Guṇa Traya Vibhāg Yog

Yog through Understanding the Three Modes of Material Nature

The previous chapter explained in detail the distinction between the soul and the material body. This chapter describes the nature of the material energy, which is the source of the body and its elements, and is thus the origin of both mind and matter. Shree Krishna explains that material nature is constituted of three modes (guṇas)—goodness, passion, and ignorance. The body, mind, and intellect that are made from the material energy also possess these three modes, and the mix of the modes in our being determines the color of our personality. The mode of goodness is characterized by peacefulness, well-being, virtue, and serenity; the mode of passion gives rise to endless desires and insatiable ambitions for worldly enhancement; and the mode of ignorance is the cause for delusion, laziness, intoxication, and sleep. Until the soul attains illumination, it must learn to deal with these three powerful forces of material nature. Liberation lies in transcending all three of these modes.

Shree Krishna reveals a simple solution for breaking out of the bondage of these guṇas. The Supreme Lord is transcendental to the three modes, and if we attach ourselves to him, then our mind will also rise to the divine platform. At this point, Arjun enquires about the characteristics of those who have gone beyond the three guṇas. Shree Krishna then systematically explains the traits of such liberated souls. He explains that illumined persons remain ever equipoised; they are not disturbed when they see the guṇas functioning in the world, and their effects manifesting in persons, objects, and situations. They see everything as a manifestation of God’s energies, which are ultimately in his hands. Thus, worldly situations neither make them jubilant nor miserable, and without wavering, they remain established in the self. The chapter ends with Shree Krishna again reminding us of the power of devotion and its ability to make us transcend the three guṇas.

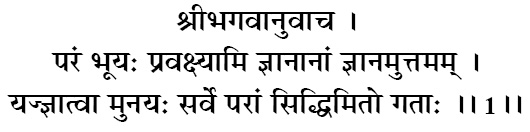

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha

paraṁ bhūyaḥ pravakṣhyāmi jñānānāṁ jñānam uttamam

yaj jñātvā munayaḥ sarve parāṁ siddhim ito gatāḥ

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Divine Lord said; param—supreme; bhūyaḥ—again; pravakṣhyāmi—I shall explain; jñānānām—of all knowledge; jñānam uttamam—the supreme wisdom; yat—which; jñātvā—knowing; munayaḥ—saints; sarve—all; parām—highest; siddhim—perfection; itaḥ—through this; gatāḥ—attained.

The Divine Lord said: I shall once again explain to you the supreme wisdom, the best of all knowledge; by knowing which, all the great saints attained the highest perfection.

In the previous chapter, Shree Krishna had explained that all life forms are a combination of soul and matter. He had also elucidated that prakṛiti (material nature) is responsible for creating the field of activities for the puruṣh (soul). He added that this does not happen independently, but under the direction of the Supreme Lord, who is also seated within the body of the living being. In this chapter, he goes on to elaborate in detail about the three-fold qualities of material nature (the guṇas). By gaining this knowledge and imbibing it into our consciousness as realized wisdom, we can ascend to the highest perfection.

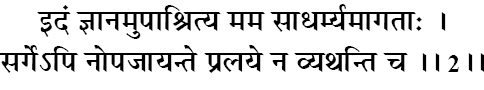

idaṁ jñānam upāśhritya mama sādharmyam āgatāḥ

sarge ’pi nopajāyante pralaye na vyathanti cha

idam—this; jñānam—wisdom; upāśhritya—take refuge in; mama—mine; sādharmyam—of similar nature; āgatāḥ—having attained; sarge—at the time of creation; api—even; na—not; upajāyante—are born; pralaye—at the time of dissolution; na-vyathanti—they will not experience misery; cha—and.

Those who take refuge in this wisdom will be united with me. They will not be reborn at the time of creation nor destroyed at the time of dissolution.

Shree Krishna assures Arjun that those who equip themselves with the knowledge he is about to bestow will no longer have to accept repeated confinement in a mother’s womb. They will also not be obliged to stay in a state of suspended animation in the womb of God at the time of the universal dissolution, or be reborn along with the next creation. The three guṇas (modes of material nature) are indeed the cause of bondage, and knowledge of them will illumine the path out of bondage.

Shree Krishna repeatedly uses the strategy of proclaiming the results of what he is about to teach, to bring his student to rapt attention. The words na vyathanti mean “they will not experience misery.” The word sādharmyam means they will acquire “a similar divine nature” as God himself. When the soul is released from the bondage of the material energy, it comes under the dominion of God’s divine Yogmaya energy. The divine energy equips it with God’s divine knowledge, love, and bliss. As a result, the soul becomes of the nature of God—it acquires divine godlike qualities.

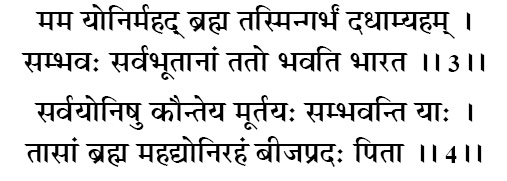

mama yonir mahad brahma tasmin garbhaṁ dadhāmy aham

sambhavaḥ sarva-bhūtānāṁ tato bhavati bhārata

sarva-yoniṣhu kaunteya mūrtayaḥ sambhavanti yāḥ

tāsāṁ brahma mahad yonir ahaṁ bīja-pradaḥ pitā

mama—my; yoniḥ—womb; mahat brahma—the total material substance, prakṛiti; tasmin—in that; garbham—womb; dadhāmi—impregnate; aham—I; sambhavaḥ—birth; sarva-bhūtānām—of all living beings; tataḥ—thereby; bhavati—becomes; bhārata—Arjun, the son of Bharat; sarva—all; yoniṣhu—species of life; kaunteya—Arjun, the son of Kunti; mūrtayaḥ—forms; sambhavanti—are produced; yāḥ—which; tāsām—of all of them; brahma-mahat—great material nature; yoniḥ—womb; aham—I; bīja-pradaḥ—seed-giving; pitā—Father.

