has been translated in many different languages of the world. Innumerable commentaries have been written on the Bhagavad Gita.

Puranas: There are eighteen Puranas, written by Sage Ved Vyas. Together, they contain 400,000 verses. These describe the divine pastimes of the various forms of God and his devotees. The Puranas are also full of philosophic knowledge. They discuss the creation of the universe, its annihilation and recreation, the history of humankind, the genealogy of the celestial gods and the holy sages. The most important amongst them is the Bhāgavat Purāṇ, or the Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam. It was the last scripture written by Sage Ved Vyas. In it, he mentions that in this scripture, he is going to reveal the highest dharma of pure selfless love for God. Philosophically, the Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam begins where the Bhagavad Gita ends.

Ṣhaḍ-darśhan: These come next in importance amongst the Vedic scriptures. Six sages wrote six scriptures highlighting particular aspects of Hindu philosophy. These became known as the Shad-darshan, or six philosophic works. They are:

1. Mīmānsā: Written by Maharishi (Sage) Jaimini, it describes ritualistic duties and ceremonies.

2. Vedānt Darśhan: Written by Maharishi Ved Vyas, it discusses the nature of the Absolute Truth.

3. Nyāya Darśhan: Written by Maharishi Gautam, it develops a system of logic for understanding life and the Absolute Truth.

4. Vaiśheṣhik Darshan: Written by Maharishi Kanad, it analyses cosmology and creation from the perspective of its various elements.

5. Yog Darśhan: Written by Maharishi Patañjali, it describes an eightfold path to union with God, beginning with physical postures.

6. Sānkhya Darśhan: Written by Maharishi Kapil, it describes the evolution of the Universe from prakṛiti, the primordial form of the material energy.

Apart from these mentioned above, there are hundreds of other scriptures in the Hindu tradition. It would be impossible to describe them all here. Let it suffice to say that the Vedic scriptures are a vast treasure house of divine knowledge revealed by God and the Saints for the eternal welfare of all humankind.

Amongst these scriptural texts, the Brahma Sūtra (Vedānt Darśhan) is considered as the last word on the topic of the distinction between the soul, the material body, and God. Hence, Shree Krishna particularly mentions it in the above verse. “Ved” refers to the Vedas, and “ant” means “the conclusion.” Consequently, “Vedānt” means “the conclusion of Vedic knowledge.” Although, the Vedānt Darśhan was written by Sage Ved Vyas, many great scholars accepted it as the reference authority for philosophical dissertation and wrote commentaries on it to establish their unique philosophic viewpoint regarding the soul and God. Jagadguru Shankaracharya’s commentary on the Vedānt Darśhan is called Śhārīrak Bhāṣhya, which lays the foundation for the advait-vād tradition of philosophy. Many of his followers, such as Vachaspati and Padmapada have elaborated upon his commentary. Jagadguru Nimbarkarcharya wrote the Vedānt Pārijāta Saurabh, which explains the dwait-advait-vād school of thought. Jagadguru Ramanujacharya’s commentary is called Śhrī Bhāṣhya, which lays the basis for the viśhiṣhṭ-advait-vād system of philosophy. Jagadguru Madhvacharya’s commentary is called Brahma Sūtra Bhāṣhyam, which is the foundation for the dwait-vād school of thought. Mahaprabhu Vallabhacharya wrote Aṇu Bhāṣhya, in which he established the śhuddhadvait-vād system of philosophy. Apart from these, some of the other well-known commentators have been Bhat Bhaskar, Yadav Prakash, Keshav, Nilakanth, Vijnanabhikshu, and Baladev Vidyabhushan.

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, himself a Vedic scholar par excellence, did not write any commentary on the Vedānt Darśhan. He took the view that the writer of the Vedānt, Sage Ved Vyas himself, declared that his final scripture the Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam is its perfect commentary:

arthoyaṁ brahmasūtrāṇaṁ sarvopaniṣhadāmapi [v3]

“The Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam reveals the meaning and the essence of the Vedānt Darśhan and all the Upaniṣhads.” Hence, out of respect for Ved Vyas, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu did not deem it fit to write another commentary on the scripture.

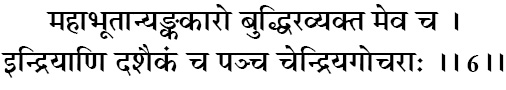

mahā-bhūtāny ahankāro buddhir avyaktam eva cha

indriyāṇi daśhaikaṁ cha pañcha chendriya-gocharāḥ

mahā-bhūtāni—the (five) great elements; ahankāraḥ—the ego; buddhiḥ—the intellect; avyaktam—the unmanifested primordial matter; eva—indeed; cha—and; indriyāṇi—the senses; daśha-ekam—eleven; cha—and; pañcha—five; cha—and; indriya-go-charāḥ—the (five) objects of the senses;

The field of activities is composed of the five great elements, the ego, the intellect, the unmanifest primordial matter, the eleven senses (five knowledge senses, five working senses, and mind), and the five objects of the senses.

The twenty-four elements that constitute the field of activities are: pañcha-mahābhūta (the five gross elements—earth, water, fire, air, and space), the pañch-tanmātrās (five sense objects—taste, touch, smell, sight, and sound), the five working senses (voice, hands, legs, genitals, and anus), the five knowledge senses (ears, eyes, tongue, skin, and nose), mind, intellect, ego, and prakṛiti (the primordial form of the material energy). Shree Krishna uses the word daśhaikaṁ (ten plus one) to indicate the eleven senses. In these, he includes the mind along with the five knowledge senses and the five working senses. Previously, in verse 10.22, he had mentioned that amongst the senses he is the mind.

One may wonder why the five sense objects have been included in the field of activities, when they exist outside the body. The reason is that the mind contemplates upon the sense objects, and these five sense objects reside in a subtle form in the mind. That is why, while sleeping, when we dream with our mind, in our dream state we see, hear, feel, taste, and smell, even though our gross senses are resting on the bed. This illustrates that the gross objects of the senses also exist mentally in the subtle form. Shree Krishna has included them here because he is referring to the entire field of activity for the soul. Some other scriptures exclude the five sense objects while describing the body. Instead, they include the five prāṇas (life-airs). This is merely a matter of classification and not a philosophical difference.

The same knowledge is also explained in terms of sheaths. The field of the body has five kośhas (sheaths) that cover the soul that is ensconced within:

Annamaya kośh. It is the gross sheath, consisting of the five gross elements (earth, water, fire, air, and space).

Prāṇamaya kośh. It is the life-airs sheath, consisting of the five life airs (prāṇ, apān, vyān, samān, and udān).

Manomaya kośh. It is the mental sheath, consisting of the mind and the five working senses (voice, hands, legs, genitals, and anus).

Vijñānamaya kośh. It is the intellectual sheath, consisting of the intellect and the five knowledge senses (ears, eyes, tongue, skin, and nose).

Ānandmaya kośh. It is the bliss sheath, which consists of the ego that makes us identify with the tiny bliss of the body-mind-intellect mechanism.

ichchhā dveṣhaḥ sukhaṁ duḥkhaṁ saṅghātaśh chetanā dhṛitiḥ

etat kṣhetraṁ samāsena sa-vikāram udāhṛitam

ichchhā—desire; dveṣhaḥ—aversion; sukham—happiness; duḥkham—misery; saṅghātaḥ—the aggregate; chetanā—the consciousness; dhṛitiḥ—the will; etat—all these; kṣhetram—the field of activities; samāsena—comprise of; sa-vikāram—with modifications; udāhṛitam—are said.

Desire and aversion, happiness and misery, the body, consciousness, and the will—all these comprise the field and its modifications.

Shree Krishna now elucidates the attributes of the kṣhetra (field), and its modifications thereof:

Body. The field of activities includes the body, but is much more than that. The body undergoes six transformations until death—asti (coming into existence), jāyate (birth), vardhate (growth), viparinamate (reproduction), apakṣhīyate (withering with age), vinaśhyati (death). The body supports the soul in its quest for happiness in the world or in God, as the soul guides it.

Consciousness. It is the life force that exists in the soul, and which it also imparts to the body while it is present in it. This is just as fire has the ability to heat, and if we put an iron rod into it, the rod too becomes red hot with the heat it receives from the fire. Similarly, the soul makes the body seem lifelike by imparting the quality of consciousness in it. Shree Krishna thus includes consciousness as a trait of the field of activities.

