Śhraddhā Traya Vibhāg Yog

Yog through Discerning the Three Divisions of Faith

In the fourteenth chapter, Shree Krishna had explained the three modes of material nature and the manner in which they hold sway over humans. In this seventeenth chapter, he goes into greater detail about the influence of the guṇas. First, he discusses the topic of faith and explains that nobody is devoid of faith, for it is an inseparable aspect of human nature. But depending upon the nature of their mind, people’s faith takes on a corresponding color—sāttvic, rājasic, or tāmasic. The nature of their faith determines the quality of their life. People also prefer food according to their dispositions. Shree Krishna classifies food into three categories and discusses the impact of each of these upon us. He then moves on to the topic of sacrifice (yajña) and how, in each of the three modes of nature, sacrifice takes on different forms. The chapter moves on to the subject of austerity (tapaḥ), and explains austerities of the body, speech, and mind. Each of these kinds of austerity takes on a different form as influenced by the mode of goodness, passion, or ignorance. The topic of charity (dān) is then discussed, and its three-fold divisions are described.

Finally, Shree Krishna goes beyond the three guṇas and explains the relevance and import of the words “Om Tat Sat,” which symbolize different aspects of the Absolute Truth. The syllable “Om” is a symbolic representation of the impersonal aspect of God; the syllable “Tat” is uttered for consecrating activities and ceremonies to the Supreme Lord; the syllable “Sat” means eternal goodness and virtue. Taken together, they usher the concept of transcendence. The chapter concludes by emphasizing the futility of acts of sacrifice, austerity, and charity, which are done without regard to the injunctions of the scriptures.

arjuna uvācha

ye śhāstra-vidhim utsṛijya yajante śhraddhayānvitāḥ

teṣhāṁ niṣhṭhā tu kā kṛiṣhṇa sattvam āho rajas tamaḥ

arjunaḥ uvācha—Arjun said; ye—who; śhāstra-vidhim—scriptural injunctions; utsṛijya—disregard; yajante—worship; śhraddhayā-anvitāḥ—with faith; teṣhām—their; niṣhṭhā—faith; tu—indeed; kā—what; kṛiṣhṇa—Krishna; sattvam—mode of goodness; āho—or; rajaḥ—mode of passion; tamaḥ—mode of ignorance.

Arjun said: O Krishna, where do they stand who disregard the injunctions of the scriptures, but still worship with faith? Is their faith in the mode of goodness, passion, or ignorance?

In the preceding chapter, Shree Krishna spoke of the differences between the divine and demoniac natures, to help Arjun understand the virtues that should be cultivated and personality traits that should be eradicated. At the end of the chapter, he stated that one who disregards the injunctions of the scriptures, and instead foolishly follows the impulses of the body and the whims of the mind, will not achieve perfection, happiness, or freedom from the cycle of life and death. He thus recommended that people follow the guidance of the scriptures and act accordingly. This instruction led to the present question. Arjun desires to know the nature of the faith of those who worship without reference to the Vedic scriptures. In particular, he wishes to understand the answer in terms of the three modes of material nature.

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha

tri-vidhā bhavati śhraddhā dehināṁ sā svabhāva-jā

sāttvikī rājasī chaiva tāmasī cheti tāṁ śhṛiṇu

śhrī-bhagavān uvācha—the Supreme Personality said; tri-vidhā—of three kinds; bhavati—is; śhraddhā—faith; dehinām—embodied beings; sā—which; sva-bhāva-jā—born of one's innate nature; sāttvikī—of the mode of goodness; rājasī—of the mode of passion; cha—and; eva—certainly; tāmasī—of the mode of ignorance; cha—and; iti—thus; tām—about this; śhṛiṇu—hear.

The Supreme Divine Personality said: Every human being is born with innate faith, which can be of three kinds—sāttvic, rājasic, or tāmasic. Now hear about this from me.

Nobody can be without faith, for it is an inseparable aspect of the human personality. Those who do not believe in the scriptures are also not bereft of faith. Their faith is reposed elsewhere. It could be on the logical ability of their intellect, or the perceptions of their senses, or the theories they have decided to believe in. For example, when people say, “I do not believe in God because I cannot see him,” they do not have faith in God but they have faith in their eyes. Hence, they assume that if their eyes cannot see something, it probably does not exist. This is also a kind of faith. Others say, “I do not believe in the authenticity of the ancient scriptures. Instead I accept the theories of modern science.” This is also a kind of faith, for we have seen in the last few centuries how theories of science keep getting amended and overthrown. It is possible that the present scientific theories we believe to be true may also be proved incorrect in the future. Accepting them as truths is also a leap of faith. Prof. Charles H. Townes, Nobel Prize winner in Physics, expressed this very nicely: “Science itself requires faith. We don’t know if our logic is correct. I don’t know if you are there. You don’t know if I am here. We may just be imagining all this. I have a faith that the world is what it seems like, and thus I believe you are there. I can't prove it from any fundamental point of view... Yet I have to accept a certain framework in which to operate. The idea that ‘religion is faith’ and ‘science is knowledge,’ I think, is quite wrong. We scientists believe in the existence of the external world and the validity of our own logic. We feel quite comfortable about it. Nevertheless these are acts of faith. We can't prove them.” Whether one is a material scientist, a social scientist, or a spiritual scientist, one cannot avoid the leap of faith required in the acceptance of knowledge. Shree Krishna now explains the reason why different people choose to place their faith in different places.

sattvānurūpā sarvasya śhraddhā bhavati bhārata

śhraddhā-mayo 'yaṁ puruṣho yo yach-chhraddhaḥ sa eva saḥ

sattva-anurūpā—conforming to the nature of one's mind; sarvasya—all; śhraddhā—faith; bhavati—is; bhārata—Arjun, the scion of Bharat; śhraddhāmayaḥ—possessing faith; ayam—that; puruṣhaḥ—human being; yaḥ—who; yat-śhraddhaḥ—whatever the nature of their faith; saḥ—their; eva—verily; saḥ—they.