The total material substance, prakṛiti, is the womb. I impregnate it with the individual souls, and thus all living beings are born. O son of Kunti, for all species of life that are produced, the material nature is the womb, and I am the seed-giving Father.

As explained in chapters 7 and 8, the material creation follows cycles of creation, maintenance, and dissolution. During dissolution, souls who are vimukh (have their backs) toward God remain in a state of suspended animation within the body of Maha Vishnu. The material energy, prakṛiti, also lies unmanifest in God’s mahodar (big stomach). When he desires to activate the process of creation, he glances at prakṛiti. It then begins to unwind, and sequentially, the entities mahān, ahankār, pañch-tanmātrās, and pañch-mahābhūta are created. Also, with the help of the secondary creator Brahma, the material energy creates various life forms, and God casts the souls into appropriate bodies, determined by their past karmas. Thus, Shree Krishna states that prakṛiti is like the womb and the souls are like the sperms. He places the souls in the womb of Mother Nature to give birth to multitudes of living beings. Sage Ved Vyas also describes it in the same fashion in Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam:

daivāt kṣhubhita-dharmiṇyāṁ svasyāṁ yonau paraḥ pumān

ādhatta vīryaṁ sāsūta mahat-tattvaṁ hiraṇmayam (3.26.19) [v1]

“In the womb of the material energy the Supreme Lord impregnates the souls. Then, inspired by the karmas of the individual souls, the material nature gets to work to create suitable life forms for them.” He does not cast all souls into the material world, rather only those who are vimukh.

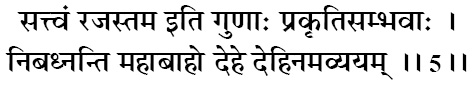

sattvaṁ rajas tama iti guṇāḥ prakṛiti-sambhavāḥ

nibadhnanti mahā-bāho dehe dehinam avyayam

sattvam—mode of goodness; rajaḥ—mode of passion; tamaḥ—mode of ignorance; iti—thus; guṇāḥ—modes; prakṛiti—material nature; sambhavāḥ—consists of; nibadhnanti—bind; mahā-bāho—mighty-armed one; dehe—in the body; dehinam—the embodied soul; avyayam—eternal.

O mighty-armed Arjun, the material energy consists of three guṇas (modes)—sattva (goodness), rajas (passion), and tamas (ignorance). These modes bind the eternal soul to the perishable body.

Having explained that all life-forms are born from puruṣh and prakṛiti, Shree Krishna now explains in the next fourteen verses how prakṛiti binds the soul. Although it is divine, its identification with the body ties it to material nature. The material energy possess three guṇas—goodness, passion, and ignorance. Hence the body, mind, and intellect that are made from prakṛiti also possess these three modes.

Consider the example of three-color printing. If any one of the colors is released in excess by the machine on the paper, then the picture acquires a hue of that color. Similarly, prakṛiti has the ink of the three colors. Based upon one’s internal thoughts, the external circumstances, past sanskārs, and other factors, one or the other of these modes becomes dominant for that person. And the mode that predominates creates its corresponding shade upon that person’s personality. Hence, the soul is swayed by the influence of these dominating modes. Shree Krishna now describes the impact of these modes upon the living being.

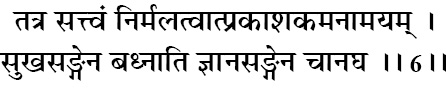

tatra sattvaṁ nirmalatvāt prakāśhakam anāmayam

sukha-saṅgena badhnāti jñāna-saṅgena chānagha

tatra—amongst these; sattvam—mode of goodness; nirmalatvāt—being purest; prakāśhakam—illuminating; anāmayam—healthy and full of well-being; sukha—happiness; saṅgena—attachment; badhnāti—binds; jñāna—knowledge; saṅgena—attachment; cha—also; anagha—Arjun, the sinless one.

Amongst these, sattva guṇa, the mode of goodness, being purer than the others, is illuminating and full of well-being. O sinless one, it binds the soul by creating attachment for a sense of happiness and knowledge.

The word prakāśhakam means “illuminating.” The word anāmayam means “healthy and full of well-being. By extension, it also means “of peaceful quality,” devoid of any inherent cause for pain, discomfort, or misery. The mode of goodness is serene and illuminating. Thus, sattva guṇa engenders virtue in one’s personality and illuminates the intellect with knowledge. It makes a person become calm, satisfied, charitable, compassionate, helpful, serene, and tranquil. It also nurtures good health and freedom from sickness. While the mode of goodness creates an effect of serenity and happiness, attachment to them itself binds the soul to material nature.

Let us understand this through an example. A traveler was passing through a forest, when three robbers attacked him. The first said, “Let us kill him and steal all his wealth.” The second said, “No, let us not kill him. We will simply bind him, and take away his possessions.” Following the advice of the second robber, they tied him up in ropes and stole his wealth. When they had gone some distance away, the third robber returned. He opened the ropes of the traveler, and took him to the edge of the forest. He showed the way out, and said, “I cannot go out myself, but if you follow this path, you will be able to get out of the forest.”

The first robber was tamo guṇa, the mode of ignorance, which literally wants to kill the soul, by degrading it into sloth, languor, and nescience. The second robber was rajo guṇa, the mode of passion, which excites the passions of the living being, and binds the soul in innumerable worldly desires. The third robber was sattva guṇa, the mode of goodness, which reduces the vices of the living being, eases the material discomfort and puts the soul on the path of virtue. Yet, even sattva guṇa is within the realm of material nature. We must not get attached to it; instead, we must use it to step up to the transcendental platform.