Will. This is the determination that keeps the constituent elements of the body active and focused in a particular direction. It is the will that enables the soul to achieve goals through the field of activities. The will is a quality of the intellect, which is energized by the soul. Variations in the will due to the influence of sattva guṇa, rajo guṇa, and tamo guṇa are described in verses 18.33 to 18.35.

Desire. This is a function of the mind and the intellect, which creates a longing for the acquisition of an object, a situation, a person, etc. In discussing the body, we would probably take desire for granted, but imagine how different the nature of life would have been if there were no desires. So the Supreme Lord, who designed the field of activities and included desire as a part of it, naturally makes special mention of it. The intellect analyses the desirability of an object, and the mind harbors its desire. When one becomes self-realized, all material desires are extinguished, and now the purified mind harbors the desire for God. While material desires are the cause of bondage, spiritual desires lead to liberation.

Aversion. It is a state of the mind and intellect that creates revulsion for objects, persons, and situations that are disagreeable to it, and seeks to avoid them.

Happiness. This is a feeling of pleasure that is experienced in the mind through agreeable circumstances and fulfillment of desires. The mind perceives the sensations of happiness, and the soul does so along with it because it identifies with the mind. However, material happiness never satiates the hunger of the soul, which remains discontented until it experiences the infinite divine bliss of God.

Misery. It is the pain experienced in the mind through disagreeable circumstances.

Now Shree Krishna goes on to describe the virtues and attributes that will enable one to cultivate knowledge, and thereby fulfill the purpose of the field of activities, which is human form.

amānitvam adambhitvam ahinsā kṣhāntir ārjavam

āchāryopāsanaṁ śhauchaṁ sthairyam ātma-vinigrahaḥ

indriyārtheṣhu vairāgyam anahankāra eva cha

janma-mṛityu-jarā-vyādhi-duḥkha-doṣhānudarśhanam

asaktir anabhiṣhvaṅgaḥ putra-dāra-gṛihādiṣhu

nityaṁ cha sama-chittatvam iṣhṭāniṣhṭopapattiṣhu

mayi chānanya-yogena bhaktir avyabhichāriṇī

vivikta-deśha-sevitvam aratir jana-sansadi

adhyātma-jñāna-nityatvaṁ tattva-jñānārtha-darśhanam

etaj jñānam iti proktam ajñānaṁ yad ato ’nyathā

amānitvam—humbleness; adambhitvam—freedom from hypocrisy; ahinsā—non-violence; kṣhāntiḥ—forgiveness; ārjavam—simplicity; āchārya-upāsanam—service of the Guru; śhaucham—cleanliness of body and mind; sthairyam—steadfastness; ātma-vinigrahaḥ—self-control; indriya-artheṣhu—toward objects of the senses; vairāgyam—dispassion; anahankāraḥ—absence of egotism; eva cha—and also; janma—of birth; mṛityu—death; jarā—old age; vyādhi—disease; duḥkha—evils; doṣha—faults; anudarśhanam—perception; asaktiḥ—non-attachment; anabhiṣhvaṅgaḥ—absence of craving; putra—children; dāra—spouse; gṛiha-ādiṣhu—home, etc.; nityam—constant; cha—and; sama-chittatvam—even-mindedness; iṣhṭa—the desirable; aniṣhṭa—undesirable; upapattiṣhu—having obtained; mayi—toward me; cha—also; ananya-yogena—exclusively united; bhaktiḥ—devotion; avyabhichāriṇī—constant; vivikta—solitary; deśha—places; sevitvam—inclination for; aratiḥ—aversion; jana-sansadi—for mundane society; adhyātma—spiritual; jñāna—knowledge; nityatvam—constancy; tattva-jñāna—knowledge of spiritual principles; artha—for; darśhanam—philosophy; etat—all this; jñānam—knowledge; iti—thus; proktam—declared; ajñānam—ignorance; yat—what; ataḥ—to this; anyathā—contrary.

Humbleness; freedom from hypocrisy; non-violence; forgiveness; simplicity; service of the Guru; cleanliness of body and mind; steadfastness; and self-control; dispassion toward the objects of the senses; absence of egotism; keeping in mind the evils of birth, disease, old age, and death; non-attachment; absence of clinging to spouse, children, home, and so on; even-mindedness amidst desired and undesired events in life; constant and exclusive devotion toward me; an inclination for solitary places and an aversion for mundane society; constancy in spiritual knowledge; and philosophical pursuit of the Absolute Truth—all these I declare to be knowledge, and what is contrary to it, I call ignorance.

To gain knowledge of the kṣhetra and kṣhetrajña is not merely an intellectual exercise. Unlike bookish knowledge that can be cultivated without a change in one’s character, the spiritual knowledge that Shree Krishna is talking about requires purification of the heart. (Here, heart does not refer to the physical organ. The inner apparatus of mind and intellect is also sometimes referred to as the heart.) These four verses describe the virtues, habits, behaviors, and attitudes that purify one’s life and illuminate it with the light of knowledge.

Humbleness. When we become proud of the attributes of our individual field, such as beauty, intellect, talent, strength, etc. we forget that God has given all these attributes to us. Pride thus results in distancing our consciousness from God. It is a big obstacle on the path of self-realization since it contaminates the entire field by affecting the qualities of the mind and intellect.

Freedom from hypocrisy. The hypocrite develops an artificial external personality. A person is defective from inside, but creates a facade of virtuosity on the outside. Unfortunately, the external display of virtues is skin-deep and hollow.

Non-violence. The cultivation of knowledge requires respect for all living beings. This requires the practice of non-violence. Hence the scriptures state: ātmanaḥ pratikūlāni pareśhāṁ na samācharet [v4] “If you dislike a certain behavior from others, do not behave with them in that manner yourself.”

Forgiveness. It is freedom from ill will even toward those who have harmed one. Actually, harboring ill will harms oneself more than the other. By practicing forgiveness, a person of discrimination releases the negativities in the mind and purifies it.

Simplicity. It is straightforwardness in thought, speech, and action. Straightforwardness in thought includes absence of deceit, envy, crookedness, etc. Straightforwardness in speech includes absence of taunt, censure, gossip, ornamentation, etc. Straightforwardness in action includes plainness in living, forthrightness in behavior, etc.

Service of the Guru. Spiritual knowledge is received from the Guru. This imparting of divine knowledge requires the disciple to have an attitude of dedication and devotion toward the Guru. By serving the Guru, the disciple develops humbleness and commitment that enables the Guru to impart knowledge. Thus, Shree Krishna explained to Arjun in verse 4.34: “Learn the truth by approaching a spiritual master. Inquire from him with reverence and render service unto him. Such an enlightened saint can impart knowledge unto you because he has seen the truth.”

Cleanliness of body and mind. Purity should be both internal and external. The Śhāṇdilya Upaniṣhad states: śhauchaṁ nāma dwividhaṁ-bāhyamāntaraṁ cheti (1.1) [v5] “There are two types of cleanliness—internal and external.” External cleanliness is helpful in maintaining good health, developing discipline, and uncluttering the mind. But mental cleanliness is even more important, and it is achieved by focusing the mind on the all-pure God. Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj states:

māyādhīn malīn mana, hai anādi kālīn,

hari virahānala dhoya jala, karu nirmala bani dīn.

(Bhakti Śhatak verse 79) [v6]

“The material mind is dirty since endless lifetimes. Purify it in the fire of longing for God, while practicing utmost humility.”

Steadfastness. Self-knowledge and God-realization are not goals that are attainable in a day. Steadfastness is the persistence to remain on the path until the goal is reached. The scriptures state: charaivaite charaivate, charan vai madhu vindati [v7] “Keep moving forward. Keep moving forward. Those who do not give up will get the honey at the end.”

Self-control. It is the restraint of the mind and the senses from running after mundane pleasures that dirty the mind and intellect. Self-control prevents the dissipation of the personality through indulgence.

Dispassion toward the objects of the senses. It is a stage higher than the self-control mentioned above, in which we restrain ourselves by force. Dispassion means a lack of taste for sense pleasures that are obstacles on the path of God-realization.