The faith of all humans conforms to the nature of their mind. All people possess faith, and whatever the nature of their faith, that is verily what they are.

In the previous verse, it was explained that we all repose our faith somewhere or the other. Where we decide to place our faith and what we choose to believe in practically shapes the direction of our life. Those who develop the conviction that money is of paramount importance in the world spend their entire life accumulating it. Those who believe that fame counts more than anything else dedicate their time and energy in chasing political posts and social designations. Those who believe in noble values sacrifice everything to uphold them. Mahatma Gandhi had faith in the incomparable importance of satya (truth) and ahinsā (non-violence), and by the strength of his convictions he launched a non-violent movement that succeeded in evicting from India the most powerful empire in the world. Those who develop deep faith in the overriding importance of God-realization renounce their material life in search of him. Thus, Shree Krishna states that the quality of our faith decides the direction of our life. In turn, the quality of our faith is decided by the nature of our mind. And so, in response to Arjun’s question, Shree Krishna begins expounding on the kinds of faith that exist.

yajante sāttvikā devān yakṣha-rakṣhānsi rājasāḥ

pretān bhūta-gaṇānśh chānye yajante tāmasā janāḥ

yajante—worship; sāttvikāḥ—those in the mode of goodness; devān—celestial gods; yakṣha—semi-celestial beings who exude power and wealth; rakṣhānsi—powerful beings who embody sensual enjoyment, revenge, and wrath; rājasāḥ—those in the mode of passion; pretān-bhūta-gaṇān—ghosts and spirits; cha—and; anye—others; yajante—worship; tāmasāḥ—those in the mode of ignorance; janāḥ—persons.

Those in the mode of goodness worship the celestial gods; those in the mode of passion worship the yakṣhas and rākṣhasas; those in the mode of ignorance worship ghosts and spirits.

It is said that the good are drawn to the good and the bad to the bad. Those in tamo guṇa are drawn toward ghosts and spirits, despite the evil and cruel nature of such beings. Those who are rājasic get drawn to the yakṣhas (semi-celestial beings who exude power and wealth) and rākṣhasas (powerful beings who embody sensual enjoyment, revenge, and wrath). They even offer the blood of animals to appease these lower beings, with faith in the propriety of such lowly worship. Those who are imbued with sattva guṇa become attracted to the worship of celestial gods in whom they perceive the qualities of goodness. However, worship is perfectly directed when it is offered to God.

aśhāstra-vihitaṁ ghoraṁ tapyante ye tapo janāḥ

dambhāhankāra-sanyuktāḥ kāma-rāga-balānvitāḥ

karṣhayantaḥ śharīra-sthaṁ bhūta-grāmam achetasaḥ

māṁ chaivāntaḥ śharīra-sthaṁ tān viddhy āsura-niśhchayān

aśhāstra-vihitam—not enjoined by the scriptures; ghoram—stern; tapyante—perform; ye—who; tapaḥ—austerities; janāḥ—people; dambha—hypocrisy; ahankāra—egotism; sanyuktāḥ—possessed of; kāma—desire; rāga—attachment; bala—force; anvitāḥ—impelled by; karṣhayantaḥ—torment; śharīra-stham—within the body; bhūta-grāmam—elements of the body; achetasaḥ—senseless; mām—me; cha—and; eva—even; antaḥ—within; śharīra-stham—dwelling in the body; tān—them; viddhi—know; āsura-niśhchayān—of demoniacal resolves.

Some people perform stern austerities that are not enjoined by the scriptures, but rather motivated by hypocrisy and egotism. Impelled by desire and attachment, they torment not only the elements of their body, but also I who dwell within them as the Supreme Soul. Know these senseless people to be of demoniacal resolves.

In the name of spirituality, people perform senseless austerities. Some lie on beds of thorns or drive spikes through their bodies as a part of macabre rituals for dominion over material existence. Others keep one hand raised for years, as a procedure they believe will help them gain mystic abilities. Some gaze constantly at the sun, unmindful of the harm it does to their eyes. Others undertake long fasts, withering their body away for imagined material gains. Shree Krishna says: “O Arjun, you asked me about the status of those who disregard the injunctions of the scriptures and yet worship with faith. I am telling you that faith is visible even in people who perform severe austerities, but it is bereft of a proper basis of knowledge. Such people do possess deep conviction in the efficacy of their practices, but their faith is in the mode of ignorance. Those who abuse and torture their own physical body disrespect the Supreme Soul who resides within. All these are contrary to the recommended path of the scriptures.”

Having described the three categories of faith, Shree Krishna now explains, corresponding to each of these, the categories of food, activities, sacrifice, charity, and so forth.

āhāras tv api sarvasya tri-vidho bhavati priyaḥ

yajñas tapas tathā dānaṁ teṣhāṁ bhedam imaṁ śhṛiṇu

āhāraḥ—food; tu—indeed; api—even; sarvasya—of all; tri-vidhaḥ—of three kinds; bhavati—is; priyaḥ—dear; yajñaḥ—sacrifice; tapaḥ—austerity; tathā—and; dānam—charity; teṣhām—of them; bhedam—distinctions; imam—this; śhṛiṇu—hear.

The food persons prefer is according to their dispositions. The same is true for the sacrifice, austerity, and charity they incline toward. Now hear of the distinctions from me.