Beyond these three, is śhuddha sattva, the transcendental mode of goodness. It is the mode of the divine energy of God that is beyond material nature. When the soul becomes God-realized, by his grace, God bestows śhuddha sattva upon the soul, making the senses, mind, and intellect divine.

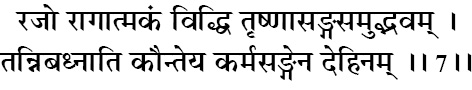

rajo rāgātmakaṁ viddhi tṛiṣhṇā-saṅga-samudbhavam

tan nibadhnāti kaunteya karma-saṅgena dehinam

rajaḥ—mode of passion; rāga-ātmakam—of the nature of passion; viddhi—know; tṛiṣhṇā—desires; saṅga—association; samudbhavam—arises from; tat—that; nibadhnāti—binds; kaunteya—Arjun, the son of Kunti; karma-saṅgena—through attachment to fruitive actions; dehinam—the embodied soul.

O Arjun, rajo guṇa is of the nature of passion. It arises from worldly desires and affections, and binds the soul through attachment to fruitive actions.

Shree Krishna now explains the working of rajo guṇa, and how it binds the soul to material existence. The Patañjali Yog Darśhan describes material activity as the primary manifestation of rajo guṇa. Here, Shree Krishna describes its principal manifestation as attachment and desire.

The mode of passion fuels the lust for sensual enjoyment. It inflames desires for mental and physical pleasures. It also promotes attachment to worldly things. Persons influenced by rajo guṇa get engrossed in worldly pursuits of status, prestige, career, family, and home. They look on these as sources of pleasure and are motivated to undertake intense activity for the sake of these. In this way, the mode of passion increases desires, and these desires further fuel an increase of the mode of passion. They both nourish each other and trap the soul in worldly life.

The way to break out of this is to engage in karm yog, i.e. to begin offering the results of one’s activities to God. This creates detachment from the world, and pacifies the effect of rajo guṇa.

tamas tv ajñāna-jaṁ viddhi mohanaṁ sarva-dehinām

pramādālasya-nidrābhis tan nibadhnāti bhārata

tamaḥ—mode of ignorance; tu—but; ajñāna-jam—born of ignorance; viddhi—know; mohanam—illusion; sarva-dehinām—for all the embodied souls; pramāda—negligence; ālasya—laziness; nidrābhiḥ—and sleep; tat—that; nibadhnāti—binds; bhārata—Arjun, the son of Bharat.

O Arjun, tamo guṇa, which is born of ignorance, is the cause of illusion for the embodied souls. It deludes all living beings through negligence, laziness, and sleep.

Tamo guṇa is the antithesis of sattva guṇa. Persons influenced by it get pleasure through sleep, laziness, intoxication, violence, and gambling. They lose their discrimination of what is right and what is wrong, and do not hesitate in resorting to immoral behavior for fulfilling their self-will. Doing their duty becomes burdensome to them and they neglect it, becoming more inclined to sloth and sleep. In this way, the mode of ignorance leads the soul deeper into the darkness of ignorance. It becomes totally oblivious of its spiritual identity, its goal in life, and the opportunity for progress that the human form provides.

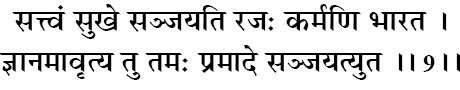

sattvaṁ sukhe sañjayati rajaḥ karmaṇi bhārata

jñānam āvṛitya tu tamaḥ pramāde sañjayaty uta

sattvam—mode of goodness; sukhe—to happiness; sañjayati—binds; rajaḥ—mode of passion; karmaṇi—toward actions; bhārata—Arjun, the son of Bharat; jñānam—wisdom; āvṛitya—clouds; tu—but; tamaḥ—mode of ignorance; pramāde—to delusion; sañjayati—binds; uta—indeed.

Sattva binds one to material happiness; rajas conditions the soul toward actions; and tamas clouds wisdom and binds one to delusion.

In the mode of goodness, the miseries of material existence reduce, and worldly desires become subdued. This gives rise to a feeling of contentment with one’s condition. This is a good thing, but it can have a negative side too. For instance, those who experience pain in the world and are disturbed by the desires in their mind feel impelled to look for a solution to their problems, and this impetus sometimes brings them to the spiritual path. However, those in goodness can easily become complacent and feel no urge to progress to the transcendental platform. Also, sattva guṇa illumines the intellect with knowledge. If this is not accompanied by spiritual wisdom, then knowledge results in pride and that pride comes in the way of devotion to God. This is often seen in the case of scientists, academicians, scholars, etc. The mode of goodness usually predominates in them, since they spend their time and energy cultivating knowledge. And yet, the knowledge they possess often makes them proud, and they begin to feel that there can be no truth beyond the grasp of their intellect. Thus, they find it difficult to develop faith toward either the scriptures or the God-realized Saints.

In the mode of passion, the souls are impelled toward intense activity. Their attachment to the world and preference for pleasure, prestige, wealth, and bodily comforts, propels them to work hard in the world for achieving these goals, which they consider to be the most important in life. Rajo guṇa increases the attraction between man and woman, and generates kām (lust). To satiate that lust, man and woman enter into the relationship of marriage and have a home. The upkeep of the home creates the need for wealth, so they begin to work hard for economic development. They engage in intense activity, but each action creates karmas, which further bind them in material existence.

The mode of ignorance clouds the intellect of the living being. The desire for happiness now manifests in perverse manners. For example, everyone knows that cigarette smoking is injurious to health. Every cigarette pack carries a warning to that extent issued by the government authorities. Cigarette smokers read this, and yet do not refrain from smoking. This happens because the intellect loses its discriminative power and does not hesitate to inflict self-injury to get the pleasure of smoking. As someone jokingly said, “A cigarette is a pipe with a fire at one end and a fool at the other.” That is the influence of tamo guṇa, which binds the soul in the darkness of ignorance.