Absence of egotism. Egotism is the conscious awareness of “I,” “me,” and “mine.” This is classified as nescience because it is at the bodily level, arising out of the identification of the self with the body. It is also called the aham chetanā (pride arising out of the sense of self). All mystics emphatically declare that to invite God into our hearts, we must get rid of the pride of the self.

jaba maiṅ thā taba hari nathīṅ, ab hari hai, maiṅ nāhīṅ

prem galī ati sankarī, yā meṅ dwe na samāhīṅ (Saint Kabir) [v8]

“When ‘I’ existed, God was not there; now God exists and ‘I’ do not. The path of divine love is very narrow; it cannot accommodate both ‘I’ and God.”

In the path of jñāna yog and aṣhṭāṅg yog, there are elaborate sādhanās for getting rid of the aham chetanā. But in the path of bhakti yog, it gets eliminated very simply. We add dās (servant) in front of aham (the sense of self), making it dāsoham (I am the servant of God). Now the “I” no longer remains harmful and self-consciousness is replaced by God-consciousness.

Keeping in mind the evils of birth, disease, old-age and death. If the intellect is undecided about what is more important—material enhancement or spiritual wealth—then it becomes difficult to develop the strong will required for acquiring knowledge of the self. But when the intellect is convinced about the unattractiveness of the world, it becomes firm in its resolve. To get this firmness, we should constantly contemplate about the miseries that are an inseparable part of life in the material world. This is what set the Buddha on the spiritual path. He saw a sick person, and thought, “O there is sickness in the world. I will also have to fall sick one day.” Then he saw an old person, and thought, “There is also old age. This means that I will also become old one day.” After that, he saw a dead person, and realized, “This is also a part of existence. It means that I too will have to die one day.” The Buddha’s intellect was so perceptive that one exposure to these facts of life made him renounce worldly existence. Since we do not have such decisive intellects, we must repeatedly contemplate on these facts to allow the unattractiveness of the world to sink in.

Non-attachment. It means dispassion toward the world. We have only one mind and if we wish to engage it in pursuing spiritual goals, we have to detach it from material objects and persons. The sādhak replaces worldly attachment with love and attachment toward God.

Absence of clinging to spouse, children, home, and so on. These are areas where the mind easily becomes attached. In bodily thinking, one spontaneously identifies with the family and home as “mine.” Thus, they linger upon the mind more often and attachment to them shackles the mind to material consciousness. Attachment causes expectations of the kind of behavior we want from family members, and when these expectations are not met, it leads to mental anguish. Also inevitably, there is separation from the family, either temporarily, if they go to another place, or permanently, if they die. All these experiences and their apprehensions begin to weigh heavily upon the mind and drag it away from God. Hence, if we seek immortal bliss, we must practice prudence while interacting with the spouse, child, and home, to prevent the mind from become entangled. We must do our duty toward them, without attachment, as a nurse does her duty in the hospital, or as a teacher does her duty toward her students in the school.

Even-mindedness amidst desired and undesired events in life. Pleasurable and painful events come without invitation, just as the night and the day. That is life. To rise above these dualities, we must learn to enhance our spiritual strength through detachment toward the world. We must develop the ability to remain unperturbed by life’s reversals and also not get carried away with the euphoria of success.

Constant and exclusive devotion toward me. Mere detachment means that the mind is not going in the negative direction. But life is more than merely preventing the undesirable. Life is about engaging in the desirable. The desirable goal of life is to consecrate it at the lotus feet of God. Therefore, Shree Krishna has highlighted it here.

Inclination for solitary places. Unlike worldly people, devotees are not driven by the need for company to overcome feelings of loneliness. They naturally prefer solitude that enables them to engage their mind in communion with God. Hence, they are naturally inclined to choosing solitary places, where they are able to more deeply absorb themselves in devotional thoughts.

Aversion for mundane society. The sign of a materialistic mind is that it finds pleasure in talks about worldly people and worldly affairs. One who is cultivating divine consciousness develops a natural distaste for these activities, and thus avoids mundane society. At the same time, if it is necessary to participate in it for the sake of service to God, the devotee accepts it and develops the strength to remain mentally unaffected by it.

Constancy in spiritual knowledge. To theoretically know something is not enough. One may know that anger is a bad thing but may still give vent to it repeatedly. We have to learn to practically implement spiritual knowledge in our lives. This does not happen by hearing profound truths just once. After hearing them, we must repeatedly contemplate upon them. Such mulling over the divine truths is the constancy in spiritual knowledge that Shree Krishna is talking about.

Philosophical pursuit of the Absolute Truth. Even animals engage in the bodily activities of eating, sleeping, mating, and defending. However, God has especially blessed the human form with the faculty of knowledge. This is not to enable us to engage in bodily activities in a deluxe way, but for us to contemplate upon the questions: “Who am I? Why am I here? What is my goal in life? How was this world created? What is my connection with the Creator? How will I fulfill my purpose in life?” This philosophic pursuit of the truth sublimates our thinking above the animalistic level and brings us to hear and read about the divine science of God-realization.

All the virtues, habits, behaviors, and attitudes described above lead to the growth of wisdom and knowledge. The opposite of these are vanity, hypocrisy, violence, vengeance, duplicity, disrespect for the Guru, uncleanliness of body and mind, unsteadiness, lack of self-control, longing for sense objects, conceit, entanglement in spouse, children, home, etc. Such dispositions cripple the development self-knowledge. Thus, Shree Krishna calls them ignorance and darkness.

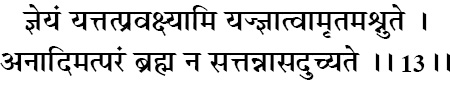

jñeyaṁ yat tat pravakṣhyāmi yaj jñātvāmṛitam aśhnute

anādi mat-paraṁ brahma na sat tan nāsad uchyate

jñeyam—ought to be known; yat—which; tat—that; pravakṣhyāmi—I shall now reveal; yat—which; jñātvā—knowing; amṛitam—immortality; aśhnute—one acheives; anādi—beginningless; mat-param—subordinate to me; brahma—Brahman; na—not; sat—existent; tat—that; na—not; asat—non-existent; uchyate—is called.

I shall now reveal to you that which ought to be known, and by knowing which, one attains immortality. It is the beginningless Brahman, which lies beyond existence and non-existence.

Day and night are like two sides of the same coin for one cannot exist without the other. We can only say it is day in some place if night too falls in that place. But if there is no night, then there is no day either; there is only perpetual light. Similarly, in the case of Brahman, the word “existence” is not descriptive enough. Shree Krishna says that Brahman is beyond the relative terms of existence and non-existence.

The Brahman, in its formless and attributeless aspect, is the object of worship of the jñānīs. In its personal form, as Bhagavān, it is the object of worship of the bhaktas. Residing within the body, it is known as Paramātmā. All these are three manifestations of the same Supreme Reality. Later, in verse 14.27, Shree Krishna states: brahmaṇo hi pratiṣhṭhāham “I am the basis of the formless Brahman.” Thus, the formless Brahman and the personal form of God are both two aspects of the Supreme Entity. Both exist everywhere, and hence they both can be called all-pervading. Referring to these, Shree Krishna reveals the contradictory qualities that manifest in God.

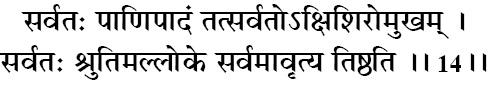

sarvataḥ pāṇi-pādaṁ tat sarvato ’kṣhi-śhiro-mukham

sarvataḥ śhrutimal loke sarvam āvṛitya tiṣhṭhati

sarvataḥ—everywhere; pāṇi—hands; pādam—feet; tat—that; sarvataḥ—everywhere; akṣhi—eyes; śhiraḥ—heads; mukham—faces; sarvataḥ—everywhere; śhruti-mat—having ears; loke—in the universe; sarvam—everything; āvṛitya—pervades; tiṣhṭhati—exists.

Everywhere are his hands and feet, eyes, heads, and faces. His ears too are in all places, for he pervades everything in the universe.

Often people argue that God cannot have hands, feet, eyes, ears, etc. But Shree Krishna says that God has all these, and to an innumerable extent. We should never fall into the trap of circumscribing God within our limited understanding. He is kartumakartuṁ anyathā karatuṁ samarthaḥ “He can do the possible, the impossible, and the reverse of the possible.” For that all-powerful God, to say that he cannot have hands and feet, is placing a constraint upon him.