The mind and body impact each other. Thus, the food people eat influences their nature and vice versa. The Chhāndogya Upaniṣhad explains that the coarsest part of the food we eat passes out as feces; the subtler part becomes flesh; and the subtlest part becomes the mind (6.5.1). Again, it states: āhāra śhuddhau sattva śhuddhiḥ (7.26.2) [v1] “By eating pure food, the mind becomes pure.” The reverse is also true—people with pure minds prefer pure foods.

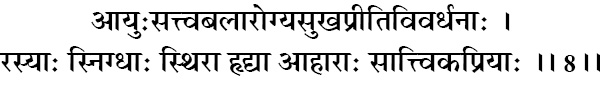

āyuḥ-sattva-balārogya-sukha-prīti-vivardhanāḥ

rasyāḥ snigdhāḥ sthirā hṛidyā āhārāḥ sāttvika-priyāḥ

āyuḥ sattva—which promote longevity; bala—strength; ārogya—health; sukha—happiness; prīti—satisfaction; vivardhanāḥ—increase; rasyāḥ—juicy; snigdhāḥ—succulent; sthirāḥ—nourishing; hṛidyāḥ—pleasing to the heart; āhārāḥ—food; sāttvika-priyāḥ—dear to those in the mode of goodness.

Persons in the mode of goodness prefer foods that promote the life span, and increase virtue, strength, health, happiness, and satisfaction. Such foods are juicy, succulent, nourishing, and naturally tasteful.

In Chapter 14, verse 6, Shree Krishna had explained that the mode of goodness is pure, illuminating, and serene, and creates a sense of happiness and satisfaction. Foods in the mode of goodness have the same effect. In the above verse, these foods are described with the words āyuḥ sattva, meaning “which promote longevity.” They bestow good health, virtue, happiness, and satisfaction. Such foods are juicy, naturally tasteful, mild, and beneficial. These include grains, pulses, beans, fruits, vegetables, milk, and other vegetarian foods.

Hence, a vegetarian diet is beneficial for cultivating the qualities of the mode of goodness that are conducive for spiritual life. Numerous sāttvic (influenced by the mode of goodness) thinkers and philosophers in history have echoed this sentiment:

"Vegetarianism is a greater progress. From the greater clearness of head and quicker apprehension motivated him to become a vegetarian. Flesh-eating is an unprovoked murder." Benjamin Franklin

"Is it not a reproach that man is a carnivorous animal? True, he can and does live, in a great measure, by preying on other animals; but this is a miserable way. I have no doubt that it is a part of the destiny of the human race, in its gradual improvement, to leave off eating animals, as surely as the savage tribes have left off eating each other when they came in contact with the more civilized." Henry David Thoreau in "Walden"

"It is necessary to correct the error that vegetarianism has made us weak in mind, or passive or inert in action. I do not regard flesh-food as necessary at any stage." Mahatma Gandhi.

"O my fellow men, do not defile your bodies with sinful foods. We have corn and we have apples bending down the branches with their weight. There are vegetables that can be cooked and softened over the fire. The earth affords a lavish supply of riches, of innocent foods, and offers you banquets that involve no bloodshed or slaughter; only beasts satisfy their hunger with flesh, and not even all of those, because horses, cattle, and sheep live on grass." Pythagoras

"I do not want to make my stomach a graveyard of dead animals." George Bernard Shaw

Even amongst violence against animals, killing of the cow is particularly heinous. The cow provides milk for human consumption, and so it is like a mother to human beings. To kill the mother cow when it is no longer capable of giving milk is an insensitive, uncultured, and ungrateful act.

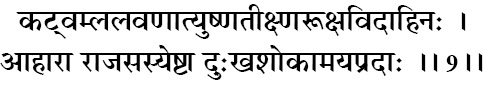

kaṭv-amla-lavaṇāty-uṣhṇa- tīkṣhṇa-rūkṣha-vidāhinaḥ

āhārā rājasasyeṣhṭā duḥkha-śhokāmaya-pradāḥ

kaṭu—bitter; amla—sour; lavaṇa—salty; ati-uṣhṇa—very hot; tīkṣhṇa—pungent; rūkṣha—dry; vidāhinaḥ—chiliful; āhārāḥ—food; rājasasya—to persons in the mode of passion; iṣhṭāḥ—dear; duḥkha—pain; śhoka—grief; āmaya—disease; pradāḥ—produce.

Foods that are too bitter, too sour, salty, very hot, pungent, dry, and chiliful, are dear to persons in the mode of passion. Such foods produce pain, grief, and disease.

When vegetarian foods are cooked with excessive chilies, sugar, salt, etc. they become rājasic. While describing them, the word “very” can be added to all the adjectives used. Thus, rājasic foods are very bitter, very sour, very salty, very hot, very pungent, very dry, very chiliful, etc. They produce ill-health, agitation, and despair. Persons in the mode of passion find such foods attractive, but those in the mode of goodness find them disgusting. The purpose of eating is not to relish bliss through the palate, but to keep the body healthy and strong. As the old adage states: “Eat to live; do not live to eat.” Thus, the wise partake of foods that are conducive to good health, and have a peaceable impact upon the mind i.e., sāttvic foods.

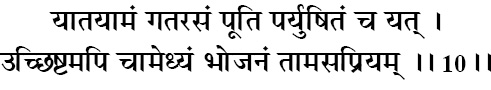

yāta-yāmaṁ gata-rasaṁ pūti paryuṣhitaṁ cha yat

uchchhiṣhṭam api chāmedhyaṁ bhojanaṁ tāmasa-priyam

yāta-yāmam—stale foods; gata-rasam—tasteless; pūti—putrid; paryuṣhitam—polluted; cha—and; yat—which; uchchhiṣhṭam—left over; api—also; cha—and; amedhyam—impure; bhojanam—foods; tāmasa—to persons in the mode of ignorance; priyam—dear.