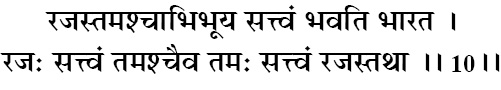

rajas tamaśh chābhibhūya sattvaṁ bhavati bhārata

rajaḥ sattvaṁ tamaśh chaiva tamaḥ sattvaṁ rajas tathā

rajaḥ—mode of passion; tamaḥ—mode of ignorance; cha—and; abhibhūya—prevails; sattvam—mode of goodness; bhavati—becomes; bhārata—Arjun, the son of Bharat; rajaḥ—mode of passion; sattvam—mode of goodness; tamaḥ—mode of ignorance; cha—and; eva—indeed; tamaḥ—mode of ignorance; sattvam—mode of goodness; rajaḥ—mode of passion; tathā—also.

Sometimes goodness (sattva) prevails over passion (rajas) and ignorance (tamas), O scion of Bharat. Sometimes passion (rajas) dominates goodness (sattva) and ignorance (tamas), and at other times ignorance (tamas) overcomes goodness (sattva) and passion (rajas).

Shree Krishna now explains how the same individual’s temperament oscillates amongst the three guṇas. These three guṇas are present in the material energy, and our mind is made from the same energy. Hence, all the three guṇas are present in our mind as well. They can be compared to three wrestlers competing with each other. Each keeps throwing the others down, and so, sometimes the first is on top, sometimes the second, and sometimes the third. In the same manner, the three guṇas keep gaining dominance over the individual’s temperament, which oscillates amongst the three modes. Depending upon the external environment, the internal contemplation, and the sanskārs (tendencies) of past lives, one or the other guṇa begins to dominate. There is no rule for how long it stays—one guṇa may dominate the mind and intellect for as short as a moment or for as long as an hour.

If sattva guṇa dominates, one becomes peaceful, content, generous, kind, helpful, serene, and tranquil. When rajo guṇa gains prominence, one becomes passionate, agitated, ambitious, envious of others success, and develops a gusto for sense pleasures. When tamo guna becomes prominent, one is overcome by sleep, laziness, hatred, anger, resentment, violence, and doubt.

For example, let us suppose you are sitting in your library, engaged in study. There is no worldly disturbance, and your mind has become sāttvic. After finishing your study, you sit in your living room and switch on the television. Seeing all the images makes your mind rājasic, and increases your hankering for sense pleasures. While you are watching your favorite channel, your family member comes and changes the channel. This disturbance causes tamo guṇa to increase in your mind, and you are filled with anger. In this way, the mind sways amongst the three guṇas and adopts their qualities.

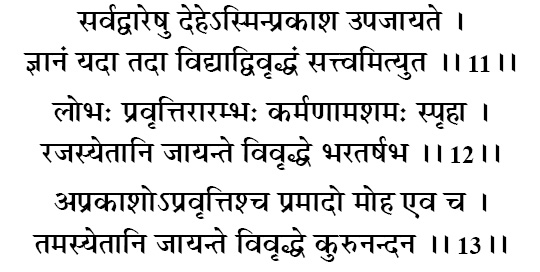

sarva-dvāreṣhu dehe ’smin prakāśha upajāyate

jñānaṁ yadā tadā vidyād vivṛiddhaṁ sattvam ity uta

lobhaḥ pravṛittir ārambhaḥ karmaṇām aśhamaḥ spṛihā

rajasy etāni jāyante vivṛiddhe bharatarṣhabha

aprakāśho ’pravṛittiśh cha pramādo moha eva cha

tamasy etāni jāyante vivṛiddhe kuru-nandana

sarva—all; dvāreṣhu—through the gates; dehe—body; asmin—in this; prakāśhaḥ—illumination; upajāyate—manifest; jñānam—knowledge; yadā—when; tadā—then; vidyāt—know; vivṛiddham—predominates; sattvam—mode of goodness; iti—thus; uta—certainly; lobhaḥ—greed; pravṛittiḥ—activity; ārambhaḥ—exertion; karmaṇām—for fruitive actions; aśhamaḥ—restlessness; spṛihā—craving; rajasi—of the mode of passion; etāni—these; jāyante—develop; vivṛiddhe—when predominates; bharata-ṛiṣhabha— the best of the Bharatas, Arjun; aprakāśhaḥ—nescience; apravṛittiḥ—inertia; cha—and; pramādaḥ—negligence; mohaḥ—delusion; eva—indeed; cha—also; tamasi—mode of ignorance; etāni—these; jāyante—manifest; vivṛiddhe—when dominates; kuru-nandana—the joy of the Kurus, Arjun.

When all the gates of the body are illumined by knowledge, know it to be a manifestation of the mode of goodness. When the mode of passion predominates, O Arjun, the symptoms of greed, exertion for worldly gain, restlessness, and craving develop. O Arjun, nescience, inertia, negligence, and delusion—these are the dominant signs of the mode of ignorance.

Shree Krishna once again repeats how the three modes influence one’s thinking. Sattva guṇa leads to the development of virtues and the illumination of knowledge. Rajo guṇa leads to greed, inordinate activity for worldly attainments, and restlessness of the mind. Tamo guṇa results in delusion of the intellect, laziness, and inclination toward intoxication and violence.