However, God’s limbs and senses are divine, while ours are material. The difference between the material and the transcendental is that while we are limited to one set of senses, God possesses unlimited hands and legs, eyes, and ears. While our senses exist in one place, God’s senses are everywhere. Hence, God sees everything that happens in the world, and hears everything that is ever said. This is possible because, just as he is all-pervading in creation, his eyes and ears are also ubiquitous. The Chhāndogya Upaniṣhad states: sarvaṁ khalvidaṁ brahma (3.14.1) [v9] “Everywhere is Brahman.” Hence, he accepts food offerings made to him anywhere in the universe; he hears the prayers of his devotees, wherever they may be; and he is the witness of all that occurs in the three worlds. If millions of devotees venerate him at the same time, he has no problem in accepting the prayers of all of them.

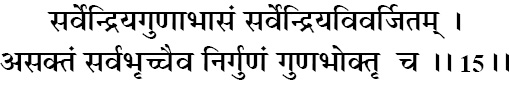

sarvendriya-guṇābhāsaṁ sarvendriya-vivarjitam

asaktaṁ sarva-bhṛich chaiva nirguṇaṁ guṇa-bhoktṛi cha

sarva—all; indriya—senses; guṇa—sense-objects; ābhāsam—the perciever; sarva—all; indriya—senses; vivarjitam—devoid of; asaktam—unattached; sarva-bhṛit—the sustainer of all; cha—yet; eva—indeed; nirguṇam—beyond the three modes of material nature; guṇa-bhoktṛi—the enjoyer of the three modes of material nature; cha—although.

Though he perceives all sense-objects, yet he is devoid of the senses. He is unattached to anything, and yet he is the sustainer of all. Although he is without attributes, yet he is the enjoyer of the three modes of material nature.

Having stated that God’s senses are everywhere, Shree Krishna now states the exact opposite, that he does not possess any senses. If we try to understand this through mundane logic, we will find this contradictory. We will inquire, “How can God have both infinite senses and also be without senses?” However, mundane logic does not apply to him who is beyond the reach of the intellect. God possesses infinite contradictory attributes at the same time. The Brahma Vaivartak Puran states:

viruddha dharmo rūposā vaiśhvaryāt puruṣhottamāh [v10]

“The Supreme Lord is the reservoir of innumerable contradictory attributes.” In this verse, Shree Krishna mentions a few of the infinite contradictory attributes that exist in the personality of God.

He is devoid of mundane senses like ours, and hence it is correct to say that he does not have senses. Sarvendriya vivarjitam means “he is without material senses.” However, he possesses divine senses that are everywhere, consequently, it is also correct to say that the senses of God are in all places. Sarvendriya guṇābhāsaṁ means “he manifests the functions of the senses and grasps the sense objects.” Including both these attributes, the Śhwetāśhvatar Upaniṣhad states:

apāṇipādo javano grahītā paśhyatyachakṣhuḥ sa śhṛiṇotyakarṇaḥ.(3.19) [v11]

“God does not possess material hands, feet, eyes, and ears. Yet he grasps, walks, sees, and hears.”

Further, Shree Krishna states that he is the sustainer of creation, and yet detached from it. In his form as Lord Vishnu, God maintains the entire creation. He sits in the hearts of all living beings, notes their karmas, and gives the results. Under Lord Vishnu’s dominion, Brahma manipulates the laws of material science to ensure that the universe functions stably. Also, under Lord Vishnu’s dominion, the celestial gods arrange to provide the air, earth, water, rain, etc. that are necessary for our survival. Hence, God is the sustainer of all. Yet, he is complete in himself and is, thus, detached from everyone. The Vedas mention him as ātmārām, meaning “one who rejoices in the self and has no need of anything external.”

The material energy is subservient to God, and it works for his pleasure by serving him. He is thus the enjoyer of the three guṇas (modes of material nature). At the same time, he is also nirguṇa (beyond the three guṇas), because these guṇas are material, while God is divine.

bahir antaśh cha bhūtānām acharaṁ charam eva cha

sūkṣhmatvāt tad avijñeyaṁ dūra-sthaṁ chāntike cha tat

bahiḥ—outside; antaḥ—inside; cha—and; bhūtānām—all living beings; acharam—not moving; charam—moving; eva—indeed; cha—and; sūkṣhmatvāt—due to subtlety; tat—he; avijñeyam—incomprehensible; dūra-stham—very far away; cha—and; antike—very near; cha—also; tat—he.

He exists outside and inside all living beings, those that are moving and not moving. He is subtle, and hence, he is incomprehensible. He is very far, but he is also very near.

There is a Vedic Mantra that describes God in practically the same manner as Shree Krishna has described here:

tad ejati tan naijati taddūre tadvantike

tad antar asya sarvasya tadusarvasyāsya bāhyataḥ

(Ishopanishad mantra 5) [v12]

“The Supreme Brahman does not walk, and yet he walks; he is far, but he is also near. He exists inside everything, but he is also outside everything.”

Previously in verse 13.3, Shree Krishna said that to know God is true knowledge. However, here he states that the Supreme Entity is incomprehensible. This again seems to be a contradiction, but what he means is that God is not knowable by the senses, mind, and intellect. The intellect is made from the material energy, so it cannot reach God who is Divine. However, if God himself bestows his grace upon someone, that fortunate soul can come to know him.

avibhaktaṁ cha bhūteṣhu vibhaktam iva cha sthitam

bhūta-bhartṛi cha taj jñeyaṁ grasiṣhṇu prabhaviṣhṇu cha

avibhaktam—indivisible; cha—although; bhūteṣhu—amongst living beings; vibhaktam—divided; iva—apparently; cha—yet; sthitam—situated; bhūta-bhartṛi—the sustainer of all beings; cha—also; tat—that; jñeyam—to be known; grasiṣhṇu—the annihilator; prabhaviṣhṇu—the creator; cha—and.

He is indivisible, yet he appears to be divided amongst living beings. Know the Supreme Entity to be the sustainer, annihilator, and creator of all beings.

God’s personality includes his various energies. All manifest and unmanifest objects are but expansions of his energy. Thus, we can say he is all that exists. Accordingly, Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam states:

dravyaṁ karma cha kālaśh cha svabhāvo jīva eva cha

vāsudevāt paro brahman na chānyo ’rtho ’sti tattvataḥ (2.5.14) [v13]

“The various aspects of creation—time, karma, the natures of individual living beings, and the material ingredients of creation—are all the Supreme Lord Shree Krishna himself. There is nothing in existence apart from him.”

God may appear to be divided amongst the objects of his creation, but since he is all that exists, he remains undivided as well. For example, space may seem to be divided amongst the objects that it contains. Yet, all objects are within the one entity called space, which manifested at the beginning of creation. Again, the reflection of the sun in puddles of water appears divided, and yet the sun remains indivisible.

Just as the ocean throws up waves and then absorbs them back into itself, similarly God creates the world, maintains it, and then absorbs it back into himself. Therefore, he may be equally seen as the Creator, the Maintainer, and the Destroyer of everything.

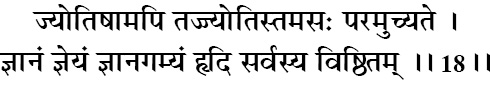

jyotiṣhām api taj jyotis tamasaḥ param uchyate

jñānaṁ jñeyaṁ jñāna-gamyaṁ hṛidi sarvasya viṣhṭhitam

jyotiṣhām—in all luminarie; api—and; tat—that; jyotiḥ—the source of light; tamasaḥ—the darkness; param—beyond; uchyate—is said (to be); jñānam—knowledge; jñeyam—the object of knowledge; jñāna-gamyam—the goal of knowledge; hṛidi—within the heart; sarvasya—of all living beings; viṣhṭhitam—dwells.

He is the source of light in all luminaries, and is entirely beyond the darkness of ignorance. He is knowledge, the object of knowledge, and the goal of knowledge. He dwells within the hearts of all living beings.

Here, Shree Krishna establishes the supremacy of God in different ways. There are various illuminating objects, such as the sun, moon, stars, fire, jewels, etc. Left alone, none of these have any power to illuminate. When God imparts the power to them, only then can they illumine anything. The Vedas say:

tameva bhāntamanubhāti sarvaṁ tasya bhāsā saravamidaṁ vibhāti

(Kaṭhopaniṣhad 2.2.15) [v14]

“God makes all things luminous. It is by his luminosity that all luminous objects give light.”

sūryastapati tejasendraḥ (Vedas) [v15]

“By his radiance, the sun and moon become luminous.” In other words, the luminosity of the sun and the moon is borrowed from God. They may lose their luminosity someday, but God can never lose his.