Foods that are overcooked, stale, putrid, polluted, and impure are dear to persons in the mode of ignorance.

Cooked foods that have remained for more than one yām (three hours) are classified in the mode of ignorance. Foods that are impure, have bad taste, or possess foul smells come in the same category. Impure foods also include all kinds of meat products. Nature has designed the human body to be vegetarian. Human beings do not have long canine teeth as carnivorous animals do, or a wide jaw suitable for tearing flesh. Carnivores have short bowels to allow minimal transit time for the unstable and dead animal food, which putrefies and decays faster. On the contrary, humans have a longer digestive tract for the slow and better absorption of plant food. The stomach of carnivores is more acidic than human beings, which enables them to digest raw meat. Interestingly, the carnivorous animals do not sweat through their pores. Rather, they regulate body temperature through their tongue. On the other hand, herbivorous animals and humans control bodily temperature by sweating through their skin. While drinking, carnivores lap up water rather than suck it. In contrast, herbivores do not lap up water; they suck it. Humans too suck water while drinking; they do not lap it up. All these physical characteristics of the human body reveal that God has not created us as carnivorous creatures, and consequently, meat is considered impure food for humans.

Meat-eating also creates bad karma. The Manu Smṛiti states:

māṁ sa bhakṣhayitāmutra yasya māṁsam ihādmy aham

etan māṁsasya māṁsatvaṁ pravadanti manīṣhiṇaḥ (5.55) [v2]

“The word mānsa (meat) means “that whom I am eating here will eat me in my next life.” For this reason, the learned say that meat is called mānsa (a repeated act: I eat him, he eats me).”

aphalākāṅkṣhibhir yajño vidhi-driṣhṭo ya ijyate

yaṣhṭavyam eveti manaḥ samādhāya sa sāttvikaḥ

aphala-ākāṅkṣhibhiḥ—without expectation of any reward; yajñaḥ—sacrifice; vidhi-driṣhṭaḥ—that is in accordance with the scriptural injunctions; yaḥ—which; ijyate—is performed; yaṣhṭavyam-eva-iti—ought to be offered; manaḥ—mind; samādhāya—with conviction; saḥ—that; sāttvikaḥ—of the nature of goodness.

Sacrifice that is performed according to the scriptural injunctions without expectation of rewards, with the firm conviction of the mind that it is a matter of duty is of the nature of goodness.

The nature of yajña also corresponds to the three guṇas. Shree Krishna begins by explaining the type of sacrifice in the mode of goodness. Aphala-ākāṅkṣhibhiḥ means that the sacrifice should be performed without expectation of any reward. Vidhi driṣhṭaḥ means that it must be done according to the injunctions of the Vedic scriptures. Yaṣhṭavyam evaiti means that it must be performed only for the sake of worship of the Lord, as required by the scriptures. When yajña is performed in this manner, it is classified in the mode of goodness.

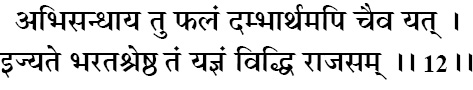

abhisandhāya tu phalaṁ dambhārtham api chaiva yat

ijyate bharata-śhreṣhṭha taṁ yajñaṁ viddhi rājasam

abhisandhāya—motivated by; tu—but; phalam—the result; dambha—pride; artham—for the sake of; api—also; cha—and; eva—certainly; yat—that which; ijyate—is performed; bharata-śhreṣhṭha—Arjun, the best of the Bharatas; tam—that; yajñam—sacrifice; viddhi—know; rājasam—in the mode of passion.

O best of the Bharatas, know that sacrifice, which is performed for material benefit, or with hypocritical aim, to be in the mode of passion.

Sacrifice becomes a form of business with God if it is performed with great pomp and show, but the spirit behind it is one of selfishness i.e., “What will I get in return?” Pure devotion is that where one seeks nothing in return. Shree Krishna says that sacrifice may be done with great ceremony, but if it is for the sake of rewards in the form of prestige, aggrandizement, etc. it is rājasic in nature.

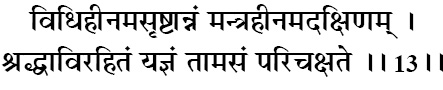

vidhi-hīnam asṛiṣhṭānnaṁ mantra-hīnam adakṣhiṇam

śhraddhā-virahitaṁ yajñaṁ tāmasaṁ parichakṣhate

vidhi-hīnam—without scriptural direction; asṛiṣhṭa-annam—without distribution of prasādam; mantra-hīnam—with no chanting of the Vedic hymns; adakṣhiṇam—with no remunerations to the priests; śhraddhā—faith; virahitam—without; yajñam—sacrifice; tāmasam—in the mode of ignorance; parichakṣhate—is to be considered.

Sacrifice devoid of faith and contrary to the injunctions of the scriptures, in which no food is offered, no mantras chanted, and no donation made, is to be considered in the mode of ignorance.

At every moment in life, individuals have choices regarding which actions to perform. There are proper actions that are beneficial for society and for us. At the same time, there are inappropriate actions that are harmful for others and us. However, who is to decide what is beneficial and what is harmful? And in case a dispute arises, what is the basis for resolving it? If everyone makes their own decisions then pandemonium will prevail. So the injunctions of the scriptures serve as guide maps and wherever a doubt arises, we consult these scriptures for ascertaining the propriety of any action. However, those in the mode of ignorance do not have faith in the scriptures. They carry out religious ceremonies but disregard the ordinances of the scriptures.