In fact, these modes even influence our attitudes toward God and the spiritual path. To give an example, when the mode of goodness becomes prominent in the mind, we may start thinking, “I have received so much grace from my Guru. I should endeavor to progress rapidly in my sādhanā, since the human form is precious and it should not be wasted in mundane pursuits.” When the mode of passion becomes prominent, we may think, “I must surely progress on the spiritual path, but what is the hurry? At present, I have many responsibilities to discharge, and they are more important.” When the mode of ignorance dominates, we could think, “I am not really sure if there is any God or not, for no one has ever seen him. So why waste time in sādhanā?” Notice how the same person’s thoughts have oscillated from such heights to the depths of devotion.

For the mind to fluctuate due to the three guṇas is very natural. However, we are not to be dejected by this state of affairs, rather, we should understand why it happens and work to rise above it. Sādhanā means to fight with the flow of the three guṇas in the mind, and force it to maintain the devotional feelings toward God and Guru. If our consciousness remained at the highest consciousness all day, there would be no need for sādhanā. Though the mind’s natural sentiments may be inclined toward the world, yet with the intellect, we have to force it into the spiritual realm. Initially, this may seem difficult, but with practice it becomes easy. This is just as driving a car is difficult initially, but with practice it becomes natural.

Shree Krishna now begins to explain the destinations bestowed by the three guṇas, and the need for making it our goal to transcend them.

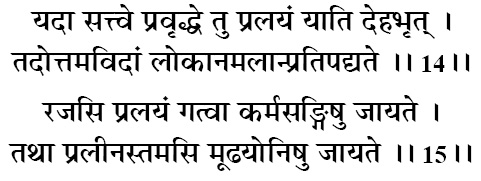

yadā sattve pravṛiddhe tu pralayaṁ yāti deha-bhṛit

tadottama-vidāṁ lokān amalān pratipadyate

rajasi pralayaṁ gatvā karma-saṅgiṣhu jāyate

tathā pralīnas tamasi mūḍha-yoniṣhu jāyate

yadā—when; sattve—in the mode of goodness; pravṛiddhe—when premodinates; tu—indeed; pralayam—death; yāti—reach; deha-bhṛit—the embodied; tadā—then; uttama-vidām—of the learned; lokān—abodes; amalān—pure; pratipadyate—attains; rajasi—in the mode of passion; pralayam—death; gatvā—attaining; karma-saṅgiṣhu—among people driven by work; jāyate—are born; tathā—likewise; pralīnaḥ—dying; tamasi—in the mode of ignorance; mūḍha-yoniṣhu—in the animal kingdom; jāyate—takes birth.

Those who die with predominance of sattva reach the pure abodes (which are free from rajas and tamas) of the learned. Those who die with prevalence of the mode of passion are born among people driven by work, while those dying in the mode of ignorance take birth in the animal kingdom.

Shree Krishna explains that the destiny awaiting the souls is based upon the guṇas of their personalities. We get what we deserve is God’s law, the law of karma. Those who cultivated virtues, knowledge, and a service attitude toward others are born in families of pious people, scholars, social workers, etc. Or else, they go to the higher celestial abodes. Those who permitted themselves to be overcome by greed, avarice, and worldly ambitions are born in families focused on intense material activity, very often the business class. Those who were inclined to intoxication, violence, laziness, and dereliction of duty are born amongst families of drunks and illiterate people. Otherwise, they are made to descend down the evolutionary ladder and are born into the animal species.

Many people wonder whether having once attained the human form, it is possible to slip back into the lower species. This verse reveals that the human form does not remain permanently reserved for the soul. Those who do not put it to good use are subject to the terrible danger of moving downward into the animal forms again. Thus, all the paths are open at all times. The soul can climb upward in its spiritual evolution, remain at the same level, or even slide down, based upon the intensity and frequency of the guṇas it adopts.

karmaṇaḥ sukṛitasyāhuḥ sāttvikaṁ nirmalaṁ phalam

rajasas tu phalaṁ duḥkham ajñānaṁ tamasaḥ phalam

karmaṇaḥ—of action; su-kṛitasya—pure; āhuḥ—is said; sāttvikam—mode of goodness; nirmalam—pure; phalam—result; rajasaḥ—mode of passion; tu—indeed; phalam—result; duḥkham—pain; ajñānam—ignorance; tamasaḥ—mode of ignorance; phalam—result.

It is said the fruit of actions performed in the mode of goodness bestow pure results. Actions done in the mode of passion result in pain, while those performed in the mode of ignorance result in darkness.

Those influenced by sattva are equipped with a measure of purity, virtue, knowledge, and selflessness. Hence, their actions are performed with a relatively pure intention and the results are uplifting and satisfying. Those influenced by rajas are agitated by the desires of their senses and mind. The intention behind their works is primarily self-aggrandizement and sense-gratification for themselves and their dependents. Thus, their works lead to the enjoyment of sense pleasures, which further fuels their sensual desires. Those who are predominated by tamas have no respect for scriptural injunctions and codes of conduct. They commit sinful deeds to relish perverse pleasures, which only result in further immersing them in delusion.

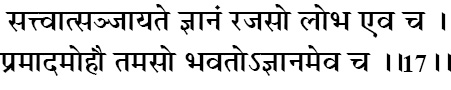

sattvāt sañjāyate jñānaṁ rajaso lobha eva cha

pramāda-mohau tamaso bhavato ’jñānam eva cha

sattvāt—from the mode of goodness; sañjāyate—arises; jñānam—knowledge; rajasaḥ—from the mode of passion; lobhaḥ—greed; eva—indeed; cha—and; pramāda—negligence; mohau—delusion; tamasaḥ—from the mode of ignorance; bhavataḥ—arise; ajñānam—ignorance; eva—indeed; cha—and.

From the mode of goodness arises knowledge, from the mode of passion arises greed, and from the mode of ignorance arise negligence and delusion.