God has three unique names: Ved-kṛit, Ved-vit, and Ved-vedya. He is Ved-kṛit, which means, “One who manifested the Vedas.” He is Ved-vit, which means, “One who knows the Vedas.” He is also Ved-vedya which means, “One who is to be known through the Vedas.” In the same manner, Shree Krishna describes the Supreme Entity as the jñeya (the object worthy of knowing), jñāna-gamya (the goal of all knowledge), and jñāna (true knowledge).

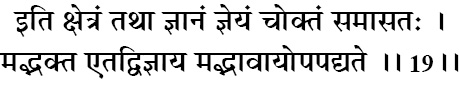

iti kṣhetraṁ tathā jñānaṁ jñeyaṁ choktaṁ samāsataḥ

mad-bhakta etad vijñāya mad-bhāvāyopapadyate

iti—thus; kṣhetram—the nature of the field; tathā—and; jñānam—the meaning of knowledge; jñeyam—the object of knowledge; cha—and; uktam—revealed; samāsataḥ—in summary; mat-bhaktaḥ—my devotee; etat—this; vijñāya—having understood; mat-bhāvāya—my divine nature; upapadyate—attain.

I have thus revealed to you the nature of the field, the meaning of knowledge, and the object of knowledge. Only my devotees can understand this in reality, and by doing so, they attain my divine nature.

Shree Krishna now concludes his description of the field and the object of knowledge, by mentioning the fruit of knowing this topic. However, once again, he deems it fit to bring in devotion, and says that only the bhaktas (devotees) can truly understand this knowledge. Those who practice karm, jñāna, aṣhṭāṅg, etc. devoid of bhakti cannot truly understand the import of the Bhagavad Gita, even though they themselves may think that they do. Bhakti is the essential ingredient in all paths leading to knowledge of God.

Jagadguru Shree Kripaluji Maharaj puts this very nicely:

jo hari sevā hetu ho, soī karm bakhāna

jo hari bhagati baṛhāve, soī samujhiya jñāna (Bhakti Śhatak 66) [v16]

“That work which is done in devotion to God is the real karm; and that knowledge which increases love for God is real knowledge.”

Devotion not only helps us to know God, it also makes the devotee godlike, and hence, Shree Krishna states that the devotees attain his nature. This has been emphasized in the Vedic scriptures again and again. The Vedas state:

bhaktirevainaṁ nayati bhaktirevainaṁ paśhyati bhaktirevainaṁ darśhayati bhakti vaśhaḥ puruṣho bhaktireva bhūyasī (Māṭhar Śhruti) [v17]

“Bhakti alone can lead us to God. Bhakti alone can make us see God. Bhakti alone can bring us in the presence of God. God is under the control of bhakti. Hence, do bhakti exclusively.” Again the Muṇḍakopaniṣhad states:

upāsate puruṣhaṁ ye hyakāmāste śhukrametadativartanti dhīrāḥ (3.2.1) [v18]

“Those who engage in bhakti toward the Supreme Divine Personality, giving up all material desires, escape the cycle of life and death.” Yet again, the Śhwetāśhvatar Upaniṣhad states:

yasya deve parā bhaktiryathā deve tathā gurau

tasyaite kathitā hyarthā prakāśhante mahātmanaḥ (6.23) [v19]

“Those who have unflinching bhakti toward God and identical bhakti toward the Guru, in the hearts of such saintly persons, by the grace of God the imports of the Vedic scriptures are automatically revealed.” The other Vedic Scriptures also reiterate this emphatically:

na sādhayati māṁ yogo na sānkhyaṁ dharma uddhava

na svādhyāyas tapas tyāgo yathā bhaktir mamorjitā (Bhāgavatam 11.14.20) [v20]

Shree Krishna states: “Uddhav, I am not attained by aṣhṭāṅg yog, by the study of sānkhya, cultivation of scriptural knowledge, austerities, nor by renunciation. It is by bhakti alone that I am won over.” In the Bhagavad Gita, Shree Krishna repeatedly states this, in verses 8.22, 11.54, etc. In verse 18.55, he says: “Only by loving devotion does one come to know who I am in truth. Then, having come to know my personality through devotion, one enters my divine realm.” The Ramayan also says:

rāmahi kevala premu piārā, jāni leu jo jānanihārā. [v21]

“The Supreme Lord Ram is only attained through love. Let this truth be known by all who care to know.” Actually, this principle is emphasized in the other religious traditions as well. In the Jewish Torah it is written: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might (Deuteronomy 6.5) [v22]. Jesus of Nazareth repeats this commandment in the Christian New Testament as one of the first and foremost commandments to follow (Mark 12.30)

The Guru Granth Sahib states:

hari sama jaga mahañ vastu nahiṅ, prem panth soñ pantha

sadguru sama sajjan nahīñ, gītā sama nahiñ grantha [v23]

“There is no personality like God; there is no path equal to the path of devotion; there is no human equal to the Guru; and there is no scripture that can compare with the Gita.”

prakṛitiṁ puruṣhaṁ chaiva viddhy anādī ubhāv api

vikārānśh cha guṇānśh chaiva viddhi prakṛiti-sambhavān

prakṛitim—material nature; puruṣham—the individual souls; cha—and; eva—indeed; viddhi—know; anādī—beginningless; ubhau—both; api—and; vikārān—transformations (of the body); cha—also; guṇān—the three modes of nature; cha—and; eva—indeed; viddhi—know; prakṛiti—material energy; sambhavān—produced by.

Know that prakṛiti (material nature) and puruṣh (the individual souls) are both beginningless. Also know that all transformations of the body and the three modes of nature are produced by material energy.

The material nature is called Maya, or prakṛiti. Being an energy of God, it has existed ever since he has existed; in other words, it is eternal. The soul is also eternal, and here it is called puruṣh (the living entity), while God himself is called param puruṣh (the Supreme Living Entity).

The soul is also an expansion of the energy of God. śhaktitvenaivāṁśhatvaṁ vyañjayanti (Paramātma Sandarbh 39) [v24] “The soul is a fragment of the jīva śhakti (soul energy) of God.” While material nature is an insentient energy, the jīva śhakti is a sentient energy. It is divine and intransmutable. It remains unchanged through different lifetimes, and the different stages of each lifetime. The six stages through which the body passes in one lifetime are: asti (existence in the womb), jāyate (birth), vardhate (growth), vipariṇamate (procreation), apakṣhīyate (diminution), vinaśhyati (death). These changes in the body are brought about by the material energy, called prakṛiti, or Maya. It creates the three modes of nature—sattva, rajas, and tamas—and their countless varieties of combinations.

kārya-kāraṇa-kartṛitve hetuḥ prakṛitir uchyate

puruṣhaḥ sukha-duḥkhānāṁ bhoktṛitve hetur uchyate

kārya—effect; kāraṇa—cause; kartṛitve—in the matter of creation; hetuḥ—the medium; prakṛitiḥ—the material energy; uchyate—is said to be; puruṣhaḥ—the individual soul; sukha-duḥkhānām—of happiness and distress; bhoktṛitve—in experiencing; hetuḥ—is responsible; uchyate—is said to be.

In the matter of creation, the material energy is responsible for cause and effect; in the matter of experiencing happiness and distress, the individual soul is declared responsible.

The material energy, with the direction of Brahma, creates myriad elements and forms of life that compose creation. Brahma makes the master plan and the material energy executes it. The Vedas state that there are 8.4 million species of life in the material world. All these bodily forms are transformations of the material energy. Hence, material nature is responsible for all the cause and effect in the world.