In India, specific gods and goddess associated with each festival are worshipped with great pomp and splendor. Often the motive behind the external grandeur of the ceremony—gaudy decorations, dazzling illumination, and blaring music—is to collect contributions from the neighborhood. Further, the Vedic injunction of offering a donation to the priests performing religious ceremony, as a mark of gratitude and respect, is not followed. Sacrifice in which such injunctions of the scriptures are ignored and a self-determined process is followed, due to laziness, indifference, or belligerence, is in the mode of ignorance. Such faith is actually a form of faithlessness in God and the scriptures.

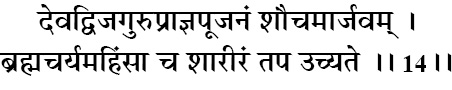

deva-dwija-guru-prājña- pūjanaṁ śhaucham ārjavam

brahmacharyam ahinsā cha śhārīraṁ tapa uchyate

deva—the Supreme Lord; dwija—the Brahmins; guru—the spiritual master; prājña—the elders; pūjanam—worship; śhaucham—cleanliness; ārjavam—simplicity; brahmacharyam—celibacy; ahinsā—non-violence; cha—and; śhārīram—of the body; tapaḥ—austerity; uchyate—is declared as.

Worship of the Supreme Lord, the Brahmins, the spiritual master, the wise, and the elders—when this is done with the observance of cleanliness, simplicity, celibacy, and non-violence—is declared as the austerity of the body.

The word tapaḥ means “to heat up,” e.g. by placing on fire. In the process of purification, metals are heated and melted, so that the impurities may rise to the top and be removed. When gold is placed in the fire, its impurities get burnt and its luster increases. Similarly, the Vedas state: atapta tanurnatadā mośhnute (Rig Veda 9.83.1) [v3] “Without purifying the body through austerity, one cannot reach the final state of yog.” By sincerely practicing austerity, human beings can uplift and transform their lives from the mundane to the divine. Such austerity should be performed without show, with pure intent, in a peaceable manner, in conformance with the guidance of the spiritual master and the scriptures.

Shree Krishna now classifies such austerity into three categories—of the body, speech, and mind. In this verse, he talks of the austerity of the body. When the body is dedicated to the service of the pure and saintly, and all sense indulgence in general, and sexual indulgence in particular, is eschewed, it is acclaimed as austerity of the body. Such austerity should be done with cleanliness, simplicity, and care for not hurting others. Here, “Brahmins” does not refer to those who consider themselves Brahmins by birth, but to those endowed with sāttvic qualities, as described in verse 18.42.

anudvega-karaṁ vākyaṁ satyaṁ priya-hitaṁ cha yat

svādhyāyābhyasanaṁ chaiva vāṅ-mayaṁ tapa uchyate

anudvega-karam—not causing distress; vākyam—words; satyam—truthful; priya- hitam—beneficial; cha—and; yat—which; svādhyāya-abhyasanam—recitation of the Vedic scriptures; cha eva—as well as; vāṅ-mayam—of speech; tapaḥ—austerity; uchyate—are declared as.

Words that do not cause distress, are truthful, inoffensive, and beneficial, as well as the regular recitation of the Vedic scriptures—these are declared as the austerity of speech.

Austerity of speech is speaking words that are truthful, unoffending, pleasing, and beneficial for the listener. The practice of the recitation of Vedic mantras is also included in the austerities of speech. The progenitor, Manu, wrote:

satyaṁ brūyāt priyaṁ brūyān na brūyāt satyam apriyam

priyaṁ cha nānṛitaṁ brūyāt eṣha dharmaḥ sanātanaḥ (Manu Smṛiti 4.138) [v4]

“Speak the truth in such a way that it is pleasing to others. Do not speak the truth in a manner injurious to others. Never speak untruth, though it may be pleasant. This is the eternal path of morality and dharma.”

manaḥ-prasādaḥ saumyatvaṁ maunam ātma-vinigrahaḥ

bhāva-sanśhuddhir ity etat tapo mānasam uchyate

manaḥ-prasādaḥ—serenity of thought; saumyatvam—gentleness; maunam—silence; ātma-vinigrahaḥ—self-control; bhāva-sanśhuddhiḥ—purity of purpose; iti—thus; etat—these; tapaḥ—austerity; mānasam—of the mind; uchyate—are declared as.

Serenity of thought, gentleness, silence, self-control, and purity of purpose—all these are declared as the austerity of the mind.

Austerity of the mind is higher than the austerity of body and speech, for if we learn to master the mind, the body and speech automatically get mastered, while the reverse is not necessarily true. Factually, the state of the mind determines the state of an individual’s consciousness. Shree Krishna had stated in verse 6.5, “Elevate yourself through the power of your mind and not degrade yourself, for the mind can be the friend and also the enemy of the self.”

The mind may be likened to a garden, which can either be intelligently cultivated or allowed to run wild. Gardeners cultivate their plot, growing fruits, flowers, and vegetables in it. At the same time, they also ensure that it remains free from weeds. Similarly, we must cultivate our own mind with rich and noble thoughts, while weeding out the negative and debilitating thoughts. If we allow resentful, hateful, blaming, unforgiving, critical, and condemning thoughts to reside in our mind, they will have a debilitating effect on our personality. We can never get a fair amount of constructive action out of the mind until we have learned to control it and keep it from becoming stimulated by anger, hatred, dislike, etc. These are the weeds that choke out the manifestation of divine grace within our hearts.