Having mentioned the variation in the results that accrue from the three guṇas, Shree Krishna now gives the reason for this. Sattva guṇa gives rise to wisdom, which confers the ability to discriminate between right and wrong. It also pacifies the desires of the senses for gratification, and creates a concurrent feeling of happiness and contentment. People influenced by it are inclined toward intellectual pursuits and virtuous ideas. Thus, the mode of goodness promotes wise actions. Rajo guṇa inflames the senses, and puts the mind out of control, sending it into a spin of ambitious desires. The living being is trapped by it and over-endeavors for wealth and pleasures that are meaningless from the perspective of the soul. Tamo guṇa covers the living being with inertia and nescience. Shrouded in ignorance, a person performs wicked and impious deeds and bears consequent results.

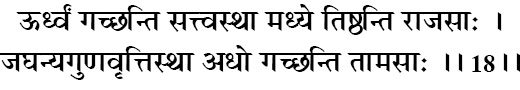

ūrdhvaṁ gachchhanti sattva-sthā madhye tiṣhṭhanti rājasāḥ

jaghanya-guṇa-vṛitti-sthā adho gachchhanti tāmasāḥ

ūrdhvam—upward; gachchhanti—rise; sattva-sthāḥ—those situated in the mode of goodness; madhye—in the middle; tiṣhṭhanti—stay; rājasāḥ—those in the mode of passion; jaghanya—abominable; guṇa—quality; vṛitti-sthāḥ—engaged in activities; adhaḥ—down; gachchhanti—go; tāmasāḥ—those in the mode of ignorance.

Those situated in the mode of goodness rise upward; those in the mode of passion stay in the middle; and those in the mode of ignorance go downward.

Shree Krishna explains that the reincarnation of the souls in their next birth is linked to the guṇas that predominates their personality. Upon completion of their sojourn in the present life, the souls reach the kind of place that corresponds to their guṇas. This can be compared to students applying for college admission after completing school. There are many colleges in the country. Those students with good qualifying criteria at the school level gain admission in the best colleges, while those with poor grades and other scores are admitted to the worst ones. Likewise, the Bhāgavatam says:

sattve pralīnāḥ svar yānti nara-lokaṁ rajo-layāḥ

tamo-layās tu nirayaṁ yānti mām eva nirguṇāḥ (11.25.22) [v2]

“Those who are in sattva guṇa reach the higher celestial abodes; those who are in rajo guṇa return to the earth planet; and those who are in tamo guṇa go to the nether worlds.”

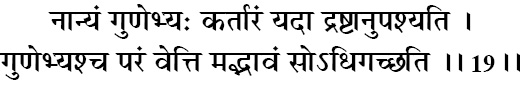

nānyaṁ guṇebhyaḥ kartāraṁ yadā draṣhṭānupaśhyati

guṇebhyaśh cha paraṁ vetti mad-bhāvaṁ so ’dhigachchhati

na—no; anyam—other; guṇebhyaḥ—of the guṇas; kartāram—agents of action; yadā—when; draṣhṭā—the seer; anupaśhyati—see; guṇebhyaḥ—to the modes of nature; cha—and; param—transcendental; vetti—know; mat-bhāvam—my divine nature; saḥ—they; adhigachchhati—attain.

When wise persons see that in all works there are no agents of action other than the three guṇas, and they know me to be transcendental to these guṇas, they attain my divine nature.

Having revealed the complex workings of the three guṇas, Shree Krishna now shows the simple solution for breaking out of their bondage. All the living entities in the world are under the grip of the three guṇas, and hence the guṇas are the active agents in all the works being done in the world. But the Supreme Lord is beyond them. Therefore, he is called tri-guṇātīt (transcendental to the modes of material nature). Similarly, all the attributes of God—his names, forms, virtues, pastimes, abodes, saints—are also tri-guṇātīt.

If we attach our mind to any personality or object within the realm of the three guṇas, it results in increasing their corresponding color on our mind and intellect. However, if we attach our mind to the divine realm, it transcends the guṇas and becomes divine. Those who understand this principle start loosening their relationship with worldly objects and people, and strengthening it, through bhakti, with God and the Guru. This enables them to transcend the three guṇas, and attain the divine nature of God. This is further elaborated in verse 14.26.

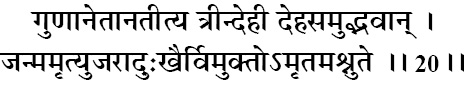

guṇān etān atītya trīn dehī deha-samudbhavān

janma-mṛityu-jarā-duḥkhair vimukto ’mṛitam aśhnute

guṇān—the threre modes of material nature; etān—these; atītya—transcending; trīn—three; dehī—the embodied; deha—body; samudbhavān—produced of; janma—birth; mṛityu—death; jarā—old age; duḥkhaiḥ—misery; vimuktaḥ—freed from; amṛitam—immortality; aśhnute—attains.

By transcending the three modes of material nature associated with the body, one becomes free from birth, disease, old age, and misery, and attains immortality.

If we drink water from a dirty well, we are bound to get a stomach upset. Similarly, if we are influenced by the three modes, we are bound to experience their consequences, which are repeated birth within the material realm, disease, old age, and death. These four are the primary miseries of material life. It was by seeing these that the Buddha first realized that the world is a place of misery, and then searched for the way out of misery.

The Vedas prescribe a number of codes of conduct, social duties, rituals, and regulations for human beings. These prescribed duties and codes of conduct are together called karm dharma, or varṇāśhram dharma, or śhārīrik dharma. They help elevate us from tamo guṇa and rajo guṇa to sattva guṇa. However, to reach sattva guṇa is not enough; it is also a form of bondage. The mode of goodness can be equated to being fettered with chains of gold. Our goal lies even beyond it—to get out of the prison house of material existence.