The soul gets a bodily form (field of activity) according to its past karmas, and it identifies itself with the body, mind, and intellect. Thus, it seeks the pleasure of the bodily senses. When the senses come in contact with the sense objects, the mind experiences a pleasurable sensation. Since the soul identifies with the mind, it vicariously enjoys that pleasurable sensation. In this way, the soul perceives the sensations of both pleasure and pain, through the medium of the senses, mind, and intellect. This can be compared to a dream state:

ehi bidhi jaga hari āśhrita rahaī, jadapi asatya deta duḥkh ahaī (Ramayan)

jauṅ sapaneṅ sira kāṭai koī, binu jāgeṅ na dūri dukh hoī (Ramayan) [v25]

“The world is sustained by God. It creates an illusion, which, although unreal, gives misery to the soul. This is just like if someone’s head gets cut in a dream, the misery will continue until the person wakes up and stops dreaming.” In this dream state of identifying with the body, the soul experiences pleasure and pain in accordance with its own past and present karmas. As a result, it is said to be responsible for both kinds of experiences.

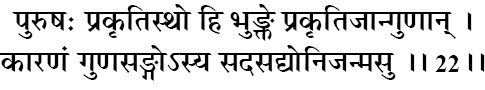

puruṣhaḥ prakṛiti-stho hi bhuṅkte prakṛiti-jān guṇān

kāraṇaṁ guṇa-saṅgo ’sya sad-asad-yoni-janmasu

puruṣhaḥ—the individual soul; prakṛiti-sthaḥ—seated in the material energy; hi—indeed; bhuṅkte—desires to enjoy; prakṛiti-jān—produced by the material energy; guṇān—the three modes of nature; kāraṇam—the cause; guṇa-saṅgaḥ—the attachment (to three guṇas); asya—of its; sat-asat-yoni—in superior and inferior wombs; janmasu—of birth.

When the puruṣh (individual soul) seated in prakṛiti (the material energy) desires to enjoy the three guṇas, attachment to them becomes the cause of its birth in superior and inferior wombs.

In the previous verse, Shree Krishna explained that the puruṣh (soul) is responsible for the experience of pleasure and pain. Now, he explains how this is so. Considering the body to be the self, the soul energizes it into activity that is directed at enjoying bodily pleasures. Since the body is made of Maya, it seeks to enjoy the material energy that is made of the three modes (guṇas)—mode of goodness, mode of passion, and mode of ignorance.

Due to the ego, the soul identifies itself as the doer and the enjoyer of the body. The body, mind, and intellect perform all the activities, but the soul is held responsible for them. Just as when a bus has an accident, the wheels and the steering are not blamed for it; the driver is answerable for any mishap to the bus. Similarly, the senses, mind, and intellect are energized by the soul and they work under its dominion. Hence, the soul accumulates the karmas for all activities performed by the body. This stockpile of karmas, accumulated from innumerable past lives, causes its repeated birth in superior and inferior wombs.

upadraṣhṭānumantā cha bhartā bhoktā maheśhvaraḥ

paramātmeti chāpy ukto dehe ’smin puruṣhaḥ paraḥ

upadraṣhṭā—the witness; anumantā—the permitter; cha—and; bhartā—the supporter; bhoktā—the transcendental enjoyer; mahā-īśhvaraḥ—the ultimate controller; parama-ātmā—Superme Soul; iti—that; cha api—and also; uktaḥ—is said; dehe—within the body; asmin—this; puruṣhaḥ paraḥ—the Supreme Lord.

Within the body also resides the Supreme Lord. He is said to be the witness, the permitter, the supporter, transcendental enjoyer, the ultimate controller, and the Paramātmā (Supreme Soul).

Shree Krishna has explained the status of the jīvātmā (individual soul) within the body. Now in this verse he explains the position of the Paramātmā (Supreme soul), who also resides within the body. He previously mentioned the Paramātmā in verse 13.2 as well, when he stated that the individual soul is the knower of the individual body while the Supreme soul is the knower of all the infinite bodies.

The Supreme soul, who is located within everyone, also manifests in the personal form as Lord Vishnu. The Supreme Lord in his form as Vishnu is responsible for maintaining this creation. He resides in the Kṣhīr Sāgar (the ocean of milk), at the top of the universe in his personal form. He also expands himself to reside in the hearts of all living beings as the Paramātmā. Seated within, he notes their actions, keeps an account of their karmas, and bestows the results at the proper time. He accompanies the jīvātmā (individual soul) to whatever body it receives in each lifetime. He does not hesitate in residing in the body of a snake, a pig, or insect. The Muṇḍakopaniṣhad states:

dvā suparṇā sayujā sakhāyā samānaṁ vṛikṣhaṁ pariṣhasvajāte

tayoranyaḥ pippalaṁ svādvatyanaśhnannanyo

samāne vṛikṣhe puruṣho nimagno ’nīśhayā śhochati muhyamānaḥ

juṣhtaṁ yadā paśhyatyanyamīśhamasya mahimānamiti vītaśhokaḥ (3.1.1-2) [v26]

“Two birds are seated in the nest (heart) of the tree (the body) of the living form. They are the jīvātmā (individual soul) and Paramātmā (Supreme Soul). The jīvātmā has its back toward the Paramātmā, and is busy enjoying the fruits of the tree (the results of the karmas it receives while residing in the body). When a sweet fruit comes, it becomes happy; when a bitter fruit comes, it becomes sad. The Paramātmā is a friend of the jīvātmā, but he does not interfere; he simply sits and watches. If the jīvātmā can only turn around to the Paramātmā, all its miseries will come to an end.” The jīvātmā has been bestowed with free will i.e. the freedom to turn away or toward God. By the improper use of that free will the jīvātmā is in bondage, and by learning its proper usage, it can attain the eternal service of God and experience infinite bliss.

ya evaṁ vetti puruṣhaṁ prakṛitiṁ cha guṇaiḥ saha

sarvathā vartamāno ’pi na sa bhūyo ’bhijāyate

yaḥ—who; evam—thus; vetti—understand; puruṣham—Puruṣh; prakṛitim—the material nature; cha—and; guṇaiḥ—the three modes of nature; saha—with; sarvathā—in every way; vartamānaḥ—situated; api—although; na—not; saḥ—they; bhūyaḥ—again; abhijāyate—take birth.

Those who understand the truth about Supreme Soul, the individual soul, material nature, and the interaction of the three modes of nature will not take birth here again. They will be liberated regardlesss of their present condition.

Ignorance has led the soul into its present predicament. Having forgotten its spiritual identity as a tiny fragment of God, it has fallen into material consciousness. Therefore, knowledge is vital for resurrecting itself from its present position. The Śhwetāśhvatar Upaniṣhad states exactly the same thing:

sanyuktam etat kṣharam akṣharaṁ cha

vyaktāvyaktaṁ bharate viśhwam īśhaḥ

anīśhaśh chātmā badhyate bhoktṛibhāvāj-

jñātvā devaṁ muchyate sarvapāśhaiḥ (1.8) [v27]

“There are three entities in creation—the ever-changing material nature, the unchangeable souls, and the Master of both, who is the Supreme Lord. Ignorance of these entities is the cause of bondage of the soul, while knowledge of them helps it cut asunder the fetters of Maya.”

The knowledge that Shree Krishna is talking about is not just bookish information, but realized wisdom. Realization of knowledge is achieved when we first acquire theoretical knowledge of the three entities from the Guru and the scriptures, and then engage accordingly in spiritual practice. Shree Krishna now talks about some of these spiritual practices in the next verse.

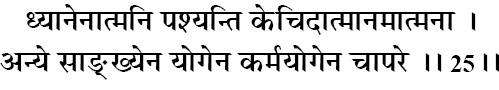

dhyānenātmani paśhyanti kechid ātmānam ātmanā

anye sānkhyena yogena karma-yogena chāpare

dhyānena—through meditation; ātmani—within one’s heart; paśhyanti—percieve; kechit—some; ātmānam—the Supreme soul; ātmanā—by the mind; anye—others; sānkhyena—through cultivation of knowledge; yogena—the yog system; karma-yogena—union with God with through path of action; cha—and; apare—others.

Some try to perceive the Supreme Soul within their hearts through meditation, and others try to do so through the cultivation of knowledge, while still others strive to attain that realization by the path of action.

Variety is the universal characteristic of God’s creation. No two leaves of a tree are alike; no two human beings have exactly the same fingerprints; no two human societies have the same features. Similarly, all souls are unique, and they have their distinctive traits that have been acquired in their unique journey through the cycle of life and death. So in the realm of spiritual practice as well, not all are attracted to the same kind of practice. The beauty of the Bhagavad Gita and the Vedic scriptures is that they realize this inherent variety amongst human beings and accommodate it in their instructions.