People imagine that their thoughts are secret and have no external consequences because they dwell within the mind, away from the sight of others. They do not realize that thoughts not only forge their inner character but also their external personality. That is why we look upon someone and say, “He seems like a very simple and trustworthy person.” For another person, we say, “She seems to be very cunning and deceitful. Stay away from her.” In each case, it was the thoughts people harbored that sculpted their appearance. Ralph Waldo Emerson said: “There is full confession in the glances of our eyes, in our smiles, in salutations, in the grasp of the hands. Our sin bedaubs us, mars all the good impressions. Men do not know why they do not trust us. The vice glasses the eyes, demeans the cheek, pinches the nose, and writes, ‘O fool, fool!’ on the forehead of a king.” Another powerful saying linking thoughts to character states:

“Watch your thoughts, for they become words.

Watch your words, for they become actions.

Watch your actions, for they become habits.

Watch your habits, for they become character.

Watch your character, for it becomes your destiny.”

It is important to realize that we harm ourselves with every negative thought that we harbor in our mind. At the same time, we uplift ourselves with every positive thought that we dwell upon. Henry Van Dyke expressed this very vividly, in his poem “Thoughts are things.”

I hold it true that thoughts are things;

They’re endowed with bodies and breath and wings

That which we call our secret thought

Speeds forth to earth’s remotest spot,

Leaving its blessings or its woes,

Like tracks behind as it goes.

We build our future, thought by thought.

For good or ill, yet know it not,

Choose, then, thy destiny and wait,

For love brings love, and hate brings hate.

Each thought we dwell upon has consequences, and thought-by-thought, we forge our destiny. For this reason, to veer the mind from negative emotions and make it dwell upon the positive sentiments is considered austerity of the mind.

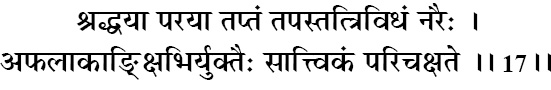

śhraddhayā parayā taptaṁ tapas tat tri-vidhaṁ naraiḥ

aphalākāṅkṣhibhir yuktaiḥ sāttvikaṁ parichakṣhate

śhraddhayā—with faith; parayā—transcendental; taptam—practiced; tapaḥ—austerity; tat—that; tri-vidham—three-fold; naraiḥ—by persons; aphala-ākāṅkṣhibhiḥ—without yearning for material rewards; yuktaiḥ—steadfast; sāttvikam—in the mode of goodness; parichakṣhate—are designated.

When devout persons with ardent faith practice these three-fold austerities without yearning for material rewards, they are designated as austerities in the mode of goodness.

Having delineated the austerities of the body, speech, and mind, Shree Krishna now mentions their characteristics when they are performed in the mode of goodness. He says that an austerity loses its sanctity when material benefits are sought from its performance. It must be performed in a selfless manner, without attachment to rewards. Also, our faith in the value of the austerity should remain steadfast in both success and failure, and its practice should not be suspended because of laziness or inconvenience.

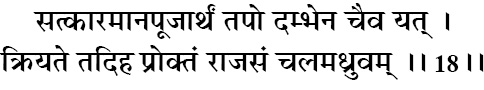

satkāra-māna-pūjārthaṁ tapo dambhena chaiva yat

kriyate tad iha proktaṁ rājasaṁ chalam adhruvam

sat-kāra—respect; māna—honor; pūjā—adoration; artham—for the sake of; tapaḥ—austerity; dambhena—with ostentation; cha—also; eva—certainly; yat—which; kriyate—is performed; tat—that; iha—in this world; proktam—is said; rājasam—in the mode of passion; chalam—flickering; adhruvam—temporary.

Austerity that is performed with ostentation for the sake of gaining honor, respect, and adoration is in the mode of passion. Its benefits are unstable and transitory.

Although austerity is a powerful tool for the purification of the self, not everyone utilizes it with pure intention. A politician labors rigorously to give many lectures a day, which is also a form of austerity, but the purpose is to gain a post and prestige. Similarly, if one engages in spiritual activities to achieve honor and adulation, then the motive is equally material though the means is different. An austerity is classified in the mode of passion if it is performed for the sake of gaining respect, power, or other material rewards.

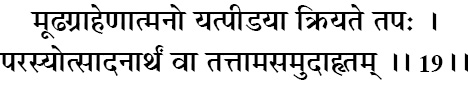

mūḍha-grāheṇātmano yat pīḍayā kriyate tapaḥ

parasyotsādanārthaṁ vā tat tāmasam udāhṛitam

mūḍha—those with confused notions; grāheṇa—with endeavor; ātmanaḥ—one's own self; yat—which; pīḍayā—torturing; kriyate—is performed; tapaḥ—austerity; parasya—of others; utsādana-artham—for harming; vā—or; tat—that; tāmasam—in the mode of ignorance; udāhṛitam—is described to be.

Austerity that is performed by those with confused notions, and which involves torturing the self or harming others, is described to be in the mode of ignorance.

Mūḍha grāheṇāt refers to people with confused notions or ideas, who in the name of austerity, heedlessly torture themselves or even injure others without any respect for the teachings of the scriptures or the limits of the body. Such austerities accomplish nothing positive. They are performed in bodily consciousness and only serve to propagate the grossness of the personality.

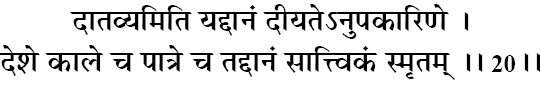

dātavyam iti yad dānaṁ dīyate 'nupakāriṇe

deśhe kāle cha pātre cha tad dānaṁ sāttvikaṁ smṛitam

dātavyam—worthy of charity; iti—thus; yat—which; dānam—charity; dīyate—is given; anupakāriṇe—to one who cannot give in return; deśhe—in the proper place; kāle—at the proper time; cha—and; pātre—to a worthy person; cha—and; tat—that; dānam—charity; sāttvikam—in the mode of goodness; smṛitam—is stated to be.

Charity given to a worthy person simply because it is right to give, without consideration of anything in return, at the proper time and in the proper place, is stated to be in the mode of goodness.