Shree Krishna explains that when we transcend the three modes, then Maya no longer binds the living being. Thus, the soul gets released from the cycle of life and death and attains immortality. Factually, the soul is always immortal. However, its identification with the material body makes it suffer the illusion of birth and death. This illusory experience is against the eternal nature of the soul, which seeks release from it. Hence, the material illusion is naturally discomforting to our inner being and, from within, we all seek the taste of immortality.

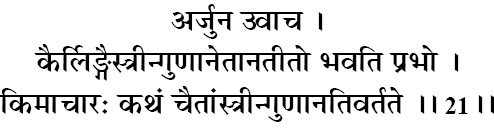

arjuna uvācha

kair liṅgais trīn guṇān etān atīto bhavati prabho

kim āchāraḥ kathaṁ chaitāns trīn guṇān ativartate

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun inquired; kaiḥ—by what; liṅgaiḥ—symptoms; trīn—three; guṇān—modes of material nature; etān—these; atītaḥ—having transcended; bhavati—is; prabho—Lord; kim—what; āchāraḥ—conduct; katham—how; cha—and; etān—these; trīn—three; guṇān—modes of material nature; ativartate—transcend.

Arjun inquired: What are the characteristics of those who have gone beyond the three guṇas, O Lord? How do they act? How do they go beyond the bondage of the guṇas?

Arjun heard from Shree Krishna about transcending the three guṇas. So, now he asks three questions in relation to the guṇas. The word liṅgais means “symptoms.” His first question is: “What are the symptoms of those who have transcended the three guṇas?” The word āchāraḥ means “conduct.” Arjun’s second question is: “In what manner do such transcendentalists conduct themselves?” The word ativartate means “transcend.” The third question he asks is: “How does one transcend the three guṇas?” Shree Krishna answers his questions systematically.

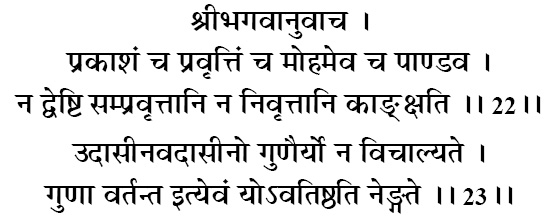

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha

prakāśhaṁ cha pravṛittiṁ cha moham eva cha pāṇḍava

na dveṣhṭi sampravṛittāni na nivṛittāni kāṅkṣhati

udāsīna-vad āsīno guṇair yo na vichālyate

guṇā vartanta ity evaṁ yo ’vatiṣhṭhati neṅgate

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Supreme Divine Personality said; prakāśham—illumination; cha—and; pravṛittim—activity; cha—and; moham—delusion; eva—even; cha—and; pāṇḍava—Arjun, the son of Pandu; na dveṣhṭi—do not hate; sampravṛittāni—when present; na—nor; nivṛittāni—when absent; kāṅkṣhati—longs; udāsīna-vat—neutral; āsīnaḥ—situated; guṇaiḥ—to the modes of material nature; yaḥ—who; na—not; vichālyate—are disturbed; guṇāḥ—modes of material nature; vartante—act; iti-evam—knowing it in this way; yaḥ—who; avatiṣhṭhati—established in the self; na—not; iṅgate—wavering.

The Supreme Divine Personality said: O Arjun, The persons who are transcendental to the three guṇas neither hate illumination (which is born of sattva), nor activity (which is born of rajas), nor even delusion (which is born of tamas), when these are abundantly present, nor do they long for them when they are absent. They remain neutral to the modes of nature and are not disturbed by them. Knowing it is only the guṇas that act, they stay established in the self, without wavering.

Shree Krishna now clarifies the traits of those who have transcended the three guṇas. They are not disturbed when they see the guṇas functioning in the world, and their effects manifesting in persons, objects, and situations around them. Illumined persons do not hate ignorance when they see it, nor get implicated in it. Worldly-minded become overly concerned with the condition of the world. They spend their time and energy brooding about the state of things in the world. The enlightened souls also strive for human welfare, but they do so because it is their nature to help others. At the same time, they realize that the world is ultimately in the hands of God. They simply have to do their duty to the best of their ability, and leave the rest in the hands of God. Having come into God’s world, our first duty is how to purify ourselves. Then, with a pure mind, we will naturally do good and beneficial works in the world, without allowing worldly situations to bear too heavily upon us. As Mahatma Gandhi said: “Be the change that you wish to see in the world.”

Shree Krishna explains that persons of illumination, who know themselves to be transcendental to the functioning of the modes, are neither miserable nor jubilant when the modes of nature perform their natural functions in the world. In fact, even when they perceive these guṇas in their mind, they do not feel disturbed. The mind is made from the material energy, and thus contains the three modes of Maya. So it is natural for the mind to be subjected to the influence of the guṇas, and their corresponding thoughts. The problem is that in bodily consciousness we do not see the mind as different from ourselves. And so, when the mind presents a disturbing thought, we feel, “Oh! I am thinking in this negative manner.” We begin to associate with the poisonous thoughts, allowing them to reside in us and damage us spiritually. To the extent that even if the mind presents a thought against God and Guru, we accept the thought as ours. If, at that time, we could see the mind as separate from us, we would be able to dissociate ourselves from negative thoughts. We would then reject the thoughts of the mind, “I will have nothing to do with any thought that is not conducive to my devotion.” Persons on the transcendental platform have mastered the art of distancing themselves from all negative thoughts arising in the mind from the flow of the guṇas.