Here, Shree Krishna explains that some sādhaks (aspirants) find great joy in grappling with their mind and bringing it under control. They are attracted to meditating upon God seated within their hearts. They relish the spiritual bliss that they experience when their mind comes to rest upon the Lord within them.

Others find satisfaction in exercising their intellect. The idea of the distinction of the soul and the body, mind, intellect, and ego excites them greatly. They relish cultivating knowledge about the three entities—soul, God, and Maya—through the processes of śhravaṇa, manan, nididhyāsan (hearing, contemplating, and internalizing with firm faith).

Yet others find their spirits soaring when they can engage in meaningful action. They strive to engage their God-given abilities in working for him. Nothing satisfies them more than using the last drop of their energy in service of God. In this way, all kinds of sādhaks utilize their individual propensities for realizing the Supreme. The fulfillment of any endeavor involving knowledge, action, love, etc. is when it is combined with devotion for the pleasure of God. The Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam states:

sā vidyā tan-matir yayā (4.29.49) [v28]

“True knowledge is that which helps us develop love for God. The fulfillment of karma occurs when it is done for the pleasure of the Lord.”

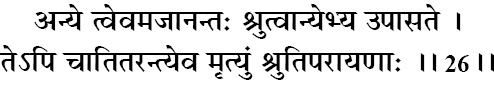

anye tv evam ajānantaḥ śhrutvānyebhya upāsate

te ’pi chātitaranty eva mṛityuṁ śhruti-parāyaṇāḥ

anye—others; tu—still; evam—thus; ajānantaḥ—those who are unaware (of spiritual paths); śhrutvā—by hearing; anyebhyaḥ—from others; upāsate—begin to worship; te—they; api—also; cha—and; atitaranti—cross over; eva—even; mṛityum—death; śhruti-parāyaṇāḥ—devotion to hearing (from saints).

There are still others who are unaware of these spiritual paths, but they hear from others and begin worshipping the Supreme Lord. By such devotion to hearing from saints, they too can gradually cross over the ocean of birth and death.

There are those who are unaware of the methods of sādhanā. But somehow, they hear the knowledge through others, and then get drawn to the spiritual path. In fact, this is usually the case with most people who come to spirituality. They did not have any formal education in spiritual knowledge, but somehow they got the opportunity to hear or read about it. Then their interest in devotion to the Lord developed and they began their journey.

In the Vedic tradition, hearing from the saints has been highly emphasized as a powerful tool for spiritual elevation. In the Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam, King Parikshit asked Shukadev the question: “How can we purify the undesirable entities in our hearts, such as lust, anger, greed, envy, hatred, etc.?” Shukadev replied:

śhṛiṇvatāṁ sva-kathāḥ kṛiṣhṇaḥ puṇya-śhravaṇa-kīrtanaḥ

hṛidy antaḥ stho hy abhadrāṇi vidhunoti suhṛit satām.(Bhāgavatam 1.2.17) [v29]

“Parikshit! Simply hear the descriptions of the divine names, forms, pastimes, virtues, abodes, and saints of God from a Saint. This will naturally cleanse the heart of the unwanted dirt of endless lifetimes.”

When we hear from the proper source, we develop authentic knowledge of spirituality. Besides this, the deep faith of the saint from whom we hear begins to flow into us. Hearing from the saints is the easiest way of building our faith in the spiritual truths. Further, the enthusiasm of the saint for spiritual activity also brushes onto us. Enthusiasm for devotion provides the force that enables the sādhak to shrug aside the inertia of material consciousness and cut through the obstacles on the path of sādhanā. Enthusiasm and faith in the heart are the foundation stones on which the palace of devotion stands.

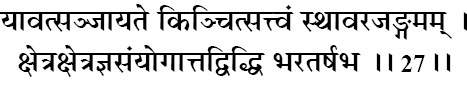

yāvat sañjāyate kiñchit sattvaṁ sthāvara-jaṅgamam

kṣhetra-kṣhetrajña-sanyogāt tad viddhi bharatarṣhabha

yāvat—whatever; sañjāyate—manifesting; kiñchit—anything; sattvam—being; sthāvara—unmoving; jaṅgamam—moving; kṣhetra—field of activities; kṣhetra-jña—knower of the field; sanyogāt—combination of; tat—that; viddhi—know; bharata-ṛiṣhabha—best of the Bharatas.

O best of the Bharatas, whatever moving or unmoving being you see in existence, know it to be a combination of the field of activities and the knower of the field.

Shree Krishna uses the words yāvat kiñchit, meaning “whatsoever form of life that exists,” regardless of how enormous or infinitesimal it may be, is all born of the union of the kṣhetrajña (knower of the field) and the kṣhetra (field of activities). The Abrahamic traditions accept the existence of the soul in humans, but do not accept that other forms of life also have souls. This concept condones violence toward the other life forms. However, the Vedic philosophy stresses that wherever consciousness exists, there must be the presence of the soul. Without it, there can be no consciousness.

In the early twentieth century, Sir J.C. Bose established through experiments that even plants, which are non-moving life forms, can feel and respond to emotions. His experiments proved that soothing music can enhance the growth of plants. When a hunter shoots a bird sitting on a tree, the vibrations of the tree seem to indicate that it weeps for the bird. And when a loving gardener enters the garden, the trees feel joyous. The changes in the vibrations of the tree reveal that it also possesses consciousness and can experience semblances of emotions. These observations corroborate Shree Krishna’s statement here that all life forms possess consciousness; they are the combination of the eternal soul, which is the source of consciousness, and the body, which is made of the insentient material energy.

samaṁ sarveṣhu bhūteṣhu tiṣhṭhantaṁ parameśhvaram

vinaśhyatsv avinaśhyantaṁ yaḥ paśhyati sa paśhyati

samam—equally; sarveṣhu—in all; bhūteṣhu—beings; tiṣhṭhan-tam—accompanying; parama-īśhvaram—Supereme Soul; vinaśhyatsu—amongst the perishable; avinaśhyantam—the imperishable; yaḥ—who; paśhyati—see; saḥ—they; paśhyati—percieve.

They alone truly see, who perceive the Paramātmā (Supreme soul) accompanying the soul in all beings, and who understand both to be imperishable in this perishable body.

Shree Krishna had previously used the expression yaḥ paśhyati sa paśhyati (they alone truly see, who see that…) Now he states that it is not enough to see the presence of the soul within the body. We must also appreciate that God, the Supreme soul, is seated within all bodies. His presence in the heart of all living beings was previously stated in verse 13.23 in this chapter. It is also mentioned in verses 10.20 and 18.61 of the Bhagavad Gita, and in other Vedic scriptures as well:

eko devaḥ sarvabhūteṣhu gūḍhaḥ sarvavyāpī sarvabhūtāntarātmā

(Śhwetāśhvatar Upaniṣhad 6.11) [v30]

“God is one. He resides in the hearts of all living beings. He is omnipresent. He is the supreme soul of all souls.”

bhavān hi sarva-bhūtānām ātmā sākṣhī sva-dṛig vibho (Bhāgavatam 10.86.31) [v31]

“God is seated inside all living beings as the Witness and the Master.”

rām brahma chinamaya abināsī, sarba rahit saba ura pura bāsī (Ramayan) [v32]

“The Supreme Lord Ram is eternal and beyond everything. He resides in the hearts of all living entities.”

The Supreme soul accompanies the individual soul as it journeys from body to body in the cycle of life and death. Shree Krishna now explains how realizing the presence of God in everyone changes the life of the sādhak.

samaṁ paśhyan hi sarvatra samavasthitam īśhvaram

na hinasty ātmanātmānaṁ tato yāti parāṁ gatim

samam—equally; paśhyan—see; hi—indeed; sarvatra—everywhere; samavasthitam—equally present; īśhvaram—God as the Supreme soul; na—do not; hinasti—degrade; ātmanā—by one’s mind; ātmānam—the self; tataḥ—thereby; yāti—reach; parām—the supreme; gatim—destination.

Those, who see God as the Supreme soul equally present everywhere and in all living beings, do not degrade themselves by their mind. Thereby, they reach the supreme destination.

The mind is pleasure seeking by nature and, being a product of the material energy, is spontaneously inclined to material pleasures. If we follow the inclinations of our mind, we become degraded into deeper and deeper material consciousness. The way to prevent this downslide is to keep the mind in check with the help of the intellect. For this, the intellect needs to be empowered with true knowledge.