The three-fold divisions of dānam, or charity, are now being described. It is an act of duty to give according to one’s capacity. The Bhaviṣhya Purāṇ states: dānamekaṁ kalau yuge [v5] “In the age of Kali, giving in charity is the means for purification.” The Ramayan states this too:

pragaṭa chāri pada dharma ke kali mahuṅ ek pradhāna

jena kena bidhi dīnheṅ dāna karai kalyāna [v6]

“Dharma has four basic tenets, one amongst which is the most important in the age of Kali—give in charity by whatever means possible.” The act of charity bestows many benefits. It reduces the attachment of the giver toward material objects; it develops the attitude of service; it expands the heart, and fosters the sentiment of compassion for others. Hence, most religious traditions follow the injunction of giving away one-tenth of one’s earnings in charity. The Skandh Purāṇ states:

nyāyopārjita vittasya daśhamānśhena dhīmataḥ

kartavyo viniyogaśhcha īśhvaraprityarthameva cha [v7]

“From the wealth you have earned by rightful means, take out one-tenth, and as a matter of duty, give it away in charity. Dedicate your charity for the pleasure of God.” Charity is classified as proper or improper, superior or inferior, according to the factors mentioned by Shree Krishna in this verse. When it is offered freely from the heart to worthy recipients, at the proper time, and at the appropriate place, it is bequeathed to be in the mode of goodness.

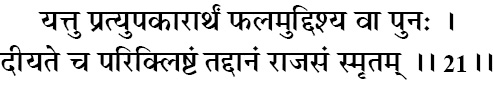

yat tu pratyupakārārthaṁ phalam uddiśhya vā punaḥ

dīyate cha parikliṣhṭaṁ tad dānaṁ rājasaṁ smṛitam

yat—which; tu—but; prati-upakāra-artham—with the hope of a return; phalam—reward; uddiśhya—expectation; vā—or; punaḥ—again; dīyate—is given; cha—and; parikliṣhṭam—reluctantly; tat—that; dānam—charity; rājasam—in the mode of passion; smṛitam—is said to be.

But charity given with reluctance, with the hope of a return or in expectation of a reward, is said to be in the mode of passion.

The best attitude of charity is to give without even being asked to do so. The second-best attitude is to give happily upon being requested for it. The third-best sentiment of charity is to give begrudgingly, having being asked for a donation, or to regret later, “Why did I give so much? I could have gotten away with a smaller amount.” Shree Krishna classifies this kind of charity in the mode of passion.

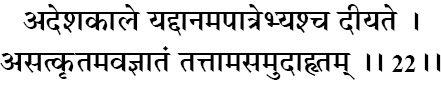

adeśha-kāle yad dānam apātrebhyaśh cha dīyate

asat-kṛitam avajñātaṁ tat tāmasam udāhṛitam

adeśha—at the wrong place; kāle—at the wrong time; yat—which; dānam—charity; upātrebhyaḥ—to unworthy persons; cha—and; dīyate—is given; asat-kṛitam—without respect; avajñātam—with contempt; tat—that; tāmasam—of the nature of nescience; udāhṛitam—is held to be.

And that charity, which is given at the wrong place and wrong time to unworthy persons, without showing respect, or with contempt, is held to be of the nature of nescience.

Charity in the mode of ignorance is done without consideration of proper place, person, attitude, or time. No beneficial purpose is served by it. For example, if money is offered to an alcoholic, who uses it to get inebriated, and then ends up committing a murder, the murderer will definitely be punished according to the law of karma, but the person who gave the charity will also be culpable for the offence. This is an example of charity in the mode of ignorance that is given to an undeserving person.

om tat sad iti nirdeśho brahmaṇas tri-vidhaḥ smṛitaḥ

brāhmaṇās tena vedāśh cha yajñāśh cha vihitāḥ purā

om tat sat—syllables representing aspects of transcendence; iti—thus; nirdeśhaḥ—symbolic representatives; brahmaṇaḥ—the Supreme Absolute Truth; tri-vidhaḥ—of three kinds; smṛitaḥ—have been declared; brāhmaṇāḥ—the priests; tena—from them; vedāḥ—scriptures; cha—and; yajñāḥ—sacrifice; cha—and; vihitāḥ—came about; purā—from the beginning of creation.

The words “Om Tat Sat” have been declared as symbolic representations of the Supreme Absolute Truth, from the beginning of creation. From them came the priests, scriptures, and sacrifice.

In this chapter, Shree Krishna explained the categories of yajña (sacrifice), tapaḥ (austerity), and dān (charity), according to the three modes of material nature. Amongst these three modes, the mode of ignorance degrades the soul into nescience, languor, and sloth. The mode of passion excites the living being and binds it in innumerable desires. The mode of goodness is serene and illuminating, and engenders the development of virtues. Yet, the mode of goodness is also within the realm of Maya. We must not get attached to it; instead, we must use the mode of goodness as a stepping-stone to reach the transcendental platform. In this verse, Shree Krishna goes beyond the three guṇas, and discusses the words Om Tat Sat, which symbolize different aspects of the Absolute Truth. In the following verses, he explains the significance of these three words.

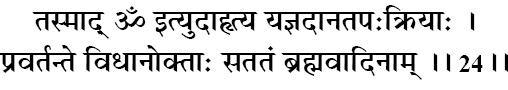

tasmād om ity udāhṛitya yajña-dāna-tapaḥ-kriyāḥ

pravartante vidhānoktāḥ satataṁ brahma-vādinām

tasmāt—therefore; om—sacred syllable om; iti—thus; udāhṛitya—by uttering; yajña—sacrifice; dāna—charity; tapaḥ—penance; kriyāḥ—performing; pravartante—begin; vidhāna-uktāḥ—according to the prescriptions of Vedic injunctions; satatam—always; brahma-vādinām—expounders of the Vedas.