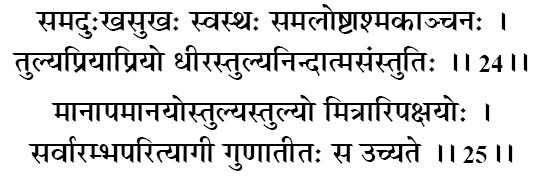

sama-duḥkha-sukhaḥ sva-sthaḥ sama-loṣhṭāśhma-kāñchanaḥ

tulya-priyāpriyo dhīras tulya-nindātma-sanstutiḥ

mānāpamānayos tulyas tulyo mitrāri-pakṣhayoḥ

sarvārambha-parityāgī guṇātītaḥ sa uchyate

sama—alike; duḥkha—distress; sukhaḥ—happiness; sva-sthaḥ—established in the self; sama—equally; loṣhṭa—a clod; aśhma—stone; kāñchanaḥ—gold; tulya—of equal value; priya—pleasant; apriyaḥ—unpleasant; dhīraḥ—steady; tulya—the same; nindā—blame; ātma-sanstutiḥ—praise; māna—honor; apamānayoḥ—dishonor; tulyaḥ—equal; tulyaḥ—equal; mitra—friend; ari—foe; pakṣhayoḥ—to the parties; sarva—all; ārambha—enterprises; parityāgī—renouncer; guṇa-atītaḥ—risen above the three modes of material nature; saḥ—they; uchyate—are said to have.

Those who are alike in happiness and distress; who are established in the self; who look upon a clod, a stone, and a piece of gold as of equal value; who remain the same amidst pleasant and unpleasant events; who are intelligent; who accept both blame and praise with equanimity; who remain the same in honor and dishonor; who treat both friend and foe alike; and who have abandoned all enterprises – they are said to have risen above the three guṇas.

Like God, the soul too is beyond the three guṇas. In bodily consciousness, we identify with the pain and pleasures of the body, and consequently vacillate between the emotions of elation and dejection. But those who are established on the transcendental platform of the self do not identify either with the happiness or the distress of the body. Such self-realized mystics do perceive the dualities of the world but remain unaffected by them. Thus, they become nirguṇa (beyond the influence of the guṇas). This gives them an equal vision, with which they see a piece of stone, a lump of earth, gold, favorable and unfavorable situations, criticisms and glorifications as all the same.

māṁ cha yo ’vyabhichāreṇa bhakti-yogena sevate

sa guṇān samatītyaitān brahma-bhūyāya kalpate

mām—me; cha—only; yaḥ—who; avyabhichāreṇa—unalloyed; bhakti-yogena—through devotion; sevate—serve; saḥ—they; guṇān—the three modes of material nature; samatītya—rise above; etān—these; brahma-bhūyāya—level of Brahman; kalpate—comes to.

Those who serve me with unalloyed devotion rise above the three modes of material nature and come to the level of Brahman.

Having explained the traits of those who are situated beyond the three guṇas, Shree Krishna now reveals the one and only method of transcending these modes of material nature. The above verse indicates that mere knowledge of the self and its distinction with the body is not enough. With the help of bhakti yog, the mind has to be fixed on the Supreme Lord, Shree Krishna. Then alone will the mind become nirguṇa (untouched by the three modes), just as Shree Krishna is nirguṇa.

Many people are of the view that if the mind is fixed upon the personal form of God, it will not rise to the transcendental platform. Only when it is attached to the formless Brahman, will the mind become transcendental to the modes of material nature. However, this verse refutes such a view. Although the personal form of God possesses infinite guṇas (qualities), these are all divine and beyond the modes of material nature. Hence, the personal form of God is also nirguṇa (beyond the three material modes). Sage Ved Vyas explains how the personal form of God is nirguṇa:

yastu nirguṇa ityuktaḥ śhāstreṣhu jagadīśhvaraḥ

prākṛitairheya sanyuktairguṇairhīnatvamuchyate (Padma Purāṇ) [v3]

“Wherever the scriptures refer to God as nirguṇa (without attributes), they mean that he is without material attributes. Nevertheless, his divine personality is not devoid of qualities—he possesses infinite divine attributes.”

This verse also reveals the proper object of meditation. Transcendental meditation does not mean to meditate upon nothingness. The entity transcendental to the three modes of material nature is God. And so, only when the object of our meditation is God can it truly be called transcendental meditation.

brahmaṇo hi pratiṣhṭhāham amṛitasyāvyayasya cha

śhāśhvatasya cha dharmasya sukhasyaikāntikasya cha

brahmaṇaḥ—of Brahman; hi—only; pratiṣhṭhā—the basis; aham—I; amṛitasya—of the immortal; avyayasya—of the imperishable; cha—and; śhāśhvatasya—of the eternal; cha—and; dharmasya—of the dharma; sukhasya—of bliss; aikāntikasya—unending; cha—and.

I am the basis of the formless Brahman, the immortal and imperishable, of eternal dharma, and of unending divine bliss.

The previous verse may give rise to the question about the relationship between Shree Krishna and the formless Brahman. It was previously stated that the all-powerful God has both aspects to his personality—the formless and the personal form. Here, Shree Krishna reveals that the Brahman which the jñānīs worship is the light from the personal form of God. Padma Purāṇ states:

yannakhenduruchirbrahma dheyaṁ brahmādibhiḥ suraiḥ

guṇatrayamatītaṁ taṁ vande vṛindāvaneśhvaram (Patal Khand 77.60) [v4]

“The light that emanates from the toe nails of the feet of the Lord of Vrindavan, Shree Krishna, is the transcendental Brahman that the jñānīs and even the celestial gods meditate upon.” Similarly, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu said:

tāṅhāra aṅgera śhuddha kiraṇa-maṇḍala

upaniṣhat kahe tāṅre brahma sunirmala

(Chaitanya Charitāmṛit, Ādi Leela 2.12) [v5]

“The effulgence emanating from the divine body of God is described by the Upaniṣhads as Brahman.” Thus, in this verse, Shree Krishna unequivocally confirms that the panacea for the disease of the three guṇas is to engage in unwavering devotion to the personal form of the Supreme Lord.