Those, who learn to see God as the supreme soul present in all beings, begin to live by this knowledge. They no longer seek personal gain and enjoyment in their relationships with others. They neither get attached to others for the good done by them, nor hate them for any harm caused by them. Rather, seeing everyone as a part of God, they maintain a healthy attitude of respect and service toward others. They naturally refrain from mistreating, cheating, or insulting others, when they perceive in them the presence of God. Also, the humanly created distinctions of nationality, creed, caste, sex, status, and color, all become irrelevant. Thus, they elevate their mind by seeing God in all living beings, and finally reach the supreme goal.

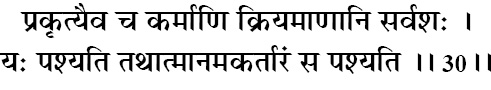

prakṛityaiva cha karmāṇi kriyamāṇāni sarvaśhaḥ

yaḥ paśhyati tathātmānam akartāraṁ sa paśhyati

prakṛityā—by material nature; eva—truly; cha—also; karmāṇi—actions; kriyamāṇāni—are performed; sarvaśhaḥ—all; yaḥ—who; paśhyati—see; tathā—also; ātmānam—(embodied) soul; akartāram—actionless; saḥ—they; paśhyati—see.

They alone truly see who understand that all actions (of the body) are performed by material nature, while the embodied soul actually does nothing.

The Tantra Bhāgavat states: ahankārāt tu samsāro bhavet jīvasya na svataḥ [v33] “The ego of being the body and the pride of being the doer trap the soul in the samsara of life and death.” In material consciousness, the ego makes us identify with the body, and thus we attribute the actions of the body to the soul, and think, “I am doing this…I am doing that.” But the enlightened soul perceives that while eating, drinking, talking, walking, etc. it is only the body that acts. Yet, it cannot shrug the responsibility of the actions performed by the body. Just as the President is responsible for the decision of the country to go to war, although he does not fight in it himself, similarly, the soul is responsible for the actions of a living entity, even though they are performed by the body, mind, and intellect. That is why a spiritual aspirant must keep both sides in mind. Maharishi Vasishth instructed Ram: kartā bahirkartāntarloke vihara rāghava (Yog Vāsiṣhṭh) [v34] “Ram, while working, externally exert yourself as if the results depend upon you; but internally, realize yourself to be the non-doer.”

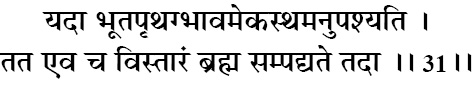

yadā bhūta-pṛithag-bhāvam eka-stham anupaśhyati

tata eva cha vistāraṁ brahma sampadyate tadā

yadā—when; bhūta—living entities; pṛithak-bhāvam—diverse variety; eka-stham—situated in the same place; anupaśhyati—see; tataḥ—thereafter; eva—indeed; cha—and; vistāram—bron from; brahma—Brahman; sampadyate—(they) attain; tadā—then.

When they see the diverse variety of living beings situated in the same material nature, and understand all of them to be born from it, they attain the realization of Brahman.

The ocean modifies itself in many forms such as the wave, froth, tide, ripples, etc. One who is shown all these individually for the first time may conclude that they are all different. But one who has knowledge of the ocean sees the inherent unity in all the variety. Similarly, there are numerous forms of life in existence, from the tiniest amoeba to the most powerful celestial gods. All of them are rooted in the same reality—the soul, which is a part of God, seated in a body, which is made from the material energy. The distinctions between the forms are not due to the soul, but due to the different bodies manifested by the material energy. Upon birth, the bodies of all living beings are created from the material energy, and at death, their bodies again merge into it. When we see the variety of living beings all rooted in the same material nature, we realize the unity behind the diversity. And since material nature is the energy of God, such an understanding makes us see the same spiritual substratum pervading all existence. This leads to the Brahman realization.

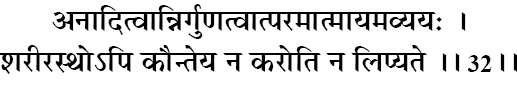

anāditvān nirguṇatvāt paramātmāyam avyayaḥ

śharīra-stho ’pi kaunteya na karoti na lipyate

anāditvāt—being without beginining; nirguṇatvāt—being devoid of any material qualities; parama—the Supreme; ātmā—soul; ayam—this; avyayaḥ—imperishable; śharīra-sthaḥ—dwelling in the body; api—although; kaunteya—Arjun, the the son of Kunti; na—neither; karoti—acts; na—nor; lipyate—is tainted.

The Supreme soul is imperishable, without beginning, and devoid of any material qualities, O son of Kunti. Although situated within the body, it neither acts, nor is it tainted by material energy.

God, situated within the heart of the living being as the Supreme soul, never identifies with the body, nor is affected by its states of existence. His presence in the material body does not make him material in any way, nor is he subject to the law of karma and the cycle of birth and death, though these are experienced by the soul.

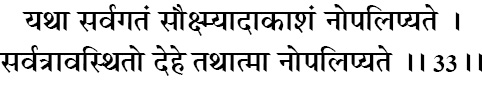

yathā sarva-gataṁ saukṣhmyād ākāśhaṁ nopalipyate

sarvatrāvasthito dehe tathātmā nopalipyate

yathā—as; sarva-gatam—all-pervading; saukṣhmyāt—due to subtlety; ākāśham—the space; na—not; upalipyate—is contaminated; sarvatra—everywhere; avasthitaḥ—situated; dehe—the body; tathā—similarly; ātmā—the soul; na—not; upalipyate—is contaminated.

Space holds everything within it, but being subtle, does not get contaminated by what it holds. Similarly, though its consciousness pervades the body, the soul is not affected by the attributes of the body.

The soul experiences sleep, waking, tiredness, refreshment, etc., due to the ego that makes it identify with the body. One may ask why changes in the body in which it resides do not taint the soul. Shree Krishna explains it with the example of space. It holds everything, but yet remains unaffected, because it is subtler than the gross objects it holds. Similarly, the soul is a subtler energy. It retains its divinity even while it identifies with the material body.

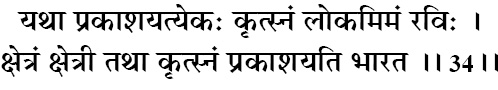

yathā prakāśhayaty ekaḥ kṛitsnaṁ lokam imaṁ raviḥ

kṣhetraṁ kṣhetrī tathā kṛitsnaṁ prakāśhayati bhārata

yathā—as; prakāśhayati—illumines; ekaḥ—one; kṛitsnam—entire; lokam—solar system; imam—this; raviḥ—sun; kṣhetram—the body; kṣhetrī—the soul; tathā—so; kṛitsnam—entire; prakāśhayati—illumine; bhārata—Arjun, the son of Bharat.

Just as one sun illumines the entire solar system, so does the individual soul illumine the entire body (with consciousness).

Although the soul energizes the entire body in which it is present with consciousness, yet by itself, it is exceedingly small. eṣho ’ṇurātmā (Muṇḍakopaniṣhad 3.1.9) [v35] “The soul is very tiny in size.” The Śhwetāśhvatar Upaniṣhad states:

bālāgraśhatabhāgasya śhatadhā kalpitasya cha

bhāgo jīvaḥ sa vijñeyaḥ sa chānantyāya kalpate (5.9) [v36]

“If we divide the tip of a hair into a hundred parts, and then divide each part into further hundred parts, we will get the size of the soul. These souls are innumerable in number.” This is a manner of expressing the minuteness of the soul.

How can such an infinitesimal soul energize the body, which is huge in comparison? Shree Krishna explains this with the analogy of the sun. Although situated in one place, the sun illumines the entire solar system with its light. Likewise, the Vedānt Darśhan states:

guṇādvā lokavat (2.3.25) [v37]

“The soul, although seated in the heart spreads its consciousness throughout the field of the body.”

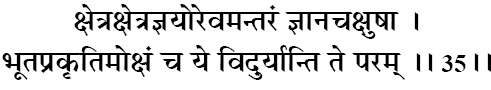

kṣhetra-kṣhetrajñayor evam antaraṁ jñāna-chakṣhuṣhā

bhūta-prakṛiti-mokṣhaṁ cha ye vidur yānti te param