Therefore, when performing acts of sacrifice, offering charity, or undertaking penance, expounders of the Vedas always begin by uttering “Om” according to the prescriptions of Vedic injunctions.

The syllable Om is a symbolic representation of the impersonal aspect of God. It is also considered as the name for the formless Brahman. It is also the primordial sound that pervades creation. Its proper pronunciation is: “Aaa” with the mouth open, “Ooh” with the lips puckered, and “Mmm” with the lips pursed. It is placed in the beginning of many Vedic mantras as a bīja (seed) mantra to invoke auspiciousness.

tad ity anabhisandhāya phalaṁ yajña-tapaḥ-kriyāḥ

dāna-kriyāśh cha vividhāḥ kriyante mokṣha-kāṅkṣhibhiḥ

tat—the syllable Tat; iti—thus; anabhisandhāya—without desiring; phalam—fruitive rewards; yajña—sacrifice; tapaḥ—austerity; kriyāḥ—acts; dāna—charity; kriyāḥ—acts; cha—and; vividhāḥ—various; kriyante—are done; mokṣha-kāṅkṣhibhiḥ—by seekers of freedom from material entanglements.

Persons who do not desire fruitive rewards, but seek to be free from material entanglements, utter the word “Tat” along with acts of austerity, sacrifice, and charity.

The fruits of all actions belong to God, and hence, any yajña (sacrifice), tapaḥ (austerity), and dānam (charity), must be consecrated by offering it for the pleasure of the Supreme Lord. Now, Shree Krishna glorifies the sound vibration “Tat,” which refers to Brahman. Chanting Tat along with austerity, sacrifice, and charity symbolizes that they are not to be performed for material rewards, but for the eternal welfare of the soul through God-realization.

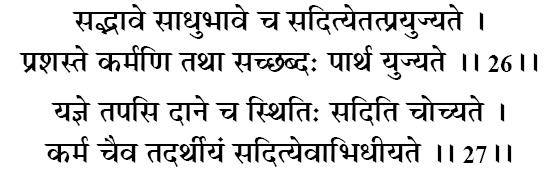

sad-bhāve sādhu-bhāve cha sad ity etat prayujyate

praśhaste karmaṇi tathā sach-chhabdaḥ pārtha yujyate

yajñe tapasi dāne cha sthitiḥ sad iti chochyate

karma chaiva tad-arthīyaṁ sad ity evābhidhīyate

sat-bhāve—with the intention of eternal existence and goodness; sādhu-bhāve—with auspicious inention; cha—also; sat—the syllable Sat; iti—thus; etat—this; prayujyate—is used; praśhaste—auspicious; karmaṇi—action; tathā—also; sat-śhabdaḥ—the word "Sat"; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; yujyate—is used; yajñe—in sacrifice; tapasi—in penance; dāne—in charity; cha—and; sthitiḥ—established in steadiness; sat—the syllable Sat; iti—thus; cha—and; uchyate—is pronounced; karma—action; cha—and; eva—indeed; tat-arthīyam—for such purposes; sat—the syllable Sat; iti—thus; eva—indeed; abhidhīyate—is described.

The word “Sat” means eternal existence and goodness. O Arjun, it is also used to describe an auspicious action. Being established in the performance of sacrifice, penance, and charity, is also described by the word “Sat.” And so any act for such purposes is named “Sat.”

Now the auspiciousness of the word “Sat” is being glorified by Shree Krishna. This word Sat has many connotations, and the above two verses describe some of these. Sat is used to mean perpetual goodness and virtue. In addition, auspicious performance of sacrifice, austerity, and charity is also described as Sat. Sat also means that which always exists i.e., it is an eternal truth. The Śhrīmad Bhāgavatam states:

satya-vrataṁ satya-paraṁ tri-satyaṁ

satyasya yoniṁ nihitaṁ cha satye

satyasya satyam ṛita-satya-netraṁ

satyātmakaṁ tvāṁ śharaṇaṁ prapannāḥ (10.2.26) [v8]

“O Lord, your vow is true, for not only are you the Supreme Truth, but you are also the truth in the three phases of the cosmic manifestation—creation, maintenance, and dissolution. You are the origin of all that is true, and you are also its end. You are the essence of all truth, and you are also the eyes by which the truth is seen. Therefore, we surrender unto you, the Sat i.e., Supreme Absolute Truth. Kindly give us protection.”

aśhraddhayā hutaṁ dattaṁ tapas taptaṁ kṛitaṁ cha yat

asad ity uchyate pārtha na cha tat pretya no iha

aśhraddhayā—without faith; hutam—sacrifice; dattam—charity; tapaḥ—penance; taptam—practiced; kṛitam—done; cha—and; yat—which; asat—perishable; iti—thus; uchyate—are termed as; pārtha—Arjun, the son of Pritha; na—not; cha—and; tat—that; pretya—in the next world; na u—not; iha—in this world.

O son of Pritha, whatever acts of sacrifice or penance are done without faith, are termed as “Asat.” They are useless both in this world and the next.

In order to firmly establish that all Vedic activities should be performed with faith, Shree Krishna now emphasizes the futility of Vedic activities done without it. He says that those who act without faith in the scriptures do not get good fruits in this life because their actions are not perfectly executed. And since they do not fulfill the conditions of the Vedic scriptures, they do not receive good fruits in the next life either. Thus, one’s faith should not be based upon one’s own impressions of the mind and intellect. Instead, it should be based upon the infallible authority of the Vedic scriptures and the Guru. This is the essence of the seventeenth chapter.